1. Introduction

Transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) is a non-invasive neuromodulation technique that allows neuronal plasticity through the delivery of a low-intensity positive (anodal) or negative (cathodal) electric current employing electrodes positioned in a previously established area, leading to changes in neuronal resting membrane potential [

1]. Several published studies describe tDCS effects on stimulation or inhibition of the synaptic transmission between neurons. tDCS can be combined with training of cognitive or motor skills to evaluate an improvement in the performance of some tasks. It has also been proposed as a technique with therapeutic effects in clinical protocols for different diseases, including Parkinson’s disease [

2,

3,

4].

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is a neurodegenerative disorder with a progressive loss of dopaminergic neurons, especially those located in the midbrain [

5]. In addition to a dopaminergic deficit, the pathogenesis of PD has also been explained by mitochondrial and lysosomal dysfunction, together with alpha-synuclein deposits. These deposits relate to neuronal death in multiple nervous system nuclei, which may explain diverse PD-specific non-motor symptoms [

6].

The cardinal signs of PD are mainly of motor nature: bradykinesia, rest tremor, postural changes, and muscular rigidity. However, the non-motor symptoms also require specialized treatment due to the significant impact on quality of life. These include olfactory changes, sleep disorders, postural hypotension, constipation, depression, anxiety, psychosis, and cognitive impairment [

6].

Despite the impossibility of ascertaining the etiology of PD, some theories explain the degenerative process in terms of impairment of the affected neurological structures [

7]. In this context, PD can be described by its stages, as comprising three main phases: Initially, the premotor phase is characterized by the death of neurons of the lower brainstem (causing sleep disturbance symptoms), progressing through the olfactory bulb (emergence of hyposmia) and the pontine nuclei [

6]. Then, in the motor phase, the mesencephalic region is affected (motor symptoms). In the advanced stage, the neuronal deterioration affects the cerebral cortex, impaired impairment cognitive and behavioral functions. In this context, scientists call attention to non-motor predictive signs, which signal the beginning of the pathology and prodromal predictors, indicating the degree of neuronal involvement and prognosis of the disease [

7].

To adequately characterize PD symptoms, physicians and researchers use assessment scales and tests that are validated and widely recognized. For instance, there are scales for the screening of signs and symptoms resulting from Parkinson’s disease, such as the Hoehn & Yahr (H&Y) scale, specific for the degree of disease staging; the Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (UPDRS), which assesses various domains, including motor function. There is also the Parkinson’s Disease Sleep Scale (PDSS), which identifies the occurrence of sleep disturbances [

9], and the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS), a wide-ranging instrument for mood symptoms in PD [

8,

9].

In addition, the Parkinson’s Disease Cognitive Rating Scale (PD-CRS) is used to assess cognitive impairment and executive function deficits (EFs) [

10]. Furthermore, the Stroop Test also provides information about the EFs by measuring the interference effect generated through the evaluation of congruent and incongruent stimuli consisting of color names written in either matching or non-matching colors and presented in pseudo-random order. The applicability of these tools and the Stroop Test for patients with Parkinson’s Disease has been well described in the literature [

11,

12,

13].

Previous studies have investigated the effects of tDCS on motor and non-motor symptoms. Concerning motor symptoms, Ishikuro et al. (2018) identified that anodal stimulation significantly increased scores of motor functions in the Fugl Meyer Assessment set and significantly decreased scores of motor disability in UPDRS-III compared with sham and cathodal stimulation. In another trial, the researchers verified that anodal tDCS improves patients’ walking speed with or without concomitant physical therapy treatment [

14].

Regarding the beneficial effects of tDCS on non-motor functions, a study conducted by a group of researchers in Iran showed significant results in the quality of sleep of participants with PD, as well as a decrease in their fatigue symptoms [

15,

16]. Benusi and collaborators found that participants had a lower incidence of risky decision-making and displayed enhanced executive functions, inhibitory control, and cognitive flexibility. In Australia, a clinical trial with follow-up showed improvement in PD patients’ cognition (language, global memory), and executive functions (working memory, cognitive flexibility), either with cognitive training or with tDCS alone [

17,

18].

Doruk et al. identified significant results in the Trail Test after tDCS and found that the DLPFC-L group showed a greater reduction in Beck depression inventory scores [

2]. It is also important to highlight that using tDCS for depression is common in clinical practice with an anode over the L-DLPFC and a cathode over the right supra-orbital region. The beneficial effects of tDCS have also been identified in other studies [

11,

19].

Considering that Parkinson’s disease is multi-causal and substantially compromises the patient’s quality of life, studies that offer noninvasive and effective treatments for such symptoms are of great value and potentially relevant. In the present study, we investigate the effects of tDCS stimulation in patients with Parkinson’s disease on motor function, sleep disorders, mood swings, cognition, and executive functions.

4. Discussion

Levodopa is a primary treatment for PD with beneficial effects for most patients. However, long-term complications such as motor fluctuations, dyskinesias, major depression, and psychotic symptoms are possible. Moreover, as PD progresses, levodopa effects wear off and other clinical manifestations also occur, both motor and non-motor, such as freezing of gait and dementia [

7].

Additional strategies that improve the patient’s symptoms and quality of life are essential. In this regard, recent studies have suggested a possible role for non-invasive electrical stimulation. Transcranial electrical stimulation can modulate resting membrane potentials, therefore generating changes in the polarization and depolarization process that may improve symptoms of neurological diseases [

27]. tDCS allows synaptic plasticity while exciting or inhibiting brain regions, an adaptive neural strategy.

Differently from transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS), tDCS cannot produce motor evoked potentials since the change in resting membrane potential does not reach the threshold for action potential firing. However, prolonged modulation, applied for more than three minutes, can generate changes in glutamatergic and GABAergic receptors [

28]. The spatial resolution of tDCS is uncertain since it may also influence deeper brain structures connected to the target cortical region. [

29].

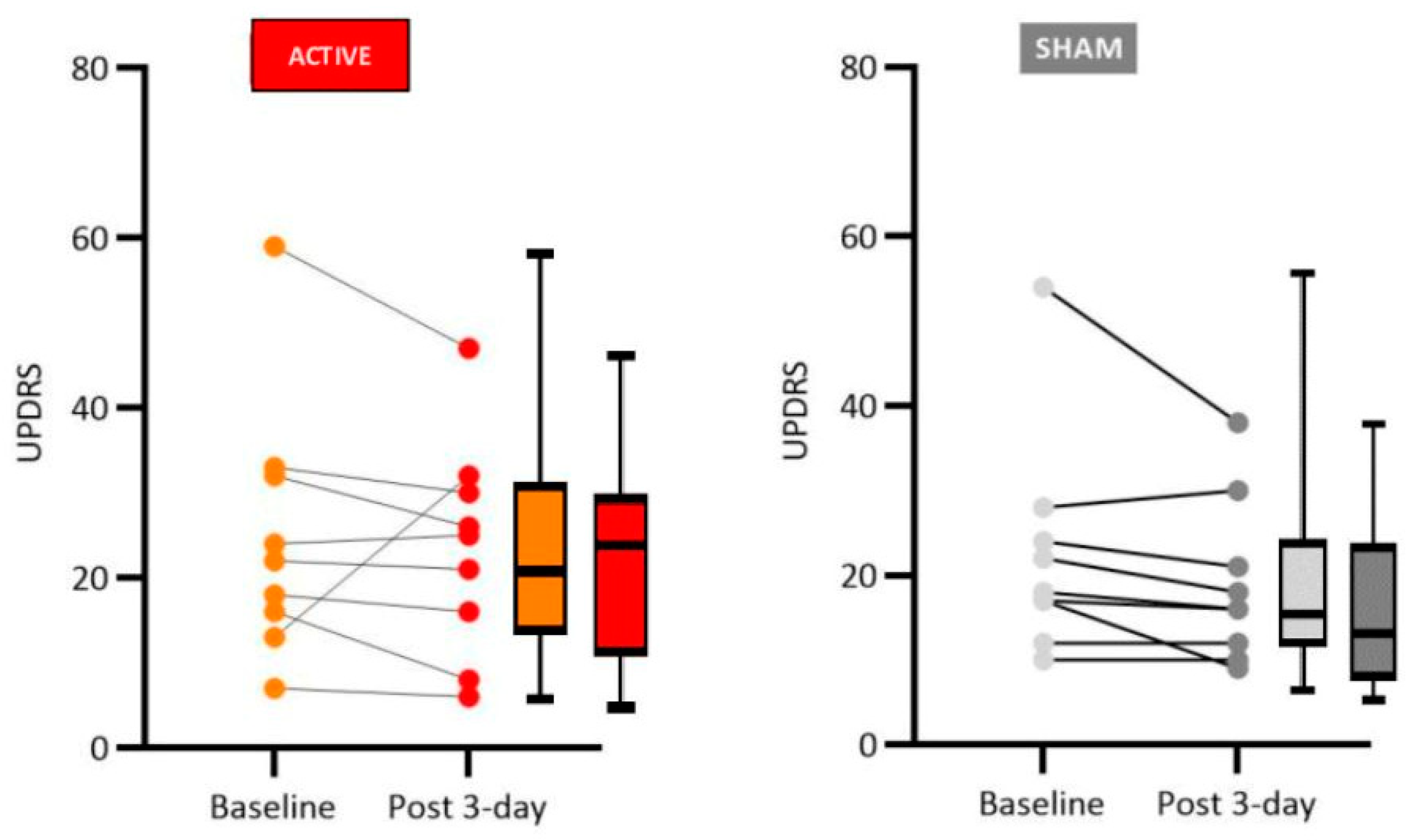

Our results have shown significant improvement in motor function in PD patients who received active tDCS anodal stimulation to the left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex region (2mA for 20 min, 3 sessions), particularly regarding rigidity, the finger tapping test, posture, and general gait patterns. Non-significant improvement was observed for participants who received sham tDCS.

It is important to point out that other authors have previously reported both similar and divergent results. Therefore, at the present stage of this field of study, it is important to try to replicate previous results so that meaningful meta-analysis can be done to instruct future controlled clinical trials. An example of these uncertainties concerns studies that investigated the effects of tDCS on PD patients using anodal stimulation to the left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (L-DLPFC). Doruk et al. [

2], in ten neuromodulation sessions with an intensity of 2mA, did not obtain significant improvement in motor function, while Chang et al. [

30], with five sessions, employing a current intensity of 1mA for 20 minutes, obtained a satisfactory short-term response for the occurrence of freezing. Swank [

31], in a study that employed two sessions, with a current intensity of 2 mA for 20 minutes, obtained moderate evidence of improved motor functions measured by UPDRS.

Studies in which tDCS was applied to the primary motor area presented more agreement regarding satisfactory results. Fregni et al. [

28], with a single session and a current intensity of 1mA for 20 minutes, observed significant improvement in motor function, as did Benninger [

21] with eight sessions, at 2mA of intensity and 20 minutes of stimulation; Valentino [

32], with five sessions, at 2mA intensity for 20 minutes, and Kaski [

33] with five sessions, at 2mA intensity for 3 minutes of tDCS, employing a dancing task. The most significant motor effects described in the literature were improvements in gait, rigidity, and bradykinesia, evaluated with

the Timed Up and Go motor test, as well as other gait performance assessments [

19,

34].

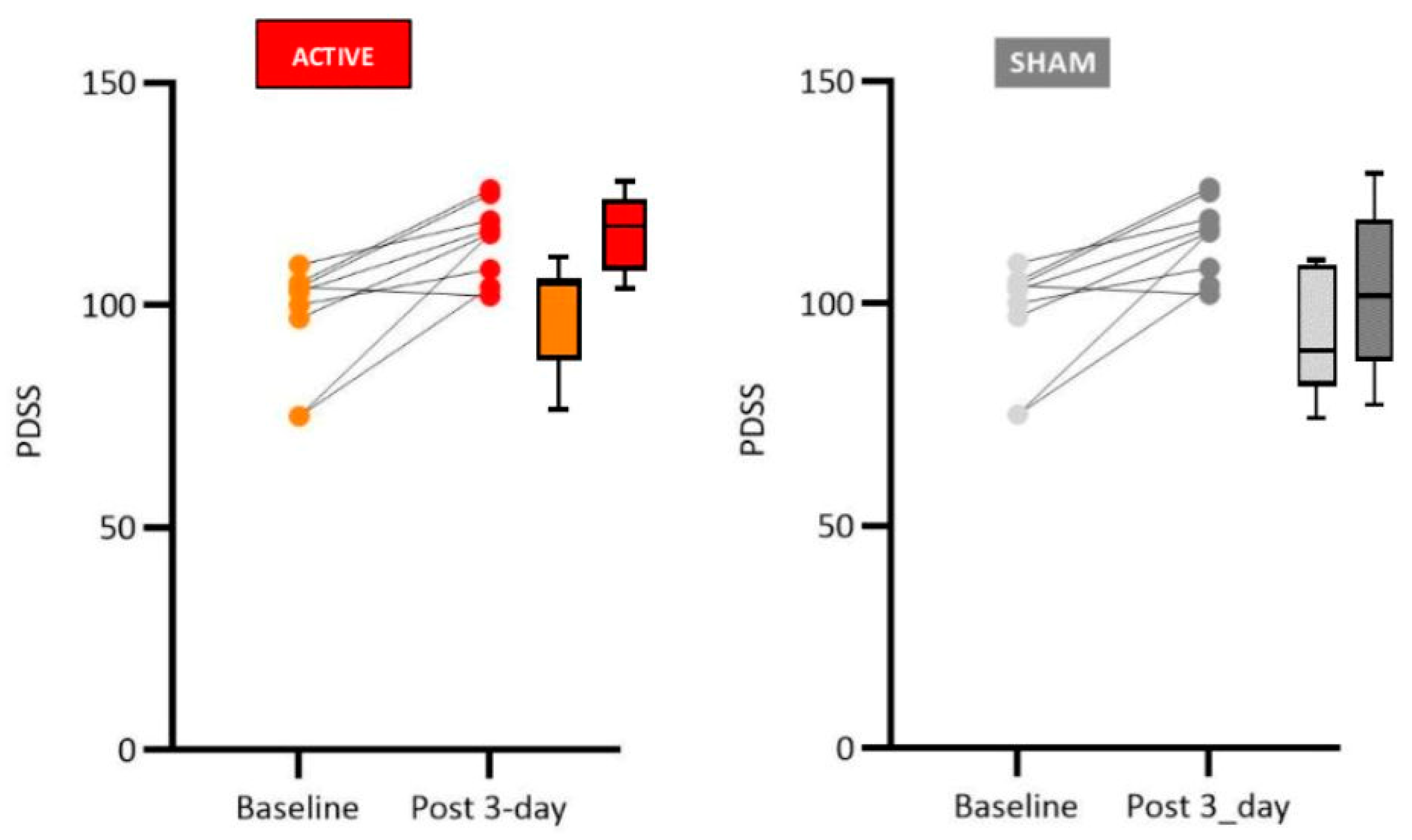

Although sleep disorders in PD are known to represent a major aspect of Parkinsonian patients’ complaints, this variable is not a frequently evaluated parameter in tDCS studies. Despite the low rate of sleep assessments, Hadoush and collaborators [

28], using a study protocol of anodal tDCS applied to the L-DLPFC, in 20-minute sessions with an electrical current intensity of 2mA, obtained significant improvements in sleep latency, global sleep quality, reduction in sleeping medication, in sleep disorders, as well as a reduction in daytime dysfunction. Forogh and co-workers [

16] investigated the effects of anodal tDCS on the L-DLPFC, during 10 sessions, each lasting 20 minutes with a current intensity of 2 mA. The results were reevaluated after three months, and a significant improvement in fatigue was noted, something that was questioned by the researchers as being an effect of improvement in mood and not necessarily in sleep quality.

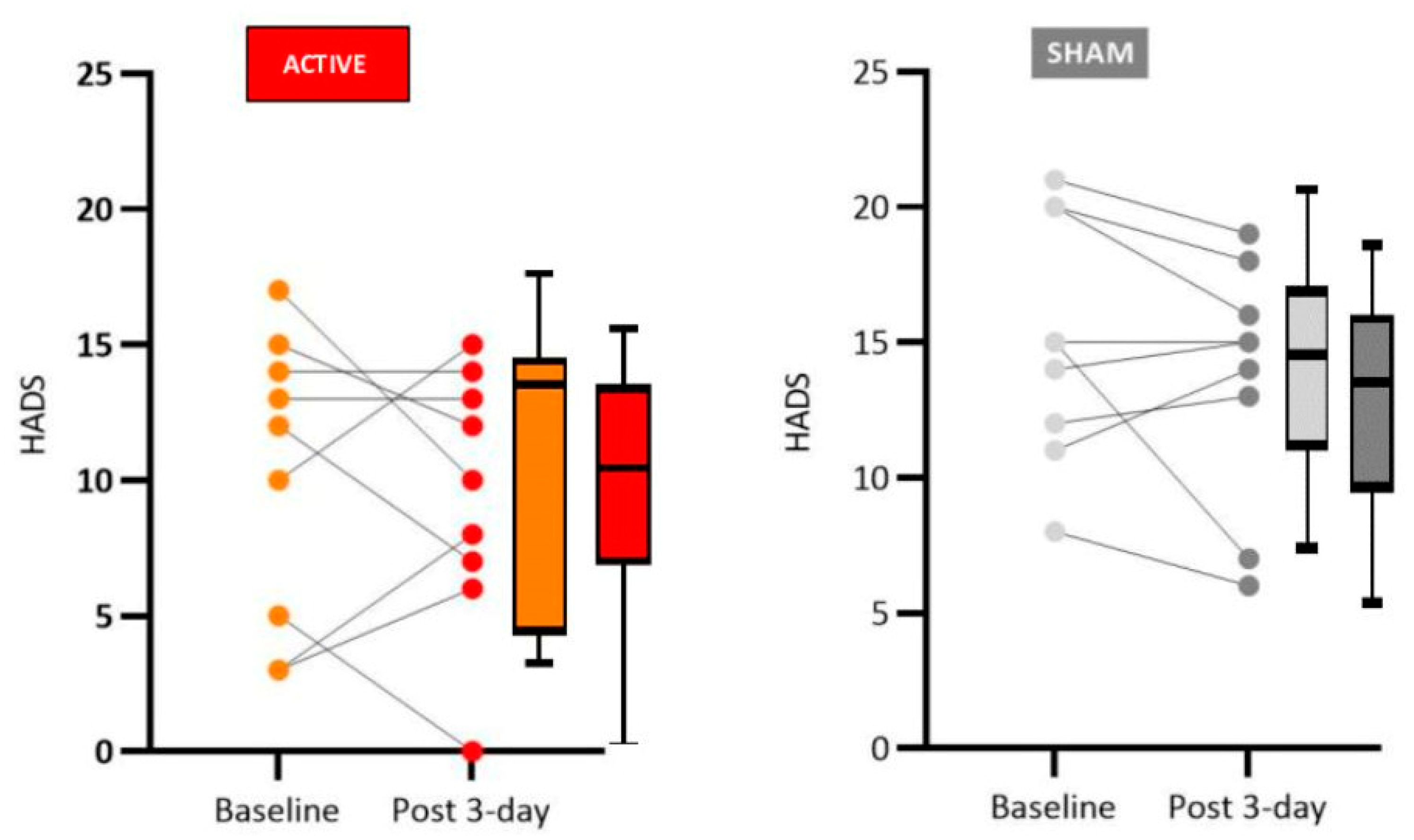

The results obtained in our study regarding the mood domain align with what the literature shows for anodal L-DLPFC stimulation for mood, which is the most consolidated protocol for depression treatment and is already used in clinical practice. Patients in the active group showed an improvement in mood, particularly clear for a decrease in anxiety. The literature explains the improvement in depressive symptoms and other behavioral effects of tDCS through a process akin to long-term potentiation (LTP) in which there is a permanent increase in synapse strength due to high-frequency stimulation produced by a chemical stimulus. LTP is likely triggered by applying a low-intensity direct current that changes the intracerebral current flow, generating effects compatible with mood improvement [

35,

36,

37].

Moreover, depression in PD is associated with changes in dopaminergic pathways, and cortical and subcortical afferents in which the irregular neuronal excitability reaches L-DLPFC causing psychiatric manifestations in some patients. It is likely that anodal tDCS over the L-DLPFC also produces neuromodulation of the DA system in this area [

37].

Again, there is some controversy regarding the mood modulation of PD patients by tDCS. Some studies employing L-DLPFC tDCS with PD patients have shown improvement in anxiety and depression [

17,

39], while others did not observe mood improvement with a single session of tDCS. Manenti [

18] used the neuromodulation protocol with a constant current of 2 mA applied for 7 minutes (with a ramping period of ten seconds at the beginning and end of the stimulation) and observed a slight momentary improvement in the mood of the participants. Lawrence [

17] used a protocol with an intensity of 2mA for 20 minutes and the effects on depression were significant when associated with cognitive training for four weeks. Impressive results on mood improvement were observed in the studies by Pereira [

39], who conducted a study with a single session of tDCS with the intensity of 2 mA.

Another important aspect related to PD is that, as the pathology progresses, a specific dementia picture, called Parkinson’s Disease Dementia, becomes evident. Therefore, the cognitive profile of patients who develop this dementia has greater impairment in executive functions, attention, and visuospatial memory (which would be associated with subcortical changes) and a lesser impairment in declarative memory, language, and practice (which would be associated with cortical changes) [

39].

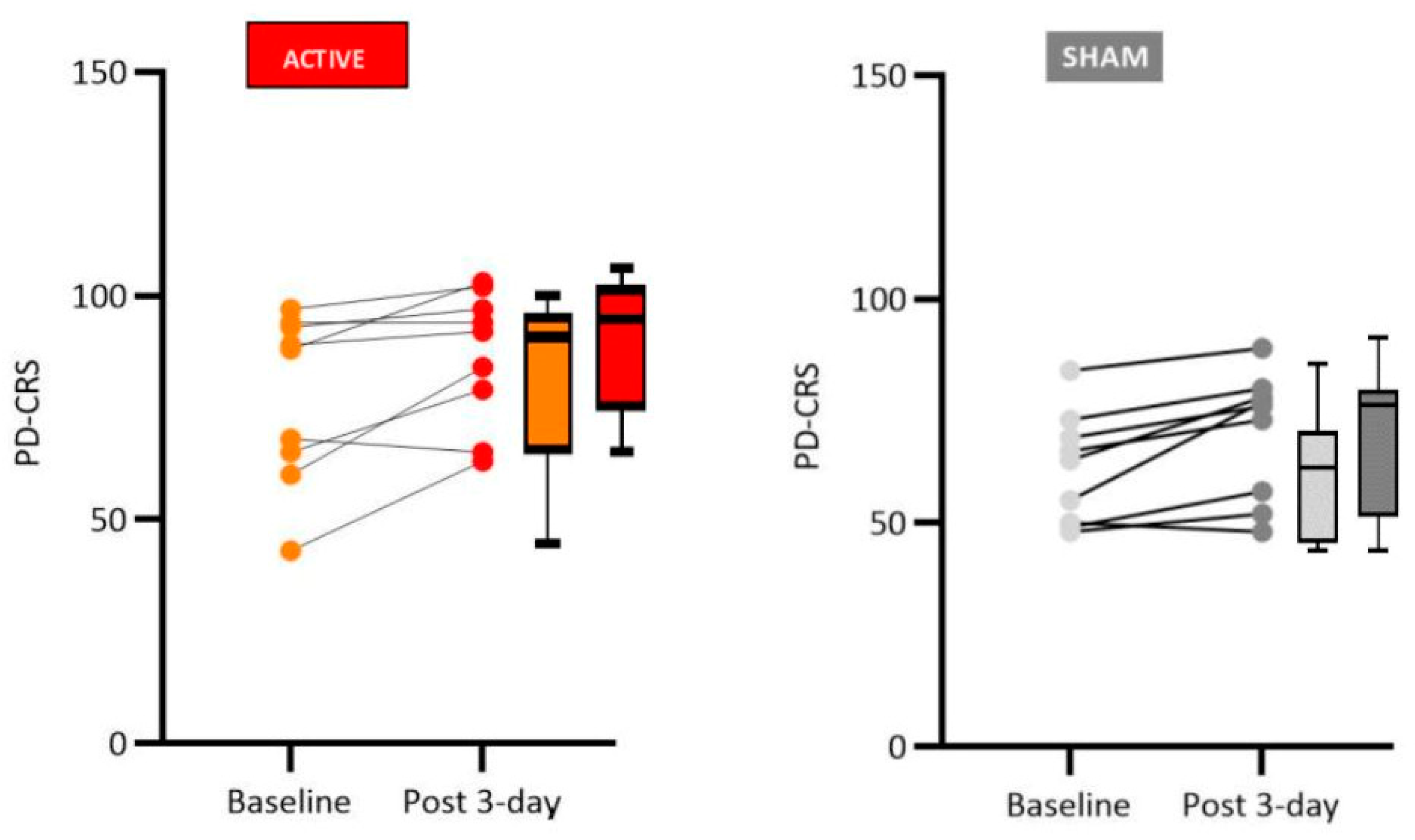

We found significant improvement in patients who received active tDCS stimulation compared to sham tDCS in cognitive functions related to verbal memory (free and immediate recall), naming by visual confrontation, clock copy test, and verbal fluency. Although the sham group did not present significant changes concerning pre- and post-stimulation tests (Wilcoxon test, see tables in the Results sections for details), the medians were slightly reduced between the phases, suggesting a possible learning effect for repeated tests. Therefore, the difference observed between active and sham control groups is likely due to the tDCS treatment and not only to the learning effects of repeated testing.

Regarding the cognitive effects of anodal tDCS when applied in L-DLPFC of patients with PD, the literature points to the effectiveness of the technique, thus corroborating our results. For instance, Boggio et al. [

38] using a 2mA protocol of current intensity applied for 20 minutes in a single session observed an increase in the scores of the response time and working memory test. Pereira et al. [

39] identified a significant improvement in phonological verbal fluency after a 20-minute session, applied with a current intensity of 2mA.

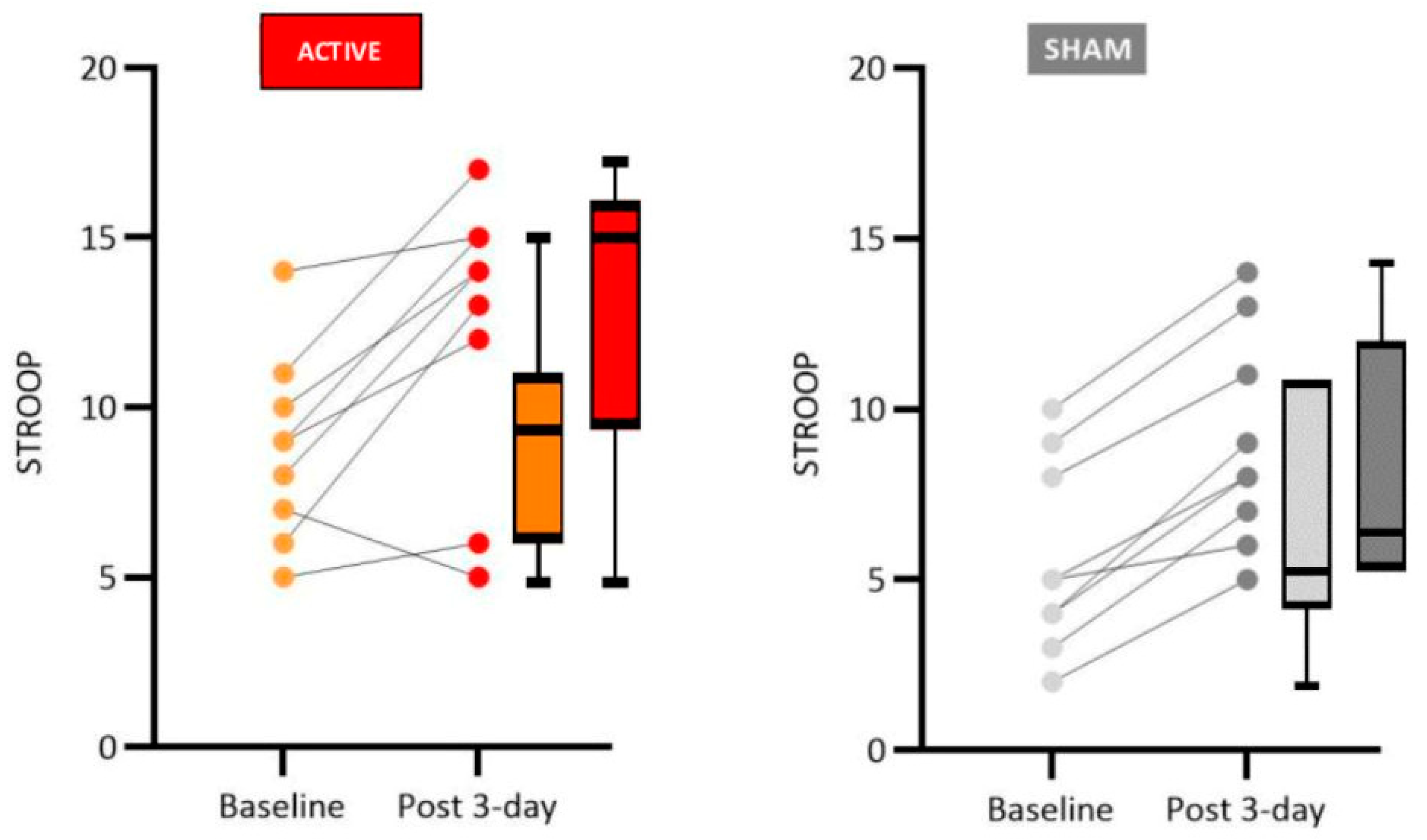

The Stroop Test is widely used in evaluating executive functions in patients with PD because it measures an ability commonly impaired in pathology, the inhibitory control [

40]. Studies show that the Stroop test is reliable for identifying deficits associated with L-DLPFC and the main motor area [

6,

41].

The performance of our patients who received real tDCS showed a significant improvement in the number of correct answers and error reduction in the Stroop test, suggesting activation of executive functions with increased inhibition control, cognitive flexibility and working memory.

Regarding executive functions, Doruk [

2] reported that anodal tDCS over the L-DLPFC, after 20-minute sessions of 2mA stimulation, improves the performance of the Trail Making Tests. Manenti and collaborators [

19] investigated the effects of anodal transcranial direct current stimulation applied over the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex and combined with physical therapy in PD patients. Their results indicated improved motor abilities, reduced depressive symptoms, and increased performance in the Parkinson’s Disease Cognitive Rating Scale and verbal fluency test. Lawrence et al. [

17] showed significant improvements across executive function, attention/working memory, memory, language, activities of daily living, and quality of life.

There are some potential limitations in this study, such as the small number of participants and the low number of tDCS sessions and follow-up time. Future cross-over studies would be useful to observe, with greater accuracy, the effects of treatments with the patients as their controls. However, an appropriate wash-out time interval must be determined to prevent the residual effects of previous stimulations. Another limitation was the unblinded condition of the examiners. Since one of the researchers applying tDCS also had to be trained for scoring the patients, the study was not double-blinded, a problem that should also be addressed in future studies.

Another confounding factor is the variable drug regimens of the patients included in the study. However, for medical and ethical reasons, it is impossible to withdraw or standardize drug treatments in all patients. Many patients were receiving benzodiazepines. Many of our patients were on benzodiazepines, which raises the question of possible pharmacological interference with our results. However, neuroplastic after-effects of tDCS are NMDA-receptor dependent [

42]. Anodal after-effects can be selectively suppressed by the sodium channel blocker carbamazepine and the calcium channel blocker flunarizine [

43]. tDCS after-effects are also thought to be mediated by synaptic modulation similar to those occurring in long-term potentiation studies. In this regard, Xu and Sastry [

44] have found that benzodiazepine receptors do not participate in LTP induction. Thus, it is unlikely that the use of benzodiazepines by our patients has had a significant effect on the observed tDCS after-effects.

Finally, larger randomized-controlled trials, using more than one scale to assess motor function and with extended follow-up periods are needed for elucidating the potential role of this new treatment modality in the clinical management of PD patients.