1. Introduction

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a complex neurological disease characterized by immune-mediated demyelination of the central nervous system [

1]. This intricate pathology gives rise to a wide range of symptoms, including fatigue and cognitive impairments, which pose a particular challenge for People living with MS (PwMS) [

2]. Fatigue in MS is a debilitating symptom for more than 80% of PwMS[

3], while cognitive impairments in domains including memory, attention, problem-solving, and information processing [

2] are estimated to be present in 40-65% of PwMS [

4].

The relationship between fatigue and cognition in MS reveals a complex interplay, with literature showing conflicting results. Whereas several investigations have failed to uncover a significant relation between self-reported fatigue and objective cognitive test performance, others report that fatigue is linked to cognitive function [

8]. The mechanisms underlying the intricate interaction are multifaceted. In particular, fatigue-related processes may directly impact neural networks involved in cognition, leading to cognitive impairments. Conversely, cognitive dysfunction can contribute to increased mental effort and inefficient use of cognitive resources, resulting in heightened fatigue [

5]. The symptom of fatigue has remained rather obscure until more recently, and its knowledge will improve the ability to uncover the specific interdependence with cognitive impairment. Recent investigations have started revealing that fatigue predicted cognition in MS patients only, beyond anxiety-depressive symptoms and disease progression. These signs highlight the relevance of considering the multidimensional nature of fatigue, possibly revealing fatigue as a predictor of different cognitive processes [

6].

Although future advancements will clarify the specificity and interplay of fatigue and cognitive dysfunctions, it is quite clear that both have a significant detrimental effect on work status [

7], daily activities, and independence [

8], as well as overall quality of life [

9,

10].

While there have been pharmacological interventions aiming to manage cognitive impairment and fatigue, their efficacy has been inconsistent, with frequent side effects [

11,

12]. In obtaining comprehensive care for cognitively impaired and fatigued PwMS, non-pharmacological and neuro-behavioral therapies are in development. Cognitive rehabilitation has demonstrated positive effects on cognitive performance [

13,

14] with observed fatigue relief as well [

15].

Considering the structural and functional characteristics of the pathology, functional damage related to the symptom of fatigue, in the absence of revealable structural alterations of the affected regions, lays the basis for an innovative therapeutic approach with the use of neuromodulation that allows to directly influence the dynamics and excitability of neural networks [

16]. A recent review of 49 studies involving 944 PwMS [

17] showed that non-invasive brain stimulation is potentially relevant to mitigate fatigue, with a clear advantage of transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) over repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS).

Moreover, the neurophysiological counterpart of neuro-behavioral therapies reveals an adaptation linked to cerebral neuroplasticity mechanisms, whereby increasing intra- and inter-hemispheric functional connectivity stimulates the areas and networks actively involved in the various domains of cognition [

18]. Thus, a recent systematic review and meta-analysis [

19] revealed that tDCS has a favorable effect on cognitive processing speed and fatigue in MS. However, the effects on cognition and fatigue vary based on the specific assessment used.

This study aims to set up a multimodal and personalized intervention for cognitive rehabilitation and alleviation of fatigue in PwMS. By a multiple baseline across subjects Single-Case Experimental Design (mbSCED) [

20], we assessed the feasibility, efficacy, and acceptance from all stakeholders of a cognitive rehabilitation protocol enriched with neuromodulation. We considered the double measure of cognitive performance and fatigue level as an outcome.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

The current study, as seed above, employed the mbSCED, which is a n-of-1 trial; these investigations treat an individual patient as the sole unit of observation in a study, to pursue and attain the best treatment for each person [

21]. SCED, in particular, is a set of experimental methods that can be used to test the efficacy of an intervention on a small number of people (typically one to three), involving repeated measurements, sequential (randomized) introduction of an intervention, and specific data analysis and statistics [

20]. The SCED protocol was chosen primarily because it allows for high-quality research with a small number of participants. Moreover, SCEDs evaluate the effects of an intervention on people individually, which is an important feature for MS, given that the disease could affect any part of the central nervous system; thus, people’s clinical profiles are often diverse, and each PwMS is unique with distinct characteristics [

22].

The mbSCED [

20], with replication across participants, focused on fatigue relief enrichment through a well-standardized cognitive rehabilitation protocol. According to this proposal, the intervention is introduced sequentially to different participants, and at least 3 subjects are needed. All participants begin the intervention with a baseline phase (i.e. without any intervention), during which the target variable (i.e. fatigue) is measured repeatedly for each patient, until one of the participants starts the intervention, while the others continue without intervention, all participants still being measured repetitively on the target variable. Moreover, each subject follows a simple design, in which different components of an intervention (i.e. tDCS and cognitive rehabilitation via software) are tested separately or introduced sequentially (to explore their cumulative effect) to each patient.

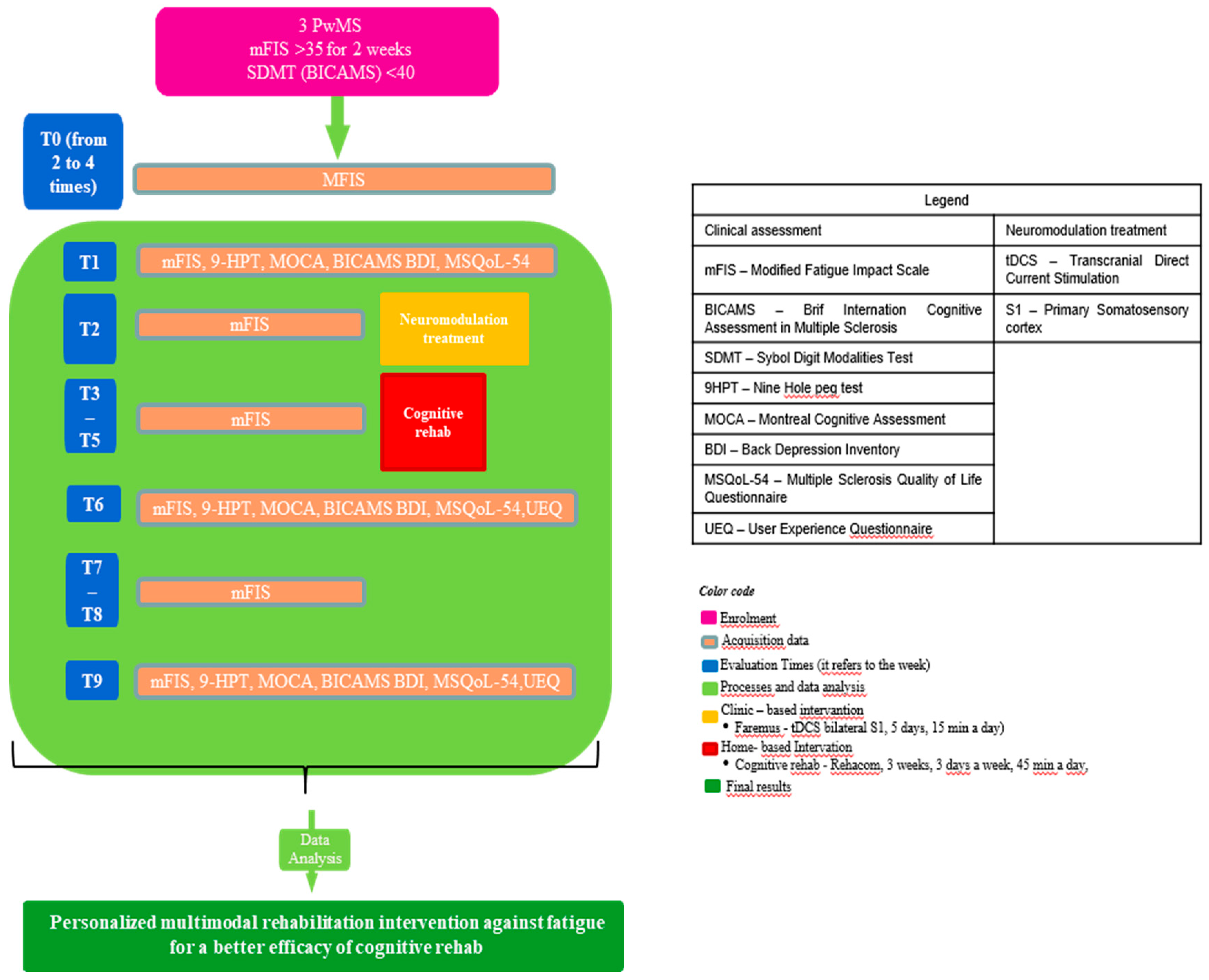

Therefore, each PwMS started with a non-intervention baseline phase, during which the fatigue level was measured repeatedly for at least two weeks through the modified Fatigue Impact Scale (mFIS). After the baseline phase, the first enrolled person underwent the basic neuropsychological evaluation at the Neurocare Centre in Ioannina, and the following week the multimodal treatment began. This treatment lasted four weeks; the first week consisted solely of neuromodulation, while the next three focused only on cognitive rehabilitation. tDCS was held in a bright, quiet room of the Neurocare clinic, whereas cognitive rehabilitation was performed in the participants’ homes. The fatigue was monitored weekly for the entire duration of the protocol. The week after the end of the multimodal intervention, as well as three weeks later, participant n.1 underwent a neuropsychological evaluation at the clinic. The same process was repeated for the second PwMS with a week delay, resulting in three weeks of baseline, and finally for the third the following week, with 4 weeks of baseline (

Figure 1).

2.2. Participants

GN, the neurologist, identified 15 PwMS previously diagnosed with Relapsing-Remitting MS according to McDonald's criteria [

23,

24]; 10 of them reported fatigue and cognitive deficits. From this cohort, 3 were randomly recruited for the project via randomizer.org software [

25]. Eligibility criteria included: age (between 21 and 60 years old), level of education (of at least 6 years), Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS) score (between 0-5), fatigue (measured via mFIS>35 at least two times with a week interval [

26]), cognitive deficit (measured via Symbol Digit Modality Test (SDMT) <40 [

27]), being a native speaker of the Greek language, and normal hearing and vision normal or correct to normality. The exclusion criteria were as follows: relapse in the last 3 months, cognitive rehabilitation or specific interventions against fatigue in the last 3 months, psychiatric disorders, drug or alcohol abuse, pregnancy (confirmed or presumed), other neurological disorders or clinical history of (e.g., epilepsy), and intracranial metal implants.

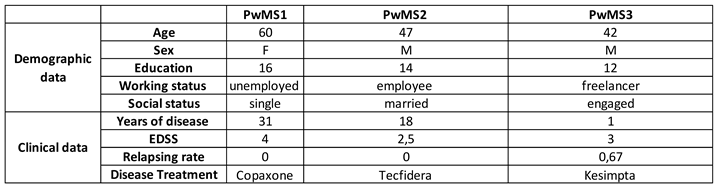

The study was conducted following the Declaration of Helsinki ethical principles. The ethics committee of the University of Ioannina approved the study protocol (Reference number 7047/29-02-2024). All participants were informed of the nature of the study and provided written consent for their participation. Participants were notified they could drop out of the study at any time as they wished, without any impact on their medical treatment. The profile of the study participants is presented in

Table 1.

2.3. Procedure

Two PhD students (TL, NKD) and a Bachelor student (KS), trained for the uniform administration of tests, neuromodulation, and RehaCom rehabilitation, conducted the protocol in a home-clinical setting under expert supervision (FT and GN).

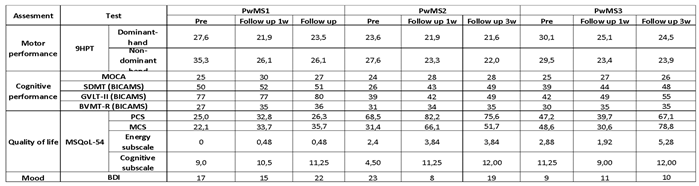

The protocol included three assessments. These were planned at pre-intervention, 1-week post-intervention, and at 3-week follow-ups, after which they were involved in the evaluation of motor and cognitive performance via objective measures. In particular, the 9-Hole Peg Test (9HPT) [

28] was used to assess fine manual performance. Fatigue, mood, quality of life, and user experience were evaluated with self-reported measures. Cognitive assessment was conducted with the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) [

29] and the Brief International Cognitive Assessment in MS (BICAMS), which includes the SDMT [

30], the Greek Verbal Learning Test-II (GVLT-II) [

31], and the Brief Visuospatial Memory Test-Revised (BVMT-R) [

32]. Fatigue was monitored via Google form weekly using the mFIS [

33]. Furthermore, depression was evaluated with the Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II) [

34], and quality of life was assessed with the Greek MS Quality of Life Questionnaire (MSQoL-54) [

35,

36]. Finally, user experience was rated by both PwMS and therapists with the User Experience Questionnaire (UEQ) [

37], considering classical usability aspects (efficiency, perspicuity, dependability) and user experience aspects (originality, stimulation).

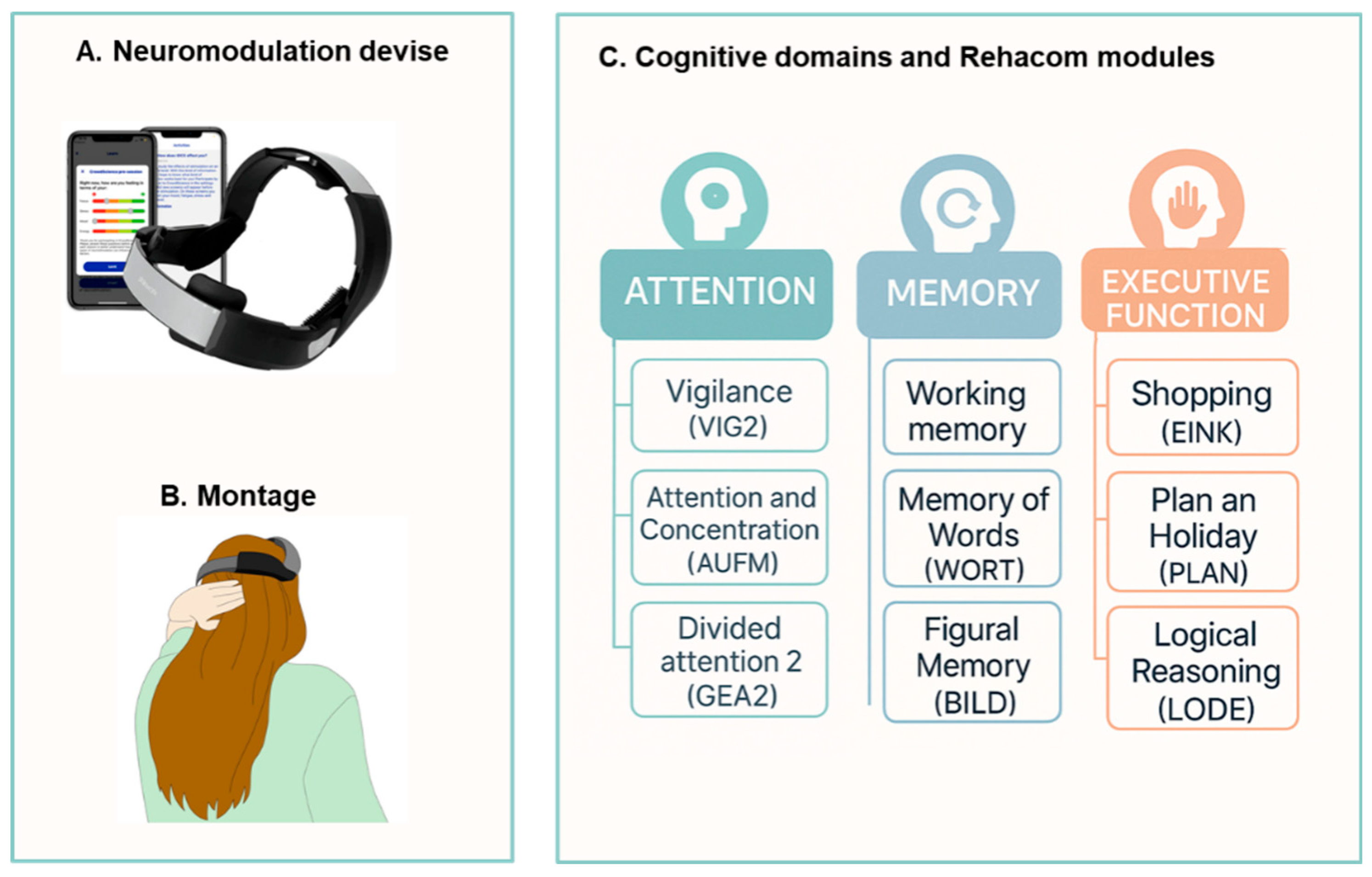

The neuromodulation for fatigue was carried out in the first week after the baseline phase, using a commercialized wireless tDCS cap (Platowork, Platoscience, Denmark). Based on the literature [

38,

39], the stimulation protocol consisted of five sessions, held on 5 consecutive days, 15 minutes a day, with an intensity of 1.5 mA (

Figure 2 A, B). Cognitive rehabilitation began the following week, lasting three weeks, three days a week, for 45 minutes a day, utilizing RehaCom® software; this training program has demonstrated a beneficial effect on cognitive functions in PwMS [

40]. The cognitive domains stimulated were attention, memory, and executive functions. In each session, PwMS performed 3 different exercises (15 minutes per exercise) that stimulated specific processes of the mentioned domains (

Figure 2C). The order of the exercises was randomized among the participants via randomizer.org. All participants started from the simplest level of difficulty, which progressively increased, determined by the software based on the participant's average performance in that specific exercise (see supplementary materials).

2.4. Statistical Analysis

The analysis followed a multidimensional approach to assess the feasibility, efficacy, and acceptability of the intervention and involved visual inspection of the level, trend, and variability between phases [

41]. The data were analyzed using

https://manolov.shinyapps.io software as well as Microsoft Excel 2016.

Feasibility: A qualitative analysis of feedback received at the end of the protocol was conducted, and dropouts were evaluated.

Individual responsiveness: For all the tests, we used the Minimal Clinically Important Difference, defined as the smallest change in scores that identified the PwMs as a responder [

43]. Participants were considered responsive to the tDCS intervention if they showed a change of >20% of the baseline level. For the tests, participants were considered responders if they showed a change of >20% in the 9HPT [

42], a change ranging [2.9-5] points in BICAMS [

43], MoCA [

44] and BDI-II [

45]; and a change of 10-points in the MSQoL-54 [

36].

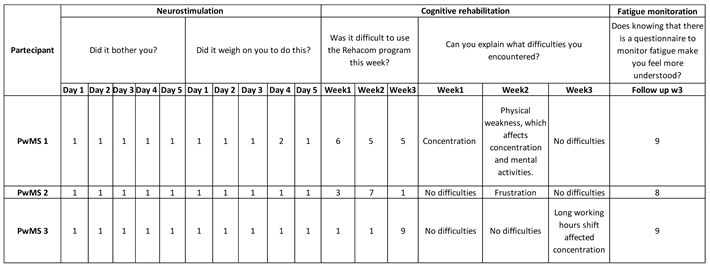

Acceptability: For qualitative analysis, daily during neuromodulation and weekly during cognitive rehabilitation, participants answered the questions:

"Did it bother you?", and

"Was it difficult to use the tDCS/RehaCom program this week?” on a Likert Scale of 1 to 10 (1=Not at all, 10=Very much). Furthermore, a User Experience Questionnaire was administered [

37] .

3. Results

3.1. Feasibility

All PwMS completed the multimodal intervention with no dropouts. TL and NKD maintained constant contact with participants via email or telephone throughout the project, fostering a supportive relationship.

3.2. PwMS n.1

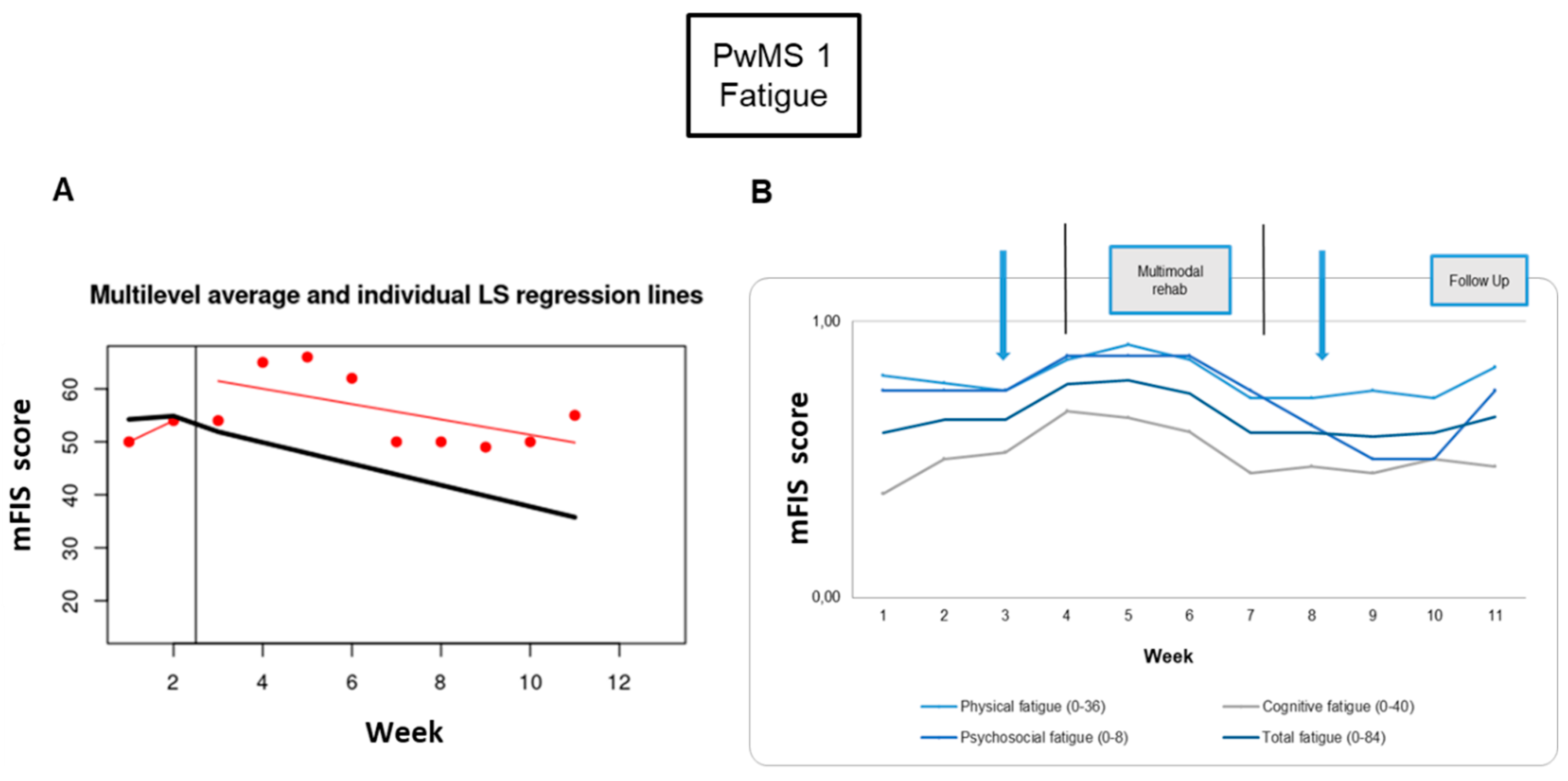

3.2.1. Individual Responsiveness

Fatigue: The fatigue symptom monitoring showed a worsening at the end of the tDCS intervention (23%) and a mitigation at the end of the RehaCom rehabilitation period (-23%), which disappeared at the 1-week and 3-week follow-ups (

Table 2). Looking at the behavior of fatigue symptom, there is a worsening during the four weeks of intervention (

Figure 3).

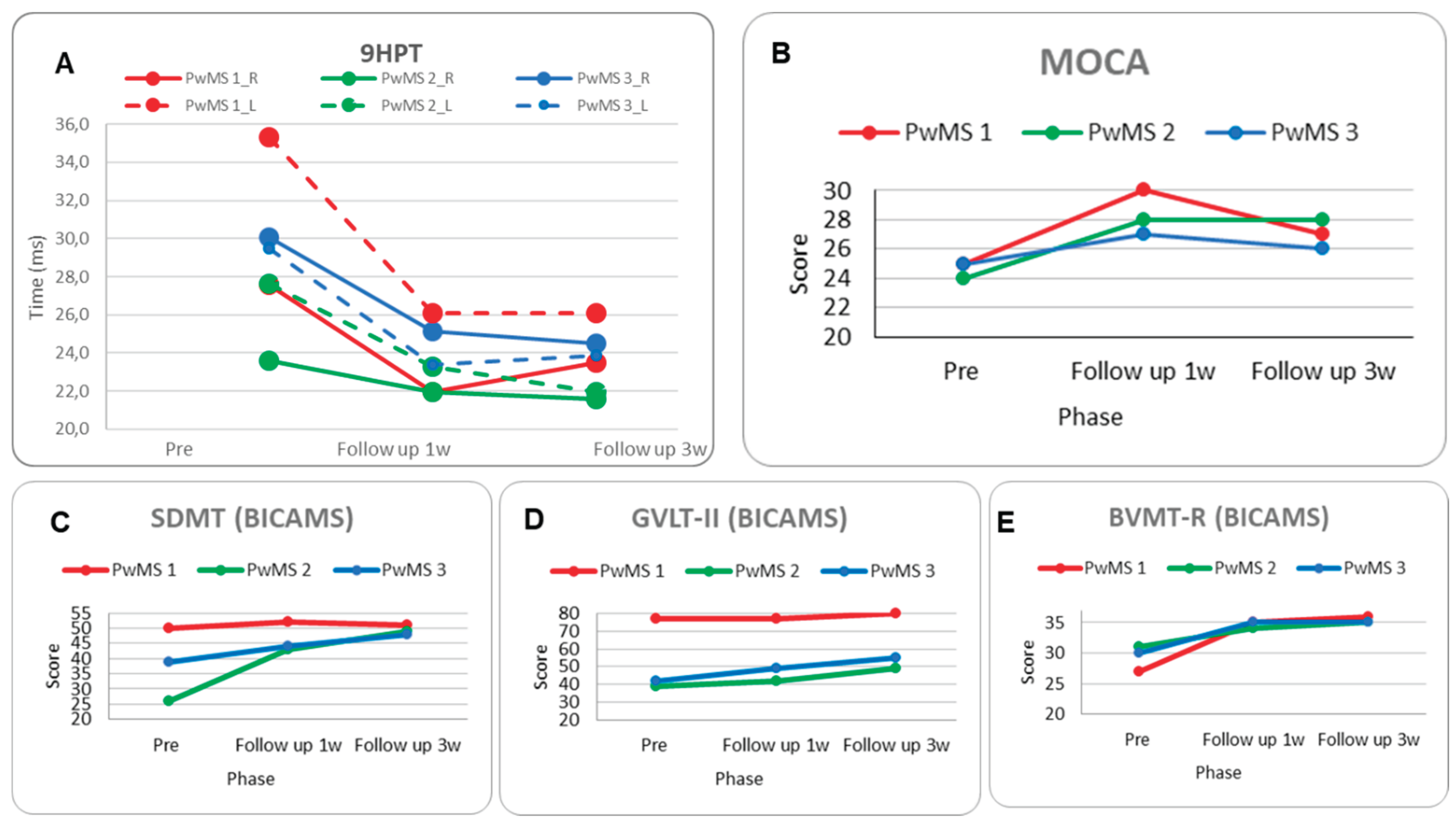

Neuro-psycho-motor assessment: Motor performance on the 9HPT improved in the 1-week follow-up for both hands (-20% dominant, -26% non-dominant); however, there was a slight deterioration during the 3-week follow-up in the dominant hand (Figure 6A,

Table 3).

The MoCA score increased significantly by 5 points in the 1-week follow-up, with a decline of -3 points in the 3-week follow-up (Figure 6B,

Table 3). Regarding the BICAMS subscales, the SDMT showed a non-significant trend of improvement, and the GVLT-II performance remained stable with a slight significant improvement at the 3-week follow-up. The BVMT-R demonstrated a progressive improvement of 8 and 9 in the 1-week and 3-week follow-ups, respectively (Figure 6C, D, E,

Table 3).

The MSQoL-54 showed a tendency of improvement in the Physical Composite Score (PCS) from the pre- to 1-week follow-up, which was almost entirely lost at the 3-week follow-up, and a significant improvement in the Mental Composite Score (MCS). Lastly, the BDI-II score improved in the 1-week follow-up (-2) but worsened significantly at the 3-week follow-up (

Table 3).

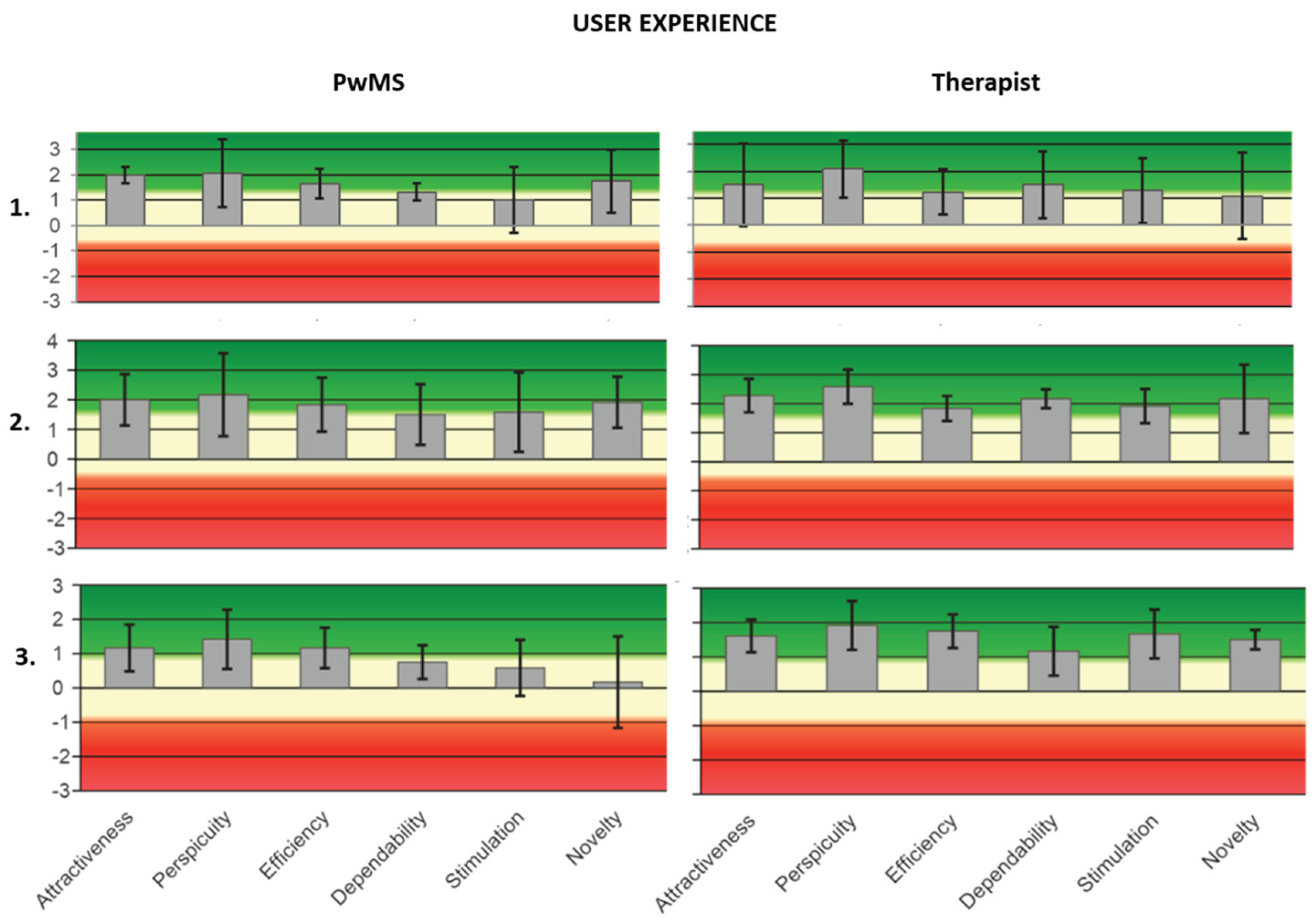

3.2.2. Acceptance

During neuromodulation, PwMS1 didn’t feel discomfort, while, regarding cognitive rehabilitation,they reported problems with concentration, attention, and physical fatigue (

Table 4). All UEQ values (post-tDCS, 1-week, and 3-week follow-ups) were positive. In particular, for PwMS1 and therapist 1, the highest mean value is for the “perspicuity” feature (M=2.08, SD=1.18; M=2.08; SD=0.95) (See supplementary materials).

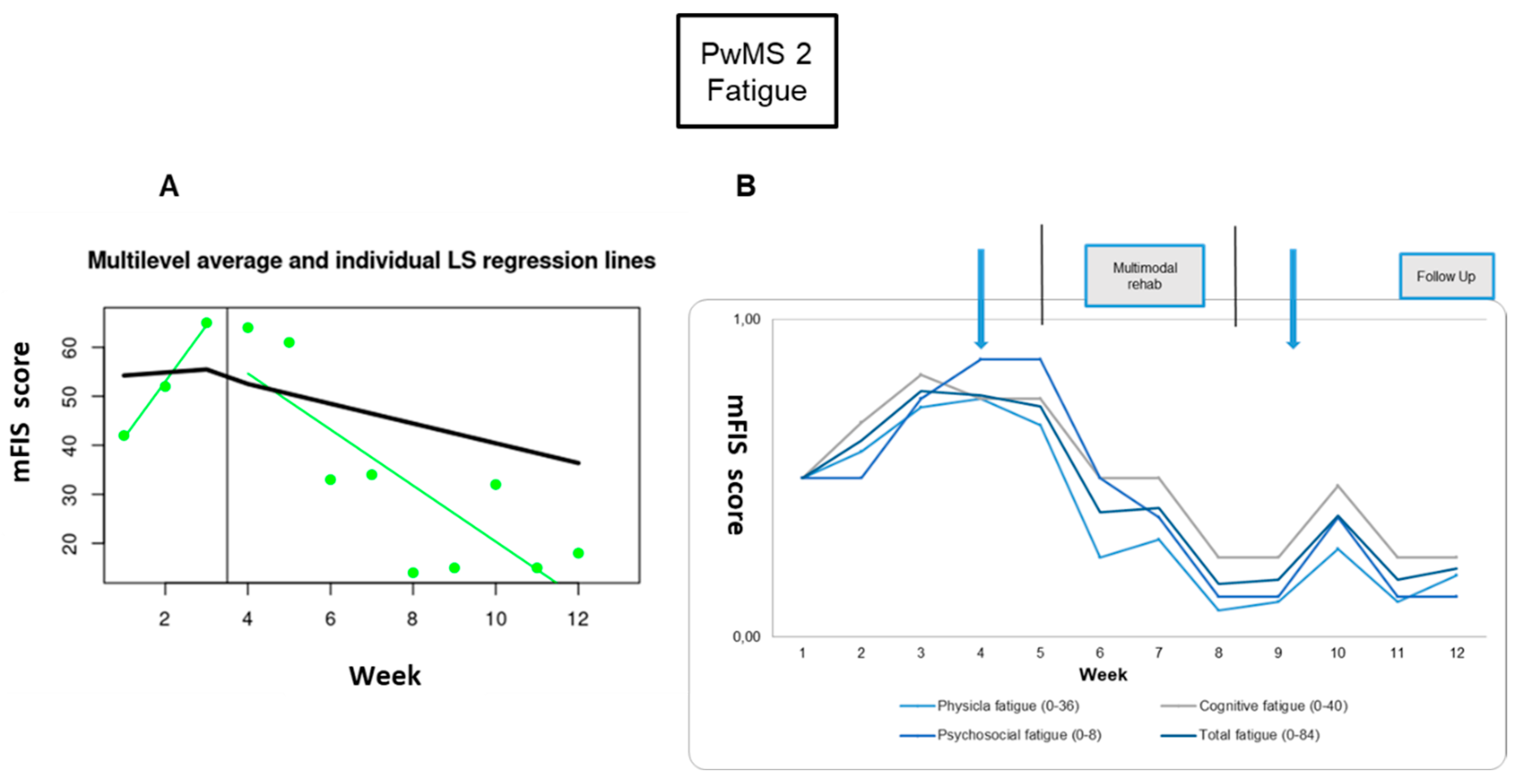

3.3. PwMS n.2

3.3.1. Individual Responsiveness

Fatigue: The fatigue symptom showed great improvement; the difference was significant between pre- and post-RehaCom intervention (-77%) and in comparison between baseline and 1-week (73%), and 3-week (68%) follow-ups (

Figure 4,

Table 2).

Neuro-psycho-motor assessment: Motor performance on the 9HPT improved in the 3-week follow-up (-20%) only for non-dominant hands (

Figure 6A,

Table 3). The MoCA score increased significantly (four points) (

Figure 6B,

Table 3). About BICAMS, the SDMT showed a significant improvement in 1-week follow-up (17 points) and in 3-week follow-up (23-points), and the GVLT-II performance had a slight significant improvement in 1-week follow-up (3-points) and a significant improvement at 3-weeks follow-up (10-points), whereas there was a difference between the 2 follow-ups (7-points). Finally, the BVMT-R demonstrated a small, significant improvement of 3 and 4 points, respectively, in the comparison between pre-rehabilitation and follow-ups (

Figure 6C, D, E,

Table 3).

A significant improvement was noted in the MSQoL-54, with a difference in the PCS from pre- to 1-week follow-up (14 points), and in MCS from pre-to 1-week follow-up (35 points) and pre-to 3-week follow-up (20-points). Finally, the BDI-II score improved from pre- to 1-week follow-up (-15 points) and 3-week follow-up (-4 points) (

Table 3).

3.3.2. Acceptance

During neuromodulation, PwMS2 didn’t feel discomfort, while, for cognitive rehabilitation, they reported frustration related to a specific module (

Table 4). All UeQ values were positive. In particular, for PwMS 2, the highest mean value is for “attractiveness” (M=2; SD=0.76), and for therapist 2 was for “perspicuity” (M=2.59; SD=0.52) (See supplementary materials).

3.4. PwMS n.3

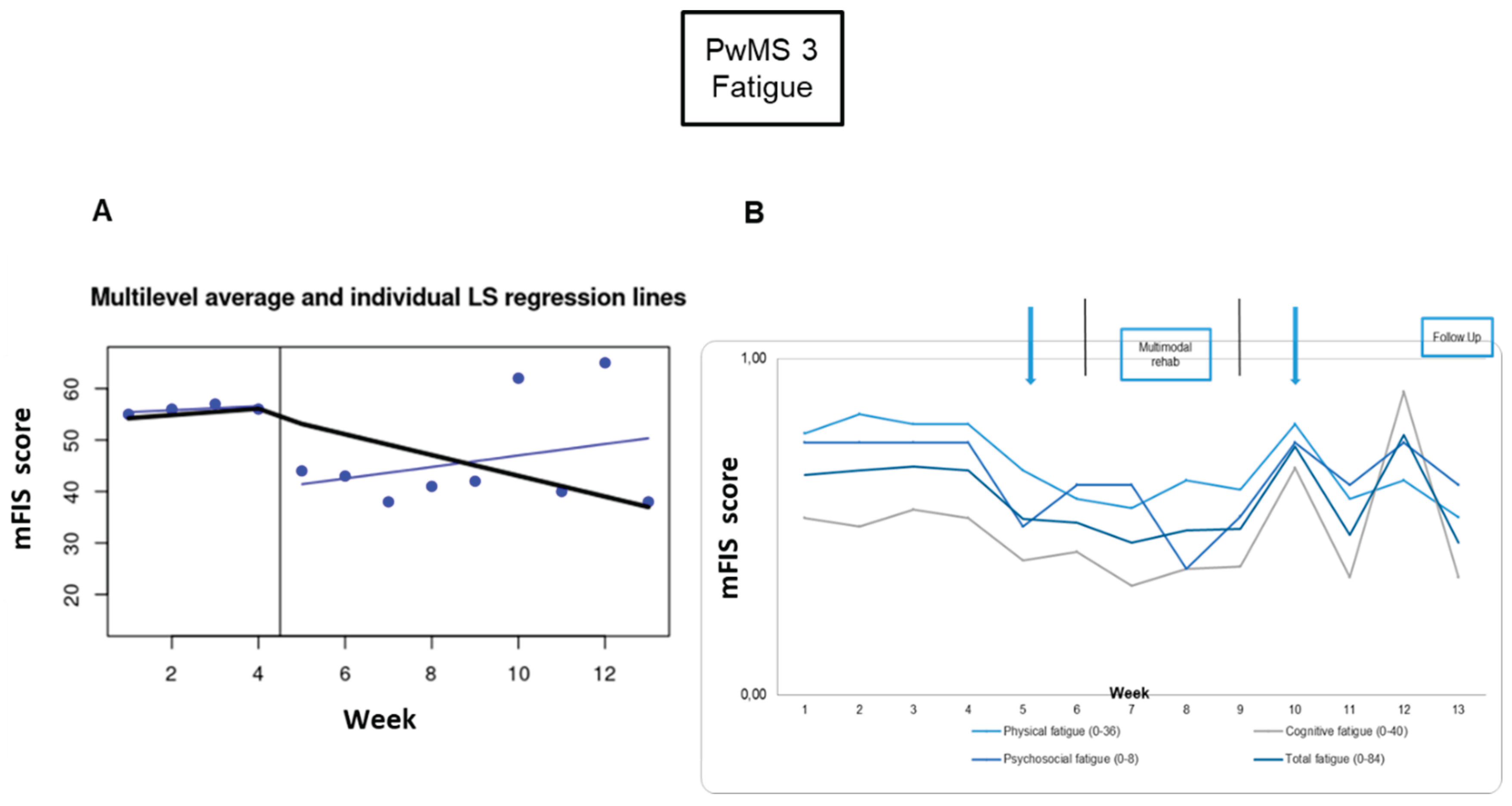

3.4.1. Individual Responsiveness

Fatigue: For PwMS3, the fatigue scores in week 4 (baseline phase) and week 9 (intervention phase) were treated as outliers, because they were 2 standard deviations away from the mean score. For week 4 and week 9, the values’ average score from weeks 1 to 3 and from weeks 5 to 8 was calculated, respectively. There were significant differences in the comparisons between baseline and post-tDCS (-20%), and between baseline and 3-week follow-up (-29%) (

Figure 6,

Table 2).

Neuro-psycho-motor assessment: Motor performance improved significantly for the non-dominant hand between pre-intervention and 1-week (-21%) and 3-week follow-up (-19%) (

Figure 6A,

Table 3). Cognitive performance wasn’t enhanced significantly based on the MoCA score, which increased only like a tendency between pre-intervention and 1-week follow-up (2-points) (

Figure 6B,

Table 3). Nevertheless, in the BICAMS, the SDMT score was significantly improved by 5 and 9 points between pre-intervention and 1-week and 3-week follow-up, respectively; the GVLT-II performance had an improvement tendency from pre to 1-week follow-up (7-points) and a significant improvement in the comparison between pre and 3-weeks follow-up (13-points), and the BVMT-R showed a significant improvement between pre- and 1-week and 3-week follow-ups (5 points) (

Figure 6C, D, E,

Table 3).

3.4.2. Acceptance

During neuromodulation, PwMS3 didn’t feel discomfort. During the cognitive rehabilitation phase, he reported health and work problems during the last week; these problems affected his performance (

Table 4). All UeQ values were positive. In particular, for both PwMS 3 and therapist 3, the highest mean value was for “perspicuity” (PwMS3 - M=1.42; SD=0.76; Therapist 3 - M=1.91, SD=0.63) (See supplementary materials).

4. Discussion

Through this mbSCED study, it is highlighted that the synergistic combination of neuromodulation and cognitive rehabilitation seems to be feasible and well-accepted by the people involved. The overall goal was to pave the way for a deeper understanding of the potential benefits, challenges, and future directions of this integrative approach, ultimately contributing to the evolution of effective strategies by personalizing therapeutic intervention for people facing MS.

4.1. Feasibility

The proposed multimodal and multi-setting therapeutic protocol was deemed feasible. Despite participants' heterogeneity in terms of personal, clinical, and social profiles, the absence of dropouts over many months indicates that the intervention was well-tolerated and perceived as overall beneficial.

A significant aspect of this study was the consistent weekly interaction between therapists and participants, which created a strong therapeutic alliance, which has been observed to enhance rehabilitation outcomes [

46]. Another point to emphasize is the feature of 'flexibility' related to remote and asynchronous rehabilitation [

47]. The participants appreciated the opportunity to manage their weekly cognitive rehabilitation plan. Consistently, when asked at final follow-up about their rehabilitation setting preference, all participants chose tele-rehabilitation, and two out of three also selected ‘home setting with a clinician coming home’, while none of them preferred the clinic setting.

4.2. Individual Responsiveness

Although there was no significant difference in fatigue scores before and immediately after tDCS, this study highlighted a longer-term positive effect on fatigue and cognitive and motor performance. The inclusion of cognitive training as part of the treatment does not allow us to discern the neuromodulation’s role, however, it is known that tDCS in combination with other treatments leads to greater clinical and metabolic changes than cognitive training alone[

48,

49,

50].

The consistency of the time behavior of the three sub-scales with the total mFIS score underlined the multifactorial nature of the personal experience of the symptom[

51,

52].

Regarding cognitive performance, PwMS showed a significant and progressive improvement in all stimulated dimensions. The MoCA values assessing the global cognitive performance improved; however, the gain at 1-week was partly lost at the 3-week follow-up. This can be explained by the nature of the test, which investigates multiple cognitive domains, some of which were not trained during the RehaCom protocol [

53,

54]. In agreement with this hypothesis, the values of the BICAMS subscales investigating the same cognitive domains that were trained had a pattern of progressive and significant improvement, with a smaller further improvement at 3 weeks’ follow-up compared to 1-week’s follow-up. The positive findings regarding the enhancement and the long-lasting effects of the treatment on attention, processing speed, and executive function in the present study are in concordance with several other studies that have used RehaCom in cognitively impaired PwMS [

55,

56,

57]. It is important to note that research has shown that cognitive training has the potential to modify the activity of trained neuronal system areas [

58,

59].

In addition, the multimodal treatment led to an overall improvement in motor performance. The trained cognitive domains are crucial for motor programming and execution, hence, their improvement helps in the organization and sequencing of motor actions. Moreover, participants performed computer exercises directly involving visual-motor coordination. The neurophysiological counterpart of this interdependence between motor and cognitive performance is linked to working memory, which makes up a network of neural fibers that allows the exchange of information between the motor and cognition regions [

60]. It can be hypothesized that tDCS promoted an increase in intra- and inter-hemispheric communication, which is useful to improve motor performance [

61]. It is important to underline that the non-dominant hand had the most significant improvement. Typically, baseline performances with the non-dominant hand are always worse than those with the dominant hand; thus, the improvement margin is typically more pronounced [

62,

63].

Finally, during the follow-up of the participants, a progressive improvement in the quality of life was observed. Specifically, the mental component of the quality of life questionnaire was enhanced in all participants, while the two younger ones with the lower EDSS score also ameliorated the physical component. Overall, signs emerged of individual empowerment by improving cognitive and motor performance and consequently the sense of agency and independence [

19,

64] supporting personal resilience [

65].

4.3. Acceptance

Regarding tDCS treatment, all participants reported no side effects or annoyance during or after stimulation –a statement that further supports the safety of the device [

66,

67] and protocol used [

68]. Part of the acceptance is probably due to the use of a commercial device that is ergonomic and user-friendly.

Concerning the RehaCom protocol PwMS reported experiencing mental fatigue and difficulty maintaining concentration during and completing the session, albeit due to differing underlying factors.

The user experience measure indicated that both PwMS and therapists (TL, NKD, and KS) mostly liked the pragmatic feature of "Perspicuity" of the protocol. By multiple items, this feature is quantified answering the question:

"Is it easy to get familiar with the product and to learn how to use it?"[

37].The familiarity and ease of use of a tool benefit both therapist and patient, fostering confident application and enhancing therapeutic effectiveness."

All stages of the treatment were accompanied by step-by-step guidance of requests and real-time feedback, and this facilitated PwMS participation and confidence. The fatigue monitoring module, the Platowork app, and the RehaCom software were built with "User-Centrated Design” to make intuitive interaction and accessibility for everyone, beyond the level of "digital education". Last but not least, the personalization of the protocol responded to the expressed needs by always proposing achievable goals and increasing adherence to the treatment [

69].

4.4. Multi-Center Collaboration Strengthened Personalized Strategies

This study was conducted by an international Greek–Italian multicenter team, with a collaboration that proved particularly enriching thanks to a fruitful exchange of complementary expertise. One group adopted the tDCS neuromodulation strategy for fatigue mitigation developed by the other, while the latter integrated the study design, an area of expertise contributed by their colleagues from the partnering country. Notably, the relevance of the SCED methodological approach is underscored by the high impact of its foundational study, which has received over 250 citations up to now (Scopus). Sharing a longstanding commitment to treatment personalization, the two teams, through the integration of multimodal approaches and the SCED framewor, took a first step toward tools for developing personalized interventions, enabling the fine-tuning of treatments already shown to be effective within symptomatically heterogeneous populations.

4.5. Study Limits

The present study had some limitations. Inherent in the SCED strategy, while it provides robust insights into individual-level efficacy, supporting the development of personalized interventions in similar clinical conditions, it does not offer statistical generalizability. Regarding neuromodulation, the advantage of using a commercial device impeded the complete implementation of the Faremus montage with the bilateral S1 stimulation as the target [

70], possibly subtending the non-significant effect of tDCS alone. Finally, self-reported scales have the great advantage of allowing us to gather information about the subjective experience of symptoms through standardized tests, but also give people the possibility to modify the answers based on social desirability or other external confusing factors [

71].

5. Conclusions

The proposed multi-center multimodal neuromodulation and cognitive rehabilitation intervention turned out to be user-friendly, well-accepted, and with a positive responsiveness in cognitive and motor performances of fatigued PwMS, increasing their empowerment and quality of life.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Teresa L'Abbate, Nefeli Dimitriou, Franca Tecchio and Grigorios Nasios; Data curation, Teresa L'Abbate and George Dimakopoulos; Formal analysis, Teresa L'Abbate and George Dimakopoulos; Investigation, Teresa L'Abbate and Nefeli Dimitriou; Methodology, Teresa L'Abbate, Nefeli Dimitriou, Franca Tecchio and Grigorios Nasios; Project administration, Teresa L'Abbate and Nefeli Dimitriou; Resources, Teresa L'Abbate and Nefeli Dimitriou; Software, George Dimakopoulos; Supervision, Franca Tecchio and Grigorios Nasios; Validation, Teresa L'Abbate, George Dimakopoulos and Franca Tecchio; Visualization, Teresa L'Abbate and George Dimakopoulos; Writing – original draft, Teresa L'Abbate and Franca Tecchio; Writing – review & editing, Teresa L'Abbate and Nefeli Dimitriou. All authors will be updated at each stage of manuscript processing, including submission, revision, and revision reminder, via emails from our system or the assigned Assistant Editor.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted by the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of the UNIVERSITY OF IOANNINA (protocol code: 7047, date of approval: 29/02/2024).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

We sincerely thank the participants with MS for allowing us to get to know them and for deciding to share with us data and information useful for scientific progress. We would also like to thank the student Kleo Samaltani for her constant presence and valuable support during the collection of data for this project. Thank you for your patience, empathy, and professional support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| PwMS |

People with Multiple Sclerosis |

| MS |

Multiple Sclerosis |

| tDCS |

Transcranial Direct Current Stimulation |

| TMS |

Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation |

| mbSCED |

Multiple Baseline Single-Case Experimental Design |

| mFIS |

modified Fatigue Impact Scale |

| EDSS |

Expanded Disability Status Scale |

| SDMT |

Symbol Digit Modality Test |

| 9 HPT |

9-Hole Peg Test |

| MoCA |

Montreal Cognitive Assessment |

| GVLT |

Greek Verbal Learning Test |

| BVMT-R |

Brief Visuospatial Memory Test-Revised |

| BICAMS |

Brief International Cognitive Assessment for MS |

| BDI |

Beck Depression Inventory |

| MSQoL-54 |

MS Quality of Life Questionnaire-54 |

| UEQ |

User Experience Questionnaire |

| mA |

milliAmpere |

| PCS |

Physical Composite Score |

| MCS |

Mental Composite Score |

Appendix A. RehaCom Protocol

According to the literature, cognitive impairment in most People with Multiple Sclerosis (PwMS) affects multiple domains, primarily memory, information processing speed/attention, and executive functions. To ensure balanced training across these domains, our intervention spanned three weeks, with equal emphasis on each domain during each session, comprising 15 minutes per exercise. The sequence of training for the three cognitive domains was randomized for each participant.

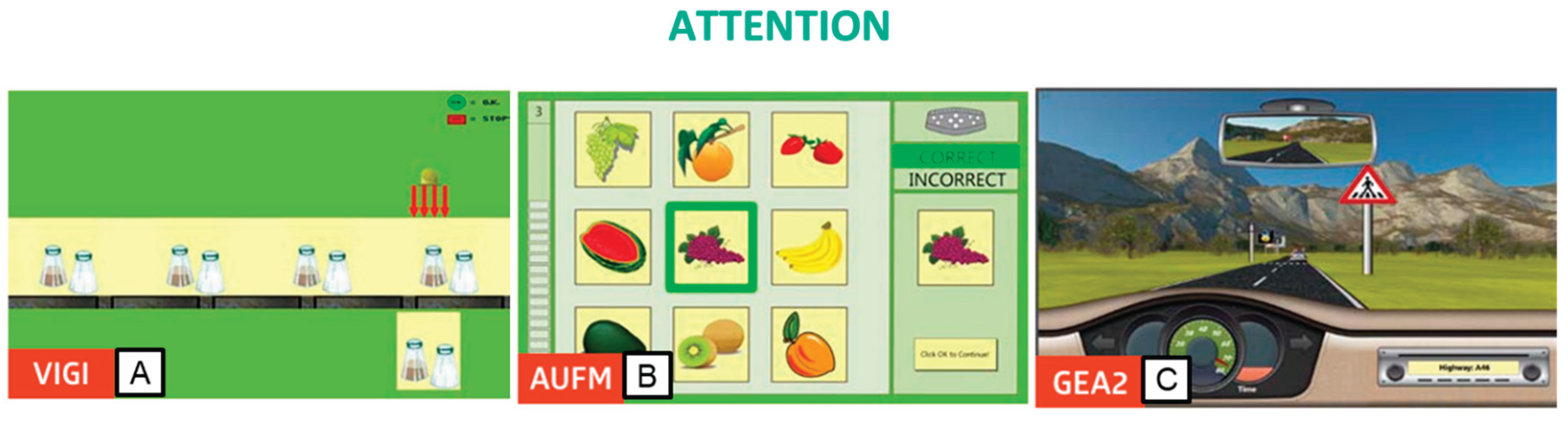

To train attention, we utilized three modules. The first module, Vigilance (VIG2), focused on developing vigilance and sustained attention, enhancing the ability to maintain attention over extended periods. Participants were tasked with observing a conveyor belt to identify objects differing from sample objects in one or more details (

Figure 1A). The second module, Attention and Concentration (AUFM), primarily targeted selective attention. Participants compared a separately presented image with a matrix of images and selected the matching image, enhancing the ability to differentiate and concentrate simultaneously (

Figure 1B). The third module, Divided Attention 2 (GEA2), required participants to attend to various external stimuli while simulating driving a car. Participants observed the changing landscape and dashboard while reacting to acoustic information, fostering the ability to divide attention effectively (

Figure 1C).

Figure 1.

Rehacom modules that stimulate attention: A. Vigilance (VIG2), B. attention and concentration (AUFM), and C. Divided Attention 2 (GEA2).

Figure 1.

Rehacom modules that stimulate attention: A. Vigilance (VIG2), B. attention and concentration (AUFM), and C. Divided Attention 2 (GEA2).

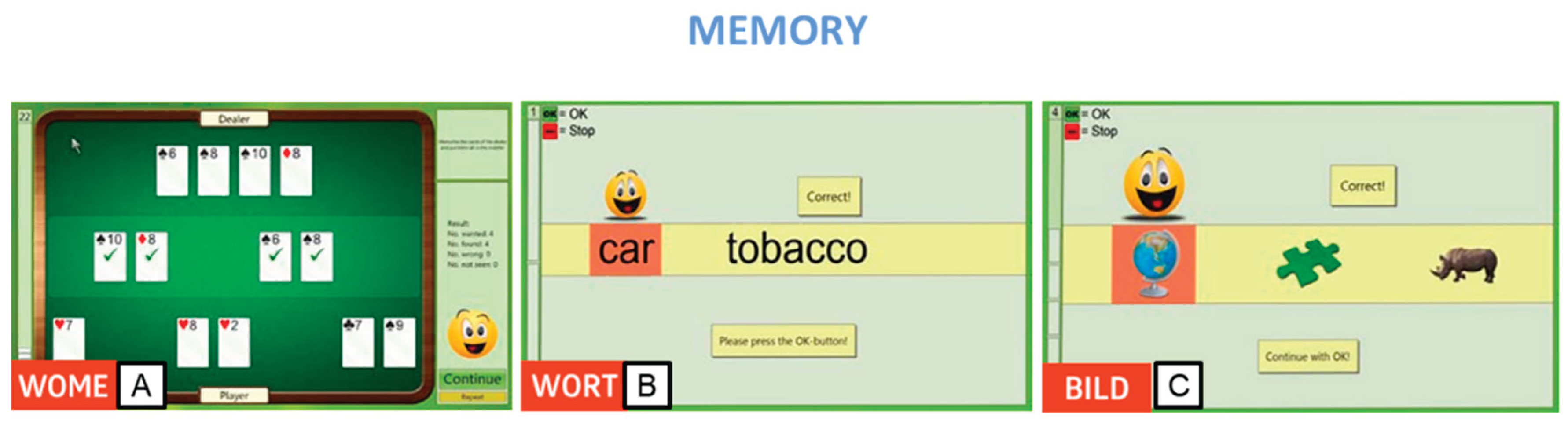

Additionally, we employed three modules to target memory. The Working Memory Module (WOME) was utilized to train working memory, focusing on the ability to store and manipulate information not present in the participant's external environment. This module emphasized the maintenance of selective attention and resistance to interference, presented in the format of a stimulating card game to enhance participant motivation (

Figure 2A). For semantic memory training, the Memory for Words (WORT) module was employed to improve the recognition of single words. During the 'learning phase,' participants memorized displayed words, and then identified them among a set of different words moving along a tape or belt (

Figure 2B). Lastly, the BILD (Figural Memory) module targeted non-verbal and verbal long-term memory. Participants memorized images containing specific objects during the 'learning phase' and later identified them among terms presented on a conveyor belt, pressing the OK button for each recognized object (

Figure 2C).

Figure 2.

Rehacom modules that stimulate memory: A. Working memory (WOME), B. Memory of Words (WORT), and C. Figural Memory (BILD).

Figure 2.

Rehacom modules that stimulate memory: A. Working memory (WOME), B. Memory of Words (WORT), and C. Figural Memory (BILD).

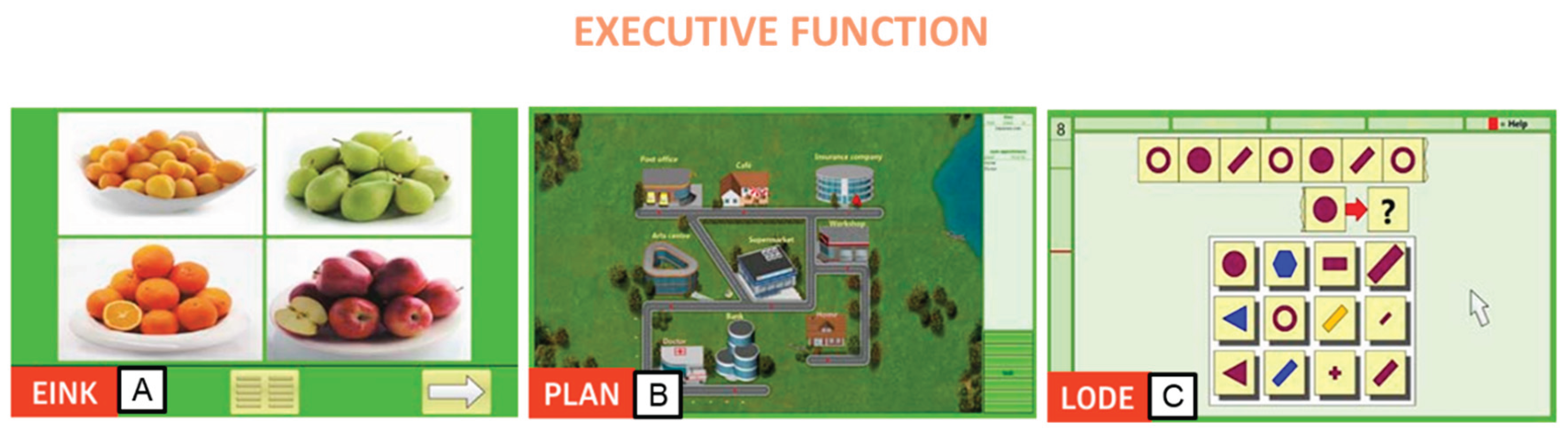

Lastly, executive functions were honed using three distinct modules. The first module, Shopping (EINK), offered a realistic exercise simulating supermarket shopping tasks on the computer. Participants received a shopping list, searched for items in a virtual supermarket, and placed them into a trolley, subsequently leaving the market upon completion. Increasing levels of difficulty incorporated additional demands on mathematical abilities (

Figure 3A). The second module, Plan a Holiday (PLAN), mirrored real-life planning scenarios. Participants crafted daily plans of varying complexity, fostering executive functions and strategic planning skills. This module challenged participants' cognitive abilities, particularly in higher difficulty levels, emphasizing logical reasoning and abstract thinking (

Figure 3B). Lastly, the Logical Reasoning (LODE) module prompted participants to identify the continuation of a given sequence of symbols. Graphic and vivid problem-solving tasks allowed participants to recognize underlying concepts and employ them to solve logic problems (

Figure 3C).

Figure 3.

Rehacom modules that stimulate executive functionsa: A. Shopping (EINK), B. Plan a Holiday (PLAN), and C. Logical reasoning (LODE).

Figure 3.

Rehacom modules that stimulate executive functionsa: A. Shopping (EINK), B. Plan a Holiday (PLAN), and C. Logical reasoning (LODE).

In summary, our cognitive rehabilitation intervention for individuals with multiple sclerosis (MS) aimed to address various cognitive impairments by balancing training across memory, attention, and executive function domains over three weeks. Using randomized sessions and specific modules targeting each cognitive domain, we sought to improve cognitive resilience and functional outcomes. This approach offers promise for enhancing cognitive functioning and quality of life in individuals with MS, with the potential for further optimization through ongoing research.

Appendix B. Graphs of User Experience Satisfaction

Figure 3.

The UEQ scale is grouped into pragmatic quality (Perspicuity, Efficiency, Dependability) and hedonic quality (Stimulation, Originality). The pragmatic quality describes the qualitative aspects relating to the task, and the hedonic quality the quality aspects related to the non-task. The values range from -3 to +3 where the negative value equals a negative experience and vice versa. On the left are the mediated results of the test, divided into 5 components, administered to PwMS1 at 3 times (Post-tDCS, 1-week, and 3-weeks follow-ups). On the right are the mediated results of the test, divided into 5 components, administered to the therapist 1 in 3 moments (Post-tDCS, 1-week and 3-week follow ups).

Figure 3.

The UEQ scale is grouped into pragmatic quality (Perspicuity, Efficiency, Dependability) and hedonic quality (Stimulation, Originality). The pragmatic quality describes the qualitative aspects relating to the task, and the hedonic quality the quality aspects related to the non-task. The values range from -3 to +3 where the negative value equals a negative experience and vice versa. On the left are the mediated results of the test, divided into 5 components, administered to PwMS1 at 3 times (Post-tDCS, 1-week, and 3-weeks follow-ups). On the right are the mediated results of the test, divided into 5 components, administered to the therapist 1 in 3 moments (Post-tDCS, 1-week and 3-week follow ups).

References

- Giovannoni, G.; Butzkueven, H.; Dhib-Jalbut, S.; Hobart, J.; Kobelt, G.; Pepper, G.; Sormani, M.P.; Thalheim, C.; Traboulsee, A.; Vollmer, T. Brain Health: Time Matters in Multiple Sclerosis. Mult. Scler. Relat. Disord. 2016, 9 Suppl 1, S5–S48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benedict, R.H.B.; Amato, M.P.; DeLuca, J.; Geurts, J.J.G. Cognitive Impairment in Multiple Sclerosis: Clinical Management, MRI, and Therapeutic Avenues. Lancet. Neurol. 2020, 19, 860–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, F.; Amatya, B.; Galea, M. Management of Fatigue in Persons with Multiple Sclerosis. Front. Neurol. 2014, 5, 110403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Messinis, L.; Kosmidis, M.H.; Lyros, E.; Papathanasopoulos, P. Assessment and Rehabilitation of Cognitive Impairment in Multiple Sclerosis. Int. Rev. Psychiatry 2010, 22, 22–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocca, M.A.; Amato, M.P.; De Stefano, N.; Enzinger, C.; Geurts, J.J.; Penner, I.K.; Rovira, A.; Sumowski, J.F.; Valsasina, P.; Filippi, M. Clinical and Imaging Assessment of Cognitive Dysfunction in Multiple Sclerosis. Lancet. Neurol. 2015, 14, 302–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guillemin, C.; Lommers, E.; Delrue, G.; Gester, E.; Maquet, P.; Collette, F. The Complex Interplay Between Trait Fatigue and Cognition in Multiple Sclerosis. Psychol. Belg. 2022, 62, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kobelt, G.; Thompson, A.; Berg, J.; Gannedahl, M.; Eriksson, J. New Insights into the Burden and Costs of Multiple Sclerosis in Europe. Mult. Scler. 2017, 23, 1123–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engel, C.; Greim, B.; Zettl, U.K. Diagnostics of Cognitive Dysfunctions in Multiple Sclerosis. J. Neurol. [CrossRef]

- Chiaravalloti, N.D.; DeLuca, J. Cognitive Impairment in Multiple Sclerosis. Lancet Neurol. 2008, 7, 1139–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, A.J.; Baranzini, S.E.; Geurts, J.; Hemmer, B.; Ciccarelli, O. Multiple Sclerosis. Lancet 2018, 391, 1622–1636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tur, C. Fatigue Management in Multiple Sclerosis. Curr. Treat. Options Neurol. 2016, 18, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nourbakhsh, B.; Revirajan, N.; Morris, B.; Cordano, C.; Creasman, J.; Manguinao, M.; Krysko, K.; Rutatangwa, A.; Auvray, C.; Aljarallah, S.; et al. Safety and Efficacy of Amantadine, Modafinil, and Methylphenidate for Fatigue in Multiple Sclerosis: A Randomised, Placebo-Controlled, Crossover, Double-Blind Trial. Lancet Neurol. 2021, 20, 38–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costa, S.L.; Genova, H.M.; Deluca, J.; Chiaravalloti, N.D. Information Processing Speed in Multiple Sclerosis: Past, Present, and Future. Mult. Scler. 2017, 23, 772–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitolo, M.; Venneri, A.; Wilkinson, I.D.; Sharrack, B. Cognitive Rehabilitation in Multiple Sclerosis: A Systematic Review. J. Neurol. Sci. 2015, 354, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leocani, L.; Chieffo, R.; Gentile, A.; Centonze, D. Beyond Rehabilitation in MS: Insights from Non-Invasive Brain Stimulation. Mult. Scler. J. 2019, 25, 1363–1371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertoli, M.; Tecchio, F. Fatigue in Multiple Sclerosis: Does the Functional or Structural Damage Prevail? Mult. Scler. 2020, 26, 1809–1815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uygur-Kucukseymen, E.; Pacheco-Barrios, K.; Yuksel, B.; Gonzalez-Mego, P.; Soysal, A.; Fregni, F. Non-Invasive Brain Stimulation on Clinical Symptoms in Multiple Sclerosis Patients: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Mult. Scler. Relat. Disord. 2023, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasios, G.; Bakirtzis, C.; Messinis, L. Cognitive Impairment and Brain Reorganization in MS: Underlying Mechanisms and the Role of Neurorehabilitation. Front. Neurol. 2020, 11, 524745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, W.Y.; Cheng, C.H.; Zanto, T.P.; Gazzaley, A.; Bove, R.M. Effects of Transcranial Direct Current Stimulation on Cognition, Mood, Pain, and Fatigue in Multiple Sclerosis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front. Neurol. 2021, 12, 626113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krasny-Pacini, A.; Evans, J. Single-Case Experimental Designs to Assess Intervention Effectiveness in Rehabilitation: A Practical Guide. Ann. Phys. Rehabil. Med. 2018, 61, 164–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lillie, E.O.; Patay, B.; Diamant, J.; Issell, B.; Topol, E.J.; Schork, N.J. The N-of-1 Clinical Trial: The Ultimate Strategy for Individualizing Medicine? Per. Med. 2011, 8, 161–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doshi, A.; Chataway, J. Multiple Sclerosis, a Treatable Disease. Clin. Med. 2016, 16, s53–s59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thompson, A.J.; Banwell, B.L.; Barkhof, F.; Carroll, W.M.; Coetzee, T.; Comi, G.; Correale, J.; Fazekas, F.; Filippi, M.; Freedman, M.S.; et al. Diagnosis of Multiple Sclerosis: 2017 Revisions of the McDonald Criteria. Lancet Neurol. 2018, 17, 162–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McDonald, W.I.; Compston, A.; Edan, G.; Goodkin, D.; Hartung, H.P.; Lublin, F.D.; McFarland, H.F.; Paty, D.W.; Polman, C.H.; Reingold, S.C.; et al. Recommended Diagnostic Criteria for Multiple Sclerosis: Guidelines from the International Panel on the Diagnosis of Multiple Sclerosis. Ann Neurol 2001, 50, 121–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urbaniak, G.C.; Plous, S. Research Randomizer (Version 4.0) [Computer Software] 2013.

- Strober, L.B.; Bruce, J.M.; Arnett, P.A.; Alschuler, K.N.; DeLuca, J.; Chiaravalloti, N.; Lebkuecher, A.; Di Benedetto, M.; Cozart, J.; Thelen, J.; et al. Tired of Not Knowing What That Fatigue Score Means? Normative Data of the Modified Fatigue Impact Scale (MFIS). Mult. Scler. Relat. Disord. 2020, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Schependom, J.; D’hooghe, M.B.; Cleynhens, K.; D’hooge, M.; Haelewyck, M.C.; De Keyser, J.; Nagels, G. The Symbol Digit Modalities Test as Sentinel Test for Cognitive Impairment in Multiple Sclerosis. Eur. J. Neurol. 2014, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kellor, M.; Frost, J.; Silberberg, N.; Iversen, I.; Cummings, R. Hand Strength and Dexterity. Am. J. Occup. Ther. Off. Publ. Am. Occup. Ther. Assoc. 1971, 25, 77–83. [Google Scholar]

- Konstantopoulos, K.; Vogazianos, P. Montreal Cognitive Assessment in a Greek Sample of Patients with Multiple Sclerosis: A Validation Study. Appl. Neuropsychol. Adult 2021, 28, 48–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messinis, L.; Bakirtzis, C.; Kosmidis, M.H.; Economou, A.; Nasios, G.; Anyfantis, E.; Konitsiotis, S.; Ntoskou, A.; Peristeri, E.; Dardiotis, E.; et al. Symbol Digit Modalities Test: Greek Normative Data for the Oral and Written Version and Discriminative Validity in Patients with Multiple Sclerosis. Arch. Clin. Neuropsychol. 2021, 36, 117–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlahou, C.H.; Kosmidis, M.H.; Dardagani, A.; Tsotsi, S.; Giannakou, M.; Giazkoulidou, A.; Zervoudakis, E.; Pontikakis, N. Development of the Greek Verbal Learning Test: Reliability, Construct Validity, and Normative Standards. Arch. Clin. Neuropsychol. 2013, 28, 52–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benedict, R.H.B.; Groninger, L.; Schretlen, D.; Dobraski, M.; Shpritz, B. Revision of the Brief Visuospatial Memory Test: Studies of Normal Performance, Reliability, and, Validity. Psychol. Assess. 1996, 8, 145–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakalidou, D.; Voumvourakis, K.; Tsourti, Z.; Papageorgiou, E.; Poulios, A.; Giannopoulos, S. Validity and Reliability of the Greek Version of the Modified Fatigue Impact Scale in Multiple Sclerosis Patients. Int. J. Rehabil. Res. 2014, 37, 271–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petropoulos, D.; Peritogiannis, V. Depressive Symptoms and Quality of Life in Elderly People Undergoing Physical Therapy. Int. J. Caring Sci. 2021, 14, 854. [Google Scholar]

- Kapina, V.; Καπινά, Β. H Δυνατότητα Προς Εργασία Των Aσθενών Με Πολλαπλή Σκλήρυνση: Συσχέτιση Με Κλινικά, Ψυχομετρικά Και Νευροακτινολογικά Δεδομένα, Aριστοτέλειο Πανεπιστήμιο Θεσσαλονίκης (AΠΘ). Σχολή Επιστημών Υγείας. Τμήμα Ιατρικής. Τομέας Νευροεπιστημών. Κλινική Γ’ Νευρολογική Γενικού Περιφερειακού Νοσοκομείου Θεσσαλονίκης Γ ΠAΠAΝΙΚOΛAOΥ, 2009.

- Vickrey, B.G.; Hays, R.D.; Harooni, R.; Myers, L.W.; Ellison, G.W. A Health-Related Quality of Life Measure for Multiple Sclerosis. Qual. Life Res. 1995, 4, 187–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laugwitz, B.; Held, T.; Schrepp, M. Construction and Evaluation of a User Experience Questionnaire. Lect. Notes Comput. Sci. (including Subser. Lect. Notes Artif. Intell. Lect. Notes Bioinformatics), 76. [CrossRef]

- Cancelli, A.; Cottone, C.; Giordani, A.; Migliore, S.; Lupoi, D.; Porcaro, C.; Mirabella, M.; Rossini, P.M.; Filippi, M.M.; Tecchio, F. Personalized, Bilateral Whole-Body Somatosensory Cortex Stimulation to Relieve Fatigue in Multiple Sclerosis. Mult. Scler. J. 2018, 24, 1366–1374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tecchio, F.; Cancelli, A.; Cottone, C.; Zito, G.; Pasqualetti, P.; Ghazaryan, A.; Rossini, P.M.; Filippi, M.M. Multiple Sclerosis Fatigue Relief by Bilateral Somatosensory Cortex Neuromodulation. J. Neurol. 2014, 261, 1552–1558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naeeni Davarani, M.; Arian Darestani, A.; Hassani-Abharian, P.; Vaseghi, S.; Zarrindast, M.R.; Nasehi, M. RehaCom Rehabilitation Training Improves a Wide-Range of Cognitive Functions in Multiple Sclerosis Patients. Appl. Neuropsychol. Adult 2022, 29, 262–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kratochwill, T.R.; Hitchcock, J.H.; Horner, R.H.; Levin, J.R.; Odom, S.L.; Rindskopf, D.M.; Shadish, W.R. Single-Case Intervention Research Design Standards. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0741932512452794 2012, 34, 26–38. [CrossRef]

- Feys, P.; Lamers, I.; Francis, G.; Benedict, R.; Phillips, G.; Larocca, N.; Hudson, L.D.; Rudick, R. The Nine-Hole Peg Test as a Manual Dexterity Performance Measure for Multiple Sclerosis. Mult. Scler. 2017, 23, 711–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benedict, R.H.B.; Amato, M.P.; Boringa, J.; Brochet, B.; Foley, F.; Fredrikson, S.; Hamalainen, P.; Hartung, H.; Krupp, L.; Penner, I.; et al. Brief International Cognitive Assessment for MS (BICAMS): International Standards for Validation. BMC Neurol. 2012, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nasreddine, Z.S.; Phillips, N.A.; Bédirian, V.; Charbonneau, S.; Whitehead, V.; Collin, I.; Cummings, J.L.; Chertkow, H. The Montreal Cognitive Assessment, MoCA: A Brief Screening Tool for Mild Cognitive Impairment. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2005, 53, 695–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kendall, P.C.; Hollon, S.D.; Beck, A.T.; Hammen, C.L.; Ingram, R.E. Issues and Recommendations Regarding Use of the Beck Depression Inventory. Cognit. Ther. Res. 1987, 11, 289–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heredia-Callejón, A.; García-Pérez, P.; Armenta-Peinado, J.A.; Infantes-Rosales, M.Á.; Rodríguez-Martínez, M.C. Influence of the Therapeutic Alliance on the Rehabilitation of Stroke: A Systematic Review of Qualitative Studies. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 4266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gopal, A.; Bonanno, V.; Block, V.J.; Bove, R.M. Accessibility to Telerehabilitation Services for People With Multiple Sclerosis: Analysis of Barriers and Limitations. Int. J. MS Care 2022, 24, 260–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charvet, L.; Shaw, M.; Dobbs, B.; Frontario, A.; Sherman, K.; Bikson, M.; Datta, A.; Krupp, L.; Zeinapour, E.; Kasschau, M. Remotely Supervised Transcranial Direct Current Stimulation Increases the Benefit of At-Home Cognitive Training in Multiple Sclerosis. Neuromodulation 2018, 21, 383–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nissim, N.R.; O’Shea, A.; Indahlastari, A.; Kraft, J.N.; von Mering, O.; Aksu, S.; Porges, E.; Cohen, R.; Woods, A.J. Effects of Transcranial Direct Current Stimulation Paired With Cognitive Training on Functional Connectivity of the Working Memory Network in Older Adults. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2019, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simani, L.; Roozbeh, M.; Shojaei, M.; Ramezani, M.; Roozbeh, M.; Gharehgozli, K.; Rostami, M. The Effectiveness of Anodal TDCS and Cognitive Training on Cognitive Functions in Multiple Sclerosis; a Randomized, Double-Blind, Parallel-Group Study. Mult. Scler. Relat. Disord. 2022, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David Ruban, S.; Christina Hilt, C.; Petersen, T. Quality of Life in Multiple Sclerosis: The Differential Impact ofmotor and Cognitive Fatigue. Mult. Scler. J. - Exp. Transl. Clin. 2021, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riemenschneider, M.; Trénel, P.; Nørgaard, M.; Boesen, F. Multimethodological Validation of the Modified Fatigue Impact Scale in a Danish Population of People with Multiple Sclerosis. Mult. Scler. Relat. Disord. 2022, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Traut, H.J.; Guild, R.M.; Munakata, Y. Why Does Cognitive Training Yield Inconsistent Benefits? A Meta-Analysis of Individual Differences in Baseline Cognitive Abilities and Training Outcomes. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 662139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, W.; Liang, J.; Xue, J.; Zhu, T.; Jiang, Y.; Wang, J.; Chen, S. The Transfer Effects of Cognitive Training on Working Memory among Chinese Older Adults with Mild Cognitive Impairment: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2019, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattioli, F.; Stampatori, C.; Zanotti, D.; Parrinello, G.; Capra, R. Efficacy and Specificity of Intensive Cognitive Rehabilitation of Attention and Executive Functions in Multiple Sclerosis. J. Neurol. Sci. 2010, 288, 101–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattioli, F.; Stampatori, C.; Scarpazza, C.; Parrinello, G.; Capra, R. Persistence of the Effects of Attention and Executive Functions Intensive Rehabilitation in Relapsing Remitting Multiple Sclerosis. Mult. Scler. Relat. Disord. 2012, 1, 168–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pappalardo, A. Neurorehabilitation in Persons with Multiple Sclerosis: Scientific Basis and Options of Treatment. Phys. Med. Rehabil. Res. 2016, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filippi, M.; Riccitelli, G.; Mattioli, F.; Capra, R.; Stampatori, C.; Pagani, E.; Valsasina, P.; Copetti, M.; Falini, A.; Comi, G.; et al. Multiple Sclerosis: Effects of Cognitive Rehabilitation on Structural and Functional MR Imaging Measures - An Explorative Study. Radiology 2012, 262, 932–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiaravalloti, N.D.; Genova, H.M.; DeLuca, J. Cognitive Rehabilitation in Multiple Sclerosis: The Role of Plasticity. Front. Neurol. 2015, 6, 136401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eschweiler, M.; Bohr, L.; Kessler, J.; Fink, G.R.; Kalbe, E.; Onur, O.A. Combined Cognitive and Motor Training Improves the Outcome in the Early Phase after Stroke and Prevents a Decline of Executive Functions: A Pilot Study. NeuroRehabilitation 2021, 48, 97–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Philip, B.A.; Frey, S.H. Increased Functional Connectivity between Cortical Hand Areas and Praxis Network Associated with Training-Related Improvements in Non-Dominant Hand Precision Drawing. Neuropsychologia 2016, 87, 157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boroujeni, T.S.; Abbasnia, A.; Doosti, M. Training with Non-Dominant Limb: A Helpful Strategy for Motor Function and Dual-Task Cost in Multiple Sclerosis Patients. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gidon, A.; Zolnik, T.A.; Fidzinski, P.; Bolduan, F.; Papoutsi, A.; Poirazi, P.; Holtkamp, M.; Vida, I.; Larkum, M.E. Dendritic Action Potentials and Computation in Human Layer 2/3 Cortical Neurons. Science (80-. ). 2020, 367, 83–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munger, K.C.; Martinez, A.P.; Hyland, M.H. The Impact of Cognitive Rehabilitation on Quality of Life in Multiple Sclerosis: A Pilot Study. Mult. Scler. J. - Exp. Transl. Clin. 2021, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novak, A.M.; Lev-Ari, S. Resilience, Stress, Well-Being, and Sleep Quality in Multiple Sclerosis. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bikson, M.; Hanlon, C.A.; Woods, A.J.; Gillick, B.T.; Charvet, L.; Lamm, C.; Madeo, G.; Holczer, A.; Almeida, J.; Antal, A.; et al. Guidelines for TMS/TES Clinical Services and Research through the COVID-19 Pandemic. Brain Stimul. 2020, 13, 1124–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.; Lee, H.; Yu, S.; Lee, M.; Kim, H.J.; Kwon, R.; Kim, S.; Fond, G.; Boyer, L.; Rahmati, M.; et al. Effects and Safety of Transcranial Direct Current Stimulation on Multiple Health Outcomes: An Umbrella Review of Randomized Clinical Trials. Mol. Psychiatry 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gianni, E.; Bertoli, M.; Simonelli, I.; Paulon, L.; Tecchio, F.; Pasqualetti, P. TDCS Randomized Controlled Trials in No-Structural Diseases: A Quantitative Review. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 16311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fager, S.K.; Burnfield, J.M. Patients’ Experiences with Technology during Inpatient Rehabilitation: Opportunities to Support Independence and Therapeutic Engagement. Disabil. Rehabil. Assist. Technol. 2014, 9, 121–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tecchio, F.; Cancelli, A.; Pizzichino, A.; L’Abbate, T.; Gianni, E.; Bertoli, M.; Paulon, L.; Zannino, S.; Giordani, A.; Lupoi, D.; et al. Home Treatment against Fatigue in Multiple Sclerosis by a Personalized, Bilateral Whole-Body Somatosensory Cortex Stimulation. Mult. Scler. Relat. Disord. 2022, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basch, E.; Barbera, L.; Kerrigan, C.L.; Velikova, G. Implementation of Patient-Reported Outcomes in Routine Medical Care. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. Educ. book. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. Annu. Meet. 2018, 38, 122–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).