Introduction

The giant anteater (

Myrmecophaga tridactyla) is the most prominent representative of the Myrmecophagidae family, belonging to the suborder Vermilingua, order Pilosa, and superorder Xenarthra, inhabiting Central and South America [

1]. The morphological study of these animals is surprising due to the apparent high plasticity of the musculoskeletal system, with a consequent disparity in their functional adaptations [

2]. Unfortunately, the animals that still exist in this superorder are little studied [

3].

M. tridactyla is an endangered animal listed in the vulnerable category on the IUCN/SSC Red List [

4]. Studies on this species are highly relevant for its preservation because the lack of morphological information [

5] makes it hard to describe diseases and interpret imaging exams. The risk of extinction is related to the habitat loss of these animals, mainly due to fires, which are often intentional to make room for crops and pastures, and urban sprawl, which impacts biodiversity and increases the risk of these animals being run over [

6,

7]. Dog attacks, illegal capture, and possible environmental contamination are also relevant causes for the risk of

M. tridactyla extinction [

7].

A relevant characteristic that differentiates Xenarthras from other animals is their ability to stand upright due to the anatomical adaptations of their spine, keeping them supported on both pelvic limbs aided by their tails [

2,

8]. This posture is used to obtain food and for defense. Also, the pelvic limbs are essential in the terrestrial locomotion of

M. tridactyla, differing from other fossorial animals. This species has anatomical adaptations in pelvic limbs to gallop when fleeing predators, and despite the slow movements, these adaptations allow running [

9].

Musculoskeletal diseases are vital for diagnosing rescued animals [

10] and those in captivity [

11] because the trauma from being run over [

6] is a relevant cause of mortality for these animals. The high mortality rate of animals sent to rehabilitation centers and the low number of animals that can be reintroduced to their original habitats [

10] show the significance of protecting these animals to avoid the need for treatment and, consequently, their extinction.

This study aimed to provide relevant data concerning the hip joint of M. tridactyla, with considerations about the anatomical structures of the joint and the structures that make up the syntopy. Hence, pelvis radiographs, hip ultrasounds, and anatomical dissections were performed, describing the surgical access to the hip joints. Therefore, the information provided in this study might have clinical and surgical applications to help professionals working directly with the rehabilitation of these animals often rescued in precarious conditions so they can be reintroduced into their habitat or, when this option is not viable, have a better quality of life in captivity.

Materials and Methods

This study received approval from the Animal Use Ethics Committee of the Federal University of Goiás (CEUA/UFG) under protocol number 018/2014, and it was registered in SISBio (Biodiversity Authorization and Information System) with authorizations 92/2009 and 80/2011.

Specimens and Functional Categories

The M. tridactyla specimens were donated by the Wild Animal Screening Center (CETAS) of Goiás, which belongs to the Brazilian Institute for the Environment and Renewable Natural Resources (IBAMA). All animals died for reasons unrelated to this study. Storage and dissection procedures occurred at the Laboratory of Animal Anatomy and Comparative Anatomy (LAANAC), which belongs to the Institute of Biological Sciences (ICB) block VI, and the imaging exams were conducted at the Diagnostic Imaging Sector of the School of Veterinary and Zootechnics (EVZ), all laboratories of the Goiás Federal University (UFG).

Experimental Design

The study performed radiographic and anatomical analyses of the hip joints on ten anatomical specimens, including four samples fixed in 10% formaldehyde, two pelvis, two hemipelvis, and six pelvis from thawed carcasses, totaling 18 assessments. All specimens underwent radiographic examinations and anatomical dissection. The ultrasound examination included three joints without adjacent lesions. The dissection of thawed carcasses promoted a potential surgical approach for the femoral head and neck in M. tridactyla.

Imaging Exams

The fixed samples and thawed carcasses were radiographed using conventional fixed radio diagnostic equipment (Philips®, model KL74/20.40 - São Paulo, SP, Brazil) with an 18x24-cm chassis, and the images were digitized with an FCR Capsule (Fujifilm®, model CR IR 357 - São Paulo, SP, Brazil). Depending on the thickness of the area for radiography, the used kilovoltage varied between 70 and 75 kV and 10 to 12 mAs. The rectum was cleaned in two carcasses for improved visualization of the pelvis and hip joints. The frog-legged ventrodorsal and lateral projections were tested to study the hip joint.

The B-mode ultrasound evaluation used a Mylab 30 Vet device (Esaote®, Genoa, Italy) with a 10 to 18 mHz multifrequency linear transducer. The animal was positioned in lateral decubitus, a wide trichotomy of the region for analysis was performed, and the transducer was placed in the longitudinal axis craniolaterally to the hip after identifying the greater trochanter of the femur.

Macroscopic Dissection Study

For studying the macroscopic dissection of the hip joint, 12 joints were dissected from thawed carcasses, and the six joints from the fixed samples were used for the comparative analysis.

The dissections comprised flapping the skin and identifying superficial and deep muscles; vessels and nerves of the gluteal, lateral, and medial regions of the thigh; and their relationship with the joint capsule. Surgical access was then tested on the contralateral limb according to the previously assessed anatomy. After the access, all musculature was removed to study the joint, consisting of biometry of transverse and longitudinal axes of the acetabula and femoral heads of eight joints and a description of the gross morphology of 12 joints of the thawed carcasses.

Results

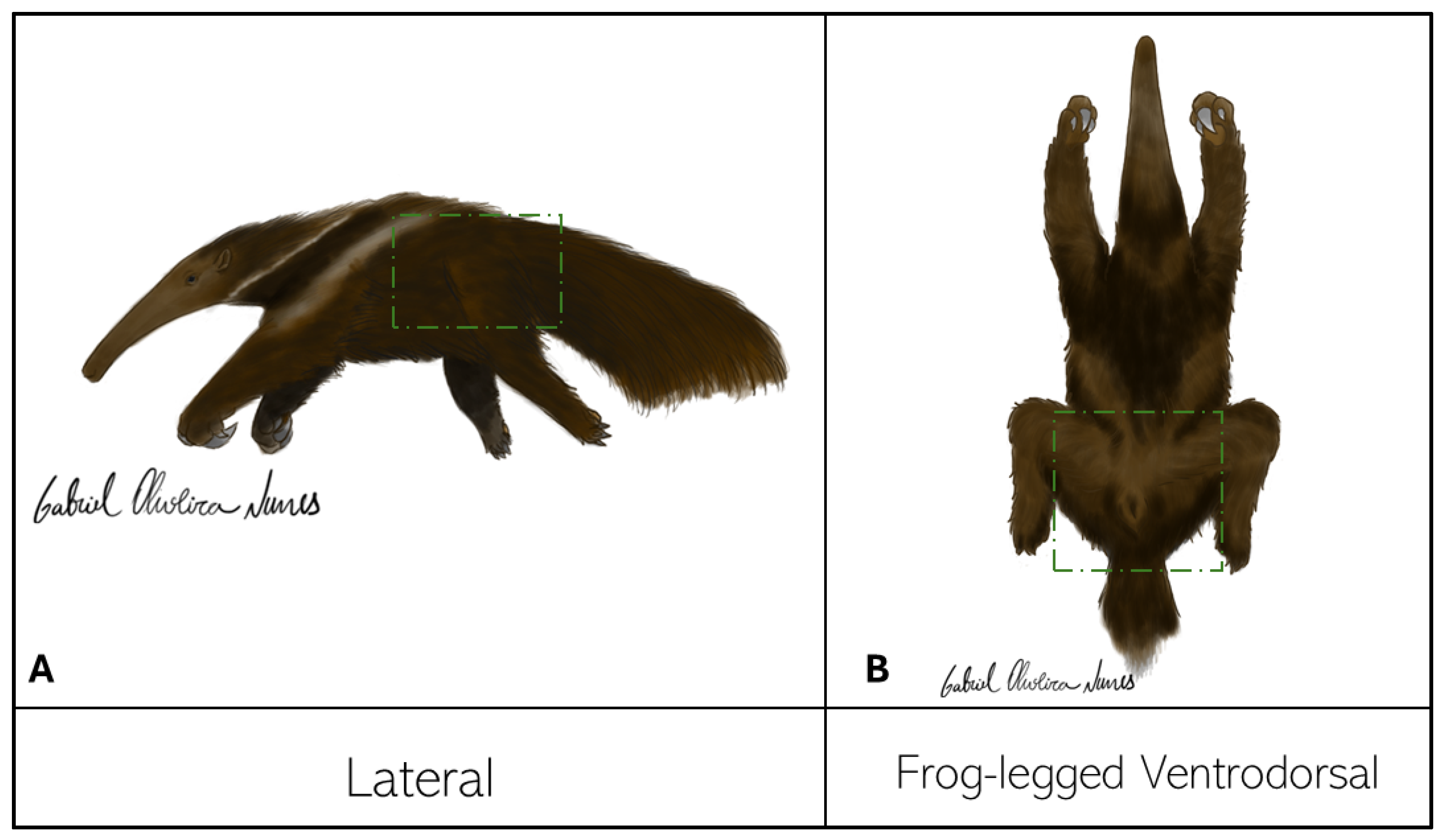

The lateral and frog-legged ventrodorsal projections (

Figure 1) were easy to position and allowed an adequate assessment of the joint space and other adjacent bone structures.

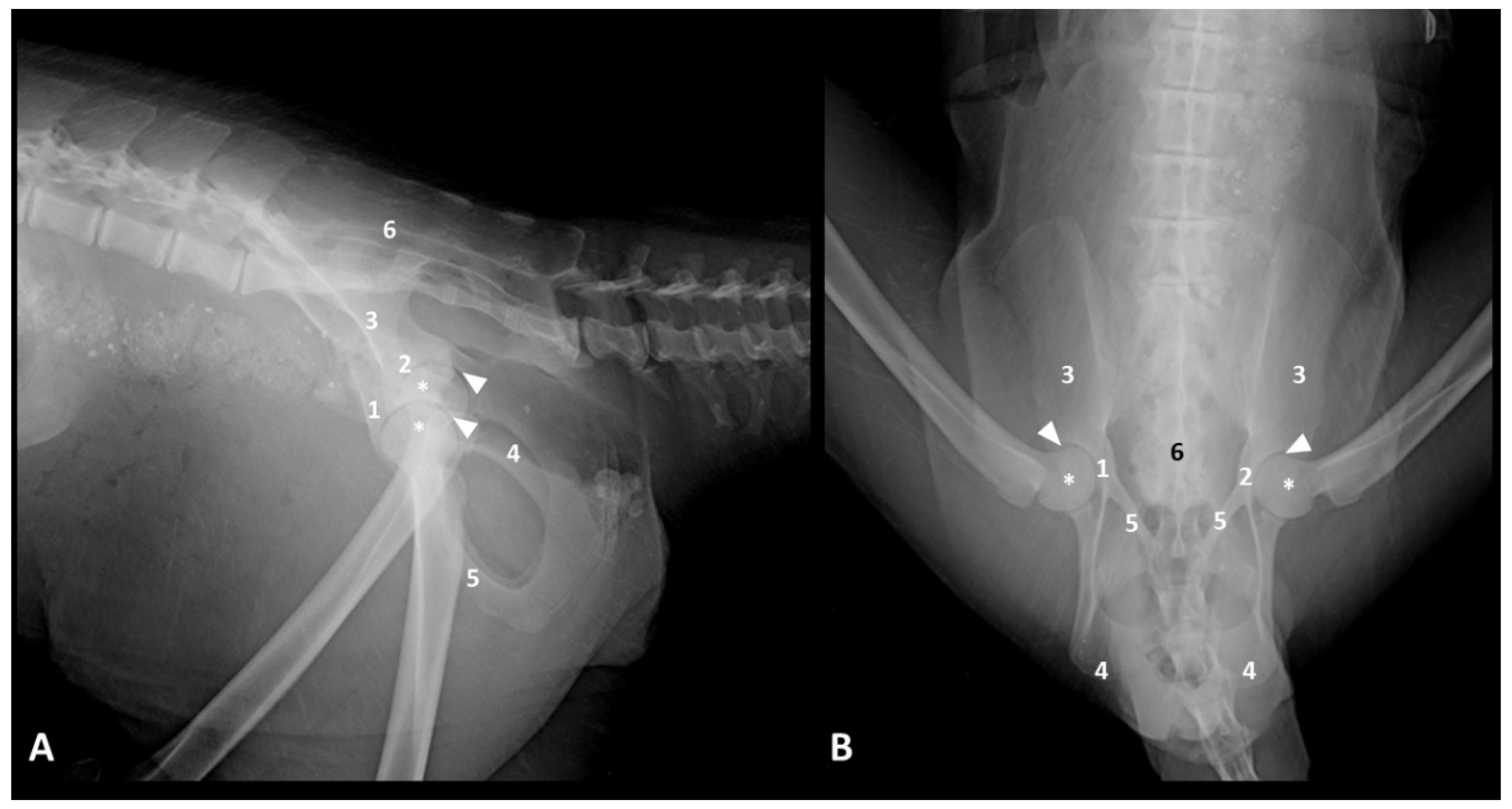

The ventrodorsal frog-legged projection allowed an adequate assessment of the contours of the femoral heads, acetabula, the radiolucent interline between these two elements, and a complete visualization of the bones that make up the pelvis (ilium, ischium, pubis, and sacrum). This study also found that 50% of the six evaluated carcasses had some pelvic injury, either fractures in any bone making up the pelvic girdle or hip joint dislocations. As for the lateral projection, one of the limbs was pulled cranially to remove the overlapping acetabula. The evaluations of the right and left lateral radiographs did not differ.

Figure 2 shows the radiographs and their respective assessments.

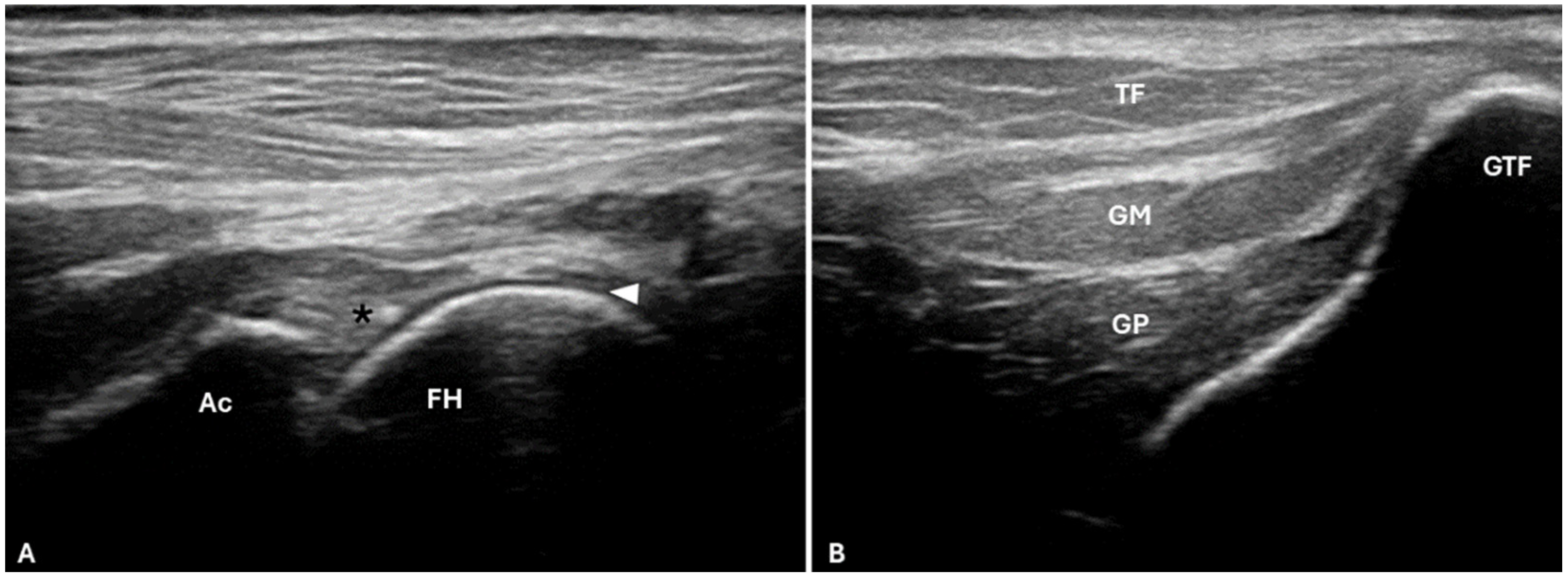

The ultrasound examination (

Figure 3) allowed a partial assessment of the contours of the acetabulum and femoral head and the analysis of the articular soft tissues in this region. The articular cartilage was a hypoechogenic line above the femoral head, with the subchondral bone delimited by a hyperechogenic line. Above the articular cartilage, there was a joint capsule outline as a hyperechogenic structure continuous to the cartilage. The greater trochanter of the femur appeared, with the insertions of the Mm. gluteus medius and profundus and the M. tensor fasciae latae superficially.

The macroscopic dissection evaluated the articular and periarticular elements of the hip joint. The inspection of anatomical structures by measuring the longitudinal and transverse axes of the acetabulum and femoral head revealed a circular shape to both structures, characterized as a spheroid joint with an average measurement of the acetabulum of 27,9 mm by 27,4 mm and femoral head of 26,4 mm by 25 mm.

The acetabulum had an acetabular lip along the entire edge, ending in the acetabular fossa region with the transverse ligament of the acetabulum. The joint capsule was attached to the acetabular contour and in the transition region between the femoral head and neck. After opening the capsule, an intra-articular ligament inserted into the acetabular fossa was visible, characterized as the femoral head ligament (

Figure 4). The hip joint was medially related to the femoral artery, vein, and nerve. The sciatic nerve is located dorsocaudally to the acetabulum, so craniolateral access is recommended for inserting needles for arthrocentesis.

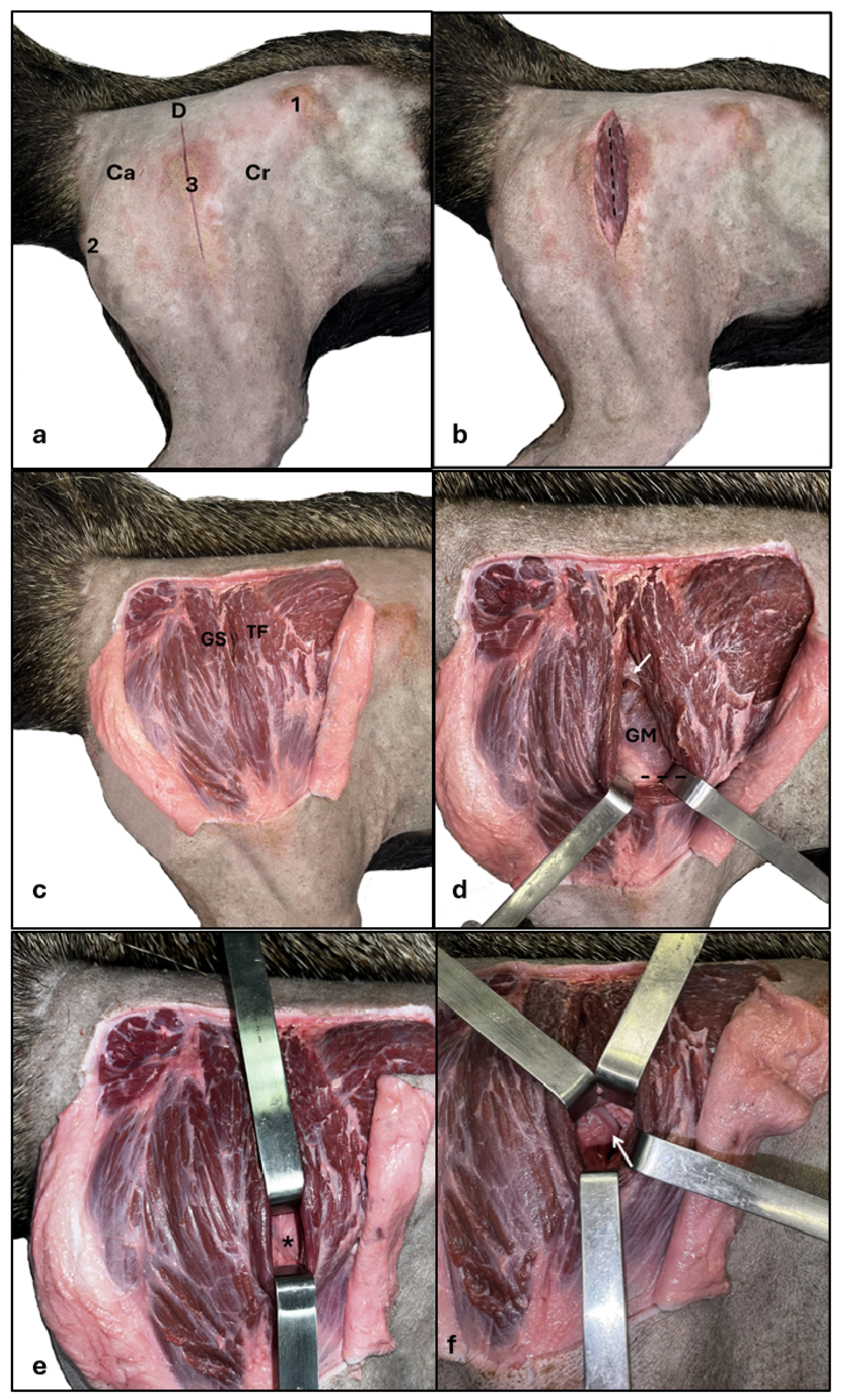

According to the region’s anatomy, the surgical strategy proposed for the hip joint was a lateral approach with the animal in the left lateral decubitus position (

Figure 5). The ilium wing, the ischial tubercle, and the greater trochanter of the femur represented anatomical landmarks (

Figure 5a), and the incision was made dorsolaterally to the greater trochanter, extending to the proximal third of the femoral shaft (

Figure 5b). The skin was then folded back, exhibiting the intermuscular septum between the M. tensor fasciae latae cranially and the M. gluteus superficialis caudally (

Figure 5c). The intermuscular septum was incised, and the M. gluteus medius was located deeply, allowing cranial gluteal nerve visualization in the middle portion of the muscle belly (

Figure 5d). The M. tensor fasciae latae was pulled away cranially until showing the ventral portion of the Mm. gluteus medius and profundus, which were then elevated dorsally. After this maneuver, the joint capsule was located (

Figure 5e) between the Mm. gluteus medius and profundus dorsally, the insertion of M. rectus femoris cranially and M. vastus lateralis caudally and then incised, exposing the femoral head and neck region (

Figure 5f). A wide incision in the joint capsule allowed joint space assessment and femoral head movement. Two specimens underwent partial tenotomy of the Mm. gluteus medius and profundus tendon in the greater trochanter of the femur, better exposing and moving the femoral head.

Discussion

So far, this is the first study focusing on the hip joint of M. tridactyla. The findings were compared to domestic species due to the lack of hip joint literature in other specimens of the Myrmecophagidae family.

The frog-legged ventrodorsal projection allowed an adequate assessment of the pelvis and hip joints, corroborating previous descriptions of more accurate identifications of femoral head fractures in cats [

12]. Also, radiographs in the frog-legged ventrodorsal position allow patients to be relaxed and unstressed in the abducted position, potentially reducing pain from manipulation during the radiographic examination [

13]. Other considerations are the likelihood of rescuing

M. tridactyla specimens after they get hit by a car [

10] and the possibility of these animals having pelvic fractures, which is why this position is comfortable for radiographic examinations in pelvic fracture cases.

Among the corpses collected at the environmental agency, three had pelvic bone fractures (pubis, ilium, ischium, and femur) or hip dislocations, probably secondary to collisions with vehicles, a relevant cause of the decline in this population [

6,

7], even though many animals survive despite severe trauma [

14]. That requires learning ways to improve orthopedic management for this species, considering anatomical variations and behavioral characteristics [

14,

15]; hence, the relevance of the present study.

Ultrasound in

M. tridactyla made it possible to assess the contours of the joint capsule, articular cartilage and adjacent musculature, as described for domestic species [

16,

17,

18] and can be used as a complement to radiography, especially in suspected cases of arthritis and tendon or muscle injuries [

17]. It can also help as a complementary diagnostic method in osteoarthritis [

16,

18] in assessment of joint effusion, joint capsule thickening, bony proliferation, such as periarticular enthesophytes and osteophytes, as well as assisting in treatment through ultrasound-guided arthrocentesis [

19]. The application of drugs, such as hyaluronic acid, is as an adjuvant treatment for osteoarthritis in the hip joint. This technique is possible on

M. tridactyla by inserting the needle craniolaterally into the joint, as in dogs [

20,

21,

22,

23] in an ultrasound-guided procedure or during a surgical approach.

The articular elements of the hip joint of

M. tridactyla are similar to those described in domestic species [

24,

25]. It is a spheroid-shaped ball-and-socket synovial joint with a deep acetabulum, exhibiting the fibrocartilage ring (acetabular lip) that covers the entire edge of the acetabulum up to the acetabular notch. The transverse ligament of the acetabulum was also present in the acetabular notch region [

24,

25]. The extensive joint capsule was inserted next to the external margin of the acetabular lip, covering the contour of the femoral neck distally to where the cartilage covering the femoral head ends [

24,

26]. The femoral head ligament was typical, extending from the femoral head fovea to the acetabular fossa [

24,

25].

The surgical approach of this study to expose the hip joint was extrapolated from the strategy used in dogs [

27], but anatomical particularities of the muscles of

M. tridactyla [

28] require consideration. The approach described in this study was safe in this species without manipulating relevant structures in the surgical field, such as the sciatic nerve and the femoral artery, vein, and nerve, minimizing the risk of injury to these structures, as in dogs [

27]. The cranial gluteal nerve was visualized over the muscle belly of the M. gluteus medius; however, the proposal of accessing the hip joint in this species is more ventral, minimizing the risk of injury to this structure. The approach was also tested on a carcass of

M. tridactyla with bilateral hip dislocation ascertained on the radiographic assessment, being simple and effective for exposing the femoral head and neck.

In dogs, a craniolateral approach is the proposed incision for craniodorsal access to the hip joint. The skin incision begins toward the greater trochanter of the femur, and the incision is curved slightly cranially in the proximal region of the femur, remaining on the cranial edge of the femoral shaft [

27]. This study used lateral access toward the greater trochanter of the femur, extending along the crest of the lateral margin of the femoral shaft [

26] due to the dorsolateral direction of the intermuscular septum between the M. tensor fasciae latae and M. superficial gluteus [

28].

Dogs require an incision in the fascia lata and a caudal retraction of the M. biceps femoris before visualizing the intermuscular septum [

27]. The arrangement of these muscle groups is different [

28] in

M. tridactyla, requiring only a skin incision to locate the intermuscular septum between the M. gluteus superficialis and M. tensor fasciae latae, as their fibers have a different anatomical arrangement than dogs [

25].

For better hip joint access in dogs, a partial tenotomy of the M. gluteus profundus can be performed at its insertion on the greater trochanter of the femur [

27] associated with external rotation of the femur. The M. gluteus profundus in

M. tridactyla is located cranially and distally to the M. gluteus medius at its insertion on the greater trochanter of the femur and covered by the M. gluteus medius [

28]. This species underwent partial tenotomy of the insertion of the M. gluteus medius and profundus with external rotation of the femur, better exposing the femoral head and neck.

Morphological knowledge of the hip joint of

M. tridactyla and surgical access is particularly relevant to provide treatment possibilities for these animals. Excisional arthroplasty of the femoral head and neck is a routine surgical procedure in dogs and cats [

29], forming a pseudoarthrosis in the hip joint by ostectomy of the femoral head and neck. Although there is a case report of this surgery in

M. tridactyla [

30], the described surgical approach involved osteotomy of the greater trochanter of the femur for accessing the hip joint; however, the technique of the present study is more conservative, not performing osteotomies.

In conclusion, the frog-legged ventrodorsal projection is easy to position and allows an adequate assessment of the pelvis and hip joints of M. tridactyla associated with lateral projection. The selected method for animals rescued from the wild due to the high risk of pelvic fractures should be considered. Ultrasound can be performed if there is a suspicion of joint effusion, thickening of the joint capsule or bony proliferations that are not visualized in the radiographic examination. Lateral surgical access to the hip joint of the giant anteater is efficient and safe; however, it requires knowledge of the anatomical particularities of the species, making it unfeasible to literally extrapolate the procedure established in the literature for dogs.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, CCLS, JRC and NCB.; methodology, CCLS, JRC, DBS and NCB.; software, LRF and VRM.; validation, JRC, DBS and NCB.; formal analysis, CCLS, JRC and NCB.; investigation, CCLS, WPRS, LRF, VRM, RALX and MRS.; resources, CCLS, WPRS and NCB.; data curation, CCLS; writing—original draft preparation, CCLS, WPRS, JRC and NCB; writing—review and editing, DBS, LRF, VRM, RALX and MRS.; visualization, CCLS, JRC and NCB.; supervision, JRC, DBS and NCB.; project administration, JRC, DBS and NCB.; funding acquisition, NCB. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.