Submitted:

03 May 2024

Posted:

09 May 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Computational Details

3. Results and Discussion

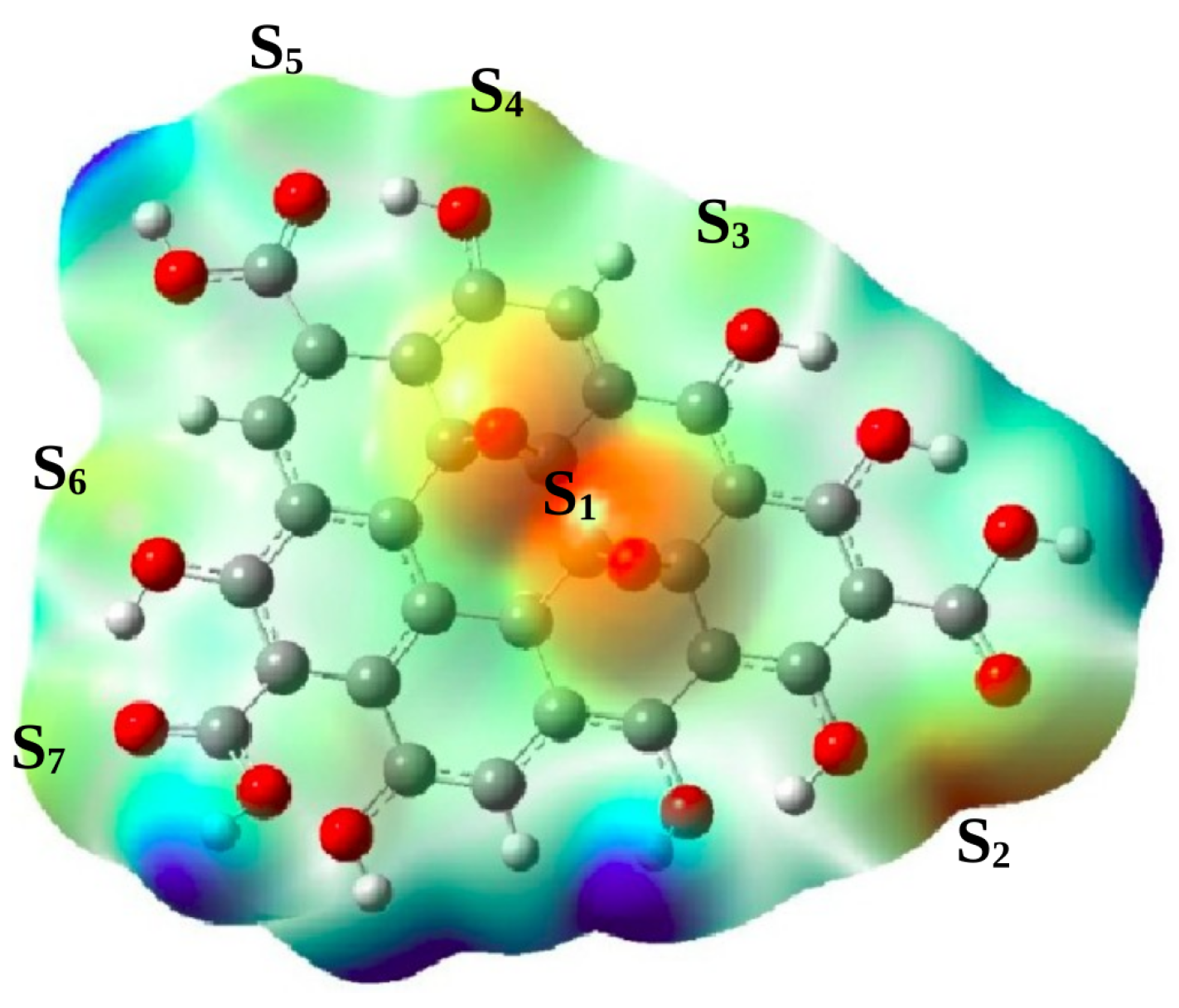

3.1. Stability and Reactivity of GO Nanoparticle

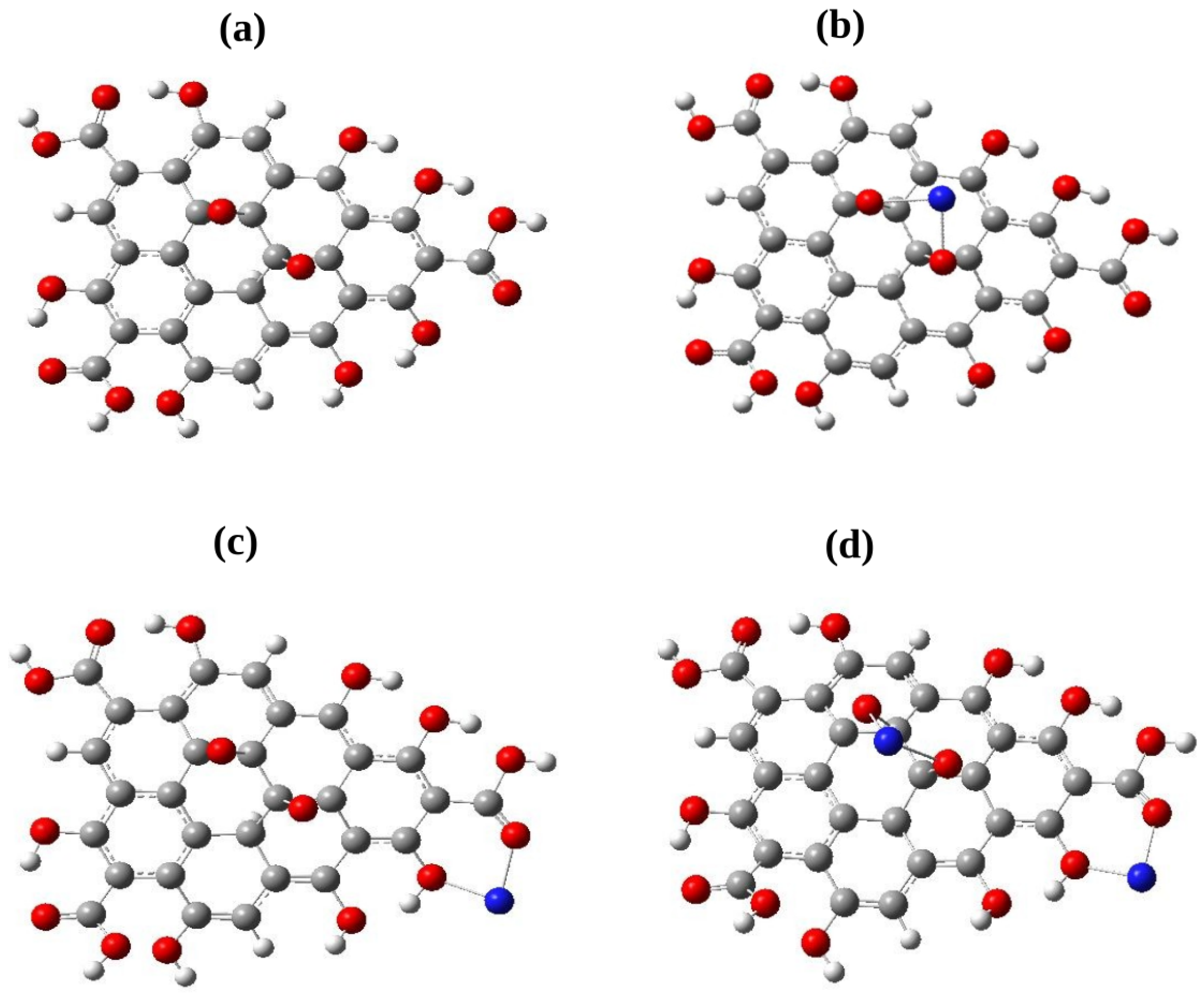

3.2. Adsorption of Pb and Cd

| Site | Structure | (eV) | (eV) | (eV) | (eV) | (eV) | (eV) | |

| GO | − | − | − | |||||

| GO-Pb | ||||||||

| GO-Cd | ||||||||

| S | GO-Pb | |||||||

| GO-Cd | ||||||||

| GO-Pb | ||||||||

| S | GO-Cd | |||||||

| GO-Pb | ||||||||

| GO-Cd |

4. Summary and Conclusions

Acknowledgments

References

- Yang, S.; Chen, C.; Chen, Y.; Li, J.; Wang, D.; Wang, X.; Hu, W. Competitive adsorption of PbII, NiII, and SrII ions on graphene oxides: a combined experimental and theoretical study. ChemPlusChem 2015, 80, 480–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jalilian, R.; Jauregui, L.A.; Lopez, G.; Tian, J.; Roecker, C.; Yazdanpanah, M.M.; Cohn, R.W.; Jovanovic, I.; Chen, Y.P. Scanning gate microscopy on graphene: charge inhomogeneity and extrinsic doping. Nanotechnology 2011, 22, 295705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kabata-Pendias, A.; Mukherjee, A.B. Humans; Springer, 2007.

- Boukhvalov, D.W.; Katsnelson, M.I. Modeling of graphite oxide. Journal of the American Chemical Society 2008, 130, 10697–10701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Liu, Y.; Pang, H.; Yu, S.; Ai, Y.; Ma, X.; Song, G.; Hayat, T.; Alsaedi, A.; Wang, X. Effect of graphene oxide surface modification on the elimination of Co (II) from aqueous solutions. Chemical Engineering Journal 2018, 344, 380–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, Q.; Wei, J.; Hu, Y.; Wei, C. Fabrication of terminal amino hyperbranched polymer modified graphene oxide and its prominent adsorption performance towards Cr (VI). Journal of hazardous materials 2019, 363, 161–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kong, Q.; Wei, C.; Preis, S.; Hu, Y.; Wang, F. Facile preparation of nitrogen and sulfur co-doped graphene-based aerogel for simultaneous removal of Cd2+ and organic dyes. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 2018, 25, 21164–21175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, S.; Wang, X.; Yao, W.; Wang, J.; Ji, Y.; Ai, Y.; Alsaedi, A.; Hayat, T.; Wang, X. Macroscopic, spectroscopic, and theoretical investigation for the interaction of phenol and naphthol on reduced graphene oxide. Environmental Science & Technology 2017, 51, 3278–3286. [Google Scholar]

- Kong, Q.; Preis, S.; Li, L.; Luo, P.; Wei, C.; Li, Z.; Hu, Y.; Wei, C. Relations between metal ion characteristics and adsorption performance of graphene oxide: A comprehensive experimental and theoretical study. Separation and Purification Technology 2020, 232, 115956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Feng, H.; Li, J. Graphene oxide: preparation, functionalization, and electrochemical applications. Chemical reviews 2012, 112, 6027–6053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, D.; Zhang, L.; Siebold, D.; DeArmond, D.; Alvarez, N.T.; Shanov, V.N.; Heineman, W.R. Electrochemical studies of three dimensional graphene foam as an electrode material. Electroanalysis 2017, 29, 1506–1512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gandhi, M.R.; Vasudevan, S.; Shibayama, A.; Yamada, M. Graphene and graphene-based composites: A rising star in water purification-a comprehensive overview. ChemistrySelect 2016, 1, 4358–4385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, W.; Li, H.; Liu, Y.; Song, S. A review on heavy metal ions adsorption from water by graphene oxide and its composites. Journal of Molecular Liquids 2017, 230, 496–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, Y.; Xu, J.; Zhu, X.; Duan, X.; Lu, L.; Yu, Y. Graphene-derived nanomaterials as recognition elements for electrochemical determination of heavy metal ions: a review. Microchimica Acta 2019, 186, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dimiev, A.M.; Eigler, S. Graphene oxide: fundamentals and applications; John Wiley & Sons, 2016.

- Kong, Q.; Shi, X.; Ma, W.; Zhang, F.; Yu, T.; Zhao, F.; Zhao, D.; Wei, C. Strategies to improve the adsorption properties of graphene-based adsorbent towards heavy metal ions and their compound pollutants: A review. Journal of Hazardous Materials 2021, 415, 125690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kong, Q.; Shi, X.; Ma, W.; Zhang, F.; Yu, T.; Zhao, F.; Zhao, D.; Wei, C. Strategies to improve the adsorption properties of graphene-based adsorbent towards heavy metal ions and their compound pollutants: A review. Journal of Hazardous Materials 2021, 415, 125690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sitko, R.; Turek, E.; Zawisza, B.; Malicka, E.; Talik, E.; Heimann, J.; Gagor, A.; Feist, B.; Wrzalik, R. Adsorption of divalent metal ions from aqueous solutions using graphene oxide. Dalton transactions 2013, 42, 5682–5689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhang, L.; Huang, H.; Hu, J.; Shah, S.M.; Su, X. Adsorption and removal of tetracycline antibiotics from aqueous solution by graphene oxide. Journal of colloid and interface science 2012, 368, 540–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elgengehi, S.M.; El-Taher, S.; Ibrahim, M.A.; Desmarais, J.K.; El-Kelany, K.E. Graphene and graphene oxide as adsorbents for cadmium and lead heavy metals: A theoretical investigation. Applied Surface Science 2020, 507, 145038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hattab, A.H.; Tapabashi, N.O.; Khalil, N.J. Density Functional Theory calculations for Graphene Oxide, Zinc Oxide and Graphene oxide/zinc oxide composite structure 2023.

- Frisch, M.; Trucks, G.; Schlegel, H.; Scuseria, G.; Robb, M.; Cheeseman, J.; Scalmani, G.; Barone, V.; Petersson, G.; Nakatsuji, H.; others. Gaussian 16 Revision C. 01. 2016; Gaussian Inc. Wallingford CT 2016, 421. [Google Scholar]

- Albertsen, J.; Knudsen, J.; Roy-Poulsen, N.; Vistisen, L. Meteorites and thermodynamic equilibrium in fcc iron-nickel alloys (25-50% Ni). Physica Scripta 1980, 22, 171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Spanos, G.; Shiflet, G.; Aaronson, H. Mechanisms of the bainite (non-lamellar eutectoid) reaction and a fundamental distinction between the bainite and pearlite (lamellar eutectoid) reactions. Acta Metallurgica 1988, 36, 1129–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, U.; Roy, D.; Chattaraj, P.; Parthasarathi, R.; Padmanabhan, J.; Subramanian, V. A conceptual DFT approach towards analysing toxicity. Journal of Chemical Sciences 2005, 117, 599–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frau, J.; Muñoz, F.; Glossman-Mitnik, D. A molecular electron density theory study of the chemical reactivity of cis-and trans-resveratrol. Molecules 2016, 21, 1650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chandrakumar, K.; Pal, S. The concept of density functional theory based descriptors and its relation with the reactivity of molecular systems: A semi-quantitative study. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2002, 3, 324–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armaković, S.; Armaković, S.J.; Abramović, B.F. Theoretical investigation of loratadine reactivity in order to understand its degradation properties: DFT and MD study. Journal of molecular modeling 2016, 22, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koopmans, T. Über die Zuordnung von Wellenfunktionen und Eigenwerten zu den einzelnen Elektronen eines Atoms. physica 1934, 1, 104–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukui, K. Role of frontier orbitals in chemical reactions. science 1982, 218, 747–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhary, V.; Bhatt, A.; Dash, D.; Sharma, N. DFT calculations on molecular structures, HOMO–LUMO study, reactivity descriptors and spectral analyses of newly synthesized diorganotin (IV) 2-chloridophenylacetohydroxamate complexes. Journal of computational chemistry 2019, 40, 2354–2363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aihara, J.i. Reduced HOMO- LUMO gap as an index of kinetic stability for polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons. The Journal of Physical Chemistry A 1999, 103, 7487–7495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aihara, J.i. Weighted HOMO-LUMO energy separation as an index of kinetic stability for fullerenes. Theoretical Chemistry Accounts 1999, 102, 134–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshida, M.; Aihara, J.i. Validity of the weighted HOMO–LUMO energy separation as an index of kinetic stability for fullerenes with up to 120 carbon atoms. Physical Chemistry Chemical Physics 1999, 1, 227–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parr, R.G.; Zhou, Z. Absolute hardness: unifying concept for identifying shells and subshells in nuclei, atoms, molecules, and metallic clusters. Accounts of chemical research 1993, 26, 256–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosar, B.; Albayrak, C. Spectroscopic investigations and quantum chemical computational study of (E)-4-methoxy-2-[(p-tolylimino) methyl] phenol. Spectrochimica Acta Part A: Molecular and Biomolecular Spectroscopy 2011, 78, 160–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miao, Z.; Li, S.; Priest, C.; Wang, T.; Wu, G.; Li, Q. Effective approaches for designing stable M–Nx/C oxygen-reduction catalysts for proton-exchange-membrane fuel cells. Advanced materials 2022, 34, 2200595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rocha, M.; Di Santo, A.; Arias, J.M.; Gil, D.M.; Altabef, A.B. Ab-initio and DFT calculations on molecular structure, NBO, HOMO–LUMO study and a new vibrational analysis of 4-(Dimethylamino) Benzaldehyde. Spectrochimica Acta Part A: Molecular and Biomolecular Spectroscopy 2015, 136, 635–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chattaraj, P.K.; Roy, D.R. Update 1 of: electrophilicity index. Chemical reviews 2007, 107, PR46–PR74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parr, R.; Szentpaly, L.; Liu, S. Electrophilicity Index. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 121 1922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leenaerts, O.; Partoens, B.; Peeters, F. Adsorption of Molecules on Graphene. Graphene Chemistry: Theoretical Perspectives, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.; Li, G.; Li, Q.; Shaikh, M.; Li, Z. The pure paramagnetism in graphene oxide. Results in Physics 2021, 26, 104407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perepichka, D.F.; Bryce, M.R. Molecules with exceptionally small HOMO-LUMO gaps. Angewandte Chemie International Edition 2005, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mulliken, R.S. Electronic population analysis on LCAO–MO molecular wave functions. I. The Journal of chemical physics 1955, 23, 1833–1840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legesse, M.; El Mellouhi, F.; Bentria, E.T.; Madjet, M.E.; Fisher, T.S.; Kais, S.; Alharbi, F.H. Reduced work function of graphene by metal adatoms. Applied Surface Science 2017, 394, 98–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levels, N.G. Ionization Energies for the Neutral Atoms. Data File on the Site http://physics. nist. gov/PhysRefData/IonEnergy/tblNew. html.

- Lide, D.R. CRC handbook of chemistry and physics; Vol. 85, CRC press, 2004.

- Shtepliuk, I.; Caffrey, N.M.; Iakimov, T.; Khranovskyy, V.; Abrikosov, I.A.; Yakimova, R. On the interaction of toxic Heavy Metals (Cd, Hg, Pb) with graphene quantum dots and infinite graphene. Scientific reports 2017, 7, 3934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Structure | Site | |||

| S | ||||

| S | ||||

| S | ||||

| GO | S | |||

| S | ||||

| S | ||||

| S |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).