1. Introduction

Potato (

Solanum tuberosum L.) is a crop plant that, alongside wheat, rice, and maize, significantly contributes to the world's food supply [

1]. Seed material is a fundamental element in plant production. Its high quality is one of the key factors in achieving high and good-quality potato yields [

2]. Therefore, its preparation, including enhancement before planting, is crucial. Traditional methods of preparing seed material include techniques such as sorting and fractionation of tubers [

3], stimulation or chitting [

4], treating them against diseases and pests [

5,

6], and various chemical and physical treatments. The aim of enhancing the material is to improve its energy and germination vigor and to reduce variability in physical, physiological, and morphological traits [

7]. Thanks to these fairly complex technologies, better plant growth and development are noticeable even in the next generation [

8].

Chemical seed treatment of potato tubers involves subjecting them to the action of chemical agents, called seed treatments, in the form of dust or by soaking them in a solution of these agents [

9]. Dry dusting of tubers is the oldest and cheapest method of tuber protection, involving applying a chemical substance in powder form to the surface of seed potatoes. This is most commonly done in stationary devices, where the appropriate dose of the substance is sprinkled onto a measured portion of seed potatoes and then thoroughly mixed. However, a drawback of this method is its low effectiveness due to poor coverage of the potato surface with the treatment. Wet seed treatment in the form of foam is a safer method that limits the amount of treatment used but requires the presence of a specialized seed treater located on a planter [

10]. The foam substance is dosed into the hopper, where each seed potato is covered with a layer of foamy treatment. An advantage of this method is the minimal amount of active substance used. Additionally, its good adhesion prevents active substance loss, and the surrounding environment is not exposed to contact with it [

11]. Another important parameter in this application method is the amount of treatment applied to the potato surface; too little may not provide sufficient potato protection, while too much may delay or even prevent emergence.

As seed treatments, plant biostimulants or growth bioregulators can be used. Biostimulants are products that improve plant growth or plant quality by enhancing (a) nutrient use efficiency, (b) tolerance to abiotic stresses, (c) qualitative traits, or (d) nutrient availability in the soil or rhizosphere. They are regulated by the European Union regulation on fertilizing products [

12]. According to this regulation, the effects declared by the manufacturer must be relevant for the plants listed on the label. The literal text reads: "A plant biostimulant must elicit the effects claimed on the label for the plants specified therein" [

13,

14]. The definition of plant biostimulants is based on statements [

15,

16], indicating that it is the product's function, rather than its composition, that defines it as a biostimulant. Therefore, demonstrating that a product is indeed a biostimulant, acting in good faith, depends on proving its efficacy. However, this should not be confused with providing a specific level of effectiveness. Under no circumstances should the introduction of a biostimulant to the EU market be considered a guarantee of effectiveness under all conditions, as many factors can influence the performance of a biostimulant in the field.

One of the biostimulants recommended for treating potato seed tubers is Supporter. This biostimulant is an agricultural product designed to support plant growth and development and increase their resistance to environmental stresses [

17]. It typically contains a mixture of active ingredients such as amino acids, vitamins, micronutrients, and metabolism-stimulating substances. The advantages of this biostimulant include enhancing plant resistance to diseases, pests, and environmental stress, thereby contributing to better yields. Regular use of the biostimulant can improve crop quality by increasing nutrient content and substances affecting aroma and taste [

17,

18]. Another advantage is the increased tolerance to extreme conditions. Plants treated with the biostimulant may be more resistant to adverse environmental conditions such as drought, high temperatures, or soil salinity. Additionally, its liquid form facilitates application through spraying or watering. Therefore, the aim of the research was to evaluate the impact of the biostimulant Supporter on the overall yield and commercial yield of potato tubers and their structure. This can be justified from several perspectives, such as:

The need to increase the efficiency of plant production, as modern agriculture imposes increasingly high demands on productivity and production quality. Research into new technologies, such as the use of plant biostimulants, aims to find ways to improve crop cultivation efficiency and increase yields.

Sustainable agricultural development: Biostimulants, such as Supporter, may contribute to more sustainable agricultural development by reducing the use of chemical substances potentially harmful to the environment and decreasing dependence on chemical pesticides and fertilizers.

Improving plant resistance: Research on the effect of the Supporter preparation on plant growth and development can provide information on its ability to increase plant resistance to environmental stresses such as drought, diseases, or pests.

In recent years, there has been increased interest in research on plant biostimulants, but studies on the Supporter product are seldom undertaken. Therefore, the conducted research aims to fill this gap in knowledge about biostimulants.

Therefore, an alternative research hypothesis was proposed in relation to the null hypothesis:

Alternative hypothesis (H1): The use of the biostimulant Supporter significantly increases potato tuber yield and improves the quality of yields by increasing the proportion of commercial tubers in the yield and increasing plant tolerance to environmental stresses.

Null hypothesis (H0): The use of the biostimulant Supporter has no significant effect on potato tuber yield and its structure.

3. Results

3.1. Total Tuber Yield

The average total tuber yield in the experiment was 40.35 t∙ha

−1 (

Table 6). Cultivation technologies significantly modified the value of this trait. The use of the Supporter product before potato planting resulted in a significant increase in tuber yield compared to traditional technology, on average by 13.3%. The most productive variety was ‘Lilly’ with an average yield of 47.95 t∙ha

−1, while the least productive was the 'Innovator' variety with an average yield of 29.93 t∙ha

−1. The varieties ‘Lady Claire’ and ‘Verdi’ proved to be homogeneous in terms of this trait (

Table 6).

Meteorological conditions during the study years significantly influenced the total tuber yield. The lowest yields were recorded in the dry 2015, while the highest were in the thermally and precipitationally optimal 2016, with 2017 being homogeneous in this regard (

Table 6).

Interaction between technology x variety and variety x year was also observed. Among the tested varieties, ‘Lilly’ responded best to the technology using the biostimulant Supporter. In the dry 2015, the highest yield was obtained by the ‘Lilly’ variety, while in the thermally and humidity optimal year, the ‘Lady Claire’ variety had the highest yield (

Table 6).

Geographical location, regardless of experimental factors, had a significant impact on the total tuber yield. The highest value of this trait was found in Głubczyce, located in southern Poland (47.94 t∙ha−1), while the lowest was in Barankowo, located in the northeastern part of the country (29.93 t∙ha−1).

The interaction between research location and cultivation technology also proved significant. The highest positive effect of using cultivation technology with the Supporter biostimulant was noted in Głubczyce, where the difference between the two technologies was 7.05 t∙ha

−1, resulting in a 15.9% increase in yield compared to traditional technology. Meanwhile, in Barankowo, where the yield levels were the lowest among all experimental locations, the difference between cultivation technologies was 6.88 t∙ha

−1, representing a 26.0% increase in yield compared to traditional technology without pre-planting treatments. In Kędrzyno and Ryn, the yield increase under the influence of the Supporter biostimulant was homogeneous, constituting 7.9% and 7.6%, respectively, compared to traditional technology (

Table 7). Thus, the obtained results suggest that in some locations, the technology with Supporter support yields better results on average than traditional technology.

3.2. The Structure of Tuber Yield

The structure of tuber yield depending on all experimental factors is presented in

Table 8.

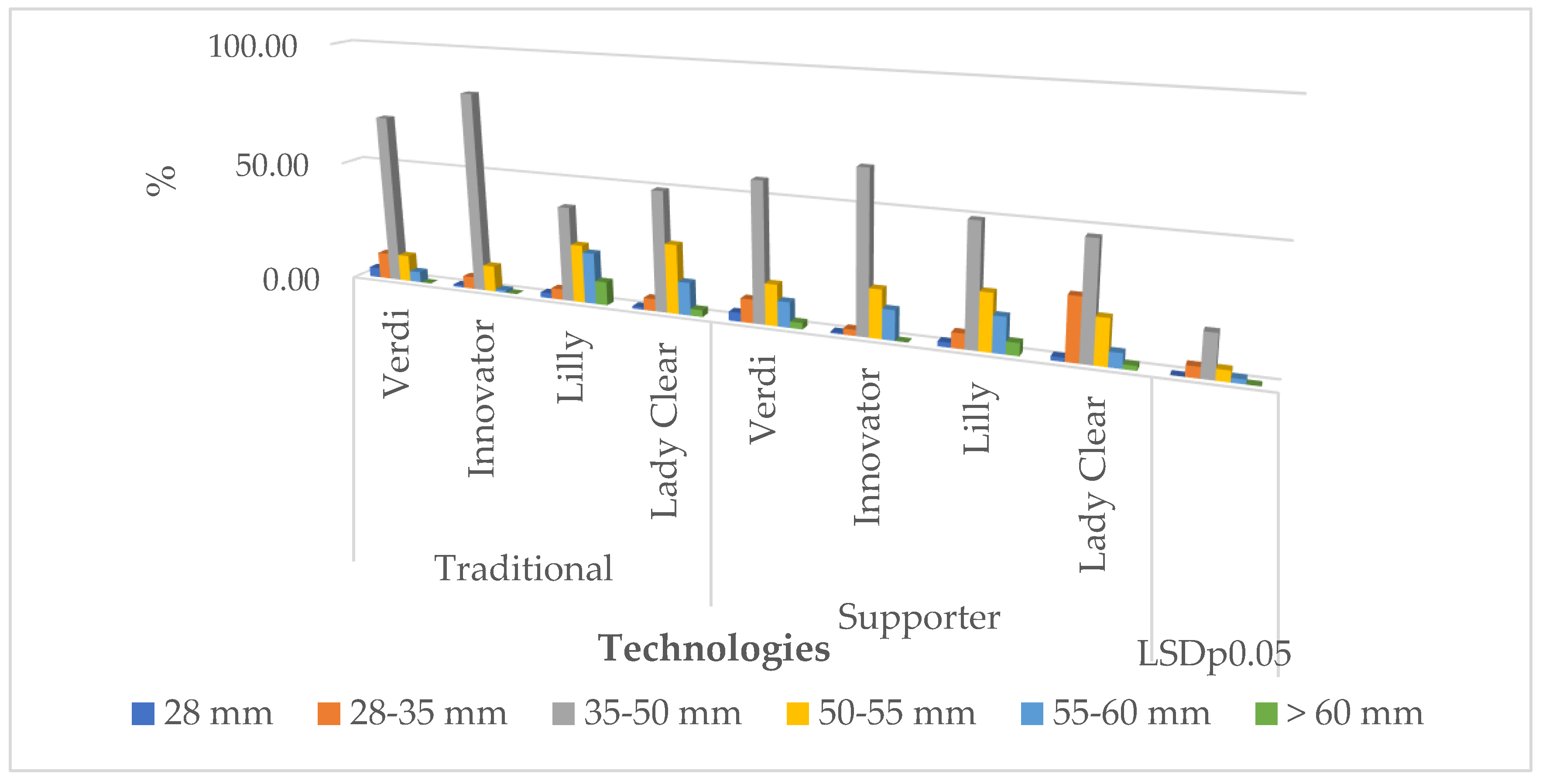

The proportion of individual tuber fractions in the total potato yield varied depending on the cultivation technology, variety, location, and harvest year. Among the individual fractions, only those with transverse diameters of 28–35, 50–55, 55–60, and >60 mm showed a different response to cultivation technologies. Potato plants produced a greater mass of tubers with calibers of 28–35 and 50-55 mm but a smaller mass of larger-sized tubers (55-60 and >60 mm in diameter) under the technology using the Supporter biostimulator (

Table 8).

Differences in the proportion of individual tuber fractions were also significant among the tested potato varieties. The 'Verdi' variety seemed to produce a greater mass of tubers with diameters <28 and 35-50 mm compared to other varieties. In contrast, the 'Lilly' variety exhibited the highest proportion of tubers with a diameter of 50-55 mm, while the 'Lady Claire' variety produced the largest mass of the largest tubers in the yield, with calibers of 55-60 and >60 mm. The 'Innovator' variety, however, showed homogeneity compared to the 'Verdi' variety in the production of medium-sized tubers, with a transverse diameter of 35-50 mm (

Table 8).

The location of the experiments also significantly influenced the structure of the potato tuber yield. The greatest small-sized tubers were observed in Kędrzyno, located in the northwest of Poland, on soil of IV soil evaluation class, while the largest proportion of large tubers, with diameters of 50-60 and >60 mm, was recorded in Głubczyce, in the south of the country, on soils of I and II evaluation class (

Table 8).

Meteorological conditions during the study years significantly modified the caliber of tubers with diameters of 28-35, 35-50, 50-55, 55-60, and >60 mm. A significantly higher proportion of tubers with calibers of 28-35 and 35-50 mm was observed in the dry year of 2015 than in the other years. Conversely, a significantly higher proportion of large tubers, with calibers of 50-55, 55-60, and >60 mm, was noted in years with optimal thermal-humidity conditions. In 2015, tubers with a diameter greater than 60 mm were significantly less numerous than in 2016 and 2017 (

Table 8).

Figure 3 illustrates the response of potato varieties to cultivation technology in terms of the proportion of mass of tubers of individual size fractions. The ‘Verdi’ variety responded by increasing the proportion of mass of large tubers with diameters of 50-55 and 55-60 mm in the total yield when using the technology with the Supporter biostimulator. The ‘Innovator’ variety, on the other hand, significantly responded by reducing the proportion of mass of tubers with diameters of 35-50 mm and 55-60 mm to this technology. The ‘Lilly’ variety responded to the technology with the use of the Supporter biostimulator by significantly increasing the proportion of mass of tubers with diameters of 35-50 mm and decreasing the proportion of mass of tubers with diameters of 55-60 mm. The ‘Lady Claire’ variety, in turn, responded by a significant increase in the mass of tubers with diameters of 28-35 mm and a simultaneous significant decrease in the proportion of tubers with calibers of 50-55 and 55-60 mm (

Figure 3).

There was no interaction observed between locations and varieties, nor between locations and cultivation technologies. However, overall, these studies allow for an analysis of the influence of various factors on the yield of potatoes with different tuber sizes, which can be helpful in optimizing cultivation processes and selecting the best agricultural practices.

3.3. The Share of Marketable Tubers

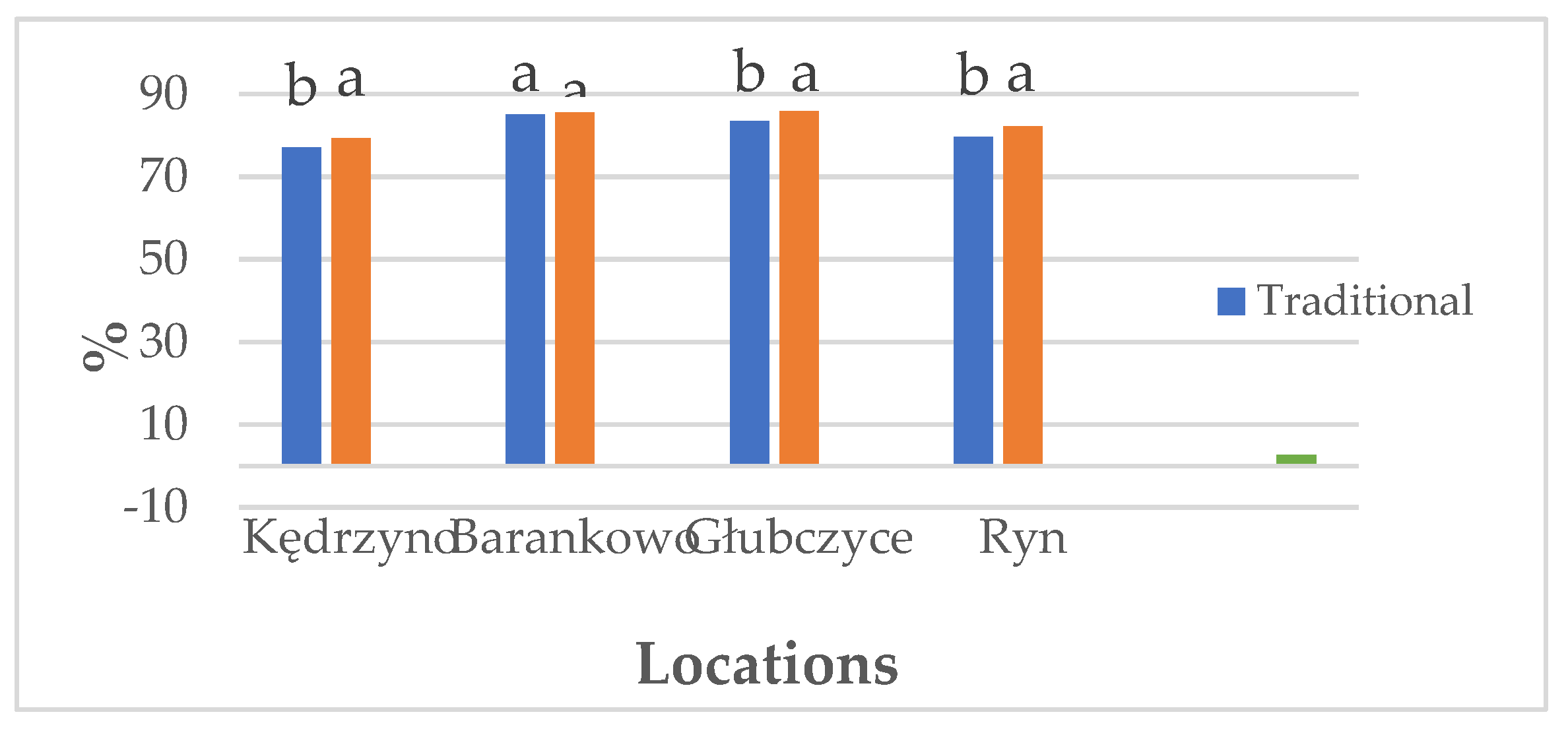

The impact of experimental factors on the share of marketable tubers is presented in

Figure 4 and

Table 9. Tubers suitable for the market, without damage or greening, accounted for an average of 72.34%. Cultivation technologies or years did not significantly differentiate the share of marketable tuber mass in the overall yield. However, the factor significantly modifying this characteristic was the genetic traits of the tested varieties and their interaction with cultivation technologies and years of study. The variety with the lowest share of marketable tubers was ‘Verdi’, while ‘Lady Claire’ had the highest share of mass of these tubers, with ‘Lilly’ and 'Innovator' being homogeneous in terms of this characteristic. The tested varieties showed varied reactions to the applied cultivation technologies. Both traditional and cultivation technologies using the biostimulator Supporter showed the lowest share of marketable tubers with the ‘Verdi’ variety. The tested varieties exhibited varied reactions to the meteorological conditions in the years of study. In 2015 and 2017, the variety ‘Verdi’ had the lowest share of marketable tubers in the yield, while in 2016, it was the ‘Innovator’ variety (

Table 9). On the other hand, the highest participation of marketable tubers in the yield, in the dry year of 2015, was observed with the ‘Innovator’ variety, while in the remaining years, it was the ‘Lady Claire’ variety. The ‘Lilly’ and ‘Lady Claire’ varieties were homogeneous in terms of this characteristic (

Table 9).

It was also observed that there was an interaction between the research locations and cultivation technologies. In three locations: Kędrzyno, Głubczyce, and Ryn, the cultivation technology using the biostimulator Supporter showed a significant increase in the share of marketable tuber mass compared to traditional cultivation technology. In Barankowo, however, a positive trend towards increasing the share of marketable tubers was noted with the Supporter technology (

Figure 4).

3.4. Yield of Marketable Tubers

The yield of marketable tubers was influenced by all experimental factors, but most significantly by the applied cultivation technologies (

Table 10). Thanks to the use of the biostimulator Supporter, the marketable yield increased by 20.2% compared to traditional technology. The highest marketable yield was obtained by the 'Lady Claire' variety, while the 'Lilly' variety was homogeneous in terms of this characteristic, and the least productive was the 'Innovator' variety. The highest yield of marketable tubers was achieved in the optimal thermohydrometric year of 2016; the year 2017 was homogeneous compared to 2016, while the lowest yield was obtained in the dry year of 2015 (

Table 10).

The varieties ‘Verdi’ and ‘Innovator’ showed different profitability over the years, with some improvement noted in 2017. The ‘Lilly’ variety consistently exhibited high yields throughout all years, regardless of the cultivation technology. The ‘Lady Claire’ variety showed relatively stable yields over the years, with only minor fluctuations.

Significant statistical differences were found in yield between varieties, cultivation technologies, locations, and years. In the case of double interactions, most of these differences were statistically significant. However, triple interactions between technologies, varieties, and years could not be statistically proven, suggesting that the observed variations likely fall within the expected range of natural variability. Therefore, the choice between traditional cultivation methods and those supported by Supporter may depend on factors other than yield, such as profitability, environmental impact, or labor requirements.

The location of the experiment was a significantly influencing factor on marketable yield. It was highest in the Ryn locality (37.21 t∙ha

−1), in the northeast corner of Poland, on proper brown soils, while the lowest yield levels were found in the Barankowo locality (22.28 t∙ha

−1), where potatoes were grown on the weakest soils, classified as class IV evaluation (

Table 11). Additionally, for the Kędrzyno and Barankowo as well as Głubczyce and Ryn localities, the marketable yield was homogeneous (

Table 11). The increase in marketable yield after using the growth modulator Supporter was highest in the Barankowo locality, as it amounted to as much as 27.8% compared to traditional technology, while it was lowest in the Ryn locality (increase in marketable yield by 10.8%); with a homogeneous effect observed in the Kędrzyno locality (increase in marketable yield by 11.1% compared to traditional technology). However, no interaction was found between cultivation technologies and experimental locations.

3.5. Variability of Tuber Yield and Its Characteristics

Table 12 provides descriptive statistics for eight variables, including the dependent variable (y) and 8 independent variables (x).

The average values for each variable differ significantly. For example, the mean total tuber yield (y1) is 40.34, while the average shares of tuber mass at different diameters (x2-x6) are significantly smaller. The standard deviation is substantial for most variables, indicating that the data are widely dispersed around the mean. For instance, the standard deviation for total tuber yield (y1) is 10.44. Other variables, such as the shares of tuber mass at different diameters and the commercial yield of tubers, also exhibit varied levels of means, standard deviations, and distributions. Standard errors, on the other hand, are measures of uncertainty in statistical estimates. The larger the standard error, the greater the uncertainty in the estimates. These values are calculated for each variable and can be used to determine the confidence in the estimates. Kurtosis and skewness provide information about the shape and distribution of the data. Positive kurtosis suggests a more peaked distribution, while negative kurtosis indicates a flatter distribution. Skewness measures the asymmetry of the distribution around its mean value. The coefficient of variation (CV), expressed as a percentage, informs us about the degree of variability in the data relative to their mean value. CV values above 100% indicate a high degree of variability.

Overall, these statistics allow for a better understanding of the dataset characteristics, which can be useful during analysis and interpretation of study results.

Skewness and kurtosis are measures of data distribution shape. These values provide information about the asymmetry and "weakness" of the distribution. Most evaluated variables exhibit some skewness and kurtosis, suggesting that the distributions may be somewhat asymmetrical and may contain outliers.

The range for each variable shows the differences between the maximum and minimum values. The range for total tuber yield (y1) is 47.3, indicating significant variability in tuber mass.

Minimum and maximum values provide information about the range of data. For example, the minimum value of total tuber yield is 18.06, and the maximum value is 65.36.

The coefficient of variation (CV) is used to compare the degree of variability between different sets of data. For individual features in the table, the coefficient of variation for each feature can help understand which of these features has relatively greater variability compared to other features. A high coefficient of variation (e.g., above 50%) indicates large fluctuations around the mean, meaning that the data are highly diverse and may be less stable or less certain.

Conversely, a low coefficient of variation (e.g., below 25%) indicates less variability in the data, suggesting that the data are more stable and less diverse around the mean. Therefore, this coefficient provides information about the degree of variability for each feature and is used to compare data stability between different variables. The higher the coefficient, the greater the variability, and the lower it is, the less variability there is. Therefore,

Figure 3 provides comprehensive information about the data distribution for dependent and independent variables. Analyzing this data can help understand the dataset characteristics and make decisions in statistical analysis.

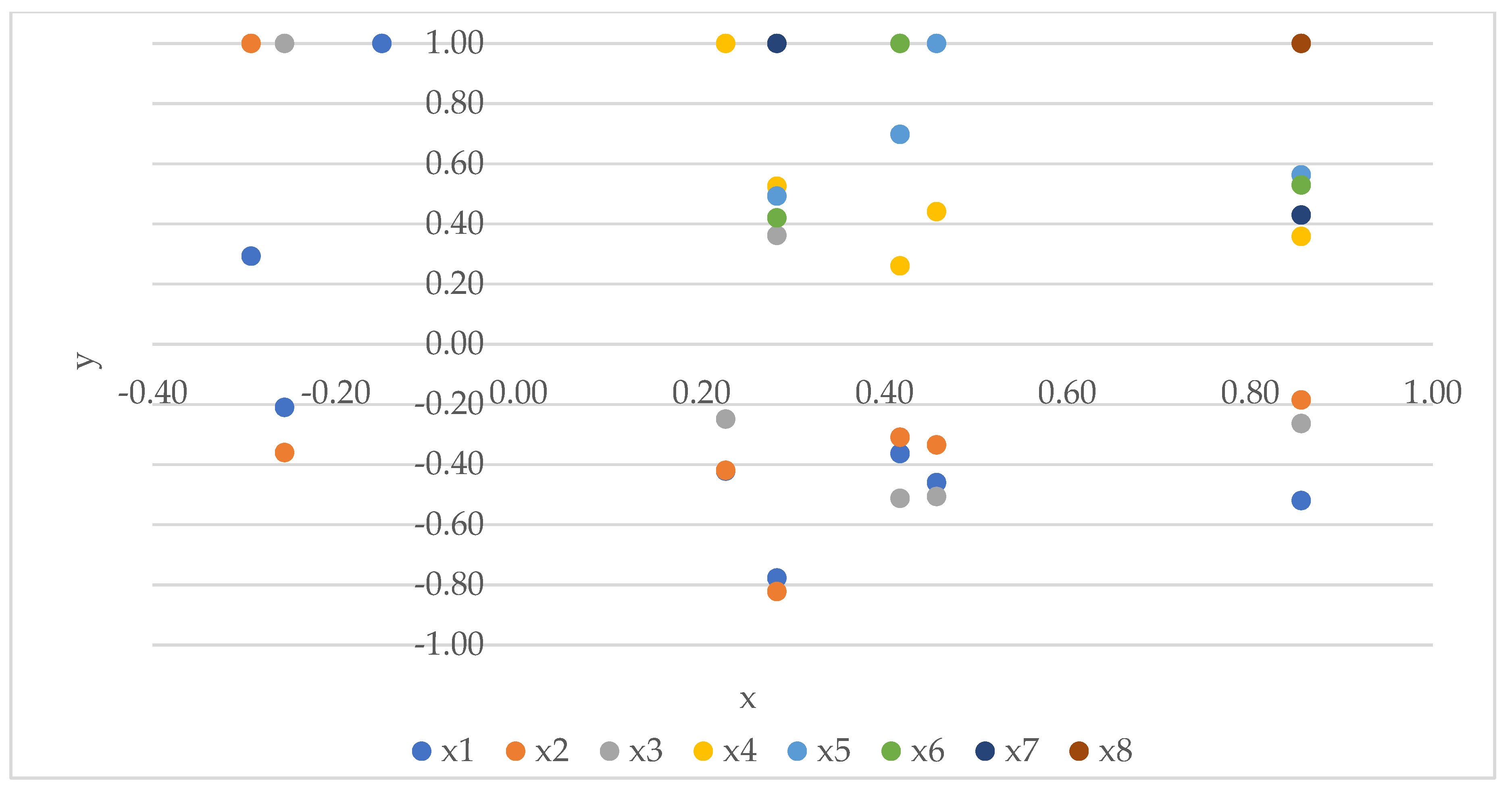

The values of simple correlations between variables are presented in

Figure 5.

Figure 5 depicts Pearson correlation coefficients between the dependent variable (y) and the independent variables (x). Coefficients close to 1 indicate a strong positive relationship between variables. For example, the correlation coefficients between y1 (total tuber yield) and x1 (commercial yield) and the tuber mass >60 mm diameter are relatively high (0.86 and 0.45, respectively), suggesting a strong positive relationship between these variables. Coefficients close to -1 indicate a strong negative relationship between variables. Correlation coefficients close to zero suggest little or very weak linear relationship between variables.

The

Figure 5. shows Pearson's simple correlation coefficients between the dependent variable (y1), representing the total tuber yield, and the independent variables (x1 - x8), representing different elements of yield related to tuber size. The correlation coefficient between y1 (total tuber yield) and x1 (share of tubers <28 mm diameter) was r = -0.15, indicating a weak negative correlation. The correlation coefficient between y1 and x2 (share of tubers 28-35 mm diameter) was -0.29, also indicating a weak negative correlation between these variables. A moderately negative correlation (-0.26) was observed between y1 and x3 (share of tubers 35-50 mm diameter). The correlation coefficient between y1 and x4 (share of tubers 50-55 mm diameter) was positive (r = 0.23), though weak. A moderately strong positive correlation (r = 0.46) was observed between y1 and x5 (share of tubers 55-60 mm diameter). The simple correlation coefficients between total yield and the share of tuber mass >60 mm diameter and the commercial yield of tubers were r = 0.42 and r = 0.28, respectively. The strongest positive correlation was found between total yield and commercial yield of tubers, with a correlation coefficient of r = 0.86.

4. Discussion

4.1. The Impact of Cultivation Techniques on Tuber Yield and Its Structure

Biostimulants are products of natural or synthetic origin containing substances that beneficially affect plant life processes. Seed treatment is considered a key technological procedure in potato cultivation aimed at improving natural soil and environmental conditions. The main advantages of this treatment include protection against early seedling decay caused by fungi, safeguarding tubers against damage and pest feeding, minimizing losses resulting from sudden outbreaks of diseases or pests, and reducing the need for chemical spraying in response to adverse weather conditions [

40,

41,

42,

43]. Studies conducted by Deising et al. [

41], Cielucha [

44], and Wharton et al. [

45] have shown that covering seed surfaces with chemical substances not only increases yield but also improves its quality parameters. Additionally, it aids in reducing losses caused by above-ground pests such as the Colorado potato beetle [

46].

According to the manufacturer [

18], the Supporter preparation works by stimulating the development of the plant's root system, which is particularly important in the early growth stages. The active substances in the preparation meet the nutritional requirements of soil microorganisms, leading to symbiosis in the root zone and intensifying plant growth. Increased potato yields after the application of pre-sowing seed treatments have been observed in both domestic and foreign studies. Treating potato seed tubers with biological preparations, as reported by Orzaliyeva et al. [

47], enhances yield by accelerating the pace of plant growth and development, increasing the assimilation surface area, and boosting resistance to potato diseases. Research by Pytlarz-Kozicka and Zagórski [

48] showed that the use of Trianum + Proradix WG and Proradix WG seed treatments increased both total and commercial potato yields compared to the control. Studies by Pytlarz-Kozicka and Słabicki [

49] evaluating the effects of Prestige 290 FS and Nuprid 600 FS seed treatments also demonstrated their positive impact on potato yields. Gazdanova et al. [

50] found that the use of biological preparations increased potato yields, with the highest yield rates observed in the variant with the Biobacterial BisolbiSan. Gleń-Karolczyk et al. [

6] also noted an increase in potato yields after treating tubers with Polyversum WP and Serenade ASO preparations, although it was not as effective as using growth stimulators such as Kelpak SL, Em Farma TM, soil conditioner UGMax, or Biogen Revital.

The alternative hypothesis was confirmed in the study, indicating that the use of the biostimulator Supporter led to a significant increase in tuber yield by increasing the proportion of large tubers in the yield.

4.2. The Impact of Varieties on Yield and Its Quantitative Characteristics

In the studies on the impact of varieties on yield and its quantitative characteristics, we conducted an analysis of the yield of several different potato varieties. We found significant differences in yield among different varieties of this species, regardless of cultivation techniques, years, or locations. Some varieties showed higher yields compared to others, which may be significant in terms of crop productivity.

Furthermore, analyzing quantitative characteristics of the yield, such as yield mass per unit area, structure of tuber mass of individual size fractions, or the proportion and yield of marketable tubers, we noticed that individual varieties exhibit different characteristics. Some varieties may have a higher yield mass per unit area, while others may appear more efficient in producing yield per plant. Similar observations regarding the yield of varieties have been noted in the works of other authors [

2,

3,

51,

52,

53].

The yield analysis also allowed us to assess how the tested potato varieties perform in different environmental conditions. Some varieties proved to be more resistant to, for example, drought stress or other adverse meteorological and environmental phenomena, which may affect their ability to maintain stable yield under various cultivation conditions.

Genetic studies suggest that the response of potato varieties to different types of light may be associated with genetic diversity [

54,

55]. Adjusting the ratio of active phytochrome to total phytochrome can significantly improve plant production and yield quality. Potato plants respond differently to different types of light - red light may lead to elongation of stems and production of small leaves, while blue light may result in shorter, sturdier plants with well-developed leaves. Adding green light to red and blue light may increase chlorophyll content, photosynthesis, and production of smaller-sized tubers. A high proportion of red and blue light may increase tuber production, while adding green light may favor the production of smaller-sized tubers [

55,

56,

57]. In summary, our research has shown the significant impact of potato varieties on yield and its quantitative characteristics. This allowed us to better understand which varieties may be more suitable in terms of yield performance under different cultivation conditions.

4.3. The Influence of Environmental Conditions on Yield and Its Structure

The threat to potato crops from excessive soil moisture during the growing season was lower than drought, which could significantly reduce the quantity and value of tuber yield. In four mesoregions of Poland, diverse thermo-hydric conditions affected potato yield, with the best conditions occurring in the south of Poland and the worst in the northeast of the country.

Research by Kalbarczyk & Kalbarczyk [

56] showed that optimal conditions for potato yield include average air temperature during May-September (15.2 °C), lower than average rainfall in May (45 mm), moderate rainfall in June (65 mm), and above-average rainfall in July (90 mm), August (75 mm), and September (60 mm). Rainfall deficits compared to potato requirements, especially in northwestern and central-western Poland, can lead to yield reduction.

Studies by Skowera et al. [

37,

57] also indicate spatial and temporal differences in rainfall deficits during potato cultivation in Poland. The highest risk of rainfall deficit, according to them, occurs in June, which is unfavorable for potatoes, as potato plants are then in the tuberization phase and forming new tubers.

Optimization of potato yield also depends on the amount of light. Adjusting the ratio of active phytochrome to total phytochrome can significantly improve plant production and yield quality. Research on the influence of different types of light on potatoes has shown that red light may lead to stem elongation and production of smaller leaves, while blue light may favor shorter, sturdier plants with well-developed leaves. Adding green light to red and blue light may increase chlorophyll content, photosynthesis, and production of smaller-sized tubers [

55].

Soil type and class also had a significant impact on yield and potato tuber structure. Here are several aspects that were considered:

Differences in soil chemical composition, such as nutrient content, pH, organic matter content, influenced the soil's ability to supply plants with necessary nutrients. Soils deficient in important chemical components for potatoes (e.g., in Barankowo and Kędrzyno) affected root development and nutrient uptake, which in turn influenced tuber size reduction and lower potato tuber yield compared to locations better supplied with these basic nutrients and higher organic matter content in the soil (e.g., Głubczyce).

Soil structure, including its granulation and porosity, also mattered for plant growth and development. Soils with good structure can provide better air and water permeability, leading to longer roots and better nutrient absorption. Conversely, soils with poor structure can limit root growth and contribute to uneven tuber development [

27,

32].

Soils with different water properties, such as water retention capacity and drainage, can affect water availability for plants. Excessive or insufficient water availability can negatively affect potato yield and tuber quality [

58,

59].

Soil temperature can also influence plant growth and development. Soils that warm poorly in spring, e.g., in Kędrzyno, can affect slower germination, weaker root growth, and potato tuber development [

57,

60].

Additionally, environmental conditions such as sunlight and atmospheric precipitation can also influence potato yield and tuber quality by regulating processes such as photosynthesis, transpiration, and nutrient translocation [

55,

57]. The best conditions were provided by locations in southern Poland (Głubczyce).

Soil structure, including its grain size distribution and porosity, also mattered for plant growth and development. Soils with good structure can provide better air and water permeability, leading to the formation of longer roots and improved absorption of nutrients. Conversely, soils with poor structure can limit root growth and contribute to uneven tuber development [

27,

32].

4.4. Local Conditions and Yield

In our research on the impact of location on potato yield and tuber structure, several significant aspects were observed, such as adaptation to local microclimates and soils, as well as variety adaptation to specific climatic and soil conditions. Growing locations can have a significant impact on potato yield, especially locations with different soil, climatic, and topographic conditions, which may favor different potato varieties or cultivation practices, ultimately leading to yield variation. Mocek [

27] suggest that local environmental factors, such as growing region, soil type, and organic carbon content, should be considered. Our research results confirm this. The best overall and commercial yield was obtained in Głubczyce on Class I or II of soil, while the lowest yield was observed in Barankowo on Podzolic soil in Class IV.

Analysis of potato tuber yield structure, such as size, shape, weight, and the proportion of tubers in different size fractions, revealed significant differences between locations. Soil and climatic conditions can influence tuber development, leading to variability in their structure in different localities and geographic locations. The greatest miniaturization of tubers was observed in Kędrzyn, located in northwestern Poland, where the soil was in Class IV. Conversely, the highest proportion of large-sized tubers (diameter of 50-60 mm and >60 mm) was observed in Głubczyce, in the southern part of the country, where soils were in Class I or II.

Environmental factors such as soil moisture, temperature, sunlight, precipitation, and topographic conditions have a significant impact on potato yield and tuber structure. Locations with similar climatic conditions may exhibit similar yield patterns and tuber structural characteristics. Similar observations regarding potato yield in different terrain conditions were made by Kalbarczyk & Kalbarczyk [

56] and Pszczółkowski et al. [

58].

Variety adaptation to local conditions: our research suggests that different potato varieties may exhibit varying degrees of adaptation to local conditions. Varieties better adapted to specific environmental conditions in a given location may achieve higher yields and exhibit more favorable tuber structural characteristics.

4.5. Phenotypic Variability of Yield and Its Traits

Yield variability is a characteristic marked by fluctuations in the quantity of produced yields across different years or locations. It is a natural process that can be influenced by various factors such as variability in climatic, meteorological, or microclimatic conditions. Additionally, yield variability may result from fluctuations in soil conditions, variability in cultivation practices, interactions with fertilizers, biostimulants, or pesticides. Yield variability significantly impacts the stability of agricultural production, farmers' profits, and supply in the agricultural market. Therefore, it is an important research area in agriculture, and farmers often undertake actions to mitigate the impact of yield variability through various management strategies.

In the conducted research, the total yield of potato tubers (y1) was characterized by a relatively low coefficient of variation (CV) of 25.9%. This means that the differences in tuber yield between different samples are relatively small compared to the average yield value. On the other hand, the shares of potato tuber mass in different size categories (x1-x6) exhibited varied variability, with the highest coefficient of variation observed for the share of tuber mass with a diameter above 60 mm (x6) - as much as 150.5%. This may suggest that the distribution of tuber masses in this category is more diverse than in other size categories. The share of commercial tuber mass (x7) was characterized by a relatively low coefficient of variation of 17.8%, suggesting that differences in the mass of commercial tubers are relatively small compared to their average value. The yield of commercial tubers (x8) exhibited moderate variability, with a coefficient of variation of 33.16%. This means that differences in the yield of commercial tubers between different samples are moderately large compared to the average yield value.

Overall, the analysis of the coefficient of variation allows us to understand how diverse the examined traits are and how significantly they differ between different samples. This can be useful when planning actions aimed at optimizing potato cultivation processes and improving yield performance.

4.6. Potato Variety Response to Growth Biostimulant

The response of potato varieties to growth biostimulants involves their reaction to the application of biostimulating substances, which can stimulate plant growth, development, and productivity. In the case of potatoes, the use of biostimulants may contribute to increased yields by regulating tuber yield structure, improving resistance to abiotic stressors (e.g., drought, salinity), and enhancing tolerance to diseases and pests. Biostimulants can influence various physiological processes in plants, such as photosynthesis, enzymatic activity, metabolism, and nutrient transport.

In the conducted research, the variety 'Lilly' exhibited the best response to the biostimulant Supporter in terms of both total and commercial yield. In agricultural practice, the application of biostimulants may involve applying these substances to the foliage, soil, or through the plant's root system. The effectiveness of biostimulants depends on the type of substance used and the environmental and genetic characteristics of the potato variety. The relationship between the share of commercial tubers in the total yield and cultivated varieties was also observed by Pytlarz-Kozicka and Zagórski. The highest share of large tubers in the total yield (>50 mm in diameter) was obtained by Baranowska et al. when applying the herbicide Avatar 293 ZC and the GreenOK Universal-PRO preparation, confirming the influence of genotype-environment interaction. This was also confirmed by other authors.

Research by Pardo-García et al. on the impact of biostimulants on secondary metabolism showed that those derived from agricultural by-products can improve plant productivity by activating the expression of key enzymes for phenylpropanoid synthesis, such as PAL. Studies by Ertani et al. [

66] demonstrated that biostimulants increased PAL enzyme activity in maize leaves. Biostimulants also enhance chlorophyll content, which is crucial for the photosynthesis process.

Therefore, the Supporter preparation acts as a biostimulant, improving the efficiency of nutrient utilization, tolerance to abiotic stresses, and plant quality characteristics. It complies with the regulations of the European fertilizer products legislation.

4.7. Impact of Biostimulants on Environmental Stress

Researchers Pytlarz-Kozicka and Zagórski found minimal rates of potato infection by diseases, ranging from 2.8% to 5.0% of plants affected by pathogens and from 2.5% to 4.9% by viruses. Noaema et al. demonstrated the role of the Supporter preparation in reducing the occurrence and severity of Rhizoctonia solani on potato tubers, irrespective of the variety. Additionally, they observed significantly higher yields of seed potatoes due to the reduction of this pathogen on potato plants. Gazdanova et al. [

50] showed that the use of biological preparations for seed treatment positively affects potato tuber sprouting, increasing it by 6.3% to 8.7% compared to the control variant. They also demonstrated their high efficacy against fungal potato pathogens such as Phytophthora infestans and Rhizoctonia solani, ranging from 37.5% to 100%, resulting in a significant increase in potato yield.

Treating potato seedlings with biological preparations by Novikova et al. resulted in nearly a twofold increase in yields compared to the control. Furthermore, during the flowering stage, the biological effectiveness of these preparations reached close to 90% under optimal conditions and 50-75% under conditions of hydrothermal drought.

In the conducted research, the use of the bioregulator Supporter resulted in an increase in total potato tuber yield by 13.3% and commercial yield by over 20%, attributed to the increased mass of tubers in the 50-60 mm and >60 mm size categories. Potato yield was largely determined by the interaction of experiment location and cultivation technology. According to Noaema et al., the biostimulant Supporter, when used at a lower concentration (half the recommended dose), significantly reduces the occurrence of rhizoctonia on potato tubers.

The use of biostimulants can have varied effects on environmental stresses, depending on specific conditions, the type of biostimulant used, and its composition. Some biostimulants may assist plants in better coping with environmental stress by stimulating their natural resistance to stress factors such as drought, soil salinity, or high temperatures. The alternative hypothesis was confirmed in the study, indicating that the use of the biostimulator Supporter led to a significant increase in tuber yield by increasing the enhancing plant tolerance to environmental stresses.

Research on the mechanisms of action of the biostimulant Supporter in the context of plant resistance may be crucial for agriculture, especially considering changing environmental conditions and increasing demands for sustainable food production.

4.8. Correlations between Yield and Its Component Traits

The conducted research confirmed the existence of various degrees of relationships between parameters related to potato tuber yield. Both positive and negative correlations were observed between different variables. A strong positive correlation (r = 0.86) was found between total tuber yield and commercial yield, suggesting that a higher overall yield translates into a greater proportion of tubers suitable for sale. On the other hand, a weak negative correlation between total yield and the proportion of smaller-sized tubers (e.g., <28 mm in diameter) indicates that a larger overall yield does not necessarily lead to a proportional increase in the share of the smallest tubers. Moderate correlations between different tuber fractions (e.g., from 28 to 60 mm) and total yield suggest some relationships between tuber size distribution and overall yield, although they are not as strong as the correlation between commercial yield and total tuber yield.

Analyzing these relationships is often presented as a complex and multidimensional problem. Studies on potato tuber yield consider many factors such as weather conditions, soil, cultivation methods, as well as tuber traits, leading to diverse correlations between individual parameters. The interaction between variety and environment has been identified as a significant factor influencing tuber yield variability and structure. It is also essential to consider tuber size distribution because a higher overall yield does not always translate into a greater proportion of tubers of desired sizes.

Recent research aims to identify factors influencing these relationships, such as plant genetics, environmental conditions, cultivation methods, and fertilization, to better understand and optimize processes related to potato tuber yield.

4.9. Towards the Future

This consideration provides fertile ground for research aimed at elucidating the complex relationship between biostimulants and agroecosystems, fostering the evolution of sustainable agriculture paradigms. It also underscores the potential of biostimulants in shaping agricultural practices and formulating agro-environmental policies. Key directions for future research include:

Integration of biostimulants into agricultural practices, such as the use of the Supporter biostimulant, heralds a new era for sustainable agriculture. Ongoing research aimed at elucidating the mechanisms of biostimulant action and their environmental interactions will facilitate further refinement.

Exploration of synergies between biostimulants and other sustainable agriculture methodologies, such as agroecology and precision farming, promises to optimize agricultural productivity while minimizing environmental impact. Standardization of biostimulant production and implementation, such as Supporter, is necessary to unlock their full potential and support transformations towards sustainable agriculture.

Prospects for research on growth stimulants and biostimulants in potato cultivation are promising and encompass several key areas, including:

Optimization of biostimulant composition and action: Further research is needed on the composition of biostimulants and their effects on plants to better understand which components are most effective in stimulating potato growth. These studies may lead to the development of more efficient biostimulant formulations tailored to different growing conditions.

Mechanisms of biostimulant action: Understanding the molecular and physiological mechanisms through which biostimulants influence plants, including growth processes, root development, photosynthesis, and stress resistance, is important. Such research can help identify specific metabolic pathways and genes responsible for plant responses to biostimulants.

Optimization of dosage and application: Studies on optimal biostimulant dosing and application methods are essential to ensure maximum efficacy of these products with minimal environmental impact and may help reduce production costs for farmers.

Field and long-term studies: Conducting field and long-term studies to assess the effectiveness of biostimulants in various potato growing conditions and their impact on yield, tuber quality, and plant health is important. Such research can provide practical guidance on the best practices for using biostimulants in real-world growing conditions.

Sustainable agriculture: Research on biostimulants can contribute to promoting sustainable agriculture by increasing plant productivity and resilience, reducing chemical inputs, and improving the efficiency of natural resource utilization.

As research progresses in these areas, further development and refinement of biostimulants can be expected, which may bring benefits to agriculture by increasing potato cultivation efficiency while simultaneously reducing negative environmental impact.

5. Conclusions

Conclusions and Future Directions Based on Conducted Research on the Impact of the Plant Bioregulator Supporter on Potato Yield and Quality:

Positive Impact of Supporter: It has been demonstrated that the plant bioregulator Supporter positively influences potato yield and the quantitative and qualitative characteristics of the obtained produce. Therefore, the application of Supporter may constitute an effective strategy for improving potato production efficiency, which is crucial for ensuring food security.

Enhanced Environmental Resilience: Plants treated with the biostimulant Supporter exhibited greater resistance to environmental stresses such as drought or high temperatures. Consequently, further research on the mechanisms of action of Supporter in the context of plant resilience may be important for agriculture.

Variability in Yield Patterns: Some of the studied varieties showed stable yield patterns (e.g., 'Lilly' and 'Lady Claire'), while others were more variable in their productivity, regardless of the analyzed experimental factors.

Influence of Cultivation Location: Crop location significantly impacts potato yield and tuber structure. Understanding these differences can aid in better adapting cultivation practices and selecting varieties to specific local conditions, potentially increasing potato cultivation efficiency.

Environmental Factors: Environmental factors during the study years resulted in differences in potato yield and tuber structure depending on soil type and meteorological conditions. Considering these differences is important when planning potato cultivation and making decisions regarding fertilization and plant care.

Correlations in Yield Parameters: Strong positive correlation (r = 0.86) between total tuber yield and commercial yield suggests that higher total yield translates into a greater commercial yield. However, weak negative correlation between total yield and the proportion of smaller tubers suggests that higher yield does not necessarily mean a proportional increase in the share of the smallest tubers. Relationships between tuber size distribution and total yield were confirmed, although not as strong as in the case of commercial yield.

Future Research Directions: Continued research on the impact of Supporter on potato yield in different environmental conditions and soil types is necessary to gain a more comprehensive understanding of its effects. Studies on optimizing doses and application methods of Supporter are also important, as they may contribute to even better results in potato production.

Towards Sustainable Agriculture: In the context of the growing need for sustainable agriculture, further research on the impact of Supporter on crop production efficiency can contribute to the development of more environmentally friendly and efficient cultivation practices, thus meeting the increasing food needs of society.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.B., B.S. and P.P.; methodology, P.B., P.P.; software, A.K.F.; validation, P.B., T.S.H., A.K.F.; formal analysis, A.K.F.; investigation, P.B.; resources, T.S.H., P.P., A.K.F.; data curation, A.K.F.; writing—original draft preparation, P.B., P.P., T.S.H., A.K.F.; writing—review and editing, B.S., P.B.; visualization, A.K.F., T.S.H.; supervision, B.S., P.P.; project administration, P.B.; funding acquisition, B.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Figure 2.

Planter with mounted dressing device; source: own.

Figure 2.

Planter with mounted dressing device; source: own.

Figure 3.

The influence of potato varieties and cultivation technology on the mass share of tubers with a diameter of <28 mm, 28-35 mm, 35-50 mm, 50-55 mm, 55-60 mm and > 60 mm.

Figure 3.

The influence of potato varieties and cultivation technology on the mass share of tubers with a diameter of <28 mm, 28-35 mm, 35-50 mm, 50-55 mm, 55-60 mm and > 60 mm.

Figure 4.

The influence of cultivation technology and locations on the percentage of the mass of commercial tubers.

Figure 4.

The influence of cultivation technology and locations on the percentage of the mass of commercial tubers.

Figure 5.

The Pearson correlation coefficients between the dependent variable (y) and the independent variables (x). y – total tuber yield; x1 – mass share of tubers with diameter <28 mm; x2 – mass share of tubers with a diameter of 28-35 mm; x3 – mass share of tubers with a diameter of 35-50 mm; x4 – mass share of tubers with a diameter of 50-55 mm; x5 – mass share of tubers with a diameter of 55-60 mm; x6 – mass share of tubers with a diameter >60 mm; x7 – share of the mass of commercial tubers; x8 – marketable yield of tubers.

Figure 5.

The Pearson correlation coefficients between the dependent variable (y) and the independent variables (x). y – total tuber yield; x1 – mass share of tubers with diameter <28 mm; x2 – mass share of tubers with a diameter of 28-35 mm; x3 – mass share of tubers with a diameter of 35-50 mm; x4 – mass share of tubers with a diameter of 50-55 mm; x5 – mass share of tubers with a diameter of 55-60 mm; x6 – mass share of tubers with a diameter >60 mm; x7 – share of the mass of commercial tubers; x8 – marketable yield of tubers.

Table 1.

Selected elements of potato cultivation in the technologies of potato production.

Table 1.

Selected elements of potato cultivation in the technologies of potato production.

| Specification* |

Technologies |

| Traditional |

With Supporter |

| Pre-planting treatments |

With out |

Supporter (300 ml + 30l water ·ha−1) |

| Fertilization |

Biennial compost (straw + red clover + hay) – 35 t·ha−1 + NPK 90-90-135 kg ha−1

|

Biennial compost (straw + red clover + hay) – 35 t·ha−1 + NPK 90-90-135 kg ha−1

|

| Weed control systems |

Afalon 450 SC − 2 l·ha−1

Fusilade Super 125 EC − 2 1·ha−1

|

Afalon 450 SC − 2 l·ha−1

Fusilade Forte 150 EC – 1.5 1·ha−1

|

| Potato beetle control |

Calypso 480 SC 0.1 1·ha−1 – 1 measure

Actara 25 WG 0.08 kg·ha−1 – 1 measure

Cyperkil Max 500 EC 0.05 1·ha−1 – 1 measure

Karate Zeon 050CS 0.1 l·ha−1 – 1 measure |

Calypso 480 SC 0.1 1·ha−1 – 1 measure

Actara 25 WG 0.08 kg·ha−1 – 1 measure

Cyperkil Max 500 EC 0.05 1·ha−1 – 1 measure

Karate Zeon 050CS 0.1 l·ha−1 – 1 measure |

| Potato blight control |

Pyton Consento 450 SC 2.0 l·ha−1 – 1 measure

Infinito 687.5 SC 1.6 l·ha−1 – 1 measure

Ridomil Gold MZ 67.8 WG 2.0 kg·ha−1 – 1 measure

Acrobat MZ 69 WG – 2.0 kg ha−1 – 1 measure |

Pyton Consento 450 SC 2.0 l·ha−1 – 1 measure

Infinito 687.5 SC 1.6 l·ha−1 – 1 measure

Ridomil Gold MZ 67.8 WG 2.0 kg·ha−1 – 1 measure

Acrobat MZ 69 WG – 2.0 kg ha−1 – 1 measure |

| Harvest |

Harvesting with an elevator digger at the time of technical ripeness of the tubers (99° in the BBCH scale) [Bleinholder i in. 2005] |

Harvesting with an elevator digger at the time of technical ripeness of the tubers (99° On the BBCH scale) [Bleinholder i in. 2005] |

Table 2.

Characteristics of the tested potato varieties.

Table 2.

Characteristics of the tested potato varieties.

| Varieties |

Breeder |

Peel color |

Flesh color |

Culinary type |

Starch content

(%) |

Yield of tubers

(t · ha−1) |

| Early varieties |

| ‘Innovator’ |

HZPC Holland, BV |

yellow |

creamy |

B |

14.8 |

44.2 |

| ‘Lilly’ |

Solana Polska |

yellow |

yellow |

BC |

14.0-14.5 |

40.0 |

| ‘Lady Claire’ |

HZPC Holland, BV |

yellow |

light yellow |

BC |

16.7 |

38.4 |

| Moderately variety |

| ‘Verdi’ |

Solana Polska |

yellow |

yellow |

BC |

19-20 |

36.4 |

Table 3.

Content of available forms of phosphorus, potassium, magnesium humus and soil reaction (2015-2017).

Table 3.

Content of available forms of phosphorus, potassium, magnesium humus and soil reaction (2015-2017).

| Lata |

Macroelements content [g · kg−1] |

pHKCL

|

Humus

[g·kg−1] |

| |

P2O5

|

K2O |

Mg |

| Kędrzyno |

| 2015 |

24.8 |

9.0 |

3.4 |

5.6 |

1.01 |

| 2016 |

18.8 |

18.0 |

3.9 |

6.0 |

1.06 |

| 2017 |

17.0 |

15.0 |

6.2 |

6.4 |

1.12 |

| Barankowo |

| 2015 |

31.9 |

14.8 |

3.3 |

5.8 |

1.2 |

| 2016 |

25.0 |

12.7 |

3.2 |

6.0 |

1.4 |

| 2017 |

30.4 |

12.4 |

2.9 |

5.9 |

1.3 |

| Ryn |

| 2015 |

14.5 |

16.0 |

3.6 |

6.1 |

1.1 |

| 2016 |

14.7 |

17.5 |

3.8 |

6.3 |

1.3 |

| 2017 |

15.0 |

19.0 |

4.0 |

6.4 |

1.4 |

| Głubczyce |

| 2015 |

27.8 |

22.6 |

11.8 |

6.6 |

1.8 |

| 2016 |

25.2 |

21.5 |

12.8 |

6.5 |

1.7 |

| 2017 |

21.8 |

19.1 |

12.0 |

6.4 |

1.6 |

Table 4.

Total rainfall and average air temperature in Barankowo, Gołubczyce, Kędrzyno and Ryn in the period May- September (2015-2017).

Table 4.

Total rainfall and average air temperature in Barankowo, Gołubczyce, Kędrzyno and Ryn in the period May- September (2015-2017).

| Locations |

Total rainfall [mm] |

| 2015 |

2016 |

2017 |

| Barankowo |

237.1 |

306.9 |

508.9 |

| Głubczyce |

218.4 |

472.3 |

465.9 |

| Kędrzyno |

383.9 |

476.1 |

712.8 |

| Ryn |

241.3 |

350.0 |

451.6 |

| Average air temperature [ °C] |

| Barankowo |

13.4 |

15.3 |

14.1 |

| Głubczyce |

15.9 |

15.7 |

15.2 |

| Kędrzyno |

12.2 |

14.9 |

14.0 |

| Ryn |

14.5 |

13.8 |

14.1 |

Table 5.

Sielianinov hydrothermal coefficients (2015-2017).

Table 5.

Sielianinov hydrothermal coefficients (2015-2017).

| Localities |

Month |

Years |

| 2015 |

2016 |

2017 |

| Barankowo |

April |

1.3 |

1.4 |

2.0 |

| May |

0.7 |

0.7 |

2.0 |

| June |

1.3 |

1.2 |

2.2 |

| July |

1.2 |

1.9 |

2.3 |

| August |

0.3 |

1.1 |

1.9 |

| September |

1.1 |

0.2 |

1.0 |

| Mean |

0.9 |

1.0 |

1.9 |

| Głubczyce |

April |

0.8 |

2.1 |

5.6 |

| May |

0.8 |

2.5 |

1.2 |

| June |

1.6 |

1.4 |

0.6 |

| July |

0.5 |

2.7 |

1.2 |

| August |

0.2 |

0.7 |

0.9 |

| September |

0.5 |

0.5 |

3.1 |

| Mean |

0.7 |

1.6 |

2.1 |

| Kędrzyno |

April |

1.1 |

1.2 |

4.1 |

| May |

1.9 |

1.6 |

1.0 |

| June |

2.3 |

1.6 |

3.5 |

| July |

3.6 |

3.0 |

3.2 |

| August |

0.3 |

1.5 |

2.9 |

| September |

2.3 |

0.8 |

2.2 |

| Mean |

1.9 |

1.6 |

2.8 |

| Ryn |

April |

0.8 |

1.7 |

3.6 |

| May |

2.7 |

1.1 |

0.5 |

| June |

0.4 |

0.9 |

1.1 |

| July |

1.0 |

2.4 |

2.4 |

| August |

0.4 |

1.5 |

1.0 |

| September |

0.3 |

0.3 |

2.7 |

| Mean |

0.9 |

1.3 |

1.8 |

Table 6.

The influence of cultivation technology, varieties and years on the total yield of potato tubers (t·ha−1) (average for location).

Table 6.

The influence of cultivation technology, varieties and years on the total yield of potato tubers (t·ha−1) (average for location).

| Varieties |

Technologies |

Mean |

| Traditional |

With Supporter |

| Years |

Mean |

Years |

Mean |

Years |

Mean |

| 2015 |

2016 |

2017 |

2015 |

2016 |

2017 |

2015 |

2016 |

2017 |

| ‘Verdi’ |

33.19a |

43.43a |

38.19a |

38.27ab |

31.64a |

51.64a |

40.63a |

41.30b |

32.42b |

47.54a |

39.41b |

39.79b |

| ‘Innovator’ |

20.84a |

30.15a |

28.48a |

26.49b |

36.24a |

27.95a |

35.93a |

33.37c |

28.54c |

29.05b |

32.21c |

29.93c |

| ‘Lilly’ |

47.48a |

41.87a |

43.92a |

44.42a |

60.52a |

48.28a |

45.62a |

51.47a |

54.00a |

45.08a |

44.77a |

47.95a |

| ‘Lady Claire’ |

32.47a |

48.64a |

45.26a |

42.12a |

31.26a |

51.12a |

53.59a |

45.32ab |

31.87b |

49.88a |

49.43a |

43.72b |

| Mean |

33.50a |

41.02a |

39.0a |

37.83b |

39.92a |

44.75a |

43.94a |

42.87a |

36.71b |

42.89a |

41.45a |

40.35 |

| LSDp0.05

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Technologies |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

2.22 |

| Varieties |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

4.44 |

| Years |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

3.33 |

| Tech. × varieties |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

8.88 |

| Varieties × years |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

13.32 |

Table 7.

Total yield of potato tubers depending on technology and location (t ha−1) (Mean for varieties and years).

Table 7.

Total yield of potato tubers depending on technology and location (t ha−1) (Mean for varieties and years).

| Locations |

Technologies |

Mean |

| Traditional |

With Supporter |

| Barankowo |

26.49b* |

33.37c |

29.93c |

| Głubczyce |

44.42a |

51.47a |

47.94a |

| Kędrzyno |

38.27a |

41.30b |

39.78b |

| Ryn |

42.12a |

45.32a |

43.72ab |

| LSDp0.05

|

8.88 |

4.44 |

| Mean |

37.83b |

42.87a |

40.34 |

| LSDp0.05

|

2.22 |

|

Table 8.

Share of potato tuber mass by diameter fractions (<28, 28-35, 35-50, 50-55, 55-60, and >60 mm) depending on cultivation technology, potato varieties, and harvest years (%) (Mean from locations).

Table 8.

Share of potato tuber mass by diameter fractions (<28, 28-35, 35-50, 50-55, 55-60, and >60 mm) depending on cultivation technology, potato varieties, and harvest years (%) (Mean from locations).

| Experimental factors |

Tuber diameter fractions (mm) |

| <28 |

28–35 |

35–50 |

50–55 |

55–60 |

>60 |

| Technologies |

Traditional |

2.07a* |

5.84b |

50.49a |

18.62b |

13.06a |

9.92a |

| With Supporter |

2.01a |

7.52a |

49.11a |

20.29a |

12.54b |

8.53b |

| LSD0.05 |

ns** |

0.75 |

2.73 |

0.65 |

0.37 |

0.22 |

| Varieties |

‘Verdi’ |

3.53a |

8.63a |

58.03a |

16.80c |

9.00d |

4.01c |

| ‘Innovator’ |

1.57b |

5.66bc |

56.39a |

19.55b |

10.61c |

6.22b |

| ‘Lilly’ |

1.97b |

5.25c |

50.85b |

21.24a |

14.41b |

6.28b |

| ‘Laidy Claire’ |

1.11bc |

7.13b |

33.98c |

20.19ab |

17.17a |

20.42a |

| LSD0.05 |

1.51 |

1.51 |

5.47 |

1.30 |

0.74 |

0.44 |

| Locations |

Barankowo |

3.50a |

8.70a |

56.54a |

17.14c |

8.84d |

5,28c |

| Głubczyce |

1.66b |

5.60c |

56.32a |

19.78c |

10.65c |

5.99c |

| Kędrzyno |

1.80b |

5.02d |

51.43b |

20.31a |

14.23b |

7.21b |

| Ryn |

1.19c |

7.40b |

34.90c |

20.56a |

17.48a |

18.47a |

| LSDp0.05 |

0.15 |

0.43 |

3.29 |

1.26 |

0.96 |

0.62 |

| Years |

2015 |

1.95a |

8.60a |

57.47a |

18.92b |

10.32b |

2.74c |

| 2016 |

1.97a |

5.70b |

44.96b |

18.23b |

15.43a |

13.71a |

| 2017 |

2.20a |

5.76b |

46.96b |

21.20a |

12.65b |

11.23b |

| LSD0.05 |

ns |

1.13 |

4.10 |

0.97 |

0.55 |

0.33 |

| Mean |

2.04 |

6.68 |

49.80 |

19.45 |

12.80 |

9.23 |

Table 9.

The impact of cultivation technology, varieties and years on the share of commercial tubers in the total yield (%) (Mean for locations).

Table 9.

The impact of cultivation technology, varieties and years on the share of commercial tubers in the total yield (%) (Mean for locations).

| Varieties |

Technologies |

Mean |

Mean |

| Traditional |

With Supporter |

| Years |

Mean |

Years |

Mean |

Years |

| 2015 |

2016 |

2017 |

2015 |

2016 |

2017 |

2015 |

2016 |

2017 |

| ‘Verdi’ |

60.95a |

69.51a |

54.14a |

61.53b |

61.42a |

72.89a |

55.63a |

63.31b |

61.19b |

71.20a |

54.89b |

62.42b |

| ‘Innovator’ |

83.82a |

61.40a |

76.22a |

73.81a |

87.20a |

61.93a |

73.05a |

74.06a |

85.51a |

61.67b |

74.64a |

73.94a |

| ‘Lilly’ |

74.92a |

75.93a |

73.81a |

74.89a |

77.97a |

64.35a |

83.02a |

75.11a |

76.45a |

70.14a |

78.42a |

75.00a |

| ‘Lady Claire’ |

76.26a |

84.21a |

73.91a |

78.13a |

61.50a |

86.36a |

85.74a |

77.87a |

68.88ab |

85.29a |

79.83a |

78.00a |

| Mean |

73.99a |

72.76a |

69.52a |

72.09a |

72.02a |

71.38a |

74.36a |

72.59a |

73.01a |

72.07a |

71.94a |

72.34 |

| LSD p0.05

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Technologies |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

ns** |

| Varieties |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

7.96 |

| Years |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

ns |

| Tech. x varieties |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

15.92 |

| Varieties x years |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

23.87 |

Table 10.

The impact of cultivation technology, varieties and years on marketable yield (t·ha−1) (Mean for Locations).

Table 10.

The impact of cultivation technology, varieties and years on marketable yield (t·ha−1) (Mean for Locations).

| Varieties |

Technologies |

Mean |

Mean |

| Traditional |

With Supporter |

Years |

| Years |

Mean |

Years |

Mean |

| 2015 |

2016 |

2017 |

2015 |

2016 |

2017 |

2015 |

2016 |

2017 |

| ‘Verdi’ |

20.41a |

30.19a |

20.72a |

23.77b |

19.39a |

37.60a |

22.52a |

26.50b |

19.90c |

33.90ab |

21.62 |

25.14b |

| ‘Innovator’ |

17.51a |

18.89a |

21.89a |

19.43bc |

31.55a |

17.69a |

26.17a |

25.14b |

24.53bc |

18.29c |

24.03b |

22.28bc |

| ‘Lilly’ |

36.12a |

31.17a |

32.45a |

33.25a |

47.24a |

30.94a |

37.95a |

38.71a |

41.68a |

31.06b |

35.20a |

35.98a |

| ‘Lady Claire’ |

24.81a |

40.94a |

33.49a |

33.08a |

33.92a |

44.14a |

45.97a |

41.34a |

29.37b |

42.54a |

39.73a |

37.21a |

| Mean |

24.71b |

30.30a |

27.14a |

27.38b |

33.03a |

32.59a |

33.15a |

32.92a |

28.87b |

31.45a |

30.15a |

30.15 |

| LSDp0.05

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Technologies |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1.66 |

| Varieties |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

3.32 |

| Years |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

2.49 |

| Tech. x Var. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

6.64 |

| Tech. x Years |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

4.98 |

| Var. x years |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

9.96 |

Table 11.

The impact of location and cultivation technology on marketable yield (t.ha−1) (Mean for varieties and years).

Table 11.

The impact of location and cultivation technology on marketable yield (t.ha−1) (Mean for varieties and years).

| Locations |

Technologies |

Mean |

| Traditional |

With Supporter |

| Kędrzyno |

29.60a* |

32.88a |

31.24b |

| Barankowo |

22.32a |

28.53a |

25.42bc |

| Głubczyce |

36.90a |

44.19a |

40.54a |

| Ryn |

35.08a |

38.87a |

36.97a |

| LSDp0.05

|

ns** |

8.94 |

| Mean |

30.97b |

36.11a |

33.54 |

| LSDp0.05

|

4.47 |

|

Table 12.

Descriptive statistics of dependent and independent variables.

Table 12.

Descriptive statistics of dependent and independent variables.

| Specification |

y1 |

x1 |

x2 |

x3 |

x4 |

x5 |

x6 |

x7 |

x8 |

| Mean |

40.34 |

2.04 |

6.68 |

49.80 |

19.45 |

12.80 |

9.23 |

72.34 |

30.15 |

| Standard error |

0.70 |

0.49 |

0.28 |

0.82 |

0.62 |

0.70 |

0.91 |

0.86 |

0.67 |

| Median |

38.62 |

1.74 |

6.16 |

50.00 |

19.12 |

10.81 |

4.29 |

74.26 |

29.66 |

| Standard deviation |

10.44 |

1.10 |

4.19 |

12.29 |

9.20 |

10.50 |

13.89 |

12.86 |

10.00 |

| Kurtosis |

-0.77 |

0.03 |

0.41 |

1.10 |

-0.49 |

-0.72 |

3.34 |

2.84 |

-0.86 |

| Skewness |

0.06 |

0.12 |

2.17 |

0.28 |

0.52 |

0.74 |

2.06 |

-1.24 |

0.21 |

| Range |

47.30 |

4.46 |

33.30 |

71.97 |

41.23 |

41.27 |

52.88 |

75.38 |

41.17 |

| Minimum |

18.06 |

0.36 |

2.32 |

12.98 |

2.12 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

17.56 |

11.27 |

| Maximum |

65.36 |

4.82 |

35.62 |

84.95 |

43.45 |

41.27 |

52.88 |

92.94 |

52.44 |

| Coefficient of variation V (%) |

25.88 |

53.92 |

62.72 |

24.69 |

47.30 |

82.03 |

150.49 |

17.78 |

33.16 |