1. Introduction

Alzheimer’s Disease (AD) stands as one of the most pressing health challenges of our time, characterized by its progressive cognitive decline and the absence of a definitive cure. As the “baby boomer” generation ages, the number of those affected by AD is projected to double every 5 years and is predicted to reach 152 million by 2050 [

1].

Among the pursuit of innovative therapeutic interventions, Transcranial Pulse Stimulation (TPS) emerges as a promising avenue, offering a non-invasive approach that uses short, repetitive shockwaves. While initial studies have shown encouraging short-term effects of TPS on cognitive functions in Alzheimer’s patients [

2,

3], the need for long-term investigations to comprehensively assess its safety and effects remains utmost. These studies on short-term effects revealed that only a minority of stimulation sessions were associated with side effects of mostly minor severity, with headaches being the most prevalent, thus claiming TPS as a safe method [

2,

3]. This paper embarks on a longitudinal analysis, delving into extended-term data to elucidate the enduring impact of TPS on cognitive performance in Alzheimer’s.

While the complete effect of TPS remains unclear, Popescu et al., found a reduction of cortical atrophy after TPS stimulation in Alzheimer’s patients [

4]. This result was predominantly found in patients that also improved in neuropsychological testing. Given that a highly focal method is used in several brain areas, it is important to examine specific changes in cognitive domains, rather than solely relying on general neuropsychological scores and improvement, as observed in most conducted studies. The area specificity of TPS was shown by a fMRI study that examined visuo-constructive functions that correlate with areas that were not stimulated and showed a decrease after treatment, possibly due to disease progression without symptomatic treatment effect [

5]. TPS has also shown to improve depressive symptoms [

3,

6], which are common in AD. Generally, a disease progression meta-analysis for Alzheimer’s Disease showed that a worsening by 5 points in a neuropsychological test battery, called that Alzheimer Disease Assessment Scale (ADAS), can be expected over a year [

7]. Considering this, an improvement, or a stable score for over a year would be considered a benefit and a suggestion to use TPS as an add-on therapy.

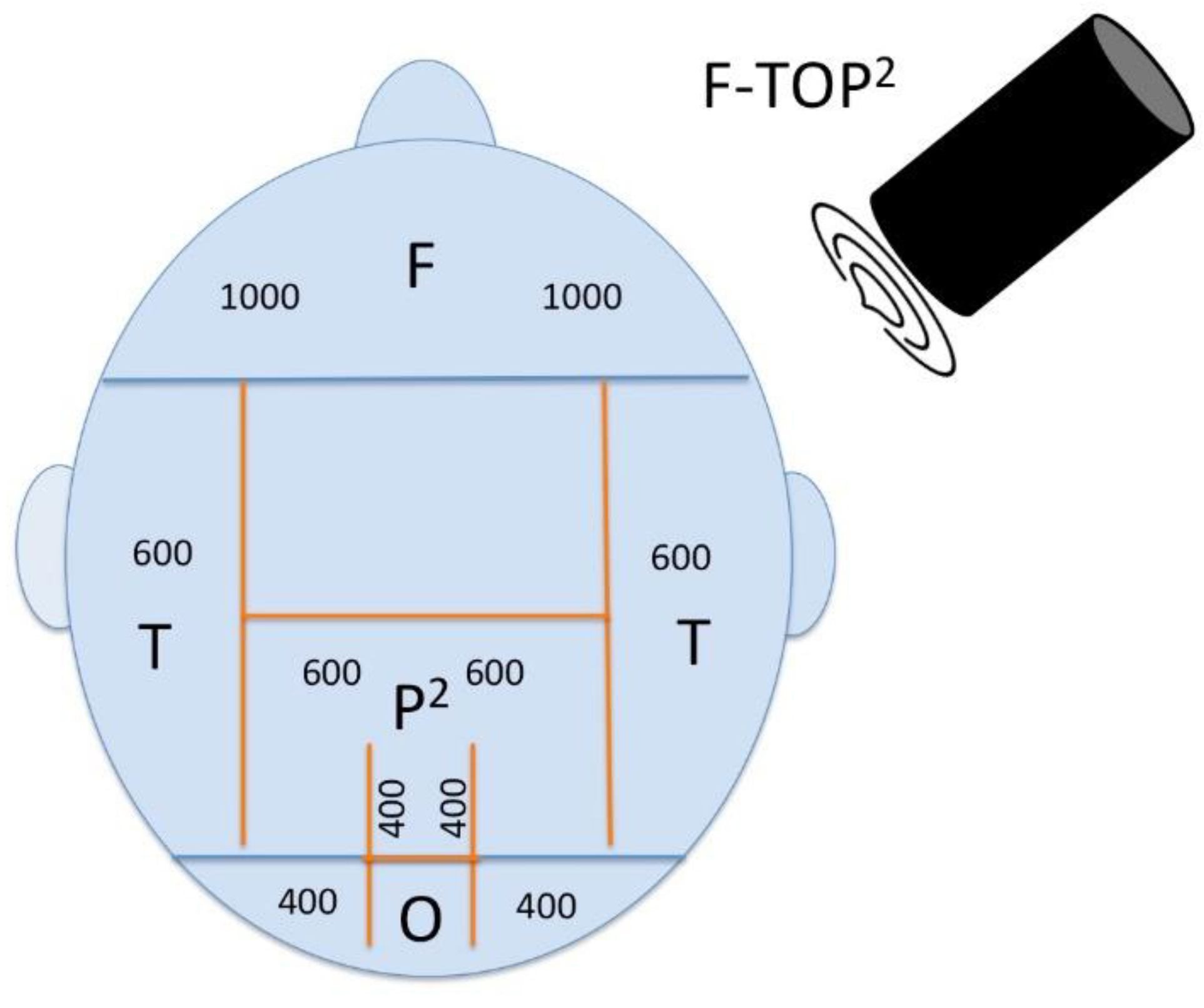

The commonly used treatment protocol for TPS targets the precuneus, bilateral parietal lobe, bilateral frontal lobe, but the protocol used in this paper involves the bilateral temporal lobe as well [

3]. The importance of targeting the precuneus, a key node for the default mode network effected by Alzheimer’s Disease, was shown by a recent randomized, double-blind, sham-controlled study that applied repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation over the precuneus and showed a delay of cognitive and functions decline [

8]. Moreover, FDG-PET imaging studies demonstrate early regional hypometabolism of posterior brain areas, such as the parietal lobes in patients with Alzheimer’s Disease [

9]. Furthermore, Prefrontal cortex regions play pivotal roles in cognitive functions associated with social, emotional, and motivational behaviors[

10], making them crucial targets for treating AD. Research on functional architecture of memory, especially episodic memory, have identified the hippocampus and the anterior-temporal and posterior-medial system [

11]. Therefore, our protocol targets the bilateral temporal lobe. Even though it has not visualized on the MR-navigations system that TPS can reach as deep as the location of the hippocampus, from the mechanisms of action of TPS it is assumable that temporal stimulation reaches that area.

Cognitive decline in episodic memory develops faster in patients with dementia, compared to normal aging, where the decline in speed of information processing and executive functions develops first [

12]. In normal disease progression different symptoms can be seen at different stages of AD. In mild AD, symptoms like loss of concentration, orientation and change in mood appear. Moderate AD includes increased memory loss, loss of impulse control, as well as trouble in reading, writing, and speaking [

1]. Since memory dysfunction is not always predominant cognitive symptom for patients with Alzheimer’s disease [

13], it is important to look at different cognitive domains and how these are affected by a new add-on treatment method. Especially language and visuospatial presentations are common symptoms in early Alzheimer’s progression [

13] and should, therefore, be targeted.

This article investigates the first long-term neuropsychological outcomes for over a year using the consistent treatment of TPS for patients with Alzheimer’s.

Hypotheses for the study were:

- i)

TPS is safe with respect to number and severity of Adverse (Device) Events, A(D)E

- ii)

Cognitive scores improve after first stimulation cycle

- iii)

Cognitive and affective scores stay stable after one year of treatment

- iv)

iv) A stronger effect can be seen in memory and speech compared to visuo-construction due to the targeted neuroanatomical treatment areas

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

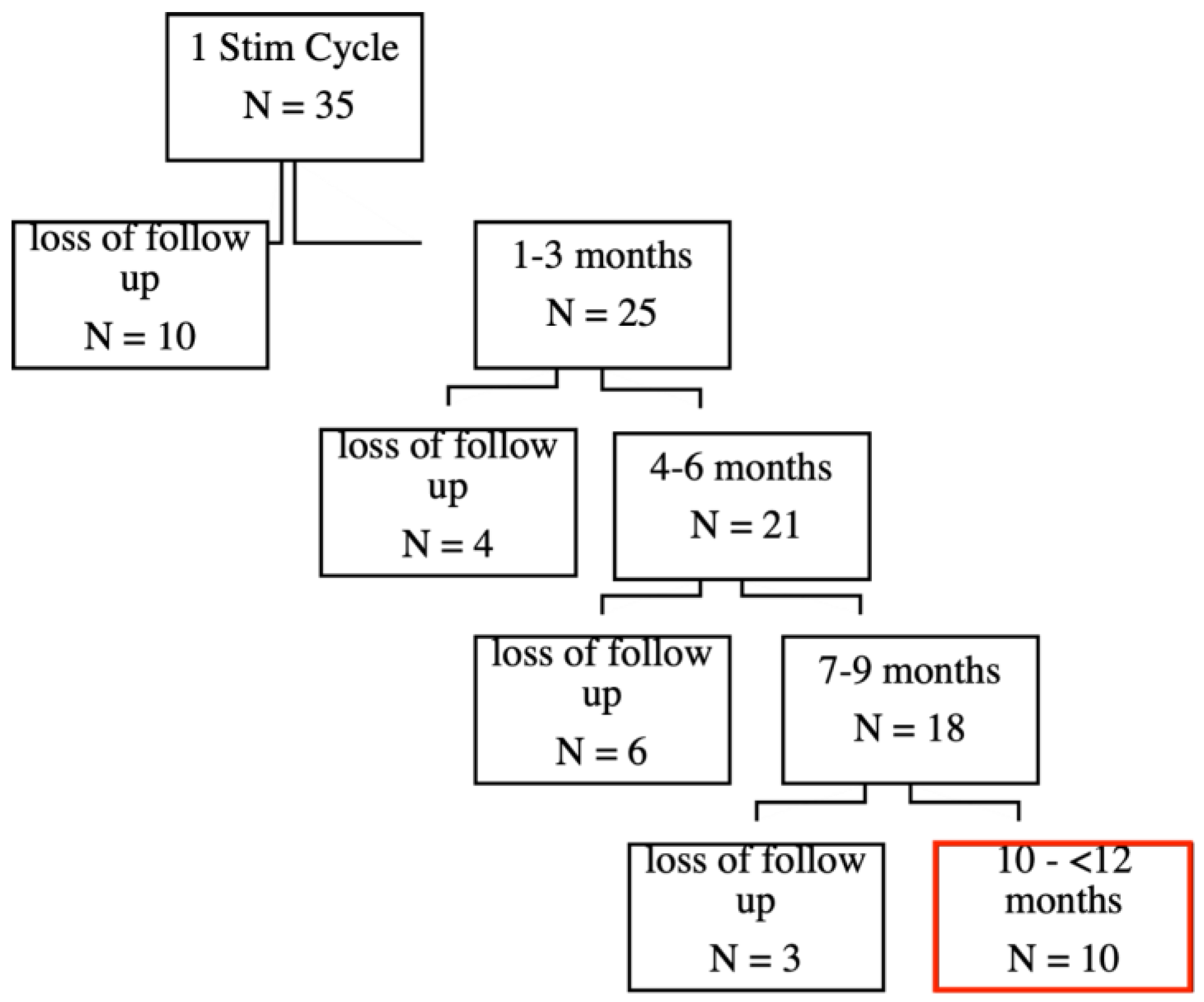

Initially, 35 patients completed the first stimulation cycle, which consisted of six sessions within two weeks. See our previous publication for the short-term effects [

3]. During the follow-up period, there was a gradual loss of participants due to various reasons, including discontinuation or unavailability (see

Figure 1).

Importantly, some patients are still actively undergoing treatment and are currently in the 4–6 month or 7–9 months follow-up periods. This reflects that the data is dynamic, and the number of patients in follow-up stages might continue to evolve as treatments progress.

For this paper, ten patients (eight male, two female, age range 59 – 79 years, M = 70.7) diagnosed with Alzheimer’s Syndrome meeting the criteria outlined by clinical evaluations, MRI and CSF (NIA-AA criteria) treated over a year with TPS at the Department of Neurology and Neurorehabilitation at Hospital zum Heiligen Geist in Kempen, Germany, were included in the long-term database. Demographics of those patients that were included in the analysis are illustrated in

Table 1. Participants were selected based on a defined Alzheimer’s Clinical Syndrome, grounded by a progressive change in memory function (using scores from the Minimental Status Examination) and impairment of daily living for > six months. Exclusion criteria for TPS treatment were relevant pathologies unrelated to Alzheimer’s, non-compliance with the treatment protocol, blood clotting disorders, oral anticoagulation, corticosteroid treatment in the last six weeks, or epilepsy.

Cognitive impairment was defined using the Mini-Mental Status Examination (MMSE): 30–27, no impairment, 26–20, mild impairment, 19–10, moderate impairment, and <10, severe impairment. Diagnostic criteria were assessed according to the NIA-AA criteria. “A” labels biomarker of Aß plaques, “T” labels biomarkers of fibrillar tau, and “N” labels biomarkers of neurodegeneration or neuronal injury [

14].

a One patient was included without biomarkers tested

b Alzheimer’s and concomitant suspected non-Alzheimer’s pathological change.

C Alzheimer’s clinical syndrome with non-Alzheimer’s pathological change.

The prospective inclusion in a registry of all TPS treated patients was part of the local registry approved by the Ethics Committee of the regional Medical Chamber (Ärztekammer Nordrhein, Nr. 2021026).

2.2. Transcranial Pulse Stimulation (TPS)

For the stimulation, the Neurolith © TPS device from Storz Medical was used that allows neuronavigation using individual 3D T1 isometric voxel MRI scans. The treatment protocol involved the application of TPS using specific parameters: 4 Hz, 0,20mJ/mm

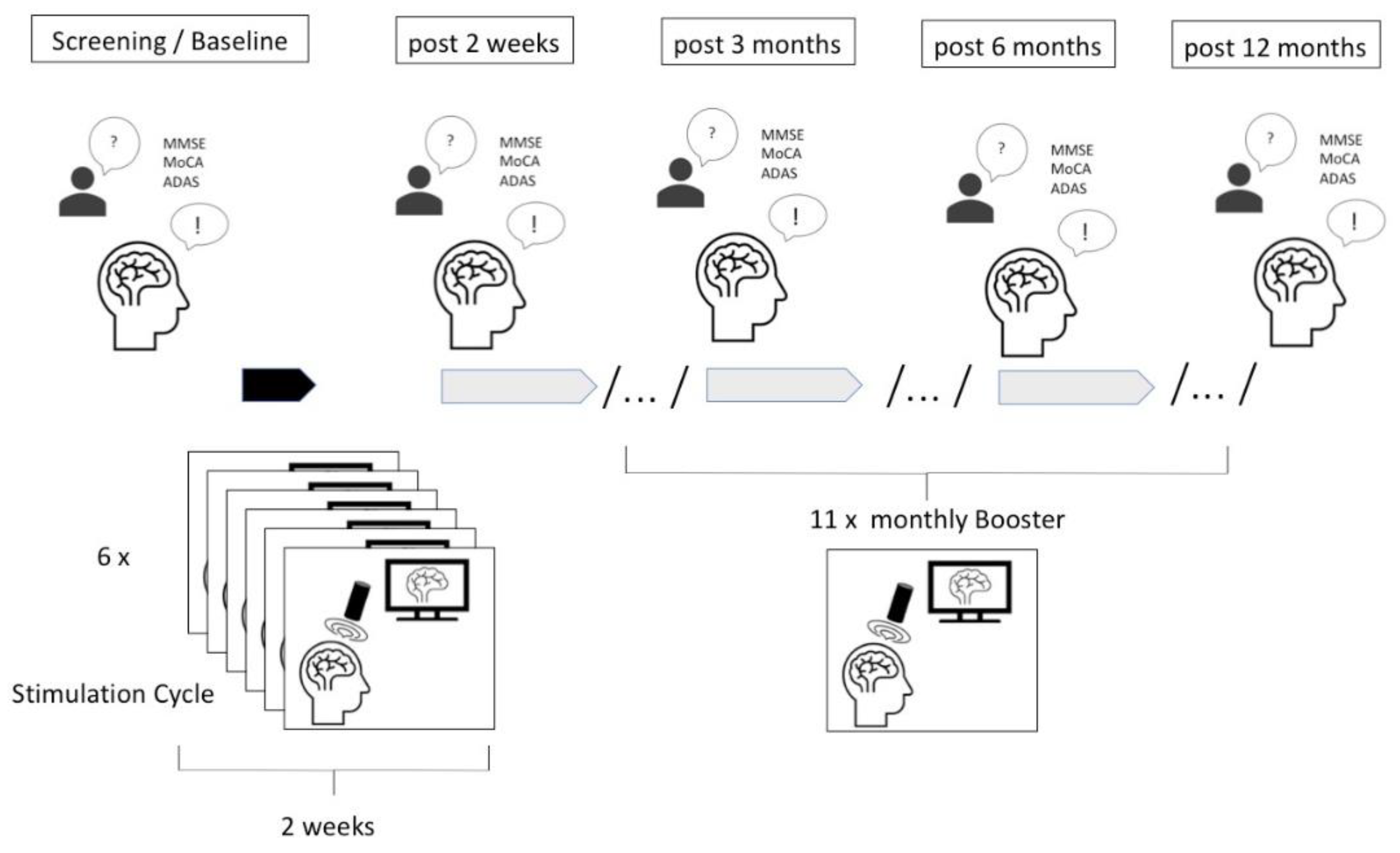

2 and targeting the bilateral frontal cortex, bilateral lateral parietal cortex, extended precuneus, and the bilateral temporal cortex. The TPS sessions were conducted over a period of 40 minutes, starting first with 6 initial sessions within two weeks every second day and then administered once a month with one session (see procedure in

Figure 2). For each session, 6000 pulses were applied. The procedure was carried out in accordance with the initial protocol and by trained professionals.

2.3. Adverse Device Events (ADE)

AEs were reported using a Numeric Rating Scale (NRS) asking for the severity with a 0 – 10 scale (with 10 being the highest intensity). The patient and/ or caregiver was asked before every treatment if any unintended medical occurrence happened after the last session and advised to inform the clinic if anything occurred within the next hours or days after the treatment. Some patients were admitted as an in-patient at the hospital for part of the stimulation, during which they were consistently monitored for side effects and closely observed. Causality of AE as ADE was judged by the principal investigator (LW) taking medical data into account.

2.4. Neuropsychological Assessment

Participants underwent comprehensive neuropsychological evaluations pre- and post-TPS treatment, as well as every 3, 6, and 12 months (each +/- 1 month). Standardized tests were used such as Minimental Status Examination (MMSE), Montreal Cognitive Assessment Test (MoCA), Alzheimer’s Disease Assessment Scale (ADAS) and its cognitive score (ADAS Cog). Moreover, the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI-II FS) was used to evaluate affective scores in some patients, which is a 21-question multiple-choice self-report scale that measures the severity of depression. The ADAS was used focusing on multiple cognitive domains:

Memory: Patients were presented with flashcards containing 10 words, which they were instructed to read aloud and memorize. Subsequently, they were prompted to recall the words they could remember (free reproduction). Following this, both new words and words from the initial list were presented, and patients were tasked with identifying the words they had previously learned (word recognition).

Visuoconstruction: The patients were provided with four distinct figures (circle, route, rectangles, cube), each increasing in complexity, and were instructed to draw them.

Orientation: Patients were asked regarding temporal and local orientation, including their first and last names, the date, the name of the hospital, and the city.

Language: Patients were assessed regarding their speech expression, speech comprehension, and word-finding disorder during the entire assessment. This score was the sole measure evaluated subjectively (observer biased).

2.5. Data Analysis

Quantitative analysis was conducted to compare pre- and post TPS treatment neuropsychological scores using one-sided t -tests calculated with alpha = 0.05 for significance to assess improvement after the first stimulation cycle. Changes in cognitive performance within each domain were assessed, and correlations and regressions between time and cognitive outcomes were explored to test a stable score over one year. Significance was established at p < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Hypothesis i) TPS Is Safe with Respect to Number and Severity of Adverse (Device) Events, A(D)E

In 187 sessions 9 AEs were reported with a subjective severity rating by the patient ranging from 1,5 -10 and a mean severity of M = 5.5 during the entire year of treatment (average treatment sessions were M = 18.7 over a year). Most of the AE were seen within the first stimulation cycle, where 6 sessions were conducted within two weeks every second day.

AE were either focal or systemic. The latter were either vigilance changes or behavioral fluctuations such as nervousness or aggressiveness. 7 of the AE were considered as clear ADE related to stimulation. 5 ADE occurred during stimulation including nervousness, feeling of pressure/slight pain on the head, pain in the jaw, and an unpleasant sensation on the head, and syncope and vomiting with hypotension. None of these ADEs lasted longer than the stimulation period.

4 AEs occurred after stimulation (somnolence with hyopotension after stimulation, aggressive behavior and vigilance fluctuations for 3 days, and dizziness for two hours after treatment) and were partly related to to stimulation (ADE) and partly to underlying medical conditions.

2 AE where severe and were at least possibly partly related to stimulation (ADE) and partly to underlying medical conditions. Careful medical evaluations, including EEG, ECG, echocardiography and CT, blood sugar, and blood pressure measurements identified hypertension as related medical conditions in severe A(D)E.

The first case was a patient (ID 3) who experienced a brief syncopal event during stimulation with accompanying hypotension and nausea, whereupon stimulation was terminated. Blood pressure was stable again a few hours later.

The second case (ID 4) was a patient with history of hypertension, COPD and right heart failure who already felt unwell before the stimulation. After medical consultation stimulation was performed, after which the patient appeared somnolent. Blood pressure was 100/60. The next day, the blood pressure was stable again.

Given that these two patients were already hospitalized, they could be consistently monitored as part of their ongoing care.

Summing up, hypothesis i) can be verified with respect to number of AE below 1% of treatment sessions. However, AE that at least have to be partly attributed causal related to stimulation as ADE can not only occur focally as pain or unpleasant sensation but also systemic as behavioral changes or vigilance changes especially in patients with underlying medical conditions.

Table 2.

Reported A(D)Es subjectively rated by the patient in brackets with the NRS (0 – 10, with 10 being highest severity) during the first stimulation cycle (6 sessions), the first 1 -3 months, during 3 – 6 months of the stimulation, and during 6 – 12 months. * Two AEs rated as severe both by the patient and the investigator occurred in two patients and were partly causal related to TPS (ADE) but partly related to underlying medical conditions.

Table 2.

Reported A(D)Es subjectively rated by the patient in brackets with the NRS (0 – 10, with 10 being highest severity) during the first stimulation cycle (6 sessions), the first 1 -3 months, during 3 – 6 months of the stimulation, and during 6 – 12 months. * Two AEs rated as severe both by the patient and the investigator occurred in two patients and were partly causal related to TPS (ADE) but partly related to underlying medical conditions.

| ID |

First stim. cycle |

1 - 3 mo. |

3 - 6 mo. |

6 - 12 mo. |

| 1 |

none |

none |

nervousness [1,4] |

none |

| 2 |

feeling of pressure/slight pain on the head during stimulation (2) |

none |

none |

none |

| 3 |

pain in the jaw (4) |

none |

none |

Syncope, vomiting during stimulation, combined with hypotension (10)* |

| 4 |

Somnolence after stimulation with hypotension (8-10)* |

none |

none |

3 days after stimulation aggressive behavior and vigilance fluctuations (6) |

| 5 |

none |

none |

none |

none |

| 6 |

none |

none |

none |

none |

| 7 |

none |

none |

none |

none |

| 8 |

none |

none |

none |

none |

| 9 |

none |

unpleasant focal sensation during stimulation (5) |

none |

none |

| 10 |

dizziness for two hours after stimulation (3) |

none |

none |

none |

3.2. Hypothesis ii) Cognitive Scores Improve After First Stimulation Cycle

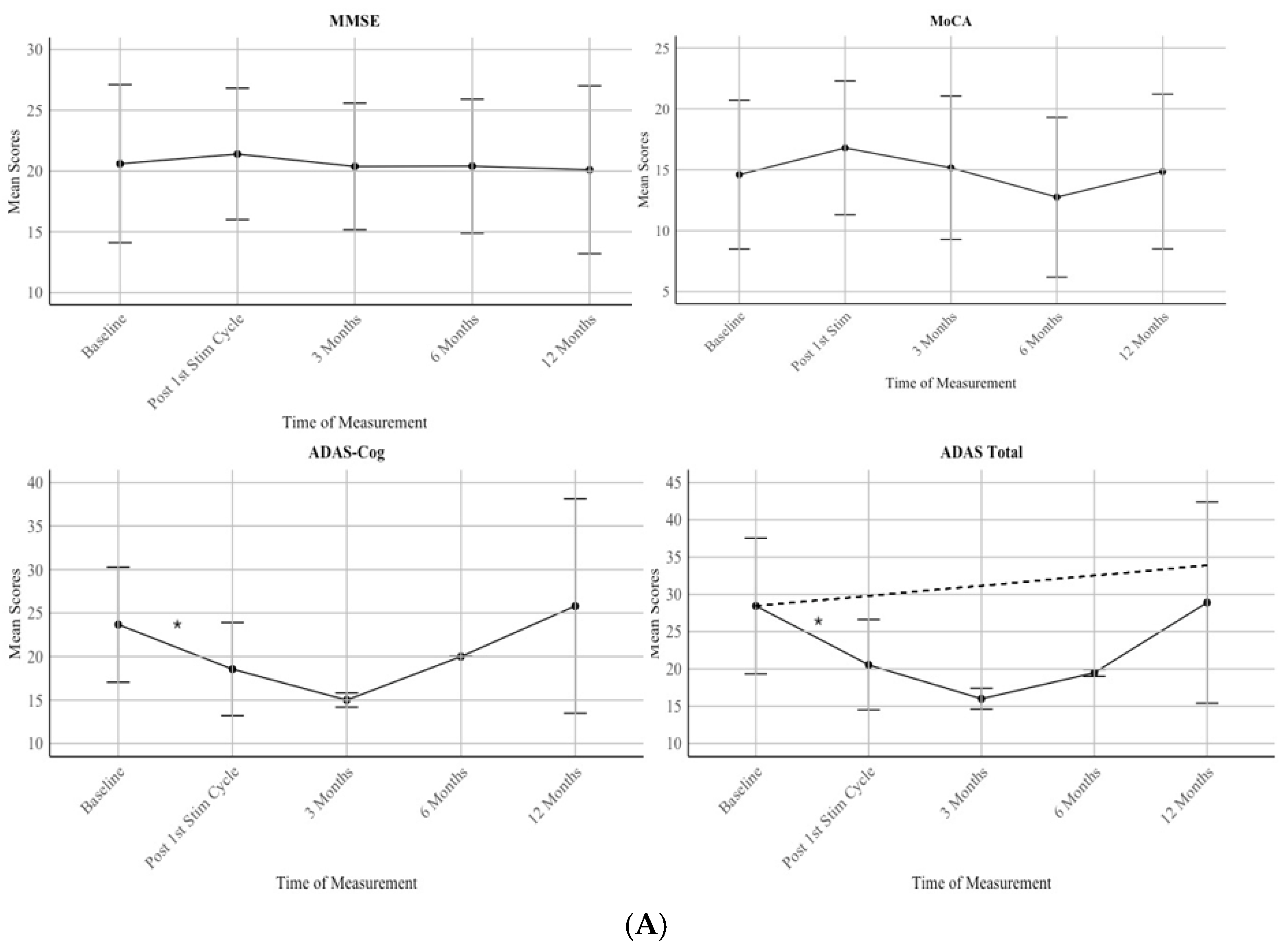

A significant difference between the baseline assessment and the post first stimulation cycle (6 sessions) can be seen used one-sided t-tests with alpha = 0.05: ADAS total: t(8) = 4.41 and p = .001 with d = 0.80, 95%-KI [0.36, 1.25] and for ADAS Cog t(8) = 4.23, and p = .001 with d = 0.75, 95%-KI [0.33, 1.18]. No significant improvement could be seen in MMSE with t(9) = -0.97, p = .82 with d = −0.11, 95%-KI [-0.36, 0.13] and in MoCA t(9) = -4.30 p = .99 with d = −0.33, 95%-KI [-0.50, -0.16], however both scores show an incline in mean scores with MMSE Mpre = 20.6 and Mpost = 21.4 and MoCA Mpre =14.6 and Mpost = 16.8.

Hypothesis ii) can be partly verified.

3.3. Hypothesis iii) Cognitive and Affective Scores Stay Stable After One Year of Treatment

Patients showed a stable score in all neuropsychological assessments during a one year period (MMSE: F(1) = .039, p = .843; R = 0.031; MoCA: F(1) = .031, p = .860; R = 0.030, ADAS Cog: F(1) = .167, p = .685; R = 0.073; ADAS: F(1) = .046, p = .832; R = 0.040) as shown in

Figure 3A. For the MMSE, scores increased following the first stimulation cycle. At Baseline, the mean score was 20.6 with a standard deviation (SD) of 6.50. After the first stimulation cycle, scores increased slightly to a mean of 21.4 (SD = 5.37). However, the scores returned to the baseline level at 3 months (M = 20.38, SD = 5.19) and remained stable at 6 months (M = 20.4, SD = 5.47) and 12 months, (M = 20.1, SD = 6.89).

For the MoCA, there was an initial improvement following the first stimulation cycle. The mean score at baseline was 14.6 (SD = 6.10), which increased to 16.8 (SD = 5.49) after

the first stimulation cycle and back to 15.16 (SD = 5.87) at 3 months. However, scores then declined to 12.75 (SD = 6.56) at 6 months before increasing back to baseline score at M = 14.86 (SD = 6.34) at 12 months.

For the ADAS Cognitive, scores improved after the first stimulation cycle, with the mean score at baseline being 23.67 (SD = 6.62) and post first stimulation cycle M = 18.56 (SD = 5.36) and further decreased to 15.0 (SD = 0.82) at 3 Months. However, there was a notable increase in scores at 6 Months (M = 20.0, SD = 0.00) and 12 Months (M = 25.8, SD = 12.33).

For the ADAS Total, scores decreased from baseline (M = 28.44, SD = 9.09) to 3 Months (M = 16.0, SD = 1.41). However, scores increased again at 6 months (M = 19.5, SD = 0.47) and further rose around baseline level at 12 months (M = 28.9, SD = 13.49).

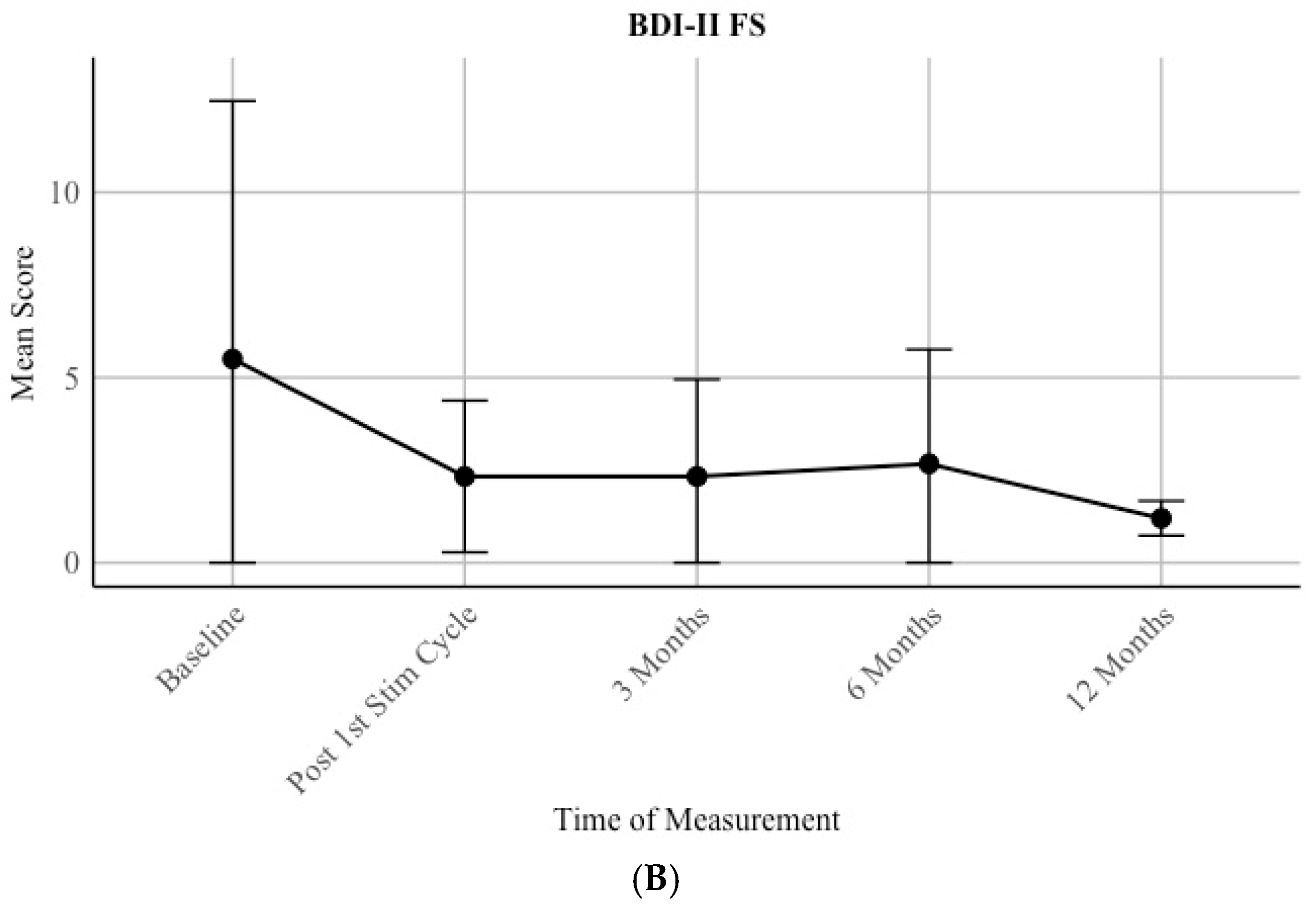

Moreover, a trend of a decrease in depressive scores can be seen by assessing the mean scores by the patients for over a year (

Figure 3B). Due to underpower, only mean scores are reported, and no statistical analysis was conducted. Before the first stimulation, the group of patients show a mean score of 5.5 (SD = 6.97) and after a year a mean score of 1.2 (0.47).

Hypothesis iii) can be verified. Additionally, improvement in depression was detected on a descriptive level.

3.4. Hypothesis iv: A stronger Effect Can Be Seen in Memory and Speech Compared to Visuo-Construction Due to the Targeted Neuroanatomical Treatment Areas

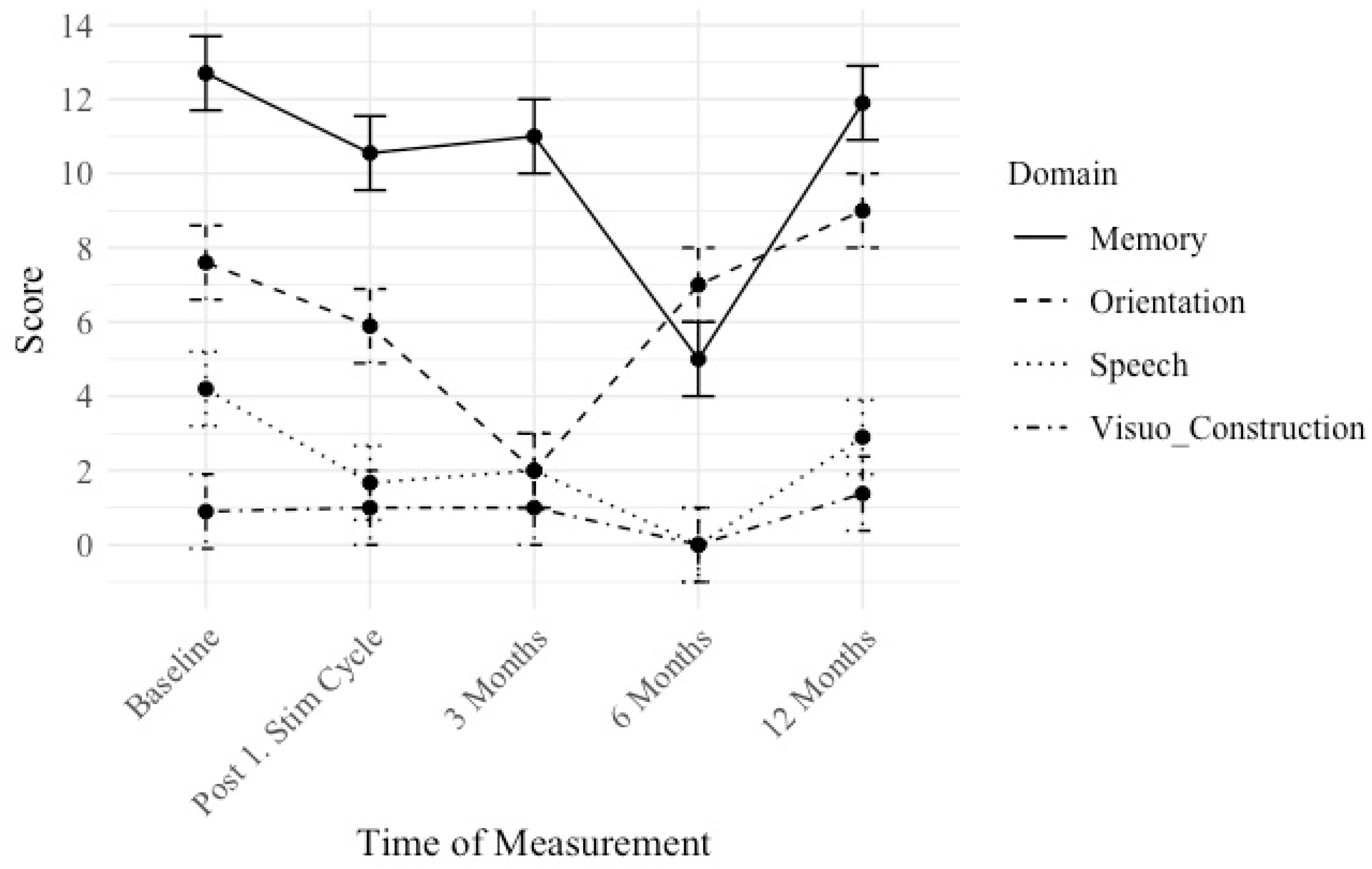

We conducted longitudinal cognitive assessments to examine changes over time in distinct cognitive domains: memory, orientation, speech, and visuoconstruction measured by the ADAS test. Lower scores indicate a better performance. The mean scores and standard deviations for each cognitive domain were computed at distinct time intervals: Baseline, Post 1. Stim Cycle, 3 Months, 6 Months, and 12 Months (see

Figure 4).

Scores are reported in a descriptive quantitative matter.

For memory, a reduction in mean scores was observed over time. Initially, participants scored 12.7 (SD = 4.58) at baseline, which decreased to 10.55 (SD = 4.27) following the first stimulation cycle. At the 3-month mark, scores slightly increased to 11 (SD = 1). By the 12-month follow-up, mean scores raised to 11.9 (SD = 5.84).

For orientation, initially, participants scored 7.6 (SD = 6.63) at baseline, which decreased to 5.89 (SD = 4.46) post-stimulation cycle. At the 3-month evaluation, scores dropped to 2 (SD = 0). At the 12-month mean scores went up to 9 (SD = 6.99).

Regarding speech, an improvement, and therefore deduction in mean scores was observed initially (baseline 4.2 (SD = 2.6)), which went to 1.67 (SD = 2.31) post-stimulation cycle. At 3 months, scores remained stable at 2 (SD = 1.5), then decreased to 0 (SD = 0) at 6 months. At the 12-month follow-up, mean scores were rising to 2.9 (SD = 3.53).

For visuoconstruction, patients scored 0.9 (SD = 1.22) at baseline, which remained relatively stable post-stimulation cycle (1 (SD = 0.94)) and at 3 months (1 (SD = 0.47)), then changed to 0 (SD = 0.87) at 6 months. Nonetheless, at the 12-month assessment mean scores were rising to 1.38 (SD = 1.86).

Summing up, hypothesis iv) can be verified at least on a descriptive level, although these improvements cannot be statistically verified.

3.5. Additional Post-Hoc Analysis

To better understand the characteristics and potential reasons for patient dropout, we conducted a focused post hoc- analysis on the largest subgroup of participants lost to follow-up, which consisted of those who discontinued the study shortly after the initial stimulation cycle (N=10) (see

Figure 1). Given that this was the most substantial group within our attrition data, we aimed to examine whether their early discontinuation was associated with a lack of treatment effect and/or specific adverse events.

Therefore, we performed a one-sided t-test on the MMSE scores of this group. The analysis yielded a statistically significant result: t(7) = -2.76, p = .014, indicating a significant improvement in this subset of patients.

To further investigate potential reasons for patient dropout, we analyzed the occurrence of adverse events within the loss to follow-up group after the first stimulation cycle (N=10). Our analysis revealed that only one patient (10%) reported an adverse event (eye twitching after stimulation). However, this patient was unable to rate the severity of the event using the Numerical Rating Scale (NRS). Considering that each patient received six stimulation sessions, the reported adverse event occurred in only one out of 60 sessions, corresponding to 1.67% of all treatment sessions.

4. Discussion

In this paper we address safety, feasibility, and long-term effects of TPS in Alzheimer’s. We consider TPS treatment as safe with only transient AE below 1% of the stimulation sessions.

However, AE that at least have to be partly attributed causal related to stimulation as ADE can not only occur focally as pain or unpleasant sensation but also systemic as behavioral changes or vigilance changes especially in patients with underlying medical conditions. Vasodepressor (neurocardiogenic) syncope is a frequent response to anxiety and psycho-physical discomfort. It’s a commonly encountered phenomenon that was observed during TMS treatment [

15]. Visceral discomfort, nausea, dizziness, and pallor are symptoms that were also observed in our data. Therefore, these events were considered at least partly as device related. Thus, we suggest that treatment centers should ensure that a patient couch is available in the treatment room so that the patient can be stabilized immediately in case of syncope. In addition, blood pressure test, lab tests, CT, ECG and EGG should be available so that a differential diagnosis can be made quickly.

A(D)Es mostly occurred within the period of the highest intensity of treatment within the first stimulation cycle, where 6 sessions were applied within two weeks. This goes along with fact the most improvement in cognition was seen within this two-week period.

Initially, 35 patients started TPS treatment. However, there was a large loss of follow up. To better understand potential reasons for patient dropout, we conducted post hoc analyses on the largest loss to follow-up subgroup. Our findings show that this group still exhibited a significant effect in MMSE scores, suggesting that their discontinuation was not primarily due to a lack of treatment effect. Additionally, adverse events were rare, with only one patient (10%) reporting a mild, non-quantifiable adverse event (eye twitching), corresponding to just 1.67% of all treatment sessions. Given these results, we believe that other external factors, unrelated to treatment efficacy or safety, may have contributed to patient attrition. There are several reasons why some patients with Alzheimer’s disease do not continue the treatment with Transcranial Pulse Stimulation. Logistical aspects, such as the need for regular visits to specialized centers, can be challenging for patients and caregivers, especially when transportation or mobility is limited. Recruitment of participants is another critical factor, as Alzheimer’s patients and their families may be hesitant to continue to participate due to concerns about the novelty of the intervention or uncertainty regarding its long-term efficacy. Additionally, acceptance of the intervention can vary; some patients may not perceive the expected benefits from the treatment, leading to frustration or loss of motivation to continue. Finally, the feasibility of TPS may be challenging for Alzheimer’s patients due to the method’s requirements. Session duration and frequency might be overwhelming for individuals with cognitive limitations, such as difficulty sitting still, tolerating the noise of the device, and following schedules. These challenges underline the importance of tailoring TPS protocols and addressing patient-specific needs to improve adherence and overall treatment outcomes.

A general improvement in neuropsychological test scores could be seen after the first stimulation cycle with 6 initial sessions, with a significant improvement tested in ADAS and ADAS cognitive score. No significance could be seen in the MMSE and MoCA score, which might be caused by the lower sensitivity for mild to moderate affected patients [

16].

One could conclude that stimulation should be conducted with higher frequency over the long-term period. However, due to practical reasons only booster sessions once monthly were done. This report confirms that Alzheimer patients treated regularly with that scheme show a stable score over a year of treatment.

Moreover, on a descriptive level the data suggest that a slight improvement over time can be expected in memory, speech, and mood over time. This relates to brain areas that have been targeted with most stimulation pulses.

Potential limitations of this paper included the small sample size, lack of a control group, and variations in disease progression among participants.

Over the course of a year, patients maintained a consistent ADAS score, which represents a positive outcome given the progressive nature of the disease. Generally, a disease progression meta-analysis for Alzheimer’s Disease showed that a worsening by 5 points in the ADAS score can be expected over a year [

7]. Thus, we conclude that patients benefit from TPS as an add-on therapy.

One could argue that TPS effects on metabolism are more global and not target specific. However, technically TPS can be used highly focal by the use of neuronaviagtion. For the focal approach, it should be considered targeting the exact anatomical areas where patients show deficits. A study showed that sparing out stimulation areas that are essential for visuoconstruction, these functions declined in a neuropsychological test [

5], which is also presented by our findings. Thus, specific targeting makes sense and one could concentrate on specific symptoms patients want to improve including memory, speech, visuoconstruction, and orientation.

For a general protocol in AD, the number of pulses in the targeted regions should be adjusted to the protocol used to date. To see an effect in all cognitive domains that are affected by AD, we suggest that the protocol should be changed in the following way: Additional to the bilateral frontal lobe, bilateral parietal lobe, bilateral temporal lobe, and precuneus, the occipital lobe should also be targeted to enhance visoconstructive functions. Neuronavigation should be improved technically to visualize distinct deeper temporal areas of the hippocampus to improve memory and orientation. Consequently, this augmented protocol is proposed to be termed F-TOP2 (Frontal-Temporal-Occipital-Parietal-Precuneus) and could have an overall effect.

Figure 4.

Proposed multifocal stimulation approach according the F-TOP2 scheme. Number of pulse delivered by the navigated TPS application to the following areas: (F)rontal 1000 each hemisphere, (T)emporal 600 each hemisphere, (O)ccipital 400 each hemisphere ,(P)arietal 600 each hemisphere and (P)recuneus midline 800.

Figure 4.

Proposed multifocal stimulation approach according the F-TOP2 scheme. Number of pulse delivered by the navigated TPS application to the following areas: (F)rontal 1000 each hemisphere, (T)emporal 600 each hemisphere, (O)ccipital 400 each hemisphere ,(P)arietal 600 each hemisphere and (P)recuneus midline 800.

Furthermore, as discussed in the introduction, the underlining effects of TPS are still not discovered. This paper shows a deduction of depressive symptoms, and three other studies could also show this effect [

3,

6]. Improvement in Alzheimer’s cognitive symptoms through the application of TPS may be attributed to its mood-enhancing effects, as heightened mood can lead to various benefits in managing the condition. Therefore, a global or as here proposed, a multifocal stimulation approach including wide areas of the frontal cortex seems plausible. Elevated mood can potentially enhance cognitive function and memory retention, reduce stress and anxiety levels, promote better sleep quality, increase engagement in social interactions and activities, and improve overall quality of life for individuals with Alzheimer’s disease. These factors collectively contribute to a more favorable environment for managing and alleviating Alzheimer’s symptoms.

Therefore, the effects of TPS need to be further investigated so the most beneficial treatment protocol for patients with Alzheimer’s can be developed.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.C.-R. and L.W.; methodology, C.C.-R.; validation, C.C.-R. and L.W.; formal analysis, C.C.-R.; investigation, C.C.-R., N.S., A.G., and C.S.; data curation, N.S., A.G., and C.S.; writing—original draft preparation, C.C.-R.; writing—review and editing, C.C.-R. and L.W.; visualization, C.C.-R.; supervision, L.W.; project administration, C.C.-R.; funding acquisition, L.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors received funding from Storz Medical (Tägerwilen, Switzerland) for payment of publication fee. The funder was not involved in the study design, collection, analysis, interpretation of data, the writing of this article or the decision to submit it for publication.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of the regional Medical Chamber (Ärztekammer Nordrhein, Nr. 2021026) as part of a local registry.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

Technical assistance and data collection in preparation of this article was provided by Veronika Hirsch and Michaela Wessler (medical technical assistants). Furthermore, we like to thank all the patients who participated in the study and entrusted us with their care, demonstrating unwavering commitment by continuing their treatment for over a year with us.

Conflicts of Interest

Nathalie Stute, Anastasia Galli, and Christina Schulte declare that they have no competing interests. Celine Cont was consultant for Storz Medical. Lars Wojtecki has previously received funding grants and institutional support from the German Research Foundation, Hilde-Ulrichs Stiftung für Parkinsonforschung, and the ParkinsonFonds Germany, BMBF/ERA-NETNEURON, DFG Forschergruppe (FOR1328), Deutsche Parkinson Vereinigung (DPV), Forschungskommission, Medizinische Fakultät, HHU Düsseldorf, Medtronic, UCB, Teva, Allergan, Merz, Abbvie, Roche, Bial, Merck, Novartis, Spectrum. Esteve, Storz Medcial, Argenx, Alexion, Eisai, Biogen, Desitin, Stada, Zambon, LW is consultant to the following companies or received travel honarium from: TEVA, UCB Schwarz, Desitin, Medtronic, Abbott/Abbvie, MEDA, Boehringer I, Storz Medical, Kyowa Kirin, Guidepoint, Merck, Merz, Synergia, BIAL, Zambon, Sapio Life, STADA, Inomed, Vertanical, Synaptikon, Magventure.

References

- Breijyeh, Z.; Karaman, R. Comprehensive Review on Alzheimer’s Disease: Causes and Treatment. Molecules 2020, 25, 5745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beisteiner, R.; Matt, E.; Fan, C.; Baldysiak, H.; Schönfeld, M.; Philippi Novak, T.; et al. Transcranial Pulse Stimulation with Ultrasound in Alzheimer’s Disease—A New Navigated Focal Brain Therapy. Adv. Sci. 2020, 7, 1902583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cont, C.; Stute, N.; Galli, A.; Schulte, C.; Logmin, K.; Trenado, C.; et al. Retrospective Real-World Pilot Data on Transcranial Pulse Stimulation in Mild to Severe Alzheimer’s Patients. Front. Neurol. 2022, 13, 948204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Popescu, T.; Pernet, C.; Beisteiner, R. Transcranial Ultrasound Pulse Stimulation Reduces Cortical Atrophy in Alzheimer’s Patients: A Follow-Up Study. Alzheimers Dement. (N Y) 2021, 7, e12121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dörl, G.; Matt, E.; Beisteiner, R. Functional Specificity of TPS Brain Stimulation Effects in Patients with Alzheimer’s Disease: A Follow-Up fMRI Analysis. Neurol. Ther. 2022, 11, 1391–1398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matt, E.; Dörl, G.; Beisteiner, R. Transcranial Pulse Stimulation (TPS) Improves Depression in AD Patients on State-of-the-Art Treatment. Alzheimers Dement. (N Y) 2022, 8, e12245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ito, K.; Ahadieh, S.; Corrigan, B.; French, J.; Fullerton, T.; Tensfeldt, T.; et al. Disease Progression Meta-Analysis Model in Alzheimer’s Disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2010, 6, 39–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koch, G.; Casula, E.P.; Bonnì, S.; Borghi, I.; Assogna, M.; Minei, M.; et al. Precuneus Magnetic Stimulation for Alzheimer’s Disease: A Randomized, Sham-Controlled Trial. Brain 2022, 145, 3776–3786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strom, A.; Iaccarino, L.; Edwards, L.; Lesman-Segev, O.H.; Soleimani-Meigooni, D.N.; Pham, J.; et al. Cortical Hypometabolism Reflects Local Atrophy and Tau Pathology in Symptomatic Alzheimer’s Disease. Brain 2022, 145, 713–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, D.T.; Graff-Radford, J. Executive Dysfunction and the Prefrontal Cortex. Continuum (Minneap Minn) 2021, 27, 1586–1601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berron, D.; Vogel, J.W.; Insel, P.S.; Pereira, J.B.; Xie, L.; Wisse, L.E.M.; et al. Early Stages of Tau Pathology and Its Associations with Functional Connectivity, Atrophy and Memory. Brain 2021, 144, 2771–2783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sperling, R.A.; Aisen, P.S.; Beckett, L.A.; Bennett, D.A.; Craft, S.; Fagan, A.M.; et al. Toward Defining the Preclinical Stages of Alzheimer’s Disease: Recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association Workgroups on Diagnostic Guidelines for Alzheimer’s Disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2011, 7, 280–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blenkinsop, A.; van der Flier, W.M.; Wolk, D.; Lehmann, M.; Howard, R.; Frost, C.; et al. Non-Memory Cognitive Symptom Development in Alzheimer’s Disease. Eur. J. Neurol. 2020, 27, 995–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jack, C.R. Jr.; Bennett, D.A.; Blennow, K.; Carrillo, M.C.; Dunn, B.; Haeberlein, S.B.; et al. NIA-AA Research Framework: Toward a Biological Definition of Alzheimer’s Disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2018, 14, 535–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rossi, S.; Hallett, M.; Rossini, P.M.; Pascual-Leone, A. Safety, Ethical Considerations, and Application Guidelines for the Use of Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation in Clinical Practice and Research. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2009, 120, 2008–2039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tombaugh, T.N.; McIntyre, N.J. The Mini-Mental State Examination: A Comprehensive Review. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 1992, 40, 922–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).