1. Introduction

Pristine graphene is impermeable to gases; however, Ga ions bombardment can creates holes in the graphene and it can allow gas permeability [

1,

2]. Nanoporous graphene has great potential to be used in water desalination [

3,

4] and gas separation technology [

5,

6,

7,

8,

9]. Recently, nanoporous graphene is used for in vivo brain signal recording and stimulation[

10]. Furthermore, functional nanoporous graphene superlattices and other three-dimensional structures are synthesized for diverse applications [

11,

12].

Here, we investigate transport and quantum tunneling of H2 and H2O molecules through graphene nanopores. Atomic models of graphene with different pore sizes are created and molecular transport is studied using first principles density functional theory. Different orientations of H2 and H2O molecules and their effects during the transfer are investigated.

It is found that the quantum effect of tunneling can be realized if the total energy of the molecule is sufficiently high and is relatively close to the top of the potential energy barrier. It is also found that there are potential energy wells on front of the nanopore and behind the nanopore in which the molecules can be trapped. The molecular “trap-escape” mechanism is analyzed by calculating the quantized translational energy levels of the H2O and H2 molecules within the quantum wells.

2. Models and Methods

The electronic structures and the potential energy reaction barriers were calculated using ab initio density functional theory (DFT). Quickstep module [

13] in the CP2K software package was used. Periodic structures can be investigated using this module. The calculations were performed using the Perdew-Burke-Erznerhof (PBE) [

14] generalized gradient approximation (GGA) functional for the exchange-correlation term in the Kohn-Sham equations. The DZVP-MOLOPT-SR-GTH [

15] basis set and the Goedecker-Teter-Hutter (GTH) [

16] type pseudopotentials were used. The Van der Waals interactions were included using the semi-empirical “DFT+D3” term [

17]. The LBFGS [

18] optimizer was used for energy minimization to optimize the geometry. The tunneling probability calculations were performed using Wentzel-Kramers-Brillouin (WKB) approximation method [

19].

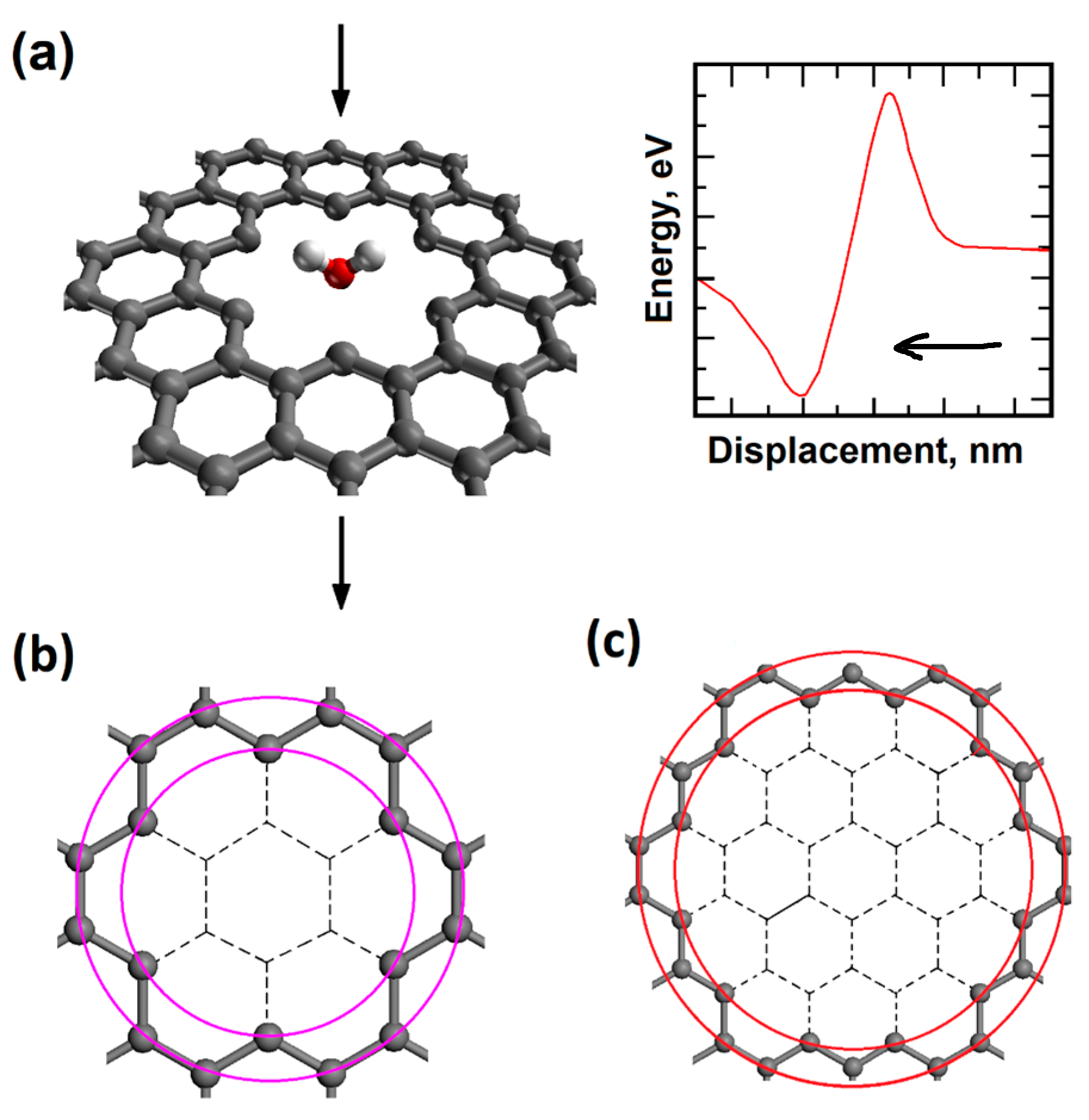

We created atomistic models for two different graphene nanopore sizes as shown in

Figure 1. The “regular nanopore” model structure has the inner and outer diameters of 0.57 nm and 0.75 nm and the “large nanopore” model structure has the inner and outer diameters of 1.02 nm and 1.2297 nm, respectively. The H

2 and water molecules were placed in the middle of each nanopore, and they were translated in the direction perpendicular to the graphene plane. Graphene model structures were hydrogen-terminated.

In the models, the graphene plane height was 0.0 nm. Initially, H

2 and H

2O molecules were 0.5 nm above the graphene plane and they were facing the center of the nanopore. The model structure containing water molecule with it’s oxygen atom pointing towards the nanopore is shown in

Figure 1. The molecule was translated towards the center of the nanopore in discrete steps and total energy values were calculated using density functional theory. The variation of total energy as a function of molecule height gives us potential energy barriers for molecular transport. Such total energy variation is also presented in

Figure 1.

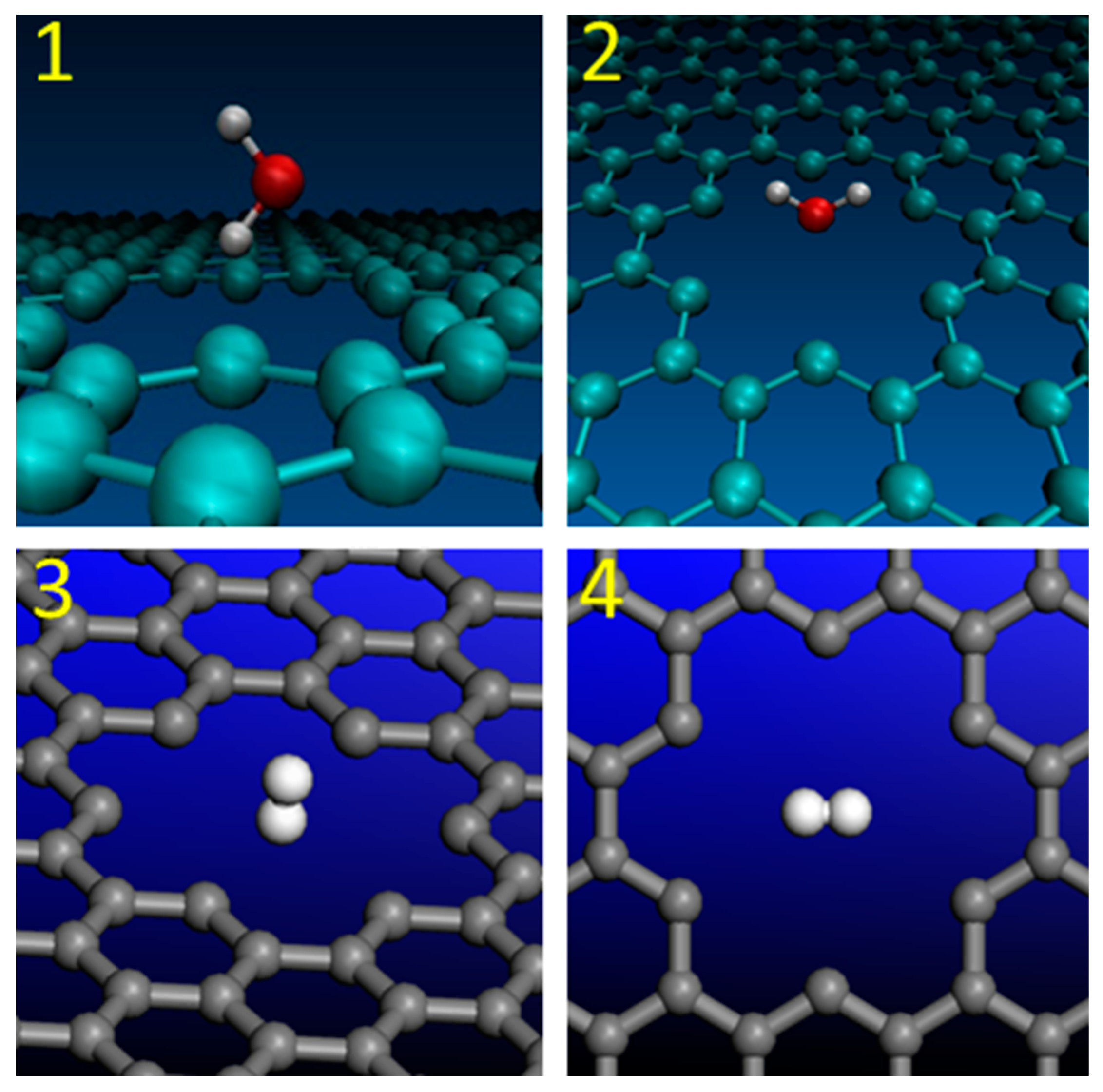

Molecular orientations of H

2O and H

2 were also considered during the transfer through graphene nanopores. First two model structures include the water molecules with “H atom at the bottom” and “O atom at the bottom” molecular orientations. They are presented as Model 1 and Model 2 in

Figure 2. The term “at the bottom” implies the specified location of the atom that pointing towards the nanopore. Model 2 was selected for large nanopore calculations.

Two different orientations of the H

2 molecule are presented in

Figure 2. They are labelled as Models 3 and 4. In the Model 3 structure, the H

2 molecule with “vertical” orientation was placed in the middle of the regular graphene nanopore in a way that one of the hydrogen atoms was pointing down towards the center of the nanopore. In the Model 4 structure, the “horizontal” orientation of H

2 molecule implies that both hydrogen atoms are placed in the same plane that is parallel to the graphene plane.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Nanopore Size and Molecular Orientation Effect on Tunneling Mechanism

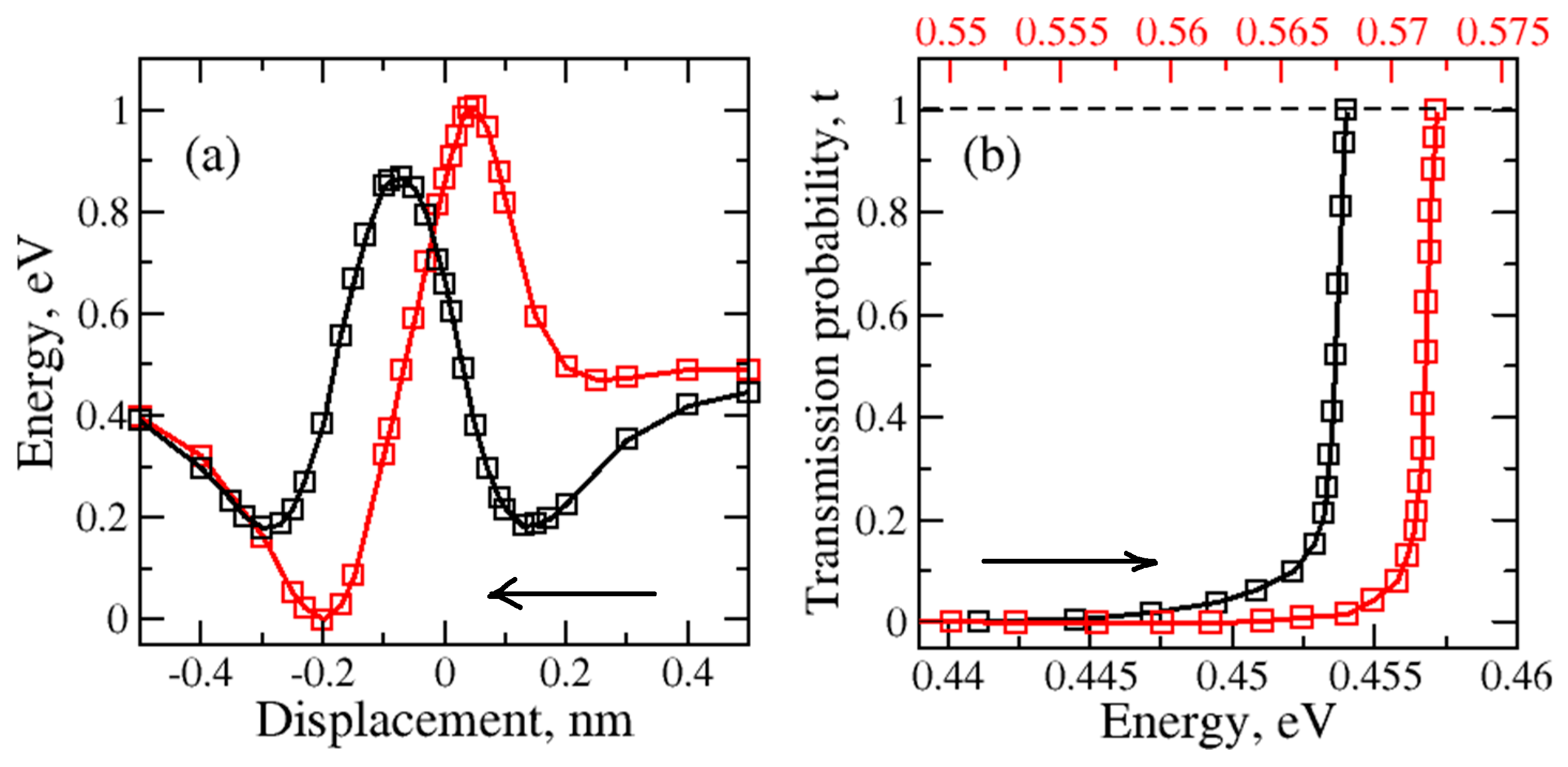

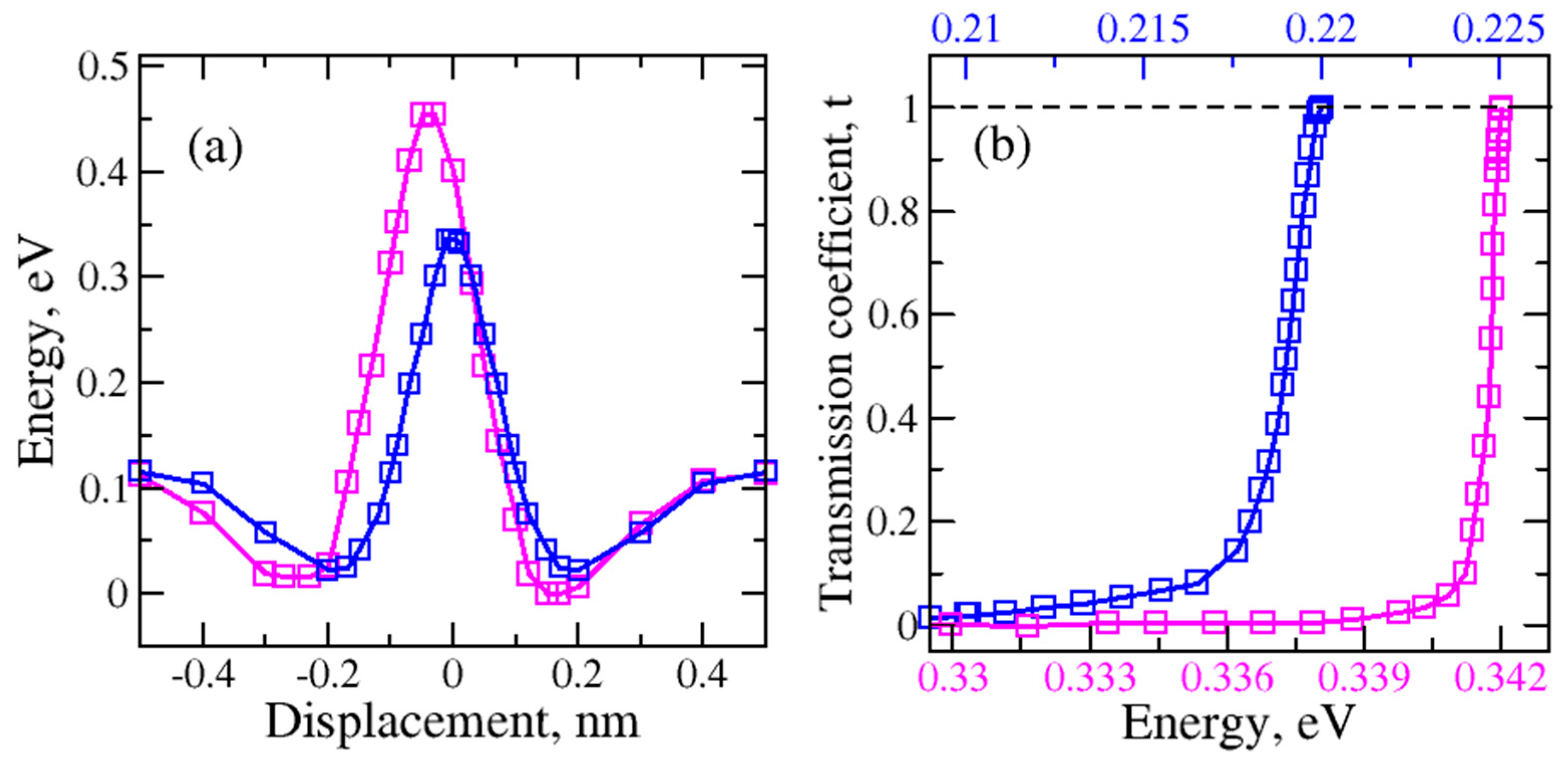

During the one-dimensional displacement of the molecule passing through the nanopore, the total energy changes. This energy decreases first due to adsorption and it increases as the molecule gets closer to the center of the nanopore. As long as the nanopore is not too large, there will be a potential energy barrier for molecular transport. The potential energy barriers for graphene – H

2O and graphene - H

2 were calculated. Two different molecular orientations of water molecule are considered. These are “O atom at the bottom” and “H atom at the bottom” for the regular and large nanopores (please see

Figure 1 and

Figure 2). The tunneling probabilities are calculated using the WKB method which depend on the barrier heights and the kinetic energy of the molecule. The tunneling probabilities for different kinetic energy values are presented in

Figure 3.

Initially, the H

2O molecule was 0.50 nm above the nanopore. The nanopore within the graphene was at 0.0 nm. The water molecule passing through the nanopore with “O atom at the bottom” orientation (

Figure 3 - red) shows that the total energy first decreases and then increases when the oxygen atom began to approach the nanopore. The highest increase was observed as the oxygen atom reached the nanopore at 0.0nm. After another 0.2 nm translation, the total potential energy decreases and it creates a potential energy well (region: 0 nm to -0.5 nm) behind the nanopore. The molecule can be trapped in this potential energy well.

The results for the “H atom at the bottom” orientation passing through the regular size nanopore are shown in

Figure 3. When the first hydrogen atom started to approach the nanopore the decrease in potential Energy caused the creation of the first potential energy well (region: 0.5 nm to 0.1 nm). The significant grow in the barrier height was detected as the oxygen atom came close to the plane of the nanopore. Then the second hydrogen atom followed the path which led to the second potential well (region: -0.1nm to -0.5nm).

The kinetic energy thus temperature dependence on the tunneling probability of the water molecule with “O atom at the bottom” and “H atom at the bottom” orientations passing the regular graphene nanopore was computed for one-dimensional case (

Figure 3(b) - red and black, respectively). The increase in the tunneling probability was observed with the raise in kinetic energy of the water molecule as the temperature increases. The tunneling occurs at a higher temperature range for “O atom at the bottom” than for “H atom at the bottom” water molecule orientation. The higher temperature indicates that the higher kinetic energy is required for the molecule to be able to tunnel through the barrier. This makes the tunneling harder for “O atom at the bottom” than for “H atom at the bottom” water molecule orientation.

The effect of molecular orientation on the possible adsorption mechanism is also clear. The “O atom at the bottom” case has higher adsorption energy if the molecule is trapped on the other side of the nanopore. Please also note the symmetric and asymmetric variation of the total energy due to molecular orientation.

The large graphene nanopore results are presented in

Figure 4. Similar asymmetric total energy variation was observed in the “O atom at the bottom” case.

In contrast with the regular nanopore, the significant difference in the potential barrier height was observed for the larger nanopore. The increase in the graphene nanopore size caused the lowering but also the broadening of the potential energy barrier. For the large nanopore size the tunneling can be observed at the lower kinetic energies. In contrast, for both molecular orientations, the tunneling through the regular nanopore occurs at higher kinetic energies of the water molecule to be able to penetrate through the barrier during the molecular transfer.

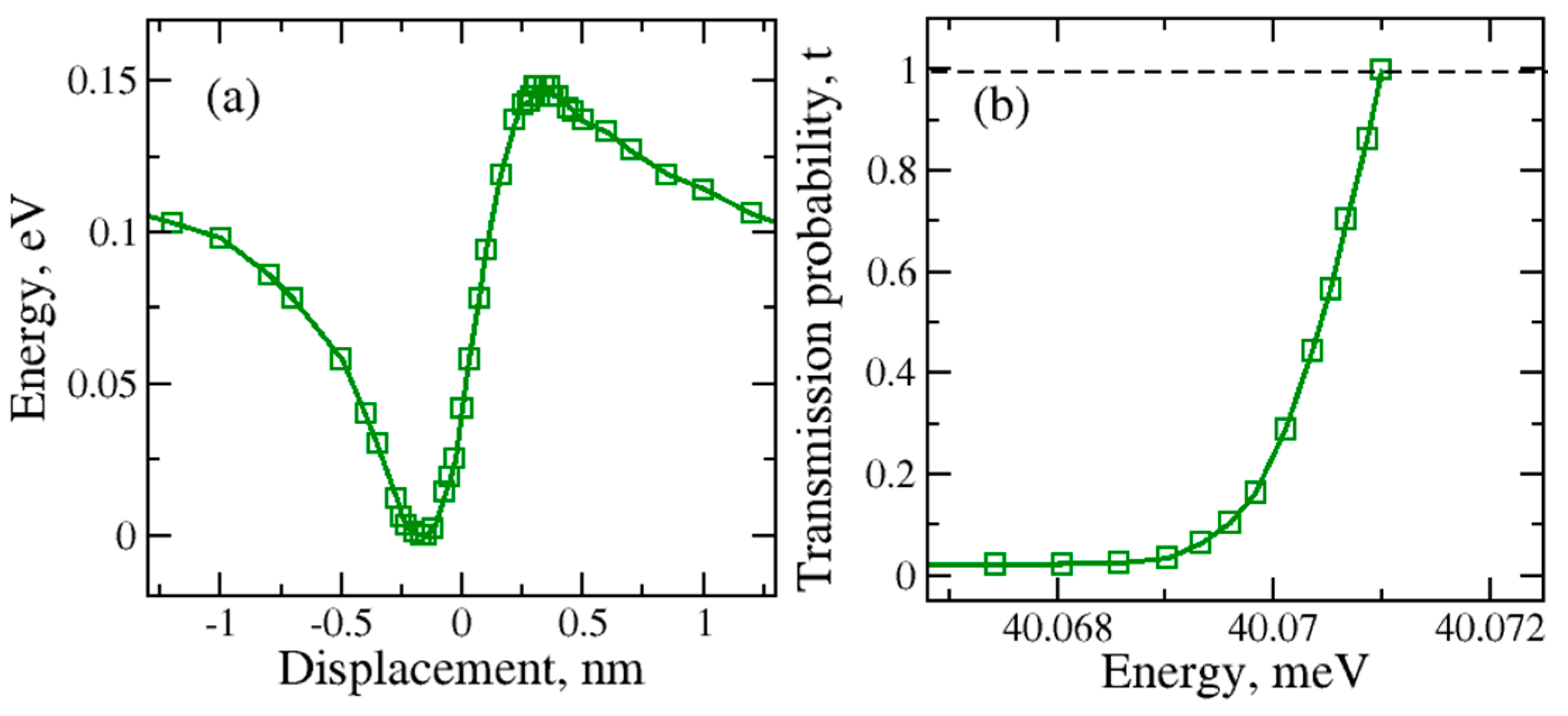

The tunneling of H

2 molecule through the regular nanopore were investigated for two different molecular orientations. The horizontal and vertical orientations of H

2 molecule were considered. The results for these orientations are presented in

Figure 5.

Due to its lower potential energy barrier, the H2 molecule would tunnel through the nanopore with less kinetic energy and at lower temperatures when it is compared to the H2O molecule case. The two potential wells are created in the front and behind the nanopore.

By comparing different molecular orientations of H2 molecule during the tunneling, we found that H2 molecule with “horizontal” orientation created a lower potential energy barrier than H2 molecule with “vertical” orientation. This orientation dependence can be explained by the increased interaction of hydrogen atoms in the molecule with graphene as the molecule approaches the nanopore vertically.

We studied the impact of the higher kinetic energy and thus the temperature on the tunneling or transmission probability of H

2 molecule transferred through the regular nanopore. As it can be seen in

Figure 5(b), higher kinetic energies and temperatures are required for the tunneling of the H

2 in the “vertical” orientation. Lower kinetic energies and temperatures are sufficient for the tunneling of H

2 molecule having the “horizontal” orientation. This makes the tunneling easier with the “horizontal” than with “vertical” orientations.

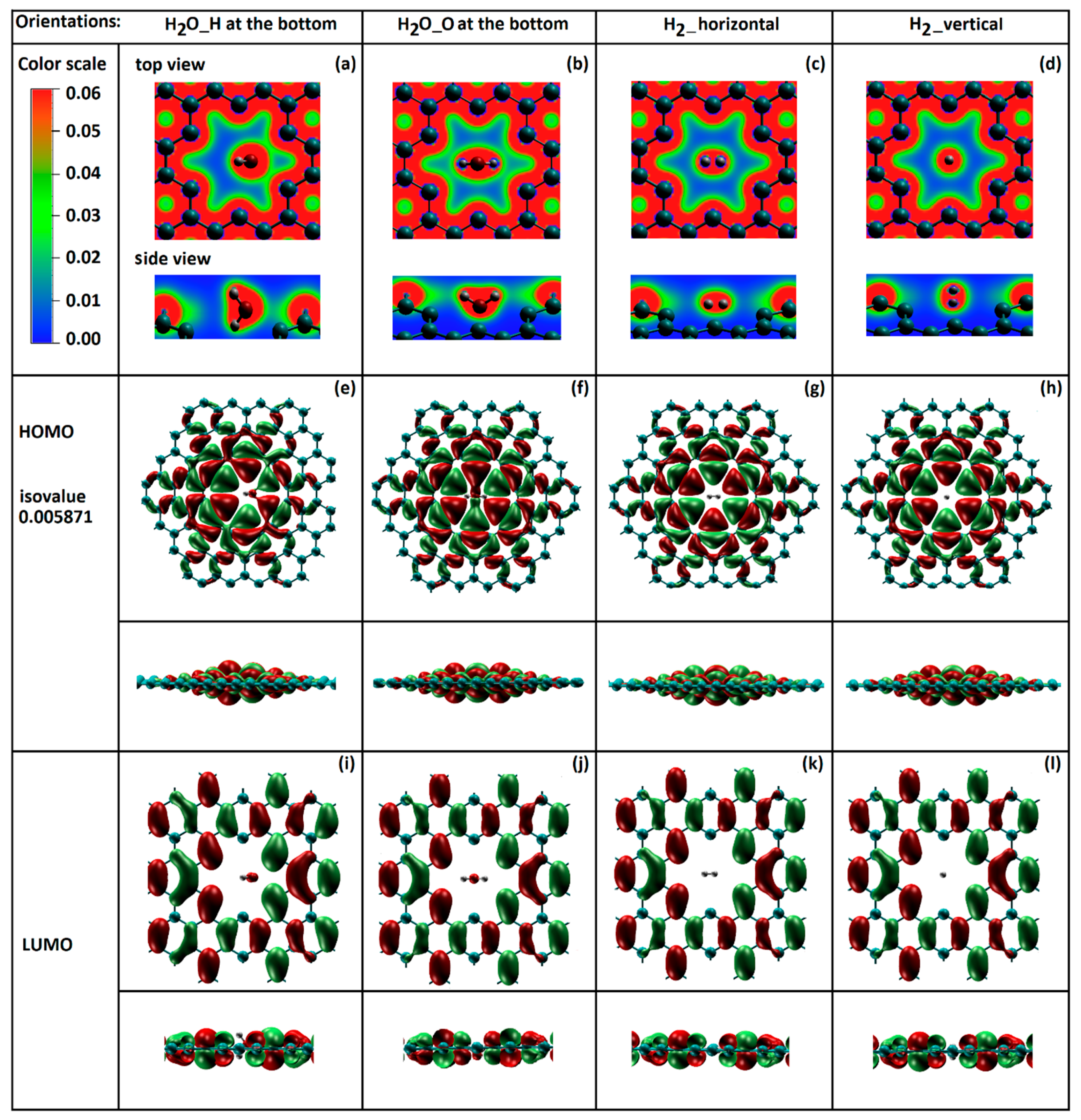

3.2. Total Electron Density of Gas Molecules inside the Graphene Nanopore

To understand the interactions between the molecules and graphene nanopore, we investigate the total electron density of H

2 and H

2O molecules inside the regular size nanopore.

Figure 6(a-d) shows the total electron density distribution of H

2O with “H atom at the bottom”, H

2O with “O atom at the bottom”, H

2 with “horizontal” orientation and H

2 with “horizontal” orientations, respectively. The top and side views are relative to the graphene plane. We found a significant difference in total electron density distribution between the H

2O and H

2 molecule transfer cases. The higher total electron density between H

2O molecule and graphene (

Figure 6(a,b)) implies the higher molecular orbital overlap and stronger interaction. There may be also a possible charge transfer between the water molecule and the graphene.

For a deeper understanding of the molecular orientation impact on the potential energy barriers we study the highest occupied (HOMO) and lowest unoccupied (LUMO) molecular orbitals. The molecular orbital isosurfaces for all four orientations are shown in

Figure 6 at the fixed isovalue of 0.005871. As can be seen in the HOMO isosurface of the H

2O molecule with both orientations (

Figure 6 (e, f)) the electronic charge transfer between the water molecule and the graphene present. The interaction difference in these two orientations was also observed. In each orientation, oxygen from the water molecule tends to bind to the closest carbon atoms of the graphene nanopore. The weaker interaction was observed for H2O_H at the bottom orientation than for the H2O_O at the bottom orientation (

Figure 6 (f)).

The HOMO isosurfaces of H

2 molecules (

Figure 6 (g, h)) show much weaker interaction with the graphene in comparison to the water molecules. This may be due to the smaller molecular size of H

2. This also validates the results for the lower potential energy barriers for H

2 molecules.

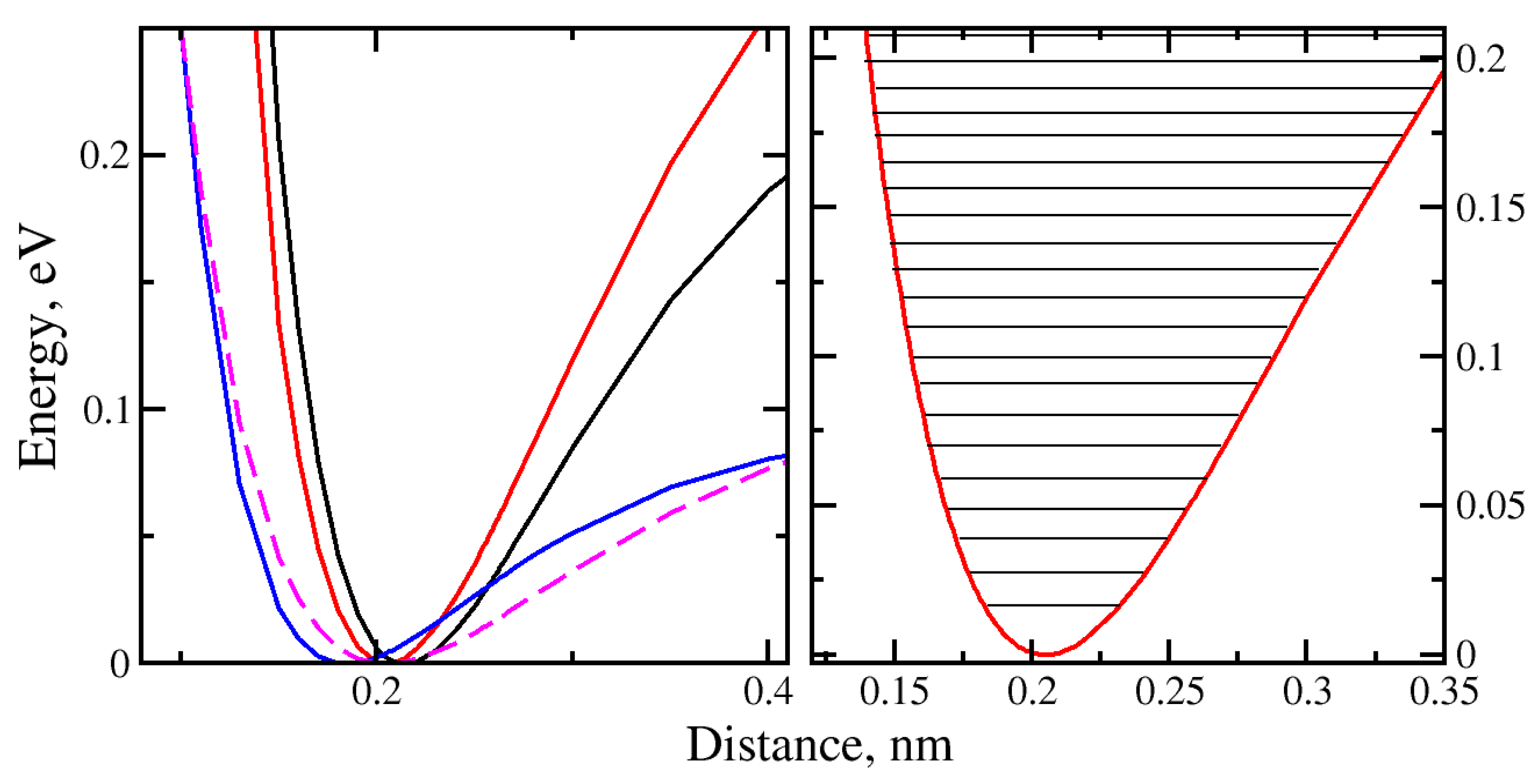

3.3. Molecule Trapping in a Potential Well behind the Graphene Nanopore

When molecules cross the nanopore plane they can be trapped in the potential well or quantum well behind the nanopore. We investigated the molecular “trap-escape” mechanism from the potential well. Using the harmonic fitting at the bottom of each well, the ground-state zero-point energy was calculated. We utilized the mathematical concept of the Morse potential to calculate the quantized energy levels. The quantization of the translational motion energies was found from the confinement of H2O and H2 by the graphene nanopore. Well-defined separation of the quantized translational energy levels was observed for both H2 and H2O due to the small weight of the molecules.

The eigenstates of the translational motion of H2O and H2 were calculated as the molecules get trapped in the potential well behind the nanopore. For the symmetric total energy potential energy variation cases, the potential well can also be the one in front of the nanopore. The system was treated quantum mechanically for the one-dimensional translational motion with the bound-state approach. The ground-state zero-point energies (E0) were calculated at the bottom of each potential well, and the anharmonic part was treated using the Morse potential.

The quantized translational energy levels were calculated for the potential energy wells of H

2O and H

2 in front of or behind the regular nanopore. The fitted Morse potential energy well obtained by the translational motion of H

2O with “H atom at the bottom” orientation, denoted as model 1, can be observed on the

Figure 8 represented as solid black line.

The potential well of the H

2O molecule with the “O at the bottom” orientation (model2) is represented with a solid red line. The potential wells of H

2 with “vertical” and “horizontal” orientations (models 3 and 4) are shown in

Figure 8 in magenta and blue colors, respectively. The evidence of the molecular orientation effect on the “trapping” mechanism was found.

The deepest potential well was observed for H2O with “O atom at the bottom” molecular orientation (De = 0.3978eV). The shallowest potential well (De = 0.0962eV) was for H2 molecule with “horizontal” orientation in front of or behind the regular nanopore. This implies that, in comparison with H2O, significantly less kinetic energy is required for H2 to escape the potential well.

The ground-state energies for the models of 1 through 4 were calculated with the values of 5.437meV, 5.677meV, 9.506meV and 11.410meV, respectively. The smallest ground-state energy was found for H2 with “horizontal” orientation.

The effect of the molecules being trapped behind the nanopore can discussed by looking at the number of quantized energy levels in the translational degree of freedom that was calculated for each individual potential well corresponding to the particular model (

Table 1). The highest number of the translational energy levels (n) was found for the models 1 and 2 that correspond to the water molecule penetration through the nanopore. This can be explained due to the mass deviation between H

2 and H

2O molecules and the increased interaction with the oxygen atom of the H

2O molecule and the graphene atoms.

Considering the quantum mechanical problem in one-dimensional case, we calculated the kinetic energy and temperature required for the molecule to escape the potential well. The lower kinetic energies are needed for H2 with both orientations to escape the well. Please note that kB.T at room temperature is roughly 26 meV. Overall, for all the models studied, relatively high temperatures are required for H2 and H2O molecules to escape the potential wells during the transport. This implies that at relatively lower temperatures, the H2 and H2O molecules would be trapped in front of the nanopore or right behind it. On the other side, there can be molecular collision events and radiation absorption which can assist their escape.

3. Conclusions

Quantum tunneling of H2 and H2O molecules through graphene nanopores was studied by performing ab initio calculations based on density functional theory. We found that molecular tunneling depends on the nanopore size, the molecule size and the molecule’s orientation. It also depends on the kinetic energy of the molecule and thus the temperature. For the H2O molecule, the tunneling occurs at the higher energy and temperature range for “O atom at the bottom” than for “H atom at the bottom” water molecule orientation. Lower kinetic energies and temperatures are sufficient for the tunneling of H2 molecule having the “horizontal” orientation. We also found that there can be potential energy wells in front of or behind the nanopores and H2 and H2O molecules can be trapped inside these potential wells. Our studies showed that relatively larger kinetic energies and temperatures are required for the molecules to escape the wells, however, molecular collisions and radiation absorption can assist the escape of the molecules. We believe that the unique fundamental differences in quantum tunneling and adsorption behaviors of the molecules would be very helpful for the gas separation and nanofiltration technologies.

Author Contributions

“Conceptualization, A.B.; methodology, A.B., L.B.; investigation, L.B.; writing—original draft preparation, L.B.; writing—review and editing, A.B.; supervision, A.B.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.”.

References

- Bunch, J.S.; Verbridge, S.S.; Alden, J.S.; van der Zande, A.M.; Parpia, J.M.; Craighead, H.G.; McEuen, P.L. Impermeable Atomic Membranes from Graphene Sheets. Nanolett. 2008, 8, 2458–2462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Hern, S.C.; Boutilier, M.S.H.; Idrobo, J.C.; Song, Y.; Kong, J.; Laoui, T.; Atieh, M.; Karnik, R. Selective Ionic Transport through Tunable Subnanometer Pores in Single-Layer Graphene Membranes. Nano Lett. 2014, 14, 1234–1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen-Tanugi, D.; Grossman, J.C. Water Desalination across Nanoporous Graphene. Nano Lett. 2012, 12, 3602–3608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sumedh, P.S.; Smirnov, S.N.; Vlassiouk, I.V.; Raymond, R.U.; Gabriel, M.V.; Sheng, D.; Shannon, M.M. Water desalination using nanoporous single-layer graphene. Nature Nanotechnology 2015, 10, 459–464. [Google Scholar]

- Boutilier, M.S.H.; Sun, C.; Hern, C.O.; Hadjiconsttantinou, N.G.; Karnik, R. Implication of Permeation through Intrinsic Defects in Graphene on the Design of Defect-Tolerant Membranes for Gas Separation. ACS Nano 2014, 8, 841–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, C.; Boutilier, M.S.H.; Au, H.; Poesio, P.; Bai, B.; Karnik, R.; Hadjiconsttantinou, N.G. Mechanism of Molecular Permeation through Nanoporous Graphene Membranes. Langmuir 2013, 30, 675–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koenig, S.P.; Wang, L.; Pellegrino, J.; Bunch, J.S. Selective molecular sieving through porous graphene. Nature Nanotechnology 2012, 7, 728–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, H.; Li, J.; Zhang, J.; Su, G.; Li, X.; Zhao, Y. Separation of Hydrogen and Nitrogen Gases with Porous Graphene Membrane. J. Phys. Chem. 2011, 115, 23261–23266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, D.; Cooper, V.R.; Dai, S. Porous Graphene as the Ultimate Membrane for Gas Separation. Nano Lett. 2009, 9, 4019–4024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Viana, D.; Walston, S.T.; Masvidal-Codina, E.; Illa, X.; Rodríguez-Meana, B.; del Valle, J.; Hayward, A.; Dodd, A.; Loret, T.; Prats-Alfonso, E.; et al. Nanoporous graphene-based thin-film microelectrodes for in vivo high-resolution neural recording and stimulation. Nature Nanotechnology 2024, 19, 514–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamamoto, M.; Goto, S.; Tang, R.; Yamazaki, K. Toward three-dimensionally ordered nanoporous graphene materials: template synthesis, structure, and applications. Chemical Science 2024, 15, 1953–1965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lv, H.; et al. Functional nanoporous graphene superlattice. Nature communications 2024, 15, 1295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- VandeVondele, J.; Krack, M.; Mohamed, F.; Parrinello, M.; Chassaing, T.; Hutter, J. QUICKSTEP: Fast and accurate density functional calculations using a mixed Gaussian and plane waves approach. Comput. Phys. Comm. 2005, 167, 103–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang C., Zhang W., Sun H., van Horn R.M., Kulkarni R.R., Tsai C., Hsu C., Lotz B., Gong X. and Cheng S. Z. D. Adv. Energy Mater 2012, 2, 1375.

- VandeVondele, J.; Hutter, J. Gaussian basis sets for accurate calculations on molecular systems in gas and condensed phases. J. Chem. Phys. 2007, 127, 114105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goedecker, S.; Teter, M.; Hutter, J. Separable dual-space Gaussian pseudopotentials. Phys. Rev. B 1996, 54, 1703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grimme, S.; Antony, J.; Ehrlich, S.; Krieg, H. A consistent and accurate ab initio parametrization of density functional dispersion correction (DFT-D) for the 94 elements H-Pu. J. Chem. Phys. 2010, 132, 154104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, D.C.; Nocedal, J. On the Limited Memory BFGS Method for Large Scale Optimization. Math Prog. 1989, 45, 503–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morse, P.M.; Feshbach, H. Methods of Theoretical Physics, 1 st ed.; McGraw Hill: New York, Ny, USA, 1953. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).