Submitted:

11 July 2023

Posted:

13 July 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Coal samples and methods

2.1. Experimental

2.1.1. Low-rank Coal sample preparation

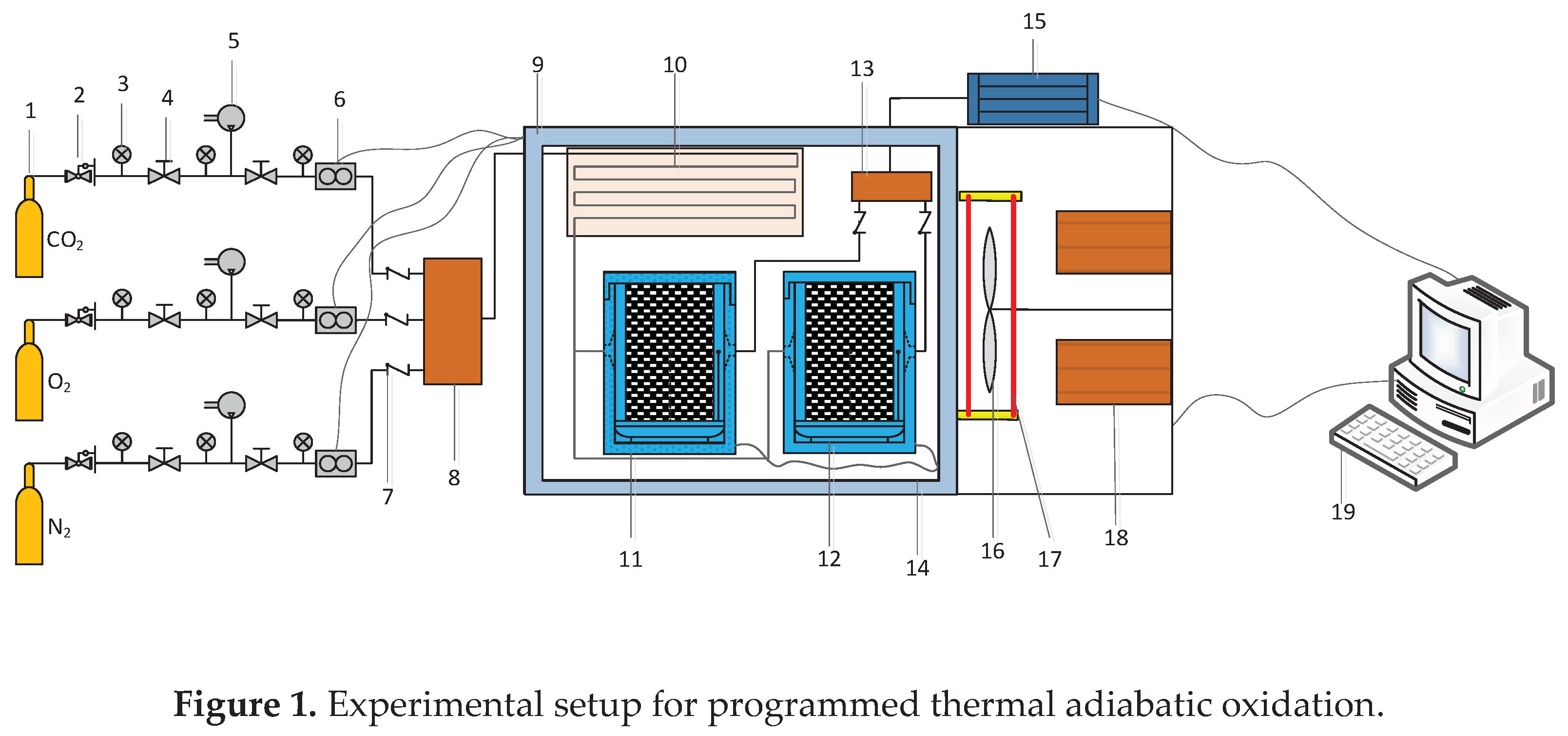

2.1.2. Device and process of temperature-programmed adiabatic oxidation experiment

2.1.3. Device and process of in situ infrared cooling experiment

2.2. Simulation method

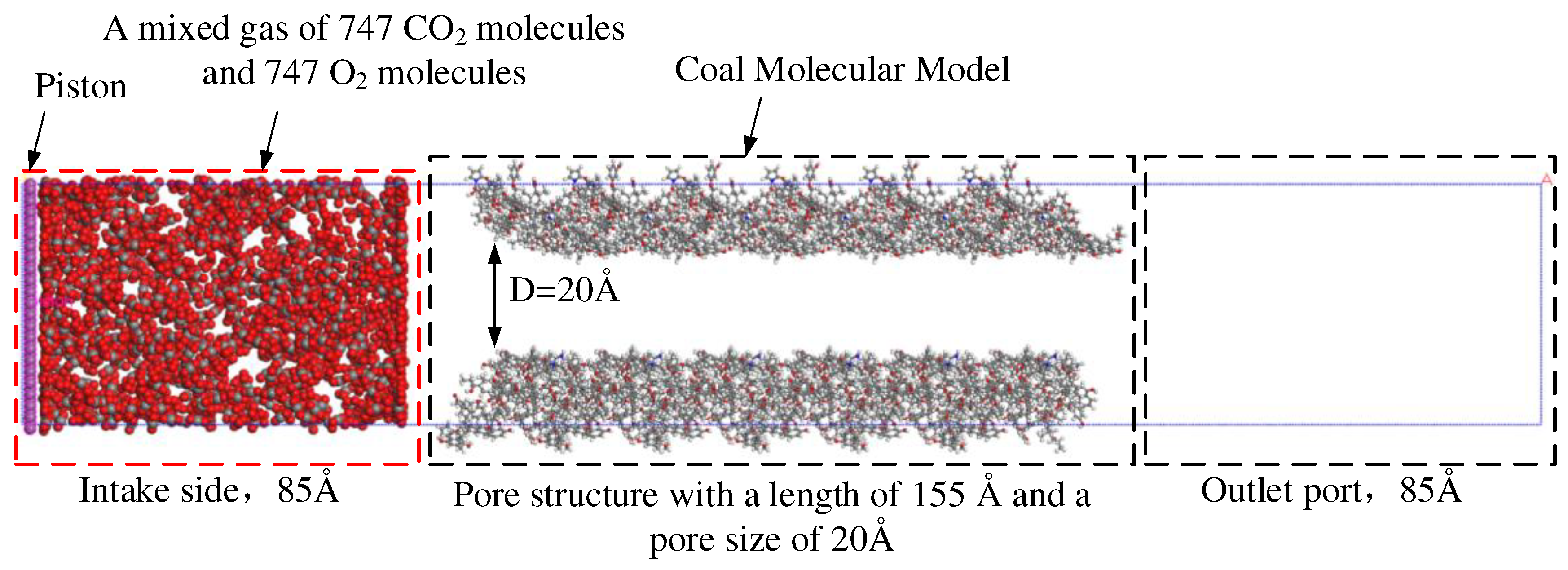

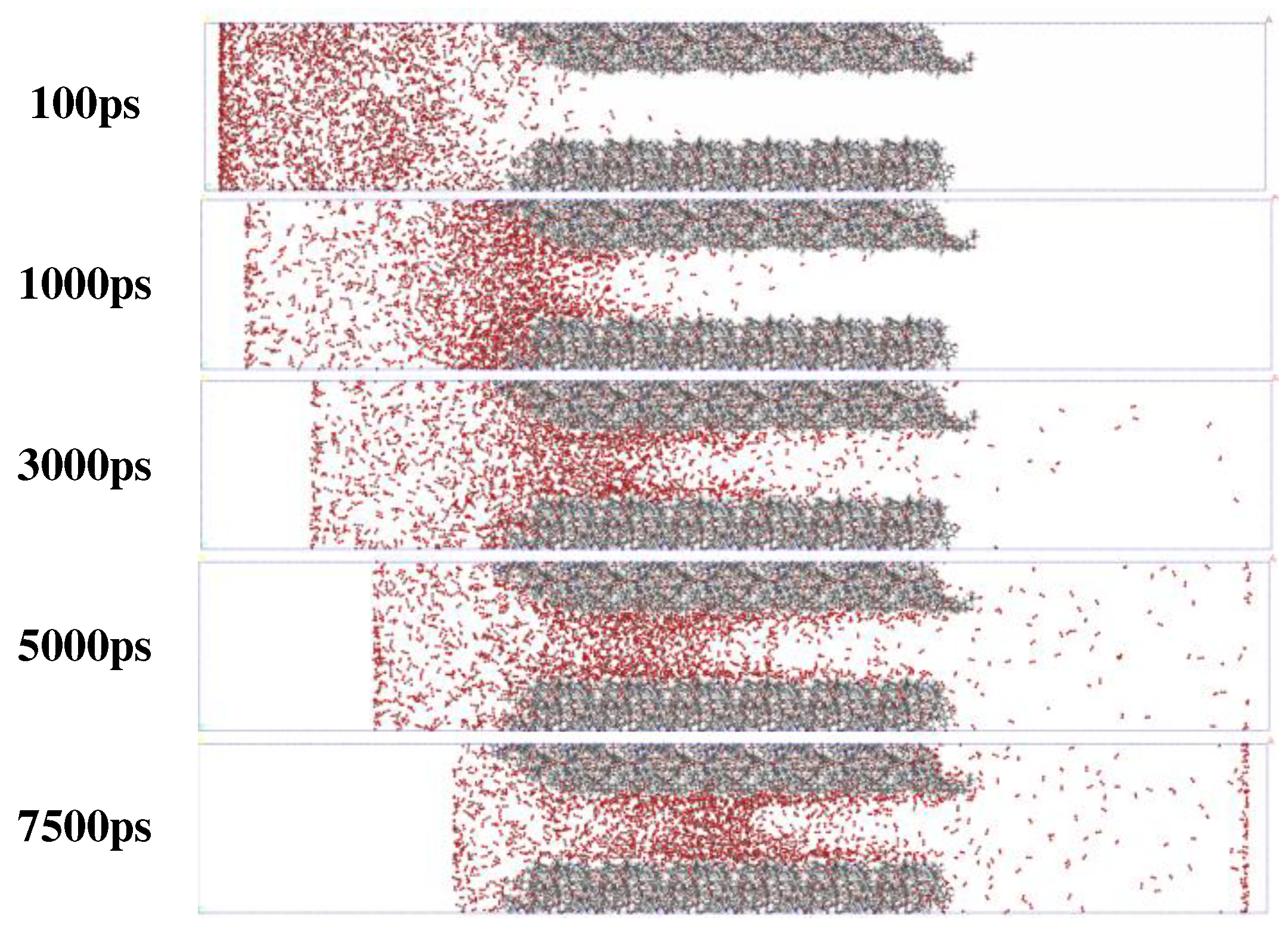

2.2.1. Simulation of Competitive Adsorption of CO2 and O2 in Coal Surface Pores

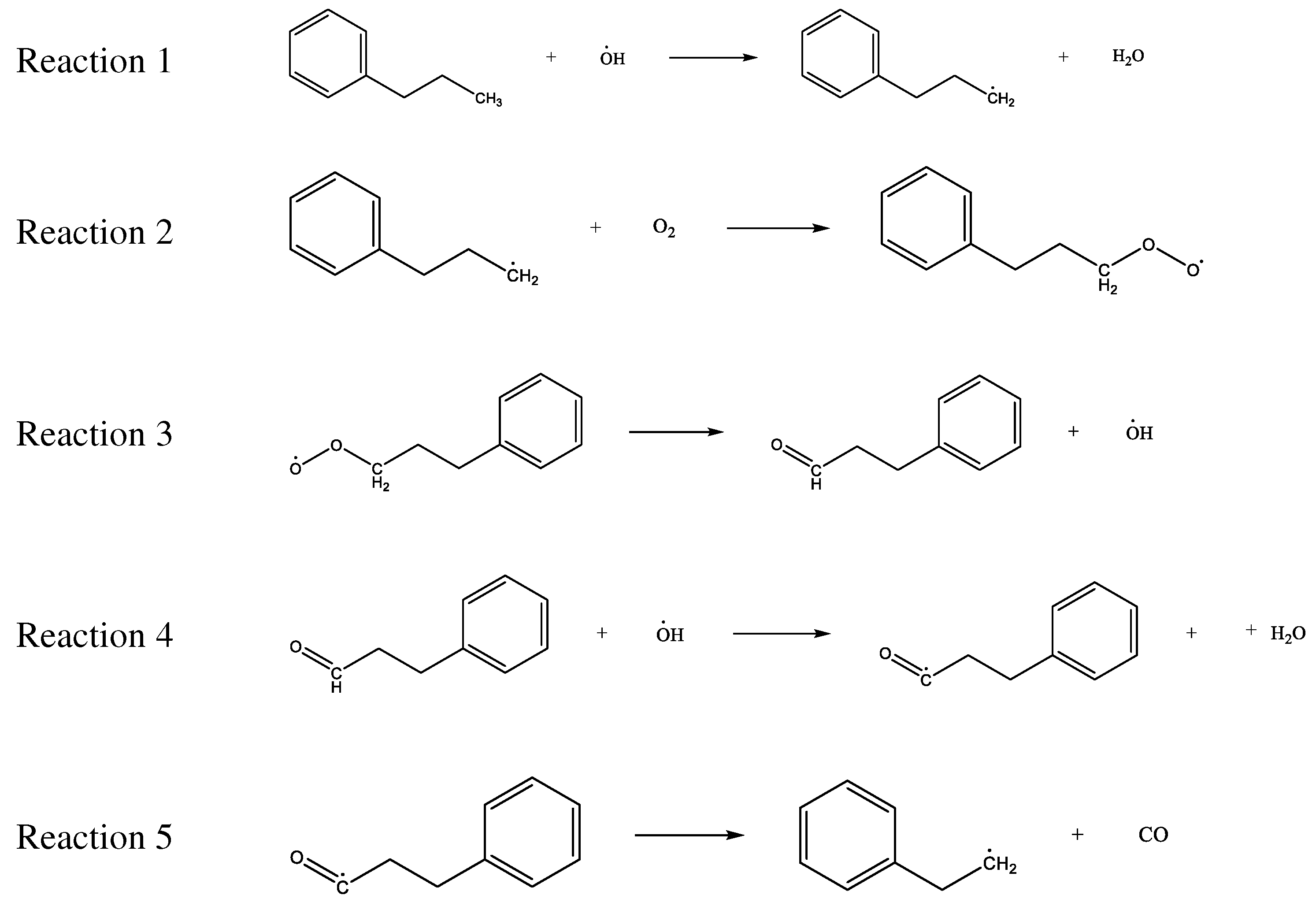

2.2.2. Chain Reaction Simulation of Coal Chemisorption of Oxygen

3. Results and analysis

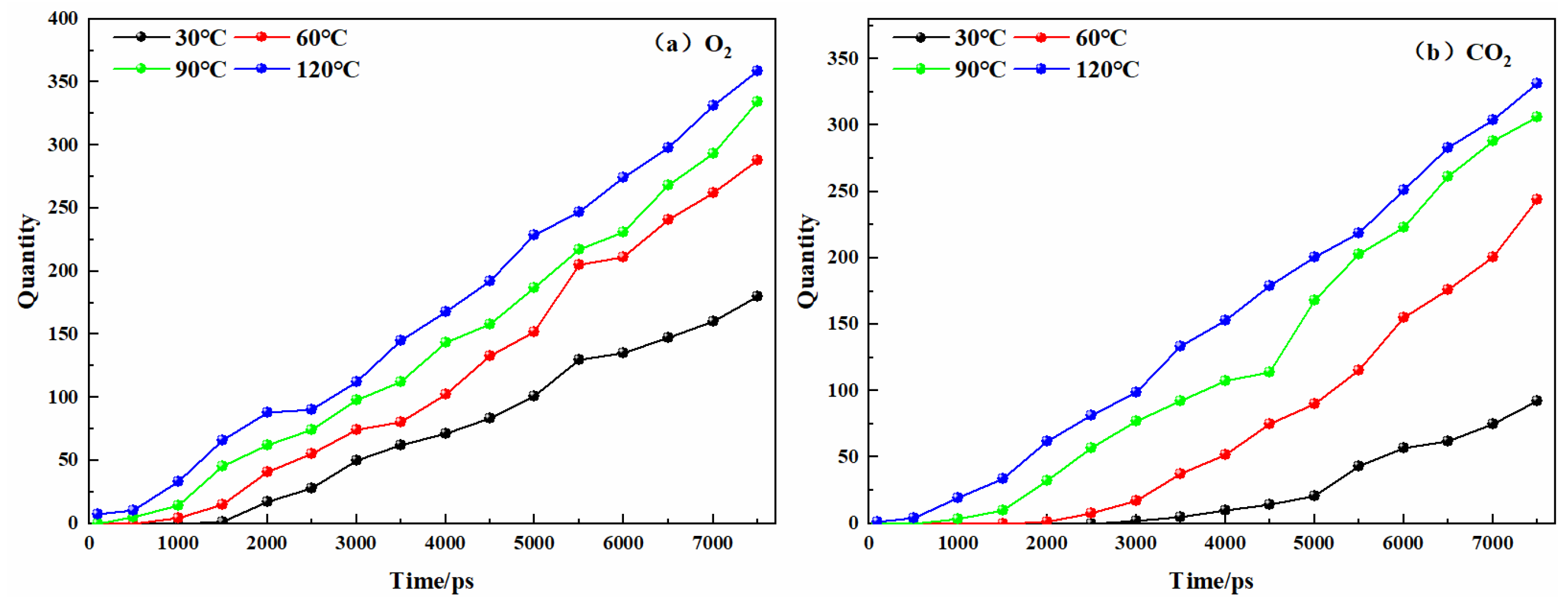

3.1. Analysis on the Physical Mechanism of CO2 Preventing O2 Adsorption

3.2. Analysis on the Chemical Mechanism of CO2 Preventing O2 Adsorption

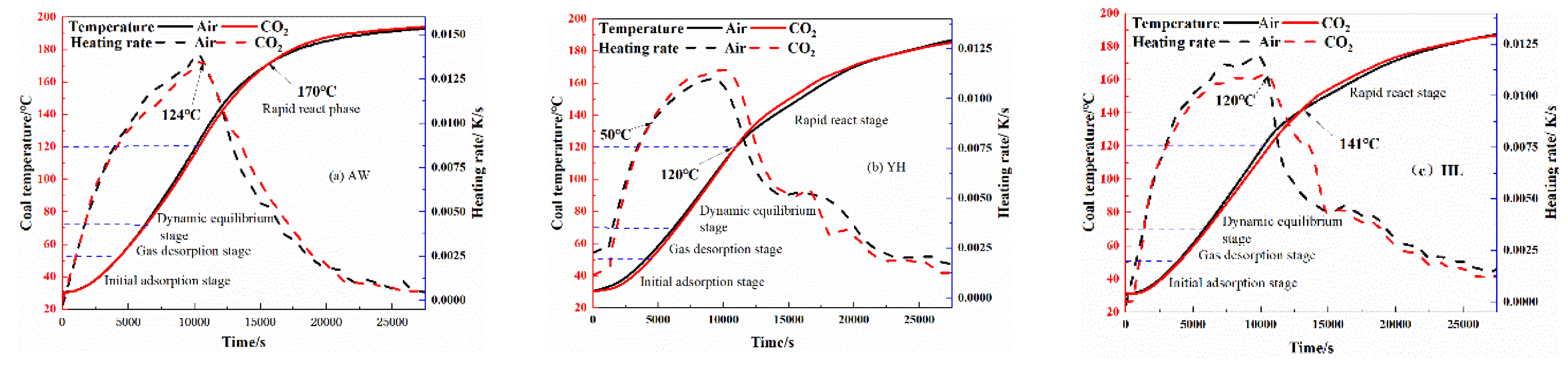

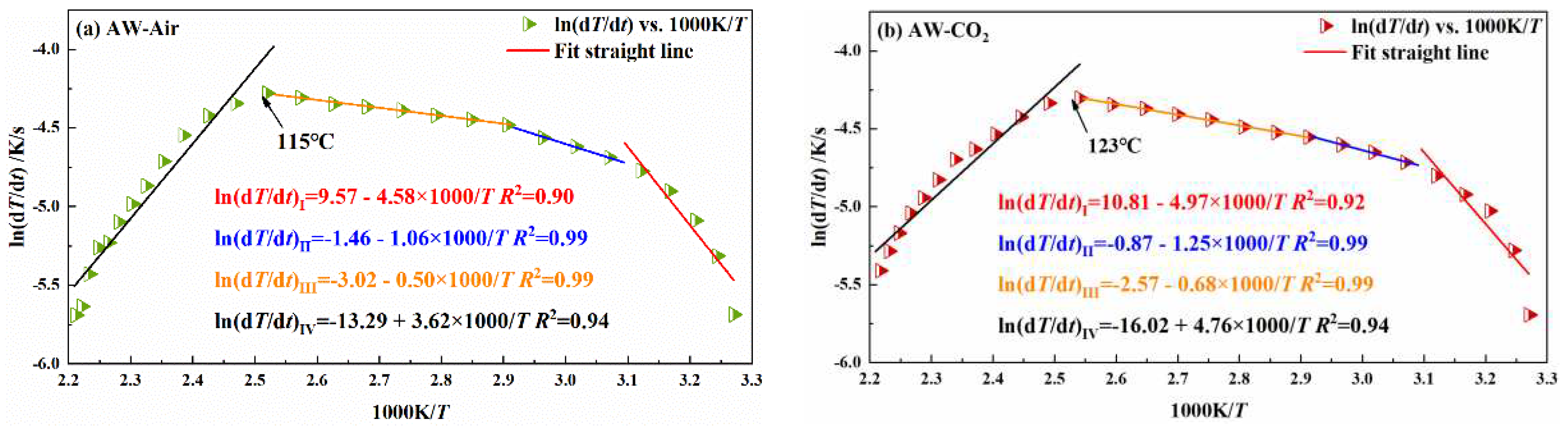

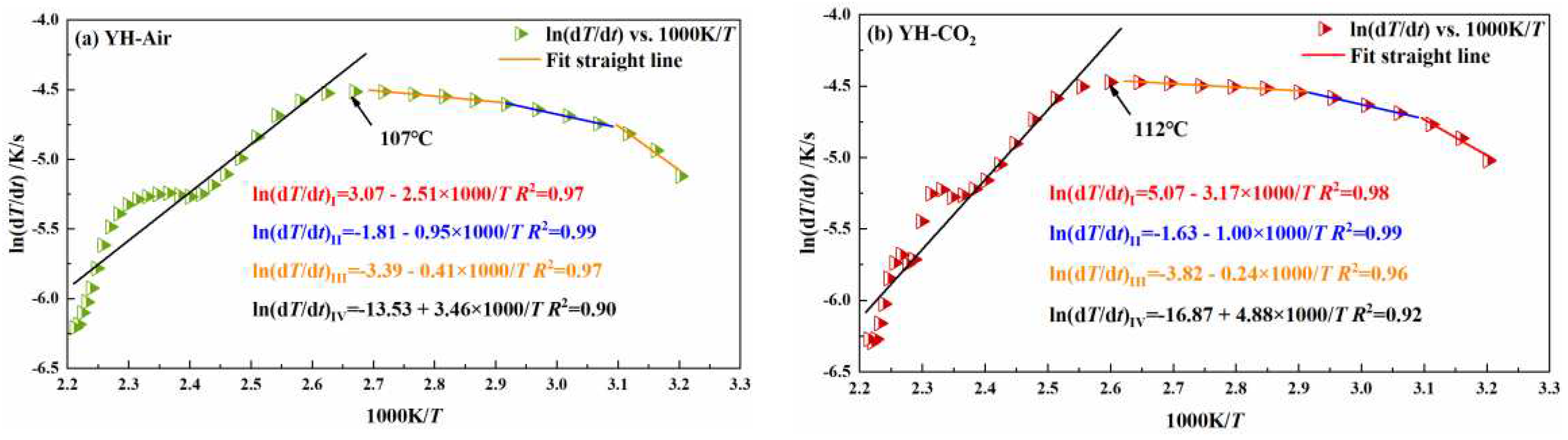

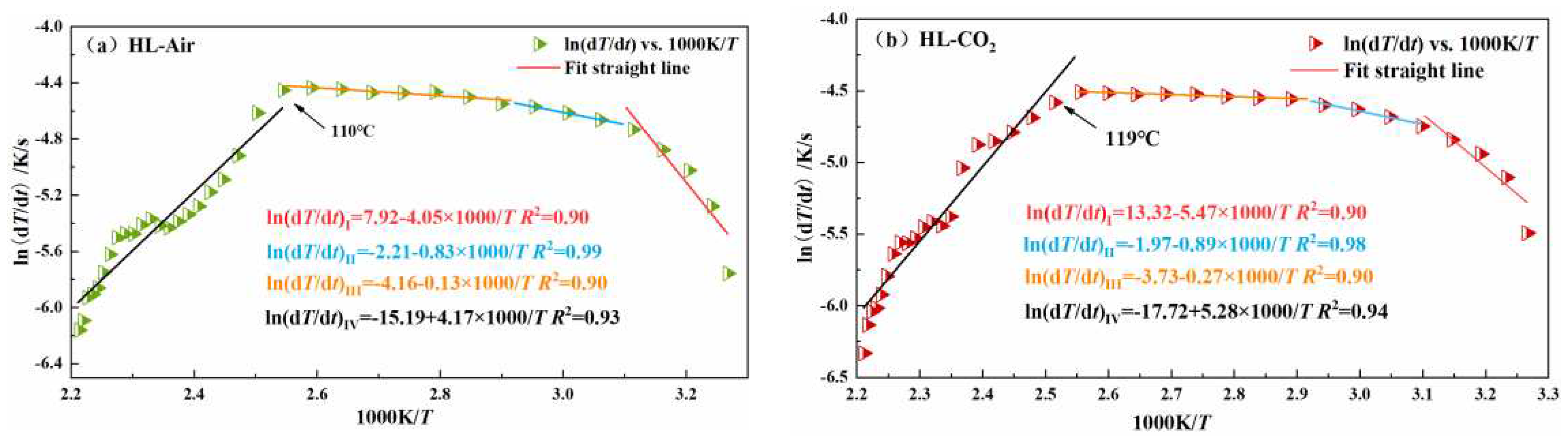

3.2.1. Influence of pre-injection of CO2 into coal on its heating process

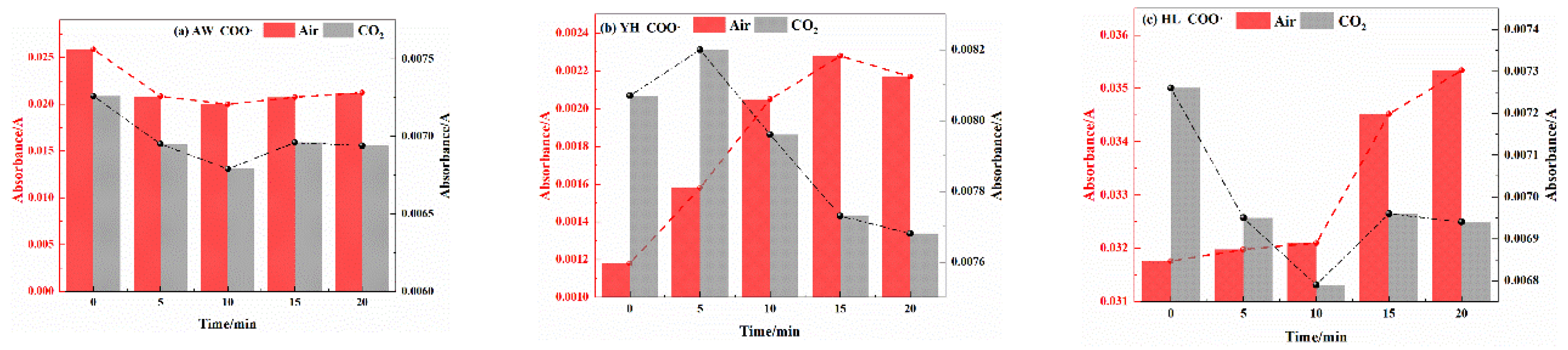

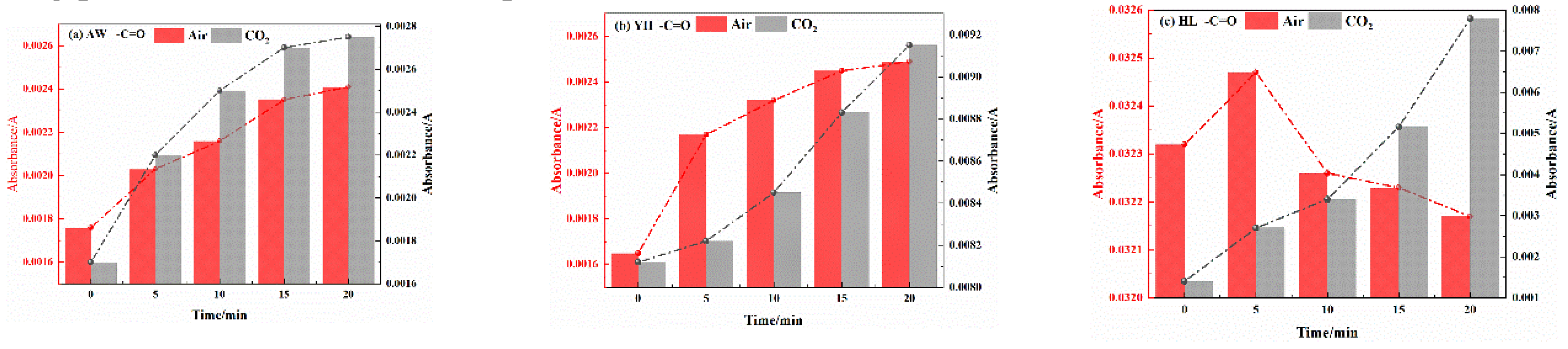

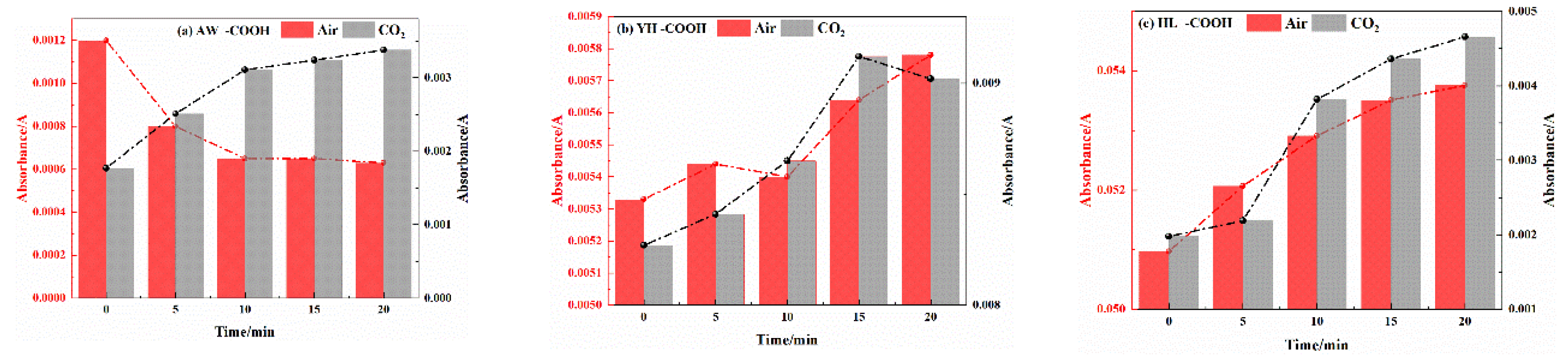

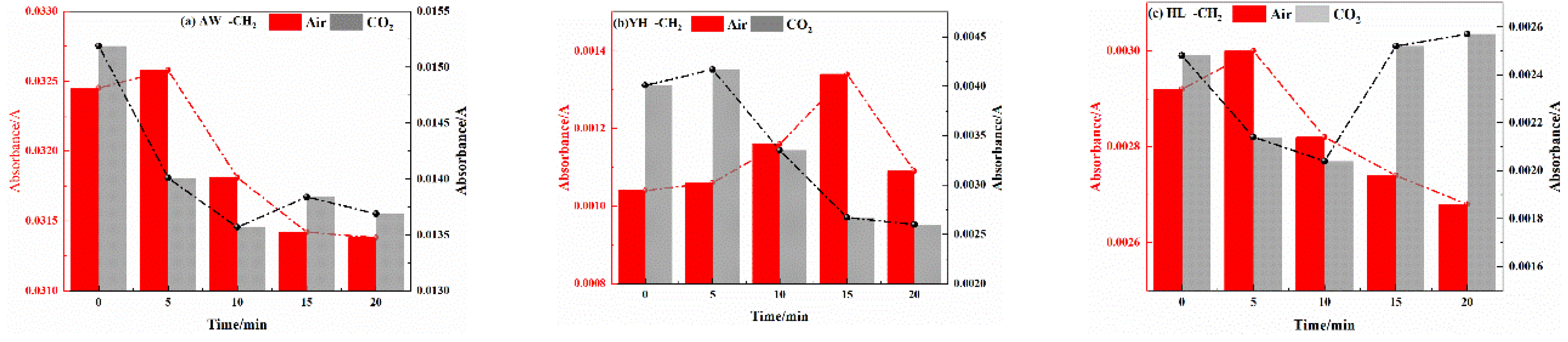

3.2.2. Analysis of Functional Group Changes of CO2 Injection During Coal Cooling

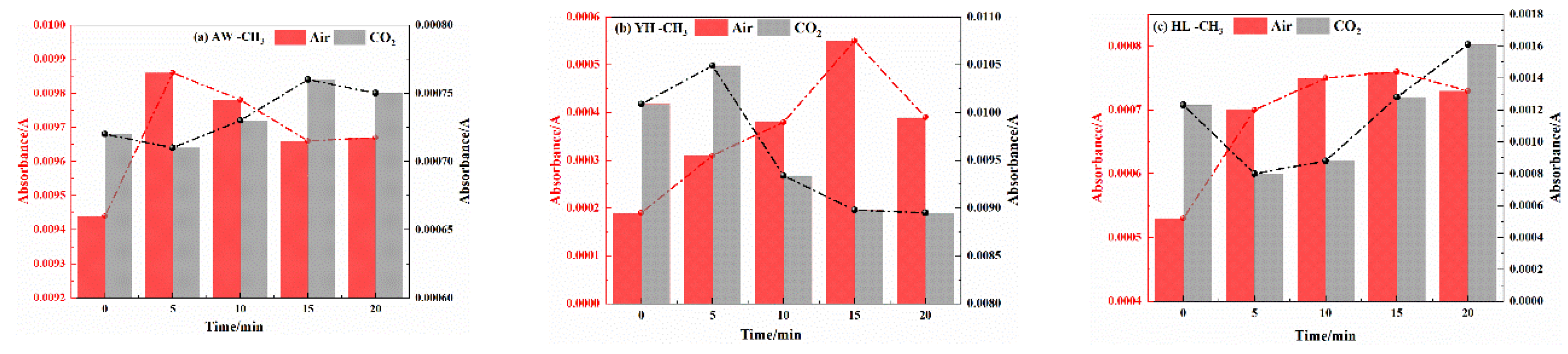

3.2.3. Effect of CO2 on the Reaction Process of Coal Chemical Adsorption of O2

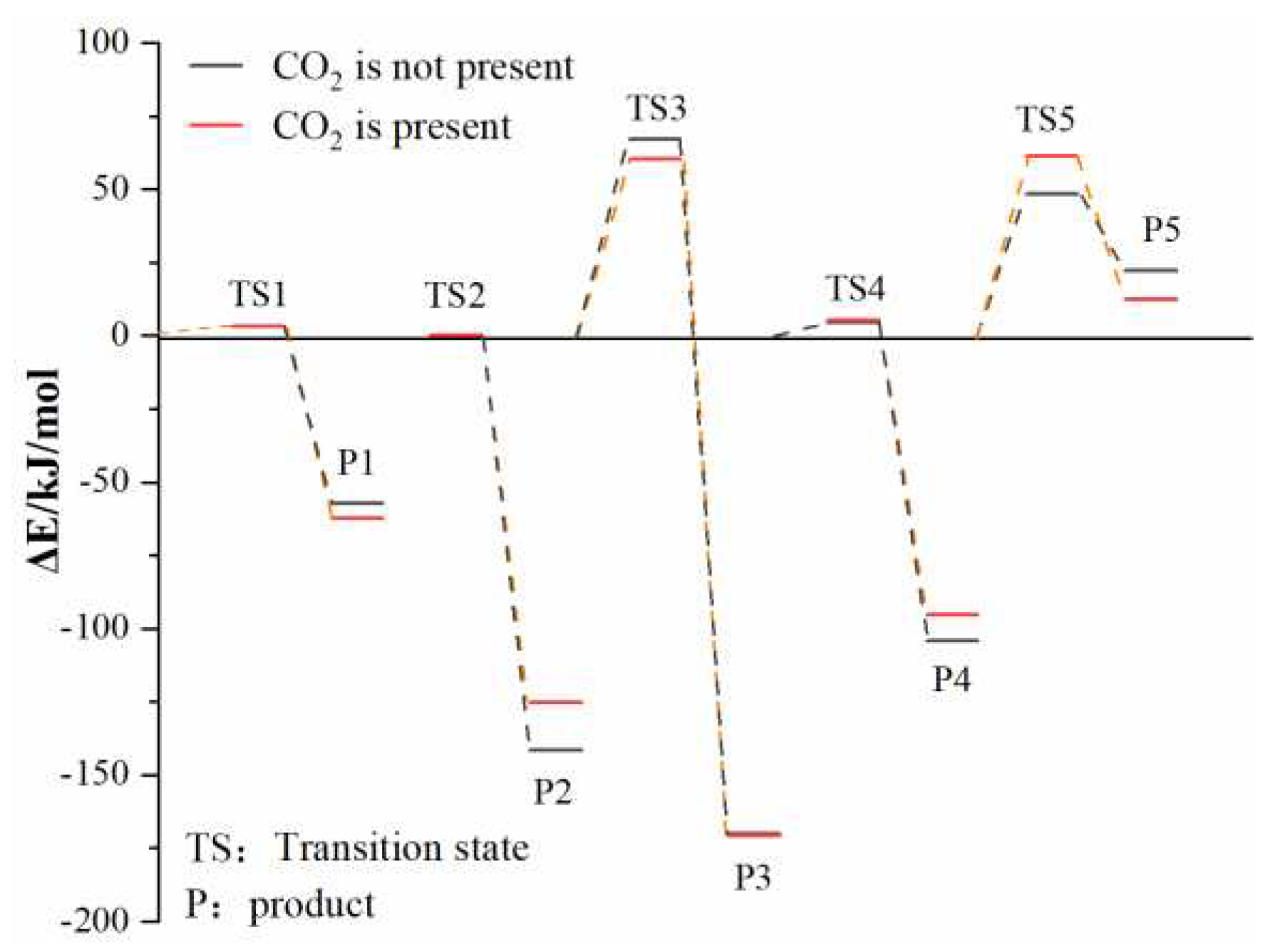

3.3. Construction of the Model of CO2 Preventing O2 Adsorption

4. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Song, Z. , et al., Analysis of coal fire dynamics in the Wuda syncline impacted by fire-fighting activities based on in-situ observations and Landsat-8 remote sensing data. International Journal of Coal Geology, 2015. 141-142: p. 91-102. [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Wang, Y.; Yan, S.; Zhao, F.; Li, Y.; Dang, L.; Liu, X.; Shao, Y.; Peng, B. Underground Coal Fire Detection and Monitoring Based on Landsat-8 and Sentinel-1 Data Sets in Miquan Fire Area, XinJiang. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, B. , Zhang, F., Zhang, Q. et al. Firefighting of subsurface coal fires with comprehensive techniques for detection and control: a case study of the Fukang coal fire in the Xinjiang region of China. Environ Sci Pollut Res 26, 29570–29584 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Wang, T. , et al., A spatio-temporal temperature-based thresholding algorithm for underground coal fire detection with satellite thermal infrared and radar remote sensing. International Journal of Applied Earth Observation and Geoinformation, 2022. 110: p. 102805. [CrossRef]

- Song, Z. and C. Kuenzer, Coal fires in China over the last decade: A comprehensive review. International Journal of Coal Geology, 2014. 133: p. 72-99. [CrossRef]

- Shao Z, Jia X, Zhong X, Wang D, Wei J, Wang Y, Chen L. Detection,extinguishing, and monitoring of a coal fire in Xinjiang, China. Environ SciPollut Res Int. 2018 Sep;25(26):26603-26616. [CrossRef]

- Ge Shirong, Guo Guangli and Wang Yuehan. “Mining Science and Technology : Proceedings of the 5th International Symposium on Mining Science and Technology, Xuzhou, China 20-22 October 2004.

- Wang, H., B. Z. Dlugogorski and E.M. Kennedy, Kinetic modeling of low-temperature oxidation of coal. Combustion and Flame, 2002. 131(4): p. 452-464. [CrossRef]

- Tan, B. , Cheng, G., Zhu, X. et al. Experimental Study on the Physisorption Characteristics of O2 in Coal Powder are Effected by Coal Nanopore Structure. Sci Rep 10, 6946 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Grant G. Karsner, Daniel D. Perlmutter, Model for coal oxidation kinetics. 1. Reaction under chemical control [J], Fuel, 1982, 29-34. [CrossRef]

- Wang, H., B. Z. Dlugogorski and E.M. Kennedy, Coal oxidation at low temperatures: oxygen consumption, oxidation products, reaction mechanism and kinetic modelling. Progress in Energy and Combustion Science, 2003. 29(6): p. 487-513. [CrossRef]

- Xue, D. , et al., Carbon dioxide sealing-based inhibition of coal spontaneous combustion: A temperature-sensitive micro-encapsulated fire-retardant foamed gel. Fuel, 2020. 266: p. 117036. [CrossRef]

- Liu Y, Wen H, Guo J, et al. Coal spontaneous combustion and N2 suppression in triple goafs: A numerical simulation and experimental study[J]. Fuel, 2020,271:117625.

- Zhang, Y.; Xu, J.; Wang, D. Experimental Study on the Inhibition Effects of Nitrogen and Carbon Dioxide on Coal Spontaneous Combustion. Energies 2020, 13, 5256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Jun & Ren, Li-Feng & Ma, Li & Qin, Xiao-Yang & Wang, Wei-Feng & Liu, Chang-Chun. (2019). Low-temperature oxidation and reactivity of coal in O2/N2 and O2/CO2 atmospheres, a case of carboniferous–permian coal in Shaanxi, China. Environmental Earth Sciences. [CrossRef]

- Reza Khatami, Chris Stivers, Yiannis A. Levendis, Ignition characteristics of single coal particles from three different ranks in O2/N2 and O2/CO2 atmospheres [J], Combustion and Flame, 2012, 3554-3568. [CrossRef]

- Wang F, Liu H W. Comparative experiment study on fire prevention and extinguishing in goaf by N-2-water mist and CO2-water mist[J]. ARABIAN JOURNAL OF GEOSCIENCES, 2020,13(17).

- Liu W, Chu X Y, Xu H, et al. Oxidation reaction constants for coal spontaneous combustion under inert gas environments: An experimental investigation[J]. ENERGY, 2022,247.

- Su H T, Kang N, Shi B B, et al. Simultaneous thermal analysis on the dynamical oxygen-lean combustion behaviors of coal in a O-2/N-2/CO2 atmosphere[J]. JOURNAL OF THE ENERGY INSTITUTE, 2021,96:128-139.

- Liu H W, Wang F. Thermal characteristics and kinetic analysis of coal-oxygen reaction under the condition of inert gas[J]. INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF COAL PREPARATION AND UTILIZATION, 2022,42(3):846-862.

- Wu L, Qiao Y, Yao H. Experimental and numerical study of pulverized bituminous coal ignition characteristics in O2/N2 and O2/CO2 atmospheres[J]. ASIA-PACIFIC JOURNAL OF CHEMICAL ENGINEERING, 2012,7:S195-S200.

- Li, Q. , et al., Properties of char particles obtained under O2/N2 and O2/CO2 combustion environments. Chemical Engineering and Processing: Process Intensification, 2010. 49(5): p. 449-459.

- Ma, L. , et al., Micro-characteristics of low-temperature coal oxidation in CO2/O2 and N2/O2 atmospheres. Fuel, 2019. 246: p. 259-267.

- Zhou B Z, Yang S Q, Yang W M, et al. Variation characteristics of active groups and macroscopic gas products during low-temperature oxidation of coal under the action of inert gases N-2 and CO2[J]. FUEL, 2022,307.

- Wu, S., Z. Jin and C. Deng, Molecular simulation of coal-fired plant flue gas competitive adsorption and diffusion on coal. Fuel, 2019. 239: p. 87-96. [CrossRef]

- Zhang J, Wang J, Zhang C, et al. Molecular simulation of gases competitive adsorption in lignite and analysis of original CO desorption[J]. Scientific Reports, 2021,11(1).

- Long H, Lin H F, Yan M, et al. Adsorption and diffusion characteristics of CH4, CO2, and N2 in micropores and mesopores of bituminous coal: Molecular dynamics[J]. FUEL, 2021,292.

- Dong, X. , et al., Investigation of Competitive Adsorption Properties of CO/CO2/O2 onto the Kailuan Coals by Molecular Simulation. ACS Omega, 2022. 7.

- Liu Y, Fu P F, Bie K, et al. The intrinsic reactivity of coal char conversion compared under different conditions of O2/CO2, O-2/H2O and air atmospheres[J]. JOURNAL OF THE ENERGY INSTITUTE, 2020,93(5):1883-1891.

- Liu, M. , et al., 3-D simulation of gases transport under condition of inert gas injection into goaf. Heat and Mass Transfer, 2016. 52(12): p. 2723-2734. [CrossRef]

- Yan Fazhi, Xu Jiang, Peng Shoujian, et al. Breakdown process and fragmentation characteristics of anthracite subjected to high-voltage electrical pulses treatment[J]. Fuel, 2020,275(C).

- Yan Fazhi, Xu Jiang, Lin Baiquan, et al. Changes in pore structure and permeability of anthracite coal before and after high-voltage electrical pulses treatment[J]. Powder Technology, 2019,343.

- Ren J G, Song Z M, Li B, et al. Structure feature and evolution mechanism of pores in different metamorphism and deformation coals[J]. FUEL, 2021,283.

- Fu, S. , et al., Study of Adsorption Characteristics of CO2, O2, and N2 in Coal Micropores and Mesopores at Normal Pressure. Industrial & Engineering Chemistry Research, 2022.

- Cheng Gang, Tan Bo, Zhang Zhaolun, Fu Shuhui, Wang Haiyan, Wang Feiran, Characteristics of coal-oxygen chemisorption at the low-temperature oxidation stage: DFT and experimental study, Fuel, 2022,123120. [CrossRef]

| Coal sample | Mad | Ad | Vdaf | FCad | Cdaf | Hdaf | Ndaf | Odaf | St,ad/% | Ro, ran/% |

| HL | 14.35 | 6.92 | 42.46 | 36.27 | 73.29 | 5.16 | 1.06 | 19.22 | 1.27 | 0.35 |

| YH | 4.67 | 6.18 | 38.09 | 51.06 | 81.92 | 5.24 | 0.93 | 9.32 | 2.68 | 0.58 |

| AW | 0.82 | 8.73 | 35.82 | 54.63 | 86.25 | 5.91 | 1.13 | 6.37 | 0.34 | 0.78 |

| Notes:Mad- moisture;Ad- Ash,Vdaf - Volatile,FCad- Fixed carbon;Cdaf- Carbon content,Hdaf- Hydrogen content,Ndaf- Nitrogen content,Odaf- Oxygen content,St,ad- Sulfur content; Ro, ran- Vitrinite Reflectance | ||||||||||

| coal sample | oxidation stage | Inject Air | Inject CO2 | ||

| activation energy Ea /kJ/mol | critical temperature of spontaneous combustionT /℃ | activation energyEa /kJ/mol | critical temperature of spontaneous combustionT /℃ | ||

| AW | I | 38.08 | 115 | 41.32 | 123 |

| II | 8.81 | 10.39 | |||

| III | 4.16 | 5.65 | |||

| IV | -30.10 | -39.58 | |||

| YH | I | 20.87 | 107 | 26.36 | 112 |

| II | 7.90 | 8.32 | |||

| III | 3.41 | 2.00 | |||

| IV | -28.77 | -40.57 | |||

| HL | I | 33.67 | 110 | 47.72 | 119 |

| II | 6.90 | 7.40 | |||

| III | 1.08 | 2.25 | |||

| IV | -34.67 | -43.90 | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).