Submitted:

18 August 2025

Posted:

20 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- First, it is recommended to optimize several operational production parameters such as the incubation temperature, shaking speed for aeration of the cell cultures, incubation time, concentration of inducer molecule for transcript expression, medium composition (f.i. presence of solubility enhancing additives, considering auto-induction medium), culture volume and cell lysis method [14,35]. In practice, it is advised to reduce the temperature during the induction because this reduces the protein biosynthesis rate and increases the chance of obtaining a soluble POI;

- Second, reconsideration of the expression construct may be advised. Researchers should take codon bias into account and optimize/harmonize the coding sequence. Several online tools make adjustments to the amino acid sequence, including deep learning and artificial intelligence, are available [36,37,38]. In addition, if non-optimized sequences are used in a prokaryotic system such as E. coli, the host strain Rosetta® could be considered. This strain is engineered with additional transfer-RNAs for enhancing translation of eukaryotic proteins with ‘rare codons’ [39]. Next to codon bias, the addition of solubility tags may be considered. Widely used solubility tags include the maltose-binding protein (MBP; 40 kDa), glutathione S-transferase (GST; 26 kDa) and thioredoxin (TRX; 12 kDa) [40]. Successful protein production is, however, not guaranteed when employing solubility tags. Several parameters exert an effect on the solubility of the new fusion protein [41,42], for instance the positioning (C or N terminal) of the solubility tag, the size of the tag, the number of tags … It should be taken into account that fusion with a large solubility tag may affect protein activity by sterically shielding active states. Finally, selection of a proper solubility tag and positioning towards the protein domain of interest often needs to be established and/or optimized empirically;

- Another option for prokaryotic protein production is to use modified host strains. Several modified hosts are available that may accommodate the researchers’ individual needs and are often equipped with additional chaperones. These chaperones are able to recognize unproperly folded proteins and prevent them from aggregation. Typical chaperons include the heat-shock proteins and have been engineered in strains to circumvent issues with protein aggregation [43], and may assist in proper protein folding [44]. The E. coli ArcticExpress® strain coproduces the Cpn10 and Cpn60 chaperonins from Oleispira antarctica, allowing protein production at lowered temperatures (4-10°C), potentially accommodating a lower protein biosynthesis rate and therefore limiting the risk of protein aggregation and IB formation [45]. Another example is the E. coli SHuffle® strain, which is equipped with the disulfide bond isomerase chaperone, allowing formation of disulfide bridges in the cytosol [46], hereby increasing solubility of proteins that require disulfide bridges [47];

- Next to usage of engineered host strains, it could be considered to co-express molecular chaperones that are situated upstream of downstream from the native gene of interest. There is sufficient evidence that these chaperones, mostly heat-shock proteins, are co-expressed under native conditions to ensure proper POI folding [48];

- A frequently utilized approach is to produce the POI in IBs and perform subsequent protein unfolding and refolding [22]. Protein refolding is controversial since the refolding step does not always restore the native folding, might trap the protein in a non-native state and could render it inactive. Protein refolding protocols require extensive optimization and are highly empirical [49,50,51]. Nevertheless, the performance of refolding strategies has been demonstrated may times before [20];

- Changing the expression host may be considered, since the success of recombinant protein production is for a large part determined by the host used. A study producing 29 human proteins in E. coli and P. pastoris demonstrated that all of the POI were soluble when using P. pastoris, compared to only 31% when using E. coli [52]. Eventually, cell-free production systems (CFPS) or phage/yeast display may be opted when traditional cell-based strategies are not successful [53]. CFPS systems make use of cell lysates and contain all the necessary component for protein synthesis. Both prokaryotic CFPS (f.i. cell lysates of E. coli, archaeans) and eukaryotic CFPS (f.i. tobacco Bright Yellow-2 lysates, rabbit reticulocyte lysates) systems exist, but similar to conventional recombinant protein production, the CFPS should be chosen carefully, taking into account the same considerations as mentioned above. Not unimportantly, CFPS may be confronted with reduced yields [54,55]. Page/yeast display has the advantage that the POI is produced by the host and presented at the cell surface, thereby removing the need for tedious or laborious optimization of protein production and purification. However, yeast/phage display may be confronted with similar issues a with traditional recombinant protein production, as the same constraints regarding non-native expression remain valid;

- A final option is considering to produce a homolog of the POI, as it was shown before that the success of recombinant protein production may vary between homologues [56].

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Characteristics of OsAPSE

2.2. Expression in E. coli Leads to Mostly Insoluble Proteins

2.2.1. Effect of Codon Optimization

2.2.2. Utilization of E. coli Strains Capable of Synthesizing Disulfide Bridges

2.2.3. Exploration of Protein Refolding

2.2.4. Effect of Codon Harmonization and Mutational Variants

| WT | Variant 1 | Variant 2 | Variant 3 | Variant 4 | Variant 5 | Variant 6 | Variant 7 | Variant 8 | Variant 9 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sequence identity compared to OsAPSE | 100 | 98.7 | 97.8 | 97.7 | 96.5 | 95.7 | 95.5 | 94.6 | 93.5 | 92.8 |

| Number of mutated amino acid residues | 0 | 8 | 14 | 15 | 23 | 28 | 29 | 35 | 42 | 47 |

| RMSD (Å) compared to OsAPSE | 0 | 0.0684 | 0.0825 | 0.0881 | 0.0908 | 0.1017 | 0.1030 | 0.0963 | 0.1081 | 0.1113 |

| POI produced recombinantly? | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | No |

| Soluble POI? | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

2.2.5. Usage of Solubility Tags

2.2.6. Enzymatic Activity of Soluble GH27_OsAPSE and Refolded OsAPSE

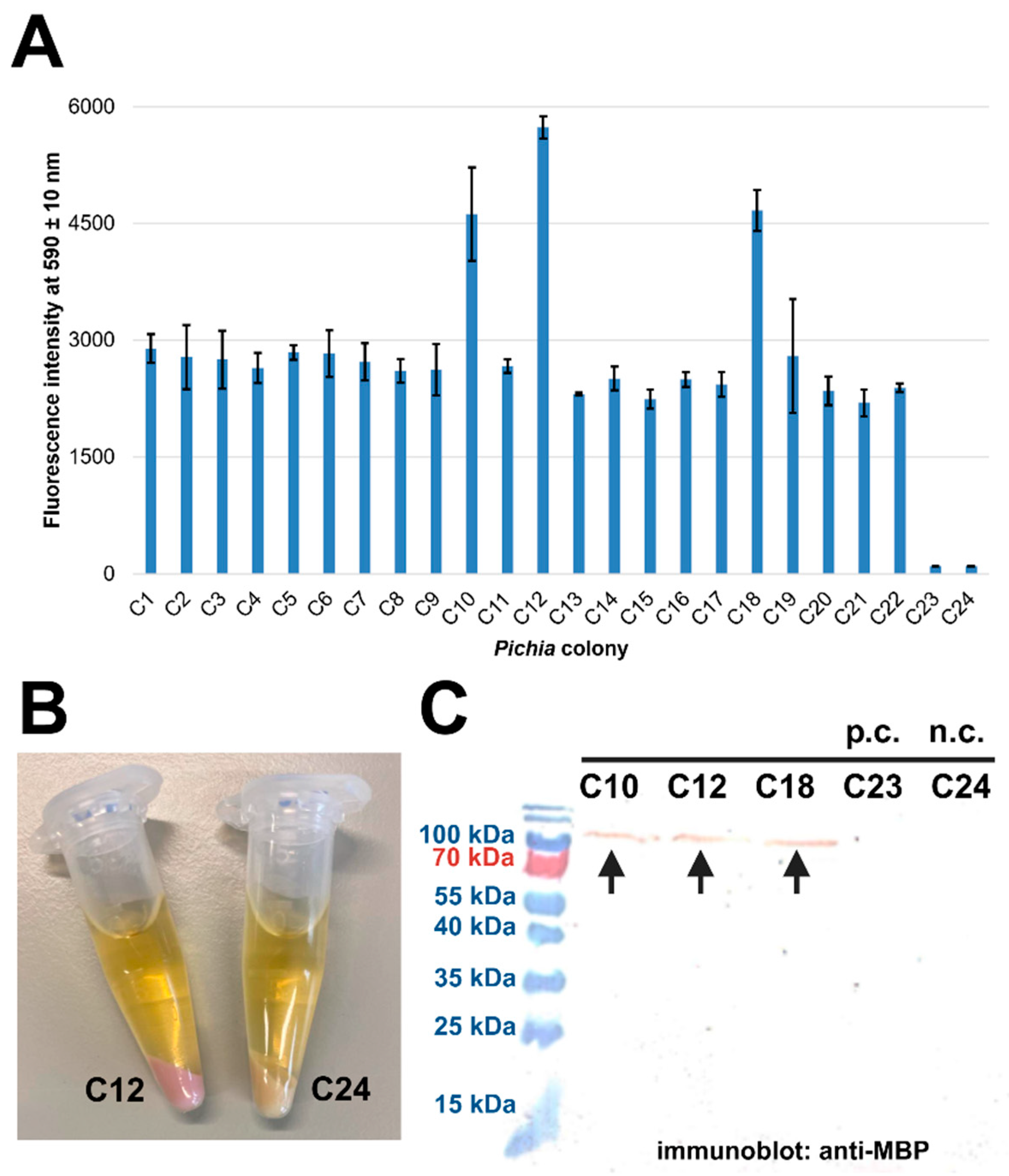

2.3. Expression in P. pastoris Yields Inactive Proteins of Interest

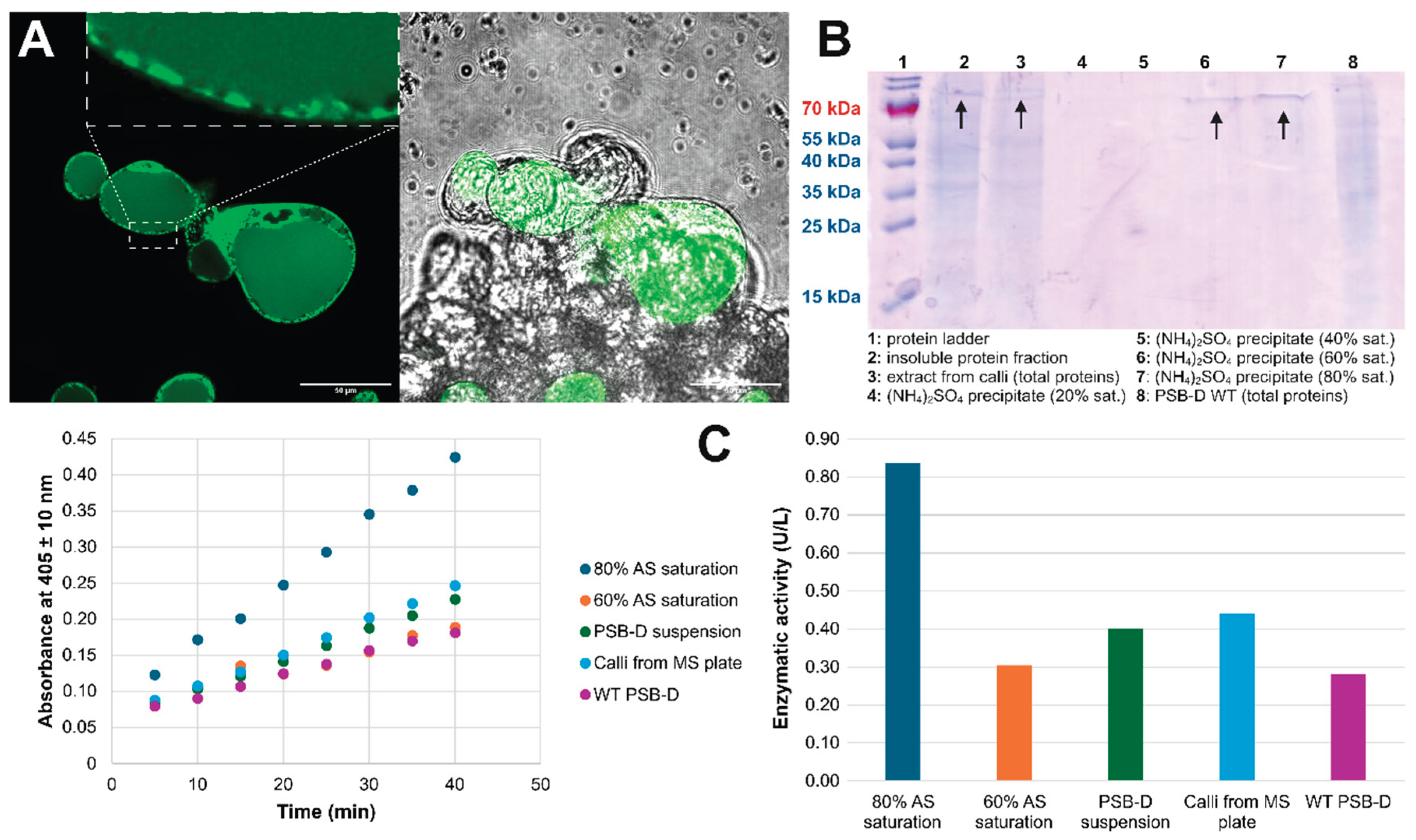

2.4. Expression in A. thaliana PSB-D Cell Cultures Results in Low Yields

3. Conclusions

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Construct Design and Host Transformation

4.2. Protein Production and Extraction

4.2.1. Escherichia Coli

4.2.2. Pichia Pastoris

4.2.3. Arabidopsis Thaliana PSB-D Cell Cultures

4.3. Protein Analysis

4.3.1. Protein Concentration

4.3.2. SDS-PAGE and Western Blot

4.4. Downstream Analyses

4.4.1. Protein Refolding

4.4.2. Enzymatic Activity Assays

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AGAL | α-D-Galactopyranosidase |

| BSA | Bovine Serum Albumin |

| CAI | Codon Adaptation Index |

| CFPS | Cell-Free Production System |

| EGFP | Enhanced Green Fluorescent Protein |

| ER | Endoplasmic Reticulum |

| GST | Glutathione S-Transferase |

| IB | Inclusion Body |

| LB | Lysogeny Broth |

| MBP | Maltose-Binding Protein |

| MSMO | Murashige and Skoog medium with Minimal Organics |

| OD600 | Optical Density at 600 nm |

| PMSF | Phenyl Methyl Sulfonyl Fluoride |

| pNP-α-D-Galp | p-4-nitrophenol-α-D-Galactopyranoside |

| POI | Protein Of Interest |

| PROSS | Protein Repair One-Stop Shop |

| PSB-D | Plant Systems Biology – Dark |

| PTM | Post-Translational Modification |

| RSCU | Relative Synonymous Codon Usage |

| RFP | Red Fluorescent Protein |

| RMSD | Root-Mean Square Deviation |

| TCA | Trichloroacetic acid |

| TEV | Tobacco Etch Virus |

| TGH | Tris-Glycerol-HEPES |

| TRX | Thioredoxin |

References

- Mulder, G. Sur La Composition de Quelques Substances Animales. Bulletin des Sciences Physiques et Naturelles en Néerlande 1838, 129–151. [Google Scholar]

- Hartley, H. Origin of the Word “Protein”. Nature 1951, 168, 244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parisi, G.; Palopoli, N.; Tosatto, S.C.E.; Fornasari, M.S.; Tompa, P. “Protein” No Longer Means What It Used To. Current Research in Structural Biology 2021, 3, 146–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corsetti, G.; Pasini, E.; Scarabelli, T.M.; Romano, C.; Singh, A.; Scarabelli, C.C.; Dioguardi, F.S. Importance of Energy, Dietary Protein Sources, and Amino Acid Composition in the Regulation of Metabolism: An Indissoluble Dynamic Combination for Life. Nutrients 2024, 16, 2417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puetz, J.; Wurm, F.M. Recombinant Proteins for Industrial versus Pharmaceutical Purposes: A Review of Process and Pricing. 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Sewalt, V.; Shanahan, D.; Gregg, L.; La Marta, J.; Carrillo, R. The Generally Recognized as Safe (GRAS) Process for Industrial Microbial Enzymes. Industrial Biotechnology 2016, 12, 295–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francis, D.M.; Page, R. Strategies to Optimize Protein Expression in E. Coli. CP Protein Science 2010, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balen, B.; Krsnik-Rasol, M. N-Glycosylation of Recombinant Therapeutic Glycoproteins in Plant Systems. 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Karbalaei, M.; Rezaee, S.A.; Farsiani, H. Pichia Pastoris : A Highly Successful Expression System for Optimal Synthesis of Heterologous Proteins. Journal Cellular Physiology 2020, 235, 5867–5881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, T.; Liu, H.; Lv, B.; Li, C. Regulating Strategies for Producing Carbohydrate Active Enzymes by Filamentous Fungal Cell Factories. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2020, 8, 691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schütz, A.; Bernhard, F.; Berrow, N.; Buyel, J.F.; Ferreira-da-Silva, F.; Haustraete, J.; van den Heuvel, J.; Hoffmann, J.-E.; de Marco, A.; Peleg, Y.; et al. A Concise Guide to Choosing Suitable Gene Expression Systems for Recombinant Protein Production. STAR Protocols 2023, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.M.; Hammarén, H.M.; Savitski, M.M.; Baek, S.H. Control of Protein Stability by Post-Translational Modifications. Nat Commun 2023, 14, 201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Overton, T.W. Recombinant Protein Production in Bacterial Hosts. Drug Discovery Today 2014, 19, 590–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhatwa, A.; Wang, W.; Hassan, Y.I.; Abraham, N.; Li, X.-Z.; Zhou, T. Challenges Associated With the Formation of Recombinant Protein Inclusion Bodies in Escherichia Coli and Strategies to Address Them for Industrial Applications. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2021, 9, 630551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrer-Miralles, N.; Saccardo, P.; Corchero, J.L.; Garcia-Fruitós, E. Recombinant Protein Production and Purification of Insoluble Proteins. In Insoluble Proteins; Garcia Fruitós, E., Arís Giralt, A., Eds.; Methods in Molecular Biology; Springer US: New York, NY, 2022; Volume 2406, pp. 1–31. ISBN 978-1-07-161858-5. [Google Scholar]

- Kramer, R.M.; Shende, V.R.; Motl, N.; Pace, C.N.; Scholtz, J.M. Toward a Molecular Understanding of Protein Solubility: Increased Negative Surface Charge Correlates with Increased Solubility. Biophysical Journal 2012, 102, 1907–1915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muntau, A.C.; Leandro, J.; Staudigl, M.; Mayer, F.; Gersting, S.W. Innovative Strategies to Treat Protein Misfolding in Inborn Errors of Metabolism: Pharmacological Chaperones and Proteostasis Regulators. J Inherit Metab Dis 2014, 37, 505–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onuchic, J.N.; Luthey-Schulten, Z.; Wolynes, P.G. Theory of Protein Folding: The Energy Landscape Perspective. Annu. Rev. Phys. Chem 1997, 48, 545–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finkelstein, A.V.; Bogatyreva, N.S.; Ivankov, D.N.; Garbuzynskiy, S.O. Protein Folding Problem: Enigma, Paradox, Solution. Biophys Rev 2022, 14, 1255–1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Fruitós, E.; González-Montalbán, N.; Morell, M.; Vera, A.; Ferraz, R.M.; Arís, A.; Ventura, S.; Villaverde, A. Aggregation as Bacterial Inclusion Bodies Does Not Imply Inactivation of Enzymes and Fluorescent Proteins. Microb Cell Fact 2005, 4, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores, S.S.; Nolan, V.; Perillo, M.A.; Sánchez, J.M. Superactive β-Galactosidase Inclusion Bodies. Colloids and Surfaces B: Biointerfaces 2019, 173, 769–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Upadhyay, V.; Upadhyay, A.K.; Singh, S.M.; Panda, A.K. Protein Recovery from Inclusion Bodies of Escherichia Coli Using Mild Solubilization Process. Microb Cell Fact 2015, 14, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallejo, L.F.; Rinas, U. Strategies for the Recovery of Active Proteins through Refolding of Bacterial Inclusion Body Proteins. Microb Cell Fact 2004, 3, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, C.-Y.; Majewska, N.I.; Wang, Q.; Paul, J.T.; Betenbaugh, M.J. SnapShot: N-Glycosylation Processing Pathways across Kingdoms. Cell 2017, 171, 258–258.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joshi, H.J.; Narimatsu, Y.; Schjoldager, K.T.; Tytgat, H.L.P.; Aebi, M.; Clausen, H.; Halim, A. SnapShot: O-Glycosylation Pathways across Kingdoms. Cell 2018, 172, 632–632.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sørensen, H.P.; Mortensen, K.K. Soluble Expression of Recombinant Proteins in the Cytoplasm of Escherichia Coli. Microb Cell Fact 2005, 4, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Alarcón, D.; Blanco-Labra, A.; García-Gasca, T. Expression of Lectins in Heterologous Systems. IJMS 2018, 19, 616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujimoto, Z.; Kaneko, S.; Momma, M.; Kobayashi, H.; Mizuno, H. Crystal Structure of Rice α-Galactosidase Complexed with D-Galactose. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2003, 278, 20313–20318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meuris, L.; Santens, F.; Elson, G.; Festjens, N.; Boone, M.; Dos Santos, A.; Devos, S.; Rousseau, F.; Plets, E.; Houthuys, E.; et al. GlycoDelete Engineering of Mammalian Cells Simplifies N-Glycosylation of Recombinant Proteins. Nat Biotechnol 2014, 32, 485–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piron, R.; Santens, F.; De Paepe, A.; Depicker, A.; Callewaert, N. Using GlycoDelete to Produce Proteins Lacking Plant-Specific N-Glycan Modification in Seeds. Nat Biotechnol 2015, 33, 1135–1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habibi, N.; Mohd Hashim, S.Z.; Norouzi, A.; Samian, M.R. A Review of Machine Learning Methods to Predict the Solubility of Overexpressed Recombinant Proteins in Escherichia Coli. BMC Bioinformatics 2014, 15, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhandari, B.K.; Gardner, P.P.; Lim, C.S. Solubility-Weighted Index: Fast and Accurate Prediction of Protein Solubility. Bioinformatics 2020, 36, 4691–4698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez-González, M.; Farías, C.; Tello, S.; Pérez-Etcheverry, D.; Romero, A.; Zúñiga, R.; Ribeiro, C.H.; Lorenzo-Ferreiro, C.; Molina, M.C. Optimization of Culture Conditions for the Expression of Three Different Insoluble Proteins in Escherichia Coli. Sci Rep 2019, 9, 16850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mital, S.; Christie, G.; Dikicioglu, D. Recombinant Expression of Insoluble Enzymes in Escherichia Coli: A Systematic Review of Experimental Design and Its Manufacturing Implications. Microb Cell Fact 2021, 20, 208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atroshenko, D.L.; Sergeev, E.P.; Golovina, D.I.; Pometun, A.A. Additivities for Soluble Recombinant Protein Expression in Cytoplasm of Escherichia Coli. Fermentation 2024, 10, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldenzweig, A.; Goldsmith, M.; Hill, S.E.; Gertman, O.; Laurino, P.; Ashani, Y.; Dym, O.; Unger, T.; Albeck, S.; Prilusky, J.; et al. Automated Structure- and Sequence-Based Design of Proteins for High Bacterial Expression and Stability. Molecular Cell 2016, 63, 337–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mignon, C.; Mariano, N.; Stadthagen, G.; Lugari, A.; Lagoutte, P.; Donnat, S.; Chenavas, S.; Perot, C.; Sodoyer, R.; Werle, B. Codon Harmonization – Going beyond the Speed Limit for Protein Expression. FEBS Letters 2018, 592, 1554–1564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Listov, D.; Goverde, C.A.; Correia, B.E.; Fleishman, S.J. Opportunities and Challenges in Design and Optimization of Protein Function. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2024, 25, 639–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Novy, R.; Drott, D.; Yaeger, K.; Mierendorf, R. inNovations; 2001; pp. 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Bell, M.R.; Engleka, M.J.; Malik, A.; Strickler, J.E. To Fuse or Not to Fuse: What Is Your Purpose? Protein Science 2013, 22, 1466–1477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sommer, B.; Friehs, K.; Flaschel, E.; Reck, M.; Stahl, F.; Scheper, T. Extracellular Production and Affinity Purification of Recombinant Proteins with Escherichia Coli Using the Versatility of the Maltose Binding Protein. Journal of Biotechnology 2009, 140, 194–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raran-Kurussi, S.; Keefe, K.; Waugh, D.S. Positional Effects of Fusion Partners on the Yield and Solubility of MBP Fusion Proteins. Protein Expression and Purification 2015, 110, 159–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piette, F.; Struvay, C.; Feller, G. The Protein Folding Challenge in Psychrophiles: Facts and Current Issues. Environmental Microbiology 2011, 13, 1924–1933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saibil, H. Chaperone Machines for Protein Folding, Unfolding and Disaggregation. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2013, 14, 630–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrer, M.; Chernikova, T.N.; Timmis, K.N.; Golyshin, P.N. Expression of a Temperature-Sensitive Esterase in a Novel Chaperone-Based Escherichia Coli Strain. Appl Environ Microbiol 2004, 70, 4499–4504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lobstein, J.; Emrich, C.A.; Jeans, C.; Faulkner, M.; Riggs, P.; Berkmen, M. SHuffle, a Novel Escherichia Coli Protein Expression Strain Capable of Correctly Folding Disulfide Bonded Proteins in Its Cytoplasm. Microb Cell Fact 2012, 11, 753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kauzmann, W.; Douglas, R.G. The Effect of Disulfide Bonding on the Solubility of Unfolded Serum Albumin in Salt Solutions. Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics 1956, 65, 106–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, L.; Gao, H.; Zhong, Y.; Liu, Y.; Cao, Y.; Yi, J.; Huang, X.; Wen, C.; Tong, R.; Pan, Z.; et al. Molecular Chaperones HSP40, HSP70, STIP1, and HSP90 Are Involved in Stabilization of Cx43. Cytotechnology 2023, 75, 207–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, G.-Q.; Gouaux, E. Overexpression of a Glutamate Receptor (GluR2) Ligand Binding Domain in Escherichia Coli : Application of a Novel Protein Folding Screen. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1997, 94, 13431–13436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, N.; Lencastre, A.D.; Gouaux, E. A New Protein Folding Screen: Application to the Ligand Binding Domains of a Glutamate and Kainate Receptor and to Lysozyme and Carbonic Anhydrase. Protein Science 1999, 8, 1475–1483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vincentelli, R.; Canaan, S.; Campanacci, V.; Valencia, C.; Maurin, D.; Frassinetti, F.; Scappucini-Calvo, L.; Bourne, Y.; Cambillau, C.; Bignon, C. High-throughput Automated Refolding Screening of Inclusion Bodies. Protein Science 2004, 13, 2782–2792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lueking, A.; Holz, C.; Gotthold, C.; Lehrach, H.; Cahill, D. A System for Dual Protein Expression in Pichia Pastoris and Escherichia Coli. Protein Expression and Purification 2000, 20, 372–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, S.-L.; DaSilva, N.A.; Chen, W. Functional Display of Complex Cellulosomes on the Yeast Surface via Adaptive Assembly. ACS Synth. Biol. 2013, 2, 14–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harbers, M. Wheat Germ Systems for Cell-free Protein Expression. FEBS Letters 2014, 588, 2762–2773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zemella, A.; Thoring, L.; Hoffmeister, C.; Kubick, S. Cell-Free Protein Synthesis: Pros and Cons of Prokaryotic and Eukaryotic Systems. ChemBioChem 2015, 16, 2420–2431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morel, N.; Massoulié, J. Comparative Expression of Homologous Proteins. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2000, 275, 7304–7312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Coninck, T.; Verbeke, I.; Rougé, P.; Desmet, T.; Van Damme, E.J.M. OsAPSE Modulates Non-Covalent Interactions between Arabinogalactan Protein O-Glycans and Pectin in Rice Cell Walls. Frontiers in Plant Science 2025, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imaizumi, C.; Tomatsu, H.; Kitazawa, K.; Yoshimi, Y.; Shibano, S.; Kikuchi, K.; Yamaguchi, M.; Kaneko, S.; Tsumuraya, Y.; Kotake, T. Heterologous Expression and Characterization of an Arabidopsis β-L-Arabinopyranosidase and α-D-Galactosidases Acting on β-L-Arabinopyranosyl Residues. Journal of Experimental Botany 2017, 68, 4651–4661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujimoto, Z. Structure and Function of Carbohydrate-Binding Module Families 13 and 42 of Glycoside Hydrolases, Comprising a β-Trefoil Fold. Bioscience, Biotechnology, and Biochemistry 2013, 77, 1363–1371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, M.E.; Drickamer, K. Convergent and Divergent Mechanisms of Sugar Recognition across Kingdoms. Current Opinion in Structural Biology 2014, 28, 14–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Coninck, T.; Gippert, G.P.; Henrissat, B.; Desmet, T.; Van Damme, E.J.M. Investigating Diversity and Similarity between CBM13 Modules and Ricin-B Lectin Domains Using Sequence Similarity Networks. BMC Genomics 2024, 25, 643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boissinot, M.; Karnas, S.; Lepock, J.R.; Cabelli, D.E.; Tainer, J.A.; Getzoff, E.D.; Hallewell, R.A. Function of the Greek Key Connection Analysed Using Circular Permutants of Superoxide Dismutase. The EMBO Journal 1997, 16, 2171–2178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemplen, K.R.; De Sancho, D.; Clarke, J. The Response of Greek Key Proteins to Changes in Connectivity Depends on the Nature of Their Secondary Structure. Journal of Molecular Biology 2015, 427, 2159–2165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranaghan, M.J.; Li, J.J.; Laprise, D.M.; Garvie, C.W. Assessing Optimal: Inequalities in Codon Optimization Algorithms. BMC Biology 2021, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharp, P.M.; Li, W.-H. The Codon Adaptation Index-a Measure of Directional Synonymous Codon Usage Bias, and Its Potential Applications. Nucleic Acids Research 1987, 15, 1281–1295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, A.A.; Rubenstein, E. Proline: The Distribution, Frequency, Positioning, and Common Functional Roles of Proline and Polyproline Sequences in the Human Proteome. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e53785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, P.; Tropea, J.E.; Waugh, D.S. Enhancing the Solubility of Recombinant Proteins in Escherichia Coli by Using Hexahistidine-Tagged Maltose-Binding Protein as a Fusion Partner. In Heterologous Gene Expression in E.coli; Evans, T.C., Xu, M.-Q., Eds.; Methods in Molecular Biology; Humana Press: Totowa, NJ, 2011; Volume 705, pp. 259–274. ISBN 978-1-61737-966-6. [Google Scholar]

- Reuten, R.; Nikodemus, D.; Oliveira, M.B.; Patel, T.R.; Brachvogel, B.; Breloy, I.; Stetefeld, J.; Koch, M. Maltose-Binding Protein (MBP), a Secretion-Enhancing Tag for Mammalian Protein Expression Systems. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0152386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kellermann, O.; Szmelcman, S. Active Transport of Maltose in Escherichia Coli K12: Involvement of a “Periplasmic” Maltose Binding Protein. European Journal of Biochemistry 1974, 47, 139–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lénon, M.; Ke, N.; Ren, G.; Meuser, M.E.; Loll, P.J.; Riggs, P.; Berkmen, M. A Useful Epitope Tag Derived from Maltose Binding Protein. Protein Science 2021, 30, 1235–1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, S.; Almeida, A.; Castro, A.; Domingues, L. Fusion Tags for Protein Solubility, Purification and Immunogenicity in Escherichia Coli: The Novel Fh8 System. Front. Microbiol. 2014, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, K.; Rao, J.; Chen, B. Plant Protein Solubility: A Challenge or Insurmountable Obstacle. Advances in Colloid and Interface Science 2024, 324, 103074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhaskar, B.; Ramachandra, G.; Virupaksha, T.K. Alpha-Galactosidase of Germinating Seeds of Cassia Sericea Sw. J Food Biochemistry 1990, 14, 45–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Z.; Schaffer, A.A. A Novel Alkaline α-Galactosidase from Melon Fruit with a Substrate Preference for Raffinose. Plant Physiology 1999, 119, 979–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chien, S.-F.; Chen, S.-H.; Chien, M.-Y. Cloning, Expression, and Characterization of Rice α-Galactosidase. Plant Mol Biol Rep 2008, 26, 213–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, S.; Egert, A.; Stieger, B.; Keller, F. Functional Identification of Arabidopsis ATSIP2 (At3g57520) as an Alkaline -Galactosidase with a Substrate Specificity for Raffinose and an Apparent Sink-Specific Expression Pattern. Plant and Cell Physiology 2010, 51, 1815–1819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakharayapatna Ranganatha, K.; Venugopal, A.; Chinthapalli, D.K.; Subramanyam, R.; Nadimpalli, S.K. Purification, Biochemical and Biophysical Characterization of an Acidic α-Galactosidase from the Seeds of Annona Squamosa (Custard Apple). International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2021, 175, 558–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Liu, Y.; Dai, H.; Miao, M. Characteristics and Expression Patterns of Six α-Galactosidases in Cucumber (Cucumis Sativus L.). PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0244714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khrapunov, S.; Cheng, H.; Hegde, S.; Blanchard, J.; Brenowitz, M. Solution Structure and Refolding of the Mycobacterium Tuberculosis Pentapeptide Repeat Protein MfpA. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2008, 283, 36290–36299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michaux, C.; Pomroy, N.C.; Privé, G.G. Refolding SDS-Denatured Proteins by the Addition of Amphipathic Cosolvents. Journal of Molecular Biology 2008, 375, 1477–1488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dulermo, R.; Legras, J.-L.; Brunel, F.; Devillers, H.; Sarilar, V.; Neuvéglise, C.; Nguyen, H.-V. Truncation of Gal4p Explains the Inactivation of the GAL/MEL Regulon in Both Saccharomyces Bayanus and Some Saccharomyces Cerevisiae Wine Strains. FEMS Yeast Research 2016, 16, fow070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, H.; Wang, S.; Wang, J.; Song, M.; Xu, M.; Zhang, M.; Shen, Y.; Hou, J.; Bao, X. N-Hypermannose Glycosylation Disruption Enhances Recombinant Protein Production by Regulating Secretory Pathway and Cell Wall Integrity in Saccharomyces Cerevisiae. Sci Rep 2016, 6, 25654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, J.; Li, Q.; Tan, H.; Jiang, H.; Li, K.; Zhang, L.; Shi, Q.; Yin, H. Unique N-Glycosylation of a Recombinant Exo-Inulinase from Kluyveromyces Cicerisporus and Its Effect on Enzymatic Activity and Thermostability. J Biol Eng 2019, 13, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanurdzic, M.; Vaughn, M.W.; Jiang, H.; Lee, T.-J.; Slotkin, R.K.; Sosinski, B.; Thompson, W.F.; Doerge, R.W.; Martienssen, R.A. Epigenomic Consequences of Immortalized Plant Cell Suspension Culture. PLoS Biol 2008, 6, e302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tungekar, A.A.; Castillo-Corujo, A.; Ruddock, L.W. So You Want to Express Your Protein in Escherichia Coli ? Essays in Biochemistry 2021, 65, 247–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, S.; Agarwal, S.; Biancucci, M.; Satchell, K.J.F. Induced Autoprocessing of the Cytopathic Makes Caterpillars Floppy-like Effector Domain of the Vibrio Vulnificus MARTX Toxin: A Novel Cysteine Peptidase in Toxin Autoprocessing. Cellular Microbiology 2015, 17, 1494–1509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shindyalov, I.N.; Bourne, P.E. Protein Structure Alignment by Incremental Combinatorial Extension (CE) of the Optimal Path. Protein Engineering Design and Selection 1998, 11, 739–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kufareva, I.; Abagyan, R. Methods of Protein Structure Comparison. In Homology Modeling; Methods in Molecular Biology; Orry, A.J.W., Abagyan, R., Eds.; Humana Press: Totowa, NJ, 2011; Volume 857, pp. 231–257. ISBN 978-1-61779-587-9. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad, M.; Hirz, M.; Pichler, H.; Schwab, H. Protein Expression in Pichia Pastoris: Recent Achievements and Perspectives for Heterologous Protein Production. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 2014, 98, 5301–5317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosano, G.L.; Ceccarelli, E.A. Recombinant Protein Expression in Escherichia Coli: Advances and Challenges. Frontiers in Microbiology 2014, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karimi, M.; Inzé, D.; Depicker, A. GATEWAYTM Vectors for Agrobacterium-Mediated Plant Transformation. Trends in Plant Science 2002, 7, 193–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerasimova, S.V.; Smirnova, O.G.; Kochetov, A.V.; Shumnyi, V.K. Production of Recombinant Proteins in Plant Cells. Russ J Plant Physiol 2016, 63, 26–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lampropoulos, A.; Sutikovic, Z.; Wenzl, C.; Maegele, I.; Lohmann, J.U.; Forner, J. GreenGate - A Novel, Versatile, and Efficient Cloning System for Plant Transgenesis. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e83043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Vermeersch, M.; Van Leene, J.; De Jaeger, G.; Li, Y.; Vanhaeren, H. A Dynamic Ubiquitination Balance of Cell Proliferation and Endoreduplication Regulators Determines Plant Organ Size. Sci. Adv. 2024, 10, eadj2570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerstmans, H.; Grimon, D.; Gutiérrez, D.; Lood, C.; Rodríguez, A.; Van Noort, V.; Lammertyn, J.; Lavigne, R.; Briers, Y. A VersaTile-Driven Platform for Rapid Hit-to-Lead Development of Engineered Lysins. Sci. Adv. 2020, 6, eaaz1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartley, J.L. DNA Cloning Using In Vitro Site-Specific Recombination. Genome Research 2000, 10, 1788–1795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Zaeytijd, J.; Rougé, P.; Smagghe, G.; Van Damme, E.J.M. Structure and Activity of a Cytosolic Ribosome-Inactivating Protein from Rice. Toxins 2019, 11, 325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Atalah, B.; Fouquaert, E.; Vanderschaeghe, D.; Proost, P.; Balzarini, J.; Smith, D.F.; Rougé, P.; Lasanajak, Y.; Callewaert, N.; Van Damme, E.J.M. Expression Analysis of the Nucleocytoplasmic Lectin ‘Orysata’ from Rice in Pichia Pastoris. The FEBS Journal 2011, 278, 2064–2079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Leene, J.; Eeckhout, D.; Persiau, G.; Van De Slijke, E.; Geerinck, J.; Van Isterdael, G.; Witters, E.; De Jaeger, G. Isolation of Transcription Factor Complexes from Arabidopsis Cell Suspension Cultures by Tandem Affinity Purification. In Plant Transcription Factors; Yuan, L., Perry, S.E., Eds.; Methods in Molecular Biology; Humana Press: Totowa, NJ, 2011; Volume 754, pp. 195–218. ISBN 978-1-61779-153-6. [Google Scholar]

- Dubiel, M.; De Coninck, T.; Osterne, V.J.S.; Verbeke, I.; Van Damme, D.; Smagghe, G.; Van Damme, E.J.M. The ArathEULS3 Lectin Ends up in Stress Granules and Can Follow an Unconventional Route for Secretion. IJMS 2020, 21, 1659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schindelin, J.; Arganda-Carreras, I.; Frise, E.; Kaynig, V.; Longair, M.; Pietzsch, T.; Preibisch, S.; Rueden, C.; Saalfeld, S.; Schmid, B.; et al. Fiji: An Open-Source Platform for Biological-Image Analysis. Nat Methods 2012, 9, 676–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradford, M.M. A Rapid and Sensitive Method for the Quantitation of Microgram Quantities of Protein Utilizing the Principle of Protein-Dye Binding. Analytical Biochemistry 1976, 72, 248–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beygmoradi, A.; Homaei, A.; Hemmati, R.; Fernandes, P. Recombinant Protein Expression: Challenges in Production and Folding Related Matters. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2023, 233, 123407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dechavanne, V.; Barrillat, N.; Borlat, F.; Hermant, A.; Magnenat, L.; Paquet, M.; Antonsson, B.; Chevalet, L. A High-Throughput Protein Refolding Screen in 96-Well Format Combined with Design of Experiments to Optimize the Refolding Conditions. Protein Expression and Purification 2011, 75, 192–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Illergård, K.; Ardell, D.H.; Elofsson, A. Structure Is Three to Ten Times More Conserved than Sequence—A Study of Structural Response in Protein Cores. Proteins 2009, 77, 499–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofstee, B.H.J. Non-Inverted versus Inverted Plots in Enzyme Kinetics. Nature 1959, 184, 1296–1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanes, C.S. Studies on Plant Amylases: The Effect of Starch Concentration upon the Velocity of Hydrolysis by the Amylase of Germinated Barley. Biochemical Journal 1932, 26, 1406–1421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Criterion | Bacterial cells | Yeast/fungal cells | Plant cells | Insect cells | Mammalian cells |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Common example | Escherichia coli | Pichia pastoris | Arabidopsis PSB-D | Spodoptera frugiperda | Chinese Hamster Ovaries |

| Ease of genetic manipulation | Easy | Moderate | Difficult | Moderate | Difficult |

| Time for protein production | 1-2 days | 3-5 days | weeks | 7-10 days | Weeks to months |

| Cell doubling time | Very fast (20 minutes) |

Moderate (1-2 hours) |

Slow (20-48 hours) |

Slow (18-24 hours) |

Slow (16-24 hours) |

| Cultivation costs | Very low | Low to moderate | Moderate to high | High | Very high |

| Complexity of growth media | Simple | Moderate | Complex | Very complex | Very complex |

| Expression (mg protein per L of medium) | 100-5000 | 100-5000 | 10-100 | 10-1000 | 10-1000 |

| Scalability | High | High | Moderate | Moderate | High |

| Disulfide bridges | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Glycosylation type | None | High-mannose N-glycans | Complex (plant-specific) N-glycans | Partial (insect-specific) N-glycans | Fully human-like N-glycans |

| Protein secretion | Periplasmic is possible but requires secretion signals | Possible | Possible | Possible | Possible |

| Protein stability and degradation risk | High – risk of inclusion bodies | Moderate – secreted proteins are more stable | Risk of proteolysis | Moderate | High – minimal proteolysis |

| Suitability for complex eukaryotic proteins | Usually not | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Regulatory approval and industrial use | Widely used for research, not for therapeutics | Approved for some enzymes and vaccines | Limited biopharma use | Used in some vaccines | Industry standards, FDA/EMA approved |

| EXP | Host organism |

Strain or type | Expression plasmid | CDS a | CDS adjustments |

Tags | Cloning method | Lysis method | Result | Refolding |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | E. coli | BL21 | pET-22b(+) | OsAPSE | Codon Opt. | N-pelB+C-His6 | Res. & Lig | LyB | Ins. | Yes |

| 2 | BL21-AI | Ins. | No | |||||||

| 3 | pLysS | Ins. | No | |||||||

| 4 | Rosetta | Ins. | No | |||||||

| 5 | ArcticExpress | Ins. | No | |||||||

| 6 | Shuffle | N.P. | No | |||||||

| 7 | GH27 | Ins. | No | |||||||

| 8 | E. coli | BL21 | pET-28a(+) | OsAPSE | Codon Opt. | C-His6 | Res. & Lig | LyB | Ins. | No |

| 9 | ArcticExpress | Ins. | No | |||||||

| 10 | E. coli | BL21 | pVTD13 | OsAPSE | Codon Opt. | N-GST+C-His6 | VersaTile cloning | LyB | N.P. | No |

| 11 | GH27 | N.P. | No | |||||||

| 12 | ricin-B | Ins. | No | |||||||

| 13 | GH-all-beta | Ins. | No | |||||||

| 14 | E. coli | BL21 Star | pET-32a(+) b | OsAPSE | Codon Opt. | N-TRX+C-His6 | Res. & Lig | Son. | Ins. | Yes |

| 15 | ArcticExpress | Ins. | No | |||||||

| 16 | Rosetta | Ins. | No | |||||||

| 17 | E. coli | BL21 | pET-21a(+) | OsAPSE | Harm. c | C-His6 | Res. & Lig | LyB | Ins. | No |

| 18 | Rosetta | N.P. | No | |||||||

| 19 | BL21 | Codon Opt. d | Ins. | No | ||||||

| 20 | Shuffle | N.P. | No | |||||||

| 21 | BL21 | PROSS e | Ins. | No | ||||||

| 22 | Shuffle | N.P. | No | |||||||

| 23 | E. coli | BL21 | pDEST | OsAPSE | Codon Opt. | N-MBP+TEV site+C-FLAG3 or C-HA3 or C-His6 | GG cloning |

LyB | Ins. | No |

| 24 | ricin-B | Ins. | No | |||||||

| 25 | GH-β | Ins. | No | |||||||

| 26 | GH27 | LyB + Son. | Soluble | No | ||||||

| 27 | N/C-MBP2+C-His6 | LyB | Ins. | No | ||||||

| 28 | N-GST+C-His6 | Ins. | No | |||||||

| 29 | P. pastoris | X-33 | pPICZαA | OsAPSE | Codon Opt. | N-α-factor+C-His6 | Res. & Lig | Beads + LyB | N.P. | No |

| 30 | GlycoDelete | N.P. | No | |||||||

| 31 | KM71H | N.P. | No | |||||||

| 32 | P. pastoris | X-33 | Modified pPICZαA | GH27 | Codon Opt. | N-MBP+C-RFP | GG cloning |

Beads + LyB | Soluble | No |

| 33 | N/C-MBP2+C-His6 | N.P. | No | |||||||

| 34 | A. thaliana | PSB-D cell culture | pK7WG2D | OsAPSE | Codon Opt. | Reporter EGFP+C-His6 | GW cloning |

Cryo + LyB | Soluble | No |

| 35 | GH27 | N.P. | No | |||||||

| 36 | ricin-B | N.P. | No | |||||||

| 37 | GH-β | N.P. | No | |||||||

| 38 | BY-2 CFPS | ALiCE | pALiCE02 | GH27 | Codon Opt. | C-His6 | Res. & Lig | None | Soluble f | No |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).