1. Introduction

Carbon materials are among the most promising candidates for hydrogen (H

2) storage due to their lightweight nature and chemical stability.[

1,

2,

3] For instance, the interactions between carbon nanotubes (CNTs) and H

2,[

4,

5,

6] as well as between graphene (GR) and H

2, have been extensively studied.[

7,

8,

9] However, the binding energies of H

2 to these carbon materials are typically less than 1 kcal/mol,[

10,

11] which results in low hydrogen storage efficiency for pristine carbon materials.

To address this limitation, alkali metals such as lithium atoms or ions have been doped onto carbon surfaces. For example, lithium-doped graphene (GR-Li) has been shown to increase the adsorption energy of H

2 to approximately 5–6 kcal/mol.[

12,

13] Moreover, it has been reported that up to 10 H

2 molecules per Li atom can be efficiently bound to GR-Li. Other metals, such as Na, K, Mg, and Al, have also been shown to have hydrogen storage capacity.[

14,

15,

16,

17]

In the present study, we theoretically explore the potential of hydrogen storage via chemical bonding between GR nanoflakes and hydrogen atoms. One known approach for chemical hydrogen storage is the hydrogenation of aromatic hydrocarbons (organic chemical hydride method), which allows for both the storage and transport of hydrogen in a chemically bound form. A representative example is the hydrogenation of benzene to cyclohexane:[

18,

19,

20,

21]

Cyclohexane is produced by the addition of hydrogen atoms to the π-bonds of the benzene ring. This product can be transported, and hydrogen can later be released via catalytic dehydrogenation. Thus, both metal doping and chemical hydrogenation are considered viable strategies for H2 storage.

In the present study, we perform a molecular-level design of a GR-based hydrogen storage system using direct ab initio molecular dynamics (AIMD) simulations.

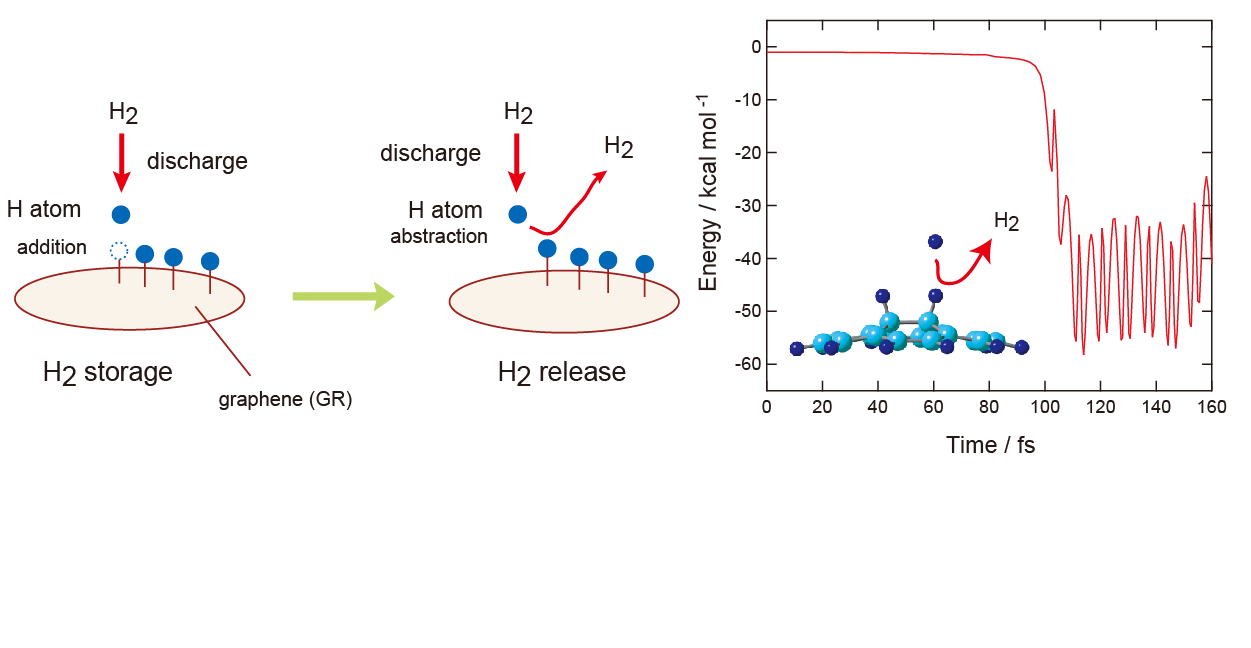

Figure 1 shows a schematic illustration of the reaction model investigated in this study. The overall process can be described as follows:

Molecular hydrogen (H

2) is readily dissociated into atomic hydrogen via electrical discharge. The resulting hydrogen atoms are then introduced to the graphene surface, where they react with carbon atoms to form C–H bonds on GR surface:

Through this process, H

2 is stored on GR surface in the form of two hydrogen atoms (H

2 storage). The release of hydrogen can occur via the following reactions:

The H-atom, generated by discharge, attacks to the C-H hydrogen of H-(GR)-H, and then H

2 is formed (H

2 molecule). The primary reaction of interest in this study is the hydrogen release process (H

2 release):

For comparison, we also investigate the energetics of the hydrogen addition reaction:

Both the energetics and the reaction times for hydrogen storage and release are evaluated using direct AIMD simulations.

For Reaction II,[

22,

23] we investigated previously the activation and reaction energies by means of DFT methods. Also, direct H

2 addition reaction to GR, H

2 + GR → H-(GR)-H (Reaction III), were investigated.[

24] The activation energies of Reactions II and III were calculated to be 5-7 and 80 kcal/mol, respectively.[

22,

23,

24] These results indicated that the direct H

2 addition to GR (Reaction III) is impossible under the normal condition. In contrast, Reaction II is possible in normal condition if H-atom is generated.

3. Results

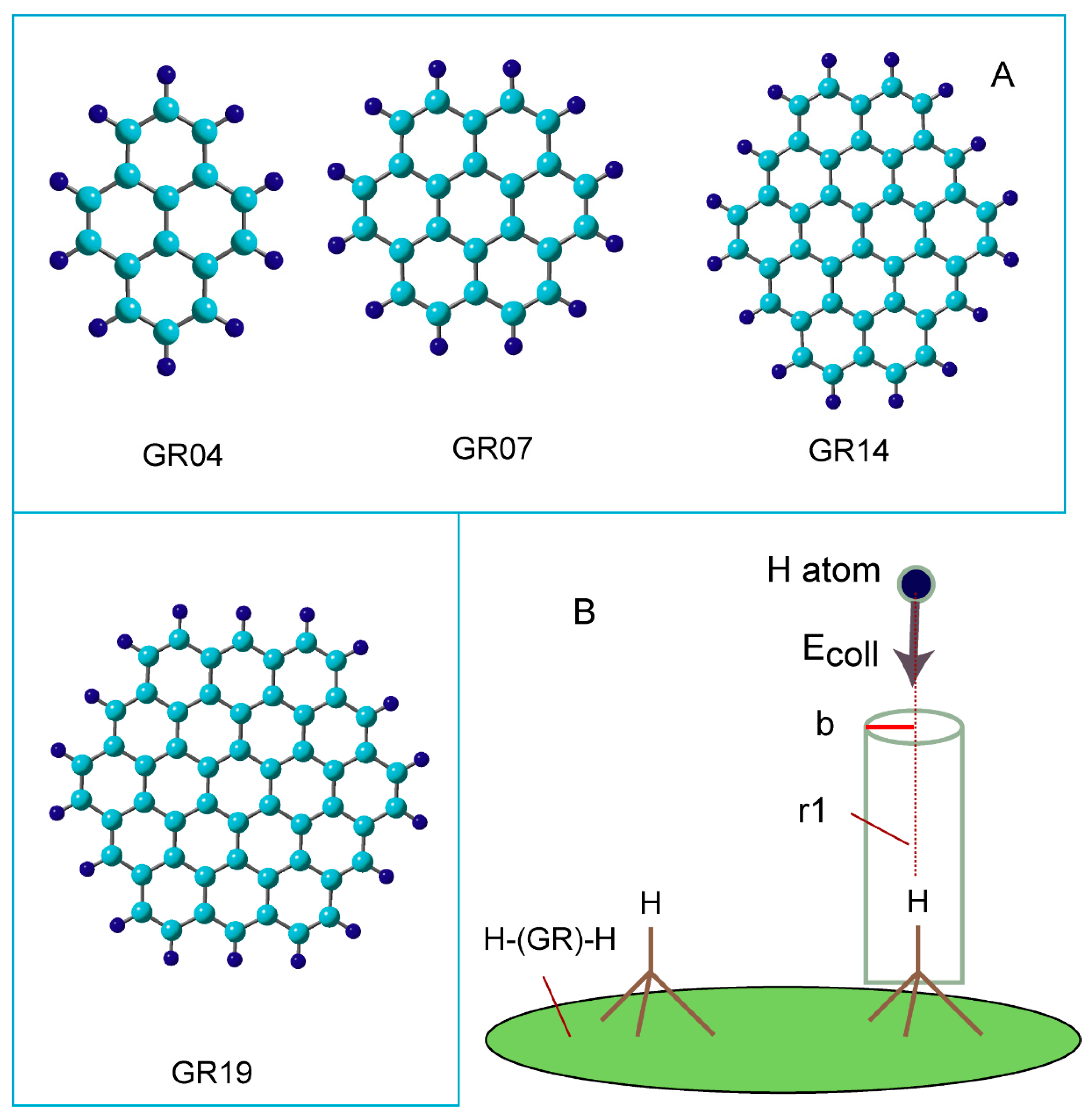

Figure 3 shows the optimized structures along the reaction coordinate for the reaction:

where H-(GR)-H means hydrogenated GR (two H-atoms are added to the surface of GR).

At reactant state (RC), the C-H bond length was calculated to be r2=1.099 Å. After the injection of hydrogen (H) atom to H-(GR)-H, van der Waals (vdW) complex was first formed on the surface in the initial state of the reaction (denoted to vdW-1). The H-atom was located between two surface C-H sites and made the bridge structure composed of C-H--H--H-C (r1=2.237 and r3=2.550 Å). The C-H bond was slightly elongated by the interaction with the H-atom (the C-H bond length was changed from r2= 1.099 to 1.101 Å).

Next, the reaction reached to transition state (TS) via vdW-1. The H-atom was located at r1=1.772, and r3=2.930 Å at TS. The C-H bond of the surface C-H site was elongated at TS (r2=1.111 Å). The H-H bond (r1=1.772 Å) was significantly longer than that of H2 molecule in gas phase (r(H-H)= 0.746 Å). After TS, H2 molecule was formed by the H-atom abstraction.

In the final state of the reaction, vdW complex was formed (vdW-2), where H2 was weakly bound to the radical site of the surface. H2 was located at r2=3.301 Å from the surface. The H-H bond of H2 was r1=0.747 Å, which is a normal bond length of H2 molecule. After the H2 reduction from H-(GR)-H, the product (PD) was remained as H-(GR).

- B.

Energy diagram for the hydrogen abstraction reaction

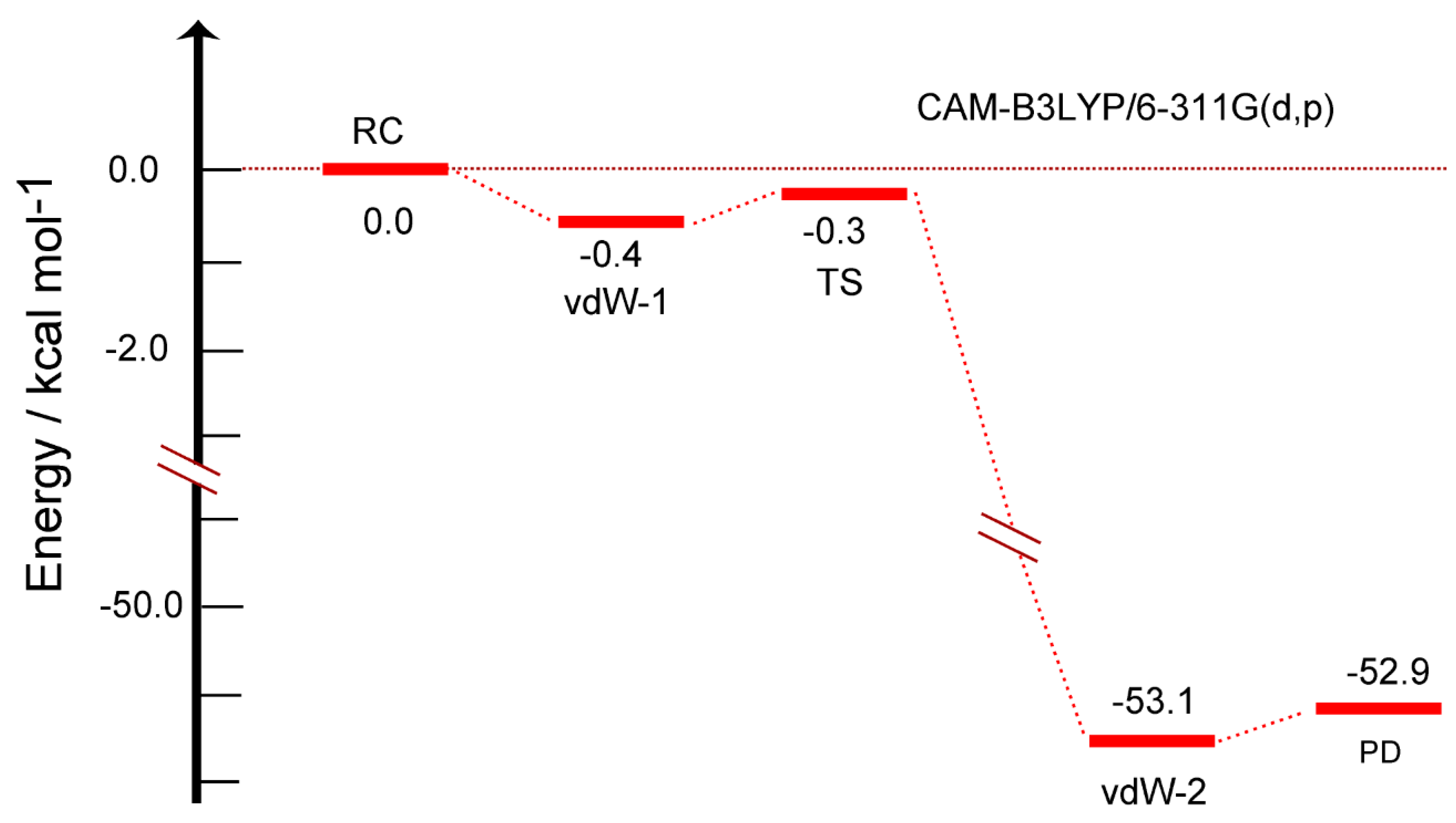

The energy diagram for the reaction is given in

Figure 4. The energy level of RC corresponds to the total energy of H-GR-H + H. The initial vdW state (vdW-1) was -0.4 kcal/mol lower in energy than that of RC (zero level). The energy of TS was -0.3 kcal/mol, indicating that the hydrogen abstraction reaction can proceed without activation energy.

After TS of the H-abstraction, the energy of reaction system decreased largely to -53.1 kcal/mol because the H-H bond was newly formed by the formation of H2. The energy level of vdW state at the PD state was -53.1 kcal/mol (vdW-2). The energy of product state (PD) (-52.9 kcal/mol) was slightly higher than that of vdW-2, where H2 was dissociated from the surface. The reaction can be expressed as:

RC[H(radical) + H-(GR19)-H] → vdW-1 → TS → vdW2 → PD[(GR19)-H + H2]. This reaction spontaneously occurs without activation barrier.

- C.

Intrinsic reaction coordinate

The intrinsic reaction coordinate (IRC) for the hydrogen abstraction reaction from H-(GR)-H was calculated at the CAM-B3LYP/6-31G(d) level. The result is given in

Figure S1 (in supporting information: SI). The point at s=0.0 in (amu)

1/2Bohr corresponds to TS structure in the reaction, and the points at s= -0.5 and s=3.0 indicate the reactant and product regions, respectively. The shape of IRC suggested that the energy decreases drastically after the TS point because the H

2 molecule with a strong H-H bond is formed. The structure at s= -0.5 was close to that of vdW-1. After TS, the energy decreased largely to -23.0 kcal/mol (

s=1.2) and -55.0 kcal/mol (

s =3.2). At

s=3.2, H

2 molecule dissociated from H-GR as H

2 molecule. This IRC calculation indicated that the TS structure connected between RC and PD states for the H-abstraction reaction.

- D.

Reaction dynamics

The direct AIMD calculations were carried out at the CAM/6-31G(d) level of theory. GR07 was used as graphene nanoflake. The collision energy was E

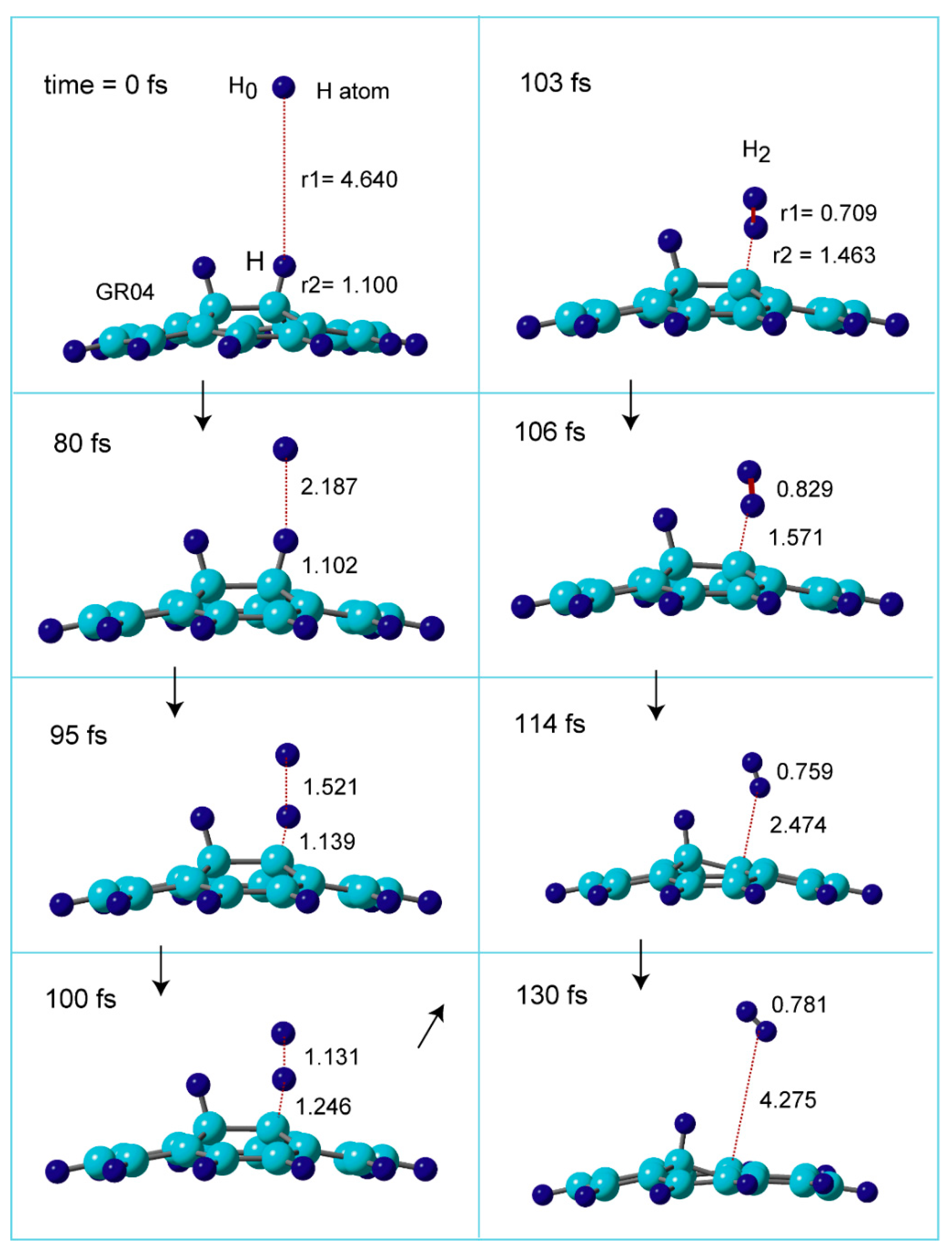

coll=1.0 kcal/mol. The snapshots of hydrogen abstraction reaction on GR are illustrated in

Figure 5, where the reaction is expressed as H + H-(GR)-H → H-(GR) + H

2.

In the initial structure at time = 0.0 fs, the H-atom was located at r1=4.640 Å. The C-H distance of surface as r2=1.100 Å. At time = 80 fs, the H-atom was located at r1=2.187 Å, and the C-H bond was r2=1.102 Å. The H-atom was more closed to the C-H (r1=1.521 and r2=1.139 Å) at 95 fs. At 100 fs, the structure was close to that of TS (r1=1.131 and r2=1.246 Å), indicating that the C-H bond was largely elongated by the H-abstraction (1.246 Å). At 103 fs, H2 molecule was completely formed: H-H bond length was r1=0.709 Å and H2 was located at r2=1.463 Å from the surface. The distances of H2 from the surface were changed to 1.571 Å (106 fs), 2.474 Å (114 fs), 4.275 Å (130 fs), suggesting that H2 leaved rapidly from the surface. Thus, the H-abstraction and H2 formation reactions were completed at 130 fs.

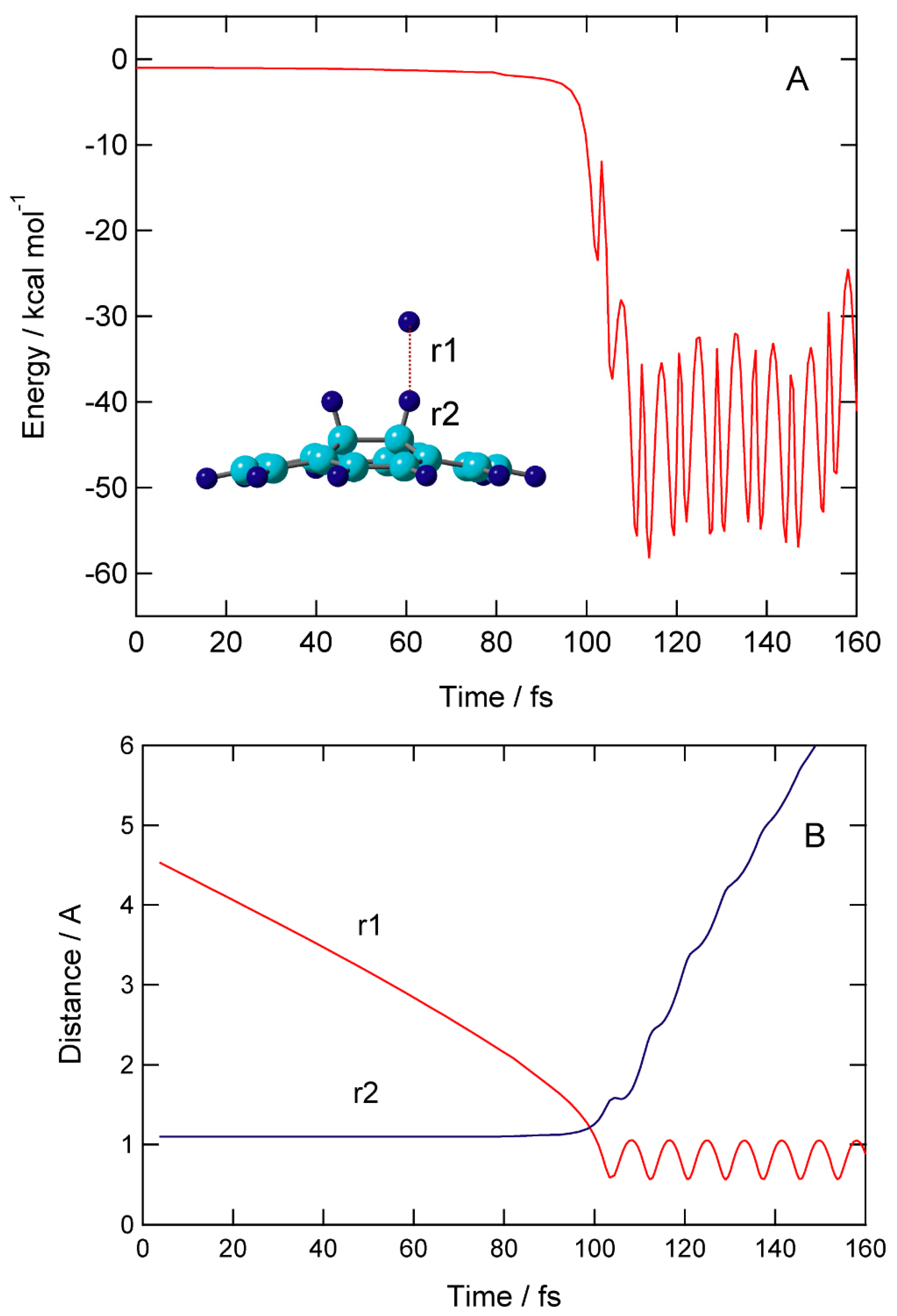

Time evolution of potential energy (PE) and interatomic distances (r1 and r2) are given in

Figure 6.

At time zero, the H atom started from r1=4.640 Å above the surface of H-(GR)-H. The H atom gradually approached to C-H site of H-(GR)-H: distances (r1, r2)= (3.460, 1.100) at 40 fs, (2.827, 1.101) at 60 fs, and (2.187, 1.102) at 80 fs. PE was slightly decreased: -0.5 kcal/mol at 80 fs. PE drastically changed around time= 100 fs, where the hydrogen abstraction rapidly occurred a time 95-105 fs. The H-H bond was newly formed after the abstraction, and H2 molecule was formed at this time. After the H2 formation, H2 was rapidly dissociated from the surface: the distances of H2 from the surface were 3.2 Å (120 fs) and 5.0 Å (140 fs). PE vibrated largely in the ranges (-40) - (-55) kcal/mol after the H2 dissociation.

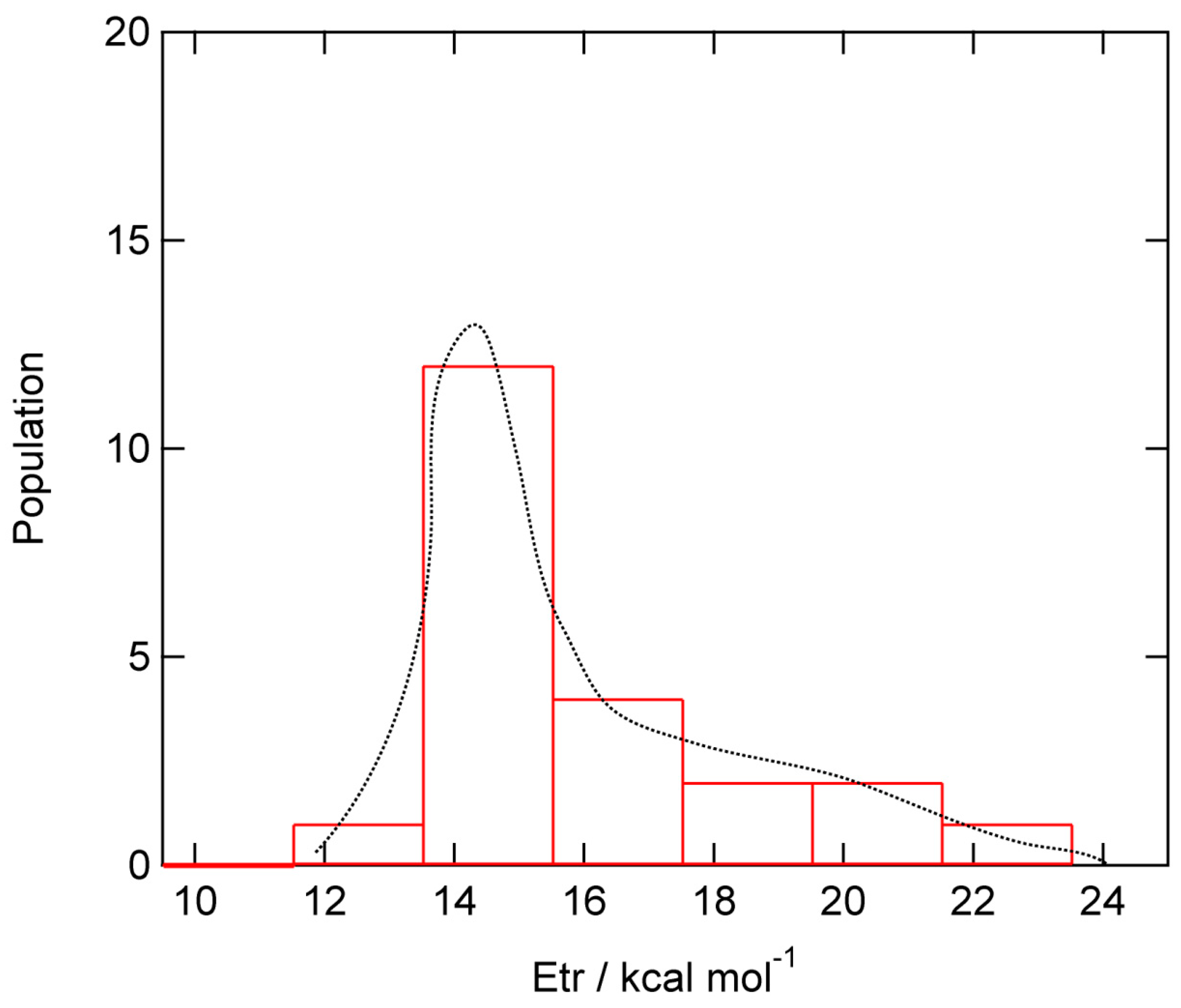

A total of 22 trajectories were run at collision energy of E

coll =1.0 kcal/mol. The translational energies of product H

2 (E

trans) formed by the H-abstraction reaction (H-(GR)-H + H → H-(GR) + H

2) are given in

Figure 7. E

trans’s were distributed in the ranges 12.0-22.0 kcal/mol with the peak of E

trans =15.0 kcal/mol. The average of E

trans was 14.9 kcal/mol, which is 26 % of total available energy. The remained energies were transferred into the vibrational modes of H

2-streetching mode and deformation modes of GR.

The time evolution of PE for selected five trajectories are given in

Figure S2. Also, the results of DFT-APFD functional are given in

Figure S3 for comparison. The similar results were obtained in both methods.

- E.

Hydrogen addition reaction to GR surface

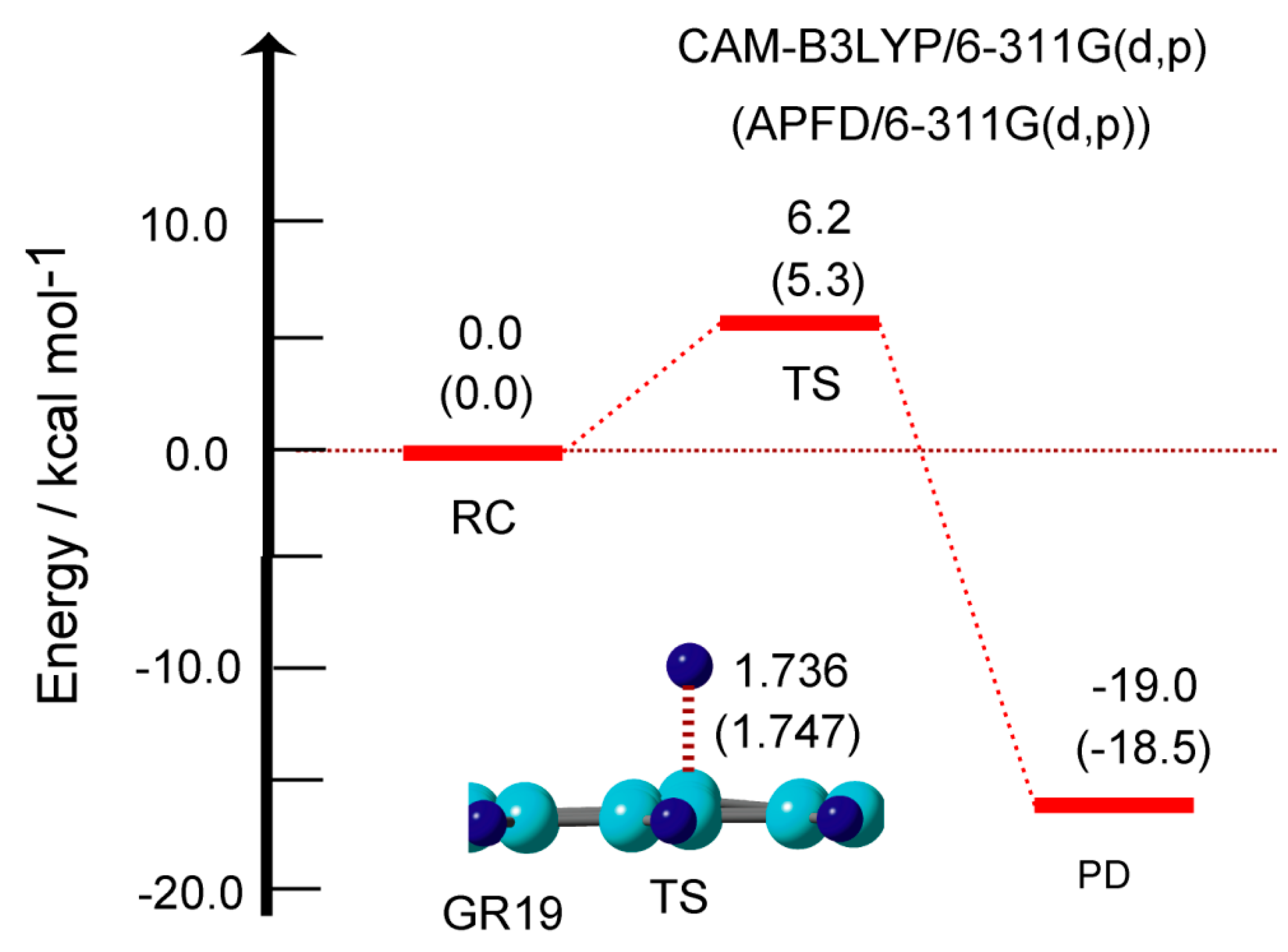

In previous sections, the hydrogen abstraction reaction was calculated and discussed. In this section, the hydrogen addition to the GR surface was re-examined. The reaction is expressed as GR + H → GR-H. In previous papers, we calculated the activation energies for the H-atom addition reaction to the GR surface using CAM-B3LYP functional. In this section, the energies were re-calculated using the APFD functional. The energy diagram and structure of TS for the H addition to the GR surface are given in

Figure 8.

At TS, the H atom was located at 1.736 Å from the surface. In case of GR19, the activation energy was calculated to be Ea= 6.2 kcal/mol (CAM-B3LYP) and 5.3 kcal/mol (APFD). The calculated activation energies for several sized GRs are given in

Table 1. The activation energies were 6.8 kcal/mol (GR04), 6.6 (GR07), and 5.6 (GR14), indicating that the activation energies were very low (Ea= 5-7 kcal/mol). This low activation barrier is due to the fact that the binding energies of H addition to the GR surface were large in the ranges 14.7-22.4 kcal/mol, as shown in

Table 1. The similar results were obtained by the APFD functional. These results indicated that both H-addition and abstraction reactions proceed under low activation energy on GR.

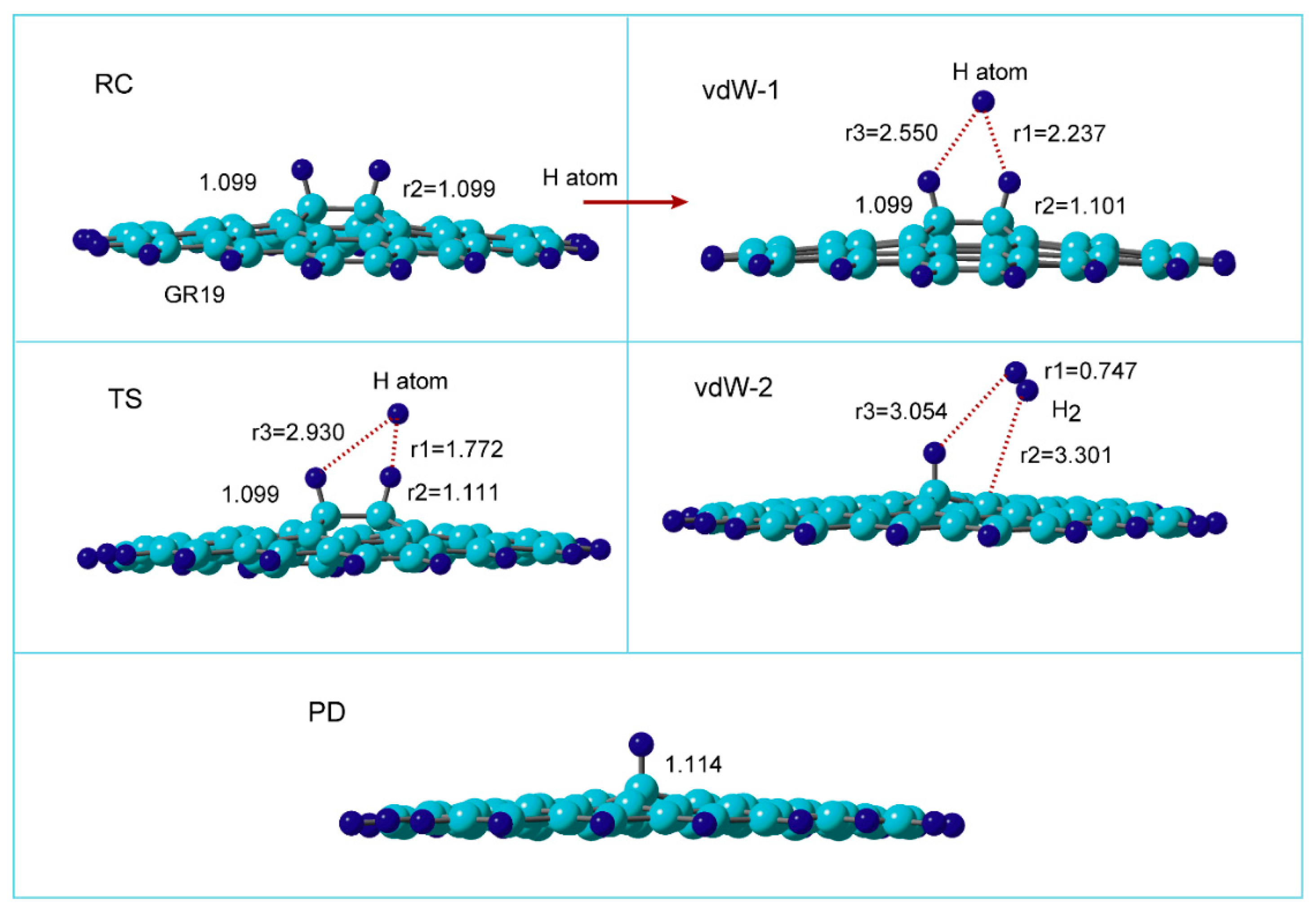

4. Discussion and Conclusions

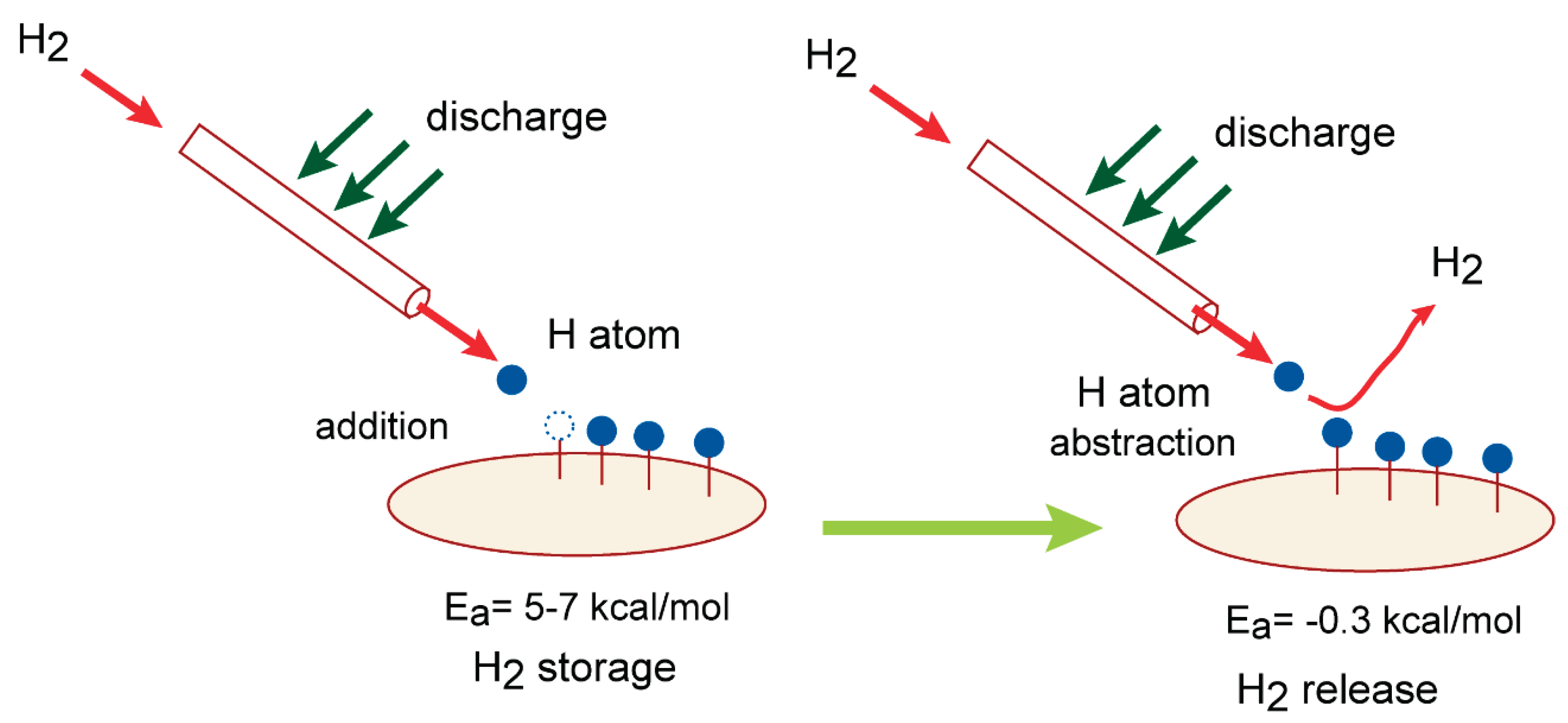

On the basis of the present calculations, the H

2 storage and release device is designed in this section. A schematic illustration H

2 storage/release device is given in

Figure 9.

In case of H

2 storage process, first, the H

2 gas is introduces into the reaction tube and H

2 is discharged. The hydrogen atom (H-atom) is easily generated: H

2 + discharge → H + H. The H-atom reacts with carbon atom of GR surface and GR-H (hydrogenated graphene) is formed:

This reaction can proceed with a low activation energy (Ea=5-7 kcal/mol). The hydrogen molecule (H2) is chemically captures as H-atoms on GR surface. The present calculations indicated that H2 storage process proceeds with low activation energy of 5-7 kcal/mol after the discharge.

In case of H

2 release process, H-tom is generated again by discharge of H

2. The H-atom reacts with H-atom on the GR surface and H

2 is easily formed by the H abstraction reaction:

This reaction can proceed also without activation energy (Ea= -0.3 kcal/mol: negative activation energy). The represent study thus designed the H2 storage/release device composed of graphene.

- B.

Conclusion

The development of hydrogen storage and release materials is one of the key themes in the development of a hydrogen society. In the present study, we theoretically designed hydrogen storage and release devices based on graphene (GR)—a lightweight and chemically stable material—using a direct AIMD approach. The calculations showed that the hydrogen addition reaction (H

2 storage):

proceeds with low activation energy (5-7 kcal/mol). Also, the hydrogen abstraction from hydrogenated graphene (H

2 release):

occurs without activation energy. The direct AIMD calculations indicate that H-atom abstraction proceeds without the reaction barrier. The model designed in this study could be a new hydrogen storage/release device.

Figure 1.

Schematic illustration of reaction model in the present study.

Figure 1.

Schematic illustration of reaction model in the present study.

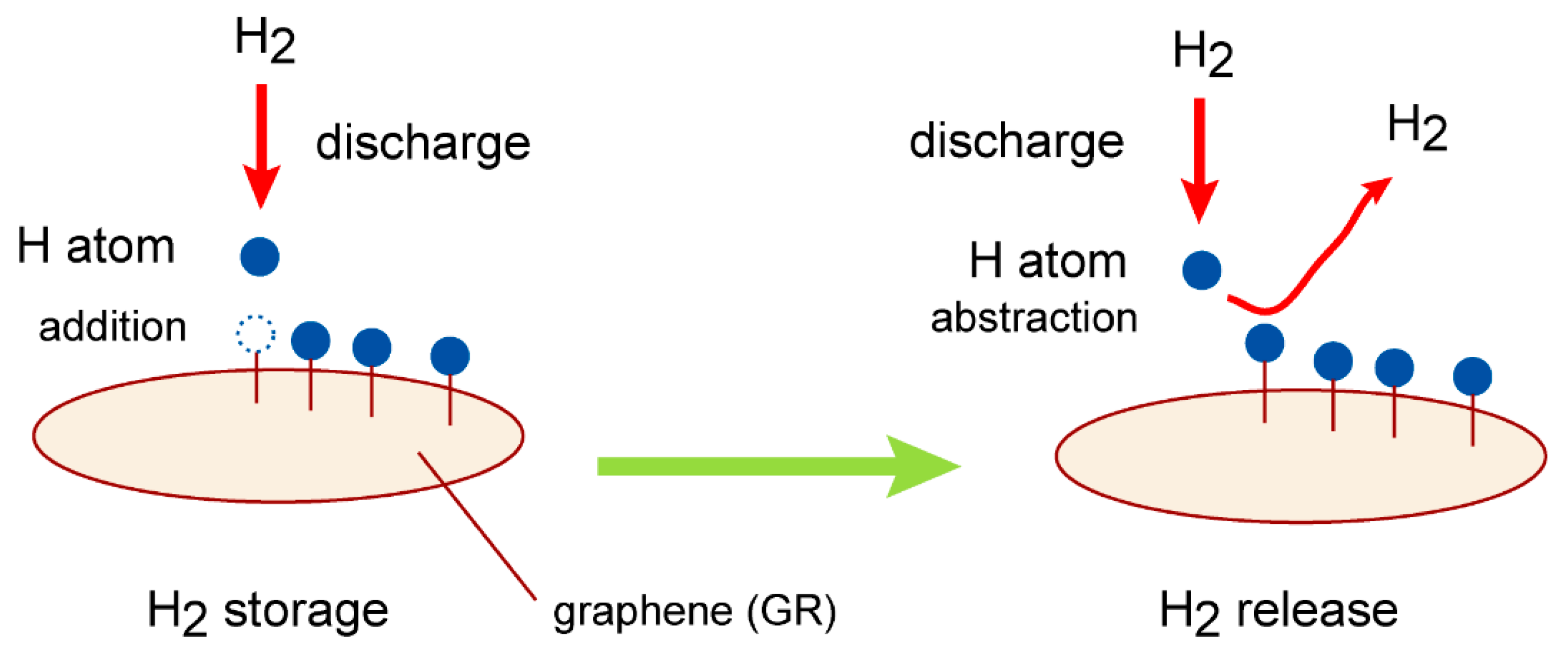

Figure 2.

(A) Graphene (GR) nanoflake used in the present study as a carbon material. GR04, GR07, GR14, and GR19 are composed of 4, 7, 14, and 19 benzene rings. The carbon atoms in the edge region are terminated by hydrogen atoms. (B) Initial geometry configuration in hydrogen abstraction reaction, H + H-(GR)-H → H2 + (GR)-H, at time zero in direct ab initio MD calculations. Notation “r1” means distance of collisional hydrogen atom from hydrogen atom on H-(GR)-H (hydrogenated GR).

Figure 2.

(A) Graphene (GR) nanoflake used in the present study as a carbon material. GR04, GR07, GR14, and GR19 are composed of 4, 7, 14, and 19 benzene rings. The carbon atoms in the edge region are terminated by hydrogen atoms. (B) Initial geometry configuration in hydrogen abstraction reaction, H + H-(GR)-H → H2 + (GR)-H, at time zero in direct ab initio MD calculations. Notation “r1” means distance of collisional hydrogen atom from hydrogen atom on H-(GR)-H (hydrogenated GR).

Figure 3.

(A) Optimized structures of reaction system along the hydrogen abstraction reaction: hydrogenated GR at reactant state (RC: H-(GR)-H), van der Waals states (vdW-1 and 2), transition state (TS), and product state (PD: GR-H). The distances and bond lengths are in Å. The calculations were carried out at the CAM-B3LYP/ 6-311G(d,p) level.

Figure 3.

(A) Optimized structures of reaction system along the hydrogen abstraction reaction: hydrogenated GR at reactant state (RC: H-(GR)-H), van der Waals states (vdW-1 and 2), transition state (TS), and product state (PD: GR-H). The distances and bond lengths are in Å. The calculations were carried out at the CAM-B3LYP/ 6-311G(d,p) level.

Figure 4.

(A) Energy diagram of reaction system along the hydrogen abstraction reaction: hydrogenated GR14 at reactant state (RC: H-(GR)-H), van der Waals states (vdW-1 and 2), transition state (TS), and product state (PD: GR-H). The distances and bond lengths are in Å. The calculations were carried out at the CAM-B3LYP/ 6-311G(d,p) level.

Figure 4.

(A) Energy diagram of reaction system along the hydrogen abstraction reaction: hydrogenated GR14 at reactant state (RC: H-(GR)-H), van der Waals states (vdW-1 and 2), transition state (TS), and product state (PD: GR-H). The distances and bond lengths are in Å. The calculations were carried out at the CAM-B3LYP/ 6-311G(d,p) level.

Figure 5.

Time evolution of snapshots of reaction system for hydrogen abstraction reaction, H + H-(GR)-H → H2 + GR-H. Direct AIMD calculation were performed at the CAM-B3LYP/6-31G(d) level. The CAM-B3LYP/6-31G(d)-optimized geometry of H-(GR)-H was used as the initial geometry at time zero. The distances and bond lengths are in Å. GR04 was used.

Figure 5.

Time evolution of snapshots of reaction system for hydrogen abstraction reaction, H + H-(GR)-H → H2 + GR-H. Direct AIMD calculation were performed at the CAM-B3LYP/6-31G(d) level. The CAM-B3LYP/6-31G(d)-optimized geometry of H-(GR)-H was used as the initial geometry at time zero. The distances and bond lengths are in Å. GR04 was used.

Figure 6.

Time evolution of (A) potential energy and (B) interatomic distances of reaction system (r1 and r2). Direct AIMD calculation were performed at the CAM-B3LYP/6-31G(d) level. The CAM-B3LYP/6-31G(d)-optimized geometry of H-(GR)-H was used as the initial geometries of H-(GR)-H at time zero.

Figure 6.

Time evolution of (A) potential energy and (B) interatomic distances of reaction system (r1 and r2). Direct AIMD calculation were performed at the CAM-B3LYP/6-31G(d) level. The CAM-B3LYP/6-31G(d)-optimized geometry of H-(GR)-H was used as the initial geometries of H-(GR)-H at time zero.

Figure 7.

Distribution of translational energy of product H2 (Etr) formed by the H-abstraction reaction for H + H-(GR)-H → H2 + (GR)-H. Direct AIMD calculation were performed at the CAM-B3LYP/6-31G(d) level.

Figure 7.

Distribution of translational energy of product H2 (Etr) formed by the H-abstraction reaction for H + H-(GR)-H → H2 + (GR)-H. Direct AIMD calculation were performed at the CAM-B3LYP/6-31G(d) level.

Figure 8.

Energy diagram for the hydrogen addition reaction: GR + H at reactant state (RC), and transition state (TS), and product state (PD: GR-H). The relative energies and distances are in kcal/mol and Å, respectively. The calculations were carried out at the CAM-B3LYP/6-311G(d,p) level. The values obtained by APFD/6-311G(d,p) level are given in parenthesis. GR19 was used.

Figure 8.

Energy diagram for the hydrogen addition reaction: GR + H at reactant state (RC), and transition state (TS), and product state (PD: GR-H). The relative energies and distances are in kcal/mol and Å, respectively. The calculations were carried out at the CAM-B3LYP/6-311G(d,p) level. The values obtained by APFD/6-311G(d,p) level are given in parenthesis. GR19 was used.

Figure 9.

Schematic illustration of H2 storage/release device proposed in this study.

Figure 9.

Schematic illustration of H2 storage/release device proposed in this study.

Table 1.

Activation energies for the hydrogen addition reaction (Ea in kcal/mol), GR(n) + H → GR(n)-H, calculated at the CAM-B3LYP or APFD/6-311G(d,p) levels.

Table 1.

Activation energies for the hydrogen addition reaction (Ea in kcal/mol), GR(n) + H → GR(n)-H, calculated at the CAM-B3LYP or APFD/6-311G(d,p) levels.

| n |

CAM-B3LYP/6-311G(d,p) |

APFD/6-311G(d,p) |

| 4 |

6.8 |

5.7 |

| 7 |

6.6 |

5.6 |

| 14 |

5.6 |

4.9 |

| 19 |

6.2 |

5.3 |