1. Introduction

In the past 30 years, atomic force microscopy (AFM) has revolutionized the way we probe cell mechanics [

8]. Originally developed to provide cell topographic images [

1], it is now routinely applied to measure the mechanical properties of individual cells. AFM quantifies cell mechanics by applying a subtle but controlled force or displacement to a cell through a tiny tip and measuring the response with high precision [

19].

Unlike other methods such as fluorescent microscopy, cryo-electron tomography, or three-dimensional electron microscopy, AFM allows cell without staining, labeling, or fixation to be studied, thus under physiological conditions [

1]. Cell mechanics was observed to indicate cell biological functions such as adhesion, migration, or differentiation [

8,

14,

38]. The mechanical properties of cells are also related to pathology, particularly metastatic cancer [

15], cardiovascular disease [

24], or infection by microbes or viruses [

21].

During the development of the AFM technique, considerable effort was put into developing fast, accurate, and gentle microscopes. High-speed imaging of living cells permits the study of drugs in surface cell structures [

8] or mechanical mapping of subcellular and subnuclear structures in real time [

9]. Although progress in instrumentation and method has been considerable, little has changed in processing and analysis of AFM results.

In mechanical analysis, the response of the material to external stimuli, such as applied fields or forces, is expressed by constitutive parameters [

16]. These are quantities that are specific to each material. In theory, the constitutive parameters should be independent of the measurement instrument, sample, method, or model. In a first approximation, the cell could be considered as a homogeneous isotropic elastic material and hence characterized by two parameters, e.g. Young’s modulus

E and Poisson ratio

[

11]. Young’s modulus describes how a cell material resists deformation when uniaxial stress is applied, while Poisson’s ratio is a measure of how much the cell deforms in the lateral direction when compressed in the axial direction. Since the Poisson ratio of most soft biological tissues is very close to 0.5 [

17] and the error in Young’s modulus due to the unknown Poisson ratio is less than 10% [

7], cell mechanics is usually characterized only by the Young modulus [

11].

The AFM provides a non-linear force/displacement curve even for elastic engineering materials that are conditioned by non-linear contact mechanics between the small tip and large sample. To extract the elastic modulus from AFM experiments, a model of contact mechanics is usually employed. The most common models are the Hertz and Sneddon models for spherical and conical indenters, respectively [

12,

30].

For the Hertz model, the dependence between the indentation force

F and indentation depth

h for a stiff spherical tip of radius

R is expressed as [

32]:

where

is the reduced Young modulus:

The basic assumptions in the derivation of the Hertz model are that the strains are small and within the elastic limit, which means that the cell material behaves linearly and recovers its original shape after the contact; the surfaces of the cell and indenter are continuous and nonconforming, which means that the contact area is much smaller than the characteristic dimensions of the cell and the tip; the cell can be considered as an elastic half-space, which means that the cell volume is infinitely large compared to the area of contact and flat far away from the contact area; and the cell surface is frictionless, which means that there is no tangential force or shear stress between the surfaces of the AFM tip and cell; the AFM tip is absolutely stiff with the shape of an exact sphere, which means that deformations of the tip and substrate are negligible compared to cells. Deviation from these assumptions in live cells given by the geometry, composition and material heterogeneity of the cell s brings additional variability into the estimated Young’s modulus [

13].

In this study, we will address one particular effect, cell size. Although theoretical and experimental cell studies based on elastic shell theory [

33] and liquid drop theory [

23] suggest that cell stiffness is considerably affected by its dimensions, it is neglected in Hertz theory. We hypothesized that larger cells will have a smaller stiffness and therefore a smaller Young’s modulus, and vice versa. To reduce the effect of mechanical and shape variability between individual cells, we will use liposomes as cell models and evaluate Young’s modulus by fitting the standard Hertz model to the experimental AFM force/deflection curves.

2. Materials and Methods

Liposomes preparation

Liposomes are prepared using a two-stage microfluidic device that produces filled liposomes using the double emulsion drop method. The custom-made microfluidic device was manufactured using PolyJet technology (Polyjet J750, Stratasys, MN, USA) from VeroClear-RGD810. The device consists of an inner aqueous phase channel, two lipid-carrying organic phase channels, an intermediate channel, two outer aqueous phase channels, and a downstream channel. Using volume-controlled flow pumps, the inner aqueous stream of HA (molecular weight 2000–2200 kDa, concentration 5:1, Contipro, CZ) is dissolved in PBS (200 ml) for filled liposomes or PBS (10 ml) for empty liposomes. The surrounding lipid-carrying streams (DPPC in isopropyl alcohol, Sigma-Aldrich, DE) are hydrodynamically focused, and a single emulsion droplet is formed by shearing the inner phase. Subsequently, a double emulsion is formed by two external streams of aqueous PBS (10 ml). As the aim of the study was to produce liposomes of various sizes, the diameter of the inner channel is 0.5 mm, allowing the formation of multidispersed liposomes. Liposome formation was driven by shear flow at the junctions by setting the individual flow rate ratio at 5, 10 and 15 ml / h for phospholipids, inner fluid and outer fluid, respectively. Liposome formation and flow focusing were inspected in situ using a phase microscope (NIB-100 Inverted Microscope with Canon SCR Camera, Canon DE).

Liposomes fixation

The binding required to measure the mechanical properties of liposomes by AFM was achieved using an avidin-biotin complex. Biotin-DOPE and DPPC lipids were used at a concentration of 1: 1000. The biotinylated surface was then incubated with avidin (0.30 mg/ml) and washed three times with PBS buffer. Finally, 1 ml of the liposomal formulation and approximately 1 ml of PBS buffer were applied to a Petri dish and incubated for 5 min at room temperature [

34,

37].

AFM measurements

Mechanical testing of the liposomes was performed by the NanoWizard® 3 NanoOptics AFM System (JPK, DE). A colloidal probe with a diameter of 5.2

m was used, with a spring rigidity constant of 0.0307 N/m (APPnano, CA, USA). The cantilever was calibrated using the standard procedure recommended by the manufacturer. First, the sensitivity of the cantilever was determined using indentation measurements on the glass, and then the stiffness of the cantilever was determined using thermal noise. Force spectroscopy of the liposomes was performed with a z length of 15

m, a relative set point of 20nN, and the loading rate was 3.75um/s. The following inclusion criteria are applied: the isolated spherical shape of the liposome without collapse [

29] or extensive adhesion to the surface [

35], and at least two successful measurements in each liposome. Force/deformation curves were measured in the center of the liposome.

Data processing

After subtracting the deflection of the cantilever, the force-displacement curves were fitted using the Hertz model for a hemispherical cantilever tip with a Poisson number equal to 0.5 according to the method described in Thomas et al., 2013 . Data showing strong attachment of liposomes to the surface (small height compared to diameter), liposome burst (rapid change in force), or extensive noise (AFM tip fouling) were excluded from the analysis. The final analysis includes 162 measurements (116 and 46 in empty and HA-filled liposomes, respectively) in 46 liposomes (31 and 15 in empty and HA-filled liposomes, respectively).

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyzes were performed with R software (version 4.1.2, R Core Team, 2021). A

p value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. The normality of the data was tested using the Shapiro-Wilk test. The differences in Young’s modulus between different liposome types or treatments were analyzed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Tukey’s post hoc test for normally distributed data and by Wilcoxon rank sum test otherwise. The correlation between Young’s modulus and cell size was assessed using linear regression (package lme4) considering repeated measurements [

2]. 95% confidence intervals (CI) and the

p values were calculated using a Wald

t distribution approximation.

3. Results

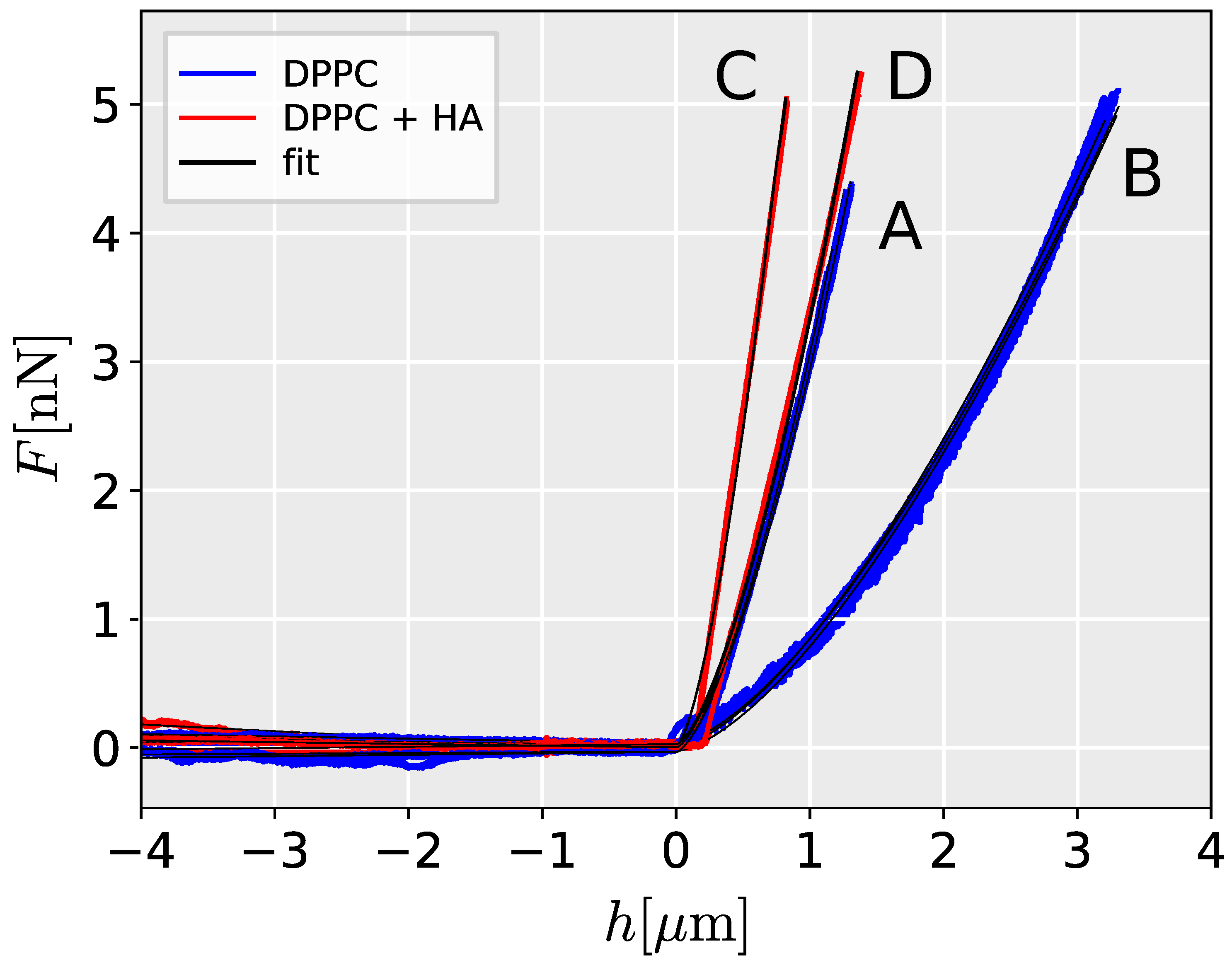

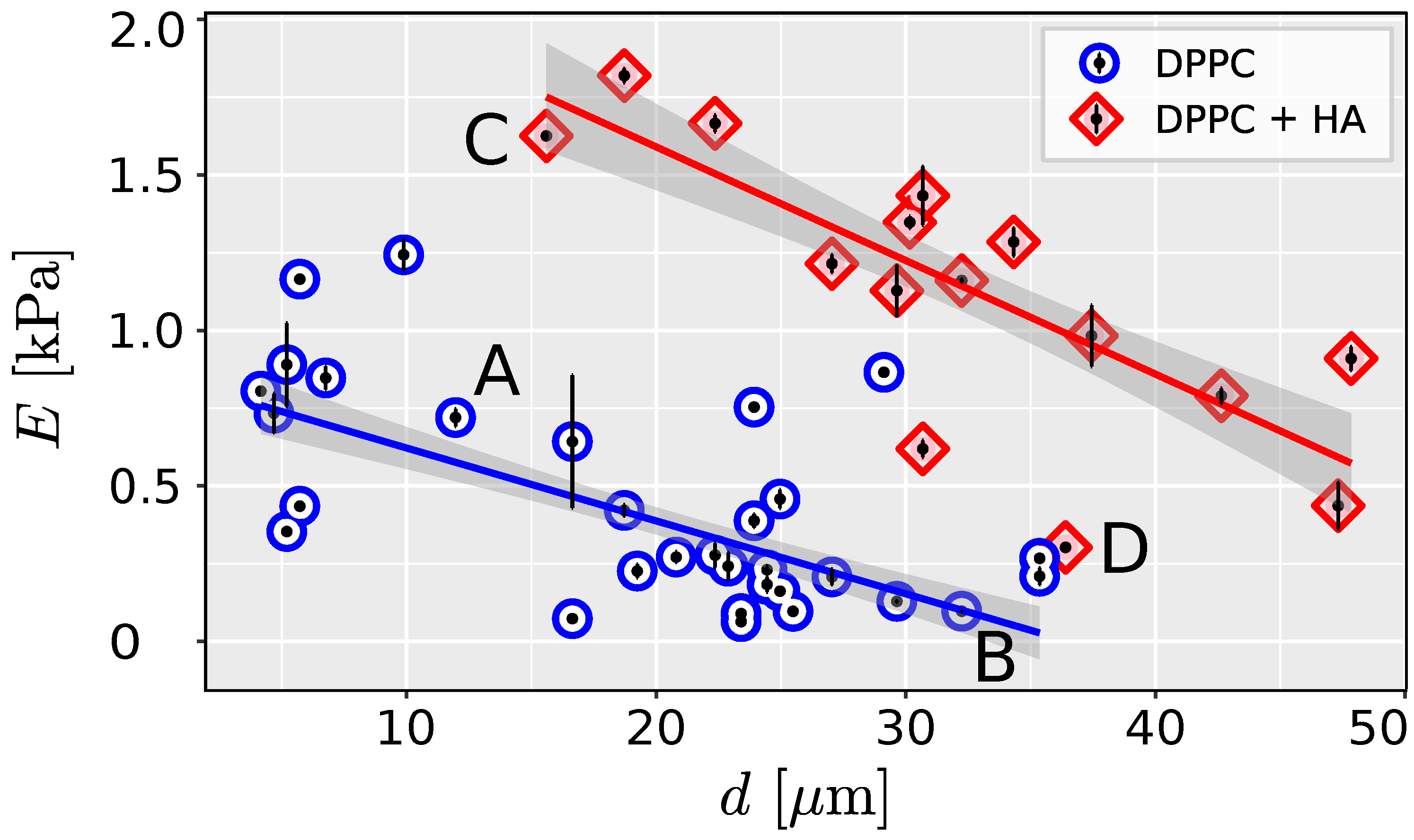

The Hertz model provides a good fit to the AFM data, as evidenced by the high correlation coefficient between the measured and predicted values (Pearson correlation coefficient mean 0.998 for all measurements, range 0.9881-0.999). Representative loading curves are presented in

Figure 1. Young’s modulus in HA-filled liposomes (mean 1.11 kPa, range 0.30-1.85 kPa) is significantly higher than in PBS-filled liposomes (mean 0.37 kPa, range 0.62-1.28 kPa) (Wilcoxon rank sum test,

W=423,

0.001). The higher stiffness in HA-filled liposomes corresponds to steeper force/deflection curves (

Figure 1). The results showed a high degree of agreement between repeated measurements, as indicated by the low variation between the measured curves and in the estimated Young modulus (

Figure 1 and

Figure 2).

Linear regression was used to test whether liposome size significantly predicts Young’s modulus. For both liposomes filled with PBS and HA, the effect of the liposome diameter d is statistically significant and negative ( = -23.44, 95% CI [-28.33, -18.56], 0.001 for the liposome filled with PBS and = -36.53, 95% CI [-45.58, -27.48], 0.001 for liposomes filled with HA). The effect of the diameter of the liposome on Young’s modulus is significantly higher for HA-filled liposomes (ANOVA ).

4. Discussion

One of the main assumptions of the Hertz model for the analysis of contact mechanics is that the cell is elastic, isotropic, and homogeneous, and that the indentation is small compared to the size of the cell [

32]. In this study, we have evaluated the effect of cell size on the estimated Young’s modulus using liposomes as cell models while adopting the methods proposed for cell mechanics measurements [

31]. We have shown that there is a considerable dependence between the size of the measured liposome and its stiffness (

Figure 1 and

Figure 2).

Our findings are in agreement with the previous studies of Delorme et al., 2006 who observed higher stiffness in smaller liposomes. The observed effect of liposome size is consistent with the shell theory of cell deformation [

5,

27]. Real-time deformability cytometry also indicates greater deformation for larger cells of the same phenotype [

22] as shown in our study.

The scattering of data in

Figure 2 indicates the presence of other factors influencing the measured mechanical response. A parameter that has not been fully evaluated is liposome adhesion. In a theoretical [

28] and experimental study [

40] was shown that extensive cell adhesion increases cell membrane tension and stiffness. AFM measurements also indicate that the stiffness of adherent epithelial cells increases with increasing the projected area of apical cells[

20]. Therefore, liposomes adhered to the surface considerably and were excluded from the analysis. Overbeck et al., 2017 showed that, in addition to cell size, osmotic pressure could affect cell response, where higher osmolarity of the culture contributes to a decrease in cell stiffness .

The presented results were measured in liposomes as cell models. This approach reduces the variability of the input parameters as experimental samples with fully controlled composition and geometry are prepared. Liposomes mimic the basic cell structure but may not fully describe the active behavior of living cells. The cell is a heterogeneous structure with a high level of internal organization. For example, anisotropy of the cytoskeleton induces non-axisymmetric deformation [

10] and stiffness of subcellular structures affects the local mechanical response [

9]. Prolonged or repeated indentation of single cells can result in remodeling of the cytoskeleton [

26] that could further influence cell stiffness.

To provide a more realistic artificial cell model, HA-filled liposomes were tested. The high molecular weight and the semi-flexible chain of HA induce viscous and elastic properties [

3] as we may observe in the cytoplasm [

39]. The viscosity of the HA solution used (100 Pa s)[

25] corresponds to the viscosity of the cell cytoplasm [

36]. The artificial cytoplasm (HA) makes cells stiffer and improves their potential to transmit a load similar to that of living cells. It could be assumed that the filled liposome would be closer to the continuum and therefore satisfy the assumptions of the Hertz model. However, the addition of HA that mimics the cytoplasm increases the effect of cell size on the estimated Young’s modulus. Our results therefore indicate that the inner environment should be considered in the modeling of cell mechanics. More research is warranted to quantify the dependence between cell size and stiffness in confluent and highly adhered living cells with complex internal organization.

5. Conclusions

AFM provides an estimate of the stiffness of living cells. Usually, a large number of single cells should be analyzed to ensure statistical precision for highly heterogeneous cell samples [

18]. However, the potential of AFM also lies in the detection of the cell state based on single-cell analysis [

4]. To improve the reliability of single-cell mechanics methods, the source of potential variability between individual cells should be identified. In addition to physiological variability, the testing method and the post-processing of data might introduce additional technical variability. On the basis of the presented measurements, it could be concluded that the cell size, neglected in the basic hypothesis of the Hertz model, considerably influences the measured stiffness and the estimated Young’s modulus. Therefore, when comparing individual cells, cells of approximately the same size should be considered. More research is needed to define an exact correction factor for specific living cells with complex internal organization.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.D. and K.M.; methodology, M.O.; software, M.D.; validation, K.M., M.D; formal analysis, M.D.; investigation, K.M., M.D,; resources, M.D.; data curation, M.D.; writing—original draft preparation, M.D.; writing—review and editing, K.M., M.O.; visualization, K.M.; funding acquisition, M.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Grant Agency of the Czech Technical University in Prague, grant No. SGS22/149/OHK2/3T/12.

Data Availability Statement

The original data presented in the study are openly available in Zenodo at DOI:10.5281/zenodo.11198627.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Alsteens, D. , Beaussart, A., El-Kirat-Chatel, S., Sullan, R.M.A., Dufrêne, Y.F., 2013. Atomic Force Microscopy: A New Look at Pathogens. PLOS Pathogens 9, e1003516. [CrossRef]

- Bates, D. , Mächler, M., Bolker, B., Walker, S., 2015. Fitting Linear Mixed-Effects Models Using lme4. Journal of Statistical Software 67, 1–48. [CrossRef]

- Cowman, M.K. , Schmidt, T. Viscoelastic Properties of Hyaluronan in Physiological Conditions. F 1000Research 4, 622. [CrossRef]

- Cross, S.E. , Jin, Y.S., Rao, J., Gimzewski, J.K., 2009. Applicability of AFM in cancer detection. Nature Nanotechnology 4, 72–73. [CrossRef]

- Delorme, N. , Dubois, M., Garnier, S., Laschewsky, A., Weinkamer, R., Zemb, T., Fery, A., 2006. Surface Immobilization and Mechanical Properties of Catanionic Hollow Faceted Polyhedrons. The Journal of Physical Chemistry B 110, 1752–1758. [CrossRef]

- Delorme, N. , Fery, A., 2006. Direct method to study membrane rigidity of small vesicles based on atomic force microscope force spectroscopy. Physical Review E 74.

- Dokukin, M.E. , Sokolov, I., 2012. On the Measurements of Rigidity Modulus of Soft Materials in Nanoindentation Experiments at Small Depth. [CrossRef]

- Dufrêne, Y.F. , Viljoen, A., Mignolet, J., Mathelié-Guinlet, M., 2021. AFM in cellular and molecular microbiology. Cellular Microbiology 23. [CrossRef]

- Efremov, Y.M. , Suter, D.M., Timashev, P.S., Raman, A., 2022. 3D nanomechanical mapping of subcellular and sub-nuclear structures of living cells by multi-harmonic AFM with long-tip microcantilevers. Scientific Reports 12, 529. [CrossRef]

- Efremov, Y.M. , Velay-Lizancos, M., Weaver, C.J., Athamneh, A.I., Zavattieri, P.D., Suter, D.M., Raman, A., 2019. Anisotropy vs isotropy in living cell indentation with AFM. Scientific Reports 9, 5757. [CrossRef]

- Guz, N. , Dokukin, M., Kalaparthi, V., Sokolov, I., 2014. If Cell Mechanics Can Be Described by Elastic Modulus: Study of Different Models and Probes Used in Indentation Experiments. Biophysical Journal 107, 564–575. [CrossRef]

- Kontomaris, S.V. , Malamou, A., 2020. Hertz model or Oliver & Pharr analysis? Tutorial regarding AFM nanoindentation experiments on biological samples. Materials Research Express 7, 033001. [CrossRef]

- Lekka, M. , Laidler, P., 2009. Applicability of AFM in cancer detection. Nature nanotechnology 4, 72; author reply 72–3. [CrossRef]

- Li, M. , Dang, D., Liu, L., Xi, N., Wang, Y., 2017. Atomic Force Microscopy in Characterizing Cell Mechanics for Biomedical Applications: A Review. IEEE Transactions on NanoBioscience 16, 523–540. [CrossRef]

- Li, M. , Xi, N., Wang, Y.c., Liu, L.q., 2021. Atomic force microscopy for revealing micro/nanoscale mechanics in tumor metastasis: From single cells to microenvironmental cues. Acta Pharmacologica Sinica 42, 323–339. [CrossRef]

- Lim, C.T. , Zhou, E.H., Quek, S.T., 2006. Mechanical models for living cells—a review. Journal of Biomechanics 39, 195–216. [CrossRef]

- Liu, B. , Zhang, L., Gao, H., 2006. Poisson ratio can play a crucial role in mechanical properties of biocomposites. Mechanics of Materials 38, 1128–1142. [CrossRef]

- Marcotti, S. , Reilly, G.C., Lacroix, D., 2019. Effect of cell sample size in atomic force microscopy nanoindentation. Journal of the Mechanical Behavior of Biomedical Materials 94, 259–266. [CrossRef]

- Moeendarbary, E. , Harris, A.R., 2014. Cell mechanics: Principles, practices, and prospects. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews. Systems Biology and Medicine 6, 371–388. [CrossRef]

- Nehls, S. , Nöding, H., Karsch, S., Ries, F., Janshoff, A., 2019. Stiffness of MDCK II Cells Depends on Confluency and Cell Size. Biophysical Journal 116, 2204–2211. [CrossRef]

- Ohnesorge, F.M. , Hörber, J.K., Häberle, W., Czerny, C.P., Smith, D.P., Binnig, G., 1997. AFM review study on pox viruses and living cells. Biophysical Journal 73, 2183–2194. [CrossRef]

- Otto, O. , Rosendahl, P., Mietke, A., Golfier, S., Herold, C., Klaue, D., Girardo, S., Pagliara, S., Ekpenyong, A., Jacobi, A., Wobus, M., Toepfner, N., Keyser, U., Mansfeld, J., Fischer-Friedrich, E., Guck, J., 2015. Real-time deformability cytometry: On-the-fly cell mechanical phenotyping. Nature methods 12. [CrossRef]

- Overbeck, A. , Günther, S., Kampen, I., Kwade, A., 2017. Compression Testing and Modeling of Spherical Cells – Comparison of Yeast and Algae. Chemical Engineering & Technology 40, 1158–1164. [CrossRef]

- Peña, B. , Adbel-Hafiz, M., Cavasin, M., Mestroni, L., Sbaizero, O., 2022. Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) Applications in Arrhythmogenic Cardiomyopathy. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 23, 3700. [CrossRef]

- Rebenda, D. , Vrbka, M., Čípek, P., Toropitsyn, E., Nečas, D., Pravda, M., Hartl, M., 2020. On the Dependence of Rheology of Hyaluronic Acid Solutions and Frictional Behavior of Articular Cartilage. Materials 13, 2659. [CrossRef]

- Reed, J. , Troke, J.J., Schmit, J., Han, S., Teitell, M.A., Gimzewski, J.K., 2008. Live Cell Interferometry Reveals Cellular Dynamism During Force Propagation. ACS Nano 2, 841–846. [CrossRef]

- Reissner, E. , 1952. Stress Strain Relations in the Theory of Thin Elastic Shells. Journal of Mathematics and Physics 31, 109–119. [CrossRef]

- Ren, K. , Gao, J., Han, D., 2021. AFM Force Relaxation Curve Reveals That the Decrease of Membrane Tension Is the Essential Reason for the Softening of Cancer Cells. Frontiers in Cell and Developmental Biology 9.

- Ruozi, B. , Tosi, G., Leo, E., Vandelli, M.A., 2007. Application of atomic force microscopy to characterize liposomes as drug and gene carriers. Talanta 73, 12–22. [CrossRef]

- Sen, S. , Subramanian, S., Discher, D.E., 2005. Indentation and Adhesive Probing of a Cell Membrane with AFM: Theoretical Model and Experiments. Biophysical Journal 89, 3203–3213. [CrossRef]

- Thomas, G. , Burnham, N.A., Camesano, T.A., Wen, Q., 2013. Measuring the Mechanical Properties of Living Cells Using Atomic Force Microscopy. J: Journal of Visualized Experiments, 5049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timoshenko, S. , Goodier, J.N., 1951. Theory of Elasticity. McGraw-Hill.

- Tsugawa, S. , Yamasaki, Y., Horiguchi, S., Zhang, T., Muto, T., Nakaso, Y., Ito, K., Takebayashi, R., Okano, K., Akita, E., Yasukuni, R., Demura, T., Mimura, T., Kawaguchi, K., Hosokawa, Y., 2022. Elastic shell theory for plant cell wall stiffness reveals contributions of cell wall elasticity and turgor pressure in AFM measurement. Scientific Reports 12, 13044. [CrossRef]

- Ungai-Salánki, R. , Csippa, B., Gerecsei, T., Péter, B., Horvath, R., Szabó, B., 2021. Nanonewton scale adhesion force measurements on biotinylated microbeads with a robotic micropipette. Journal of Colloid and Interface Science 602, 291–299. [CrossRef]

- Vorselen, D. , Piontek, M.C., Roos, W.H., Wuite, G.J.L., 2020. Mechanical Characterization of Liposomes and Extracellular Vesicles, a Protocol. Frontiers in Molecular Biosciences 7.

- Wang, K. , Sun, X.H., Zhang, Y., Zhang, T., Zheng, Y., Wei, Y.C., Zhao, P., Chen, D.Y., Wu, H.A., Wang, W.H., Long, R., Wang, J.B., Chen, J., 2019. Characterization of cytoplasmic viscosity of hundreds of single tumour cells based on micropipette aspiration. Royal Society Open Science 6, 181707. [CrossRef]

- Wang, M. , Liu, Z., Zhan, W., 2018. Janus Liposomes: Gel-Assisted Formation and Bioaffinity-Directed Clustering. Langmuir 34, 7509–7518. [CrossRef]

- Wu, P.H. , Aroush, D.R.B., Asnacios, A., Chen, W.C., Dokukin, M.E., Doss, B.L., Durand-Smet, P., Ekpenyong, A., Guck, J., Guz, N.V., Janmey, P.A., Lee, J.S.H., Moore, N.M., Ott, A., Poh, Y.C., Ros, R., Sander, M., Sokolov, I., Staunton, J.R., Wang, N., Whyte, G., Wirtz, D., 2018. A comparison of methods to assess cell mechanical properties. Nature Methods 15, 491–498. [CrossRef]

- Xie, J. , Najafi, J., Le Borgne, R., Verbavatz, J.M., Durieu, C., Sallé, J., Minc, N., 2022. Contribution of cytoplasm viscoelastic properties to mitotic spindle positioning. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 119, e2115593119. [CrossRef]

- Xie, K. , Yang, Y., Jiang, H., 2018. Controlling Cellular Volume via Mechanical and Physical Properties of Substrate. Biophysical Journal 114, 675–687. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).