1. Introduction

Canine hip dysplasia (CHD) is one of the most prevalent orthopedic diseases in dogs, particularly in medium- and large-breed populations [

1,

2,

3]. It is a hereditary disease primarily associated with coxofemoral joint laxity, abnormal development of the femoral head, and progressive osteoarthritis [

4,

5,

6,

7]. This disease results in osteoarthritis, which is often followed by pain, functional limitations and a poorer quality of life [

8]. In veterinary medicine, radiography has been essential in CHD diagnosis for therapeutic and screening purposes [

9,

10]. Animals with radiographic signs of CHD are not recommended for breeding, as this helps to reduce the occurrence of undesirable alleles in the canine population and diminishes the clinical and phenotypic manifestation of the disease [

6,

11,

12].

Conventional radiographic assessment, especially using the ventrodorsal hip extended view, remains the gold standard for CHD diagnosis in adult animals [

6]. The classification of CHD in adult animals by the Fédération Cynologique Internationale (FCI) scheme grades hips in five gradual categories from A (normal) to E (severely dysplastic) and is widely applied in most countries for clinical decision-making, breeding programs, and epidemiological studies [

13,

14].

Conventional radiography primarily detects advanced bony alterations, providing limited insight into CHD early-stage, and periarticular and soft tissue changes [

7,

13,

15,

16]. Ultrasonography (US), on the other hand, provides a safe, ionizing radiation-free imaging modality capable of providing dynamic images in real time and with no need for deep sedation or general anaesthesia [

17,

18,

19]. It also identifies some bone osteoarthritic changes, periarticular soft-tissue and bone surface changes that may not be readily detected on radiographs [

17,

20,

21]. Several studies have demonstrated US potential in identifying joint effusion, capsular thickening, osteophytes, and morphologic irregularities in the femoral head [

20,

21,

22]. Capsular thickening has shown good sensitivity and specificity for distinguishing between normal and dysplastic hips, with increased thickness being strongly associated with increased hip joint laxity and osteoarthritic progression [

20].

Recent methodological advances, including a standardized ventral hip approach to the femoral head-neck region, have enhanced the reproducibility and diagnostic value of US in veterinary orthopedics. This protocol allows a detailed assessment of the femoral head contour and head–neck transition zone, providing valuable information on both early joint remodeling and established dysplastic changes [

20].

This study aimed to associate the US parameters, capsule thickness at the femoral head index (CTFHi), capsular-synovial fold thickness index (CSFTi), femoral head shape score (FHSs), femoral head-neck transition score (FHNTs) and osteophyte score (Os), with the FCI grading system. To the authors’ knowledge, no previous studies have investigated these hip US parameters and, therefore, the premise that these parameters will not differ across FCI grades was established as the null hypothesis.

2. Materials and Methods

3.1. Animals

Twenty-two adult dogs of various breeds were presented for screening of CHD at the Veterinary Hospital of the University of Trás-os-Montes and Alto Douro (UTAD) and were prospectively enrolled in the study with informed owner consent. Dogs with a history of hip joint trauma were excluded. All subjects underwent both radiographic and ultrasonographic examination of the hip joints. Breed, age, sex, and body weight were recorded.

3.2. Imaging Assessment

The image acquisition was performed with the dogs under deep sedation, using butorphanol (Butomidor®, Richter Pharma AG, Austria, at 0.2 mg/Kg), dexmedetomidine (Sedadex®, Le Vet Beheer B.V., Netherlands, at 1 μg/Kg), and propofol (Propofol Lipuro®, B.Braun, Portugal, at 4 mg/Kg) intravenously.

3.2.1. Radiographic Assessment

Standard ventrodorsal hip-extended radiographs were taken (Optimus 80, Philips, Netherlands) and hips were evaluated according to the FCI grading system (grades A to E). For statistical analysis, hips were grouped as follows [

13,

14]:

• Normal Hips Group: A and B FCI scoring. Normal hips (A) are characterized by a congruent femoral head and acetabulum, a sharp and rounded craniolateral acetabular rim, and a Norberg angle of around 105°. In near-normal hips (B), the acetabulum and femoral head may be slightly incongruent, and the Norberg angle is near 105°.

• Dysplastic Hips Group: C, D, and E FCI scoring. Mildly dysplastic hips (C) have an incongruent femoral head and acetabulum, a Norberg angle of around 100°, and may evidence slight osteoarthritic signs on the acetabular edge and flattening of the craniolateral acetabular rim. Moderate dysplastic hips (D) have clear incongruity between the femoral head and the acetabulum, subluxation, a Norberg angle of around 90°, flattening of the craniolateral rim, or the presence of osteoarthritic signs. Severely dysplastic hips (E) have a more marked subluxation or even luxation, a Norberg angle less than 90°, obvious flattening of the cranial acetabular edge, a mushroom-shaped/ flattened femoral head, and may have other signs of osteoarthrosis.

The radiographic views were performed and analyzed by a single experienced examiner (MG).

3.2.2. Ultrasonographic Examination

Ultrasound assessment was performed using a portable US machine (Logiq e, General Electric Medical Systems, Buc, France) equipped with a high-frequency linear probe (L8-18i-RS, General Electric Medical Systems, Buc, France) in a standardized ventral longitudinal approach to the femoral head-neck region, as described by Tomé et al. [

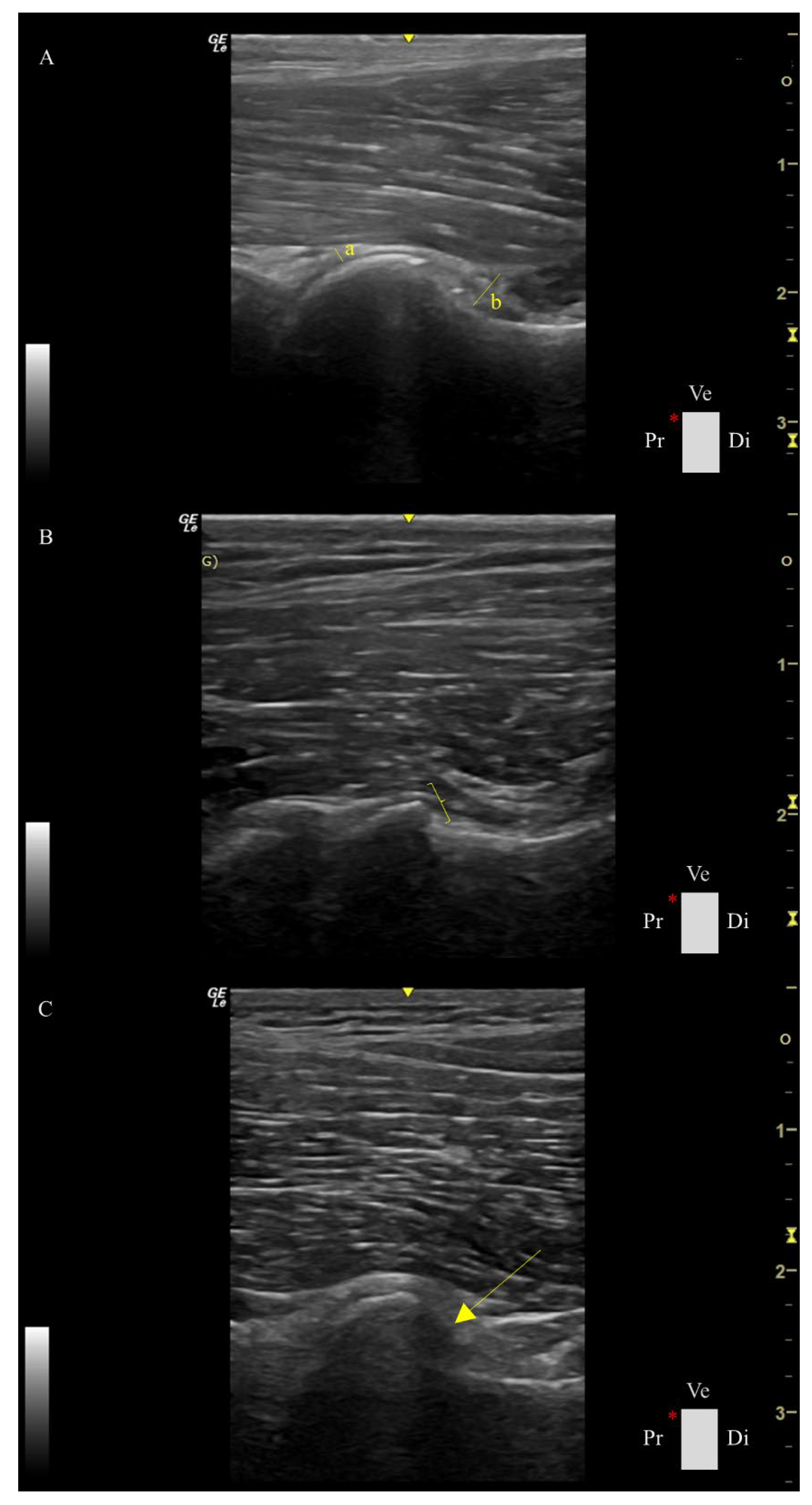

17]. The following parameters were assessed for each hip as follows (

Figure 1):

1. Capsule thickness at the femoral head index (CTFHi): measured in mm/ body weight *100. The capsule was measured as the maximum perpendicular distance between the external and internal limits of the joint capsule.

2. Capsular-synovial fold thickness index (CSFTi): measured in mm/ body weight *100, which comprises the perpendicular distance between the external limit of the outer synovial membrane layer and the internal limit of the inner synovial membrane.

3. Femoral head shape score (FHSs): spherical, flattened, or severely flattened was converted into a numerical scale of 1, 2, or 3, respectively.

4. Femoral head-neck transition score (FHNTs): smooth, irregular, or highly irregular was converted into a numerical scale of 1, 2, or 3, respectively.

5. Osteophyte score (Os): absent or present was converted into a numerical scale of 0 or 1, respectively.

All US parameters were performed by a single experienced operator blinded to FCI grading (IT) and using the Radiant Dicom Viewer (Medixant, Poland).

3.3. Statistical Analysis

Data was analyzed using SPSS (IBM Statistics for Windows, Version 27.0, USA). Basic US features of the data were presented as continuous variables using mean, standard deviation, median, and interquartile range. Data were tested for normality using the Shapiro-Wilk test, and group differences were assessed using the Mann–Whitney U test for non-parametric variables. Also, a correlation analysis using Spearman’s coefficients was employed to evaluate the relationships between measured parameters. A P value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

The mean body weight of dogs was 29.52 ± 14.93 kg (mean ± SD). Six different breeds were considered in this study, namely seven Portuguese Sheepdogs, six Estrela Mountain dogs, three Transmontano Mastiff dogs, three Portuguese Pointer dogs, and three Border Collie dogs. Dogs were aged between 13 to 136 months with a mean age of 41.00 ± 29.51 months.

A total of 44 hips were evaluated radiographically and distributed according to the FCI grading system as follows: Normal hips group with 23 hips (8 hips of FCI score A and 15 hips of FCI score B); Dysplastic hips group with 21 hips (6 hips of FCI Score C, 11 hips of FCI score D and 4 hips of FCI score E). Then, these hips were submitted to a US assessment following the established US-Guided protocol [

17] and in the images recorded different US parameters were collected. The median of the US parameters CTFHi, CSFTi, FHSs, FHNTs and Os was, respectively, 2.02, 7.79, 1.00, 1.00, 0.00 in the normal hips group and 3.11, 9.32, 3.00, 2.00, 1.00 in the dysplastic hips group. Statistically significant differences were observed in the US parameters CTFHi, FHSs, FHNTs, and Os between the normal and dysplastic hips groups (

Table 1).

Using the Spearmen correlation analysis, a very strong relationship was found between the FHNTs and the osteophyte scores, a strong relationship between the CSFTi and FHNTs and Os and a moderate relationship between the CTFHi and the CSFTi

, FHNTs, and Os. The other US parameters relationships were weak or low correlations (

Table 2).

4. Discussion

This study demonstrated that ultrasonographic assessment of the canine hip joint, using a standardized longitudinal femoral head–neck approach, reveals measurable differences in soft tissue and bony structures among hips grouped according to the FCI radiographic scoring in different US parameters evaluated: CTFHi, FHSs, FHNTs, and Os.

Joint capsule thickening, especially over the femoral head, showed a significant trend across research groups, with higher values observed in the dysplastic group. Our findings are in agreement with previous studies, indicating that capsular thickening may reflect chronic synovial inflammation or joint effusion in response to hip laxity and instability [

17,

21,

22]. Our results support the idea that the CTFHi, particularly when values were normalized to body weight, may act as a marker for CHD monitoring. Additionally, dogs in the dysplastic hips group exhibited a higher median value in CSFTi when compared to the normal hips groups. Although this tendency was not statistically significant, it is expected that a wider sample and enhancements in the US parameters acquisition may help further characterize and stratify the US research groups.

Importantly, alterations in FHSs and FHNTs also demonstrated statistically significant differences between groups. In the normal hips group, the femoral head was consistently spherical with a smooth transition to the femoral neck. In contrast, the dysplastic hips group displayed flattened femoral heads and highly irregular head-neck transitions in the US. These changes reflect biomechanical adaptations to chronic subluxation and altered joint loading, important hallmarks of progressive CHD [

13,

23,

24,

25]. Our results support these findings; the dysplastic hips group showed significantly more severe morphological alterations than the normal hips group. The transition from smooth to irregular contours at the femoral head–neck junction has been previously highlighted as an early sign of joint remodelling and a predictor of osteoarthritic changes [

17].

The Os was revealed to be the US assessment feature with the strongest association within the different FCI classification groups. The dysplastic hips group demonstrated a significantly higher frequency of osteophyte formation than the normal hips group, which had a frequency of zero, underlying that the FCI grading scheme stratification in grades A and B has a rare probability of developing osteophytes compared to C, D, and E, where its development is more common. Osteophyte formation is a hallmark of late-stage joint degeneration and a major determinant in radiographic CHD grading [

26,

27]. Our results confirm that US can sensitively detect osteophytes even in the early stages, reinforcing its utility for longitudinal monitoring and early diagnosis of CHD.

The Spearman correlation analysis provided additional insights into the relationships between ultrasonographic parameters. Strong positive correlations were found between the CSFTi and the FHNTs, and the Os, showing that soft tissue and bone changes progress as hip dysplasia worsens. This statement agrees with previous studies where capsular thickening and periarticular bone changes were described as secondary responses to joint laxity and instability [

17,

21]. The FHNTs and Os were very strongly associated, revealing consistency with other reports highlighting that irregular bone contours predispose to osteophyte formation as part of the degenerative cascade [

17]. CTFHi also correlated moderately with CSFTi, FHNTs, and Os, suggesting that it can serve as an early indicator of joint stress and joint remodeling. This finding is sustained by the work of Souza et al. [

21], who demonstrated associations between capsule thickness, elastography changes, and radiographic grading. The FHSs showed weaker correlations, which may reflect the fact that loss of sphericity is a more gradual morphological alteration, occurring later than capsular or bone proliferative changes [

14]. Overall, these results suggest that ultrasound parameters are not only useful in categorical comparisons but also alter proportionally with disease severity and progression, highlighting the novelty and clinical relevance of the present study.

In the present study, the standardized longitudinal femoral head–neck plane in a ventral approach to the ventral hip joint was chosen because it has been shown to provide consistent sonoanatomic landmarks and high reproducibility for evaluating joint capsule thickness, femoral head contour, and head–neck transition morphology [

17]. This plane also minimizes acoustic shadowing from the pelvis and allows direct assessment of periarticular remodeling, making it particularly suited for studies in adult dogs where chronic changes predominate. In contrast, the transverse femoral head-neck plane is mainly recommended for detecting increased synovial volume, and joint recess changes, which are early indicators of joint instability and inflammation [

11,

17,

19]. These features are especially valuable in young dogs during the initial stages of CHD, when effusion may be present before structural remodeling is evident [

17]. However, in adult dogs, where the disease has typically progressed to include capsular thickening, femoral head deformation, femoral head-neck transition type and osteophyte development, such findings are more discriminative. For this reason, we focused on the longitudinal plane, as it provides more relevant information in the context of chronic CHD changes, while acknowledging that transverse and cranial recess assessments remain important for the early diagnosis of CHD in younger animals.

Breed variability is a common limitation in CHD studies due to different joint conformation and soft tissue proportions. By normalizing the joint capsule thickness using the body weight, we attempted to decrease the variability, which may ease a better inter-breed comparison and improve the reproducibility of results. This kind of normalization is common in canine hip research [

7]. Moreover, a more homogeneous sampling should also be attempted in future research.

Lastly, this study focused on a single standardized ultrasonographic view. While this ensured consistency and practical applicability, it may fail to detect some soft tissue and bone structure changes that may have been visible in other US approaches. Future studies should explore multimodal US planes, interobserver reliability, and longitudinal assessment of dogs as they progress through dysplastic changes.

5. Conclusions

Ultrasound of the canine hip joints using the standardized longitudinal femoral head–neck approach detects imaging-relevant differences in the CTFHi, FHSs, FHNTs, and Os between dogs with different degrees of radiographic CHD, according to the FCI grading scheme. Correlations were found between the US parameters assessed. These findings support the use of US as an alternative screening tool to enhance the assessment of CHD, highlighting the clinical relevance of this study.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.T. and M.G.; methodology, I.T. and M.G.; validation, I.T. and M.G.; formal analysis, I.T. and M.G.; investigation, I.T. and M.G.; data curation, I.T.; writing—original draft preparation, I.T.; writing—review and editing, S.A-P., B.C. and M.G.; visualization, X.X.; supervision, M.G.; project administration, M.G.; funding acquisition, B.C. and M.G.

Funding

This research was funded by the projects UIDB/00772/2020 (Doi:10.54499/UIDB/00772/2020) funded by the Portuguese Foundation for Science and Technology (FCT).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the European and National legislation on the protection of animals used for scientific purposes (European Directive 2010/63/EU and National Decree-Law 113/2013) and was approved by the Ethics Committee (Doc84-CE-UTAD-2023) and the Responsible Body for Animal Welfare at UTAD (ORBEA nº 3180-e-HV-2024).

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CHD |

Canine Hip Dysplasia |

| US |

Ultrasonography |

| FCI |

Fédération Cynologique Internationale |

| CTFHi |

Capsule Thickness at the Femoral Head Index |

| CSFTi |

Capsular-Synovial Fold Thickness Index |

| FHSs |

Femoral Head Shape Score |

| FHNTs |

Femoral Head-Neck Transition Score |

| Os |

Osteophyte Score |

| UTAD |

University of Trás-os-Montes and Alto Douro |

References

- Willemsen, K.; Möring, M.M.; Harlianto, N.I.; Tryfonidou, M.A.; van der Wal, B.C.H.; Weinans, H.; Meij, B.P.; Sakkers, R.J.B. Comparing Hip Dysplasia in Dogs and Humans: A Review. Front Vet Sci 2021, 8, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, T.; McGreevy, P.D. Selection for Breed-Specific Long-Bodied Phenotypes Is Associated with Increased Expression of Canine Hip Dysplasia. Vet J 2010, 183, 266–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohlerth, S.; Geiser, B.; Flückiger, M.; Geissbühler, U. Prevalence of Canine Hip Dysplasia in Switzerland Between 1995 and 2016—A Retrospective Study in 5 Common Large Breeds. Front Vet Sci 2019, 6, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riser, W. The Dysplastic Hip Joint: Radiologic and Histologic Development. Vet Pathol 1975, 12, 279–305. [Google Scholar]

- Henrigson, B.; Norberg, I.; Olssons, S.-E. On the Etiology and Pathogenesis of Hip Dysplasia: A Comparative Review. J Small Anim Pract 1966, 7, 673–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ginja, M.M.D.; Silvestre, A.M.; Gonzalo-Orden, J.M.; Ferreira, A.J.A. Diagnosis, Genetic Control and Preventive Management of Canine Hip Dysplasia: A Review. Vet J 2010, 184, 269–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, G.K.; Biery, D.N.; Gregor, T.P. New Concepts of Coxofemoral Joint Stability and the Development of a Clinical Stress-Radiographic Method for Quantitating Hip Joint Laxity in the Dog. J Am Vet Med Assoc 1990, 196, 59–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osteoarthritis: A Serious Disease. Available online: https://oarsi.org/oarsi-white-paper-oa-serious-disease (accessed on 24 September 2025).

- Dennis, R. Interpretation and Use of BVA/KC Hip Scores in Dogs. Pract 2012, 34, 178–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, W.; Dueland, R.; Meinen, J.; O’Brien, R.; Giuliano, E.; Nordheim, E. Early Detection of Canine Hip Dysplasia: Comparison of Two Palpation and Five Radiographic Methods. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc 1998, 34, 339–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ginja, M.M.D.; Silvestre, A.M.; Colaço, J.; Gonzalo-Orden, J.M.; Melo-Pinto, P.; Orden, M.A.; Llorens-Pena, M.P.; Ferreira, A.J. Hip Dysplasia in Estrela Mountain Dogs: Prevalence and Genetic Trends 1991-2005. Vet J 2009, 182, 275–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soo, M.; Worth, A.J. Canine Hip Dysplasia: Phenotypic Scoring and the Role of Estimated Breeding Value Analysis. N Z Vet J 2015, 63, 69–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flückiger, M. Scoring Radiographs for Canine Hip Dysplasia – The Big Three Organisations in the World. Eur J Companion Anim Pract 2007, 17, 135–140. [Google Scholar]

- Pinna, S.; Tassani, C.; Antonino, A.; Vezzoni, A. Prevalence of Primary Radiographic Signs of Hip Dysplasia in Dogs. Animals 2022, 12, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrig, C.B. Diagnostic Imaging of Osteoarthritis. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract 1997, 27, 777–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roemer, F.W.; Guermazi, A.; Demehri, S.; Wirth, W.; Kijowski, R. Imaging in Osteoarthritis. Osteoarthr Cartil 2022, 30, 913–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomé, I.; Alves-Pimenta, S.; Colaço, B.; Ginja, M. Ultrasonographic Ventral Hip Joint Approach and Relationship with Joint Laxity in Estrela Mountain Dogs. Animals 2025, 15, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Todd-Donato, A.B.; VanDeventer, G.M.; Porter, I.R.; Krotscheck, U. Ultrasound Is an Accurate Imaging Modality for Diagnosing Hip Luxation in Dogs Presenting with Hind Limb Lameness. J Am Vet Med Assoc 2024, 262, 1379–1387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sudula, S. Imaging the Hip Joint in Osteoarthritis: A Place for Ultrasound? Ultrasound 2016, 24, 111–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomé, I.; Alves-Pimenta, S.; Costa, L.; Pereira, J.; Sargo, R.; Brancal, H.; Ginja, G.; Colaço, B. Establishment of an Ultrasound-Guided Protocol for the Assessment of Hip Joint Osteoarthritis in Rabbits – a Sonoanatomic Study. PLoS One 2023, 18, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carneiro, R.K.; da Cruz, I.C.K.; Gasser, B.; Lima, B.; Aires, L.P.N.; Ferreira, M.P.; Uscategui, R.A.R.; Giglio, R.F.; Minto, B.W.; Rossi Feliciano, M.A. B-Mode Ultrasonography and ARFI Elastography of Articular and Peri-Articular Structures of the Hip Joint in Non-Dysplastic and Dysplastic Dogs as Confirmed by Radiographic Examination. BMC Vet Res 2023, 19, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madsen, J.S. The Joint Capsule and Joint Laxity in Dogs with Hip Dysplasia. J Am Vet Med Assoc 1997, 210, 1463–1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomé, I.; Alves-Pimenta, S.; Sargo, R.; Pereira, J.; Colaço, B.; Brancal, H.; Costa, L.; Ginja, M. Mechanical Osteoarthritis of the Hip in a One Medicine Concept: A Narrative Review. BMC Vet Res 2023, 19, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prieur, W.D. Coxarthrosis in the Dog Part I: Normal and Abnormal Biomechanics of the Hip Joint. Vet Surg 1980, 9, 145–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weigel, J.P.; Wasserman, J.F. Biomechanics of the Normal and Abnormal Hip Joint. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract 1992, 22, 513–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vandevelde, B. , Van Ryssen B., Saunders J.H., Kramer M., Van Bree H. Comparison of the ultrasonographic appearance of osteochondrosis lesions in the canine shoulder with radiography, arthrography, and arthroscopy. Vet Radiol Ultrasound 2006, 47, 174–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Lasalle, J.; Alexander, K.; Olive, J.; Laverty, S. Comparisons Among Radiography, Ultrasonography And Computed Tomography For Ex Vivo Characterization Of Stifle Osteoarthritis In The Horse. Vet Radiol Ultrasound 2016, 57, 489–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).