1. Introduction

Carboxylesterases (CEs, with EC 3.1.1.1), as an essential member of serine hydrolases superfamily, are found in various tissues of human body, especially the liver and intestine [

1]. CEs play the key roles in catalyzing the hydrolysis of endogenous esters, thioesters, carbonates, carbamates and amides. In addition, they are involved in metabolic elimination of various xenobiotics, including ester-prodrugs, pesticides, and environmental toxicants [

2]. Apart from metabolizing various exogenous and endogenous substances, CEs also have played the vital physiological functions in lipid homeostasis that converts monoacylglycerides to free fatty acids [

3]. However, the abnormal CEs expression is tightly correlated with many diseases, such as hyperlipidemia, diabetes, atherosclerosis, and even liver cancer [

4,

5]. Therefore, exploring an effective strategy to track the distribution of CEs and evaluate its activity variation in cells or tissues is of great significance for both clinical diagnosis and treatment of various diseases.

Till now, there have been already various methods for the detection of CEs, including mass spectrometry [

6], chromatography [

7], chemiluminescence [

8], and fluorescent probe [

9]. Among them, fluorescent probe attracted the great attentions owing to its advantages of simple operation, fast detection, high spatiotemporal resolution, and noninvasive imaging in living systems [

9]. At present, a plenty of fluorescent probes have been reported based on various mechanisms, including photoinduced electron transfer (PET) [

10,

11,

12], intramolecular charge transfer (ICT) [

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18], and other mechanisms [

19,

20,

21,

22]. However, these probes still suffered from various drawbacks in practical applications. At first, most of them required a long time (≥ 10 min) to accomplish the fluorescence response [

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22], thus they were unsuitable for the real-time monitoring of CEs in living organisms. In addition, some probes were severely hydrophobic, and they required to use a large volume fraction of toxic organic cosolvents [

11,

13,

15,

17], which was harmful for their applications in analysis of real biological sample. Even worse, many probes outputted the fluorescence signals in visible region (< 650 nm) [

10,

11,

12,

17,

20,

21,

22], which might result in the low tissue penetration ability and serious tissue damage. By contrast, the near-infrared (NIR) fluorescent probe (650–900 nm) were more suitable for the biological testing in

vivo, because they exhibited the low background interference, excellent tissue penetrability, and low tissue damage [

23,

24]. The characteristics of above fluorescent probes has been summarized in

Table S1. Therefore, it is urgently needed to develop a water-soluble NIR fluorescent probe for the rapid, sensitive and selective detection of CEs in biological system.

Aggregation-induced emission (AIE), a unique optical phenomena that a class of luminogens were nearly non-emissive in dilute solution but highly emissive in the aggregated state, which was firstly coined by Tang et al. in 2001 [

25]. In this regard, turn-on bioprobes could be easily constructed by taking advantage of AIE effect. It was believed that the nanoaggregates of the AIE-based probes would possess better photostability and higher signal reliability than the single-molecule of conventional probes. Furthermore, the negligible background noise of AIE-based probes rendered them especially attractive in continuous monitoring of biological processes without the repeated washing steps [

26]. On account of above advantages, AIE-based probes have been widely used in bioimaging and biological testing [

27]. But, as far as we known, the AIE-based fluorescent probes for CEs detection were rarely reported. Dai and co-workers have reported an AIE-based fluorescent probes for monitoring CEs in HepG2 cells, but the fluorescence signal was in visible region (λ

em = 589 nm) [

22], thereby this probe was unsuitable for the fluorescence detection of CEs in

vivo.

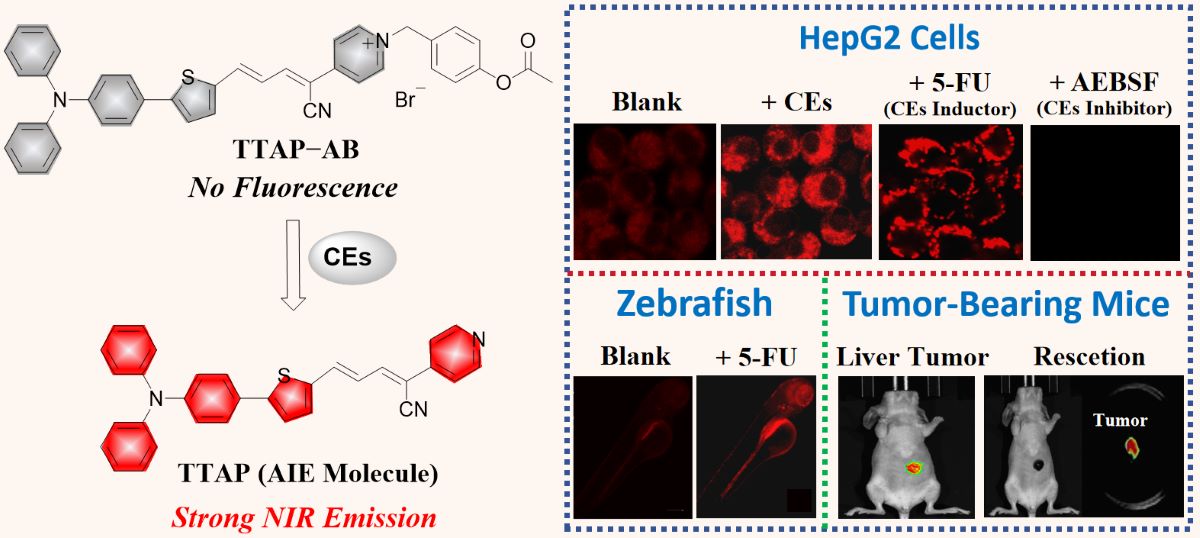

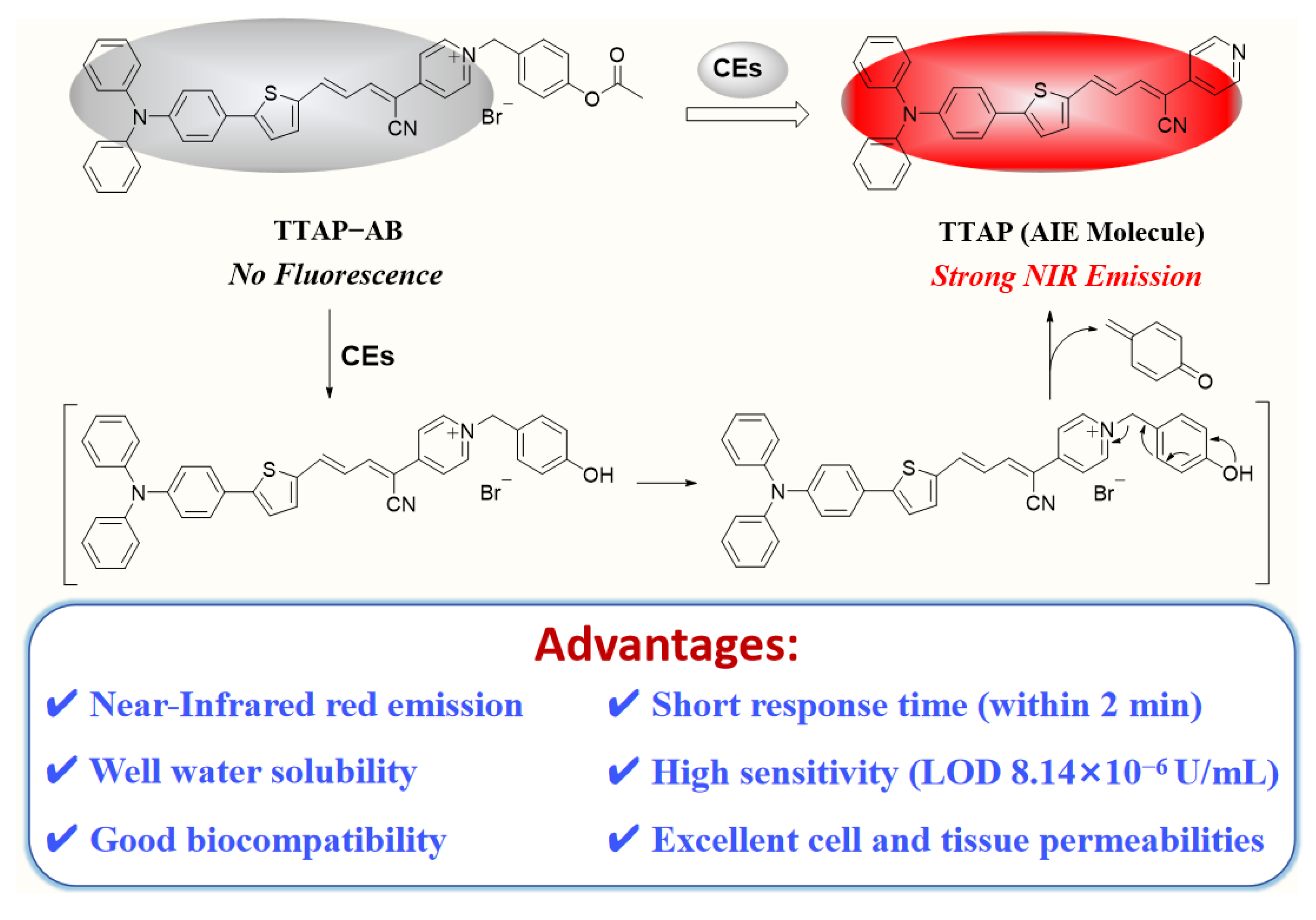

Herein, we have developed a novel NIR fluorescence probe

TTAP−

AB for detecting CEs with the AIE mechanism (

Scheme 1). Probe

TTAP−

AB was designed based a typical D−π−A structure. In which, the conjugated C=C double bond bridged the triphenylamine-thiophene (

TT) skeleton (electron donor, D) and the acrylonitrile-pyridinium (

AP) moiety (electron acceptor, A). Owing to the cationic pyridinium moiety, probe

TTAP−

AB was well dissolved in PBS buffer. As the presence of CEs, the acetoxy-benzyl recognition group was hydrolyzed and broken by CEs, which triggered the self-elimination reaction and finally released the AIE-active fluorophores

TTAP. Because

TTAP was not dissolved in PBS buffer, thus its aggregation aroused an intense NIR emission (λ

em = 692 nm). In addition, probe

TTAP−

AB exhibited the high selectivity, fast response (within 2 min), and low limit of detection (LOD: 8.14×10

−6 U/mL) to CEs. Owing to the good biocompatibility and excellent cell, tissue penetrability,

TTAP−

AB could monitor the dynamic change of CEs levels induced by 5-fluorouracil (anti-tumor drug) and CEs inhibitor in living cells and zebrafish. More importantly,

TTAP−

AB was successfully employed to image the liver tumor and assist tumor resection by the real-time monitoring of CEs, indicating that probe

TTAP−

AB was promising to guide liver cancer surgery.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Materials and Instruments

Unless otherwise stated, all chemicals were purchased from commercial suppliers and used without further purification. Double-distilled water and chromatographic solvents were used for fluorescence tests. A Bruker AV-400 spectrometer was employed to record 1H NMR and 13C NMR spectra. High-resolution mass spectra (HRMS) were obtained with a Thermo Scientific Q Exactive type mass spectrometer. Fluorescence spectra were collected by Hitachi F-4500 fluorescence spectrometer. Dynamic light scattering (DLS) experiments were investigated with ZEN3600 Malvern particle sizer. Fluorescence images of living cells and zebrafish were obtained with a Zeiss LSM 880 confocal laser scanning microscope (Germany). All fluorescence imaging of living mice was performed by a BLT AniView 600 small animal optical imaging system (China).

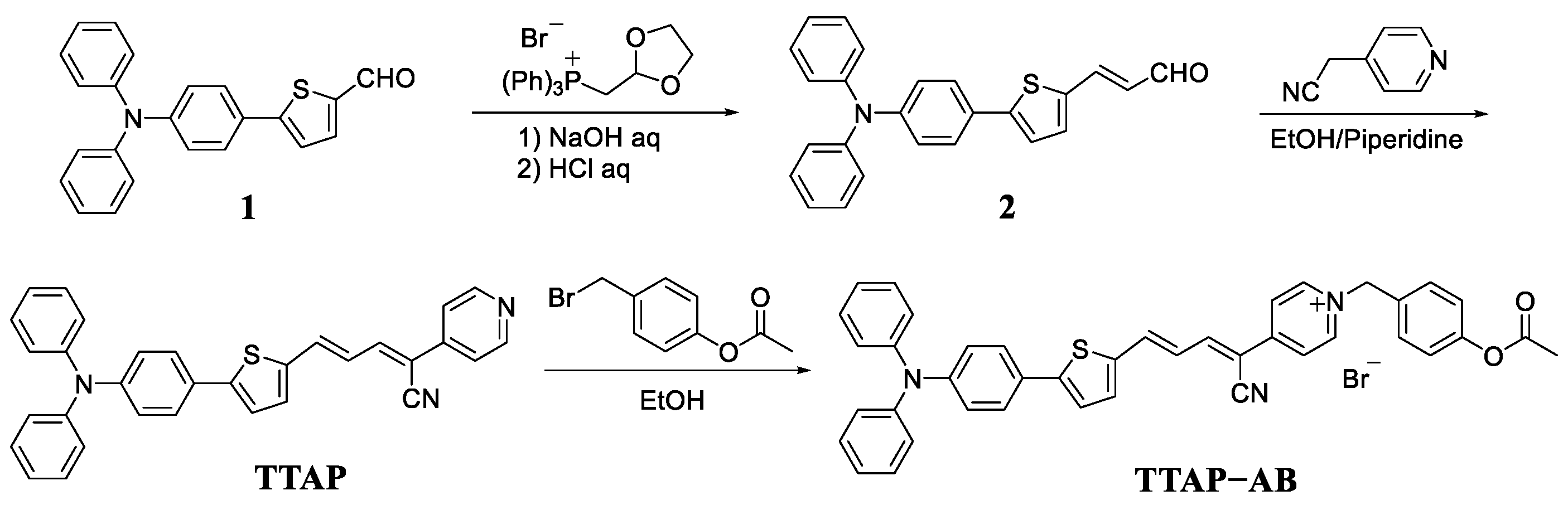

3.2. Synthesis of Fluorophore TTAP

Compound

2 was synthesized according to the previous method [

31], and its synthetic procedure was exhibited in the Supporting Information (Section S4). After that, compound

2 (1.14 g, 3.00 mmol) and 4-pyridineacetonitrile (0.17 g, 3.60 mmol) were dissolved in 15 mL ethanol, and then 0.6 mL piperidine was added into the solution. This mixture was reacted at 80 ℃ for 8 h under N

2 atmosphere. After cooling to room temperature, the mixture was concentrated using rotary evaporators, and the remaining solid was purified by column chromatography (CH

2Cl

2/CH

3OH as eluent, v/v = 30:1). The final product

TTAP was obtained as a dark red solid (0.93 g, 64% yield).

1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-

d6):

δ (ppm) 8.65 (d,

J = 6.0 Hz, 2H, -PyH), 8.21 (d,

J = 7.2 Hz, 1H, thiophene H), 7.65-7.68 (m, 2H, -PyH), 7.61-7.63 (m, 2H, thiophene H and vinyl H), 7.30-7.38 (m, 8H, -ArH and vinyl H ), 7.04-7.15 (m, 8H, -ArH);

13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-

d6):

δ (ppm) 150.48, 150.13, 147.76, 147.00, 146.58, 145.77, 138.65, 137.23, 133.66, 129.74, 129.65, 126.89, 124.75, 123.87, 123.24, 122.18, 119.20, 116.14. HRMS (ESI

+): calcd for C

32H

23N

3S [M+H]

+ 482.16854, found 482.16852.

3.3. Synthesis of Probe TTAP−AB

Compound TTAP (0.72 g, 1.50 mmol) and 4-(bromomethyl)phenyl acetate (0.36 g, 1.60 mmol) were dissolved in 6 mL dry ethanol, and the mixture was then refluxed under N2 atmosphere overnight. After cooling to room temperature, the mixture was concentrated using rotary evaporators, and the obtained residue was then purified using a neutral aluminum oxide column (CH2Cl2/CH3OH as eluent, v/v = 6:1). The final product TTAP−AB was obtained as a purple black solid (0.66 g, 62% yield). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ (ppm) 9.14 (d, J = 7.2 Hz, 2H, -PyH), 8.62 (d, J = 11.6 Hz, 1H, vinyl H), 8.26 (d, J = 6.8 Hz, 1H, thiophene H), 7.57-7.80 (m, 7H, -PyH, thiophene H and -ArH), 7.35-7.40 (m, 4H, -ArH), 6.94-7.23 (m, 12H, vinyl H and -ArH), 5.79 (s, 2H, -CH2), 2.27 (s, 3H, -CH3); 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ (ppm) 169.32, 159.96, 154.66, 150.81, 150.09, 149.07, 146.22, 144.61, 142.34, 135.63, 135.43, 134.69, 132.40, 131.55, 130.20, 129.87, 128.83, 127.70, 125.28, 124.93, 124.45, 122.79, 121.33, 116.64, 98.90, 61.67, 22.11. HRMS (ESI+): calcd for C32H23N3S [M-Br]+ 630.22097, found 630.22103.

3.4. Optical Study

Stock solutions of probe TTAP−AB (5 μM) were prepared in PBS buffer (10 mM, pH 7.4). Stock solutions of the cations (K+, Na+, Zn2+, Cu2+, Mg2+), anions (Cl−, CO32−, SO32−, S2−, H2PO4−), and amino acids (glutamic acid (Glu), cysteine (Cys), glutathione (GSH), Homocysteine (Hcy)) were prepared in deionized water (5 mM). Stock solutions of different enzymes (carboxylesterases, acetyl cholinesterase (AchE), carbonic anhydrase I (CAI), xanthine oxidase (XO), peroxidase (POD), carboxypeptidase A (CPA), leucine aminopeptidase (LAP)) were prepared in sterilized water (8 U/mL). The fluorescence spectra of probe TTAP−AB (5 μM) with different concentrations of CEs or other interferents in PBS buffer (10 mM, pH 7.4) were recorded at 37 ℃.

3.5. Living Cell Imaging

All HepG2 cells were purchased from Wuhan Mingde Biotechnology Co., LTD. For cytotoxicity assay, the cells were firstly incubated in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum, and then the cells were kept at 37 °C under the condition of 5% CO2 for 24 h. After that, the cells were incubated with various concentrations of probe TTAP−AB (5, 10, 15, 20, 25 μM) for 10 h. After washing with PBS, 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) was added and the medium was incubated at 37 °C for 4h. Finally, the absorbance was read at 490 nm using an ELISA reader (Varioskan Flash). The percentage of cell viability was calculated relative to control wells designated as 100% viable cells.

For exogenous CEs imaging, HepG2 cells were firstly stained with TTAP−AB (5 μM) for 30 min, and then incubated with different concentration of CEs (0.10 U/mL, 0.15 U/mL, 0.20 U/mL) at 37 °C for 1 h, respectively. After PBS washing, the image was taken by a confocal fluorescence microscopy (λex = 560 nm; λem = 650–750 nm). For endogenous CEs imaging, HepG2 cells were divided into four groups. As a control group, HepG2 cells were only cultivated with PBS buffer for 30 min. In the second group, the cells were incubated with probe TTAP−AB (5 μM) for 1 h. In the third group, HepG2 cells were pre-treated with the drug 5-fluorouracil (5-FU, 100 μM) for 6 h, and then incubated with TTAP−AB (5 μM) for 1 h. In the final group, HepG2 cells were pre-treated with (4-(2-Aminoethyl)benzenesulfonyl fluoride hydrochloride (AEBSF, a CEs inhibitor, 1 mM) for 2 h, and then incubated with TTAP−AB (5 μM) for another 1 h. Prior to imaging, the above cells were washed with PBS buffer (10 mM, pH = 7.4) for 3 times. And then, fluorescence imaging was taken by a confocal fluorescence microscopy (λex = 560 nm; λem = 650–750 nm).

3.6. Zebrafish Imaging

Zebrafish embryos were purchased from Shanghai FishBio Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). Larval zebrafish (4 days old) were used for imaging, and they were divided into four groups. In a control group, zebrafish were only cultured with probe TTAP−AB (5 μM) at 37 ℃ for 1 h. In the second group, zebrafish were grown with drug 5-FU (50 μM) for 10 h, and then stained with TTAP−AB (5 μM) at 37 ℃ for another 1 h. In the third group, zebrafish were stained with drug 5-FU (100 μM) for 10 h, and then incubated with TTAP−AB (5 μM) at 37 ℃ for another 1 h. In the last group, zebrafish were firstly treated with 5-FU (100 μM) for 10 h, and then cultivated with AEBSF (1 mM) for 4 h, finally stained with TTAP−AB (5 μM) at 37 °C for another 1 h. All zebrafish were washed three times with embryo media, and then transferred to a confocal fluorescence microscopy for imaging (λex = 560 nm; λem = 650–750 nm).

3.7. Fluorescence Imaging in Mice

All animal experiments were approved by the Experimental Animal Ethics Committee of Wuchang University of Technology, which were conducted according to the guidelines for animal experiments. All BALB/c mice (18-20 g) were purchased from Shanghai Slac Laboratory Animal Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China), and operated in accordance with Wuchang University of Technology guidelines.

For histology and immunohistochemical staining, all tissues of BALB/c mice were immediately fixed in 10% formaldehyde after sacrifice. Histological examination was carried out according to a conventional methods [

12,

13,

19], and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E). The morphology of any observed lesions was classified and recorded according to the classification criteria.

For imaging CEs in vivo, The mice were divided into two groups. As a control group, mice were intravenously injected with PBS (100 μL). In the experimental group, mice were intravenously with probe TTAP−AB (100 μL, 200 μM) for real-time recording. All the mice were anaesthetized and performed in vivo imaging. After that, they were used for the biodistribution studies. These mice were killed by euthanasia, and their organs (heart, liver, spleen, lung, kidney) were dissected for fluorescence measurements. The fluorescence images were obtained by a BLT AniView 600 small animal optical imaging system (China) (λex = 600 nm, λem = 650-750 nm).

For visualizing CEs in tumor-bearing mice, the HepG2 cells (5 × 107 cells) were subcutaneously injected into female BALB/c mice (18-20 g) to establish a mouse tumor model. After 20 days, probe TTAP−AB (20 μL, 100 μM) was injected into tumor-bearing mice. All the mice were anaesthetized in vivo imaging, and the liver tumor was dissected from mice after the euthanasia. The fluorescence images were obtained by a BLT AniView 600 small animal optical imaging system (China) (λex = 600 nm, λem = 650-750 nm).

4. Conclusions

In summary, a new NIR fluorescent probe TTAP−AB has been reasonably constructed for visualizing CEs in living systems. Under physiological conditions, probe TTAP−AB could selectively, sensitively, and fast detect CEs through AIE mechanism. The sensing mechanism was confirmed by HRMS, 1H NMR and fluorescence spectra. In addition, probe TTAP−AB exhibited the good biocompatibility as well as the excellent cell, tissue permeability, and it was favorably employed to monitor the dynamic change of CEs levels under drug-induced modulation in living cells and zebrafish. More importantly, probe TTAP−AB was able to image the liver tumor and assisted tumor resection by the real-time detection of CEs, indicating that TTAP−AB has a great potential for practical clinical applications. Taken together, probe TTAP−AB can not only enrich the strategies for CEs detection in biological systems, but also exhibit great potential for some clinical imaging applications, including medical diagnosis, preclinical research, and imaging-guided surgery.

Scheme 1.

The proposed mechanism of probe TTAP−AB toward CEs.

Scheme 1.

The proposed mechanism of probe TTAP−AB toward CEs.

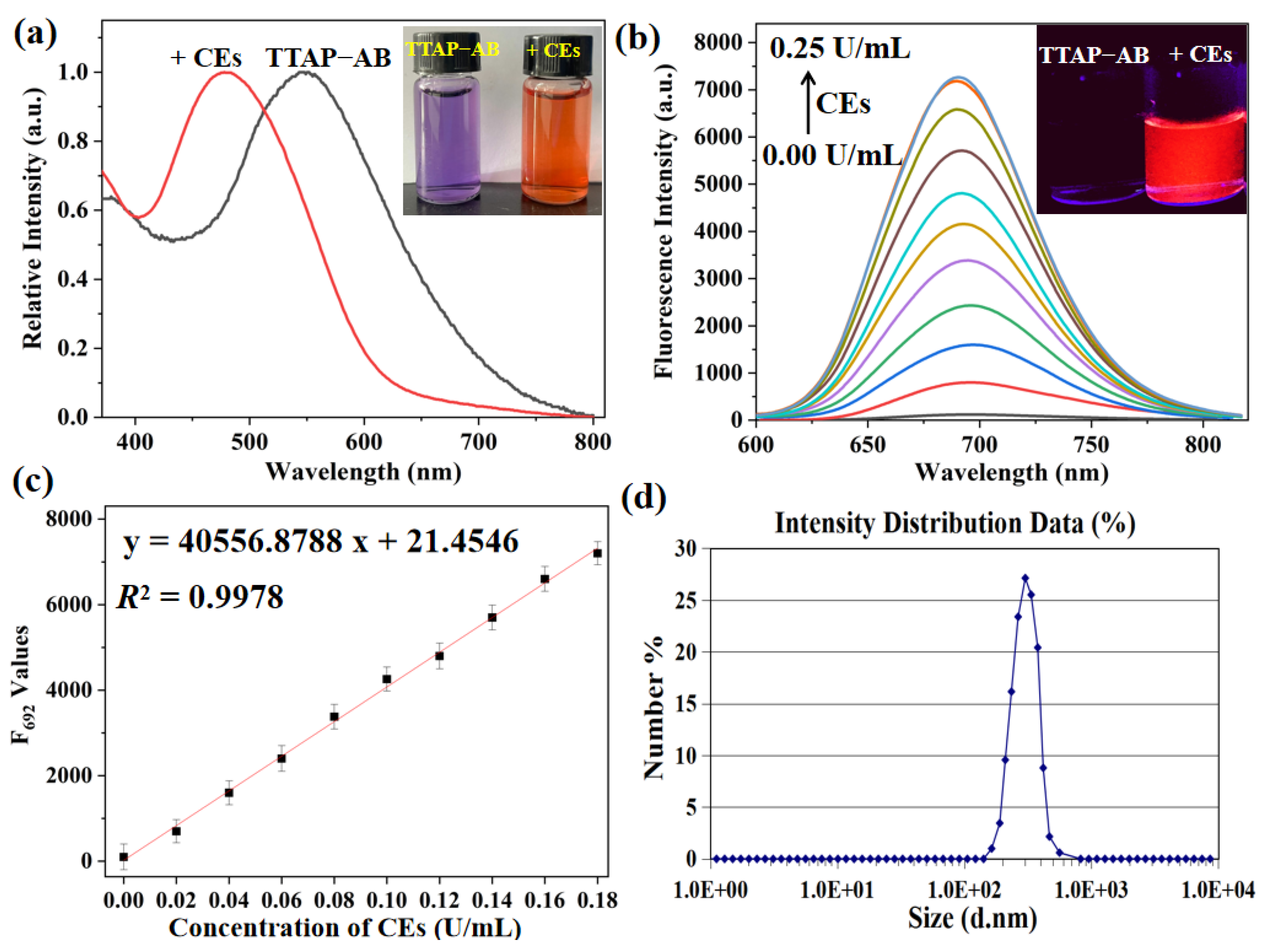

Figure 1.

(a) Normalized absorption of probe TTAP−AB (5 μM) toward 0.25 U/mL CEs. Inset: the corresponding photographs taken under sun light. (b) Fluorescence spectra of probe TTAP−AB (5 μM) toward CEs (0.00–0.25 U/mL). λex = 505 nm; Slit width: 5 nm. Inset: the corresponding photographs taken under 365 nm light. (c) The fitted linear relationship of fluorescence intensity at 692 nm versus CEs concentrations. (d) DLS profiles of TTAP−AB (5 μM) with 0.25 U/mL of CEs in PBS buffer. Error bars are ± SD (n = 3).

Figure 1.

(a) Normalized absorption of probe TTAP−AB (5 μM) toward 0.25 U/mL CEs. Inset: the corresponding photographs taken under sun light. (b) Fluorescence spectra of probe TTAP−AB (5 μM) toward CEs (0.00–0.25 U/mL). λex = 505 nm; Slit width: 5 nm. Inset: the corresponding photographs taken under 365 nm light. (c) The fitted linear relationship of fluorescence intensity at 692 nm versus CEs concentrations. (d) DLS profiles of TTAP−AB (5 μM) with 0.25 U/mL of CEs in PBS buffer. Error bars are ± SD (n = 3).

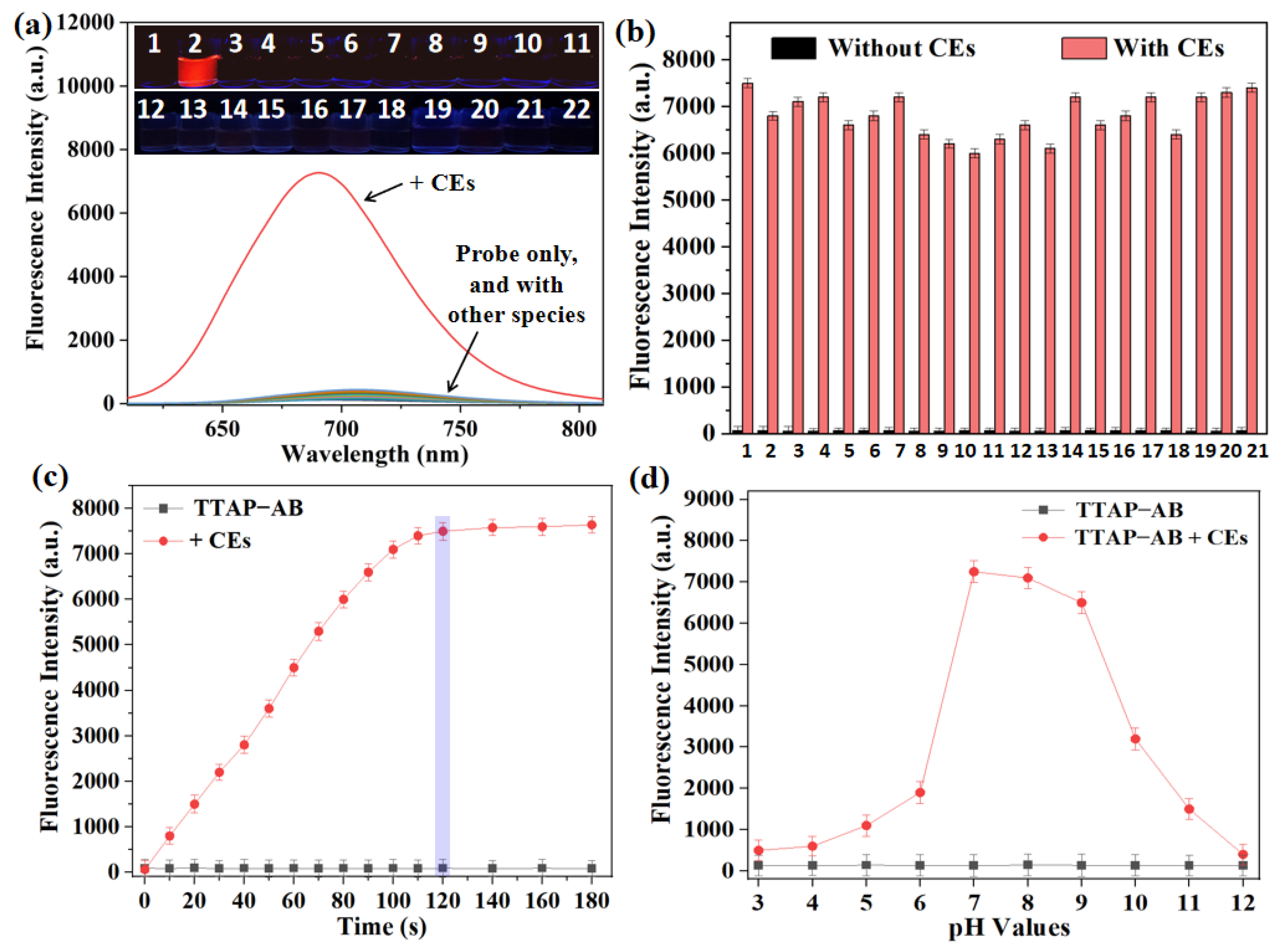

Figure 2.

(a) Fluorescence spectra of probe TTAP−AB (5 μM) in response to various species (0.20 U/mL CEs, 0.60 U/mL other enzymes, 100 μM different amino acids and ions) in PBS buffer (10 mM, pH 7.4). 1: Blank; 2: CEs; 3: AchE; 4: CAI; 5: XO; 6: POD; 7: CPA; 8: LAP; 9: Glu; 10: Cys; 11: GSH; 12: Hcy; 13: K+; 14: Na+; 15: Zn2+; 16: Cu2+; 17: Mg2+; 18: Cl−; 19: CO32−; 20: SO32−; 21: S2−; 22: H2PO4−. Insert: The corresponding photos taken under 365 nm light. (b) The fluorescence intensity of TTAP−AB (5 μM) in the presence of various analytes (100 μM or 0.60 U/mL) without and with CEs (0.20 U/mL). 1: Blank; 2: AchE; 3: CAI; 4: XO; 5: POD; 6: CPA; 7: LAP; 8: Glu; 9: Cys; 10: GSH; 11: Hcy; 12: K+; 13: Na+; 14: Zn2+; 15: Cu2+; 16: Mg2+; 17: Cl−; 18: CO32−; 19: SO32−; 20: S2−; 21: H2PO4−. (c) The time-dependent experiments of probe TTAP−AB (5 µM) without and with CEs (0.20 U/mL). (d) Fluorescence intensity changes of TTAP−AB (5 µM) in the presence of CEs (0.20) under different pH conditions. The fluorescence intensity was recorded at 692 nm. λex = 505 nm, error bars are ± SD (n = 3).

Figure 2.

(a) Fluorescence spectra of probe TTAP−AB (5 μM) in response to various species (0.20 U/mL CEs, 0.60 U/mL other enzymes, 100 μM different amino acids and ions) in PBS buffer (10 mM, pH 7.4). 1: Blank; 2: CEs; 3: AchE; 4: CAI; 5: XO; 6: POD; 7: CPA; 8: LAP; 9: Glu; 10: Cys; 11: GSH; 12: Hcy; 13: K+; 14: Na+; 15: Zn2+; 16: Cu2+; 17: Mg2+; 18: Cl−; 19: CO32−; 20: SO32−; 21: S2−; 22: H2PO4−. Insert: The corresponding photos taken under 365 nm light. (b) The fluorescence intensity of TTAP−AB (5 μM) in the presence of various analytes (100 μM or 0.60 U/mL) without and with CEs (0.20 U/mL). 1: Blank; 2: AchE; 3: CAI; 4: XO; 5: POD; 6: CPA; 7: LAP; 8: Glu; 9: Cys; 10: GSH; 11: Hcy; 12: K+; 13: Na+; 14: Zn2+; 15: Cu2+; 16: Mg2+; 17: Cl−; 18: CO32−; 19: SO32−; 20: S2−; 21: H2PO4−. (c) The time-dependent experiments of probe TTAP−AB (5 µM) without and with CEs (0.20 U/mL). (d) Fluorescence intensity changes of TTAP−AB (5 µM) in the presence of CEs (0.20) under different pH conditions. The fluorescence intensity was recorded at 692 nm. λex = 505 nm, error bars are ± SD (n = 3).

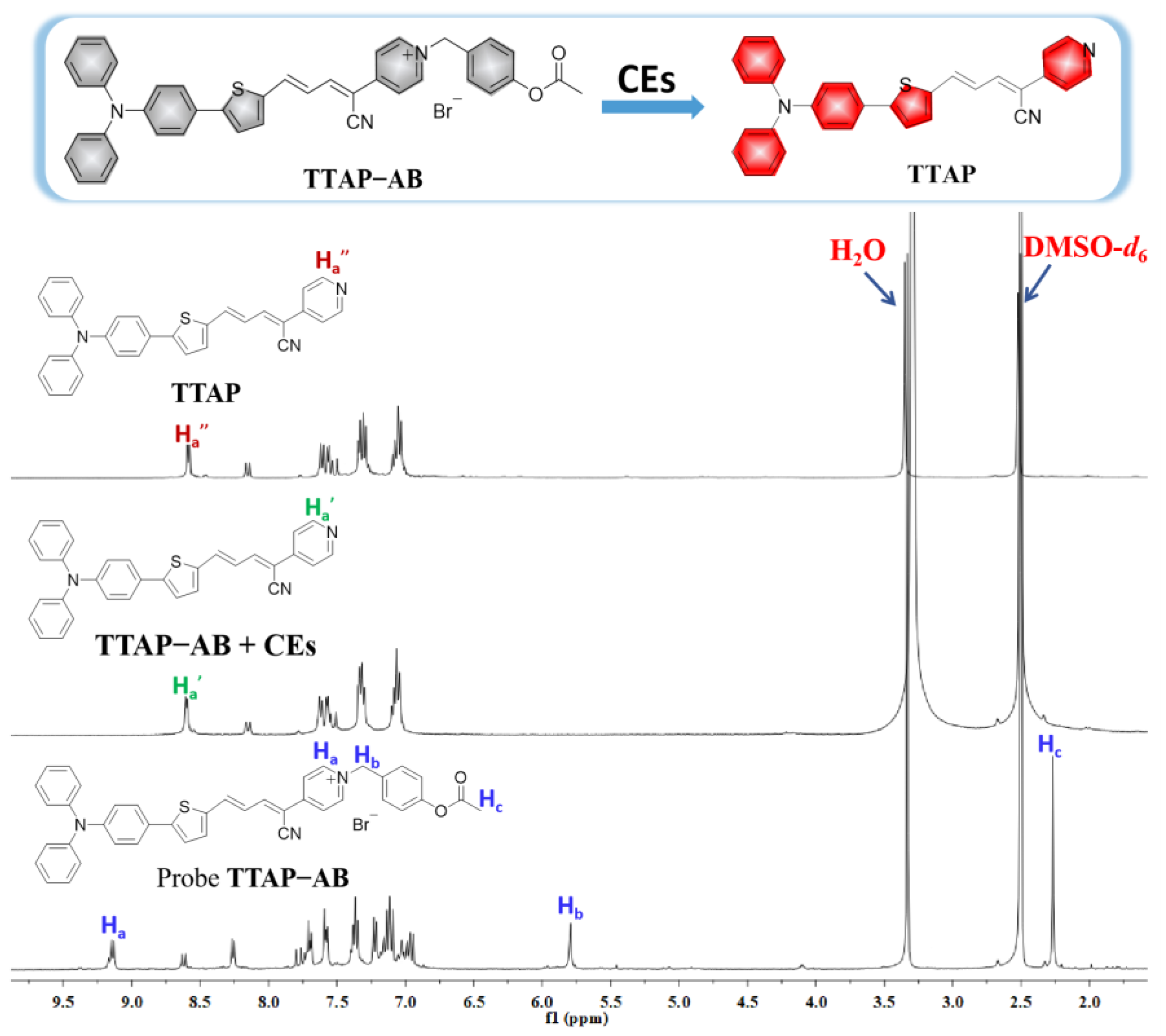

Figure 3.

1H NMR spectra of compound TTAP, probe TTAP−AB, and the isolated product of TTAP−AB with CEs conducted in DMSO-d6.

Figure 3.

1H NMR spectra of compound TTAP, probe TTAP−AB, and the isolated product of TTAP−AB with CEs conducted in DMSO-d6.

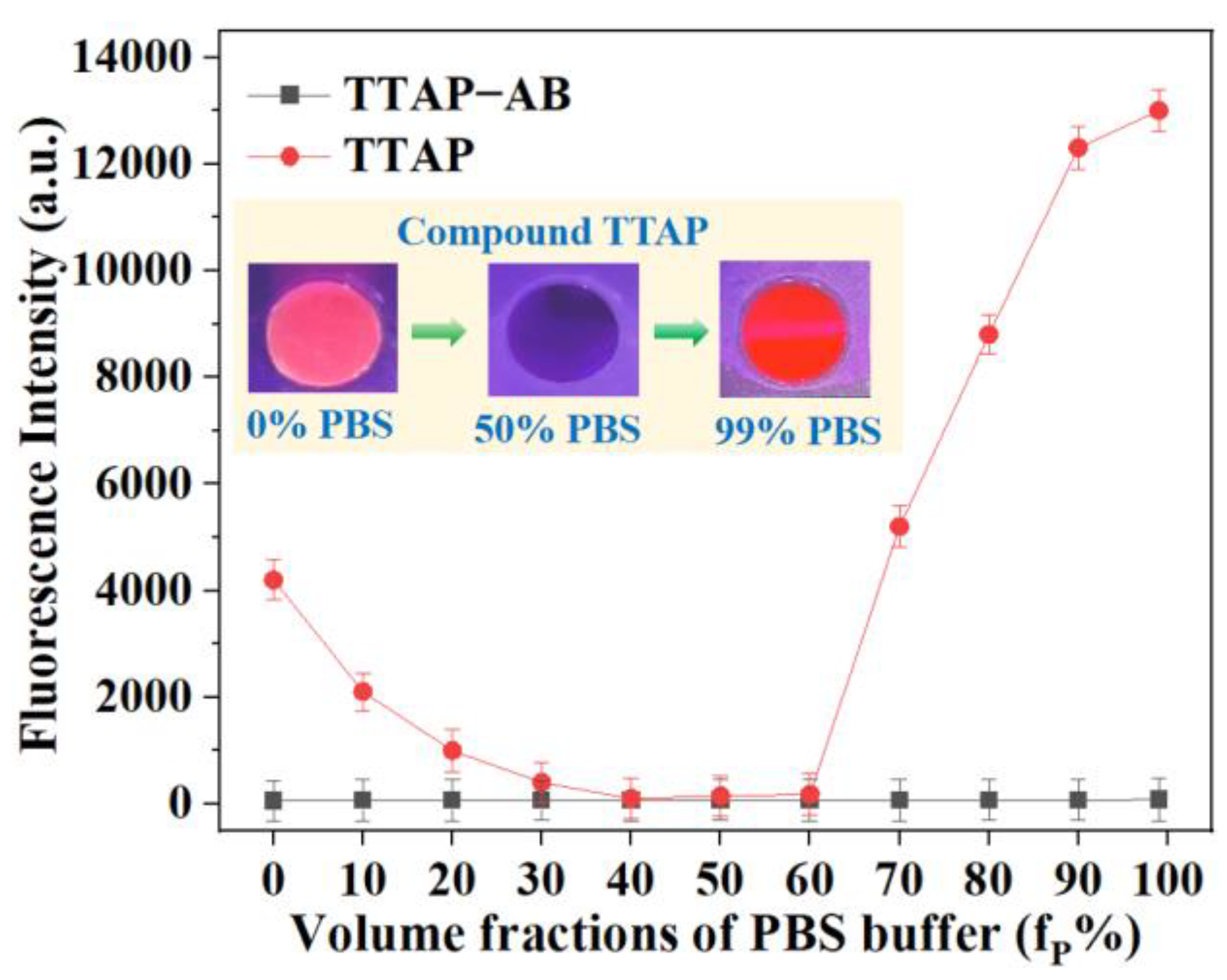

Figure 4.

The fluorescence intensity of probe TTAP−AB (15 μM) and compound TTAP (15 μM) in DMSO–PBS buffer mixture with different volume fractions of PBS buffer (fP %). Insert: the photos of TTAP in different solutions taken under 365 nm light irradiation. Error bars are ± SD (n = 3).

Figure 4.

The fluorescence intensity of probe TTAP−AB (15 μM) and compound TTAP (15 μM) in DMSO–PBS buffer mixture with different volume fractions of PBS buffer (fP %). Insert: the photos of TTAP in different solutions taken under 365 nm light irradiation. Error bars are ± SD (n = 3).

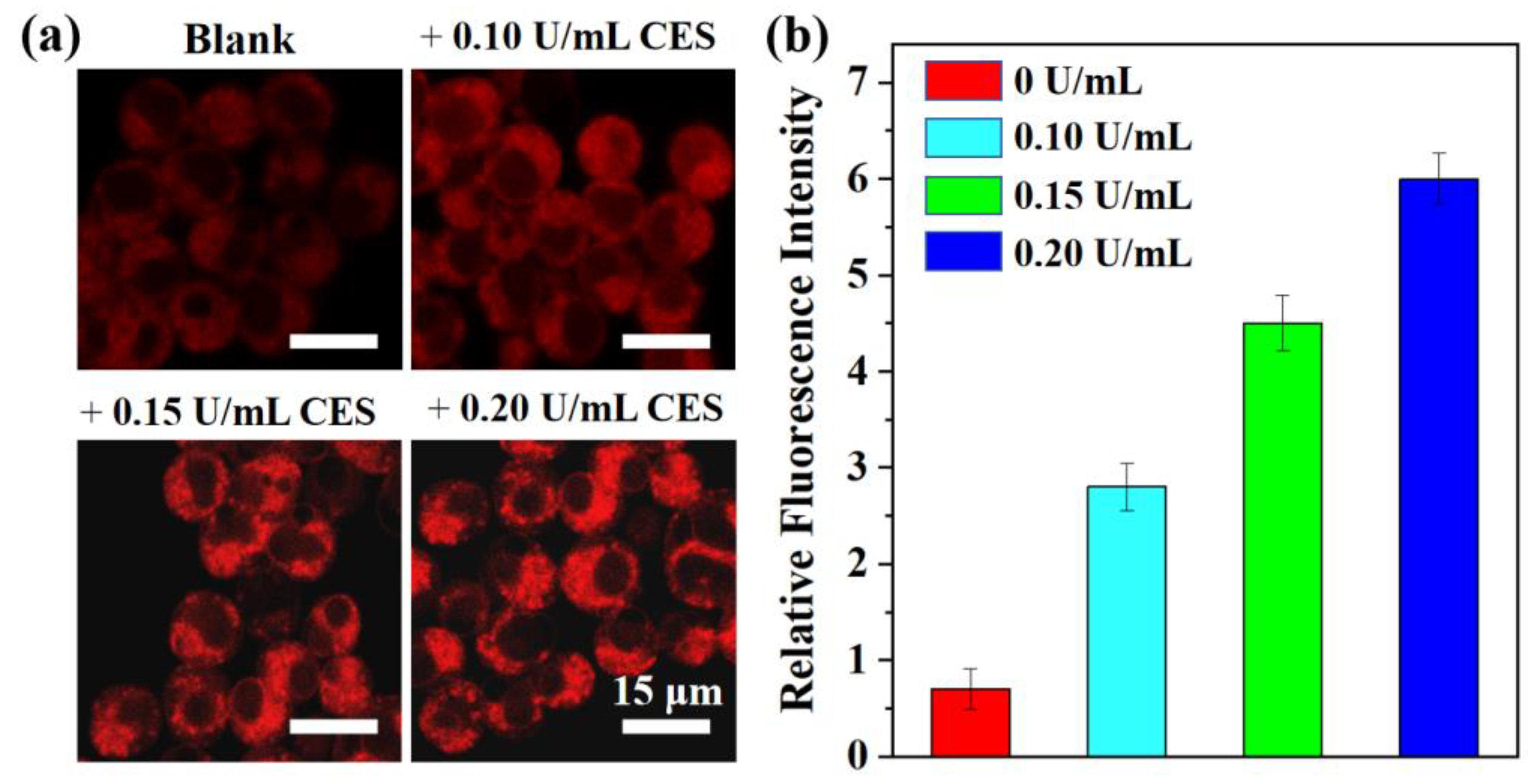

Figure 5.

(a) Confocal imaging of the different concentrations of CEs in living HepG2 cells. λex = 560 nm; λem = 650–750 nm. (b) Relative intensities of cell imaging. Error bars are ± SD (n = 3).

Figure 5.

(a) Confocal imaging of the different concentrations of CEs in living HepG2 cells. λex = 560 nm; λem = 650–750 nm. (b) Relative intensities of cell imaging. Error bars are ± SD (n = 3).

Figure 6.

Confocal imaging of CEs in living HepG2 cells. (a-c) Untreated cells. (d-f) Cells incubated with probe TTAP−AB (5 μM) for 1 h. (g-i) Cells successively treated with 5-FU (100 μM) for 6 h and TTAP−AB (5 μM) for 1 h. (j-l) Cells successively treated with AEBSF (1 mM) for 2 h and TTAP−AB (5 μM) for another 1 h. Incubation temperature, 37 ℃; λex = 560 nm, λem = 650–750 nm.

Figure 6.

Confocal imaging of CEs in living HepG2 cells. (a-c) Untreated cells. (d-f) Cells incubated with probe TTAP−AB (5 μM) for 1 h. (g-i) Cells successively treated with 5-FU (100 μM) for 6 h and TTAP−AB (5 μM) for 1 h. (j-l) Cells successively treated with AEBSF (1 mM) for 2 h and TTAP−AB (5 μM) for another 1 h. Incubation temperature, 37 ℃; λex = 560 nm, λem = 650–750 nm.

Figure 7.

Imaging the dynamic change of CEs levels in living zebrafish. Cells were stained with TTAP−AB (5 μM) only as a control (a, e), and with 50 μM 5-FU (b, f), with 100 μM 5-FU(c, g), with 5-FU (100 μM) and AEBSF (1 mM) (d, h), respectively. λex = 560 nm; λem = 650–750 nm.

Figure 7.

Imaging the dynamic change of CEs levels in living zebrafish. Cells were stained with TTAP−AB (5 μM) only as a control (a, e), and with 50 μM 5-FU (b, f), with 100 μM 5-FU(c, g), with 5-FU (100 μM) and AEBSF (1 mM) (d, h), respectively. λex = 560 nm; λem = 650–750 nm.

Figure 8.

(a) Real-time imaging of mice injecting with PBS (100 μL) and probe TTAP−AB (100 μL, 200 μM). (b) Ex vivo imaging of the major organs in mice dissected after euthanasia. (c) Real-time imaging of the liver tumor injecting with TTAP−AB (20 μL, 100 μM). (d) Ex vivo imaging of the tumour cut from the mouse body after euthanasia. λex = 600 nm, λem = 650–750 nm.

Figure 8.

(a) Real-time imaging of mice injecting with PBS (100 μL) and probe TTAP−AB (100 μL, 200 μM). (b) Ex vivo imaging of the major organs in mice dissected after euthanasia. (c) Real-time imaging of the liver tumor injecting with TTAP−AB (20 μL, 100 μM). (d) Ex vivo imaging of the tumour cut from the mouse body after euthanasia. λex = 600 nm, λem = 650–750 nm.