Submitted:

22 October 2025

Posted:

23 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Field Equations

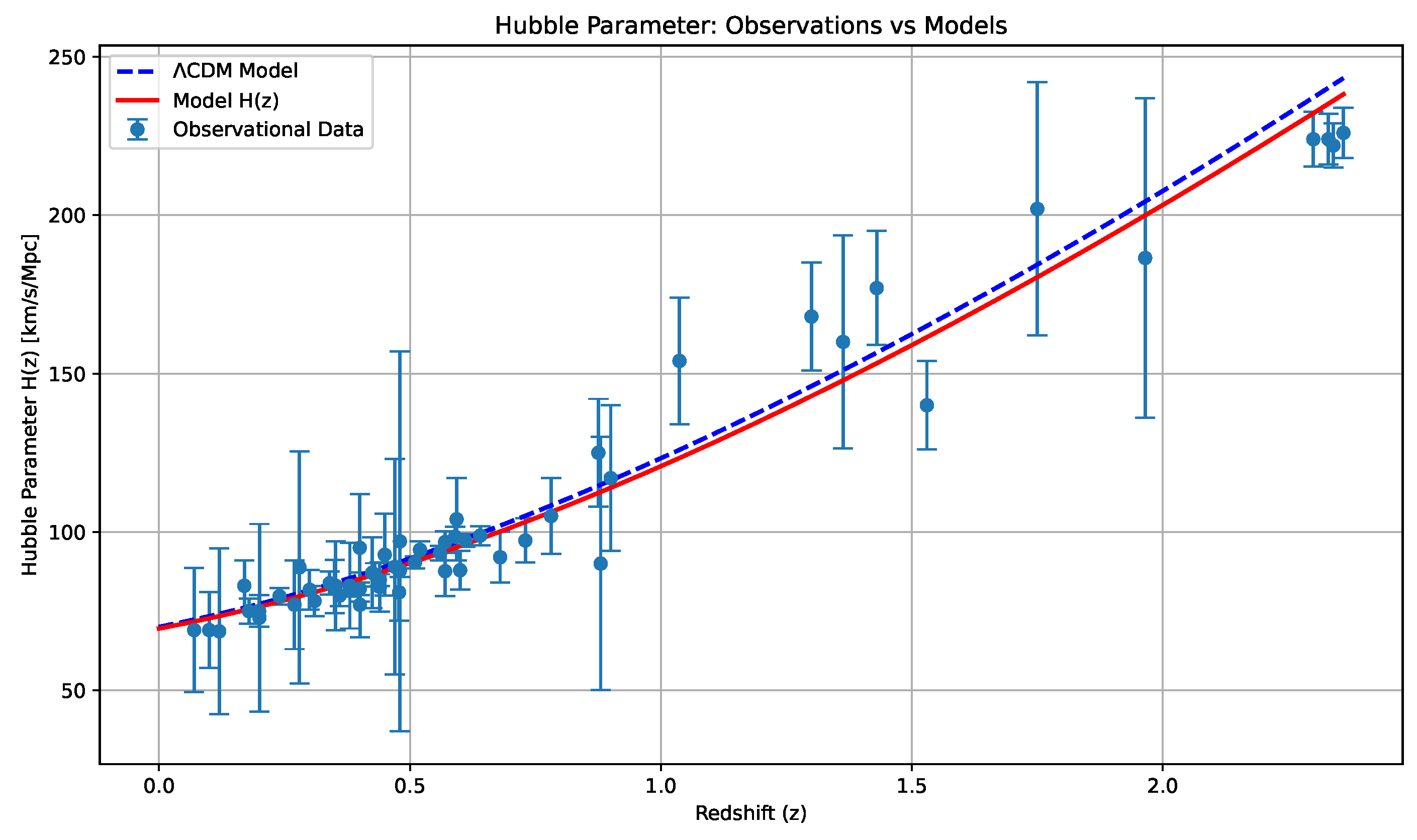

3. Parametrization of Hubble Parameter

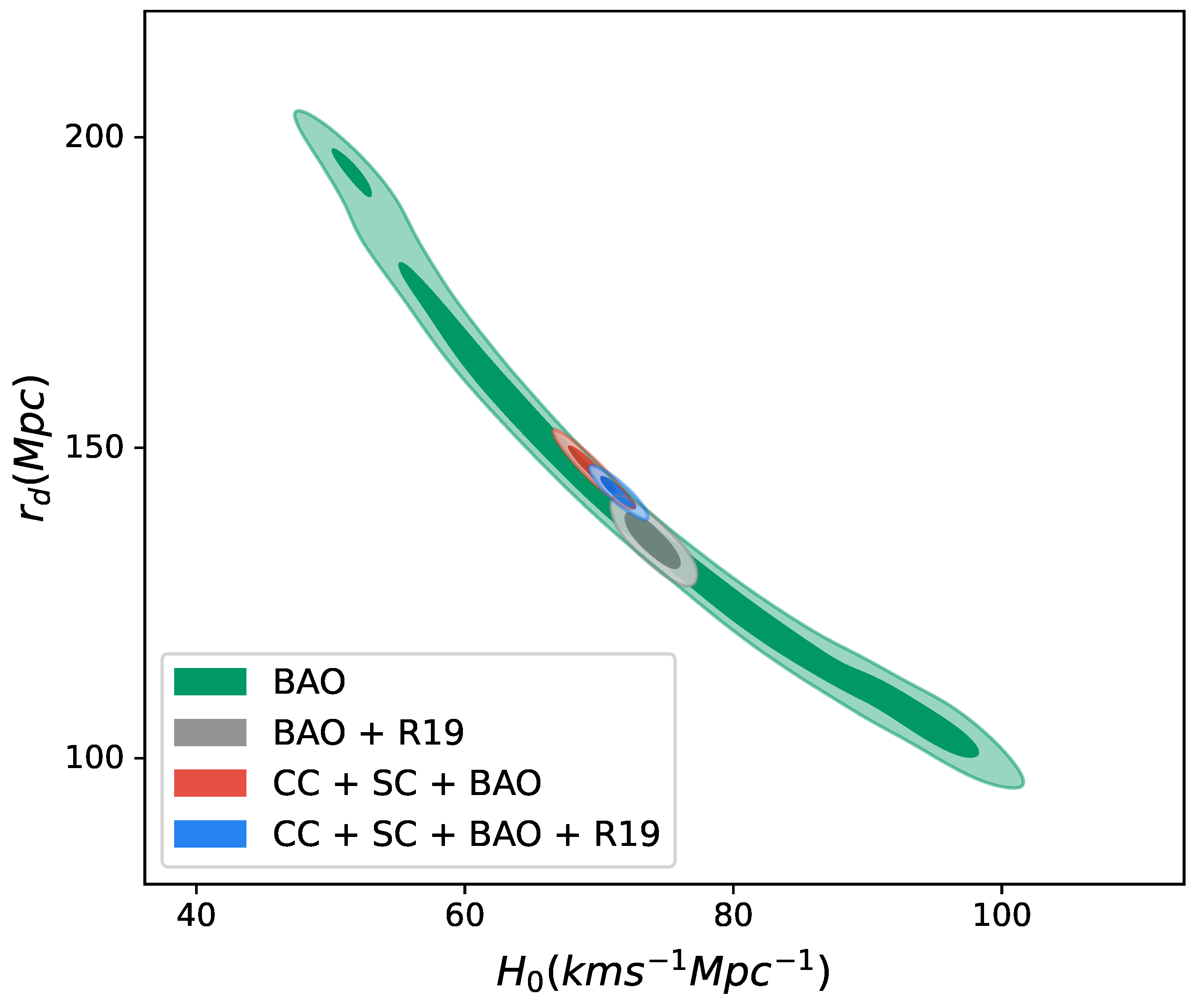

4. Datasets and Observational Framework

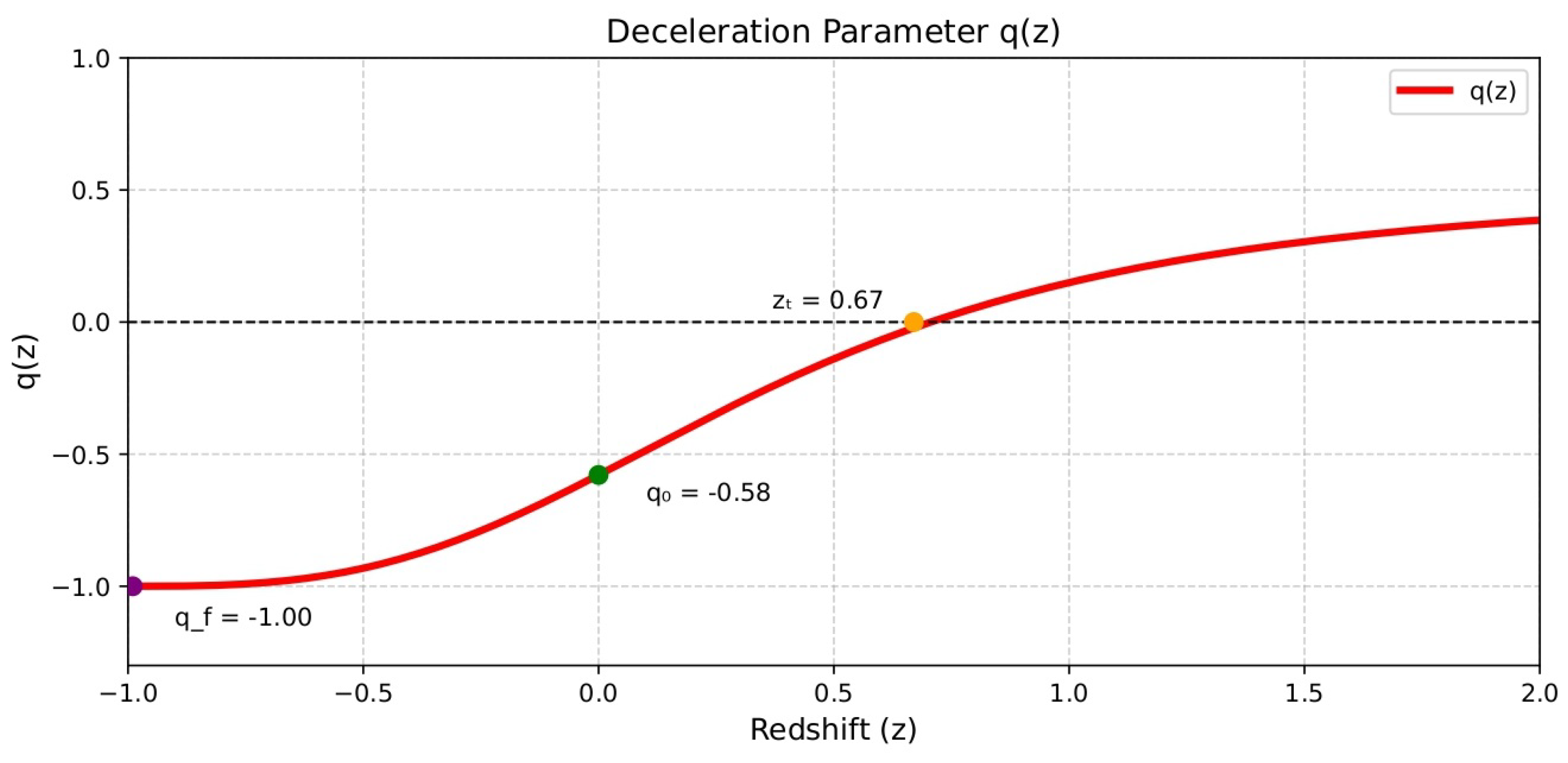

5. Cosmographic Parameters

5.1. Deceleration Parameter

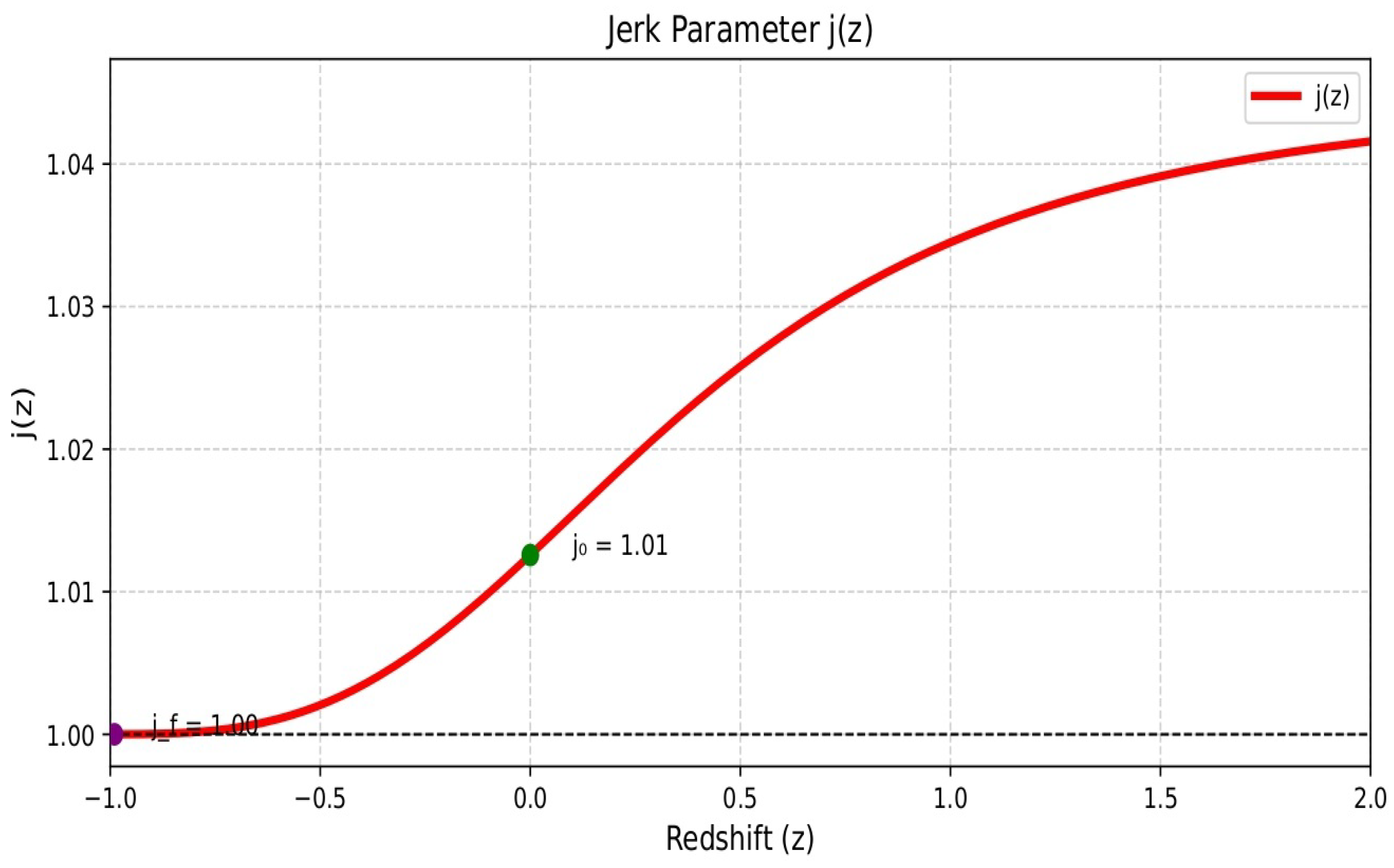

5.2. Jerk Parameter

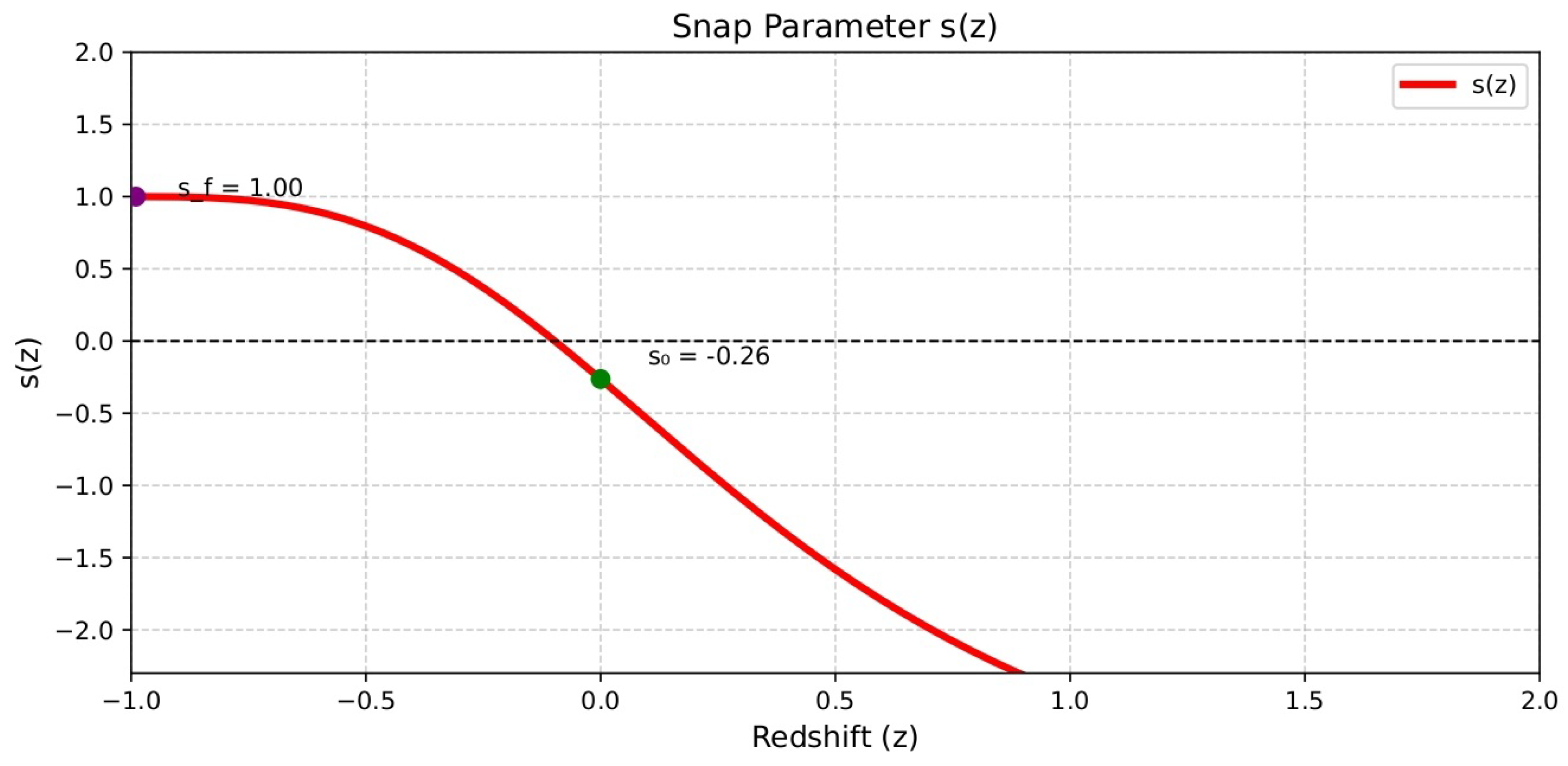

5.3. Snap Parameter

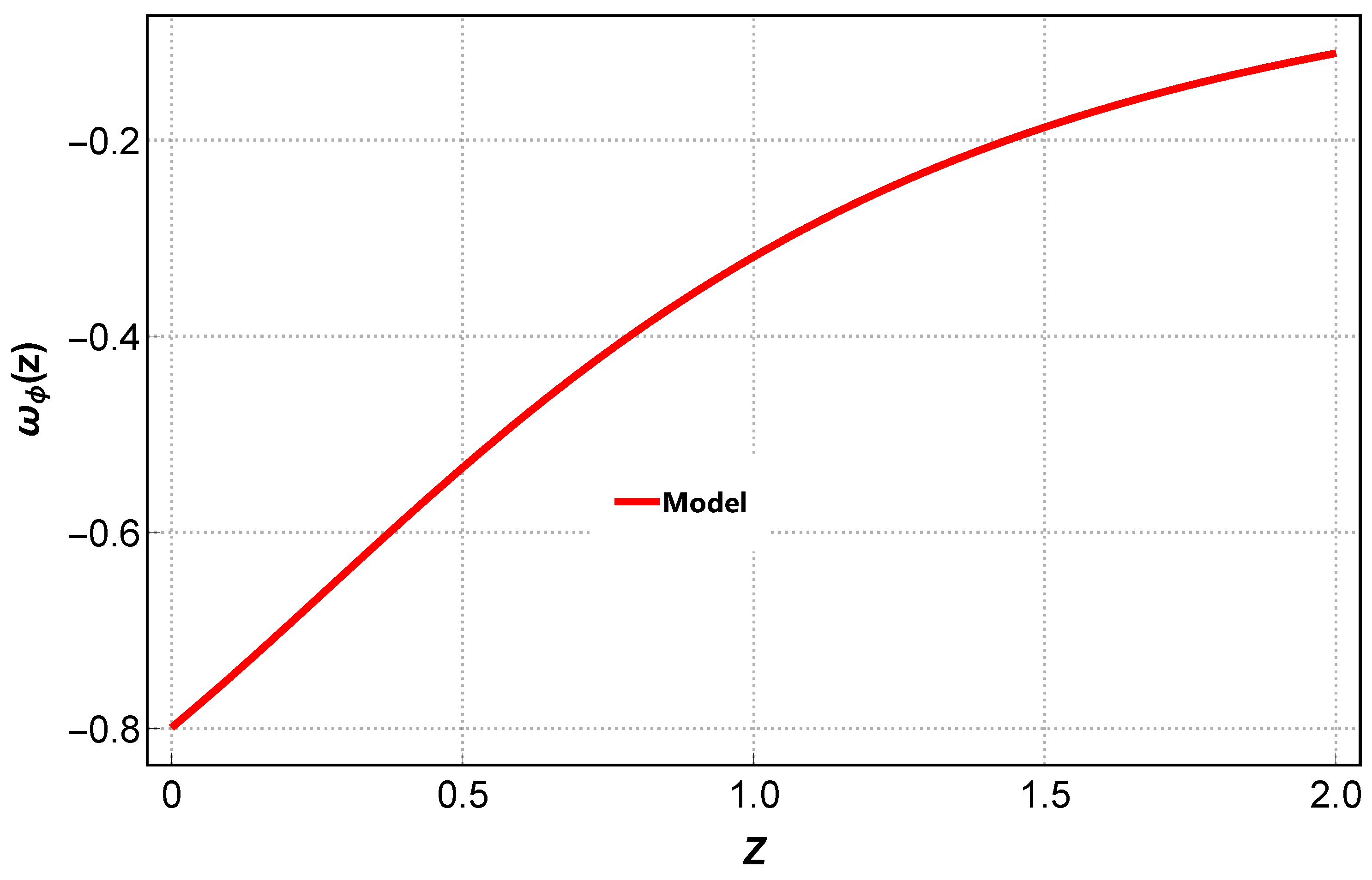

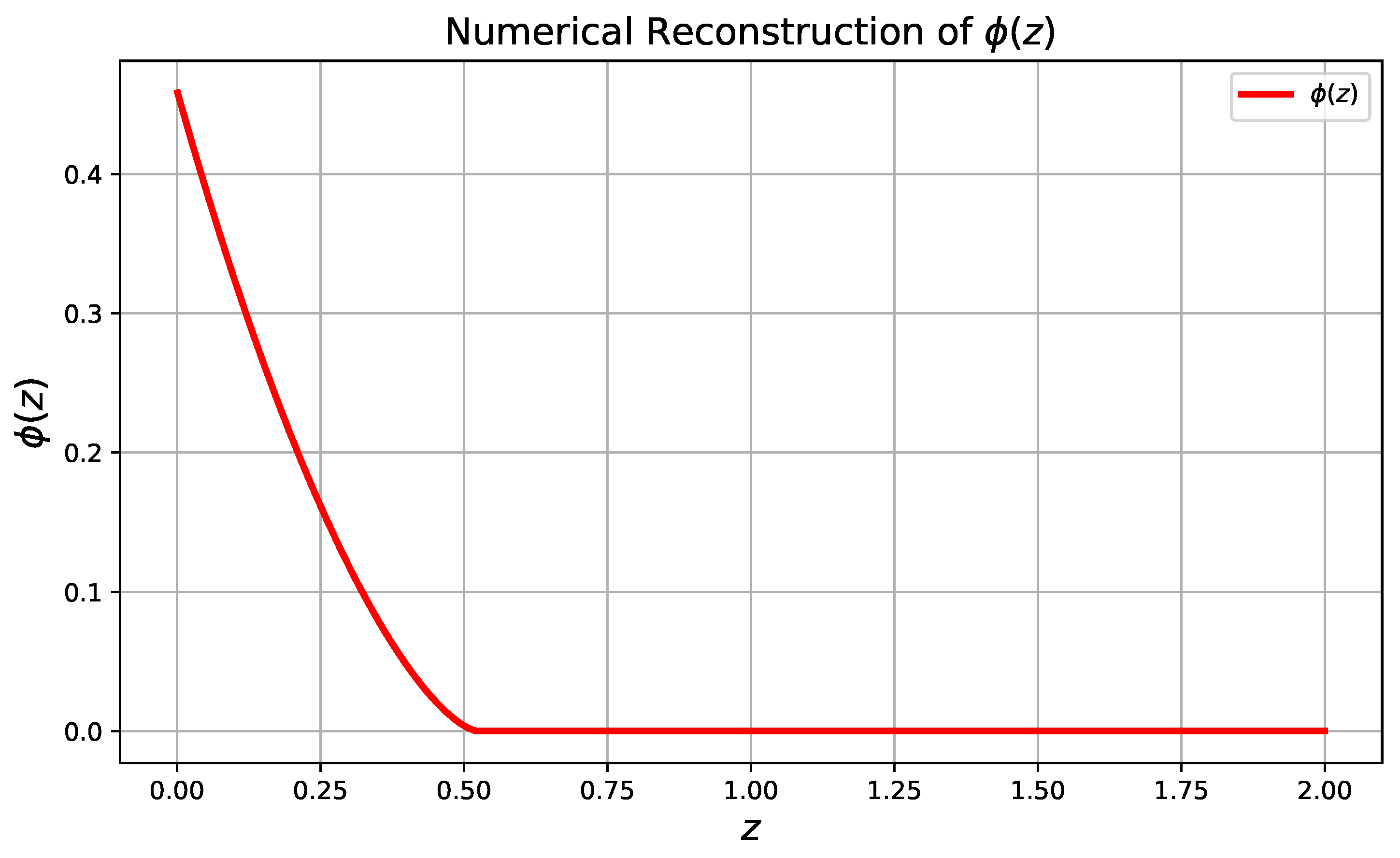

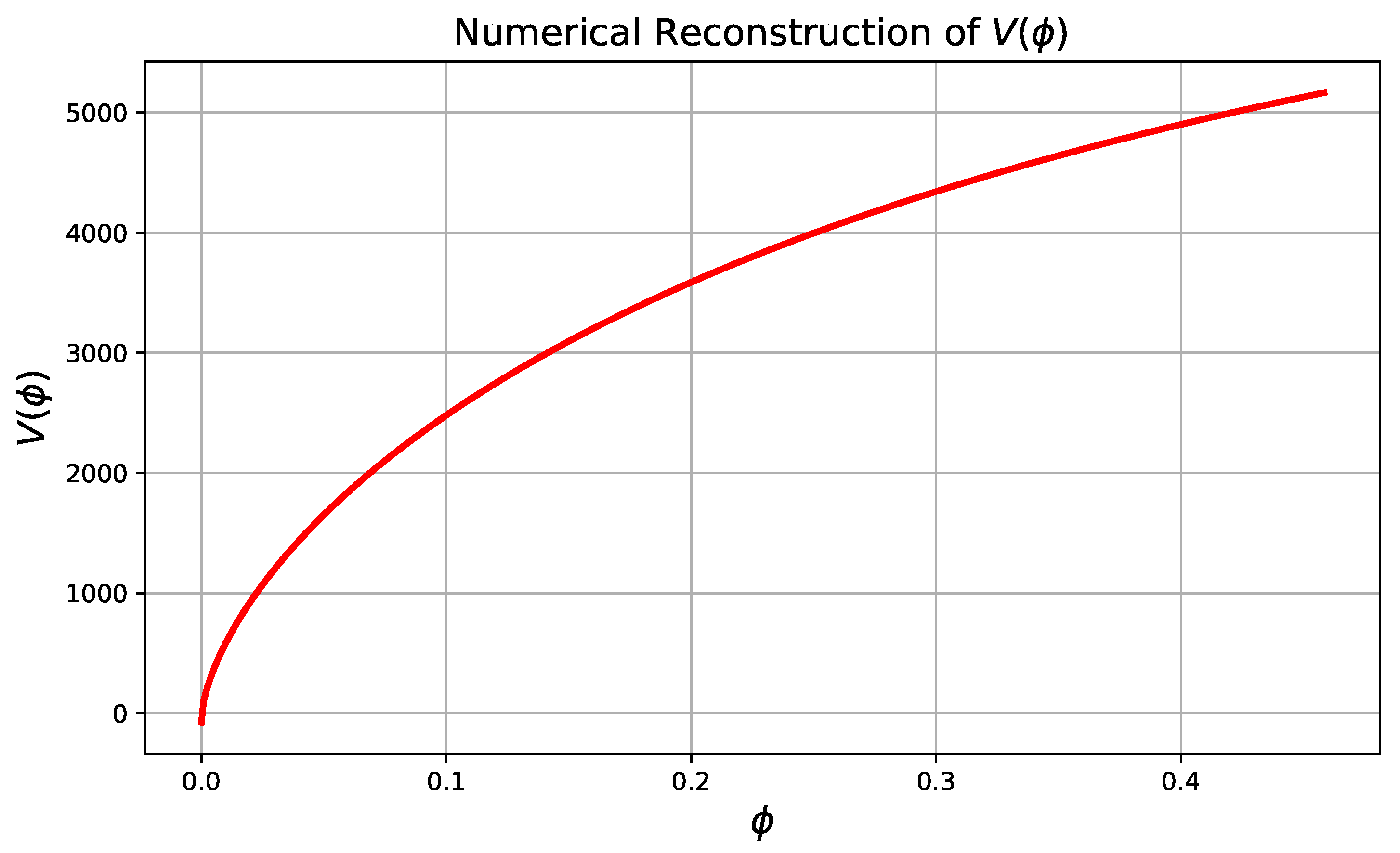

6. Physical Characteristics of Quintessence as a Dark Energy Source: Cosmic Evolution

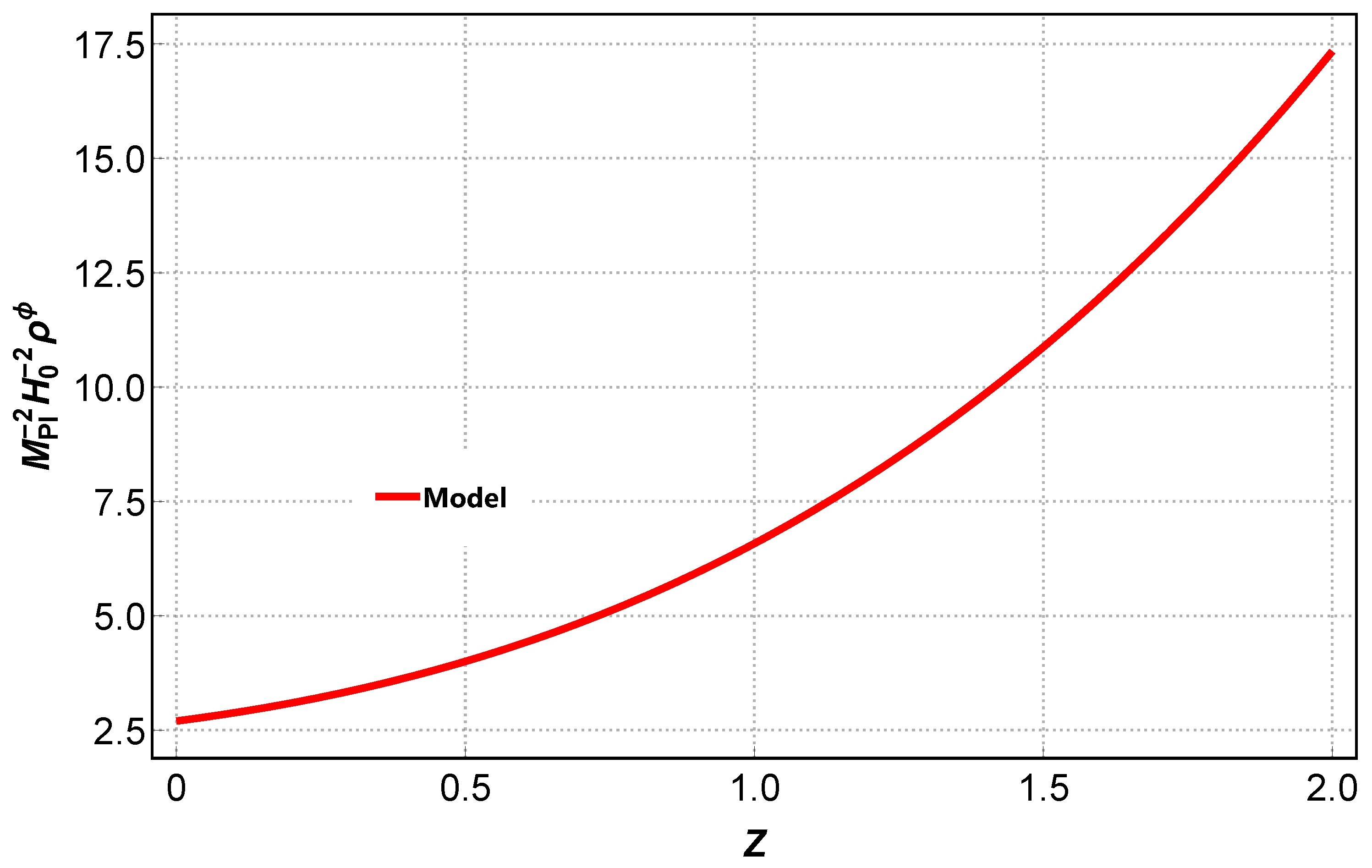

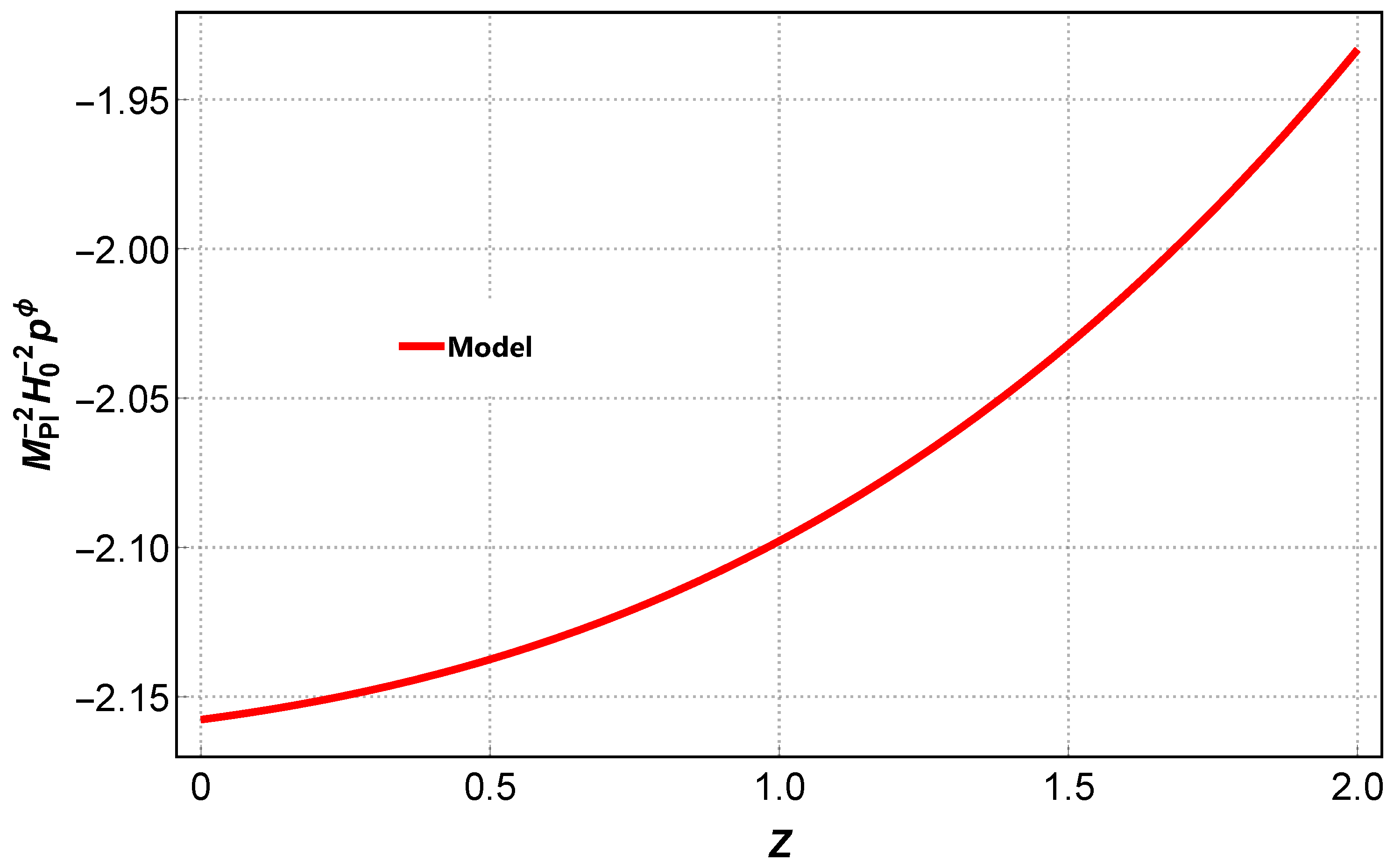

Kinetic and Potential Terms of the Scalar Field

7. Conclusion

References

- Riess, A.G.; Filippenko, A.V.; Challis, P.; Clocchiatti, A.; Diercks, A.; Garnavich, P.M.; Gilliland, R.L.; Hogan, C.J.; Jha, S.; Kirshner, R.P.; et al. Observational evidence from supernovae for an accelerating universe and a cosmological constant. The Astronomical Journal 1998, 116, 1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perlmutter, S.; et al. . Measurements of Ω and Λ from 42 high-redshift supernovae. The Astrophysical Journal 1999, 517, 565–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collaboration, P. Planck 2018 results. VI. Cosmological parameters. Astronomy & Astrophysics 2020, 641, A6. [Google Scholar]

- Riess, A.G.; et al. . A 2.4% determination of the local value of the Hubble constant. The Astrophysical Journal 2016, 826, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riess, A.G.; et al. . Cosmic distances calibrated to 1% precision with Gaia EDR3 parallaxes and Hubble Space Telescope photometry of 75 Milky Way Cepheids confirm tension with ΛCDM. The Astrophysical Journal Letters 2021, 908, L6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aylor, K.; Joy, M.; Knox, L.; Millea, M.; Raghunathan, S.; Story, K. Sounds Discordant: Classical distance ladder and ΛCDM–based determinations of the cosmological sound horizon. The Astrophysical Journal 2019, 874, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knox, L.; Millea, M. Hubble constant hunter’s guide. Physics Reports 2021, 913, 1–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appleby, S.; Battye, R. Do Consistent F(R) Models Mimic General Relativity plus Lambda ? Physics Letters B 2007, 654, 7–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amendola, L.; et al. . Conditions for the cosmological viability of f(R) dark energy models. Phys. Rev. D. 2007, 75, 083504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saffari, R.; Rahvar, S. Consistency Condition of Spherically Symmetric Solutions in f(R) Gravity. Phys. Rev. D. 2008, 77, 104028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nashe, G. Energy Conditions of Built-In Inflation Models in f(T) Gravitational Theories. General Relativity and Gravitation 2015, 47, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Setare, M.; Mohammadipour, N. Can f(T) gravity theories mimic ΛCDM cosmic history. Journal of Cosmology and Astroparticle Physics 2013, 2013, 015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harko, T.; et al. . f(R,T) gravity. Phys. Rev. D. 2011, 84, 024020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahlu, S.; Alfedeel, A.H.A.; Abebe, A. The cosmology of f(R,Lm) gravity: constraining the background and perturbed dynamics 2024. arXiv:astro-ph.CO/2406.08303].

- Jiménez, J.B.; Heisenberg, L.; Koivisto, T. Coincident general relativity. Phys. Rev. D 2018, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez, J.B.; Heisenberg, L.; Koivisto, T.; Pekar, S. Cosmology in f(Q) geometry. Phys. Rev. D 2020, 101, 103507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Li, G.; Harko, T.; Liang, S.D. f (Q, T) gravity. The European Physical Journal C 2019, 79, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratra, B.; Peebles, P.J.E. Cosmological consequences of a rolling homogeneous scalar field. Phys. Rev. D 1988, 37, 3406–3427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- COPELAND, E.J.; SAMI, M.; TSUJIKAWA, S. DYNAMICS OF DARK ENERGY. International Journal of Modern Physics D 2006, 15, 1753–1935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zlatev, I.; Wang, L.; Steinhardt, P.J. Quintessence, Cosmic Coincidence, and the Cosmological Constant. Physical Review Letters 1999, 82, 896–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinhardt, P.J.; Wang, L.; Zlatev, I. Cosmological tracking solutions. Phys. Rev. D 1999, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johri, V.B. Genesis of cosmological tracker fields. Phys. Rev. D 2001, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amendola, L.; Tocchini-Valentini, D. Stationary dark energy: The present universe as a global attractor. Phys. Rev. D 2001, 64, 043509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gasperini, M.; Piazza, F.; Veneziano, G. Quintessence as a runaway dilaton. Phys. Rev. D 2001, 65, 023508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armendariz-Picon, C.; Mukhanov, V.; Steinhardt, P.J. Dynamical Solution to the Problem of a Small Cosmological Constant and Late-Time Cosmic Acceleration. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2000, 85, 4438–4441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyle, L.A.; Caldwell, R.R.; Kamionkowski, M. Spintessence! New models for dark matter and dark energy. Physics Letters B 2002, 545, 17–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jawad, A.; Majeed, A. Correspondence of pilgrim dark energy with scalar field models. Astrophysics and Space Science 2015, 356, 375–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiba, T.; Okabe, T.; Yamaguchi, M. Kinetically driven quintessence. Phys. Rev. D 2000, 62, 023511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadjadi, H.M.; Alimohammadi, M. Transition from quintessence to the phantom phase in the quintom model. Phys. Rev. D 2006, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ade, P.A.R.; et al. . Planck2015 results: XXVIII. ThePlanckCatalogue of Galactic cold clumps. Astronomy &; Astrophysics 2016, 594, A28. [Google Scholar]

- Kamenshchik, A.; Moschella, U.; Pasquier, V. An alternative to quintessence. Physics Letters B 2001, 511, 265–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafieloo, A.; Kim, A.G.; Linder, E.V. Gaussian process cosmography. Physical Review D 2012, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafieloo, A.; Kim, A.G.; Linder, E.V. Model independent tests of cosmic growth versus expansion. Phys. Rev. D 2013, 87, 023520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinda, B.R. Model independent parametrization of the late time cosmic acceleration: Constraints on the parameters from recent observations. Phys. Rev. D 2019, 100, 043528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corasaniti, P.S.; Copeland, E.J. Model independent approach to the dark energy equation of state. Physical Review D 2003, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouali, A.; Chaudhary, H.; Mehrotra, A.; Pacif, S.K.J. Model-independent study for a quintessence model of dark energy: Analysis and observational constraints. Fortschritte der Physik 2023, 71, 2300086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimdahl, W.; Pavón, D. Statefinder parameters for interacting dark energy. General Relativity and Gravitation 2004, 36, 1483–1491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertolami, O.; Martins, P.J. Nonminimal coupling and quintessence. Physical Review D 2000, 61, 064007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, N.; Pavón, D. Cosmic acceleration without quintessence. Physical Review D 2001, 63, 043504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Overduin, J.; Cooperstock, F. Evolution of the scale factor with a variable cosmological term. Physical Review D 1998, 58, 043506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saini, T.D.; Raychaudhury, S.; Sahni, V.; Starobinsky, A.A. Reconstructing the cosmic equation of state from supernova distances. Physical Review Letters 2000, 85, 1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, J.; Verde, L.; Jimenez, R. Constraints on the redshift dependence of the dark energy potential. Physical Review D—Particles, Fields, Gravitation, and Cosmology 2005, 71, 123001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, S.; Das, R.K.; Pan, S. Parametrizing the Hubble function instead of dark energy: Many possibilities. Phys. Rev. D 2025, 112, 043542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benisty, David. ; Pan, Supriya.; Staicova, Denitsa.; Di Valentino, Eleonora.; Nunes, Rafael C.. Late-time constraints on interacting dark energy: Analysis independent of H0, rd, and MB. Astronomy and Astrophysics 2024, 688, A156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, S.; Bhattacharya, S.; Chakraborty, S. An analytic model for interacting dark energy and its observational constraints. Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society [https://academic.oup.com/mnras/article-pdf/452/3/3038/4928979/stv1495.pdf]. 2015, 452, 3038–3046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, S.; Sharov, G.S. A model with interaction of dark components and recent observational data. Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 2017, 472, 4736–4749, [https://academic.oup.com/mnras/articlepdf/472/4/4736/21077284/stx2278.pdf]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, T.Y.; Yin, J.J.; Wang, Z.Y.; Han, Z.W.; Yang, R.J. A new parametrization of Hubble function and Hubble tension. Journal of Cosmology and Astroparticle Physics 2024, 2024, 028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharov, G.S.; Bhattacharya, S.; Pan, S.; Nunes, R.C.; Chakraborty, S. A new interacting two-fluid model and its consequences. Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 2016, 466, 3497–3506, [https://academic.oup.com/mnras/article-pdf/466/3/3497/10904540/stw3358.pdf]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handley, W. Curvature tension: Evidence for a closed universe. Physical Review D 2021, 103, L041301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valentino, E.D.; Melchiorri, A.; Silk, J. Cosmic discordance: Planck and luminosity distance data exclude ΛCDM. arXiv preprint, 2020; 5arXiv:2003.04935. [Google Scholar]

- Cuceu, A.; Farr, J.; Lemos, P.; Font-Ribera, A. Baryon acoustic oscillations and the Hubble constant: Past, present and future. Journal of Cosmology and Astroparticle Physics 2019, 2019, 044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.K.; Motloch, P.; Hu, W.; Raveri, M. Hubble constant difference between CMB lensing and BAO measurements. Physical Review D 2020, 102, 023510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beutler, F.; Blake, C.; Colless, M.; Jones, D.H.; Staveley-Smith, L.; Campbell, L.; Parker, Q.; Saunders, W.; Watson, F. The 6dF Galaxy Survey: Baryon acoustic oscillations and the local Hubble constant. Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 2011, 416, 3017–3032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, A.J.; Samushia, L.; Howlett, C.; Percival, W.J.; Burden, A.; Manera, M. The clustering of the SDSS DR7 main galaxy sample–I. A 4 per cent distance measure at z = 0.15. Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 2015, 449, 835–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blazek, J.A.; McEwen, J.E.; Hirata, C.M. Streaming velocities and the baryon acoustic oscillation scale. Physical Review Letters 2016, 116, 121303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellejero-Ibanez, M.; Chuang, C.H.; Rubiño-Martín, J.; Cuesta, A.J.; Wang, Y. ; b. Zhao, G.; Ross, A.J.; Rodríguez-Torres, S.; Prada, F.; Slosar, A.; et al. The clustering of galaxies in the completed SDSS-III Baryon Oscillation Spectroscopic Survey: double-probe measurements from BOSS galaxy clustering & Planck data–towards an analysis without informative priors. arXiv preprint, 2016; arXiv:1607.03152. [Google Scholar]

- Blake, C.; Brough, S.; Colless, M.; Contreras, C.; Couch, W.; Croom, S.; Croton, D.; Davis, T.M.; Drinkwater, M.J.; Forster, K.; et al. The WiggleZ Dark Energy Survey: Joint measurements of the expansion and growth history at z < 1. Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 2012, 425, 405–414. [Google Scholar]

- Seo, H.J.; Ho, S.; White, M.; Cuesta, A.J.; Ross, A.J.; Saito, S.; Reid, B.; Padmanabhan, N.; Percival, W.J.; Putter, R.D.; et al. Acoustic scale from the angular power spectra of SDSS-III DR8 photometric luminous galaxies. The Astrophysical Journal 2012, 761, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soumagnac, M.; Barkana, R.; Sabiu, C.; Loeb, A.; Ross, A.; Abdalla, F.; Balan, S.; Lahav, O. Large scale distribution of total mass versus luminous matter from baryon acoustic oscillations: First search in the SDSS-III BOSS data release 10. arXiv preprint 2016, arXiv:1602.01839. [Google Scholar]

- Sridhar, S.; Song, Y.S.; Ross, A.J.; Zhou, R.; Newman, J.A.; Chuang, C.H.; Blum, R.; Gaztanaga, E.; Landriau, M.; Prada, F. Clustering of LRGs in the DECaLS DR8 footprint: Distance constraints from baryon acoustic oscillations using photometric redshifts. The Astrophysical Journal 2020, 904, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bautista, J.E.; Vargas-Magaña, M.; Dawson, K.S.; Percival, W.J.; Brinkmann, J.; Brownstein, J.; Camacho, B.; Comparat, J.; Gil-Marín, H.; Mueller, E.M.; et al. The SDSS-IV extended Baryon Oscillation Spectroscopic Survey: Baryon acoustic oscillations at redshift of 0.72 with the DR14 luminous red galaxy sample. The Astrophysical Journal 2018, 863, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mena-Fernández, J.; Rodríguez-Monroy, M.; Avila, S.; Porredon, A.; Chan, K.; Camacho, H.; Weaverdyck, N.; Sevilla-Noarbe, I.; Sanchez, E.; Cipriano, L.T.S.; et al. Dark Energy Survey: Galaxy sample for the baryonic acoustic oscillation measurement from the final dataset. Physical Review D 2024, 110, 063514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, J.; Sánchez, A.G.; Ross, A.J.; Smith, A.; Neveux, R.; Bautista, J.; Burtin, E.; Zhao, C.; Scoccimarro, R.; Dawson, K.S.; et al. The completed SDSS-IV extended Baryon Oscillation Spectroscopic Survey: BAO and RSD measurements from anisotropic clustering analysis of the quasar sample in configuration space between redshift 0.8 and 2.2. Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 2021, 500, 1201–1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busca, N.G.; Delubac, T.; Rich, J.; Bailey, S.; Font-Ribera, A.; Kirkby, D.; Goff, J.M.L.; Pieri, M.M.; Slosar, A.; Aubourg, É.; et al. Baryon acoustic oscillations in the Ly-α forest of BOSS quasars. arXiv preprint 2012, arXiv:1211.2616]. [Google Scholar]

- de Sainte Agathe, V.; Balland, C.; Bourboux, H.D.M.D.; Blomqvist, M.; Guy, J.; Rich, J.; Font-Ribera, A.; Pieri, M.M.; Bautista, J.E.; Dawson, K.; et al. Baryon acoustic oscillations at z = 2.34 from the correlations of Lyα absorption in eBOSS DR14. Astronomy & Astrophysics 2019, 629, A85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, P.; Beutler, F.; Percival, W.J.; Blake, C.; Koda, J.; Ross, A.J. Low redshift baryon acoustic oscillation measurement from the reconstructed 6-degree Field Galaxy Survey. Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 2018, 481, 2371–2383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazin, E.A.; Koda, J.; Blake, C.; Padmanabhan, N.; Brough, S.; Colless, M.; Contreras, C.; Couch, W.; Croom, S.; Croton, D.J.; et al. The WiggleZ Dark Energy Survey: Improved distance measurements to z = 1 with reconstruction of the baryonic acoustic feature. Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 2014, 441, 3524–3542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moresco, M.; Verde, L.; Pozzetti, L.; Jimenez, R.; Cimatti, A. New constraints on cosmological parameters and neutrino properties using the expansion rate of the Universe to z 1.75. Journal of Cosmology and Astroparticle Physics 2012, 2012, 053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moresco, M.; Cimatti, A.; Jimenez, R.; Pozzetti, L.; Zamorani, G.; Bolzonella, M.; Dunlop, J.; Lamareille, F.; Mignoli, M.; Pearce, H.; et al. Improved constraints on the expansion rate of the Universe up to z 1.1 from the spectroscopic evolution of cosmic chronometers. Journal of Cosmology and Astroparticle Physics 2012, 2012, 006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moresco, M. Raising the bar: New constraints on the Hubble parameter with cosmic chronometers at z 2. Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society: Letters 2015, 450, L16–L20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moresco, M.; Pozzetti, L.; Cimatti, A.; Jimenez, R.; Maraston, C.; Verde, L.; Thomas, D.; Citro, A.; Tojeiro, R.; Wilkinson, D. A 6% measurement of the Hubble parameter at z 0.45: Direct evidence of the epoch of cosmic re-acceleration. Journal of Cosmology and Astroparticle Physics 2016, 2016, 014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howell, D.A.; Sullivan, M.; Nugent, P.E.; Ellis, R.S.; Conley, A.J.; Borgne, D.L.; Carlberg, R.G.; Guy, J.; Balam, D.; Basa, S.; et al. The type Ia supernova SNLS-03D3bb from a super-Chandrasekhar-mass white dwarf star. Nature 2006, 443, 308–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scolnic, D.M.; Jones, D.; Rest, A.; Pan, Y.; Chornock, R.; Foley, R.; Huber, M.; Kessler, R.; Narayan, G.; Riess, A.; et al. The complete light-curve sample of spectroscopically confirmed SNe Ia from Pan-STARRS1 and cosmological constraints from the combined Pantheon sample. The Astrophysical Journal 2018, 859, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anagnostopoulos, F.K.; Basilakos, S.; Saridakis, E.N. Observational constraints on Barrow holographic dark energy. The European Physical Journal C 2020, 80, 826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, C.; Horne, K.; Hodson, A.O.; Leggat, A.D. Tests of ΛCDM and conformal gravity using GRB and quasars as standard candles out to z∼8. arXiv preprint 2017, arXiv:1711.10369]. [Google Scholar]

- Demianski, M.; Piedipalumbo, E.; Sawant, D.; Amati, L. Cosmology with gamma-ray bursts—I. The Hubble diagram through the calibrated Ep,i–Eiso correlation. Astronomy & Astrophysics 2017, 598, A112. [Google Scholar]

- Kazantzidis, L.; Perivolaropoulos, L. Evolution of the fσ8 tension with the Planck15/ΛCDM determination and implications for modified gravity theories. Physical Review D 2018, 97, 103503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collaboration, D.; Abdul-Karim, M.; Aguilar, J.; Ahlen, S.; Alam, S.; Allen, L.; Prieto, C.A.; Alves, O.; Anand, A.; Andrade, U.; et al. DESI DR2 Results II: Measurements of Baryon Acoustic Oscillations and Cosmological Constraints, 2025. arXiv:astro-ph.CO/2503.14738. [CrossRef]

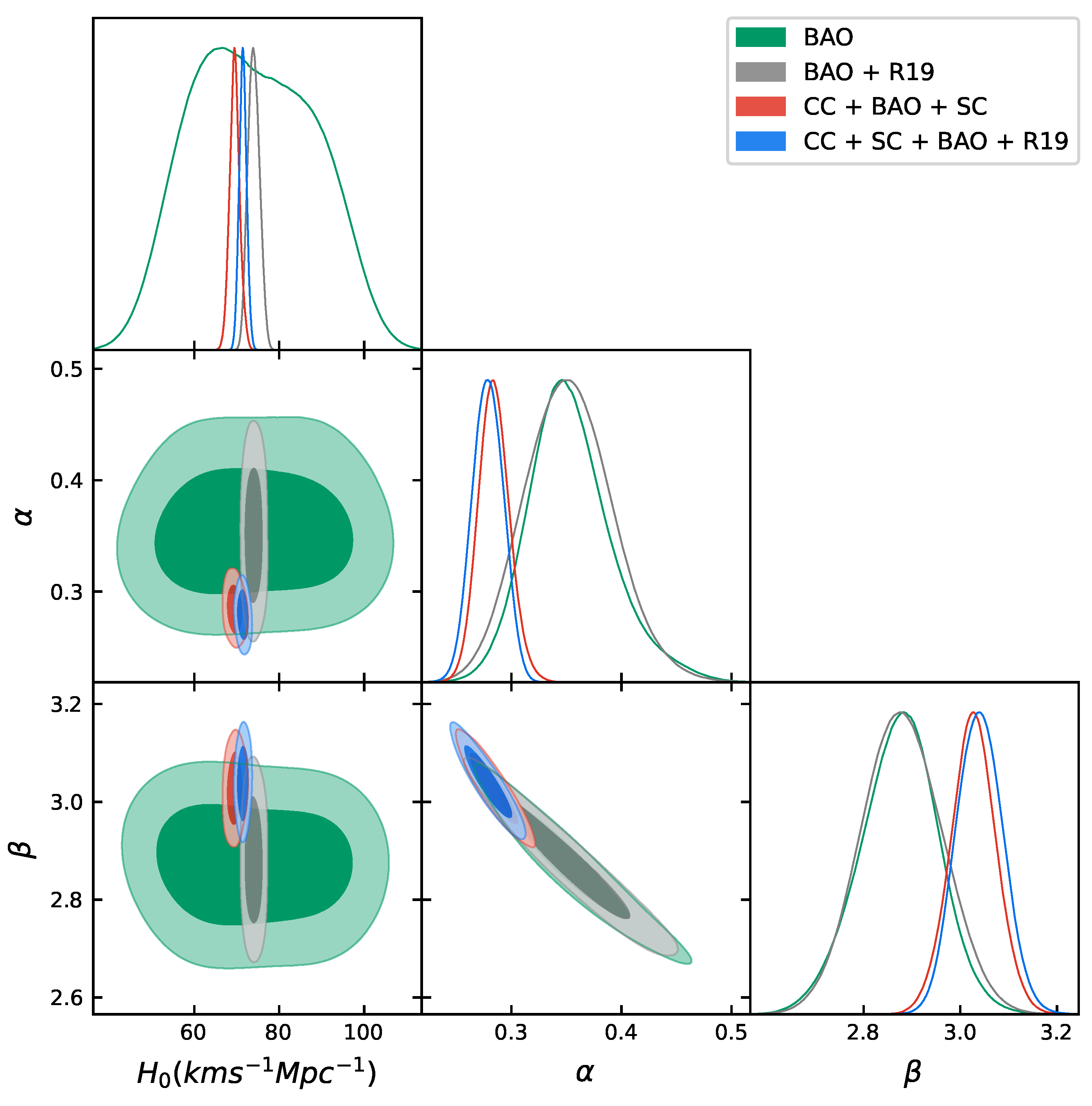

| MCMC Results | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | Parameters | Priors | BAO | BAO+R19 | CC+BAO+SC | CC+SC+BAO+R19 |

| [50,100] | ||||||

| [0,1] | ||||||

| CDM Model | [0,1] | |||||

| [100,200] | ||||||

| [0.9,1.1] | ||||||

| [50,100] | ||||||

| [0,0.6] | ||||||

| Proposed Model | [2,4] | |||||

| [100,200] | ||||||

| [0.9,1.1] | ||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).