1. Introduction

Bullying is a common form of youth violence that affects adolescents worldwide. Involvement in bullying impacts youth social development and can lead to negative outcomes, including problems with school adjustment, academic success, and peer relationships (Bae, 2018; Armitage, 2021), as well as psychosocial problems such as low self-esteem, depression, anxiety, and suicidality (Chen et al., 2022; Kim & Lee, 2010; Olweus, 1993). For some, the effects of bullying continue well into adulthood, impacting interpersonal relationships and social adjustment (Hugh-Jones & Smith, 1999). Therefore, addressing bullying violence is a critical issue for youth development and ultimately healthy and productive adulthood (Ann & Jeong, 2017).

As a global problem, bullying violence affects youth in many cultural contexts (Johansson et al., 2022); additionally, national comparative research has found that while prevalence rates differ across countries, the consequences of bullying involvement are similar (Seo et al., 2017). In South Korea, bullying has received increased attention due to several incidents of youth suicide where bullying was a precipitating factor (Seo et al., 2018). Among South Korean youth, prevalence rates of bullying are high, ranging from approximately 10% to 60% of youth self-reported involvement with school bullying as a bully, a victim, or both (Park et al., 2017; Seo et al., 2017). Studies of youth bullying in South Korea have also identified prevalence rates to be highest in the upper elementary and middle school years, tapering off in high school (You et al., 2014; Seo et al., 2017).

Several factors have been identified that might increase a youth’s exposure to bullying involvement, including stressful family environments and maltreatment (Veenstra et al., 2005). Within the family context, adverse childhood experiences, including abuse, neglect, and conflict within the home, have been found to place children at risk for peer victimization at school (Hsieh et al., 2021; O’Hara et al., 2021; Yoon et al., 2021). Based on social learning theory, experiencing abusive, neglectful, or coercive parenting impacts a child’s perception of healthy interpersonal relationships, which may limit their ability to form positive relationships with peers (Murphy et al., 2017; Walden & Beran, 2010). This, in turn, puts a child at risk of experiencing bullying victimization (Park, Grogan-Kaylor, & Han, 2021). In a meta-analysis synthesizing over 70 studies of parenting behavior and its relationship to bullying experiences, maladaptive parenting was found to be positively related to bullying victimization (Lereya et al., 2013).

Research on youth growing up in alternative care settings, specifically orphanages (also referred to as institutional care), and experiences of bullying victimization is limited, even though they may be at greater risk of being bullied, given family risk factors. In the context of South Korea, most youth enter into orphanages because of parental divorce and discord, remarriage, economic hardship, and abuse (Lee et al., 2010). In addition, while orphanage facilities in South Korea are well maintained and adequately provide the basic health, nutrition, and environmental stimulation necessary to prevent global developmental failure, there is frequent turnover of staff resulting in multiple caregivers (Lee et al, 2010). Hence, youth in orphanages may be exposed to additional adversity arising from maladaptive parenting, leading them to enter alternative care, challenges from separation from biological parents, and a lack of long-term, stable relationships with consistent caregivers while in care. This interruption in the development of a secure attachment to a caring adult may make them potentially more susceptible to problems with peers and school bullying victimization (Park et al., 2021).

Given the potential risk factors among adolescents in orphanage care, it is important to understand whether they may be more or less likely to experience bullying victimization than their peers. Emerging research has found higher rates of peer bullying compared to rates in the general school population among South Korean elementary school-aged children who used child welfare facilities (orphanages, group homes, community child centers). In one study, the rate of peer bullying among younger children (ages 6 to 9) was 22%, and for older children (ages 10 to 12) was 12% (Kim et al., 2015). In another study utilizing data from the Panel Study of Korean Children in Out-of-Home Care (PSKCOC), among pre-teens (ages 11 and 12) there were differences in rates of bullying victimization by child care type, with those in group homes experiencing the most, followed by youth in orphanage care, and the lowest among those in foster care (Kang & Kang, 2019). Less research has focused on adolescents (12 and older) in orphanage care and their experiences of bullying victimization.

Research has also identified a number of school-related factors associated with increased risk of bullying victimization and lower school outcomes, including negative school climate and student disconnectedness (Blitz & Lee, 2015; O’Brennan & Furlong, 2010). Studies in South Korea have similarly found bullying victimization to be correlated with lower school engagement and achievement (Choi et al., 2019; Kim, 2011; Sunwoo & Lee, 2014). Research in South Korea has found that factors important for academic achievement are lower among youth in orphanage care. For example, studies of younger children in orphanage facilities found they reported significantly lower school life satisfaction (Park & Moon, 2009), as well as more difficulties with school engagement and peer relationships than those raised in healthy biological families (Son & Byeon, 2007).

Among several factors associated with bullying victimization, adverse childhood experiences within the family context, particularly child maltreatment, have been consistently linked with heightened risk (Veenstra et al., 2005; Hsieh et al., 2021). Maltreatment experiences, including physical and emotional abuse and neglect, impair children's ability to develop healthy interpersonal relationships, increasing their susceptibility to peer victimization at school (Murphy et al., 2017; Walden & Beran, 2010). A meta-analysis of over 70 studies has affirmed the strong association between maladaptive parenting behaviors and bullying victimization (Lereya et al., 2013).

Youth residing in institutional settings, such as orphanages, may represent a particularly vulnerable group regarding bullying victimization. In South Korea, children are often placed into orphanage care due to family disruptions, economic hardship, or abuse, factors which independently increase vulnerability to maltreatment and subsequent bullying victimization (Lee et al., 2010). Additionally, the frequent turnover of staff in orphanage settings can result in unstable caregiving relationships, exacerbating emotional and social vulnerabilities among these youth (Park et al., 2021). Despite these risks, limited research has focused specifically on adolescents in orphanage care and their bullying experiences compared to their peers in the general population.

Previous studies indicate that bullying victimization negatively impacts school-related outcomes, particularly school engagement. Research consistently shows that bullying victimization correlates with reduced school engagement and poorer academic achievement among South Korean adolescents (Choi et al., 2019; Kim, 2011; Sunwoo & Lee, 2014). For children in orphanage care, these outcomes may be further compromised by pre-existing vulnerabilities related to maltreatment, insecure attachments, and inconsistent caregiving environments (Son & Byeon, 2007).

Given the identified gaps in existing research, particularly regarding adolescents in orphanage care, this study aims to explore bullying victimization and its relationship with child maltreatment on school engagement among South Korean adolescents residing in orphanages compared to a national representative sample. Specifically, the study addresses the following research questions: 1) Do adolescents in orphanage care experience higher levels of bullying victimization compared to their peers? 2) Is child maltreatment associated with bullying victimization and school engagement? 3) Does bullying victimization mediate the relationship between child maltreatment and school engagement?

Utilizing social learning theory as a guiding framework, we hypothesized that adolescents in orphanage care would exhibit higher rates of bullying victimization, and that greater bullying victimization would be associated with lower levels of school engagement. Further, we hypothesized that bullying victimization would significantly mediate the relationship between child maltreatment and reduced school engagement. This research contributes to our understanding of how adverse childhood experiences and peer relationships intersect to influence educational engagement and highlights the importance of developing targeted interventions to support vulnerable youth populations.

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

Data for this cross-sectional study were obtained by merging the 7th wave (n=521) of the Korean Welfare Panel Study (KoWePS) and a study of 170 Korean youth living in institutional care (McGinnis, 2021). KoWePS is a national longitudinal panel study that began in 2006 and was conducted by the Korea Institute for Health and Social Affairs and Seoul National University (KIHASA, 2012). Data are collected annually on households (parent report) and an oversampling of low-income families, relating to their welfare status, economic conditions, and social security, with additional surveys conducted with people with disability and youth in various years. In the initial wave 1, conducted in 2006, a national random sample of 7,027 households were surveyed, including surveys administered directly to the children of each household (n=759). Self-reported child data were also collected at wave 4 in 2009 (n=609), and at wave 7 in 2012 (n=521), with the attrition of the total number of households falling by 74.53% from the first wave.

Wave 7 of KoWePS was chosen for this study because data were collected around the same time as the data of 170 adolescents residing in 10 institutions in the Seoul Metropolitan Area and a southern province collected between March 2014 and January 2015. The convenience sample of adolescents in orphanage care was collected as part of another cross-sectional study examining school and mental health problems that included maltreatment, behavioral problems, and school measures from the KoWePS self-report surveys of youth in households (McGinnis, 2021). Furthermore, KoWePS Wave 7 youth were similar in age to the adolescents in orphanage care, most being high school students (10th to 12th graders in the U.S.), including youth who had dropped out or were on a leave of absence from school.

Adolescents in orphanage care who were younger than 12 years old were excluded from the current study, so the ages were more similar in both datasets. Data from Wave 7 of the KoWePS supplementary youth survey (n=521) were merged with the adolescents in orphanage care (n=154) to create a new dataset of youth (n=675) that were analyzed for the present study.

2.2. Measures

School Engagement. The measure of students’ perceived psycho-social engagement in school consisted of nine items: school being fun, liking to learn most subjects, respect for most teachers, having a good attitude, regularly doing homework, following teacher’s instructions, attempts to quit school, cheating on an exam, and leaving class without permission. The 3-point Likert responses ranged from 0 (not at all) to 3 (always). The measure was summed, with higher scores indicating more school engagement. The Cronbach’s alpha was 0.75 and was considered to have reliable internal consistency (Nunnally &Bernstein, 1994).

Bully Victimization. This peer victimization scale consisted of six items: verbal aggression (being teased or verbally taunted), relational aggression (intentionally being excluded; spreading bad rumors), intimidation (for not doing what another student wanted them to do; being intimidated or scared for money or property), and physical aggression (being hit, kicked or punched by other children). All responses were on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from not at all (0) to always (3). All items were summed so that higher scores indicated more frequent bullying victimization. The coefficient of internal consistency was 0.671 and considered to be good.

Child Maltreatment. The mediator variable was maltreatment by a caregiver or parent in the past year. The scale consisted of 8 items capturing physical (i.e., “I have been hit badly by my caregiver”, emotional abuse (i.e., “My parents made me feel shame and humiliation”), and neglect (i.e., “My parents notice if I need things”). Responses were a 5-point Likert scale ranging from never (0), once or twice per year (1), once or twice per 2-3 months (2), once or twice per month (3), about once or twice per week (4). Cronbach's alpha was excellent at 0.773 (Nunally & Bernstein, 1994). The measure was summed so that higher scores indicated more frequent exposure to child maltreatment.

Control Variables. Three variables were controlled for that were likely to influence the relationship between bullying victimization and school engagement: age, gender, academic performance (mean score across all subjects), and orphanage care or national sample (KoWeps). Age was treated as a continuous variable calculated by the student’s date of birth and the time they participated in the study. Gender was treated dichotomously as male (0) and female (1). A dichotomous variable was created for participants in the national dataset (0 = national) and the orphanage group (1=orphanage) to compare youth in orphanage care and the national sample.

2.3. Analytic Methods

Stata 17.0 MP and Software Package for Social Science (SPSS) 27.0 were used for data analysis. The KoWeps dataset was limited to variables of interest that matched the orphanage group dataset (school engagement, maltreatment, and bullying victimization), and the orphanage dataset was limited to youth aged 12 and older. Then, the two datasets were merged together to create one dataset (n=675). After merging the datasets, the final dataset was checked for duplicate data and formatted.

Univariate statistics were run to describe the demographics and characteristics of the study. Next, bivariate statistics were used to identify the association between the variables of interest. A simple mediation analysis was conducted using PROCESS MACRO. Multiple regression analysis was run to verify the mediation effects of child maltreatment between bullying victimization and school engagement, controlling for demographic variables and group. To test the mediation effect, 5,000 bootstrap resamples were conducted.

3. Results

3.1. Demographic Characteristics

The sample from the national KoWeps dataset comprised 521 adolescents, ranging from 12 to 19 years old

(M=16.86 years,

SD=0.89) (

Table 1). Participants were 270 males (51.8%) and 251 females (48.2%). Most youth were attending high school (95.2%), and the percentage of school drop-outs and leave of absence (4.8%) was low. Nearly the full KoWeps sample (94%) were living with the family.

The sample size of adolescents in orphanage care in this study was 154 youths, ranging in age from 12 to 19 years old (M = 15.03 years, SD = 1.86). Of these youth, 107 were male (69.5%) and 47 were female (30.5%). In addition, 57.1% were in middle school and 42.9% were in high school. The dominant reason for placement in the orphanage was parental absence or inability (70.2%) and marital problems (29.8%). Excluding non-responses, the average academic performance mean scores were 3.01 (SD=0.97) for the KoWeps group (n=496) and 2.44 (SD=1.13) for the orphanage group (n=154).

3.2. Group Differences: Maltreatment, Bullying Victimization, and School Engagement

Group differences between youth in orphanages and the national sample (KoWeps) and types of maltreatment are reported in

Table 2. Among the the items, youth in the orphanage groups showed statistically significantly higher mean scores (at a

p value of .10) than the KoWeps group on two of the three items related to emotional abuse [“Parents told me ‘if only could be better’ (

t=1.717,

p=.087)”, “Parents told me I was stupid, idiot (

t=1.975,

p=.049)] and two of the four items related to neglect [“Parents won’t say anything if I was absent from school (

t=-2.016,

p=.045)”; “Parents notice if I need things like money or material things (

t=-1.688,

p=.093)”].

Results of the

t-test analysis for between-group differences on all the variables in the study are presented in

Table 3. The orphanage group had statistically significantly higher mean scores on school bullying victimization (

t=-3.589,

p<.001) than the KoWeps group. Otherwise, the mean score on school engagement (

t=2.907,

p=.004) was statistically higher in the KoWeps group than the orphanage group.

Table 4 presents the results of the

Pearson correlation analysis among all study variables. Higher levels of school bullying victimization were significantly correlated with, lower school engagement (

r=-.240,

p<.01), higher maltreatment (

r =.283,

p<.01), younger age (

r=-.112,

p<.01), male gender (

r=-.093,

p<.05), belonging to the orphanage group (

r=.184,

p<.01), and lower academic achievement (

r=-.140,

p<.01).

Higher school engagement was significantly correlated with belonging to the national sample group (r=-.127, p< .01), higher academic achievement (r=.457, p<.01), lower school bullying victimization (r=-.240, p<.01), and lower maltreatment (r=-.186, p<.01).

3.3. Mediating Effect of Bullying Victimization on the Relationship Between School Child Maltreatment and School Engagement

The multiple regression models were conducted to test the mediation effect of school bullying victimization (

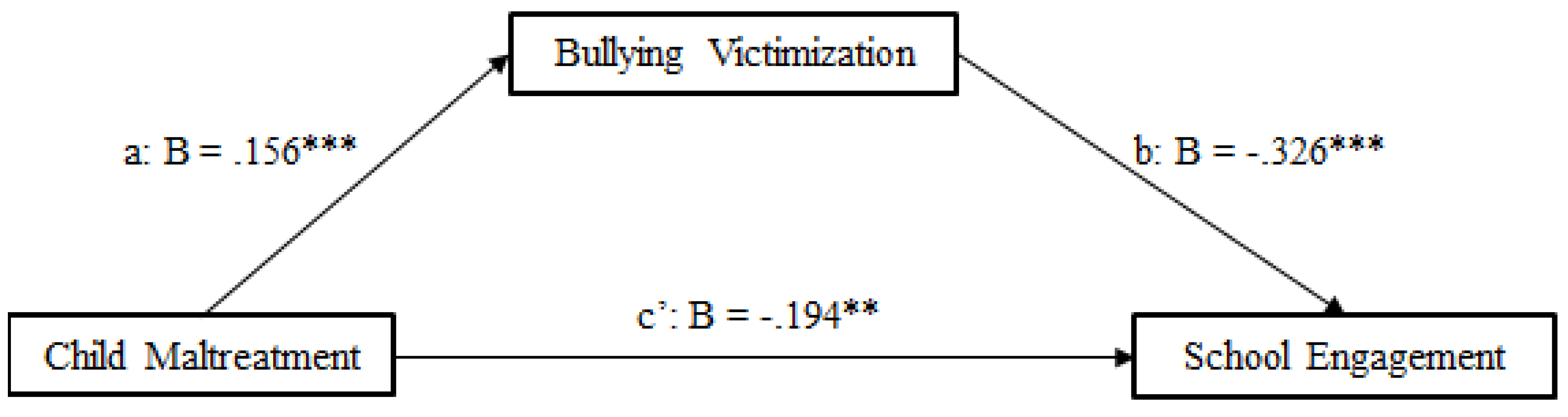

Table 5). The results of the mediated multiple regression analysis provide strong evidence for a significant indirect pathway linking child maltreatment to school engagement through school bullying victimization. In Model 1, child maltreatment was found to significantly predict higher levels of school bullying victimization (B = 0.156, p < .001), suggesting that adolescents who experience maltreatment are more likely to be involved in bullying. Additionally, youth residing in orphanages reported significantly more bullying experiences compared to those in the general population (B = 0.586, p < .01). In Model 2, school bullying victimization was shown to significantly reduce school engagement (B = -0.326, p < .001), and child maltreatment also had a direct negative effect on school engagement (B = -0.143, p < .01). Furthermore, grade level was positively associated with school engagement (B = 1.491, p < .001). In Model 3, when school bullying victimization was excluded, the effect of child maltreatment on school engagement became stronger (B = -0.194, p < .001), suggesting that bullying partially mediates the relationship between maltreatment and engagement.

Child maltreatment had a significant total effect on school engagement (B = –0.194, SE = 0.043, t = –4.483, p < .001). When peer bullying victimization was included as a mediator, the direct effect of child maltreatment on school engagement remained significant (B = –0.143, SE = 0.045). The indirect effect through bullying was also statistically significant (B = –0.050, SE = 0.018), with a 95% bootstrap confidence interval that did not include zero [–0.090, –0.019], indicating a meaningful mediation effect. These findings suggest that bullying victimization partially mediates the relationship between child maltreatment and school engagement, consistent with theoretical expectations.

Figure 1.

Mediated Model. Note. The confidence interval for the indirect effect is a bias-corrected bootstrapped CI based on 5000 samples. Indirect effect of Child Maltreatment on School Engagement through Bullying Victimization: (path) a*b, Direct effect of Child Maltreatment on School Engagement: (path) c’. a*b: β =-.05*** [95% CI:-.075, -.014]. **p<.01, ***p<.001.

Figure 1.

Mediated Model. Note. The confidence interval for the indirect effect is a bias-corrected bootstrapped CI based on 5000 samples. Indirect effect of Child Maltreatment on School Engagement through Bullying Victimization: (path) a*b, Direct effect of Child Maltreatment on School Engagement: (path) c’. a*b: β =-.05*** [95% CI:-.075, -.014]. **p<.01, ***p<.001.

4. Discussion

This study aimed to extend knowledge on school peer bullying victimization among a vulnerable population of youth, adolescents residing in orphanage care, and to compare their experiences to a national sample of adolescents in South Korea. In addition, this study sought to contribute to the understanding of how risk factors, such as bullying victimization and maltreatment, are related to important protective factors in schools (i.e., school engagement) that ultimately contribute to educational achievement and well-being.

Our hypothesis, stating that adolescents in orphanage care would experience greater bullying victimization compared to the general adolescent population, was confirmed. The adolescents in orphanage care in this study were all attending schools in the communities in which the facility was located. Based on prior research and cumulative risk theory, it was thought that maltreatment, in addition to neglect, may place adolescents in orphanages at greater risk for peer bullying victimization. Children with maltreatment histories often experience difficulties managing emotions and behaviors, potentially increasing their vulnerability to peer victimization (Hong, Kim, & Piquero, 2017). Maltreatment-related emotional dysregulation and difficulties in interpersonal relationships may exacerbate negative peer interactions and ultimately decrease school engagement (Gross, 2015; Hong et al., 2018).

However, there was no statistically significant difference in the mean scores on maltreatment in the past year between youth in orphanages and the national sample. It may be that the statistically higher mean scores on peer bullying victimization were partly because of age differences between the samples. In the national sample, almost the entire group of adolescents were in high school, whereas in the sample of youth in orphanage care, 57.1% were in middle school and 42.9% were in high school. Other studies of school bullying victimization in South Korea have found age differences in the incidence of school bullying victimization, with rates higher in middle school than high school. For instance, in one study, the rates were highest among youth in the 6th grade of primary school and the 1st grade of middle school, equivalent to the U.S. educational system for middle school grades 6th and 7th (Kang, 2013). This was consistent with findings in another study of 2,936 South Korean students by Seo and colleagues (2017) that found prevalence rates of bullying victimization by age group were highest among students in the upper elementary school levels (ages 10-12), followed by middle school (ages 13-14; 8.3%) and high school (ages 15-17; 6.4%).

It could also be that adolescents in orphanage care are more vulnerable to being victims of peer bullying because of their living situation in an orphanage. One culturally specific form of bullying in South Korea is called wang-tta, meaning a person targeted for being bullied (Lee, Smith, & Monks, 2011). In one qualitative study of adolescents in South Korean orphanages, youth reported they struggled to reveal to their peers about their status of living in an orphanage out of fear of being ridiculed and becoming a wang-tta (Chung, Kim, & Yang, 2015).

Adolescents in orphanage care in the present study also had average scores that were statistically lower on school engagement. This finding may be explained by Bowlby’s (1973; 1988) and Ainsworth’s (1982) attachment theory. Children who experience relational trauma and disruptions from attachment figures are more likely to develop insecure styles of attachment. This can include indiscriminate attachment disorders in which a child may lack appropriate social boundaries or be overly friendly with strangers, which may be distorted perceptions of social support (i.e., perceiving there to be more social support than there is). Insecure attachment has been found to be associated with externalizing behavior problems (see meta-analysis by Van IJzendoorn, Schuengel, & Bakermans-Kranenburg, 1999), as well as difficulty regulating emotions, including affective connections that may affect school engagement.

Study findings on the negative correlation between maltreatment, bullying victimization, and school engagement align with previous literature, indicating that negative social experiences in the school environment impact students’ engagement in school (Kim & Lee, 2018; Sunwoo & Lee, 2014). The negative correlation between bullying victimization and school engagement highlights the importance of fostering a safe and supportive school environment. Consistent with prior studies, students who experience maltreatment and bullying may exhibit reduced enthusiasm for school life, potentially adversely affecting overall academic achievement (Kang & Kang, 2019) and school engagement (Kim & Lee, 2018; Sunwoo & Lee, 2014).

The present study also aimed to elucidate the mediating role of bullying victimization in the relationship between child maltreatment and two critical school variables, and school engagement. The mediation analyses conducted confirmed our hypothesis, demonstrating that bullying victimization indeed serves as a significant mediator between the experience of child maltreatment and the level of engagement in school activities. These findings highlight the intricate interplay between bullying victimization experiences and the broader psychosocial environment of the children. Specifically, it was observed that the negative consequences of bullying victimization extend beyond immediate psychological distress, permeating into the children's relationships with their engagement with the school environment. This study suggests that child maltreatment exacerbates experiences of bullying victimization, which in turn erodes diminishes students' active participation in their school engagement.

Similarly, the mediating effect of bullying victimization on school engagement underscores the profound influence of adverse interpersonal experiences on a child's motivation and ability to engage with learning. This is particularly concerning as it suggests a cumulative disadvantage for bullied children, where not only do they contend with the direct psychological impacts of bullying, but their capacity to benefit from educational opportunities is concurrently impaired. This may have far-reaching implications for their academic trajectories and overall life chances (Fantuzzo & Perlman, 2007; Park et al., 2021). Moreover, the inclusion of age, gender, academic performance, and orphanage group status as variables in the models 1 and 2 of the multiple regression analyses underscores the importance of considering demographic factors and life circumstances in understanding the experiences of maltreated and bullied children. The compounded negative effects of these demographic factors highlight the need for targeted interventions that address the unique vulnerabilities of these populations.

4.1. Implications for Practice and Policy

Social workers, educators, and policymakers should utilize the findings of the study to support and promote policies that acknowledge and address the complexities of bullying victimization and child maltreatment, and the need to attend to vulnerable populations of youth, such as those who are in alternative care settings like orphanage care. This entails not only establishing policies to protect children from such encounters but also comprehensive practices that address the far-reaching consequences of bullying on children's educational experiences and their wider social interactions.

The efficacy of multifaceted interventions aimed at mitigating school violence remains inadequately assessed, despite the concerted efforts of governmental entities, non-governmental organizations, community stakeholders, and educational institutions in South Korea. These initiatives, including the implementation of legislative frameworks for the prevention and management of school violence, have attempted to incorporate pedagogical perspectives, victim-offender considerations, and the idiosyncratic nature of school-based aggression. However, the practical application and enforcement of these measures have not yielded demonstrably positive outcomes, calling into question their overall effectiveness in addressing this complex social issue (Jung & Lee, 2017).

Thus, there is a need to advocate for legislative measures that promote comprehensive anti-bullying initiatives and facilitate the integration of social work services within educational institutions. The development of such policies should be informed by empirical evidence and incorporate insights from practicing social workers, youth with lived experiences, and educators, thereby reflecting the pragmatic realities and exigencies of the field. One suggestion of a comprehensive anti-bullying initiative is that upon identification of bullying victimization or child maltreatment incidents, a prompt, coordinated, and tailored response be implemented, leveraging educational, legal, and therapeutic resources to address the unique needs of affected children.

There exists a pressing need for policies that enable the seamless integration of educational and social service systems in South Korea. There is a need for budgetary provisions that not only ensure the presence of social workers in educational settings but also facilitate the establishment of programs offering sustained support to children who have experienced bullying and maltreatment. Additionally, policy considerations should encompass provisions for the ongoing professional development of social workers, ensuring they possess the requisite knowledge and skills to effectively address the evolving challenges of bullying and maltreatment within the school milieu. Through the provision of practical guidance and influence on policy formulation, social workers can make significant contributions towards mitigating the adverse effects of bullying victimization and child abuse on children. These efforts are directed towards fostering a safe, supportive, and engaging educational environment for all students.

4.2. Limitations

Although the study had many strengths, it also had several limitations. First, the two samples were collected at different times. The national youth group sample was collected in 2012, while the orphanage group youth sample was collected between 2014 and 2015. Second, this study used cross-sectional data. Therefore, it was hard to clarify any causal relationship between the variables. Future studies need to consider longitudinal methods to identify any causal relationships. Third, the Cronbach's alpha for some study measurements was slightly below the acceptable level. In general, over .7 has been treated as acceptable internal consistency; however, measurements of school engagement and bullying victimization had Cronbach’s alpha under .7, respectively. Future studies need to address these measurement limitations.

4.3. Conclusion

This study highlights the complex interactions between child maltreatment, bullying victimization, and school engagement among South Korean youth, especially those in orphanage care. Our findings demonstrate that bullying victimization significantly mediates the negative relationship between child maltreatment and school engagement. This underscores the extensive impact of maltreatment and bullying on students' educational experiences and relationships. The study also emphasizes the unique vulnerabilities of youth in orphanage care and calls for targeted interventions and integrated policies to address these issues comprehensively. Our research underscores the critical need for safe and supportive school environments to improve the well-being and educational outcomes of all children, but most especially for the most vulnerable of children.

Declaration of interest

None.

References

- Ainsworth, M. D. S. (1982). Attachment: Retrospect and prospect. In C. M. Parkes & J. Stevenson-Hinde (Eds.), The place of attachment in human behavior (pp.3-30). New York: Basic Books.

- Ann, E. M., & Jung, I. J. (2017). The effect of the school violence victimization on school violence perpetration: A focus on the moderating effect of negative attitudes of peer group and difference between General Adolescents and Adolescents in Out-of-Home Care. Journal of Social Sciences. 28(4), 157-180. [CrossRef]

- Armitage, R. (2021). Bullying in children: impact on child health. BMJ Pediatrics Open, 5(1), e000939–e000939. [CrossRef]

- Bae, S. M. (2016). The influences of emotional problem, delinquency, academic stress, and career maturity on suicidal thoughts of high school students. Korean Journal of Youth Studies, 23(6), 317-332. http://www.dbpia.co.kr/journal/articleDetail?nodeId=NODE06716535.

- Bandura, A. (1973). Aggression: A social learning analysis. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

- Benedini, K. M., Fagan, A. A., Gibson, C. L. (2016). The cycle of victimization: The relationship between childhood maltreatment and adolescent peer victimization. Child Abuse & Neglect, 59, 111-121. [CrossRef]

- Blitz, L. V., & Lee, Y. (2015). Trauma-informed methods to enhance school-based bullying prevention initiatives: An emerging model. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma, 24(1), 20-40. [CrossRef]

- Bowlby, J. (1973). Attachment and loss: Vol. 2. Separation: Anxiety and anger. New York: Basic Books.

- Bowlby, J. (1988). A secure base: Parent-child attachment and healthy human development. New York: Basic Books.

- Bussemakers, C., & Denessen, E. (2024). Teacher support as a protective factor? the role of teacher support for reducing disproportionality in problematic behavior at school. The Journal of Early Adolescence, 44(1), 5–40. [CrossRef]

- Chen, H., Guo, H., Chen, H., Cao, X., Liu, J., Chen, X., Tian, Y., Tang, H., Wang, X., & Zhou, J. (2022). Influence of academic stress and school bullying on self-harm behaviors among Chinese middle school students: The mediation effect of depression and anxiety. Frontiers in Public Health, 10. [CrossRef]

- Chen, J. J.-L. (2005). Relation of Academic Support From Parents, Teachers, and Peers to Hong Kong Adolescents’ Academic Achievement: The Mediating Role of Academic Engagement. Genetic, Social, and General Psychology Monographs, 131(2), 77–127. [CrossRef]

- Cho, Y. (2013). Gender differences in prevalence and predictors of school violence. Journal of Adolescent Welfare, 15(1), 155 – 179.

- 14. Choi, W. S., Ann, J. J., Byun, M. H., & Kwon, J. S. (2019). Factors influencing the school adaptation of South Korean domestic adopted children, Journal of Korean Council for Children & Rights, 23(3), 553-578. https://doi.org/10.21459/kccr.2019.23.3.553 Chung, I.J., Kim, S.H., & Yang, E.B. (2015). Life experience of academically successful children in residential care: Children living at the boundary of the center and periphery. Journal of Korean Society of Child Welfare, 50, 55-84.

- Crosnoe, R., Johnson, M. K., & Elder Jr, G. H. (2004). Intergenerational bonding in school: The behavioral and contextual correlates of student-teacher relationships. Sociology of education, 77(1), 60-81. [CrossRef]

- Emirtekin, E., Balta, S., Kircaburun, K., & Griffiths, M. D. (2020). Childhood emotional abuse and cyberbullying perpetration among adolescents: The mediating role of trait mindfulness. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 18(6), 1548–1559. [CrossRef]

- Espelage, Polanin, J. R., & Low, S. K. (2014). Teacher and staff perceptions of school environment as predictors of student aggression, victimization, and willingness to intervene in bullying situations. School Psychology Quarterly, 29(3), 287–305. [CrossRef]

- Fantuzzo, J., & Perlman, S. (2007). The unique impact of out-of-home placement and the mediating effects of child maltreatment and homelessness on early school success. Children and Youth Services Review, 29(7), 941–960. [CrossRef]

- Felix, E. D., Sharkey, J. D., Green, J. G., Furlong, M. J., & Tanigawa, D. (2011). Getting precise and pragmatic about the assessment of bullying: The development of the California bullying victimization scale. Aggressive Behavior, 37(3), 234–247. [CrossRef]

- Flaspohler, P. D., Elfstrom, J. L., Vanderzee, K. L., Sink, H. E., & Birchmeier, Z. (2009). Stand by me: The effects of peer and teacher support in mitigating the impact of bullying on quality of life. Psychology in the Schools, 46(7), 636-649. [CrossRef]

- Font, S. A., & Berger, L. M. (2015). Child maltreatment and children’s developmental trajectories in early to middle childhood. Child Development, 86(2), 536–556. [CrossRef]

- Grasgreen, A. L., & Lauer, P. A. (2011). Social capital and school bullying: An ecological analysis. Journal of School Violence, 10(4), 374-393.

- Gregory, Cornell, D., & Fan, X. (2011). The Relationship of school structure and support to suspension rates for Black and White high school students. American Educational Research Journal, 48(4), 904–934. [CrossRef]

- Gross, J. J. (2015). Emotion regulation: Current status and future prospects. Psychological Inquiry, 26(1), 1–26. [CrossRef]

- Hong, F., Tarullo, A. R., Mercurio, A. E., Liu, S., Cai, Q., & Malley-Morrison, K. (2018). Childhood maltreatment and perceived stress in young adults: The role of emotion regulation strategies, self-efficacy, and resilience. Child Abuse & Neglect, 86, 136–146. [CrossRef]

- Hong, J.S., Kim, D.H., Piquero, A. R. (2017). Assessing the links between punitive parenting, peer deviance, social isolation and bullying perpetration and victimization in South Korean adolescents. Child Abuse & Neglect, 73, 63-70. [CrossRef]

- Hong, S. H., & Noh, H. K., (2013). Estimating latent classes in male adolescents’ online game time trajectories and testing relationship with delinquency, Studies on Korean Youth, 24(4), 119-148.

- Hsieh, Y. P., Shen, A. C. T., Hwa, H. L., Wei, H. S., Feng, J. Y., & Huang, S. C. Y. (2021). Associations between child maltreatment, dysfunctional family environment, post-traumatic stress disorder and children’s bullying perpetration in a national representative sample in Taiwan. Journal of family violence, 36(1), 27-36. [CrossRef]

- Hugh-Jones, S., & Smith, P. K. (1999). Self-reports of short- and long-term effects of bullying on children who stammer. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 69(2), 141–158. [CrossRef]

- Johansson, S., Myrberg, E., & Toropova, A. (2022). School bullying: Prevalence and variation in and between school systems in TIMSS 2015. Studies in Educational Evaluation, 74, 101178-. [CrossRef]

- Kang, H. J., & Kang, H. A., (2019). School violence victimization and perpetration among children in different types of out-of-home care: The buffering effects of protective factors. Korean Society of Child Welfare, 67, 163-192. [CrossRef]

- Kim, H. T., & Lee, S. C. (2018). Influence of teachers on adaptation of children at foster care, group home and child care facilities, The Korean Society Of Health And Welfare, 20(4), 55-79. [CrossRef]

- Kim, H. J., & Lee, B. H. (2007). Effects of family background, social capital and cultural capital on the children's academic performance. Korea Journal of Population Studies, 30(1), 125-148.

- Kim, H. W. (2011). Psychological and School Maladjustment resulted by peer rejection and peer victimization among elementary, middle, and high school students. Korean Journal of Youth Studies, 18(5), 321-356.

- Kim, J.W., Lee, K., Lee, Y.S., Han, D.H., Min, K.J, Song, S.H., . . .Kim, J.O. (2015). Factors associated with group bullying and psychopathology in elementary school students using child-welfare facilities. Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment, 11, 991-998. http://doi.org/10.2147/NDT.S76105.

- Kim, J. Y., & Lee, K. Y. (2010). A study on the influence of school violence on the adolescent's suicidal ideation. Korean Journal of Youth Studies, 17(5), 121-149.

- Jung, H., & Lee, H. (2017). Problems and improvement plans of preventive education on school violence in the act on prevention and countermeasures for school violence. Journal of Social Welfare Management, 4(2), 179-192.

- Lee, S., Smith, P. K., & Monks, C. P. (2011). Perceptions of bullying-like phenomena in South Korea. A qualitative approach from a lifespan perspective. Journal of Aggression, Conflict and Peace Research, 3, 210–221. [CrossRef]

- Lereya, S. T., Samara, M., & Wolke, D. (2013). Parenting behavior and the risk of becoming a victim and a bully/victim: A meta-analysis study. Child Abuse & Neglect, 37(12), 1091–1108. [CrossRef]

- McAuley, C. (1996). Children in long-term foster care : emotional and social development. Avebury.

- McGinnis, H. A. (2021). Expanding the concept of birthparent loss to orphans: Exploratory findings from adolescents in institutional care in South Korea. New Ideas in Psychology, 63, 100892-. [CrossRef]

- McGuire, A., & Jackson, Y. (2018). Dimensions of maltreatment and academic outcomes for youth in foster care. Child Abuse & Neglect, 84, 82–94. [CrossRef]

- Murphy, T. P., Laible, D., & Augustine, M. (2017). The influences of parent and peer attachment on bullying. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 26(5), 1388–1397. [CrossRef]

- Nakamoto, & Schwartz, D. (2010). Is peer victimization associated with academic achievement? A meta-analytic review. Social Development (Oxford, England), 19(2), 221–242. [CrossRef]

- Nam Y., & Lee, S., (2008). A Comparison of Social Support and School Adjustment between Home-reared and Institutionalized Adolescents. Journal of Future Oriented Youth Society, 5(1), 1-18.

- Nunnally, J. C., & Bernstein, I. H. (1994). Psychometric the ory (3rd ed.). New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

- O'Brennan, L. M., & Furlong, M. J. (2010). Relations between students' perceptions of school connectedness and peer victimization. Journal of School Violence, 9(4), 375-391. [CrossRef]

- O’Hara, K. L., Rhodes, C. A., Wolchik, S. A., Sandler, I. N., & Yun-Tein, J. (2021). Longitudinal effects of postdivorce interparental conflict on children’s mental health problems through fear of abandonment: Does parenting quality play a buffering role? Child Development, 92(4), 1476–1493. [CrossRef]

- Olweus, D. (1993). Victimization by peers: Antecedents and long-term outcomes. In K. H. Rubin, & J. B. Asendorpf (Eds.), Social withdrawal, inhibition, and shyness in childhood (pp. 315–341). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.

- Parlar, H., Polatcan, M., & Cansoy, R. (2020). The relationship between social capital and innovativeness climate in schools. International Journal of Educational Management, 34(2), 232–244. [CrossRef]

- Park, J., Grogan-Kaylor, A., & Han, Y. (2021). Trajectories of childhood maltreatment and bullying of adolescents in South Korea. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 30, 1059-1070. [CrossRef]

- Park, S., Lee, Y., Jang, H., & Jo, M. (2017). Violence victimization in Korean adolescents: Risk factors and psychological Problems. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 14(5), 541-. [CrossRef]

- Park, M. K., & Moon, H. J. (2009). Emotional intelligence, social competence and school life satisfaction among institutionalized and home reared children. Journal of the Korean Home Economics Association, 47(2), 1-13.

- Reisen, A., Costa Leite, F. M., & Santos Neto, E. T. dos. (2021). Associação entre capital social e bullying em adolescentes de 15 a 19 anos: Relações entre o ambiente escolar e social/Association between social capital and bullying among adolescents aged between 15 and 19: relations between the school and social environment. Ciência & saude coletiva, 26(S3), 4919-. [CrossRef]

- Ryan, J. P., Jacob, B. A., Gross, M., Perron, B. E., Moore, A., & Ferguson, S. (2018). Early exposure to child maltreatment and academic outcomes. Child Maltreatment, 23(4), 365–375. [CrossRef]

- Seo, H.-J., Jung, Y.-E., Kim, M.-D., & Bahk, W.-M. (2017). Factors associated with bullying victimization among Korean adolescents. Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment, 13, 2429–2435. [CrossRef]

- Shin, H.S. (2005). The effect of individual, family, and peer and school variables on the middle school students` peer violence type. Korean Journal of Youth Studies, 12(4), 123-149.

- Sobba, K. N. (2018). Correlates and buffers of school avoidance: A review of school avoidance literature and applying social capital as a potential safeguard. International Journal of Adolescence and Youth, 24(3), 380–394. [CrossRef]

- Son, K. S., & Byeon, S. H. (2007). The Effects of group home adolescents' emotion on school adjustment. Korean Journal of Clinical Social Work, 4(2), 119-252.

- Sunwoo, H. J. & Lee, H. S. (2014). A study on the effect of bullying to school adjustment: moderating effect of teacher-student relationships. Korean Journal of Youth Studies, 21(1), 149-166.

- The Korean Institute of Social and Health Affairs. (2013). The Korean Institute of Social and Health Affairs. User’s guide the 7th wave of the Korean Welfare Panel Study. Seoul, South Korea.

- Thurman, W., Johnson, K., Gonzalez, D. P., & Sales, A. (2018). Teacher support as a protective factor against sadness and hopelessness for adolescents experiencing parental incarceration: Findings from the 2015 Texas Alternative School Survey. Children and Youth Services Review, 88, 558–566. [CrossRef]

- Van IJzendoorn, M. H., Schuengel, C., & Bakermans-Kranenburg, M. J. (1999). Disorganized attachment in early childhood: Meta-analysis of precursors, concomitants, and sequelae. Development and Psychopathology, 11, 225-249.

- Vecchio, G. M., Zava, F., Cattelino, E., Zuffiano, A., & Pallini, S. (2023). Children's prosocial and aggressive behaviors: The role of emotion regulation and sympathy. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 89, 101598-. [CrossRef]

- Veenstra, R., Lindenberg, S., Oldehinkel, A. J., De Winter, A. F., Verhulst, F. C., & Ormel, J. (2005). Bullying and victimization in elementary schools: A comparison of bullies, victims, bully/victims, and uninvolved preadolescents. Developmental psychology, 41(4), 672. [CrossRef]

- Walden, L. M., & Beran, T. N. (2010). Attachment quality and bullying behavior in school-aged youth. Canadian Journal of School Psychology, 25(1), 5-18. [CrossRef]

- Yang, E. B., Kim, T. W., Park, E. H., Lee, S. Y., & Chung, I. J. (2015). Predictors of school adjustment: A focus on the comparison between general adolescents and adolescents in out-of-home care, The Korean society of school social work, 31, 311-331. [CrossRef]

- Yoon, D., Shipe, S. L., Park, J., & Yoon, M. (2021). Bullying patterns and their associations with child maltreatment and adolescent psychosocial problems. Children and Youth Services Review, 129, 106178-. [CrossRef]

- You, S., Kim, E., & Kim, M. (2014). An Ecological Approach to Bullying in Korean Adolescents. Journal of Pacific Rim Psychology, 8(1), 1–10. [CrossRef]

- Yu, A. J., Min, H. Y., & Kwon, K. N. (2001). Ego-identity and psyco-social adjustments of institutionalized children and adolescents. Korean Journal of Family Medicine. 39(3), 135-149.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).