1. Introduction

1.1. Geology and Geomorphology

The region of the Arabian Peninsula is characterized by its diverse geology and geomorphology which is reflected by its ancient geological history. Ancient shields formed in the Precambrian represented by ancient igneous and metamorphic rocks include the Arabian-Nubain Shield in the west of the Peninsula and Tuwaiq Mountains in Saudi Arabia [

1,

2,

3]. Tectonic activity has resulted in the formation of the Red Sea and the Gulf of Aden in the western and southern parts of the Arabian Peninsula and tectonic shifts and volcanic activities have resulted in areas like Harrat ar Rahat in Saudi Arabia [

4,

5]. Much of the Arabian Peninsula is covered by sedimentary rocks and basins, including the Rub’ al Khali in the southeast and region of the Persian Gulf [

6].

The different landforms of the Arabian Peninsula include its mountain ranges and plateaus, wadis, deserts and coastlines. The Asir Mountain in the south of the Peninsula and the Hijaz Mountains in the west that run along the Red Sea, range in elevations up to 3000 m, making them the highest of the mountains in the Arabian Peninsula. The Hajar mountain range in northern Oman and eastern UAE and the Dhofar mountains in southern Oman range in elevation to 3000 m (Jabal Shams in N Oman) and up to 2000 m in southern Oman (Jabal Qara). The mountains are dissected by gorges and wadis, that flow in the plains as alluvial fans. The wadis, with the exception of a few, though dry for most of the year flow when rains come. There is subsurface water and with that are habitable. The central region of the Peninsula is dominated by the Nejd plateau. It is an elevated, generally flat area with low hills ranging in elevation from 500m to 1000 m. The Nejd Plateau has been inhabited for millennia, historically in oases and by pastoral communities. It has many archaeological sites, petroglyphs, and pre-Islamic structures indicating it as a region of trade routes, and of historical and cultural significance [

7].

The deserts areas of the Arabian Peninsula formed during periods of climate change, form major landscapes of the Arabian Peninsula. The Rub’ al Khali occupies large areas of Saudi Arabia, Oman, UAE and Yemen. It is a dunes desert with gravel areas; sand dunes reach to over 250 m. Other deserts, An Nafud in north central part of Saudi Arabia and Ad Dhana in the south are characterized by sand dunes and gravel plains. The An Nafud, with its sand dunes, plateaus and wadis forms an ecological barrier separating the eastern and central parts of the Arabian Peninsula.

The Arabian Peninsula has a coastline of approximately 9,179 km, spanning several countries; it is characterized by sandy beaches, cliffs and rocky shores. Mangroves and coral reefs are present in some areas, especially along the coast of Oman, Yemen and along the Red Sea in Saudi Arabia .

Over historical times and presently, the coasts of the Arabian Peninsula have vibrant trading ports and harbours. Several countries coasts also harbour mangroves.

1.2. Climate

Throughout its geological history, the Arabian Peninsula has experienced climatic fluctuations that have greatly influenced its landscapes and ecosystems. During the Pleistocene (2.6 million to 11,700 years ago), alternated glacial and interglacial periods resulted in arid and humid conditions. These periods of arid and humid climates are evident from sediment cores from ancient lake deposits, fossilized fauna, and ancient soil layers. After the last glaciation, during the Holocene (11,700 years ago to present), the onset of warmer conditions started over the Arabian Peninsula [

8]. During the early Holocene, a more favourable climate than now prevailed with increased precipitation and expansion of vegetation cover. Archaeological sites indicate human occupation, with evidence of agricultural practices [

9]. The climate, over time, gradually became arid, leading to the formation of the desert landscapes we see today. The vegetation cover decreased and changed more to xeric trees and shrubs that are adapted to arid environments. This is evidenced from the presence of many succulent species, species inhabiting niches, and relict taxa found throughout the Arabian Peninsula.

The present climate of the Arabian Peninsula is characterized by its complex topography and atmospheric circulation and exhibits significant spatial variations [

10]. According to Koppen-Geiger climate classification [

11], the climate is classified as a ‘desert climate’ with highs of up to 45

oC in the deserts to lows of 2

o C on the highest summits of Yemen, Saudi Arabia and Oman. Winter temperatures on the lower hills and plains are usually through November to January with an average air temperature of about 22. Spring and winter seasons typically experience the highest levels of precipitation respectively. In general lower temperatures are in the north of the Peninsula and higher temperatures southwards [

10]. Through the summer, small quantities of precipitation are recorded, while the autumn season receives more precipitation than the summer season. Despite the low mean annual rainfall, isolated storm events characterized by high-intensity rainfall occur from time to time. These are typically recorded during the winter months when weather systems move from west to east, rising into the mountainous areas. According to the analysis of rainfall data recorded at the Tabuk Gauging Station (NW Saudi Arabia), a 6-hour duration storm will yield approximately 60 mm of rainfall on average once every 50 years, with the possibility of a rainfall intensity of almost 100 mm/hour during the peak of the storm. The intensity of rainfall events, coupled with sparse vegetation cover, often results in flash flooding.

Rainfall patterns vary greatly from place to place in the Arabian Peninsula. Comparing climatic data during the recent past (1994–2009) and long term data (> 30 years: 1979–2009) the Arabian Peninsula and at the station level over Saudi Arabia, show a significant decrease of rainfall and an increase of mean temperature. However, it is shown that rainfall has increased in the south of the Arabian Peninsula and in particular along the Red Sea coast in recent decades, compared with that in the 1980s, different from results seen over inland [

12].

2. Ecoregions and Plant Diversity

There are approximately 4,000 taxa in the Arabian Peninsula with endemism estimated to be about 20% (c. 800 taxa) [

13] (

Table 1). The majority of plants are present on the mountains and lower hills of Yemen, Saudi Arabia and Oman. Country-wise, Yemen, Saudi Arabia and Oman are the richest in plant taxa and also have the highest endemism (

Table 1). The United Arab Emirates has several regional endemics on its eastern mountainous areas.

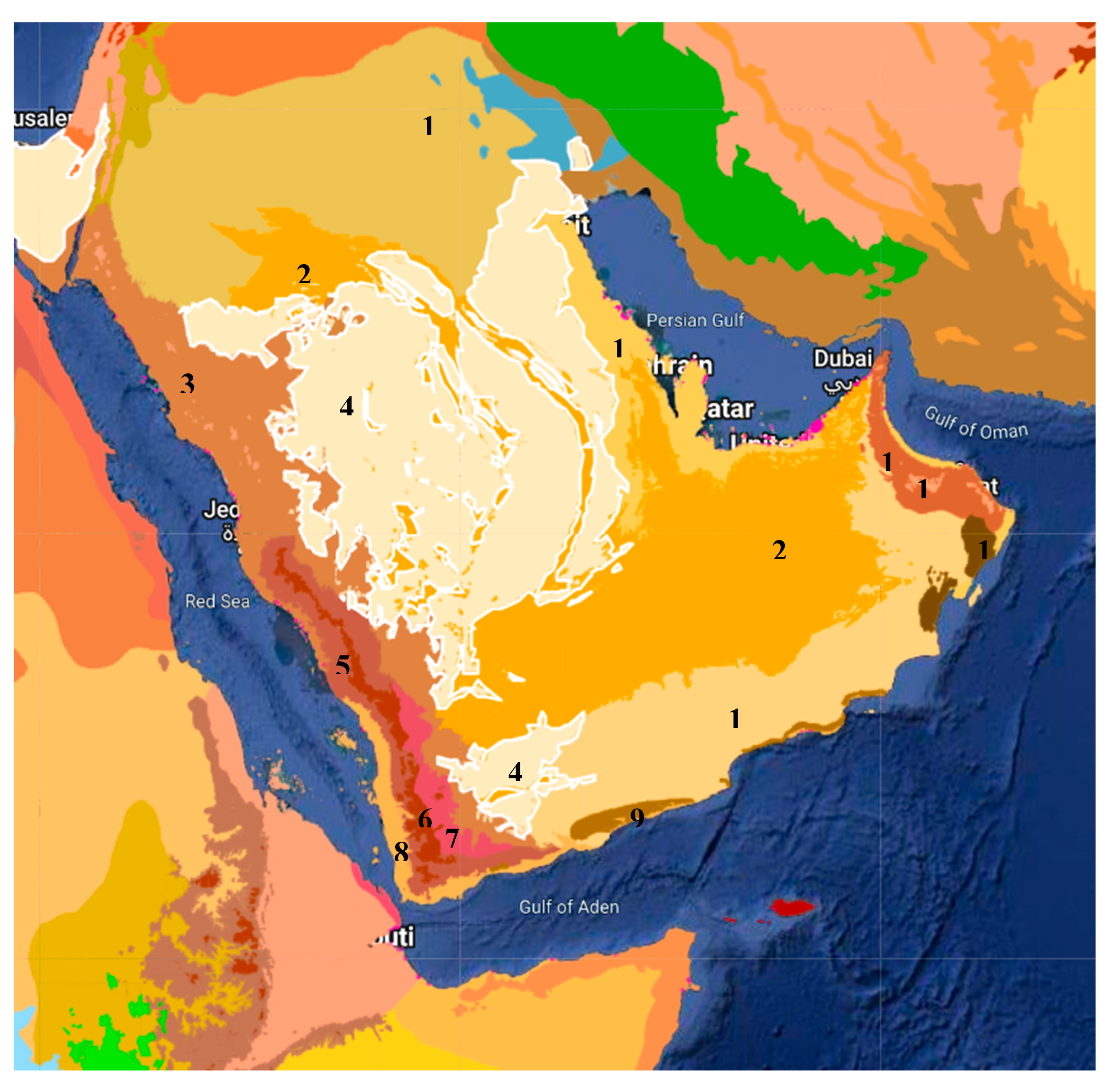

The ecoregions of the Arabian Peninsula were outlined in Dinerstein et al. [

14], (

Figure 1). In general terms, the vegetation of the mountains of the Arabian Peninsula consists of open montane and deciduous woodlands, deciduous and semi-evergreen shrublands and grasslands. Xerophytic plant communities on the slopes and rocky summits are common on the mountains. Three species of

Juniperus, J. phoenicea, J. procera and

J. seravschanica, occur in the montane regions of the Peninsula.

J. phoenicea is a Mediterranean element that occurs in western Saudi Arabia,

J. procera in the southwest and west of the Arabian Peninsula in Yemen and Saudi Arabia and is sympatric with

J. phoenicea along the escarpment mountains in the vicinity of Taif.

J. seravschanica an Irano-Turanian species occurs in the western Hajar range of the northern mountains of Oman [

15,

16]. These three species are at their outmost posts in the mountains of the Arabian Peninsula and are relict taxa there in a state of decline [

17,

18].

Drought-deciduous

Vachellia (Acacia) and semi-evergreen

Olea europaea open woodlands are the dominant vegetation over the lower altitudes of most of the western, southwestern and eastern mountains of the Peninsula. In Yemen and southern Oman

Vachellia is associated with

Commiphora to form a mosaic of open

Vachellia -Commiphora shrubland. Many other species of shrubs and trees are associated with

Vachellia and

Commiphora, in different parts of the Peninsula, including several succulent communities that are found mainly in rocky areas. Orophytic grasslands are present in the montane regions of the Arabian Peninsula, mostly above 1000 m elevation and form the dominant fodder vegetation. At lower and middle altitudes fodder is usually tree and shrub browse, whilst at higher altitudes grasses and herbs are the main fodder vegetation [

19].

Wadis are the most inhabited areas in the Arabian Peninsula. The vegetation of the wadis is determined by the nature of the drainage system, the groundwater level, the sediment type and overflow frequency. They are in general dominated by Tamarix spp., and a variety of different species depending on the region of the Arabian Peninsula: a Mediterranean-Sub Saharan type with Retama raetam, Nerium oleander and Pistacia atlantica, or a north Arabian Vachellia pseudo-savanna with Saharan shrubs in the understorey, or a southeastern community type with Saccharum griffithii, Nerium oleander and Dyerophytum indicum or a southwestern riparian forest of tropical character, rich in Sudanian vegetation type. Wadis have been greatly reformed due to habitation and development and grazing by livestock throughout the Peninsula.

Characteristic to the Arabian Peninsula are its sand dune deserts that occupy almost a third of the land area of the Peninsula. The sands are largely unstable and poor in nutrients, but compared to silty or clay soils have a high porosity and permeability with deep moisture penetration. Evaporation of the upper few centimetres of sand is rapid, but much slower below, allowing plant growth of a few species, such as

Calligonum comosum whose extensive horizontal root system enables it to make optimum use of moisture. Tussock grasses, such as

Centropodia, and sedges a such as

Cyperus aucheri are able to grow on soft sands of slip faces. Rhizosheaths characteristic of the root systems of desert perennial grasses such as

Stipagrostis plumosa also play an important role in water absorption and nitrogen fixing in sandy soils. Nitrogen fixing bacteria have been found associated with the root sheaths formed of matted root hairs and sand grains held by secreted mucilage [

20,

21]. Annuals are common after winter or spring rain, exhibiting a typical desert ephemeral life cycle with rapid germination, development and flowering and fruiting.

The diverse geomorphology of the coastline greatly influences the distribution of species on the coasts and coastal sabkhas of the Arabian Peninsula. Coastal and sabkha vegetation are poor in species diversity, and show marked zonation patterns. Inland sabkhas are virtually unvegetated, with a few fringing halophytic species.

Avicennia marina¸ the native mangrove species, has a patchy distribution all along the coasts of the Peninsula [

22].

3. Biogeography

The Arabian Peninsula is not a centre of diversity for crops and Nikolai Vavilov would not have visited there to collect seeds of crops or crop wild relatives for a northern temperate country. Despite the presence of the wild olive on the highest mountains of Yemen, Saudi Arabia and Oman and Pistacia khinjuk on the mountains of NW Saudi Arabia, the floral diversity of the Arabian Peninsula is not home to the variety of wild relatives of crops of agricultural use as in the Fertile Crescent. However, had the science of genetics were developed, he may perhaps have looked for relict species and species with disjunct distribution patterns to collect their genetic material as a resilient genetic resource for tolerance of drought and salinity.

Distribution patterns of the present floras of the Arabian Peninsula reflect its past floristic ties with African, Iranian and SW Mediterranean floristic elements. The SW region of Arabia, the escarpment mountains of SW Saudi Arabia, Yemen and Dhofar, forms an integral part of Africa, both in geological and biogeographical terms. The majority of the species found below 1500 m elevation in southern Arabia also occur in NE and E Africa [

23]. These include several species of

Vachellia (

V. asak,

V. etbaica,

V. hamulosa,

V. oerfota),

Boswellia sacra,

Cadaba baccarinii,

Commiphora (

C. foliacea,

C. gileadensis,

C. kua,

C. myrrha,

C. schimperi), species of

Lannea,

Maytenus,

Premna,

Rhigozum,

Turraea. Several Afromontane genera such as

Anagyris,

Ceratonia,

Juniperus,

Iris,

Myrsine,

Pavetta,

Teclea reach the SW region of Saudi Arabia, Yemen and southern Oman. It has been suggested that these Ethiopian-Somalian taxa migrated from Africa and became established at a time when the climate was relatively more moist than today and the desert areas between the northern and southern regions of Arabia narrower [

19].

Floral similarities on the montane regions of Northern Oman, UAE and Baluchistan and SW Iran suggests that plant communities with

Juniperus seravaschanica,

Helianthemum lippii,

Ephedra pachyclada, and associated species such as

Cymbopogon schoenanthus,

Lonicera hypoleuca and

Sageretia thea,

Berberis baluchistanica,

Prunus arabica migrated from Baluchistan and SW Iran across the Persian Gulf during the humid period some 30,000 to 20,000 years BP [

23,

24]. Over the last arid phase (between 11,000 and 4000 years BP), distribution declined and became restricted to favourable areas at high elevations on the Northern mountains of Oman.

Ceratonia oreothauma subsp.

oreothauma, endemic, on the summit areas of the eastern Hajar mountains, is a Nubo-Sindian relic confined to a few localities such as gorges and depressions that relatively more moist [

25].

Recent surveys on mountains summits of NW Saudi Arabia shows these to be a bioclimatic refuge for relict Mediterranean and Irano-Turanian species. The cool and relatively humid conditions support plant communities with open evergreen woodlands of scattered

Juniperus phoenicea, with

Pistacia khinjuk,

Retama raetam,

Moringa peregrina, Olea europaea subsp.

cuspidata,

Dodonaea angustifolia,

Globularia arabica, and a dense ground layer of Irano-Turanian taxa such as

Artemisia sieberi, and

Astracantha echinus subsp.

arabica. Relict Mediterranean and Irano-Turanian taxa include

Thymus decussatus,

Phlomis brachyodon,

Atraphaxis spinosa,

Verbascum decaisneanum,

Dianthus sinaicus,

Daphne linearifolia,

Ephedra pachyclada var.

sinaica,

Ajuga chamaepitys subsp.

tridactylites,

Colutea istria,

Echinops glaberrimus, and

Scorzonera intricata.

Pistacia khinjuk, an Irano-Turanian species that probably migrated pre-Pleistocene (together with other species such as

Prunus korshinskyi,

Pistacia atlantica,

Astragalus echinus and

Retama raetam into the mountains of northwest Saudi Arabia from the Kurdo-Zagrosian mountains).

Pistacia khinjuk is confined exclusively to the higher mountains of northwest Saudi Arabia. It is rare in Saudi Arabia, its southernmost limit in distribution is Egypt (Sinai) and Sudan [

26].

Borrell et al. [

27], studied the distribution of endemic plant species in central Oman, which is classified as one of the centres of endemism in Oman [

28,

29]. They showed that the central desert of Oman presented a southern Arabian Pleistocene refugium, with a high number of endemic species within a narrow monsoon-influenced region. They suggest the vegetation there is a relict of an earlier, more mesic period.

The presence of Amaranthaceous genera such as

Anabasis setifera,

Anabasis articulata, Atriplex leucoclada, Noaea mucronata, Caroxylon villosum in the Arabian Peninsula are examples of the Sahara-Arabian desert flora from the Mesogean stock (of the region that developed into the Mediterranean Sea [

19]. A single Afro-montane species,

Euryops jaberiana is endemic to the NW mountains of Saudi Arabia [

30]. A second species,

Euryops arabicus is found in the Arabian Peninsula in the mountains of northern Oman and Yemen, and in Djibuti and Somalia in NE Africa [

31,

32].

E. jaberiana,

E. arabicus and

E. socotranus (the latter two found also in Socotra & Ethiopia) are the only three taxa found outside Africa.

Many of the relict plants of Mediterranean, Eurasian, or African origin, survive in small populations in restricted localities on the summits and gorges of the mountains of southern and western Arabia and on the northern mountains of Oman. Such populations play an important role in the conservation and dissemination of genetic material, as well as in the evolution of new forms. The refugia habitats support plants that have remained in the area from various penetrations of floras in the remote past, and may hold the genetic resilience to survive present climatic changes.

4. Conservation

The widespread and accelerated loss of biological diversity and the importance of this loss to a region’s economy and culture is well recognised. The Arabian Peninsula has been relatively slow to recognise and act upon its loss of biodiversity, but over the last two decades, several measures are being taken to address this. Most of the countries of the Arabian Peninsula are signatory to the Convention of Biological Diversity and have taken active participation at COP meetings. A target of establishing 17% of protected areas in a country is being considered seriously and the conservation of plant genetic resources, primarily through the establishment of seed banks, is been addressed.

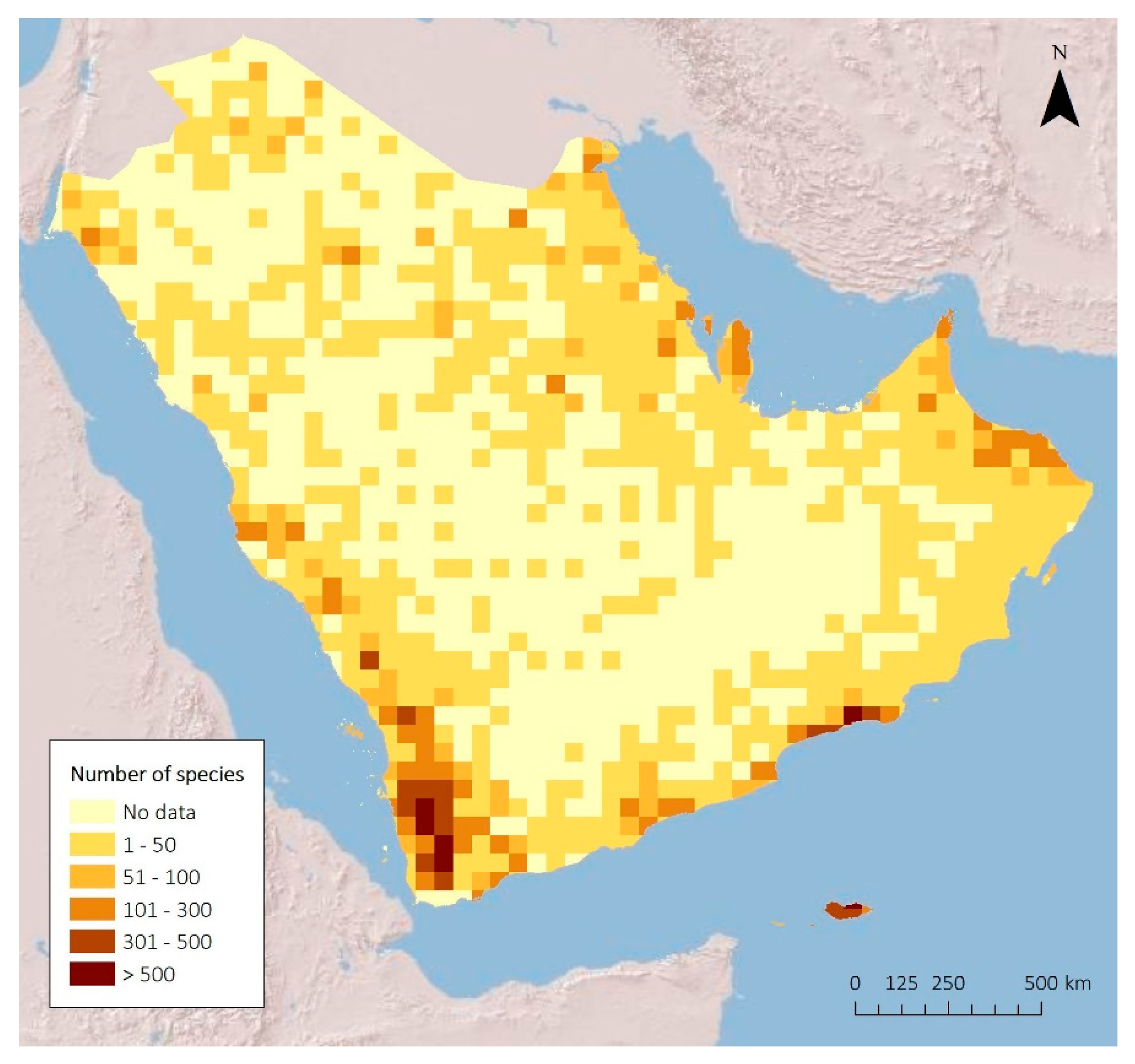

A recently available Red List for the plants of the Arabian Peninsula summarises the conservation status of some plants [

33]. The List shows that of a total of 797 taxa that were formally assessed (according to the IUCN guidelines), 232 (29%) were found to be threatened. Several biodiversity hotspots are recognised and it can be clearly be seen that the number of species, and especially the number of endemic species, are concentrated in specific localities (

Figure 2). The biodiverse areas are 1) the southwest mountains of Yemen which are part of the Eastern Afromontane Biodiversity hotspot, 2) several Regional Centres of Plant Diversity, e.g., the fog oasis of Dhofar, southern Oman, the Harrat Al-Harrah Highlands of South-western Arabia, Hadramaut, Jebel Areys and the island of Soqotra. The Soqotra Archipelago is also a UNESCO World Heritage Site and Man and Biosphere Reserve recognizing globally its unique natural heritage. There are also several Ramsar sites across the peninsula e.g., Hawar Islands of Bahrain, and the Mubarak Al-Kabeer Reserve in Kuwait.

Official or unpublished Regional Red Lists of plants are now available for Oman [

28,

34], the UAE [

35], and Saudi Arabia [

36], but a Red List for all plants of the Arabian Peninsula is not yet available. Several countries of the Arabian Peninsula have officially designated Nature Reserves to conserve and protect the country’s floral and faunal diversity and to carry out plant surveys to document and map their floral diversity.

There is also now a concentrated effort to document the plant genetic resources (PGR) of the Arabian Peninsula. PGRs, especially crop wild relatives (CWR) provide a major resource of food for present and future generations and provide promising alternatives in developing new and desirable crop varieties through different plant breeding approaches. Countries of the Arabian Peninsula, such as Saudi Arabia have been a part of International Treaty on PGR for Food and Agriculture which aims to conserve, utilize, and share the benefits of available genetic diversity and resources [

37,

38]. An analysis of the floras from the Arabian Peninsula shows that there are over 400 wild relatives of some 70 food and forage crops. These species, because of their survival and adaptation to the extreme arid climate of the Arabian Peninsula are an important source of genetic resource which can be used for crop improvement programmes directed towards climate change [

39]. More recently, seeds of five crop’s of high value as food were collected in the south eastern province of Jazan of Saudi Arabia and stored in seed banks to preserve the genetic diversity of these crops and as well continued to cultivate (in situ conservation) [

40]. In Oman, the discovery of wild date palms has also been used to trace the domestication history of the date palm [

41].

Summary

The Arabian Peninsula is unique due to its geographical position and diverse biogeographic realms, which include the Palearctic, Afrotropical, and Indomalayan regions. It is home to a rich and diverse flora and has several species that are remnants of a once widespread distribution. The mountains create cooler and more moderate climates, leading to the formation of special ecosystems that serve as refugia for plant and animal species. There is a high level of plant species unique to the region. Due to its long history of human habitation and subsistence agriculture, particularly in the mountainous areas, the Arabian Peninsula possesses unique crop varieties adapted to extreme arid climates, making them important genetic resources for the future in the face of climate change.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, for research facilities for this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Brook, M.C., Al Shoukri, S., Amer, K.M., Böer, B. and Krupp, F., Physical and environmental setting of the Arabian Peninsula and surrounding seas. Policy Perspectives for Ecosystem and Water Management in the Arabia Peninsula. UNESCO Doha and United Nations University, Hamilton, Ontario, 2006, 1–16.

- Guba, I., and Glennie, K., Geology and geomorphology. In, Vegetation of the Arabian Peninsula, 1998, pp. 39–62. Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands.

- Johnson, P. R., and Woldehaimanot, B., Development of the Arabian-Nubian Shield: perspectives on accretion and deformation in the northern East African Orogen and the assembly of Gondwana. Geological Society, London, Special Publications, 206(1), 289–325. [CrossRef]

- Bosworth, W., Huchon, P., & McClay, K. The Red Sea and Gulf of Aden Basins, In, The Geology of East Africa. 2005, 43(1–3), 334–378. [CrossRef]

- Camp, V. E., & Roobol, M. J., The Arabian continental alkali basalt province: Part I. Evolution of Harrat Rahat, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. In, Bulletin of the Geological Society of America. 1989.

- Glennie, K. W., Desert Sedimentary Environments. In, Desert Sedimentary Environments: Developments in Sedimentology. Elsevier, 2010, Jan. 15.

- Parker, A.G., Pleistocene climate change in Arabia: Developing a framework for hominin dispersal over the last 350 ka. Quaternary International, 2008, 182(1): 49–57.

- Fleitmann, D., Burns, S.J., Neff, U., Mudelsee, M., Mangini, A. and Matter, A., Palaeoclimatic interpretation of high-resolution oxygen isotope profiles derived from annually laminated speleothems from Southern Oman. Quaternary Science Reviews, 2007, 26(13-14): 170–188. [CrossRef]

- Petraglia, M.D., Parton, A., Groucutt, H.S. and Alsharekh, A., Green Arabia: Human prehistory at the crossroads of continents. Quaternary International 2015, 382: 1–7. [CrossRef]

- Patlakas, P., Stathopoulos, C., Flocas, H., Kalogeri, C. and Kallos, G., Regional climatic features of the Arabian Peninsula. Atmosphere, 2019, 10(4): 220. [CrossRef]

- Geiger, R., Klassifikation der Klimate nach W. Koppen [Classification of climates after W. Koppen]. Landolt-Bornstein – Zahlenwerte und Funktionen aus Physik, Chemie, Astronomie, Geophysik und Technik, alte Serie. Berlin: Sringer. 1954, vol. 3, 603–607.

- Almazroui, M., Islam, M.N., Jones, P.D., Athar, H. and Rahman, M.A.,. Recent climate change in the Arabian Peninsula: seasonal rainfall and temperature climatology of Saudi Arabia for 1979–2009. Atmospheric Research, 2012, 111: 29–45. [CrossRef]

- Dinerstein, E., Olson, D., Joshi, A., Vynne, S., Burgess, N., Wikramanayake, E., Hahn, N., Palminteri, S., Hedao, P., Noss, R., Hansen, M., Locke, H., Elis, E., Jones, B., Victor Barbar, C., Hayes, R., Kormoa, C., Martin, V., Crist, E., Sechrest, W., Price, P., Baillie, J., Weeden, D., Suckling, K., Davis, C., Sizer, N., Moore, R., Thau, D., Birch, T., Potapopv, P., Turubanova, S., Tyukavina, A., de Souza, N., Pintea, L., Brito, J., Llewellyn, O., Miller, A., Patzelt, A., Ghazanfar, S., Timberlake, J., Klӧser, H., Shennan-Farpón, Y., Kindt, R., Lilleso, J.-P., van Breugel, P., Graudal, L., Voge, M., Al-Shammari, K., Saleem, M. Forum: An Ecoregion-Based Approach to Protecting Half the Terrestrial Realm. BioScience bix014, 2017. The full article is available at: https://academic.oup.com/biosci/article-lookup/doi/10.1093/biosci/bix014. An interactive ecoregion map of the world with protection status by region is available at: ecoregions2017.appspot.com. [CrossRef]

- Miller, A.G. & T.A. Cope, Flora of the Arabian Peninsula and Socotra, 1996, Vol. 1. Edinburgh University Press. Edinburgh.

- Hall, J.B., Juniperus excelsa in Africa: a biogeographical study of an Afromontane tree. Journal of biogeography 1984, 1: 47–61. [CrossRef]

- Fisher, M. and Gardner, A.S., The status and ecology of a Juniperus excelsa subsp. polycarpos woodland in the northern mountains of Oman. Vegetatio, 1995, 119: 33–51. [CrossRef]

- Fisher, M.,. Decline in the juniper woodlands of Raydah Reserve in southwestern Saudi Arabia: a response to climate changes? Global Ecology and Biogeography Letters, 1997, 379–386.

- MacLaren, C.A., Climate change drives decline of Juniperus seravschanica in Oman. Journal of Arid Environments, 2016, 128, 91–100. [CrossRef]

- Kürschner, H., Biogeography and introduction to vegetation. In, Vegetation of the Arabian peninsula 1998, 63–98. Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands. [CrossRef]

- Danin, A., Plant adaptations to environmental stresses in desert dunes. Plants of desert dunes, 1996, 133–152.

- Mandaville, J.P., Vegetation of the Sands. In, Vegetation of the Arabian Peninsula 1998, 191–208. Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands.

- Ghazanfar, S.A., Böer, B., Al Khulaidi, A.W., El-Keblawy, A. and Alateeqi, S., Plants of Sabkha ecosystems of the Arabian Peninsula. Sabkha Ecosystems: Volume VI: Asia/Pacific, 2019, 55–80.

- White, F. and Léonard, J., Phytogeographical links between Africa and southwest Asia. Fl. Veg. Mundi, 1991, 9, 229–246.

- Mandaville, J.P., Studies in the flora of Arabia XI: some historical and geographical aspects of a principal floristic frontier. Notes from the Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh, 1984, 42: 1–15.

- Ghazanfar, S.A., 1999. Present flora as an indicator of palaeoclimate: examples from the Arabian Peninsula. Palaeoenvironmental reconstruction in arid lands. Balkema, Rotterdam Brookfield, 1999, 263–275.

- Ghazanfar, S., Hopkins, E., Brown, G., Llewllyn, O., Ismael, B., Olson, D., Ramalho, R., Floral surveys of mountain peaks in NW Saudi Arabia: a refuge for Mediterranean and Irano-Turanian species, Euro-Mediterranean Conference for Environmental Integration, Proceedings, 2023 (in press).

- Borrell, J.S., Al Issaey, G., Lupton, D.A., Starnes, T., Al Hinai, A., Al Hatmi, S., Senior, R.A., Wilkinson, T., Milborrow, J.L., Stokes-Rees, A. and Patzelt, A. Islands in the desert: environmental distribution modelling of endemic flora reveals the extent of Pleistocene tropical relict vegetation in southern Arabia. Ann. Bot., 2019, 124(3), 411–422. [CrossRef]

- Ghazanfar, S.A., Status of the flora and plant conservation in the Sultanate of Oman. Biological Conservation, 1998, 85(3), 287–295. [CrossRef]

- Patzelt, A., Synopsis of the flora and vegetation of Oman, with special emphasis on patterns of plant endemism. Abhandlungen der Braunschweigischen Wissenschaftlichen Gesellschaft, 2015, 282: 317. 3: 282.

- Chaudhary, S.A., Flora of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, Ministry of Agriculture & Water Research Center, National Herbarium, Saudi Arabia, 2000, vol. 2, part 3, 191–192.

- Ghazanfar, S.A., Flora of the Sultanate of Oman, Vol. 3, Loganiaceae-Asteraceae (Text + photo CD-ROM). Scripta Botanica Belgica series 55. Belgium: National Botanic Garden of Belgium, Meise. 2015, 236–237.

- Thulin, M., Euryops in Flora of Somalia. Royal Botanic Gardens. 2006,Vol. 3, 539–540.

- Forrest, A. and Neale, S., The Conservation Status of the Plants of the Arabian Peninsula: Endemic Taxa, Trees, and Aloes. Environment and Protected Areas Authority, Sharjah, UAE. 2023, 48pp.

- Patzelt, A., Oman Red Data Book, Diwan of Royal Court, Office for Conservation of the Environment, Muscat, Sultanate of Oman, 2009, pp310.

- Allen, D.J., Westrip, J.R.S., Puttick, A., Harding, K.A., Hilton-Taylor, C. and Ali, H.. UAE National Red List of Vascular Plants. Technical Report. Ministry of Climate Change and Environment, United Arab Emirates, Dubai. 2021. https://www.nationalredlist.org/publication/uae-national-red-list-vascular-plants.

- Thomas, J. https://www.plantdiversityofsaudiarabia.info/Biodiversity-Saudi-Arabia/Conservation/Conservation.htm.

- FAO, The international treaty for plant genetic resources for food and agriculture, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Rome, 2004. http://www.planttreaty.org/training/annex1_en.htm.

- Almarri, N.B., Ahmad, S., Elshal, M.H., Diversity and Conservation of Plant Genetic Resources in Saudi Arabia. In: Sustainable Utilization and Conservation of Plant Genetic Diversity. Sustainable Development and Biodiversity, 2024, vol 35, 1009–1031. Springer, Singapore. [CrossRef]

- Kameswara Rao, N. Crop wild relatives from the Arabian Peninsula. Genet. Resour. Crop. Evol. 2013, 60, 1709–1725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Turki, T.A., Al-Namazi, A.A.; Masrahi, Y.S. Conservation of genetic resources for five traditional crops from Jazan, SW Saudi Arabia, at the KACST Gene-Bank. Saudi Journ. Biological Sci. 2019, 26(7), 1626–1632. [CrossRef]

- Gros-Balthazard, M., Galimberti, M., Kousathanas, A., Newton, C., Ivorra, S., Paradis, L., Vigouroux, Y., Carter, R., Tengberg, M., Battesti, V. and Santoni, S., The discovery of wild date palms in Oman reveals a complex domestication history involving centers in the Middle East and Africa. Current Biology, 2017, 27(14), 2211–2218. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).