1. Introduction

Olea europaea L. is one of the oldest cultivated plants in the Mediterranean and worldwide, which domestication dates back 6,000 years in the Middle East and the Aegean Sea, before it was spread in the Mediterranean basin by the Phoenicians and Greeks [

1,

2,

3]. Centuries-old olive trees can be found along the Aegean Sea between Greece and eastern Turkey. On Crete, the largest Greek island, there is a 3,000-year-old olive tree of exceptional dimensions in the area of Kavousi, with a circumference of 14.2 meters and a diameter of almost 5 meter’s [

4]. There are also centenary olive trees on Mount Tabor and in Urla, a small Turkish peninsula, as well as in Spain and Italy [

5]. In Tunisia, the olive tree was an integral part of the Berber, Carthaginian, and Roman civilizations and served many purposes such as providing oil for food, medicine, lighting and wood for the construction of ships and tools [

6]. The olive tree also played an important role in shaping the landscape, preserving the environment and contrasting desertification and climate change. [

7] claims that the Carthaginians and the Romans played a crucial role in promoting olive cultivation in ancient Tunisia by transforming vast arid areas into productive land. The trade exchange between the Phoenicians and the Romans facilitated the introduction of genes of foreign varieties into the Tunisian olive germplasm and allowed the development of an impressive diversification of the olive tree [

8]. The long history of olive cultivation in Tunisia and the genetic flow from other Mediterranean germplasms have produced a large panoply of autochthonous varieties, totaling over 200 [

9]. Nevertheless, ninety per cent of olive production is accounted for by two highly productive olive varieties: Chetoui in the north and Chemlali in central and southern Tunisia. The remaining 10 per cent is accounted for by several minor varieties grown in marginal areas and cultivated by a few farmers in small local groves [

9,

10,

11]. In Tunisia, it is common to see olive trees several hundred-years-old, scattered across the landscape, reflecting the deep respect and admiration that the local communities have for these ancient trees. They can be considered as an invaluable reservoir of genetic diversity and several studies have shown that they could have great potential to improve olive production, oil quality and disease resistance of commercial varieties [

8,

11,

12,

13].

Interest in this olive heritage is increasing in Mediterranean countries and there are more and more initiatives to preserve and promote its conservation and valorization [

14]. In Tunisia, a research team from the National Gene Bank of Tunisia searched throughout the country for centenary olive trees from the Roman and Carthaginian and found several giant olive trees with a circumference of 15 meters, a diameter of 0.50 meters and grey trunks with knots [

15]. These centuries-old olive trees produce oils of better quality than most commercially available varieties in Tunisia, suggesting that they may have a peculiar genetic background [

13]. To fully understand and exploit the most of the historical and agronomic value of these trees, it is crucial to identify the most valuable specimens and carry out a genetic characterization. To achieve this goal, a set of nuclear SSR markers was used to genotype 26 historically important olive tree cultivars from different regions of Tunisia. Subsequently, these accessions were compared with local cultivars and other Mediterranean varieties. The results will provide important insights into the origin of these valuable genetic resources and shed light on their historical distribution and migration patterns in the southern Mediterranean.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Material

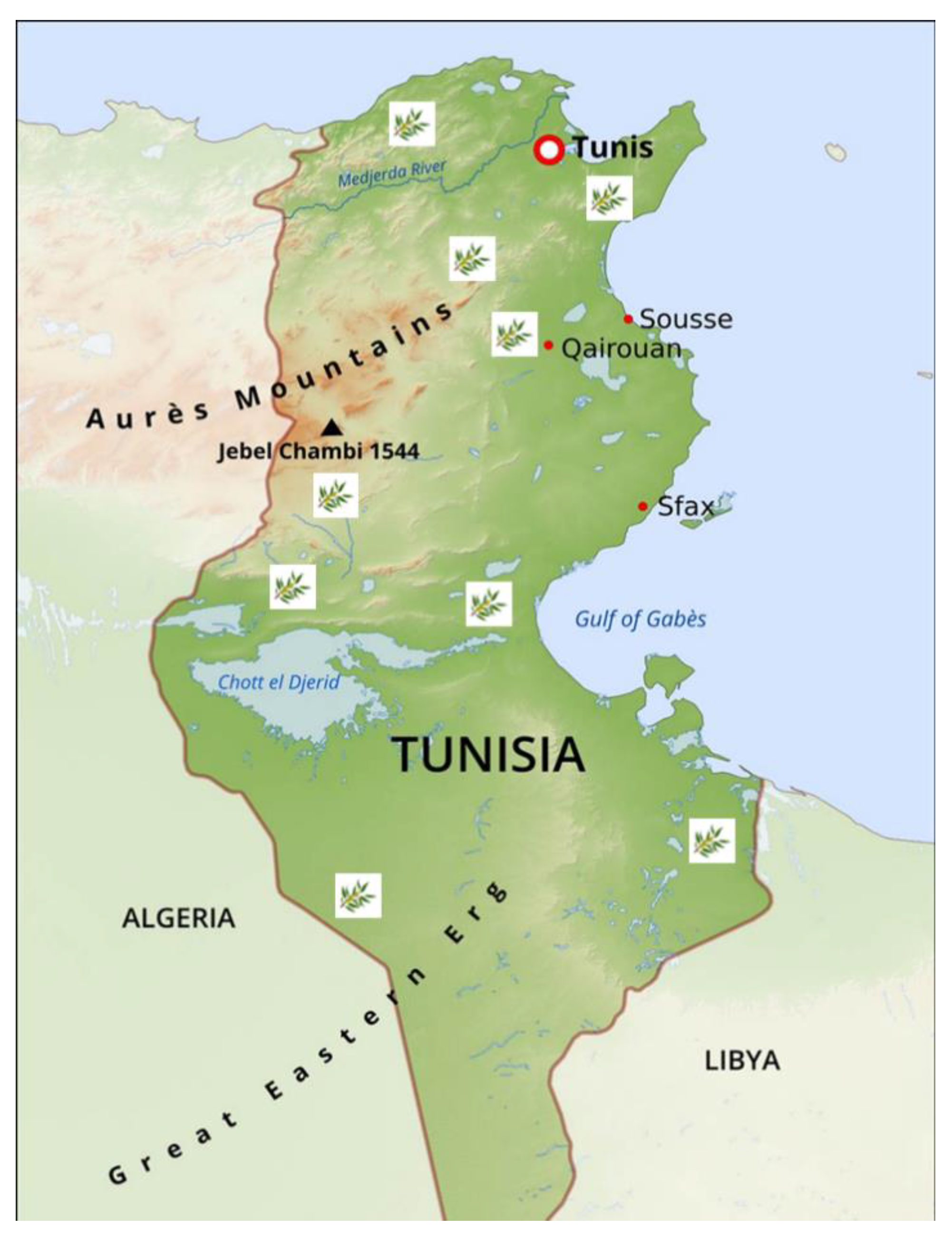

Leaf samples were collected from 28 ancient olive trees found in Tunisian archaeological sites with olive oil presses from the Punic and Roman periods (

Table 1,

Figure 1). Growth pattern, structure, and trunk diameters of the olive trees' were used as approximations of their age [

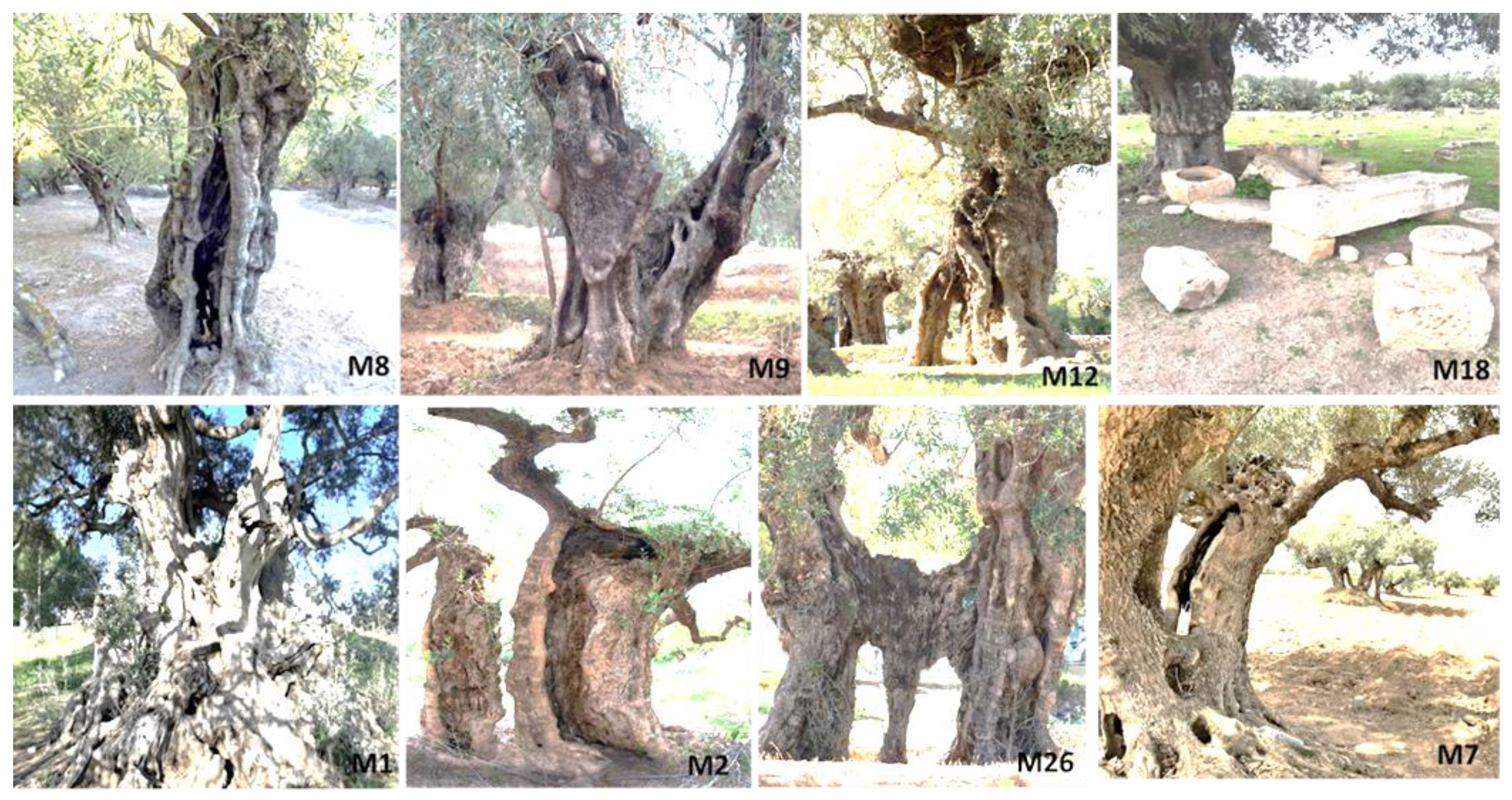

1], selecting only trees with a diameter of 3 to 8 meters (

Figure 2). The freshest leaves were collected from the branches of the year in the four cardinal points of the tree, immediately placed in ice, and brought to the laboratory for DNA extraction.

2.2. Molecular Analyses

2.2.1. DNA Extraction

Three leaves from each olive sample were freeze-dried, lyophilized, and ground to a fine powder. DNA extraction was performed using 50 mg of this material according to [

16], and DNA quantity and quality were assessed on a 1% agarose gel and using the NanoDrop TM ND 2000c (Thermo Scientific, MA, USA). The DNA was then diluted to 50 ng/µl and stored at -20°C until further use.

2.2.2. Olive Genotyping

The genetic profile of the olive samples was established using 9 highly polymorphic microsatellite markers pre-selected for efficiency, high polymorphism, and reproducibility [

17] (

Table S1). Amplifications were carried out in a final volume of 12.5 µl containing 50 ng of genomic DNA, 0.25 µl of Dream Taq buffer (10X), 0.6 µl of dNTP (2 M), 1.25 µl of a labelled primer mix (2.5 M), 0.2 µl of Dream Taq, and 7.7 µl of H2O. The thermal cycles consist of an initial denaturation at 94 °C for 15 minutes, followed by ten rounds (denaturation at 94 °C for 30 s; annealing at a temperature between 50 °C and 60 °C for 1 minute 30 s, depending on the primer; extension at 72 °C for 1 minute) and 25 cycles of (denaturation at 94°C for 30 s, annealing at 50°C for 1 minute 30 s, extension of 1 minute at 72°C). Amplifications were performed in a C1000TM thermal cycler (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA). Amplicons were separated using the ABI PRISM 3100 Avant Genetic Analyzer automatic capillary sequencer using GeneScan Liz 600 dye (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) as an internal molecular weight standard. The allele size of the amplicons was estimated using the genotyping software GeneMapper v.3.7 (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). The genetic profiles of the centenary olives were compared with those of the most commonly cultivated Tunisian olive varieties [

9] and with those of several Spanish, Italian, and Greek olive varieties available in the Global Olive Genetic Database [

18].

2.3. Statistical Analysis of the Data

The results of the molecular analysis were recorded as bands of precisely determined sizes (bp). GenAlEx v. 6.501 software [

19] was used to calculate allele frequency, number of alleles (Na), effective number of alleles (Ne), Shannon information index (I), fixation index (F), number of private alleles, marker-based relatedness (LRM), probability of identity (PI), and observed and expected heterozygosity rates (Ho, He). The software was also used to calculate the molecular variance between and within populations (AMOVA) and to perform a principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) based on inter-individual relationships using the Nei's unbiased genetic distance pairwise population matrix.

We used CERVUS version 3.0.6 [

20] to calculate the polymorphic information content (PIC) and estimate the occurrence of null alleles based on Botstein et al. (1980). Furthermore, we performed a migrant detection analysis and assignment tests using GENECLASS2 software [

21] to understand the dispersal patterns between centenary olives and olive cultivars prevalent in Tunisia. We also analyzed the dispersal patterns between the Tunisian gene pool and olive tree populations from Spain, Italy and Greece to identify the 'source' genotypes among the populations studied.

2.3.1. Cluster Analysis

Using Darwin software, version 6.0.21. [

22]; (

http://darwin.cirad.fr), the genotypes of centenary olive with the commercial olive varieties and with the Spanish, Italian, and Greek olive germplasm were hierarchically classified by applying the Neighbor-joining (NJ) method based on a dissimilarity matrix, with bootstrapping of 1000 replicates to determine the support for each node [

23].

2.3.2. Structure Analysis

The SSR profiles of the Tunisian monumental trees were compared with those of local cultivars and varieties from Spain, Italy, and Greece, using STRUCTURE 2.3.4 software [

24]. The nine microsatellite loci were first analyzed for the linkage disequilibrium (LD) test [

25,

26] to assess their association and to determine whether they met the necessary conditions for the application of the Bayesian approach. Subsequently, the Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) algorithm [

27] was used to explore the genetic structure of the populations. To determine the optimal number of subpopulations (K), ten separate iterations were performed for each value of K (from 1 to 10), using 100,000 MCMC repetitions and 100,000 burn-in periods. Harvester software was used to determine the ideal number of subpopulations as determined by the ad hoc statistical ∆K test developed by [

28] The membership coefficient (qi), which determines whether genotypes belong to the same population, was chosen as qi> 0.8; otherwise, they were considered admixed (qi< 0.8). GenALEx software was used to calculate the pairwise Fst between the groups identified by the STRUCTURE analysis.

3. Results

3.1. Genetic Diversity of Olive Genotypes

Molecular diversity analysis of Tunisian centenarian olive trees revealed 67 bands, with an average of 7.44 alleles per locus (

Table 2). The effective alleles (Ne) ranged from 2.53 for DCA15 to 6.67 for DCA09 with a mean of 4.78. The Shannon information index (I) ranged from 1.08 to 2.06 for the same markers (mean of 1.65). Polymorphism information content (PIC) was minimal for DCA15 (0.58) and reached the maximum for DCA09 (0.84). The highest Observed heterozygosity (Ho) was found for GAPU101 (mean 0.97), while the expected heterozygosity (He) was highest for DCA09 (mean 0.84). The mean inbreeding coefficient (F) was -0.049 and ranged from -0.2 (GAPU101) to 0.26 (DCA18).

The analysis of genetic diversity in the five olive populations revealed the highest number of alleles (80) for the Italian germplasm (

Table 3). The 28 centenary olives had a number of alleles (67) comparable to other groups and outnumbered the Tunisian varieties (60). The observed heterozygosity was higher than the expected heterozygosity in all the groups. Notably, the probability of identity (PI) was very low at 7.1 × 10

−11, indicating unique genotypes within the centenary germplasm Overall, the low probability of identity (PI = 10

-10) indicates that the selected markers were highly informative, enabling clear differentiation among the five Mediterranean olive populations. Pairwise LRM relatedness identified five pairs of identical instances (LRM = 0.50) between centenarian olives and local Tunisian cultivars: M25/Chemlali Tataouine, M1/Barouni, Chemlali Sfax/Zalmati, M28/Meski, and M24/JEMRI_BC. In addition, the LRM cut-off at 0.35 revealed a dense network of close relationships between several ancient genotypes with the cultivars, including M1, BAROUNI, and Besbessi; M13 and Neb Jemal Tataouine; M10 and Chemlali Jerba in Tunisian germplasm (

Table S2).

3.2. Genetic Relationships Between Olive Genotypes

The AMOVA analysis revealed that only 4% of the genetic variation exists between populations, while 96% arises from within- population’s variance (at a significance level of 0.01%). This finding suggests a limited genetic diversity between the groups and emphasizes a substantial genetic exchange among the Mediterranean

O. europaea L. cultivars. This conclusion is bolstered by the F < 0 values, which indicate high heterozygosity within the population (

Table S3).

An analysis of multi-locus genotype was conducted to individuate unique combination of allele across multiple loci, to study the dispersal patterns among the analyzed Mediterranean olive populations, and to determine the origins of genotypes [

21]. With a few exceptions, most samples could be assigned to their respective populations. The analysis revealed four potential first-generation migrants among the five olive populations (P < 0.01). Specifically, the centenary olive M10 was identified as a first-generation migrant for the local olive cultivars in Tunisia. In addition, the local Tunisian genotype Neb-Jemal-Tataouine was found to be a first-generation migrant from old olive trees. Similarly, the Spanish cultivars Arbequina and Sevillenca were recognized as potential first-generation migrants from the Italian olive tree population (

Table 4,

Table S4).

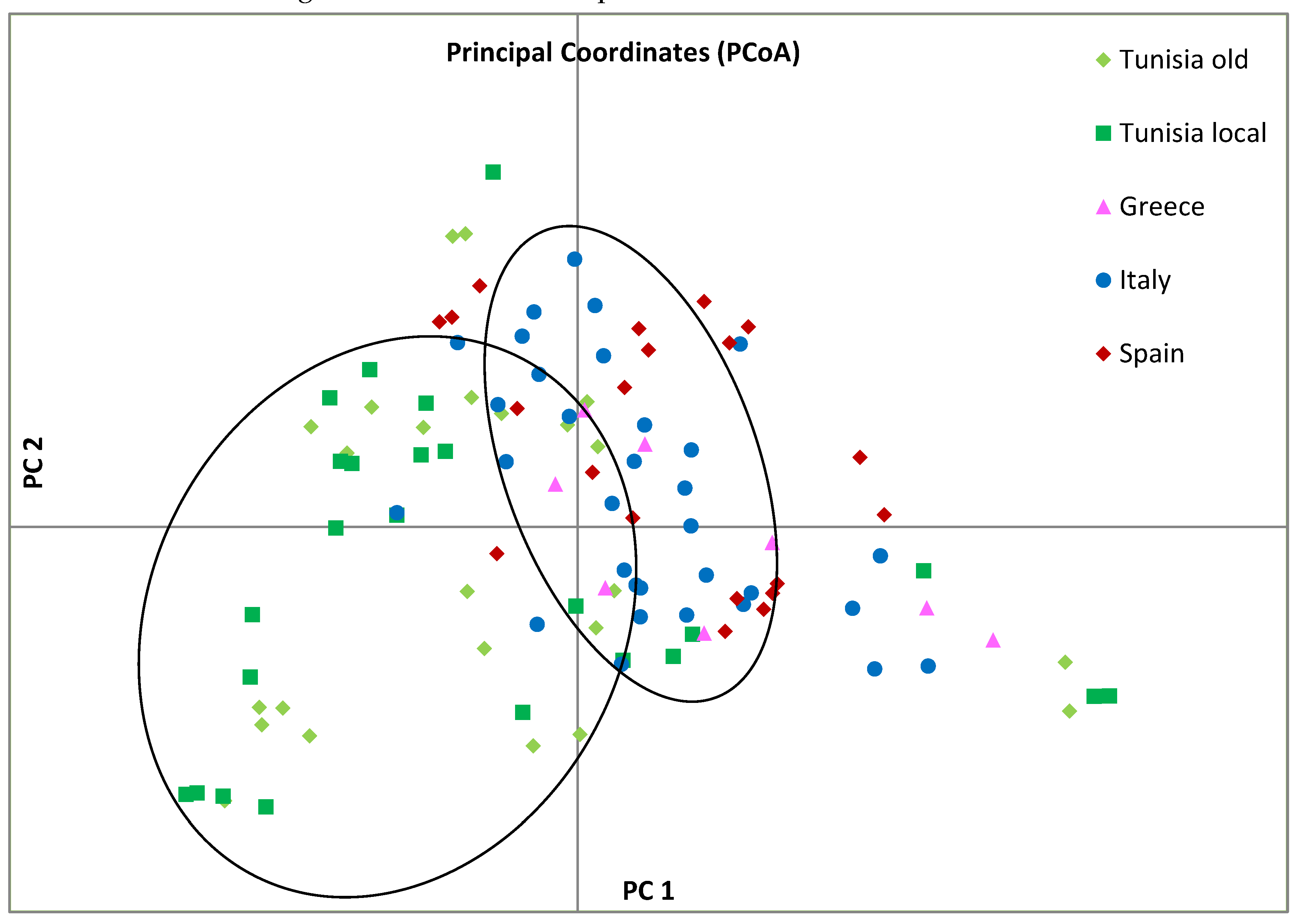

The genetic structure of the entire olive collection, including the centenarian genotypes, was analyzed using the non-parametric principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) based on Nei's unbiased genetic distance matrix. In this analysis, 21.2% of total diversity was assigned to the first two principal coordinates, PCo1 and PCo2 (

Figure 3). The plot revealed two main clusters along the PCo1 axis, one including the samples from Italy, Spain, and Greece clustered on the right side, the other collecting most Tunisian olives together with some European varieties on the left side.

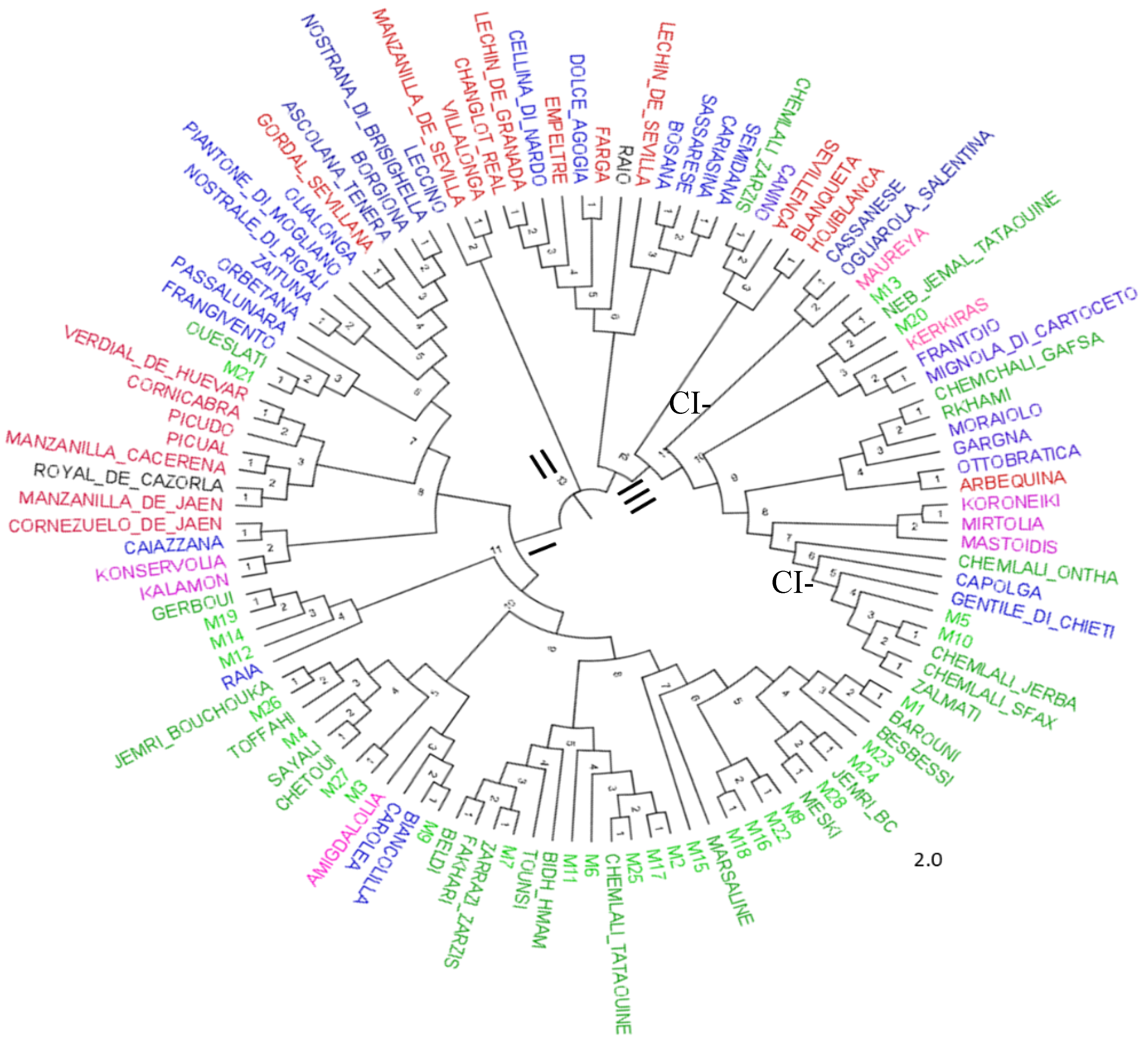

The neighbor-joining dendrogram (

Figure 4) confirmed the results of the PCoA analysis, dividing the 113 genotypes into three distinct clusters. Cluster I contained a combination of types from the five populations classified into two subclusters. The subcluster CI-1 consisted of most centenarian olive trees and Tunisian local cultivars, while the subcluster CI-2 included olive varieties from Spain, Greece and Italy. Cluster II contained the Italian variety Leccino and the Spanish varieties Manzanilla de Sevilla and Villalonga. Cluster III comprised a mixture of olive varieties from the five populations.

3.3. Genetic Structure

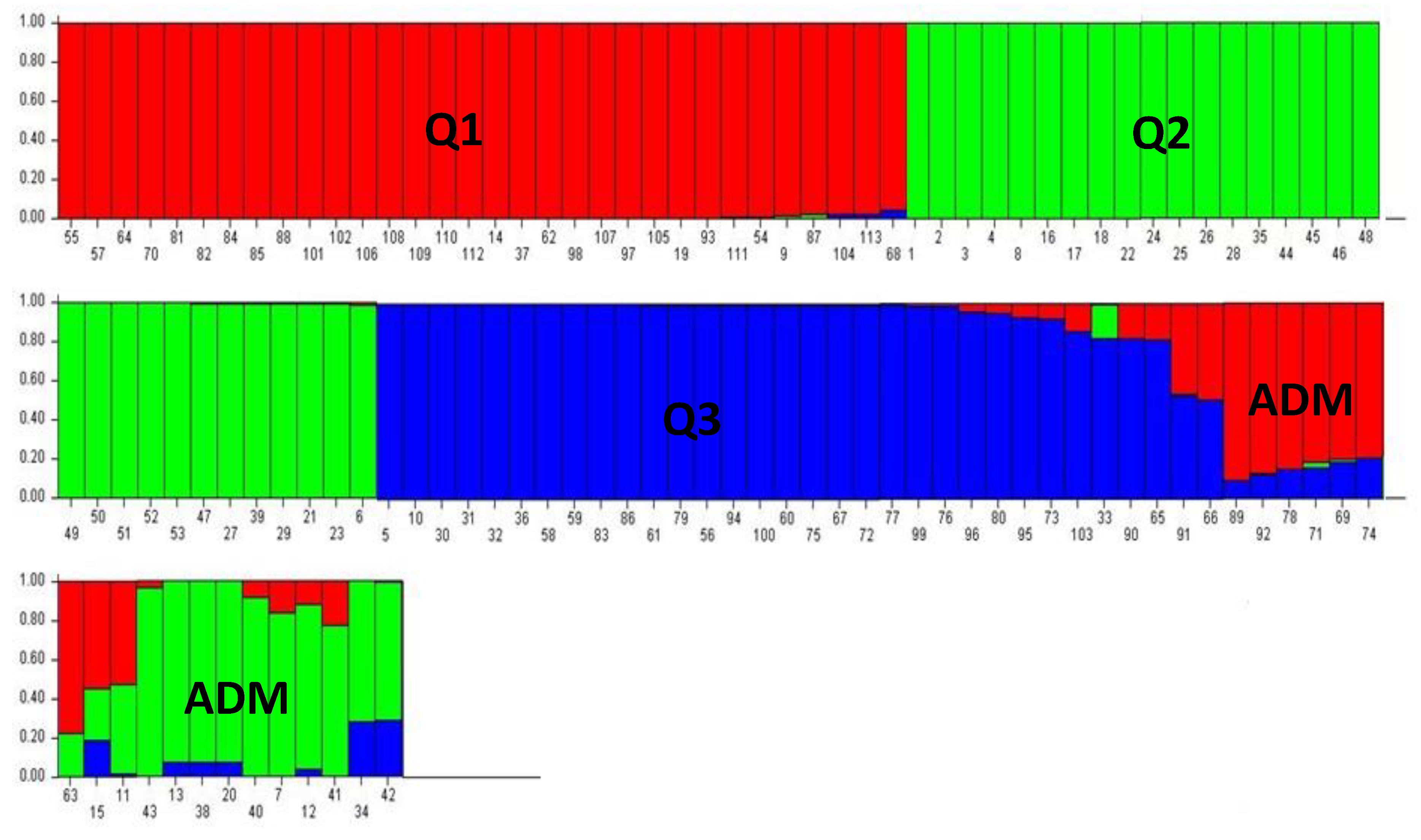

The microsatellites used revealed no significant associations in the linkage disequilibrium LD test, and thus fulfilled the requirements for the application of the Bayesian approach in the STRUCTURE analysis. Using an ad hoc measure derived from the second-order rate of variation of the likelihood function (∆K), we identified the best K = 3 (∆K = 168.97) (

Supplemental Figure S1). Three distinct subpopulations were observed, represented by different colors, in addition to a few mixed genotypes (

Figure S1). Each individual was assigned to a subpopulation if its membership exceeded 0.8. The red population (Q1) comprised mainly Spanish olive trees, some Italian and Greek varieties, and the centenarian olive trees M9 and M14. The green population (Q2) consisted mainly of the centenarian olive trees and the commercial Tunisian varieties. The third blue-striped population (Q3) consisted mainly of Italian olive trees, Greek and Spanish olive varieties, four Tunisian cultivars and the centenary trees M5 and M10. The presence of admixed genotypes (ADM), represented by two or three colors with memberships (<0.8), was also detected, which included the centenarian samples M7, M11, M12, M13, M15, and M20 and several Italian varieties.

4. Discussion

The importance of millenary olive trees as genetic resources carrying crucial traits for robustness and adaptability has only recently been recognized in the face of climate change, rising temperatures, water scarcity and the spread of new diseases such as

Xylella fastidiosa subsp.

pauca “ST53” (

Savoia et al., 2024). They attracted attention due their exceptional ability to withstand the effects of climate change [

14,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33]

The practise of olive cultivation in Tunisia has deep historical roots, dating back to the Punic, Roman and Arab-Muslim eras [

34]. The country is characterized by a rich heritage of ancient olive trees that have thrived for centuries. In this study, the genetic diversity of 28 ancient Tunisian olive trees was analyzed for the first time using SSR markers. The nine SSR markers exhibited a high level of polymorphic information content (PIC) (> 0.5), with seven of them exceeding a PIC value of 0.7 [

35], thus proving to be efficient for the study of Tunisian germplasm.

The study revealed a remarkably high genetic diversity among these ancient olive trees, which displayed a total of 67 alleles and a Shannon index (I) of 1.68, which was higher than that of Tunisian cultivars (I=1.57), confirming the preciousness of this ancient germplasm, as already noted by [

9]. It also provided valuable insights into the Italian, Spanish and Greek germplasm. In particular, the Italian varieties displayed the highest degree of polymorphism, the highest Shannon index value and the highest observed heterozygosity, which is consistent with previous studies on the Italian olive germplasm [

36,

37,

38] and Spanish olive germplasm [

39].

Several studies emphasize the great genetic diversity of ancient olive trees and their relationships with local cultivars in different Mediterranean countries such as Turkey [

40,

41] , Cyprus [

29], Lebanon [

42], Sicily [

14], Malta [

33], and Spain [

31,

43]. In all these studies, the results pointed out the peculiarity of the ancient germplasm and led to the registration of some genotypes in the International IFAPA's World Germplasm Bank of Olive Varieties, to ensure their conservation in the future. These old trees have been cultivated for a hundred years and have survived against all adversities and probably selected to enhance the flavor and aroma of the oil for the wide range of use [

13]. In Tunisia, the Romans cultivated olives in challenging environments to support nomadic communities and contributed to the development of resilient agricultural systems in arid regions by identifying robust olive cultivars [

34]. In addition, the Hellenistic era witnessed a proliferation of olive varieties due to the extensive trade that led to the spread of different olive cultivars through grafting and the exchange of knowledge about these plants [

44,

45,

46].

Among the centenarian trees, the Pairwise relatedness analysis identified samples M25, M1, M28 and M24 as synonyms of the local cultivars Chemlali Tataouine, Barouni, Meski and JEMRI_BC, respectively, revealing the antiquity of these important Tunisian varieties. The migrant detection analysis revealed that accession M10 from the old Tunisian olive population is a potential first-generation migrant of the local olive cultivars in Tunisia, and the local variety Neb-Jemal-Tataouine was identified as a first-generation migrant from ancient olive trees. In addition, the Spanish varieties Arbequina and Sevillenca were assessed as potential first-generation migrants from the Italian olive population. Overall, these results indicate genetic exchange between olive populations and the transfer of genetic material from older varieties to cultivars. The assignment test data also shows potential genetic exchange in both directions, which is consistent with previous research explaining the introgression of Western European olive cultivars from native olive trees from the East [

47]. [

14] identified ancient olive trees at archaeological sites in Agrigento (Italy) as renowned varieties such as Santagatese, Giarraffa, and Cerasuola, and [

48] pointed out the close relationships between samples of a mediaeval Maltese olive and the traditional Maltese variety Bidni.

The AMOVA analysis confirmed genetic exchange between olive populations and gene transfer from older to cultivated varieties. This indicates a complex evolutionary dynamic influenced by local adaptation and environmental factors and emphasizes the impact of both natural and human-mediated processes such as cultivation and breeding, on the genetic makeup of olives.

The genetic clustering of the analyzed olives does not correlate exactly with the geographical origin, and there is overlaps between local Tunisian cultivars, old varieties, and cultivars from Italy, Spain, and Greece. These results suggest that centenary olive trees may have simultaneously thrived across these regions, indicating a possible common ancestry of Mediterranean olive trees. These results are also confirmed by the results of the structure analysis, which revealed three clearly distinct groups and an admixed one including six centenary samples with intertwined genetic backgrounds, reflecting genetic similarities with Italian, Spanish, and Greek cultivars, as reported by several authors [

14,

17,

49]

Overall, the study allowed a genetic characterization of the endangered Tunisian centenary olive genotypes. These genotypes are currently being included in the Tunisian National GENE BANK collection, increasing the capacity of more than 200 genetic profiles as well as an olive DNA repository with more than 75 samples [

9]. These ancient genotypes, whose history spans centuries, represent a valuable source of genetic diversity that can be leveraged to combat new emergencies related to climate change and emerging diseases. The conservation of these ancient genotypes not only enriches the genetic base available for breeding programs, but also strengthens the resilience of agriculture, which is facing unprecedented pressure worldwide.

5. Conclusions

Given the unprecedented pressures facing agriculture worldwide, tapping into the genetic reservoir of old olive varieties can facilitate the development of robust varieties that require fewer resources and are more adaptable. Research into old genotypes offers the opportunity to develop new olive varieties that can effectively meet today's agricultural challenges. In this work, a first attempt was made to assess the genetic diversity of ancient olive germplasm in Tunisia, in order to take a first step towards the conservation of the genetic resources of the olive tree. The study successfully identified the genetic profile of 28 historical olive trees collected from archaeological sites, and the genetic analysis revealed a high polymorphism of this ancient patrimony and intricate relationships between Tunisian and Mediterranean olive cultivars. This information provides valuable insights into their origins, historical distribution patterns, and migration routes in the Mediterranean region and helps to protect these rare trees, some of which have a history dating back thousands of years. By preserving these ancient giants, we are protecting our natural heritage and ensuring that their ecological benefits are preserved for future generations.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org, Evanno test based on Delta K value.; Table S1: List of microsatellites used for the molecular characterization of olive samples; Table S2: List of pairwise relatedness based on LRM estimator (Lynch and Ritland, 1999); Table S3: The partitioning of genetic variation within and among groups obtained with AMOVA analysis for the 5 groups of Mediterranean olive accessions, Reference, Tunisia centennial trees, and Tunisian commercialized varieties, Greece, Italy and Spain; Table S4: The detection of first-generation migrants among olive trees from five Mediterranean populations based on the likelihood ratio (L_origin / L_max) as outlined by Paetkau et al. (1995).

Author Contributions

CRediT author statement. Conceptualization S.M., O.S.D.; Formal analysis S.M., MMM., Validation OSD, MMM; Writing -original Draft S.M. MMM; Writing - Review & Editing SM, MMM, CM, OS; Supervision OS, MMM; Funding acquisition CM

Funding

This research was supported by: RIGENERA (Approcci IntegRati per il mIglioramento GENEtico, la selezione e l’ottenimento di materiali vegetali Resistenti a Xylella fastidiosA) (CUP: H93C22000750001); Agritech National Research Center and received funding from the European Union Next- GenerationEU (PIANO NAZIONALE DI RIPRESA E RESILIENZA 6 (PNRR) – MISSIONE 4 COMPONENTE 2, INVESTIMENTO 1.4 – D.D. 1032 17/06/2022, CN00000022).

Data Availability Statement

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and are available from the corresponding author [M.M.M] on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of this study; the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; the writing of the manuscript; or the decision to publish the results.

References

- Schicchi, R.; Speciale, C.; Amato, F.; Bazan, G. The Monumental Olive Trees as Biocultural Heritage of Mediterranean Landscapes: The Case Study of Sicily. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newton, C.; Lorre, C.; Sauvage, C.; Ivorra, S.; Terral, J.F. On the origins and spread of Olea europaea L. (olive) domestication: evidence for shape variation of olive stones at Ugarit, Late Bronze Age, Syria: a window on the Mediterranean basin and on the westward diffusion of olive varieties. Veg. Hist. Archaeobotany 2014, 23, 567–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Moreno, F.; Guzmán-Álvarez, J.R.; Díez, C.M.; Rallo, P. The Origin of Spanish Durum Wheat and Olive Tree Landraces Based on Genetic Structure Analysis and Historical Records. Agronomy 2023, 13, 1608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaniewski, D.; Van Campo, E.; Boiy, T.; Terral, J.; Khadari, B.; Besnard, G. Primary domestication and early uses of the emblematic olive tree: palaeobotanical, historical and molecular evidence from the Middle East. Biol. Rev. 2012, 87, 885–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernabei, M. The age of the olive trees in the Garden of Gethsemane. J. Archaeol. Sci. 2015, 53, 43–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loussert, L.; Brousse, G. 1978. Mediterranean Agricultural Techniques of olive production. Paris, France: New home and Rose Publishing GP, 1978; pp. 44-111.

- Serge, L. Hannibal. 1995, Fayard, Paris, 391 p2. 72photos.

- Díez, C.; Trujillo, I.; Barrio, E.; Belaj, A.; Diego, B.; Rallo, L. Centennial olive trees as a reservoir of genetic diversity. Ann. Bot. 2011, 108, 797–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saddoud Debbabi, O.; Miazzi, M.M.; Elloumi, O.; Fendri, M.; Ben Amar, F.; Savoia, M.; Sion, S.; Souabni, H.; Mnasri, S.R.; Ben Abdelaali, S.; et al. Recovery, Assessment, and Molecular Characterization of Minor Olive Genotypes in Tunisia. Plants 2020, 9, 382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saddoud Debbabi, O.; Rahmani Mnasri, S.; Ben Amar, F.; Ben Naceur, M.; Montemurro, C.; Miazzi, M.M. Applications of Microsatellite Markers for the Characterization of Olive Genetic Resources of Tunisia. Genes 2021, 12, 286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debbabi, O.S.; Ben Amar, F.; Rahmani, S.M.; Taranto, F.; Montemurro, C.; Miazzi, M.M. The Status of Genetic Resources and Olive Breeding in Tunisia. Plants 2022, 11, 1759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelhamid, S.; Omri, A.; Grati-Kamoun, N.; Paolo Marra, F.; Caruso, T. Molecular characterization and genetic relationships of cultivated Tunisian olive varieties (Olea europaea L.) using SSR markers. J. N. Sci. 2017, 40, 2175–2185. [Google Scholar]

- Mnasri, S.R.; Debbabi, O.S.; Ben Amar, F.; Dellino, M.; Montemurro, C.; Miazzi, M.M. Exploring the quality and nutritional profiles of monovarietal oils from millennial olive trees in Tunisia. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2023, 249, 2807–2820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchese, A.; Bonanno, F.; Marra, F.P.; Trippa, D.A.; Zelasco, S.; Rizzo, S.; Giovino, A.; Imperiale, V.; Ioppolo, A.; Sala, G.; et al. Recovery and genotyping ancient Sicilian monumental olive trees. Front. Conserv. Sci. 2023, 4, 1206832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mnasri, R.S.; Saddoud, D.O.; Ferchichi, A. Preliminary characterization and morph-agronomic evaluation of millennium olive varieties in Tunisia. JBES. 2013, 3, 150–155. [Google Scholar]

- Spadoni, A.; Sion, S.; Gadaleta, S.; Savoia, M.A.; Piarulli, L.; Fanelli, V.; Di Rienzo, V.; Taranto, F.; Miazzi, M.M.; Montemurro, C.; Sabetta, W. A Simple and Rapid Method for Genomic DNA Extraction and Microsatellite Analysis in Tree Plants. J. Agr. Sci. Tech. 2019, 21, 1215–1226. [Google Scholar]

- di Rienzo, V.; Miazzi, M.; Fanelli, V.; Sabetta, W.; Montemurro, C. The preservation and characterization of Apulian olive germplasm biodiversity. Acta Hortic. 2018, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Öberg, L; Kullman, L. Ancient subalpine clonal spruces (Picea abies): sources of post-glacial vegetation history in the Swedish Scandes. Arctic. 2011. 64: 183-196. Olea databases (2008) http://www.oleadb.it/.

- Peakall, R.; Smouse, P.E. GenAlEx 6.5: genetic analysis in Excel. Population genetic software for teaching and research – an update. Bioinformatics 2012, 28, 2537–2539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalinowski, S.T.; Taper, M.L.; Marshall, T.C. Revising how the computer program cervus accommodates genotyping error increases success in paternity assignment. Mol. Ecol. 2007, 16, 1099–1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piry, S.; Alapetite, A.; Cornuet, J.-M.; Paetkau, D.; Baudouin, L.; Estoup, A. GENECLASS2: A Software for Genetic Assignment and First-Generation Migrant Detection. J. Hered. 2004, 95, 536–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrier, X.; Jacquemoud-Collet, J.P. 2006. DARwin Software. http://darwin.cirad.fr/darwin.

- Felsentein, J. Confidence Limits on Phylogenies: An Approach Using the Bootstraps. Evol. 1985, 39, 783–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pritchard, J.K.; Stephens, M.; Donnelly, P. Inference of Population Structure Using Multilocus Genotype Data. Genetics 2000, 155, 945–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delvin, B.; Risch, N. A comparison of linkage disequilibrium measures for fine-scale mapping. Genomics. 1995, 29:311- 22.

- Jorde, L. Linkage Disequilibrium and the Search for Complex Disease Genes. Genome Res. 2000, 10, 1435–1444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robert, C.P.; George, C. Monte Carlo Statistical Methods. Springer, 2004, 2nd edition.

- Evanno, G.; Regnaut, S.; Goudet, J. Detecting the number of clusters of individuals using the software structure: A simulation study. Mol. Ecol. 2005, 14, 2611–2620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anestiadou, K.; Nikoloudakis, N.; Hagidimitriou, M.; Katsiotis, A. Monumental olive trees of Cyprus contributed to the establishment of the contemporary olive germplasm. PLOS ONE 2017, 12, e0187697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pakyürek, M.; Koubouris, G.; Petrakis Panos, V.; Hepaksoy Serra, M.I.; Yalcinkaya, E.; Doulis, A. Cultivated and Wild Olives in Crete, Greece-Genetic Diversity and Relationships with Major Turkish Cultivars Revealed by SSR Markers. Plant Mol. Biol. Report. 2017, 35, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ninota, A.; Howadb, W.; Aranzanab, J.M.; Senarc, R.; Romeroa, A.; Mariottid, R.; Baldonid, L.; Belaje, A. Survey of over 4, 500 monumental olive trees preserved on-farm in the northeast Iberian Peninsula, their genotyping and characterization. Sci. Hortic. 2017, 231, 253–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rotondi, A.; Ganino, T.; Beghè, D.; DiVirgilio, N.; Morrone, L.; Fabbri, A.; Neri, L. Genetic and landscape characterization of ancient autochthonous olive trees in northern Italy. Plant Biosyst. 2018, 152, 1067–1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valeri, M.C.; Mifsud, D.; Sammut, C.; Pandolfi, S.; Lilli, E.; Bufacchi, M.; Stanzione, V.; Passeri, V.; Baldoni, L.; Mariotti, R.; et al. Exploring Olive Genetic Diversity in the Maltese Islands. Sustainability 2022, 14, 10684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camps-Fabrer, H. La culture de l’olivier en Afrique du Nord, Evolution et histoire. In Encyclopédie Mondial de l’Olivier; International Olive Oil Council: Madrid, Spain, 1997; pp. 30–33. [Google Scholar]

- Hearne, C.M.; Ghosh, S.; Todd, J.A. Microsatellites for link-age analysis of genetic traits. Trends Genet. 1992, 8:288-294.

- Bracci, T.; Sebastiani, L.; Busconi, M.; Fogher, C.; Belaj, A.; Trujillo, I. SSR markers reveal the uniqueness of olive cultivars from the Italian region of Liguria. Sci. Hortic. 2009, 122, 209–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolaric, S.; Vokurka, A.; Batelja Lodeta, K.; Bencic, Ð. Genotyping of Croatian Olive Germplasm with Consensus SSR Markers. Horticulturae 2024, 10, 417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sion, S.; Taranto, F.; Montemurro, C.; Mangini, G.; Camposeo, S.; Falco, V.; Gallo, A.; Mita, G.; Saddoud Debbabi, O.; Ben Amar, F.; et al. Genetic Characterization of Apulian Olive Germplasm as Potential Source in New Breeding Programs. Plants 2019, 8, 268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gago, P.; Boso, S.; Santiago, J.-L.; Martínez, M.-C. Identification and Characterization of Relict Olive Varieties (Olea europaea L.) in the Northwest of the Iberian Peninsula. Horticulturae 2024, 10, 175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoruk, B.; Taskin, V. Genetic diversity and relationships of wild and cultivated olives in Turkey. Plant Syst. Evol. 2014, 300, 1247–1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pakyürek, M.; Koubouris, G.; Petrakis Panos, V.; Hepaksoy Serra, M.I.; Yalcinkaya, E.; Doulis, A. Cultivated and Wild Olives in Crete, Greece-Genetic Diversity and Relationships with Major Turkish Cultivars Revealed by SSR Markers. Plant Mol. Biol. Report. 2017, 35: 1-11. [CrossRef]

- Chalak, L.; Haouane, H.; Essalouh, L.; Santoni, S.; Besnard, G.; Khadari, B. Extent of the genetic diversity in Lebanese olive (Olea europaea L.) trees: a mixture of an ancient germplasm with recently introduced varieties. Genet. Resour. Crop. Evol. 2014, 62, 621–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serreta-Oliván, A.; Sancho-Cohen, R.; Sánchez-Gimeno, A.C.; Martín-Ramos, P.; Cuchí Oterino, J.A.; Casanova-Gascón, J. Traditional Olive Tree Varieties in Alto Aragón (NE Spain): Molecular Characterization, Single-Varietal Oils, and Monumental Trees. Agriculture 2023, 13, 2204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanwalleghem, T.; Amate, J.I.; de Molina, M.G.; Fernández, D.S.; Gómez, J.A. Quantifying the effect of historical soil management on soil erosion rates in Mediterranean olive orchards. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2011, 142, 341–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vildan, U.; Gökçen, Y. The Historical Development and Nutritional Importance of Olive and Olive Oil Constituted an Important Part of the Mediterranean Diet, Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition 2014,54:8, 1092-1101. [CrossRef]

- Gago, P.; Boso, S.; Santiago, J.-L.; Martínez, M.-C. Identification and Characterization of Relict Olive Varieties (Olea europaea L.) in the Northwest of the Iberian Peninsula. Horticulturae 2024, 10, 175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myles, John David. "The University of Louisville Department of Architecture." Ohio Valley History, vol. 24 no. 1, 2024, p. 17-25. Project MUSE, https://muse.jhu.edu/article/925127.

- Miazzi, M.M.; Pasqualone, A.; Zammit-Mangion, M.; Savoia, M.A.; Fanelli, V.; Procino, S.; Gadaleta, S.; Aurelio, F.L.; Montemurro, C. A Glimpse into the Genetic Heritage of the Olive Tree in Malta. Agriculture 2024, 14, 495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díez, C.M.; Trujillo, I.; Nieves Martinez-Urdiroz, D.; Barranco, L.; Rallo, P.; Marfil, B.S.G. Olive domestication and diversification in the Mediterranean Basin. New Phytol. 2015, 206, 436–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Tunisia map with the sites of collection of centenary olive trees.

Figure 1.

Tunisia map with the sites of collection of centenary olive trees.

Figure 2.

Examples of millennium olive trees sampled in the archaeological sites of Kesra (M8-M9-M12), Sbeitla (M18), Haouaria (M1), Mednine (M2, M26), Zahret Medyen (M7).

Figure 2.

Examples of millennium olive trees sampled in the archaeological sites of Kesra (M8-M9-M12), Sbeitla (M18), Haouaria (M1), Mednine (M2, M26), Zahret Medyen (M7).

Figure 3.

Principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) of analyzed olive samples. Different colors represent the geographic groups of olive: Spanish: red, Italian: blue, Tunisian Millennium olives: light green, Greek: pink and Tunisian olive varieties: dark green. Principal component analysis (PCA) was performed as a non-parametric alternative to study genetic structure. The PCA plot based on the first two principal axes (PC1 and PC2) clearly separated individuals belonging to the Tunisian population from the other populations, which fell in different quadrants.

Figure 3.

Principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) of analyzed olive samples. Different colors represent the geographic groups of olive: Spanish: red, Italian: blue, Tunisian Millennium olives: light green, Greek: pink and Tunisian olive varieties: dark green. Principal component analysis (PCA) was performed as a non-parametric alternative to study genetic structure. The PCA plot based on the first two principal axes (PC1 and PC2) clearly separated individuals belonging to the Tunisian population from the other populations, which fell in different quadrants.

Figure 4.

Neighbor-joining tree of analysed olives derived from the genetic distance generated by 09 SSR markers, according to Dice’s genetic coefficient. Branches of different colors indicate the five Mediterranean populations: Spanish: red, Italian: blue, Greek: pink, Tunisian centenary trees: light green, and Tunisian olive varieties: dark green.

Figure 4.

Neighbor-joining tree of analysed olives derived from the genetic distance generated by 09 SSR markers, according to Dice’s genetic coefficient. Branches of different colors indicate the five Mediterranean populations: Spanish: red, Italian: blue, Greek: pink, Tunisian centenary trees: light green, and Tunisian olive varieties: dark green.

Figure 5.

The genetic structure of the 113 analyzed olive genotypes, identified by the STRUCTURE algorithm at K = 3. Each bar refers to an individual and is colored according to the proportion of the genome (qi) associated with each K detected. Centenary olives (1-28); autochthonous Tunisian olive varieties (29-53); Greek olive varieties (54-61); Italian olive varieties (62-93); Spanish olive varieties (94-113).

Figure 5.

The genetic structure of the 113 analyzed olive genotypes, identified by the STRUCTURE algorithm at K = 3. Each bar refers to an individual and is colored according to the proportion of the genome (qi) associated with each K detected. Centenary olives (1-28); autochthonous Tunisian olive varieties (29-53); Greek olive varieties (54-61); Italian olive varieties (62-93); Spanish olive varieties (94-113).

Table 1.

Origin and use of the millennium olives analyzed.

Table 1.

Origin and use of the millennium olives analyzed.

| Cultivar |

Locality |

Government |

Use |

| |

|

|

|

| M1 |

Haouria |

Nabeul (North) |

Table |

| M2 |

Mednine |

Mednine (Center) |

Oil |

| M3 |

Sfax |

Sfax (Center) |

Oil |

| M4 |

Zahret Medyen |

Béja (North) |

Oil and Table |

| M5 |

Gafsa |

Gafsa ((South) |

Oil and Table |

| M6 |

Gafsa |

Gafsa (South) |

Oil and Table |

| M7 |

Zarzis |

Mednine (South) |

Oil and Table |

| M8 |

Mountain of Kesra |

Siliana (Center) |

Oil |

| M9 |

Mountain of Kesra |

Siliana ((Center) |

Oil and Table |

| M10 |

Mountain of Kesra |

Siliana (Center) |

Oil |

| M11 |

Mountain of Kesra |

Siliana (Center) |

Oil |

| M12 |

Mountain of Kesra |

Siliana (Center) |

Oil and Table |

| M13 |

Testour |

Béja ((North) |

Oil and Table |

| M14 |

Testour |

Béja (North)) |

Oil and Table |

| M15 |

Testour |

Béja (North) |

Oil and Table |

| M16 |

Haouria |

Nabeul (North) |

Oil |

| M17 |

Testour |

Béja (North) |

Oil and Table |

| M18 |

Sbeitla |

Kasserine (Center) |

Oil |

| M19 |

Slimen |

Nabeul (North) |

Oil |

| M20 |

Sbeitla |

Kasserine (Center) |

Oil and Table |

| M21 |

El Alaa |

Kairouan (Center) |

Oil |

| M22 |

El Alaa |

Kairouan (Center)) |

Oil |

| M23 |

Ben Gardène |

Tataouine (South) |

Oil |

| M24 |

Ben Gardène |

Mednine (South) |

Oil |

| M25 |

Tataouine |

Tataouine (South) |

Oil |

| M26 |

Jerba |

Mednine (South) |

Oil |

| M27 |

Sbeitla |

Kasserine (Center) |

Oil and Table |

| M28 |

Zahret Medyen |

Béja (North) |

Table |

Table 2.

The global diversity indices of nine simple sequence repeat (SSR) markers detected in twenty-eight historical and twenty-five commercialized olive trees in Tunisia and sixty Mediterranean olive genotypes. Na = No. of Different Alleles, Ne = No. of Effective Alleles, I = Shannon's Information Index, Ho = Observed Heterozygosity, He = Expected Heterozygosity, Fixation index (F), Polymorphism information content (PIC).

Table 2.

The global diversity indices of nine simple sequence repeat (SSR) markers detected in twenty-eight historical and twenty-five commercialized olive trees in Tunisia and sixty Mediterranean olive genotypes. Na = No. of Different Alleles, Ne = No. of Effective Alleles, I = Shannon's Information Index, Ho = Observed Heterozygosity, He = Expected Heterozygosity, Fixation index (F), Polymorphism information content (PIC).

| Locus |

Size Range (bp) |

Na |

Ne |

I |

Ho |

He |

PIC |

F |

| DCA03 |

231–255 |

6.6 |

4.78 |

1.65 |

0.93 |

0.78 |

0.78 |

-0.18 |

| DCA05 |

194–212 |

5.8 |

2.93 |

1.3 |

0.72 |

0.64 |

0.64 |

-0.12 |

| DCA09 |

162–206 |

10.4 |

6.67 |

2.06 |

0.9 |

0.84 |

0.84 |

-0.07 |

| DCA15 |

246–270 |

4.2 |

2.53 |

1.08 |

0.56 |

0.58 |

0.58 |

0.08 |

| DCA16 |

122–186 |

9.4 |

6.42 |

1.99 |

0.9 |

0.83 |

0.83 |

-0.07 |

| DCA17 |

109–181 |

7.6 |

4.41 |

1.65 |

0.57 |

0.76 |

0.76 |

0.26 |

| DCA18 |

165–191 |

7.8 |

5.09 |

1.757 |

0.77 |

0.79 |

0.793 |

0.03 |

| GAPU71b |

121–144 |

5.6 |

4.61 |

1.59 |

0.91 |

0.78 |

0.77 |

-0.17 |

| GAPU101 |

170–218 |

7.2 |

5.6 |

1.8 |

0.97 |

0.81 |

0.81 |

-0.2 |

| Mean |

|

7.17 |

4.78 |

1.65 |

0.8 |

0.76 |

0.75 |

-0.049 |

Table 3.

The global diversity indices obtained with nine SSR markers in the five Mediterranean olive populations analyzed: number of alleles (Na), number of effective alleles (Ne), Shannon’s information index (I), observed heterozygosity (Ho), expected heterozygosity (He), fixation index (F).

Table 3.

The global diversity indices obtained with nine SSR markers in the five Mediterranean olive populations analyzed: number of alleles (Na), number of effective alleles (Ne), Shannon’s information index (I), observed heterozygosity (Ho), expected heterozygosity (He), fixation index (F).

| Populations |

|

Na |

Ne |

I |

Ho |

He |

PIC |

PI |

F |

| Tunisia centennial olive trees |

Total |

67 |

45.9 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

Mean |

7.44 |

5.1 |

1.68 |

0.68 |

0.76 |

0.75 |

7.1E-11

|

0.12 |

| Tunisian commercial varieties |

Total |

60 |

39.6 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

Mean |

6.66 |

4.4 |

1.57 |

0.7 |

0.73 |

0.73 |

4.9E-10

|

0.07 |

| Greek varieties |

Total |

55 |

41.0 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

Mean |

6.11 |

4.55 |

1.60 |

0.88 |

0.76 |

0.75 |

2.4E-10

|

-0.16 |

| Italian varieties |

Total |

80 |

48.8 |

|

|

|

|

4.1E-10

|

|

| |

Mean |

8.88 |

5.42 |

1.83 |

0.85 |

0.8 |

0.79 |

1.0E-11

|

-0.06 |

| Spanish varieties |

Total |

61 |

39.92 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

Mean |

6.77 |

4.43 |

1.58 |

0.91 |

0.75 |

0.75 |

4.1E-10

|

-0.215 |

Table 4.

Assignment of 113 Mediterranean olive cultivars to five predefined populations using the algorithm of GeneClass2.

Table 4.

Assignment of 113 Mediterranean olive cultivars to five predefined populations using the algorithm of GeneClass2.

| Individuals |

Tunisian centennial olives |

Tunisian commercial varieties |

Greek varieties |

Italian varieties |

Spanish varieties |

| Number of individuals |

28 |

25 |

8 |

32 |

20 |

| % assigned to the predefined population |

89 |

100 |

75 |

96,8 |

85 |

| % assigned to the predefined population and another population |

96 |

100 |

100 |

87,1 |

100 |

| % not assigned to the predefined population but to another population |

10.7 |

0 |

25 |

3.1 |

15 |

| % not assigned to neither the predefined population nor another population |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).