Submitted:

10 May 2024

Posted:

13 May 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

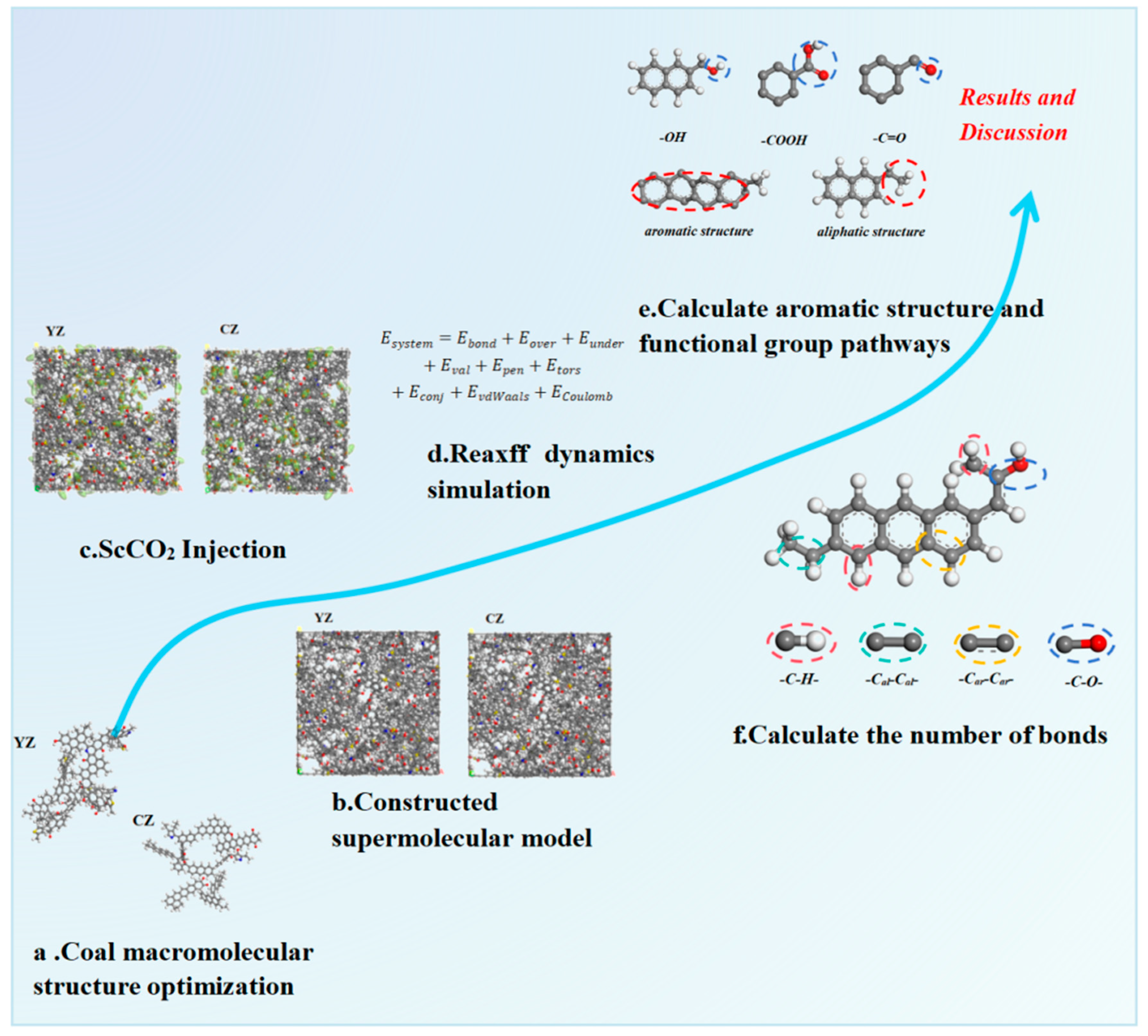

2. Simulation Process

2.1. Simulation Details

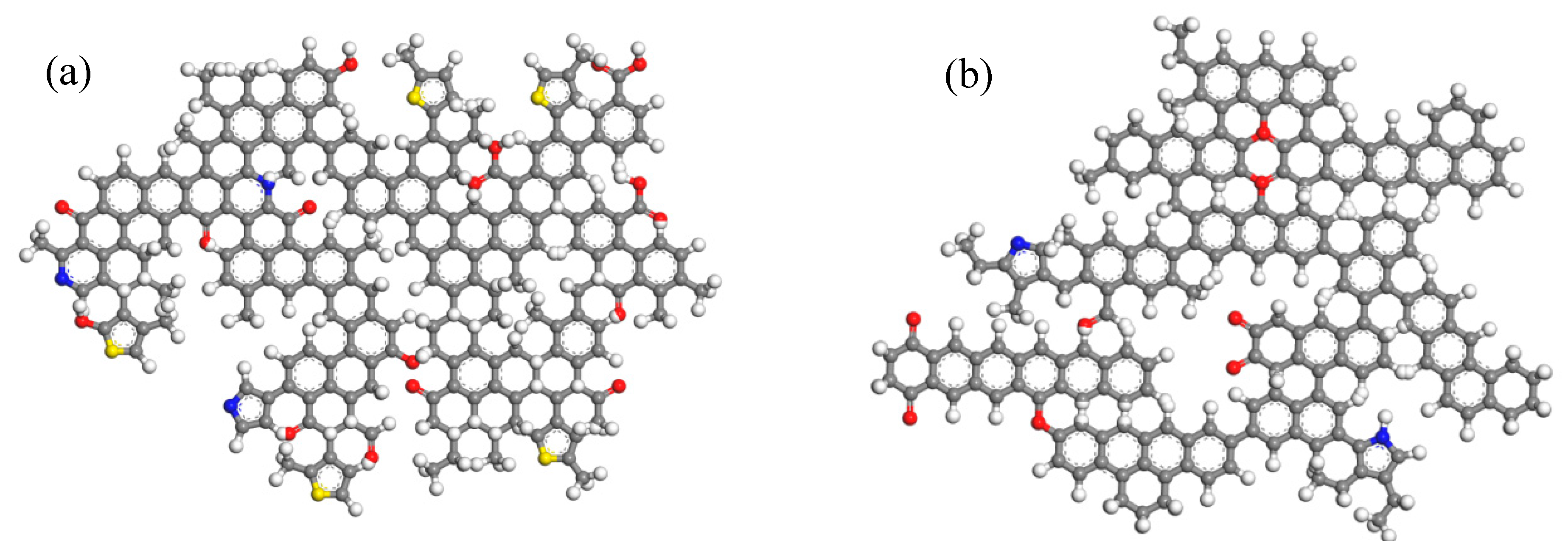

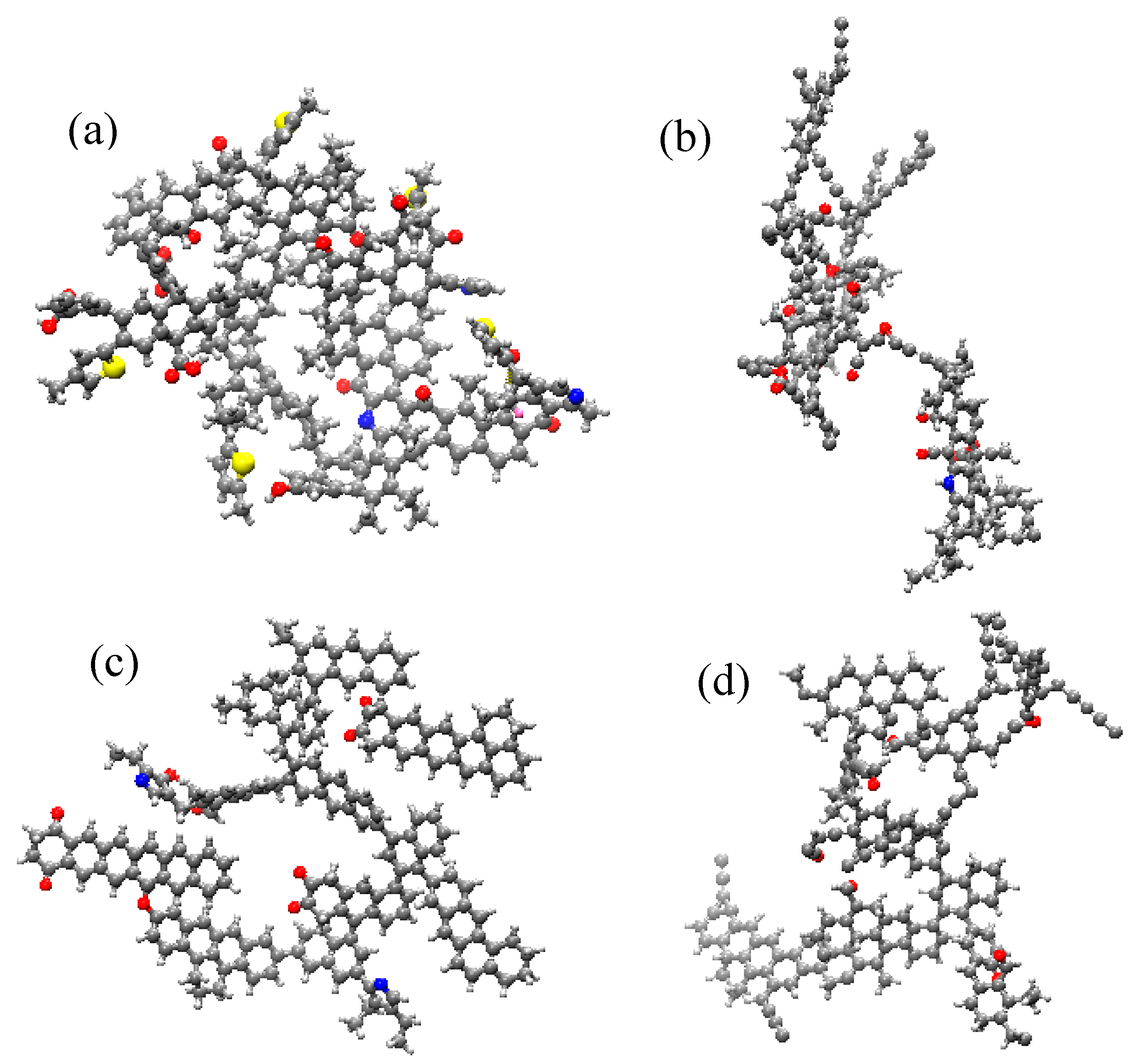

2.1.1. Model Construction

2.1.2. ScCO2 Injection Process

2.2. ReaxFF Force Field Calculate

3. Results and Discussion

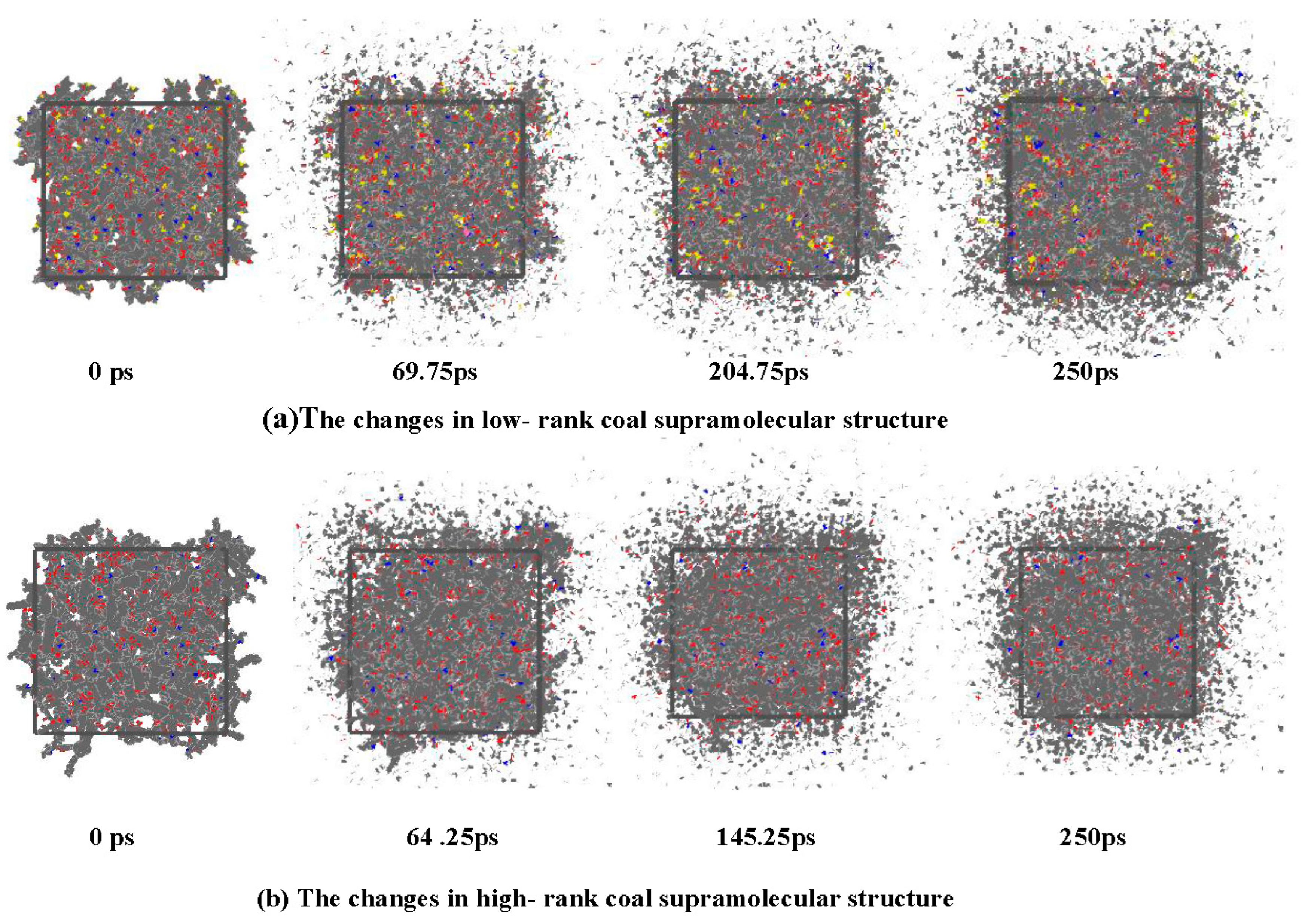

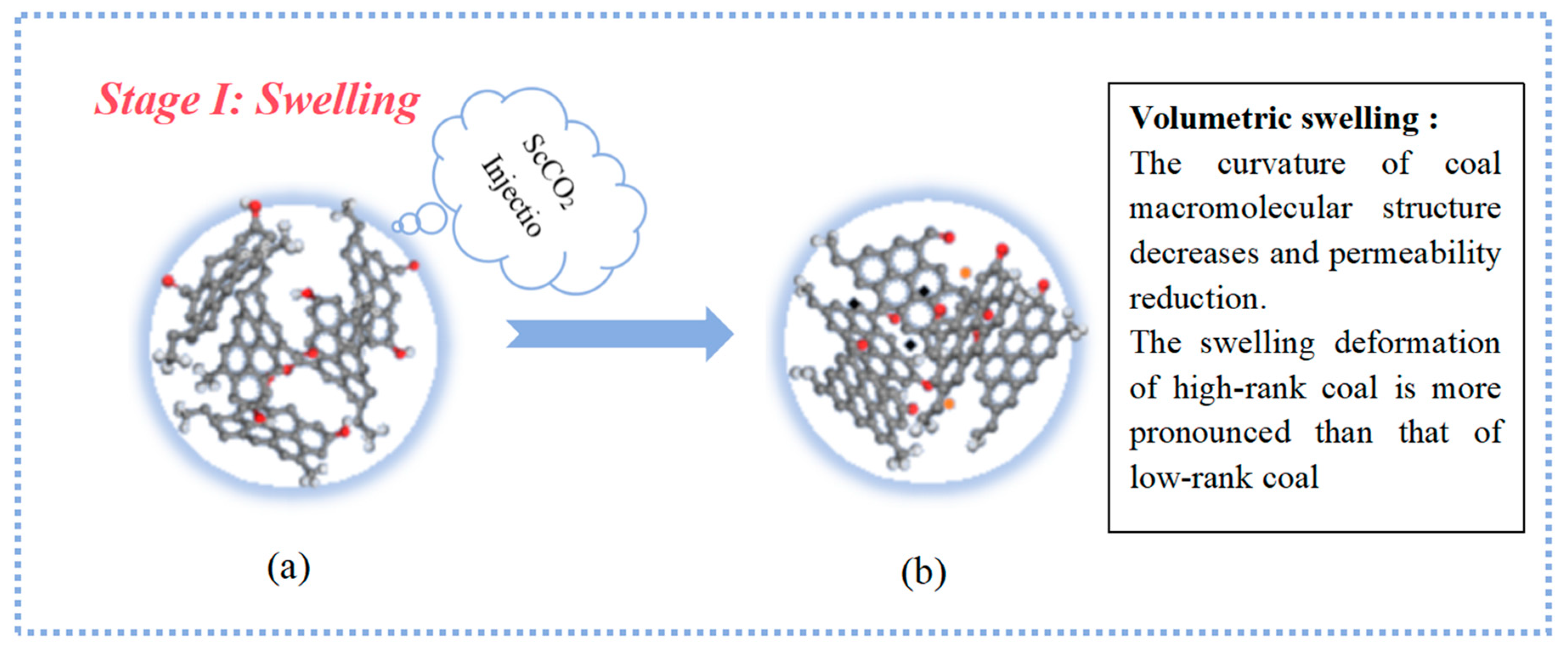

3.1. The Deformation Characteristics of Coal Molecular Structure

3.2. The Pathways of Functional Groups and Aromatic Structures

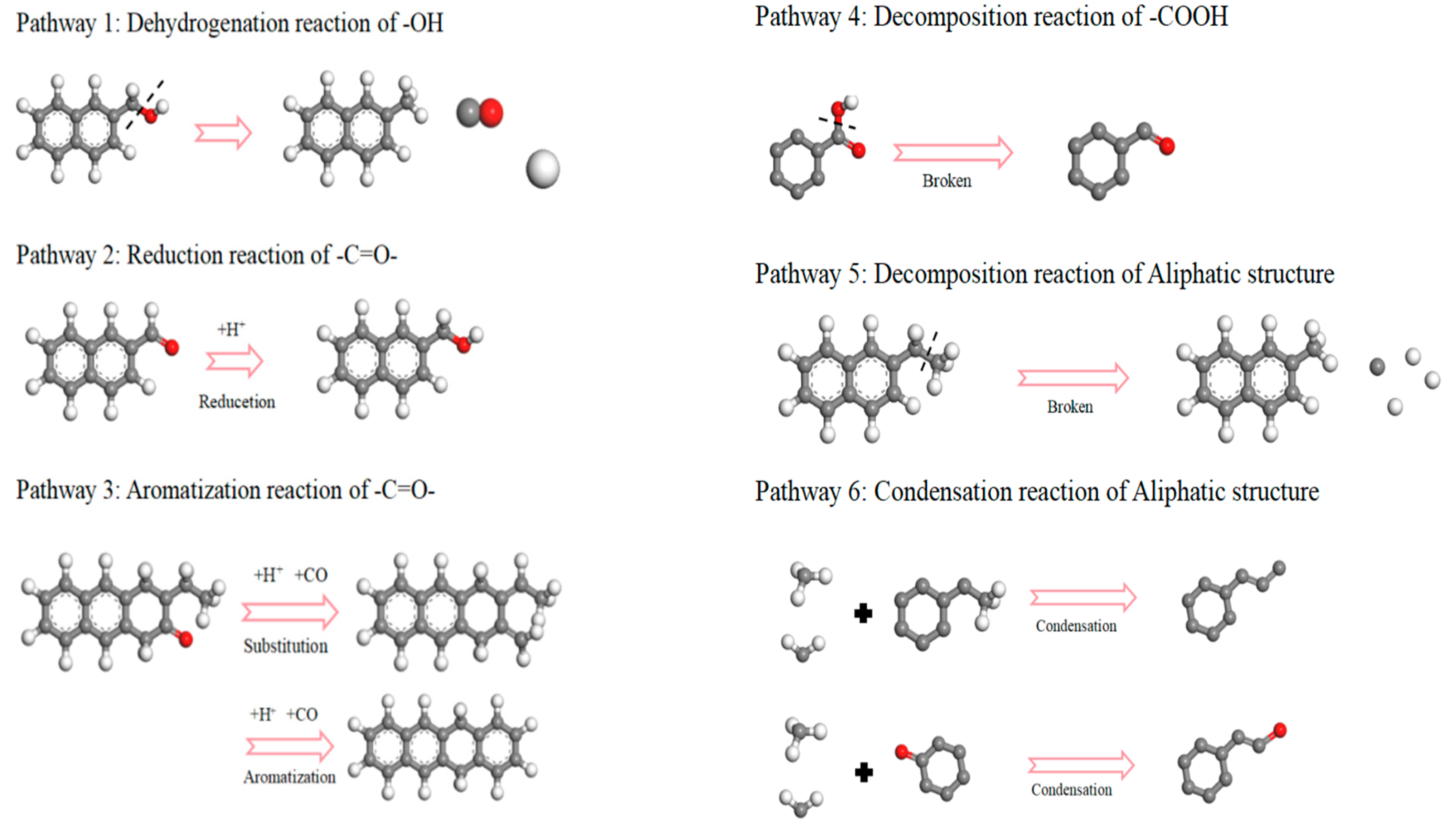

3.2.1. The Pathways of Functional Groups

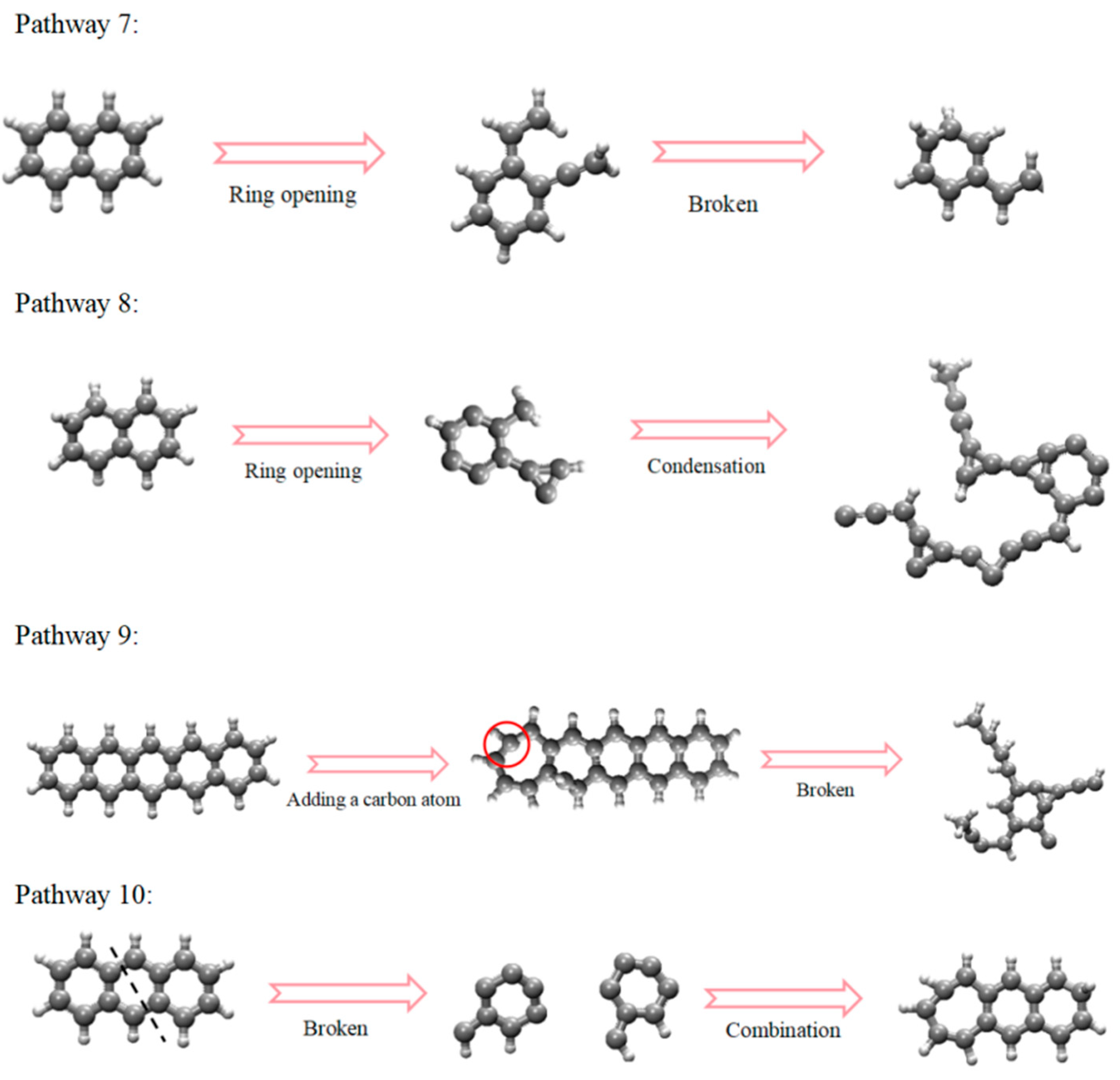

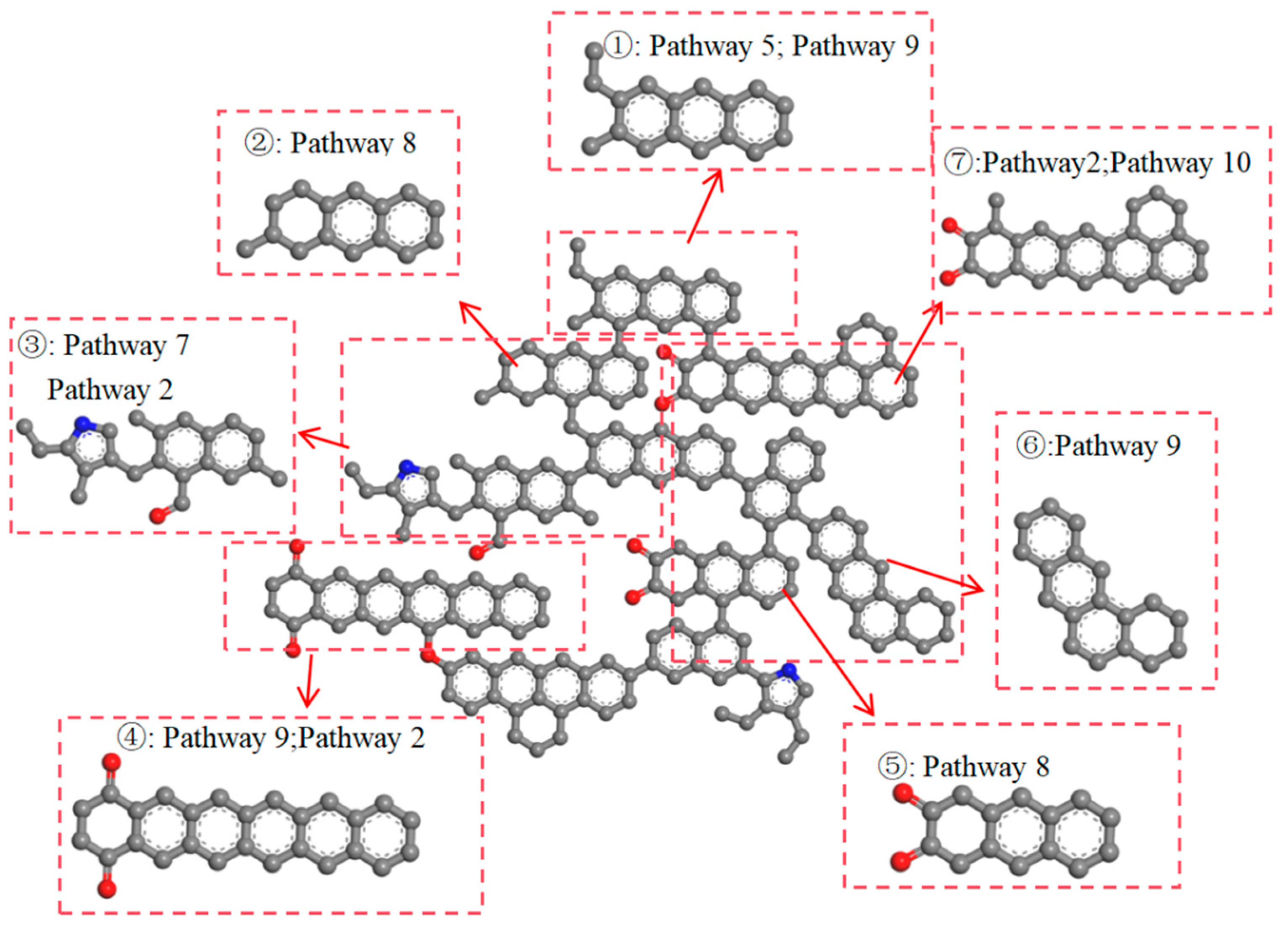

3.2.2. The Pathways of Aromatic Structures

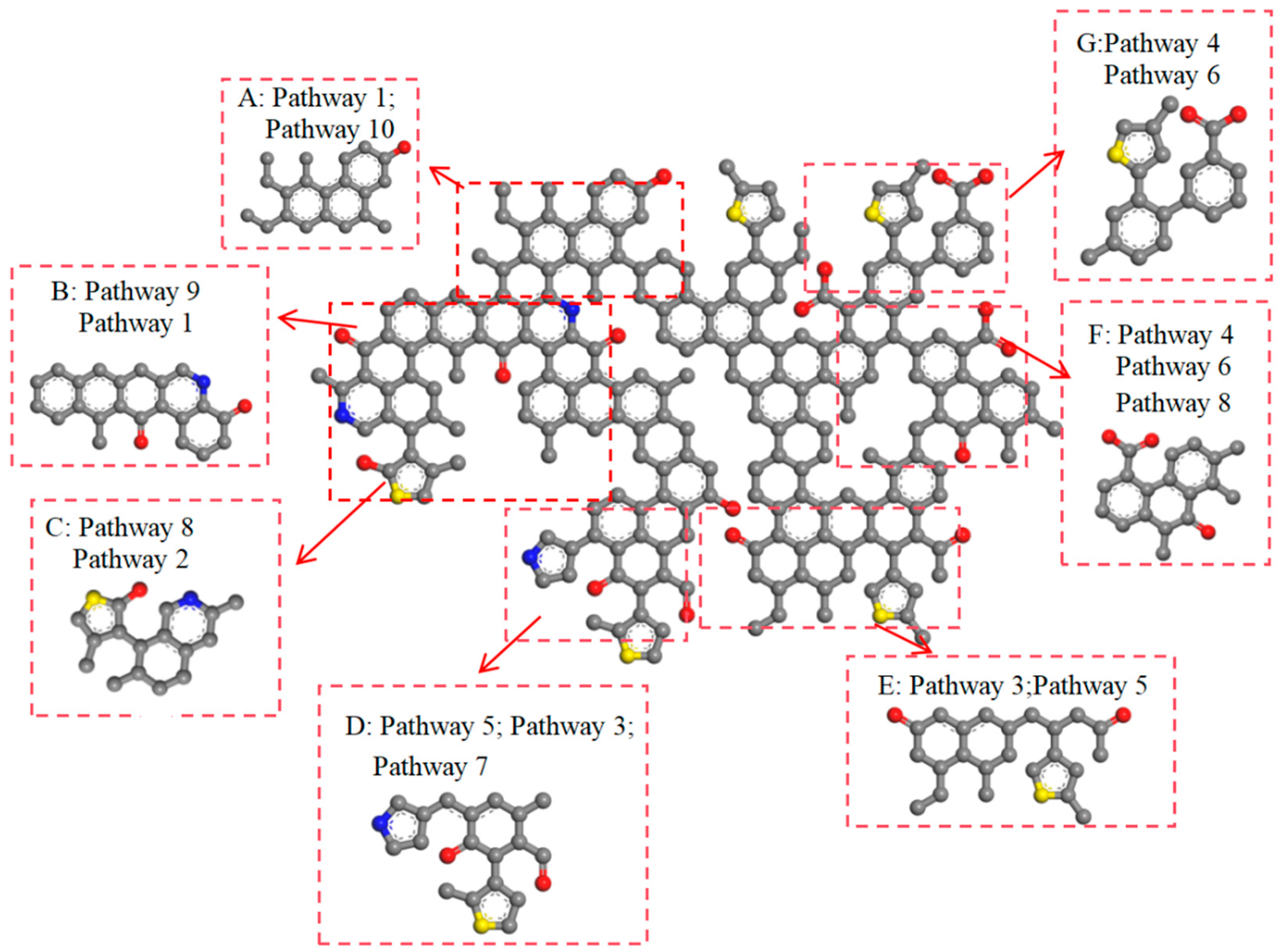

3.2.3. The Reaction Pathways of Low-Rank and High-Rank Coal

3.3. Chemical Bond Change Characteristics

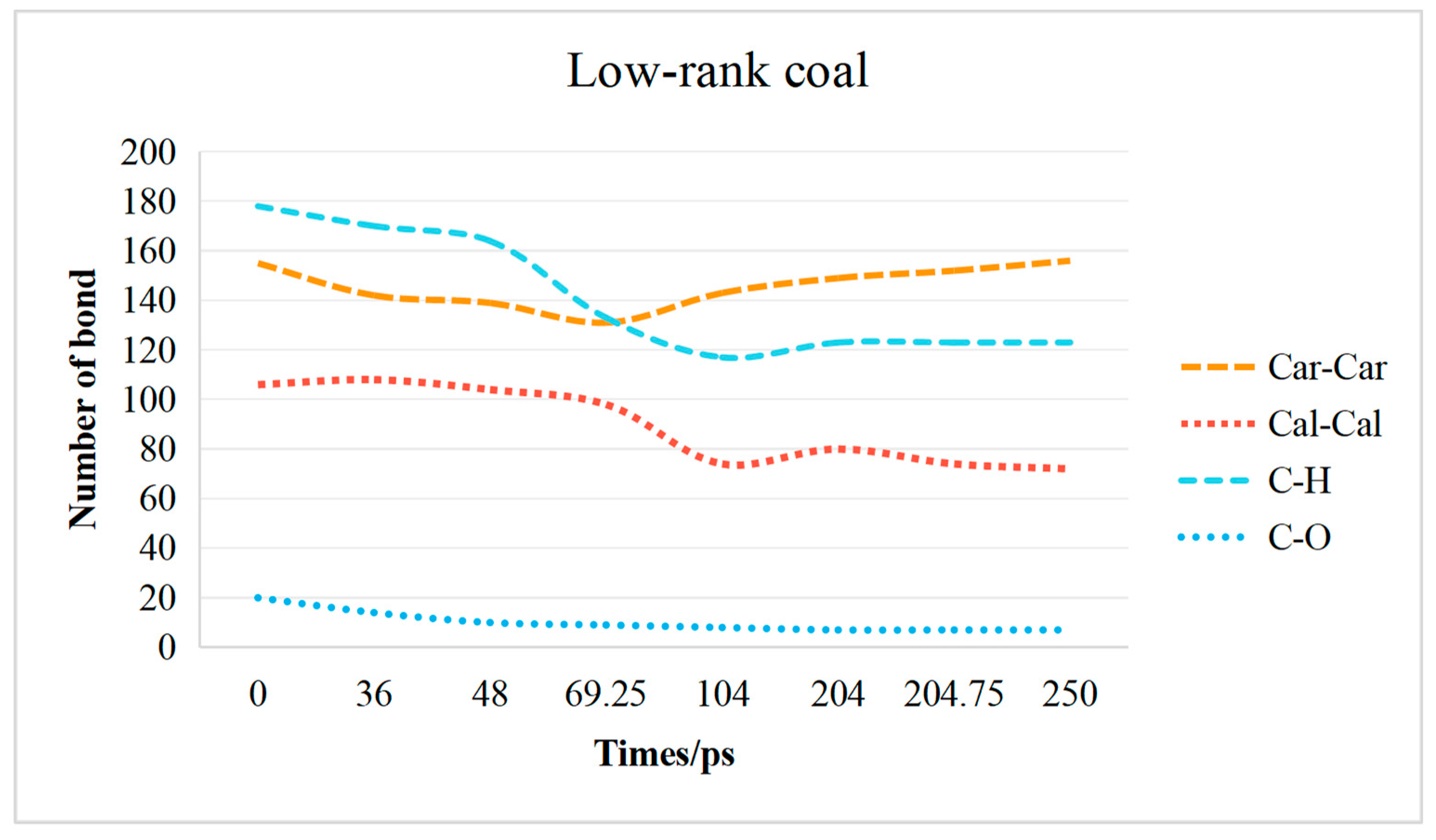

3.3.1. Low-Rank Coal Chemical Bond Change Characteristics

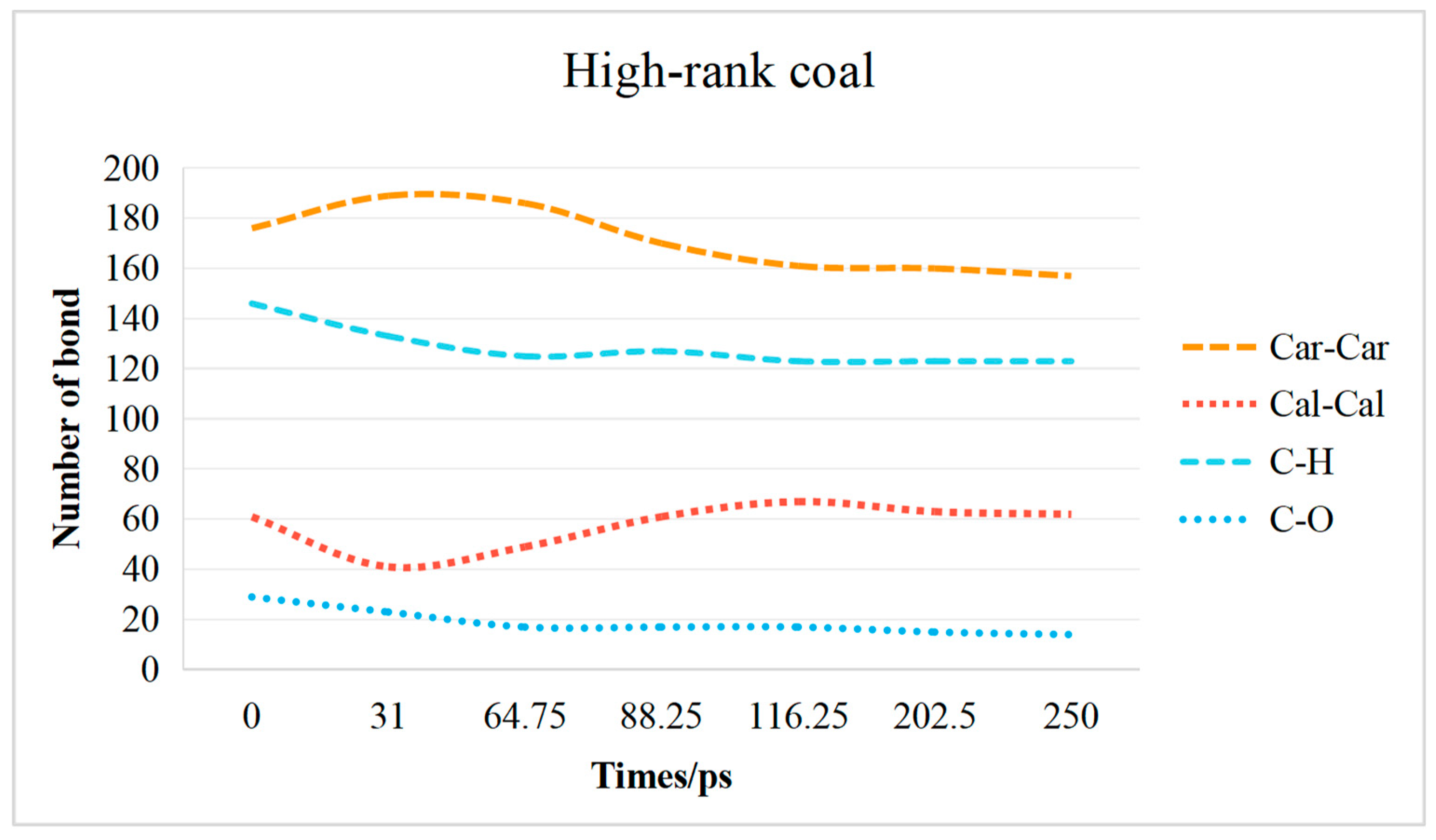

3.3.2. High-Rank Coal Chemical Bond Change Characteristics

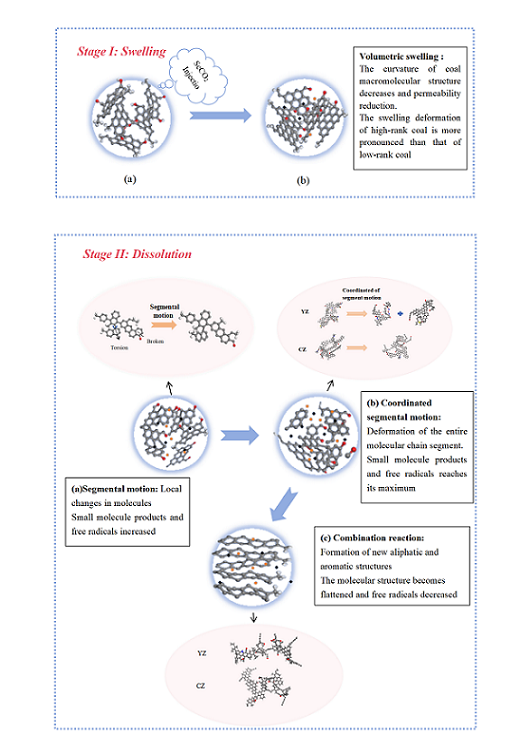

3.4. Reaction Mechanism of Low and High Rank Coal

4. Conclusion

- (1)

- The interaction between coal and ScCO2 leads to various chemical reactions, including the breakage of aliphatic side chains and oxygen-containing functional group side chains, removal of heteroatoms, and ring-opening and polymerization reactions between aliphatic and aromatic structures. The process of structural changes in low-rank coal molecules can be summarized as stretches-breakage-recombine, while in high-rank coal be summarized as stretches-migration-reconnection.

- (2)

- Functional groups and aromatic structures in coal exhibit various reaction pathways. The O-H bond in hydroxyl groups and the C-OH bond in carboxyl groups break. The carbonyl group may occur hydrogenation to form a hydroxyl group or aromatization with surrounding aliphatic structures to create aromatic ring structures. Aliphatic structures can decompose to form smaller hydrocarbon compounds or condensate to form long-chain alkenes. The reaction pathways of aromatic structures are more complex and involve processes such as breakage, rearrangement, and recombination.

- (3)

- The transformation of coal molecular structure is governed by changes in chemical bonds within the coal. The content of C-H bonds and C-O bonds decreases in both low-rank and high-rank coals. In low-rank coal, the Car-Car bonds initially decrease and then increase, while the Cal-Cal bonds initially increase and then decrease. Conversely, in high-rank coal, the Car-Car bonds initially increase and then decrease, while the Cal-Cal bonds initially decrease and then increase. Overall, in high-rank coal, both Car-Car and Cal-Cal bonds decrease, while in low-rank coal, Car-Car bonds increase and Cal-Cal bonds decrease.

- (4)

- The responses of high-rank and low-rank coal are related to the structural differences and the interaction mechanisms between ScCO2 and coal molecules. Due to the stronger adsorption affinity of aromatic structures for CO2, the changes in high-rank coal during the swelling stage are more pronounced compared to low-rank coal. At dissolution stage, chemical bonds in low-rank coal are weaker, the bonds are more prone to breaking after exposure to ScCO2, the disrupted aromatic structures or carbonyl groups combine with detached aliphatic side chains to form larger aromatic structures in low-rank coal. Conversely, in high-rank coal, there are stronger intramolecular forces, with fewer aliphatic structures and carbonyl groups, new aromatic structures are not formed, leading to a reduction in aromatic structure content.

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Xu, Y.; Lun, Z.; Hu, Z.; Guo, J.; Zhou, X.; Wang, H.; Zhao, C.; Zhang, G.; Zhang, D. Alterations in pore and fracture structure of coal matrix and its surrounding rocks due to long-term CO2-H2O-rock interaction: Implications for CO2-ECBM. Fuel 2023, 352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Wang, L.; Yang, K.; Fu, S.; Tian, C.; Pan, R. Molecular insights on influence of CO2 on CH4 adsorption and diffusion behaviour in coal under ultrasonic excitation. Fuel 2024, 355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maram, A.; Sivachidambaram, S.; Chen, M.; Shakil, M.; Hywel, R.T. Experimental investigation of CO2-CH4 core flooding in large intact bituminous coal cores using bespoke hydrostatic core holder. INT J COAL GEOL. 2023; 279: 104376.

- Han, S.; Wang, S.; Guo, C.; Sang, S.; Xu, A.; Gao, W.; Zhou, P. Distribution of the adsorbed density of supercritical CO2 onto the anthracite and its implication for CO2 geologic storage in deep coal. Geoenergy Sci. Eng. 2024, 234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Wu, C.; Zhang, X.; Gao, B. Mechanism of SC-CO2 extraction-induced changes to adsorption heat of tectonic coal. Energy 2024, 294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, X.; Cheng, Y.; Liu, Z.; Yin, H.; Wu, T.; Huo, L.; Shu, C. CO2 and CH4 adsorption on different rank coals: A thermodynamics study of surface potential, Gibbs free energy change and entropy loss. Fuel 2020, 283, 118886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asif, M.; Wang, L.; Naveen, P.; Longinos, S.N.; Hazlett, R.; Ojha, K.; Panigrahi, D. Influence of competitive adsorption, diffusion, and dispersion of CH4 and CO2 gases during the CO2-ECBM process. Fuel 2024, 358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghashghaee, M.; Karimzadeh, R. Microporous and Mesoporous Materials Evolutionary model for computation of pore-size distribution in microporous solids of cylindrical pore structure. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2011, 138, 22–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, C.; Elsworth, D.; Li, S.; Zhou, L.; Yang, Z.; Song, Y. Thermo-hydro-mechanical-chemical couplings controlling CH4 production and CO2 sequestration in enhanced coalbed methane recovery. Energy 2019, 173, 1054–1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, J.; Meng, Z.; Zhang, K.; Yao, H.; Hao, H. Pore distribution characteristics of various rank coals matrix and their influences on gas adsorption. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2020, 189, 107041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.; Wan, R.; Zhou, F.; Liu, Y.; Li, Z.; Yin, Y. Effects of supercritical CO2 extraction on adsorption characteristics of methane on different types of coals. Chem. Eng. J. 2019, 388, 123449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, Y.; Zhou, Z.; Ge, Z.; Deng, Q.; Jia, Y.; Huang, S.; Chen, C.; Gong, S. Effect of ScCO2-H2O treatment duration on the microscopic structure of coal reservoirs: Implications for CO2 geological sequestration in coal. Int. J. Coal Geol. 2024, 282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, Y.; Ning, Z.; Lyu, F.; Jia, Z. Nanoscale profiling of the relationship between in-situ organic matter roughness, adhesion, and wettability under ScCO2 based on contact mechanics. Fuel 2024, 362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, Q.; Xu, J.; Peng, S.; Yan, F.; Wang, R.; Cai, G. Effect of molecular carbon structures on the evolution of the pores and strength of lignite briquette coal with different heating rates. Fuel 2022, 307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Wang, L.; Zheng, S.; Sun, Y.; Shen, S.; Zhang, X. Research on coal matrix pore structure evolution and adsorption behavior characteristics under different thermal stimulation. Energy 2024, 287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Cheng, Y.; Jin, K.; Guo, H.; Liu, Q.; Dong, J.; Li, W. Effects of Supercritical CO2 Fluids on Pore Morphology of Coal: Implications for CO2 Geological Sequestration. Energy Fuels 2017, 31, 4731–4741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.; Liu, X.; Nie, B.; Zhang, C.; Song, D.; Wang, L.; Yang, T. Mineral dissolution and pore alteration of coal induced by interactions with supercritical CO2. Energy 2022, 248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Zhang, X.; Lu, Z.; Pan, Z.J.; Zeng, M.; Du, X.; Xiao, S. The effect of subcritical and supercritical CO2 on the pore structure of bituminous coals. J. Nat. Gas Sci. Eng. 2021, 94, 104132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu S, Wang H, Sang S, et al. Effects of pore structure changes on the CH4 adsorption capacity of coal during CO2-ECBM[J].Fuel, 2022, 330.Fuels. 2017, 31, 4731–4741.

- Wang, K.; Du, F.; Wang, G. The influence of methane and CO 2 adsorption on the functional groups of coals: Insights from a Fourier transform infrared investigation. J. Nat. Gas Sci. Eng. 2017, 45, 358–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sampath, K.; Sin, I.; Perera, M.; Matthai, S. K, Ranjith, P. G., Li, D. Effect of supercritical-CO2 interaction time on the alterations in coalpore structure.J Nat Gas Sci Eng. 2017, 76, 103214. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, X.; Mark, A.; Arndt, S.; Maria, M.; Li, Y.; Hu, W.; Mao, J. Chemical structure changes in kerogen from bituminous coal in response to dike intrusions as investigated by advanced solid-state 13C-NMR spectroscopy. Int J Coal Geol. 2013, 108, 53–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Liu, H.; Zhang, D.; Yuan, X.; Zeng, P.; Zhang, H. Effects of CO2 adsorption on molecular structure characteristics of coal: Implications for CO2 geological sequestration. Fuel 2022, 321, 124155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Ji, H.; Li, G.; Hu, S.; Liu, X. Effect of supercritical CO2 transient high-pressure fracturing on bituminous coal microstructure. Energy 2023, 282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, J.; Xing, Y.; Li, B.; Jia, P.; Wu, Y.; Yang, Q.; Wang, D. Molecular simulations of multivariate competitive adsorption of CH4, CO2 and H2O in gas-fat coal. Colloids Surfaces A: Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2024, 683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Zhu, H.Q.; Kang, R.X. Influence of uniaxial strain loading on the adsorption-diffusion properties of binary components of CH4/CO2 in micropores of bituminous coal by macromolecular simulation. Powder Technol. 2023, 427, 118715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Zhang, X.; Wang, Z.; Liu, X.; Heng, S.; Li, Y.; Sun, Z. Molecular simulation of CH4 and CO2 adsorption behavior in coal physicochemical structure model and its control mechanism. Energy 2023, 285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Xiang, J.; Deng, X.; Gao, W. Molecular simulation of the adsorption and diffusion properties of CH4 and CO2 in the microporous system of coal. Fuel 2024, 360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, H.; Lin, H.; Yan, M.; Chang, P.; Li, S.G.; Bai, Y. Molecular simulation of the competitive adsorption characteristics of CH4, CO2, N2, and multicomponent gases in coal. Powder Technol. 2021, 385, 348–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, Y.; Zhao, L.M.; Lu, X.Q.; Xu, J.; Sang, P.P.; Guo, S. Molecular simulation of CO2/CH4 adsorption in brown coal: Effect of oxygen-, nitrogen-, and sulfur-containing functional groups. Appl Surf Sc. 2017, 423, 33–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.Q.; He, X.; Qiu, N.X.; Yang, X.; Tian, Z.Y.; Li, M.J. Molecular simulation of CH4, CO2, H2O and N2 molecules adsorptionon heterogeneous surface models of coal. Appl Surf Sc. 2016, 389, 894–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Wang, L.; Yang, K.; Fu, S.; Tian, C.; Pan, R. Molecular insights on influence of CO2 on CH4 adsorption and diffusion behaviour in coal under ultrasonic excitation. Fuel 2024, 355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.R.; Zhang, X.X.; Fu, X.L.; Liu, J.P.; Qi, X.F.; Yan, Q.L. Decomposition mechanisms of insensitive 2D energetic polymer TAGPusing ReaxFF molecular dynamics simulation combined with Pyro-GC/MS experiments. J Anal Appl Pyrol. 2022, 162, 105453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Lu, J.; Zheng, F.; Lyu, W. Molecular structure model construction and pyrolysis mechanism study on low-rank coal by experiments and ReaxFF simulations. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song Y, Jiang B, Li W.Molecular Simulation of CH4/CO2/H2O Competitive Adsorption on Low Rank Coal Vitrinite[J].Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys, 2017:10.1039.

- Dong, K.; Zhai, Z.; Jia, B. Swelling Characteristics and Interaction Mechanism of High-Rank Coal during CO2 Injection: A Molecular Simulation Study. ACS Omega 2022, 7, 6911–6923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiang, J.-H.; Zeng, F.-G.; Li, B.; Zhang, L.; Li, M.-F.; Liang, H.-Z. Construction of macromolecular structural model of anthracite from Chengzhuang coal mine and its molecular simulation. J. Fuel Chem. Technol. 2013, 41, 391–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Li, W.; Xiang, J.; Wang, Y.; Li, J.; Zeng, F. Molecular simulation of methane adsorption in shale based on grand canonical Monte Carlo method and pore size distribution. J. Nat. Gas Sci. Eng. 2016, 30, 119–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Pan, J.N.; Wang, E.L.; Hou, Q.L; Yang, Y.; Wang, X. Potential impact of CO2 injection into coal matrix in molecular terms. Chem. Eng. J. 2020, 401, 126071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, T.; Wang, C.; Hong, D. Programmable heating and quenching for enhancing coal pyrolysis tar yield: A ReaxFF molecular dynamics study. Energy 2023, 285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, Y.; Zhong, W.Q.; Yu, A.B. The molecular dynamics simulation of lignite combustion process in O2/CO2 atmosphere with ReaxFF force field. Powder Technol. 2022, 410, 117837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).