1. Introduction

Lubricating oil, as the largest lubricant used in the world, is an indispensable material for equipment operation. The proportion of base oil in lubricating oil is usually more than 85%. For a long time, crude oil has been produced various lubricant base oils [

1]. Limited by crude oil quality and production process factors, it is difficult for China to produce API III and IV high-quality base oils through crude oil [

2]. Recently, utilized abundant coal resources, the Chinese company realized the conversion of coal into lubricant base oil (CTL) through a coal indirect liquefaction technology route which was similar to that of Shell GTL base oil (gas-to-liquid)[

3]. CTL and GTL are also known as Fischer Tropsch(F-T) synthetic base oil due to their similar process. And the PAO base oil is obtained by polymerization of alpha olefins in indirect coal liquefaction products. At the same time, α-olefins may also be used to prepare other API V base oils or lubricant additives[

4].

Different from the traditional petroleum base oil performance has been fully studied [

5,

6,

7,

8] , the researches on CTL base oil are relatively less. CTL base oil has the characteristics of high viscosity index, low evaporation loss, and no sulfur, nitrogen and aromatic hydrocarbons [

9]. CTL base oil can reach the level of PAO in terms of Noack volatility, antioxidant properties, and thermal stability, while PAO only maintains certain advantages in extreme low-temperature fluidity. The excellent physical and chemical properties of CTL base oil make it show good application prospects in emerging fields such as electric vehicles, power batteries, data center direct liquid cooling and so on.

The additives as components to improve or compensate the performance of base oil. Adding suitable lubricating oil additives to CTL can give full play to its performance advantages. The sensitivity of base oil to additives is directly related to the use effect and economy of base oil. Hui et al. [

10] studied the oxidation stability of CTL base oil by PDSC method. It showed that the oxidation stability and sensitivity to antioxidants of CTL base oil are between API III and IV. For GTL base oil, An et al. [

11] and Liang et al. [

12] studied the sensitivity of antioxidant and antiwear additive of GTL. However, there is still a lack of performance comparison between petroleum base oil and PAO. Based on the performance characteristics of CTL, relatively more researchs focus on the application of CTL base oil, such as rolling[

13], gasoline engine[

14] and diesel engine[

15], which has promoted the practical application of CTL base oil. While, the structure and composition of base oil are the internal factors that affect its performance. However, there is currently limited research on CTL at the molecular scale. To reveal the relationship between the structure of CTL base oil and viscosity index from a molecular perspective, Zhang et al. [

16] characterized the molecular structure using 13C NMR spectrums. From the correlation analysis, normal paraffins, average chain length, and 6- or 7-methyl-substitutedare are the key factors for the high viscosity index of CTL base oils. And the increase of other branched-chain structure contents will reduce the viscosity index. For the oxidation resistance of CTL, Yu et al. [

17] studied the effect of antioxidant additives on the thermal oxidation performance of CTL base oil by test and molecular dynamics simulation. As known, CTL, GTL, and API III base oil are all hydrogenated isomeric base oils. While, the differences between CTL base oil and other base oils from a molecular perspective are still in the blank. Therefore, it is of great scientific significance to study the relationship between the structure and properties of different base oils.

PAO base oil has excellent comprehensive performance. At present, the research on PAO base oil prepared from coal based

-olefin is mainly carried out in the aspects of polymerization process and laboratory product performance. Wu et al. [

18,

19] investigated the process conditions for synthesizing low viscosity PAO base oil with coal based

-olefin using AlCl

3 as a catalyst. The authors[

20] and Ma et al. [

21,

22] designed a new metallocene catalyst. It is the first in the world to prepare low viscosity metallocene PAO (mPAO) base oil from coal based alpha olefins. The properties of mPAO8 synthesized in the laboratory were preliminarily studied. The results showed that the oxidation stability, antioxidant sensitivity, pour point and Noack evaporation loss of mPAO8 were similar to those of commercial products. MPAO8 has high viscosity index, flash point and thermal stability. Antioxidant can significantly improve the antioxidant activity of mPAO8.

Coal based CTL and mPAO base oils are new high-quality base oils prepared with new raw materials and new processes. It is the key to realize the rational utilization of coal based base oil to clarify its composition, structure and performance differences from the traditional mineral based API III and IV base oils. However, it is regrettable that there is no systematic and comprehensive research and comparison between coal based base oil and traditional base oil. Meanwhile, the current research on coal based low viscosity mPAO base oil is limited to the performance research of laboratory synthetic products. During the industrialization of catalytic process, the enlargement of reaction vessel will affect the polymerization process, which will affect the performance of mPAO base oil. Therefore, it is necessary and meaningful to study the commercial coal based low viscosity mPAO.

In this work, 4.0cSt coal based CTL and mPAO base oil, GTL base oil, and typical commercial petroleum based API III and IV base oils with the same viscosity were selected as the research objects. The composition and structure of the above base oils were characterized by NMR, GPC and GC. And try to establish the relationship between the structure and performance of base oil. At the same time, the physicochemical properties, lubricating properties, oxidation stability and sensitivity to typical antioxidants and extreme pressure antiwear agents of the above base oils were compared,which is help for better understanding the performance characteristics of CTL and mPAO base oils made from coal, and guiding their subsequent research and application.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

Five low viscosity base oils with viscosity of 4.0cSt were selected as the representative base oils from different raw materials. CTL4 is the coal based hydroisomerization base oil. The mPAO4 base oil is a low viscosity PAO4 base oil industrially produced by polymerization of coal-based C10 α-olefin with metallocene catalyst.

Figure 1 is a schematic diagram of the process route for CTL4 and mPAO4.

Compared with CTL4, Shell's natural gas based lube base oil GTL4 and petroleum based API III oil YU4 were selected. For comparison with mPAO4, commercially available PAO4-M was prepared from petroleum-based C10 α-olefin polymerization.

As shown in

Table 1, 3 typical commercial antioxidants were selected for the experiment, namely thioester (AO1), phenolic (AO2) and arylamine (AO3) antioxidants. They were added to the test oils at 0.5 wt % to investigate the sensitivity of different base oils to antioxidants. Sulfide isobutylene (EP), alkyl phosphate (AW1), ZDDP (AW2) and alkyl phosphate amine salt (AW3) were selected as typical representatives of extreme pressure antiwear agents. The differences in the sensitivity of different base oils to typical extreme pressure antiwear agents were investigated at 1.0wt%.

2.2. Structural characterization of base oil

Gas chromatography was used to test the component distribution of 5 base oils. The gas chromatograph (GC) instrument model is Agilent HP-7890B. The detector is a hydrogen ion flame detector. The procedure for temperature heating process is as follows: firstly, it is constant at 50 °C for 2 min, then it rises to 350 °C with a rate of 5 °C/min and keeps at 350 °C for 30 min.

Gel permeation chromatography (GPC) was used to characterize the molecular weight distribution of 5 base oils. The instrument model is Viscotek GPC-MAX. An automatic sampler with a fixed 200 μL volume variable spray syringe was used. The syringes were cleaned twice with solvent before each sampling. The detector and autosampler were controlled by a Dell computer running Omnisec 4.2 software.

The 13C and

1H NMR spectra were recorded on a Zhongke Niujin WNMR-I 400 NMR spectrometer operating at 400.17 MHz for 1H and 100.62 MHz for 13C using a multinuclear 5 mm probe [

23]. Solutions of base oil (50 wt%) were prepared in CDCl3 containing 10% Tetramethylurea (TMU). The testing conditions for

13C NMR spectra are pulse width 3.1μs. Chamfer angle 30°, spectral width 11160.7Hz, observed nuclear resonance frequency 400MHz, sampling time 1.0s, delay time 5s, sampling frequency 5k, deuterated chloroform lock-in. Quantitative

13C NMR spectra were recorded under reverse gated conditions .

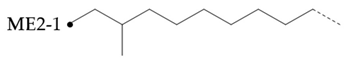

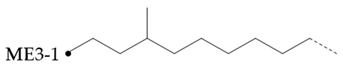

According to the

1H NMR spectrum and integral curve, the area integration counts of proton peaks of methyl (-CH

3), methylene (-CH

2), and secondary methyl (-CH) were calculated to obtain the branching degree BI of the specimen. The branching degree (BI) was calculated according to the following formula:

In the formula, is the methyl proton peak(:0.2-0.85) area; is the proton peak of methylene and methylene(:0.85-2.4)area integral count.

Assuming that all base oils have only short methyl or ethyl branching, the isomeric carbon atoms have an effect on the chemical shifts of the four nearby carbons. In combination with reference [

24], the types of carbon atoms in base oil molecules corresponding to

13C NMR chemical shifts are classified. To ensure accurate and proportional integration, normalize all signals in all

13C NMR with the signal of TMU methyl at 38.41ppm as 100, and integrate the spectrum according to the chemical shifts listed in

Table 2. The integral area of each peak was normalized by the peak of TMU methyl at 38.41ppm as 1.0.

The amount of long unbranched carbon in base oil molecules can be estimated by signals from unbranched carbon. The long linear chain itself (BL) requires that the carbon be surrounded by at least three unbranched CH

2 carbon in two directions. In addition, S3 signal can be used to indicate the long unbranched end chain, because it requires at least 6 nearby carbons to be unbranched. Therefore, the amount of long unbranched carbon segments can be calculated by the following formula:

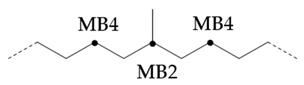

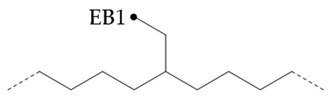

By integrating the characteristic methyl region (

:19.0~20.5), the number of methyl branched chains inside the carbon chain can be easily determined, which includes all methyl branched chains on the carbon chain. Therefore, the signal of methyl branched chain (

)in all base oils can be calculated by the following formula:

Since there should be no longer branched chains than ethyl, the total signal (

) of all branched chains can be easily determined by adding the signals

of ethyl branched chains:

Then the percentage of carbon chain methylation branches

:

The methyl branched chain at the end of the chain(

)can be estimated by adding the signals from all me series structures:

For the methyl branch chain in the middle of the chain, it can be represented by

. The methyl branch position can be expressed by calculating the percentage of methyl branch at the end of base oil molecule:

If a branch (or any other structure) is close enough to the methyl branch (MB Series) in the carbon chain, it will change the chemical shift of the adjacent carbon from the farthest carbon (MB5). With the change of chemical shift, the signals from these carbons are not included in the MB Series integral. This also means that the change of MB Series signal strength can indirectly detect the presence of nearby structures. For example, if a structure is close enough to change the displacement of MB4 without changing the displacement of MB2, the amount of MB4 signal observed is less than that of MB2 signal. Ideally, the ratio of MB2 and mb4 signals should be 1:2 (due to symmetry, each MB2 carbon corresponds to two MB4 carbon), so any change in this ratio can be attributed to nearby interference structures, and it is not even necessary to know the exact structure involved. This can be expressed as calculating the "lost" mb4 signal as a percentage of the MB2 signal:

Therefore, this parameter represents the possibility of the existence of a structure near the methyl branch, and can be considered as measuring the "purity" of the methyl branch: a lower value means that the methyl branch is well separated from other structures, while a higher value indicates that in many cases, there are methyl branches or other structures nearby

2.3. Physicochemical property

Standard methods such as ASTM D445, ASTM D2270, ASTM D92, ASTM D5950, ASTM D5293, and ASTM D5800 were used to test the kinematic viscosity, viscosity index(VI), flash point, pour point, -30 ℃ low-temperature dynamic viscosity(CCS), and NOACK evaporation loss of base oils, in order to compare the physicochemical properties of different base oils.

2.4. Oxidation stability

The oxidation stability of base oil and antioxidant containing samples was measured using a Pressurized differential scanning calorimetry (PDSC) from Switzerland's METTLER TOLEDO company. Measure the initial oxidation temperature (IOT) of oil products using the programmed heating method. The test conditions are: heating rate of 10 ℃/min, oxygen pressure of 3.5MPa, oxygen flow rate of 100mL/min, open aluminum dish diameter of 6mm, sample size of 3.0mg, and the initial oxidation temperature is taken as the temperature of severe oxidation of the oil. ASTM D6186 constant temperature method was used to determine the oxidation induction time (OIT) of oil products. The test conditions are: constant temperature of 160 ℃, oxygen pressure of 3.5MPa, and oxygen flow rate of 100mL/min. Test the time for the oil to undergo severe oxidation under this temperature condition.

The Rotary Bomb Oxidation Test (RBOT) was tested using P/N15200-3 from SETA in the UK. For base oil, the use of copper wire and water in ASTM D2272 method has a significant catalytic effect on the oil, resulting in insignificant differences in test results between different oils. Considering that there is often contact with metallic iron during the actual translation process, this article has improved the ASTM D2272 method. The specific improvement method is to replace the copper wire in ASTM D2272 method with a steel ball, which is made of bearing steel in accordance with GB/T 308.1-2013 medium high carbon chromium bearing steel ball, with a diameter of 12.7mm and no longer adding water as a catalyst in the projectile. The projectile is oxygenated at a pressure of 620kPa, tested at a temperature of 150 ℃, and rotated at a speed of 100r/min. The time from the beginning of the experiment to a pressure drop of 175kPa is the RBOT oxidation induction period.

2.5. Friction and wear test

The friction and wear performance of different base oils and oils containing extreme pressure antiwear additives were tested using a four balls friction tester. The instrument used in the experiment is the MS-10A lever type four balls friction testing machine, with a maximum speed of 3000rpm. The experimental steel ball is GCr15 steel ball produced by Falex Company in the United States, with an average hardness of 66.1 HRC and a diameter of 12.7mm.

GB/T 3142 was used to test the last nonseizure load (PB) and weld point (PD) of oil containing extreme pressure agents, in order to compare the sensitivity of different base oils to extreme pressure agents.

The antiwear performance of lubricants containing different extreme pressure antiwear agents was tested using SH/T 0198 method. Considering the load-bearing capacity of the selected additive, the load for most experiments was 196N, with a temperature of 75℃, a testing time of 60 minutes, and a rotational speed of 1200rpm. After the experiment, the diameter of the wear marks was observed under an electron microscope. Under constant speed conditions, the lubrication state of the lubricant is relatively stable and single. In order to comprehensively investigate the lubrication performance of the base oil under different lubrication states, the speed of the four balls friction testing machine is controlled by code to increase from 0 to 2800rpm at a rate of 20rpm per 0.5 minutes. Other conditions are the same as those of the constant speed test. The diameter of the wear marks after the test is recorded as .So as to achieve performance testing of lubricants under different lubrication states. Due to the good antiwear performance of Amine Phosphates, it mainly acts as a friction modifier under a load of 198N. Therefore, larger test load conditions of 396N and 785N were added to investigate its antiwear performance in different base oils.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Structure and Property Relationship of Coal Based Base Oil

The results of physical and chemical properties of different base oils are shown in

Table 3. CTL4 has high viscosity index, flash point and low evaporation loss for hydroisomerization base oils of about 4.0cSt. The higher viscosity index indicates that the viscosity of CTL4 is less sensitive to temperature changes. The high flash point indicates that CTL4 has good safety. The low evaporation loss indicates that CTL4 is not easy to evaporate at high temperature. The pour point of CTL4 is significantly lower than that of mineral base oil, but 6℃ higher than that of GTL4. The low temperature dynamic viscosity (CCS) at 30℃ reflects the low temperature fluidity of oil products. CTL4 has obvious advantages over mineral base oil in low temperature fluidity, and is slightly better than GTL4.

For PAO base oil, the viscosity index, flash point, evaporation loss and -30℃ low temperature dynamic viscosity of mPAO4 were slightly better than those of commercial PAO4, but the pour point of mPAO4 was significantly lower than that of commercial PAO4. In general, coal based base oils show certain advantages over mineral based and natural gas based base oils in viscosity temperature performance, low temperature fluidity and evaporation loss.

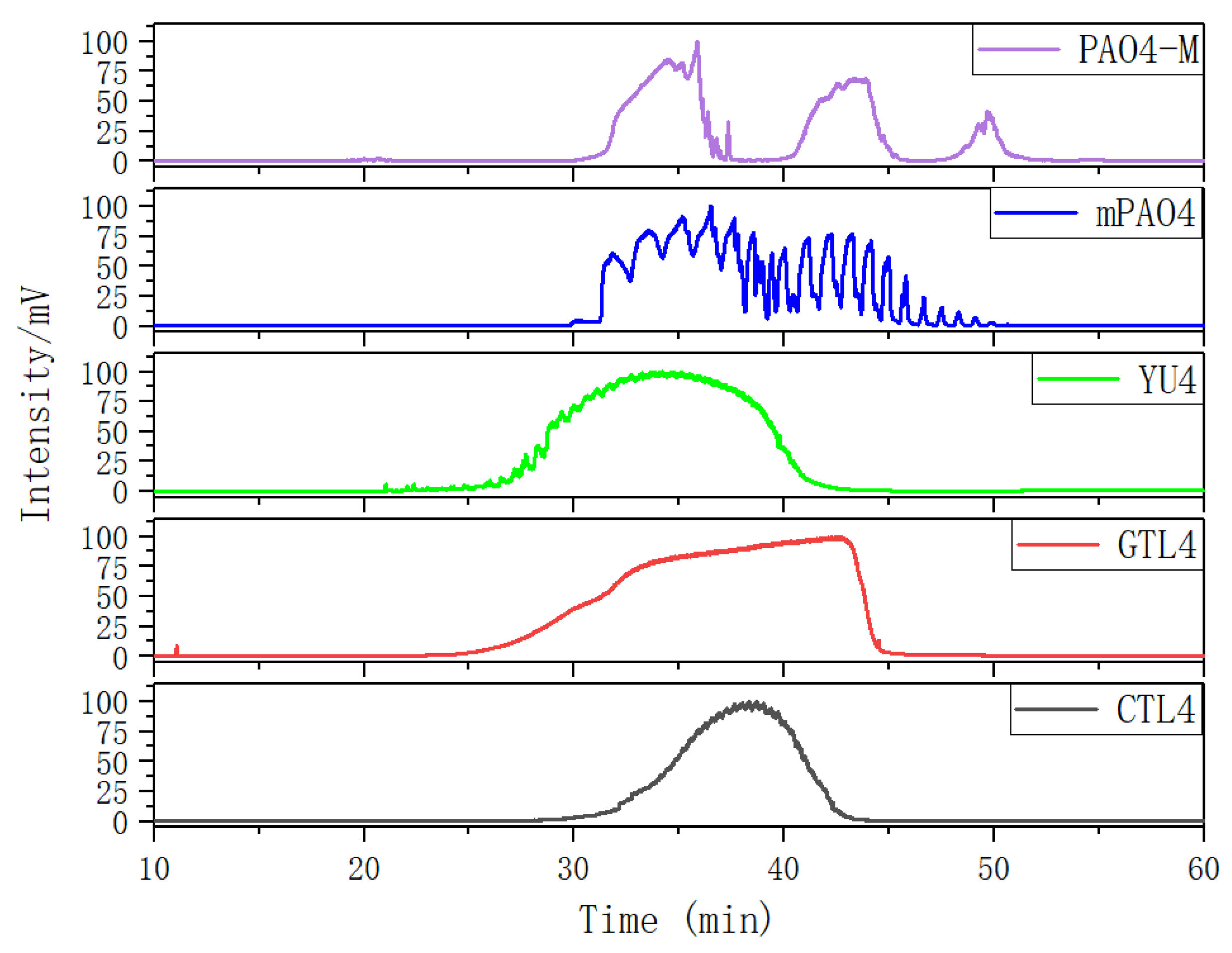

Figure 2 shows the gas chromatographic (GC) curves of different base oils after normalization. The GC curves of three kinds of 4.0cSt hydroisomerization base oils present a single peak form, which indicates that the boiling points of the components in the base oil are continuously distributed. The peak width of CTL4 is significantly smaller than that of GTL4 and YU4, indicating that the components of CTL4 are more concentrated. Compared with CTL4, the content of low boiling point components of YU4 and GTL4 is higher, which is the reason for their low flash point and high evaporation loss.

The GC curves of the two PAO base oils show a multi peak form. The GC of mPAO4 consists of two large peaks, which contain several small peaks. Two big peaks represent the trimer and tetramer of α-olefins. The small peaks that make up the trimer and tetramer peaks are molecules with different isomeric forms under the degree of polymerization. MPAO4 has less molecular isomerization forms of the same polymerization, which leads to obvious differences in boiling points between molecules. This results in the GC curve exhibiting multiple small peaks. However, PAO4 prepared with non metallocene catalyst has more isomerization forms, which makes the difference in boiling points of the same polymerization molecules not obvious. This results in the GC curve more smooth. The third small peak of the PAO4-M curve is pentamer. Since mPAO4 basically does not contain pentamer, its kinematic viscosity is slightly lower than that of PAO4-M, and its pour point and low-temperature fluidity are better.

The molecular weight test results of different base oils by GPC in

Table 4. The separation mode of GPC is not based on molecular weight, but on the volume of polymer in solution. Therefore, it is difficult to test the molecular weight of polymers with molecular weight less than 1000. However, the molecular weight obtained by GPC test can indirectly reflect the volume of base oil in solution. In

Table 4, due to the existence of pentamer, the number average Mn and weight average MW molecular weights of commercially available PAO4-M are significantly greater than those of mPAO4. And the molecular weight distribution of commercially available PAO4-M is wider, which is consistent with the information obtained by GC.

For hydroisomerization base oils, it can be found that the molecular weight distribution of CTL4 is narrower and the average molecular weight is relatively larger. This is due to fewer light components and a more concentrated distribution of components. YU4 has the lowest average molecular weight and wide molecular weight distribution due to its large amount of light components. GTL4 has more high boiling point components than CTL4 and YU4, but its low boiling point components are higher than CTL4. This leads to GTL4’s molecular weight is slightly less than CTL4 and its molecular weight distribution is wider than CTL4.

Table 5 summarizes the results of 1H NMR and 13C NMR spectra. The BI of hydroisomerization base oils is about 10.0% higher than that of PAO base oil. This indicates that the isomerization degree of hydroisomerization base oil is high. Combined with the VI of base oils it is found that the VI of base oils is negatively correlated with the branching degree BI, whether it is hydroisomerization base oils or PAO base oils. But YU4 is an exception. This may be related to its special branching form and location.

The content of nonbranched carbon in PAO is higher than that in hydroisomerization base oil. is the statistical value of methyl branching content in base oil molecules. It can be found that the of hydroisomerization base oils is significantly higher than that of PAO base oils. The above structural statistical results once again prove that the isomerization degree of hydroisomerization base oil was greater than that of Pao base oil. which is consistent with the BI value test results. The base oil with high isomerization degree of hydrocarbon base oil may have better solubility of additives.

In the hydroisomerization base oils, the content of nonbranched carbon of YU4 is significantly higher than that of CTL4 and GTL4. And the value of CTL4 is slightly higher than that of GTL4. However, it is strange that the of CTL4 base oil is also larger than that of GTL4. It is not significantly smaller than GTL4 as YU4. This indicates that CTL4 contains high methyl content and branched carbon content at the same time. When the total carbon content of all base oils is basically the same, it means that there are fewer other branched forms of CTL4. From the content of ethyl branched EB1 of different base oils, EB1 of CTL4 is slightly smaller than that of GTL4. At the same time, the BI of GTL4 is higher, but the is less than that of CTL4, indicating that there are branches that are not counted. For example, ethyl branching near the end of the chain. Further, the proportion of methylated branches in CTL4 base oil is also slightly higher than that in GTL4. In terms of the proportion of chain end branching of different base oils, the of CTL4 and YU4 at the end of the chain is significantly less than that of GTL4. represents the degree of other branching near the methyl branching of the chain. For isomerization hydroisomerization base oil, the value of YU4 is high. It shows that there are more other branches around the methyl chain, indicating that the branching aggregation degree is high. However, the value of GTL4 is 0, indicating that there is no effect of other structures near the methylation of its chain. Its chain branching density is low. The branch on the long branched chain can improve the low temperature fluidity of base oil.

Based on the structural analysis of different hydroisomerization base oils. Compared with GTL4, the overall branching degree of CTL4 is slightly lower, and the content of unbranched carbon in the molecule is higher. CTL4 branched form is less, mainly methyl branched, while other branched forms are less. In terms of branching position, CTL4 has less branching at the end of the chain, and the branching concentration is slightly higher than that of GTL4. The branching degree of YU4 is much less than that of GTL4 and CTL4, and there are a large number of unbranched carbon in the molecule. The main form of branching is dense methyl branching. According to the analysis results of rheological properties of different isomeric alkanes in reference [

25], the molecular pour point of isomeric alkanes with long unbranched length of main chain is generally poor. This is the reason why the pour points of different base oils are YU4>CTL4>GTL4 and YU4 with poor low temperature fluidity. Although the branchless carbon content of the two PAO base oils is also high, the molecular configuration of the PAO base oils is a long branched star structure, so they still have good low-temperature fluidity.

In PAO base oils, the methyl branched chain content of mPAO4 was slightly less than that of commercial PAO4-M, which was consistent with the phenomenon reflected by gas chromatography and branching degree BI. According to , the branched form of PAO base oil is mainly methyl branched, especially mPAO4 does not contain ethyl branched chain. By comparison, it was found that the percentage of terminal methyl branches of commercial PAO4-M was higher than that of mPAO4, indicating that the isomerization position was mainly at the end of the chain. Because the branching of Pao base oil mainly occurs at the end of the chain, the content of MB2 is low and the content of MB4 is high due to the influence of skeleton carbon, so the negative value of has no practical significance. Due to the use of new catalysts, mPO4 has the characteristics of low degree of isomerization and few isomerization forms. The structure of mPAO4 is more regular, so it has better performance.

3.2. Oxidation Stability of Base Oil

Table 6 shows the test results of oxidation stability of different base oils using PDSC and RBOT. As seen, when the base oil is not added, the oxidation stability of several base oils under different test conditions has little difference. Among them, the oxidation stability of petroleum based YU4 is relatively good, because it is difficult to remove a small amount of aromatic compounds in the preparation process. Aromatic compounds have certain antioxidant properties. Therefore, YU4 base oil has good oxidation stability.

3.3. Sensitivity Performance of Different Base Oils with Antioxidants

Table 7 shows the sensitivity comparison of different base oils to thioester type (AO1) antioxidant. It can be found that the IOT of the above base oils added with 0.5 wt % AO1 antioxidant has no significant change compared with the base oil under the PDSC temperature program test condition. However, under the constant temperature test condition of 160℃, the OIT of most base oils except CTL4 increased significantly, indicating that CTL4 has poor sensitivity to thioester antioxidant. For the base oil other than CTL4, the OIT increased by at least one time after adding 0.5wt% AO1 antioxidant. And the OIT of mPAO4 containing 0.5wt% AO1 is 110.94 min, which is much greater than that of PAO4-M, indicating that mPAO4 has good sensitivity to thioester antioxidant.

It is found that the RBOT duration of base oils increases to varying degrees, indicating that the antioxidant played a role under the test conditions. Among them, the RBOT duration of CTL4 increases slightly, indicating that its sensitivity to AO1 is weak. The RBOT duration of the two PAOs is significantly longer than that of CTL4, both of which is about 360min, indicating that the sensitivity of the two PAOs to AO1 antioxidant is similar. Compared with the base oil, the RBOT duration of GTL4 and YU4 reaches about 500min and 1500min respectively, indicating that GTL4 and YU4 have better sensitivity to AO1, and YU4 has the most prominent sensitivity. The above test results show that for the same antioxidant, different base oils and service conditions have significant effects on its performance.

Table 8 shows the sensitivity comparison of different base oils to phenolic (AO2) antioxidants. It can be found that the initial oxidation temperature IOT of the above base oils added with 0.5wt% AO2 antioxidant is significantly higher than that of the base oils under the PDSC temperature program test. Under the condition of constant temperature test at 160℃, the OIT of all base oils increases significantly. But the increase of oxidation induction period of two PAO base oils is more obvious, which indicates that PAO base oils is more sensitive to phenolic antioxidants. Among the hydroisomerization base oils, YU4 has the best sensitivity to AO2, followed by CTL4 and GTL4.

Under the optimized RBOT test conditions, the RBOT duration of several base oils containing 0.5wt% phenolic antioxidant is significantly increased. The duration of RBOT of YU4, mPAO4 and PAO4-M is up to 4000~6000min, while the duration of rotating oxygen bomb of CTL4 and GTL4 is less than 1000min, about 300min and 700min. The above phenomenon shows that CTL4 and GTL4 have poor sensitivity to phenolic antioxidants.

Table 9 shows the sensitivity comparison of different base oils with amine type (AO3) antioxidant. It can be found that the IOT of the above base oils added with 0.5wt% AO3 antioxidant is significantly higher than that of the base oils under the PDSC temperature program test. As a high-temperature antioxidant, the OIT of all base oils is significantly higher than that of base oils under the constant temperature test condition of 160℃, and is significantly higher than that of base oils containing 0.5wt% phenolic antioxidant. The OIT of two kinds of PAO4 and YU4 increased more obviously, which could reach more than 110min, indicating that the sensitivity of PAO and YU4 base oils to amine antioxidants is more prominent. In the hydroisomerization base oil, the oxidation induction period of CTL4 and GTL4 is only about 80min, which indicates that the sensitivity of F-T base oil to amine antioxidant is different from that of petroleum based YU4.

Under the optimized RBOT test conditions, the RBOT duration of several base oils containing 0.5wt% amine antioxidant is significantly improved compared with the base oils. The time of mPAO4 and PAO4-m ROBT is about 4000min and 5000min respectively. The performance of AO3 in mPAO4 is equivalent to that of 0.5wt% AO2. The performance of high temperature antioxidant AO3 in the same dose of PAO4-M is better than that of AO2. In hydroisomerization base oil, the RBOT time of AO3 as high temperature antioxidant is significantly shorter than that of AO2. Through the comparative analysis of PDSC constant temperature test conditions and optimized RBOT test conditions. The results show that the main difference between the two is that the optimized RBOT test is a fully closed system catalyzed by iron metal. The water generated by its oxidation cannot be discharged from the oxidation system. The presence of water will accelerate the formation of free radicals. However, phenolic antioxidants have a terminating effect on free radicals. Therefore, the RBOT time of base oil containing phenolic antioxidant is longer than that of amine antioxidant. At the same time, the number of branch chains of YU4, mPAO4 and PAO4-M base oils is less than that of CTL4 and GTL4, which means that they have less tertiary hydrogen and have a lower rate of generating free radicals in the oxidation process. Therefore, YU4, mPAO4 and PAO4-M have better sensitivity to amine type and phenol type antioxidants. In particular, the two kinds of PAO4 have better sensitivity to phenolic and amine antioxidants due to their lower .

3.4. Lubricating Performance of Different Base Oils

Table 10 shows the lubrication performance test results of different base oils.

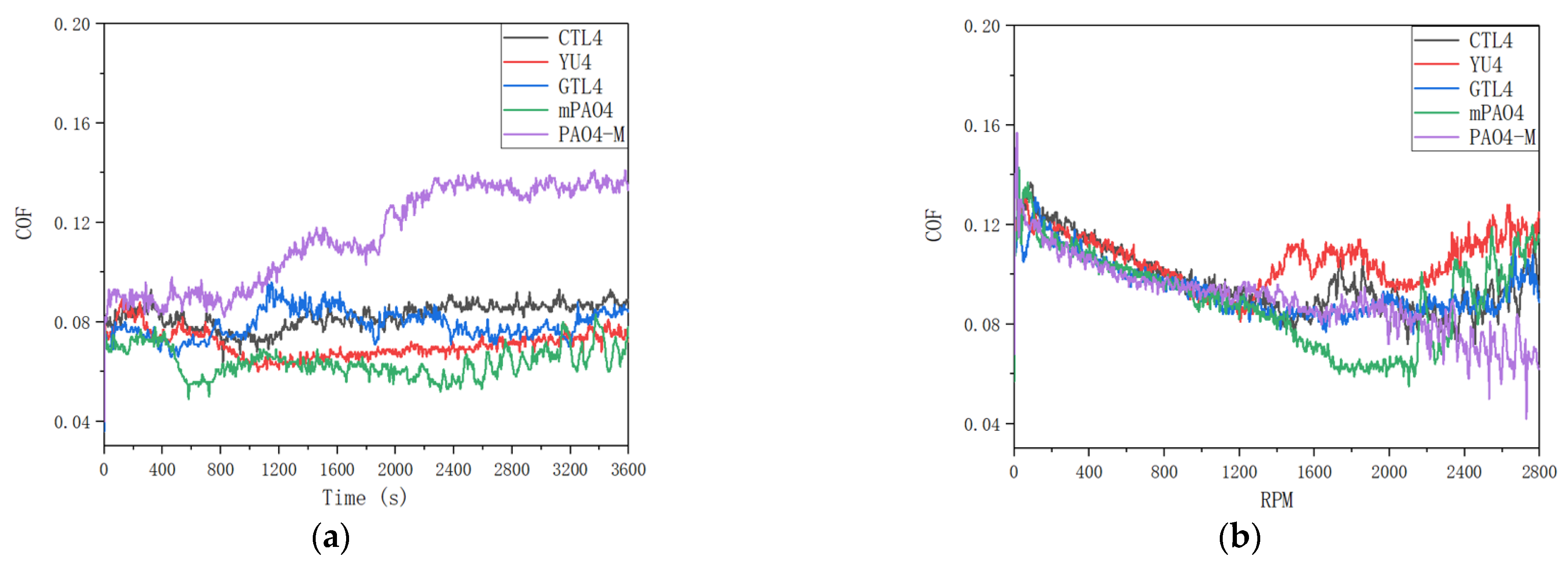

Figure 3 shows the friction coefficient curve under constant speed and variable speed test conditions. It can be seen from the data in the table that under the test conditions of 1200rpm constant speed and 0-2800rpm variable speed, the lubrication performance of different base oils with about 4.0cSt is obviously different. Among them, the wear scar diameter and friction coefficient of commercially available PAO4-M are large, indicating that its lubrication performance is poor. The friction coefficient of PAO4-M has been rising during the friction test, while other base oils are relatively stable. Under the condition of constant speed test, the wear scar diameters (WSD) of coal based CTL4 and mPAO4 are the same, but the friction coefficient of mPAO4 is the smallest among all base oils due to its increased molecular weight and regular structure. The WSD of YU4 and GTL4 are close to each other, both of which are about 0.55mm, and have better performance in all base oils.

According to the principle of stribeck curve, in the process of variable speed test, the lubricant is in boundary lubrication state at low speed. With the increase of speed, the lubricant film thickness increases, and the lubrication state changes from boundary lubrication to elastic fluid lubrication. With the further increase of speed, due to the enhanced shear effect of contact surface, the heat generated by friction, leading to the transformation of lubricant from Newtonian fluid to non Newtonian fluid, thus reducing the bearing capacity of lubricant. Therefore, during the variable speed test of different base oils, the friction coefficient curve generally shows a trend of first decreasing and then increasing.

By comparing the friction coefficient curves of different base oils (Figure3) under variable speed test conditions, it can be found that the variation trend of friction coefficient is basically the same before 1200rpm, and both are linear decline. After 1200rpm, due to less ethyl branching of YU4 and relatively small molecular volume (it can also be seen from GPC data), the thickness of oil film formed by YU4 is insufficient. The friction coefficient curve of YU4 rises first, indicating that its shear resistance is the worst, which also leads to the increase of wear in the variable speed test. When compared with YU4, the friction coefficient of mPAO4 base oil continues to decrease with the increase of rotating speed after 1200rpm. The rising friction coefficient appears after maintaining the elastic fluid lubrication state for a period of time, so the wear scar diameter of mPAO4 is the smallest after the test. The molecular structures of GTL4 and CTL4 are similar, so the change process of friction coefficient in variable speed test is similar, and the results after test are basically the same. For PAO4-M, due to its large molecular volume, it entered the elastohydrodynamic lubrication stage with relatively stable friction coefficient after 1200rpm. Then with the increase of rotating speed, the friction coefficient does not rise, but decreases. This may be due to the high molecular volum of PAO4-M. With the increase of rotating speed in the process of high-speed friction, the surface wear is more likely to form an elastic fluid lubrication film after metal polishing, which makes the friction coefficient fluctuate and decrease. Similarly, the friction coefficient of CTL4 and mPAO4 fluctuats at high speed.

3.5. Sensitivity Performance of Base Oil with Extreme Pressure Antiwear Additives

Table 11 shows the sensitivity test results of different base oils to 1.0wt% EP additive. The addition of 1.0wt% EP plays a certain antiwear protection role compared with the base oil without additives. In the constant speed test, the wear scar diameter of GTL4 is small, which indicates that it has good antiwear sensitivity to EP. The sensitivity of mPAO4 to EP is relatively poor in constant speed and variable speed tests. However, the WSD of other base oils, whether constant speed test or variable speed test, are relatively close after the test, indicating that the performance of EP in different base oils is basically the same. In the extreme pressure performance test of different base oils containing 1.0wt% EP, the extreme pressure additives mainly play a role in the sintering of steel balls, so the base oil has little effect on the sintering load, so there is no difference in the weld point PD of different base oils. However, in the last nonseizure load PB test, different base oils showed slight differences. The PB of GTL4 and mPAO4, which performed well in the antiwear performance test, was one load level lower than that of other base oils. In general, the sensitivity of different base oils to EP additives is different, but the difference is not significant.

Table 11 shows the sensitivity test results of different base oils to 1.0wt% antiwear additive AW1.

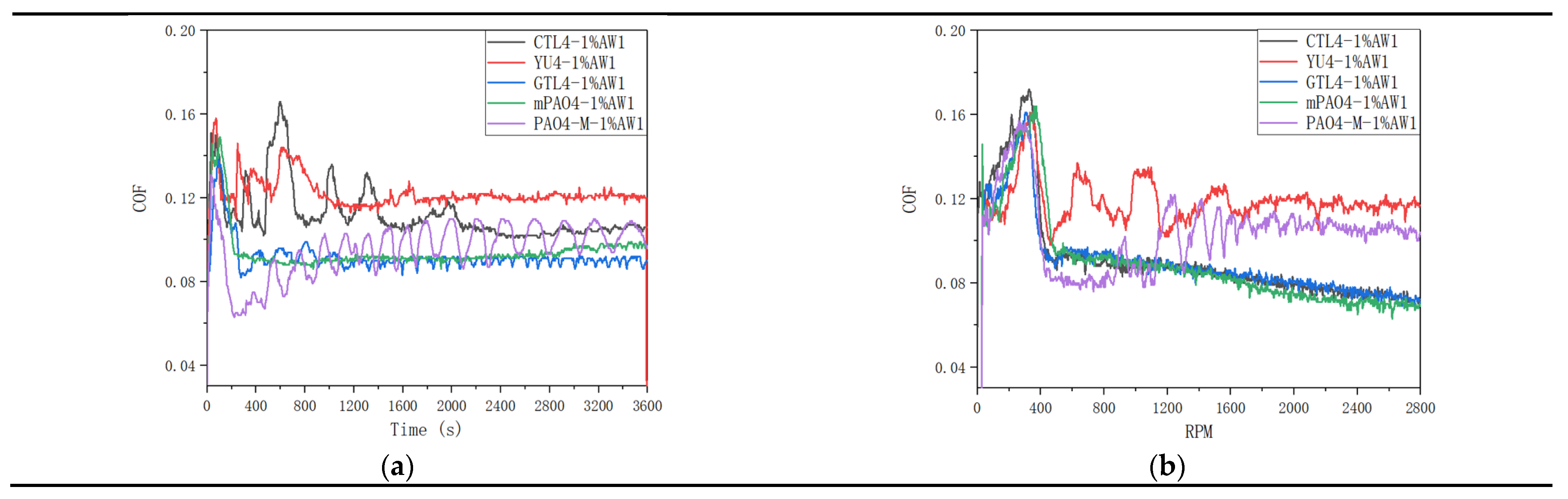

Figure 4 shows the friction coefficient curve of lubricant under constant speed and variable speed test conditions. The addition of antiwear agent AW1 plays a significant antiwear role. In the constant speed experiment, the WSD of mPAO4 and GTL4 were significantly smaller than those of other base oils, and their friction coefficient curves were relatively stable in the experiment. On the contrary, PAO4-M containing 1.0wt% AW1 has a larger WSD after the test, and due to the poor lubrication performance of PAO4-M base oil itself, periodic “wear polishing” process may occur during the constant speed test, resulting in periodic fluctuations in the friction coefficient curve. For CTL4 and YU4, their sensitivity to AW1 antiwear agent is between that of other base oils. It can be seen from

Figure 4 that in the variable speed test, when the speed is less than 400rpm, the lubricant is in the running in state, and the friction coefficient shows an upward trend with the increase of speed, and the friction coefficient of different lubricants has little difference. When the running in is completed, the friction coefficient of the lubricant used decreases rapidly when the speed is greater than 400rpm, and then the friction coefficient curves of different lubricants show different trends. The friction coefficient curves of CTL4, GTL4 and mPAO4 base oils containing 1.0wt% AW1 antiwear agent decrease steadily with the speed, while the friction coefficient curves of YU4 and PAO4-M show a fluctuating upward trend. After the test, the ball wear scar diameter of CTL4, GTL4 and mPAO4 base oils containing 1.0wt% AW1 antiwear agent was significantly smaller than that of YU4 and PAO4-M, indicating that CTL4, GTL4 and mPAO4 base oils have better sensitivity to AW1.

Table 11.

Sensitivity test results of different base oils for antiwear additive AW1.

Table 11.

Sensitivity test results of different base oils for antiwear additive AW1.

| |

1.0wt%AW1 |

| |

CTL4 |

YU4 |

GTL4 |

mPAO4 |

PAO4-M |

/mm

(COF) |

0.420

(0.112) |

0.395

(0.122) |

0.350

(0.092) |

0.341

(0.094) |

0.480

(0.096) |

|

/mm |

0.307 |

0.418 |

0.292 |

0.308 |

0.465 |

Table 12 shows the sensitivity test results of different base oils to 1.0wt% antiwear agent AW2.

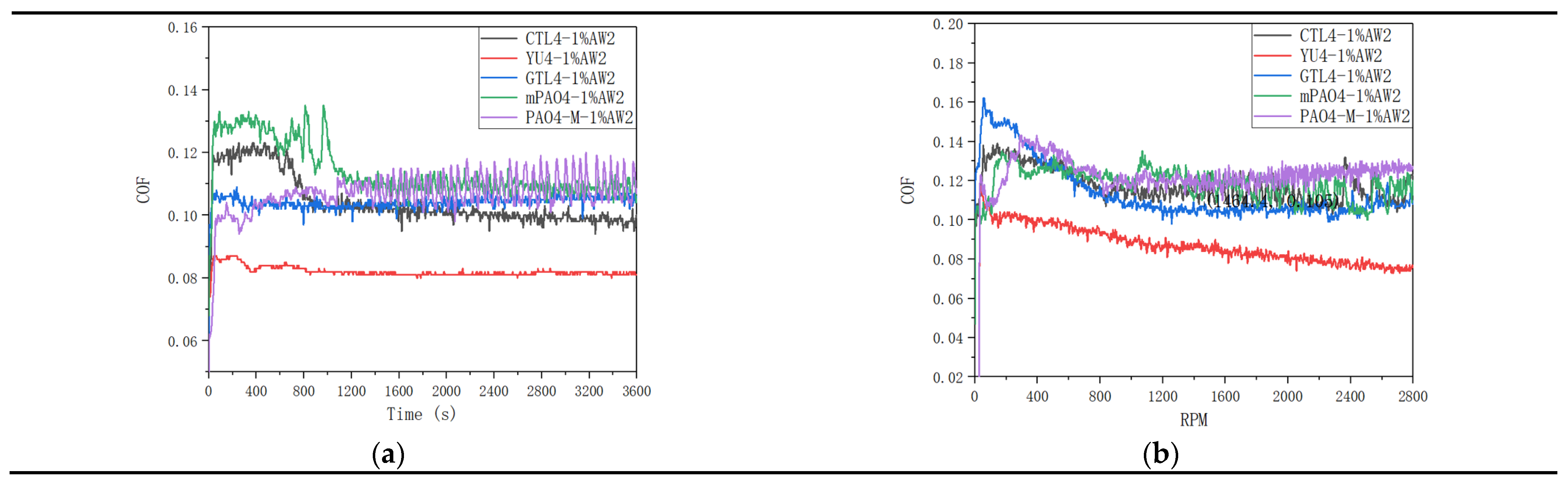

Figure 5 shows the friction coefficient curve of lubricant under constant speed and variable speed test conditions. The addition of antiwear additive AW2 plays a significant antiwear role. Under the condition of constant speed test, the sensitivity of different base oils to AW2 is positively correlated with the lubrication performance of the base oil itself. PAO4-M has the worst sensitivity to AW2. YU4 and GTL4 have the best sensitivity to AW2. CTL4 and mPAO4 have much better sensitivity to AW2 than PAO4-M, but not as good as YU4 and GTL4. In the variable speed test, the sensitivity of different base oils to AW2 is consistent with that in the constant speed test. The sensitivity of CTL4 and mPAO4 to AW2 is significantly better than PAO4-M, but less than YU4 and GTL4. It is worth noting that from the antiwear performance data shown in

Table 12 and the friction coefficient curve shown in

Figure 5. AW2 as a typical antiwear agent that has been used in petroleum base oil for decades, shows excellent antiwear and friction reducing effect in petroleum base oil YU4, while the antiwear and friction reducing effect in other synthetic base oils is far less than YU4. On the one hand, it reveals the necessity of developing synthetic lube base oil, and on the other hand, it also reminds us that the lubricating additives or compounding agents developed in petroleum base oil may not be able to perform as well in synthetic base oil as in petroleum based.

Table 13 shows the sensitivity test results of 1.0wt% antiwear additive AW3 on different base oils.

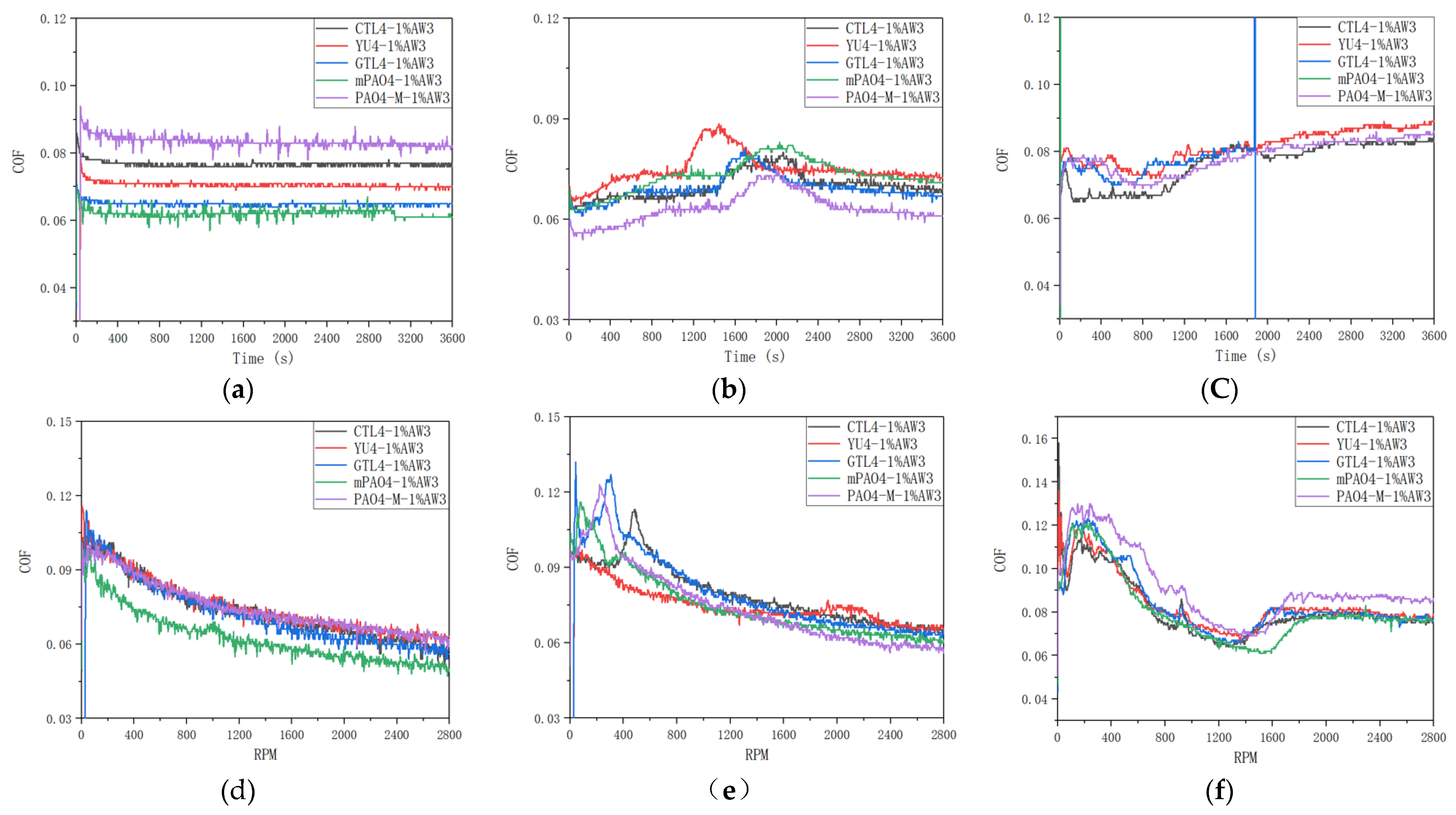

Figure 6 shows the friction coefficient curves of a lubricant containing 1.0wt% AW3 under different load constant speed and variable speed tests.

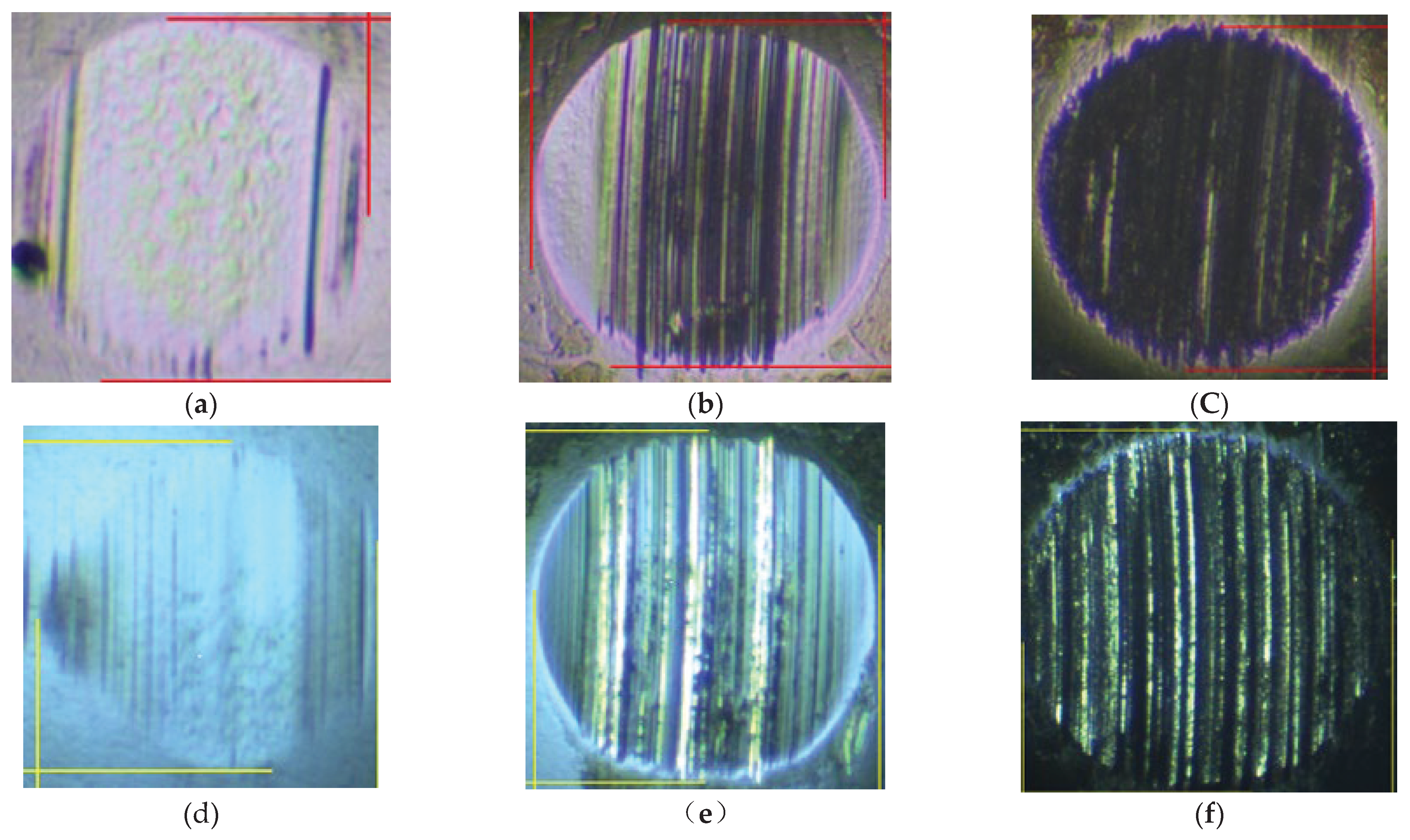

Figure 7 shows the typical morphology of steel ball wear marks after constant and variable speed tests under different loads. According to

Table 13, under constant and variable speed test conditions, the lubrication performance of different base oils is basically the same when the load is 198N and 396N. Based on the friction coefficient curve in

Figure 6 and the analysis of the wear scar morphology of steel balls under different loads in

Figure 7. It can be concluded that AW3 mainly plays a role as a friction modifier under light loads. This reduces the actual contact area of the friction pair, resulting in a more similar morphology of the wear marks on different base oils. It is worth noting that in the constant and variable speed tests of 198N, the friction coefficient of mPAO4 base oil was significantly lower than that of other base oils. This is mainly due to the good lubrication performance of mPAO4 base oil itself, combined with the surface physical adsorption of AW3, which enhances its film-forming ability. The exception is that the wear scar diameter of YU4 is significantly larger after the 396N variable speed test, which is mainly due to the poor shear resistance of YU4 base oil itself.

In the variable speed test, the bearing capacity of the base oil is weaker when the speed is higher. There is a significant difference in the sensitivity of different base oils to 1.0wt% AW3 under the constant speed test conditions of 792N high load. After repeated experimental verification, mPAO4 and GTL4 base oils shows seizure phenomenon during the start-up and midway stages of the test, indicating poor sensitivity to AW3, while other base oils have similar sensitivity to AW3 antiwear agents. In the 792N high load variable speed test, the friction coefficient of different base oils containing 1.0wt% AW3 antiwear agent experienced a trend of first decreasing, then increasing, and then stabilizing with increasing speed. The decrease in friction coefficient in the early stage is mainly caused by the increase in speed and the increase in lubricating oil film thickness, which is related to the characteristics of the base oil itself. For example, if the film forming ability of PAO4-M is poor, its friction coefficient is greater than other base oils during the speed increase process. As the rotational speed increases, the shear effect of the friction pair on the lubricant increases, and the oil film thickness decreases, resulting in an increase in the friction coefficient. However, as the antiwear agent undergoes frictional chemical reactions with the metal surface, antiwear substances are generated on the surface of the friction pair, gradually stabilizing the friction coefficient. Among all base oils containing 1.0wt% AW3 antiwear agent, mPAO4 base oil reaches the highest speed of friction coefficient increase and has the lowest friction coefficient, which once again proves that mPAO4 has good oil film forming ability and shear resistance.

4. Conclusions

In this study, the structure property relationships of a variety of 4.0cSt base oils including coal to hydroisomerization base oil (CTL4) and coal to poly alpha olefin base oil (mPAO4) and the sensitivity of typical antioxidants, extreme pressure agents and antiwear agents were studied. The main conclusions are listed as follows:

(1) Compared to other hydroisomerization base oils, the composition distribution of CTL4 is more concentrated. Compared with GTL4, the overall branching degree of CTL4 is slightly lower, and the content of unbranched carbon in the molecule is higher. CTL4 branched form is less, mainly methyl branched. CTL4 has less branching at the end of the chain, and the branching concentration is slightly higher than that of GTL4.

(2) Compared to commercially available PAO4-M base oil, mPAO4 base oil has less degree and type of isomerization, and there is no ethyl branched chain isomerism in the isomeric form, resulting in a more regular molecular structure.

(3) Compared to GTL4 and YU4 base oils, CTL4 base oil has better viscosity temperature performance, low temperature fluidity, fire safety and evaporation loss. The lubricating properties of the three hydroisomerization base oil are similar. The physicochemical properties and lubricating properties of mPAO4 base oil are better than those of commercial PAO4-M base oil.

(4) There is no significant difference in the oxidation stability of different base oils. The sensitivity of different base oils to phenolic and amine antioxidants is better than that of sulfur antioxidants. The sensitivity of petroleum base oil and PAO base oil to typical antioxidants is better than that of coal or natural gas based hydroisomerization base oil.

(5) The sensitivity of different base oils to typical extreme pressure agents is slightly different, but the sensitivity to typical antiwear agents is different. CTL4, GTL4 and mPAO4 base oils have better sensitivity to AW1 antiwear agent. The sensitivity of CTL4 and mPAO4 to AW2 antiwear additive was significantly better than PAO4-M. mPAO4 has a better sensitivity to reducing the friction coefficient of AW3.

(6) The sensitivity of typical antioxidants and antiwear agents in F-T synthetic base oil is generally lower than that of mineral base oil and PAO base oil. It is necessary to develop new additives for F-T synthetic base oil.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J. L. and Z. Z.; methodology, J. L. and M. P.; software, Z. Z.; validation, X. Z., and W. H.; formal analysis, X. Z.; investigation, J. L. and M. P.; resources, Z. Z.; data curation, X. Z.; writing—original draft preparation, Z. Z.; writing—review and editing, J. L.; visualization, J. L.; supervision, W. H.; project administration, X. Z. and M. P.; funding acquisition, J. L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the 2021 Chinese Academy of Sciences Science and Technology Service Network Program (STS)-Dongguan Special Technology Innovation Project (20211600200042), and Henan Province Science and Technology Research and Development Joint Fund (235101610007).

Acknowledgments

Thank to Shanxi Lu'an Taihang Lubrication Technology Co., Ltd. for providing base oils and some tests.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Bart, J. C. J.; Gucciardi, E.; Cavallaro, S. , 3 - Lubricants: properties and characteristics. In Biolubricants, Bart, J. C. J.; Gucciardi, E.; Cavallaro, S., Eds. Woodhead Publishing: 2013; pp 24-73. [CrossRef]

- Sun, F. , Technical progress of lubricant base oil production in China, Energy Chemical Industry 2018, 39 ( 03), 41–45. [Google Scholar]

- Clark, R. H.; Wedlock, D. J.; Cherrillo, R. A. , Future fuels and lubricant base oils from shell gas to liquids (GTL) technology. SAE transactions 2005, 1095–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Tang, Q.; Xu, H.; Tang, M.; Li, X.; Liu, L.; Dong, J. , Alkyl-tetralin base oils synthesized from coal-based chemicals and evaluation of their lubricating properties. Chinese Journal of Chemical Engineering 2023, 58, 20–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatto, V.; Grina, M. , Effects of base oil type, oxidation test conditions and phenolic antioxidant structure on the detection and magnitude of hindered phenol/diphenylamine synergism. Tribology & Lubrication Technology 1999, 55 (1), 11.https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/effects-base-oil-type-oxidation-test-conditions/docview/226953099/se-2.

- Giri, A.; Coutriade, M.; Racaud, A.; Stefanuto, P. H.; Okuda, K.; Dane, J.; Cody, R. B.; Focant, J. F. , Compositional elucidation of heavy petroleum base oil by GC × GC-EI/PI/CI/FI-TOFMS. Journal of mass spectrometry : JMS 2019, 54 2, 148-157. [CrossRef]

- Kramer, D. C.; Ziemer, J.; Cheng, M.; Fry, C. E.; Reynolds, R. N.; Lok, B. K.; Sztenderowicz, M. L.; Krug, R. R. , Influence of Group II & III base oil : Composition on VI and oxidation stability. NLGI spokesman 2000, 63, 20-39. https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:14716479.

- Korcek, S.; Jensen, R. K. , Relation between Base Oil Composition and Oxidation Stability at Increased Temperatures. A S L E Transactions 1976, 19(2), 83–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yalin, Z.; Zhanquan, Z.; Yan, W.; Zhihua, Z. , Comparative analysis of products from Fischer-Tropsch oil and petroleum based oil. Chemical Industry and Engineering Progress 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hui, X.; Guoxu, C. , Study on the oxidative stability of coal-to-liquid base oil using pressure differential scanning calorimetry method. LUBRICATION ENGINEERING-HUANGPU-2008, 33 (4), 89-94. [CrossRef]

- Liangcheng, A.; Xiaowen, Y.; Yan, L.; E, C.; Xuemei, L.; Chun-hua, Z.; Yi-nan, Y. , Study on Sensitivity of GTL Base Oil and Antioxidant Additives. Contemporary Chemical Industry 2023, 52(3), 579–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xuemei, L.; Yiwen, P.; Yinan, Y.; Chaolin, P.; Shudan, Z.; Yangyang, L.; Yan, L. , Research on sensitivity of extreme-pressure and anti-wear additives in GTL base oil. LUBRICATION ENGINEERING-HUANGPU-2022, 47 (12), 132-137. [CrossRef]

- Huajie, T.; Jianlin, S.; Zhao, H.; Daoxin, S.; Zhangliang, Z. , Surface Lubrication and Adsorption Mechanism with Coal-to-Liquid as Aluminum Cold Rolling Base Oil. Acta Petrolei Sinica (Petroleum Processing Section) 2023, 39 (3), 650. [CrossRef]

- Yucheng, T.; Wei, H.; Zonggang, D.; Xian, F.; Lihua, Z. , Driving Test of Coal-Based SN 5W-30 Gasoline Engine Oil. Lubrication Engineering 48(7), 207-212. [CrossRef]

- Shoujing, G.; Tianzhong, B.; Xuemei, L.; Liangcheng, A.; Angui, Z. , Research on blending of different base oils and application in diesel engine oil. Petroleum Refinery Engineering 2021, 51 (9), 53.

- Zhang, C.; Wang, H.; Yu, X.; Peng, C.; Zhang, A.; Liang, X.; Yan, Y. , Correlation between the Molecular Structure and Viscosity Index of CTL Base Oils Based on Ridge Regression. ACS Omega 2022, 7(22), 18887–18896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, X.; Zhang, C.; Wang, H.; Wang, W.; Jiang, C.; Peng, C.; Yang, K. , Oxidation degradation analysis of antioxidant added to CTL base oils: experiments and simulations. Journal of Thermal Analysis and Calorimetry 2023, 148(14), 7033–7046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xueqian, W.; Huixin, W. , A Study into Using Olefin Made from Coal to Synthesize Low-viscosity Poly-alpha-olefin Base Oil. Sino-Global Energy 2013, 3, 71-74. [CrossRef]

- Huo, S.; Zhang, D.; Li, J.; Qian, J.; Yu, T. , Study on the Technology of Preparing Polyalphaolefin Synthetic Oil from Coal⁃ based Mixed Olefins. Journal of Liaoning University of Petroleum & Chemical Technology 2022, 42 (1), 24. [CrossRef]

- Jian, X.; Jiusheng, L.; Junyi's, L. Synthesis method of a metallocene catalyst. CN106543304A, 2017-03-29, 2017.

- Ma, Y.; Xu, J.; Jiang, H.; Li, J. , Low viscosity PAO preparation by oligomerization of alpha-olefin from coal with metallocene catalyst. Pet. Process. Petrochem. 2016, 47, 32–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Xu, J.; Zeng, X.; Jiang, H.; Li, J. , Preparation and performance evaluation of mPAO8 using olefin from coal as raw material. Industrial Lubrication and Tribology 2017, 69(5), 678–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarpal, A. S.; Kapur, G. S.; Mukherjee, S.; Jain, S. K. , Characterization by 13C nmr spectroscopy of base oils produced by different processes. Fuel 1997, 76(10), 931–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mäkelä, V.; Karhunen, P.; Siren, S.; Heikkinen, S.; Kilpeläinen, I. , Automating the NMR analysis of base oils: Finding napthene signals. Fuel 2013, 111, 543–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denis, J. , The relationships between structure and rheological properties of hydrocarbons and oxygenated compounds used as base stocks. Journal of Synthetic Lubrication 1984, 1(3), 201–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Technical route of coal to lubricant base oil.

Figure 1.

Technical route of coal to lubricant base oil.

Figure 2.

Gas chromatogram of different base oils.

Figure 2.

Gas chromatogram of different base oils.

Figure 3.

Friction coefficient curve of tests with different base oils: (a) 1200rpm constant speed ; (b) 0-2800rpm variable speed.

Figure 3.

Friction coefficient curve of tests with different base oils: (a) 1200rpm constant speed ; (b) 0-2800rpm variable speed.

Figure 4.

Friction coefficient curve of different base oils containing 1.0wt% AW1:(a)1200rpm constant speed ; (b) 0-2800rpm variable speed.

Figure 4.

Friction coefficient curve of different base oils containing 1.0wt% AW1:(a)1200rpm constant speed ; (b) 0-2800rpm variable speed.

Figure 5.

Friction coefficient curve of different base oils containing 1.0wt% AW2:(a)1200rpm constant speed ; (b) 0-2800rpm variable speed .

Figure 5.

Friction coefficient curve of different base oils containing 1.0wt% AW2:(a)1200rpm constant speed ; (b) 0-2800rpm variable speed .

Figure 6.

Friction coefficient curves of different base oils at different loads of 1.0wt% AW3:(a)198N, 1200rpm; (b) 396N, 1200rpm; (c) 792N, 1200rpm; (d) 198N, 0-2800rpm; € 396N, 0-2800N; (f) 792N, 0-2800rpm.

Figure 6.

Friction coefficient curves of different base oils at different loads of 1.0wt% AW3:(a)198N, 1200rpm; (b) 396N, 1200rpm; (c) 792N, 1200rpm; (d) 198N, 0-2800rpm; € 396N, 0-2800N; (f) 792N, 0-2800rpm.

Figure 7.

Typical morphology of steel ball wear marks after constant and variable speed tests under different loads: (a)198N, 1200rpm; (b) 396N, 1200rpm; (c) 792N, 1200rpm; (d) 198N, 0-2800rpm; (e) 396N, 0-2800N; (f) 792N, 0-2800rpm.

Figure 7.

Typical morphology of steel ball wear marks after constant and variable speed tests under different loads: (a)198N, 1200rpm; (b) 396N, 1200rpm; (c) 792N, 1200rpm; (d) 198N, 0-2800rpm; (e) 396N, 0-2800N; (f) 792N, 0-2800rpm.

Table 1.

Additives for test.

Table 1.

Additives for test.

| Code |

Name or structure |

| AO1 |

Thioester, Vanlube 7723 |

| AO2 |

Phenolic, Irganox L135 |

| AO3 |

Arylamine, Irganox L57 |

| EP |

Sulfurized isobutylene (sulphur content 40%-45%) |

| AW1 |

Tricresyl Phosphate, TCP |

| AW2 |

Zinc dialkyldithiophosphate, ZDDP |

| AW3 |

Amine Phosphates, Vanlube 672 |

Table 2.

Carbon atom position in base oil molecule corresponding to 13C chemical shift.

Table 3.

Test results of different base oil physicochemical properties.

Table 3.

Test results of different base oil physicochemical properties.

| |

CTL4 |

YU4 |

GTL4 |

mPAO4 |

PAO4-M |

Kinematic viscosity /mm2﹒s-1

40℃

100℃ |

17.33

3.97 |

18.99

4.12 |

18.44

4.063 |

16.73

3.85 |

18.73

4.12 |

| VI |

128 |

119 |

121 |

125 |

122 |

| Flash point /℃ |

233 |

225 |

224 |

212 |

202 |

| Pour point /℃ |

-33 |

-21 |

-39 |

-75 |

-66 |

| CCS(-30℃) /mPa﹒s |

1018 |

1421 |

1177 |

902 |

921 |

| NOACK evaporation loss (250℃,1h)/% |

11.8 |

15 |

12.4 |

12.1 |

12.9 |

Table 4.

GPC test results of base oils.

Table 4.

GPC test results of base oils.

| |

CTL4 |

YU4 |

GTL4 |

mPAO4 |

PAO4-M |

| Mn |

872 |

721 |

838 |

885 |

975 |

| Mw |

923 |

788 |

891 |

958 |

1075 |

| Mw/Mn |

1.058 |

1.092 |

1.064 |

1.083 |

1.103 |

Table 5.

NMR results of different base oils.

Table 5.

NMR results of different base oils.

| |

CTL4 |

YU4 |

GTL4 |

mPAO4 |

PAO4-M |

| ALL |

14.7 |

14.16 |

14.72 |

14.87 |

14.71 |

| TMU |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

| S1 |

0.67 |

0.67 |

0.79 |

1.72 |

1.72 |

| S3 |

0.34 |

0.41 |

0.38 |

1.41 |

1.2 |

| BL |

1.74 |

2.09 |

1.5 |

1.69 |

2.17 |

| ME1-2 |

0.13 |

0.1 |

0.13 |

0.02 |

0.13 |

| ME2-1 |

0.14 |

0.11 |

0.15 |

0 |

0.01 |

| ME3-1 |

0.14 |

0.1 |

0.13 |

0.02 |

0.07 |

| MB2 |

0.42 |

0.36 |

0.31 |

0.03 |

0.03 |

| MB4 |

0.8 |

0.57 |

0.62 |

0.28 |

0.08 |

| EB1 |

0.21 |

0.1 |

0.22 |

0 |

0.01 |

| MB ALL |

1.06 |

0.77 |

0.99 |

0.09 |

0.04 |

| BI/% |

24.66 |

25.61 |

27.23 |

17.30 |

20.48 |

|

2.08 |

2.5 |

1.88 |

3.1 |

3.37 |

|

1.33 |

0.98 |

1.27 |

0.11 |

0.18 |

|

1.54 |

1.08 |

1.49 |

0.11 |

0.19 |

|

86.36% |

90.74% |

85.23% |

100.00% |

94.74% |

|

49.40% |

46.27% |

56.94% |

57.14% |

87.50% |

|

4.76% |

20.83% |

0.00% |

-366.67% |

-33.33% |

Table 6.

Oxidation stability of different base oils.

Table 6.

Oxidation stability of different base oils.

| |

CTL4 |

YU4 |

GTL4 |

mPAO4 |

PAO4-M |

| IOT/℃ |

198.53 |

201.5 |

198.08 |

199.58 |

201.78 |

| OIT(160℃)/min |

9.04 |

9.86 |

8.83 |

9.14 |

8.92 |

| RBOT/min |

29.2 |

39.8 |

35.9 |

29.2 |

32.0 |

Table 7.

Sensitivity of different base oils with thioester type (AO1) antioxidant.

Table 7.

Sensitivity of different base oils with thioester type (AO1) antioxidant.

| |

0.5 wt % AO1 |

| |

CTL4 |

YU4 |

GTL4 |

mPAO4 |

PAO4-M |

| IOT /℃ |

201.1 |

198.5 |

205.8 |

196.3 |

196.6 |

| OIT(160℃)/min |

11.2 |

29.0 |

25.1 |

110.9 |

28.4 |

| RBOT/min |

107.3 |

1524.6 |

499.8 |

342.5 |

373.7 |

Table 8.

Sensitivity of different base oilswith phenolic (AO2) antioxidants.

Table 8.

Sensitivity of different base oilswith phenolic (AO2) antioxidants.

| |

0.5wt% AO2 |

| |

CTL4 |

YU4 |

GTL4 |

mPAO4 |

PAO4-M |

| IOT/℃ |

208.3 |

214.7 |

211.8 |

211.5 |

211.0 |

| OIT(160℃)/min |

53.9 |

65.8 |

44.5 |

95.9 |

92.2 |

| RBOT/min |

323.2 |

5979.1 |

701.0 |

4193.2 |

4262.9 |

Table 9.

Sensitivity of different base oils to amine type (AO3) antioxidant.

Table 9.

Sensitivity of different base oils to amine type (AO3) antioxidant.

| |

0.5wt% AO3 |

| |

CTL4 |

YU4 |

GTL4 |

mPAO4 |

PAO4-M |

| IOT/℃ |

216.5 |

214.1 |

215.1 |

216.0 |

218.8 |

| OIT(160℃)/min |

76.97 |

114.7 |

85.0 |

130.6 |

123.8 |

| RBOT/min |

242. 5 |

512.1 |

476.0 |

3912.0 |

5022.7 |

Table 10.

Lubricating performance test results of different base oils.

Table 10.

Lubricating performance test results of different base oils.

| |

CTL4 |

YU4 |

GTL4 |

mPAO4 |

PAO4-M |

/mm

(COF) |

0.627

(0.082) |

0.541

(0.071) |

0.555

(0.072) |

0.625

(0.064) |

0.806

(0.114) |

|

/mm |

0.761 |

0.777 |

0.762 |

0.704 |

0.785 |

Table 11.

Sensitivity test results of different base oils with EP.

Table 11.

Sensitivity test results of different base oils with EP.

| |

1.0wt%EP |

| |

CTL4 |

YU4 |

GTL4 |

mPAO4 |

PAO4-M |

/mm

(COF) |

0.424

(0.112) |

0.442

(0.094) |

0.398

(0.110) |

0.459

(0.103) |

0.430

(0.086) |

|

/mm |

0.502 |

0.517 |

0.512 |

0.551 |

0.512 |

| PB/kg |

52 |

52 |

48 |

52 |

48 |

| PD/kg |

315 |

315 |

315 |

315 |

315 |

Table 12.

Sensitivity test results of different base oils for antiwear additive AW2.

Table 12.

Sensitivity test results of different base oils for antiwear additive AW2.

| |

1.0wt%AW2 |

| |

CTL4 |

YU4 |

GTL4 |

mPAO4 |

PAO4-M |

/mm

(COF) |

0.418

(0.104) |

0.270

(0.082) |

0.297

(0.104) |

0.419

(0.114) |

0.537

(0.116) |

|

/mm |

0.516 |

0.312 |

0.379 |

0.549 |

0.606 |

Table 13.

Sensitivity test results of different base oils for antiwear additive AW3.

Table 13.

Sensitivity test results of different base oils for antiwear additive AW3.

| |

1.0wt%AW3 |

| |

CTL4 |

YU4 |

GTL4 |

mPAO4 |

PAO4-M |

/mm

(COF) |

0.262

(0.077) |

0.244

(0.070) |

0.250

(0.065) |

0.254

(0.062) |

0.255

(0.083) |

/mm

(COF) |

0.364

(0.070) |

0.368

(0.075) |

0.361

(0.069) |

0.363

(0.073) |

0.360

(0.063) |

/mm

(COF) |

0.484

(0.076) |

0.519

(0.081) |

0.865

(Seizure) |

>1.0

(Seizure) |

0.526

(0.079) |

|

/mm |

0.268 |

0.264 |

0.257 |

0.259 |

0.268 |

|

/mm |

0.391 |

0.526 |

0.398 |

0.360 |

0.383 |

|

/mm |

0.697 |

0.684 |

0.681 |

0.683 |

0.705 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).