1. Introduction

The complex mobility of the canine hip joint relies on the coordinated movement of several anatomical structures, including synovial fluid, cartilage, bones, ligaments, tendons, blood vessels, nerves, and muscles [

1,

2]. The hip joint is characterized by the existence of two articular recesses, one cranial and the other caudal to the femoral neck, where synovial fluid preferentially accumulates [

3]. The synovial fluid, accumulating in the cranial and caudal femoral recesses, acts as an important lubricant and shock absorber, reducing friction during movement and protecting the joint [

3,

4,

5]. Maintaining the integrity of these structures is essential for a proper and healthy hip function [

1,

2].

Hip dysplasia (HD) is one of the most common hip disorders affecting medium and large-breed dogs [

6,

7,

8,

9,

10]. It is characterized by degenerative joint disease, resulting in bone remodeling of the acetabulum and the femoral head [

9,

11,

12]. Diagnosis of HD is usually made by using a standard ventrodorsal radiograph taken under sedation or general anesthesia. Moreover, the earliest detectable radiographic sign of HD is hip joint laxity, which is considered the major risk factor for the development and progression of HD [

5,

13]. Hip joint laxity is assessed using the distraction index (DI), a radiographic parameter that quantifies the extent of the femoral head displacement relative to the acetabulum, in a ventrodorsal hip stress radiograph obtained with a hip distractor [

5,

14,

15]. Furthermore, early bone changes characteristic of HD, are preceded by abnormalities in synovial fluid composition and the surrounding joint soft tissues, which result in increased joint laxity [

3,

5,

15]. These early joint changes are especially observed in young animals that are not yet exhibiting clinical signs [

3,

13]. Increment in the hip synovial fluid volume was associated with higher joint laxity in dogs [

16].

Ultrasonography is a widely and cost-effective imaging modality in veterinary medicine, particularly for the diagnosis of musculoskeletal conditions in small animal patients, due to its capacity to identify soft tissue injuries and superficial bone changes [

17,

18]. Unlike radiography, ultrasonography offers the advantage of dynamic imaging, allowing real-time visualization of joint structures, synovial fluid, and soft tissue interactions [

17]. Moreover, it does not expose patients or the operator to ionizing radiation, offering a safer imaging modality [

19,

20]. This imaging technique can be performed in awake dogs with minimal physical restraint, requiring sedation or general anesthesia only in exceptional cases [

17]. Hip ultrasound can be performed using dorsal or ventral approaches, with the ventral approach offering the advantage of not requiring trichotomy due to reduced hair density in the region and resulting in less aesthetic impact [

17,

18,

20,

21].

Previous studies have demonstrated the utility of ultrasonography in evaluating musculoskeletal injuries involving the shoulder, elbow, supraspinatus and biceps tendon, iliopsoas, and for guided hip administrations [

18,

22,

23,

24,

25]. However, literature on hip ultrasonography in dogs remains scarce [

20], additional studies are needed to investigate normal hip sonoanatomy and assess its utility in diagnosing hindlimb pathologies potentially associated with the hip joint.

This study aimed to evaluate the variability of ultrasonographic imaging of hip bone structures and surrounding soft tissues using the ventral approach in young Estrela Mountain dogs, a breed with a high prevalence of HD [

6,

7,

8]. Another objective of this study was to find a relationship between the ultrasonographic and DI measurements. This research will be important to determine whether ultrasonography can reliably detect early abnormalities, such as synovial thickening or increased synovial fluid volume, which may be associated with hip laxity, HD, or related disorders. We hypothesized that hip ultrasonography would effectively identify some early soft tissue changes. In contrast, late-stage osteoarthritic changes, namely changes in cortical echogenicity of the femoral neck and periosteum, femoral head subchondral bone, and articular cartilage, would not yet be detectable. For this purpose, special attention was given to these hip joint structures during the acquisition and analysis of ultrasound images in young animals.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animals

Dogs presenting for screening HD at the Veterinary Hospital of the University of Trás-os-Montes and Alto Douro (UTAD) in 2024 were prospectively enrolled in this diagnostic accuracy study with informed owner consent. Inclusion criteria included animals aged four to twelve months from the Estrela Mountain dog breed. Exclusion parameters required no prior trauma or surgery to the hip joint or pelvic limb and poor ultrasound quality of the images recorded that enabled a proper assessment of the hip joint. A total of 22 dogs (44 hips) were included in this study. Ultrasound studies were performed and analyzed by IT and radiographic views were performed and analyzed by MG.

2.2. Radiographic Hip Stress View and Hip Laxity Measurement

The radiographic image acquisition was performed with the dogs under deep sedation, using butorphanol (Butomidor®, Richter Pharma AG, Austria, at 0.2 mg/Kg) and dexmedetomidine (Sedadex®, Le Vet Beheer B.V., Netherlands, at 4 μg/Kg) intramuscularly, and propofol (Propofol Lipuro®, B.Braun, Portugal at 4 mg/Kg) intravenously. The sedation was reversed with atipamezole hydrochloride (Antisedan®, Orion Corporation, Finland, IM).

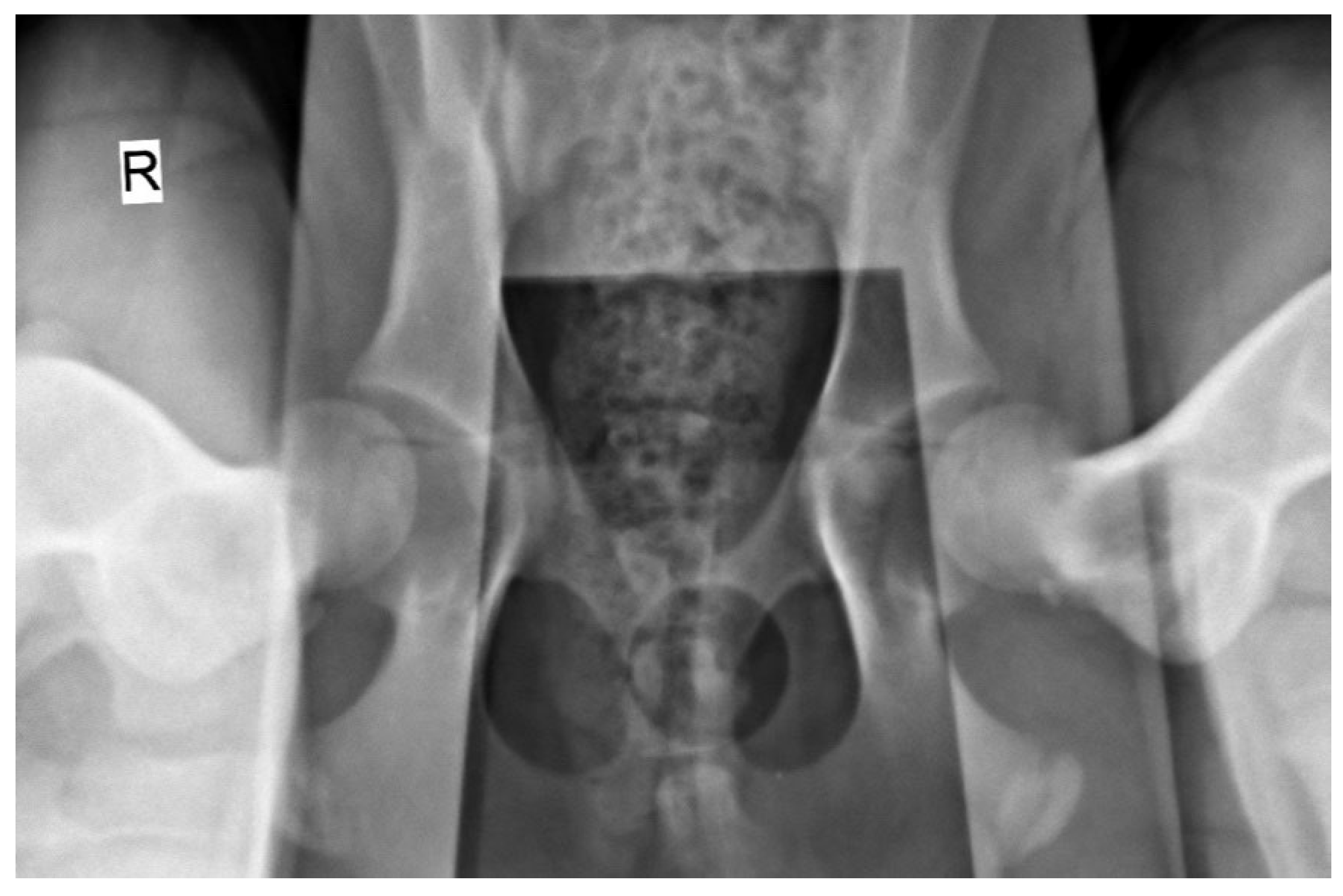

The radiographic stress views were obtained with dogs placed in the supine position on the X-ray table (Optimus 80, Philips, Netherlands), with both femurs in a neutral position and the distractor device (DisUTAD, University of Trás-os-Montes and Alto Douro, Portugal) placed symmetrically between them. Then, the examiner raised and adducted the femurs against the distractor and the stress hip projection was obtained (

Figure 1).

The hip laxity measurements were performed in a semiautomatic software (Horos, version 4.0.0 RC5). The hip laxity was measured by calculating the DI. First, the femoral head and acetabulum were both delimitated by a circumference, and the distance between both circumference’s centres was calculated and then divided by the radius of the femoral head [

5].

2.3. Ultrasonographic Ventral Hip Joint Approach

All ultrasound examinations were performed using a portable ultrasound machine (Logiq e, General Electric Medical Systems, Buc, France) with a high-frequency linear probe (L10-22-RS, General Electric Medical Systems, Buc, France), configured with a musculoskeletal preset. Dogs were positioned in the supine position with the hindlimb flexed 90º and abducted using a ventral approach to the hip joint. Hair clipping was not performed, and acoustic gel was applied to the skin to ensure adequate acoustic coupling of the transducer. To minimize variability in the image acquisition, a standardized protocol for probe positioning and image acquisition was established as follows:

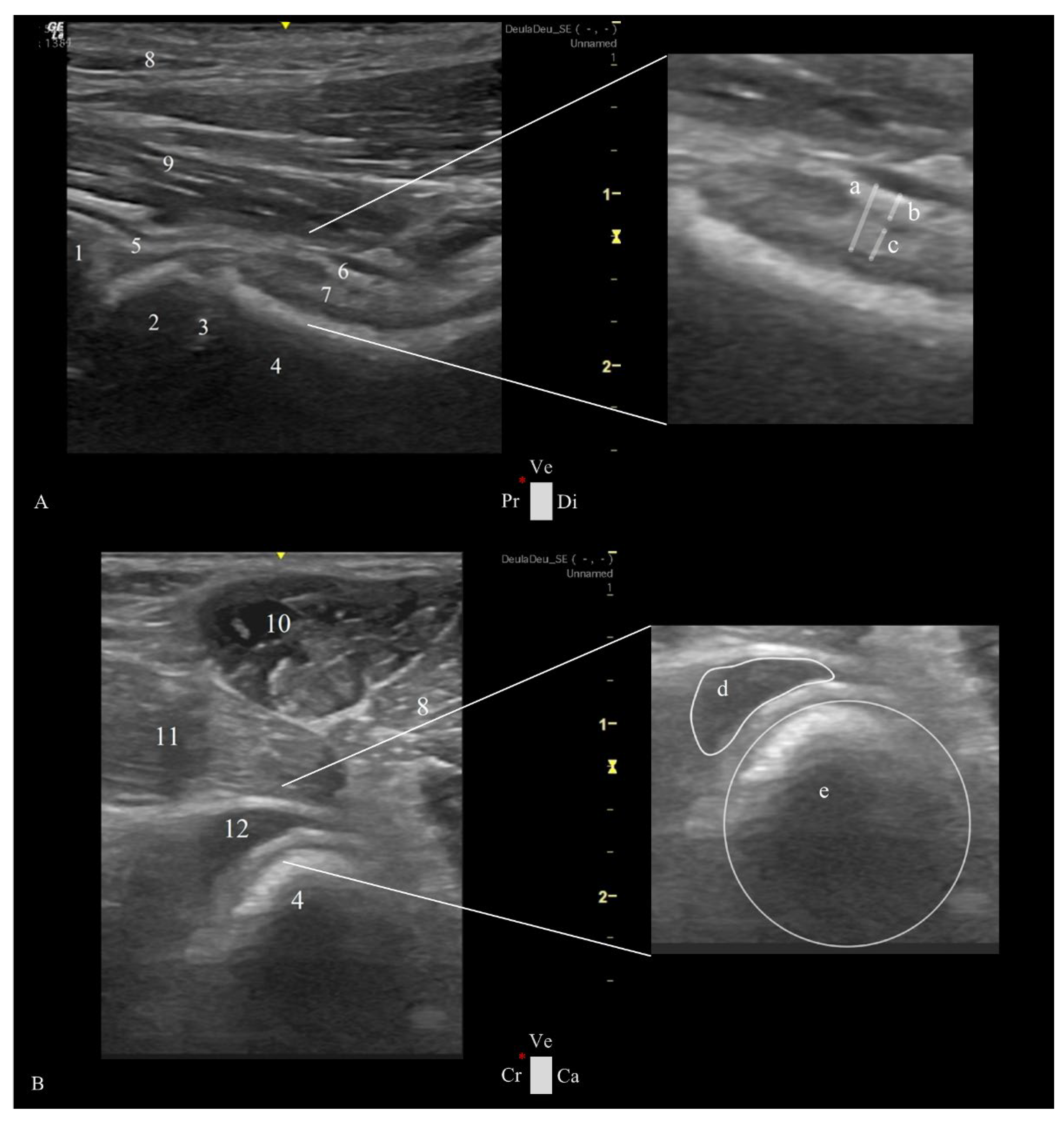

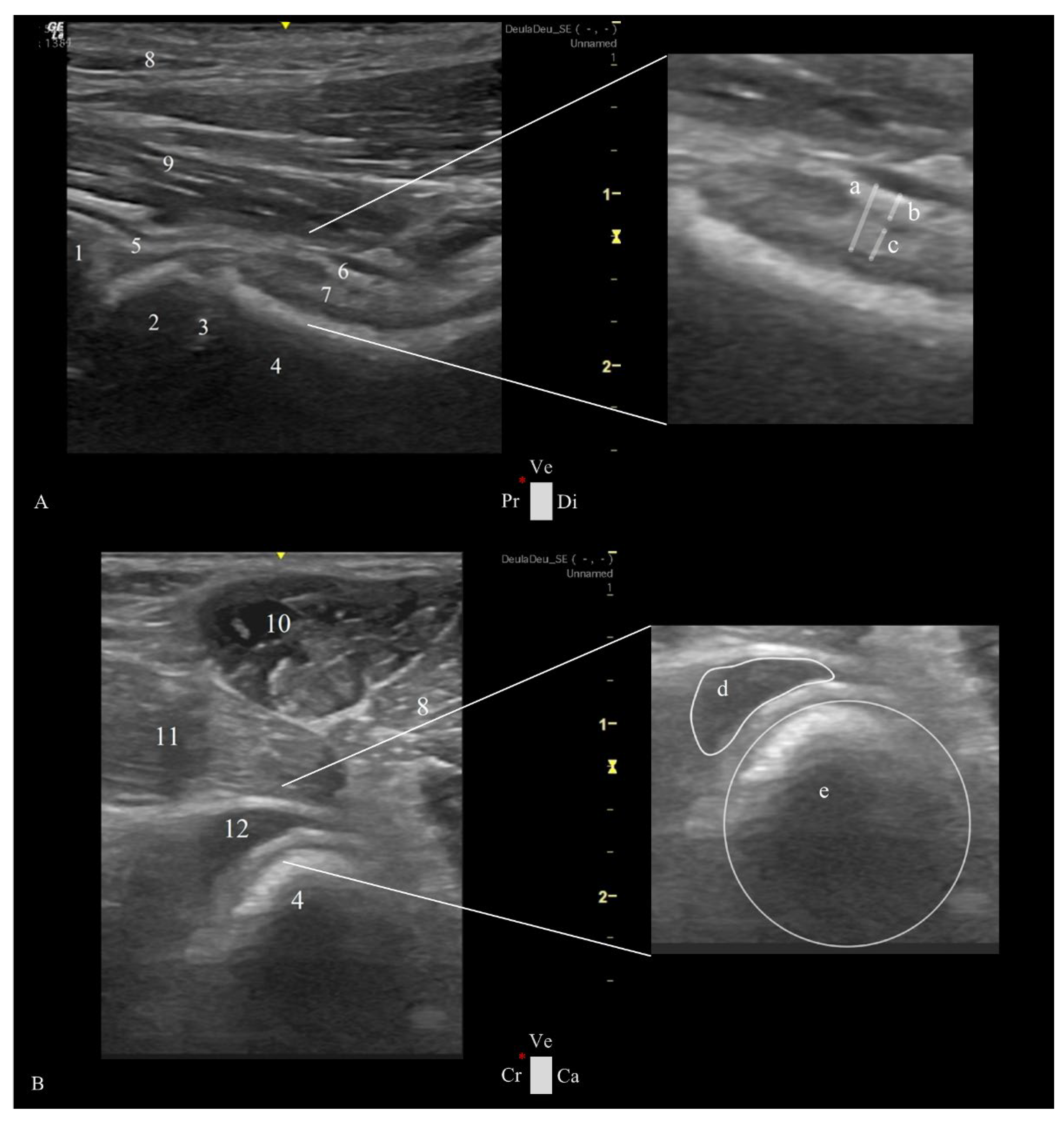

The transducer was placed over the femoral neck and head, directed distoproximally, caudal to the pectineus muscle, with the indicator marker oriented toward the proximal edge of the femur and represented by the left side of the screen. The longitudinal femoral head-neck plane showed three longitudinal muscle layers of adductor magnus et brevis, adductor longus, and iliopsoas, a transverse view of the deep branch of medial circumflex femoral artery and vein, the hip joint capsule, articular space, and synovial lining, the acetabulum and the femoral head (

Figure 2A).

The probe was placed over the pectineus muscle and transversed to the femoral diaphysis, with the indication marker oriented cranially, and then moved distoproximally. Upon reaching the hip joint, the transducer was tilted cranially until allowing the visualization of the acetabulum, femoral head, and neck. Sliding the transducer from the cranial to the caudal ventral acetabular rim provided a comprehensive view of the femoral head-neck and a transverse plane of the cranial femoral neck recess (CFNR). The pectineus, adductors, and iliopsoas were some of the muscles observed in this plane (

Figure 2B).

2.4. Ultrasonographic Hip Joint Measurements

The longitudinal femoral head-neck plane included three measurements at the level of the femoral neck: capsular-synovial fold thickness (CFT) a perpendicular distance between the external limit of the joint capsule and inner synovial membrane layer; the outer and inner synovial membrane thickness, a perpendicular distance between their delimitation (

Figure 2A). In the transverse femoral head-neck plane were performed two measurements: the femoral neck diameter, by drawing a circumference that encompasses the circular cortical bone echogenicity; and the CFNR area, by drawing a free line over the external limit of the anechoic signal of the synovial fluid (

Figure 2B). To reduce the influence of the dog’s size variability, a CFNR index was created, and it is calculated by dividing the CFNR area by the femoral neck diameter. All images were analyzed using a free DICOM Medical Image Viewer Software (Horos, version 4.0.0 RC5).

2.5. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using commercially available software (SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 27.0, IBM, USA). For all variables, parametric tests were based on the Central Limit Theorem, which stipulates that the distribution tends to be normal in samples with n > 30 [

26]. The basic features of the data were presented using minimum, maximum, and mean ± standard deviation (SD). The Pearson coefficients analysis was used to evaluate the relationship between ultrasonographic and radiographic variables. A

P value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

All The study evaluated 22 Estrela Mountain Breed dogs (n = 44 hips), 11 males and 11 females, aged from 4 to 8 months and a mean ± standard deviation (SD) of 4.73 ± 1.26 months, with a body weight of 22.73 ± 6.80 kg. The minimum, maximum, and mean ± SD of the ultrasonographic and radiographic measurements obtained in the study (CFT, outer and inner synovial membrane thickness, femoral neck diameter, CFNR area, CFNR index, and DI) were summarized in

Table 1.

In all animals, the cortical bone of the periarticular structures as well as the subchondral bone of the femoral head revealed linear and regular echogenicity, not evidencing changes compatible with the development of osteophytes or other signs of degenerative joint disease.

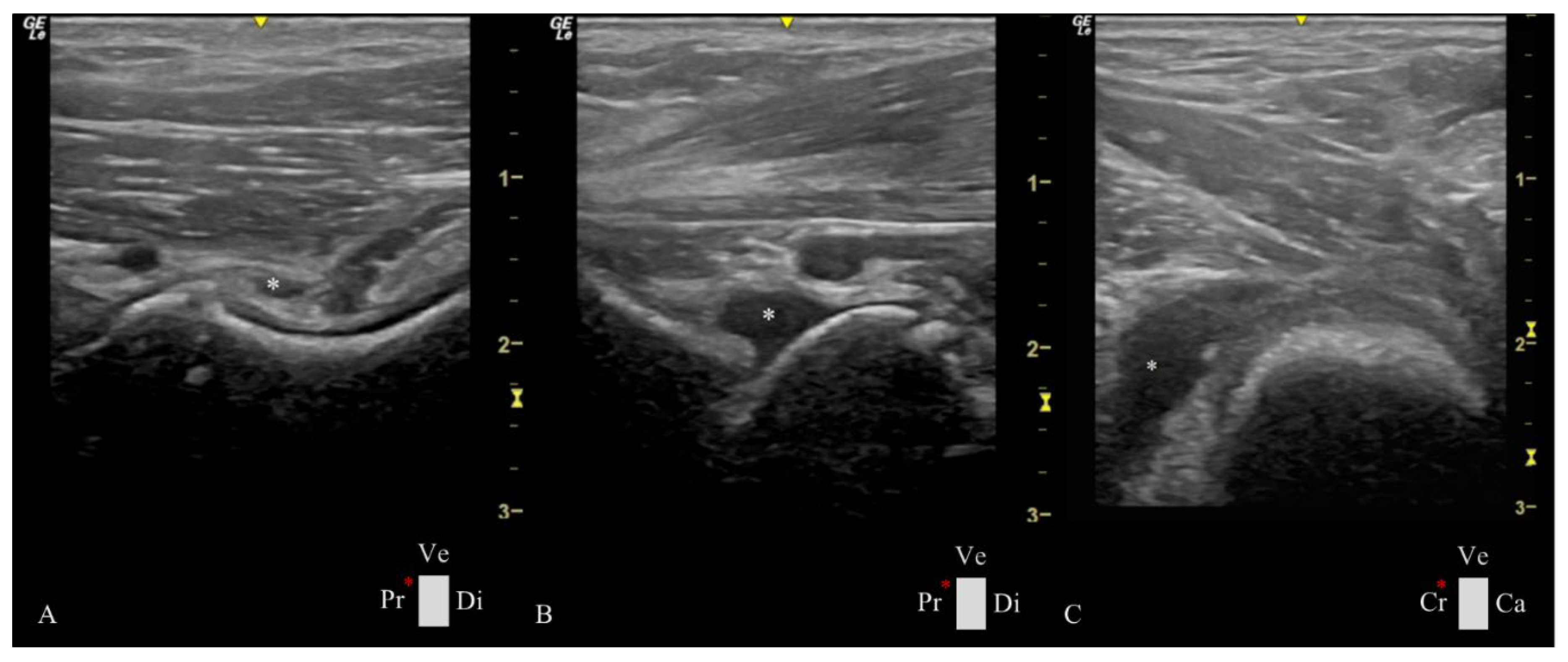

The Pearson correlation (r) was statistically significant and positive among many of these variables (

Table 2). We highlight the strong correlation between the evidence of joint fluid in the ultrasound image CFNR area (r = 0.77;

P < 0.01) and CFNR index (r = 0.85;

P < 0.01) with DI (joint laxity) obtained in stress radiographs. In animals with a higher DI, synovial fluid is evident in different joint spaces (

Figure 3).

4. Discussion

Plain radiographs have been used for decades as the main reference for hip osteoarthritis diagnosis [

12], despite ultrasonography gaining popularity in the last few years in the musculoskeletal field [

19]. Currently, ultrasound is equipped with high-frequency transducers which have facilitated its widespread adoption in veterinary medicine, offering an affordable tool that provides an excellent image quality of superficial musculoskeletal structures [

20,

27]. Our study has demonstrated the utility of ultrasonography for detecting soft tissue changes in young Estrela Mountain breed dogs, associated with hip laxity.

Our initial research hypothesis was confirmed as hip ultrasonography effectively identified soft tissue changes, including CFT and joint synovial fluid area, which showed a statistically significant association with hip laxity evaluated in stress radiographs. Conversely, late-stage osteoarthritic bone changes linked to hip dysplasia were absent in both ultrasound and radiographic evaluations. These findings are in agreement with previous research that underscores soft tissue changes linked to HD. For instance, Ginja et al. (2009) and Smith et al. (1990) identified synovial thickening and increased synovial fluid volume as critical indicators of joint laxity and HD. Similarly, Sudula (2016) and Ginja et al. (2009) emphasized the relevance of recess area measurements, which were found to be correlated with synovial effusion and capsular thickness.

Osteoarthritic changes on the hip, characterized by periarticular bone irregularities observable through the ultrasound, tend to manifest later, following soft tissue changes and joint instability [

2,

3,

5,

27,

28]. In our study, the ventral ultrasonographic hip approach provided a clearer and more standardized imaging of the CFNR compared to the caudal recess. The difference is likely due to anatomical positioning relative to the femoral neck and varying muscular coverage. For this reason, the caudal recess evaluation was not included in this study. Additionally, in the longitudinal view of the cranial recess, identifying an alternative anatomical landmark to the femoral neck for image referencing proved challenging. Therefore, we used the transverse CFNR plane, where the circular echogenicity of the femoral neck cortical bone consistently appeared caudally, serving as a reliable reference point. When assessing the outer and inner synovial membrane, we consistently aimed to capture images on the central plane of the femoral neck to exclude recesses. Some statistically significant correlations were observed, such as those between the outer and inner synovial membrane thickness and CFT or between the CFNR area and CFNR index, which may result from a direct relationship/ dependence between these variables and may not hold substantial clinical significance. The significant correlations between age and the different ultrasonographic measurements, namely CFT, outer and inner synovial membrane thickness, synovial fluid area, and femoral neck diameter were anticipated and may reflect the different growth stages of the animals. Notably, the age-related correlations decreased when indices like the CFNR index and DI were applied, which is consistent with similar studies [

3,

5]. Thus, normalizing the CFNR area by dividing it with the femoral neck diameter for determination of the CRFN index, mitigated the influence of the dogs’ size, as evidenced by a stronger correlation between CRFN index and hip laxity (r = 0.85). These findings emphasize the efficacy of ultrasonography in the early detection of soft tissue changes associated with HD, offering a non-invasive and reliable diagnostic tool that complements traditional radiographic imaging techniques.

The ventral ultrasound approach to the hip joint described in this study holds significant clinical potential for early detection of HD. One major challenge in this anatomical region is that HD often goes unnoticed in its early developmental stages. Consequently, definitive radiographic diagnosis tends to occur later, primarily due to clinical or reproductive purposes (e.g., selecting breeding), emphasizing the need for an early, straightforward, cost-effective imaging method that seamlessly integrates preventive care into the veterinary routine practice. The methodology presented in this research addresses these needs by avoiding deep sedation or general anesthesia, reducing its costs; avoiding the need for trichotomy by adopting the ventral approach to the hip joint, being less time-consuming; and, also, eliminating the exposure to ionizing radiation, diminishing the harmful effects to the public health.

Significant variability was observed in the CFNR index, ranging from 0.88 to 6.43 mm². This variability may reflect individual differences in synovial fluid dynamic or joint structures. Understanding these variations is critical for refining ultrasonographic diagnostic criteria for HD and related disorders. These findings reinforce the predictive value of ultrasonography in assessing early-HD-related changes. Additionally, our observations regarding femoral neck diameter variability mirror the findings of Weigel & Wasserman (1992), who associated such changes with altered biomechanical stress in the hip joint. The study by Greshake & Ackerman (1993) further supports the notion that subtle differences in the femoral neck reflect underlying joint instability. These comparisons highlight the clinical utility of ultrasonographic parameters as early indicators of HD, providing a solid foundation for incorporating such imaging tools into veterinary practice. Nonetheless, our study includes limitations related to experienced operator dependency and challenges in standardizing measurements. Future studies should correlate ultrasonography findings with clinical outcomes, tracking the progression over time of these findings and correlating them with radiographic parameters to further validate their utility and diagnosis capacity.

5. Conclusion

This study highlights the utility of ultrasonography as a non-invasive, cost-effective tool for early detection of HD-related changes in young Estrela Mountain Dogs. By identifying early soft tissue markers associated with joint laxity, the ventral approach to the hip joint could enhance early detection and help define intervention strategies that will improve canine health and benefit breeding programs or hip dysplasia screening. Further studies with larger sample sizes, other breeds, and longitudinal designs are essential to validate the clinical application of ultrasonography and refine predictive methodologies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.T., and M.G..; methodology, M.G.; validation, M.G., S.A., and B.C.; investigation, I.T., and M.G.; writing—original draft preparation, I.T.; writing—review and editing, M.G., S.A.; and B.C.; project administration, M.G.; funding acquisition, M.G., and B.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the projects UIDB/00772/2020 (Doi:10.54499/UIDB/00772/2020) funded by the Portuguese Foundation for Science and Technology (FCT).

Institutional Review Board Statement

All the conducted procedures followed the European and National legislation on the protection of animals used for scientific purposes (European Directive 2010/63/EU and National Decree-Law 113/2013) and were approved by the Ethics Committee (Doc84-CE-UTAD-2023) and the Responsible Body for Animal Welfare at UTAD (ORBEA nº 3180-e-HV-2024).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all dog owners involved in the study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| HD |

Hip Dysplasia |

| CFNR |

Cranial Femoral Neck Recess |

| CFT |

Capsular-Synovial Fold Thickness |

| DI |

Distraction Index |

| SD |

Standard Deviation |

| r |

Pearson Correlation |

| |

|

References

- Weigel, J.P.; Wasserman, J.F. Biomechanics of the Normal and Abnormal Hip Joint. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract 1992, 22, 513–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomé, I.; Alves-Pimenta, S.; Sargo, R.; Pereira, J.; Colaço, B.; Brancal, H.; Costa, L.; Ginja, M. Mechanical Osteoarthritis of the Hip in a One Medicine Concept: A Narrative Review. BMC Vet Res 2023, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ginja, M.M.D.; Ferreira, A.J.; Jesus, S.S.; Melo-Pinto, P.; Bulas-Cruz, J.; Orden, M.A.; San-Roman, F.; Llorens-Pena, M.P.; Gonzalo-Orden, J.M. Comparison of Clinical, Radiographic, Computed Tomographic and Magnetic Resonance Imaging Methods for Early Prediction of Canine Hip Laxity and Dysplasia. Vet Radiol Ultrasound 2009, 50, 135–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, F.; Tang, Y.; Song, B.; Yu, M.; Li, Q.; Zhang, C.; Hou, J.; Yang, R. Nomenclature Clarification: Synovial Fibroblasts and Synovial Mesenchymal Stem Cells. Stem Cell Res Ther 2019, 10, 260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, G.K.; Biery, D.N.; Gregor, T.P. New Concepts of Coxofemoral Joint Stability and the Development of a Clinical Stress-Radiographic Method for Quantitating Hip Joint Laxity in the Dog. J Am Vet Med Assoc 1990, 196, 59–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Willemsen, K.; Möring, M.M.; Harlianto, N.I.; Tryfonidou, M.A.; van der Wal, B.C.H.; Weinans, H.; Meij, B.P.; Sakkers, R.J.B. Comparing Hip Dysplasia in Dogs and Humans: A Review. Front Vet Sci 2021, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roberts, T.; McGreevy, P.D. Selection for Breed-Specific Long-Bodied Phenotypes Is Associated with Increased Expression of Canine Hip Dysplasia. Vet J 2010, 183, 266–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohlerth, S.; Geiser, B.; Flückiger, M.; Geissbühler, U. Prevalence of Canine Hip Dysplasia in Switzerland Between 1995 and 2016—A Retrospective Study in 5 Common Large Breeds. Front Vet Sci 2019, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henrigson, B.; Norberg, I.; Olssons, S.-E. On the Etiology and Pathogenesis of Hip Dysplasia: A Comparative Review. J Small Anim Pract 1966, 7, 673–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez, M.; Schachner, E. Diagnosis, Prevention, and Management of Canine Hip Dysplasia: A Review. Vet Med-Res Rep 2015, 181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riser, W. The Dysplastic Hip Joint: Radiologic and Histologic Development. Vet Pathol 1975, 12, 279–305. [Google Scholar]

- Ginja, M.M.D.; Silvestre, A.M.; Gonzalo-Orden, J.M.; Ferreira, A.J.A. Diagnosis, Genetic Control and Preventive Management of Canine Hip Dysplasia: A Review. Vet J 2010, 184, 269–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flückiger, M. Scoring Radiographs for Canine Hip Dysplasia – The Big Three Organisations in the World. Eur J Companion Anim Pract 2007, 17, 135–140. [Google Scholar]

- Flückiger, M.A.; Friedrich, G.A.; Binder, H. A Radiographic Stress Technique for Evaluation of Coxofemoral Joint Laxity in Dogs. Vet Surg 1999, 28, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lust, G.; Beilman, W.T.; Rendano, V.T. A Relationship between Degree of Laxity and Synovial Fluid Volume in Coxofemoral Joints of Dogs Predisposed for Hip Dysplasia. Am J Vet Res 1980, 41, 55–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farese, J.P.; Lust, G.; Williams, A.J.; Dykes, N.L.; Todhunter, R.J. Comparison of Measurements of Dorsolateral Subluxation of the Femoral Head and Maximal Passive Laxity for Evaluation of the Coxofemoral Joint in Dogs. Am J Vet Res 1999, 60, 1571–1576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, C.R. Ultrasound Imaging of the Musculoskeletal System. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract 2016, 46, 355–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Todd-Donato, A.B.; VanDeventer, G.M.; Porter, I.R.; Krotscheck, U. Ultrasound Is an Accurate Imaging Modality for Diagnosing Hip Luxation in Dogs Presenting with Hind Limb Lameness. J Am Vet Med Assoc 2024, 262, 1379–1387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sudula, S. Imaging the Hip Joint in Osteoarthritis: A Place for Ultrasound? Ultrasound 2016, 24, 111–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergamino, C.; Etienne, A.-L.; Busoni, V. Developing a Technique for Ultrasound-Guided Injection of the Adult Canine Hip. Vet Radiol Ultrasound 2015, 56, 456–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greshake, R.J.; Ackerman, N. Ultrasound Evaluation of the Coxofemoral Joints of the Canine Neonate. Vet Radiol 1993, 34, 99–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sack, D.; Canapp, D.; Canapp, S.; Majeski, S.; Curry, J.; Sutton, A.; Cullen, R. Iliopsoas Strain Demographics, Concurrent Injuries, and Grade Determined by Musculoskeletal Ultrasound in 72 Agility Dogs. Can J Vet Res 2023, 87, 196–201. [Google Scholar]

- Entani, M.G.; Franini, A.; Dragone, L.; Barella, G.; De Rensis, F.; Spattini, G. Efficacy of Serial Ultrasonographic Examinations in Predicting Return to Play in Agility Dogs with Shoulder Lameness. Animals 2021, 12, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kern, T.; Manfredi, J.; Tomlinson, J. Ultrasonographic Appearance of Supraspinatus and Biceps Tendinopathy Improves in Dogs Treated with Low-Intensity Extracorporeal Shock Wave Therapy: A Retrospective Study. Front Vet Sci 2023, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacqmin, M.; Livet, V.; Sonet, J.; Harel, M.; Viguier, E.; Moissonnier, P.H.; Cachon, T. Use of Ultrasonography in Diagnosis of Medial Compartment Disease of the Elbow in Dogs. Vet Comp Orthop Traumatol 2023, 36, 132–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwak, S.G.; Kim, J.H. Central Limit Theorem: The Cornerstone of Modern Statistics. Korean J Anesthesiol 2017, 70, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomé, I.; Alves-Pimenta, S.; Costa, L.; Pereira, J.; Sargo, R.; Brancal, H.; Ginja, G.; Colaço, B. Establishment of an Ultrasound-Guided Protocol for the Assessment of Hip Joint Osteoarthritis in Rabbits – a Sonoanatomic Study. PLoS One 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, J.R.; Gambino, J. Canine Hip Dysplasia. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract 2017, 47, 777–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Distraction radiographic view obtained with the hip distractor DisUTAD of a male dog with 4 months of age and a body weight of 20 kg. The image shows great joint laxity bilaterally, evidenced by the separation between the femoral head and the acetabulum. A distraction index of 0.65 and 0.62 was registered in the right and left joints, respectively. R: right side.

Figure 1.

Distraction radiographic view obtained with the hip distractor DisUTAD of a male dog with 4 months of age and a body weight of 20 kg. The image shows great joint laxity bilaterally, evidenced by the separation between the femoral head and the acetabulum. A distraction index of 0.65 and 0.62 was registered in the right and left joints, respectively. R: right side.

Figure 2.

Ultrasound views were obtained in a ventral approach to the right hip joint in a female dog at 4 months of age and weighing 20 kg. A- Longitudinal plane of the femoral head-neck, showing on the right side a magnified view of the joint capsule with measurements performed in the study: (a) capsular-synovial fold thickness, (b) outer and (c) inner synovial membrane thickness with a 2.30, 0.80 and 1.00 mm, re-spectively. B- Transversal plane of the femoral head-neck showing on the right side magnified view of the transverse plane of the cranial femoral neck recess and femoral neck, with measurements performed in the study: (d) cranial femoral neck recess with 25.00 mm2 and (e), circumference delimitating the femoral neck with a diameter of 16.00 mm. (1) ventral acetabular rim, (2) femoral head, (3) proximal femoral growth plate, (4) femoral neck, (5) joint capsule, (6) outer synovial membrane layer, (7) outer synovial internal synovial lining, (8) adductor magnus et brevis muscle, (9) adductor longus muscle, (10) pectineus muscle, (11) iliopsoas muscle, and (12) transverse view of the cranial femoral neck recess. Ca: caudal, Cr: cranial, Di: distal, Pr: proximal, Ve: ventral, and *: probe orientation and indication marker.

Figure 2.

Ultrasound views were obtained in a ventral approach to the right hip joint in a female dog at 4 months of age and weighing 20 kg. A- Longitudinal plane of the femoral head-neck, showing on the right side a magnified view of the joint capsule with measurements performed in the study: (a) capsular-synovial fold thickness, (b) outer and (c) inner synovial membrane thickness with a 2.30, 0.80 and 1.00 mm, re-spectively. B- Transversal plane of the femoral head-neck showing on the right side magnified view of the transverse plane of the cranial femoral neck recess and femoral neck, with measurements performed in the study: (d) cranial femoral neck recess with 25.00 mm2 and (e), circumference delimitating the femoral neck with a diameter of 16.00 mm. (1) ventral acetabular rim, (2) femoral head, (3) proximal femoral growth plate, (4) femoral neck, (5) joint capsule, (6) outer synovial membrane layer, (7) outer synovial internal synovial lining, (8) adductor magnus et brevis muscle, (9) adductor longus muscle, (10) pectineus muscle, (11) iliopsoas muscle, and (12) transverse view of the cranial femoral neck recess. Ca: caudal, Cr: cranial, Di: distal, Pr: proximal, Ve: ventral, and *: probe orientation and indication marker.

Figure 3.

Ultrasonographic images of Estrela Mountain Dog hips at 4 months of age presenting a considerable amount of synovial fluid (white *) in different compartments of the hip joint. The hip joints have a great joint laxity with a distraction index of 0.60. A- Longitudinal plane of the femoral head-neck plane showing synovial fluid between the outer and inner synovial membrane and an increased CFT of 3.40 mm. B- Longitudinal plane of the femoral head-neck in which fluid accumulation was observed in the ventral aspect of the hip joint. C- Transverse plane of the femoral head-neck displaying a cranial femoral neck recess with an area of 79.00 mm2. Ca: caudal, Cr: cranial, Di: distal, Pr: proximal, Ve: ventral, and red *: probe orientation and indication marker.

Figure 3.

Ultrasonographic images of Estrela Mountain Dog hips at 4 months of age presenting a considerable amount of synovial fluid (white *) in different compartments of the hip joint. The hip joints have a great joint laxity with a distraction index of 0.60. A- Longitudinal plane of the femoral head-neck plane showing synovial fluid between the outer and inner synovial membrane and an increased CFT of 3.40 mm. B- Longitudinal plane of the femoral head-neck in which fluid accumulation was observed in the ventral aspect of the hip joint. C- Transverse plane of the femoral head-neck displaying a cranial femoral neck recess with an area of 79.00 mm2. Ca: caudal, Cr: cranial, Di: distal, Pr: proximal, Ve: ventral, and red *: probe orientation and indication marker.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics of the ultrasonographic and radiographic measurements in 22 (44 hips) Estrela Mountain Breed dogs.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics of the ultrasonographic and radiographic measurements in 22 (44 hips) Estrela Mountain Breed dogs.

| |

|

|

N

(number of hips) |

Minimum |

Maximum |

Mean ± SD |

| Ultrasonographic Measurements |

Longitudinal View |

Capsular-Synovial Fold Thickness |

44 |

1.7 mm |

6.31 mm |

3.21 ± 0.90 mm |

| Outer Synovial Membrane Thickness |

44 |

0.50 mm |

2.50 mm |

1.37 ± 0.42 mm |

| Inner Synovial Membrane Thickness |

44 |

0.70 mm |

2.50 mm |

1.25 ± 0.39 mm |

| Transverse View |

Femoral Neck Diameter |

44 |

13.00 mm |

22.00 mm |

17.13 ± 2.11 mm |

| CFNR Area |

44 |

15.00 mm² |

135.00 mm² |

45.58 ± 25.40 mm² |

| CFNR Index |

44 |

0.88 |

6.43 |

2.67 ± 1.36 |

| Radiographic Measurements |

Distraction Index |

44 |

0.20 |

0.65 |

0.40 ± 0.10 |

Table 2.

Pearson correlations and statistical significance among ultrasonographic and radio-graphic measurements in 22 (44 hips) Estrela Mountain Breed dogs aged from 4 to 8 months.

Table 2.

Pearson correlations and statistical significance among ultrasonographic and radio-graphic measurements in 22 (44 hips) Estrela Mountain Breed dogs aged from 4 to 8 months.

| Variables in the study |

Ultrasonographic Measurements |

Radiographic Measurements |

| Longitudinal femoral head-neck plane |

Transverse femoral head-neck plane |

| |

Capsular-Synovial Fold Thickness |

Outer Synovial Membrane Thickness |

Internal Synovial Lining Thickness |

Femoral Neck Diameter |

CFNR Area |

CFNR Index |

Distraction Index |

| Capsular-Synovial Fold Thickness |

|

|

|

|

|

|

0.58* |

| Outer Synovial Membrane Thickness |

0.90* |

|

|

|

|

|

0.55* |

| Inner Synovial Membrane Thickness |

0.70* |

0.80* |

|

|

|

|

0.30* |

| Femoral Neck Diameter |

0.60* |

0.92* |

0.29 |

|

|

|

- 0.09 |

| CFNR Area |

0.75* |

0.71* |

0.63* |

0.22 |

|

|

0.77* |

| CFNR Index |

0.74* |

0.69* |

0.54* |

- 0.03 |

0.96* |

|

0.85* |

| Age |

0.46* |

0.47*

|

0.69* |

0.59* |

0.39* |

0.24 |

0.14 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).