Submitted:

17 April 2024

Posted:

18 April 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Datasets

2.2.1. Soil Sampling and Topsoil Parameter Measurement

2.2.2. Hyperspectral Image Data Acquisition and Data Preprocessing

2.3. Spectral Correction Strategy

2.4. Machine Learning Models

2.4.1. Competitive Adaptive Reweighted Sampling (CARS)

2.4.3. Model Validation

3. Results

3.1. Description of Soil Physical Parameters and SOM Content

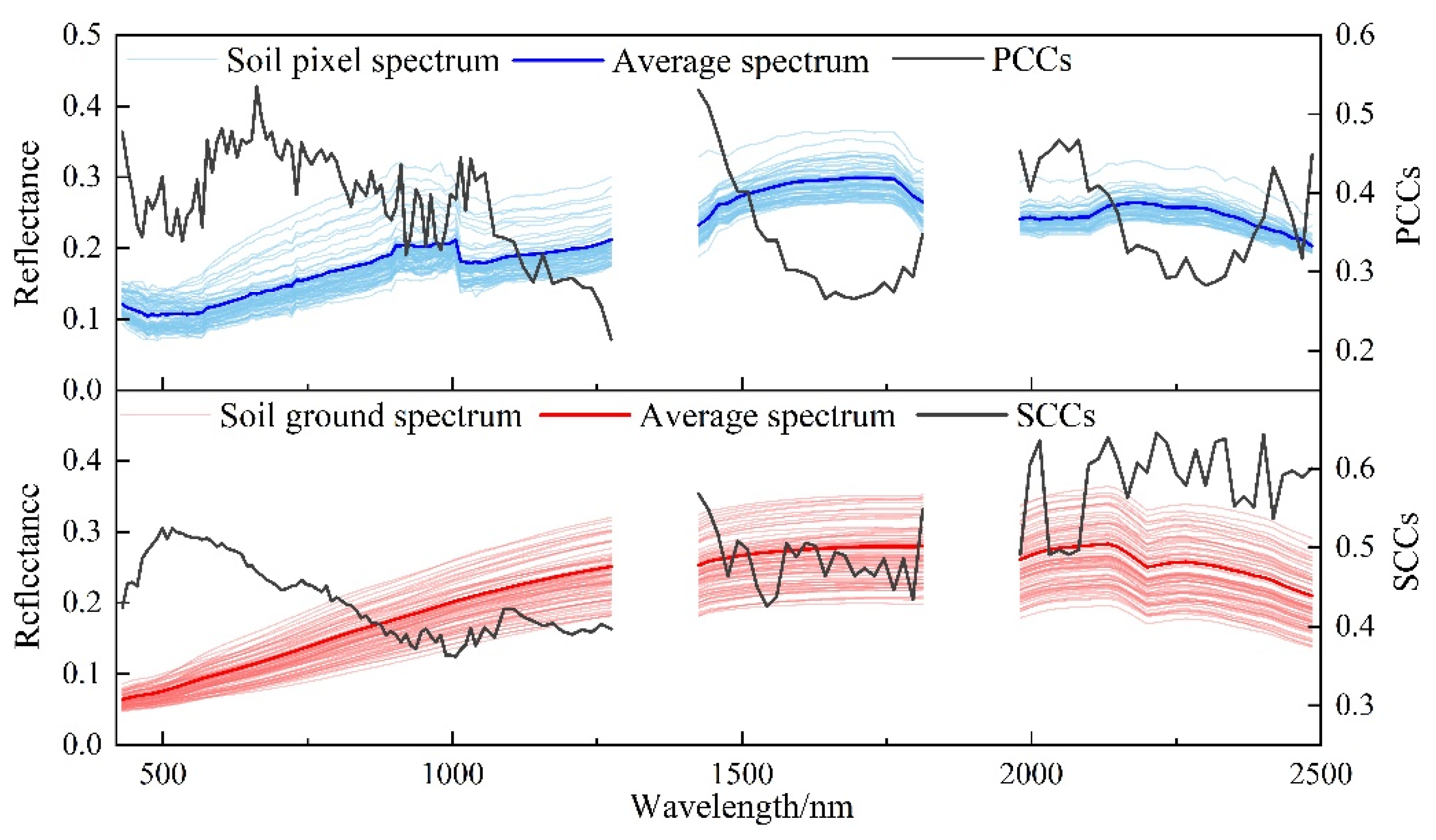

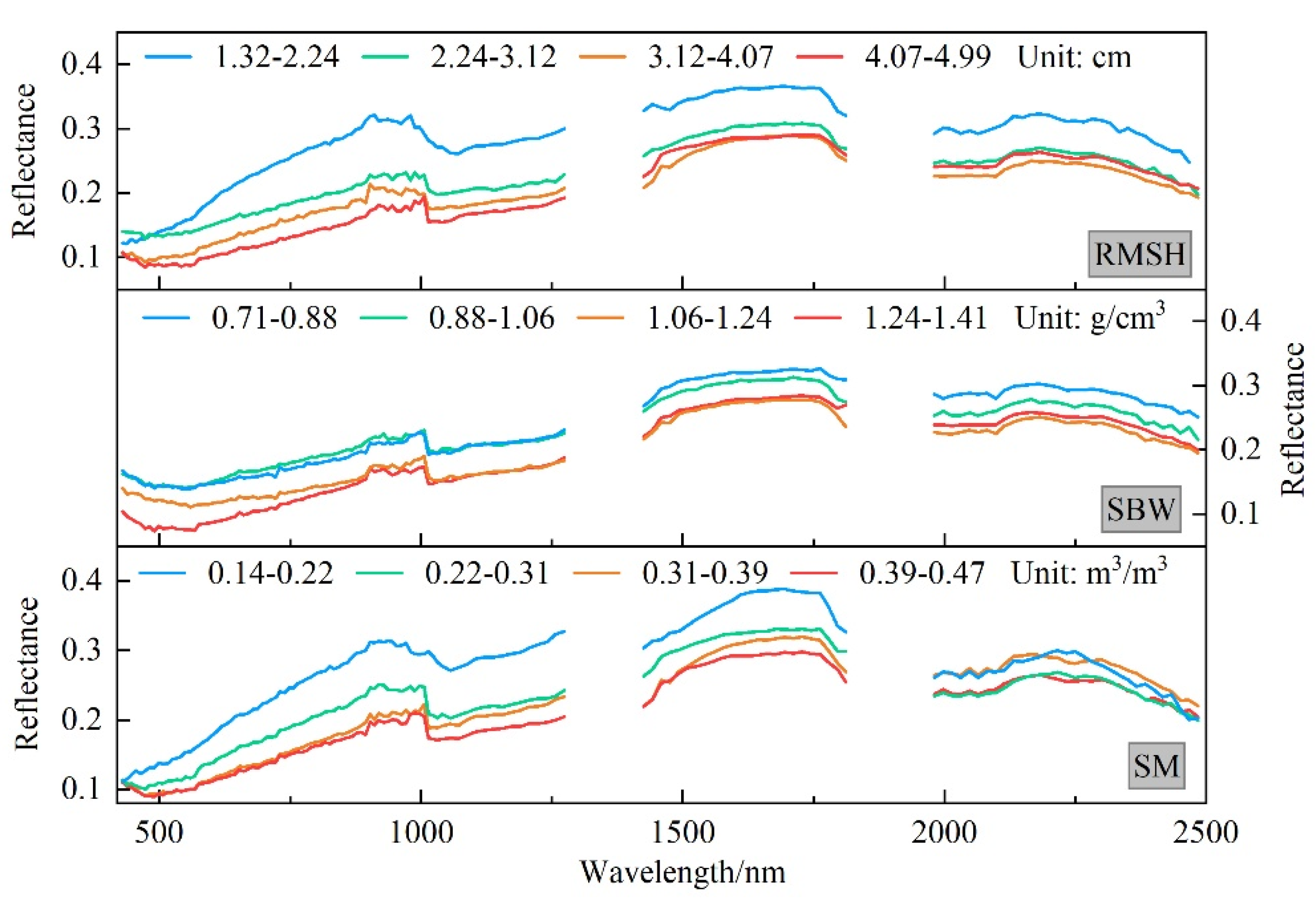

3.2. Effect of Soil Physical Properties on Soil Spectra

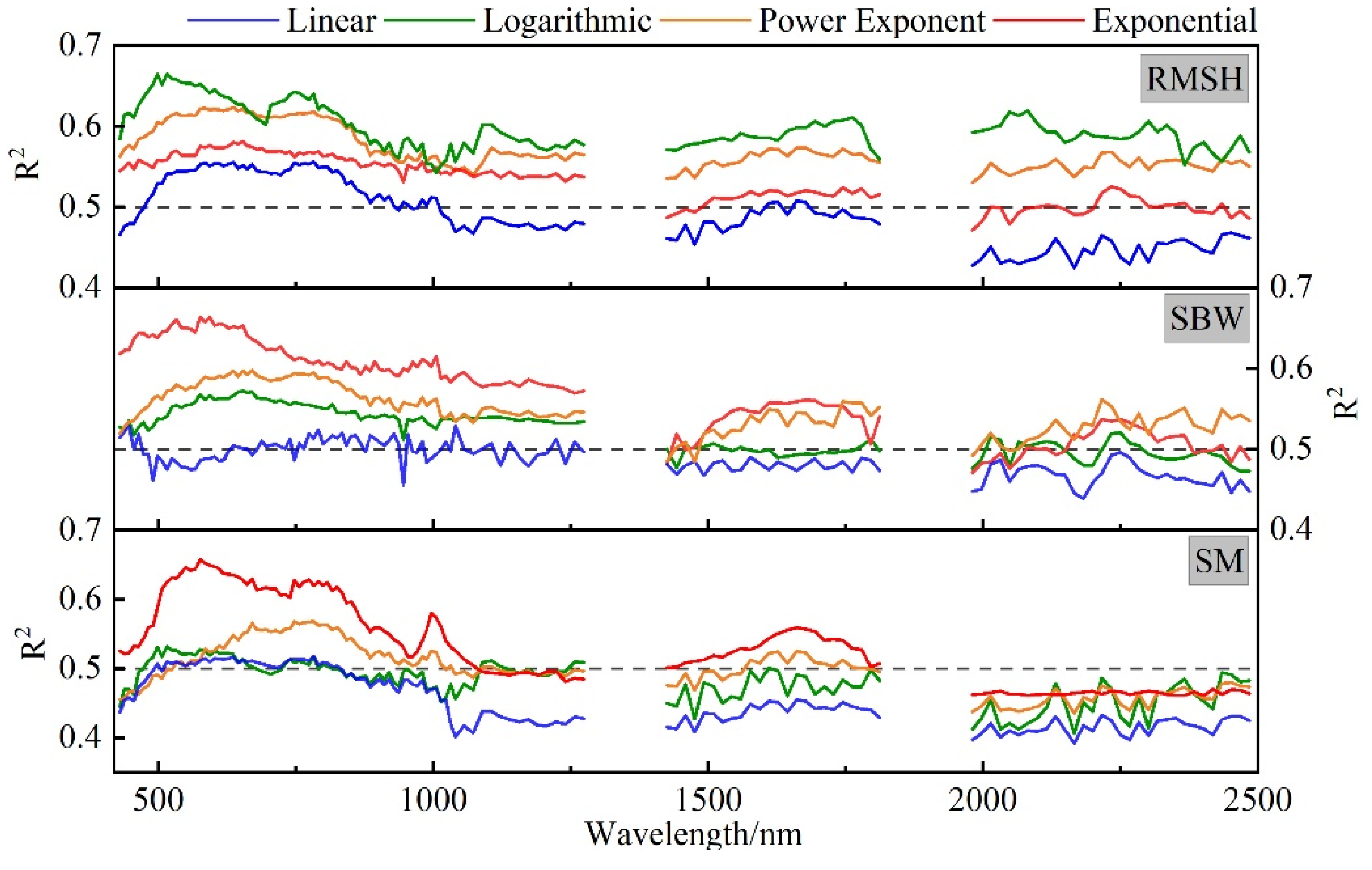

3.3. Empirical Relationship between Satellite Hyperspectral Image and Soil Physical Properties

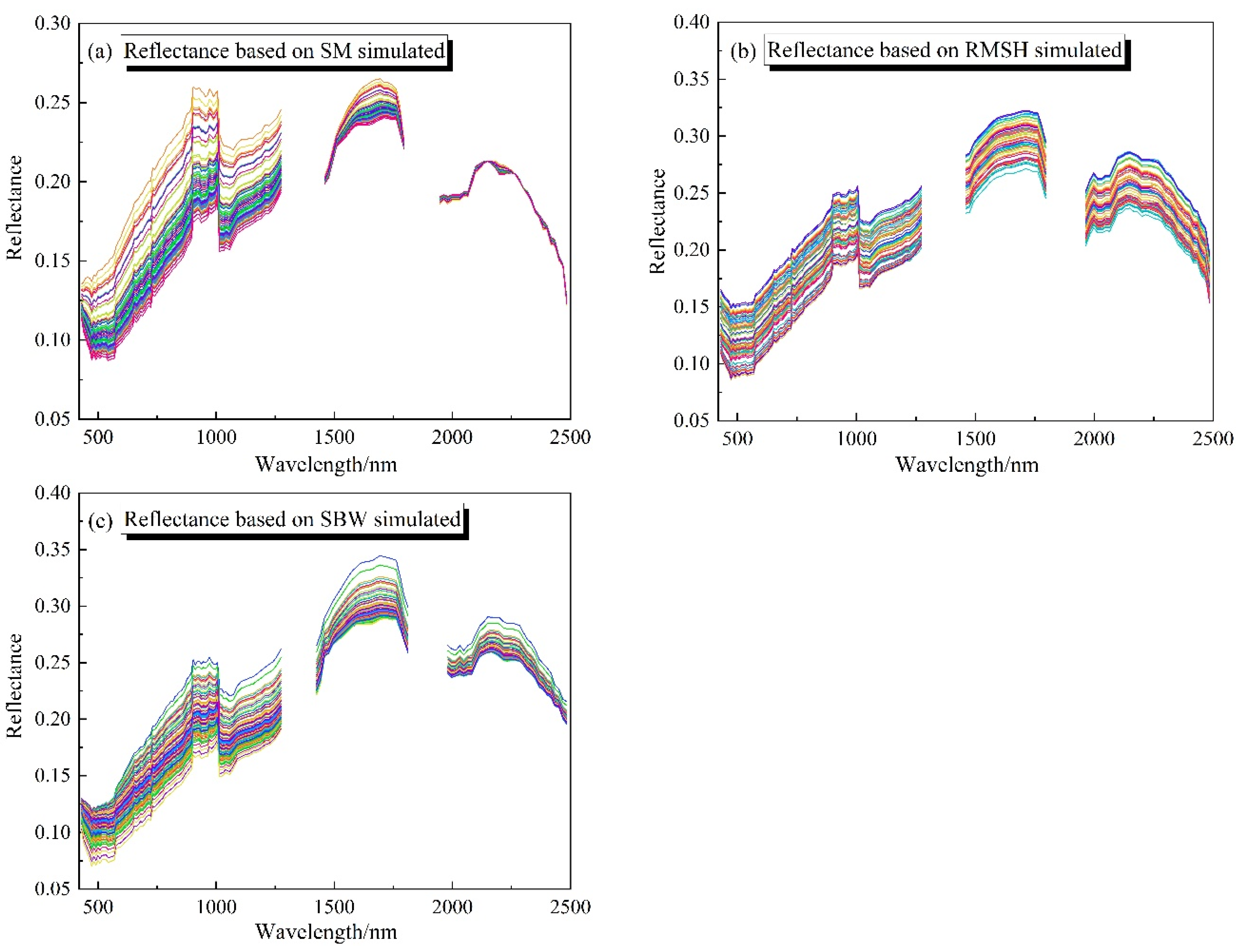

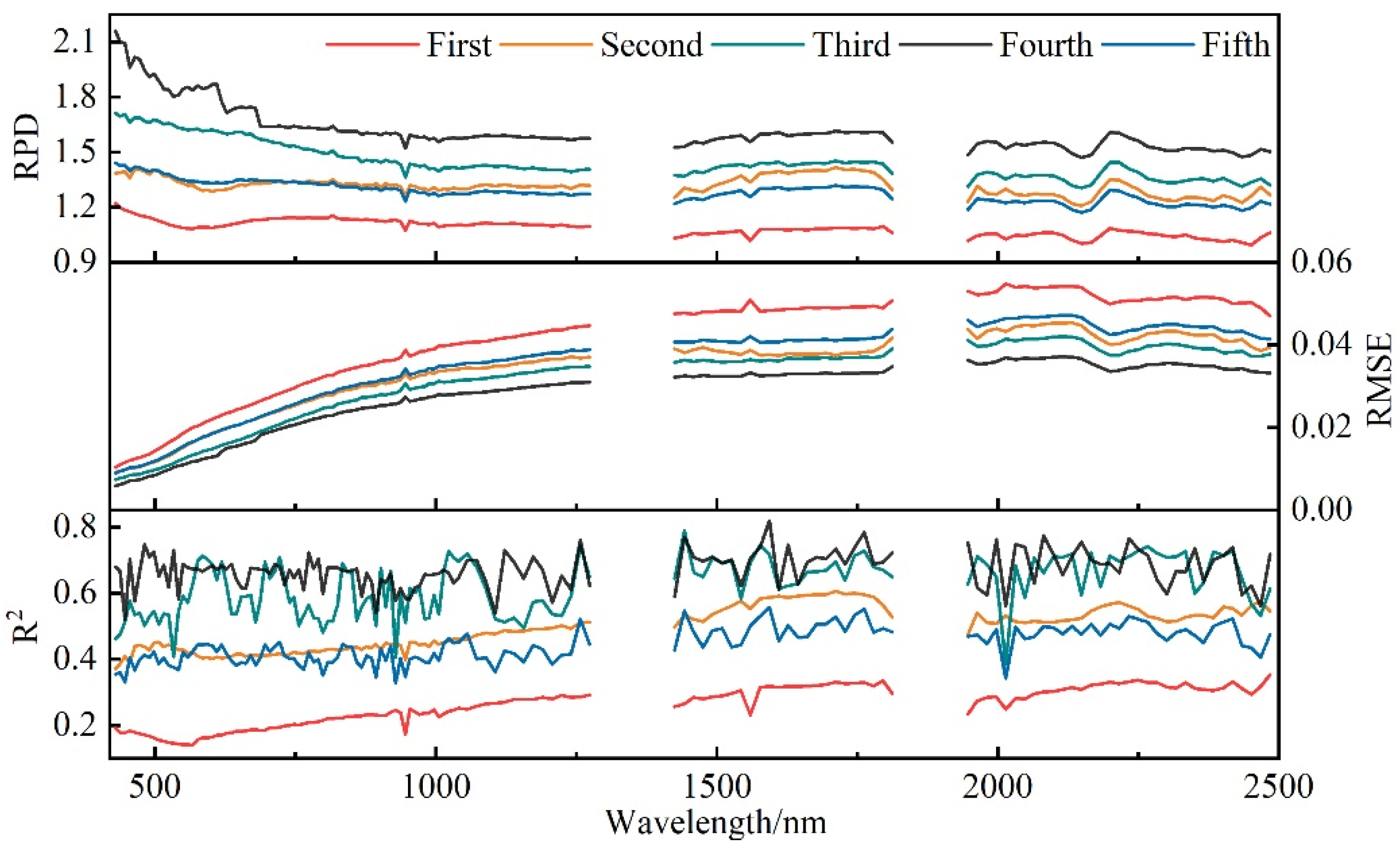

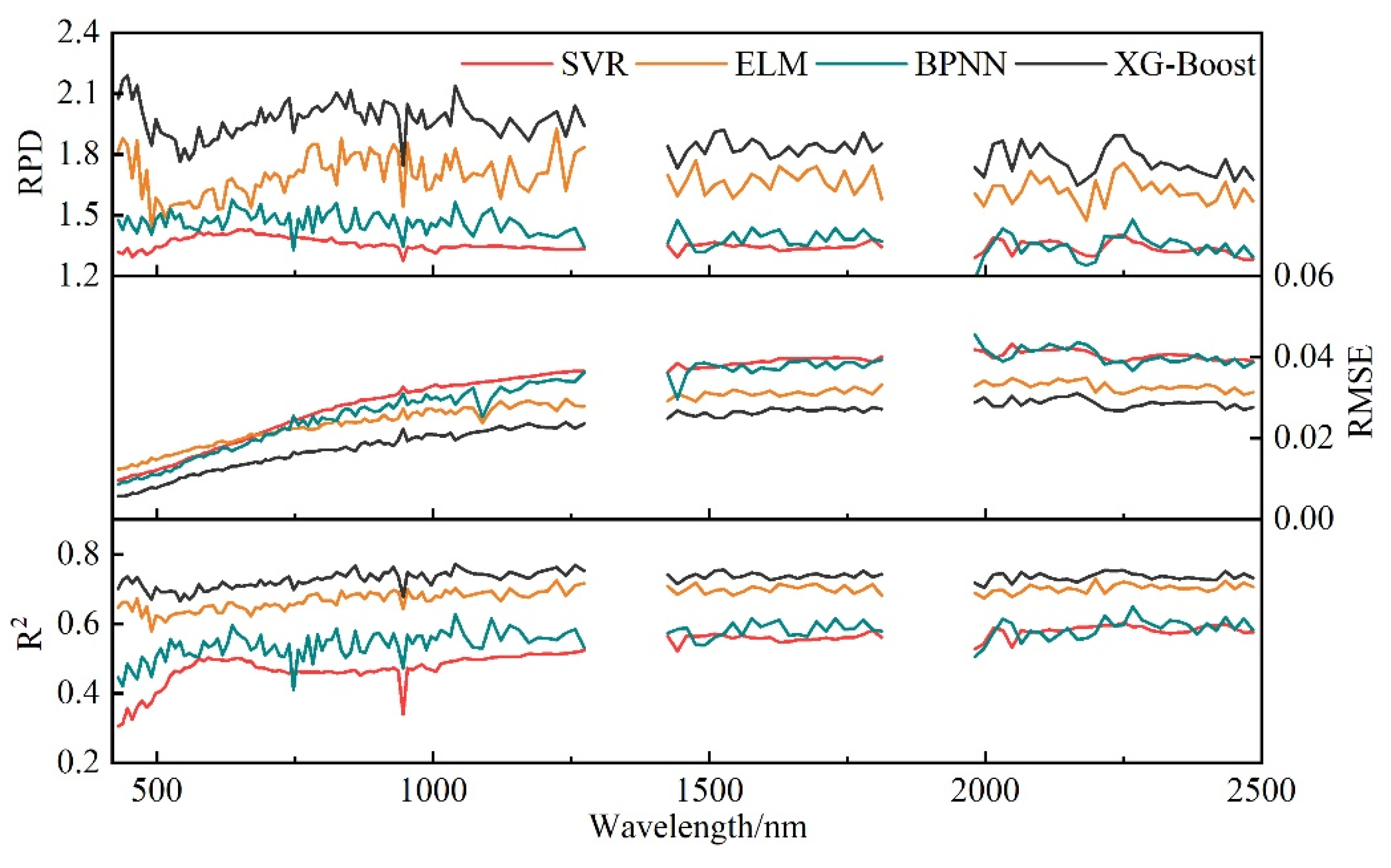

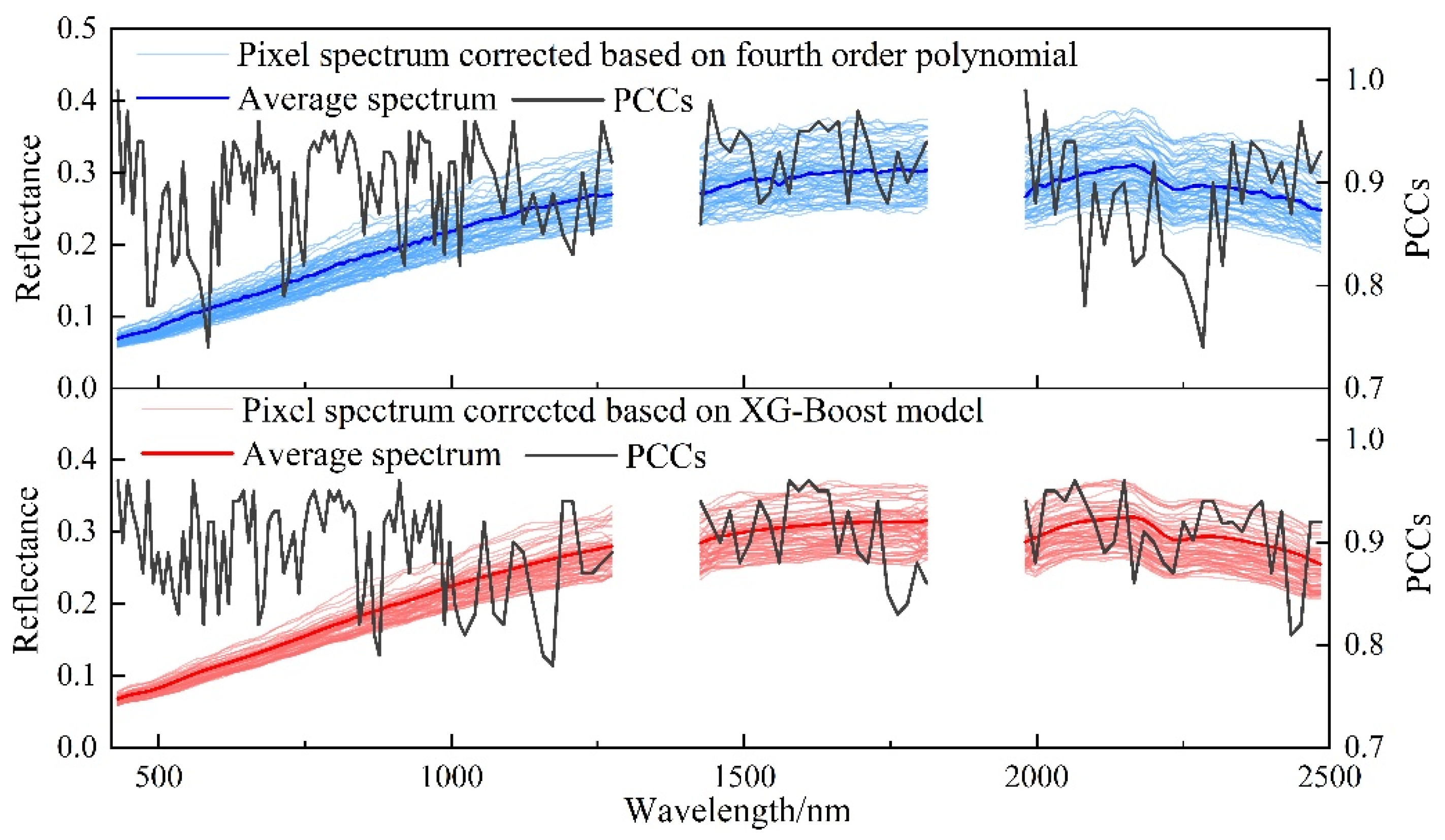

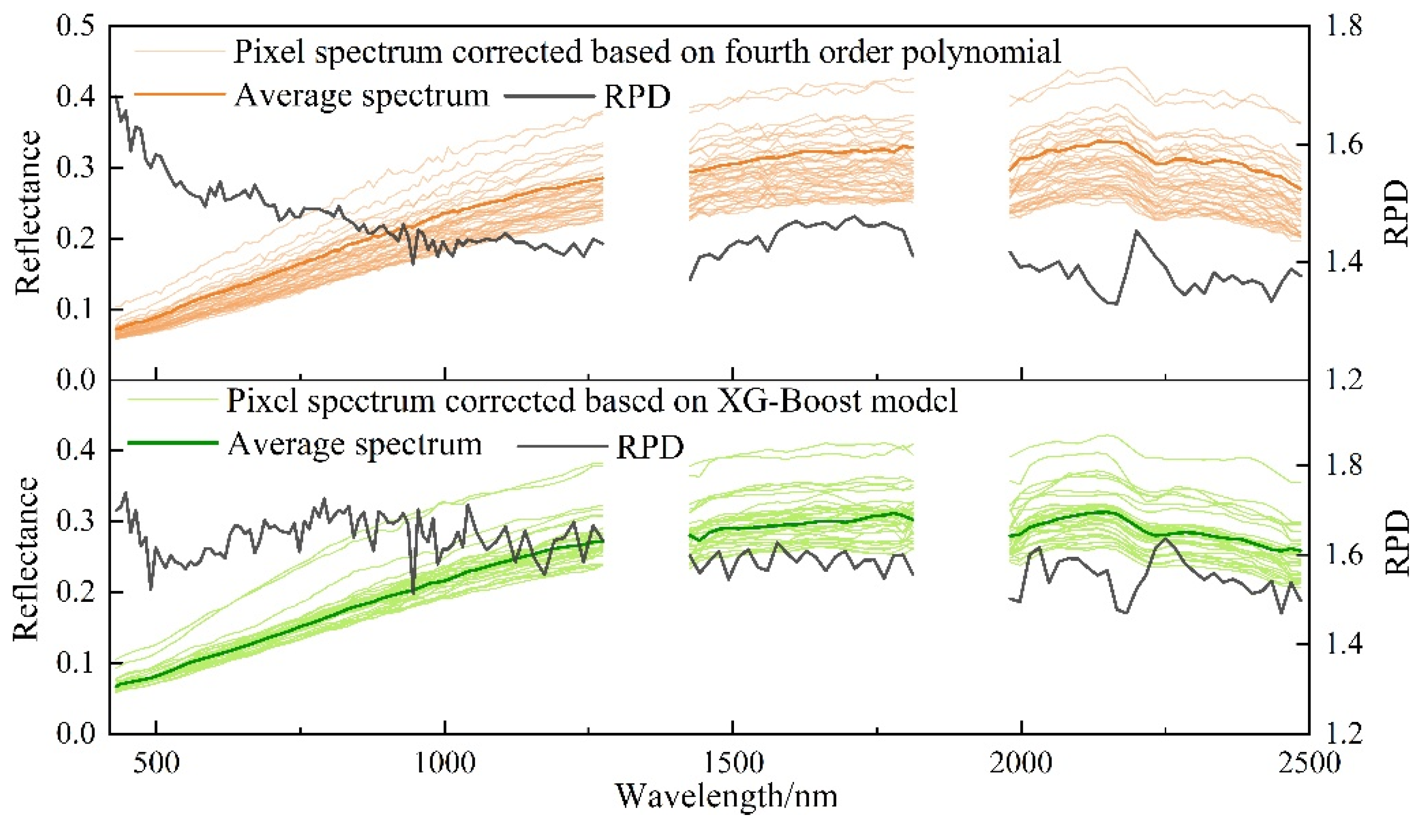

3.4. Modeling of Soil Spectral Correction

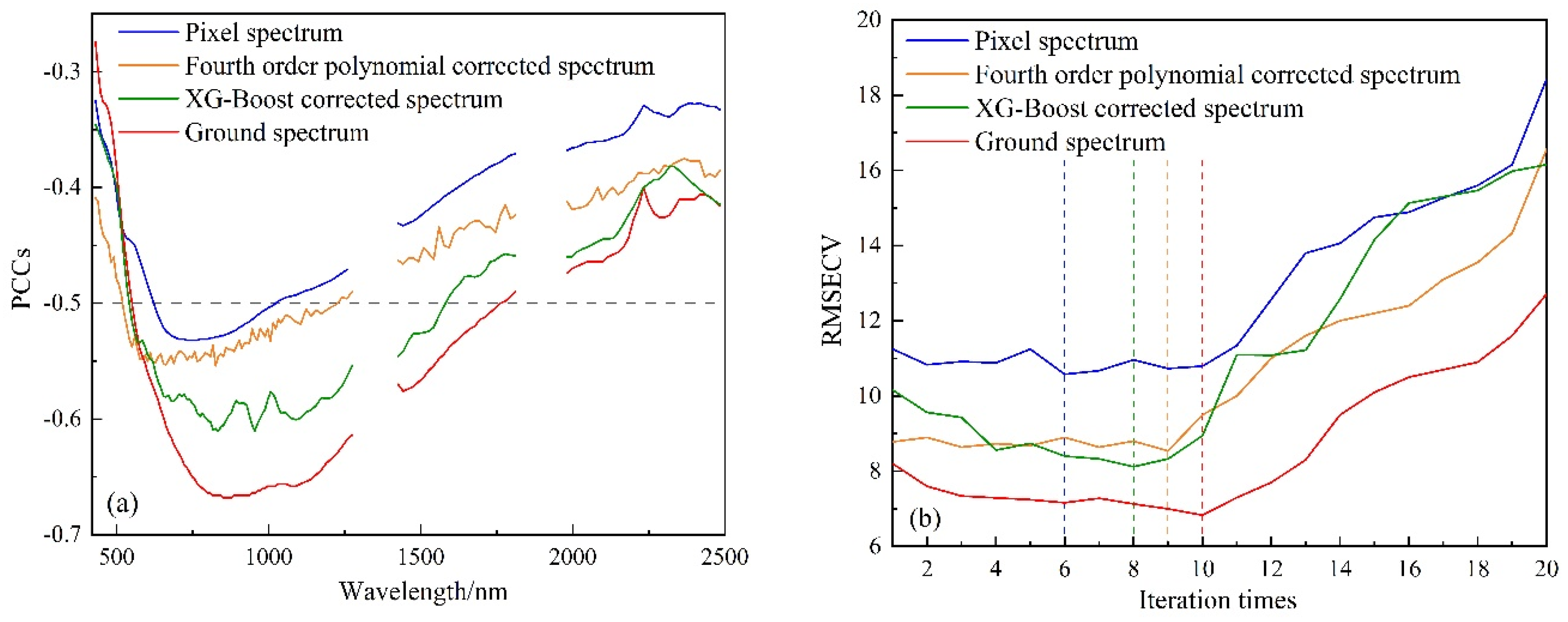

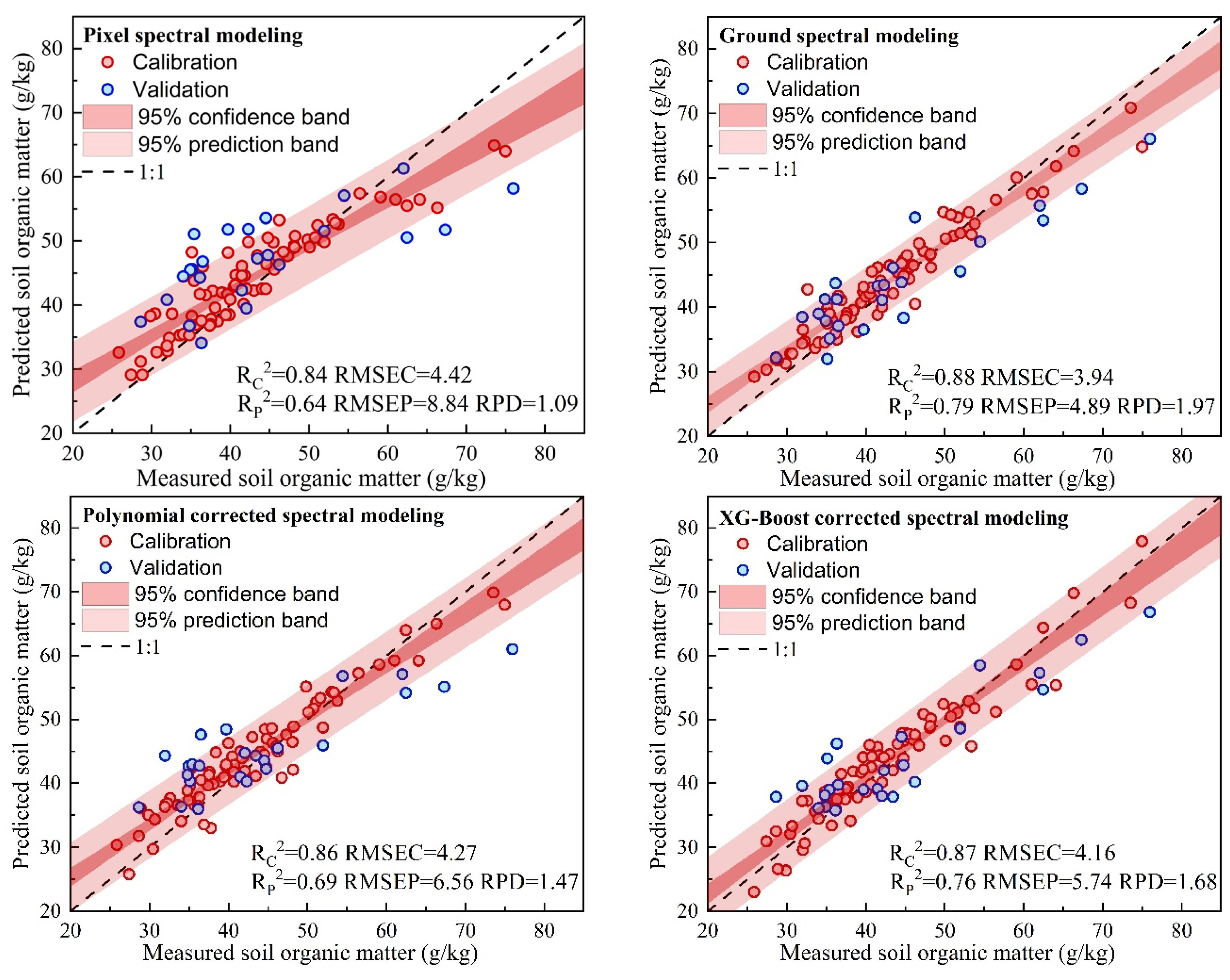

3.5. SOM Content Prediction Accuracy Based on Different Spectral Data

4. Discussion

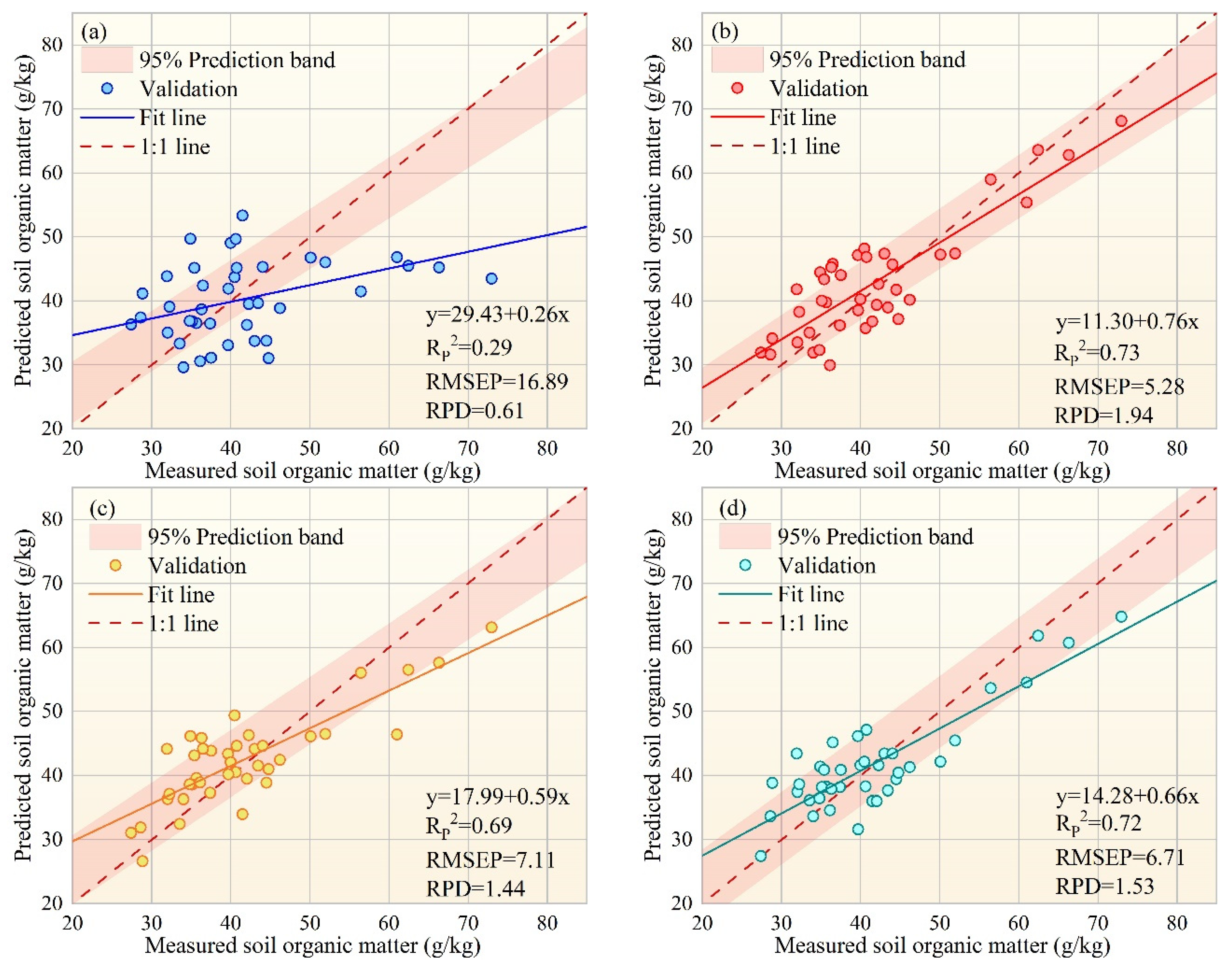

4.1. The Transferability of the Soil Spectral Correction Model and SOM Prediction Model

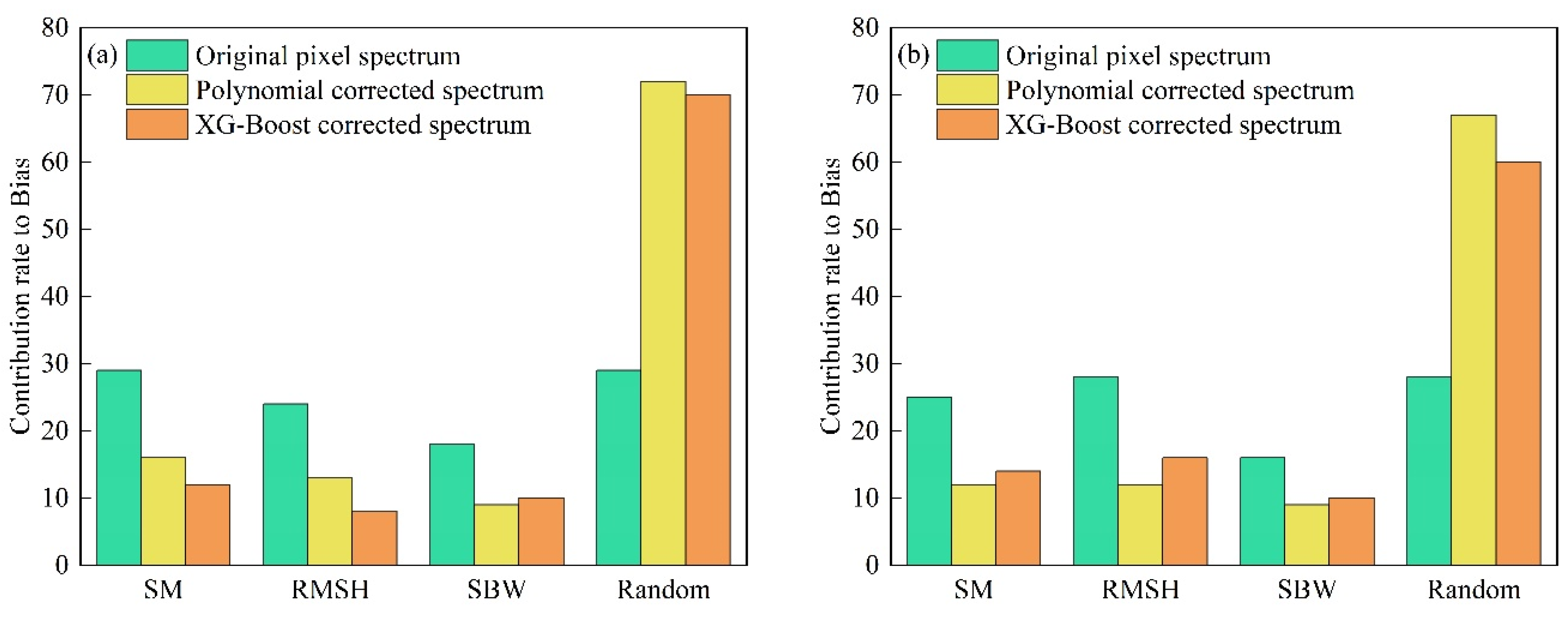

4.2. Contribution of Soil Physical Properties to SOM Content Prediction Bias

4.3. The Potential and Limitations of the Soil Spectral Correction Model

4.4. Future Work and Suggested Next Steps

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lehmann, J.; Kleber, M. The contentious nature of soil organic matter. Nature 2015, 528, 60–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crowther, T.W.; van den Hoogen, J.; Wan, J.; Mayes, M.A.; Keiser, A.D.; Mo, L.; Averill, C.; Maynard, D.S. The global soil community and its influence on biogeochemistry. Science 2019, 365, 772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, T.; Geng, Y.; Chen, J.; Liu, M.; Haase, D.; Lausch, A. Mapping soil organic carbon content using multi-source remote sensing variables in the Heihe River Basin in China. Ecol. Indic. 2020, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, L.; Chu, X.; Qian, J.; Li, J.; Sun, Z. Multi-Scale Stereoscopic Hyperspectral Remote Sensing Estimation of Heavy Metal Contamination in Wheat Soil over a Large Area of Farmland. Agronomy-Basel 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Jin, S.; Zhu, G.; Guo, J. Monitoring of Cropland Abandonment Based on Long Time Series Remote Sensing Data: A Case Study of Fujian Province, China. Agronomy-Basel 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Y.; Chen, S.; Chen, Y.; Linderman, M.; Mouazen, A.M.; Liu, Y.; Guo, L.; Yu, L.; Liu, Y.; Cheng, H.; et al. Comparing laboratory and airborne hyperspectral data for the estimation and mapping of topsoil organic carbon: Feature selection coupled with random forest. Soil Tillage Res. 2020, 199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, G.; Grafton, M.; Pearson, D.; Bretherton, M.; Holmes, A. Integration of Precision Farming Data and Spatial Statistical Modelling to Interpret Field-Scale Maize Productivity. Agriculture-Basel 2019, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuster, J.; Hagn, L.; Mittermayer, M.; Maidl, F.-X.; Huelsbergen, K.-J. Using Remote and Proximal Sensing in Organic Agriculture to Assess Yield and Environmental Performance. Agronomy-Basel 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahmani, S.R.; Ackerson, J.P.; Schulze, D.; Adhikari, K.; Libohova, Z. Digital Mapping of Soil Organic Matter and Cation Exchange Capacity in a Low Relief Landscape Using LiDAR Data. Agronomy-Basel 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Guan, K.; Zhang, C.; Lee, D.; Margenot, A.J.; Ge, Y.; Peng, J.; Zhou, W.; Zhou, Q.; Huang, Y. Using soil library hyperspectral reflectance and machine learning to predict soil organic carbon: Assessing potential of airborne and spaceborne optical soil sensing. Remote Sens. Environ. 2022, 271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelopoulou, T.; Tziolas, N.; Balafoutis, A.; Zalidis, G.; Bochtis, D. Remote Sensing Techniques for Soil Organic Carbon Estimation: A Review. Remote Sens. 2019, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Mu, T.; Liu, G.; Yang, X.; Zhu, G.; Shang, C. A Method of Soil Moisture Content Estimation at Various Soil Organic Matter Conditions Based on Soil Reflectance. Remote Sens. 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, D.; Mu, Y.; Duan, W.; Ye, M.; Song, Y.; Song, Z.; Yao, K.; Sun, D.; Ding, Z. Spatial Prediction and Mapping of Soil Water Content by TPE-GBDT Model in Chinese Coastal Delta Farmland with Sentinel-2 Remote Sensing Data. Agriculture-Basel 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Zhou, Y. Combining Multitemporal Sentinel-2A Spectral Imaging and Random Forest to Improve the Accuracy of Soil Organic Matter Estimates in the Plough Layer for Cultivated Land. Agriculture-Basel 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suleymanov, A.; Gabbasova, I.; Komissarov, M.; Suleymanov, R.; Garipov, T.; Tuktarova, I.; Belan, L. Random Forest Modeling of Soil Properties in Saline Semi-Arid Areas. Agriculture-Basel 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Shang, K.; Xiao, C.; Wang, C.; Tang, H. Spectral Index for Mapping Topsoil Organic Matter Content Based on ZY1-02D Satellite Hyperspectral Data in Jiangsu Province, China. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, X.; Bao, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Liu, H. An advanced soil organic carbon content prediction model via fused temporal-spatial-spectral (TSS) information based on machine learning and deep learning algorithms. Remote Sens. Environ. 2022, 280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, C.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, X.; Liu, H. Mapping of soil organic matter in a typical black soil area using Landsat-8 synthetic images at different time periods. Catena 2023, 231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, C.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, W.; Liu, H. Spatial prediction of soil organic matter content using multiyear synthetic images and partitioning algorithms. Catena 2022, 211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Croft, H.; Anderson, K.; Kuhn, N.J. Evaluating the influence of surface soil moisture and soil surface roughness on optical directional reflectance factors. Eur. J. Soil Sci. 2014, 65, 605–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castaldi, F.; Palombo, A.; Pascucci, S.; Pignatti, S.; Santini, F.; Casa, R. Reducing the Influence of Soil Moisture on the Estimation of Clay from Hyperspectral Data: A Case Study Using Simulated PRISMA Data. Remote Sens. 2015, 7, 15561–15582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prudnikova, E.; Savin, I. Some Peculiarities of Arable Soil Organic Matter Detection Using Optical Remote Sensing Data. Remote Sens. 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Gao, J.; Zhuang, Q.; Lu, Y.; Gu, H.; Jin, X. Multispectral Remote Sensing Data Are Effective and Robust in Mapping Regional Forest Soil Organic Carbon Stocks in a Northeast Forest Region in China. Remote Sens. 2020, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castaldi, F.; Hueni, A.; Chabrillat, S.; Ward, K.; Buttafuoco, G.; Bomans, B.; Vreys, K.; Brell, M.; van Wesemael, B. Evaluating the capability of the Sentinel 2 data for soil organic carbon prediction in croplands. ISPRS-J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2019, 147, 267–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rienzi, E.A.; Mijatovic, B.; Mueller, T.G.; Matocha, C.J.; Sikora, F.J.; Castrignano, A. Prediction of Soil Organic Carbon under Varying Moisture Levels using Reflectance Spectroscopy. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 2014, 78, 958–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhou, L.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, L.; Yao, X.; Shi, K.; Jeppesen, E.; Yu, Q.; Zhu, W. Chromophoric dissolved organic matter in inland waters: Present knowledge and future challenges. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yue, J.; Tian, Q.; Tang, S.; Xu, K.; Zhou, C. A dynamic soil endmember spectrum selection approach for soil and crop residue linear spectral unmixing analysis. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2019, 78, 306–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ou, D.; Tan, K.; Li, J.; Wu, Z.; Zhao, L.; Ding, J.; Wang, X.; Zou, B. Prediction of soil organic matter by Kubelka-Munk based airborne hyperspectral moisture removal model. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2023, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.; Zhu, A.X.; Wang, Z.; Wang, X.; Ma, R. The refined spatiotemporal representation of soil organic matter based on remote images fusion of Sentinel-2 and Sentinel-3. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2020, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gholizadeh, A.; Zizala, D.; Saberioon, M.; Boruvka, L. Soil organic carbon and texture retrieving and mapping using proximal, airborne and Sentinel-2 spectral imaging. Remote Sens. Environ. 2018, 218, 89–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiorentini, M.; Zenobi, S.; Orsini, R. Remote and Proximal Sensing Applications for Durum Wheat Nutritional Status Detection in Mediterranean Area. Agriculture-Basel 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelsamie, E.A.; Abdellatif, M.A.; Hassan, F.O.; El Baroudy, A.A.; Mohamed, E.S.; Kucher, D.E.; Shokr, M.S. Integration of RUSLE Model, Remote Sensing and GIS Techniques for Assessing Soil Erosion Hazards in Arid Zones. Agriculture-Basel 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendes, W.d.S.; Sommer, M. Advancing Soil Organic Carbon and Total Nitrogen Modelling in Peatlands: The Impact of Environmental Variable Resolution and vis-NIR Spectroscopy Integration. Agronomy-Basel 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fathizad, H.; Taghizadeh-Mehrjardi, R.; Ardakani, M.A.H.; Zeraatpisheh, M.; Heung, B.; Scholten, T. Spatiotemporal Assessment of Soil Organic Carbon Change Using Machine-Learning in Arid Regions. Agronomy-Basel 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, X.; Ding, J.; Teng, D.; Wang, J.; Huo, T.; Jin, X.; Wang, J.; He, B.; Han, L. Updated soil salinity with fine spatial resolution and high accuracy: The synergy of Sentinel-2 MSI, environmental covariates and hybrid machine learning approaches. Catena 2022, 212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.; Zhang, X.; Liu, H.; Wu, D.; Dou, X.; Xu, M.; Jiang, Y. Remote sensing inversion of soil organic matter by using the subregion method at the field scale. Precis. Agric. 2022, 23, 1813–1835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minasny, B.; McBratney, A.B.; Bellon-Maurel, V.; Roger, J.-M.; Gobrecht, A.; Ferrand, L.; Joalland, S. Removing the effect of soil moisture from NIR diffuse reflectance spectra for the prediction of soil organic carbon. Geoderma 2011, 167-68, 118–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Zhao, K.; Jiang, T.; Li, X.; Zheng, X.; Wan, X.; Zhao, X. Predicting Surface Roughness and Moisture of Bare Soils Using Multiband Spectral Reflectance Under Field Conditions. Chin. Geogr. Sci. 2018, 28, 986–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmisano, D.; Satalino, G.; Balenzano, A.; Mattia, F. Coherent and Incoherent Change Detection for Soil Moisture Retrieval From Sentinel-1 Data. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2022, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.S.; Wu, T.D.; Tsang, L.; Li, Q.; Shi, J.C.; Fung, A.K. Emission of rough surfaces calculated by the integral equation method with comparison to three-dimensional moment method Simulations. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sensing 2003, 41, 90–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, J.; Wang, X.; Yan, C.-x.; Wang, S.-r.; Ju, X.-p.; Li, Y. Soil Moisture Retrieval Model for Remote Sensing Using Reflected Hyperspectral Information. Remote Sens. 2019, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Li, P.; Pu, Z.; Chen, X. Calibration and validation of salt-resistant hyperspectral indices for estimating soil moisture in arid land. J. Hydrol. 2011, 408, 276–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, C.; Fang, H. GSV: a general model for hyperspectral soil reflectance simulation. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2019, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, J.; Crawford, M.M. Spectral Unmixing-Based Crop Residue Estimation Using Hyperspectral Remote Sensing Data: A Case Study at Purdue University. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Observ. Remote Sens. 2014, 7, 2531–2539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; He, X.; Shen, F.; Zhou, C.; Zhu, A.X.; Gao, B.; Chen, Z.; Li, M. Improving prediction of soil organic carbon content in croplands using phenological parameters extracted from NDVI time series data. Soil Tillage Res. 2020, 196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, M.; Shi, X. Determination of rice root density from Vis-NIR spectroscopy by support vector machine regression and spectral variable selection techniques. Catena 2017, 157, 12–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esteves, C.; Fangueiro, D.; Braga, R.P.; Martins, M.; Botelho, M.; Ribeiro, H. Assessing the Contribution of EC<sub>a</sub> and NDVI in the Delineation of Management Zones in a Vineyard. Agronomy-Basel 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, M.; Cai, Q.; Zhu, A.; Fan, H. Soil erosion along a long slope in the gentle hilly areas of black soil region in Northeast China. J. Geogr. Sci. 2007, 17, 375–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suleman, M.M.; Xu, H.; Zhang, W.; Nizamuddin, D.; Xu, M. Soil microbial biomass carbon and carbon dioxide response by glucose-C addition in black soil of China. Soil Environ. 2019, 38, 48–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ou, Y.; Rousseau, A.N.; Wang, L.; Yan, B. Spatio-temporal patterns of soil organic carbon and pH in relation to environmental factors-A case study of the Black Soil Region of Northeastern China. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2017, 245, 22–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koegel-Knabner, I.; Guggenberger, G.; Kleber, M.; Kandeler, E.; Kalbitz, K.; Scheu, S.; Eusterhues, K.; Leinweber, P. Organo-mineral associations in temperate soils:: Integrating biology, mineralogy, and organic matter chemistry. J. Plant Nutr. Soil Sci. 2008, 171, 61–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, N.; Jiang, R.; Li, G.; Yang, Q.; Li, D.; Yang, X. Estimating the heavy metal contents in farmland soil from hyperspectral images based on Stacked AdaBoost ensemble learning. Ecol. Indic. 2022, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.; Feng, Z.; Li, L.; Li, B.; Jiang, T.; Li, X.; Li, X.; Chen, S. Simultaneously estimating surface soil moisture and roughness of bare soils by combining optical and radar data. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2021, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Tan, Y.; Abd-Elrahman, A.; Fan, T.; Wang, Q. Incorporation of Fused Remote Sensing Imagery to Enhance Soil Organic Carbon Spatial Prediction in an Agricultural Area in Yellow River Basin, China. Remote Sens. 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, K.; Ma, W.; Chen, L.; Wang, H.; Du, Q.; Du, P.; Yan, B.; Liu, R.; Li, H. Estimating the distribution trend of soil heavy metals in mining area from HyMap airborne hyperspectral imagery based on ensemble learning. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, N.; Fu, J.; Jiang, R.; Li, G.; Yang, Q. Lithological Classification by Hyperspectral Images Based on a Two-Layer XGBoost Model, Combined with a Greedy Algorithm. Remote Sens. 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, X.; Ding, J.; Teng, D.; Xie, B.; Zhang, X.; Wang, J.; Han, L.; Bao, Q.; Wang, J. Exploring the capability of Gaofen-5 hyperspectral data for assessing soil salinity risks. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2022, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, L.; Sun, X.; Fu, P.; Shi, T.; Dang, L.; Chen, Y.; Linderman, M.; Zhang, G.; Zhang, Y.; Jiang, Q.; et al. Mapping soil organic carbon stock by hyperspectral and time-series multispectral remote sensing images in low-relief agricultural areas. Geoderma 2021, 398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honarbakhsh, A.; Tahmoures, M.; Afzali, S.F.; Khajehzadeh, M.; Ali, M.S. Remote sensing and relief data to predict soil saturated hydraulic conductivity in a calcareous watershed, Iran. Catena 2022, 212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Chen, J.; Guo, L.; Wang, J.; Zhou, Z.; Luo, J.; Yang, R. Prediction of soil organic carbon in soil profiles based on visible-near-infrared hyperspectral imaging spectroscopy. Soil Tillage Res. 2023, 232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, R.-M.; Guo, W.-W. Modelling of soil organic carbon and bulk density in invaded coastal wetlands using Sentinel-1 imagery. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2019, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, L.; Zhu, X.; Han, Z.; Wang, L.; Zhao, G.; Jiang, Y. Spectroscopy-Based Soil Organic Matter Estimation in Brown Forest Soil Areas of the Shandong Peninsula, China. Pedosphere 2019, 29, 810–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selige, T.; Boehner, J.; Schmidhalter, U. High resolution topsoil mapping using hyperspectral image and field data in multivariate regression modeling procedures. Geoderma 2006, 136, 235–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krzyszczak, J.; Baranowski, P.; Pastuszka, J.; Wesolowska, M.; Cymerman, J.; Slawinski, C.; Siedliska, A. Assessment of soil water retention characteristics based on VNIR/SWIR hyperspectral imaging of soil surface. Soil Tillage Res. 2023, 233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eshqi Molan, Y.; Lu, Z. Modeling InSAR Phase and SAR Intensity Changes Induced by Soil Moisture. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sensing 2020, 58, 4967–4975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Hateren, T.C.C.; Chini, M.; Matgen, P.; Pulvirenti, L.; Pierdicca, N.; Teuling, A.J.J. On the Use of Native Resolution Backscatter Intensity Data for Optimal Soil Moisture Retrieval. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2023, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Lin, H.; Wang, M.; Liu, X.; Chen, Q.; Wang, C.; Zhang, H. A Review of Satellite Synthetic Aperture Radar Interferometry Applications in Permafrost Regions: Current Status, Challenges, and Trends. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Mag. 2022, 10, 93–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shilpa, K.; Raju, C.S.; Mandal, D.; Rao, Y.S.; Shetty, A. Soil Moisture Retrieval Over Crop Fields from Multi-polarization SAR Data. J. Indian Soc. Remote Sens. 2023, 51, 949–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Specification | Parameters |

|---|---|

| Spectral range (nm) | 400-2500 |

| Channels | 76 (VNIR), 90 (SWIR) |

| Spectral resolution (nm) | 10 (VNIR), 20 (SWIR) |

| Swath width (km) | 60 |

| Spatial resolution (m) | 30 |

| Revisit cycle (d) | 3 |

| Lateral swing capacity (°) | ±26 |

| Dataset | Unit | Site 1 | Site 2 | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Min | Max | Mean | SD | CV % | Min | Max | Mean | SD | CV % | ||

| SM | cm3/cm3 | 0.14 | 0.47 | 0.25 | 0.08 | 31.99 | 0.21 | 0.63 | 0.37 | 0.14 | 37.93 |

| RMSH | cm | 1.32 | 4.99 | 2.49 | 0.77 | 30.92 | 2.04 | 5.78 | 3.65 | 1.34 | 36.71 |

| SBW | g/cm3 | 0.71 | 1.41 | 0.98 | 0.15 | 15.31 | 0.85 | 1.51 | 1.13 | 0.18 | 15.92 |

| SOM | g/kg | 25.84 | 75.97 | 43.25 | 10.51 | 24.30 | 27.40 | 72.97 | 41.57 | 10.28 | 24.72 |

| Spectral correction method | Wavelength (unit: um) | Total |

|---|---|---|

| Pixel spectrum | 0.67, 0.68, 0.70, 0.72, 0.74, 0.77, 0.79, 0.84, 0.87, 0.90, 0.93 | 11 |

| Fourth-order polynomial corrected spectrum | 0.55, 0.60, 0.62, 0.68, 0.73, 0.76, 0.78, 0.82, 0.85, 0.87, 0.91, 0.96, 0.99, 1.07 | 14 |

| XG-Boost corrected spectrum | 0.55, 0.62, 0.64, 0.69, 0.73, 0.77, 0.81, 0.83, 0.87, 0.89, 0.92, 0.94, 0.99, 1.05, 1.17 | 15 |

| Ground-based spectrum | 060, 0.63, 0.67, 0.70, 0.73, 0.77, 0.81, 0.85, 0.87, 0.90, 0.91, 0.96, 0.99, 1.03, 1.08, 1.22 | 16 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).