Submitted:

19 March 2024

Posted:

21 March 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

| Authors | Location | Contribution | Limitations | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Z.Abdin et al. |

Squamish, British Columbia |

Hydrogen has more economic benefits over battery in terms of storage system. | High Levelized Cost of Energy, GHGs emissions not shown in results. |

[14] |

| Michela L. et al. |

Red Lake, Ontario | Alternative for fossil fuel-based electricity. | High NPC due to addition of Hydro in HRES. |

[15] |

| Arabzadeh S.et al. | Winnipeg, Manitoba | Diesel-based wind system with battery storage | Less than 1% of renewable energy fraction for the proposed model. |

[16] |

| Roshani K.et al. | Northern Manitoba |

Diesel-based hybrid energy system. | High LCOE, Payback period & GHGs emissions. |

[17] |

| Tazrin P. et al. |

Trout Lake, Alberta |

Fuel Cell based Pv/Battery /Wind hybrid energy system |

Comparison of current Energy price with derived LCOE not shown. |

[7] |

- i

- To meet the electricity and heat demand, techno-economic analysis of grid connected tri-brid energy system consisting of PV, wind turbines and battery energy storage system were simulated for Siksika Nation community, near Gleichen, Alberta, Canada.

- ii

- Four different scenarios which are grid only, PV-grid, Wind turbine-grid and WT-PV-Grid were developed in HOMER and compared for the best combination of hybrid energy system, in accordance with Net Present Values (NPV), LCOE, Capital Expense (CAPEX), Operation Expense (OPEX) and emissions/year.

- iii

- To reduce the current electricity prices by generating renewable electricity.

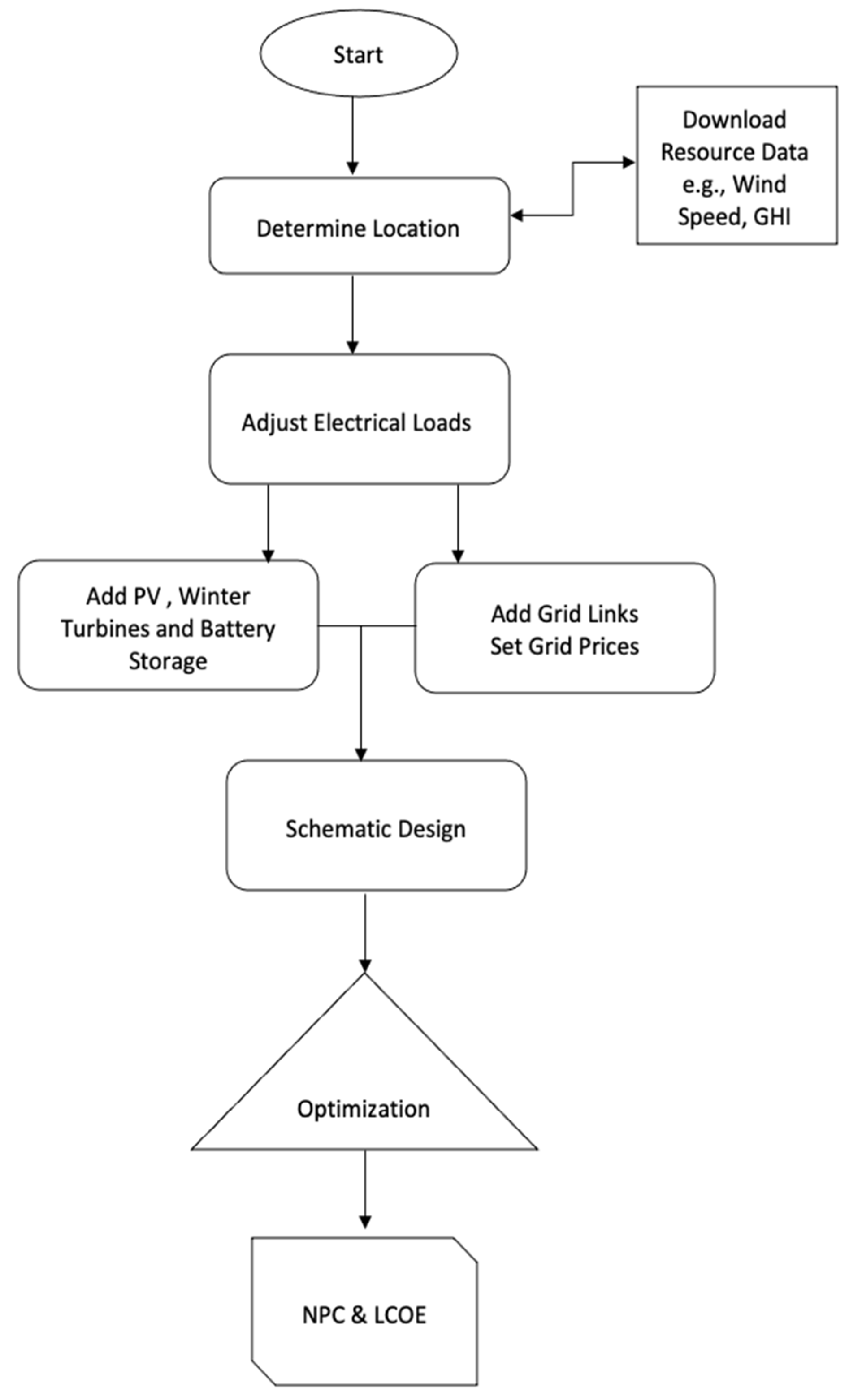

2. Methodology

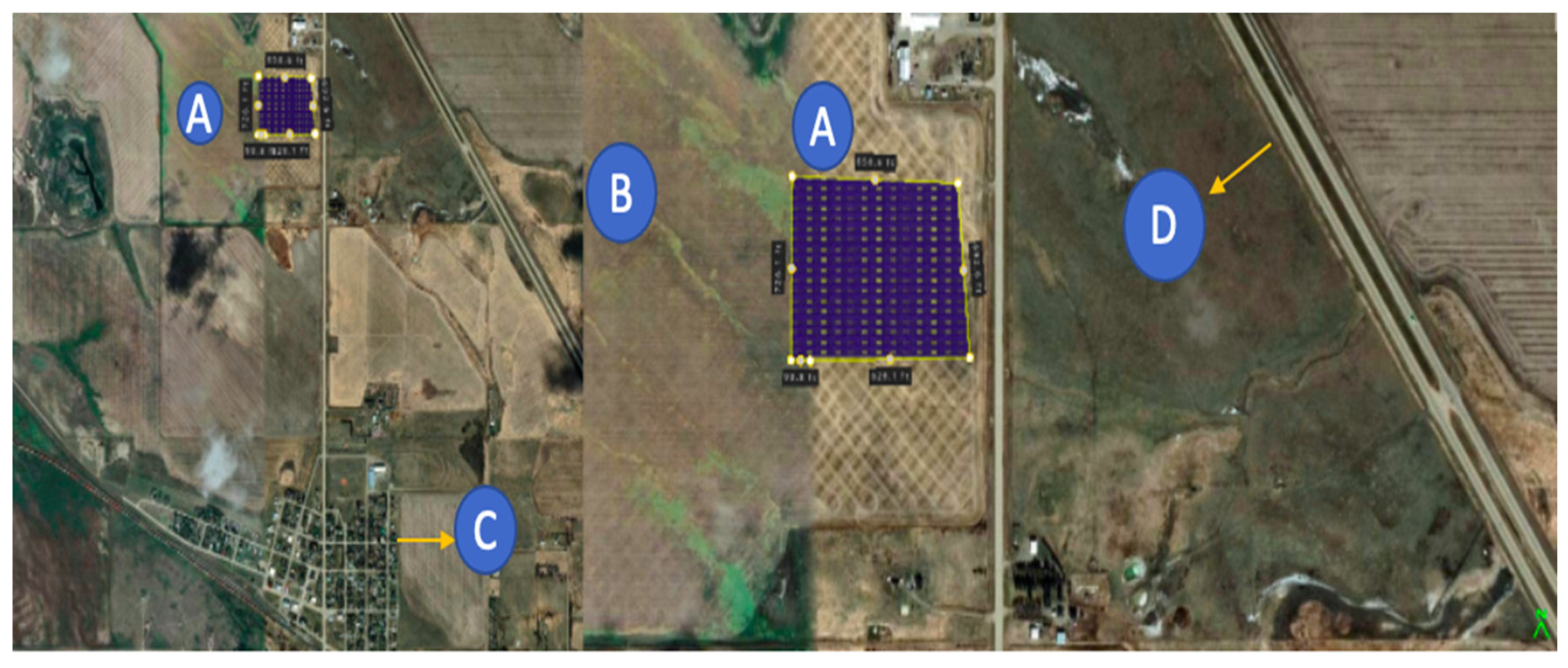

2.1. Site Selection and Load Profile

| Particulars | Description |

|---|---|

| Project Location | Gleichen, Alberta (Reserve Land) |

| Geographical Coordinates | 50° 52’0’’ N, 113°3’0’’ W |

| Population | 7800 + |

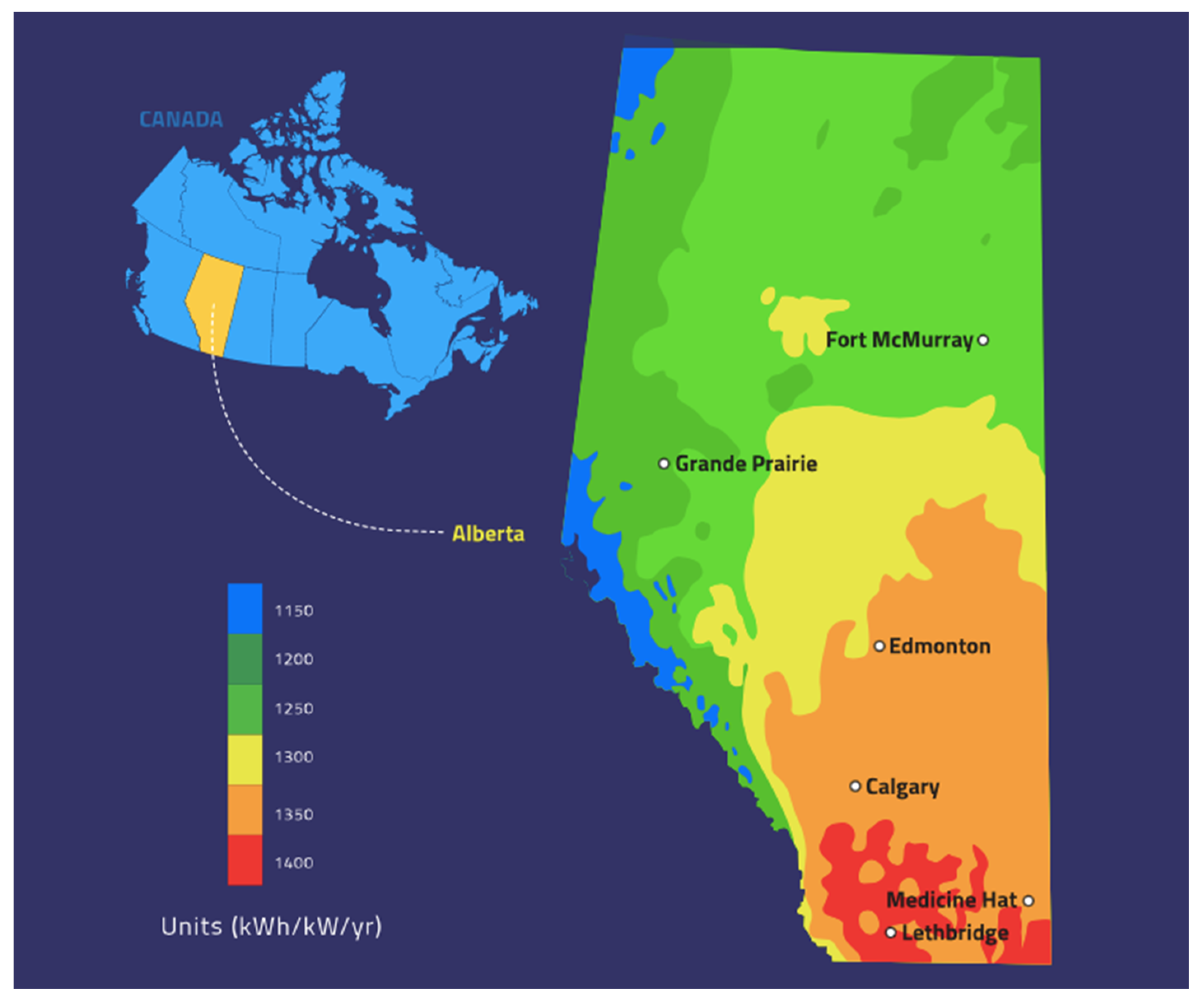

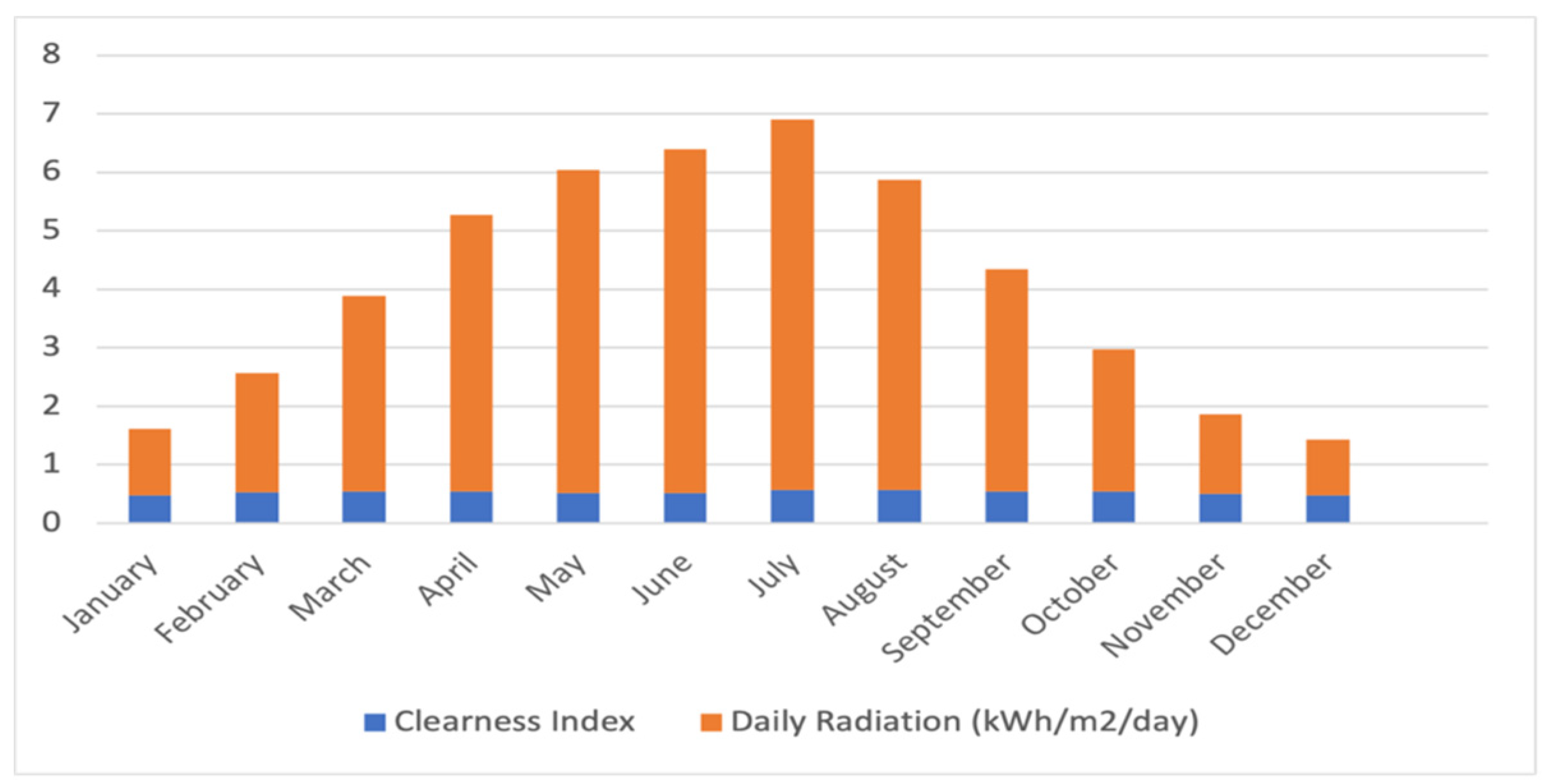

| Daily Average Solar Irradiance Average Solar Irradiance (Summer Solstice) Average Solar Irradiance (Winter Solstice) |

3.57 kWh/m2 5.88 kWh/m2 0.950 kWh/m2 |

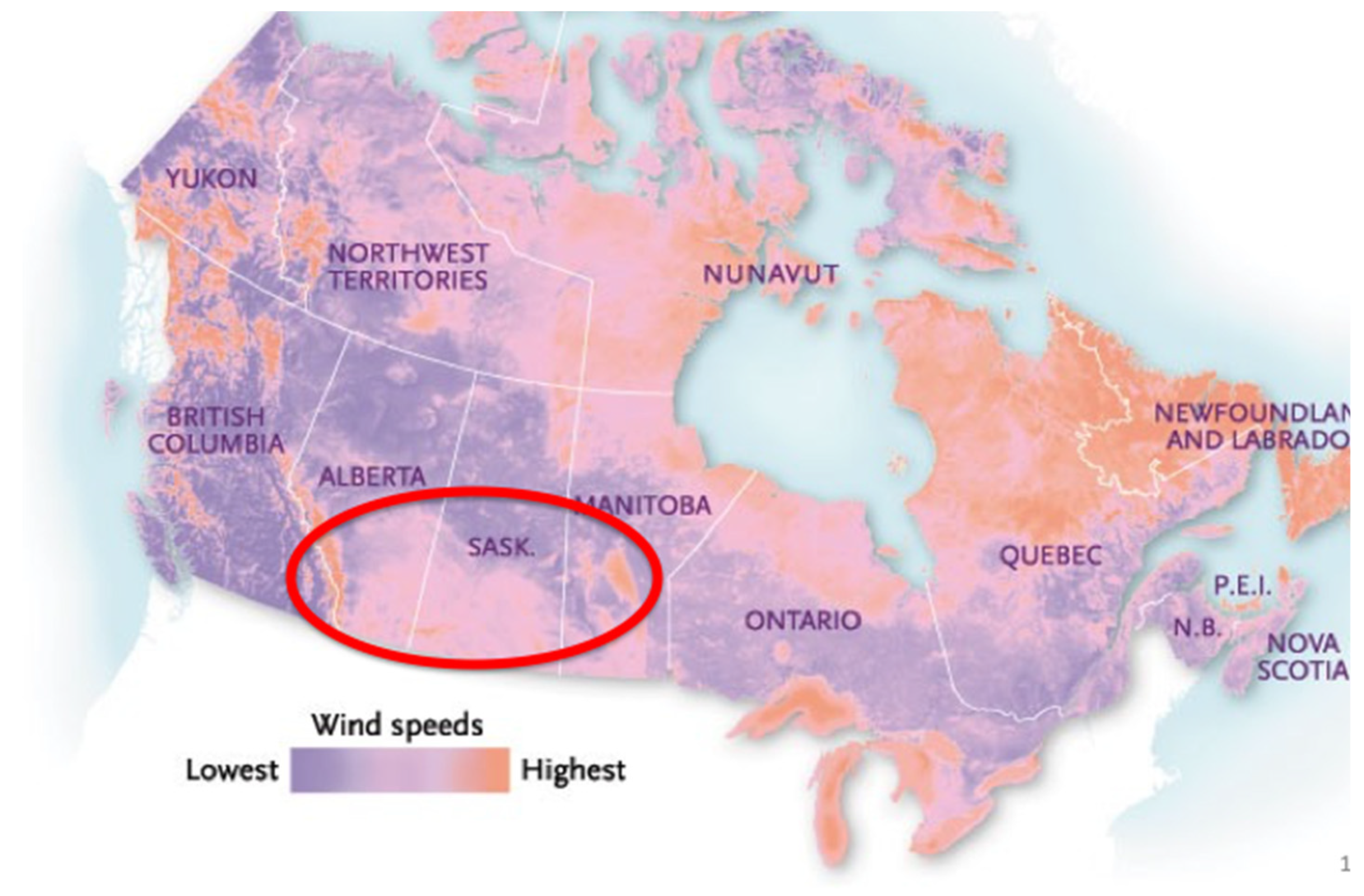

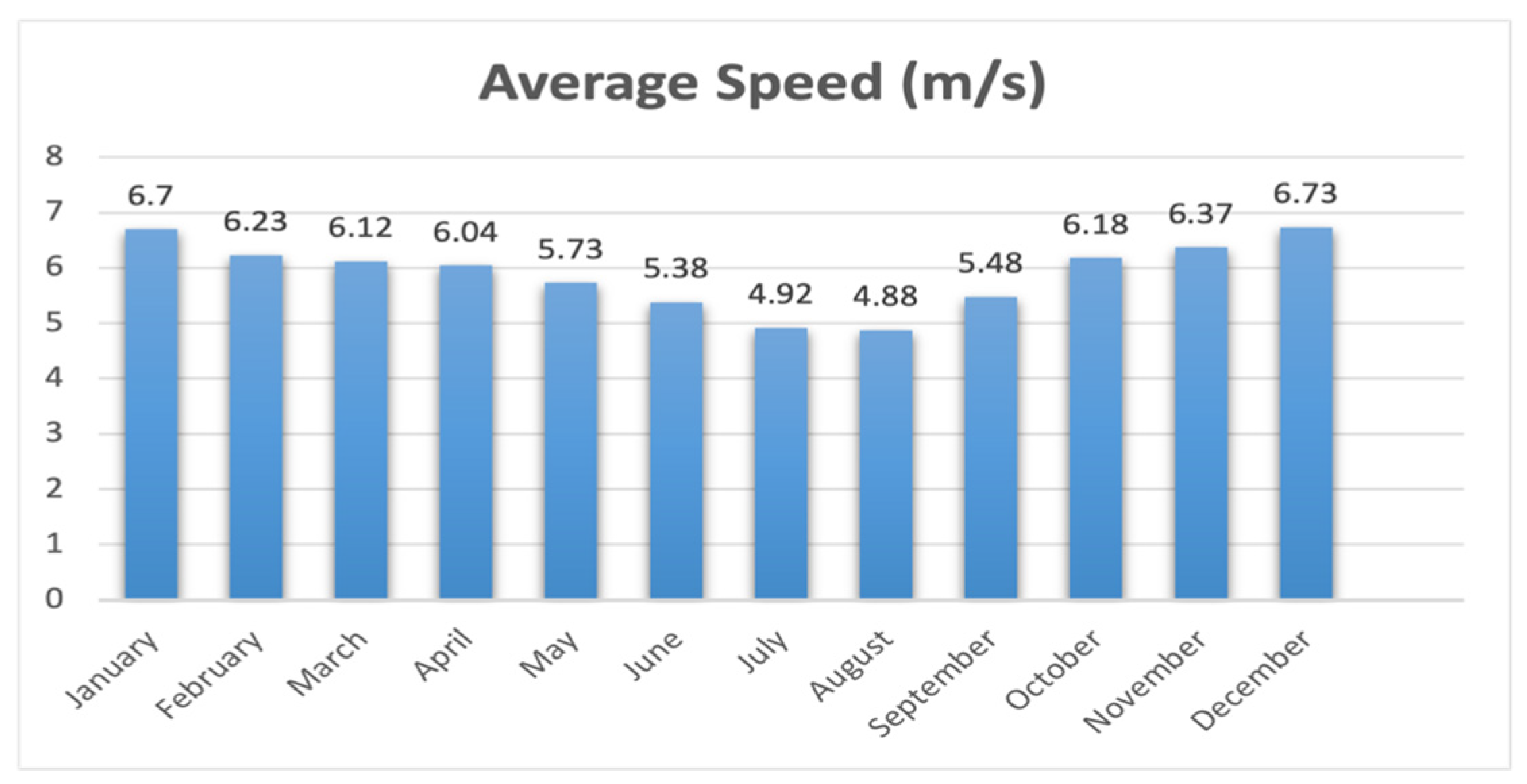

| Annual Average Wind Speed | 5.90 m/s at 80m |

| Annual Wind Speed | 2153.5 m/s at 80m |

2.2. Load Profile

| Metric | Baseline | Scaled |

|---|---|---|

| Average (kWh/day) | 44899 | 44899 |

| Average kW | 1870.83 | 1870.7 |

| Peak (kW/day) | 5412.12 | 5412 |

| Load Factor | 0.35 | 0.35 |

2.3. Wind Speed Data

2.4. Solar GHI Data

3. Mathematical Modeling

3.1. Solar Photovoltaic System

3.2. Wind Turbine System

3.3. Performance Factors for Techno-Economic Analysis

3.3.1. Net Present Cost

3.3.2. Levelized Cost of Energy

3.3.3. Total Annualized Cost

3.4. System Strategy

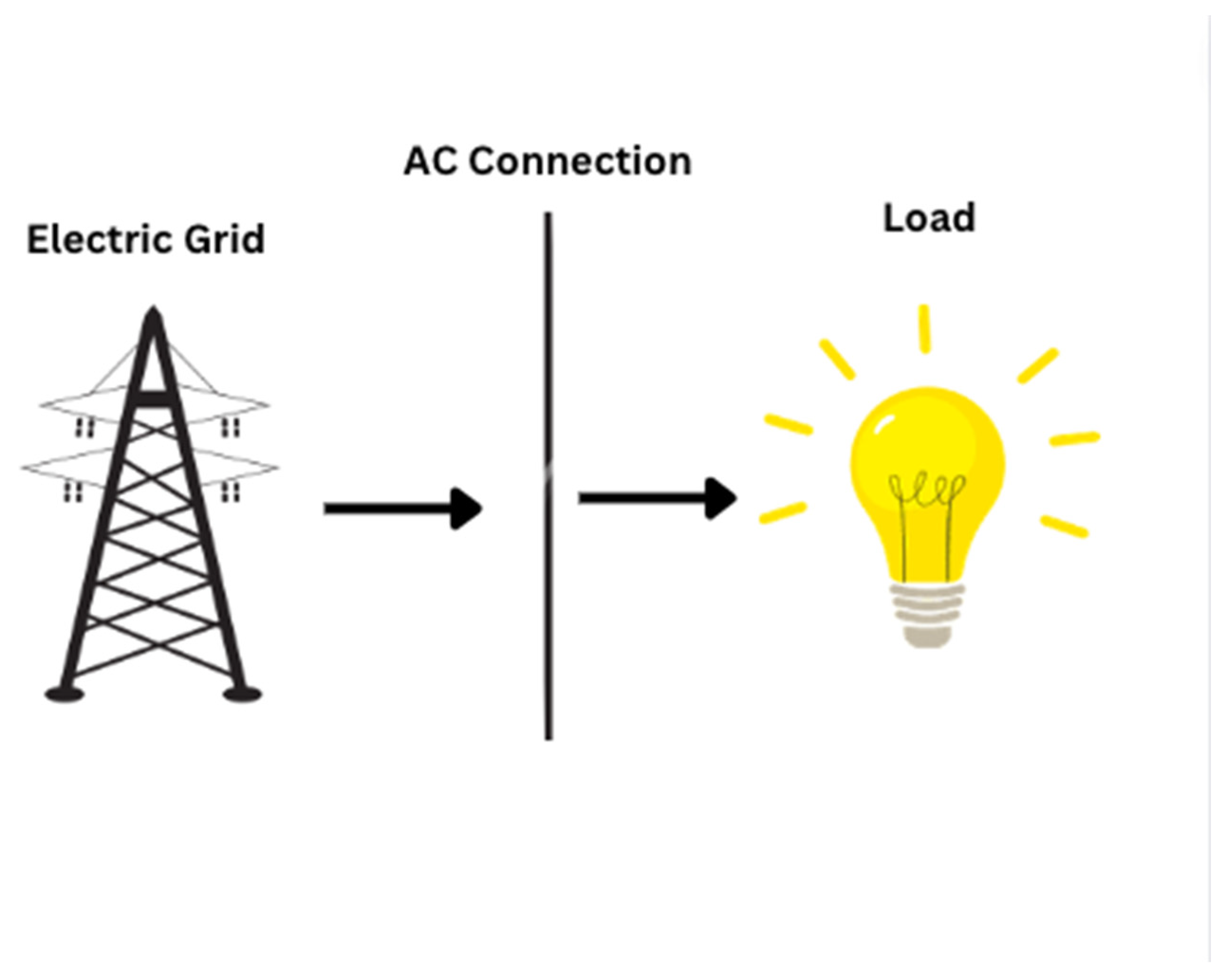

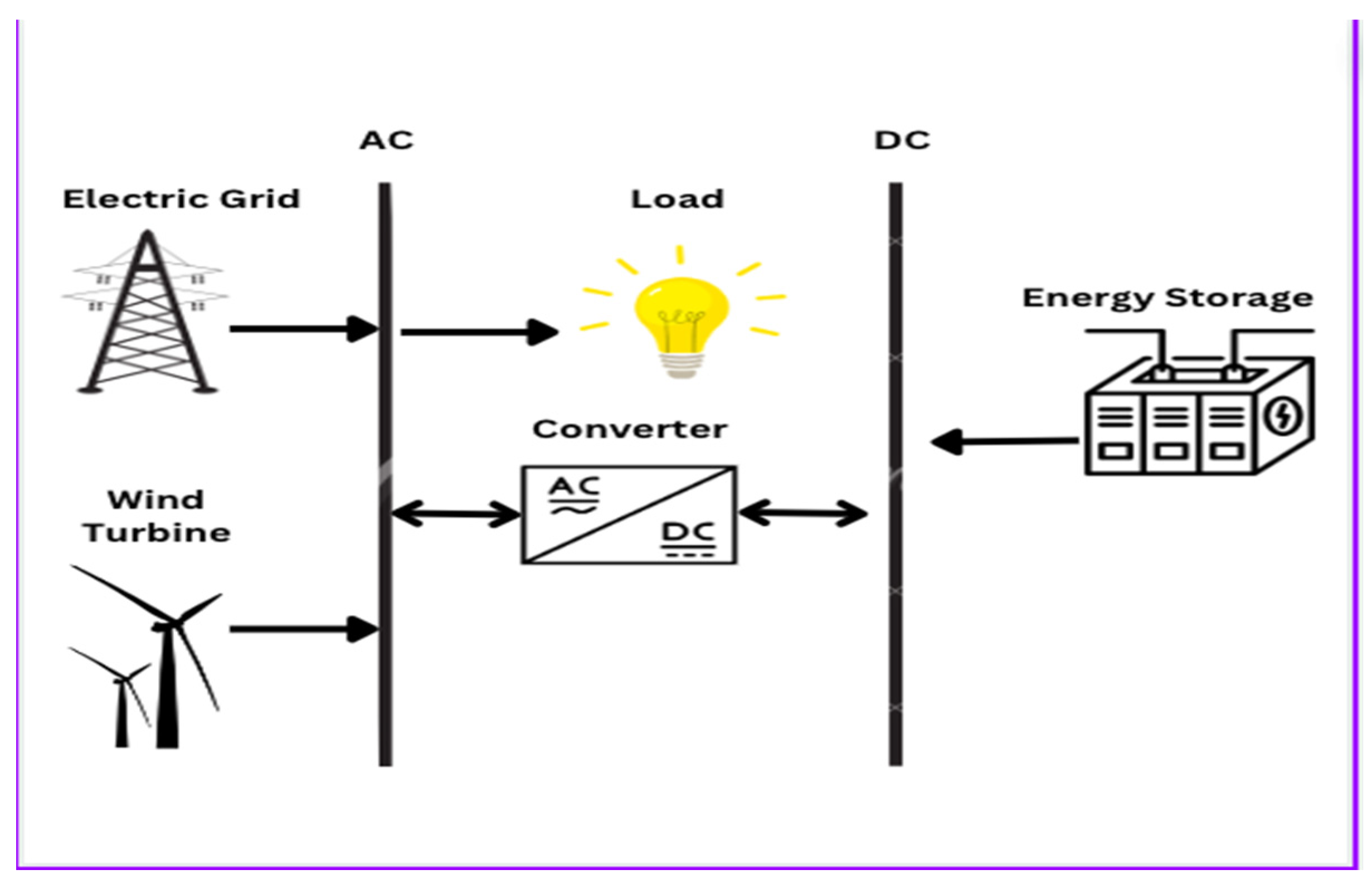

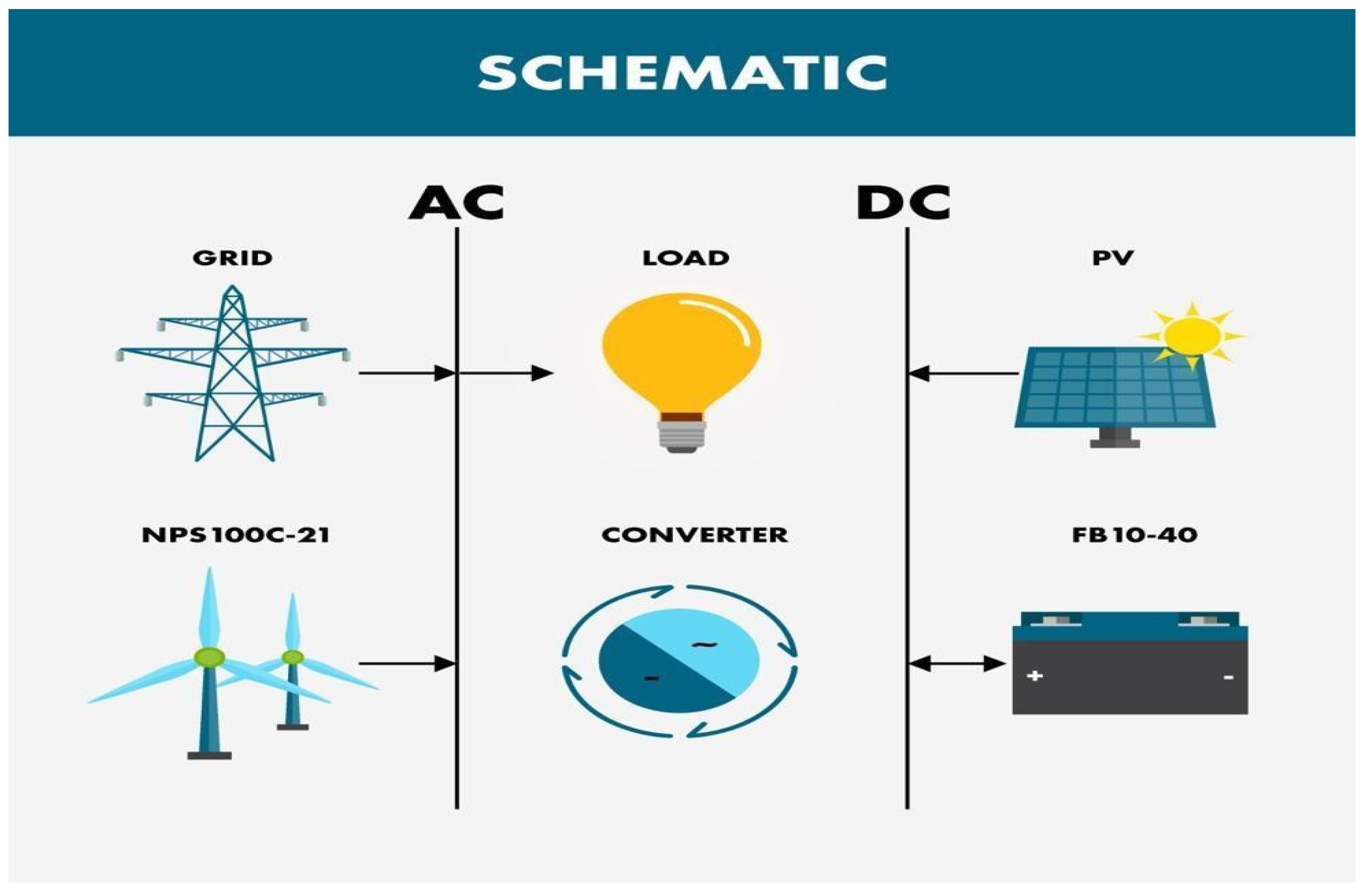

3.4.1. National Grid Configuration

| Serial Number | Energy Providers | Energy Rates ($/kWh) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Spotpower | 0.127 |

| 2 | ATCO Energy | 0.123 |

| 3 | ENCOR | 0.127 |

| 4 | Easy Max | 0.127 |

| 5 | Just Energy | 0.144 |

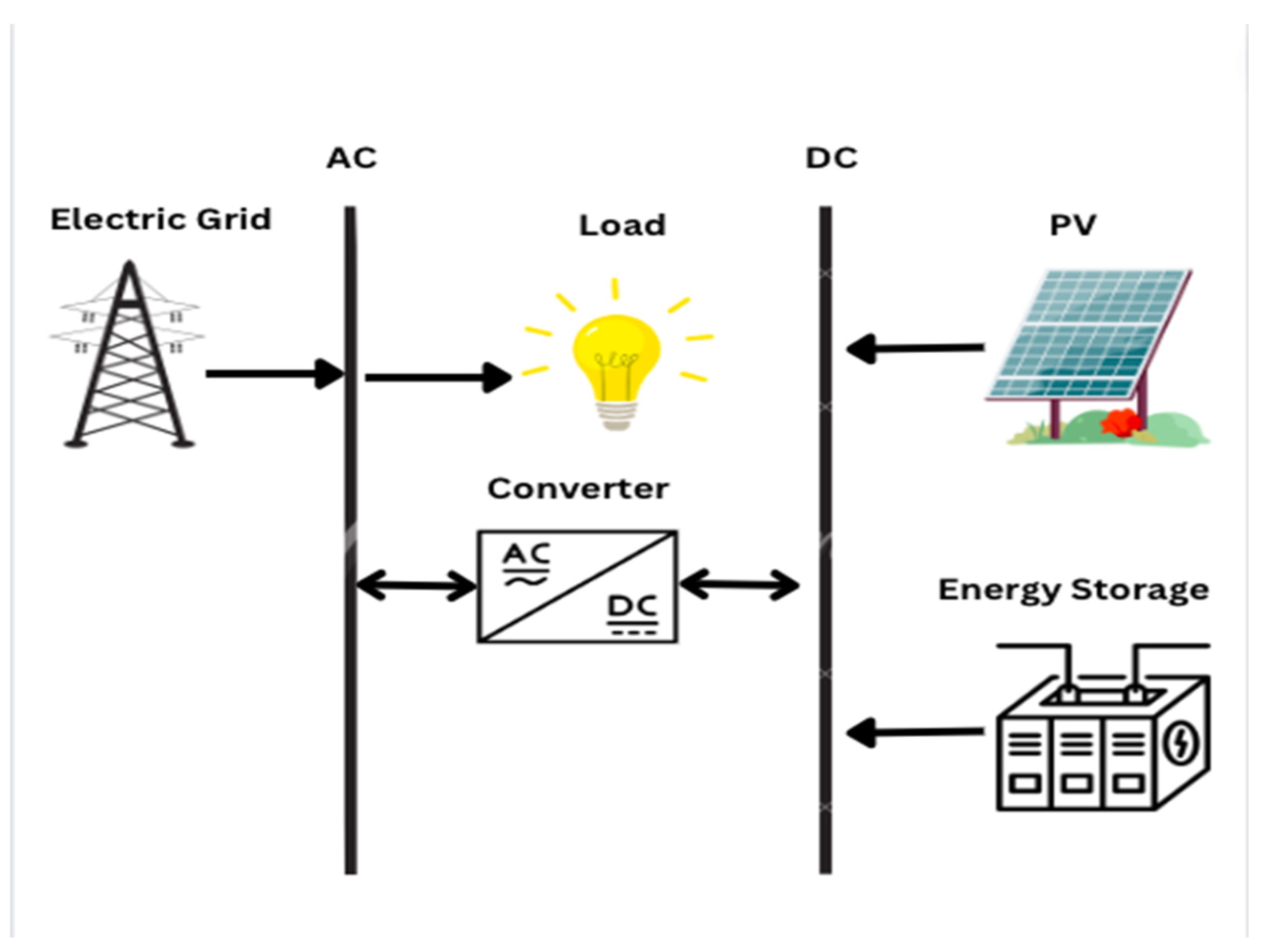

3.4.2. Grid-Tied PV System

3.4.3. Grid-Tied WT System

3.4.4. Grid-Tied PV-WT System

4. Results and Discussion

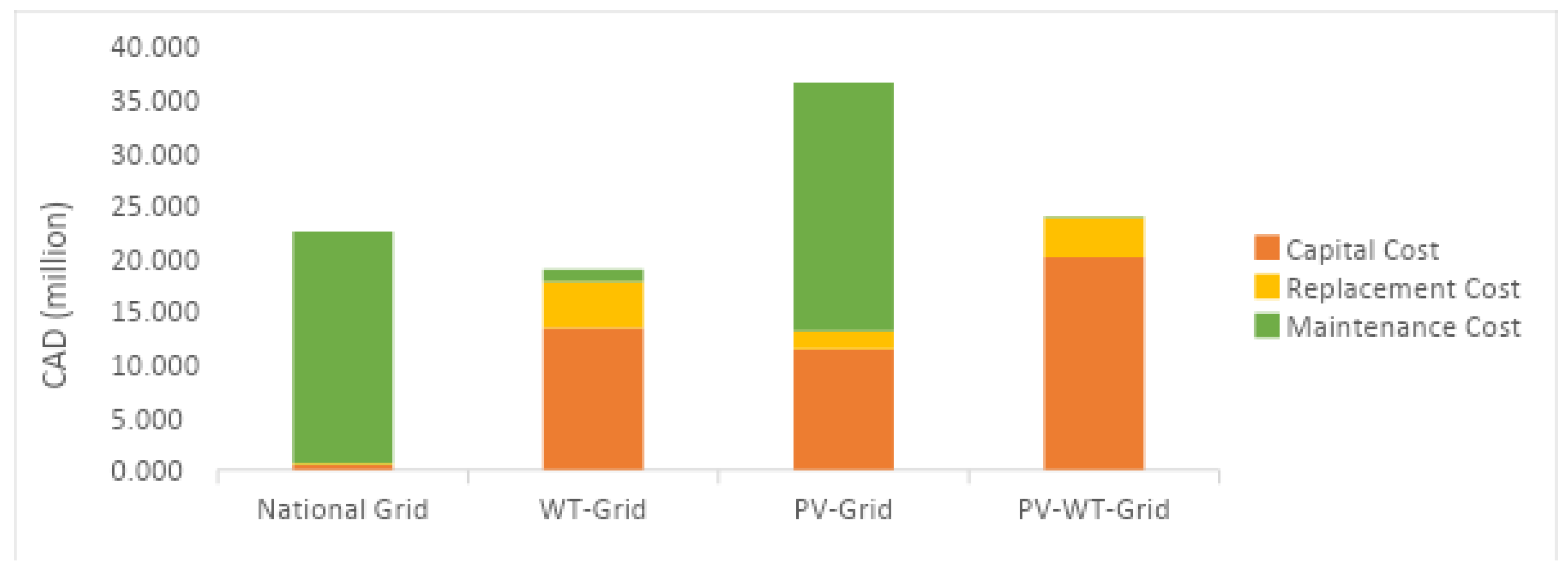

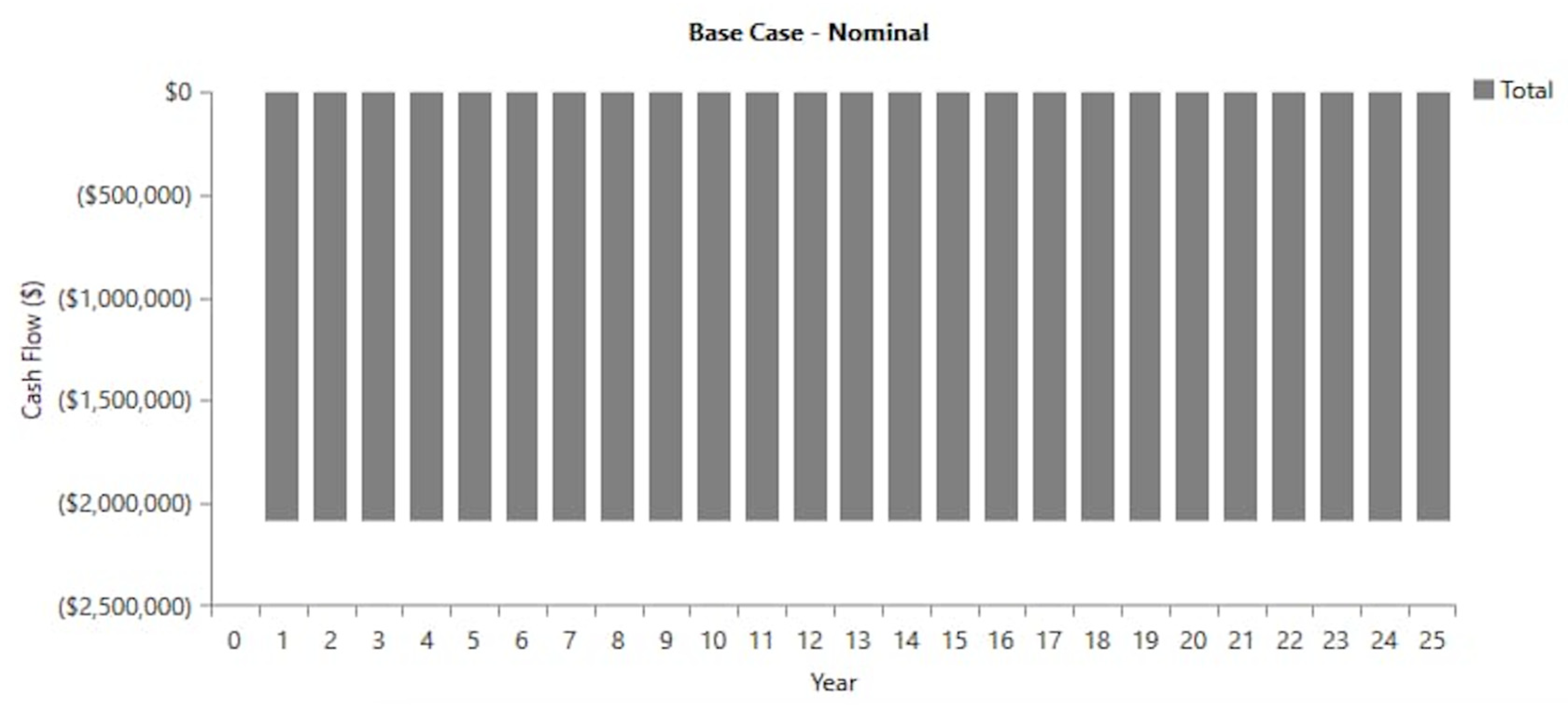

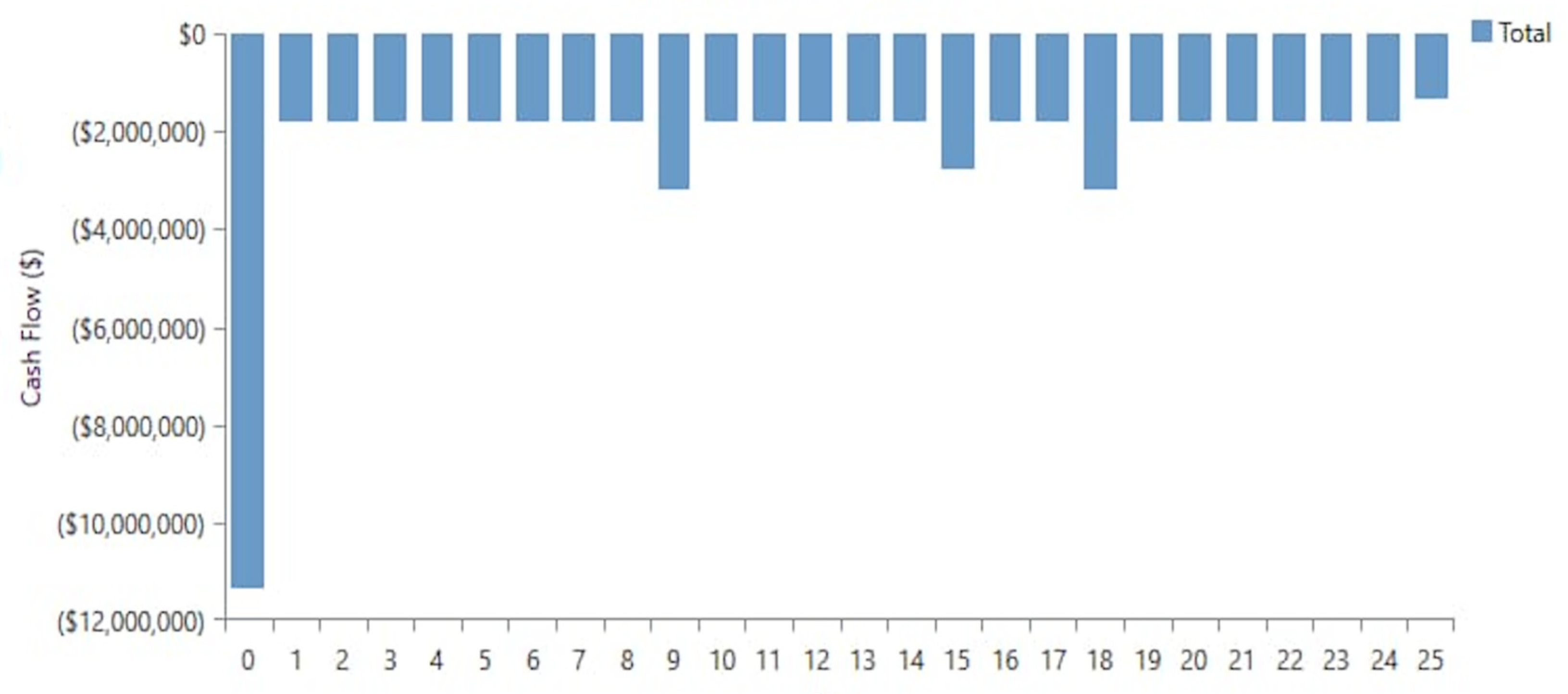

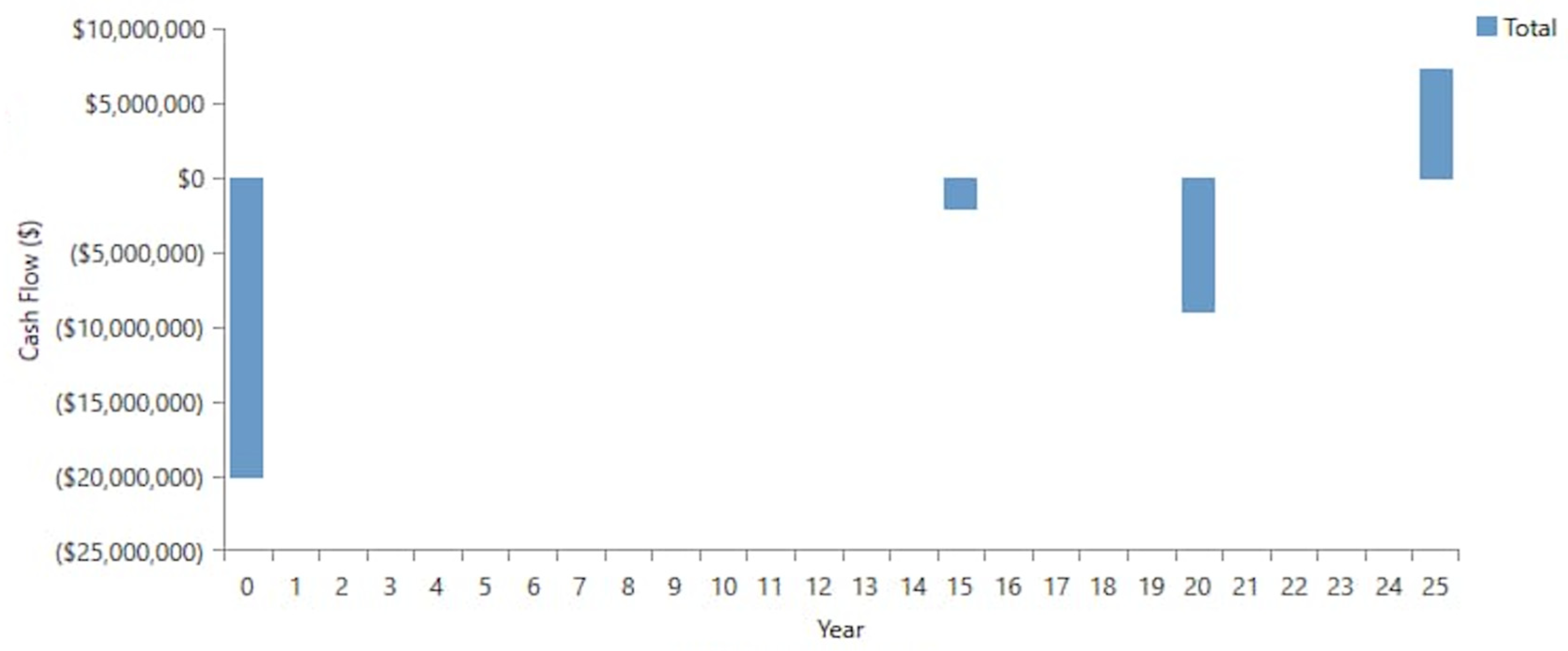

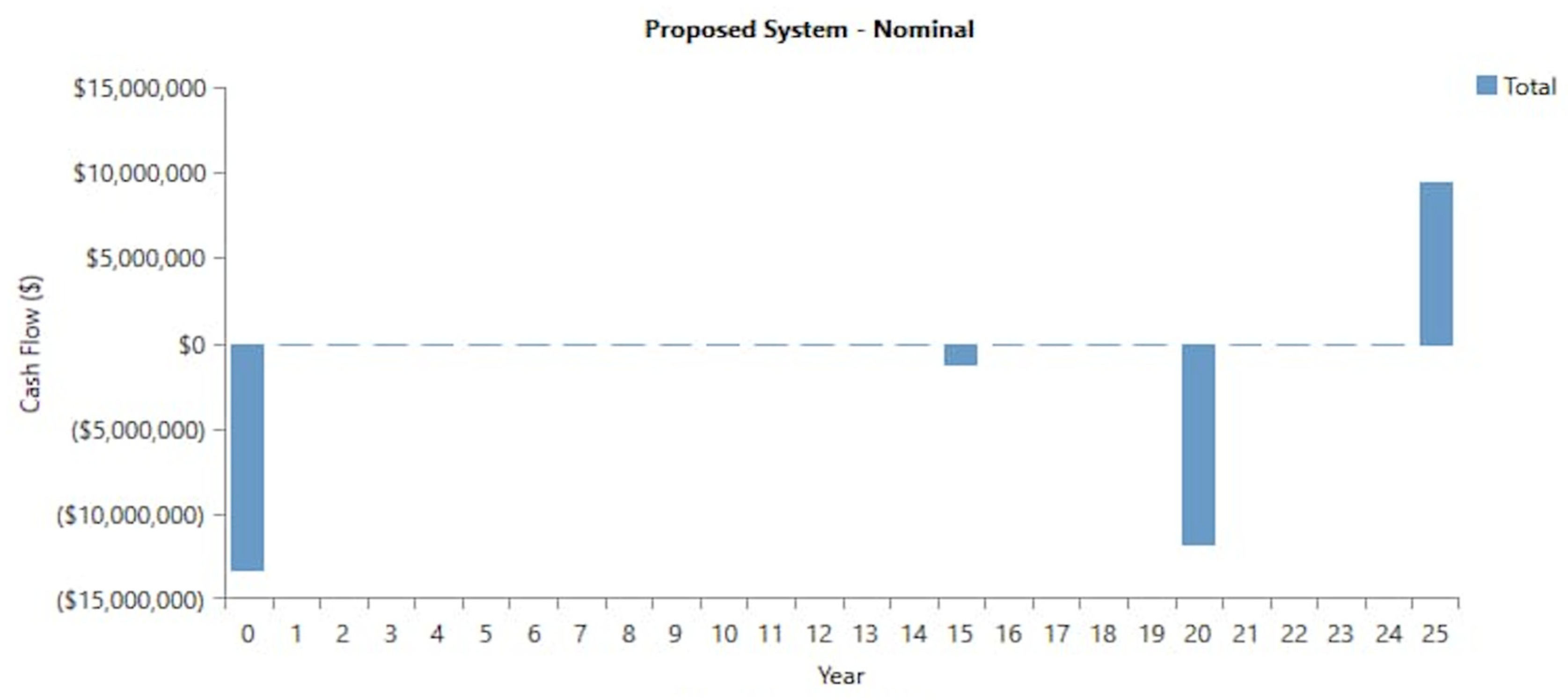

Techno-Economic Analysis and Comparison of System Configurations

| Parameter | Unit | National Grid | Hybrid (WT- Grid) |

Hybrid (PV-Grid) |

Hybrid (PV-WT- Grid) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LCOE | CAD/kW | 0.127 | 0.0412 | 0.172 | 0.0705 |

| Net Present Value (NPV) | CAD (Million) | 22.4 | 14.4 | 36.4 | 22.3 |

| Capital Cost | CAD (Million) | 0.430 | 13.4 | 11.4 | 20.1 |

| Replacement Cost | CAD (Million) | 0.182 | 4.4 | 1.7 | 3.7 |

| Maintenance Cost | CAD (Million) | 21.816 | 1.1 | 23.45 | 0.12 |

| Salvage Value | CAD (Million) | 0.034 | 2.2 | 0.11 | 1.7 |

| IRR | % | - | 15 | 9.4 | 8.3 |

| ROI | % | - | 11 | -2.8 | 5.6 |

| Payback Period | Yrs | - | 6.18 | 9.21 | 9.72 |

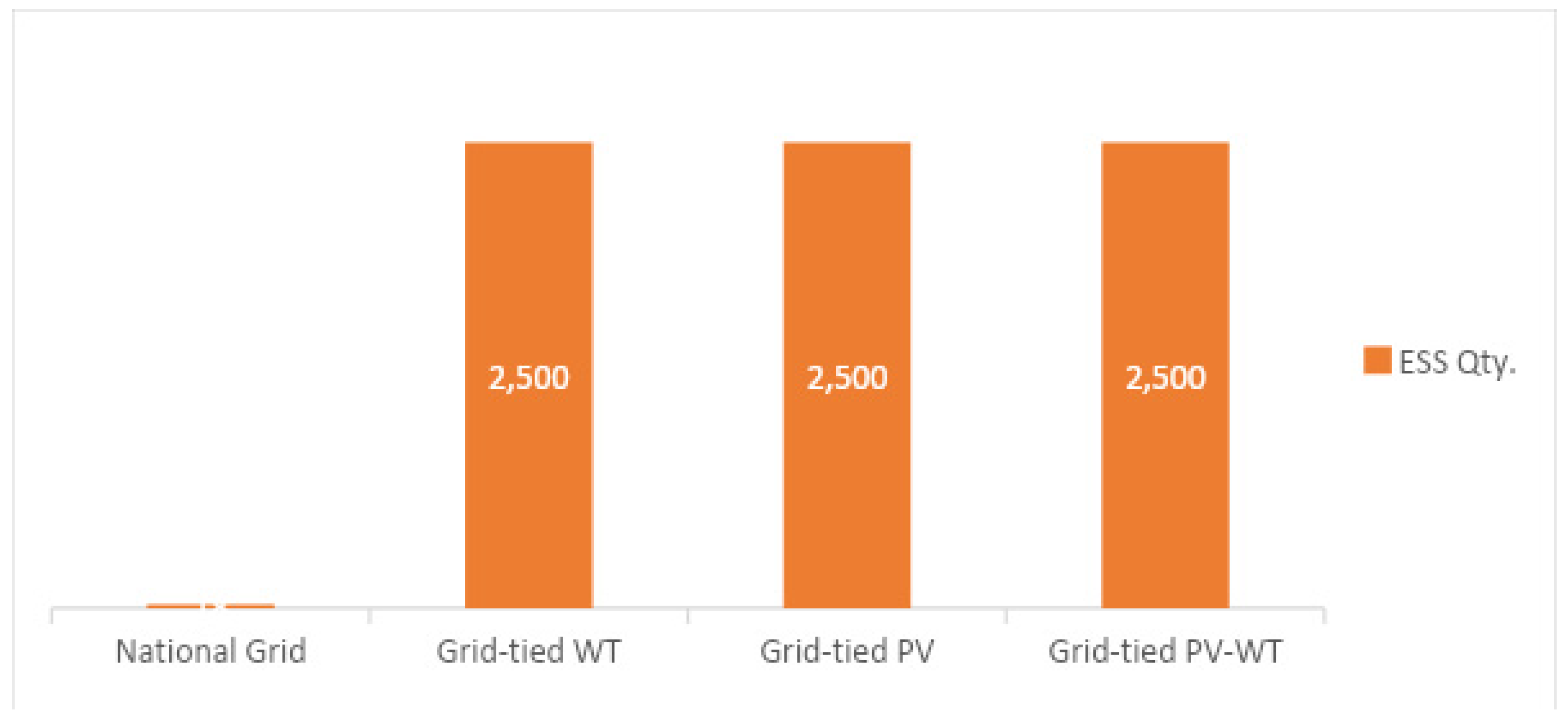

| ESS Qty. | Battery | 18 | 2500 | 2500 | 2500 |

| System Autonomy | Hr. | 0.922 | 1.07 | 1.07 | 1.07 |

| Renewable Fraction | % | - | 79.6 | 24.1 | 80 |

| Energy Purchased | kWh | - | 5,520,959 | 13,860,187 | 5,030,628 |

| Energy Sold | kWh | - | 10,660,754 | 19,156 | 8,023,980 |

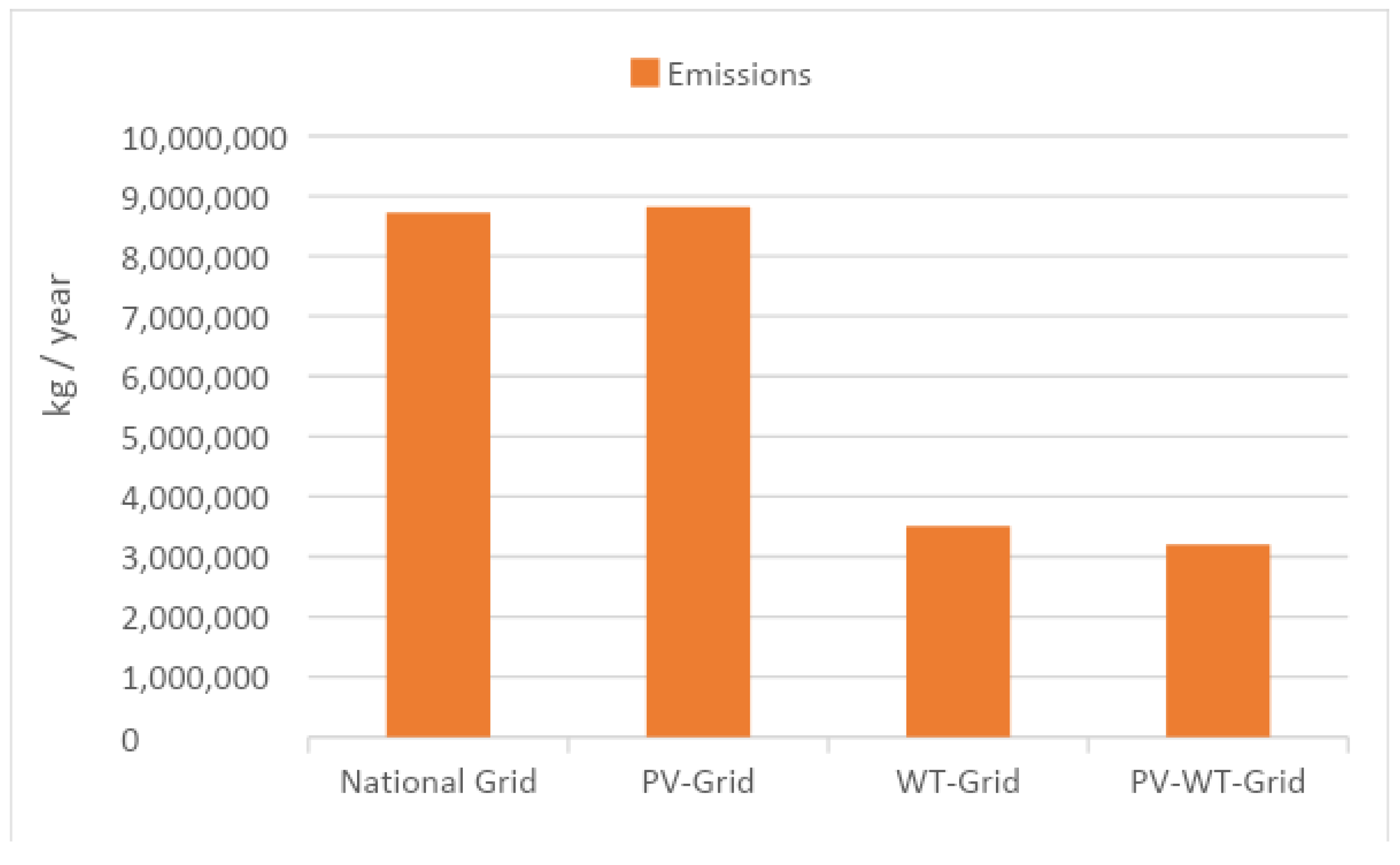

| Total Emissions | kg/yr. | 8,719,564 | 3,511,711 | 8,816,188 | 3,199,882 |

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Data Availability Statement

References

- Nikzad, R.; Sedigh, G. Greenhouse Gas Emissions and Green Technologies in Canada. Environ. Dev. 2017, 24, 99–108. [CrossRef]

- Hosseini, S.M.; Kanagaraj, N.; Sadeghi, S.; Yousefi, H. Midpoint and Endpoint Impacts of Electricity Generation by Renewable and Nonrenewable Technologies: A Case Study of Alberta, Canada. Renew. Energy 2022, 197, 22–39. [CrossRef]

- Hastings-Simon, S.; Leach, A.; Shaffer, B.; Weis, T. Alberta’s Renewable Electricity Program: Design, Results, and Lessons Learned. Energy Policy 2022, 171, 113266. [CrossRef]

- Jamil, U.; Pearce, J.M. Energy Policy for Agrivoltaics in Alberta Canada. Energies 2023, 16, 53. [CrossRef]

- Martins Godinho, C.; Noble, B.; Poelzer, G.; Hanna, K. Impact Assessment for Renewable Energy Development: Analysis of Impacts and Mitigation Practices for Wind Energy in Western Canada. Impact Assess. Proj. Apprais. 2023, 41, 59–70. [CrossRef]

- Bensalah, A.; Barakat, G.; Amara, Y. Electrical Generators for Large Wind Turbine: Trends and Challenges. Energies 2022, 15, 6700. [CrossRef]

- Priyanka, T.J.; Atre, S.; Billal, M.M.; Arani, M. Techno-Economic Analysis of a Renewable-Based Hybrid Energy System for Utility and Transportation Facilities in a Remote Community of Northern Alberta. Clean. Energy Syst. 2023, 6, 100073. [CrossRef]

- Robertson, B.; Bekker, J.; Buckham, B. Renewable Integration for Remote Communities: Comparative Allowable Cost Analyses for Hydro, Solar and Wave Energy. Appl. Energy 2020, 264, 114677. [CrossRef]

- Canada, E. and C.C. Greenhouse Gas Emissions Available online: https://www.canada.ca/en/environment-climate-change/services/environmental-indicators/greenhouse-gas-emissions.html (accessed on 14 March 2024).

- Ur Rashid, M.; Ullah, I.; Mehran, M.; Baharom, M.N.R.; Khan, F. Techno-Economic Analysis of Grid-Connected Hybrid Renewable Energy System for Remote Areas Electrification Using Homer Pro. J. Electr. Eng. Technol. 2022, 17, 981–997. [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Zhou, D.; Zheng, Y. Techno-Economic Comparative Study of Grid-Connected PV Power Systems in Five Climate Zones, China. Energy 2018, 165, 1352–1369. [CrossRef]

- Kapoor, S.; Sharma, A.K. Techno-Economic Analysis by Homer-pro Approach of Solar on-Grid System for Fatehpur-Village, India. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2021, 2070, 012146. [CrossRef]

- Das, B.K.; Alotaibi, M.A.; Das, P.; Islam, M.S.; Das, S.K.; Hossain, M.A. Feasibility and Techno-Economic Analysis of Stand-Alone and Grid-Connected PV/Wind/Diesel/Batt Hybrid Energy System: A Case Study. Energy Strategy Rev. 2021, 37, 100673. [CrossRef]

- Abdin, Z.; Mérida, W. Hybrid Energy Systems for Off-Grid Power Supply and Hydrogen Production Based on Renewable Energy: A Techno-Economic Analysis. Energy Convers. Manag. 2019, 196, 1068–1079. [CrossRef]

- Longo, M.; Yaïci, W.; Foiadelli, F. Hybrid Renewable Energy System with Storage for Electrification €“ Case Study of Remote Northern Community in Canada. Int. J. Smart Grid - IjSmartGrid 2019, 3, 63–72.

- Performance Analysis of a Photovoltaic/Wind/Diesel Hybrid Power Generation System for Domestic Utilization in Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada - Arabzadeh Saheli - 2019 - Environmental Progress & Sustainable Energy - Wiley Online Library Available online: https://aiche.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/ep.12939 (accessed on 14 March 2024).

- Kaluthanthrige, R.; Rajapakse, A.D.; Lamothe, C.; Mosallat, F. Optimal Sizing and Performance Evaluation of a Hybrid Renewable Energy System for an Off-Grid Power System in Northern Canada. Technol. Econ. Smart Grids Sustain. Energy 2019, 4, 4. [CrossRef]

- How HOMER Calculates Wind Turbine Power Output Available online: https://homerenergy.com/products/pro/docs/3.15/how_homer_calculates_wind_turbine_power_output.html (accessed on 14 March 2024).

- Urban, R. Solar Power Alberta (2023 Guide) Available online: https://www.energyhub.org/alberta/ (accessed on 14 March 2024).

- Siksika Nation Available online: https://siksikanation.com/ (accessed on 14 March 2024).

- Government of Canada, S.C. Census Profile, 2021 Census of Population Available online: https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2021/dp-pd/prof/index.cfm?Lang=E (accessed on 14 March 2024).

- How Many kWh Does the Average Home Use? Available online: https://ca.renogy.com/blog/how-many-kwh-does-the-average-home-use/ (accessed on 14 March 2024).

- NASA POWER | Prediction Of Worldwide Energy Resources Available online: https://power.larc.nasa.gov/ (accessed on 14 March 2024).

- Osterwald, C.R. Translation of Device Performance Measurements to Reference Conditions. Sol. Cells 1986, 18, 269–279. [CrossRef]

- Select Alberta Electricity Provider Available online: https://energyrates.ca/select-alberta-electricity-provider/ (accessed on 14 March 2024).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).