1. Introduction

Early adolescence is a pivotal developmental stage marked by rapid physical, cognitive, and socio-emotional changes that significantly influence an individual's future well-being and social functioning (Torgerson et al., 2024). During this period, adolescents undergo substantial brain development, which enhances their cognitive abilities and emotional regulation. Adolescents are progressively capable of engaging with complex ideological issues, articulating their viewpoints, and questioning authority. Additionally, they exhibit an improved capacity to envision their future, anticipate their needs, and set personal goals (Harrison & Bishop, 2021). However, despite these developmental advancements, early adolescence is also a time when bullying becomes a prevalent issue, leading to long-term mental health challenges such as depression and anxiety (Winding et al., 2020).

Bullying is defined as repetitive aggressive behavior that involves an imbalance of power between the perpetrator and the victim. This behavior can be physical, verbal, or psychological, and it is intended to cause harm or distress to the victim (Smith, 2016). In defining bullying, a consensus has recently emerged highlighting three key characteristics: 1) Aggressive actions are deliberate, 2) They tend to be recurrent, and 3) They typically happen in contexts of power imbalance (Olweus, 2013). In Iran, the prevalence of bullying manifests in various forms across different age groups and settings. Among school-aged children and adolescents, traditional bullying rates range from 5% to 45%, with verbal victimization being the most common at 24.7%, followed by relational victimization at 15%, and physical victimization at 10.3% (Kabiri et al., 2024). Recent research identifies several key factors for bullying among teenagers, including poor teacher-student relationships, negative peer relationships, low family cohesion, high levels of negative affect, anxiety, and authoritarian parenting styles (Qiu et al., 2024; Samadieh & Khamesan, 2025). One of the most important determinants of bullying is family functioning (Grama et al., 2024).

Family functioning refers to how family members interact and work together to achieve goals and meet the needs of each member. According to systems theory, family functioning encompasses several components: adaptability (the family's ability to change and adjust), cohesion (the emotional bonding between family members), communication (the exchange of information), and roles (the distribution of responsibilities within the family) (Olson, 2000). Research indicates that family functioning significantly influences adolescent bullying and victimization. For instance, families with high levels of conflict, poor communication, and low cohesion are more likely to have children who engage in bullying (Grama et al., 2024) or experience other mental health issues (Goshayeshi et al., 2024). Conversely, supportive family environments with open communication and emotional warmth can act as protective factors against bullying (Fan & Meng, 2022; Grama et al., 2024; Kim et al., 2022). Similarly, studies have shown that people's perception of parents' parenting style is also related to various components of mental health, including social adjustment (Samadieh & Nasri, 2021) and basic psychological needs (Tanhaye Rseshvanloo et al., 2019). Although numerous studies have explored the impact of family functioning in different contexts, the mechanisms linking family functioning to bullying experiences in early adolescence remain unclear. One mediating factor in this relationship appears to be emotion regulation difficulties (Sylvia Chu Lin et al., 2024).

Emotion regulation difficulties refer to the challenges individuals face in managing and adaptively responding to their emotional experiences. According to Gratz and Roemer (2004), these difficulties encompass several components: non-acceptance of emotional responses, limited access to emotion regulation strategies, difficulty controlling impulsive behaviors, difficulty engaging in goal-directed behaviors, and lack of emotional clarity. Non-acceptance of emotional responses involves negative reactions to one's own emotions, while limited access to strategies refers to the inability to employ effective methods to modulate emotions. Difficulty controlling impulsive behaviors denotes struggles in inhibiting inappropriate actions when experiencing strong emotions. Difficulty engaging in goal-directed behaviors highlights the challenge of maintaining focus on tasks despite emotional distress. Lastly, lack of emotional clarity involves confusion about one's emotional states (Gratz & Roemer, 2004). According to Gross's (1998) process model of emotion regulation, these difficulties can mediate the relationship between family functioning and bullying experiences in early adolescence. Poor family functioning, characterized by conflict, lack of support, and ineffective communication, can impair the development of healthy emotion regulation skills in children. As a result, adolescents with emotion regulation difficulties may struggle to manage their emotions effectively, leading to increased vulnerability to both perpetrating and experiencing bullying. For instance, an adolescent who cannot control impulsive behaviors may react aggressively in social situations, while another who lacks emotional clarity may misinterpret social cues, both of which can contribute to bullying dynamics (Gross, 1998).

Recent research has highlighted the significant relationship between family functioning and difficulties in emotion regulation. For instance, Boyes et al. (2023) found that poor family functioning was positively associated with difficulties in emotion regulation among university students, which in turn mediated the relationship between family functioning and non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI) (Boyes et al., 2023). Another study by Paley and Hajal (2022) emphasized that family-level processes, including coregulation within family subsystems, play a crucial role in the development of children's emotion regulation skills. They noted that impaired family functioning can disrupt these processes, leading to emotion regulation difficulties (Paley & Hajal, 2022). Additionally, research by Miu et al. (2022) demonstrated that adverse family environments are strong predictors of emotion regulation difficulties, which can lead to various psychopathologies (Miu et al., 2022).

Despite extensive research on the impact of family functioning on adolescent behavior, there remain significant gaps in understanding the specific mechanisms through which family dynamics influence bullying experiences. Previous studies have often focused on direct correlations without exploring the mediating role of emotion regulation difficulties (Arató et al., 2022; Sylvia Chu Lin et al., 2024). By integrating insights from Gratz and Roemer's (2004) model of emotion regulation and Gross's (1998) process model, this study offers a novel perspective on the interplay between family dynamics and adolescent bullying. The purpose of this research is to elucidate the pathways through which family functioning impacts bullying behaviors, thereby informing more effective interventions aimed at improving family environments and reducing bullying incidents.

2. Methods and Materials

2.1. Study Design and Participants

This research is applied in its objective, employs a descriptive-correlational approach, and utilizes fieldwork for data gathering. The research population comprised all secondary school students (First period) in Birjand during the 2023-2024 academic year. A total of 350 students participated in the study through multi-stage cluster sampling. According to Kline (2023), the minimum sample size for structural equation modeling is 200. Bentler and Chou (1987) suggest an adequate sample size of at least 5 per parameter estimation. In this study, with 45 estimated parameters, a sample size of 225 was sufficient. However, to account for potential attrition and to enhance the validity and generalizability of the results, a sample size of 350 was chosen.

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. The Illinois Bullying Scale

The Illinois Bullying Scale (IBS), developed by Espelage and Holt (2001) is an instrument to assess bullying and victimization behaviors among children and adolescents. The Persian version of IBS (Chalmeh, 2013), was used to measure bullying experiences. It consists of 18 items designed to assess three dimensions of bullying: bully (9 items), fight (5 items), and victim (4 items). Respondents rate the frequency of these behaviors over the past month using a five-point Likert scale ranging from "never" to “seven times or more.” Higher scores on the scale indicate a greater frequency of bullying behavior. The original version of the IBS demonstrated good reliability and validity, with Cronbach's alpha coefficients typically above 0.80, indicating high internal consistency (Espelage & Holt, 2001). The scale has been widely used in Iran to examine the prevalence and correlates of bullying behavior (Samadieh et al., 2024). Chalmeh (2013) demonstrated that this scale possesses strong validity and reliability within Iranian society.

2.2.2. The Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale

The Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale-Short Form (DERS-16) was developed by Bjureberg et al. (2016) to provide a concise measure of emotion regulation difficulties. This scale is a shortened version of the original DERS, which was created by Gratz and Roemer in 2004. The DERS-16 consists of 16 items designed to assess five domains of emotion dysregulation: nonacceptance of emotional responses, difficulties engaging in goal-directed behavior, impulse control difficulties, limited access to effective emotion regulation strategies, and lack of emotional clarity. Each item is rated on a five-point Likert scale ranging from "almost never" (1) to "almost always" (5). Higher scores on the DERS-16 indicate greater difficulties in emotion regulation. The original version of the DERS-16 demonstrated excellent internal consistency, with Cronbach's alpha coefficients typically above 0.90, and good test-retest reliability. The scale also showed strong convergent and discriminant validity (Bjureberg et al., 2016). In Iran, the DERS-16 was validated by researchers who adapted the tool to the cultural context, ensuring its reliability and validity for use with Iranian populations. The validation process in Iran involved assessing the scale's internal consistency, test-retest reliability, and construct validity, with Cronbach's alpha coefficients indicating satisfactory reliability (Fallahi, 2021).

2.2.3. The Family Assessment Device

The Family Assessment Device (FAD) was developed by Epstein et al. (1983) to measure the structural, organizational, and transactional characteristics of families based on the McMaster Model of Family Functioning. The FAD consists of 60 items divided into seven subscales: problem solving, communication, roles, affective responsiveness, affective involvement, behavior control, and general family functioning. For the purpose of this research, only the general family functioning subscale was utilized. This subscale includes 12 items and is scored on a four-point Likert scale ranging from "strongly agree" to "strongly disagree." Higher scores on this scale indicate poorer family functioning. The original version of the FAD demonstrated good reliability and validity, with Cronbach's alpha coefficients for the subscales typically above 0.70, and the general family functioning subscale showing an alpha of 0.92, indicating high internal consistency (Epstein et al., 1983). In Iran, the FAD was validated by researchers who adapted the tool to the cultural context, ensuring its reliability and validity for use with Iranian populations. The validation process in Iran involved assessing the scale's internal consistency, test-retest reliability, and construct validity, with satisfactory results (Yousefi, 2012).

2.3. Data Analysis

Data analysis was conducted using both SPSS 26 and AMOS 22. Initially, descriptive statistics, including means, standard deviations, and frequencies, were calculated using SPSS to provide an overview of the sample characteristics and the distribution of key variables. Pearson correlation coefficients were then computed to examine the relationships between variables. To test the hypothesized mediation model, structural equation modeling (SEM) was performed using AMOS. This involved assessing the direct and indirect effects of family functioning on bullying experiences through emotion regulation difficulties. Model fit indices, such as the Chi-square test, Comparative Fit Index (CFI), and Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA), were used to evaluate the adequacy of the model. Bootstrapping procedures were employed to test the significance of the mediation effects.

3. Findings and Results

In this research, a sample of 350 secondary students from Birjand was selected using multi-stage cluster sampling. The gender distribution was nearly equal, with 49.1% female and 50.9% male participants. The age distribution indicated that 44% of the students were aged between 13 and 14 years, 46.6% were between 14.01 and 15 years, and 9.4% were older than 15 years. Additionally, 35.1% of the participants were in the seventh grade, 34.6% in the eighth grade, and 30.3% in the ninth grade.

Initially, the data were screened, and any missing values were imputed using the mean. Univariate outliers were then identified using a box plot, and the results indicated the absence of any univariate outliers. Multivariate outliers were assessed using Mahalanobis distances, with intervals adjusted according to the degrees of freedom (predictor variables in the model) and evaluated using the chi-square (χ²) test at the P<0.001 significance level (Meyers et al., 2016). The analysis revealed no multivariate outliers.

Table 1 presents the mean, standard deviation, minimum, maximum, skewness, and kurtosis of the research variables.

Table 1 presents the mean and standard deviation of family functioning, which are 38.06 and 5.88, respectively. Regarding emotional regulation difficulties, the highest average is observed in limited access to strategies (12.77), while the lowest average is noted in lack of emotional clarity (5.12). Regarding the bullying subscales, the bullying dimension exhibits the highest average (6.93), whereas the victim dimension shows the lowest average (3.55).

Several assumptions were evaluated before performing structural equation modeling.

Table 1 indicates that, based on skewness (±2) and kurtosis (±7) criteria (Schumacker & Lomax, 2016), all variables exhibit acceptable levels of skewness and kurtosis, confirming univariate normality. For multivariate normality, standardized residuals were calculated and assessed using the one-sample Kolmogorov-Smirnov test, which confirmed the normal distribution of residuals (P<0.05, df=350, Z=0.04). Multicollinearity was examined using tolerance and variance inflation factor (VIF) indices. Tolerance values between 0.43 and 0.82 and VIF values between 1.22 and 2.33 indicate no multicollinearity (Pituch & Stevens, 2015). The Durbin-Watson statistic was employed to test for independence of errors, with a value of 1.88 falling within the acceptable range of 1.5 to 2.5 (Neter et al., 1996). Lastly, the assumption of homogeneity of variances was verified by examining the residuals' variance against predicted values, revealing no discernible pattern, thus confirming homogeneity. In the following,

Table 2 presents the correlation coefficients of the variables under investigation.

Table 2 illustrates a significant negative correlation between family functioning and both emotion regulation difficulties and the dimensions and overall score of bullying (P≤0.01). Furthermore, a significant positive correlation is observed between emotion regulation difficulties and the dimensions and total score of bullying experiences (P≤0.05).

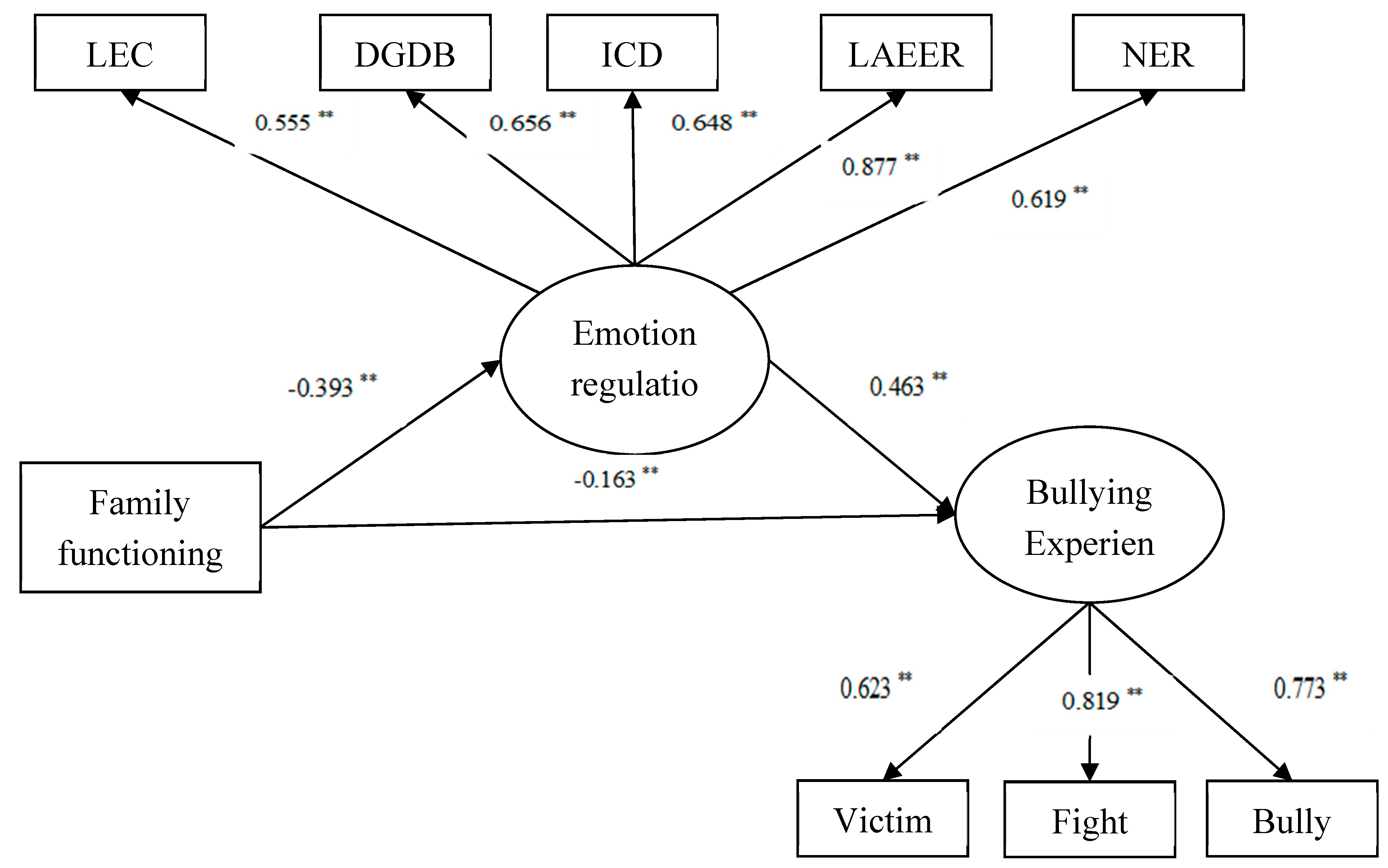

The structural model fit was assessed using several key indicators, each compared against established thresholds. The ratio of chi-square to degrees of freedom (χ²/df) was 2.428, which is below the recommended threshold of 3.0 (Kline, 2023). The Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) was 0.064, within the acceptable range of 0.05 to 0.08 (Bollen & Long, 1993). The Incremental Fit Index (IFI) was 0.948, exceeding the acceptable threshold of 0.90 (Hu & Bentler, 1999). The Comparative Fit Index (CFI) was 0.964, also above the 0.90 threshold (Hu & Bentler, 1999). Lastly, the Goodness of Fit Index (GFI) was 0.964, surpassing the recommended minimum of 0.90 (Stevens, 2002). Subsequently, the model was estimated using the maximum likelihood approach, and the standardized coefficients along the paths were computed. The standardized path coefficients are presented in

Figure 1.

As indicated in

Table 3, family functioning exhibits a negative and significant direct effect on emotion regulation difficulties (P≤0.001, β = -0.393). This finding suggests that better family functioning serves as a predictor of reduced emotion regulation difficulties. Similarly, the direct effect of family functioning on bullying is negative and significant (P≤0.008, β = -0.163), implying that improved family functioning corresponds to decreased bullying experiences. Furthermore,

Table 3 reveals a positive and significant direct effect of emotion regulation difficulties on bullying experiences (P≤0.001, β = 0.463). This indicates that higher levels of emotion regulation difficulties predict increased bullying experiences. Notably, our findings demonstrate an indirect effect: family functioning influences bullying experiences through difficulties in regulating emotions (P≤0.001, β = -0.182). Thus, enhancing family functioning may mitigate emotion regulation difficulties, leading to a reduction in bullying experiences.

4. Discussion and Conclusion

The present study aimed to explore the mediating role of emotion regulation difficulties in the association between family functioning and bullying experiences among high school students. Our findings revealed significant path coefficients, both direct and indirect, underscoring the importance of emotion regulation processes in understanding the dynamics of bullying. Specifically, students who reported greater difficulties in regulating their emotions were more likely to experience bullying. These results contribute to our understanding of the complex interplay between family context, emotion regulation, and peer victimization in the school environment.

The study found that better family functioning has a negative and significant impact on bullying experiences among teenagers. In other words, when family relationships are more supportive, teens are less likely to be engaged in bullying or being victimized. This finding is directly or indirectly aligned with other similar studies (Asghari Sharabiani & Basharpoor, 2021; Mazzone & Camodeca, 2019; Zhang et al., 2022). The theory-based explanation for these findings lies in the social learning theory and attachment theory. According to social learning theory, children learn behaviors by observing and imitating their family members. Positive family functioning fosters prosocial behaviors, empathy, and conflict resolution skills, reducing the likelihood of aggressive or bullying behavior. Conversely, dysfunctional family dynamics may lead to maladaptive coping strategies, including aggression or victimization. Attachment theory emphasizes the significance of secure attachments within the family. When children experience consistent emotional support and secure attachment bonds, they develop resilience and self-regulation. In contrast, insecure attachments or family dysfunction may contribute to emotional distress, making adolescents vulnerable to bullying experiences (Merrin et al., 2023).

The present study also revealed a statistically significant direct impact of family functioning on emotion regulation difficulties. This result aligns with findings from numerous prior studies (Boyes et al., 2023; Ma et al., 2024; Sustrami et al., 2024). These studies underscore the crucial role of family dynamics in shaping students’ ability to regulate their emotions effectively. Boyes, Mah, and Hasking (2023) found that poor family functioning was positively associated with non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI). Difficulties in emotion regulation mediated this relationship, emphasizing the role of family context in emotional well-being. The McMaster Model of Family Functioning (MMFF) provides a comprehensive framework for understanding family dynamics and their influence on individual well-being. According to this model, families that excel in problem-solving skills tend to foster better emotion regulation abilities in adolescents. Effective problem-solving strategies within the family context equip adolescents with adaptive coping mechanisms to manage emotional challenges. Open and constructive communication within the family is also crucial. When families encourage dialogue about emotions, adolescents learn to express their feelings, seek support, and regulate their emotional responses effectively. Moreover, clearly defined roles and responsibilities within the family structure impact how adolescents regulate their emotions. When roles are flexible and supportive, adolescents experience less emotional strain. Family rules, boundaries, and discipline practices shape adolescents’ emotional regulation patterns. Consistent and fair behavior control helps adolescents learn self-regulation (Epstein et al., 2003). In summary, McMaster’s theory emphasizes that family functioning directly impacts emotion regulation in adolescents. By fostering a supportive, communicative, and well-structured.

The study found that teenagers who struggle with emotion regulation are more likely to engage in bullying behaviors and be bullied by their peers. This aligns with similar research findings (Bäker et al., 2023; Eilts et al., 2023; Wang et al., 2024). In a systematic review of empirical studies, Herd and Kim-Spoon (2021) observed a significant negative association between adverse peer experiences and emotion regulation. Specifically, more emotion dysregulation and less use of adaptive emotion regulation strategies were linked to bullying victimization. This emphasizes the role of effective emotion regulation in preventing victimization. Emotion regulation difficulties can impact how individuals perceive and respond to social interactions. When adolescents struggle with regulating their emotions, they may be more prone to aggressive behaviors (such as bullying perpetration) or vulnerability (as victims). Dysfunctional emotion regulation strategies, such as impulsivity or emotional suppression, may hinder effective coping and problem-solving. Conversely, adaptive emotion regulation strategies, like cognitive reappraisal or perspective-taking, can enhance social interactions and reduce conflict. Therefore, interventions aimed at improving emotion regulation skills could play a crucial role in preventing bullying experiences among teenagers (Wang et al., 2024).

The main finding was that emotion regulation difficulties mediate the relationship between family functioning and bullying experiences, which is consistent with several studies (Asghari Sharabiani & Basharpoor, 2021; Qiao et al., 2024). For instance, Sharabiani and Basharpoor (2021) found that family functioning significantly impacts bullying, with empathy acting as mediator. Similarly, Lin et al. (2024) highlighted the role of family and parenting factors in adolescent emotion regulation, emphasizing the neural correlates of emotional reactivity and regulation. Theoretically, this finding aligns with the tripartite model of emotion regulation, which posits that parental role modeling, emotion socialization behaviors, and the family’s emotional climate are crucial for the development of emotion regulation in adolescents. These studies collectively underscore the importance of family dynamics in shaping emotion regulation abilities, which in turn influence bullying behaviors and victimization.

5. Limitations and Suggestions

One limitation of this study is its cross-sectional design, which restricts the ability to infer causality between family functioning, emotion regulation difficulties, and bullying experiences. Longitudinal studies are needed to establish temporal relationships and causative links. Additionally, the reliance on self-reported data may introduce bias, as participants might underreport or overreport their experiences due to social desirability or recall issues. The sample's demographic homogeneity, primarily consisting of early adolescents from a specific region, limits the generalizability of the findings to more diverse populations. Furthermore, the study did not account for potential confounding variables such as socioeconomic status, peer relationships, and school environment, which could influence the observed relationships.

Future research should employ longitudinal designs to better understand the causal pathways between family functioning, emotion regulation difficulties, and bullying experiences. Expanding the sample to include diverse populations across different regions and cultural backgrounds would enhance the generalizability of the findings. Incorporating multi-informant approaches, such as reports from parents, teachers, and peers, could provide a more comprehensive understanding of the dynamics at play. Additionally, examining the role of potential confounding variables, such as socioeconomic status, peer relationships, and school environment, would offer a more nuanced view of the factors influencing bullying behaviors. Finally, intervention studies aimed at improving family functioning and emotion regulation skills could provide valuable insights into effective strategies for reducing bullying in early adolescence (Samadieh & Khamesan, 2024).

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to extend their deepest gratitude to all the participants who contributed their time and insights to this study.

Declaration of Interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Ethics Consideration

The study protocol adhered to the principles outlined in the Helsinki Declaration, which provides guidelines for ethical research involving human participants.

Transparency of Data

In accordance with the principles of transparency and open research, we declare that all data and materials used in this study are available upon request.

Author Contributions

The original manuscript was authored and revised by the first author. The second author drafted the article and conducted data collection.

Funding

This research was carried out independently with personal funding and without the financial support of any governmental or private institution or organization.

References

- Arató, N., Zsidó, A., Rivnyák, A., Peley, B., & Labadi, B. (2022). Risk and protective factors in cyberbullying: the role of family, social support and emotion regulation. International Journal of Bullying Prevention, 4(2), 160-173. [CrossRef]

- Asghari Sharabiani, A., & Basharpoor, S. (2021). The mediating role of empathy in the relationship between family functioning and bullying in students. Journal of Family Psychology, 5(2), 15-26. [CrossRef]

- Bäker, N., Wilke, J., Eilts, J., & von Düring, U. (2023). Understanding the Complexities of Adolescent Bullying: The Interplay between Peer Relationships, Emotion Regulation, and Victimization. New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development, 2023(1), 9916294. [CrossRef]

- Bentler, P. M., & Chou, C.-P. (1987). Practical issues in structural modeling. Sociological methods & research, 16(1), 78-117. [CrossRef]

- Bjureberg, J., Ljótsson, B., Tull, M. T., Hedman, E., Sahlin, H., Lundh, L.-G., Bjärehed, J., DiLillo, D., Messman-Moore, T., & Gumpert, C. H. (2016). Development and validation of a brief version of the difficulties in emotion regulation scale: the DERS-16. Journal of psychopathology and behavioral assessment, 38, 284-296. [CrossRef]

- Bollen, K. A., & Long, J. S. (1993). Testing structural equation models (Vol. 154). Sage.

- Boyes, M. E., Mah, M. A., & Hasking, P. (2023). Associations between family functioning, emotion regulation, social support, and self-injury among emerging adult university students. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 32(3), 846-857. [CrossRef]

- Chalmeh, R. (2013). Psychometrics Properties of the Illinois bullying scale (IBS) in Iranian students: validity, reliability and factor structure. https://jpmm.marvdasht.iau.ir/article_238.html .

- Eilts, J., Wilke, J., Düring, U. v., & Bäker, N. (2023). Bullying perpetration: the role of attachment, emotion regulation and empathy. Emotional and Behavioural Difficulties, 28(4), 219-233. [CrossRef]

- Epstein, N. B., Baldwin, L. M., & Bishop, D. S. (1983). The McMaster family assessment device. Journal of marital and family therapy, 9(2), 171-180. [CrossRef]

- Epstein, N. B., Ryan, C. E., Bishop, D. S., Miller, I. W., & Keitner, G. I. (2003). The McMaster model: A view of healthy family functioning. The Guilford Press.

- Espelage, D. L., & Holt, M. K. (2001). Bullying and victimization during early adolescence: Peer influences and psychosocial correlates. In Bullying behavior (pp. 123-142). Routledge.

- Fallahi, V., Narimani, M., Atadokht, A. (2021). Psychometric Properties of the Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale Brief Form (DERS-16): in a Group of Iranian Adolescents. Journal of Shahid Sadoughi University of Medical Sciences, 29(5), 62-82.

- Fan, L. L., & Meng, W. J. (2022). The relationship between parental support and exposure to being bullied: Family belonging as a mediator. Social Behavior and Personality: an international journal, 50(12), 1-8. [CrossRef]

- Goshayeshi, M., Samadieh, H., & Reshvanloo, F. T. (2024). Risk and Protective Factors of Oppositional Defiant Disorder in Children with Stuttering: Unraveling Familial Dynamics. Sciences, 5(2), 31-37. [CrossRef]

- Grama, D. I., Georgescu, R. D., Coşa, I. M., & Dobrean, A. (2024). Parental risk and protective factors associated with bullying victimization in children and adolescents: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clinical child and family psychology review, 1-31. [CrossRef]

- Gratz, K. L., & Roemer, L. (2004). Multidimensional assessment of emotion regulation and dysregulation: Development, factor structure, and initial validation of the difficulties in emotion regulation scale. Journal of psychopathology and behavioral assessment, 26, 41-54. [CrossRef]

- Gross, J. J. (1998). The emerging field of emotion regulation: An integrative review. Review of general psychology, 2(3), 271-299. [CrossRef]

- Harrison, L. M., & Bishop, P. A. (2021). The Evolving Middle School Concept: This We (Still) Believe. Current Issues in Middle Level Education, 25(2), 2-5. [CrossRef]

- Herd, T., & Kim-Spoon, J. (2021). A systematic review of associations between adverse peer experiences and emotion regulation in adolescence. Clinical child and family psychology review, 24(1), 141-163. [CrossRef]

- Hu, L. t., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural equation modeling: a multidisciplinary journal, 6(1), 1-55. [CrossRef]

- Kabiri, S., Donner, C. M., Shadmanfaat, S. M., & Rahmati, M. M. (2024). School bullying among Iranian Adolescents: Considering a higher moderation model in situational action theory. International Journal of Bullying Prevention, 6(2), 149-162. [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y., Richards, J. S., & Oldehinkel, A. J. (2022). Self-control, mental health problems, and family functioning in adolescence and young adulthood: Between-person differences and within-person effects. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 51(6), 1181-1195. [CrossRef]

- Kline, R. B. (2023). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. Guilford publications.

- Lin, S. C., Kehoe, C., Pozzi, E., Liontos, D., & Whittle, S. (2024). Research review: Child emotion regulation mediates the association between family factors and internalizing symptoms in children and adolescents–A meta-analysis. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 65(3), 260-274. [CrossRef]

- Lin, S. C., Pozzi, E., Kehoe, C. E., Havighurst, S., Schwartz, O. S., Yap, M. B., Zhao, J., Telzer, E. H., & Whittle, S. (2024). Family and parenting factors are associated with emotion regulation neural function in early adolescent girls with elevated internalizing symptoms. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 1-11. [CrossRef]

- Ma, R., Zhang, Q., Zhang, C., & Xu, W. (2024). Longitudinal associations between family functioning and generalized anxiety among adolescents: the mediating role of self-identity and cognitive flexibility. BMC psychology, 12(1), 1-10. [CrossRef]

- Mazzone, A., & Camodeca, M. (2019). Bullying and moral disengagement in early adolescence: Do personality and family functioning matter? Journal of Child and Family Studies, 28, 2120-2130. [CrossRef]

- Merrin, G. J., Wang, J. H., Kiefer, S. M., Jackson, J. L., Pascarella, L. A., Huckaby, P. L., Blake, C. L., Gomez, M. D., & Smith, N. D. (2023). Adverse childhood experiences and bullying during adolescence: A systematic literature review of two decades. Adolescent Research Review, 1-29. [CrossRef]

- Meyers, L. S., Gamst, G., & Guarino, A. J. (2016). Applied multivariate research: Design and interpretation. Sage publications.

- Miu, A. C., Szentágotai-Tătar, A., Balazsi, R., Nechita, D., Bunea, I., & Pollak, S. D. (2022). Emotion regulation as mediator between childhood adversity and psychopathology: A meta-analysis. Clinical psychology review, 93, 102141. [CrossRef]

- Neter, J., Kutner, M. H., Nachtsheim, C. J., & Wasserman, W. (1996). Applied linear statistical models.

- Olson, D. H. (2000). Circumplex model of marital and family systems. Journal of family therapy, 22(2), 144-167. [CrossRef]

- Olweus, D. (2013). School bullying: Development and some important challenges. Annual review of clinical psychology, 9(1), 751-780. [CrossRef]

- Paley, B., & Hajal, N. J. (2022). Conceptualizing emotion regulation and coregulation as family-level phenomena. Clinical child and family psychology review, 25(1), 19-43. [CrossRef]

- Pituch, K. A., & Stevens, J. P. (2015). Applied multivariate statistics for the social sciences: Analyses with SAS and IBM’s SPSS. Routledge.

- Qiao, T., Sun, Y., Ye, P., Yan, J., Wang, X., & Song, Z. (2024). The association between family functioning and problem behaviors among Chinese preschool left-behind children: the chain mediating effect of emotion regulation and psychological resilience. Frontiers in Psychology, 15, 1343908. [CrossRef]

- Qiu, T., Wang, S., Hu, D., Feng, N., & Cui, L. (2024). Predicting risk of bullying victimization among primary and secondary school students: based on a machine learning model. Behavioral Sciences, 14(1), 73. [CrossRef]

- Samadieh, H., & Khamesan, A. (2024). Bullying Interventions: A Systematic Review of Iranian Research. [CrossRef]

- Samadieh, H., & Khamesan, A. (2025). A Serial Mediation Model of Perceived Social Class and Cyberbullying: The Role of Subjective Vitality in Friendship Relations and Psychological Distress. Iranian Journal of Psychiatry, 20(1), 27-36. [CrossRef]

- Samadieh, H., Khamesan, A., & Mohammadzadeh, M. (2024). Bullying scales in educational contexts: A systematic review of two decades of research in Iran. Rooyesh-e-Ravanshenasi Journal (RRJ), 13(2), 47-58. http://frooyesh.ir/article-1-5016-en.html .

- Samadieh, H., & Nasri, M. (2021). The explanation of students’ adjustment to university based on perceptions of parents: mediating mechanism of cognitive flexibility. Rooyesh-e-Ravanshenasi Journal (RRJ), 10(7), 35-46. http://frooyesh.ir/article-1-2701-en.html .

- Schumacker, E., & Lomax, G. (2016). A Beginner’s Guide to Structural Equation Modelling. 4th edtn. In: London: Routledge New York, NY.

- Smith, P. K. (2016). Bullying: Definition, types, causes, consequences and intervention. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 10(9), 519-532. [CrossRef]

- Stevens, J. (2002). Applied multivariate statistics for the social sciences (Vol. 4). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Mahwah, NJ.

- Sustrami, D., Ajeng, A., Susanti, A., & Syadiah, H. (2024). The Relationship between Family Function and Coping Strategies among Adolescents who Experience of Catcalling Verbal Sexual Harassment. 2nd Lawang Sewu International Symposium on Health Sciences: Nursing (LSISHS-N 2023), .

- Tanhaye Rseshvanloo, F., Samadiye, H., Kareshki, H., Manouchehri, M., & Alizade, M. (2019). Structural Relationships between Perceptions of Parents, Basic Psychological Needs and Academic Burnout in Medical Students [Original research article]. Iranian Journal of Medical Education, 19(0), 542-553. http://ijme.mui.ac.ir/article-1-4885-en.html .

- Torgerson, C., Ahmadi, H., Choupan, J., Fan, C. C., Blosnich, J. R., & Herting, M. M. (2024). Sex, gender diversity, and brain structure in early adolescence. Human Brain Mapping, 45(5), e26671. [CrossRef]

- Wang, H., Zhang, M.-R., He, J., Saiding, A., Zong, C., Zhang, Y., & Chen, C. (2024). Exploring the Association Between Bullying Victimization and Poor Mental Health in Rural Chinese Adolescents: The Mediating Effects of Emotion Regulation. School Mental Health, 1-13. [CrossRef]

- Winding, T. N., Skouenborg, L. A., Mortensen, V. L., & Andersen, J. H. (2020). Is bullying in adolescence associated with the development of depressive symptoms in adulthood?: A longitudinal cohort study. BMC psychology, 8, 1-9. [CrossRef]

- Yousefi, N. (2012). An investigation of the psychometric properties of the mcmaster clinical rating scale (MCRS). Quarterly of Educational Measurement, 2(7), 91-120.

- Zhang, H., Han, T., Ma, S., Qu, G., Zhao, T., Ding, X., Sun, L., Qin, Q., Chen, M., & Sun, Y. (2022). Association of child maltreatment and bullying victimization among Chinese adolescents: The mediating role of family function, resilience, and anxiety. Journal of affective disorders, 299, 12-21. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).