Introduction

ClpB protein despite its name (abbreviation from caseinolytic protease [

1,

2]) is not a protease but an AAA ATPase chaperone, and in

E. coli cells along with two other proteins, ClpA and ClpX, it belongs to the HSP100 family of heat shock proteins [

3]. It is known that ClpA and ClpX proteins are likewise chaperones [

4,

5], but additionally can form a complex with the protease subunit ClpP and determine some substrate specificity in the proteolysis of various cellular proteins by ClpAP and ClpXP complexes [

6,

7,

8], whereas ClpB can’t do it. ClpB is characterized by its interaction with the DnaKJ/GrpE chaperone complex [

9], in particular, DnaK-dependent refolding of bacterial luciferases drops approximately 10-fold in the

сlpB- mutant cells [

10]. ClpE, ClpC, and ClpL proteins from Gram-positive organisms are homologs of the Clp family, but differ in some structural elements [

11,

12].

Bacterial proteins of Clp-family often play an important role in the interaction of bacterial cells with eukaryotic organisms. In particular, elevated plasma concentrations of bacterial ClpB protein have been observed in patients with eating disorders [

13]. It was shown in the works [

14,

15] that the bacterial protein ClpB is a conformational mimetic of α-MSH, and may play a role in the transmission of satiety signals.

L. fermentum is commonly isolated from the gastrointestinal tract. Several

L. fermentum strains have been described to possess immunomodulatory, anti-inflammatory, antiviral, and anti-oxidative effects in experiments with in vitro models, preclinical studies, and human trials [

16,

17,

18]. Thus,

L. fermentum strains have great potential for the formulation of novel biotherapeutics ― pharmabiotics.

The

L. fermentum U-21 strain, isolated in the Laboratory of Microbial Genetics, Vavilov Institute of General Genetics RAS, showed high antioxidant activity in studies on in vitro models using the oxidative stress inducer paraquat [

19]. In vivo experiments on a model of paraquat-induced Parkinsonism in mice showed that administration of

L. fermentum U-21 improved movement coordination and prevented degradation of dopaminergic brain neurons [

20], increased survival, preservation of tyrosine hydroxylase-positive nerve fibres, and the number of goblet cells in enteric nerve plexuses in rats [

21]. High biological activity was also observed in the neurotoxic model of MPTP-induced Parkinsonism in mice [

22]. Taken together, these data demonstrate the unique antioxidant activity properties of this strain, allowing us to position it as a promising candidate for the development of pharmaceuticals aimed at preventing and treating various inflammatory conditions, such as Parkinsonism.

In [

23] it was shown that the strain

L. fermentum U-21 could secrete into the culture medium the protein encoded by the clp-family gene in the locus C0965_000195, in contrast to

L. fermentum strains 103 and 279, which did not exhibit antioxidant properties. In the same work, this gene was denoted as

clpB and it was suggested that secreted ClpB might participate in the formation of the pharmabiotic properties of U-21 by refolding proteins misfolded due to oxidative stress in various tissues of the animal body.

The present work is devoted to the study of the chaperone properties of this Clp-protein in order to characterize it as a component of the disaggregase activity of L. fermentum U-21. The annotation of the gene located at locus C0965_000195 was refined as clpL. The ability of clpL to accelerate the refolding of thermodenatured proteins was investigated in vivo using luciferase model in E. coli clpB- cells characterized by a reduced level of refolding. In experiments with purified P. luminescens luciferase, the effect of the compounds and proteins from the spent L. fermentum U-21 culture medium (SCM) on the thermodenaturation of luciferase at 45 °C was investigated in vitro.

Materials and Methods

Bacterial strains and plasmids. The following strains were used in the study:

L. fermentum U-21 (collection number VKPM V-12075, NCBI Genome assembly ASM286982v2);

E. coli SG20250 (Δ

lacU169

araD

flbB

relA

clpB

+), and its insertion derivative SG22100

clpB::

kan- (kindly provided by S. Gottesman) [

24];

E. coli XL1-Blue (recA1 endA1 gyrA96 thi-1 hsdR17 supE44 relA1 lac [F’proAB lacIqZΔM15 Tn10 (Tetr)]) (Stratagene, USA);

E. coli BL21-Gold (DE3) (F– ompT dcm+ TetR gal lon hsdSB(rB– mB–) λ(DE3 [lacI lacUV5-T7p07 ind1sam7 nin5]) used for the biosynthesis of luciferase LuxAB and NADH-FMN oxidoreductases LuxG (obtained from VKPM);

E. coli TG1 (thi relA supE44 hsdR17 hsdM Δ(lacproAB) [F’traD36 proAB lacIqZ ΔM15]) for plasmid preparation (obtained from VKPM).

Description of the plasmids used in this work is given in

Table 1.

Cultivation Conditions

The

L. fermentum U-21 strain was grown on the MRS medium (HiMedia) at 37 °C under partially anaerobic conditions (in a desiccator where oxygen was burned up by burning a candle). The

E. coli strains were cultivated in Lysogeny Broth (LB), solid growth media contained 1.5 % (w/v) agar [

28]. The medium was supplemented with ampicillin (150 mg/L), tetracycline (10 mg/L), or chloramphenicol (10 mg/L) as needed. For blue-white screening during pUC19:clpL cloning, 50 µg/ml IPTG and X-gal were added into the medium.

DNA manipulations. Genomic DNA of

L. fermentum U-21 strain was obtained using the GenElute bacterial genomic DNA kit (Sigma Aldrich Inc., USA). Isolation of plasmid DNA, preparation of competent

E. coli cells, and transformation were carried out using standard methods [

28]. DNA fragment encoding ClpL

, previously annotated like ATP-dependent Clp protease ATP-binding subunit ClpB [

23], was amplified from the

L. fermentum U-21 genomic DNA using a Tersus Plus PCR kit (Evrogen, Russia) with oligonucleotides ClpL-N and ClpL-C with a PTC-0150 minicycler (MJ Research Inc., USA). The amplified DNA fragment was cloned into a pUC19 plasmid at the

HindIII and

XbaI restriction sites. The resulting recombinant clones, containing the final plasmid рUC19:clpL, were screened by PCR using M13dirShort and M13rev standard primers.

Preparation of p15FisAB plasmid based on p15 replicon for the expression of

A. fischeri luxAB genes in

E. coli cells:

A. fischeri luxAB genes were amplified from plasmid pF6 and ligated with EcoRI-linearized p15Tc-lac vector using Gibson Assembly [

29].

Similarly, p15XenAB plasmid based on p15 replicon was obtained for the expression of P. luminescens luxAB genes, pXen7 plasmid with the complete lux-operon of P. luminescens was used as genes source.

To construct pABX-T7, luxAB fragment from pXen7 was amplified, then it was cloned in BamHI-NcoI sites of the pET15b vector. As a result, luxAB genes were placed downstream of the T7 promoter with the addition of the 6×His-tag at the N-terminus of LuxA.

pLuxG-T7 plasmid was prepared by linearizing the pET15b vector by NdeI restriction endonuclease, amplifying the

luxG gene from the genomic DNA of

Vibrio aquamarinus [

30], and ligating the resulting fragments with the use of Gibson Assembly.

Primers used in the study are presented in

Table S1.

Expression of the clpL gene from L. fermentum U-21 strain in E. coli. Transformant clones of E. coli XL1-Blue strain containing recombinant plasmid pUC19:clpL were seeded in liquid LB medium with ampicillin and grown in a shaker-incubator for 18 hours at 37 °C, 250 rpm. Then, overnight culture was diluted 1:100 with a fresh LB and grown in a shaker-incubator at 37 °C, 250 rpm. Probes were collected at the following time points: 2, 3, 4, 5, and 24 hours of incubation. The culture OD was measured on a spectrophotometer at λ=600 nm.

To investigate clpL gene expression, cells were precipitated by centrifugation, suspended in sample buffer (62.5 mM Tris-HCl, pH 6.8, 5% glycerol, 2% 2-mercaptoethanol, 0.1% SDS, 0.001% bromphenol blue) and heated at 95°C for 10 min. The proteins were analyzed by SDS-PAGE. E. coli XL1-Blue cells containing plasmid pUC19 without insertion were used as a negative control.

In vivo Luminescence Measurement

Luminescent cells at the early stationary growth phase were suspended in LB medium to a final OD of ~0.01. For in vivo thermal inactivation of A. fischeri luciferase, E. coli cells containing the corresponding genes were incubated in a water bath at 44°C for 9-15 min, for P. luminescens luciferase at 47°C for 20 min. The production of luciferase and heat shock proteins was stopped by the addition of chloramphenicol with a final concentration of 167 μg/ml. For subsequent refolding, cells were transferred back to a lower temperature (22 °C). Luminescence measurements (in RLU, Relative Light Unit) were performed using a Biotox-7BM luminometer (BioPhysTech, Russia). Activation of luciferase reaction was carried out by adding 0.001% decanal.

Biosynthesis, Isolation, and Purification of P. luminescens Luciferase and V. aquamarinus LuxG

Purification of P. luminescens luciferase (LuxAB): the protein was expressed in E. coli BL21-Gold (DE3). Cells were cultured in shaking baffled flasks in LB medium containing 150 mg/L ampicillin. Protein expression was induced with 1 mM IPTG and continued for 22 hours at 20 °C. Harvested cells were resuspended in phosphate-buffered saline with the addition of 1 mM PMSF and disrupted in M-110P Lab Homogenizer (Microfluidics, USA) at 25 000 psi. The lysate was clarified by removal of cell membrane fraction by ultracentrifugation at 40 000 g for 1 h at 10º C. The supernatant was incubated with Ni-nitrilotriacetic acid (Ni-NTA) resin (Qiagen, Germany) on a rocker for 1 hour at 4 ºC. The Ni-NTA resin and supernatant were loaded on a gravity flow column and washed with buffer containing 150 mM NaCl and 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, supplemented with 20 mM imidazole. The protein was eluted in a buffer containing 50-200 mM imidazole, 150 mM NaCl and 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0.

To purify LuxG, the same method was used with some modifications: the LuxG protein was predominantly in an aggregated state, thus after cell lysis it was dissolved in 2 M urea, then centrifuged at 15 000 g, and the supernatant was applied to Ni-NTA. The column was washed off as described above. The resulting LuxG protein had a concentration of about 0.2 mg/ml and exhibited enzymatic activity; it was further used to restore FMN in the luciferase reaction.

Spent L. fermentum U-21 Culture Medium

To prepare a spent culture medium (SCM), L. fermentum U-21 cells were cultured during 24 hours, centrifuged at 7000 rpm and filtered (0.22 µm). To inactivate proteins, the obtained SCM was heated to 100°C for 30 min.

Measurement of P. luminescens Luciferase Activity In Vitro

The purified LuxAB protein was added in (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl buffer) at the final concentration of 0.2 μg/μL to the reaction solution: 20 μM FMN, 0.2 mM NADH, 20 μg/mL LuxG, 1 mM ATP, subsequently, the solution was divided into three samples. In the first sample, 10 μL of SCM containing ClpL was added. In the second sample, 10 μL of SCM containing ClpL inactivated at 100 °C was added. The third sample served as a control without the addition of SCM. All three samples were heated at 45°C for 9-11 minutes. After thermoinactivation, refolding was observed through periodical sampling and luminescence measurements at room temperature. The reaction was triggered by the addition of the luciferase substrate decanal at the final concentration of 0.001% (v/v). Luminescence measurements (in RLU, Relative Light Unit) were performed with the use of Biotox-7BM luminometer.

Phylogenetic and Molecular Evolutionary Analysis

Phylogenetic and molecular evolutionary analysis was conducted using MEGA11 (MUSCLE algorithm) [

31]. Phylogenetic trees were inferred using neighbor-joining method incorporated in MEGA11. For the phylogeny analysis, reference sequences of Clp proteins from different organisms were retrieved from GenBank (

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genbank/) and their GenBank IDs are given in text.

Results

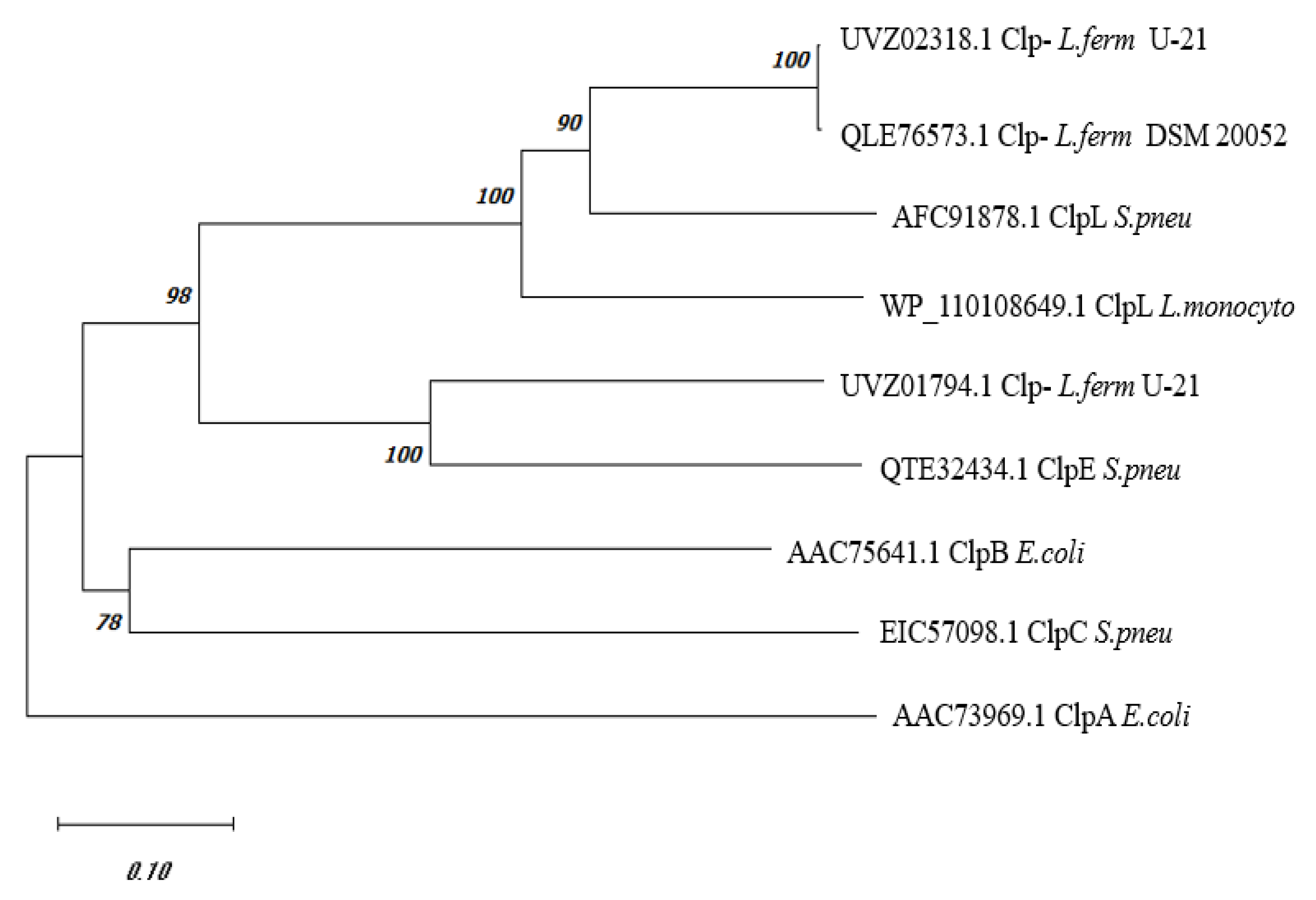

Phylogenetic Analysis of C0965_000195 L. fermentum U-21

Comparison of the amino acid sequence of the

L. fermentum U-21 UVZ02318.1 protein (product of gene expression from the C0965_000195 locus), annotated as «ATP-dependent Clp protease ATP-binding subunit or ClpB» [

23], with the sequences of ClpA (AAC73969.1) and ClpB (AAC75641.1) from

E. coli MG1655 shows 39.51 and 41.96% similar amino acids, respectively. Comparison of the sequences of ClpA and ClpB from

E. coli with each other also gives approximately 40.1% identical amino acids. Other proteins of Clp-family: ClpC, ClpE and ClpL, are found in Gram-positive bacteria. A phylogenetic tree constructed using the amino acid sequences of UVZ02318.1

L. fermentum U-21 and a series of Clp proteins from

Streptococcus pneumonia and

Listeria monocytogenes with a function described in the literature [

8,

11,

12,

32] [

33]is shown in

Figure 1. The sequence QLE76573.1 from the type strain

L. fermentum DSM 20052, which currently remains unannotated, and has 99.57% identical amino acids with UVZ02318.1 is added to the tree for reference. The sequence UVZ01794.1 of

L. fermentum U-21 annotated as ClpA, which has 50% identical amino acids to the UVZ02318.1, is shown too.

As can be seen from the data in

Figure 1, the phylogenetic tree allows one to assign with some certainty UVZ02318.1 and QLE76573.1 proteins from

L. fermentum as ClpL, and UVZ01794.1 protein as ClpE.

It was described in [

34] that a distinctive feature of ClpB protein is the presence of M-domain in the structure (396-512 aa for WP_011228712). No homologous sequence corresponding to the M-domain of ClpB was found in UVZ02318.1. It should be noted that in ClpA the M-domain is completely absent, while in ClpC, ClpE, and ClpL proteins this domain is present but has a smaller size and its structure differs significantly from ClpB M-domain.

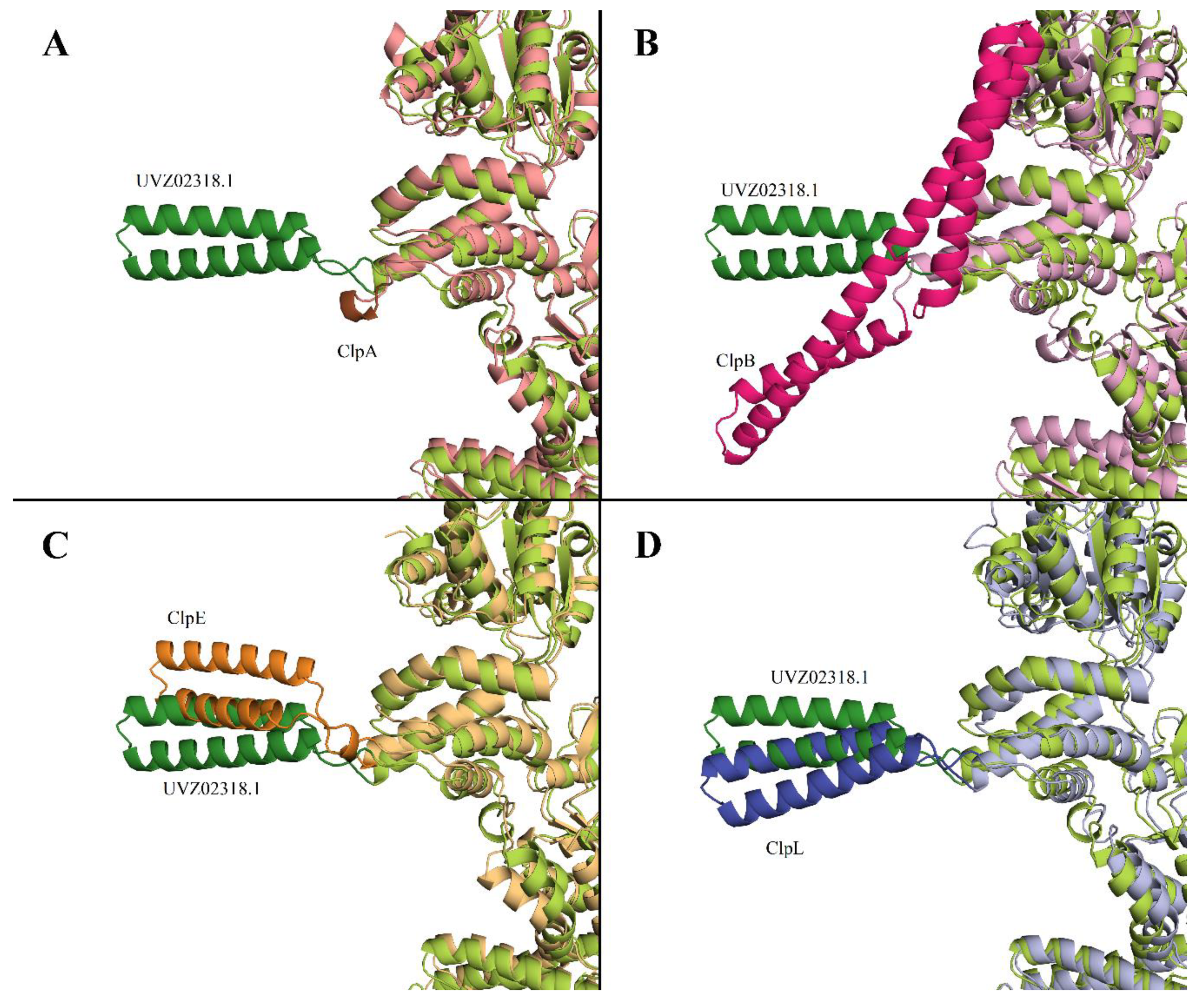

Figure 2 shows a comparison of the AlphaFold models of ClpA, ClpB, ClpL, and ClpE proteins with the AlphaFold-predicted structure of Clp-protein UVZ02318.1. The M-domain is highlighted in more intense colors.

Based on the comparison of the structure models of UVZ02318.1 with other Clp-family proteins, it can be seen that with overall close similarities in protein structures and differences in the M-domain, it is closest to ClpL and to some extent to ClpE.

Thus, bioinformatic analysis of the UVZ02318.1 protein encoded by the gene at locus C0965_000195 shows that it belongs to the Clp-protein family and is similar in structure to ClpL. Alignment with known Clp-proteins with confirmed function shows clustering of UVZ02318.1 and its close homologue QLE76573.1 from

L. fermentum DSM 20052 with the ClpL protein from

S. pneumonia (

Figure 1). In our further work, the UVZ02318.1 protein will be referred to as

L. fermentum U-21 ClpL.

Gene Cloning and Expression, and Chaperone Activity Investigation of the L. fermentum U-21 ClpL Protein in E. coli Cells

To investigate the chaperone activity of ClpL from

L. fermentum U-21, the

clpL gene was cloned and expressed in a heterologous system of

E. coli cells. To analyze the expression of the

clpL gene in

E. coli, the XL1-Blue strain containing recombinant plasmid pUC19:clpL was grown in liquid LB medium. The soluble fraction of proteins was analyzed by SDS-PAGE (

Figure S1). During the stationary growth phase and at the beginning of the logarithmic growth phase (after 2 h), an additional protein fraction with a molecular mass of about 77.5 kDa was observed in

E. coli cells containing the pUC19:clpL plasmid, which corresponds to the calculated molecular mass of the ClpL protein in combination with the molecular mass of the linker protein of the pUC19 plasmid. Mass-spectrometric analysis confirmed that this protein is an “ATP-dependent Clp protease ATP-binding subunit” ClpL of

L. fermentum U-21. It was shown that high content of ClpL protein led to a delay in transition to exponential growth phase of strain XL-1 pUC19:clpL in comparison with the control strain XL-1 pUC19 (

Figure S2).

It is known that

E. coli cells mutant in

clpA and

clpB genes have a diminished ability to refold heat-inactivated proteins [

10,

35]. Thus, such strains are model hosts for investigation of the ability to compensate for chaperone function of various heterologous proteins. To test the ability of ClpL to complement the ClpB absence in refolding of denatured proteins,

E. coli SG20250 and its insertion derivative SG22100

clpB::kan- were used.

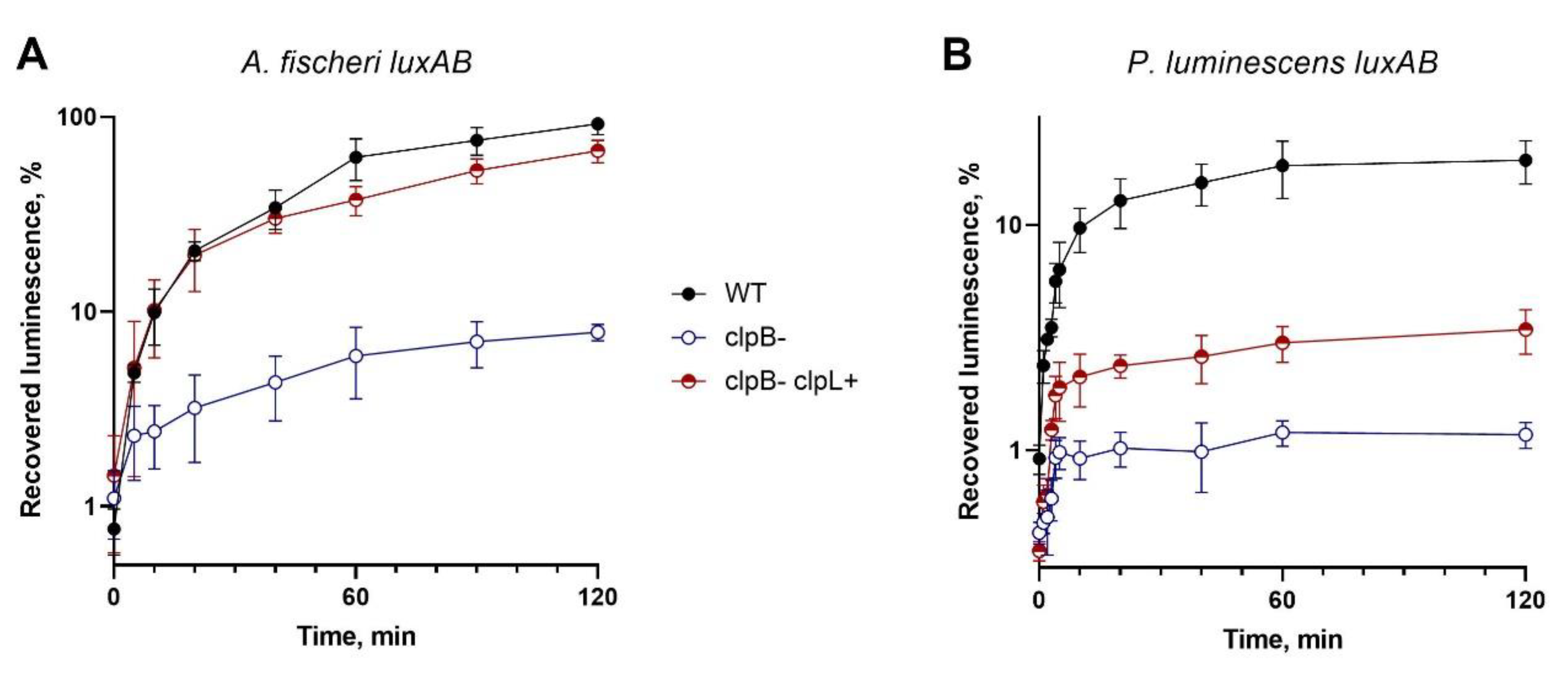

Figure 3 shows recovery of luminescence after heat-inactivation of luciferases in cells SG20250 p15XenAB (or p15FisAB), SG22100 p15XenAB (or p15FisAB), and SG22100 pUC19:clpL p15XenAB (or p15FisAB). pUC19:clpL drives heterologous expression of

clpL from

L. fermentum U-21; p15XenAB and p15FisAB are compatible with pUC19:

clpL and drive heterologous expression of

luxAB from

P. luminescens and

A. fischeri, correspondently.

As can be seen from the data presented in

Figure 3, pUC19:clpL almost completely compensates for the deletion of

clpB during the refolding of the thermolabile luciferase of

A. fischeri and partially compensates for it during the refolding of the more thermostable luciferase of

P. luminescens. The obtained results are consistent with previous data [

36], which stated that the

clpB gene in

E. coli cells affects DnaK- dependent refolding and that deletion of

clpB reduces refolding in approximately 10-times. The ability of

clpL from U-21 to compensate for the deletion of

clpB suggests the possibility of interaction of ClpL from

L. fermentum U-21 with the DnaKJE chaperone complex of

E. coli.

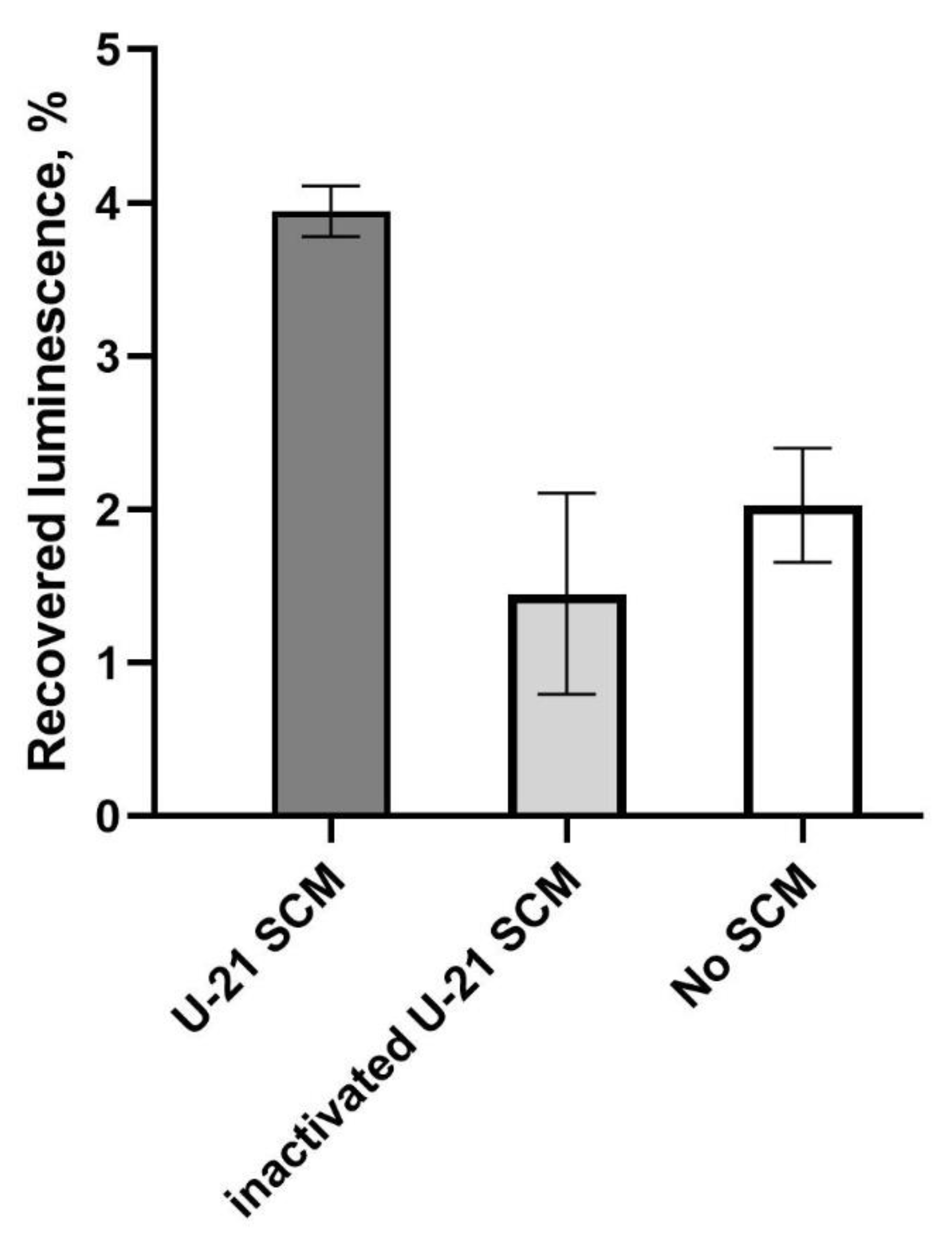

Investigation of the Chaperone Activity of L. fermentum U-21 SCM In Vitro

According to [

23] the ClpL protein is secreted by

L. fermentum U-21 cells and it is found in the SCM. Used in this study

L. fermentum U-21 SCM was analyzed by electrophoresis/mass-spectrometry and it was shown to contain a series of proteins including chaperones ClpL, DnaK, DnaJ, GroEL, GroES, ClpX, and several other Clp-family members (

Table S2). The effect of SCM on the activity of the thermodenatured luciferase was tested using purified

P. luminescens luciferase. For in vitro experiments, NADH, FMN and LuxG were added to the reaction medium to maintain the pool of reduced FMNH2, which is co-factor for the luciferase. For identification of the role of proteins from the SCM in refolding of luciferase, three types of samples were investigated and compared: luciferase reaction mixture without SCM, with addition of SCM to a final concentration of 10%, and with addition of boiled (30 min at 100 °C) SCM in the same amount. After thermal inactivation of luciferase (

45 °C for 9-11 minutes) and 4 min of refolding at room temperature, the luciferase reaction was triggered by the addition of decanal and luminescence was measured.

Figure 4 shows typical results with error-bars corresponding to measurement error. From one experiment to another, the overall refolding efficacy varies, but each time SCM enhances luminescence approximately twice, while boiled SCM does not have a significant effect.

According to the data presented in

Figure 4, the luminescence in the control sample without the addition of SCM was about 2% of the initial luminescence before thermal inactivation. The addition of SCM to the sample resulted in an increase in the luminescence level to an average of 4%. Notably, boiled SCM led to a slight decrease in luminescence after thermal inactivation, but this effect was not statistically significant.

Discussion

Bioinformatics analysis comparing the amino acid sequence encoded by the gene located at locus “C0965_000195” in

L. fermentum U-21 genome with Clp-family proteins ClpA, ClpB, ClpC, ClpE, and ClpL with a proved function (

Figure 1 and

Figure 2) allows us to assign it to

clpL, which was first described for plasmids containing a transposon-like structure [

37]. ClpL is known to exhibit chaperone activity [

38], doesn’t have a motif for binding to the protease subunit of ClpP [

39] and does not require any DnaKJ-type auxiliaries to manifest its chaperone functionin in in vitro experiments [

32].

Here, we cloned, expressed and functionally characterized the clpL gene from L. fermentum U-21 in E. coli cells. High content of ClpL was observed only at the late exponential and stationary growth phases. Cells containing ClpL transited to exponential growth phase with a significant delay. We have proven in vivo chaperone activity of ClpL from L. fermentum U-21 by observation of its ability to compensate for the absence of the clpB gene in a heterologous system of E. coli cells. At the same time, we found no compensation for refolding in clpA- mutant cells (data not presented). Since ClpL likewise ClpB protein does not bind to the protease subunit of ClpP and can compensate for ClpB absence, but not the ClpA, we hypothesized that it could have similar mechanisms of operation to ClpB.

These results were confirmed by in vitro assays. L. fermentum U-21 SCM was shown to significantly help P. luminescens luciferase to maintain a higher level of activity after inactivation by heating at 45°C for 9-11 minutes compared to a control sample in which SCM was not added.

Protein aggregation and subsequent accumulation of insoluble amyloid fibrils with cross structure is a characteristic of amyloid diseases, i.e., amyloidoses. The most well-known among them are Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, and Huntington’s diseases. Desaggregases are being intensively investigated as potential drugs targeting protein misfolding and aggregation [

40,

41]. Agents able to disaggregate preformed amyloids have been classified as molecular chaperones (e.g., Hsp70 and Hsp90), chemical chaperones (bile acids, steroid hormones, and trehalose) and pharmacological chaperones (amino acid derivatives, benzophenone, and tetracycline) [

42]. The bacterial ATPases of the Clp proteins family have been suggested to be used for such purposes [

43].

Certain bacterial strains of

Lactobacillus, Bifidobacterium, and

Faecalibacterium genera are able to alleviate symptoms of neurodegenerative diseases in animal models [

44,

45]. Analysis of data from randomized controlled clinical trials confirms that pharmabiotic can ameliorate manifestations of nigral dopaminergic neuronal death and motor deficits, regulate dopamine pathways in people with Parkinson’s disease [

46,

47]. However, the specific components of bacterial cells that act as active factors and the mechanism of their action remain unknown. Previously,

L. fermentum U-21 was shown to act as pharmabiotic, which can reduce pro-inflammatory changes in rat models of Parkinson’s disease [

48]. Our results suggest that the anti-parkinsonian properties of the

L. fermentum U-21 strain are determined, in part, by the ClpL protein and its ability to refold protein aggregates.

Measurements of chaperone activity of ClpL with use of luciferases in vitro and in vivo was supported by RSF 22-14-00124.

Search of possible applications of L. fermentum U-21 strain was supported by the Ministry of Science and Higher Education of the RF, project FSMF-2023-0010.

L. fermentum clpL gene search and cloning, and spent L. fermentum culture medium preparation and proteome analysis, conducted in the Vavilov Institute of General Genetics RAS, were funded within the framework of the state task 122022600163-7.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

References

- Katayama, Y.; Gottesman, S.; Pumphrey, J.; Rudikoff, S.; Clark, W.P.; Maurizi, M.R. The Two-Component, ATP-Dependent Clp Protease of Escherichia Coli. Purification, Cloning, and Mutational Analysis of the ATP-Binding Component. Journal of Biological Chemistry 1988, 263, 15226–15236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kitagawa, M.; Wada, C.; Yoshioka, S.; Yura, T. Expression of ClpB, an Analog of the ATP-Dependent Protease Regulatory Subunit in Escherichia Coli, Is Controlled by a Heat Shock Sigma Factor (Sigma 32). J Bacteriol 1991, 173, 4247–4253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoskins, J.R.; Sharma, S.; Sathyanarayana, B.K.; Wickner, S. Clp ATPases and Their Role in Protein Unfolding and Degradation. Adv Protein Chem 2001, 59, 413–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wawrzynow, A.; Wojtkowiak, D.; Marszalek, J.; Banecki, B.; Jonsen, M.; Graves, B.; Georgopoulos, C.; Zylicz, M. The ClpX Heat-Shock Protein of Escherichia Coli, the ATP-Dependent Substrate Specificity Component of the ClpP-ClpX Protease, Is a Novel Molecular Chaperone. EMBO J 1995, 14, 1867–1877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wickner, S.; Gottesman, S.; Skowyra, D.; Hoskins, J.; McKenney, K.; Maurizi, M.R. A Molecular Chaperone, ClpA, Functions like DnaK and DnaJ. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1994, 91, 12218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weber-Ban, E.U.; Reid, B.G.; Miranker, A.D.; Horwich, A.L. Global Unfolding of a Substrate Protein by the Hsp100 Chaperone ClpA. Nature 1999, 401, 90–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoskins, J.R.; Singh, S.K.; Maurizi, M.R.; Wickner, S. Protein Binding and Unfolding by the Chaperone ClpA and Degradation by the Protease ClpAP. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2000, 97, 8892–8897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gottesman, S.; Wickner, S.; Maurizi, M.R. Protein Quality Control: Triage by Chaperones and Proteases. Genes Dev 1997, 11, 815–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Motohashi, K.; Watanabe, Y.; Yohda, M.; Yoshida, M. Heat-Inactivated Proteins Are Rescued by the DnaK.J-GrpE Set and ClpB Chaperones. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1999, 96, 7184–7189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zavilgelsky, G.B.; Kotova, V.Y.; Mazhul’, M.M.; Manukhov, I. V. Role of Hsp70 (DnaK-DnaJ-GrpE) and Hsp100 (ClpA and ClpB) Chaperones in Refolding and Increased Thermal Stability of Bacterial Luciferases in Escherichia Coli Cells. Biochemistry (Moscow) 2002, 67, 986–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, G.; Lee, S.G.; Han, S.; Jung, J.; Jeong, H.S.; Hyun, J. kyung; Rhee, D.K.; Kim, H.M.; Lee, S. ClpL Is a Functionally Active Tetradecameric AAA+ Chaperone, Distinct from Hexameric/Dodecameric Ones. The FASEB Journal 2020, 34, 14353–14370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Namy, O.I.; éle Mock, M.; és Fouet, A. Co-Existence of ClpB and ClpC in the Bacillaceae. FEMS Microbiol Lett 1999, 173, 297–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Breton, J.; Legrand, R.; Akkermann, K.; Järv, A.; Harro, J.; Déchelotte, P.; Fetissov, S.O. Elevated Plasma Concentrations of Bacterial ClpB Protein in Patients with Eating Disorders. Int J Eat Disord 2016, 49, 805–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dominique, M.; Breton, J.; Guérin, C.; Bole-Feysot, C.; Lambert, G.; Déchelotte, P.; Fetissov, S. Effects of Macronutrients on the In Vitro Production of ClpB, a Bacterial Mimetic Protein of α-MSH and Its Possible Role in Satiety Signaling. Nutrients 2019, Vol. 11, Page 2115 2019, 11, 2115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tennoune, N.; Chan, P.; Breton, J.; Legrand, R.; Chabane, Y.N.; Akkermann, K.; Järv, A.; Ouelaa, W.; Takagi, K.; Ghouzali, I.; et al. Bacterial ClpB Heat-Shock Protein, an Antigen-Mimetic of the Anorexigenic Peptide α-MSH, at the Origin of Eating Disorders. Translational Psychiatry 2014 4:10 2014, 4, e458–e458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soloveva, I. V.; Novikova, N.A.; Tochilina, A.G.; Belova, I. V.; Kashnikov, A.Y.; Sashina, T.A.; Zhirnov, V.A.; Molodtsova, S.B. The Probiotic Strain Lactobacillus Fermentum 39: Biochemical Properties, Genomic Features, and Antiviral Activity. Microbiology (Russian Federation) 2021, 90, 219–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Sojo, M.J.; Ruiz-Malagón, A.J.; Rodríguez-Cabezas, M.E.; Gálvez, J.; Rodríguez-Nogales, A. Limosilactobacillus Fermentum CECT5716: Mechanisms and Therapeutic Insights. Nutrients 2021, 13, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Luna Freire, M.O.; Cruz Neto, J.P.R.; de Albuquerque Lemos, D.E.; de Albuquerque, T.M.R.; Garcia, E.F.; de Souza, E.L.; de Brito Alves, J.L. Limosilactobacillus Fermentum Strains as Novel Probiotic Candidates to Promote Host Health Benefits and Development of Biotherapeutics: A Comprehensive Review. Probiotics and Antimicrobial Proteins 2024 2024, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marsova, M.; Abilev, S.; Poluektova, E.; Danilenko, V. A Bioluminescent Test System Reveals Valuable Antioxidant Properties of Lactobacillus Strains from Human Microbiota. World J Microbiol Biotechnol 2018, 34, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsova, M.; Poluektova, E.; Odorskaya, M.; Ambaryan, A.; Revishchin, A.; Pavlova, G.; Danilenko, V. Protective Effects of Lactobacillus Fermentum U-21 against Paraquat-Induced Oxidative Stress in Caenorhabditis Elegans and Mouse Models. World J Microbiol Biotechnol 2020, 36, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danilenko, V.N.; Stavrovskaya, A. V.; Voronkov, D.N.; Gushchina, A.S.; Marsova, M. V.; Yamshchikova, N.G.; Ol’shansky, А.S.; Ivanov, M. V.; Illarioshkin, S.N. The Use of a Pharmabiotic Based on the Lactobacillus Fermentum U-21 Strain to Modulate the Neurodegenerative Process in an Experimental Model of Parkinson Disease. Annals of Clinical and Experimental Neurology 2020, 14, 62–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stavrovskaya, A. V.; Danilenko, V.N.; Voronkov, D.N.; Gushchina, A.S.; Marsova, M. V.; Olshansky, A.S.; Yamshikova, N.G.; Illarioshkin, S.N. Pharmabiotic Based on Lactobacillus Fermentum Strain U-21 Modulates the Toxic Effect of 1-Methyl-4-Phenyl-1,2,3,6-Tetrahydropyridine as Parkinsonism Inducer in Mice. Hum Physiol 2021, 47, 891–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poluektova, E.U.; Mavletova, D.A.; Odorskaya, M. V.; Marsova, M. V.; Klimina, K.M.; Koshenko, T.A.; Yunes, R.A.; Danilenko, V.N. Comparative Genomic, Transcriptomic, and Proteomic Analysis of the Limosilactobacillus Fermentum U-21 Strain Promising for the Creation of a Pharmabiotic. Russ J Genet 2022, 58, 1079–1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gottesman, S.; Roche, E.; Zhou, Y.N.; Sauer, R.T. The ClpXP and ClpAP Proteases Degrade Proteins with Carboxy-Terminal Peptide Tails Added by the SsrA-Tagging System. Genes Dev 1998, 12, 1338–1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bazhenov, S.; Novoyatlova, U.; Scheglova, E.; Fomin, V.; Khrulnova, S.; Melkina, O.; Chistyakov, V.; Manukhov, I. Influence of the LuxR Regulatory Gene Dosage and Expression Level on the Sensitivity of the Whole-Cell Biosensor to Acyl-Homoserine Lactone. Biosensors (Basel) 2021, 11, 166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zavil’gel’skiĭ, GB.; Kotova VIu; Manukhov IV. A Kinetic Method of Determining the Frequency of Homologous Recombination of Plasmids in Escherichia Coli Cells. Mol Biol (Mosk) 1994, 28, 1299–1307. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zavilgelsky GB; Zarubina AP; Manukhov IV Sequencing and Comparative Analysis of the Lux-Operon of Photorhabdus Luminescens Strain ZM1: ERIC Elements as Putative Recombination Spots. Mol Biol 2002, 36, 792–804. [CrossRef]

- Sambrook Joseph; Maccallum P; Russell David William. In Molecular Cloning A Laboratory Manual; Molecular Cloning A Laboratory Manual, 2001.

- Gibson, D.G.; Young, L.; Chuang, R.Y.; Venter, J.C.; Hutchison, C.A.; Smith, H.O. Enzymatic Assembly of DNA Molecules up to Several Hundred Kilobases. Nature Methods 2009 6:5 2009, 6, 343–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazarov, P.A.; Khrulnova, S.A.; Kessenikh, A.G.; Novoyatlova, U.S.; Kuznetsova, S.B.; Bazhenov, S. V.; Sorochkina, A.I.; Karakozova, M. V.; Manukhov, I. V. Observation of Cytotoxicity of Phosphonium Derivatives Is Explained: Metabolism Inhibition and Adhesion Alteration. Antibiotics 2023, Vol. 12, Page 720 2023, 12, 720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamura, K.; Stecher, G.; Kumar, S. MEGA11: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis Version 11. Mol Biol Evol 2021, 38, 3022–3027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.S.; Kwon, H.Y.; Tran, T.D.H.; Choi, M.H.; Jung, S.H.; Lee, S.; Briles, D.E.; Rhee, D.K. ClpL Is a Chaperone without Auxiliary Factors. FEBS Journal 2015, 282, 1352–1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bohl, V.; Hollmann, N.M.; Melzer, T.; Katikaridis, P.; Meins, L.; Simon, B.; Flemming, D.; Sinning, I.; Hennig, J.; Mogk, A. The Listeria Monocytogenes Persistence Factor ClpL Is a Potent Stand-Alone Disaggregase. Elife 2024, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rotanova, T. V.; Andrianova, A.G.; Kudzhaev, A.M.; Li, M.; Botos, I.; Wlodawer, A.; Gustchina, A. New Insights into Structural and Functional Relationships between LonA Proteases and ClpB Chaperones. FEBS Open Bio 2019, 9, 1536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kotova, V.Y.; Manukhov, I. V.; Melkina, O.E.; Zavilgelsky, G.B. Mutation ClpA::Kan of the Gene for an Hsp100 Family Chaperone Impairs the DnaK-Dependent Refolding of Proteins in Escherichia Coli. Mol Biol 2008, 42, 906–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zavilgelsky, G.B.; Kotova, V.Y.; Mazhul’, M.M.; Manukhov, I. V. The Effect of Clp Proteins on DnaK-Dependent Refolding of Bacterial Luciferases. Mol Biol 2004, 38, 427–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, D.C.; Huang, X.F.; Novel, G.; Novel, M. Two Genes Present on a Transposon-like Structure in Lactococcus Lactis Are Involved in a Clp-Family Proteolytic Activity. Mol Microbiol 1993, 7, 957–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwon, H.Y.; Kim, S.W.; Choi, M.H.; Ogunniyi, A.D.; Paton, J.C.; Park, S.H.; Pyo, S.N.; Rhee, D.K. Effect of Heat Shock and Mutations in ClpL and ClpP on Virulence Gene Expression in Streptococcus Pneumoniae. Infect Immun 2003, 71, 3757–3765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tao, L.; Biswas, I. ClpL Is Required for Folding of CtsR in Streptococcus Mutans. J Bacteriol 2013, 195, 576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, A.N.; Khan, R.H. Protein Misfolding and Related Human Diseases: A Comprehensive Review of Toxicity, Proteins Involved, and Current Therapeutic Strategies. Int J Biol Macromol 2022, 223, 143–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, A.C.; Callaerts-Vegh, Z.; Nunes, A.F.; Rodrigues, C.M.P.; D’Hooge, R. Tauroursodeoxycholic Acid (TUDCA) Supplementation Prevents Cognitive Impairment and Amyloid Deposition in APP/PS1 Mice. Neurobiol Dis 2013, 50, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, Z.L.; Brito, R.M.M. Amyloid Disassembly: What Can We Learn from Chaperones? Biomedicines 2022, Vol. 10, Page 3276 2022, 10, 3276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Auburger, G.; Key, J.; Gispert, S. The Bacterial ClpXP-ClpB Family Is Enriched with RNA-Binding Protein Complexes. Cells 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ojha, S.; Patil, N.; Jain, M.; Kole, C.; Kaushik, P. Probiotics for Neurodegenerative Diseases: A Systemic Review. Microorganisms 2023, Vol. 11, Page 1083 2023, 11, 1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dhyani, P.; Goyal, C.; Dhull, S.B.; Chauhan, A.K.; Singh Saharan, B.; Harshita; Duhan, J.S.; Goksen, G. Psychobiotics for Mitigation of Neuro-Degenerative Diseases: Recent Advancements. In Mol Nutr Food Res; 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peña-Díaz, S.; García-Pardo, J.; Ventura, S. Development of Small Molecules Targeting α-Synuclein Aggregation: A Promising Strategy to Treat Parkinson’s Disease. Pharmaceutics 2023, Vol. 15, Page 839 2023, 15, 839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chu, C.; Yu, L.; Li, Y.; Guo, H.; Zhai, Q.; Chen, W.; Tian, F. Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials of the Effects of Probiotics in Parkinson’s Disease. Food Funct 2023, 14, 3406–3422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stavrovskaya, A. V; Voronkov, D.N.; Marsova, M. V; Olshansky, A.S.; Gushchina, A.S.; Danilenko, V.N.; Illarioshkin, S.N. Effects of the Pharmabiotic U-21 in a Combined Neuroinflammatory Model of Parkinson’s Disease in Rats. Bull Exp Biol Med 2024, 177, 193–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).