1. Introduction

Domestic violence refers to intentional harm caused by individuals who are biologically or legally related, or who function as a family unit. This includes instances such as a husband abusing his wife, a wife abusing her husband, one or both parents abusing their children, children abusing their parents, siblings abusing each other, or abuse between mothers-in-law and daughters-in-law. Domestic violence refers to the intentional infliction of injury by individuals who are connected via blood or marriage, or who function as a family unit. This may include instances such as a husband beating his wife, a woman abusing her husband, or even concubines harming each other [

1]. The perpetrator is the dominant party who employs physical force against the victim who embodies the subordinate party. Domestic violence is a significantly underreported offense committed against both women and men worldwide. This is mostly due to the prevailing belief that domestic violence is permissible and warranted, sometimes being categorized as mere "family issues". Amidst the Corona crisis and the lockdown, domestic violence has intensified. While this issue has existed since ancient times, it is inherent to human societies and their interconnectedness with the surrounding environment. However, the manifestations and variations of domestic violence have evolved over time. Due to the impact of contemporary society, domestic violence has emerged as the predominant form of interpersonal violence, prevalent across all civilizations universally [

2]. Extensive research has consistently demonstrated that domestic violence primarily targets wives, followed by sons, daughters, and the elderly. Moreover, a comprehensive study conducted by the United Nations Women’s Organization has revealed that approximately 99% of domestic violence cases are perpetrated by men. These findings are supported by global estimates. According to the data, 35% of women globally have encountered instances of domestic abuse at some stage in their lifetimes. Domestic violence encompasses physical, psychological, sexual, and economic forms of abuse, with the specific nature of the violence being subject to variation [

3].

An investigation was conducted in several Indian states and towns to examine the overall patterns of domestic crimes against women in India. The research identified a potential correlation between development and various forms of domestic abuse by the application of Multivariate linear regression [

4]. New research conducted in Greece aims to identify the primary determinants of domestic violence among pregnant women. A total of 546 women took part in the Abuse Assessment Screen (AAS) questionnaire while maintaining anonymity. The research revealed that 6% of the female participants encountered domestic violence while pregnant, with 3.4% of them reporting abuse from the beginning of their pregnancy, mostly perpetrated by their spouse or partner. According to the research, there is a correlation between country, social class, and education level and an increased likelihood of experiencing maltreatment during pregnancy [

5]. Separate research was conducted with the objective of creating and verifying a tool that assesses the susceptibility of women to domestic violence inside the household, using indications of gender subordination. The research devised a 61-phrase tool to assess gender subordination inside the household. Ten judges reviewed and verified a total of 34 sentences. The authorized edition was distributed to 321 health service recipients in So José dos Pinhais (Estado de Paraná, Brazil), along with the validated Portuguese version of the Abuse Assessment Screen (AAS) to categorize the sample group. The "YES" group comprised women who had experienced violence, while the "NO" group comprised women who had not experienced violence [

6]. The Human Rights Commission released a statistic indicating a 45% surge in rates of domestic violence. Consequently, experts and family associations have called for a nationwide campaign to heighten awareness about this matter. They have also urged the Shura Council to address and combat domestic violence, with the aim of safeguarding women and children from all forms of abuse. Consequently, the authorities in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia have sanctioned several laws and regulations, in addition to establishing committees to monitor instances of domestic violence and raise awareness about its perils. Upon doing a basic search on the Human Rights Commission’s website, we discovered several articles and reports pertaining to different manifestations of domestic abuse. This prompted us to ponder several inquiries:

Why hasn’t a comprehensive inventory of the underlying reasons of the increase in domestic violence cases and its many manifestations been created?

Are the competent authorities not aware that identifying the underlying cause of violence would allow them to prescribe appropriate therapy, rather than resorting to the creation of new rules and regulations that may inadvertently lead to the emergence of new kinds of domestic violence?

The user’s text is a bullet point.Has there been no credible statistical research conducted to address and reduce domestic violence in order to develop effective models and implement drastic solutions? This issue was confirmed by Dr. Majed Al-Essa, the Deputy Executive Director of the National Family Safety Program. He stated that conducting research and scientific studies on violence against children in Saudi Arabia has been challenging due to limited resources and manpower. This hinders the ability to establish broad conclusions based on their findings and prevents their application in the necessary manner for the development of preventative strategies.

With these questions as a basis, we present to you this study, which aims to provide complete and statistical answers to these inquiries.

A comprehensive exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was conducted on all variables specified in the questionnaire. The study included the classification of questionnaire questions into several components. The variables impacting domestic violence were selected based on the similarity of the findings.

The EFA methodology is widely recognized as the most common method for analyzing several variables simultaneously. The objective is to estimate the original variables in a data set by using linear combinations of a smaller set of latent variables, referred to as factors. This task must be executed in a manner that ensures a precise fit of the covariance matrix (or correlation matrix) of the original variables. The factor analysis model incorporates other characteristics, such as the individual variances of the error components [

7]. During a factor analytic technique, the process of identifying the number of factors to extract entails selecting the factors that explain the highest amount of variation in the data.

The following elements are used as criteria for calculating the quantity:

1. Kaiser’s criteria, first established by Guttman and then modified by Kaiser, defines eigenvalues larger than one as indicative of shared components.

2. When doing a factor analysis, the process of selecting the number of components to extract involves retaining only those factors that explain a specific proportion of the variation, such as 5% or 10%.

3. Determining the optimal number of components to extract in a factor analysis. The percentage of variance accounted for by Extracting Factors Analysis (EFA) is used to deconstruct an adjusted correlation matrix. The EFA procedure standardizes variables by setting the mean to 0 and the standard deviation to 1. Additionally, the diagonals are adjusted for unique factors using the formula 1-u. The variance explained is equivalent to the trace of the matrix, which is the total of the corrected diagonal elements. The EFA Model is represented by the equation Y = Xα + E, where Y is a matrix of observable variables. The matrix X consists of shared components. A α refers to a matrix of weights, also known as factor loadings. The matrix E consists of unique components and variations in error.

4. Eigenvalues indicate the amount of variation that is explained by each component. The eigenvectors are the weights that may be used to calculate factor scores. Factor scores are often computed by taking the average or total of the observed variables that have a significant influence on the factor.

Communality refers to the proportion of variation in observable variables that may be attributed to a common cause. A high communality value indicates that an underlying concept has a substantial impact.

The interpretability rotational factor pattern has a simple structure, with no cross loadings [

8].

The objective of this study is to examine instances of domestic violence against Saudi nationals, with a focus on identifying the primary variables that contribute to such violence in Saudi Arabia. The results will provide guidance for suggestions targeted at reducing violence and dealing with the related problems.

2. Material and Methods

In this section, we will demonstrate the application of factor analysis to the data on domestic violence in Saudi Arabia, using the SPSS program.

The essential data is derived from a questionnaire that was administered to 550 Saudi residents residing in different locations of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia between March 2023 and September 2023. The dataset consists of 12 variables.

V1: Inadequate upbringing. Version 2: Lack of familial communication. V3: Economic challenges, Version 4: Ethical and behavioral abnormalities. Topic: Unemployment. V6: Substance misuse and addiction, V7: The emotions of jealousy and envy. V8: Absence of confidentiality. V9: Poor etiquette, V10: Vandalism. Topic: The repercussions of divorce. Topic: V12: Bullying Exploratory Factor Analysis is a multi-step procedure that may be divided into three basic steps:

Evaluating the suitability of the data for factor analysis.

Utilizing an extraction technique to get the original solution.

Utilizing a rotating strategy to get the ultimate result.

This article provides a comprehensive explanation of the specific processes and how they were carried out on the study data using the statistical program SPSS. SPSS is generally acknowledged as a key instrument in both psychological research and social science applications.

3. Results and Discussion

The results were examined by exploratory factor analysis (EFA), including all the variables specified in the questionnaire.

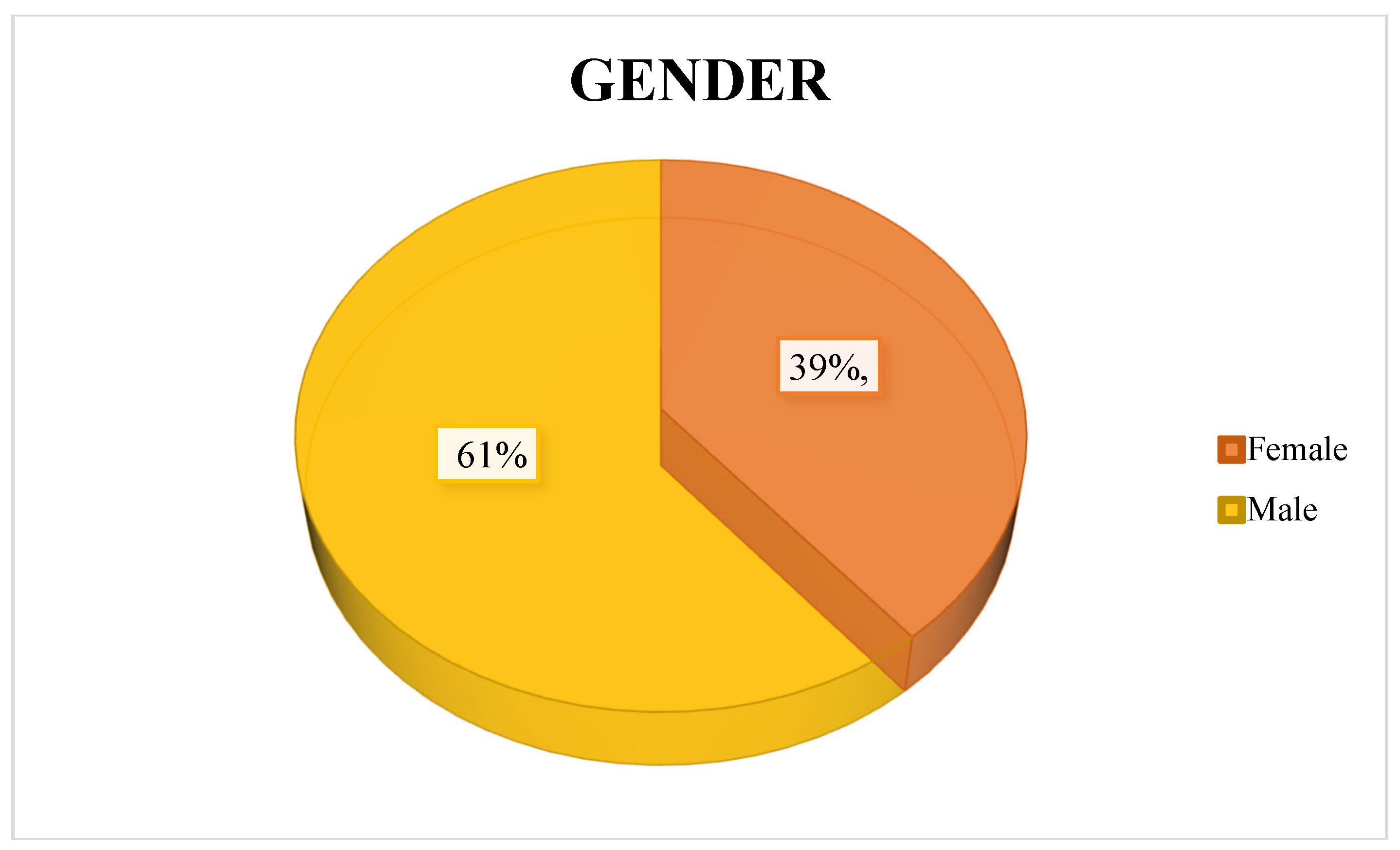

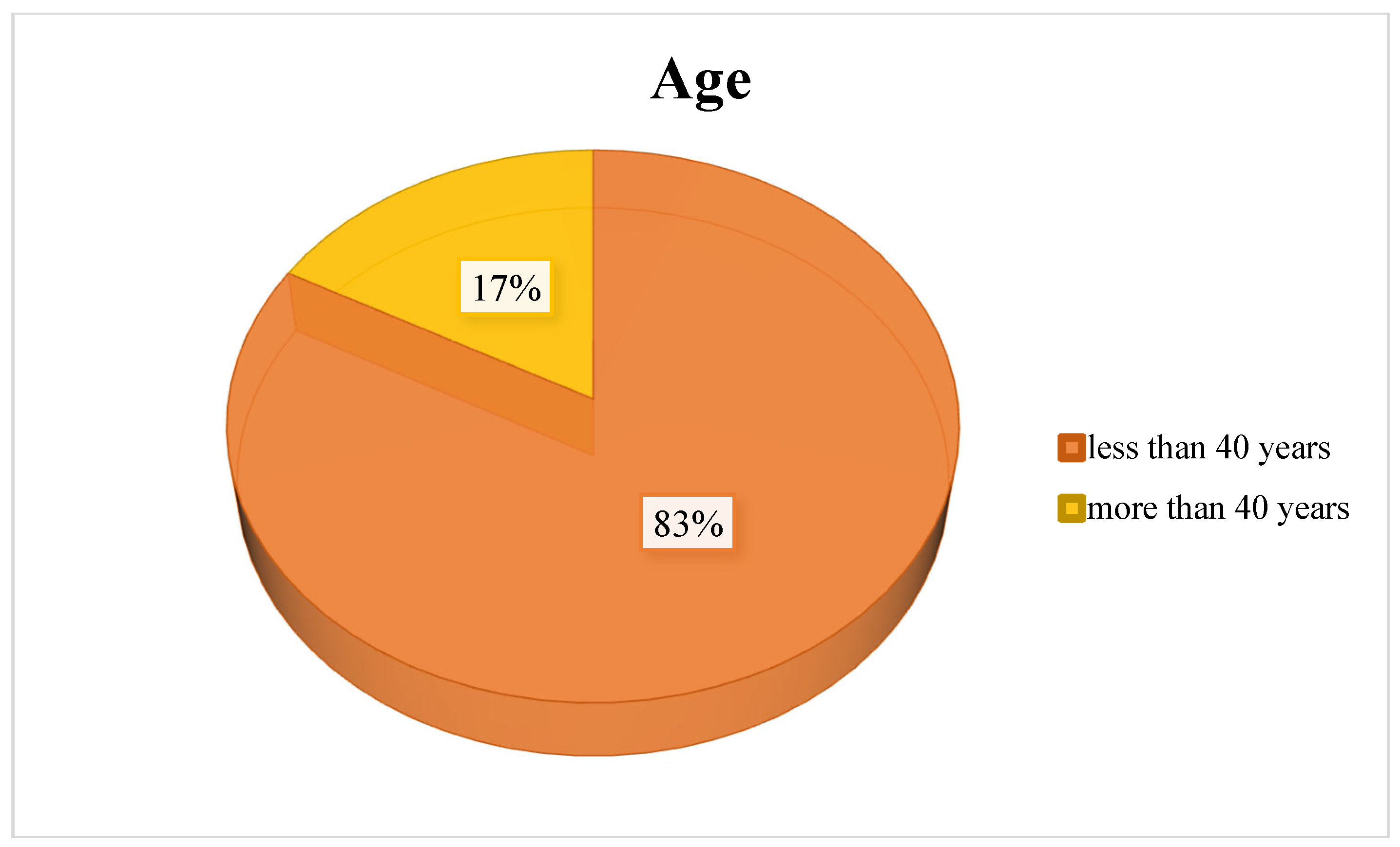

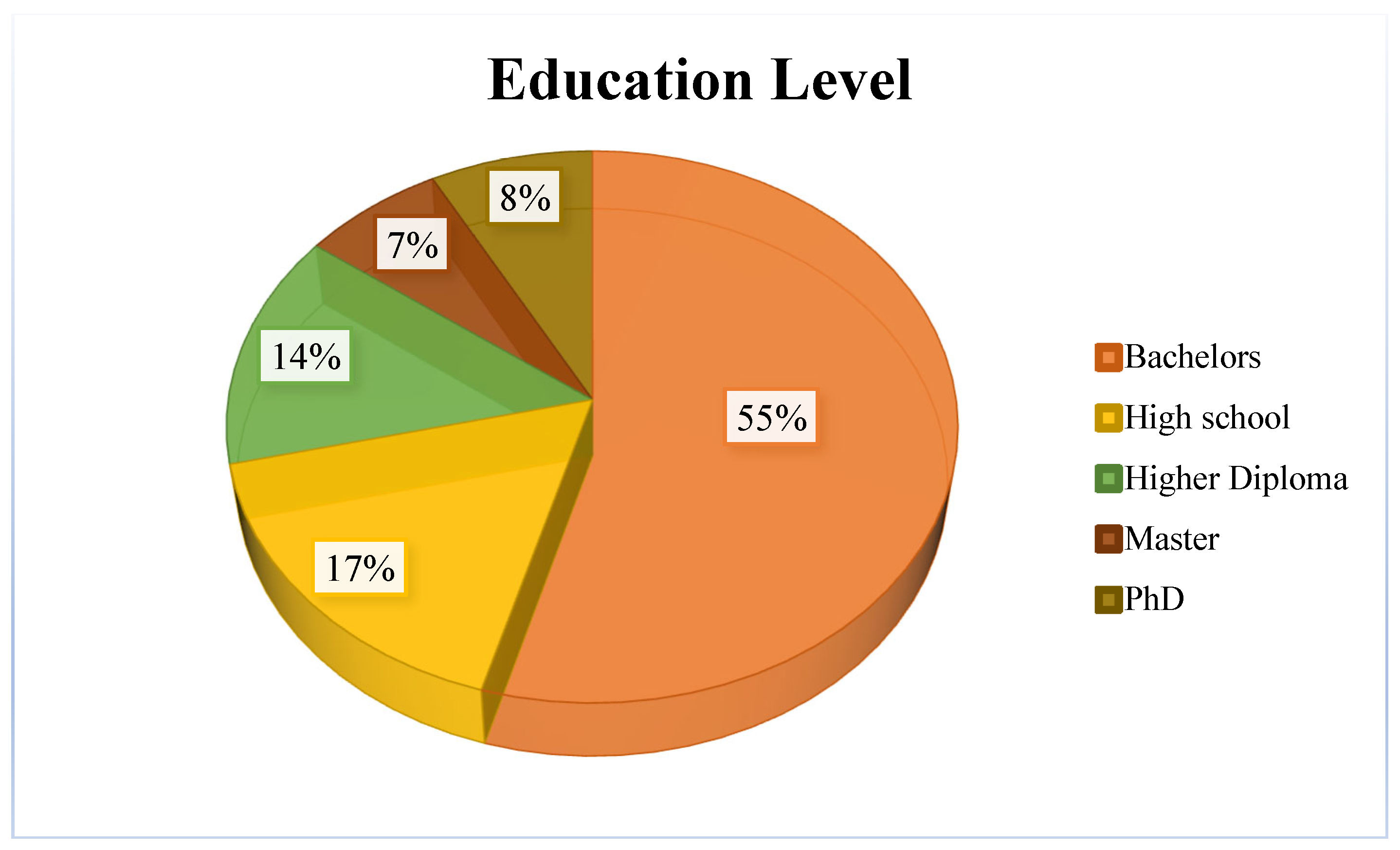

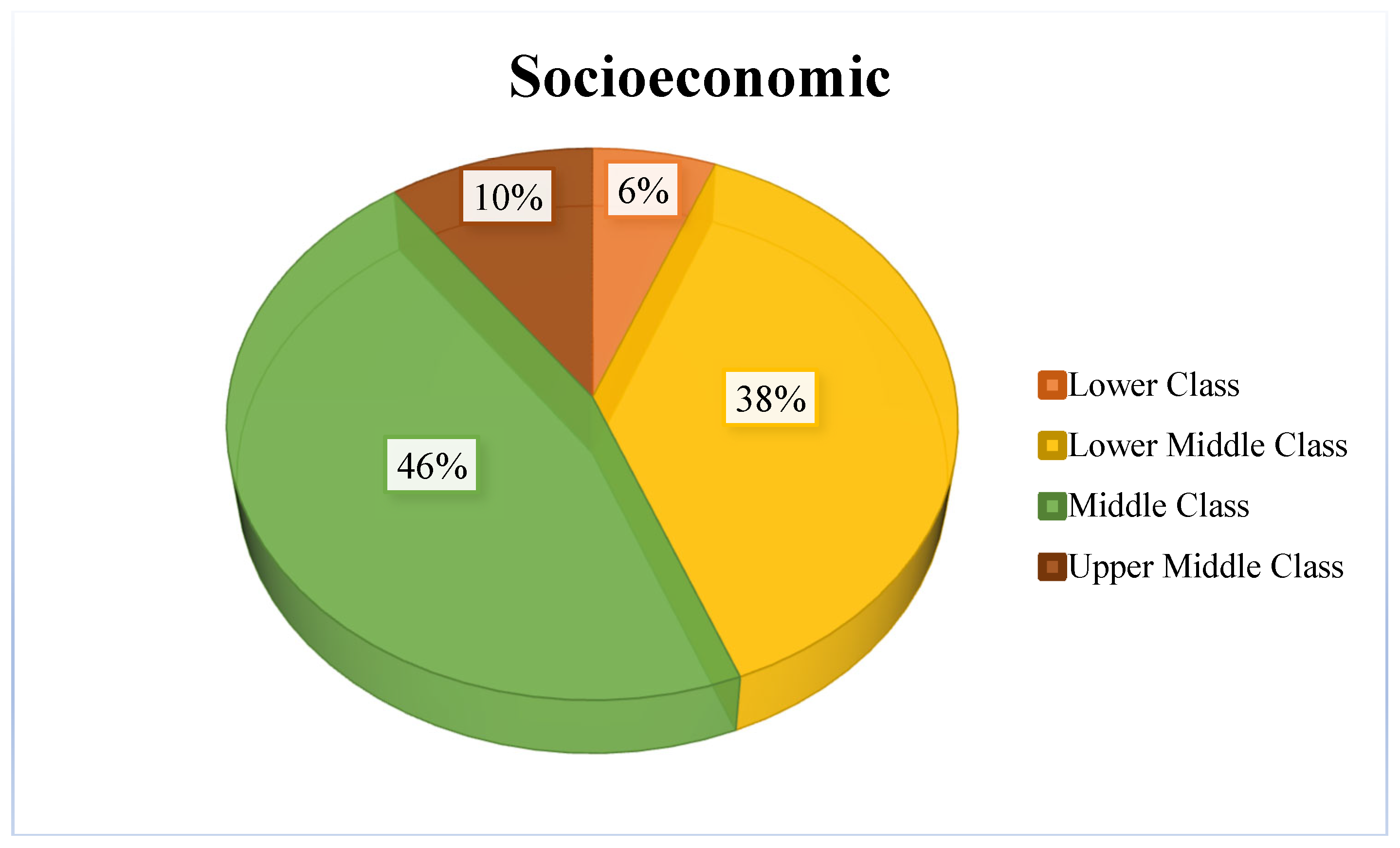

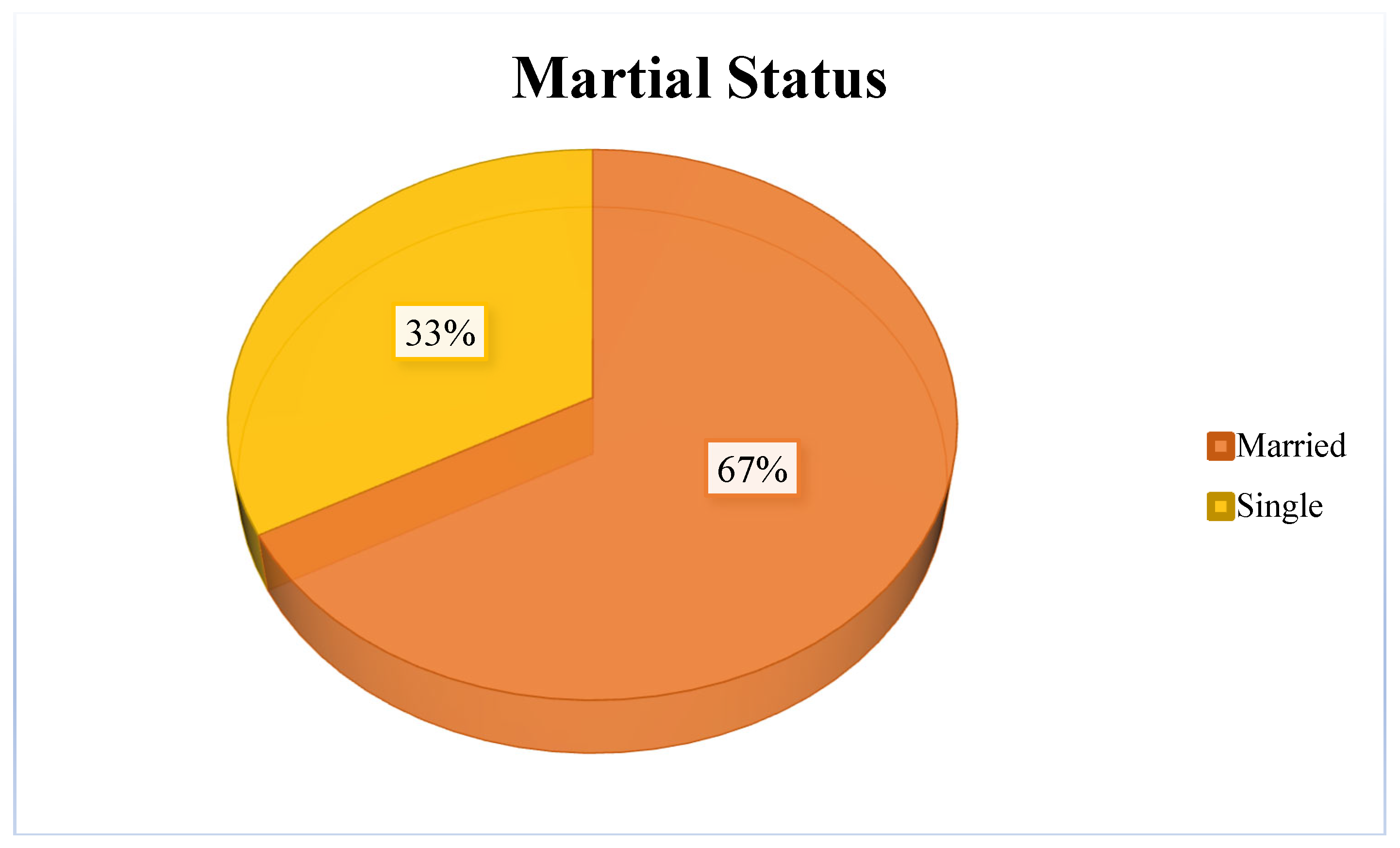

Table 1 displays demographic data including age, gender, educational level, socioeconomic status, and marital status. As the questioner is in Arabic, there is no need for translation. Quantitative analysis included doing descriptive statistics to determine the frequency and proportion of demographic data. The study sample consisted of 337 male respondents, accounting for 61% of the total, and 213 female respondents, accounting for 39%.

It is evident that 83% of the participants are under the age of 40. A significant proportion was attributed to the educational level. 55% of the target population have obtained a bachelor’s degree, while just 7% of the participants have achieved a master’s degree. The majority of participants in the research belong to the Middle Class in terms of their Socioeconomic status, comprising 84% of the total. EFA was conducted using principal component analysis with varimax rotation. The loading threshold was established at 0.50. Refer to

Figure 1,

Figure 2,

Figure 3,

Figure 4 and

Figure 5.

3.1. Assessing the Appropriateness of the Data for Factor Analysis

The Anti-Image Matrices reveals a strong correlation value over 0.7 for all items, indicating that data with Measures of Sampling Adequacy (MSA) are suitable for factor analysis, as seen in

Table 2.

We use the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) Measure of Sampling Adequacy and Bartlett’s Test for Sphericity to evaluate the suitability of the data for Factor Analysis (FA). The KMO (Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin) test is used to assess the suitability of data for factor analysis (FA), with a higher KMO value suggesting a more robust link between variables. A KMO rating greater than 0.60 indicates suitability. Conversely, Bartlett’s test is used to evaluate the hypothesis that statistical techniques can effectively represent the variations within the population.

It is seen in

Table 3, that KMO was 0.86, that mean the variables in the dataset exhibit sufficient intercorrelation to allow for meaningful factor analysis without the presence of severe multicollinearity issues. Furthermore, Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity were significant, ꭓ2 (n = 524) = 1817.327 and P < 0.05 which provides a measure of the statistical probability that the correlation matrix has significant correlations among some of its components.

3.2. Employing an Extraction Method

This section will go into Principal Components Analysis (PCA). Principal Component Analysis (PCA) involves the transformation of variables into components that effectively represent the variation inherent in the original data. An often used approach in Principal Component Analysis (PCA) is to calculate component weights that maximize variance. This iterative procedure continues until there is no significant variation remaining.

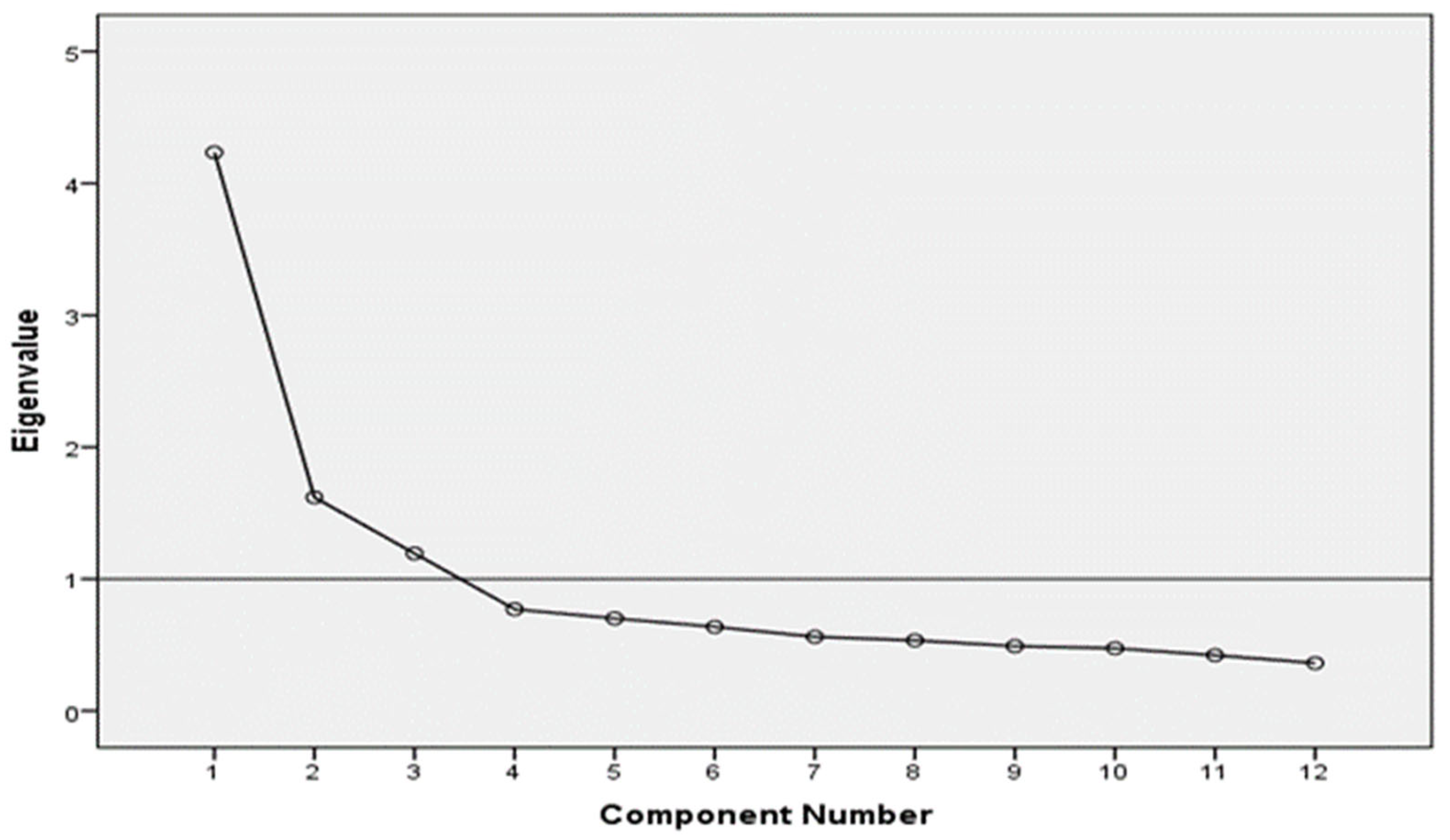

According to

Table 4, the factor solution resulted in three components that explained 58.728% of the variance in the data. The study yielded a three-factor solution, each with Eigen values greater than one, as seen in

Figure 1. This solution accounts for 58.728% of the total variance, whereas the first iteration accounted for 48.750%. Therefore, the six items were excluded from further research. The authors conducted a repeated exploratory factor analysis (EFA) excluding these components.

3.3. Scree Plot

The Scree test is a technique introduced by Cattell (1966). This test involves plotting eigenvalues against their respective ordinal numbers. The goal is to determine the point at which the plotted line changes direction or gradient. The break point refers to the specific point on a plot when the orientation of the points changes [

9].

The number of eigenvalues above the break point indicates the number of components, while the eigenvalues below the break point signify the error variance [

10].

The numerical values for the three extracted factors can be observed above the point where the carve begins to decelerate, as illustrated in

Figure 6.

3.4. Factor Loadings

Factor coefficients are often known as factor loadings, and in the context of Principal Components Analysis (PCA), they are sometimes referred to as component loadings. These loadings indicate the correlation coefficients between factors and variables, similar to Pearson’s r. The component loading refers to the proportion of variability in the variable that is accounted for by the factor [

11]. The loadings of the components are shown in

Table 5

The findings of this recent analysis validated the three variables revealed during the exploratory factor analysis, which were consistent with the theoretical premise in this study. According to the rotated component matrix in

Table 5 and

Table 6 out of the 20 items were excluded because they either had cross loading in another component or had a loading value less than 0.50. Three components were identified upon convergence of the rotation in their iterations. All objects have been successfully imported into the component with a threshold of 0.5. Component 1 encompasses several factors such as moral and behavioral abnormalities, improper upbringing, lack of family communication, alcohol and drug misuse, and poor manners. These factors all contribute to the absence of family cohesiveness. Component 2 encompasses many elements (Jealousy and envy, Lack of privacy, Bullying, Hooliganism, and Consequences of divorce) that exemplify the propagation of detrimental characteristics. Component 3 encompasses issues related to economic concerns and unemployment, specifically relating to a financial crisis.

Variable communality is calculated by adding up the squared factor loadings that are linked to a certain variable. This statement refers to the amount of variability in a variable that can be accounted for by the shared components that have been identified and extracted. A higher communality indicates that the extracted variables explain a greater share of the variation in the variable. Therefore, a high variable communality indicates that the individual variables are accurately represented by the extracted components [

12].

Table 6 presented the amount of variance in each dimentions is given by the communalities, were over 0.50. Two items had communalities slightly less than 0.50 but they did not affect all the factors’ structure and they loaded well with other factors.

4. Discussion and Limitations

This study sought to determine the variables that influence and drive the occurrence of domestic violence in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia via the use of exploratory factor analysis. The study identified three primary catalysts for marital violence: lack of familial unity, encouragement of detrimental characteristics, and economic turmoil. This section will examine the explanations, consequences, restrictions, and suggestions derived from these discoveries.

The primary component, the lack of familial cohesiveness, encompasses characteristics such as moral and behavioral abnormalities, improper upbringing, absence of familial conversation, alcohol and substance misuse, and poor etiquette. This component signifies the absence of concord and communication among members of a family, which may result in disputes and violence. The study proposes that family cohesiveness may be strengthened via the promotion of good values, the provision of appropriate education and guidance, the cultivation of mutual respect and understanding, and the use of professional assistance when necessary. This aligns with a research conducted by [

13] which discovered a negative correlation between family cohesiveness and domestic violence among Saudi women.

The second element, the encouragement of negative qualities, encompasses factors such as jealously, envy, loss of privacy, bullying, hooliganism, and the repercussions of divorce. This element represents the impact of individual and societal conditions that might provoke aggressive behaviors within a family unit. The study proposes that negative characteristics may be diminished via the enhancement of self-esteem and confidence, the observance of personal boundaries and rights, the prevention and resolution of bullying and harassment, and the provision of assistance to families experiencing divorce. According to a research conducted by [

14], jealously and envy were identified as the primary motivations for domestic violence among Saudi males.

The third component, the financial crisis, encompasses characteristics such as economic downturns and joblessness. This element represents the influence of economic adversity and volatility on the welfare and steadiness of families. The article proposes that the financial crisis may be mitigated by the implementation of measures such as increasing work prospects, offering financial aid and counseling, and effectively managing family budgets and spending. This assertion is substantiated by research [

15], which found that economic difficulties were a notable risk factor for domestic violence among Saudi women.

The results of this work align with prior research that has revealed comparable variables that influence domestic violence in many settings [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6]. Moreover, this research enhances the existing body of knowledge by presenting actual data from a particular cultural milieu that has received less scholarly attention. The report provides a thorough and quantitative method to determine the key elements that drive domestic violence in Saudi Arabia.

This work is limited by the use of a convenience sample, which may not accurately reflect the whole population of Saudi Arabia. The article also depends on self-reported data, which might be influenced by social desirability bias or memory bias. Furthermore, the research does not analyze the cause-and-effect connections between the parameters and domestic violence, nor does it investigate the moderating or mediating impacts of other variables.

5. Conclusions and Recommendations

This report conducted a statistical analysis of the variables that influence and drive the occurrence of domestic violence in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. The article used exploratory factor analysis to identify three primary variables that contribute to domestic violence: lack of family cohesiveness, promotion of negative characteristics, and financial stress. The report also examined the ramifications of these results for policymakers, scholars, and society. The study proposed that more endeavors are required to enhance consciousness about the origins and repercussions of domestic violence, to provide assistance and safeguard for the victims, and to tackle the fundamental social and economic factors that contribute to this issue. In addition, the publication identified several constraints of the study and proposed potential avenues for further research. This work enhances the current body of knowledge on domestic violence by presenting empirical data from a particular cultural setting that has received less attention in previous research. The report provides a thorough and quantitative method to determine the key elements that drive domestic violence in Saudi Arabia. The report aims to stimulate more investigation into this subject and to provide insights for successful interventions aimed at preventing and mitigating domestic violence in Saudi Arabia and other countries. Future study should consider using a more extensive and heterogeneous sample to include the unique characteristics of different locations, genders, ages, and backgrounds in Saudi Arabia. Subsequent investigations may use longitudinal or experimental methodologies to examine the causal impacts of the determinants on domestic violence or investigate the underlying processes by which they function. In addition, future studies may include other variables that might potentially impact domestic violence, such as cultural norms, religious convictions, legal frameworks, or media exposure.

Funding

The Deanship of Scientific study at the University of Tabuk provided funding for this study, under project number (0219-1443-S).

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their gratitude to the Deanship of Scientific Research at the University of Tabuk for providing funding for this study under research number (0219-1443-S).

Data Availability: The data that substantiate the conclusions of this research may be obtained by contacting the relevant author upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors assert that there is no conflict of interest.

References

- McNeely, R. L.; Cook, P. W.; Torres, J. B. Is domestic violence a gender issue, or a human issue? J. Hum. Behav. Soc. Environ. 2001, 4, 227–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, J.T. Monsters and victims: Male felons’ accounts of intimate partner violence. J. Soc. Pers. Relatsh. 2004, 21, 555–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flury, M.; Nyberg, E.; Riecher-Rössler, A. Domestic violence against women: Definitions, epidemiology, risk factors and consequences. Swiss Med Wkly. 2010, 140, w13099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hackett, M. Domestic Violence against Women: Statistical Analysis of Crimes across India. J. Comp. Fam. Stud. 2011, 42, 267–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antoniou, E.; Iatrakis, G. Domestic violence during pregnancy in Greece. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 4222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macedo Piosiadlo, L.C.; Godoy Serpa da Fonseca, R.M. Gender subordination in the vulnerability of women to domestic violence. Investig. Y Educ. En Enfermería 2016, 34, 261–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pison, G.; Rousseeuw, P. J.; Filzmoser, P.; Croux, C. Robust factor analysis. J. Multivar. Anal. 2003, 84, 145–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suhr, D. D. (2006). Exploratory or confirmatory factor analysis?

- Velicer, W.F.; Eaton, C.A.; Fava, J.L. Construct explication through factor or component analysis. A review and evaluation of alternative procedures for determining the number of factors or components. In Problems and Solutions in Human Assessment: Honoring Douglas N. Jackson at Seventy, 2nd ed.; Goffin, R., Helmes, E., Eds.; Springer Science & Business Media: Totowa, NJ, USA, 2000; pp. 41–71. [Google Scholar]

- Ivancevic, T. T., Jovanovic, B., Djukic, S., Djukic, M., & Markovic, S. (2008). Complex sports biodynamics: With practical applications in tennis (Vol. 2). Springer Science & Business Media.

- Alhalal, E.; Ta’an, W.; Alhalal, H. Intimate Partner Violence in Saudi Arabia: A Systematic Review. Trauma Violence Abus. 2021, 22, 512–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camara, A.H. The importance of factor analysis in quantitative and qualitative X-ray diffraction phase analysis. Koroze A Ochr. Mater. 2014, 58, 52–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazzaz, Y.M.; AlAmeer, K.M.; AlAhmari, R.A.; Househ, M.; El-Metwally, A. The epidemiology of domestic violence in Saudi Arabia: a systematic review. Int. J. Public Health 2019, 64, 1223–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wali, R.; Khalil, A.; Alattas, R.; Foudah, R.; Meftah, I.; Sarhan, S. Prevalence and risk factors of domestic violence in women attending the National Guard Primary Health Care Centers in the Western Region, Saudi Arabia, 2018. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivancevic, T. T., & Fidell, L. S. (2001). Using Multivariate Statistics Needham Heights. MA: Allyn & Bacon.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).