1. Introduction

In recent decades, informal urbanization has become one of the clearest expressions of the structural inability of the state to ensure effective land management and inclusive housing policy. In Portugal, Informally Originated Urban Areas (AUGI) reflect this institutional fragility because they emerged from unregulated land subdivision operations, frequently carried out without proper planning permissions, and have proliferated especially on the outskirts of metropolitan areas under demographic pressure, housing shortages, and weak urban oversight.

This phenomenon cannot be fully understood as merely a legal anomaly. It must be seen as a systemic response to structural housing deficits, particularly from the 1960s to the 1980s. During this period, thousands of households resorted to informal solutions as a way to access affordable housing near employment centers, in the absence of effective public housing policy or affordable private supply (Gonçalves et al., 2010). The growth of these settlements was further enabled by the permissive or ambiguous role of local authorities, who tolerated or indirectly supported self-built urbanization due to limited enforcement tools or political considerations.

It is also important to emphasize that these AUGIs do not refer to places of precarious housing built with temporary materials, but rather to well-established residential structures aimed at a middle class with some economic capacity that could not find suitable housing solutions on the market. To address this widespread phenomenon, the Portuguese legislator introduced an exceptional and transitional legal framework in 1995 (Law No. 91/95 of September 2nd). This law aimed to enable the urban regularization of AUGI’s through formal planning instruments such as allotment operations and detailed plans. Originally conceived as a temporary solution to a historically specific urban problem, the law was successively amended and progressively absorbed into the broader territorial planning regime, culminating in its consolidation as Law No. 70/2015 of July 16th.

This revised legislation introduced procedural innovations and expanded the responsibilities of municipalities, including deadlines for the creation of joint administrative commissions and for issuing regularization titles. However, it also introduced a rigid legal architecture, built around narrowly defined eligibility criteria, cumulative procedural requirements, and highly specific implementation.

As a result, many areas, despite being socially consolidated and physically integrated into the urban fabric, have remained outside the scope of legal regularization due to technical constraints, legal ambiguities, environmental limitations, or social vulnerability.

Among the most affected are those territories defined under Article 48 of Law No. 70/2015 as “insusceptible of regularization”, often due to environmental protection regimes, exposure to natural hazards, or conflict with infrastructure easements. As Alves (2008) highlights, the legal classification of these areas results not only in exclusion from planning tools, but also in the absence of any clear compensatory mechanism, leaving residents in a prolonged state of legal and spatial limbo.

It is within this evolving legal and urban landscape that we propose the concept of “double marginality”. This term captures the condition of AUGI that, in addition to having originated outside formal urban planning processes, are now legally invisible under current norms. These are cases that either do not fulfil the formal conditions set out in Article 1 of Law No. 70/2015 (such as land classification or licensing timeline), or that fail to meet operational conditions (e.g., lack of formal administration, unresolved land tenure, or spatial insusceptibility). These doubly informal areas thus embody a form of legal liminality, where decades of de facto urban life coexist with a persistent absence of legal recognition. This condition was repeated in many Municipal Master Plans (PDMs), where the classification of insusceptible of regularization had a significant impact.

Against this backdrop, the main objective of this article is to develop a typology of exceptional cases within the AUGI regularization framework, specifically those that illustrate conditions of “double marginality”, where historical informality is compounded by contemporary legal exclusion. These are not isolated anomalies, but structurally embedded situations that expose the limits of the current legal regime and challenge the prevailing models of urban governance.

To achieve this, the article adopts a multi-method approach that combines:

Documentary and legal analysis of national and municipal frameworks (including Law No. 70/2015 and relevant planning instruments);

Empirical case studies of selected AUGI in the Lisbon Metropolitan Area (LMA), representing a range of social, legal, and environmental conditions;

And spatial analysis and mapping, which visualizes the overlapping vulnerabilities and legal constraints affecting these areas.

The proposed typology is organized along three structuring dimensions: social-demographic; legal-political; environmental-risk factors, and is informed by real-world examples of areas that remain legally unresolved despite long-term urban consolidation.

By articulating the systemic obstacles that prevent these territories from achieving legal recognition, this article addresses an existing lacuna in the literature and in public policy by bridging legal analysis and empirical typology, offering a grounded framework for classifying and understanding these exceptional situations. This framework not only enhances our understanding of informal urbanization in Portugal but also provides actionable insights for policymakers. Ultimately, the article advances policy and legal recommendations aimed at constructing a more inclusive and context-sensitive framework for the regularization of informal urban areas, ensuring that future interventions are both equitable and aligned with the lived realities of these territories.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Informal Urbanization and Portuguese Context

The phenomenon of informal urbanization has been widely studied across disciplines, particularly in contexts where rapid urban growth outpaces institutional capacity. Internationally, scholars have explored informal settlements in Latin America, South Asia, and Sub-Saharan Africa, emphasizing the intersections between land tenure insecurity, social inequality, and weak urban governance (Roy, 2005; Fernandes, 2002; UN-Habitat, 2020). In European contexts, informal urban development has received comparatively less attention, yet southern countries like Spain, Italy, Greece and Portugal exhibit long-standing traditions of informal land occupation and housing self-production (Pruijt, 2003; Allen et al., 2014; Calor and Alterman, 2017). The problem has never been fully addressed, leading to ongoing challenges in urban planning and service provision. Informal settlements often lack essential infrastructure, exacerbating social inequalities and limiting residents’ quality of life. Addressing these issues requires a multifaceted approach that includes enhancing municipal capacities, improving legal frameworks, and fostering community participation in urban planning processes.

Ultimately, fostering community participation is crucial for developing inclusive urban planning strategies that can effectively address the complexities of informal settlements and enhance residents’ living conditions. This approach not only empowers residents but also promotes self-organization, which is vital for the incremental transformation of informal settlements into more sustainable living environments. This transformation often hinges on the recognition of residents’ rights and the integration of their knowledge in shaping urban policies that reflect their needs and aspirations.

In Portugal, AUGI represent a specific form of informal urbanization characterized by legally unrecognized land subdivision and construction. These areas are often the result of land speculation, lack of public housing alternatives, and permissive attitudes from local authorities, particularly during the urban expansion of the 1960s-1980s. While the enactment of Law No. 91/95 and its subsequent amendments, culminating in Law No. 70/2015, provided a legal framework for urban regularization, numerous limitations remain in practice. These limitations include bureaucratic inefficiencies, lack of political will, and inadequate resources to implement regularization processes effectively, which continue to hinder meaningful progress in addressing informal urbanization challenges in Portugal (Raposo and Valente, 2010; Pereira and Ramalhete, 2017).

Despite these challenges, ongoing efforts to refine legal frameworks and enhance governance mechanisms may facilitate the gradual formalization of AUGIs, ultimately improving urban integration and living conditions for affected residents. Enhancing local governance capacity and fostering community engagement are essential steps towards addressing the complexities of informal urbanization in Portugal and ensuring sustainable urban development. This necessitates a collaborative approach that bridges the gap between formal regulations and the realities faced by residents, ensuring that their voices are integral to the planning process (Chamusca, 2024).

2.2. Informality as a Historical and Structural Condition

In the Portuguese context, urban informality has been historically linked not to illegality in the criminal sense, but to systemic governance failure, a condition that emerged at the intersection of state inaction, market exclusion, and popular strategies for accessing housing. Studies on the genesis of AUGI in Lisbon region have shown that the expansion of informal settlements was not merely tolerated but often implicitly supported by local authorities who lacked technical or political resources to oppose them (Gonçalves and al., 2010). These settlements provided functional housing solutions at a time when public housing supply was insufficient, and the private market was inaccessible to most working-class families. Informality, in this context, became a normalized mode of urban production, shaping the periphery of Lisbon and other metropolitan areas. There were attempts to counter this process, notably with the approval of Decree-Law No. 46673 of 1965 and later Decree-Law No. 289/73, which sought to regulate urban land subdivision and speed up licensing. However, the lack of technical capacity of local authorities and delays in administrative procedures severely limited their effectiveness. These laws sought to curb illegal urban development, but in practice they did little to halt a process that was already deeply entrenched.

Recent studies point to significant inconsistencies in how municipalities interpret and apply the legal provisions for AUGI, leading to highly unequal outcomes (Condessa et al., 2020; Gonçalves et al., 2018). Additionally, some authors have noted that the legal model depends heavily on resident initiative and collective administration, a model that excludes vulnerable populations, particularly the elderly, low-income households, or those lacking legal ownership documentation (Tulumello & Alegre, 2016). Furthermore, environmental constraints and public land protections often place these areas in a legal limbo, impeding any progress toward formalization.

This legal ambiguity underscores the urgent need for comprehensive policy reforms that prioritize inclusivity and equitable access to housing for all residents. Such reforms should focus on enhancing transparency and participation in the governance processes, ensuring that all community members, particularly marginalized groups, have a voice in shaping their urban environments (Chamusca, 2024). This inclusive approach not only addresses the immediate needs of vulnerable populations but also fosters resilience within communities, ultimately contributing to a more sustainable urban future. This necessitates a re-evaluation of existing policies to align them with the principles of multilevel governance, ensuring that diverse community voices are heard and integrated into urban planning processes (UN-Habitat, 2023; Morrison and Hibbard, 2024; Global Alliance Against Hunger and Poverty, 2023).

Despite these challenges, few academic works have proposed a structured typology of the “exceptional cases”, those AUGI that remain outside the reach of the legal framework despite efforts to normalize them. The concept of “double marginality”, explored in recent exploratory work (Gonçalves et al., 2018), addresses this gap by combining historical informality with present-day legal and procedural exclusion. However, this concept has yet to be fully systematized and operationalized in the context of Portuguese urban planning law. This gap in the literature highlights the need for further research to develop a comprehensive typology that can inform policy interventions and promote effective governance in addressing informal urbanization in Portugal. This typology should consider the unique characteristics of each AUGI, emphasizing the need for localized solutions that address specific community contexts and challenges. Developing such a typology is essential for ensuring that policy measures are tailored to the diverse realities of informal settlements, facilitating more effective governance and integration of these areas into the urban fabric.

Despite the legal and urban relevance of AUGI in Portugal, academic research on the subject remains limited and often fragmented. Most existing studies are framed within urban planning or housing policy discourses, with few offering integrated legal and territorial analyses. Some authors have focused on the historical origins of informal settlements and the evolution of urban sprawl in Lisbon’s metropolitan periphery (e.g., Ferreira, 2001; Antunes, 2010), while others have explored the procedural and governance challenges faced by municipalities in applying Law No. 91/95 and its successors (Gonçalves et al., 2018). However, there is still a lack of typological approaches that account for cases of persistent exclusion, especially those that fall outside the regularization path due to non-compliance with cumulative legal conditions.

Urban informality is not only a planning issue but also a question of urban citizenship, the recognition of inhabitants as legitimate subjects of rights within the city. As Lefebvre (1968) and later Harvey (2008) emphasized, the right to the city includes access to infrastructure, participation in urban governance, and security of tenure. In the Portuguese context, doubly informal AUGI highlight the tension between formal legal frameworks and lived urban realities, where residents often experience long-term integration into city life while remaining legally excluded. This condition creates what Holston (2009) terms “insurgent citizenship”, a demand for recognition beyond property-based rights, particularly among marginalized populations. The persistence of legal invisibility, even in spatially consolidated settlements, reveals the inadequacy of a strictly normative and procedural approach to urban regularization.

The decentralization of urban policy implementation in Portugal has accentuated territorial inequalities. While Law No. 70/2015 assumes a homogeneous capacity across municipalities to lead reconversion processes, the reality is that institutional, technical, and financial disparities significantly influence outcomes. Smaller municipalities or those with weaker planning departments struggle to meet the administrative and procedural requirements imposed by law. Moreover, political priorities and interpretations vary, creating uneven treatment for similar AUGI across municipal borders. This disparity reinforces a “postcode injustice”, whereby access to legal recognition is shaped not by residents’ actions, but by the institutional characteristics of the municipality in which their AUGI is located (Condessa et al., 2020). Such conditions challenge the principle of territorial cohesion embedded in Portuguese planning law and underscore the need for coordinated equity-driven responses at the national level.

2.3. Legal Framework and Territorial Justice in Portugal

In the context of urban informality, public policies play a central role not only in enabling regularization but also in producing or perpetuating spatial inequalities. Contemporary urban theory, drawing from aforementioned Lefebvre’s concept of the right to the city, argues that access to urban space should be considered a collective right that transcends market logic and property-based entitlement (Lefebvre, 1968; Harvey, 2008). This principle intersects with the notion of territorial justice, which calls for an equitable distribution of urban resources, infrastructure, and opportunities across different geographic and socio-economic groups (Soja, 2010).

In Portugal, although the creation of the AUGI regime under Law No. 91/1995 was an innovative step towards the recognition and integration of informal settlements, it also incorporated a logic of self-responsibility. Residents were expected to organize into administrative commissions, bear the financial costs of regularization, and navigate complex bureaucratic and technical processes. This model, carried forward in Law No. 70/2015, places a heavy burden on residents, disproportionately affecting older populations, low-income households, and those with limited legal or technical knowledge, thereby exacerbating spatial and social inequalities.

A critical reading of Law No. 70/2015 reveals both its scope and limitations in terms of promoting territorial justice and fulfilling the right to the city:

Article 1.º (Object and Scope) defines AUGI narrowly as areas parcelled without a license prior to December 1984, and only if classified as urban or urban expansion land in municipal land-use plans. This legal framing excludes more recent informal settlements or those outside designated zones, despite their socio-urban relevance.

Article 3 (Duty to Regularise) places responsibility for reconversion directly on owners and occupants, including the financial burden of infrastructure and legal procedures. This can be particularly punitive or at least limiting for residents who acquired properties without being fully aware of their informal status or who lack the means to participate effectively (not forgetting that these owners should not be favoured over others who have always acted within the law). Criticism of this situation is very delicate, as it raises the question of benefiting the offender and/or rewarding the offence.

Article 5.º provides a mechanism for regularizing areas only partially classified as urban/urban expansion, but under strict cumulative conditions. This provision has been interpreted restrictively by some municipalities, limiting its applicability and reinforcing legal fragmentation between territories.

Article 46.º introduces a discretionary mechanism through which municipalities may exceptionally authorize the maintenance of constructions that fail to meet legal criteria. However, it requires municipal regulation and political will, which are often lacking or uneven across regions.

Article 48.º addresses areas that cannot be regularised, where buildings may have to be demolished and residents rehoused. Although this article describes a process of social survey and rehousing (e.g., through social housing mechanisms), it implies the withdrawal, supported by legal justifications linked mainly to environmental issues but not only, of the urban rights of entire communities, contrary to the principles of inclusion and the right to remain.

Article 56.º-A mandates municipalities to report reconversion processes to the central administration. However, this focuses on data collection rather than support or intervention, illustrating the state’s monitoring but not redistributive role in addressing spatial injustice.

These legal mechanisms, though designed to manage urban irregularities, fail to account for the structural conditions that gave rise to informal development, and often treat residents as obstacles rather than stakeholders in urban governance. Furthermore, the heavy reliance on local governments, with uneven technical and financial capacities, creates significant disparities in implementation.

The Portuguese planning system has long relied on exception-based legal instruments to address complex or politically sensitive urban issues. As Dulce Lopes (2020) argues, this has led to the “normalization of the exceptional,” whereby transitory regimes, such as those regulating AUGI, become permanent fixtures in urban governance, rather than catalysts for systemic reform. Instead of establishing clear and inclusive legal norms, the planning system often resorts to temporary frameworks that manage informality without resolving its root causes. This creates zones of suspended legality, where territorial rights and obligations remain unclear, reinforcing legal uncertainty and spatial inequality. Such dynamics provide a critical backdrop to the concept of “double marginality” developed in this article, which seeks to unpack the long-term effects of legal exclusion on informal urban areas.

2.4. Legal Silence and Institutional Ambiguity

Building on this, several works has highlighted the ambiguities and omissions of the current legal framework, particularly regarding territories that fall outside formal eligibility for regularization. Alves (2008) points to the lack of procedural alternatives or compensation mechanisms for residents living in areas designated as “insusceptible of regularization” under Article 48 of Law No. 91/1995. These cases illustrate how legal exclusion operates not only through prohibition, but also through the absence of administrative action, a passive marginalization that sustains illegality over time. The literature on planning and informal settlements increasingly recognizes this form of legal inertia as a mechanism of structural inequality, where law’s silence effectively produces exclusion (Roy, 2005; Holston, 2008; Yiftachel, 2009; Caldeira, 2017).

While urban regularization is often treated as a technical planning issue, recent work has emphasized the need to integrate it with broader housing policy frameworks. A study focused on the municipalities of Loures and Odivelas demonstrates that the legal tools for AUGI regularization (Law No. 70/2015) and the public housing programs under the 1.º Direito framework, a national program launched in 2018 to support municipalities in addressing situations of severe housing deprivation through subsidized access to adequate housing, have evolved in parallel but largely disconnected ways. As a result, many families living in informal settlements find themselves ineligible for either program, excluded from reconversion due to environmental or procedural barriers, and simultaneously unable to access public housing subsidies due to land status or documentation gaps (Santos, 2024). The lack of coordination between land regularization and housing rights reinforces territorial inequality, and risks institutionalizing informality for communities that cannot meet rigid legal or technical criteria.

In this sense, the current regime struggles to align with the normative goals of urban justice, producing a legal geography in which the right to the city is unevenly distributed. Residents of certain AUGI benefit from proactive municipalities and cooperative neighbours, while others, often more precarious, face indefinite exclusion.

3. Methodology

This study adopts a mixed and interdisciplinary methodology, combining legal analysis, case study research and spatial cartography. The goal is to explore the institutional, legal, social, and environmental barriers that continue to exclude certain AUGI from the urban regularization framework, despite the existence of legal instruments.

a) Document Analysis

A critical legal and policy review was conducted, focusing on:

National legislation, particularly Law No. 91/95 and its consolidated version in Law No. 70/2015, as well as complementary frameworks such as the Legal Regime of Urbanization and Edification (RJUE) and RJIGT (Legal Framework for Territorial Management Instruments);

Municipal regulations, urban planning instruments, and minutes of local authorities in municipalities with high concentrations of AUGI, specifically, Odivelas, Loures, Sintra, Seixal, and Amadora (all belonging to the LMA);

The training and coordination strategy of the Directorate-General for the Territory (DGT) under Article 56-B of Law 70/2015, which was analyzed as an institutional response to legal fragmentation and uneven implementation at the local level.

This legal and documentary corpus provided the foundation for identifying gaps between legal frameworks and real-world application.

b) Case Studies

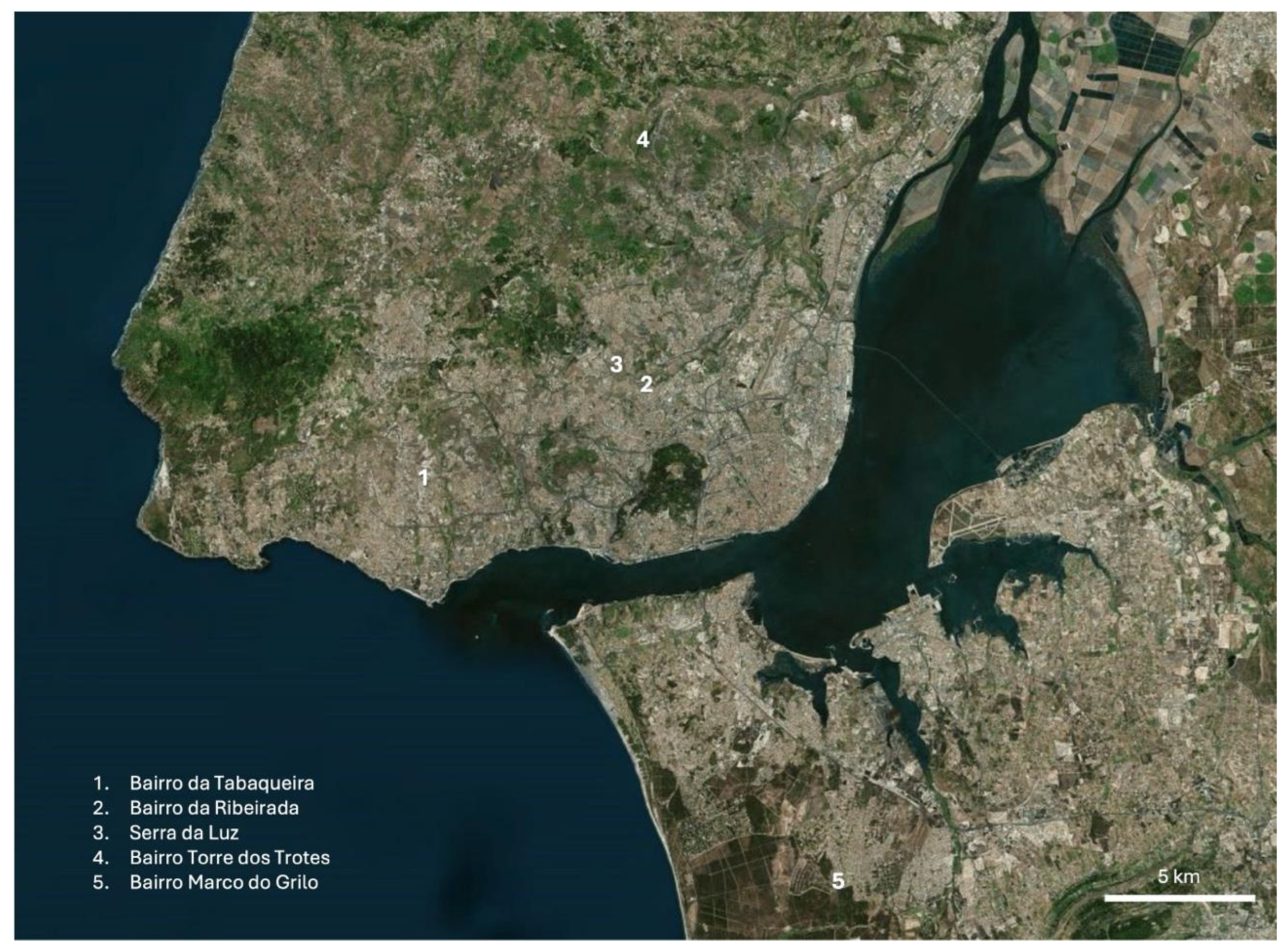

Five case studies were selected to represent diverse expressions of “double marginality”, areas that are both historically informal and currently excluded from regularization due to procedural, legal, or spatial constraints. The selected areas are:

Bairro da Serra da Luz (Odivelas)

Bairro da Ribeirada (Odivelas)

Bairro da Torre dos Trotes (Loures)

Bairro da Tabaqueira (Sintra)

Marco do Grilo (Seixal)

These areas were chosen using purposive sampling based on the following criteria:

Geographic and institutional diversity, reflecting different municipal strategies;

Degrees of risk, including geotechnical hazards, legal irregularities, and social vulnerability;

Presence or absence of formal governance structures, such as joint administrative commissions required by law.

Field visits and secondary data collection enabled detailed profiling of each site, considering both legal status and lived realities.

c) Spatial and Cartographic Analysis

To complement legal and qualitative insights, a spatial analysis was carried out using:

Data from the SIAUGI platform (AUGI Information System from DGT), which maps formally recognized AUGI across the national territory;

Satellite imagery and ortho-photos (via Google Earth and municipal GIS platforms), used to identify spatial characteristics, infrastructure deficits, and surrounding land use;

Mapping of AIRU (Areas Insusceptible to Urban Regularization) and their overlap with vulnerable populations, revealing territorial inequalities embedded in the legal framework.

This spatial dimension helped visualize patterns of exclusion and informed the typology proposed later in the article.

4. Results

Fieldwork and multidimensional analysis identified a persistent group of AUGIs excluded from the regularisation process. The five cases studied – Serra da Luz, Ribeirada, Torre dos Trotes, Tabaqueira and Marco do Grilo - reveal what this study refers to as ‘double marginality’, a condition characterized by both a historically irregular origin and a present-day legal and procedural exclusion (

Figure 1).

To better understand this condition, a three-dimensional typology is proposed, categorizing exceptional cases based on social-demographic, legal-political, and environmental-risk variables.

4.1. Social and Demographic Dimension

Several AUGI are home to aging populations, low-income residents, and socially vulnerable households. In many cases, the collective administrative structures required by Law No. 70/2015, such as joint owners’ commissions, are either inactive or absent, largely due to:

Advanced age of residents, leading to low participation in formal procedures;

Economic vulnerability, limiting the ability to co-finance infrastructure works;

Lack of social mobilization, as many residents are either disillusioned or unaware of their legal options.

These social factors act as de facto barriers to the implementation of the regularization process, even when legal avenues exist.

4.2. Legal and Political Dimension

Several obstacles relate to the legal configuration of the land and the governance model required for reconversion:

Unclear or disputed land ownership (e.g., occupied military or public lands);

Areas not formally classified as urban/urban expansion in PDMs which excludes them from Article 1 and Article 5 eligibility under Law No. 70/2015;

Lack of municipal political will or absence of enabling regulation (e.g., Art. 46’s exceptional authorization mechanisms not implemented);

Missing or dysfunctional administrative commissions, which are essential for initiating and managing the reconversion process under Article 15.

The Tabaqueira neighbourhood in Sintra is characterised by informal housing developments for residential and semi-industrial use. Despite the existence of some infrastructure, the neighbourhood is located close to protected forest areas, which causes environmental conflicts. The absence of an active administrative committee has hampered progress in regularisation, even where there is formal eligibility.

The Ribeirada neighbourhood in Odivelas has an ageing population with low social mobilisation, aggravated by informal forms of collective ownership that complicate legal formalisation. Although it does not present significant environmental risks, the absence of an administrative committee and legal fragmentation have brought the reconversion process to a virtual standstill.

In some municipalities, similar AUGI receive different treatment due to diverging interpretations of eligibility, creating perceptions of legal inequality and territorial injustice.

4.3. Environmental and Risk Dimension

Several AUGI are located in areas with significant physical or technological risk, including:

Slope instability and landslide-prone terrain (e.g., hillside settlements in Loures and Odivelas);

Flood-prone zones (e.g., Serra da Luz);

Infrastructure easements, such as aeronautical or telecommunication protection zones, which legally restrict construction and regularization.

These risks often serve as legal grounds for exclusion, particularly under Article 48 of the law, which designates such areas as insusceptible of regularization. Even when informal dwellings have existed for decades, their environmental context effectively places them in a legal dead end.

4.4. Proposed Typology: Cross-Analysis of Variables

The following

Table 1 synthesizes the key variables across the studied AUGI cases, offering a typological matrix that reflects their exclusion patterns and potential routes (or blockages) to regularization:

This typology reveals the cumulative nature of exclusion demonstrated by areas that score highly on all three dimensions and are the most difficult to integrate into the formal urban system, often despite decades of occupation and de facto consolidation.

4.5. Institutional Perspectives on Legal and Procedural Impasses

While field data and spatial analysis helped construct the typology of doubly informal areas, institutional voices added critical depth to understanding why these cases persist. Interviews with municipal technicians revealed a widespread perception of legal paralysis, particularly regarding areas classified under Article 48 of Law No. 70/2015 as insusceptible to regularization.

A revealing comment came from a senior official in Lisbon’s urban planning department, who acknowledged that: “There are neighborhoods that everyone knows cannot be regularized, but we also don’t know what to do with them.” (Santos, 2024).

This quote illustrates an underlying institutional deadlock: municipalities are aware of the legal limitations but lack policy alternatives. In practice, this often leads to a strategy of informal toleration or “freezing” of these territories, which are neither regularized nor removed from the urban system. The absence of political guidance, interdepartmental coordination, or dedicated relocation resources reinforces this stasis.

Such accounts underscore the need for a governance model that moves beyond the binary of legality vs. illegality and instead addresses informality as a durable urban condition that requires proactive and inclusive responses.

5. Discussion

The findings reveal a critical disjunction between the legal framework established by Law No. 70/2015 and the social, legal, and spatial realities of many AUGI in Portugal. While the law introduced mechanisms for regularization and sought to empower municipalities, it has proven inflexible and exclusionary for a significant portion of urban areas most in need of intervention.

5.1. Legal Inflexibility and Social Invisibility

Law No. 70/2015 frames the regularization process around a standardized legal model, one that assumes clear property ownership, active community governance, and financial capacity. However, many of the excluded AUGI present the opposite conditions as ambiguous land titles, aging or economically precarious populations, and environmental constraints that defy easy legal categorization.

The cumulative requirements set out in Articles 1 and 5 narrow the legal eligibility of settlements, particularly those partially classified as non-urban or located in sensitive areas. Moreover, Articles 46 and 48, which allow for exceptional authorizations or mandatory demolition with relocation, are inconsistently applied and rarely supported by concrete implementation tools or financial resources.

These rigid provisions do not account for the historical consolidation and lived urbanity of many of these areas. As such, the law effectively renders certain resident’s invisible, excluding them from the right to formal urban citizenship despite decades of physical and social integration into the city.

5.2. Municipal Disparities and Legal Fragmentation

The implementation of the AUGI regime is highly decentralized, relying on the discretion and capacity of local authorities. This has produced a patchwork of interpretations, where similar settlements are treated differently depending on local planning culture, technical expertise, and political will.

Some municipalities, such as Seixal or Odivelas, have invested in proactive engagement, while others have shown inaction, either due to limited resources or political resistance to assuming responsibility for informal settlements. The absence of clear national coordination and enforcement mechanisms leads to territorial injustice, where residents in similar conditions face different futures based on administrative boundaries.

Additionally, many municipalities have not implemented the exceptional tools provided by law, such as the creation of relocation programs or the approval of regulatory exceptions under Article 46. As a result, some AUGI remain legally stagnant even when viable technical solutions exist.

5.3. Spatial Justice and Unequal Citizenship

This situation reinforces a broader dynamic of unequal urban citizenship, where access to the legal city is mediated by property, governance structures, and geography. The inability of some residents to regularize their homes is not merely a technical failure, it reflects a deeper mismatch between the universal ideals of planning law and the particularities of lived urban experience.

Perceptions of injustice are especially acute in cases where neighbouring AUGI are regularized while others are excluded due to narrow interpretations of zoning plans or risk maps. This undermines trust in institutions and weakens public participation, especially in socioeconomically fragile communities.

5.4. Legal Silence and the Perpetuation of Informality

The long-term persistence of AUGI that remain outside formal urban integration is both a symptom and a cause of broader territorial dysfunction, particularly in metropolitan areas where these settlements are most concentrated. A key focus of this article is precisely on the structural causes behind this persistence, especially in the case of areas deemed legally “insusceptible to regularization” as defined in Article 48 of Law No. 70/2015. These areas are often excluded from the regularization process due to environmental constraints or physical risk conditions, such as floodplains, geotechnical instability, or ecological protection zones.

However, the legislation fails to provide concrete or compensatory solutions for the populations affected, leaving residents in a prolonged state of legal and spatial limbo. This vacuum contributes to the historical perpetuation of informality, with far-reaching consequences. Residents continue to live in precarious conditions, often in areas environmentally sensitive or unsafe, without proper infrastructure, legal security, or protection from eviction. Simultaneously, a parallel housing market persists, where informal dwellings are rented or sold without oversight, reinforcing spatial inequality.

This dynamic is further intensified by demographic change, particularly the aging of residents, which limits collective capacity to engage in bureaucratic processes or advocate for change. As a result, the legal and institutional silence surrounding these doubly informal AUGI has become a self-reinforcing mechanism of exclusion, undermining efforts toward spatial justice and sustainable urban governance.

5.5. Fragmented Governance and Missed Policy Integration

An additional layer of marginalization emerges from the disconnect between urban regularization policies and housing policy instruments. As highlighted in recent municipal-level research, the lack of coordination between Law No. 70/2015 and national housing programs, particularly the 1.º Direito strategy, leaves many residents of informal settlements without access to either legal recognition or adequate housing support (Santos, 2024). In practice, families living in areas considered insusceptible to regularization (e.g., under Article 48) are often ineligible for public housing aid, either due to land status issues, unclear tenure, or procedural bottlenecks.

This results in a policy vacuum, where two parallel systems, one focused on land regularization and the other on housing, operate without intersection, despite serving overlapping populations. The consequences are especially severe for vulnerable groups, who are excluded from both the formal housing market and the legal urban grid. Without a strategic articulation between planning and housing, informal settlements risk becoming permanently invisible to both systems, reinforcing territorial injustice and undermining the social goals of both legal frameworks.

5.6. International Comparison and Missed Opportunities

Internationally, countries such as Brazil and Spain offer more flexible frameworks for dealing with long-term informal settlements. In Brazil, the Estatuto da Cidade (City Statute) enables tenure regularization through a range of tools, including the recognition of social function of property, special zoning, and adverse possession, often accompanied by funding mechanisms and social safeguards (Fernandes, 2007).

In Spain, the Ley del Suelo allows for exceptions and planning adjustments for long-standing informal settlements, particularly when relocation is not socially viable. Moreover, both countries have invested in national support programs that complement municipal action, mitigating the disparities seen in the Portuguese model.

By contrast, the Portuguese framework lacks institutional support, financial redistribution, and legal adaptability, leaving municipalities and residents to navigate complex situations with limited tools.

6. Conclusions and Recommendations

6.1. General Remarks

This article has explored the structural barriers that prevent certain Informally Originated Urban Areas (AUGI) in Portugal from completing or even initiating their regularization processes. Through an interdisciplinary and empirical approach, we identified a subset of cases marked by “double informality”, settlements that are both historically marginal and legally excluded from the current framework established by Law No. 70/2015.

The typology developed in this study demonstrates that exclusion arises not from a single factor, but from the overlap of legal, social, and environmental vulnerabilities. These include ambiguous land tenure, lack of formal governance structures, limited resident capacity, and the presence of environmental risks. In many cases, the very populations who would benefit most from legal integration are those least equipped to navigate the system.

At the same time, the law places the burden of regularization primarily on residents and municipalities, without sufficient national coordination or institutional and financial support, resulting in uneven outcomes across the territory. As a result, spatial and legal fragmentation persists, undermining principles of territorial justice and the right to the city.

6.2. Policy and Legal Recommendations

To address these shortcomings and ensure more inclusive urban governance, we propose several policy directions:

6.2.1. Create a Dedicated Legal Framework for “Doubly Marginal” Areas

A new legal regime or sub-regime should be established to address AUGI that are currently excluded from Law No. 70/2015 due to:

Unclear urban classification;

Lack of administrative commissions;

Environmental or technical constraints.

This regime should allow for simplified procedures, contextual exceptions, effective solutions for the populations living in environmental risk areas and alternative compliance paths, including the recognition of long-standing occupation and urban consolidation.

6.2.2. Establish Decentralized Technical and Financial Support Mechanisms

The current model assumes that residents and municipalities possess the capacity and resources to manage reconversion processes. This is not the case in many of the most vulnerable areas. Therefore, we recommend the creation of:

Multidisciplinary technical support teams, coordinated at the regional level (e.g., by CCDR or DGT);

Targeted funding programs for infrastructure development and community engagement;

Legal aid and mediation services to assist residents with title clarification and collective action formation.

These support structures would help equalize access to regularization, particularly in socioeconomically disadvantaged contexts.

6.2.3. Improve Coordination Between Planning Instruments and Relocation Policies

For areas classified as “insusceptible to regularization” under Article 48, the law foresees demolition and rehousing, but implementation remains weak and fragmented.

To make this process more equitable and effective, we believe that is essential to:

Strengthen the link between planning instruments and rehousing programs (such as the Municipal Housing Charter);

Ensure that all relocation is preceded by social diagnostics and supported by realistic housing alternatives, preferably within the same municipality;

Use existing public housing stock or allocate public land for construction under affordable regimes.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.G. and L.C.; Formal analysis, J.G., B.C. and L.C.; Methodology, J.G., B.C. and L.C.; Resources, B.C.; Supervision, J.G.; Validation, B.C.; Writing – original draft, J.G., B.C. and L.C.; Writing – review & editing, J.G. and L.C.

References

- Alves, C. Áreas Urbanas de Génese Ilegal-Perfis Socio-Demográficos e Modelos de Reconversão. Master Dissertation for Master’s Degree in Urban Planning and Land Management, Universidade Técnica de Lisboa, Instituto Superior Técnico, Lisboa, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Antunes, J. Urbanização informal na Área Metropolitana de Lisboa: Origens, dinâmicas e respostas institucionais; Centro de Estudos Geográficos, Universidade de Lisboa: Lisboa, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Caldeira, T. Peripheral urbanization: Autoconstruction, transversal logics, and politics in cities of the Global South. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 2017, 35(1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calor, I.; Alterman, R. Comparative analysis of the legal and planning responses to non-compliant development in two advanced-economy countries. International Journal of Law in the Built Environment 2017, 9(3), 207–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chamusca, P. Urban Governance and Public Policies in Portugal. In Urban Change in the Iberian Peninsula: A 2000–2030 Perspective; Springer Nature Switzerland: Cham, 2024; pp. 313–330. [Google Scholar]

- Condessa, B.; Gonçalves, J.; Carvalho, L. Duplamente informais: Situações de exceção aos processos de reconversão urbanística das AUGI; Comunicação apresentada no Encontro da Associação Portuguesa para o Desenvolvimento Regional (APDR), 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira, V. Território e habitação: A política de solos e a génese das AUGI em Portugal; Celta Editora: Lisboa, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Global Alliance Against Hunger and Poverty. Multilevel governance: A key strategy for SDG localization and inclusive urban development. 2023. Available online: https://globalallianceagainsthungerandpoverty.org/policy-instruments/multilevel-governance/.

- Gonçalves, J.; Alves, C.; Nunes da Silva, F. Do ilegal ao formal: Percursos para a reconversão urbana das Áreas Urbanas de Génese Ilegal em Lisboa. In Da irregularidade fundiária urbana à regularização: Análise comparativa Portugal–Brasil; Bogus, L., et al., Eds.; EDUC: São Paulo, 2010; pp. 161–192. [Google Scholar]

- Gonçalves, J.; Condessa, B.; Carvalho, L. Duplamente informais: Excecionalidade e marginalidade nos processos de reconversão urbanística; CiTUA–IST e CIAUD–FAUL: Lisboa, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Harvey, D. The right to the city. New Left Review 2008, 53, 23–40. [Google Scholar]

- Holston, J. Insurgent citizenship: Disjunctions of democracy and modernity in Brazil; Princeton University Press: Princeton, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Holston, J. Insurgent citizenship: Disjunctions of democracy and modernity in Brazil; Princeton University Press, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Lefebvre, H. Le droit à la ville; Anthropos: Paris, 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Lopes, D. Áreas urbanas de génese ilegal. Problemas suscitados por um regime legal excepcional que teima em perpetuar-se no tempo. De Legibus-Revista de Direito da Universidade Lusófona 2020, 0, 265–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrison, T.; Lane, M.; Hibbard, M. Inclusive planning for urban resilience: Strategies for vulnerable populations. Urban Planning Review 2024, 36(2), 89–104. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2772741624000085.

- Pereira, M.; Ramalhete, F. Planeamento e conflitos territoriais: uma leitura na ótica da (in) justiça espacial. Finisterra 2017, 52(104). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pruijt, H. Is the institutionalization of urban movements inevitable? A comparison of the opportunities for sustained squatting in New York City and Amsterdam. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 2003, 27(1), 133–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raposo, I.; Valente, A. Diálogo social ou dever de reconversão? As áreas urbanas de génese ilegal (AUGI) na Área Metropolitana de Lisboa. Revista Crítica de Ciências Sociais 2010, (91), 221–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, A. Urban informality: Toward an epistemology of planning. Journal of the American Planning Association 2005, 71(2), 147–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, A. Urban informality: Toward an epistemology of planning. Journal of the American Planning Association 2005, 71(2), 147–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, A. O processo de legalização dos territórios de génese ilegal na área metropolitana de Lisboa. Master Dissertation for Master’s Degree in Legal Practice – Specialising in Administrative Law and Public Administration, Universidade de Lisboa, Lisboa, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Soja, E. W. Seeking spatial justice; University of Minnesota Press: Minneapolis, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Tulumello, S.; Alegre, F. Urban rehabilitation in Lisbon: A critical overview of an era of restructuring. European Planning Studies 2016, 24(8), 1432–1453. [Google Scholar]

- UN-Habitat. Inclusive, vibrant neighbourhoods and communities: Urban regeneration with a human rights and people-centred approach; United Nations Human Settlements Programme (UN-Habitat), 2023. Available online: https://unhabitat.org/sites/default/files/2023/06/fs1-inclusive_vibrant_neighbourhoods_and_communities.pdf.

- UN-Habitat. World Cities Report 2020: The Value of Sustainable Urbanization; United Nations Human Settlements Programme, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Yiftachel, O. Theoretical notes on ‘gray cities’: The coming of urban apartheid? Planning Theory 2009, 8(1), 88–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).