1. Introduction

Photodynamic therapy is a selective process in which photosensitizer molecules absorb the appropriate wavelength of light and initiate the photoactivation process to produce toxic substances, thus leading to apoptosis or necrosis of pathological tissue cells[

1,

2]. Photodynamic therapy (PDT) has attracted extensive attention from researchers due to its advantages such as non-invasive, spatiotemporal controllability, and not easy to induce drug resistance [

3,

4,

5]. In the PDT process, the photosensitizer transitions from the ground state to a single reexcited state by absorbing photons of a specific wavelength, and then through intersystem translocation to a triple excited state. The excitons of the triple excited state then undergo energy transfer (type II photoreaction) or electron transfer (type I photoreaction) with the surrounding oxygen molecules or biomolecules. Biotoxic reactive oxygen species (ROS) are generated to achieve killing and treatment [

6,

7].

1O

2 generated by type II light reaction can oxidize major biomolecules of nuclear membrane and cell membrane, such as unsaturated lipids and amino acids of proteins, and cause cell apoptosis, so

1O

2 is toxic [

8].

Although PDT possesses the aforementioned advantages, achieving enhanced clinical efficacy remains a significant challenge. In this regard, precise selection and design of photosensitizers play a crucial role in determining the therapeutic outcomes of PDT [

9]. The ability of traditional organic small molecules to transduce between systems has great limitations compared with excessive metal complexes. Iridium complexes, compared to other transition metal complexes, exhibit excellent photochemical and physical stability, large Stokes shift, and high intersystem crossover ability [

10]. Consequently, they have emerged as extensively utilized transition metal complex materials across various domains such as bioimaging, electroluminescence, and photodynamic therapy [

11,

12,

13,

14,

15]. Notably, iridium complexes have been extensively investigated as photosensitizers in photodynamic therapy [

16,

17]. For instance, we successfully synthesized UCNPs@Ir-2-N—a near-infrared absorbing photosensitizer—by combining an AIE iridium complex with upconversion nanoparticles (UCNPs). This study demonstrates the promising application potential of metal iridium complex PSs in PDT [

18].

Traditional small molecule photosensitizers, such as porphyrins[

19], typically possess large planar conjugated structures and tend to aggregate in aqueous environments due to π-π interactions between molecules. This aggregation-induced quenching (ACQ) phenomenon significantly diminishes their photosensitization ability and severely limits their practical applications [

20,

21]. Furthermore, the fluorescence emitted by conventional photosensitizers is usually non-luminescent, leading to reduced imaging sensitivity [

22,

23] and substantial constraints on the clinical application of many PSs in photodynamic therapy (PDT). In 2001, Academician Tang's research group discovered an opposing phenomenon to ACQ: under dilute solution conditions, these photosensitizers emit minimal light but exhibit enhanced emission upon concentration [

24]. Unlike ACQ-based photosensitizers, those with aggregation-induced luminescence (AIE) properties generally possess non-planar structures. In the aggregated state, limited intramolecular motion reduces non-radiative energy dissipation while enhancing fluorescence emission and sensitizing a significant amount of reactive oxygen species (ROS), thereby offering substantial advantages for image-guided PDT [

25,

26,

27]. However, there are few examples of iridium complexes with AIE properties used in photodynamic therapy. Therefore, the development of iridium-based AIE-active photosensitizers holds great significance for advancing PDT applications.

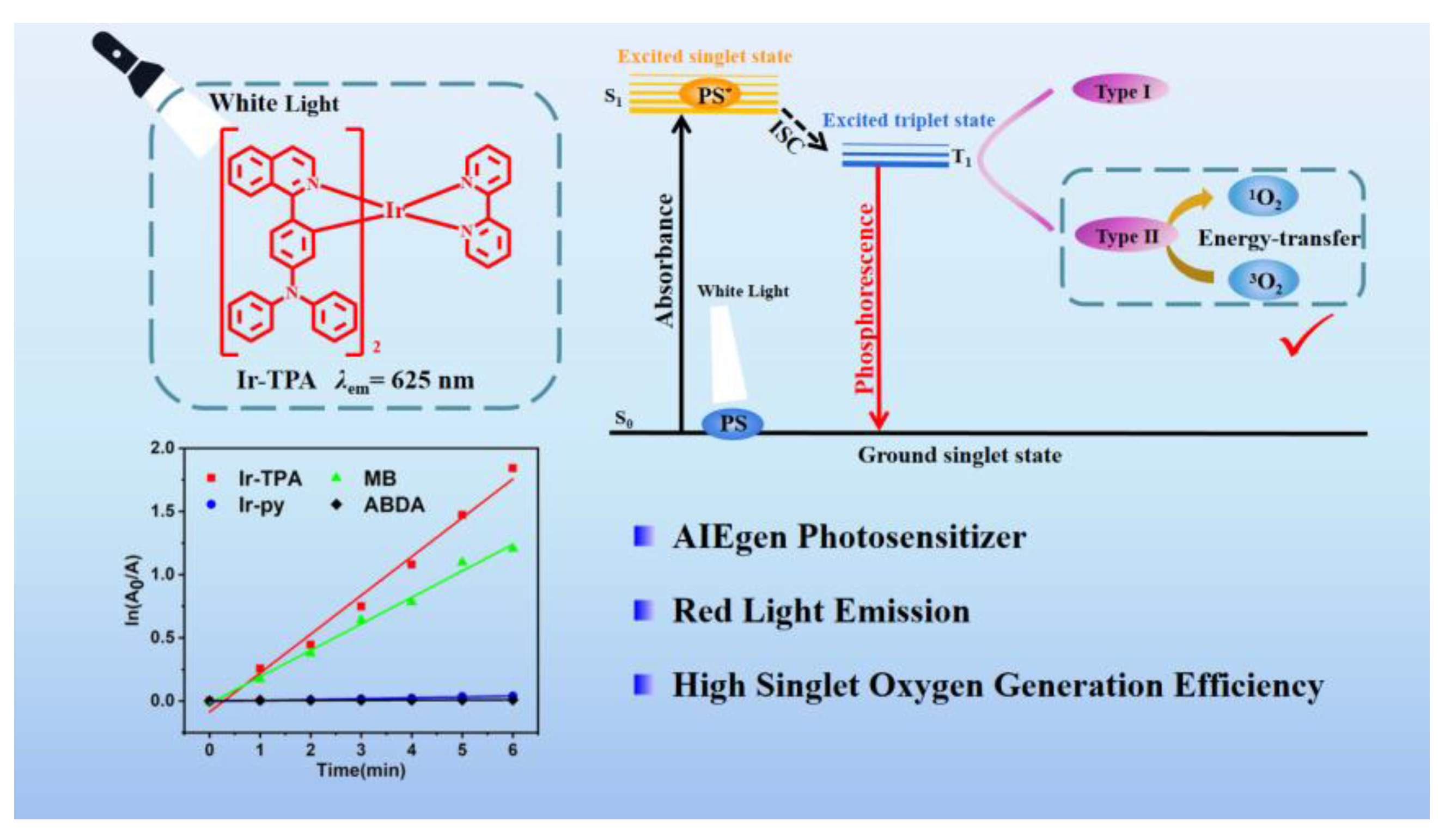

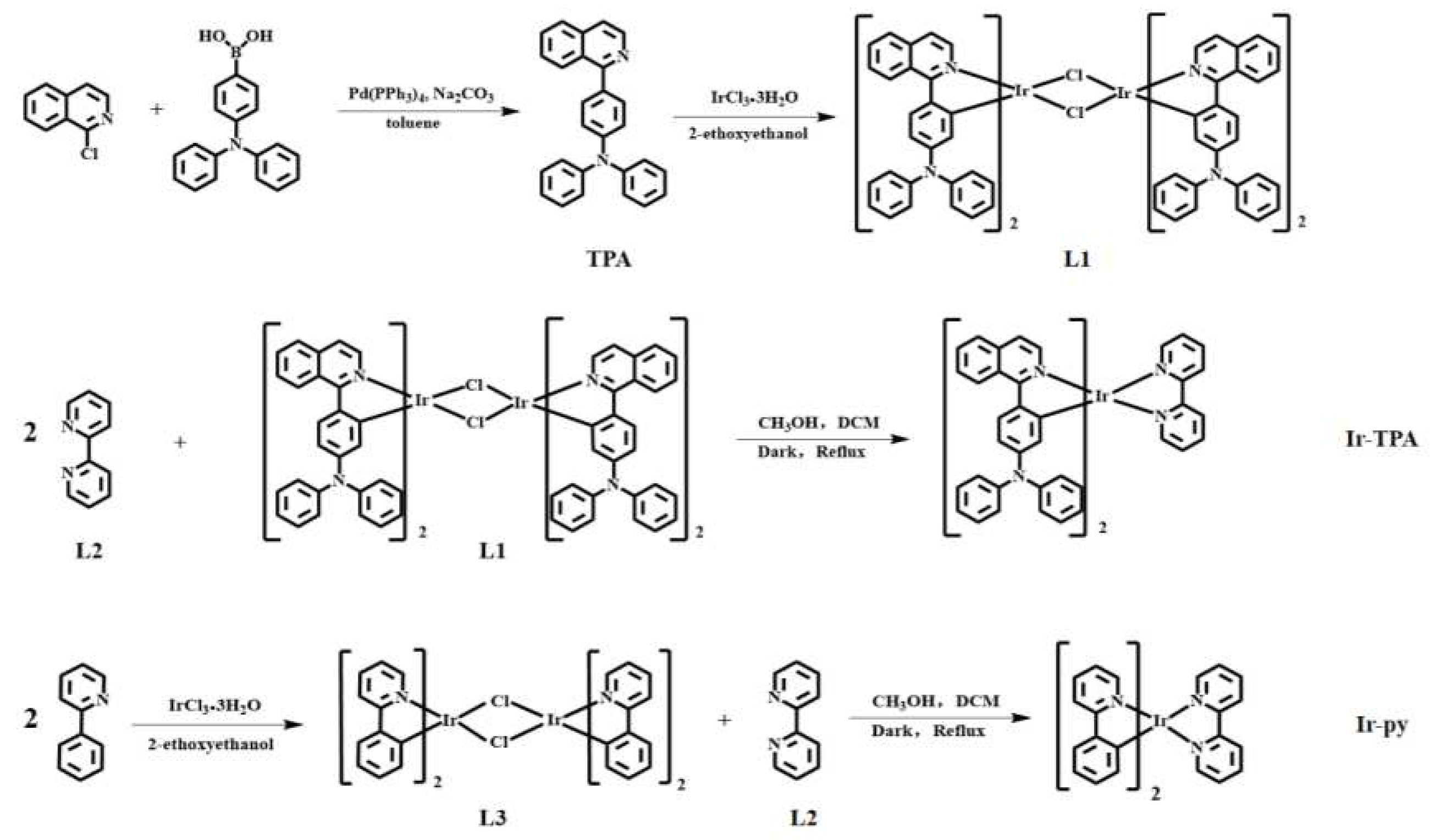

In this study, we developed and synthesized an iridium complex called Ir-TPA by incorporating a quinoline triphenylamine ligand. We conducted comprehensive investigations on the photophysical properties, AIE characteristics, spectral properties, and singlet oxygen generation capacity of Ir-TPA. As scheme 1, Our findings demonstrate that Ir-TPA exhibits excellent optical properties, displays remarkable AIE behavior, and possesses strong capability in generating reactive oxygen species. This research confirms the significant potential of AIE properties in enhancing the effectiveness of photodynamic therapy and presents a fresh perspective on utilizing iridium complexes in the field of photodynamic therapy.

Scheme 1.

Structure of Ir-TPA and schematic diagram of Ir-TPA producing singlet oxygen.

Scheme 1.

Structure of Ir-TPA and schematic diagram of Ir-TPA producing singlet oxygen.

2. Results and Discussion

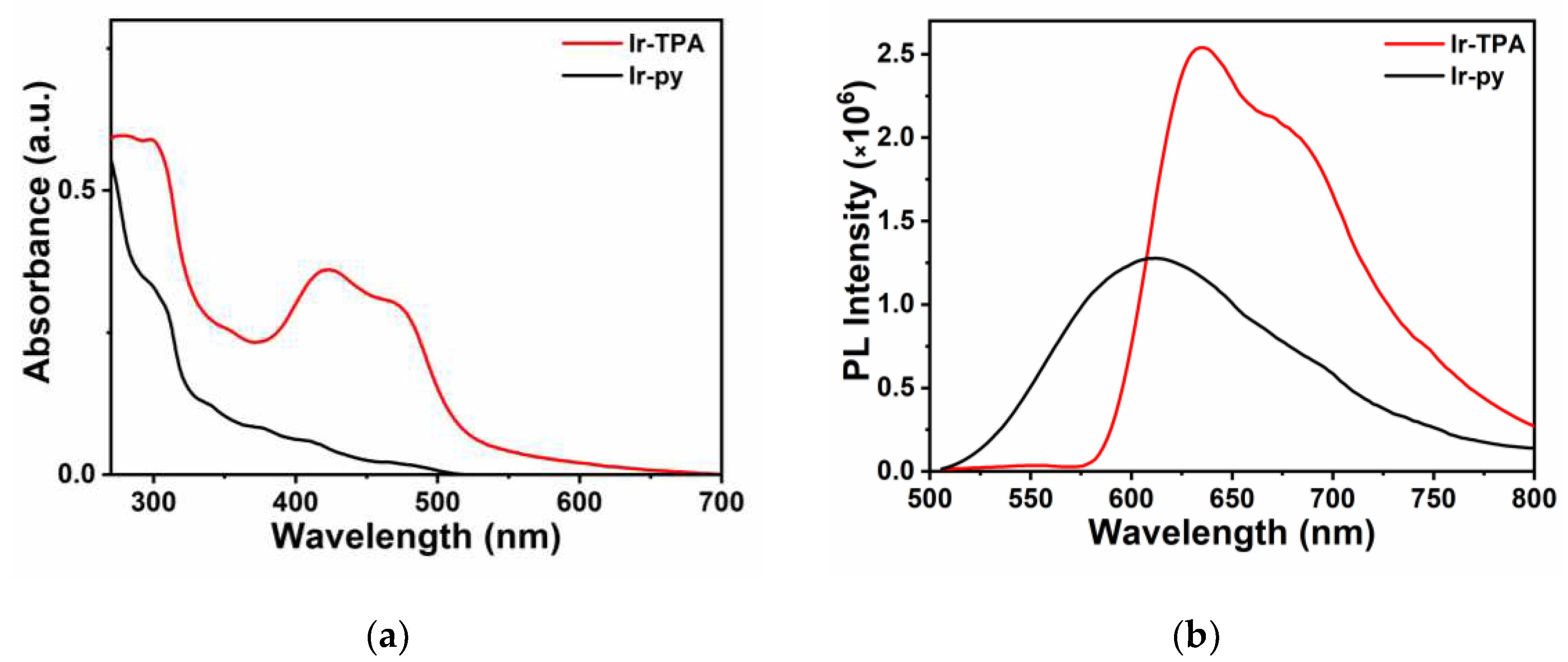

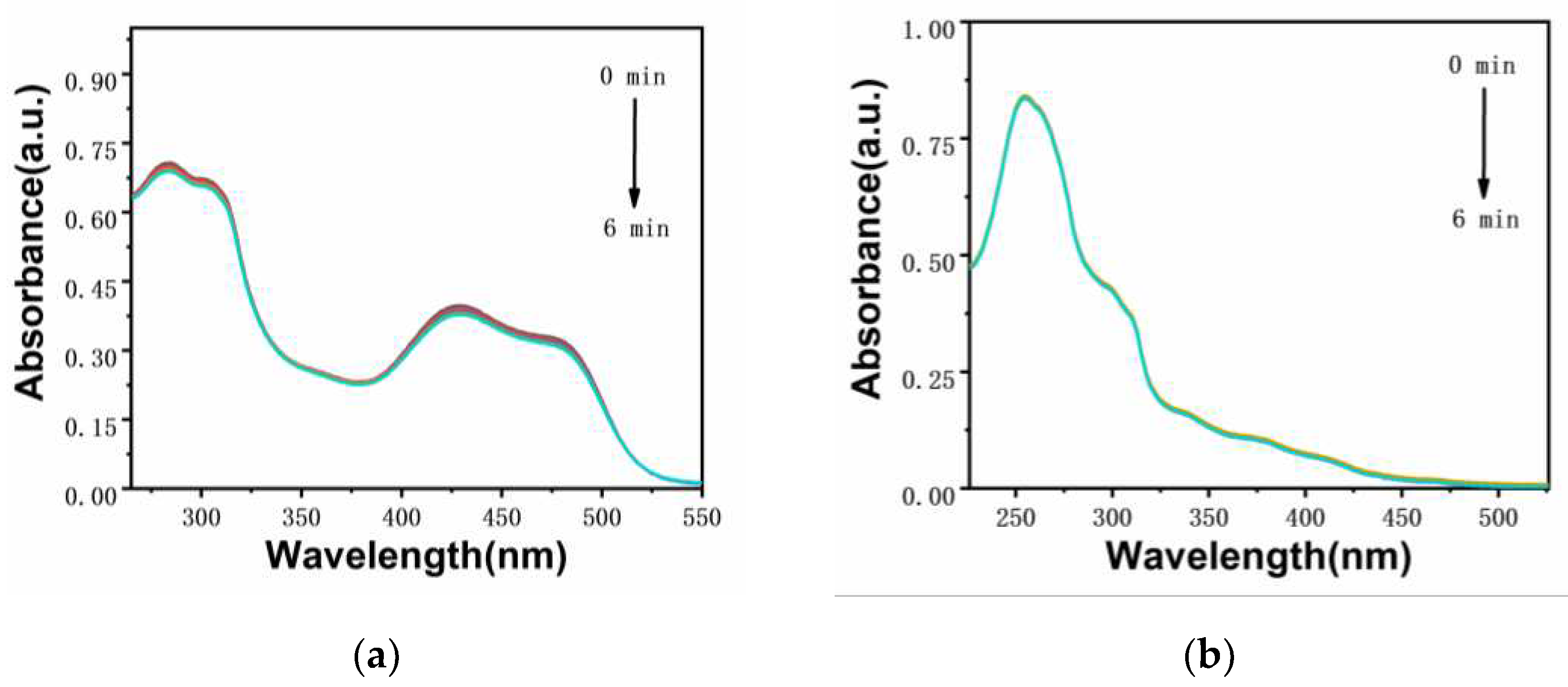

2.1. Analysis of photophysical properties of complexes

The photophysical properties of

Ir-TPA and

Ir-py were analyzed by ultraviolet absorption and fluorescence emission spectra. As shown in

Figure 1, similar to the iridium complexes reported in the literature,

Ir-TPA has two characteristic absorption peaks in a certain wavelength range. There is a strong characteristic absorption peak in the wavelength range of 250 ~ 350 nm, which is caused by the central charge (

1LC, π-π*) transition of the ligand in the metal iridium complex. There is a weak absorption band in the 350 nm to visible light band, which can be attributed to metal-ligand charge transfer transition (MLCT) and ligand-ligand charge transfer (LLCT) of the metal iridium complex [

28]. It can be clearly seen from the figure that the molar absorption coefficient of

Ir-TPA was significantly enhanced compared with

Ir-py after the introduction of the quinoline triphenylamine ligand (

Table 1). Especially in the 425 nm visible region, the molar coefficient of

Ir-TPA is 35900 m

-1cm

-1, which is eight times that of

Ir-py. It can be shown that the absorption peak of iridium complex is obviously enhanced after the introduction of quinoline triphenylamine ligand. Subsequently, we determined the photoluminescent quantum yields (PLQYs) and excited state lifetimes of

Ir-TPA and

Ir-py, and summarized the corresponding photophysical data in

Table 1. It can be seen from the data in the table that

Ir-TPA and

Ir-py have good photophysical properties.

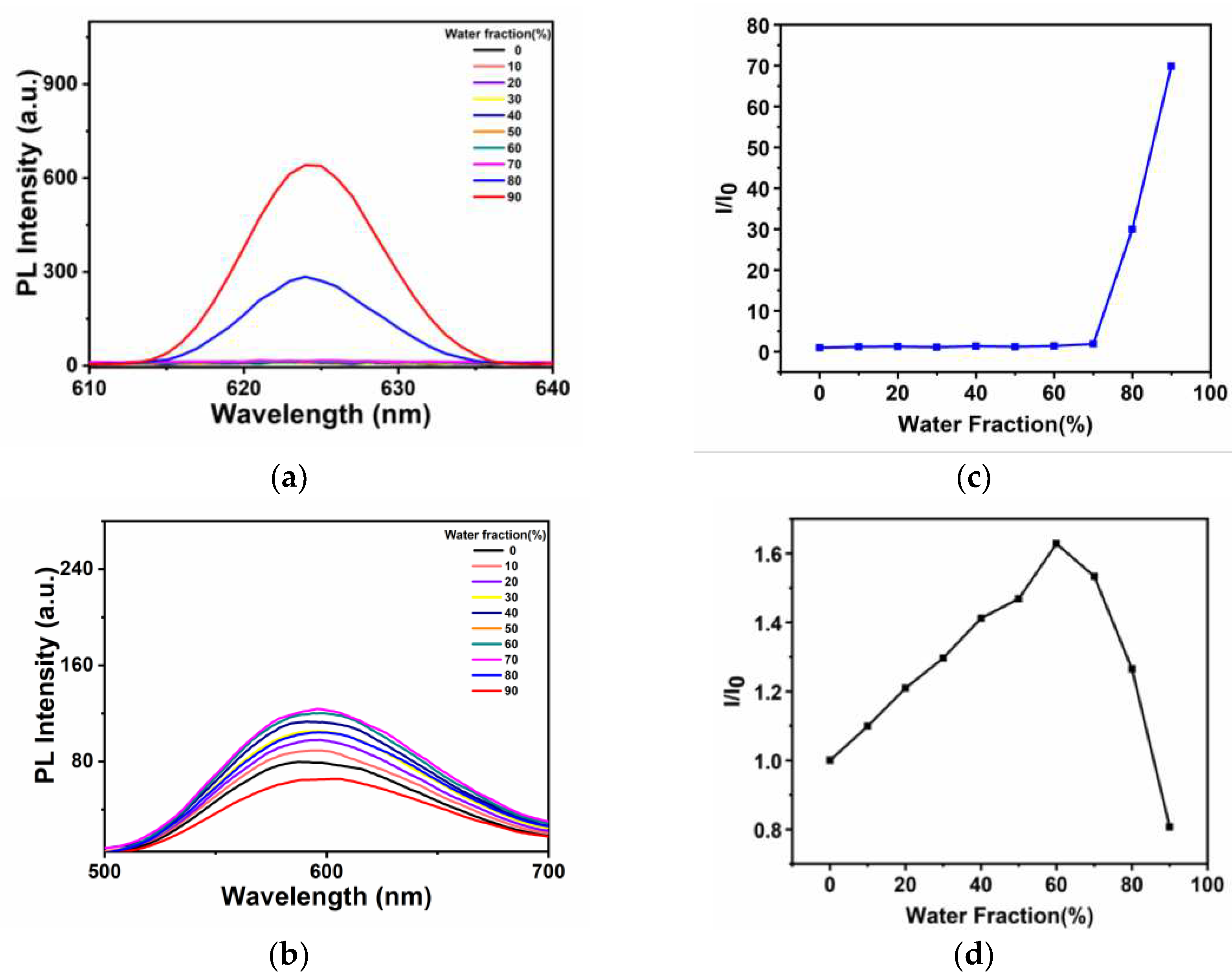

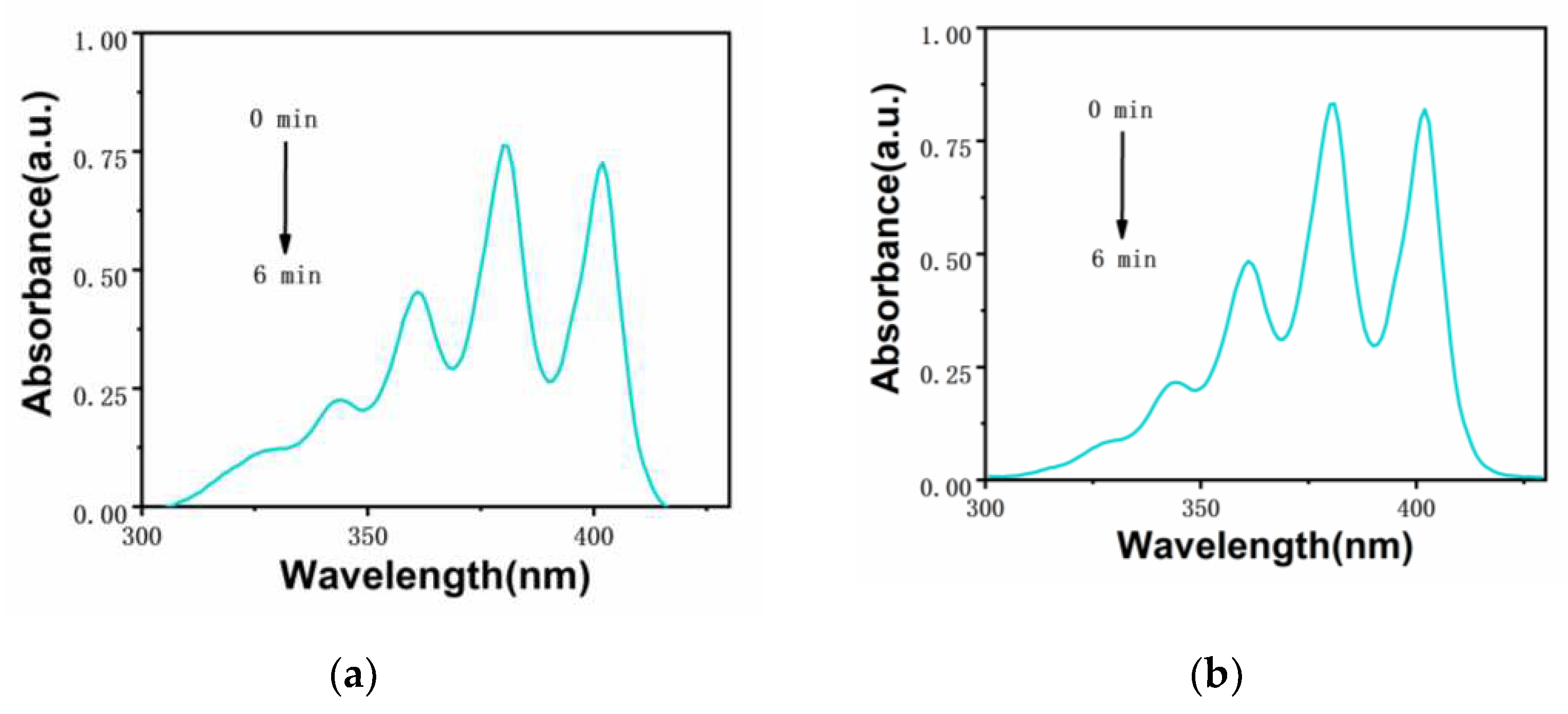

2.2. Analysis of AIE properties of complexes

The AIE properties of

Ir-TPA and

Ir-py were analyzed in CH

3CN and water mixed system solution (water content ranged from 0 to 99%). As shown in

Figure 2,

Ir-py exhibited weak emission in pure CH

3CN solution, but with the increase of water content, the luminescence gradually weakened, showing obvious aggregation-induced quenching phenomenon. Iridium complexe

Ir-TPA was obtained by using quinoline triphenylamine derivatives as cyclometalated ligands, which basically did not emit light in pure CH

3CN. The luminescence of

Ir-TPA increased gradually with the increase of water content of bad solvent. When the water content of the mixed solution reaches 80%,

Ir-TPA emits bright red light, and

Ir-TPA has typical AIE characteristics.

Ir-TPA showed more emission redshift than Ir-py due to the better conjugation of cyclometal ligands derived from quinoline triphenylamine. Ir-TPA exhibit excellent red light emission and larger Stokes shifts value, indicating that in future biological experiments, autofluorescence interference will be effectively avoided, and the signal-to-noise ratio of imaging will be improved, which has a broad prospect in future biological applications.

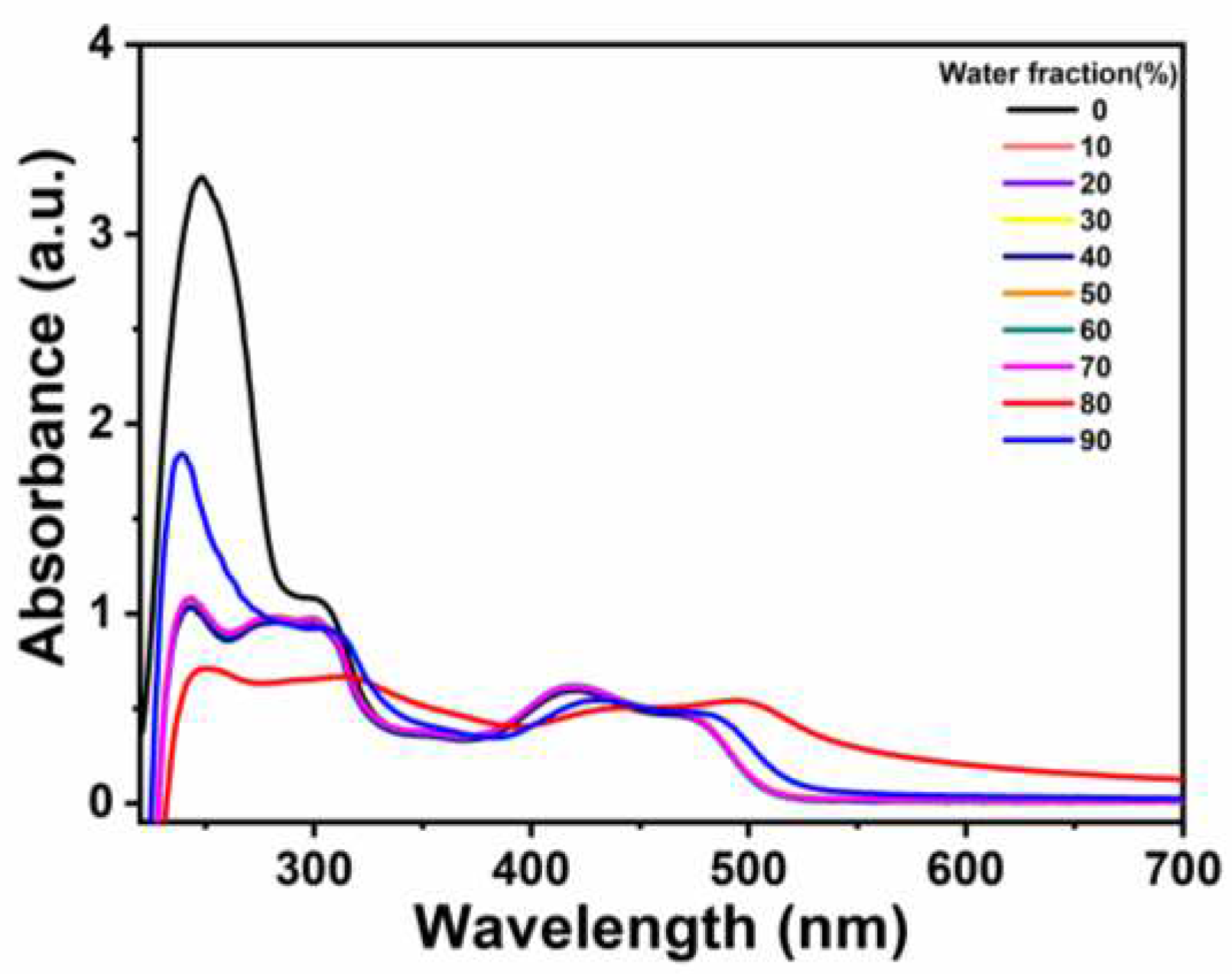

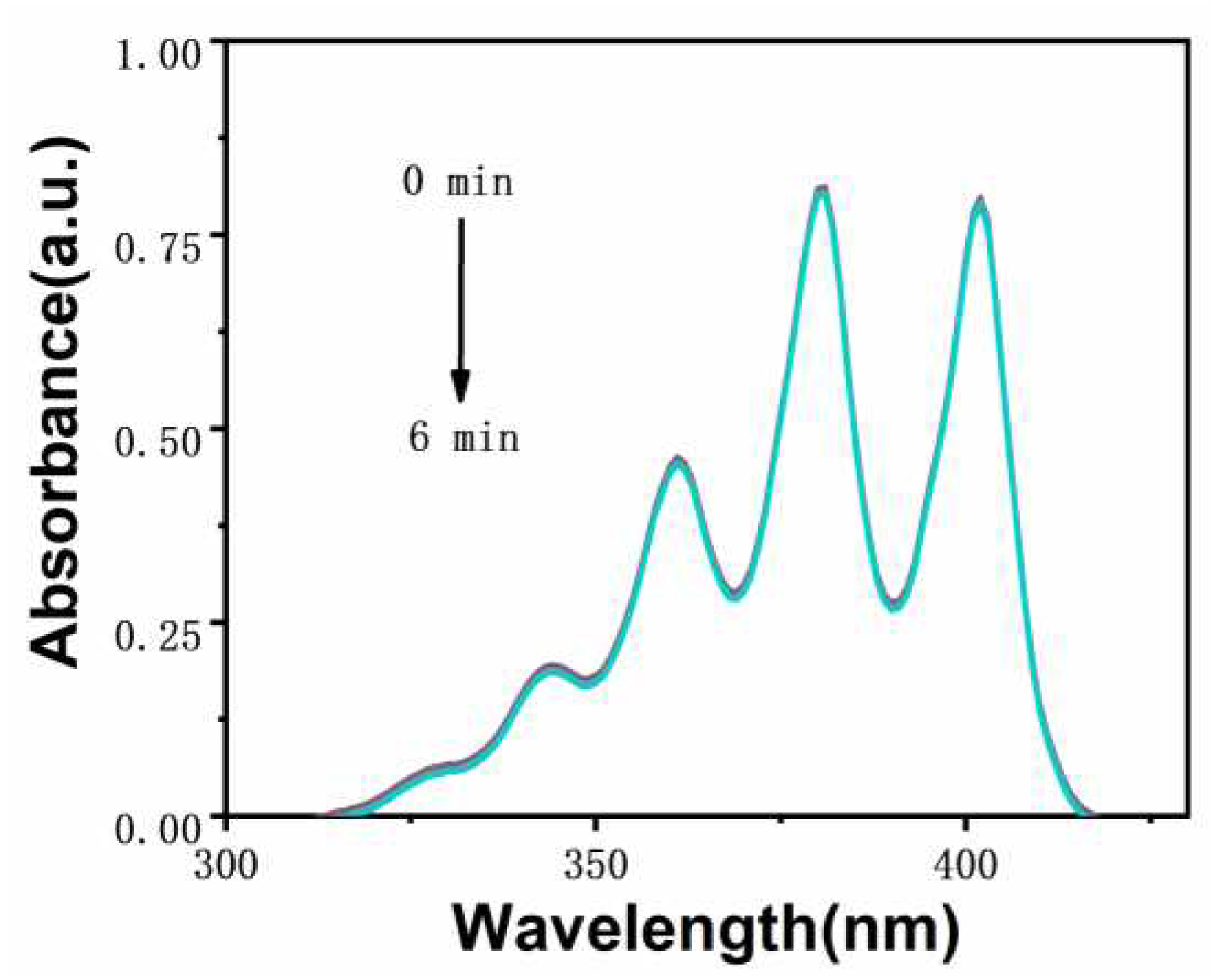

Then we further investigated the AIE phenomena of

Ir-TPA by UV-Vis absorption spectra. As can be seen from

Figure 3, with the gradual increase of water content in the system, the tail of the absorption spectrum slightly warped, indicating that the Mi scattering phenomenon occurred [

29]. Through the above experimental results, we can conclude that the complexe

Ir-TPA have good AIE properties due to the emission enhancement caused by aggregation in poor solvents.

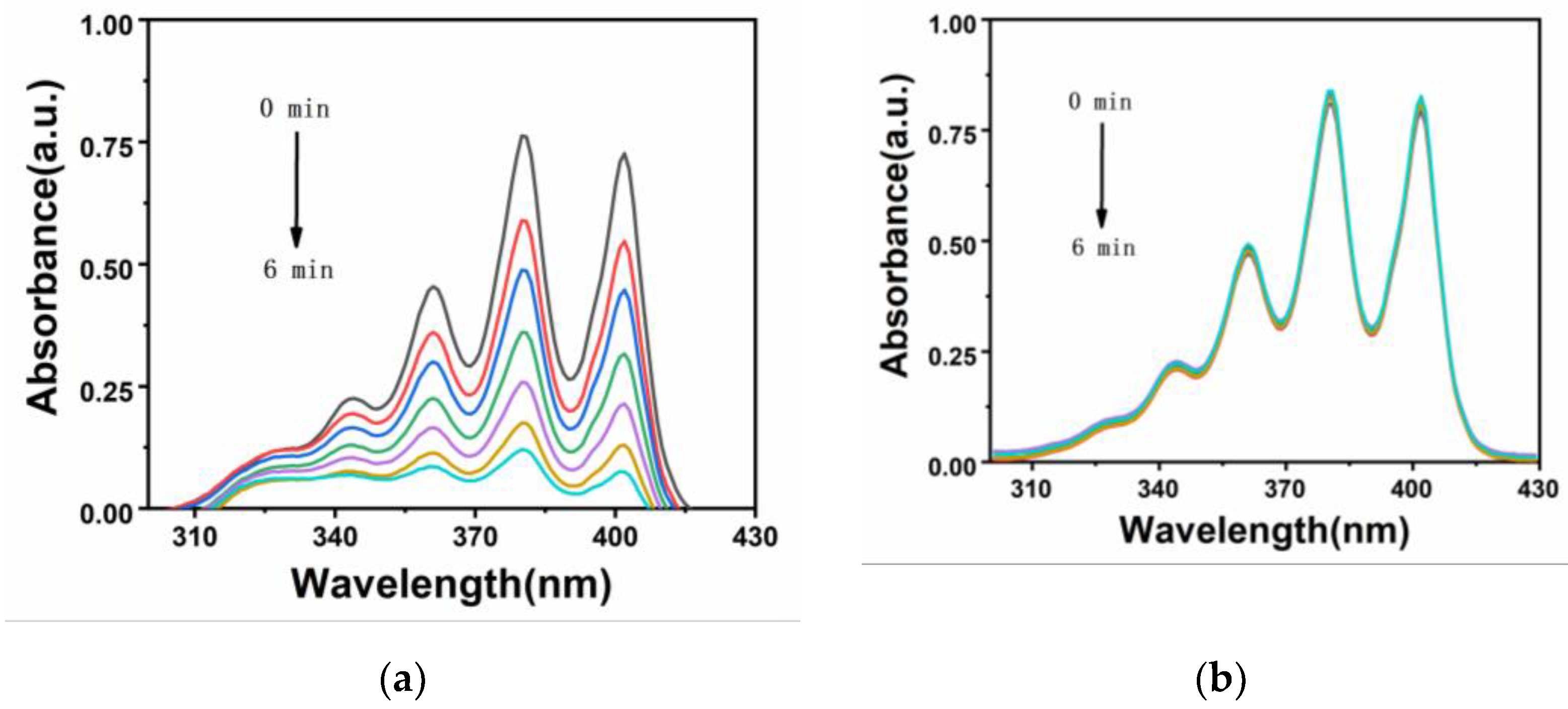

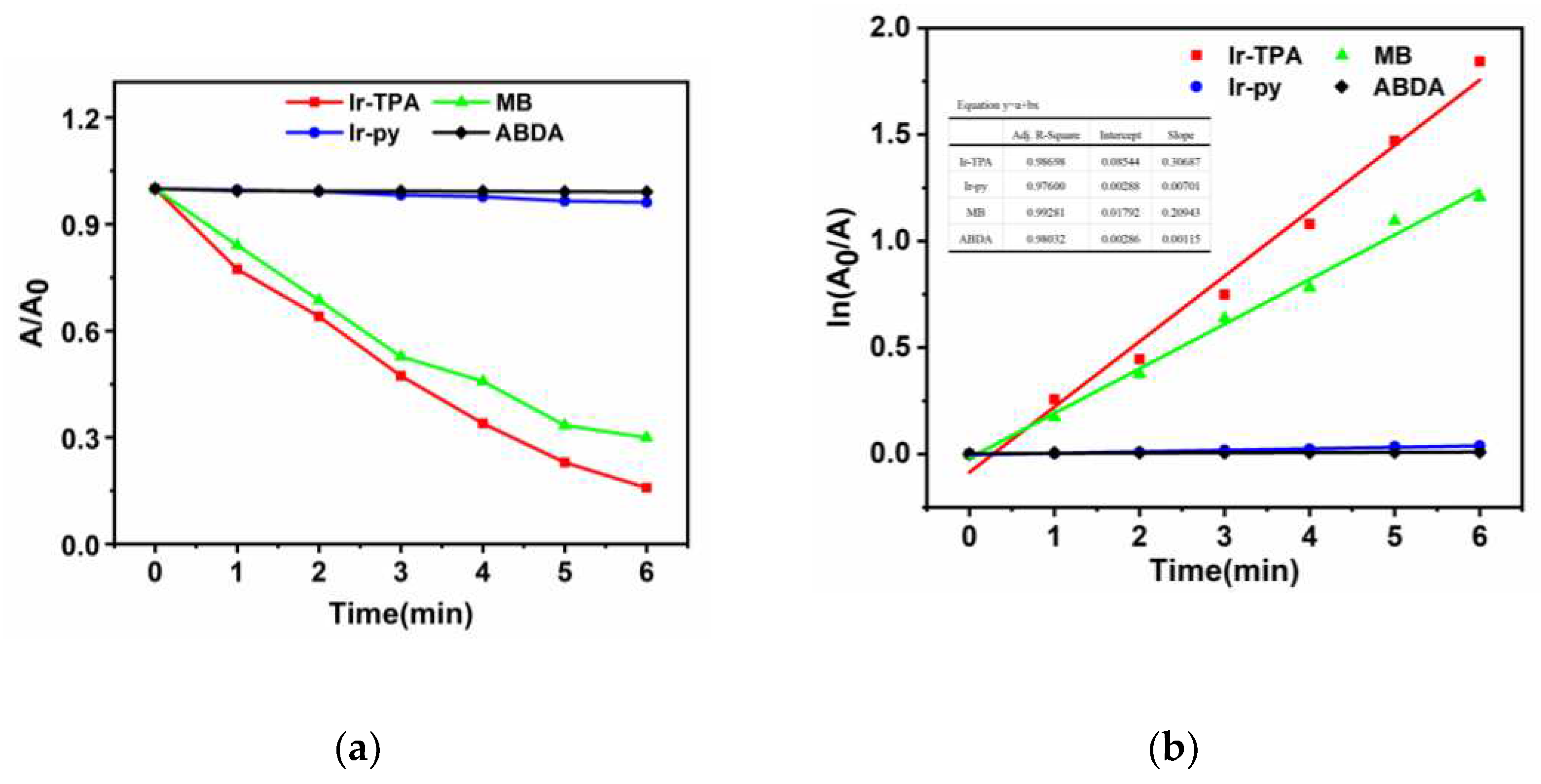

2.3. Analysis of singlet oxygen generation capacity in solution

The ability of photosensitizer to produce singlet oxygen is very important for the effect of photodynamic therapy. The singlet oxygen production capacity of two iridium complexes

Ir-TPA and

Ir-py at CH

3CN:H

2O (V:V=1:9) was evaluated by monitoring the absorbance change of ABDA at 380 nm using ABDA as an indicator. As shown in

Figure 4,

Figure 5 and

Figure 6, for 1) the light group containing PSs; 2) Unilluminated group containing PSs and ABDA; 3) For the ABDA light group alone, the absorption intensity basically did not change during the time of illumination 360 s, which proves that

Ir-TPA and

Ir-py have good light stability. As shown in

Figure 7, when irradiated with a white LED lamp, the absorption of

Ir-TPA and

Ir-py at 380 nm is significantly reduced, which proves the production of singlet oxygen under the illumination condition. As shown in

Figure 8, the singlet oxygen generation capacity of

Ir-TPA and

Ir-py both conform to the first-order kinetic equation. The higher the slope, the stronger the singlet oxygen generation capacity, and the singlet oxygen generation efficiency is

Ir-TPA> Methylene Blue (MB)>

Ir-py. As shown in

Table 2, using methylene blue as the reference, the

1O

2 quantum yield of

Ir-TPA is as high as 83.5%, indicating that

Ir-TPA can efficiently produce singlet oxygen, and they will play an important role in the application of PDT cancer as Ps.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. General Information

Reagents and solvents should be used as received from the supplier. Unless otherwise specified, all purification is performed using 200-300 mesh silica gel from the supplier by column chromatography. The structure was confirmed by Bruker AV600 NMR spectrometer and Bruker autoFlex III mass spectrometer. A Shimadzu UV-3100 spectrophotometer was used for ultraviolet-visible experiments. The fluorescence emission spectra were measured by Edinburgh FLS920 steady-state transient fluorescence spectrometer.

3.2. Spectral test method

The spare solution of Ir-TPA and Ir-py (1 mM) was prepared in acetonitrile. The preparation method of the test solution is as follows: During the test, 30 μL Ir-TPA and Ir-py reserve solution, 270 μL acetonitrile and 2700 μL ultra-pure water are prepared into the test solution with a total volume of 3 mL.

3.3. Test method for singlet oxygen in solution

The efficacy of photodynamic therapy is evaluated by the level of singlet oxygen production in the solution. The 1O2 formation capacity of Ir-TPA/ Ir-py at CH3CN/ H2O=1/9 was evaluated using 9, 10-anthracenedi-bis (methylene) dicarboxylic acid (ABDA) as an indicator. After a certain time of light irradiation, the absorbance of ABDA at 380 nm was significantly reduced, indicating that the photosensitizer sensitized oxygen to produce 1O2. In this experiment, CH3CN/ H2O=1/9 solution containing Ir-TPA/ Ir-py (25 µM) was prepared and mixed with ABDA (30 µg.mL-1), and then exposed to white light (400-700 nm, 20 mW cm-2) for irradiation. The absorption intensity of ABDA at 380 nm was monitored every 60 s.

3.4. Synthesis and characterization of complexes

3.3.1. Synthesis of cyclometalated ligand TPA

Trianiline 4-borate (0.972 g, 3.36 mmol) and 1-chloroisoquinoline (0.496 g, 3.06 mmol) were dissolved in 30 mL toluene, and the catalyst tetrtriphenylphosphine palladium (0.177 g, 0.15 mmol) and 2 mol/L sodium carbonate solution 20 mL were added. The reaction was kept at 110℃ for 48 h in deoxygenated environment. After the reaction, the organic phase was extracted and dried with anhydrous magnesium sulfate, filtered and purified by silica gel column chromatography (dichloromethane/petroleum ether, 10/5). The product is a light yellow solid with a yield of 68%. 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.59 (d, J = 5.7 Hz, 1H), 8.23 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 1H), 7.87 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 1H), 7.69 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H), 7.62 – 7.59 (m, 3H), 7.56 (t, J = 7.7 Hz, 1H), 7.29 (t, J = 7.9 Hz, 4H), 7.21 (dd, J = 13.3, 8.1 Hz, 6H), 7.05 (d, J = 7.3 Hz, 2H).

3.3.2. Synthesis of L1

TPA (0.930 g, 2.5 mmol) and IrCl3·3H2O (0.317 g, 1 mmol) were dissolved in a mixed solution of 30 mL ethylene glycol ether and 10 mL water, and the reaction was continued for 24 h at 120℃ under nitrogen atmosphere. At the end of the reaction, water was added to the round-bottom flask and continued to stir for 30 min. The Brinell funnel was used for pumping and filtering, and the obtained solids were put into the oven for 24 h. After drying, the product became a deep red solid with a yield of 80%. The product is directly used in subsequent reactions.

3.3.5. Synthesis of Ir-TPA

L1 (0.194 g, 0.1 mmol) and L2 (0.0312 g, 0.2 mmol), methanol 20 mL and dichloromethane 20 mL were added as mixed solvents in single-mouth bottles, respectively. N2 was charged for protection under dark conditions, and reflux was carried out at 78℃for 8 h. At the end of the reaction, solid potassium hexafluorophosphate (1 mmol, 0.184 g) was added to the bottle, stirring for 45 minutes, and then the solvent was filtered and spun dry. The solid is dissolved in a small amount of dichloromethane, and the precipitation is obtained by filtration after reverse precipitation with petroleum ether. The crude product was purified by silica gel column chromatography (methylene chloride/acetone, 10/8). The product is a dark red solid with a yield of 35%. 1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.74 – 8.72 (m, 1H), 8.66 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 1H), 8.14 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 8.02 (d, J = 8.9 Hz, 1H), 7.88 (d, J = 5.2 Hz, 1H), 7.66 (t, J = 4.9 Hz, 3H), 7.46 – 7.44 (m, 1H), 6.98 (dd, J = 13.5, 6.8 Hz, 6H), 6.92 (d, J = 7.9 Hz, 4H), 6.81 (t, J = 6.6 Hz, 3H), 6.76 (dd, J = 8.8, 2.3 Hz, 1H). ESI-MS: [m/z] = 1091.3508 (calcd: 1091.35).

3.3.6. Synthesis of Ir-py

Dissolve L3 (0.1608 g, 0.1 mmol) and L2 (0.0312 g, 0.2 mmol), methanol 20 mL and dichloromethane 20 mL as mixed solvents in a single mouth bottle. N2 was charged for protection under dark conditions, and reflux was carried out at 78℃ for 8 h. At the end of the reaction, solid potassium hexafluorophosphate (1 mmol, 0.184 g) was added to the bottle, stirring for 45 minutes, and then the solvent was filtered and spun dry. The solid is dissolved in a small amount of dichloromethane, and the precipitation is obtained by filtration after reverse precipitation with petroleum ether. The yellow solid was obtained after drying, and the yield was 44%.1H NMR (600 MHz, DMSO) δ 8.89 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 1H), 8.28 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 2H), 7.95 – 7.91 (m, 2H), 7.88 (d, J = 5.3 Hz, 1H), 7.72 – 7.69 (m, 1H), 7.62 (d, J = 5.7 Hz, 1H), 7.16 (t, J = 6.6 Hz, 1H), 7.03 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 1H), 6.91 (t, J = 7.4 Hz, 1H), 6.20 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H). ESI-MS: [m/z] = 657.1636 (calcd: 657.16).

4. Conclusions

The iridium metal complex Ir-TPA, possessing aggregation-induced emission (AIE) properties, was designed and synthesized in this study. By incorporating quinoline triphenylamine metallized ligands, the AIE properties of Ir-TPA were enhanced, leading to a significant improvement in the complex's absorption capacity. Notably, the complex exhibited red light emission with a maximum wavelength of 625 nm. In-depth investigations were conducted on the photophysical properties, AIE characteristics, spectral features, and reactive oxygen generation capability of Ir-TPA. The results demonstrated that Ir-TPA displayed excellent optical properties along with pronounced AIE behavior and strong reactive oxygen species production ability. This work validates the substantial potential of AIE properties in enhancing photodynamic therapy efficacy and provides novel insights into the application of iridium complexes in this field.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, W.Z. and D.Z.; methodology, W.Z.; software, W.Z. and Z.W.; validation, W.Z., S.L. and Q.Z.; formal analysis, W.Z.; investigation, W.Z. and Z.W.; resources, W.Z.; data curation, W.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, W.Z.; writing—review and editing, W.Z. and D.Z.; project administration, W.Z.; funding acquisition, D.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by NSFC (Grant No. 52073045), the Development and Reform Commission of Jilin Province (2020C035-5), and Changchun Science and Technology Bureau (21ZGY19).

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Cheng H B, et al. Protein-Activatable Diarylethene Monomer as a Smart Trigger of Noninvasive Control Over Reversible Generation of Singlet Oxygen: A Facile, Switchable, Theranostic Strategy for Photodynamic-Immunotherapy [J]. J Am Chem Soc, 2021, 143(5): 2413-2422. [CrossRef]

- Kwiatkowski S, et al. Photodynamic therapy - mechanisms, photosensitizers and combinations [J]. Biomed Pharmacother, 2018, 10, 1098-1107. [CrossRef]

- Liu S, et al. Recent advances of AIE light-up probes for photodynamic therapy [J]. Chemical Science, 2021, 12(19): 6488-6506. [CrossRef]

- Kang M, et al. Evaluation of structure-function relationships of aggregation-induced emission luminogens for simultaneous dual applications of specific discrimination and efficient photodynamic killing of gram-positive bacteria [J]. Journal of the American Chemical Society, 2019, 141(42): 16781-16789. [CrossRef]

- Wang C,et al. A receptor-targeting AIE photosensitizer for selective bacterial killing and real-time monitoring of photodynamic therapy outcome [J]. Chemical Communications, 2022, 58(50): 7058-7061. [CrossRef]

- Zhao X, et al. Recent progress in photosensitizers for overcoming the challenges of photodynamic therapy: from molecular design to application [J]. Chemical Society Reviews, 2021, 50(6): 4185-4219. [CrossRef]

- Pham T C, et al. Recent strategies to develop innovative photosensitizers for enhanced photodynamic therapy [J]. Chemical Reviews, 2021, 121(21): 13454-13619. [CrossRef]

- Li X, et al. Phthalocyanines as Medicinal Photosensitizers: Developments in the Last Five Years [J]. Coordin Chem Rev, 2019, 379: 147-160. [CrossRef]

- Kenry, et al. Enhancing the Theranostic Performance of Organic Photosensitizers with Aggregation-Induced Emission [J]. Accounts of Materials Research, 2022, 3(7): 721-734. [CrossRef]

- Ma D, et al. Recent Progress in Sublimable Cationic Iridium(III) Complexes for Organic Light-Emitting Diodes [J]. Chem Rec, 2019, 19(8): 1483-1498. [CrossRef]

- Yang P, et al. Synthesis of pH-responsive cyclometalated iridium(III) complex and its application in the selective killing of cancerous cells [J]. Dalton Trans, 2021, 50(46): 17338-17345. [CrossRef]

- Zhou L,et al. Enhancing the ROS generation ability of a rhodamine-decorated iridium(iii) complex by ligand regulation for endoplasmic reticulum-targeted photodynamic therapy [J]. Chem Sci, 2020, 11(44): 12212-12220. [CrossRef]

- Han Z, et al. A Novel Luminescent Ir(III) Complex for Dual Mode Imaging: Synergistic Response to Hypoxia and Acidity of Tumor Microenvironment [J]. Chem Commun, 2020, 56(58), 8055-8058. [CrossRef]

- Gao F, et al. Photoactivated Nanosheets Accelerate Nucleus Access of Cisplatin for Drug-Resistant Cancer Therapy [J]. Adv Funct Mater, 2020, 30(49): 2001546. [CrossRef]

- Rashid, A., et al. Development and Application of Ruthenium(II) and Iridium(III) Based Complexes for Anion Sensing [J]. Molecules, 2023, 28(3). [CrossRef]

- Jiang J, et al. Enhancing Singlet Oxygen Generation in Semiconducting Polymer Nanoparticles Through Fluorescence Resonance Energy Transfer for Tumor Treatment [J]. Chem Sci, 2019, 10(19): 5085-5094. [CrossRef]

- Cabrera-González J, et al. Multinuclear Ru(ii) and Ir(iii) Decorated Tetraphenylporphyrins as Efficient PDT Agents [J]. Biomater Sci, 2019, 7(8): 3287-3296. [CrossRef]

- Liu S, et al. AIE-active iridium(III) complex integrated with upconversion nanoparticles for NIR-irradiated photodynamic therapy [J]. Chem Commun (Camb), 2022, 58(72): 10056-10059. [CrossRef]

- Tsolekile, et al. Porphyrin as Diagnostic and Therapeutic Agent [J]. Molecules, 2019, 24, 2669. [CrossRef]

- Jia S, et al.Design and structural regulation of AIE photosensitizers for imaging-guided photodynamic anti-tumor application [J]. Biomaterials Science, 2022, 10(16): 4443-4457. [CrossRef]

- Yan D, et al. Innovative Synthetic Procedures for Luminogens Showing Aggregation-Induced Emission [J]. Angew.Chem.Int. Ed., 2021, 60, 15724–15742. [CrossRef]

- Luby B M, et al. Advanced Photosensitizer Activation Strategies for Smarter Photodynamic Therapy Beacons [J]. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl, 2019, 58(9): 2558-2569. [CrossRef]

- Wu W, et al. Controllable Photodynamic Therapy Implemented by Regulating Singlet Oxygen Efficiency [J]. Adv Sci (Weinh), 2017, 4(7): 1700113-1700134. [CrossRef]

- Luo J, et al. Aggregation-induced emission of 1-methyl-1,2,3,4,5-pentaphenylsilole [J]. Chem. Commun., 2001, 1740-1741. [CrossRef]

- Zha M, et al. Recent advances in AIEgen-based photodynamic therapy and immunotherapy [J]. Advanced Healthcare Materials, 2021, 10 (24): 2101066. [CrossRef]

- Mei J, et al. Aggregation-induced emission: together we shine, united we soar! [J]. Chemical Reviews, 2015, 115(21): 11718-11940. [CrossRef]

- Xue K, et al. A sensitive and reliable organic fluorescent nanothermometer for noninvasive temperature sensing [J]. Journal of the American Chemical Society, 2021, 143(35): 14147-14157. [CrossRef]

- Ulbricht, C., et al. Recent Developments in the Application of Phosphorescent Iridium(III) Complex Systems [J]. Advanced Materials, 2009, 21(44): 4418-4441. [CrossRef]

- Xu, B., et al. Achieving very bright mechanoluminescence from purely organic luminophores with aggregation-induced emission by crystal design [J]. Chem Sci, 2016, 7(8): 5307-5312. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).