Submitted:

28 March 2024

Posted:

29 March 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Site

2.2. Soil Sampling and Chemical Characterization

- Soil samples (three replicate plots (plot size, 5 by 20 m, composed by non-inoculated plants), obtained in February (rainy period) and November 2015 (after the dry period) at the site, were used for determination of chemical soil parameters (Embrapa, 1997) and for AMF spore extraction. For physical and chemical soil analysis a composite sample from soil of each sampled point at each season was prepared. In total 9 soil samples from grassland ecosystem weighing about 0.5–1 kg each were transported to the laboratory using sealed plastic bags, For determination of chemical soil parameters (Embrapa, 1997).

2.3. AMF Spore Isolation and Identification

2.4. Microcharcoal Content

3. Results

4. Discussion

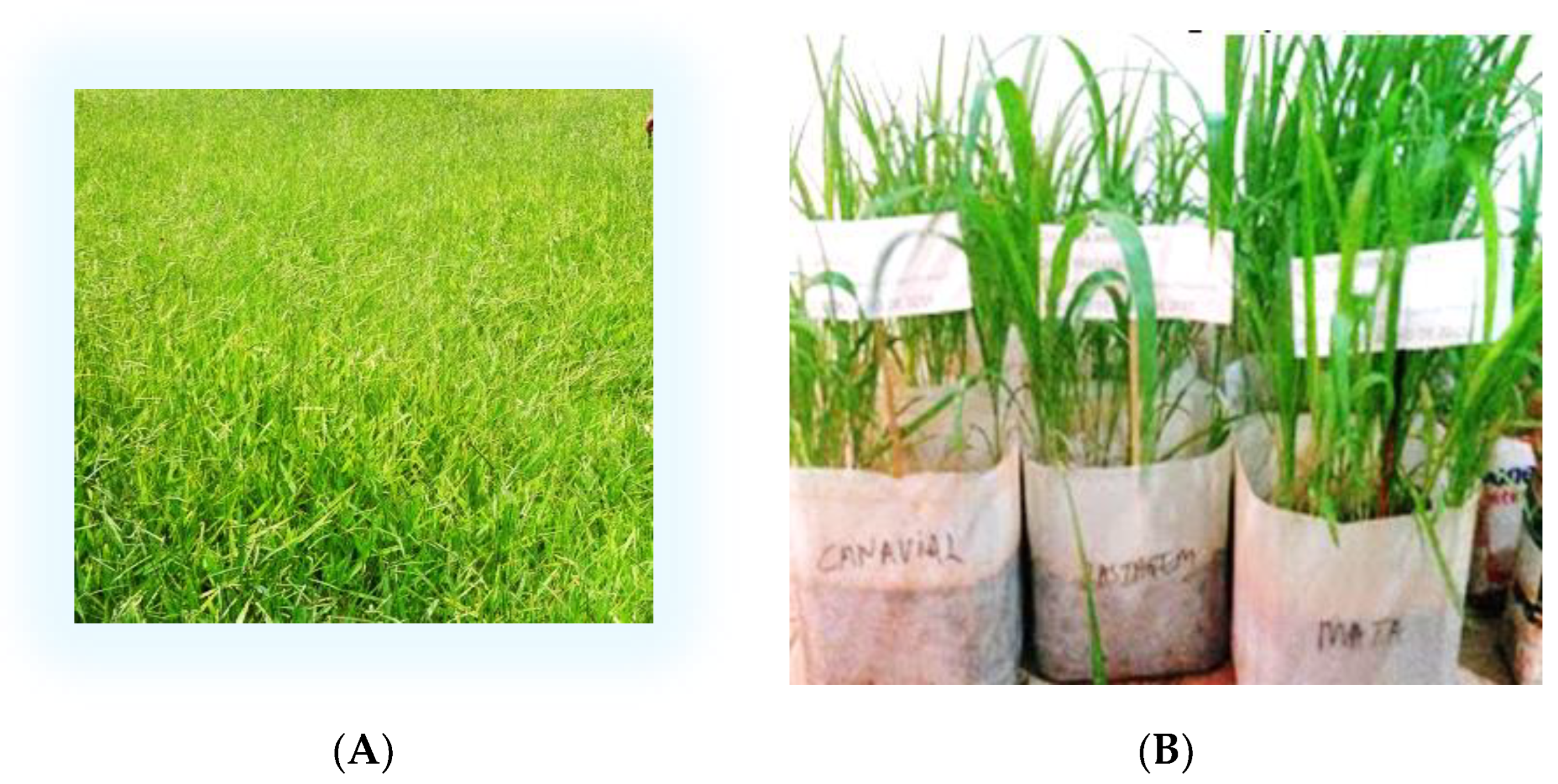

4.1. Urochloa Species for Cover Crops

4.2. Urochloa Species for AMF Studies

4.3. Urochloa Species for Carbon Mitigation

4.4. Urochloa Species for Forage

4.5. Urochloa for Revegetation

4.6. Fertilization and Soil Amendments for Urochloa

4.6.1. Fertilization

4.6.2. Soil Amendments

5. Genetics of Urochloa Species

5.1. Inoculation of Urochloa Species

6. Conclusions

Declarations

Availability of data and material

Competing Interest

Consent for publication

Competing interests

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgements

References

- Lambers, H, Cong, W-F. 2022. Challenges Providing Multiple Ecosystem Benefits For Sustainable Managed Systems. Front. Agr. Sci. Eng., 9 (2) 170-176. [CrossRef]

- Pagano Kyriakides, M. , Kuyper, TW. 2023.Effects of Pesticides on the Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Symbiosis. Agrochemicals 2, 2. 10.3390/agrochemicals2020020.

- Goldan, E. ; Nedeff, V, Barsan, N.,Culea,M. Panainte-Lehadus, M, Mosnegutu,E.,Tomozei,C., Chitimus, Irimia, D. 2023. Assessment of Manure Compost Used as Soil Amendment—A Review. Processes, 11(4), 1167. [CrossRef]

- dos Santos Lucas, L. , Rubio Neto, M.A. de Moura, J.,B. Fernandes de Souza, R., Fernandes Santos, M E.; Fernandes de Moura, L, Gomes Xavier, E. J M dos Santos, J.M., Dutra Silva, R. N. S. 2022 Mycorrhizal fungi arbuscular in forage grasses cultivated in Cerrado soil.2022. Sci Reports, 12:3103. [CrossRef]

- Alves Teixeira, R. Gazel Soares, T. Rodrigues Fernandes, A. Martins de Souza Braz, A. 2014. Grasses and legumes as cover crop in no-tillage system in northeastern Pará, Brazil, Acta Amaz. 44 (4). [CrossRef]

- Baptistella, J.L.C.; Bettoni Teles, AP. Favarin J, Mazzafera, P. 2022 Phosphorus cycling by Urochloa decumbens intercropped with coffee. Experimental Agriculture, 58, 2022, e36.

- Baptistella, JLC; de Andrade SAL., Favarin,JL. Mazzafera,P..2020. Urochloa in Tropical Agroecosystems., Frontiers in Sustainable food systems, 4, 119.

- Barbosa, M. V. , Pedroso, D. de F.,F. Araujo Pinto, J. dos Santos V; Carbone Carneiro, M.A. 2019. Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi and Urochloa brizantha: symbiosis and spore multiplication. Pesquisa Agropecuaria Tropical 49, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 9. Gerdemann JW, Nicolson TH (1963) Spores of mycorrhizal Endogone species extracted from soil by wet sieving and decanting. Trans Br Mycol Soc, 46: 235–244.

- Varga, S. , Finozzi, C., Vestberg, M., K Arctic arbuscular mycorrhizal spore community and viability after storage in cold conditions. Mycorrhiza 25. 335–34.

- Stevenson, J. , Haberle, S., 2005. Macro Charcoal Analysis: a Modified Technique Used by the Department of Archaeology and Natural History. Palaeoworks Technical Papers, p. 5.108.

- Pagano, MC; Duarte, NF., Corrêa, EJA. 2020. Effect of crop and grassland management on mycorrhizal fungi and soil aggregation. Applied Soil Ecol, 147. 103385.

- Kanno, T. M. Saito M, Y. Ando, M.C.M. Macedo, Nakamura, T. Miranda C.H.B 2006. Importance of indigenous arbuscular mycorrhiza for growth and phosphorus uptake in tropical forage grasses growing on an acid, infertile soil from the Brazilian savannas. Tropical Grasslands, (2006. 40, 94–101.

- Pedroso, D., Barbosa, M.V., dos Santos, J.V. et al. (2018). Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi favor the Initial Growth of Acacia mangium, Sorghum bicolor, and Urochloa brizantha in Soil Contaminated with Zn, Cu, Pb, and Cd. Bull Environ Contam Toxicol 101, 386–391. [CrossRef]

- Rillig 2004. Arbuscular mycorrhizae, glomalin, and soil aggregation. Canadian Journal of Soil Science. [CrossRef]

- Selvakumar, G. Shagol, C.C. Y. Kang, Y, Chung B.N., Han S.G., T.M. S. 2018. Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi spore propagation using single spore as starter inoculum and a plant host. Journal of Applied Microbiology, 124, 6,2018, 1556–1565.

- Lehmann, A. , Leifheit, E.F. Rillig, M.C. 2017, Chapter 14–Mycorrhizas and Soil Aggregation. Mycorrhizal mediation of soil, In: Fertility, Structure, and Carbon Storage. pp. 241-262.

- Hossain, M.B. Contribution of Glomalin to Carbon Sequestration in Soil: A Review. Turkish Journal of Agriculture-Food Science and Technology, 9,1: 191-196, 2021.

- Wang, FEI Lu, X B Han, Z Ouyang, X Duan. Soil carbon sequestrations by nitrogen fertilizer application, straw return and no-tillage in China’s cropland. Global Change Biology, 2009 15, 2 p. 281-305.

- Pagano, MC, Correa, EJA, Lugo, MA, Duarte, NF.2022. Diversity and Benefits of Arbuscular Mycorrhizae in Restored Riparian Plantations. Diversity, 14(11), 938. [CrossRef]

- Follett, R.F. , Reed D.A. Soil Carbon Sequestration in Grazing Lands: Societal Benefits and Policy Implications. Rangeland Ecology & Management 63, 1, 2010, 4-15.

- Lal, 2008. Sequestration of atmospheric CO2 in global carbon pools Energy and environmental Science, 1, 86-100.

- Luo, Y. , ZHOU, X. Soil respiration and the environment. San Diego, Elsevier, 2006. 316p.

- ZhaoY., Yuqiang Tian, Y., Gao, Q., Xiaobing Li, X., Yong Zhang,, Ding, Y. Ouyang, S, Andrey Yurtaev, A., Kuzyakov, Y. Moderate grazing increases newly assimilated carbon allocation belowground. Rhizosphere, 22, 2022, 100547.

- Ontl, T. A. and Schulte, L. A. (2012) Soil Carbon Storage. Nature Education Knowledge, 3(10-35).

- Wilson, CH, Strickland, MS, Hutchings, JA. 2018. Grazing enhances belowground carbon allocation, microbial biomass, and soil carbon in a subtropical grassland, Global change Biol. 24(7):2997-3009.

- Qu T-b, Du W-c, Yuan X, Yang Z-m, Liu D-b, Wang D-l, et al. (2016) Impacts of Grazing Intensity and Plant Community Composition on Soil Bacterial Community Diversity in a Steppe Grassland. PLoS ONE 11(7): e0159680.

- Hafner, S. , Unteregelsbacher, S. Seeber, E.2012. Effect of grazing on carbon stocks and assimilate partitioning in a Tibetan montane pasture revealed by 13CO2 pulse labeling. Global Change Biology, 18, 2,528-538.

- Vandandorj, S.; Eldridge, D.J; Travers, S.; Oliver, I. Microsite and grazing intensity drive infiltration in a semi-arid woodland. Ecohydrology . 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feltran-Barbieri R, Féres JG. 2021. Degraded pastures in Brazil: improving livestock production and forest restoration. R. Soc.

- Open Sci. 8: 201854. [CrossRef]

- Tomaszewska, P. Vorontsova, M.S. Renvoize, S A. Ficinski, S.Z.Tohme, J. Schwarzacher, T. Castiblanco V., de Vega, J. J. Rowan A. C. Mitchell, Heslop-Harrison, J. S. Complex polyploid and hybrid species in an apomictic and sexual tropical forage grass group: genomic composition and evolution in Urochloa (Brachiaria) species. Annals of Botany, 131: 87–107, 2023.

- da Silva, LHX, · Okada, E.S.M, Soares, J.P. ·G. Oliveira, E.R. ·Gandra, J.R. · Costa Marques, O.F. · Neves, N. F., J.T.S. Gabriel, A.M A.. 2021. Organic management of Urochloa brizantha cv. Marandu intercropped with leguminous. Org. Agr. 11:539–552.

- Macedo, M.C.M. 1995. Pastagens no ecossistema Cerrados: Pesquisa para o desenvolvimento sustentavel. In: Simposio sobre pastagens nos ecossistemas Brasileiros: pesquisa para o desenvolvimento sustentavel. Anais. pp. 28–62. (Sociedade Brasileira de Zootecnia: Brasilia-DF, Brazil).

- Miguel, P. , Stumpf, L., Spinelli Pinto, L.F., Pauletto, E.A., Rodrigues, MF., Barboza,LS. Jéferson D., Leidemer, Duarte, B.T., M. A.B. Brito Pinto, B. G. Fernandez, M. Livia Oliveira Islabão, Silveira, LM., Peroba Rocha, J.V. Physical restoration of a minesoil after 10.6 years of revegetation. Soil and Tillage Research 227, 2023, 105599.

- Santos, A.L. De-Souza, F.A,. Berbara, R.L.L.; Guerra, J.G.M. 2000. Establishment and infective capacity of Gigaspora margarita Becker & Hall and Glomus clarum Nicol. & Gerd. in eroded soil. Acta bot. bras. 14(2): 127-139.

- Barbero, R.P., Ribeiro, A, C. , A. Moura , Zirondi V.L. , T. Almeida, T.F. Mattos A., MM. Barbero. 2021. Production potential of beef cattle in tropical pastures: a review. Animal Science. Ciênc. anim. bras. 22 . DOI: 10.1590/1809-6891v22e-69609.39. Lustosa Filho, J.F., Silva Carneiro, J.S. Barbosa, C.F, Pereira de Lima, K. , Amaral Leite, A. Azevedo Melo, LC. 2020. Aging of biochar-based fertilizers in soil: Effects on phosphorus pools and availability to Urochloa brizantha grass. Science of The Total Environment 709, 2020, 136028.

- Ferreira, R.C U., Moraes, ACL., Chiari, L., R. M. Simeão, Zanotto, BB. Vigna de Souza A,P. 2021. An Overview of the Genetics and Genomics of the Urochloa Species Most Commonly Used in Pastures Front. Plant Sci., 2021Sec. Plant Breeding 12–2021 |. [CrossRef]

- Basiru, Hijri, 2022. The Potential Applications of Commercial Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungal inoculants and Their Ecological Consequences. Microorganisms 10, 10 10.3390/microorganisms10101897.

- Vahter, T; Lillipuu, E.M. Oja, J. Öpik,M. Vasar, M. Hiiesalu, I. Do commercial arbuscular mycorrhizal inoculants contain the species that they claim? Mycorrhiza, 2023 33,3,:211-220. [CrossRef]

- Martins, C. R., Leite, L.L. Haridasan, M. 2001. The use of native grasses in the reclamation of an area degraded by gravel mining. R. Árvore, 25, 2, 157-|66.

- Karti, P D M H, Prihantoro I, Aryanto, A.T. Evaluation of inoculum arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi in Brachiaria decumbens. International e-Conference on Sustainable Agriculture and Farming System, IOP Conf. Series: Earth and Environmental Science 694 (2021) 012048, IOP Publishing. [CrossRef]

| Vegetation / Field/ greenhouse | Plant species | Geographical coordinates | Altitude (m asl) | Estimated age of cultivation (year) | AMF species/Glomalin | State | Reference [8] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Field |

U. brizantha U. decumbens |

- - - |

Experimental Station of the Cerrado |

Diversispora sp., Scutellospora sp. Glomus sp. Gigaspora sp. | GO | [4] | |

| Greenhouse | U. brizantha | 19°42’51.5”S 44°53’37.0”W | 628,36 | >10 | A. colombiana, A. longula/ + | MG | [8] |

| U. brizantha | - | NA | SP | [7] * | |||

| U. brizantha | 48°26′W; 22°51′ S |

740 | NA | SP | [13] + |

| pH (H2O) | 5.4 | ||

| OC (dag kg−1) | NA | ||

| Ca (cmolc kg−1) | 1.5 | ||

| Mg (cmolc kg−1) | 0.9 | ||

| Al (cmolc kg−1) | 0.7 | ||

| Available K mg⋅kg−1 | 43 | ||

| Available P mg⋅kg−1 | 1.8 | ||

| Soil texture | Clayey- loam | ||

| Charcoal content# | 19.66 |

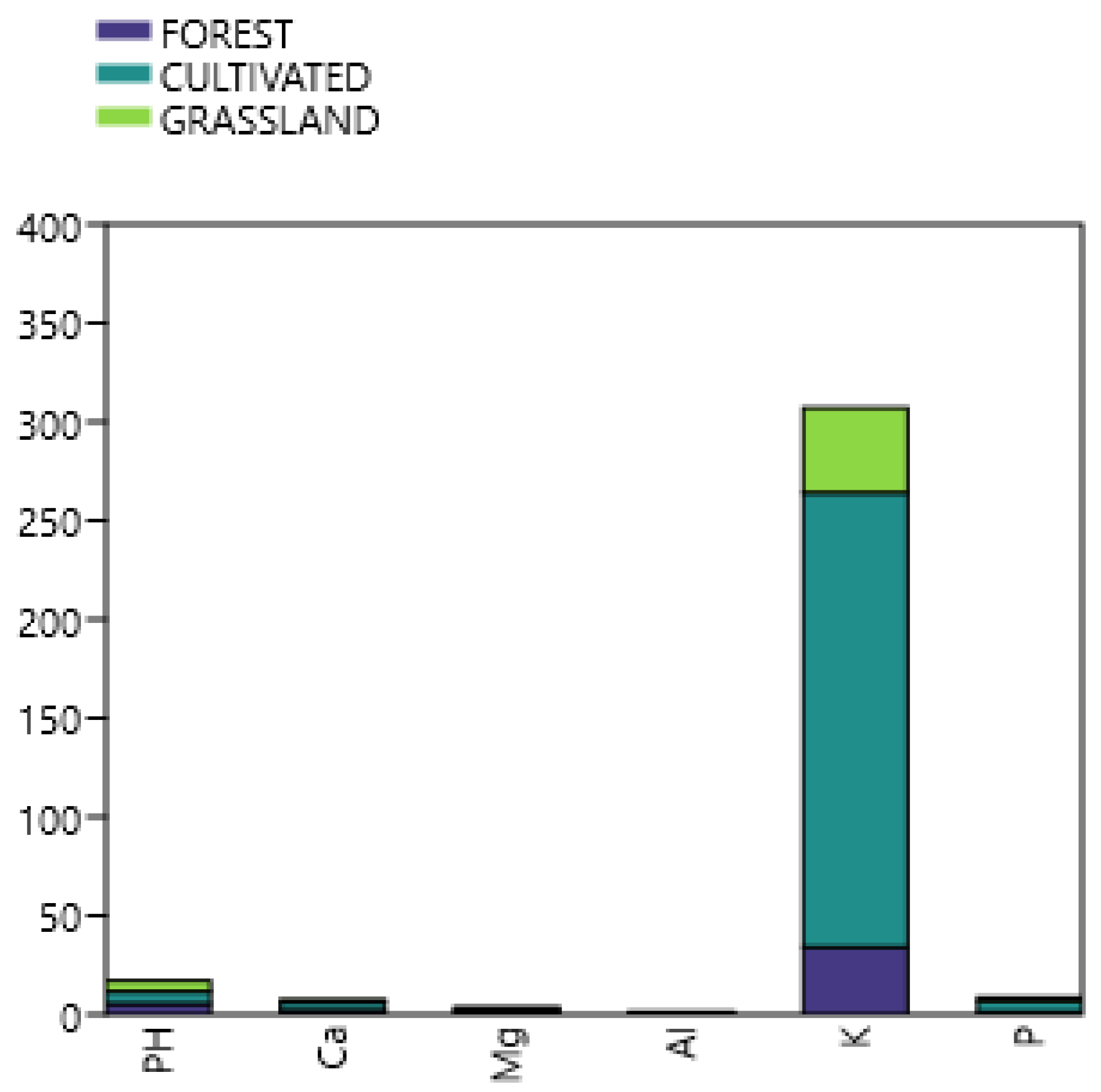

| Soil depth (0-20 cm) | |||||

| Forest | Cultivated | Grassland | |||

| pH (H2O) | 5.4ns | 6.2 | 5.4 | ||

| C (g kg-1) | - | - | - | ||

| Ca (cmolc kg-1) | 2b | 4.1a | 1.5 b | ||

| Mg (cmolc kg-1) | 0.8b | 2a | 0.9 b | ||

| Al (cmolc kg-1) | 0.5ns | 0.1 | 0.7 | ||

| K mg⋅kg-1 | 34b | 230a | 43b | ||

| P mg⋅kg-1 | 1.4c | 5.4a | 1.8 b | ||

| AMF species | ||||||||||

| Dentiscutataceae | ||||||||||

| Dentiscutata heterogama | ||||||||||

| Claroideoglomeraceae | ||||||||||

| Claroideoglomus etunicatum | ||||||||||

| Racocetraceae | ||||||||||

| Racocetra fulgida | ||||||||||

| Glomeraceae | ||||||||||

| Funneliformes geosporus | ||||||||||

| Glomus sp. 1 | ||||||||||

| Glomus sp. 2 | ||||||||||

| Type greenhouse |

Plant species | Soil Treatment (pH) | Non-inoculated | Inoculated | Reference | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| U. brizantha | - | 15.6 11.5 |

50.8 44.4 |

[8] [8] |

|||

| Field |

U. decumbens U. humidicola U. ruziziensis |

- | 78 5566 |

- | [4] [4] [4] |

||

| U. brizantha | - | 3 532 27 16 |

[4] [5] [5] [5] |

||||

|

U. decumbens U. humidicola P maximum |

10.4 - |

52.2 33.2 |

[13] [13] [13] |

||||

| Glasshouse | U. brizantha | High Medium Low |

D 49.7 00 31.4 | 54.3 49.7 31.4 |

[8] [8] [8] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).