Submitted:

06 June 2024

Posted:

10 June 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

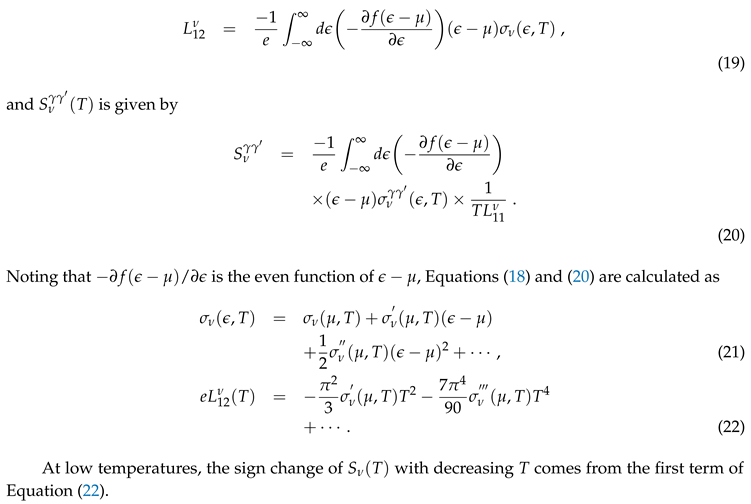

2. Formulation

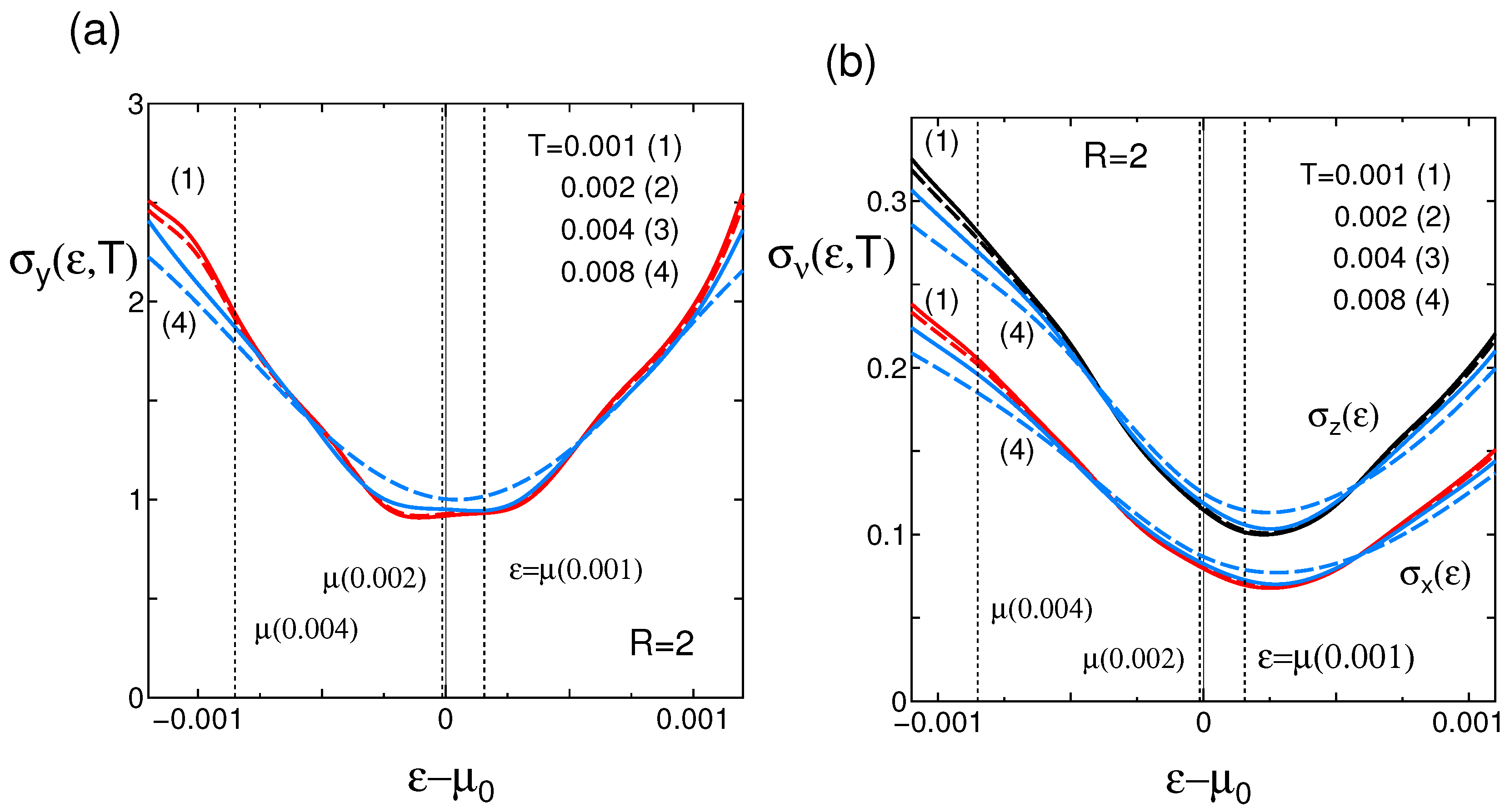

2.1. Model

2.2. Dirac Points and DOS

2.3. Electric Transport

3. Electronic States

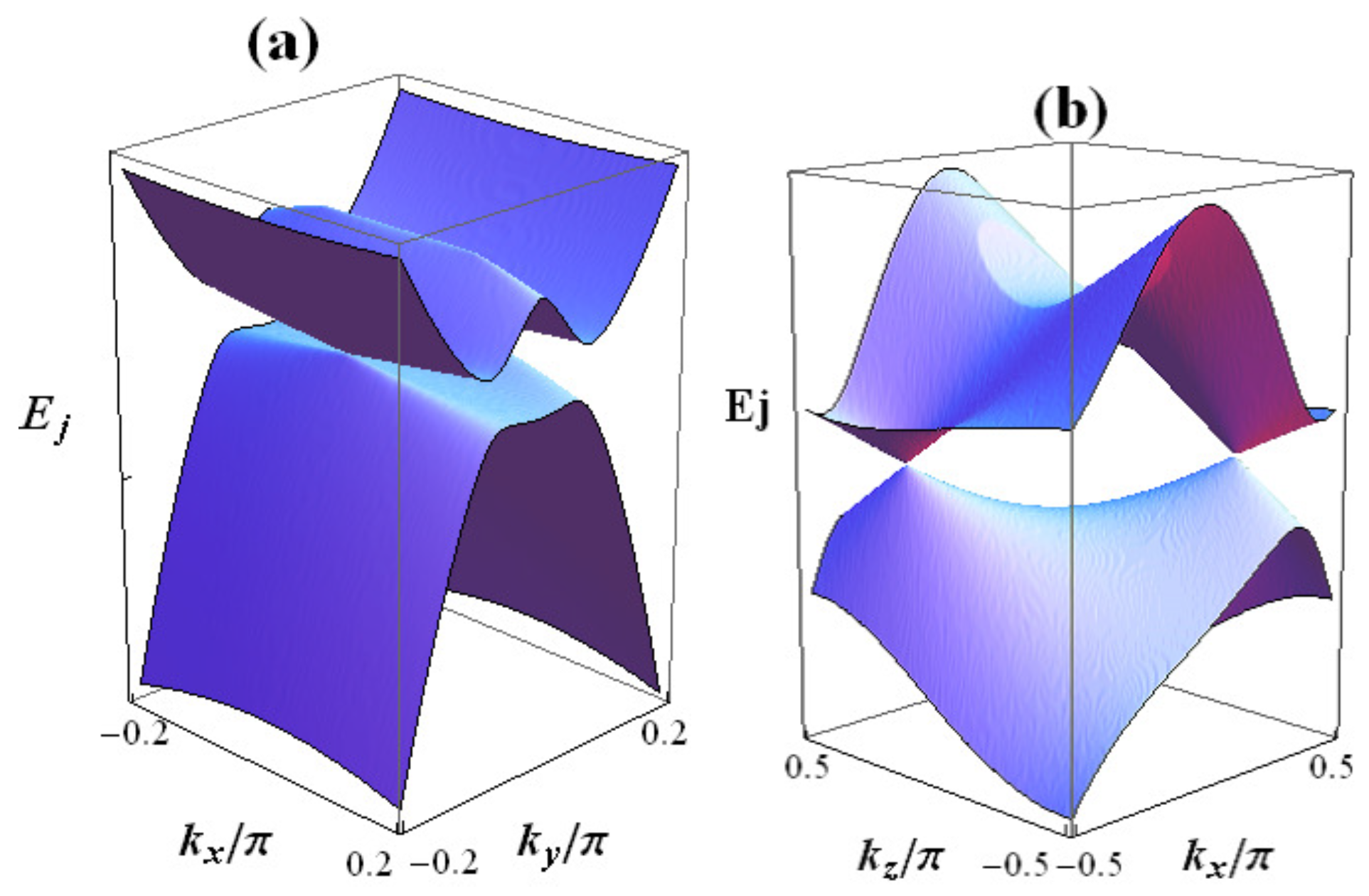

3.1. Energy Band

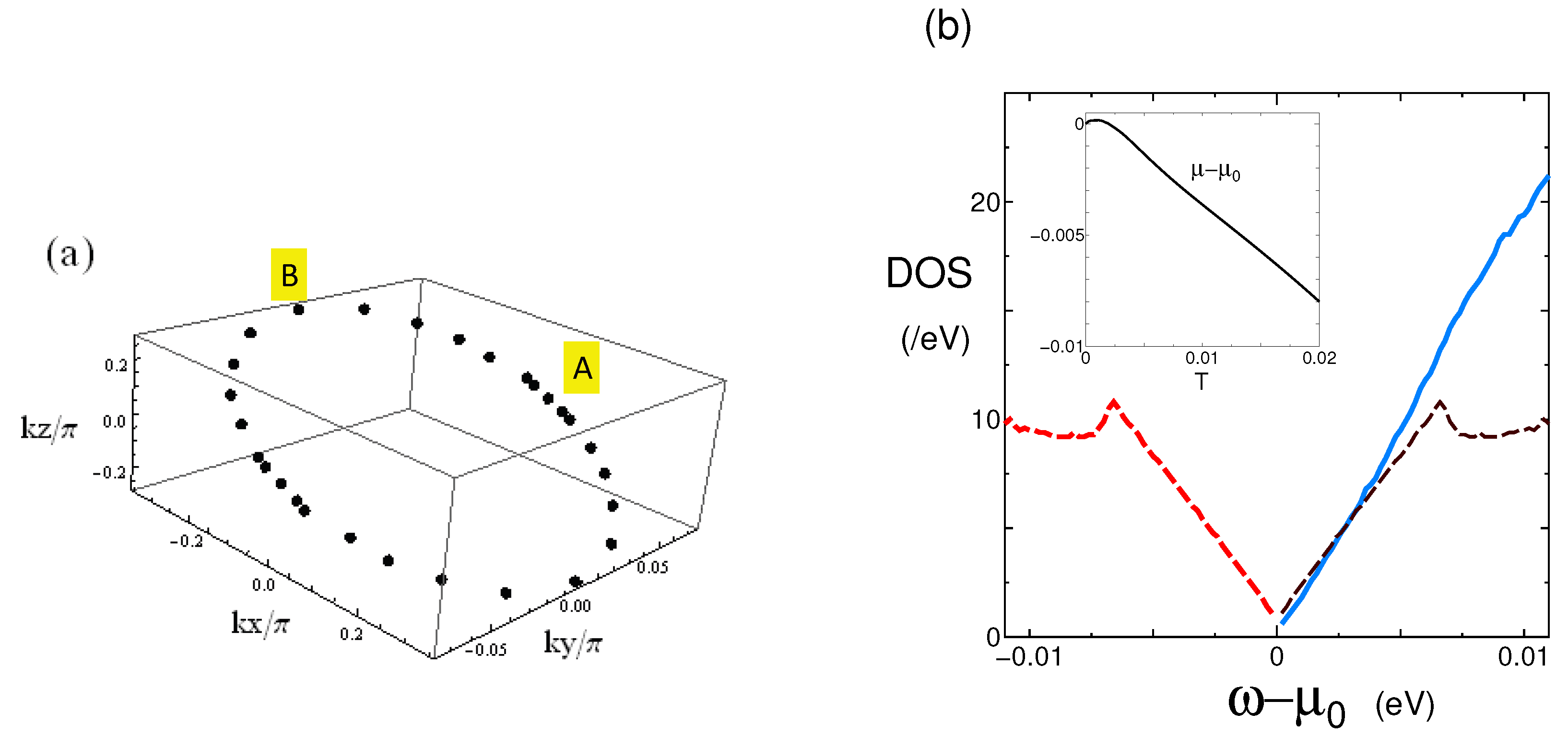

3.2. Nodal Line and DOS

4. Seebeck Coefficients

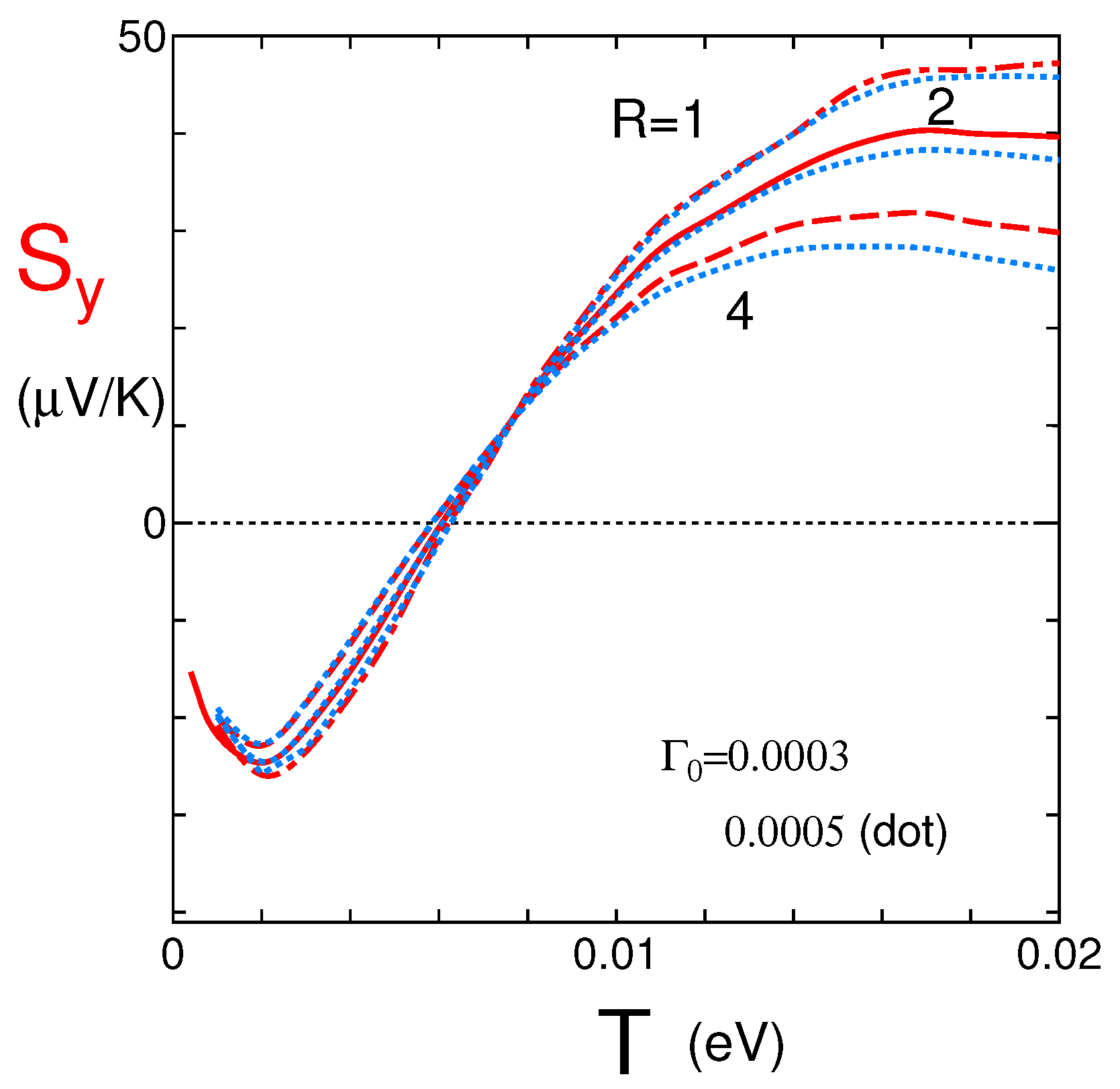

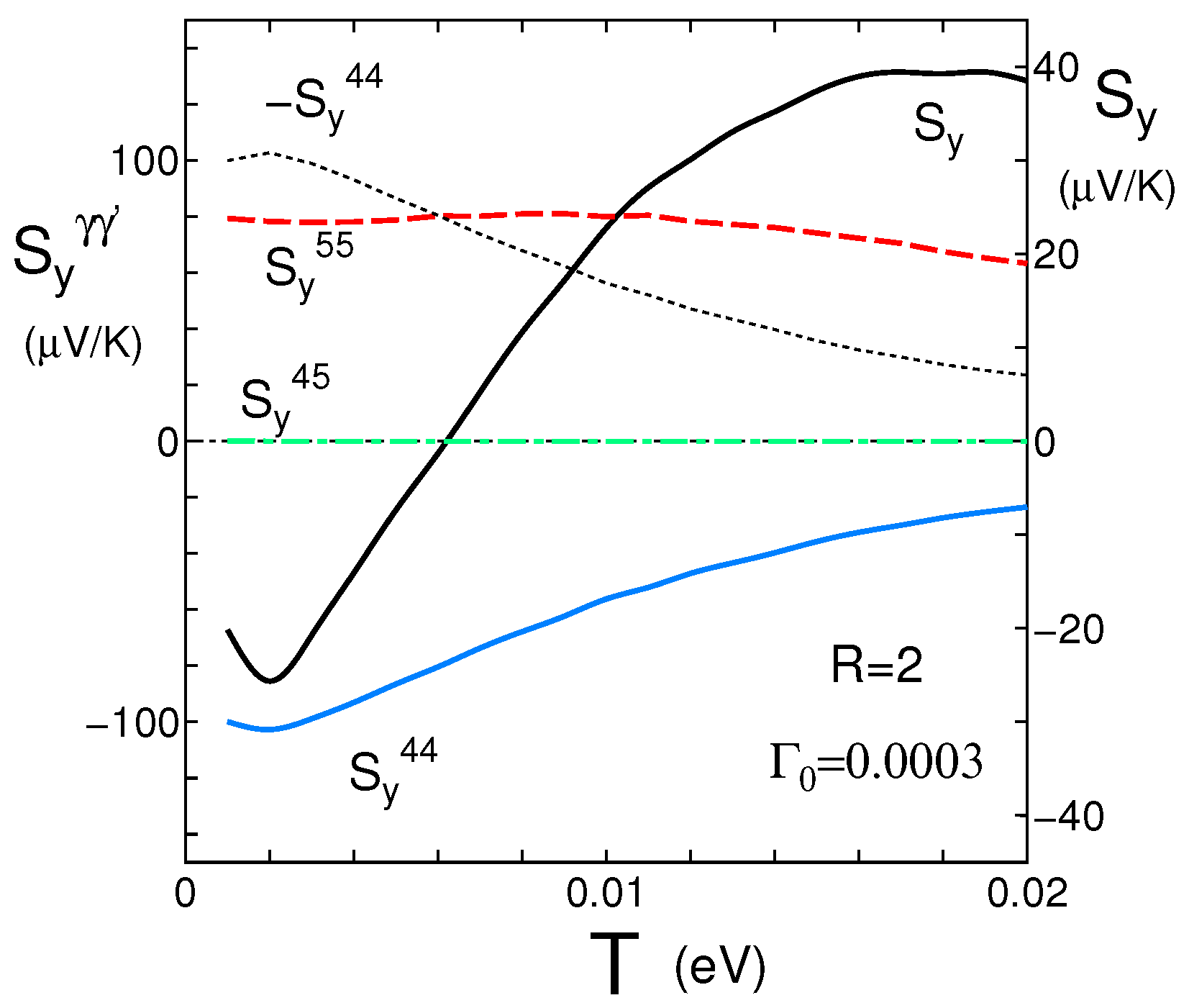

4.1. Coefficient for the y-Axis Direction

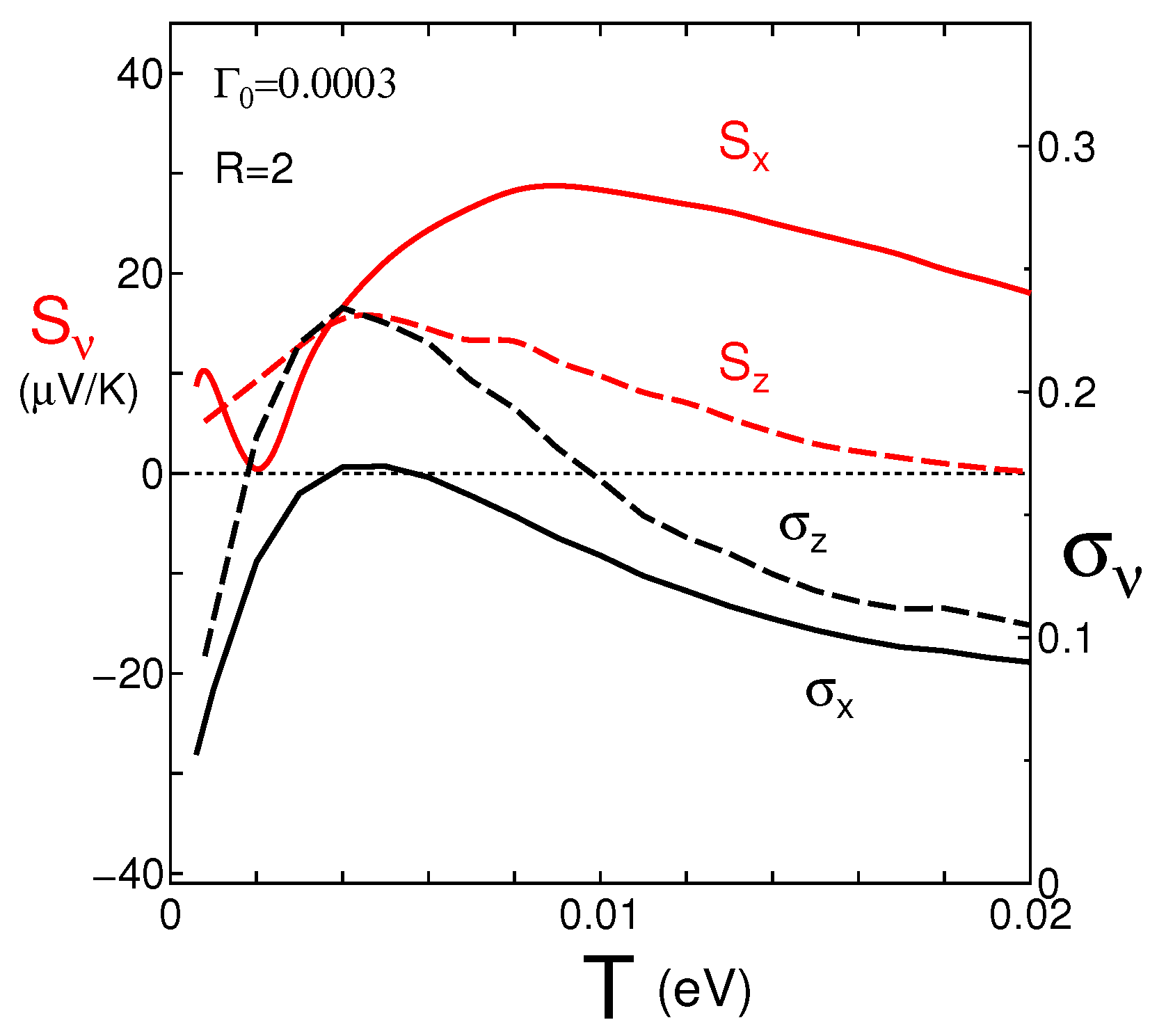

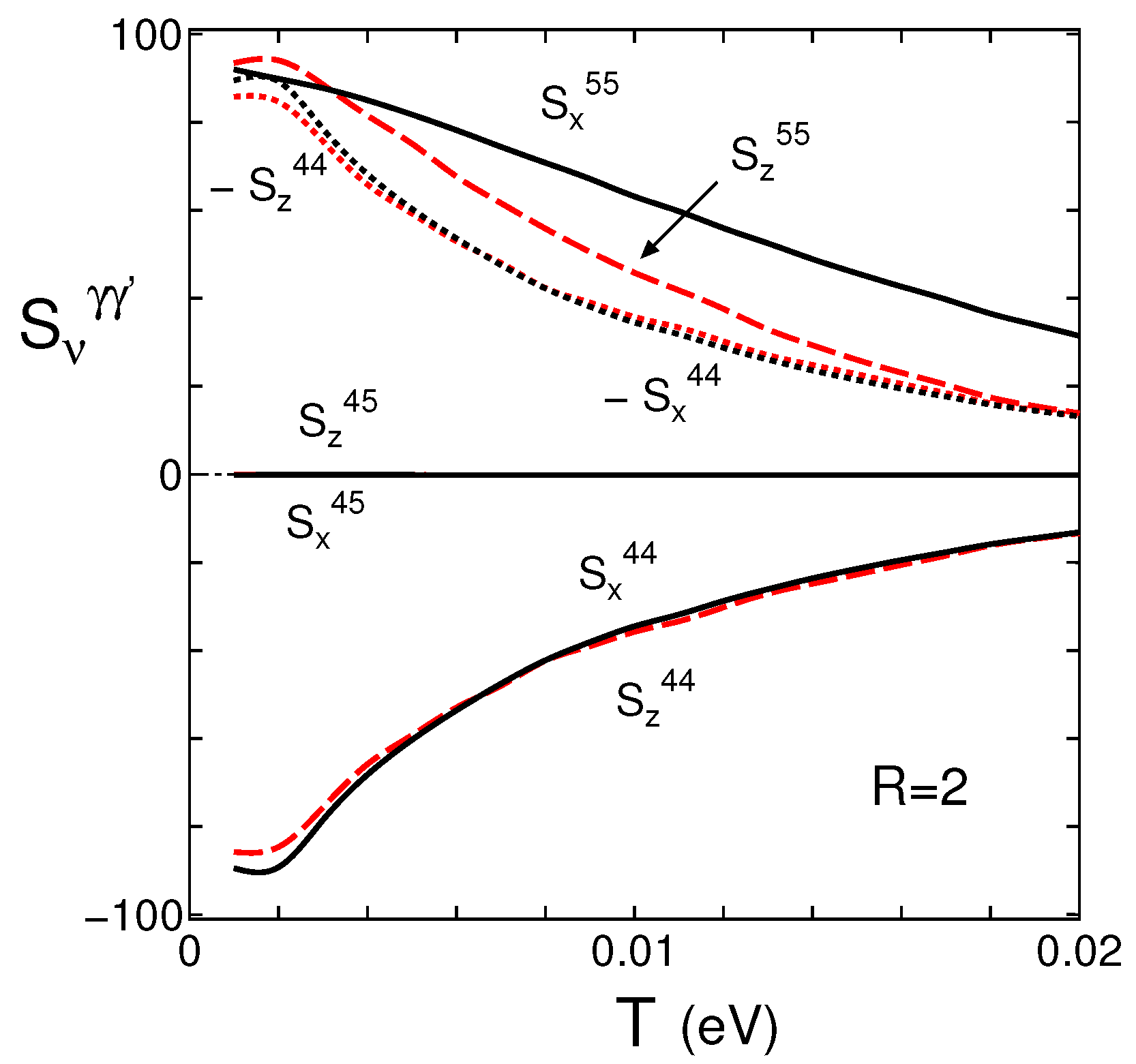

4.2. Coefficients for the x and z-Axes Directions

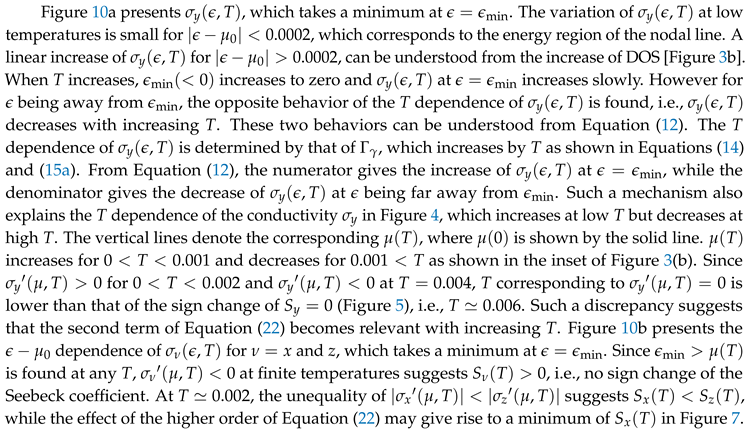

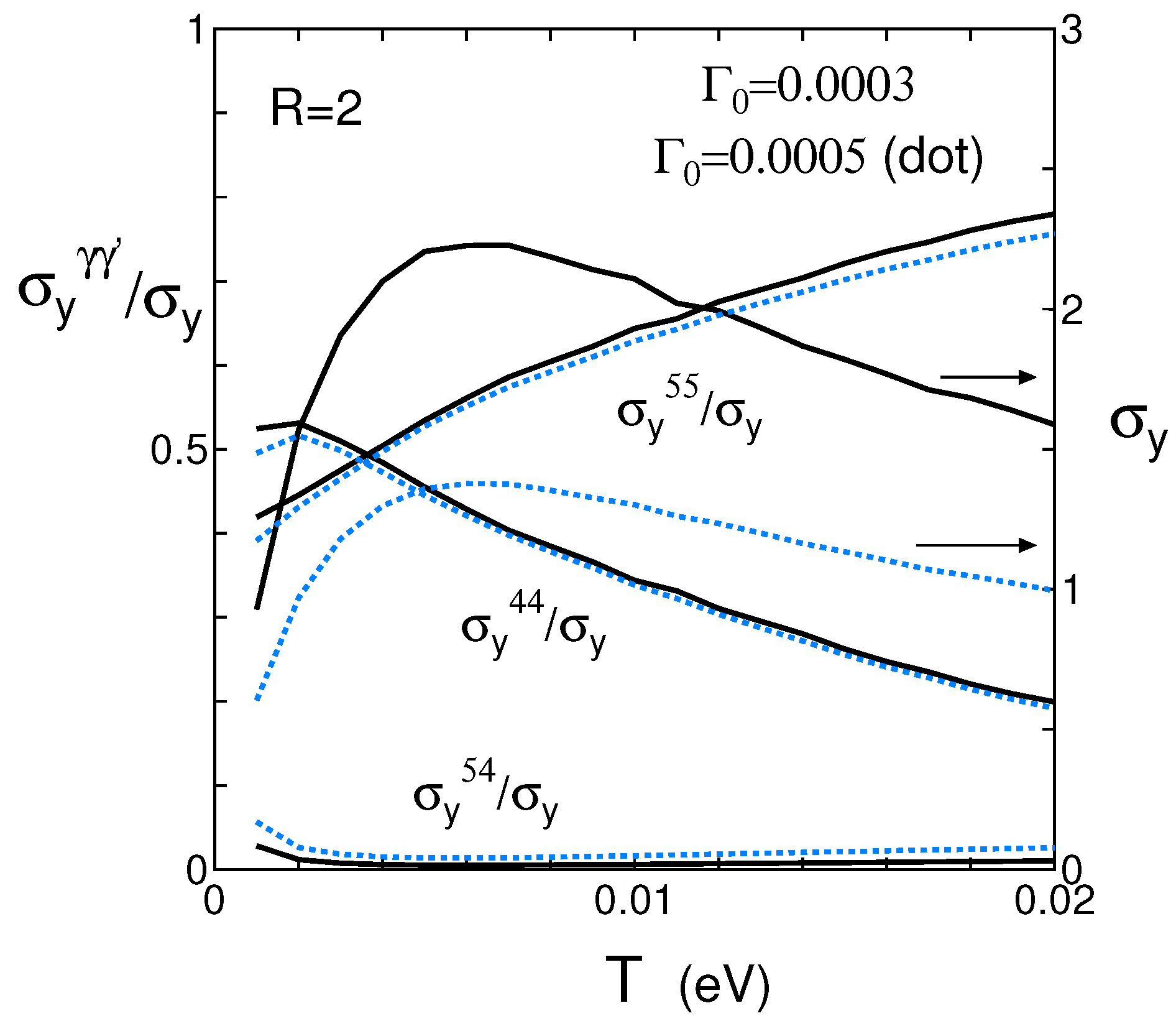

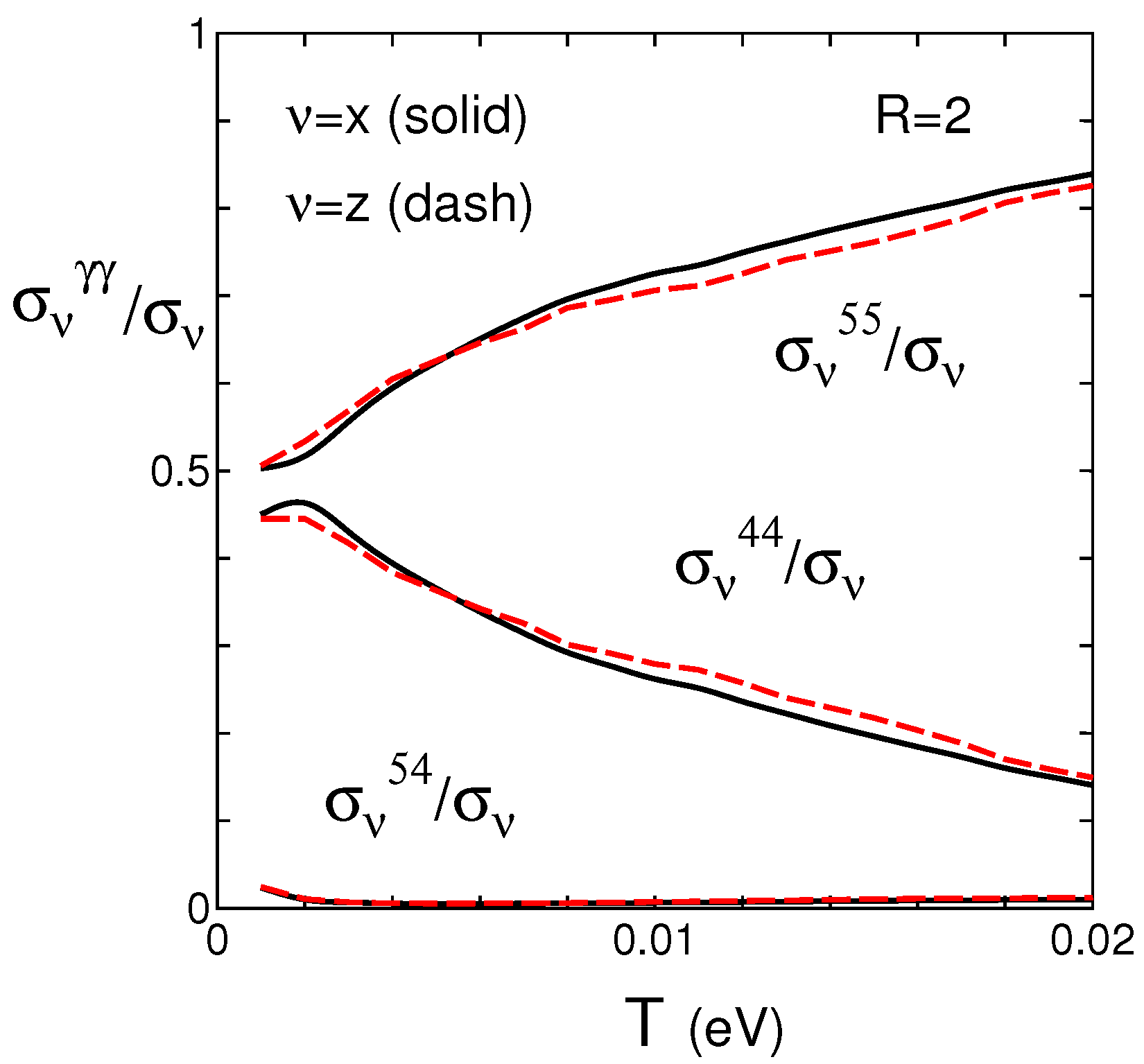

4.3. Spectral Conductivity

5. Summary and Discussion

Acknowledgments

References

- K. S. Novoselov, A. K. Geim, S. V. Morozov, D. Jiang, M. I. Katsnelson, I. V. Grigorieva, S. V. Dubonos, and A. A. Firsov, Nature 438, 197 (2005).

- K. Kajita, Y. Nishio, N. Tajima, Y. Suzumura, and A. Kobayashi, J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 83, 072002 (2014).

- R. Kato, H. B. Cui, T. Tsumuraya, T. Miyazaki, and Y. Suzumura, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139, 1770 (2017).

- S. Katayama, A. Kobayashi, and Y. Suzumura, J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 75, 054705 (2006).

- A. Kobayashi, S. Katayama, K. Noguchi, and Y. Suzumura, J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 73, 3135 (2004).

- T. Mori, A. Kobayashi, Y. Sasaki, H. Kobayashi, G. Saito, and H. Inokuchi, Chem. Lett. 13, 957 (1984).

- R. Kondo, S. Kagoshima, and J. Harada, Rev. Sci. Instrum. 76, 093902 (2005).

- R. Kondo, S. Kagoshima, N. Tajima, and R. Kato, J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 78, 114714 (2009).

- H. Kino and T. Miyazaki, J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 75, 034704 (2006).

- A. Kobayashi, S. Katayama, Y. Suzumura, and H. Fukuyama, J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 76, 034711 (2007).

- M. O. Goerbig, J.-N. Fuchs, G. Montambaux, and F. Piéchon,Phys. Rev. B 78, 045415 (2008).

- A. Kobayashi, Y. Suzumura, and H. Fukuyama, J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 77, 064718 (2008).

- N. Tajima, R.. Kato, S. Sugawara, Y. Nishio, and K. Kajita, Phys. Rev. B 85, 033401 (2012).

- N. H. Shon and T. Ando, J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 67, 2421 (1998).

- N. M. R. Peres, F. Guinea, and A. H. Castro Neto, Phys. Rev. B 83,125411 (2006).

- K. Kajita, T. Ojiro, H. Fujii, Y. Nishio, H. Kobayashi, A. Kobayashi, and R. Kato, J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 61, 23 (1992).

- N. Tajima, M. Tamura, Y. Nishio, K. Kajita, and Y. Iye, J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 69, 543 (2000).

- N. Tajima, A. Ebina-Tajima, M. Tamura, Y. Nishio, and K. Kajita, J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 71, 1832 (2002).

- N. Tajima, S. Sugawara, M. Tamura, R. Kato, Y. Nishio, and K. Kajita, EPL 80, 47002 (2007).

- D. Liu, K. Ishikawa, R. Takehara, K. Miyagawa, M. Tanuma, and K. Kanoda, Phys. Rev. Lett. 116, 226401 (2016).

- Y. Suzumura and M. Ogata, Phys. Rev. B 98, 161205 (2018).

- H. B. Cui, T. Tsumuraya, Y. Kawasugi, R. Kato R. presented at 17th Int. Conf. High Pressure in Semiconductor Physics (HPSP-17), (2016).

- T. Tsumuraya, H. B. Cui, T. Miyazaki, R. Kato, presented at Meet. Physical Society Japan, (2014).

- R. Kato and Y. Suzumura, J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 86, 064705 (2017).

- S. Murakami, New J. Phys. 9 356 (2007).

- M. Hirayama, R. Okugawa, S. Murakami, J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 87, 041002 (2018).

- A. Bernevig, H. Weng, Z. Fang, X. Dai, J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 2018, 87, 041001 (2018).

- Z. Liu, H. Wang, Z.F. Wang, J. Yang, F. Liu, Phys. Rev. B 97, 155138 (2018).

- T. Tsumuraya, R. Kato, Y. Suzumura, J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 87, 113701 (2018).

- Y. Suzumura, H. B. Cui, R. Kato, J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 87, 084702 (2018).

- R. Kato, H. Cui, T. Minamidate, H. H.-M. Yeung, and Y. Suzumura, J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 89,124706 (2020).

- Y. Suzumura, R. Kato, and M. Ogata, Crystals 10, 862 (2020). see also http://arxiv.org/abs/2009.05272.

- R. Kubo, J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 12, 570 (1957).

- J. M. Luttinger, Phys. Rev. 135, A1505 (1964).

- M. Ogata and H. Fukuyama, J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 88, 074703 (2019).

- R. Kitamura, N. Tajima, K. Kajita, R. Reizo, M. Tamura, T. Naito, and Y. Nishio, JPS Conf. Proc..1, 012097 (2014); N. Tajima, private communication.

- T. Konoike, M. Sato, K. Uchida, and T. Osada, J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 82, 073601 (2013).

- D. Ohki, Y. Omori, and A. Kobayashi. Phys. Rev. B 101, 245201 (2020).

- Y. Suzumura and M. Ogata, Phys. Rev. B 107, 195416 (2023).

- Y. Suzumura, T. Tsumuraya and M. Ogata, J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 93, 054704 (2024).

- H. Fröhlich, Proc. Phys. Soc. A 223, 296 (1954).

- S. Katayama, A. Kobayashi, and Y. Suzumura, J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 75, 023708 (2006).

- A. A. Abrikosov, L. P. Gorkov, and I. E. Dzyaloshinskii, Methods of Quantum Field Theory in Statistical Physics (Prentice-Hall, Englewood Cliffs, NJ, 1963).

- M.J. Rice, L. Pietronero, and P. Brüesh, Solid State Commun. 21, 757 (1977).

- H. Gutfreund, C. Hartzstein, and M. Weger Solid State Commun. 36, 647 (1980).

| (stacking) | ||||

| Layer 1 | ||||

| — | — | |||

| (stacking) | ||||

| Layer 2 | ||||

| — | — | |||

| Interlayer | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).