Submitted:

09 April 2024

Posted:

11 April 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

Urban Segregation and the Dynamics of Micro-Segregation

The affective bond between people and places

Identity and Segregation of Urban Spaces: Emerging Controversies Over Public and Green Areas

2. Research Context

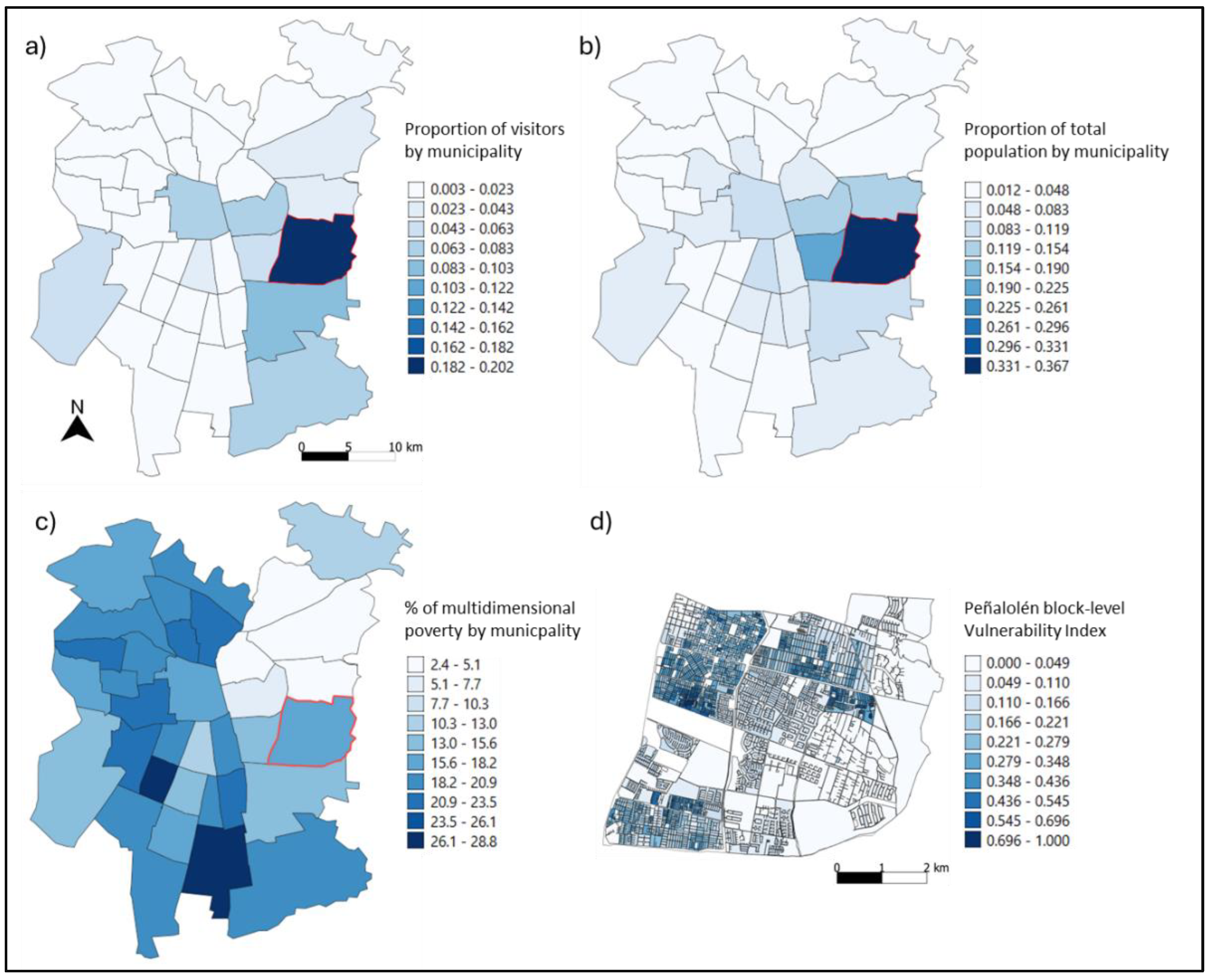

Area of Study

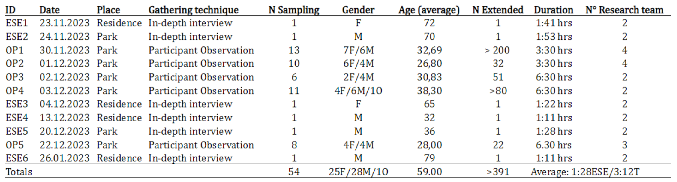

3. Materials and Methods

- Research approach

3. Results

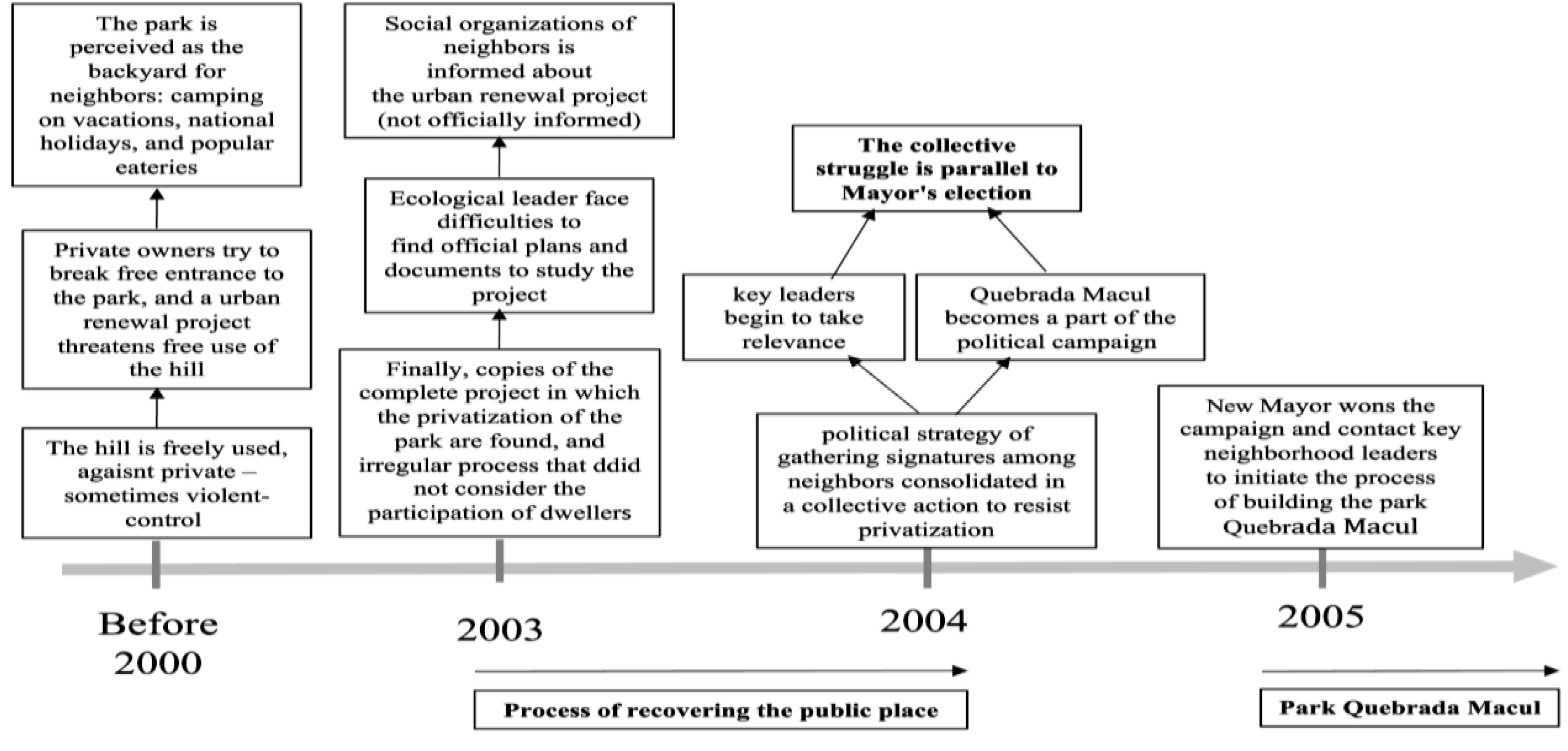

3.1. From the mountain hill to the public park: history of an intergroup conflict

“People said ‘let’s go up and stay there’, 'I used to date up there’, said people. I remember popular eateries -’fondas’- that were done in the hill. There were a lot, a lot of people saying that the hill belonged to them”.(Javiera, 65 years old, parr. 84)

"We used to come with my uncles during the summer. I was five and a half, almost six years old. And I am 79 years old, so we have been coming here for a little while now...".(Bernardita, 79 years old, parr. 6)

“I told him [another social leader from the neighborhood] ‘there is an already approved project and, from the study I have been doing, I understand it means that the Quebrada Macul that people have been using for years will be closed [privatized]’. ‘I had no idea about this’ [he told me]”.(Darío, 72 years old, parr. 23)

“We met social leaders because an ecological activist came to the Community Union –a social organization of neighbors- to ask for help to recover the Quebrada Macul. I had some beautiful photos of the place, so he asked me to please come with him to the meeting. [...] We spent a long time at the fairs sharing this [information], so people would realize that they had to fight for the hill. [...] After our victory, our leader talked to the owner, and other processes started from there".(Javiera, 65 years old, parr. 84)

“We liked to come [to the hill] at night, and spend the night, have a barbecue and then come down the next day. But if we entered there [the official entrance of the park after 2005] they would not let us; so, we entered the hill through unofficial routes. One day a park ranger told us: ‘hey guys, you have to go to the official entrance to register yourselves’ [...]: a friend went down to register and that was the first sign that the park was been protected. For us, [and] I think [for] many people in Peñalolén, we started [...] changing the concept”.(Miguel, 36 years old, parr. 70)

“It was super complicated to work with them, because of the bonfires, the people camping [in] the Guayacán sector, when we went patrolling rounds, it was easy to find 20, 30 tents, neighbors camping for a month, two months, camping the whole season. It was a hard but fun work, some people were very welcoming, whereas others less so”.(Miguel, 36 years old, parr. 22)

“[And what the building of the University provoked among neighbors?] Rejection, yes, like the association with the destruction of the hill, like how ugly it looks there. I think the same thing happened when we saw the first gates up here because we are [were] so used to going to the hill without anybody telling us anything".(Miguel, 36 years old, parr. 278-280)

3.2. There is no unity without memory: from struggle to oblivion

“[The Quebrada Macul] is everything for the people of Peñalolén. I believe that if tomorrow the hill disappears, it will not be Peñalolén. The first thing you do in the morning after it rains, you go out and see if [the hill] is snowed or not, or if it is going to rain because the sky is closing, [and] the hill is closing. It tells us what's going to happen... It's everything! It gives us the day, it gives us the time, it gives us everything”.(Javiera, 65 years old, parr. 211)

“We, as [people from] Peñalolén, are used to leaving the house and looking at the hill, it is something that is above us. [...] There are many people from Peñalolén who do not know the park either, they may have grown old and never visited the Quebrada Macul. But they like the hill!”.(Miguel, 36 years old, parr. 82)

“It is the only thing for the complete community, the Peñalolino -people from Peñalolén- without its creek stops being Peñalolino, and many people was saying ‘how can they not let me enter?’. I tell you I am 65 years old, when I was 50, 48 years old, I was like my son when I started to fight for the Quebrada Macul. And there were people who were 70 years old and said ‘mijita, you have to fight for that’, so I said, ‘why am I going to fight for it?’. And people said ‘[because] we went picking blackberries in the fields, up there by the hill’, and all the people had something to do with the place, some practice related".(Javiera, 65 years old, parr. 237)

“[What does all this place mean to you?] My life itself. And every day it hurts that every day you see more and more damage. So really, if I could not let anyone in here and take care of this like gold, it would be... Because it really is a very beautiful part and it is being damaged all the time and ending up being the responsibility of the people who sometimes come here, which is not all of them, and most of them are more harmful”.(José, 79 years old, parr. 356-360)

“During the dictatorship, they wouldn't even let us talk to the neighbor across the street. We had a very bad time, we had a very bad time [...]. Although it is also very important because thanks to this we started to get together, we started to spread the word, because we could not continue with the situation that we were in”.

“Look, the Quebrada Macul is like the reverse of the Villa Grimaldi [...]. The Villa Grimaldi is pain, death, and the Quebrada Macul is recreation, relaxation, enjoyment, being out in the fresh air. It is the opposite”.(Bernardita, 72 years old, parr. 69 / 192-194)

“[Does your daughter go to the park Quebrada Macul?] No, no. She has no idea. ‘It's pretty and everything -she tells me-, you may like it mom, but I'm not going because I'm not interested in it'. So, I see those attitudes. I see it in my own people”.(Javiera, 65 years old, parr. 155)

“We have been losing the memory, I don't know how to explain it, sensations related to the park seem lost, for the same reason that I explained before: generational changes”.

“I believe that with all the [recent] massification, they have been losing the local communities in this role of identity of the park”.(Miguel, 36 years old, parr. 158 / 178)

“[What key agents do you think have been important to the history of the creek?] The park rangers".(Hernán, 32 years old, parr. 218)

3.3. More contemporary forms of unity in the park: public usages today

“So, and we, at least when I go there, I share with the kids, "kids, if you are going to get into the waterfall, focus your mind. Be thankful you're here, be thankful you're underwater," and that's how we do it. We go underwater and we always ask for something from nature, to give us focus, to give us energy to be able to rethink ideas as I said, to be able to make decisions correctly and not in a crazy way. To get here from the city and they can have a clearer vision of what they need to do. In other words, if they have the shit or the muddy in certain things, everything has a solution. Or if they're sad or something, life goes on; They have to keep fighting.”

“On a psychological level, yes, it's an escape. So, if [the hill] is not there, I think it would have a significant psychological impact on people. There's no hill, there's no water”.(parr. 246 / 397)

"[And they suddenly meet right there on the hill?] Sure, 'and –they ask- when do we go up again?' 'When we can!' [he replies]. So you create a WhatsApp group, it's all different nowadays. And we're already on our way!"(Hernán, 32 years old, parr. 392-393).

“I would like them [authorities] to add the specific branch of environmental education to the curriculum in schools. I think this is a struggle for all environmental educators, a permanent struggle [...]. It is very shocking that they [still] talk about the polar bear or that they talk about the giraffe, the rhinoceros, whereas in Chile we have a good [different] fauna. In schools, I think that this is the important change for the new generations”.(Miguel, 36 years old, parr. 248)

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

6. Patents

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Logan, John. Making a Place for Space: Spatial Thinking in Social Science. Annual review of sociology. 2012, 38. [CrossRef]

- Maloutas, T. , & Karadimitriou, N. (2022). Chapter 1: Introduction to Vertical Cities: urban micro-segregation, housing markets and social reproduction. In Vertical Cities. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar Publishing. [CrossRef]

- Pfirsch, T. Controlling the Proximity of the Poor: Patterns of Micro-Segregation in Naples’ Upper-Class Areas. Land. 2023, 12, 2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calderón-Figueroa, F. (2024). Residential Micro-Segregation and Social Capital in Lima, Peru. Land 13. [CrossRef]

- 5. Vámos R, Nagy G, Kovács Z. (2023). The Construction of the Visible and Invisible Boundaries of Microsegregation: A Case Study from Szeged, Hungary. Land 12,. [CrossRef]

- Dixon, J. Contact and boundaries: ‘Locating’ the social psychology of intergroup relations. Theory & Psychology 2001, 11, 587–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabatini, Francisco, Cáceres, Gonzalo, & Cerda, Jorge. Segregación residencial en las principales ciudades chilenas: Tendencias de las tres últimas décadas y posibles cursos de acción. EURE (Santiago) 2001, 27, 21–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garretón, M.; Basauri, A. & Valenzuela, L. (2020). Exploring the correlation between city size and residential segregation: comparing Chilean cities with spatially unbiased indexes. Environment & Urbanization, 32 (2): 569-588. [CrossRef]

- Fuentes, L.; Truffello, R. & Flores, M. Impact of land use diversity on daytime social segregation patterns in Santiago de Chile. Buildings 2022, 12, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Tagle, J. & López M, E.. El estudio de la segregación residencial en Santiago de Chile: revisión crítica de algunos problemas metodológicos y conceptuales. EURE (Santiago) 2014, 40, 25–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Tagle, J. & Romano, S. (2019). Mezcla social e integración urbana: Aproximaciones teóricas y discusión del caso chileno. Revista INVI, 34.

- Álvarez Rojas, A. M. (2008). La segmentación económica del espacio: la comunidad ecológica y la toma de Peñalolén. Revista Eure, XXXIV (101): 121.136.

- Mardones Arévalo, R. ¡No en mi patio trasero! El caso de la comunidad ecológica de Peñalolén. Íconos: Revista de Ciencias Sociales, 2009; 34, 139–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musset, A. , & Peixoto Faria, T. de J. (2016). Justicia, conflictos socio-espaciales, resistencia. Rescate histórico y construcción de las identidades en las ciudades latinoamericanas. Revista Geografares, julio – diciembre. ISSN 2175-3709.

- Bettencourt, Leonor; Dixon, John & Castro, Paula Understanding how and why spatial segregation endures: A systematic review of recent research on intergroup relations at a micro-ecological scale. Social Psychological Bulletin 2019, 14, E33482.

- Dixon, J. , Tredoux, C. , Davies, G., Huck, J., Hocking, B., Sturgeon, B., Whyatt, D., Jarman, N., & Bryan, D. Parallel lives: Intergroup contact, threat and the segregation of everyday activity spaces. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 2019, 118, 457–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKeown, S. , & Dixon, J. The ‘contact hypothesis’: Critical reflections and future directions. Social and Personality Psychology Compass 2017, 11, [e12295]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixon, J. , Sturgeon, B., Huck, J., Hocking, B., Jarman, N., Bryan, D., Whyatt, D., Davies, G., & Tredoux, C. (2022). Navigating the divided city: Place identity and the time-geography of segregation. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 84. Doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2022. [CrossRef]

- Altman, L. , & Low, S. (1992). Place attachment: A conceptual inquiry. In I. Altman, & S. M. Low (Eds.), Place Attachment (pp. 1–12). New York: Plenum Press.

- Altman, L. , & Rogoff, B. (1987). World views in psychology: Trait, interactional, organismic, and transactional perspectives. In D. Stokols & I. Altman (Eds.), Handbook of environmental psychology (Vol. 1, pp. 1–40). Wiley.

- Gifford, R. , Steg, L., & Reser, J. P. (2011). Environmental psychology. In P. Martin, F. M. Cheung, M. C. Knowles, M. Kyrios, L. Littlefield, J.B Overmier, & J.M. Prieto (Eds.), The IAAP handbook of applied psychology (pp. 440-470). Blackwell.

- Winkel, G. , Saegert, S., & Evans, G. W. An ecological perspective on theory, methods, and analysis in environmental psychology: Advances and challenges. Journal of Environmental Psychology 2009, 29, 318–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hay, R. Sense of place in developmental context. Journal of Environmental Psychology 1998, 18, 5–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández, B. , Martín, A. M., Ruiz, C., & Hidalgo, M. C. The role of place identity and place attachment in breaking environmental protection laws. Journal of Environmental Psychology 2010, 30, 281–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proshansky, H. M. The city and self-identity. Environment and Behavior 1978, 10, 147–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proshansky, H. M. , Fabian, A. , & Kaminoff, R. Place-identity: physical world socialisation of the self. Journal of Environmental Psychology. 1983, 3, 57–83. [Google Scholar]

- Fullilove, M. Psychiatric implications of displacement: contributions from the psychology of place. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1996, 153, 1516–1523. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Giuliani, M. V. (2003) Theory of attachment and place attachment. In M. Bonnes, T. Lee, & M. Bonaiuto (Eds.), Psychological Theories for Environmental Issues (pp. 137–170). Aldershot: Ashgate.

- Vidal, T. , Valera, S. , & Peró, M. Place attachment, place identity and residential mobility in undergraduate students. PsyEcology, 2010, 1, 353–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Speller, G. , Lyons, E. & Twigger-Ross, C. L. A community in transition: The relationship between spatial change and identity processes. Social Psychological Review. 2002, 4, 39–58. [Google Scholar]

- Valera, S A study of the relationship between symbolic urban space and social identity processes. International Journal of Social Psychology 1997, 12, 17–30. [CrossRef]

- Vidal, T. , & Pol, E. La apropiación del espacio: una propuesta teórica para comprender la vinculación entre las personas y los lugares. Anuario de Psicología 2005, 36, 281–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scannell, L. , & Gifford, R. The experienced psychological benefits of place attachment. Journal of Environmental Psychology 2017, 51, 256–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowles, G. D. Place attachment among small town elderly. Journal of Rural Community Psychology 1990, 11, 103–120. [Google Scholar]

- Rollero, C. , & Piccoli, N. D. Does place attachment affect social well-being? European Review of Applied Psychology 2010, 60, 233–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewicka, M. Place attachment, place identity, and place memory: Restoring the forgotten city past. Journal of Environmental Psychology 2008, 28, 209–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, B. , Perkins, D. , Brown, G. Place Attachment in a Revitalizing Neighborhood: Individual and Block Levels of Analysis. Journal of Environmental Psychology 2003, 23, 259–71. [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen-Pincus, M. , Hall, T. , Force, J. E., & Wulfhorst, J. D. Sociodemographic effects on place bonding. Journal of Environmental Psychology 2010, 30, 443–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comstock, N. , Dickinson, L. M., Marshall, J. A., Soobader, M. J., Turbin, M. S., Buchenau, M., & Litt, J. S. Neighborhood attachment and its correlates: Exploring neighborhood conditions, collective efficacy, and gardening. Journal of Environmental Psychology 2010, 30, 435–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gifford, R. Environmental Psychology Matters. Annual Review of Psychology 2014, 65, 541–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beck, H. Linking the quality of public spaces to quality of life. Journal of Place Management and Development 2009, 2, 240–248, Kearns and Livingston (2012). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, N. , Kearns, A., & Livingston, M. (2012). Place attachment in deprived neighbourhoods: The impacts of population turnover and social mix. Housing Studies, 27, 208-231. [CrossRef]

- Livingston, M. , Bailey, N., & Kearns, A. (2010). Neighbourhood attachment in deprived areas: Evidence from the north of England. Journal of Housing and the Built Environment, 25, 409–427. [CrossRef]

- Di Masso, A. , Vidal, T. , & Pol, E. La construcción desplazada de los vínculos persona lugar: una revisión teórica. Anuario de Psicología 2008, 39, 371–385. [Google Scholar]

- Manzo, L. For better or worse: Exploring multiple dimensions of place meaning. Journal of Environmental Psychology 2005, 25, 67–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto de Carvalho, L. , & Cornejo, M. (2018). Por una aproximación crítica al apego al lugar: Una revisión en contextos de vulneración del derecho a una vivienda adecuada. Athenea Digital, 18, 1-39. [CrossRef]

- Nightingale, C. H. (2012). Segregation: A global history of divided cities. University of Chicago Press.

- Toolis, E. E. (2017). Theorizing Critical Placemaking as a Tool for Reclaiming Public Space. American Journal of Community Psychology, 2017, 59, 184–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Masso, A. & Dixon, J. More than words: Place, discourse and the struggle over public space in Barcelona. Qualitative Research in Psychology 2015, 12, 45–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Masso, A. Grounding citizenship: Toward a political psychology of public space. Political Psychology 2012, 33, 123–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devine-Wright, P. Rethinking NIMBYism: The role of place attachment and place identity in explaining place-protective action. Journal of Community & Applied Social Psychology, 2009, 19, 426–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 52. Cresswell, Tim (204). Place. A short introduction.

- Gieryn, T. F. A space for place in sociology. Annual Review of Sociology 2000, 26, 463–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayen Huerta, C. Rethinking the distribution of urban green spaces in Mexico City: Lessons from the COVID-19 outbreak. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening 2022, 70, 127525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kephart, L. How racial residential segregation structures access and exposure to greenness and green space: A review. Environmental Justice 2022, 15, 204–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saporito, S. , & Casey, D. Are there relationships among racial segregation, economic isolation, and proximity to green space? Human Ecology Review, 2015, 21, 113–132, http://www.jstor.org/stable/24875135. [Google Scholar]

- Sister, C. , Wolch, J. , & Wilson, J. Got green? Addressing environmental justice in park provision. GeoJournal, 2009, 75, 229–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazrafshan, M. , Tabrizi, A. M., Bauer, N., & Kienast, F. Place attachment through interaction with urban parks: A cross-cultural study. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening, 2021, 61, 127103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callaghan, A. , McCombe, G. , Harrold, A., McMeel, C., Mills, G., Moore-Cherry, N., & Cullen, W. The impact of green spaces on mental health in urban settings: a scoping review. Journal of Mental Health, 2020, 30, 179–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabbar, M. , Yusoff, M. M., & Shafie, A. Assessing the role of urban green spaces for human well-being: A systematic review. GeoJournal, 2022, 87, 4405–4423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyes-Riveros, R. , Altamirano, A. , De La Barrera, F., Rozas-Vásquez, D., Vieli, L., & Meli, P. Linking public urban green spaces and human well-being: A systematic review. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening, 2021, 61, 127105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agostini, C.; Hojman, D.; Román, A. & Valenzuela, L. Segregación residencial de ingresos en el Gran Santiago, 1992-2002: una estimación robusta. Revista Eure, 2016, 42, 159–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchant Santiago, C.; Sánchez Acuña, R. & Monje Hernández, Y. (2022). Long-term features of cities in Latin America and the Caribbeans. In: J. M. González; C. Irarrázaval & R. C. Lois-González (Eds.). The Routledge Hanbook of urban studies in Latin America and the Caribbeans. Cities, urban processes, and policies.

- De Mattos, C.; Fuentes, L. & Link, F. Tendencias recientes del crecimiento metropolitano en Santiago de Chile: ¿Hacia una nueva geografía urbana? INVI 2014, 29, 193–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krellenberg, K.; Höfer, R. & Welz, J. Dinámicas recientes y relaciones entre las estructuras urbanas y socioeconómicas en Santiago de Chile: el caso de Peñalolén. Revista de Geografía Norte Grande, 2011, 48, 107–131. [Google Scholar]

- Vásquez, A. & Salgado, M. Desigualdades socioeconómicas y distribución inequitativa de los riesgos ambientales en las comunas de Peñalolén y San Pedro de la Paz. Una perspectiva de justicia ambiental. Revista de Geografía Norte Grande, 2009, 43, 95–110. [Google Scholar]

- Salgado, M. Desigualdades urbanas en Peñalolén (Chile). La mirada de los niños. Bulletin de l’Institut Francais d’Études Andines, 2013, 42, 525–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beyá Marshall, R. (2019). Prácticas de apropiación y significados atribuidos al paisaje fluvial en riesgo y su incidencia en la vulnerabilidad ante desastres socio-naturales. Caso de estudio: el Parque Natural Quebrada de Macul. [Tesis para obtener el grado académico de Magíster en Asentamientos Humanos y Medio Ambiente, Instituto de Estudios Urbanos y Territoriales, Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile]. https://estudiosurbanos.uc.cl/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/TESIS-RBM.pdf.

- Goertz, G. (2012). Case studies, causal mechanisms, and selecting cases. Kroc Institute for International Peace Studies, University of Notre Dame, pp. 1–25.

- Treharne, G. , & Riggs, D. (2015). Ensuring Quality in Qualitative Research. In, P. Rohleder & A. Lyons (Eds.). Qualitative Research in Clinical and Health Psychology (pp. 57-73). Red Globe Press.

- Burawoy, M. (2009). The extended case method. Four countries, four decades, four great transformations, and one theoretical tradition. University of California Press.

- Patton, M. Q. (2002). Qualitative research & evaluation methods. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Hernández Sampieri, R.; Fernández Collado, C. & Baptista Lucio, P. (2014). Muestreo en la investigación cualitativa. En: Hernández Sampieri, R.; Fernández Collado, C. & Baptista Lucio, P. (Eds.). Metodología de la investigación. Capítulo 13, pp. 382–393, 6ta Edición. McGraw Hill / Interamericana Editores.

- Kawulich, B. La observación participante como método de recolección de datos. Qualitative Social Research [On-line Journal] 2005, 6. Art. 43. http://nbn-resolvingde/urn:nbn:de:0114-fqs0502430. [Google Scholar]

- Guest, G.; MacQueen, K. M. & Namey, E. E. (2012). Applied Thematic Analysis. SAGE Publications. USA: Washington DC.

- Braun, V. & Clarke. V. Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercice and Health 2019, 11, 589–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lussault, M. (2015). El hombre espacial. La construcción social del espacio humano. Amorrortu Editores. Buenos Aires, Argentina.

- Fernández, I. C. , De la Barrera, F., Figueroa, J., & Lazzoni, I. (2018). Biodiversidad urbana, servicios ecosistémicos y planificación ecológica: un enfoque desde la ecología del paisaje. Biodiversidad Urbana en Chile: Estado del arte y los desafíos futuros, U: Santiago.

- Pinto de Carvalho, L.; Berroeta, H.; Silva Peñaloza, E. & Tironi Rodó, E. Entramando cuerpos, hogares y territorios: exploraciones sobre el deshacer hogar de mujeres chaiteninas. Revista INVI, First edition. Santiago: Universidad Central de Chile, 113-146. [CrossRef]

- Angelcos, N.; Campos, L. ; Ropert, T & Sharim, D. (2020). De protagonistas a denegados: el doble trauma en un caso de relocalización post-incendio en Valparaíso, Chile. Scripta Nova, XXIV (636). [CrossRef]

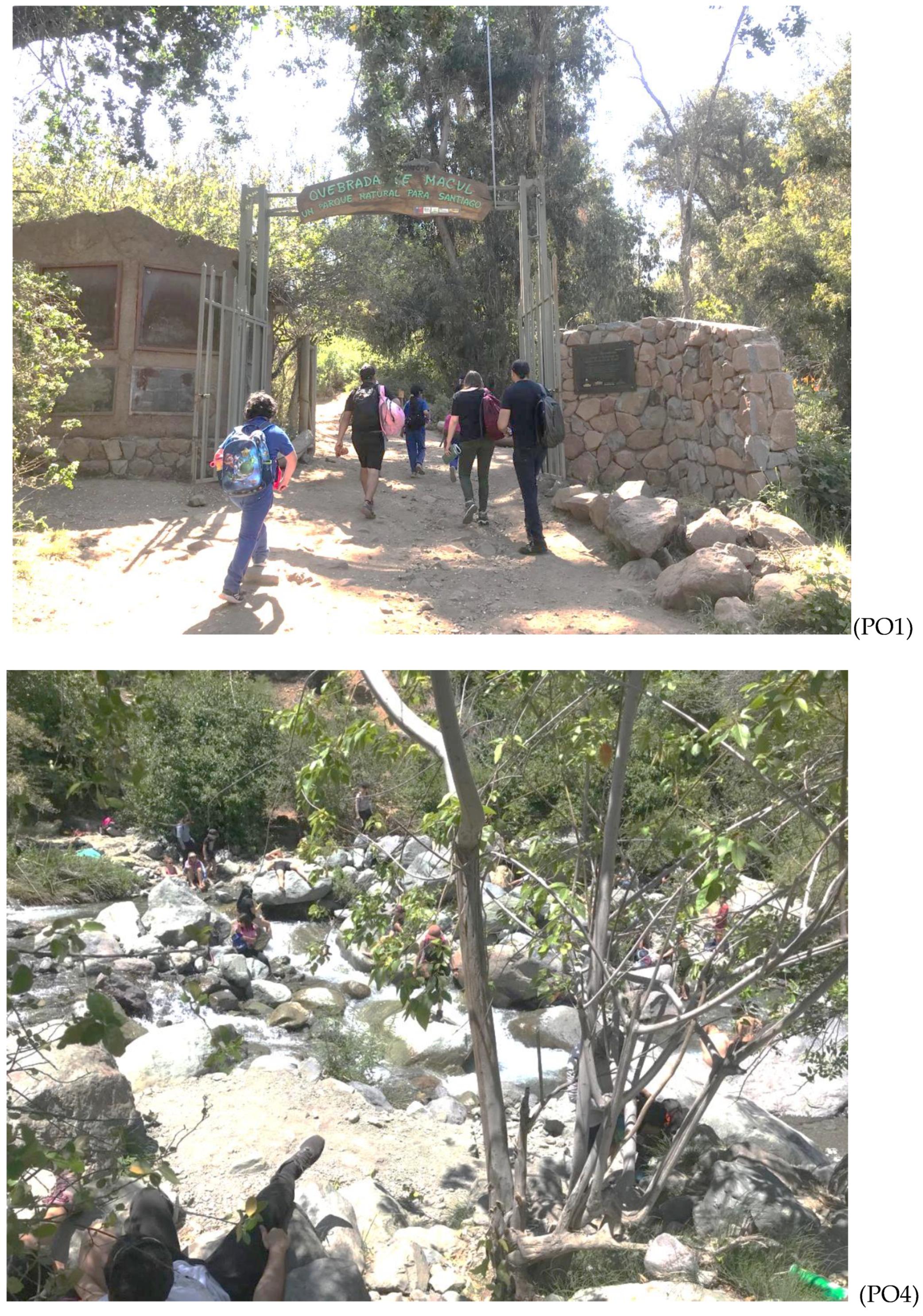

| 1 | Photographs were taken carefully attending confidentiality, not showing any identifiable face except researchers in the field – see Photograph 1. |

| 2 | N Sampling corresponds to people directly interviewed by the research team, whereas N Extended represents an approximation of people observed in the place, considering counting each group. For big groups, we considered an average of 30 people or more. |

| 3 | PO meaning Participant Observation a indicated in Table 1 (page 6) and the parragraph’s number were data was coded. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).