Submitted:

02 December 2024

Posted:

02 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

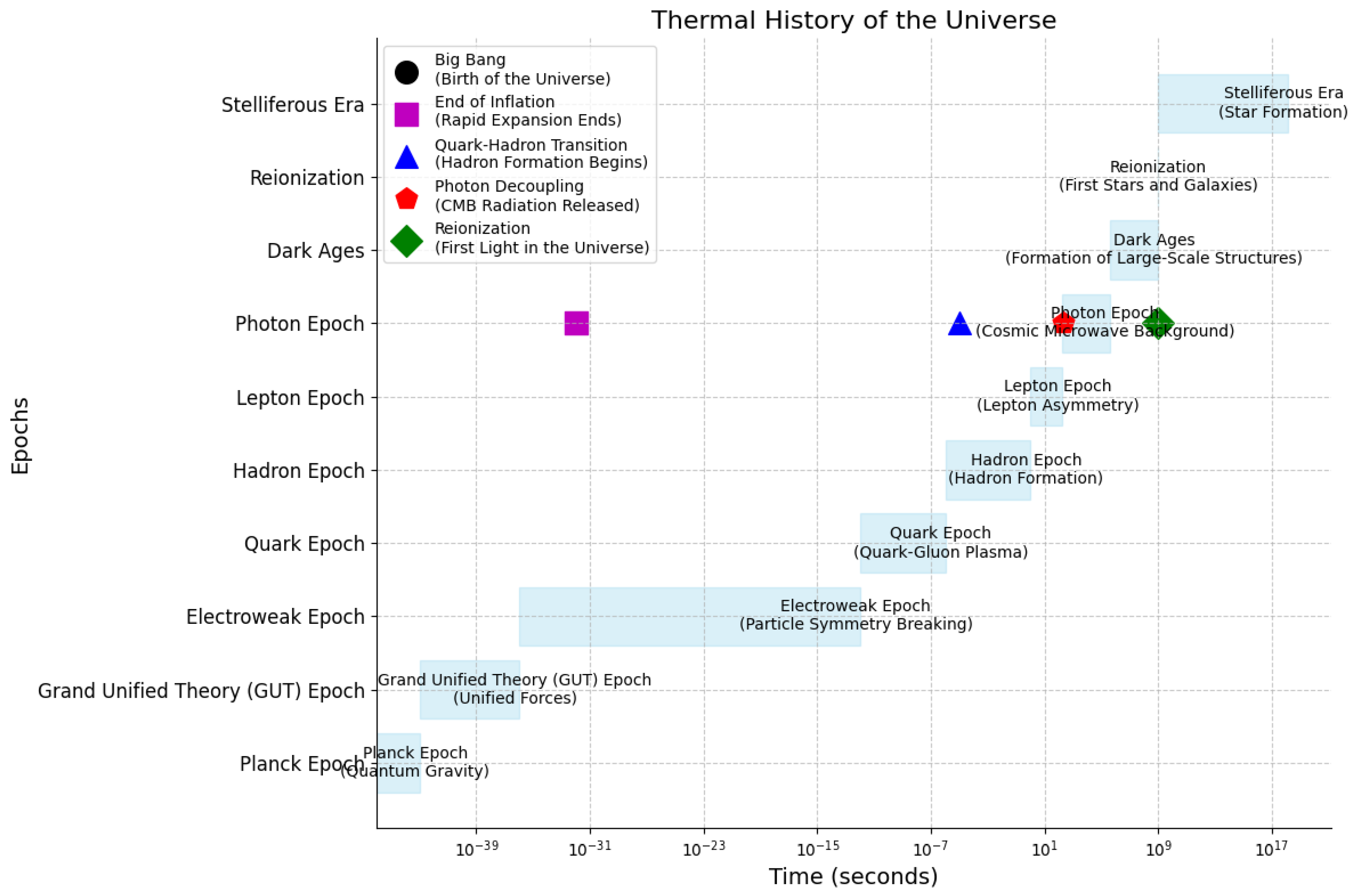

1. Introduction

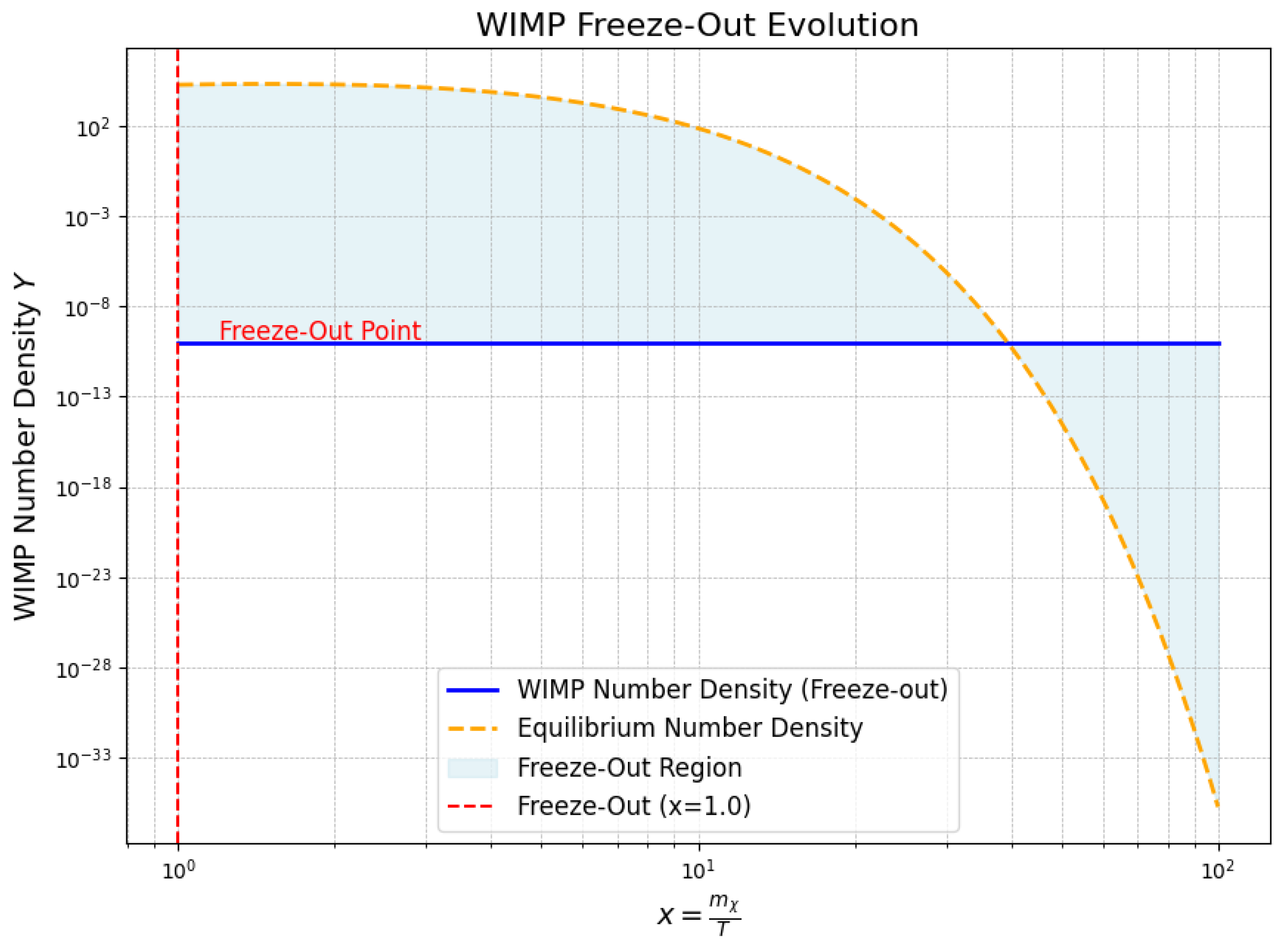

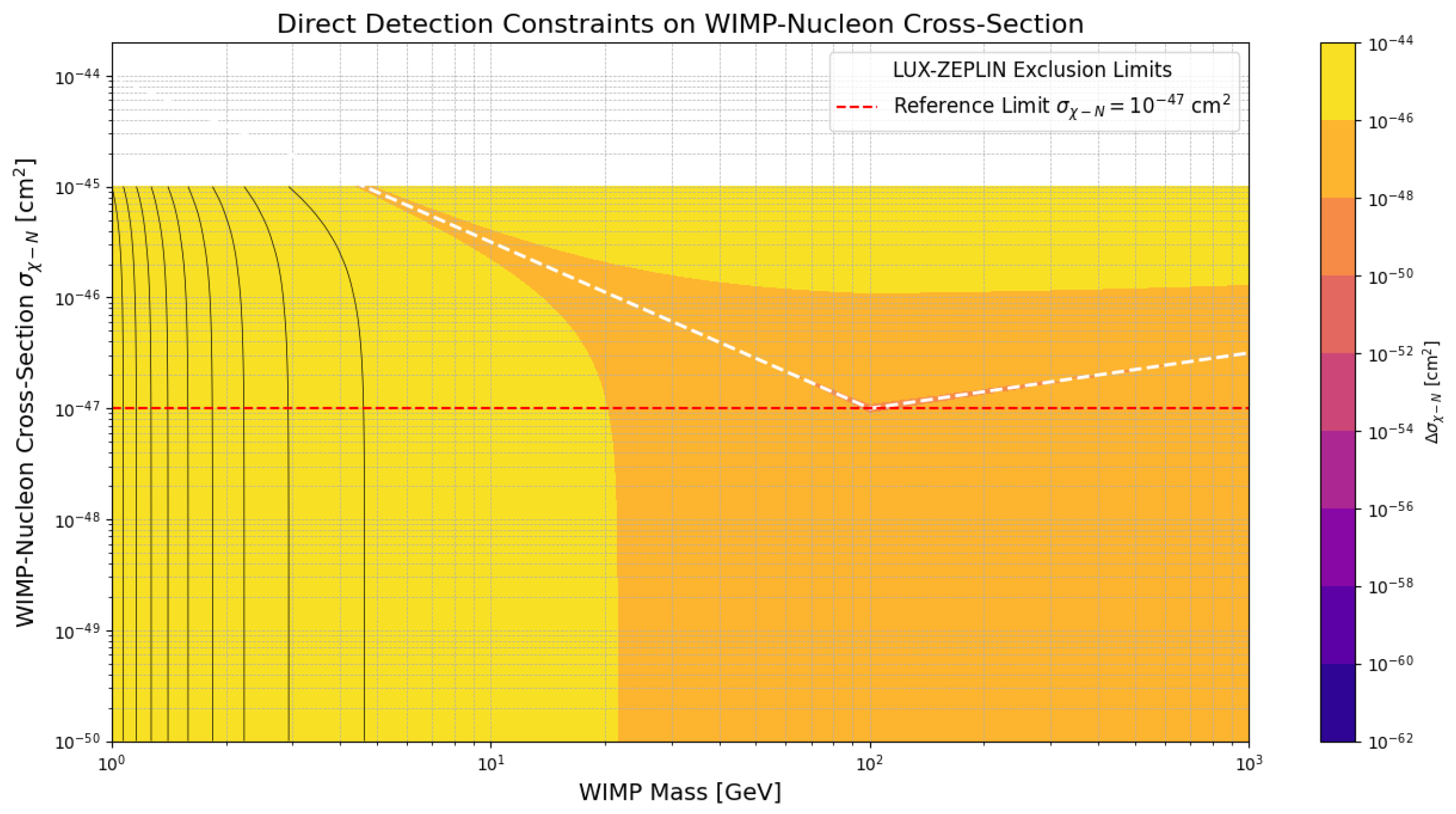

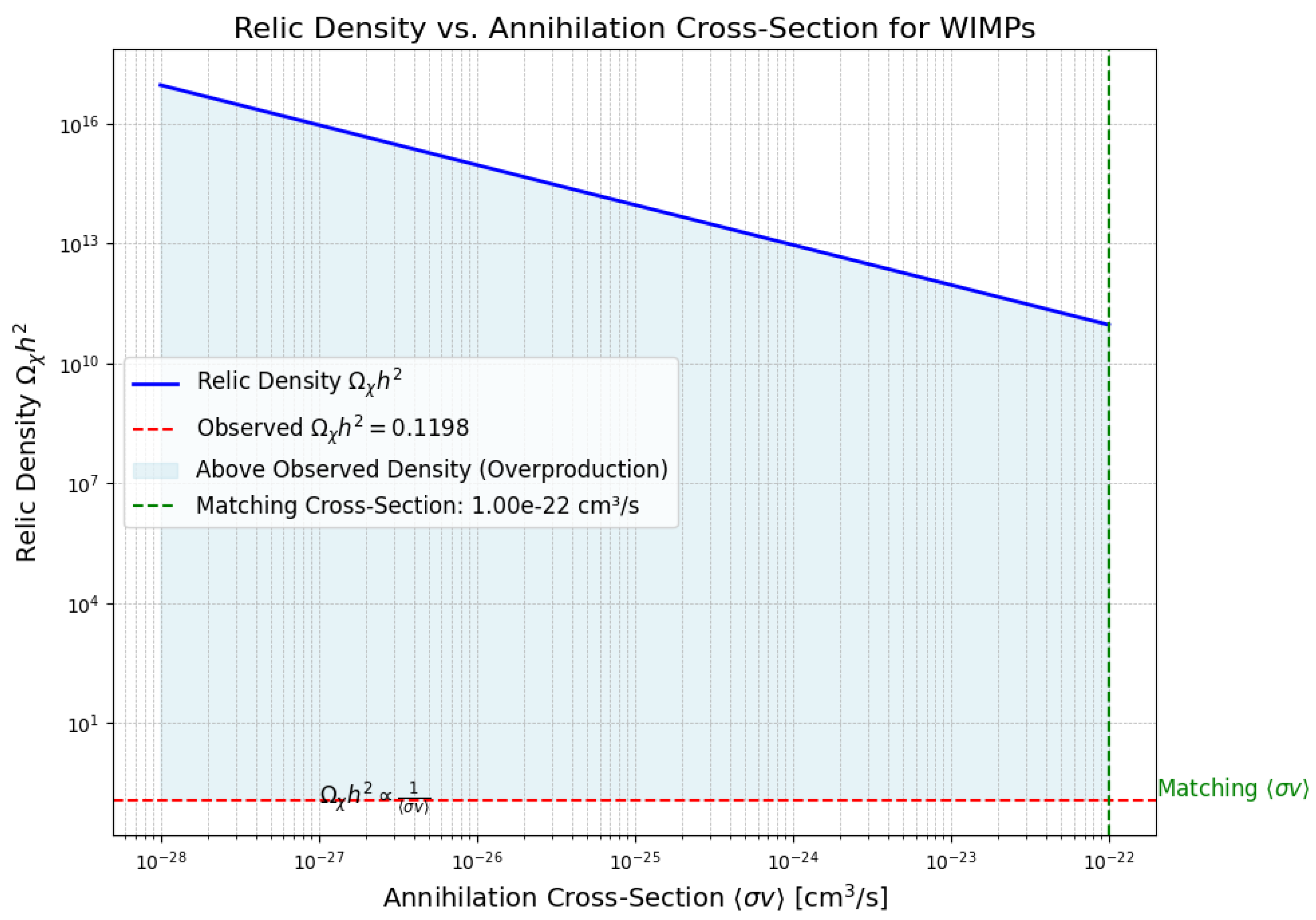

2. Quark-Gluon Plasma in the Early Universe

2.1. QCD Thermodynamics and QGP Formation

2.2. Transport Properties of QGP

2.3. Experimental Observables and Theoretical Models

2.4. Jet Quenching and Energy Loss Mechanisms

2.5. Cosmological Implications

3. Topological Structures in QCD and Their Role in Dark Matter Physics

3.1. Theoretical Foundations and Scale Symmetry Breaking

3.2. Gauge-Invariant Formulation of Confinement and Flux Tubes

3.3. Low-Energy Effective Models and Solitonic Solutions

3.4. Nambu–Jona-Lasinio Model and Dark Matter

3.5. Chiral Perturbation Theory and Dark Matter Models

3.6. Dark Matter Implications and Future Work

4. Classical Solutions in Effective Models of QCD and Their Relevance to Dark Matter

4.1. Skyrme Model: Topological Solitons as Analogues of Dark Matter

4.1.1. Topological Charge and Stability

4.1.2. Energy Density and Compactness

4.1.3. Skyrmion Clustering and Cosmological Implications

4.1.4. Extensions and Future Directions

- The production mechanisms of Skyrmions in the early universe [77].

- Gravitational wave signatures from Skyrmion clusters, which could provide a new observational probe for dark matter [93].

- The reconciliation of Skyrmion masses with current dark matter constraints, as Skyrmion mass distributions are typically non-thermal [77].

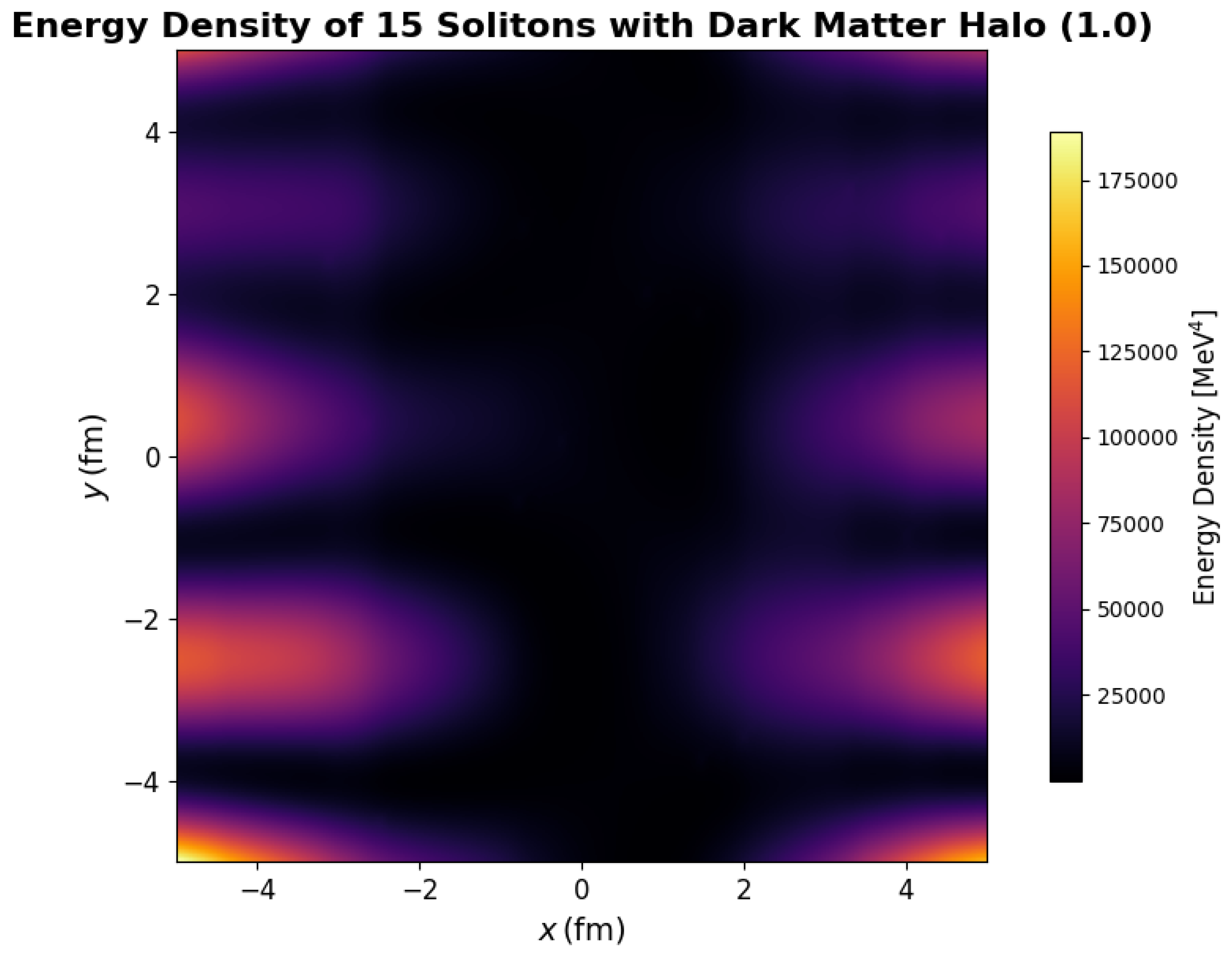

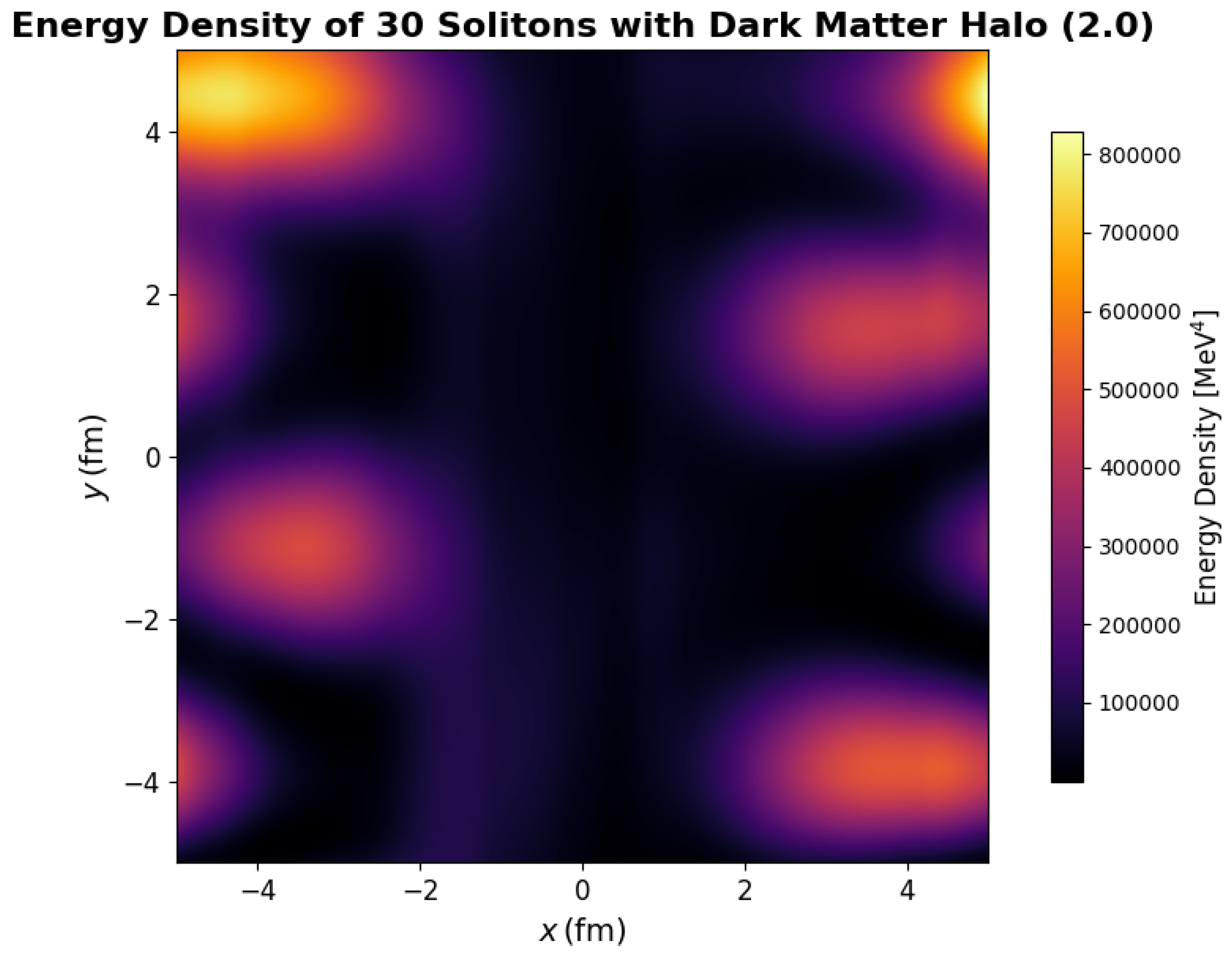

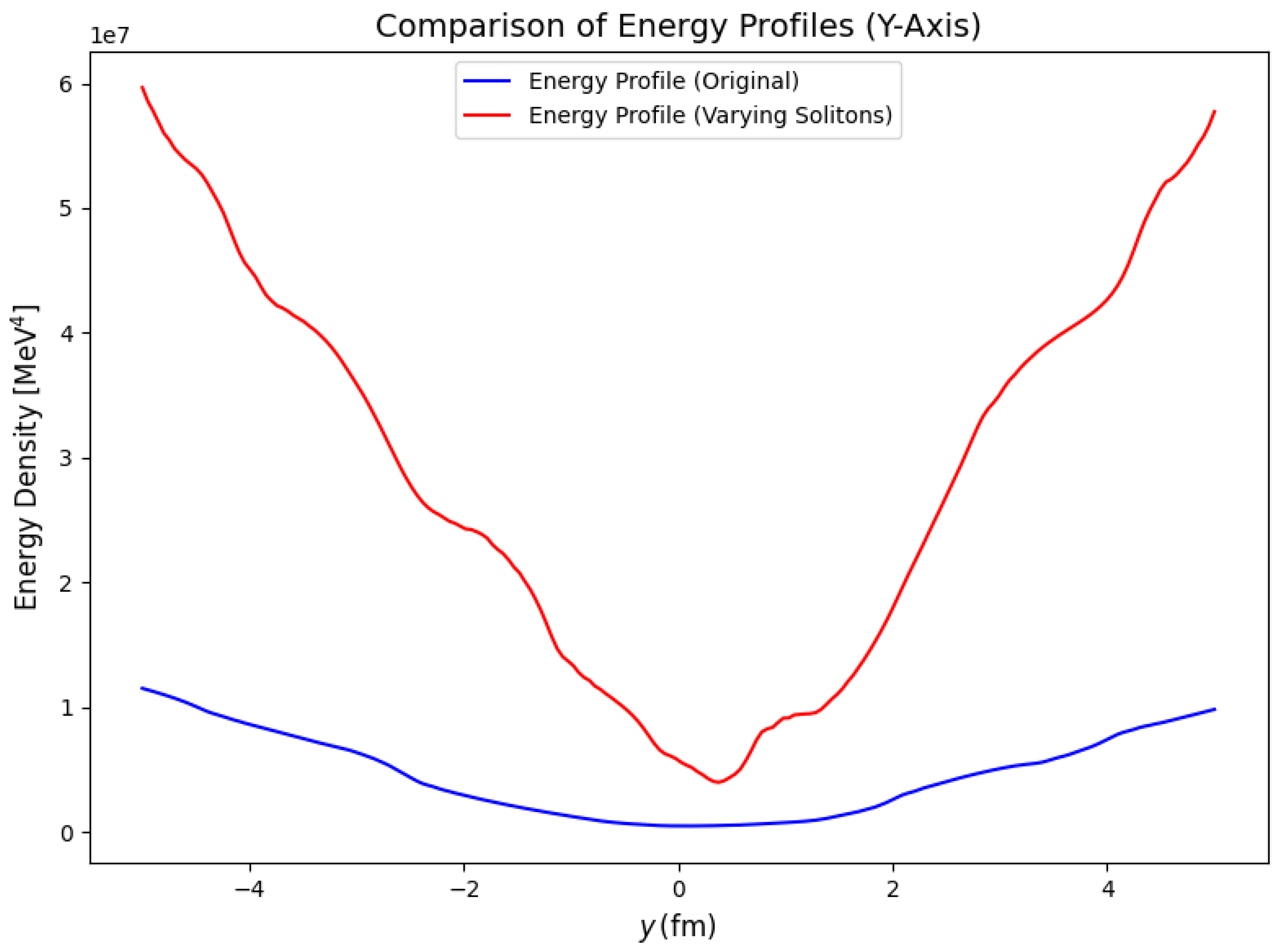

4.1.5. Simulating Skyrme Solitons and Dark Matter Halo Interactions

| Configuration | Total Energy () |

|---|---|

| 15 solitons, | |

| 30 solitons, |

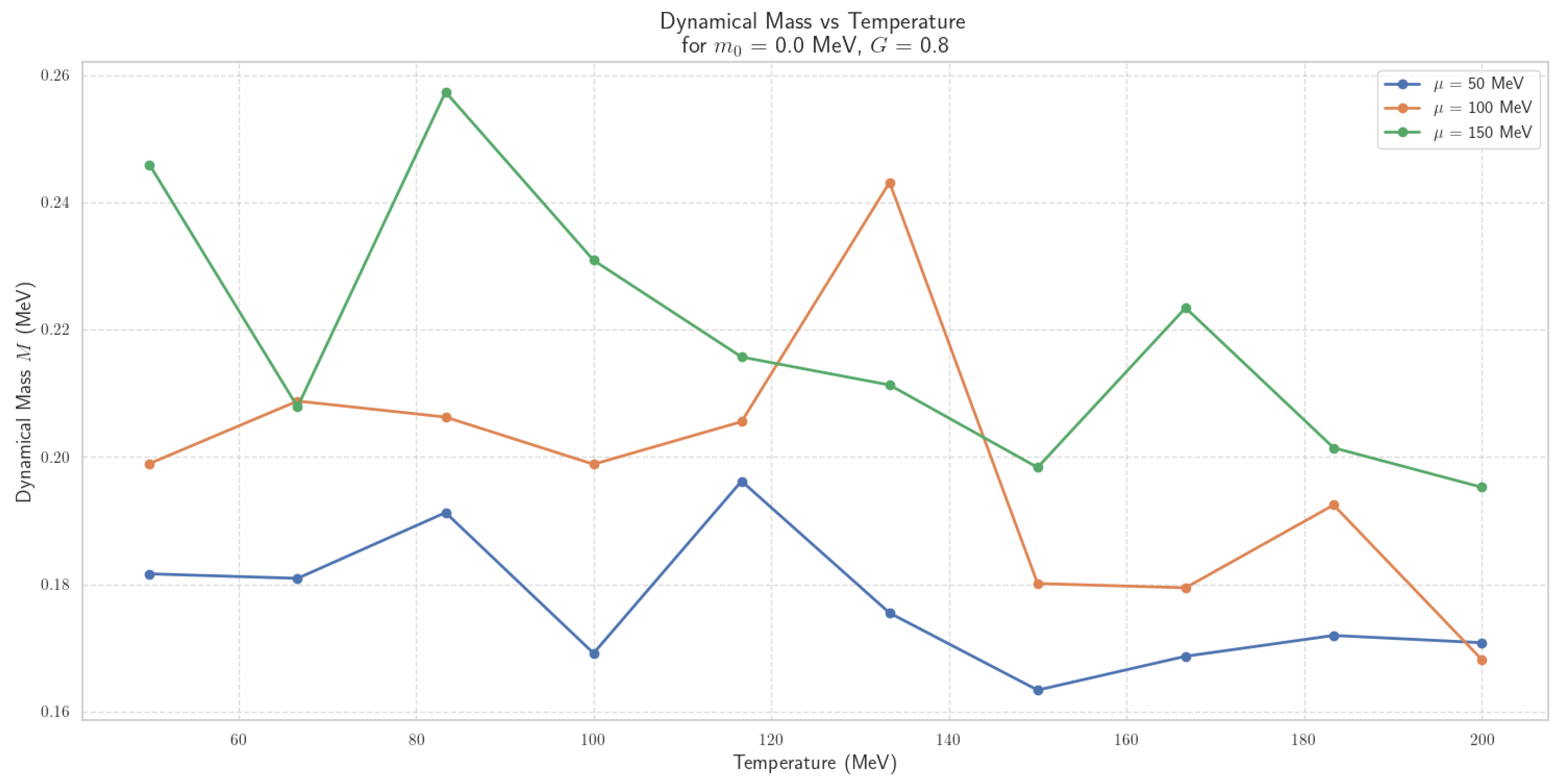

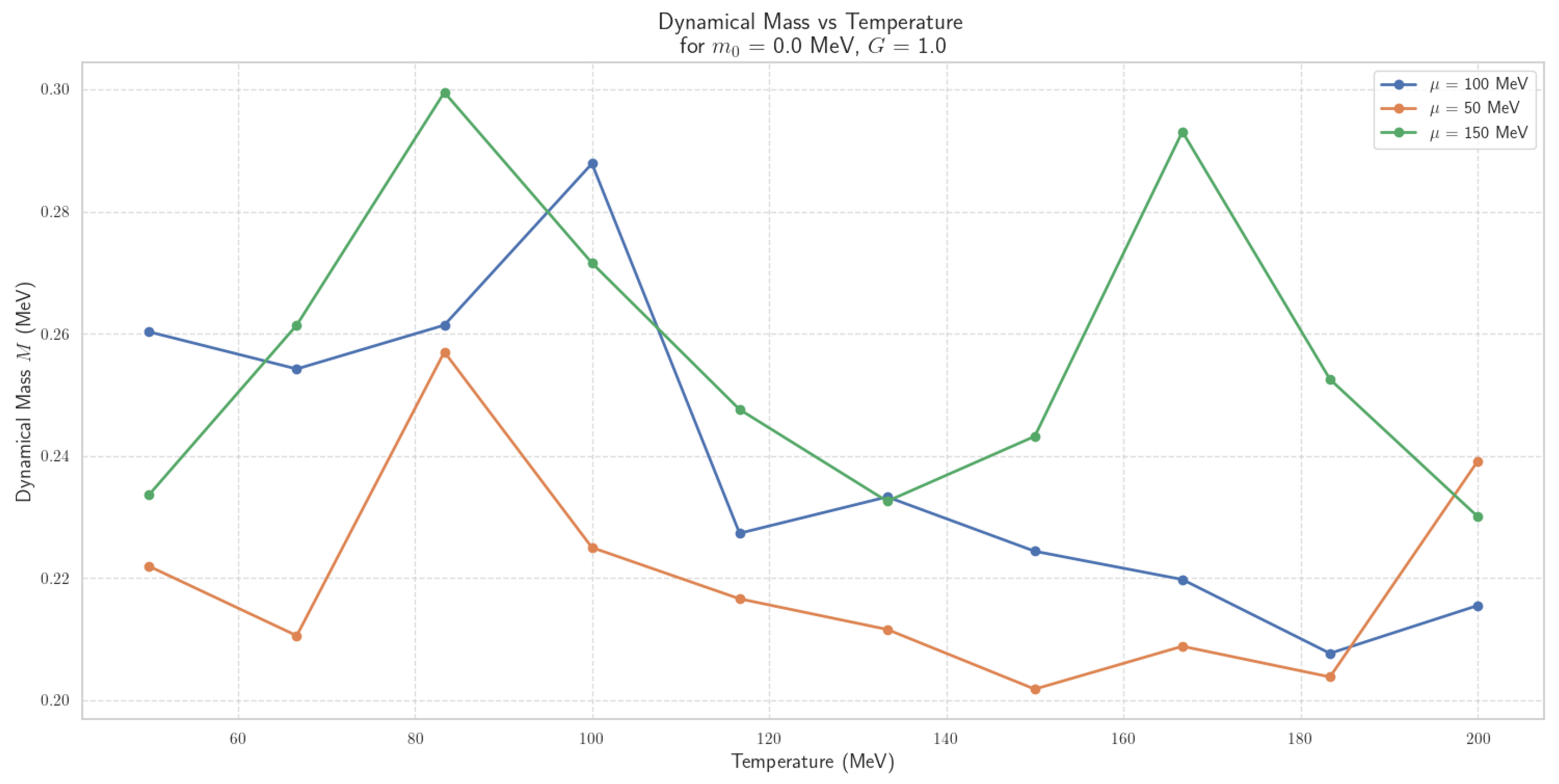

4.2. The Nambu-Jona-Lasinio Model: A Dynamical Framework for Chiral Symmetry Breaking

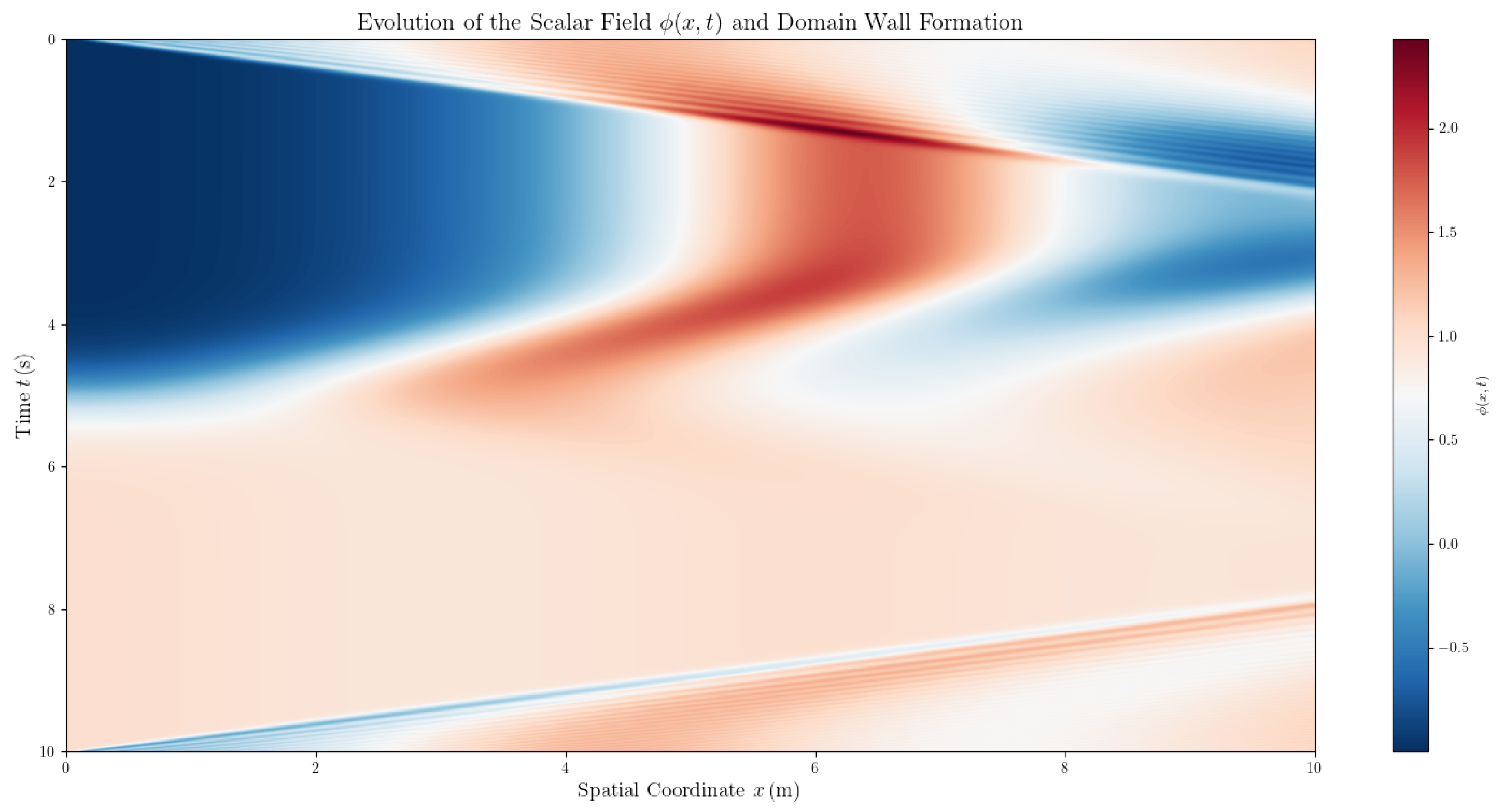

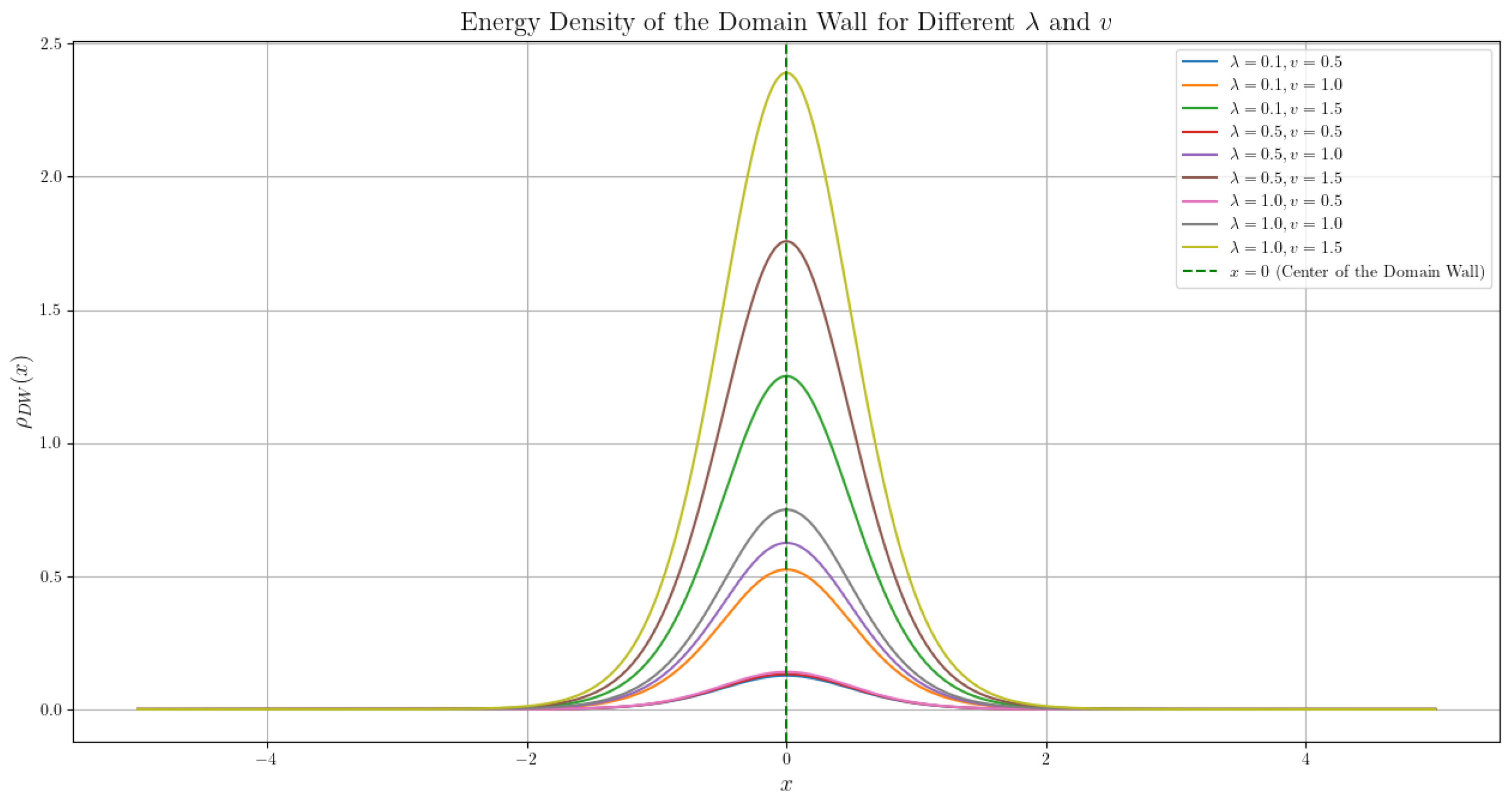

4.2.1. Domain Walls in the Nambu-Jona-Lasinio Model

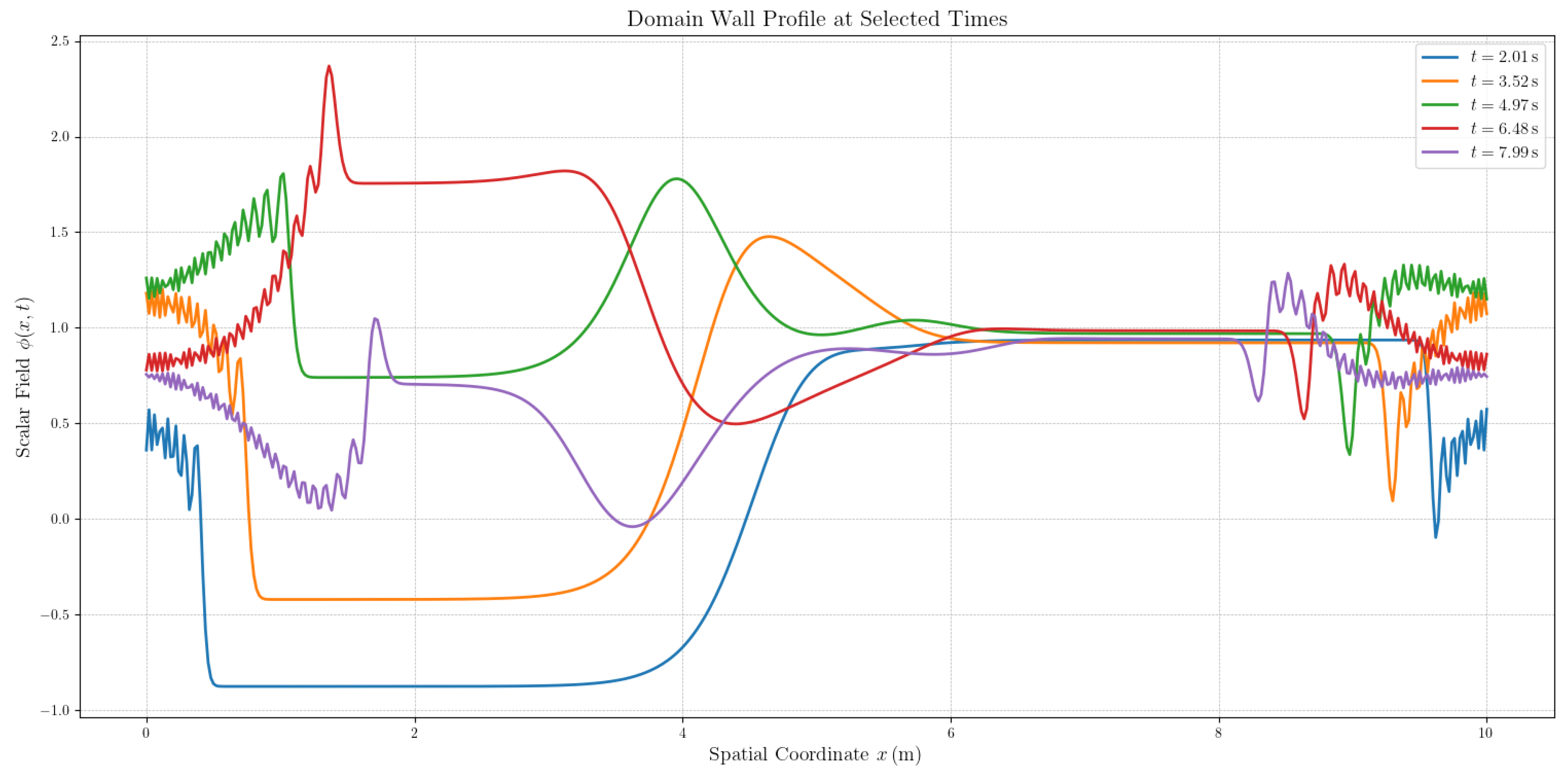

4.2.2. Domain Wall Dynamics in the Nambu-Jona-Lasinio Model

4.2.3. Domain Walls as Dark Matter Candidates

- The suppression of domain wall overproduction must be addressed to avoid conflict with cosmological observations.

- Detailed numerical simulations are needed to assess the stability and longevity of domain wall networks.

- Coupling domain wall dynamics with cosmological parameters could yield predictions for indirect detection via gravitational lensing or cosmic microwave background perturbations [106].

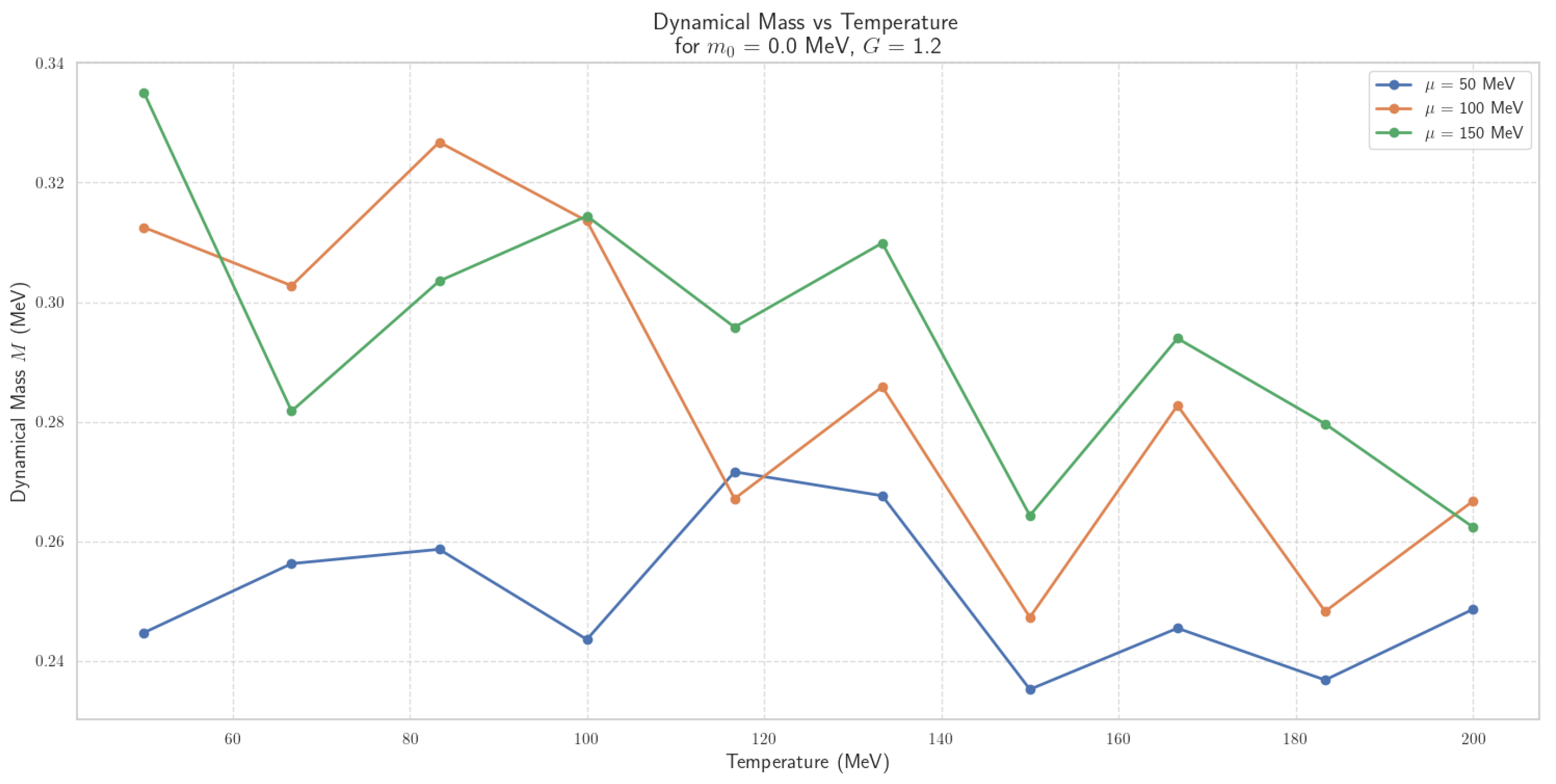

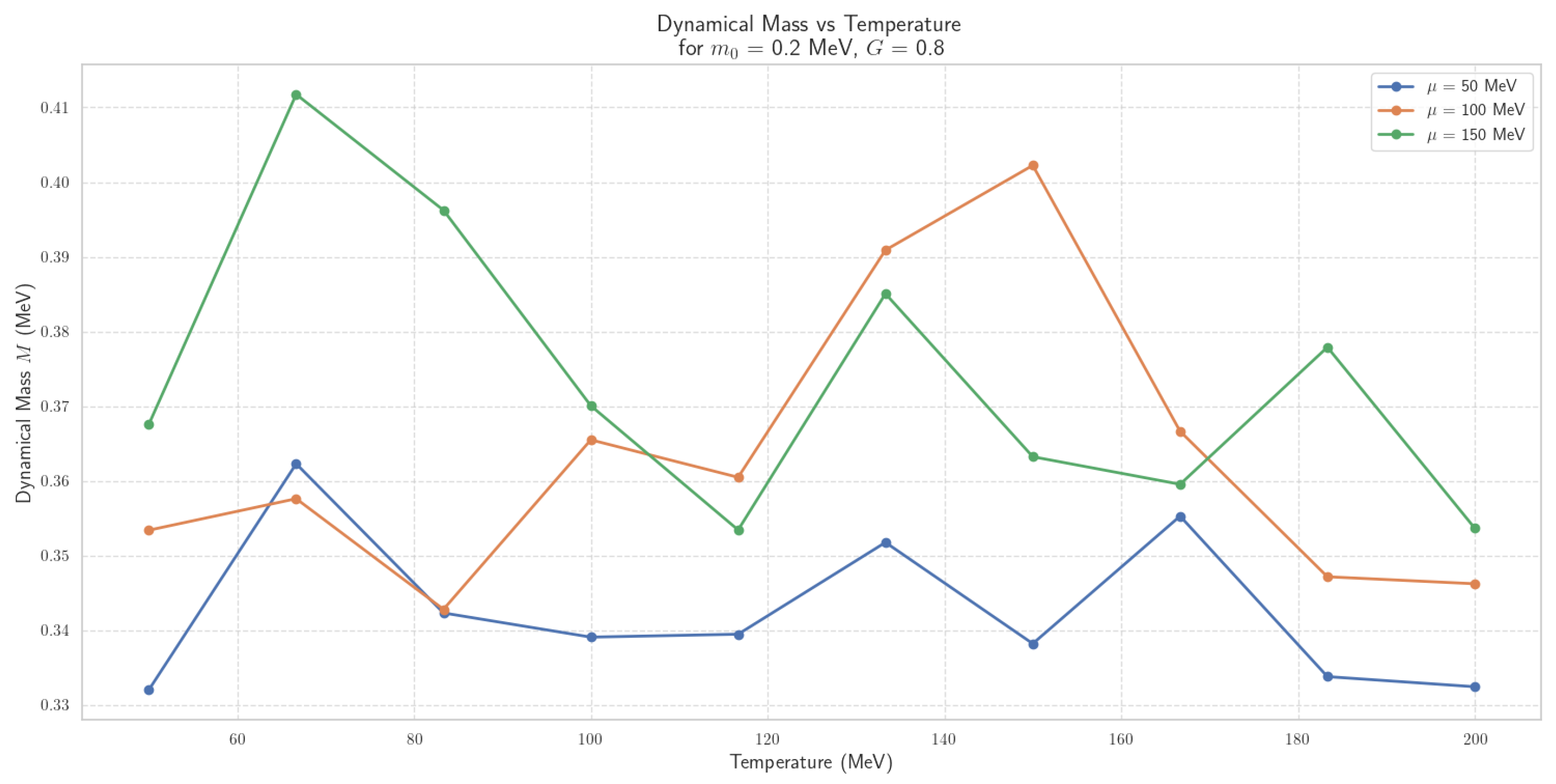

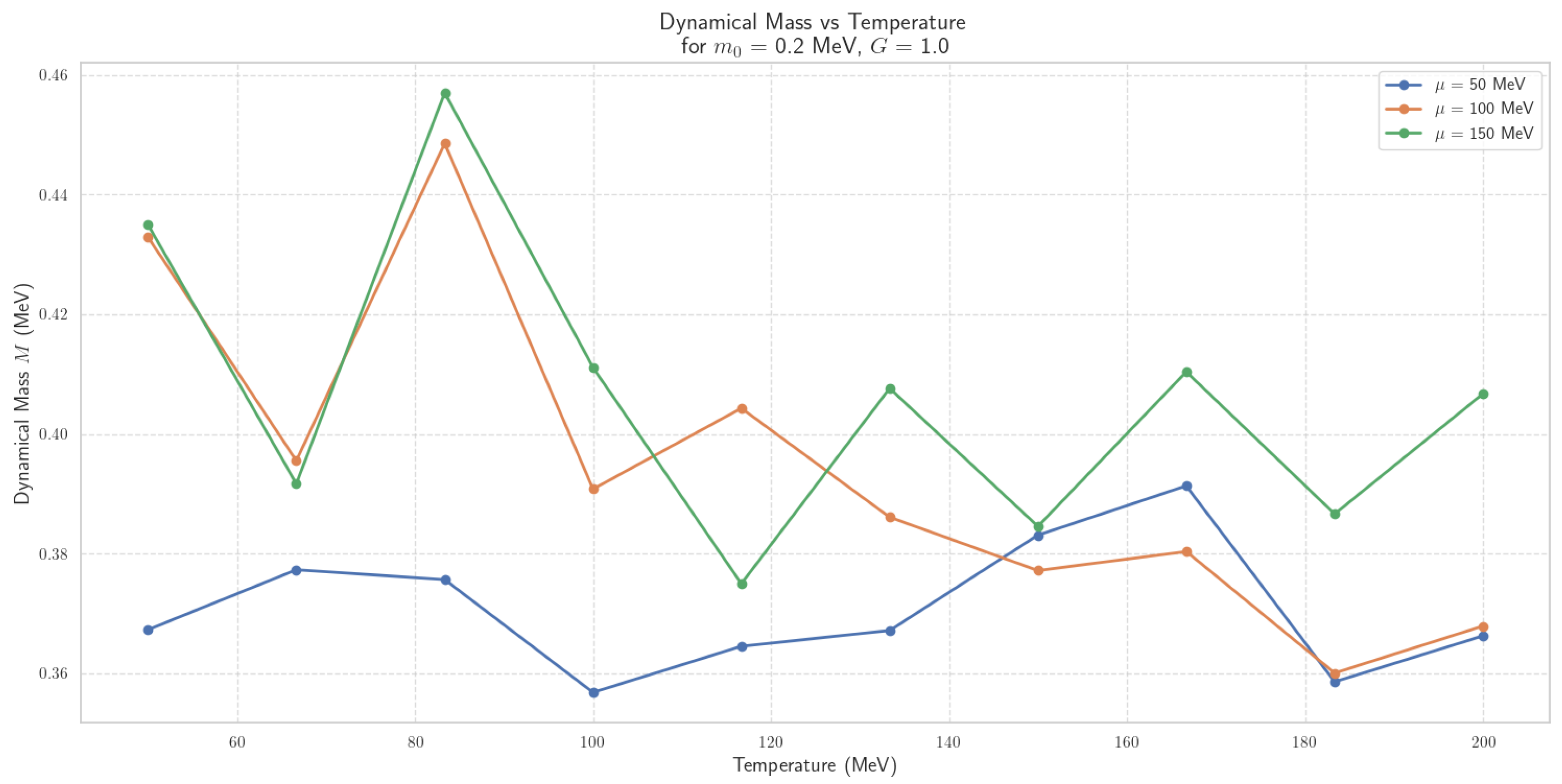

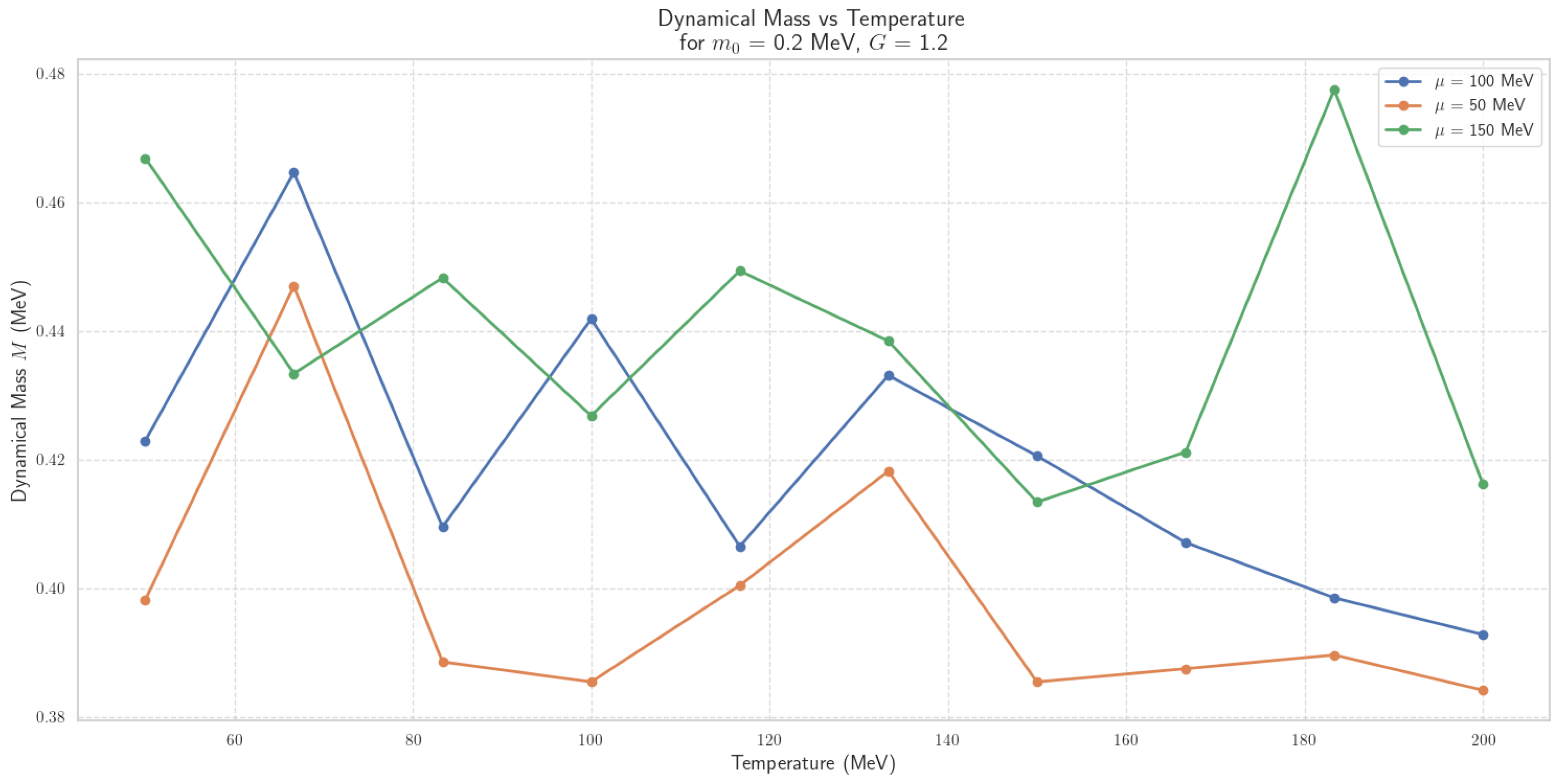

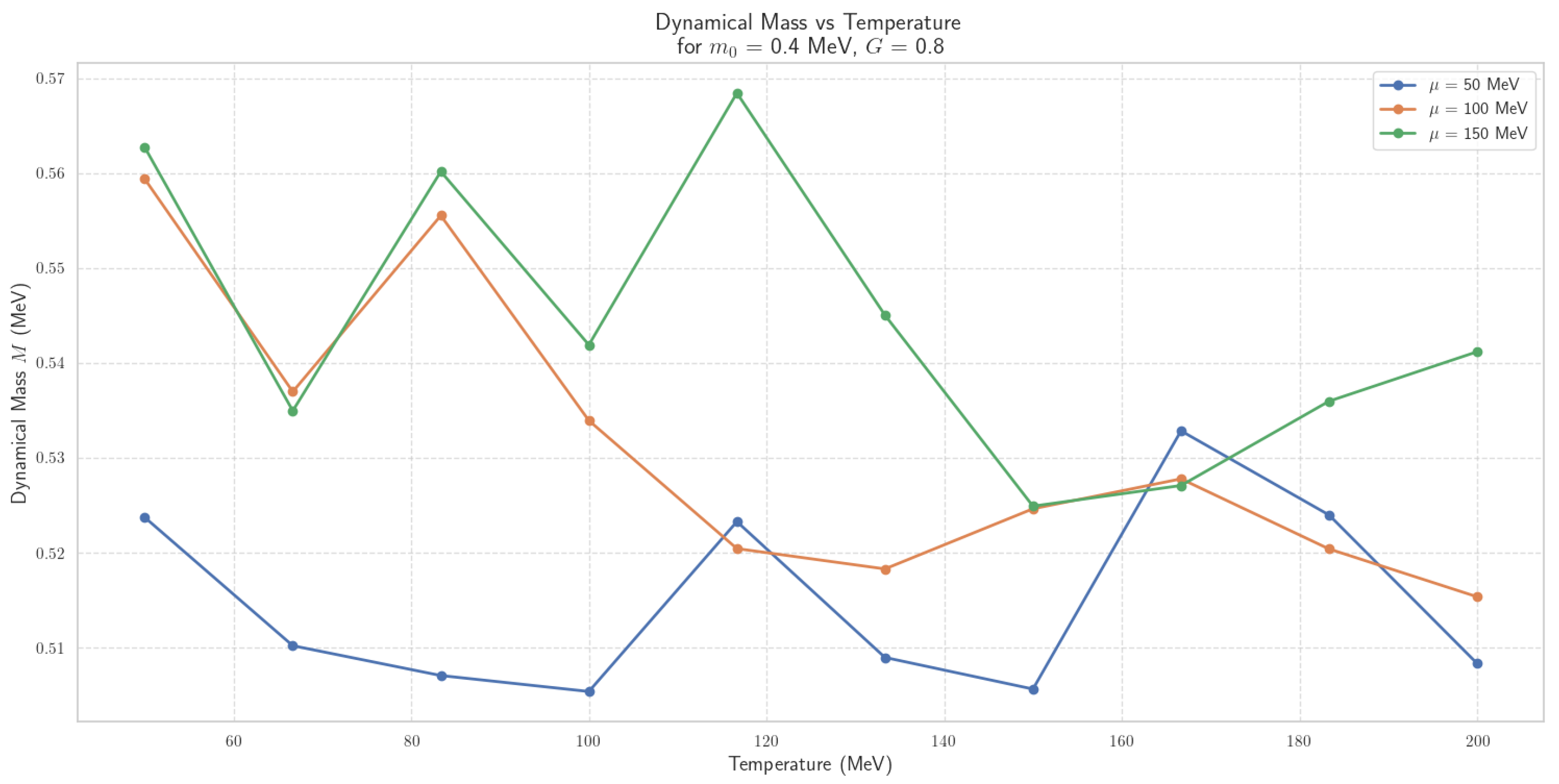

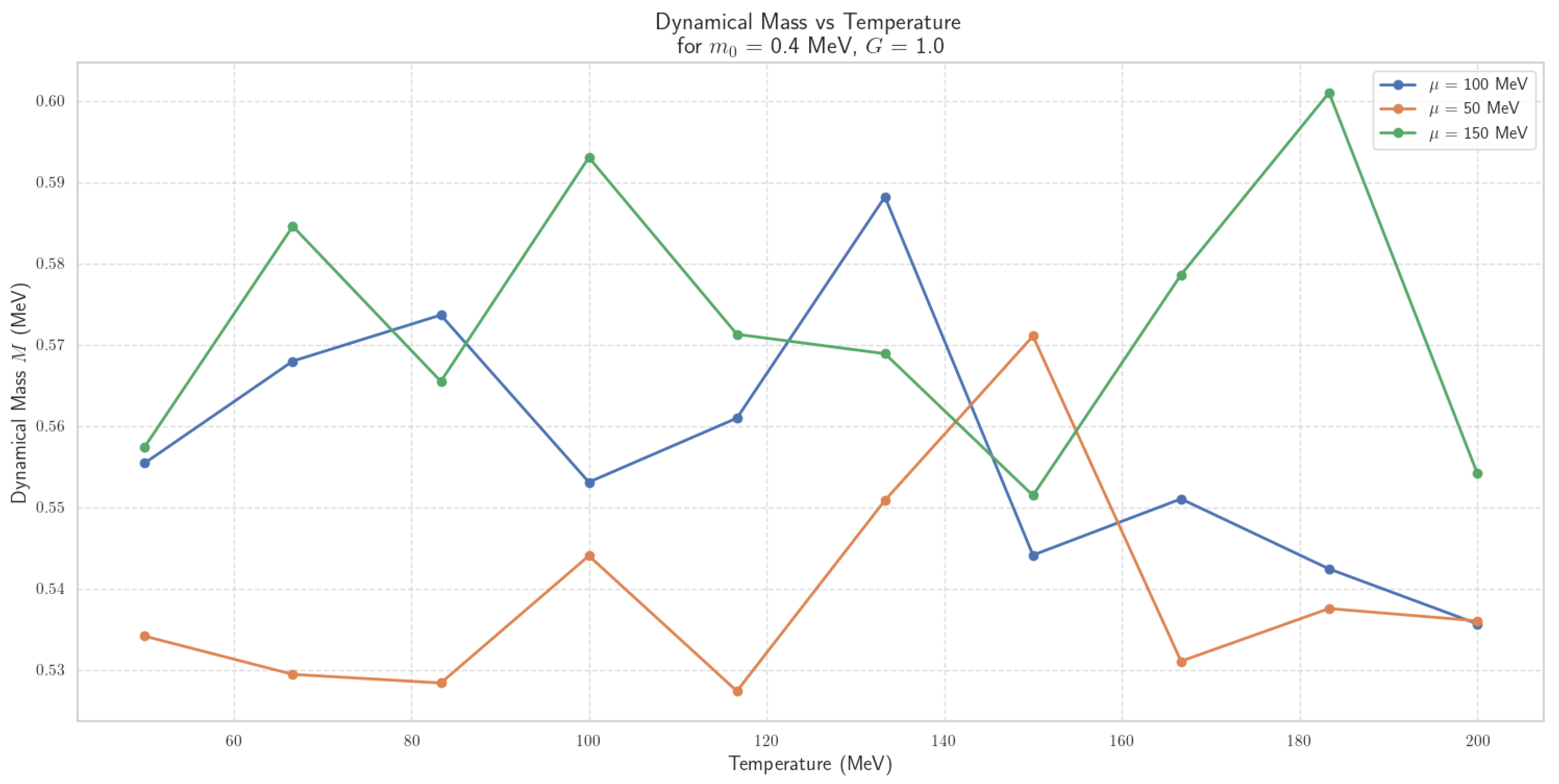

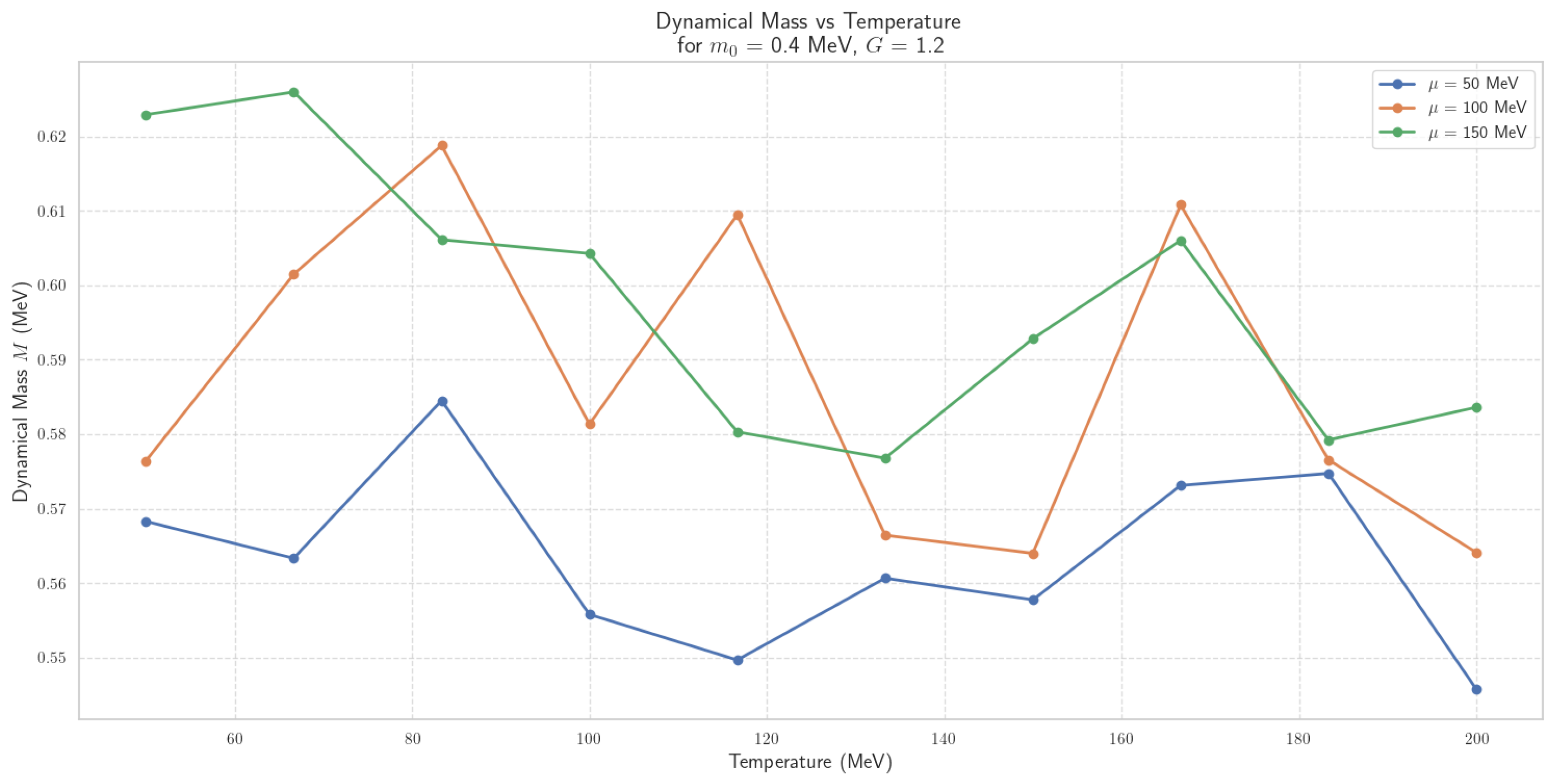

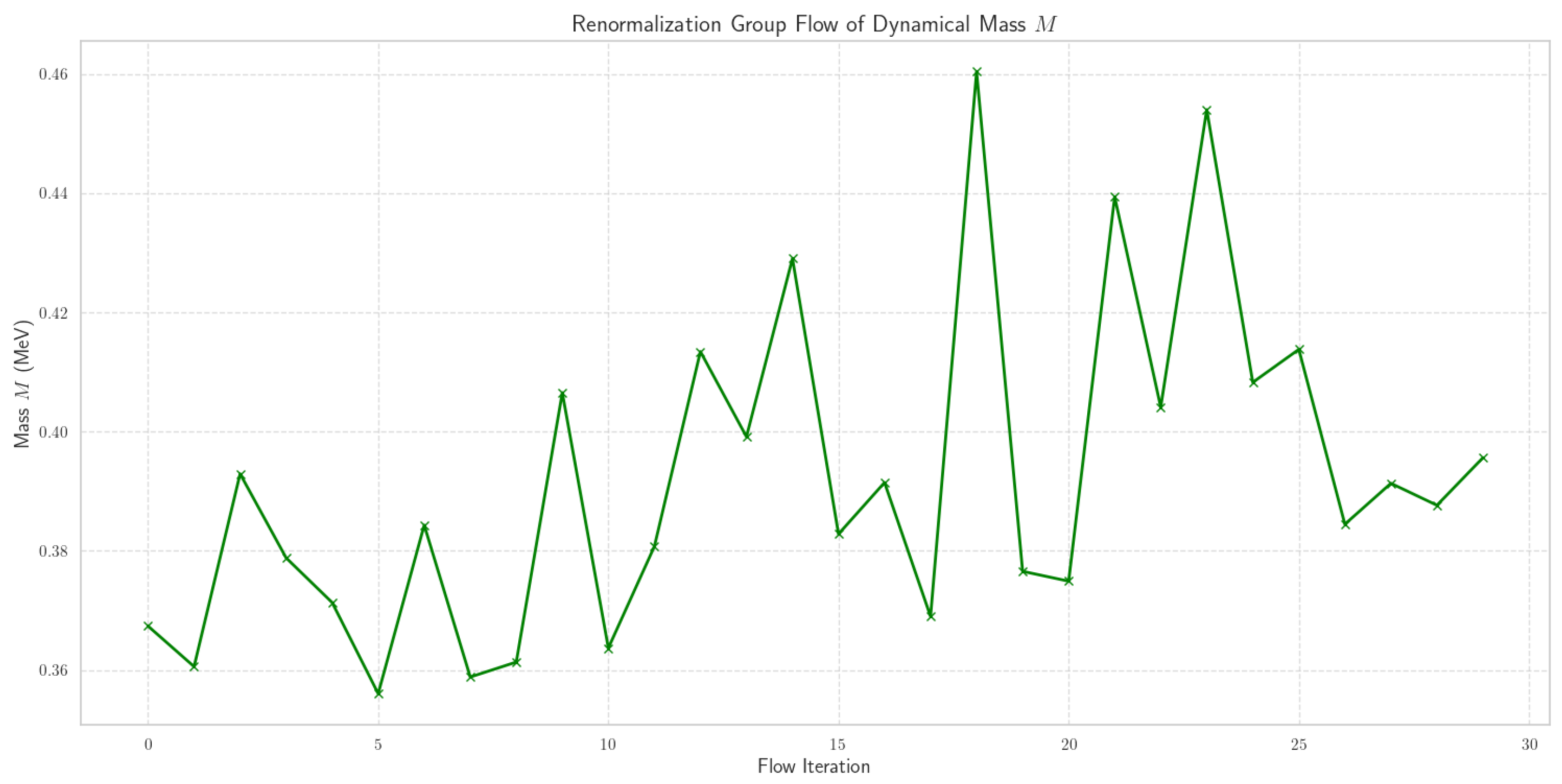

4.2.4. Thermal Dynamics of Scalar Field Mass

4.3. Chiral Perturbation Theory: Low-Energy QCD

4.3.1. Application to the Dark Sector

4.3.2. Dark-Chiral Interactions with the Standard Model

4.3.3. Gravitational Implications and Structure Formation

4.3.4. Higher-Order Chiral Expansions in the Dark Sector

4.3.5. Gravitational Couplings and Cosmological Implications

- Gravitational Lensing: The deflection angle for light passing near a dark matter halo gains corrections proportional to :where the integral is evaluated along the light ray’s trajectory [124].

- Primordial Black Holes: Chiral field dynamics in the early universe can modify the effective equation of state, altering the mass spectrum of primordial black holes. This is described by:where P and are the pressure and energy density [130].

4.3.6. Interdisciplinary Applications of Chiral Perturbation Theory

- Quantum Field Theory in Curved Spacetime: By coupling chiral fields to background spacetime curvature, ChPT provides insights into phenomena such as particle creation in expanding universes and black hole evaporation [131].

- Nonlinear Effective Theories: The formalism is a testbed for studying higher-derivative corrections in other nonlinear theories, including those arising in string theory [134].

5. Conclusion

Acknowledgments

References

- G. Bertone, D. Hooper, and J. Silk, “Particle dark matter: evidence, candidates and constraints,” Physics Reports 405 no. 5–6, (Jan., 2005) 279–390. [CrossRef]

- D. J. Marsh, “Axion cosmology,” Physics Reports 643 (2016) 1–79. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0370157316301557. Axion cosmology.

- A. Kusenko, “Sterile neutrinos: The dark side of the light fermions,” Physics Reports 481 no. 1–2, (Sept., 2009) 1–28. [CrossRef]

- H. Kim, J. Park, and M. Son, “Axion dark matter from cosmic string network,” 2024. [CrossRef]

- E. W. Kolb, The Early Universe, vol. 69. Taylor and Francis, 5, 2019.

- G. Jungman, M. Kamionkowski, and K. Griest, “Supersymmetric dark matter,” Physics Reports 267 no. 5–6, (Mar., 1996) 195–373. [CrossRef]

- P. Gondolo and G. Gelmini, “Cosmic abundances of stable particles: Improved analysis,” Nuclear Physics B 360 no. 1, (1991) 145–179. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/0550321391904384.

- P. Collaboration, Y. Akrami, F. Arroja, M. Ashdown, J. Aumont, C. Baccigalupi, M. Ballardini, A. J. Banday, R. B. Barreiro, N. Bartolo, et al. “Planck 2018 results. ix. constraints on primordial non-gaussianity,” 2019. [CrossRef]

- J. Lewin and P. Smith, “Review of mathematics, numerical factors, and corrections for dark matter experiments based on elastic nuclear recoil,” Astroparticle Physics 6 no. 1, (1996) 87–112. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0927650596000473.

- D. Akerib, C. Akerlof, D. Akimov, A. Alquahtani, S. Alsum, T. Anderson, N. Angelides, H. Araújo, A. Arbuckle, J. Armstrong, et al. “The lux-zeplin (lz) experiment,” Nuclear Instruments and Methods in Physics Research Section A: Accelerators, Spectrometers, Detectors and Associated Equipment 953 (Feb., 2020) 163047. [CrossRef]

- R. Agnese, A. Anderson, T. Aramaki, I. Arnquist, W. Baker, D. Barker, R. Basu Thakur, D. Bauer, A. Borgland, M. Bowles, et al. “Projected sensitivity of the supercdms snolab experiment,” Physical Review D 95 no. 8, (Apr., 2017) . [CrossRef]

- M. Ackermann, A. Albert, B. Anderson, W. Atwood, L. Baldini, G. Barbiellini, D. Bastieri, K. Bechtol, R. Bellazzini, E. Bissaldi, et al. “Searching for dark matter annihilation from milky way dwarf spheroidal galaxies with six years of fermi large area telescope data,” Physical Review Letters 115 no. 23, (Nov., 2015) . [CrossRef]

- L. Bergström, “Dark matter evidence, particle physics candidates and detection methods,” Annalen der Physik 524 no. 9–10, (Aug., 2012) 479–496. [CrossRef]

- E. V. Shuryak, “Quantum Chromodynamics and the Theory of Superdense Matter,” Phys. Rept. 61 (1980) 71–158.

- A. V. NEFEDIEV, Y. A. SIMONOV, and M. A. TRUSOV, “Deconfinement and quark–gluon plasma,” International Journal of Modern Physics E 18 no. 03, (Mar., 2009) 549–599. [CrossRef]

- G. Endrodi, Z. Fodor, S. D. Katz, and K. K. Szabo, “The Equation of state at high temperatures from lattice QCD,” PoS LATTICE2007 (2007) 228, arXiv:0710.4197 [hep-lat].

- P. Shukla and A. K. Mohanty, “Nucleation versus spinodal decomposition in a first order quark hadron phase transition,” Phys. Rev. C 64 (Oct, 2001) 054910. [CrossRef]

- H.-T. Elze and W. Greiner, “Finite size effects for quark-gluon plasma droplets,” Physics Letters B 179 no. 4, (1986) 385–392. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/0370269386904983.

- J. Vredevoogd and S. Pratt, “Viscous hydrodynamics and relativistic heavy ion collisions,” Phys. Rev. C 85 (Apr, 2012) 044908. [CrossRef]

- W.-b. He, G.-y. Shao, X.-y. Gao, X.-r. Yang, and C.-l. Xie, “Speed of sound in qcd matter,” Phys. Rev. D 105 (May, 2022) 094024. [CrossRef]

- M. Panero, “Thermodynamics of the QCD plasma and the large-N limit,” Phys. Rev. Lett. 103 (2009) 232001, arXiv:0907.3719 [hep-lat].

- E. Witten, “Cosmic separation of phases,” Phys. Rev. D 30 (Jul, 1984) 272–285. [CrossRef]

- A. Chodos, R. L. Jaffe, K. Johnson, C. B. Thorn, and V. F. Weisskopf, “New extended model of hadrons,” Phys. Rev. D 9 (Jun, 1974) 3471–3495. [CrossRef]

- L. McLerran and R. D. Pisarski, “Phases of dense quarks at large,” Nuclear Physics A 796 no. 1–4, (Nov., 2007) 83–100. [CrossRef]

- E. Iancu, A. Leonidov, and L. McLerran, “The Color glass condensate: An Introduction,” in Cargese Summer School on QCD Perspectives on Hot and Dense Matter, pp. 73–145. 2, 2002. arXiv:hep-ph/0202270.

- J. P. VanDevender, I. M. Shoemaker, T. Sloan, A. P. VanDevender, and B. A. Ulmen, “Mass distribution of magnetized quark-nugget dark matter and comparison with requirements and observations,” Scientific Reports 10 no. 1, (Oct., 2020) . [CrossRef]

- P. S. Koliogiannis, G. A. Tsalis, C. P. Panos, and C. C. Moustakidis, “Configurational entropy as a probe of the stability condition of compact objects,” Phys. Rev. D 107 (Feb, 2023) 044069. [CrossRef]

- G. Cohen-Tanoudji and J.-P. Gazeau, “Dark matter as a QCD effect in an anti de Sitter geometry: Cosmogonic implications of de Sitter, anti de Sitter and Poincaré symmetries,” SciPost Phys. Proc. 14 (2023) 004.

- K. Fukushima and T. Hatsuda, “The phase diagram of dense qcd,” Reports on Progress in Physics 74 no. 1, (Dec., 2010) 014001. [CrossRef]

- P. Sikivie and Q. Yang, “Bose-Einstein Condensation of Dark Matter Axions,” Phys. Rev. Lett. 103 (2009) 111301, arXiv:0901.1106 [hep-ph]. arXiv:0901.1106 [hep-ph].

- T. Harko, “Evolution of cosmological perturbations in bose-einstein condensate dark matter: Cosmological perturbations in bec,” Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 413 no. 4, (Mar., 2011) 3095–3104. [CrossRef]

- G. Cohen-Tannoudji, “Dark matter explained in terms of a gluonic bose-einstein condensate in an anti-de sitter geometry,” HAL Archive (2024) . https://hal.science/hal-04481807.

- S. Solanki, M. Lal, R. Sharma, and V. K. Agotiya, “Dissociation and thermodynamical properties of heavy quarkonia in an anisotropic strongly coupled hot quark gluon plasma: Using a baryonic chemical potential,” Phys. Rev. C 109 (Feb, 2024) 024905. [CrossRef]

- F. Karsch, “Lattice qcd at high temperature and density,” 2001. [CrossRef]

- S. K. Singh, “Confinement phenomena in topological stars,” 2024. [CrossRef]

- L. McLerran, “The physics of the quark-gluon plasma,” Reviews of Modern Physics 58 no. 4, (1986) 1021.

- J. Adams, M. Aggarwal, Z. Ahammed, J. Amonett, B. Anderson, D. Arkhipkin, G. Averichev, S. Badyal, Y. Bai, J. Balewski, et al. “Experimental and theoretical challenges in the search for the quark–gluon plasma: The star collaboration’s critical assessment of the evidence from rhic collisions,” Nuclear Physics A 757 no. 1–2, (Aug., 2005) 102–183. [CrossRef]

- D. Boyanovsky, H. de Vega, and D. Schwarz, “Phase transitions in the early and present universe,” Annual Review of Nuclear and Particle Science 56 no. 1, (Nov., 2006) 441–500. [CrossRef]

- S. Singh, “Black hole microstates and entropy,” Preprints (October, 2024) . [CrossRef]

- G. Boyd, J. Engels, F. Karsch, E. Laermann, C. Legeland, M. Lütgemeier, and B. Petersson, “Thermodynamics of su(3) lattice gauge theory,” Nuclear Physics B 469 no. 3, (June, 1996) 419–444. [CrossRef]

- A. Bazavov, T. Bhattacharya, C. DeTar, H.-T. Ding, S. Gottlieb, R. Gupta, P. Hegde, U. Heller, F. Karsch, E. Laermann, et al. “Equation of state in (2+1)-flavor qcd,” Physical Review D 90 no. 9, (Nov., 2014) . [CrossRef]

- R. D. Pisarski and F. Wilczek, “Remarks on the chiral phase transition in chromodynamics,” Physical Review D 29 no. 2, (1984) 338–341.

- C. Ratti, M. A. Thaler, and W. Weise, “Phases of qcd: Lattice thermodynamics and a field theoretical model,” Physical Review D 73 no. 1, (2006) 014019.

- H.-T. Ding, F. Karsch, and S. Mukherjee, “Thermodynamics of strong-interaction matter from lattice qcd,” 2015. [CrossRef]

- Y. A. et al., “The order of the quantum chromodynamics transition predicted by the standard model of particle physics,” Nature 443 no. 7112, (2006) 675–678.

- S. Gupta, “Qcd at finite density,” 2010. [CrossRef]

- P. Kovtun, D. T. Son, and A. O. Starinets, “Viscosity in strongly interacting quantum field theories from black hole physics,” Physical Review Letters 94 (2005) 111601.

- M. Gyulassy and X.-N. Wang, “Multiple collisions and induced gluon bremsstrahlung in qcd,” Nuclear Physics B 420 no. 3, (1994) 583–614.

- P. Braun-Munzinger and J. Stachel, “The quest for the quark-gluon plasma,” Nature 448 (2007) 302–309.

- D. Teaney, J. Lauret, and E. V. Shuryak, “Flow at the sps and rhic as a quark-gluon plasma signature,” Physical Review Letters 86 no. 21, (May, 2001) 4783–4786. [CrossRef]

- C. GALE, S. JEON, and B. SCHENKE, “Hydrodynamic modeling of heavy-ion collisions,” International Journal of Modern Physics A 28 no. 11, (Apr., 2013) 1340011. [CrossRef]

- H. Pleiner and M. C. R. Comm, “29] ld landau and em lifshitz, fluid mechanics, (pergamon press, new york, 1959), ch. xvii.”.

- R. Baier, P. Romatschke, D. T. Son, A. O. Starinets, and M. A. Stephanov, “Relativistic viscous hydrodynamics, conformal invariance, and holography,” Journal of High Energy Physics 2008 no. 04, (Apr., 2008) 100–100. [CrossRef]

- J.-Y. Ollitrault, “Anisotropy as a signature of transverse collective flow,” Physical Review D 46 no. 1, (1992) 229–245.

- U. Heinz and R. Snellings, “Collective flow and viscosity in relativistic heavy-ion collisions,” Annual Review of Nuclear and Particle Science 63 no. 1, (Oct., 2013) 123–151. [CrossRef]

- R. Baier, Y. L. Dokshitzer, A. H. Mueller, S. Peigné, and D. Schiff, “Radiative energy loss of high energy quarks and gluons in a finite-volume quark-gluon plasma,” Nuclear Physics B 483 no. 1-2, (1997) 291–320.

- R. Baier, Y. L. Dokshitzer, A. H. Mueller, and D. Schiff, “Quenching of hadron spectra in media,” Journal of High Energy Physics 2001 no. 09, (2001) 033.

- K. Yagi, T. Hatsuda, and Y. Miake, Quark-Gluon Plasma: From Big Bang to Little Bang. Cambridge University Press, 2005.

- Y. Aoki, S. Borsányi, S. Dürr, Z. Fodor, S. D. Katz, S. Krieg, and K. Szabo, “The qcd transition temperature: results with physical masses in the continuum limit ii,” Journal of High Energy Physics 2009 no. 06, (June, 2009) 088–088. [CrossRef]

- B.-J. Schaefer, M. Wagner, and J. Wambach, “Qcd thermodynamics with effective models,” 2009. [CrossRef]

- S. Weinberg, Cosmology. Oxford University Press, 2008.

- T. W. B. Kibble, “Topology of cosmic domains and strings,” Journal of Physics A: Mathematical and General 9 no. 8, (1976) 1387–1398.

- A. Vilenkin and E. P. S. Shellard, Cosmic Strings and Other Topological Defects. Cambridge University Press, 7, 2000.

- C. Han, “Qcd axion dark matter and the cosmic dipole problem,” Phys. Rev. D 108 (Jul, 2023) 015026. [CrossRef]

- A. Y. Kotov, M. P. Lombardo, and A. M. Trunin, “Fate of the η′ in the quark gluon plasma,” Physics Letters B 794 (Jul, 2019) 83–88. [CrossRef]

- D. J. Gross and F. Wilczek, “Asymptotically free gauge theories. 1.” Physical Review D 8 no. 10, (1973) 3633–3652.

- H. D. Politzer, “Reliable Perturbative Results for Strong Interactions?,” Phys. Rev. Lett. 30 (1973) 1346–1349.

- K. G. Wilson, “Confinement of quarks,” Phys. Rev. D 10 (Oct, 1974) 2445–2459. [CrossRef]

- G. S. Bali, “Qcd forces and heavy quark bound states,” Physics Reports 343 no. 1–2, (Mar., 2001) 1–136. [CrossRef]

- T. Skyrme, “A unified field theory of mesons and baryons,” Nuclear Physics 31 (1962) 556–569. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/0029558262907757.

- E. Witten, “Current algebra, baryons, and quark confinement,” Nuclear Physics B 223 no. 2, (1983) 433–444. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/0550321383900640.

- T. Sakai and S. Sugimoto, “Low energy hadron physics in holographic qcd,” Progress of Theoretical Physics 113 no. 4, (Apr., 2005) 843–882. [CrossRef]

- J. C. Biddle, Centre Vortices in Lattice QCD: Visualisations and Impact on the Gluon Propagator. PhD thesis, Adelaide U., 2019.

- R. D. Peccei and H. R. Quinn, “CP Conservation in the Presence of Instantons,” Phys. Rev. Lett. 38 (1977) 1440–1443.

- S. Weinberg, Quantum Theory of Fields, Volume 2: Modern Applications. Cambridge University Press, 1996.

- M. Shifman, A. Vainshtein, and V. Zakharov, “Qcd and resonance physics. applications,” Nuclear Physics B 147 no. 5, (1979) 448–518. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/0550321379900233.

- Y. Bai, S. Lu, and N. Orlofsky, “Origin of nontopological soliton dark matter: solitosynthesis or phase transition,” Journal of High Energy Physics 2022 no. 10, (Oct., 2022) . [CrossRef]

- Y. Nambu and G. Jona-Lasinio, “Dynamical model of elementary particles based on an analogy with superconductivity. i,” Phys. Rev. 122 (Apr, 1961) 345–358. [CrossRef]

- Y. Nambu and G. Jona-Lasinio, “Dynamical model of elementary particles based on an analogy with superconductivity. ii,” Phys. Rev. 124 (Oct, 1961) 246–254. [CrossRef]

- K. Fukushima, “Qcd matter in extreme environments,” Journal of Physics G: Nuclear and Particle Physics 39 no. 1, (Nov, 2011) 013101. [CrossRef]

- J. Gasser and H. Leutwyler, “Chiral perturbation theory to one loop,” Annals of Physics 158 no. 1, (1984) 142–210. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/0003491684902422.

- B. Ananthanarayan, M. S. A. A. Khan, and D. Wyler, “Chiral perturbation theory: reflections on effective theories of the standard model,” Indian Journal of Physics 97 no. 11, (Feb., 2023) 3245–3267. [CrossRef]

- T. H. R. Skyrme and B. F. J. Schonland, “A non-linear field theory,” Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series A. Mathematical and Physical Sciences 260 no. 1300, (1961) 127–138. [CrossRef]

- M. Nitta, “Relations among topological solitons,” Phys. Rev. D 105 (May, 2022) 105006. [CrossRef]

- N. Manton and P. Sutcliffe, Topological Solitons. Cambridge Monographs on Mathematical Physics. Cambridge University Press, 2004.

- G. S. Adkins, C. R. Nappi, and E. Witten, “Static properties of nucleons in the skyrme model,” Nuclear Physics B 228 no. 3, (1983) 552–566. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/055032138390559X.

- I. Zahed and G. E. Brown, “The Skyrme Model,” Phys. Rept. 142 (1986) 1–102.

- C. Adam, C. Naya, J. Sanchez-Guillen, R. Vazquez, and A. Wereszczynski, “Bps skyrmions as neutron stars,” Physics Letters B 742 (2015) 136–142. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0370269315000374.

- Y. Brihaye, C. Herdeiro, E. Radu, and D. Tchrakian, “Skyrmions, skyrme stars and black holes with skyrme hair in five spacetime dimension,” Journal of High Energy Physics 2017 no. 11, (Nov., 2017) . [CrossRef]

- B. Göbel, I. Mertig, and O. A. Tretiakov, “Beyond skyrmions: Review and perspectives of alternative magnetic quasiparticles,” Physics Reports 895 (2021) 1–28. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0370157320303525. Beyond skyrmions: Review and perspectives of alternative magnetic quasiparticles.

- J. P. Garrahan, M. Schvellinger, and N. N. Scoccola, “Multibaryons as symmetric multi-skyrmions,” Phys. Rev. D 61 (Nov, 1999) 014001. [CrossRef]

- E. Kiritsis, “Dissecting the string theory dual to qcd,” Fortschritte der Physik 57 no. 5–7, (May, 2009) 396–417. [CrossRef]

- S. B. Popov and M. Prokhorov, “Formation of massive skyrmion stars,” Astronomy & Astrophysics 434 no. 2, (2005) 649–655.

- J. C. Criado, A. Djouadi, M. Pérez-Victoria, and J. Santiago, “A complete effective field theory for dark matter,” Journal of High Energy Physics 2021 no. 7, (July, 2021) . [CrossRef]

- J. F. Navarro, C. S. Frenk, and S. D. M. White, “The structure of cold dark matter halos,” The Astrophysical Journal 462 (May, 1996) 563. [CrossRef]

- F. Canfora and H. Maeda, “Hedgehog ansatz and its generalization for self-gravitating skyrmions,” Physical Review D 87 no. 8, (Apr., 2013) . [CrossRef]

- Y. Manita, T. Takahashi, and A. Taruya, “Soliton self-gravity and core-halo relation in fuzzy dark matter halos,” 2024. [CrossRef]

- M. V. Flamarion and E. Pelinovsky, “Interactions of solitons with an external force field: Exploring the schamel equation framework,” Chaos, Solitons & Fractals 174 (2023) 113799. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0960077923007002.

- P. Channuie and C. Xiong, “Unified composite scenario for inflation and dark matter in the nambu–jona-lasinio model,” Physical Review D 95 no. 4, (Feb., 2017) . [CrossRef]

- T. Hatsuda and T. Kunihiro, “Qcd phenomenology based on a chiral effective lagrangian,” Physics Reports 247 no. 5–6, (Oct., 1994) 221–367. [CrossRef]

- S. P. Klevansky, “The Nambu-Jona-Lasinio model of quantum chromodynamics,” Rev. Mod. Phys. 64 (1992) 649–708.

- S. Kutnii, “Domain wall in nambu-jona-lasinio model,” 2011. [CrossRef]

- R. Jackiw and C. Rebbi, “Solitons with Fermion Number 1/2,” Phys. Rev. D 13 (1976) 3398–3409.

- Y. B. Zeldovich, I. Y. Kobzarev, and L. B. Okun, “Cosmological Consequences of the Spontaneous Breakdown of Discrete Symmetry,” Zh. Eksp. Teor. Fiz. 67 (1974) 3–11.

- T. W. B. Kibble, “Some implications of a cosmological phase transition,” Physics Reports 67 no. 1, (1980) 183–199.

- A. Vilenkin, “Gravitational field of vacuum domain walls and strings,” Physical Review D 23 no. 4, (1981) 852–857.

- E. Elizalde, Quantum Field Theory: A Modern Perspective. Springer-Verlag, Berlin, Heidelberg, 1994.

- N. Tamanini, “Dynamics of cosmological scalar fields,” Physical Review D 89 no. 8, (Apr., 2014) . [CrossRef]

- R. Ballesteros, C. Gómez-Fayrén, T. Ortín, and M. Zatti, “On scalar charges and black hole thermodynamics,” Journal of High Energy Physics 2023 no. 5, (May, 2023) . [CrossRef]

- T. P. Sotiriou, “Black holes and scalar fields,” Classical and Quantum Gravity 32 no. 21, (Oct., 2015) 214002. [CrossRef]

- N. D. Birrell and P. C. W. Davies, Quantum Fields in Curved Space. Cambridge Monographs on Mathematical Physics. Cambridge University Press, 1982.

- W. G. Unruh, “Experimental black-hole evaporation?” Phys. Rev. Lett. 46 (May, 1981) 1351–1353. [CrossRef]

- S. Weinberg, “Phenomenological lagrangians,” Physica A: Statistical Mechanics and its Applications 96 no. 1, (1979) 327–340. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/0378437179902231.

- H. Leutwyler, Foundations and scope of chiral perturbation theory, p. 14–29. Springer Berlin Heidelberg. [CrossRef]

- S. Scherer, “Introduction to chiral perturbation theory,” 2002. [CrossRef]

- V. BERNARD, “Chiral perturbation theory and baryon properties,” Progress in Particle and Nuclear Physics 60 no. 1, (Jan., 2008) 82–160. [CrossRef]

- J. F. Donoghue, E. Golowich, and B. R. Holstein, Dynamics of the Standard Model. Cambridge Monographs on Particle Physics, Nuclear Physics and Cosmology. Cambridge University Press, 2 ed., 2023.

- G. Colangelo, J. Gasser, and H. Leutwyler, “The quark condensate from k(e(4)) decays,” Physical Review Letters 86 no. 22, (May, 2001) 5008–5010. [CrossRef]

- G. D. Kribs and E. T. Neil, “Review of strongly-coupled composite dark matter models and lattice simulations,” Int. J. Mod. Phys. A 31 no. 22, (2016) 1643004, arXiv:1604.04627 [hep-ph].

- R. Garani, M. Redi, and A. Tesi, “Dark qcd matters,” Journal of High Energy Physics 2021 no. 12, (Dec., 2021) . [CrossRef]

- F. Chen, J. M. Cline, and A. R. Frey, “Non-abelian dark matter: Models and constraints,” Physical Review D 80 no. 8, (Oct., 2009) . [CrossRef]

- H. Baer, K.-Y. Choi, J. E. Kim, and L. Roszkowski, “Dark matter production in the early universe: Beyond the thermal wimp paradigm,” Physics Reports 555 (Feb., 2015) 1–60. [CrossRef]

- W. Hu and N. Sugiyama, “Small-scale cosmological perturbations: An analytic approach,” The Astrophysical Journal 471 no. 2, (Nov., 1996) 542–570. [CrossRef]

- A. Loeb, The First Galaxies in the Universe. Princeton University Press, 2014.

- P. G. Ferreira, “Cosmological tests of gravity,” Annual Review of Astronomy and Astrophysics 57 no. Volume 57, 2019, (2019) 335–374. https://www.annualreviews.org/content/journals/10.1146/annurev-astro-091918-104423.

- J. Bijnens, G. Colangelo, and G. Ecker, “The mesonic chiral lagrangian of order p6,” Journal of High Energy Physics 1999 no. 02, (1999) 020.

- S.-Z. Jiang, Y. Zhang, C. Li, and Q. Wang, “Computation of the p6 order chiral Lagrangian coefficients,” Phys. Rev. D 81 (2010) 014001, arXiv:0907.5229 [hep-ph].

- J. F. Donoghue, E. Golowich, and B. R. Holstein, Dynamics of the Standard Model. Cambridge University Press, 1994. [CrossRef]

- C. P. Burgess, Introduction to Effective Field Theory: Thinking Effective Field Theoretically. Cambridge University Press, 2020. [CrossRef]

- B. Carr and F. Kühnel, “Primordial black holes as dark matter: Recent developments,” Annual Review of Nuclear and Particle Science 70 no. 1, (Oct., 2020) 355–394. [CrossRef]

- N. D. Birrell and P. C. W. Davies, Quantum Fields in Curved Space. Cambridge University Press, 1982.

- T. Suzuki, “Low-energy effective theories from QCD,” Prog. Theor. Phys. Suppl. 131 (1998) 633–644.

- H. Dosch, G. de Téramond, and S. Brodsky, “Light front holographic qcd and chiral symmetry breaking,” Nuclear and Particle Physics Proceedings 318-323 (2022) 133–137. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2405601422000293. QCD 21 is the 24th International Conference on Quantum Chromodynamics.

- J. Polchinski, String Theory, Vol. 1: An Introduction to the Bosonic String. Cambridge University Press, 1998. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).