1. Introduction

Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI) constitutes an intermediate clinical condition, bridging the continuum from normal cognitive aging to dementia; it is characterized by objective deficits in one or more cognitive domains in the context of largely preserved basic activities of daily living (ADL). It is a prodromal condition associated with an increased risk of progression to dementia and, consequently, a priority target for preventive and rehabilitative strategies [

1,

2,

3]. In Italy and across Europe, demographic aging is producing a substantial and growing epidemiological burden of MCI [

4,

5,

6]: consider that in Italy the number of cases is increasing due to population aging, and current projections estimate that by 2025 there will be 1.5 million people living with dementia in Italy [

7].

Even in the absence of frank disability in basic ADL, many individuals with MCI present limitations in instrumental activities of daily living (IADL), reduced social participation [

8,

9,

10], increased risk of falls linked to attentional and executive inefficiencies [

11,

12], as well as mood disturbances or perceived loneliness, the latter acting as an additional negative reinforcement of cognitive deterioration [

13,

14,

15]. These factors translate into lower quality of life and a non-negligible burden for informal caregivers [

16,

17], understood as all those who provide continuous, unpaid care to someone with a chronic illness or disability.

Multicomponent non-pharmacological approaches are increasingly recommended in MCI. In particular, programs that combine cognitive stimulation/training and physical exercise, including dual-task paradigms, show benefits in selected cognitive domains, physical function and, in some studies, activities of daily living [

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25].

Telerehabilitation targeting cognitive and motor-cognitive domains allows for personalized home implementation, showing encouraging evidence of feasibility and adherence, and yielding results analogous to those achieved in traditional face-to-face settings; however, standardized home protocols specific to MCI, harmonized outcome measures, and robust implementation metrics (adoption, acceptability) still need to be consolidated [

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31]. From this perspective, home-based motor-cognitive telerehabilitation emerges as a practicable and scalable care pathway for people with MCI and their caregivers: it combines regular home sessions with remote monitoring and feedback, integrates digital tools with the therapist–patient relationship (“Volto Amico”), and promotes the personalization of exercises based on the cognitive-motor profile; involvement of the patient–caregiver dyad supports adherence and continuity, while linkage with community services enables proximity care.

Background and Rationale

The goals of Cognitive–Motor Rehabilitation are to slow the progression of cognitive decline, strengthen residual cognitive functions, improve autonomy in activities of daily living, maintain and enhance the quality of life of both the individual and the caregiver, and promote neuroplasticity through the combination of motor and cognitive stimuli.

To achieve these goals, as suggested by the scientific evidence, it may be useful to follow a cognitive–motor training program aimed at slowing the progression of cognitive damage, improving brain functions in older adults with mild cognitive impairment, and enhancing the emotional and physical well-being of both caregivers and the older person.

Telerehabilitation represents an effective tool for achieving therapeutic objectives. It can indeed be used to implement a cognitive–motor stimulation pathway dedicated to the person with MCI/caregiver dyad [

32]. This modality can be useful and highly advantageous in several respects and is increasingly supported by scientific and clinical evidence. Integrating the caregiver into the cognitive–motor rehabilitation pathway is not merely an option, but a promising strategy that can significantly improve the effectiveness of the intervention, the quality of life of both parties, and the relational dynamic [

33,

34].

Several technological solutions are available on the market and employed in telerehabilitation devices. Among the most innovative is the one based on human body and joint recognition, such as the markerless system integrated into the “Homing” device (Tecnobody, Dalmine – BG – Italy). This technology makes it possible to objectively assess and/or train cognitive–motor areas through visual and auditory feedback, targeting people with mild cognitive deficits and their caregivers. The goal is to develop personalized rehabilitation protocols. Such solutions make it possible to follow the patient–caregiver dyad remotely, facilitating adherence to the cognitive–motor training program and improving engagement.

The innovative element lies precisely in the involvement not only of patients in their home environment, but also of their family members and professionals; this process represents a new model of cognitive/motor rehabilitation and remote consultation, which could significantly increase the efficiency of home services.

Aim of the Study

The purpose of the study is to test an intervention model that incorporates advanced technology into health and social care services and develops new home-based models of care. Accordingly, the study has a dual objective: on the one hand, to support the maintenance of brain/cognitive functions in people with mild cognitive impairment and to improve the emotional and physical well-being of caregivers; on the other, to contribute to the creation of new welfare service models through the use of emerging technologies. One of the most innovative and distinctive aspects is the intention to create a new model of care that integrates technological and telerehabilitation components with the relational skills of the professionals involved, fostering collaboration and synergy among experts from different settings with a common goal: the well-being of people with MCI and their caregivers.

2. Methods

The trial is a non-inferiority, single center, single blinded pilot study involving MCI outpatients from a neurorehabilitation facility in Italy (Centro eccellenza Alzheimer di Gazzaniga) with a parallel two groups design (1:1 allocation ratio to the 2 treatment). MCI outpatients have been recruited through two services of Centro eccellenza Alzheimer di Gazzaniga: Some of the enrolled patients had been discharged from a 60-day, high-intensity inpatient rehabilitation program; others had completed the MAC service (Complex Ambulatory Macro-Activity), a personalized cognitive stimulation pathway in which the patient participated through daily visits scheduled by the center’s neuropsychologists.

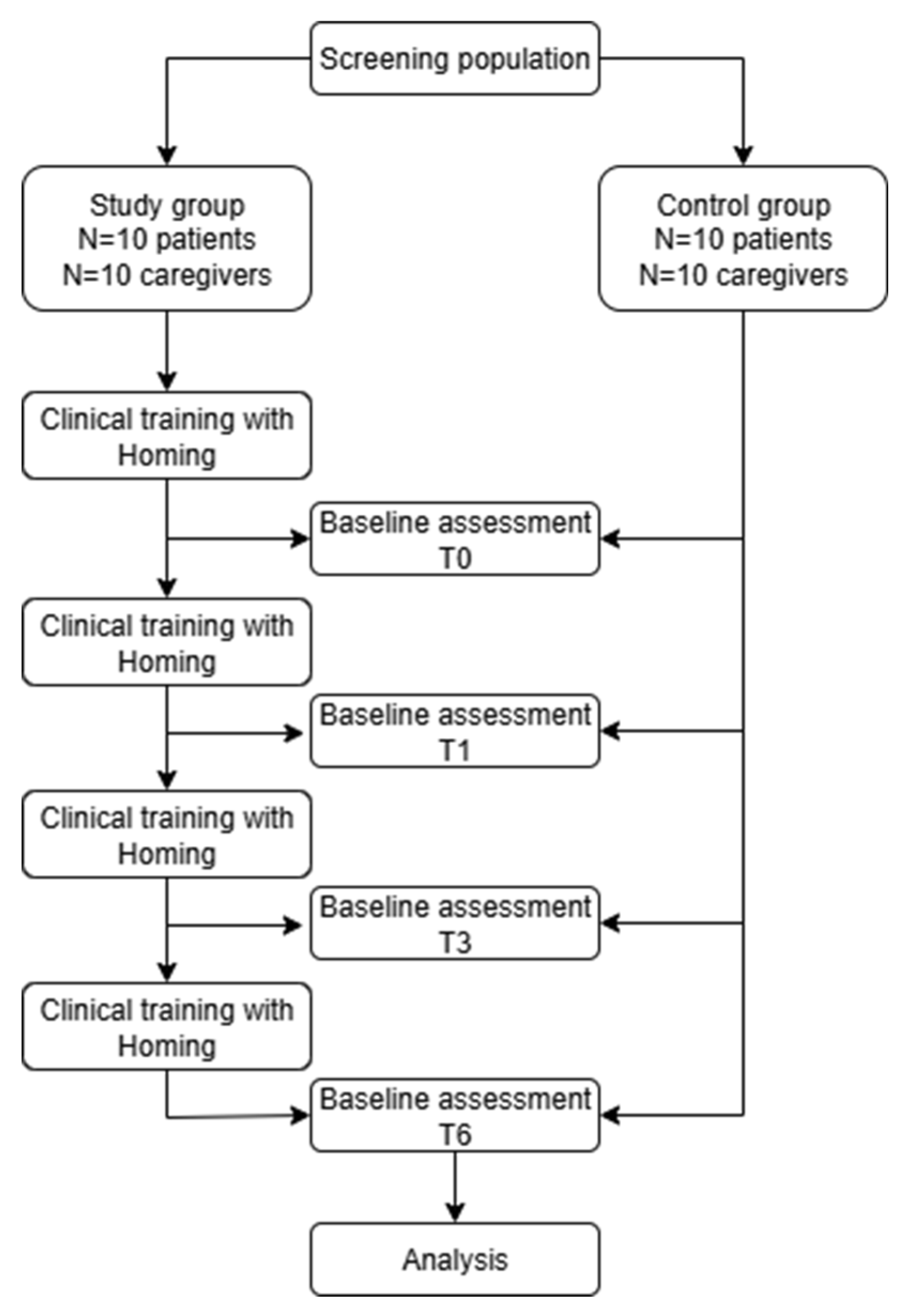

The trial work plan is described in

Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Trial work plan.

Figure 1.

Trial work plan.

Eligibility Criteria

The inclusion criteria for all participants are:

Diagnosis of MCI with MMSE ≥ 24

Availability of the person with MCI/caregiver dyad

Stable neurological therapy during the 6-month treatment period

Age and sex: any

The exclusion criteria, instead, are:

Randomization and Recruitment

Eligible patients who meet the inclusion criteria will have been randomized through the permuted block randomization technique. The randomization sequence for assigning participants to interventions kept hidden to the people involved in the recruitment.

Blinding

In line with previous studies on the efficacy of telerehabilitation on MCI patients, the trial intervention will incorporate blinding only for patients and not for clinicians.

Study Design and Setting

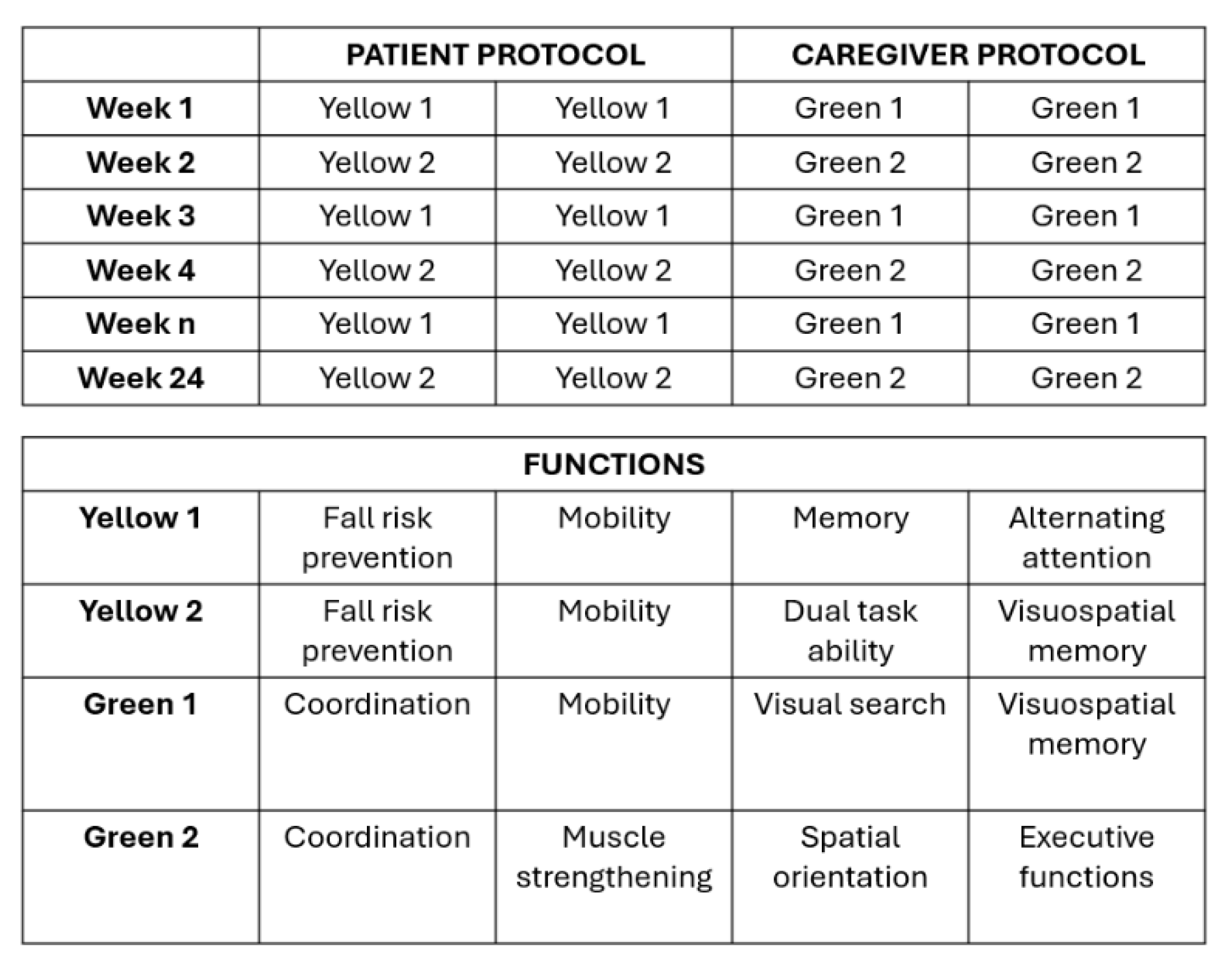

The treatment protocol includes two types of motor–cognitive training, one for patients and one for their respective caregivers. In total, four programs were developed for participants: two for patients (Yellow one, Yellow two) and two for caregivers (Green one, Green two), as shown in

Figure 2a,b. The aim is to administer the two programs in alternating weeks for both patients and caregivers to avoid habituation and demotivation effects. Activities are scheduled twice per week. The contents of each program are consistent in their therapeutic goals, although the specific exercises differ.

Cognitive tasks target functions such as attention, executive functions, language, perception, and memory; motor tasks, instead, target static and dynamic balance.

Figure 2.

a) Patient and Caregiver protocol – b) Training functions.

Figure 2.

a) Patient and Caregiver protocol – b) Training functions.

All participants were followed longitudinally by a physiotherapist acting as a teleconsultant (“Volto Amico”), responsible for: (i) installing the equipment at home, (ii) training the dyad in proper use, and (iii) continuous monitoring of progress through remote visits, scheduled every 15 days and as needed.

The effectiveness of the proposed treatments was assessed for both members of the patient/caregiver dyad. For patients, effectiveness was evaluated in terms of cognition, function, and mood using the ACE III, MMSE, and the 15-item Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS-15); autonomy with the Barthel Index; balance and gait with the Tinetti Scale; and perceived loneliness with the UCLA Loneliness Scale. For caregivers, effectiveness was evaluated in terms of mood and reduction of stress and loneliness using the CBI, GDS-15, UCLA Loneliness Scale, and the Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (MSPSS).

The study evaluates the effectiveness of the Homing home intervention in patient–caregiver dyads with cognitive impairment, comparing them with a control group receiving standard treatment only, corresponding to usual care.

For both the study and control groups, assessments were performed at enrollment and after one, three, and six months.

Control Group – No Clinical Protocol

Control group, made by patients and their caregivers will perform any kind of clinical protocol and will be assessed with clinical scale by clinicians.

Study Group - Home Telerehabilitation Treatment

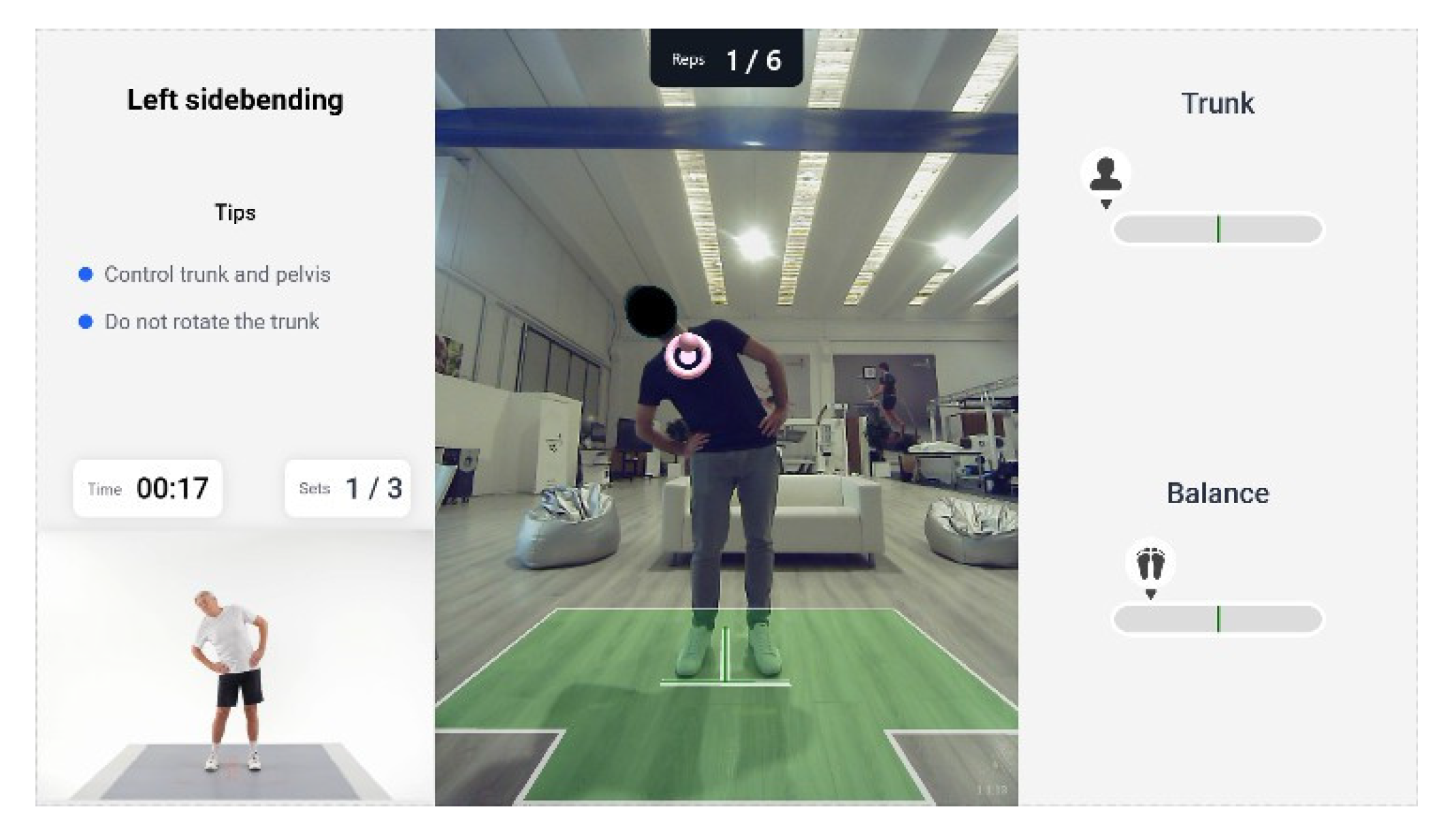

The experimental group followed a home telerehabilitation clinical protocol. The protocol consists of exercises performed using Homing technology and the telerehabilitation mode via “Volto Amico”. All exercises are conducted digitally, replicating movements within a virtual or augmented reality environment. For example, the reaching exercise is performed in augmented reality, where participants position the required joint within an augmented reality target, carrying out tasks such as grasping targets (see

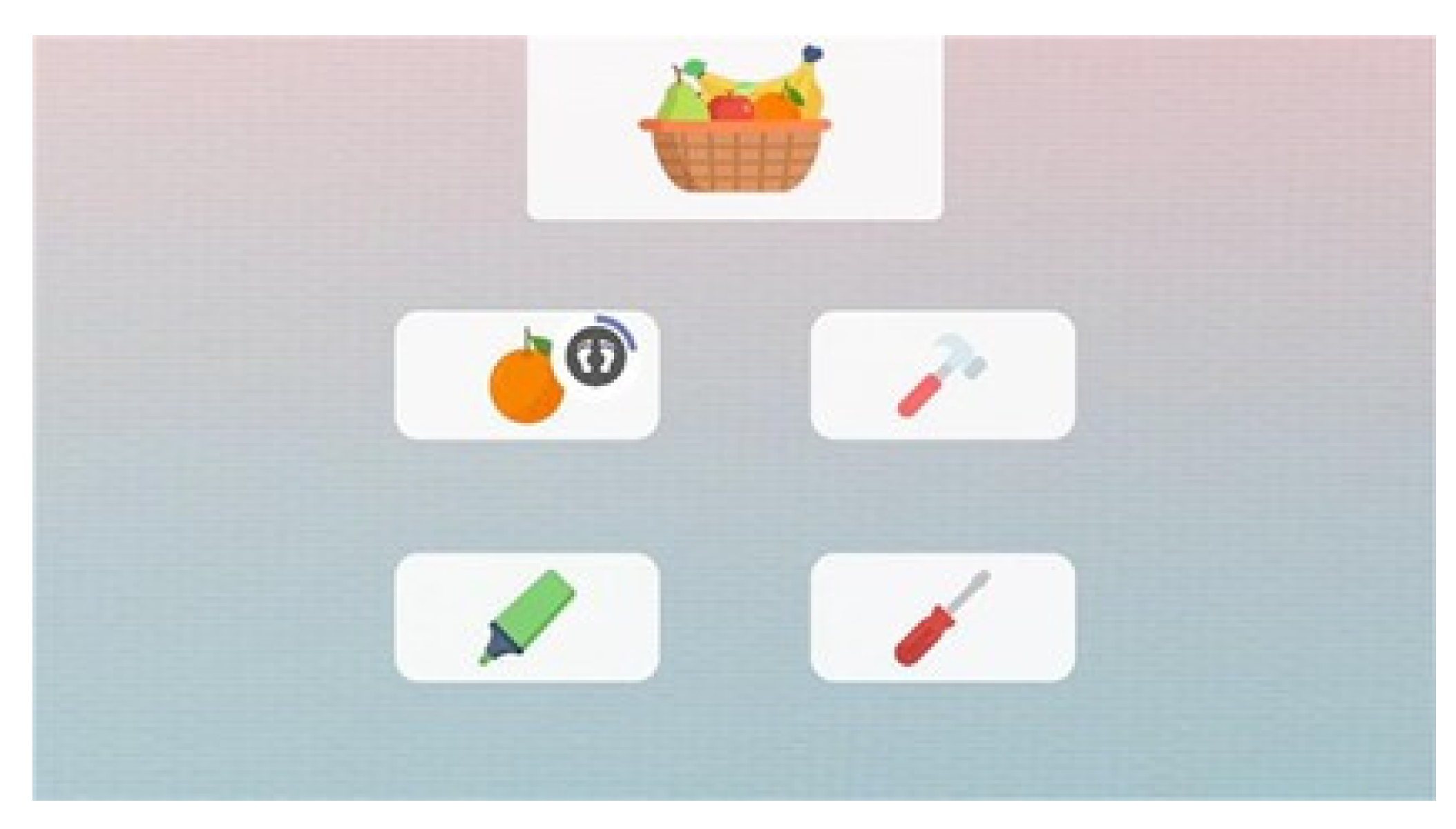

Figure 3). In addition, the exercises incorporate a cognitive–motor dual-task component whose complexity is progressively managed over the weeks (see

Figure 4). Therapists can also provide feedback based on videoconference observations and on the review of electronic data (training reports, scores) and, in turn, receive feedback during training sessions thanks to the virtual connection. Moreover, the patient’s knowledge of results, provided through explicit feedback on quantitative or qualitative task outcomes (e.g., correctness, accuracy, success or failure), represents more than a simple extrinsic reinforcement and contributes to learning through cognitive processing [

35,

36,

37]. At the time of home installation, the exercises are explained and performed together with the therapist using Homing directly.

Prescription of exercise difficulty is crucial, balancing perceived fatigue and performance quality. Homing is equipped with a self-adjustment algorithm that considers quality of execution, represented by a 0–100 score based on repetitions, trunk control, balance, and errors. Scores below 20% indicate tasks that are too demanding, whereas scores above 80% indicate tasks that are too easy. The cut-offs of the above-mentioned items are combined within the algorithm to automatically adjust both the difficulty level of each exercise and the number of distractors to be included in the exergames.

Figure 3.

Example of guided-AR exercises with biofeedback in Homing device.

Figure 3.

Example of guided-AR exercises with biofeedback in Homing device.

Figure 4.

Example of motor-cognitive exercises with biofeedback in Homing device.

Figure 4.

Example of motor-cognitive exercises with biofeedback in Homing device.

Digital Device Description

Homing is a medical device for outpatient and home use, intended for the delivery of motor and postural activity programs/exercises. The device recognizes, via a single RGB camera and body tracking algorithm, the patient’s rehabilitation: therapists can dispense exercises that patients can execute autonomously (asynchronous), only controlling the final exercise results, or can connect remotely to patient, helping him/her during execution (synchronous). The module always provides visual and auditive biofeedback together with semi-immersive VR and AR modules to provide engaging and immersive training. A set of serious games specifically designed to perform virtual motor-cognitive exercises on a screen is also implemented in this device. These exercises are intended to cover all the cognitive abilities (attention, memory, working memory, fluency, reasoning, planning, spatial orientation, inhibition). Each module potentially combines motor and cognitive rehabilitation in a dual task training that can be balanced on the patient’s cognitive and motor skills. Therapists can choose if the execution of the motor-cognitive task is performed with the use of a remote control or with patient movement of upper-limb, lower-limb, trunk or COP, adapting the mode in accordance with the patient’s needs.

For improving the engagement each serious game is composed of different difficulty levels which can be selected by therapist or managed by a self-adjusting algorithm based on patient performance and perceptions.

Outcome

Both the experimental and control groups were assessed in parallel at baseline (T0), after 4 weeks of training (T1), after 12 weeks (T3), and after 24 weeks (T6). The assessment parameters for this study were selected, to the best of our knowledge, by reviewing the scales and tests most commonly used in the literature to evaluate improvement or stability in patients with MCI in terms of balance and functional performance, with particular attention to activities of daily living (ADL) and residual cognitive abilities. With reference to

Table 1, the outcomes are subdivided as described below.

Primary Outcome

The primary implementation endpoint is treatment adherence, assessed through the extent of participant engagement in the scheduled home-based activities. Adherence was calculated as the proportion of scheduled sessions completed and/or active minutes performed, complemented by platform-derived completion/quality indices and retention across the entire rehabilitation protocol. Higher values indicate better adherence/engagement with the intervention.

Global cognitive stability was assessed using the Addenbrooke’s Cognitive Examination–III (ACE-III) and the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) to verify non-worsening over time. The ACE-III is a 100-point battery assessing attention, orientation, memory, verbal fluency, language, and visuospatial abilities; the MMSE ranges 0–30. For both instruments, higher scores reflect better cognitive functioning; a non-inferiority framework will be adopted, with a pre-specified margin of acceptable change between T0 and T6.

Static and dynamic balance was evaluated with the Tinetti scale, which provides a reliable index of postural control and gait safety; higher scores indicate greater balance/gait ability and lower fall risk.

Caregiver outcomes were captured to reflect the dyadic nature of the intervention. The Caregiver Burden Inventory (CBI) (24 items, total 0–96) quantifies multidimensional burden (higher = worse). Emotional well-being was measured with the Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS-15) (higher = more depressive symptoms) and perceived loneliness with the UCLA Loneliness Scale (higher = greater loneliness). Perceived social support was assessed with the Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (MSPSS), divided into 3 subscales: Family, Friends, Significant/Particular People, where higher scores indicate greater support. The primary objective is stability or improvement of caregiver well-being (CBI, GDS, UCLA; MSPSS).

Secondary Outcomes

Functional independence is examined with the Barthel Index (BI), a 10-item measure of activities of daily living (ADL), widely used to estimate the amount of assistance required in basic mobility and self-care; higher scores denote greater independence. Cognitive domain profiles will be further detailed through the ACE-III subscales to explore whether stability at the total score level masks domain-specific gains (e.g., attention/orientation, memory, fluency, language, visuospatial). Where appropriate, responder analyses (e.g., no-decline thresholds for cognition; clinically meaningful improvements for balance/ADL) and dose-response explorations were conducted to relate adherence metrics to changes in balance, function, and cognition. Results will be presented as change from baseline (ΔT6-T0), with the direction of benefit explicitly indicated for each scale.

Sample Size of the Population

A total of 40 patients has been enrolled and an allocation ratio to the treatment and control group of 1:1. It means that study group is made up of 10 patients and 10 caregivers and control group is made by 10 patients and 10 caregivers with a mean age of 70.

Data Collection

Clinicians collected data pertaining to participation, clinical status, functional capacity, and motor performance (both primary and secondary outcomes) at each evaluation time-point (T0, T1, T3, T6). Adherence among the Study group will be automatically monitored via the Homing system.

3. Results

This non-inferiority study sought to identify the effects of a 24-week, home-based motor–cognitive training, compared with no training, on balance improvement and stability of cognitive functions among community-dwelling people with MCI.

Primary outcome indicators, such as treatment adherence, showed that 80% of patients exceeded 100% adherence relative to the planned target. A phase-by-phase evaluation indicated that the mean adherence exceeded the 100% threshold in both T0–T3 and T3–T6, being higher in the initial phase and slightly decreasing in the second. No indicators of reduced motivation or fatigue emerged in the final part of the treatment, confirming adherence stability over the entire follow-up.

Analysis of average program scores revealed values above 85% for both patients and caregivers, with temporal stability. These results suggest continuity and high execution quality of the motor–cognitive trainings.

Figure 5 shows the distribution of the number of programs completed per patient relative to the planned target of 48 programs:

Figure 5.

Adherence of programs.

Figure 5.

Adherence of programs.

With regard to global cognitive stability (cognitive, emotional, and relational impact of the intervention), quantitative analyses were conducted in both groups using the neuropsychological scales described above. Referring to

Table 2, which reports, for each scale used, the mean value at T0 and T6 for both the study and control groups, the T0–T6 outcomes indicate good feasibility and substantial cognitive stability, with mixed domain-level trends. MMSE remained essentially unchanged in both groups (study: 25.8→25.6; control: 25.7→26.6). ACE-III total tended to increase (study: 71.5→72.2; control: 73.6→79.0), with domain-specific variations: in the study group, increases were observed in language and visuospatial domains, memory remained stable, and a slight decrease was seen in attention–orientation and fluency; in the control group, memory and attention–orientation increased.

On the functional side, in the study group patients improved on Tinetti-E, were stable on Tinetti-A, and increased on the Barthel; in the control group, stability was observed on Tinetti-E, Tinetti-A, and Barthel.

Figure 6.

Tinetti Results.

Figure 6.

Tinetti Results.

Concerning psychosocial outcomes, average mood remained low: GDS increased slightly in the study group and decreased in the control group. The UCLA Loneliness Scale rose among patients in the study group and remained essentially stable in the control group; among caregivers, it decreased slightly in the study group and was essentially unchanged in the control group. In study-group caregivers, MSPSS increased in Family (20.8→22.6) and Particular People (18.2→19.3); in the control group, Family was stable and Particular People declined (20.2→19.4). Caregiver burden (CBI) worsened in the study group and improved in the control group. Overall, these exploratory (non-inferential) signals are compatible with a non-inferiority profile on global cognition, indicate functional benefits of home training, but also show nuanced psychosocial signals that require confirmation in larger samples. A positive effect is apparent from sharing the therapeutic pathway with one’s caregiver, as well as from the care engagement and the overall rehabilitation pathway.

Figure 7.

MSPSS Family and Particular people results.

Figure 7.

MSPSS Family and Particular people results.

4. Conclusions

The Tele Cognitive Movement (TCM) project showed that integrating motor–cognitive rehabilitation with home telerehabilitation, with the active involvement of the patient–caregiver dyad, can represent an innovative and sustainable model of care. The results indicate good adherence to the program and maintenance of cognitive and functional abilities in patients with MCI, accompanied by a perceived improvement in social and emotional support for both patients and caregivers.

At the same time, some administered scales showed a worsening in the study group that was not observed in the control group (GDS and UCLA Loneliness). This unexpected finding, in light of the consistency of functional and adherence indicators, may reflect methodological factors rather than a true negative effect of the intervention.

The qualitative analysis, conducted through focus groups, confirmed the added value of the dyadic approach and the crucial role of clinicians, underscoring the importance of the therapeutic relationship even in a digital context. Although some initial technical difficulties emerged, their resolution strengthened participants’ confidence in the project and its potential.

This preliminary data suggests that the use of devices such as Homing Training and the adoption of structured telerehabilitation models may contribute to improving the quality of life of people with MCI and their caregivers, while at the same time promoting greater efficiency in the health and social care system.

Further enlargement of the sample and continuation of longitudinal investigations will be required to strengthen the current evidence base, evaluate long-term effects, and examine the economic and organizational viability of the proposed model. Looking ahead, the TCM project represents an important opportunity to develop new welfare paradigms in which technology and human relationships are integrated to benefit frail individuals and their families.

A limitation of the present study is the small sample size. Future studies should include larger cohorts to enable robust statistical analyses and increase the power of the study.

Table 2.

Assessment Scale results.

Table 2.

Assessment Scale results.

References

- Petersen, RC. Mild Cognitive Impairment. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(23):2194–2202. [CrossRef]

- Casagrande M, Marselli G, Agostini F, et al. The complex burden of determining prevalence rates of mild cognitive impairment: a systematic review. Front Psychiatry. 2022;13:960648.

- Fabrizi E, et al. The Italian guideline on diagnosis and treatment of dementia and mild cognitive impairment. 2024. Linea guida nazionale basata su evidenze.

- Bacigalupo, Ilaria, Francesco Giaquinto, Emanuela Salvi, et al. ‘A New National Survey of Centers for Cognitive Disorders and Dementias in Italy’. Neurological Sciences 45, fasc. 2 (2024): 525–38. [CrossRef]

- Bacigalupo, Ilaria, Flavia Mayer, Eleonora Lacorte, et al. ‘A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis on the Prevalence of Dementia in Europe: Estimates from the Highest-Quality Studies Adopting the DSM IV Diagnostic Criteria’ Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease 66, fasc. 4 (2018): 1471–81. [CrossRef]

- Sachdev, Perminder S., Darren M. Lipnicki, Nicole A. Kochan, et al. ‘The Prevalence of Mild Cognitive Impairment in Diverse Geographical and Ethnocultural Regions: The COSMIC Collaboration’. PLOS ONE 10, fasc. 11 (2015): e0142388. [CrossRef]

- Dementia in Europe yearbook 2019: estimating the prevalence of dementia in Europe. Available online: https://www.alzheimer-europe.org/sites/default/files/alzheimer_europe_dementia_in_europe_yearbook_2019.pdf.

- Feng, Man, Jinxiu Li, Fen Xie, e Zhengying Chen. ‘The Relationship between Social Support, Cognitive Function and Activities of Daily Living in Older People: A Cross-Sectional Study’. Frontiers in Public Health 13 (giugno 2025): 1602466. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Chong, Juan Xiong, e Wenqi Luo. «The Relationship between Social Participation and Cognitive Function in Older Adults: The Mediating Role of Activities of Daily Living». Preprint, In Review, 2 febbraio 2024. [CrossRef]

- Jekel, Katrin, Marinella Damian, Carina Wattmo, et al. ‘Mild Cognitive Impairment and Deficits in Instrumental Activities of Daily Living: A Systematic Review’. Alzheimer’s Research & Therapy 7, fasc. 1 (2015): 17. [CrossRef]

- Chantanachai, Thanwarat, Daina L. Sturnieks, Stephen R. Lord, et al. Cognitive and Physical Declines and Falls in Older People with and without Mild Cognitive Impairment: A 7-Year Longitudinal Study. International Psychogeriatrics 36, fasc. 4 (2024): 306–16. [CrossRef]

- Hunter, Susan W. Opportunities for Falls Prevention in Older Adults with Mild Cognitive Impairment. International Psychogeriatrics 36, fasc. 4 (2024): 235–37. [CrossRef]

- Pecchinenda, Anna, Alla Yankouskaya, Maddalena Boccia, Laura Piccardi, Cecilia Guariglia, e Anna Maria Giannini. «Exploring the Relationship between Perceived Loneliness and Subjective Cognitive Decline in Older Individuals». Aging & Mental Health 28, fasc. 1 (2024): 73–82. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Guarnera, Jade, Eva Yuen, e Helen Macpherson. The Impact of Loneliness and Social Isolation on Cognitive Aging: A Narrative Review. Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease Reports 7, fasc. 1 (2023): 699–714. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Chenyi, Valentino Marcel Tahamata, Yi-Fang Chuang, et al. Perceived Loneliness Mediates the Relationship between Mild Cognitive Impairment and Executive Function Deficits. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications 12, fasc. 1 (2025): 991. [CrossRef]

- Borda MG, et al. Influencing factors on instrumental activities of daily living among older people with mild cognitive disorder. BMC Geriatrics. 2022;22:476.

- Canevelli M, et al. The patient–caregiver dyad: the impact of cognitive and functional impairment. Neurol Sci. 2022;43:2481–2490.

- Gomes F, et al. Effectiveness of combined cognitive stimulation and physical activity in older people with MCI: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Med. 2024;14(7):2261.

- Zhang X, et al. Cognitive and physical impact of combined exercise and cognitive training in older adults with MCI: systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2024;19(8):e0308466.

- Vásquez-Carrasco, Edgar, Celia Sánchez Gómez, Pablo Valdés-Badilla, et al. Effectiveness of Combined Cognitive Stimulation and Physical Activity Interventions on Activities of Daily Living, Cognitive Function, and Physical Function in Older People with Mild Cognitive Impairment: A Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis. Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, fasc. 7 (2025): 2261. [CrossRef]

- Castellote-Caballero, Yolanda, María Del Carmen Carcelén Fraile, Agustín Aibar-Almazán, Diego Fernando Afanador-Restrepo, e Ana María González-Martín. Effect of Combined Physical–Cognitive Training on the Functional and Cognitive Capacity of Older People with Mild Cognitive Impairment: A Randomized Controlled Trial. BMC Medicine 22, fasc. 1 (2024): 281. [CrossRef]

- Maggio, Maria Grazia, Francesca Baglio, Francesco Arcuri, et al. Cognitive Telerehabilitation: An Expert Consensus Paper on Current Evidence and Future Perspective. Frontiers in Neurology 15 (febbraio 2024): 1338873 . 2024. [CrossRef]

- Chang, Ya-Ting. Physical Activity and Cognitive Function in Mild Cognitive Impairment. ASN Neuro 12, fasc. 1 (2020): 1759091419901182. [CrossRef]

- Tan, L.F., Y.H. Chan, S. Seetharaman, et al. Impact of Exercise and Cognitive Stimulation Therapy on Physical Function, Cognition and Muscle Mass in Pre-Frail Older Adults in the Primary Care Setting: A Cluster Randomized Controlled Trial. The Journal of Nutrition, Health and Aging 27, fasc. 6 (2023): 438–47. [CrossRef]

- Rieker, Jennifer A., José M. Reales, Mónica Muiños, e Soledad Ballesteros. The Effects of Combined Cognitive-Physical Interventions on Cognitive Functioning in Healthy Older Adults: A Systematic Review and Multilevel Meta-Analysis. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience 16 (marzo 2022): 838968. [CrossRef]

- Lopes J, et al. Cognitive telerehabilitation in older adults: a systematic review of RCTs. Front Neurol. 2024;15:1450977.

- Park J, et al. Effects of VR-based physical and cognitive training in older adults with MCI: randomized controlled trial. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2023.

- Mikołajewska E, et al. Neurotechnological approaches to cognitive rehabilitation in MCI: systematic review. Brain Sciences. 2025;15(6):582.

- Jeon, Hyeonwoo, Doo Young Kim, Si-Woon Park, et al. A Systematic Review of Cognitive Telerehabilitation in Patients with Cognitive Dysfunction. Frontiers in Neurology 15 (gennaio 2025): 1450977. [CrossRef]

- Maggio, Maria Grazia, Francesca Baglio, Francesco Arcuri, et al. Cognitive Telerehabilitation: An Expert Consensus Paper on Current Evidence and Future Perspective. Frontiers in Neurology 15 (febbraio 2024): 1338873. [CrossRef]

- Md Fadzil, Nurul Hidayah, Suzana Shahar, Roslee Rajikan, et al. A Scoping Review for Usage of Telerehabilitation among Older Adults with Mild Cognitive Impairment or Cognitive Frailty. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, fasc. 7 (2022): 4000. [CrossRef]

- Realdon, O., F. Rossetto, M. Nalin, et al. Technology-Enhanced Multi-Domain at Home Continuum of Care Program with Respect to Usual Care for People with Cognitive Impairment: The Ability-TelerehABILITation Study Protocol for a Randomized Controlled Trial. BMC Psychiatry 16, fasc. 1 (2016): 425. [CrossRef]

- Domingues, Nélia Sofia, Phylicia Verreault, e Carol Hudon. Reducing Burden for Caregivers of Older Adults With Mild Cognitive Impairment: A Systematic Review. American Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease & Other Dementias® 33, fasc. 7 (2018): 401–14. [CrossRef]

- Paggetti, Alice, Ylenia Druda, Francesco Sciancalepore, et al. The Efficacy of Cognitive Stimulation, Cognitive Training, and Cognitive Rehabilitation for People Living with Dementia: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. GeroScience 47, fasc. 1 (2024): 409–44. [CrossRef]

- R. A., & L. T. D. Schmidt, Motor control and learning: A behavioral emphasis., 5th ed., vol. Human Kinetics. 2011.

- P. Mazzoni and J. W. Krakauer, “An implicit plan overrides an explicit strategy during visuomotor adaptation,” Journal of Neuroscience, vol. 26, no. 14, pp. 3642–3645, Apr. 2006. [CrossRef]

- S. K. Subramanian, C. L. Massie, M. P. Malcolm, and M. F. Levin,‘Does provision of extrinsic feedback result in improved motor learning in the upper limb poststroke? a systematic review of the evidence,’ Neurorehabilitation and Neural Repair, vol. 24, no. 2. pp. 113–124, Feb. 2010. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).