Submitted:

23 May 2024

Posted:

24 May 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. The Current Study

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Data Sources and Study Design

3.2. Measures

3.2.1. Dependent Variables

3.2.2. Individual-Level Independent Variable(s)

3.2.3. Perceived Social Support

3.2.4. Individual-Level Control Variables

3.2.5. Country-Level Social Support

3.2.6. Country-Level Control Variable(s)

3.3. Statistical Analyses

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Analyses of Sample Characteristics

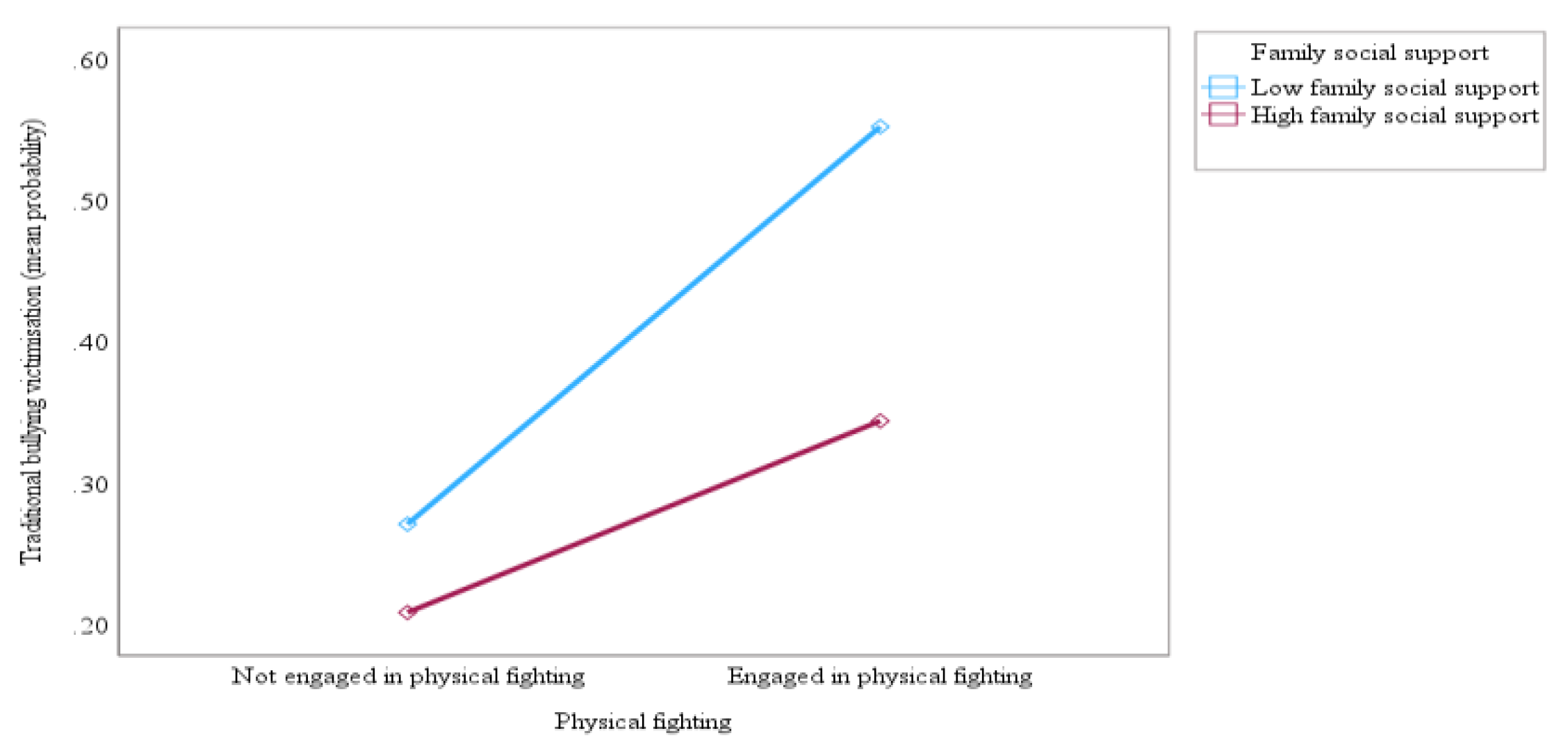

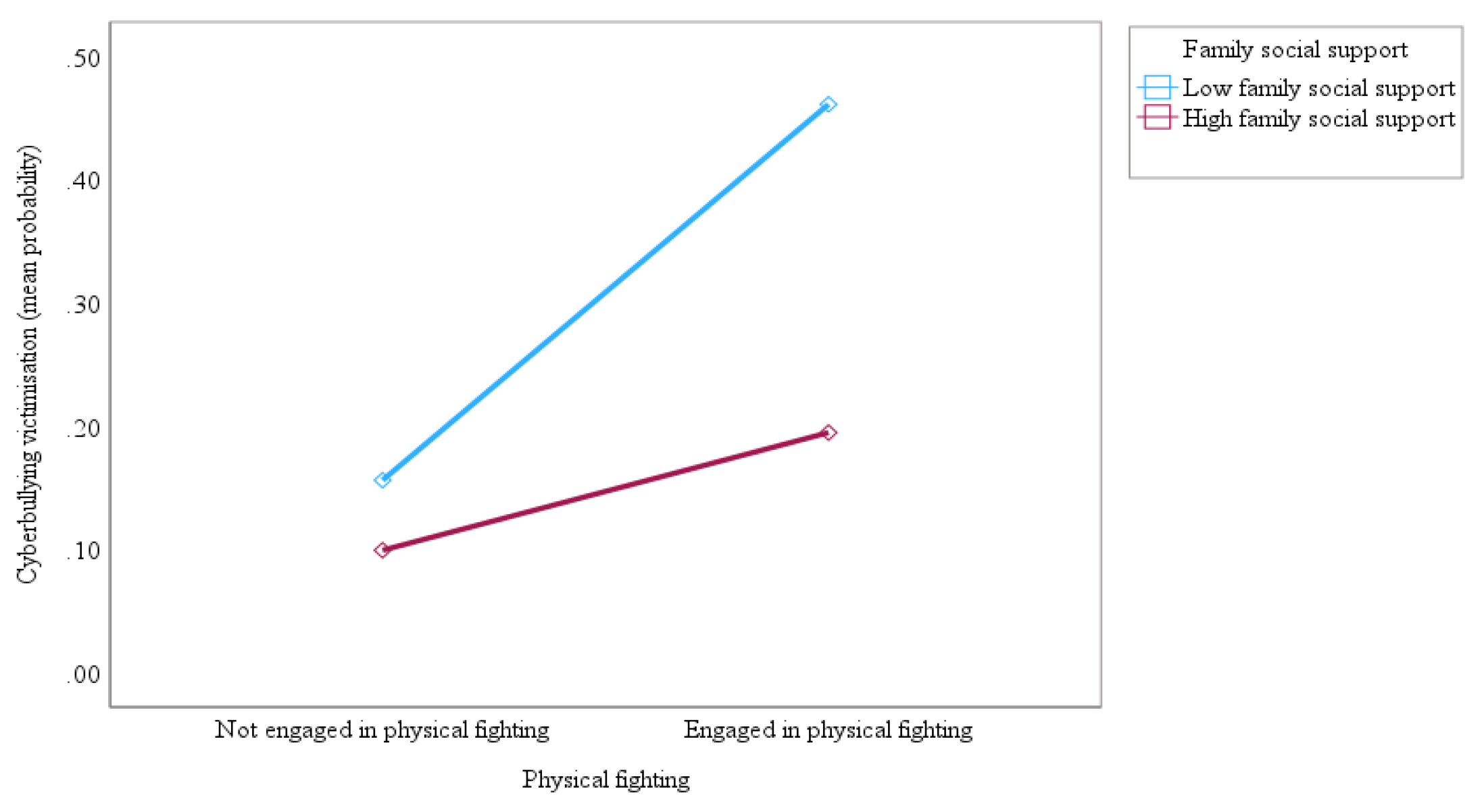

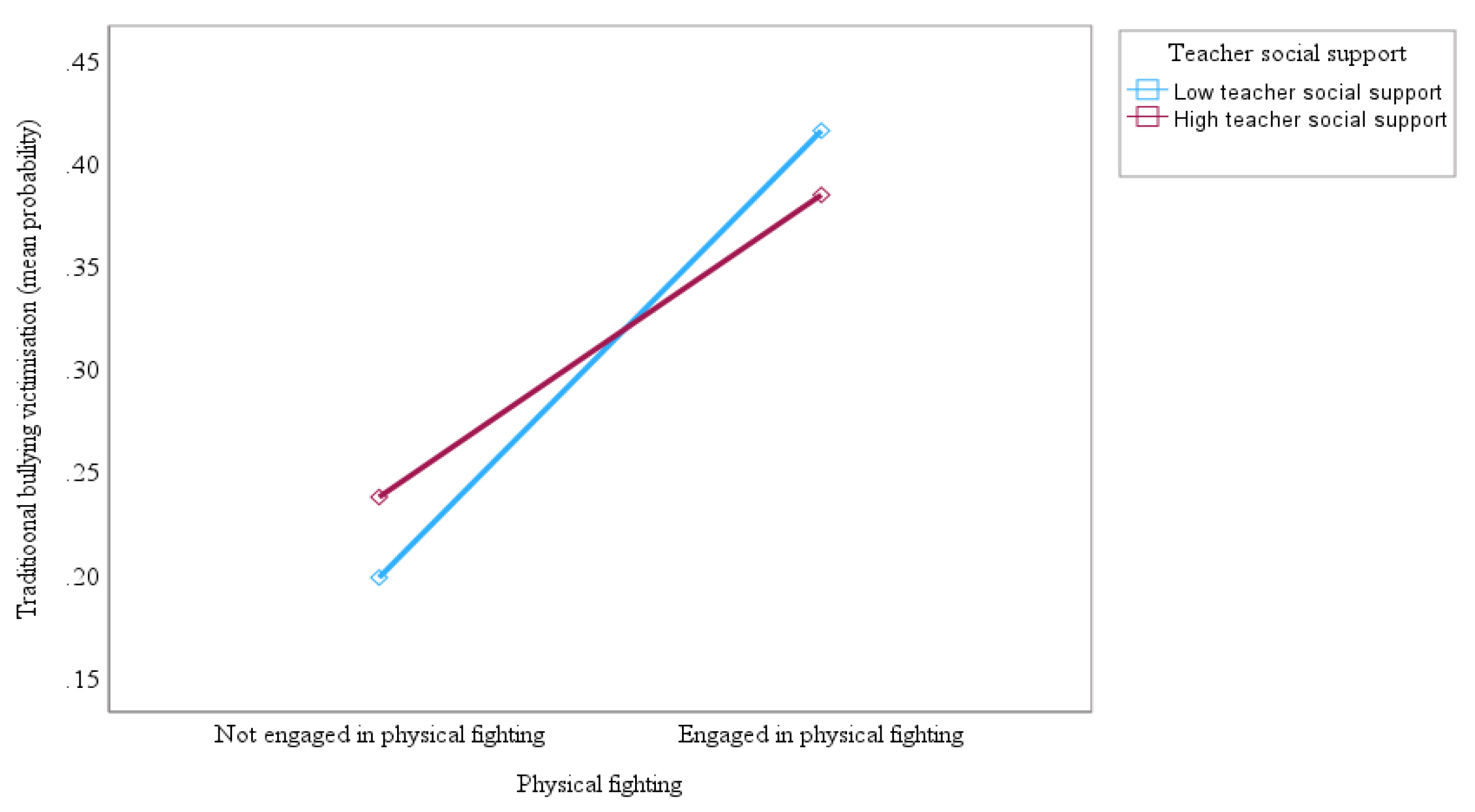

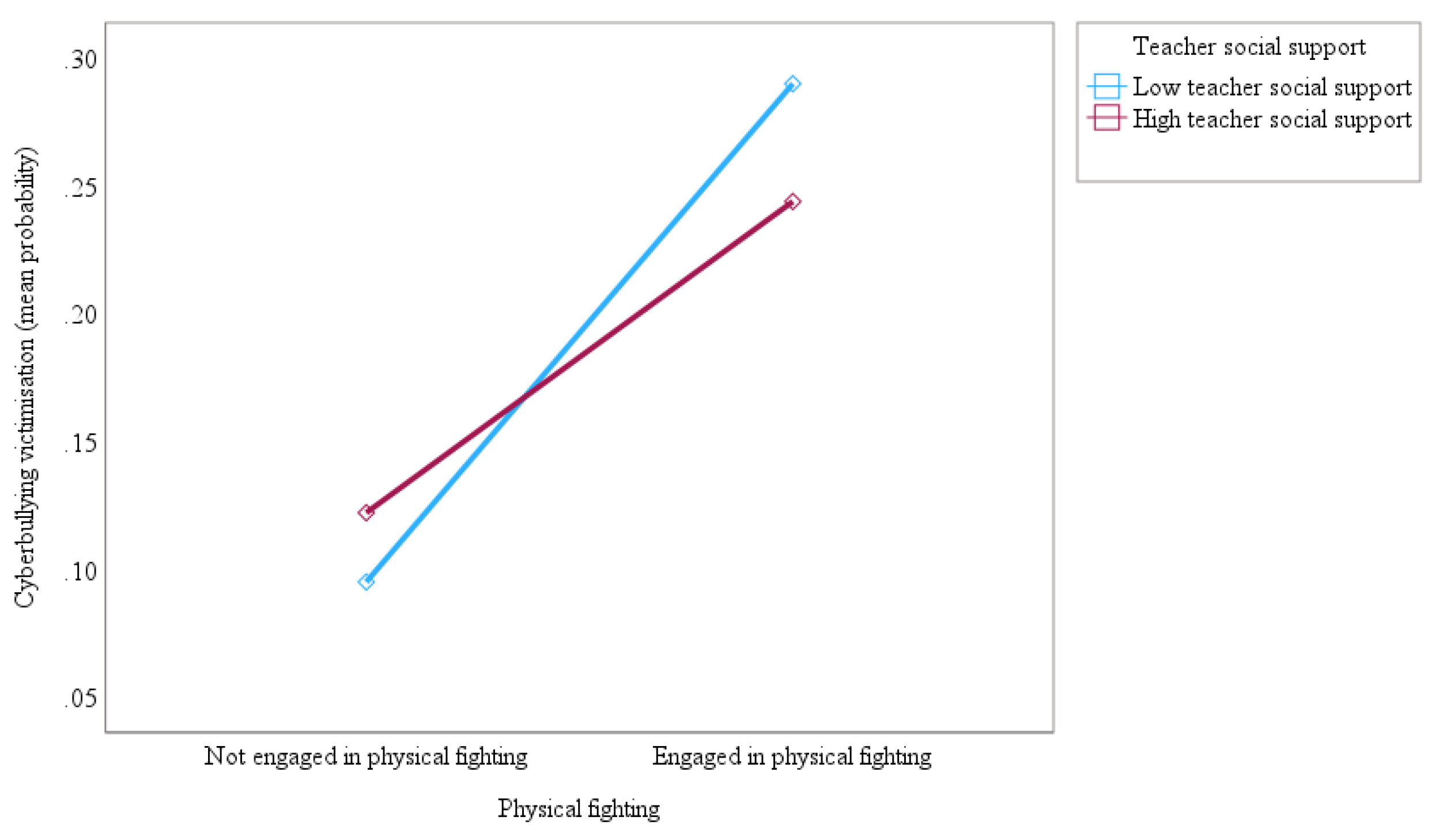

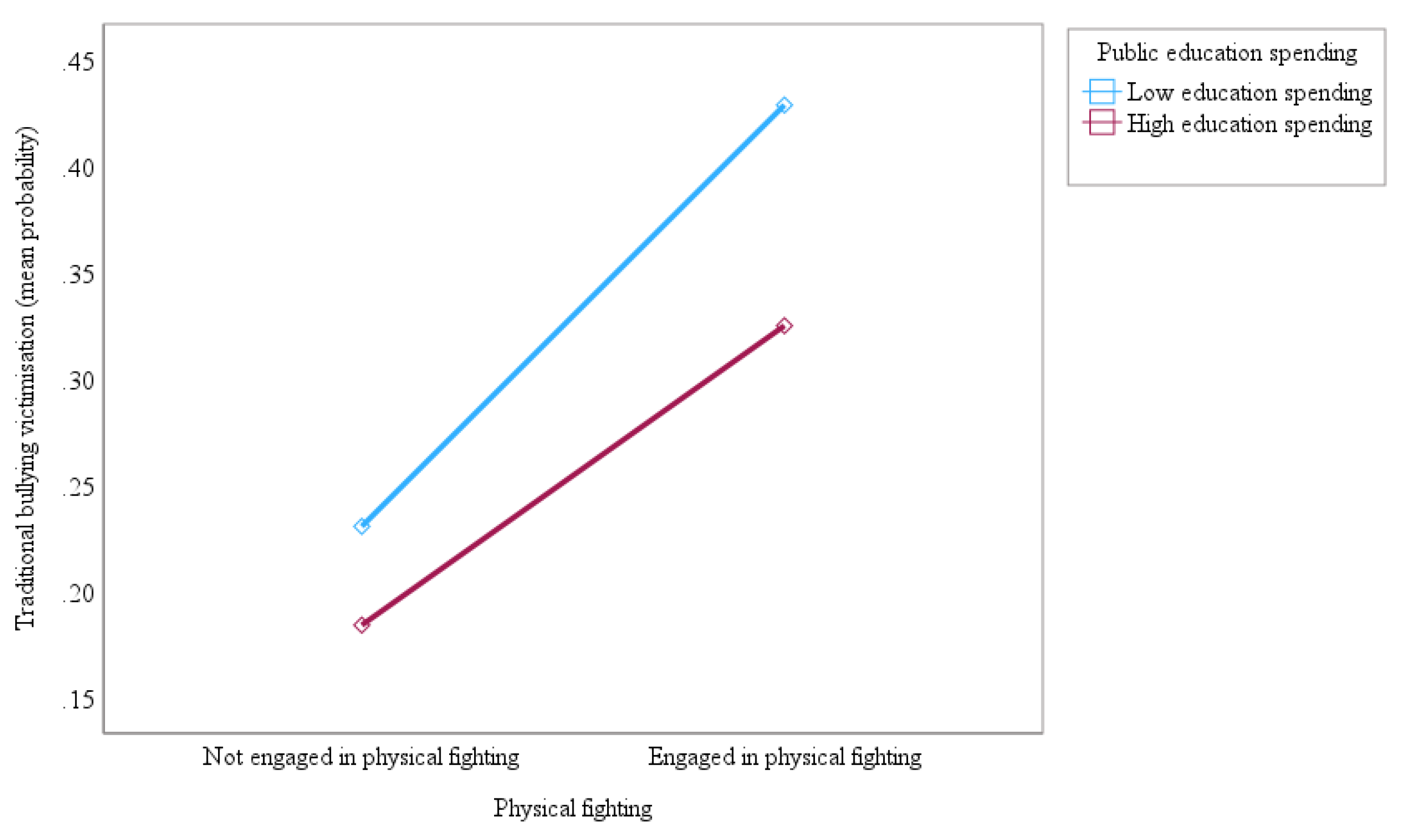

4.2. Relationship between Physical Fighting and Victimisation by Traditional Bullying and Cyberbullying, and the Moderating Role of Perceived Social Support and public education spending in these Relationships

5. Discussion

5.1. Strengths and Limitations of the Study

6. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgements

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Stassen Berger, K. Update on Bullying at School: Science Forgotten? Dev. Rev. 2007, 27, 90–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolke, D.; Lereya, S.T. Long-Term Effects of Bullying. Arch. Dis. Child. 2015, 100, 879–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gladden, R.M.; Vivolo-Kantor, A.M.; Hamburger, M.E.; Lumpkin, C.D. Bullying Surveillance among Youths : Uniform Definitions for Public Health and Recommended Data Elements, Version 1.0. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the United States Department of Education: Atlanta, GA, 2014. https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/21596.

- Olweus, D. The Olweus Bully/Victim Questionnaire. Br. J. Educ. Psychol. J. Educ. Heal. 1993, No. January 1996, 0–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olweus, D. The Revised Olweus Bully/Victim Questionnaire. University of Bergen: Bergen, 1996. [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Abell, N.; Holmes, J.L. Validation of Measures of Cyberbullying Perpetration and Victimization in Emerging Adulthood. Res. Soc. Work Pract. 2017, 27, 456–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Roh, B.R.; Yang, K.E. Exploring the Association between Social Support and Patterns of Bullying Victimization among School-Aged Adolescents. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2022, 136, 106418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menesini, E.; Spiel, C. Introduction: Cyberbullying: Development, Consequences, Risk and Protective Factors. European Journal of Developmental Psychology. Taylor & Francis: Menesini, Ersilia: Department of Psychology, University of Florence, Via S. Salvi 12, Firenze, Italy, 50135, ersilia.menesini@unifi.it 2012, pp 163–167. [CrossRef]

- Hong, J.S.; Lee, J.; Espelage, D.L.; Hunter, S.C.; Patton, D.U.; Rivers, T. Understanding the Correlates of Face-to-Face and Cyberbullying Victimization among u.s. Adolescents: A Social-Ecological Analysis. Violence Vict. 2016, 31, 638–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sampasa-Kanyinga, H.; Lalande, K.; Colman, I. Cyberbullying Victimisation and Internalising and Externalising Problems among Adolescents: The Moderating Role of Parent-Child Relationship and Child’s Sex. Epidemiol. Psychiatr. Sci. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schoeler, T.; Duncan, L.; Cecil, C.M.; Ploubidis, G.B. Supplemental Material for Quasi-Experimental Evidence on Short- and Long-Term Consequences of Bullying Victimization: A Meta-Analysis. Psychol. Bull. 2018, 144, 1229–1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skilbred-Fjeld, S.; Reme, S.E.; Mossige, S. Cyberbullying Involvement and Mental Health Problems among Late Adolescents. Cyberpsychology 2020, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keith, S. How Do Traditional Bullying and Cyberbullying Victimization Affect Fear and Coping among Students? An Application of General Strain Theory. Am. J. Crim. Justice 2018, 43, 67–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putra, G.N.E.; Dendup, T. Health and Behavioural Outcomes of Bullying Victimisation among Indonesian Adolescent Students: Findings from the 2015 Global School-Based Student Health Survey. Psychol. Heal. Med. 2020, 27, 513–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seo, Hye-Jin, Young-eun Jung, Moon-Doo Kim, W. -M. B. Factors Associated with Sexually Transmitted Infections among Korean Adolescents. J. Korean Acad. Community Heal. Nurs. 2017, 28, 431–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, L.A.; Ganapathy, S.S.; Sooryanarayana, R.; Hasim, M.H.; Saminathan, T.A.; Mohamad Anuar, M.F.; Ahmad, F.H.; Abd Razak, M.A.; Rosman, A. Bullying Victimization Among School-Going Adolescents in Malaysia: Prevalence and Associated Factors. Asia-Pacific J. Public Heal. 2019, 31 (8_suppl), 18S–29S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hosozawa, M.; Bann, D.; Fink, E.; Elsden, E.; Baba, S.; Iso, H.; Patalay, P. Bullying Victimisation in Adolescence: Prevalence and Inequalities by Gender, Socioeconomic Status and Academic Performance across 71 Countries. eClinicalMedicine 2021, 41, 101142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho, S.; Lee, H.; Peguero, A.A.; Park, S. Social-Ecological Correlates of Cyberbullying Victimization and Perpetration among African American Youth: Negative Binomial and Zero-Inflated Negative Binomial Analyses. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2019, 101, 50–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodkin, P.C.; Espelage, D.L.; Hanish, L.D. A Relational Framework for Understanding Bullying: Developmental Antecedents and Outcomes. Am. Psychol. 2015, 70, 311–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronfenbrenner, U. The Ecology of Human Development. Harvard University Press: Cambridge, Massachusetts, 1979.

- Hong, J.S.; Davis, J.P.; Sterzing, P.R.; Yoon, J.; Choi, S.; Smith, D.C. A Conceptual Framework for Understanding the Association between School Bullying Victimization and Substance Misuse. Am. J. Orthopsychiatry 2014, 84, 696–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- da Silva, R.A.; de Azevedo Cardoso, T.; Jansen, K.; de Mattos Souza, L.D.; Vanila Godoy, R.; Sica Cruzeiro, A.L.; Lessa Horta, B.; Pinheiro, R.T. Bullying and Associated Factors in Adolescents Aged 11 to 15 Years. Trends Psychiatry Psychother. 2012, 34, 19–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mazaba-Liwewe, M.; Rudatskira, E.; Babaniyi, O.; Siziya, S.; Mulenga, D.; Muula, A. Correlates of Bullying Victimization among School-Going Adolescents in Algeria: Results from the 2011 Global School-Based Health Survey. Int. J. Med. Public Heal. 2014, 4, 407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pengpid, S.; Peltzer, K. Bullying and Its Associated Factors among School-Aged Adolescents in Thailand. Sci. World J. 2013, 2013, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabramani, V.; Idris, I.B.; Ismail, H.; Nadarajaw, T.; Zakaria, E.; Kamaluddin, M.R. Bullying and Its Associated Individual, Peer, Family and School Factors: Evidence from Malaysian National Secondary School Students. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deryol, R.; Wilcox, P.; Stone, S. Individual Risk, Country-Level Social Support, and Bullying and Cyberbullying Victimization Among Youths: A Cross-National Study. J. Interpers. Violence 2021, 37, (17–18). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolke, D.; Samara, M.M. Bullied by Siblings: Association with Peer Victimisation and Behaviour Problems in Israeli Lower Secondary School Children. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry Allied Discip. 2004, 45, 1015–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swearer, S.M.; Espelage, D.L.; Vaillancourt, T.; Hymel, S. What Can Be Done About School Bullying?: Linking Research to Educational Practice. Educ. Res. 2010, 39, 38–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gage, J.C.; Overpeck, M.D.; Nansel, T.R.; Kogan, M.D. Peer Activity in the Evenings and Participation in Aggressive and Problem Behaviors. J. Adolesc. Heal. 2005, 37, 517.e7–517e14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saarento, S.; Garandeau, C.F.; Salmivalli, C. Classroom- and School-Level Contributions to Bullying and Victimization : A Review. 2014, No. July. [CrossRef]

- Smokowski, P.R.; Evans, C.B.R. Bullying and Victimization Across the Lifespan: Playground Politics and Power. 2019. https://www.proquest.com/docview/2251239281?accountid=15870.

- Burton, K.A.; Florell, D.; Wygant, D.B. The Role of Peer Attachment and Normative Beliefs about Aggression on Traditional Bullying and Cyberbullying. Psychol. Sch. 2013, 50, 103–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, S.H.; Ang, R.P. Relationship between Boys’ Normative Beliefs about Aggression and Their Physical, Verbal, and Indirect Aggressive Behaviors. Adolescence 2009, 44, 635–650. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Cho, S.; Wooldredge, J. Lifestyles, Informal Controls, and Youth Victimization Risk in South Korea and the United States. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2018, 27, 1358–1371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Luo, Y.; Hao, Z.; Smith, B.; Guo, Y.; Tyrone, C. Risk Factors of Cyberbullying Perpetration Among School-Aged Children Across 41 Countries: A Perspective of Routine Activity Theory. Int. J. Bullying Prev. 2021, 3, 168–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noret, N.; Hunter, S.C.; Rasmussen, S. The Role of Perceived Social Support in the Relationship Between Being Bullied and Mental Health Difficulties in Adolescents. School Ment. Health 2020, 12, 156–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vannucci, A.; Fagle, T.R.; Simpson, E.G.; Ohannessian, C.M.C. Perceived Family and Friend Support Moderate Pathways From Peer Victimization to Substance Use in Early-Adolescent Girls and Boys: A Moderated-Mediation Analysis. J. Early Adolesc. 2021, 41, 128–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espelage, D.L.; De La Rue, L. School Bullying: Its Nature and Ecology. Int. J. Adolesc. Med. Health 2012, 24, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Espelage, D.L.; Swearer, S.M. Expanding the Social-Ecological Framework of Bullying among Youth: Lessons Learned from the Past and Directions for the Future. In Bullying in North American Schools, Second Edition (Pp. 24-31). Taylor and Francis. Https://Doi.Org/10.4324/9780203842898. 2011. [CrossRef]

- Cohen, S.; Wills, T.A. Stress, Social Support, and the Buffering Hypothesis. Psychol. Bull. 1985, 98, 310–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, N. “Conceptualizing Social Support.” In N. Lin, A. Dean, and W. Edsel (Eds.), Social Support, Life Events, and Depression, Pp. 17-30. Orlando: Aca- Demic Press. In Social Support, Life Events, and Depression; 1986; pp 17–30. [CrossRef]

- Cullen, F.T. Social, Support as an Organizing Concept for Criminology: Presidential, Address to the Academy of Criminal, Justice Sciences. Justice Q. 1994, 11, 527–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šmigelskas, K.; Vaičiūnas, T.; Lukoševičiūtė, J.; Malinowska-Cieślik, M.; Melkumova, M.; Movsesyan, E.; Zaborskis, A. Sufficient Social Support as a Possible Preventive Factor against Fighting and Bullying in School Children. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taliaferro, L.A.; Doty, J.L.; Gower, A.L.; Querna, K.; Rovito, M.J. Profiles of Risk and Protection for Violence and Bullying Perpetration Among Adolescent Boys. J. Sch. Health 2020, 90, 212–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Espelage, D.L.; Low, S.; Rao, M.A.; Hong, J.S.; Little, T.D. Family Violence, Bullying, Fighting, and Substance Use among Adolescents: A Longitudinal Mediational Model. J. Res. Adolesc. 2014, 24, 337–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowes, L.; Maughan, B.; Caspi, A.; Moffitt, T.E.; Arseneault, L. Families Promote Emotional and Behavioural Resilience to Bullying: Evidence of an Environmental Effect. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry Allied Discip. 2010, 51, 809–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rothon, C.; Head, J.; Klineberg, E.; Stansfeld, S. Can Social Support Protect Bullied Adolescents from Adverse Outcomes? A Prospective Study on the Effects of Bullying on the Educational Achievement and Mental Health of Adolescents at Secondary Schools in East London. J. Adolesc. 2011, 34, 579–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, J.S.; Garbarino, J. Risk and Protective Factors for Homophobic Bullying in Schools: An Application of the Social-Ecological Framework. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 2012, 24, 271–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shetgiri, R.; Lin, H.; Flores, G. Trends in Risk and Protective Factors for Child Bullying Perpetration in the United States. Child Psychiatry Hum. Dev. 2013, 44, 89–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Iannotti, R.J.; Nansel, T.R. School Bullying Among Adolescents in the United States: Physical, Verbal, Relational, and Cyber. J. Adolesc. Heal. 2009, 45, 368–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reyes Rodríguez, A.C.; Vera Noriega, J.A.; Valdés Cuervo, A.A. Teaching Practices, School Support and Bullying. World J. Educ. 2017, 7, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stankovic, S.; Santric-milicevic, M.; Nikolic, D.; Bjelica, N.; Babic, U. The Association between Participation in Fights and Bullying and the Perception of School, Teachers, and Peers among School-Age Children in Serbia. Children 2022, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, L.H.; Hao, Y.; Hong, J.C.; Ye, J.N. The Relationship between Teacher Support and Bullying in Schools: The Mediating Role of Emotional Self-Efficacy. Curr. Psychol. 2022, 42, 31853–31862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Begotti, T.; Tirassa, M.; Maran, D.A. Pre-Service Teachers’ Intervention in School Bullying Episodes with Special Education Needs Students: A Research in Italian and Greek Samples. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frisén, A.; Hasselblad, T.; Holmqvist, K. What Actually Makes Bullying Stop? Reports from Former Victims. J. Adolesc. 2012, 35, 981–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williford, A.; Depaolis, K.J. Predictors of Cyberbullying Intervention among Elementary School Staff: The Moderating Effect of Staff Status. Psychol. Sch. 2016, 53, 1032–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, J.; Bauman, S. Teachers: A Critical But Overlooked Component of Bullying Prevention and Intervention. Theory Pract. 2014, 53, 308–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burger, C.; Strohmeier, D.; Spröber, N.; Bauman, S.; Rigby, K. How Teachers Respond to School Bullying: An Examination of Self-Reported Intervention Strategy Use, Moderator Effects, and Concurrent Use of Multiple Strategies. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2015, 51, 191–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rigby, K. How Teachers Address Cases of Bullying in Schools: A Comparison of Five Reactive Approaches. Educ. Psychol. Pract. 2014, 30, 409–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veenstra, R.; Lindenberg, S.; Huitsing, G.; Sainio, M.; Salmivalli, C. The Role of Teachers in Bullying: The Relation between Antibullying Attitudes, Efficacy, and Efforts to Reduce Bullying. J. Educ. Psychol. 2014, 106, 1135–1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Stasio, M.R.; Savage, R.; Burgos, G. Social Comparison, Competition and Teacher–Student Relationships in Junior High School Classrooms Predicts Bullying and Victimization. J. Adolesc. 2016, 53, 207–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flaspohler, P.D.; Elfstrom, J.L.; Vanderzee, K.L.; Sink, H.E.; Birchmeier, Z. Stand by Me: The Effects of Peer and Teacher Support in Mitigating the Impact of Bullying on Quality of Life. Psychol. Sch. 2009, 46, 636–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eşkisu, M. The Relationship between Bullying, Family Functions, Perceived Social Support among High School Students. Procedia - Soc. Behav. Sci. 2014, 159, 492–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espelage, D.L.; Hong, J.S.; Rao, M.A.; Thornberg, R. Understanding Ecological Factors Associated with Bullying across the Elementary to Middle School Transition in the United States. Violence Vict. 2015, 30, 470–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, J.S.; Espelage, D.L. A Review of Research on Bullying and Peer Victimization in School: An Ecological System Analysis. Aggress. Violent Behav. 2012, 17, 311–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chamlin, M.B. , Cochran, J.K. Social Altruism and Crime. Criminology 1997, 35, 203–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chouhy, C. Social Support and Crime. In Krohn M., Hendrix N., Penly Hall G., Lizotte A., Eds.; Handbook on Crime and Deviance: Handbooks of Sociology and Social Research; Marvin D. Krohn Nicole Hendrix Gina Penly Hall Alan J. Lizotte Editors, Ed.; Springer Nature Switzerland AG: Cham, 2019; pp 213–241. [CrossRef]

- Chamlin, M.B.; Cochran, J.K. Social Altruism and Crime. Criminology 1997, 35, 203–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loeber, R.; Stouthamer-Loeber, M. Family Factors as Correlates and Predictors of Juvenile Conduct Problems and Delinquency; 1986; Vol. 7. [CrossRef]

- Wright, J.P.; Cullen, F.T.; Miller, J.T. Family Social Capital and Delinquent Involvement. J. Crim. Justice 2001, 29, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Currie, E. Crime and Punishment in America. New York: Owl Books.; Owl books; Picador, 1998.

- Yoshikawa, H. Prevention as Cumulative Protection: Effects of Early Family Support and Education on Chronic Delinquency and Its Risks. Psychol. Bull. 1994, 115, 28–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cullen, F.T.; Wright, J.P.; Chamlin, M.B. Social Support and Social Reform: A Progressive Crime Control Agenda. Crime Delinq. 1999, 45, 188–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podaná, Z. Violent Victimization of Youth from a Cross-National Perspective: An Analysis Inspired by Routine Activity Theory. Int. Rev. Vict. 2017, 23, 325–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azimi, A.M.; Daigle, L.E. Violent Victimization: The Role of Social Support and Risky Lifestyle. Violence Vict. 2020, 35, 20–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biswas, T.; Scott, J.G.; Munir, K.; Thomas, H.J.; Huda, M.M.; Hasan, M.M.; David de Vries, T.; Baxter, J.; Mamun, A.A. Global Variation in the Prevalence of Bullying Victimisation amongst Adolescents: Role of Peer and Parental Supports. EClinicalMedicine 2020, 20, 100276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brezina, T.; Azimi, A.M. Social Support, Loyalty to Delinquent Peers, and Offending: An Elaboration and Test of the Differential Social Support Hypothesis. Deviant Behav. 2018, 39, 648–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altheimer, I. Social Support, Ethnic Heterogeneity, and Homicide: A Cross-National Approach. J. Crim. Justice 2008, 36, 103–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inchley, J.; Currie, D.; Cosma, A.; Samdal, O. Health Behaviour in School-Aged Children (HBSC) Study Protocol: Background, Methodology and Mandatory Items for the 2017/18 Survey; Child and Adolescent Health Research Unit, University of St Andrews: St Andrews, 2018.

- Heck, R.H.; Thomas, S.L. An Introduction to Multilevel Modeling Techniques: MLM and SEM Approaches; Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group: New York, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vazsonyi, A.T.; Javakhishvili, M.; Ksinan, A.J. Routine Activities and Adolescent Deviance across 28 Cultures. J. Crim. Justice 2018, 57, 56–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Due, P.; Merlo, J.; Harel-Fisch, Y.; Damsgaard, M.T.; Holstein, B.E.; Hetland, J.; Currie, C.; Gabhainn, S.N.; De Matos, M.G.; Lynch, J. Socioeconomic Inequality in Exposure to Bullying during Adolescence: A Comparative, Cross-Sectional, Multilevel Study in 35 Countries. Am. J. Public Health 2009, 99, 907–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solberg, M.E.; Olweus, D. Prevalence Estimation of School Bullying with the Olweus Bully/Victim Questionnaire. Aggress. Behav. 2003, 29, 239–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craig, W.; Harel-Fisch, Y.; Fogel-Grinvald, H.; Dostaler, S.; Hetland, J.; Simons-Morton, B.; Molcho, M.; de Matos, M.G.; Overpeck, M.; Due, P.; Pickett, W.; Mazur, J.; Favresse, D.; Leveque, A.; Pickett, W.; Aasvee, K.; Varnai, D.; Harel, Y.; Korn, L.; Villerusa, A.; Ramos Valverde, P.; Scheidt, P.; Boyce, W.; Holstein, B.; Vollebergh, W.; Samdal, O.; van der Sluijs, W.; Katreniakova, Z.; Nansel, T. A Cross-National Profile of Bullying and Victimization among Adolescents in 40 Countries. Int. J. Public Health 2009, 54 (Suppl. 2), 216–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hellfeldt, K.; Laura, L. Cyberbullying and Psychological Well-Being in Young Adolescence- The Potential Protective Mediation Effects of Social Support. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 17, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, S. Cyberbullying and Delinquency in Adolescence: The Potential Mediating Effects of Social Attachment and Delinquent Peer Association. J. Interpers. Violence 2021, 37, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Currie, C.; Inchley, J.; Molcho, M.; Lenzi, M.; Veselska, Z.; Wild, F. Health Behaviour in School-Aged Children (HBSC) Study Protocol: Background, Methodology and Mandatory Items for the 2013/14 Survey. Child and Adolescent Health Research Unit, University of St Andrews: St Andrews, 2014. http://www.hbsc.

- Cosma, A.; Bjereld, Y.; Elgar, F.J.; Richardson, C.; Bilz, L.; Craig, W.; Augustine, L.; Molcho, M.; Malinowska-cie, M.; Walsh, S.D. Gender Differences in Bullying Reflect Societal Gender Inequality : A Multilevel Study With Adolescents in 46 Countries. J. Adolesc. Heal. 2022, 71, 601–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucas-Molina, B.; Perez-albeniz, A.; Solbes-Canales, IreneBullying, C. and M. H. T. R. of S. C. as a S. P. F.; Ortuño Sierra, J.; Fonseca-Pedrero, E. Bullying, Cyberbullying and Mental Health: The Role of Student Connectedness as a School Protective Factor. Psychosoc. Interv. 2021, 31, 33–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stevens, G.W.J.M.; Boer, M.; Titzmann, P.F.; Cosma, A.; Walsh, S.D. Immigration Status and Bullying Victimization: Associations across National and School Contexts. J. Appl. Dev. Psychol. 2020, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adema, W.; Ladaique, M. How Expensive Is the Welfare State? Gross and Net Indicators in the OECD Social Expenditure Database (SOCX): OECD Social, Employment and Migration Working Papers. OECD Social, Employment and Migration …. Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD): Paris, 2009, pp 1–97.

- Pratt, T.C.; Godsey, T.W. Social Support, Inequality, and Homicide: A Cross-National Test of an Integrated Theoretical Model. Criminology 2003, 41, 611–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connell, P.J. The Three Worlds of Welfare Capitalism. By Gosta Esping-Anderson. Soc. Forces 1991, 70, 532–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). Health spending (indicator). doi: 10.1787/8643de7e-en (Accessed on 14 November 2022) https://data.oecd.org/healthres/health-spending.htm.

- United Nations Development Programme. Beyond Income, beyond Averages, beyond Today: Inequalities in Human Development in the 21st Century; United Nations Development Programme (UNDP): Geneva, 2019.

- Hox, J.J. Multilevel Analysis: Techniques and Applications, Second Ed.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers: New Jersey, 2010.

- Snijders, T.A.B.; Bosker, R.J. Multilevel Analysis: An Introduction to Basic and Advanced Multilevel Modeling; Sage Publications: London,; SAGE Publications, 2012.

- Elgar, F.J.; Craig, W.; Boyce, W.; Morgan, A.; Vella-Zarb, R. Income Inequality and School Bullying: Multilevel Study of Adolescents in 37 Countries. J. Adolesc. Heal. 2009, 45, 351–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Condiotional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach (3rd Ed.); The Guilford Press: New York, 2022.

- Chacon, M.; Raj, A. The Association Between Bullying Victimization and Fighting in School Among US High School Students. J. Interpers. Violence 2022, 37, NP20793–NP20815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peltzer, K.; Pengpid, S. Prevalence of Bullying Victimisation and Associated Factors among In-School Adolescents in Mozambique. J. Psychol. Africa 2020, 30, 64–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espelage, D.L.; Basile, K.C.; Leemis, R.W.; Hipp, T.N.; Davis, J.P. Longitudinal Examination of the Bullying-Sexual Violence Pathway across Early to Late Adolescence: Implicating Homophobic Name-Calling. J. Youth Adolesc. 2018, 47, 1880–1893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ostrov, J.M.; Perry, K.J.; Eiden, R.D.; Nickerson, A.B.; Schuetze, P.; Godleski, S.A.; Shisler, S. Development of Bullying and Victimization: An Examination of Risk and Protective Factors in a High-Risk Sample. J. Interpers. Violence 2022, 37, 5958–5984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho, S. Self-Control, Risky Lifestyles, and Bullying Victimization Among Korean Youth: Estimating a Second-Order Latent Growth Model. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2019, 28, 2131–2144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergeron, N.; Schneider, B.H. Explaining Cross-National Differences in PeerDirected Aggression: A Quantitative Synthesis. Aggress. Behav. 2005, 31, 116–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaux, E.; Molano, A.; Podlesky, P. Socio-Economic, Socio-Political and Socio-Emotional Variables Explaining School Bullying: A Country-Wide Multilevel Analysis. Aggress. Behav. 2009, 35, 520–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Espelage, D.L.; Bosworth, K.; Simon, T.R. Examining the Social Context of Bullying Behaviors in Early Adolescence. J. Couns. Dev. 2000, 78, 326–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofstede, G. Culture’s Consequences: Interna- Tional Differences in Work-Related Values. Beverly Hills: Sage Publications.; Cross Cultural Research and Methodology; SAGE Publications, 1980.

- Hong, J.S.; Lee, E.B.; Peguero, A.A.; Robinson, L.E.; Wachs, S.; Wright, M.F. Exploring Risks Associated With Bullying Perpetration Among Hispanic/Latino Adolescents: Are They Similar for Foreign-Born and U.S.-Born? Hisp. J. Behav. Sci. 2022, 43, 365–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mann, M.J.; Kristjansson, A.L.; Sigfusdottir, I.D.; Smith, M.L. The Role of Community, Family, Peer, and School Factors in Group Bullying: Implications for School-Based Intervention. J. Sch. Health 2015, 85, 477–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wills, T.A.; Resko, J.A.; Ainette, M.G.; Mendoza, D. Role of Parent Support and Peer Support in Adolescent Substance Use : A Test of Mediated Effects. Psychol. Addict. Behav. 2004, 18, 122–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harmelen, A. Van; Gibson, J.L.; Clair, M.C.S.; Owens, M.; Brodbeck, J.; Dunn, V.; Lewis, G.; Croudace, T.; Jones, P.B.; Kievit, R.A.; Goodyer, I.M. Friendships and Family Support Reduce Subsequent Depressive Symptoms in At-Risk Adolescents. PLoS One 2016, 11, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shaheen, A.M.; Hamdan, K.M.; Albqoor, M.; Othman, A.K.; Amre, H.M.; Hazeem, M.N.A. Perceived Social Support from Family and Friends and Bullying Victimization among Adolescents. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2019, 107, 104503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cluver, L.; Bowes, L.; Gardner, F. Child Abuse & Neglect Risk and Protective Factors for Bullying Victimization among AIDS-Affected and Vulnerable Children in South Africa ଝ. Child Abuse Negl. 2010, 34, 793–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rivera, M.P.; Depaulo, D. The Role of Family Support and Parental Monitoring as Mediators in Mexican American Adolescent Drinking. Subst. Use Misuse 2013, 48, 1577–1588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Unnever, J.D.; Cornell, D.G. Middle School Victims of Bullying: Who Reports Being Bullied? Aggress. Behav. 2004, 30, 373–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rigby, K.; Bagshaw, D. Prospects of Adolescent Students Collaborating with Teachers in Addressing Issues of Bullying and Conflict in Schools. Educ. Psychol. 2003, 23, 535–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espelage, D.; Polanin, J.; Low, S. Teacher and Staff Perceptions of School Environment as Predictors of Student Aggression, Victimization, and Willingness to Intervene in Bullying Situations. Sch. Psychol. Q. 2014, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mucherah, W.; Finch, H.; White, T.; Thomas, K. The Relationship of School Climate, Teacher Defending and Friends on Students’ Perceptions of Bullying in High School. J. Adolesc. 2018, 62, 128–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pössel, P.; Burton, S.M.; Cauley, B.; Sawyer, M.G.; Spence, S.H.; Sheffield, J. Associations between Social Support from Family, Friends, and Teachers and Depressive Symptoms in Adolescents. J. Youth Adolesc. 2018, 47, 398–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swearer, S.M.; Espelage, D.L.; Koenig, B.; Berry, B.; Collins, A.; Lembeck, P. A Socio-Ecological Model for Bullying Prevention and Intervention in Early Adolescence. In Handbook of school violence and school safety: International research and practice, 2nd ed.; Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group: New York, NY, US, 2012; pp 333–355.

- Yoon, D.; Shipe, S.L.; Park, J.; Yoon, M. Bulling Patterns and Their Associations with Child Maltreatment and Adolescent Psychosocial Problems. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2021, 129, 106178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boulton, M.J.; Murphy, D.; Lloyd, J.; Besling, S.; Coote, J.; Lewis, J.; Perrin, R.; Walsh, L. Helping Counts: Predicting Children’s Intentions to Disclose Being Bullied to Teachers from Prior Social Support Experiences. Br. Educ. Res. J. 2013, 39, 209–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, A.; Yarber, W.L.; Sherwood-Laughlin, C.M.; Gray, M.L.; Estell, D.B. Coping and Survival Skills: The Role School Personnel Play Regarding Support for Bullied Sexual Minority-Oriented Youth. J. Sch. Health 2015, 85, 334–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Individual-level variables (n = 162,792), HBSC Survey 2017-2018 | n | % |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 80181 | 49.3 |

| Female | 82611 | 50.7 |

| Age group | ||

| 11 years | 54291 | 33.3 |

| 13 years | 57295 | 35.2 |

| 15 years | 51206 | 31.5 |

| Traditional bullying victimisation | ||

| Bullied | 46819 | 28.8 |

| Never bullied | 115973 | 71.2 |

| Cyberbullying victimisation | ||

| Cyberbullied | 27456 | 16.9 |

| Never cyberbullied | 135336 | 83.1 |

| Physical fighting -past 12 months | ||

| Engaged in physical fighting | 36602 | 22.5 |

| Never engaged in physical fighting | 126190 | 77.5 |

| Mean | Std. deviation | |

| Age | 13.49 | 1.62 |

| Family affluence | 14.17 | 2.63 |

| Family social support | 22.48 | 6.89 |

| Teacher social support | 6.63 | 2.77 |

| Country-level variables (n = 27) | ||

| Gross domestic product per capita (US$) | 35552.01 | 15050.50 |

| Education spending | 8.48 | 1.77 |

| Null (Empty) Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | |

| Variable | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) |

| Age (reference: 11-year-olds) | 1.00 (1.00-1.00) | 1.00 (1.00-1.00) | 1.00 (1.00-1.00) | 1.00 (1.00-1.00) | |

| 13-year-olds | 0.90*** (0.87-0.92) | 0.89*** (0.87-0.92) | 0.88*** (0.85-0.91) | 0.88*** (0.85-0.90) | |

| 15-year-olds | 0.70*** (0.67-0.72) | 0.68*** (0.66-0.71) | 0.67*** (0.65-0.69) | 0.66*** (0.64-0.69) | |

| Gender (reference: male) | 1.20*** (1.17-1.23) | 1.18*** (1.15-1.20) | 1.19*** (1.16-1.22) | 1.18*** (1.15-1.21) | |

| Family affluence | 1.40*** (1.37-1.44) | 1.35*** (1.32-1.39) | 1.40*** (1.36-1.43) | 0.96*** (0.96-0.97) | |

| Physical fighting | 2.48*** (2.42-2.54) | 3.35*** (3.20-3.52) | 3.00*** (2.89-3.10) | 2.43*** (2.36-2.50) | |

| Family social support (FSS) | 0.72*** (0.69-0.75) | 0.56*** (0.55-0.58) | |||

| Teacher social support (TSS) | 1.30*** (1.26-1.34) | 1.08*** (1.06-1.11) | |||

| FSS x Physical fighting | 0.63*** (0.59-0.66) | ||||

| TSS x Physical fighting | 0.70*** (0.67-0.73) | ||||

| GDP per capita | 0.90*** (0.89-0.91) | ||||

| Education spending | 0.87*** (0.83-0.91) | ||||

| Education spending x Physical fighting | 0.91*** (0.87-0.97) | ||||

| Random variances | |||||

| Country | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.08 | 0.06 | 0.06 |

| School | 0.25 | 0.22 | 0.20 | 0.22 | 0.18 |

| Intraclass correlations (ICC) | |||||

| Country | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.01 |

| School | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.04 |

| Goodness-of-fit | |||||

| AIC | 742213.89 | 738703.30 | 740613.35 | 739302.27 | 741436.08 |

| BIC | 742233.89 | 738723.30 | 740633.35 | 739322.27 | 741456.08 |

| Null (Empty) Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | |

| Variable | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) |

| Age (reference: 11-year-olds) | 1.00 (1.00-1.00) | 1.00 (1.00-1.00) | 1.00 (1.00-1.00) | 1.00 (1.00-1.00) | |

| 13-year-olds | 1.01 (0.98-1.05) | 1.00*** (0.97-1.04) | 1.01 (0.97-1.04) | 1.01 (0.98-1.05) | |

| 15-year-olds | 0.93*** (0.89-0.96) | 0.91*** (0.87-0.94) | 0.91*** (0.87-0.94) | 0.92*** (0.88-0.95) | |

| Gender (reference: male) | 1.46*** (1.42-1.51) | 1.43*** (1.39-1.47) | 1.44*** (1.40-1.48) | 1.45*** (1.41-1.49) | |

| Family affluence | 1.42*** (1.37-1.46) | 1.34*** (1.30-1.38) | 1.34*** (1.30-1.38) | 0.97*** (0.97-0.98) | |

| Physical fighting | 3.28*** (3.19-3.38) | 4.90*** (4.65-5.17) | 3.85*** (3.69-4.01) | 3.12*** (3.02-3.22) | |

| Family social support (FSS) | 0.61*** (0.58-0.64) | 0.41*** (0.40-0.42) | |||

| Teacher social support (TSS) | 1.23*** (1.18-1.28) | 0.95*** (0.92-0.98) | |||

| FSS x Physical fighting | 0.51*** (0.48-0.54) | ||||

| TSS x Physical fighting | 0.65*** (0.61-0.68) | ||||

| GDP per capita | 0.91*** (0.89-0.93) | ||||

| Education spending | 0.81*** (0.76-0.86) | ||||

| Education spending x Physical fighting | 0.98 (0.92-1.05) | ||||

| Random variances | |||||

| Country | 0.07 | 0.08 | 0.11 | 0.11 | 0.08 |

| School | 0.19 | 0.22 | 0.18 | 0.18 | 0.16 |

| Intraclass correlations (ICC) | |||||

| Country | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.01 |

| School | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.02 |

| Goodness-of-fit | |||||

| AIC | 823369.47 | 807625.93 | 812125.66 | 816890.07 | 816503.97 |

| BIC | 823389.47 | 807645.93 | 812145.66 | 816910.07 | 816523.97 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).