1. Introduction

Developing countries have a general track record of supplying energy provision by older technologies such as coal generation stations. In South Africa about seven power plants generate about 85% of its generation capacity of 42 000 MW [

1]. The implementation of renewable energy implementations in these countries are important.

Photovoltaic (PV) integrated flow cells for electrochemical energy conversion and storage underwent a huge development. The advantages of this type of integrated flow cell system include the simultaneous storage of solar energy into chemicals that can be readily utilized for generating electricity [

2].

However, most studies overlook the practical challenges arising from the inherent heat exposure and consequent overheating of the reactor under the sun. This work aims to predict the temperature profiles across PV-integrated electrochemical flow cells under light exposure conditions by introducing a computational fluid dynamic–based method. [

2].

Aligning with ambitious targets and commitments towards carbon neutrality, countries around the world are desperately seeking an energy transition to cope with the stark reality of the climate crisis and the surge in demand for heating and cooling. Increased penetration of renewable power is foreshadowing a shift in global energy dominance, from fossil fuel-based heating to renewable power-based heating. Underlying challenges in energy transition include (1) to achieve heat electrification, (2) to utilize decommissioned thermal power plants, (3) to meet the demand for large-scale heat storage [

3].

Heat pump-assisted approaches to break the bottleneck of energy transition and facilitate effective incentive strategies for policymakers. The efficiency and flexibility of heat pumps in thermal energy regulation enable them to push forward an immense influence on the future energy transition for the heating/cooling supply that accounts for 50 % of the energy consumption for users and the last “10 %” carbon emissions [

3].

Low-temperature thermal energy (<130 °C) recycling and utilization can significantly increase energy efficiency and reduce CO

2 emissions. Among various technologies for heat-to-electricity conversion, thermally regenerative electrochemical cycle (TREC) has garnered significant attention for remarkable efficiency in thermal energy utilization. The thermally regenerative electrochemical cycled flow battery (TREC-FB) offers several advantages, including continuous power output and operating without an external power supply. The goal was to enhance the understanding of how various parameters affect system performance through simulation, thus optimizing cell performance [

4].

Several articles in terms of collection and storage of thermal energy have been published by our group [

5,

6,

7,

8].

In this article, the availability of thermal energy globally, and thermal energy as available locally in a developing country, such as South Africa is surveyed. The power usage in a household in South Africa is discussed. The power of supplying energy to the end user in a developing country such as South Africa is discussed. The possible conversion efficiencies energies into electricity are discussed The possible applications and conversion of Thermal Energy in the household context is discussed. The cost of transport of electricity in South Africa to the metropole cities is discussed. The application of potential high-tech applications such as Nanotechnology is discussed.

2. Materials and Methods

We as authors in South Africa have quite some exposures to energies, renewable energies, photovoltaic (PV) technologies, advanced thermal technologies, including semiconductor sensers [

6,

7,

28,

37]. It hence makes sense to share our sentiments and our most recent research results with the global scientific community, but also locally with dedicated communities.

We have made a recent survey of the available thermal energies available globally, locally in a developing third world country, such as South Africa; look at the typical household energy needs, and see how renewable energies, such as the better utilization of thermal energy can be utilized in household context. Some advanced technological applications were investigated and are presented and proposed in this article.

This approach makes sense against the background by the pledge to reduce the consumption of fossil fuels, the rising temperature of earth and its atmosphere of about 1.5 degrees Celsius, and locally observed climate changes.

We have used both published previous literature to complete surveys of available energy supplies globally.

The Thermal energies have been empirically researched and empirically measured in South Africa using appropriate calibrated measuring equipment.

All costs were derived in ZAR currency values.

3. Results

3.1. Solar Thermal Energy as Available Globally

The radiative energy output from the sun derives from a nuclear fusion reaction. In every second about 6 x 10

11 kg of H

2 is converted to He, with a net mass loss of about 4 x 10

3 kg, which is converted through the Einstein relation:

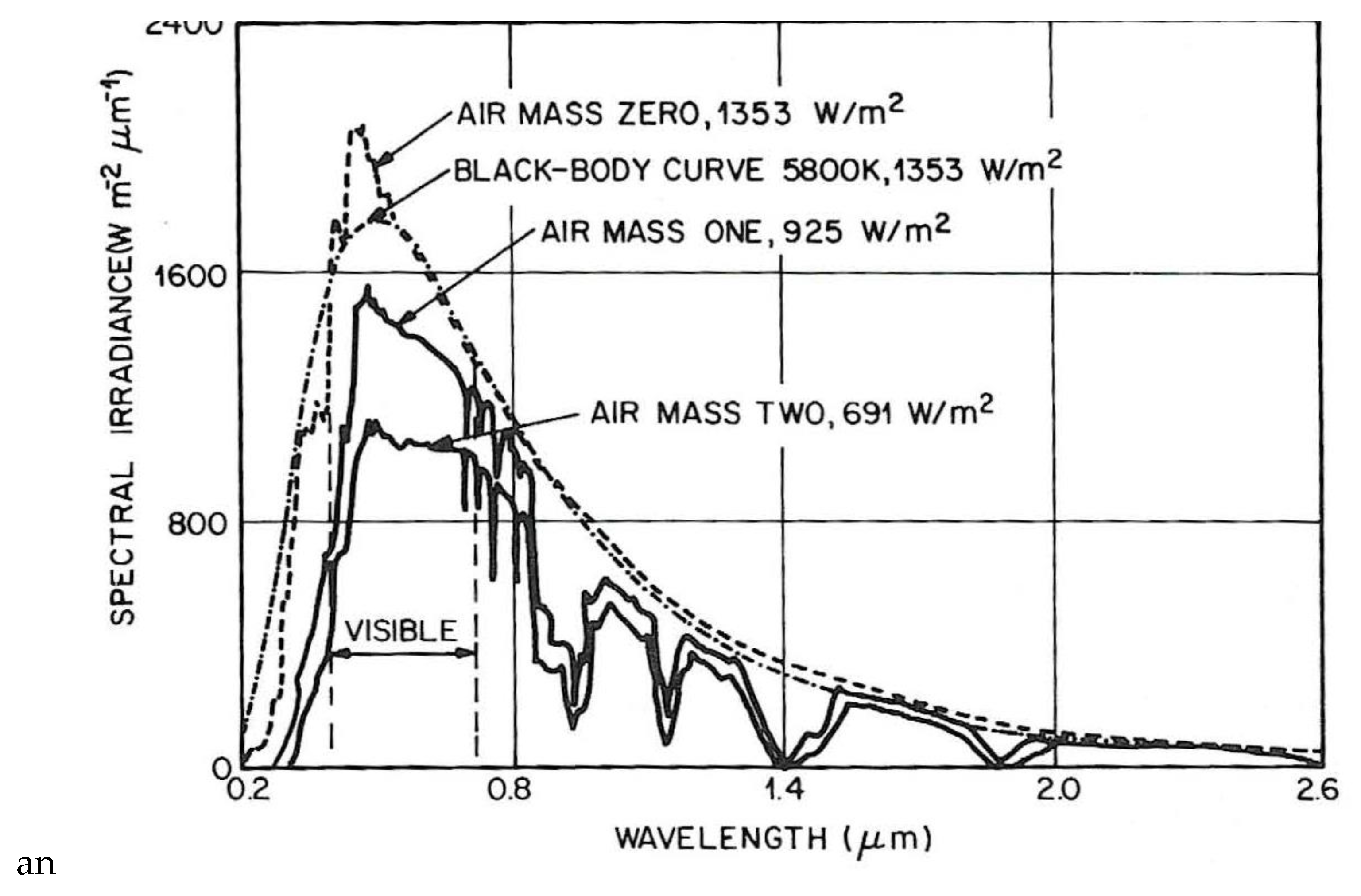

This energy is emitted primarily as electromagnetic radiation in the ultraviolet to infrared and radio spectral regions (0.2 to 3 μm). The total mass of the sun is now about 2 x 1030 kg, and a reasonably stable life with a nearly constant radiative energy output of over 10 billion (1010) years is projected. The intensity of solar radiation in free space at the average distance of the earth from the sun is defined as the solar constant with a value 1353 W /m2. {8}

The atmosphere attenuates the sunlight when it reaches the earth's surface, mainly due to water-vapor absorption in the infrared, ozone absorption in the ultraviolet, and scattering by airborne dust and aerosols. The degree to which the atmosphere affects the sunlight received at the earth's surface is defined by the "air mass." [

8].

The sun rays reaches earth surface through an angle, θ, related to

Obviously the small the angle of incidence, the longer is the earths absorption path length. This relates also to the “air mass”. Incident light rays sees a longer atmospheric path length relative to the minimum path length when the sun is directly overhead.

Figure 1 shows four curves related to solar spectral irradiance (power per unit area per unit wavelength) [

8,

9]. The upper curve which represents the solar spectrum outside the earth's atmosphere, is the air mass zero condition (AM0). This condition can be approximated by a 5800 K black body, as shown by the dashed-dotted curve. The AM0 spectrum is the relevant one for satellite and space-vehicle applications. The AM 1 spectrum represents the sunlight at the earth's surface when the sun is at zenith; the incident power is about 925 W/m

2. Air mass 1.5 conditions (sun at 45° above the horizon) represent a satisfactory energy-weighted average for terrestrial applications, and is 844 Watts/m

2. AM2 spectrum is for θ = 60 degrees incidence angle and has an incident power of about 691 W/m

2.

To convert the wavelength to photon energy, we have used the relationship, [

1]

For solar energy generation, it is good to know what intensity of solar energy can be expected during the year in various locations. The worldwide distribution of solar energy in terms of sunshine duration is shown in

Figure 2. The contour lines enclose regions that receive an average of about 8 or more hours of sunshine daily. Since all continents have sufficiently large areas covered by high average irradiation, extensive worldwide utilization of solar energy can be expected in the future [

8,

9].

3.2. Solar Thermal Energy in a Developing Third World Country such as South Africa

Figure 3 shows the long-term average solar irradiation values as recorded for South Africa in term of kWh/m

2 for the various regions. On average, South Africa has the second-highest solar irradiation in the world, after Arizona in the USA, with an average of 20 MJ /m

2 per year or 6.5 kWh per day [

2,

7].

Figure 4 shows the spectral energy density in terms of W/m

2/ nm wavelength of incident solar radiation [

8]. The irradiation levels irradiation that reaches the surface of the earth, are shown. A radiation density of 0.25 W/m

2 /nm wavelength is shown for the ultraviolet region, 1.25 W/m

2 /nm wavelength for the visible, and 0.50 W/m

2/nm wavelength for the infrared region.

If the spectral density is multiplied with the total bandwidth of irradiation in each region, we derive, respectively, 3.75 W/m2 for the ultraviolet radiation, 250 W/m2 for the visible region, and 500W/m2 for the infrared wavelength region. The infra-red long-wavelength region, therefore, hosts about twice as much energy as the visible region, and about 120 times as much as the ultraviolet region.

Using the above statistics, and it is calculated that about 80 times more energy can be absorbed with thermal energy absorber system per square meter as compared to PhotoVoltaic (PV) cells (using a 10% conversion efficiency as achieved on average for commercially available cells, and a potential 80% average absorption of thermal energy for black thermal absorbers).

3.3. Global and Locally Observed Climate Changes

Globally it is currently observed by the authors [

9] that several global climate changes, such as elongated El Nino effects and heat waves that is observed in the Southern Hemisphere. These also conform with research done by international climate research centers [

10].. These include a current buildup of thermal energy in the Pacific Ocean, presumably assisted by the increase in cloud cover and carbon dioxide in the atmosphere. This again leads to a reduction in the normal jet stream activities of the earth, leading to slower and stagnant circulation patterns in other continents.

Figure 5 gives a cell phone screenshot of March 2024, showing clear weather patterns which is different and more exuberant as compared to other years in South Africa. (1) A slow cyclone circulation is observed in the central part of the country, leading to a heat wave lasting several weeks in the country. (2) Also, the excessive thermal energy in the system leads presumably to higher atmospheric activity over the Indian ocean, and the formation of a cyclone in the Indian Ocean, moving southwards and effecting weather patterns in the Southern Hemisphere.

Also in the United States of America similar patterns are observed and leads to excessive flooding in certain areas [

15].

3.4. Electricity Usage in an Average Worldwide Household

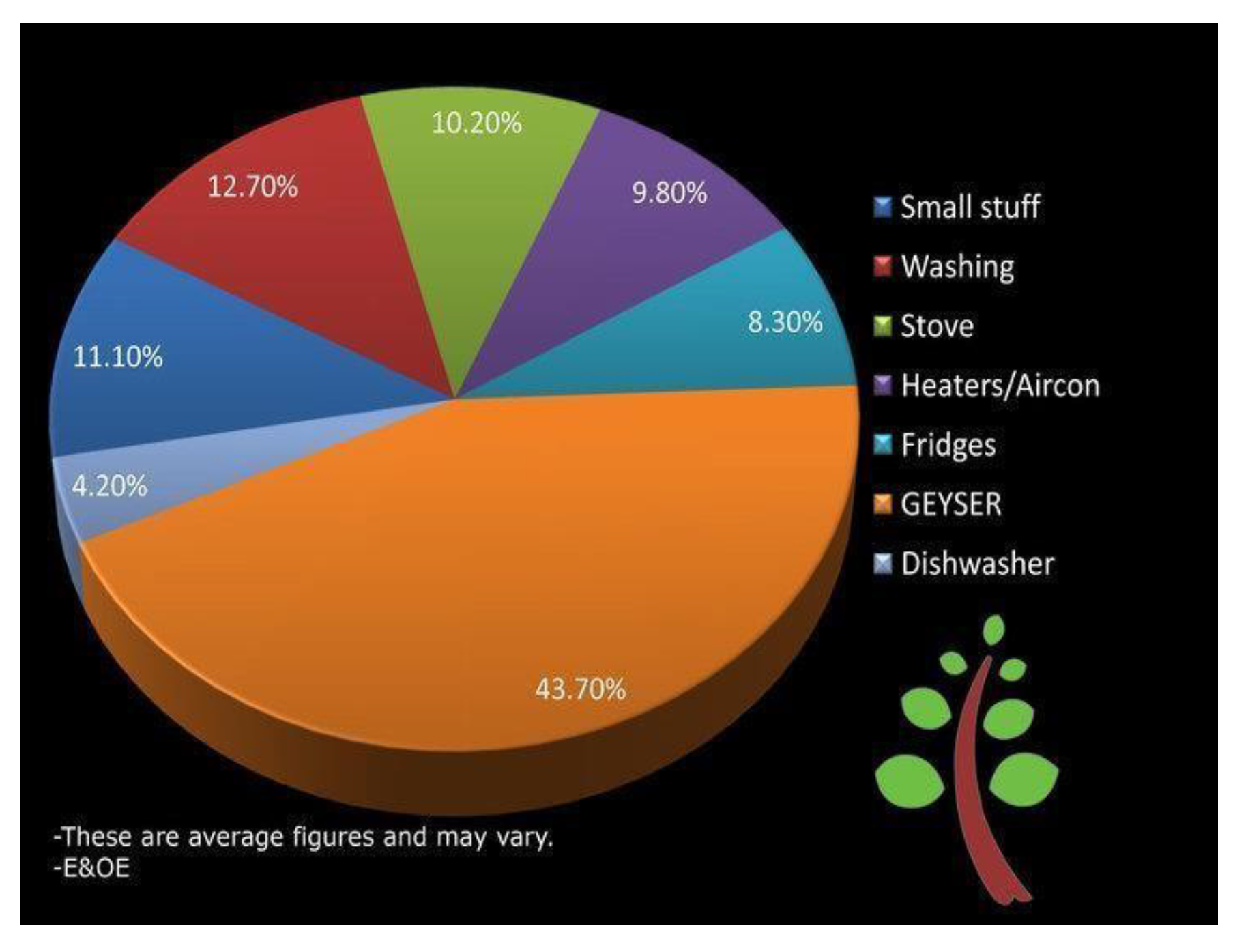

Figure 6 gives an overview of the average energy usage per day by an average household in South Africa. [

11].

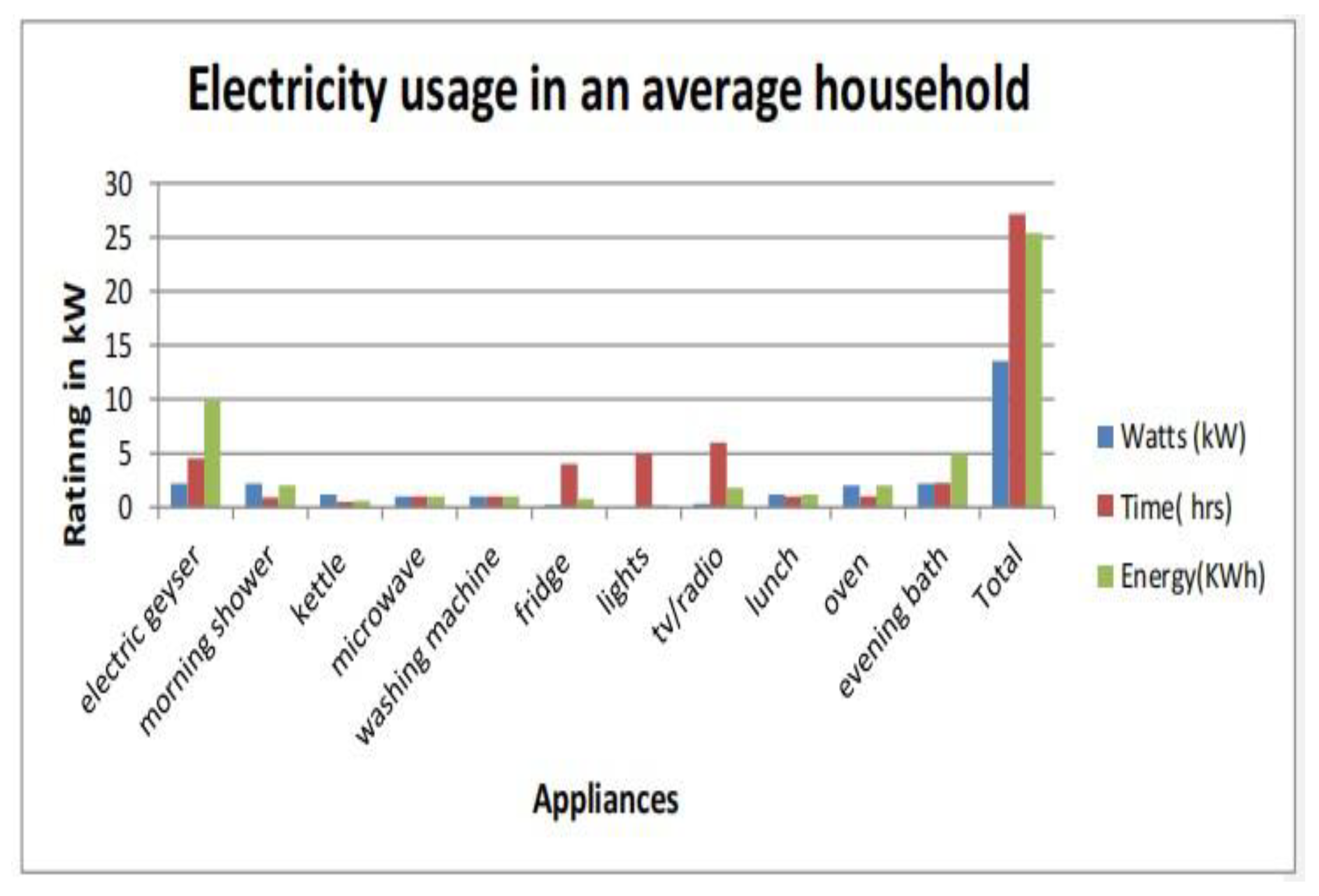

Figure 7 highlighted the kWhrs usage per day [

18] {Seasons}. These should also represent average usage internationally. The high usage of the hot water geyser of about 45 % of all electricity usage and of average 10kWh per day is highlighted. This is followed by the highest usage allocated to watching Television, 1kWhr, and having an evening bath, about 10kWhr. Heating water in a kettle consumes about 2kW of power and about 1kWh per day. These tendencies are primarily related to the fact that water has a high thermal energy capacity to be absorbed in water [

18].

3.5. Some Proposals for Reducing Electricity Usage of a Household in South Africa

With increasing electricity tariffs and inconsistencies alternative sources of energy, such as solar energy. South Africa, as a developing country, is regarded as one of the countries with the best solar energy resources in the world, as it enjoys some of the best sun shines in the world all year round. As a result, the use of solar heating systems may reduce the electricity demand on the national utility resulting in reduction of household electricity bills [

21].

South Africa’s economic growth, coupled with an increasing focus on industrialization and a mass electrification programmed to take power into deep rural areas, has seen a steep increase in the demand for energy. The potential future gap between energy supply and demand is predicted to be large. Majority of power stations in South Africa are coal powered power stations, depending on coal which is a non-renewable resource and is only available in certain areas. These power stations pollute the atmosphere due to production of large amounts of smoke, fumes, and carbon dioxide, also resulting in global warming [

21].

The depleting of resources of fossil fuels and increased costs have led to the development of new and technologically advanced renewable energy sources. Interest in sustainable development and growth has grown in recent years, motivating the development of environmentally benign energy technologies. This involves green technologies which have the smallest possible impact on the environment. Renewable energy sources can be defined as energy obtained from the continuum of repetitive trends of energy recurring in the natural environment, or as resources that are replenished naturally over relatively short periods of time.

3.5.1. Grid Aspects and Transport Costs of Energy and the End User in South Africa

A survey of the costs of supplying electricity to cities and towns on South Africa, reveals that transportation of electricity by power lines is one of the highest contributors to electricity costs to the end user. This requires major infrastructures and especially skyrockets where distances are large, in large suburban areas and rural areas [

20,

21]. Often special governmental and private companies are allocated to this task. Often high solar areas such as solar photovoltaic farms are in desert areas far from city areas and contribute highly to transportation coats or severely limits delivery to the end user.

The cost figure of supplying electricity to households in larger metropoles were determined as 2.50 ZAR (0.13 USD) after all taxes have also been included [

22].

It makes sense to follow and end users’ approach to reduce the cost of delivery to the (1) end user (especially in large countries); (2), to use alternative sources of renewable energies as available.

The utilization of solar PV energy, thermal energy absorbed from the sun and thermal solar energy absorbed from the environment as advanced alternative technologies. Some cost figures in this regard converting thermal energy to electrical energy has been determined as low as 0.80 ZAR (0.04 USD). The cost of storing thermal energy has been determined by our research 0.30 ZAR (0.02 USD)

Very importantly, this will reduce the burden on the local government to supply enough energy to its country citizens, and simultaneously stimulate the informal private sector and even Small and Medium Enterprises (SMMEs) to provide such services.

The development of technology systems utilizing solar and thermal energies at universities and the private sector, forms an important part of any futuristic developing country’s economy.

3.5.2. Energy Managing at the End User Household

Managing electricity usage in households in any country can have an important impact on the electricity usage as a function of time. Countries are often piqued with huge usage over peak times such as early mornings and late evenings. By properly installing and computer controlled “energy manager” in any household or larger premises much more “even” usage of energy can be ensured.

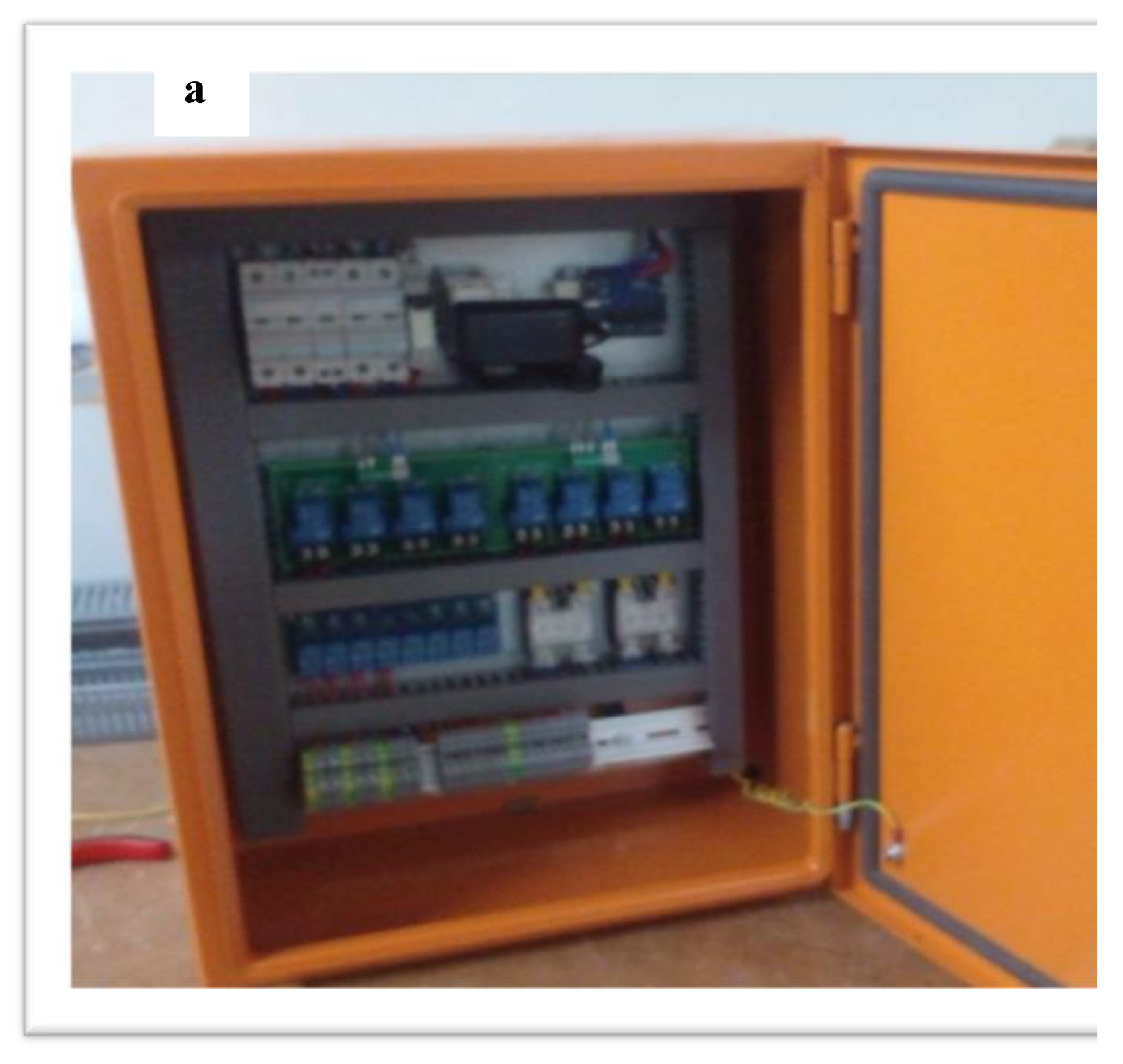

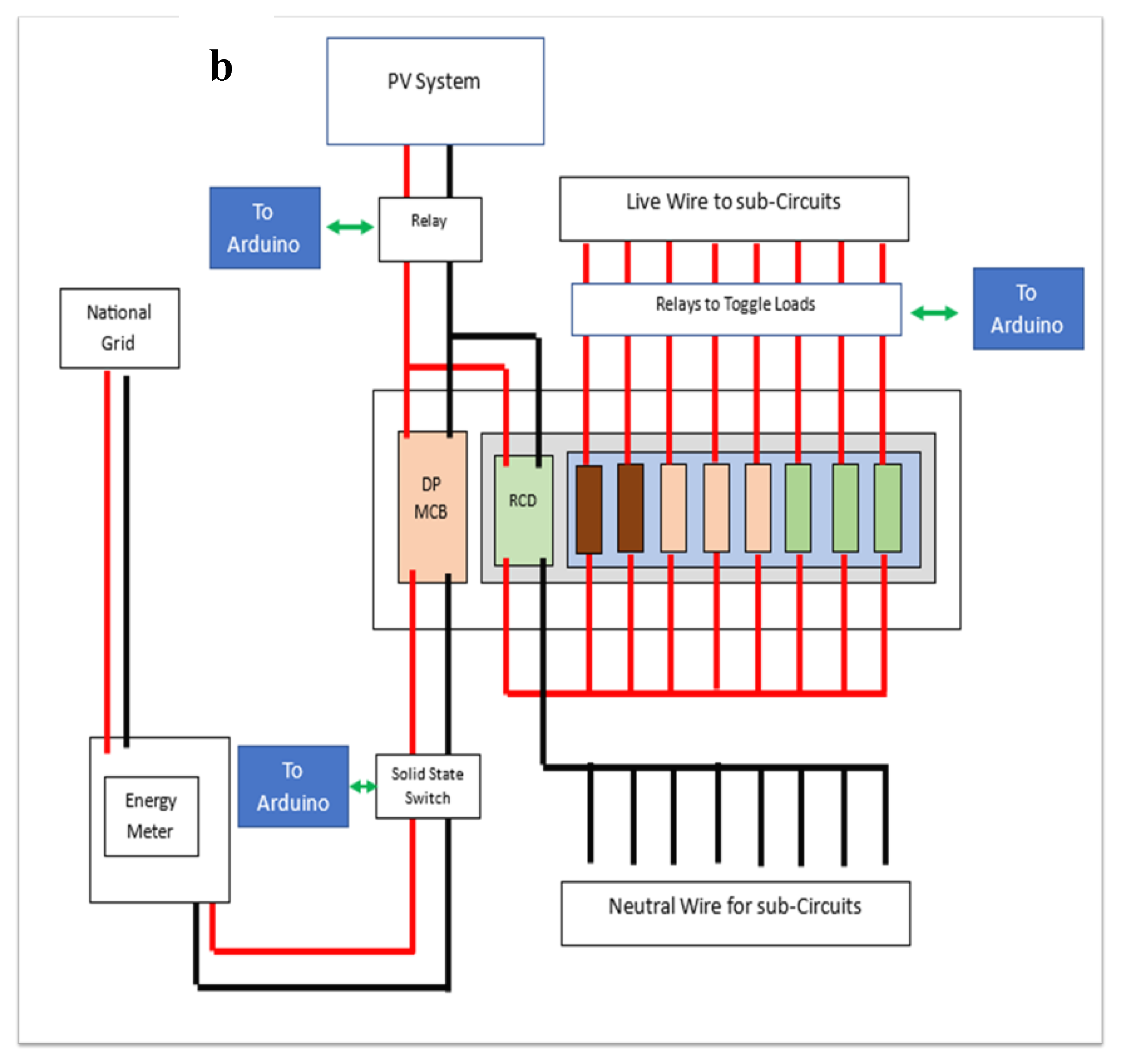

We have developed a dedicated energy manager that can be deployed in South Africa, and that can even out the usage of electricity during an average day. The energy manager comprises a computer-controlled box that is installed in a special box next to the distribution box in any household. The control box comprises of a small micro-computer, while the secondary control box entails several heavy load switches and solenoid switches coupled to the micro-computer. Basically, it switches off heavy loads such as swimming pools, refrigerators, and hot water geysers during peak demand periods, while maintaining lighter loads during peak demand periods.

This can have an important impact on energy usage optimization and on the monthly bill paid to electricity usage of a household, especially in countries with selective time rate tariffs.

Also, if a Radio Frequency (RF) system is coupled to this system, a third-party SMME, or local government itself, can control the energy usage of households, according to the principals as described.

Figure 8 below shows the prototype system that has been developed at our university More detail on the operation of the system is currently published elsewhere in this issue [

16]. It consists of the second control box and a micro-computer that can be housed separately, as is illustrated. The circuitry as implemented is shown in

Figure 8 (b).

The system involves several additional switches that are controlled by a microprocessor. Priority is given by the system to channel and use renewable energy into the household. Also, energy usage can be controlled that heavier loads are only coupled to the household outside peak periods. Also, a radio frequency system can be implemented that enable a third user the control the coupling of loads to the household.

This system, when employed in household on a protype basis, ensures proper total energy management of household appliances and can also reduce energy bills per month by up to 30 % in total. If dedicatedly employed, it can also give priority usage of solar and renewable energies, and only switch over to grid electricity usage when necessary.

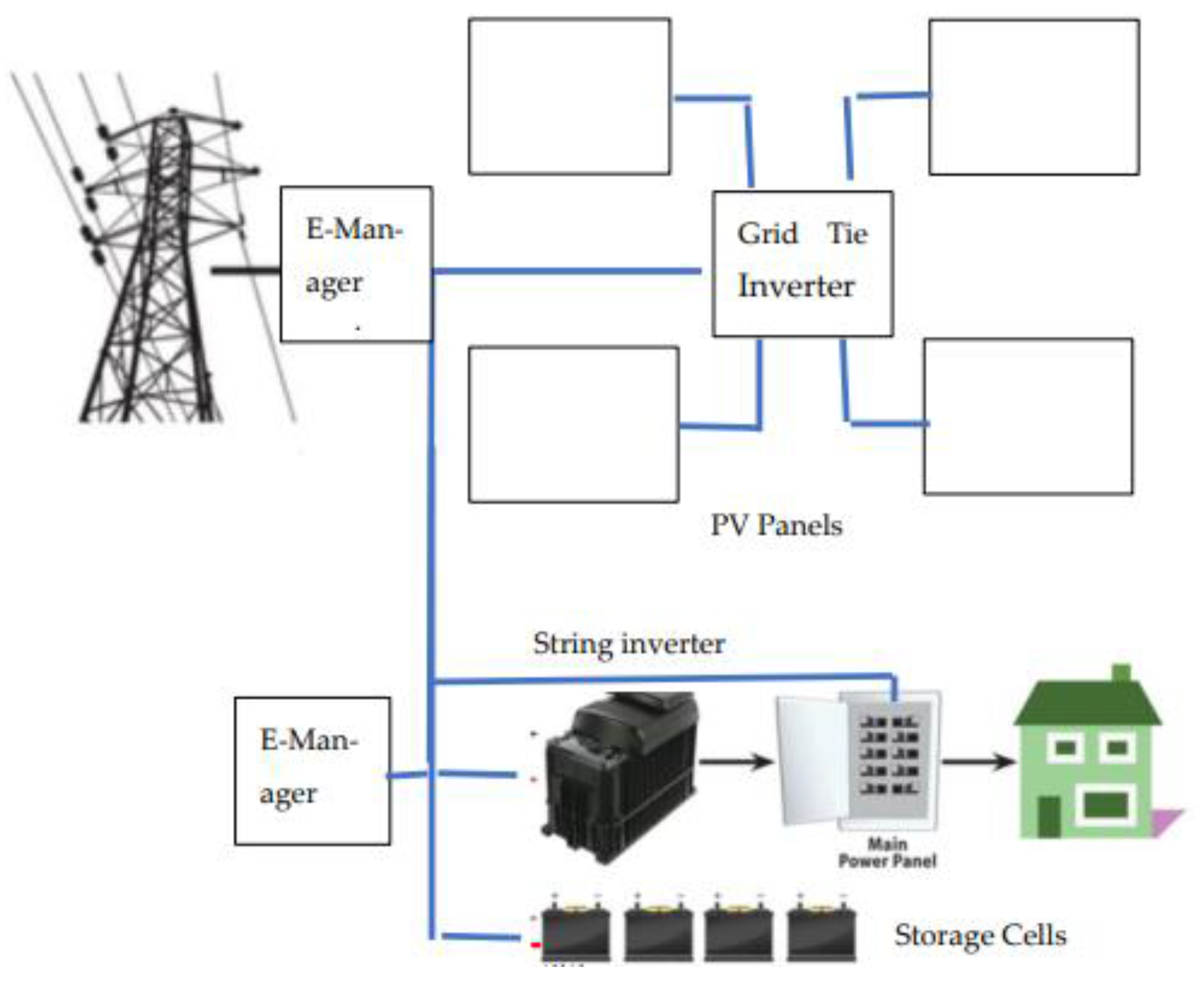

3.5.3. Grid-Tie versus String-Inverters

One gets two types of inverters that convert solar Direct Current (DC) to Alternating Current (AC), string inverters and grid tie inverters in a normal solar system PV supply system {26}.

String inverters as in

Figure 9, convert stored DC as accumulated from solar photo Voltaic (PV) panels to AC on a continuous basis, depending on the peak usage of the household over time. This normally results in excessively bulky, high-power systems and are quite expensive. The system is good for load-shedding applications since power is continuously converted from the battery system.

In Grid Tie inverters, the inverters are installed as close to the PV accumulating panels as possible and the power is converted to AC, as in

Figure 9. This reduces cable thickness of the energy transporting cables and reduces the total cost of the installation. Since many smaller inverters are used in requires synchronization and the grid AC system is normally used for this system. Another advantage of the system is that it supplies continuous power to the grid system and does not require bulky equipment and switchover systems, again reducing costs. According to circuit theory it will, however, supply the maximum of power to the closest loads, where loads have higher resistance than household lines, and about 80% of the energy is indeed supplied to the household.

We recommend using a grid tie conversion system combined with a smaller string inverter and with an electronic e-management system to supply lighter loads during load shedding as described above.

These aspects are all schematically illustrated in our designed system in

Figure 8 to reduce costs and increase overall efficiency.

3.5.4. Solar Thermal Energy Absorbing and Storing of Heat

South Africa has some of the highest solar resources in the world. The annual irradiation of about 6.2 kWh/m

2 per day is only beaten by Mexico in the United Staes of America. Also presented in more detail elsewhere [

8,

9].

A test carried out by the Council for Scientific and Research (CSIR) in South Africa (2016), showed that 40–60% of a household’s electricity. Using a solar energy geyser in a household would mean great electrical energy saving for South African households, in the order of 60% of the electricity bill. By developing these systems, we can also make substantial contributions towards reducing the traditional use of coal energy, oil, and gas resources in South Africa. This could also assist in greatly reduce the emission of greenhouse gases in the country.

A solar heat collector system was developed by the authors from low-cost materials by applying innovative design technology and using adaptive technologies, as is illustrated in

Figure 9. The system design entails placing long black Polyvinyl (PVC) pipes (low-cost technologies) , mounted, and positioned in grooves of inverted box rib galvanized steel plating. The grooves reflect and focus the incident rays on the center piping, concentrating incident sun rays on the black piping, and increase the absorption of thermal energy in the piping while circulating water. The piping is arranged in elevated arrays to maximize absorption per area. About 10 kWhr high heat energy to the next day, and to be used by a few household appliances, such as showering, bathing, clothes washing, dish washing and utility washings.

This system currently outperforms all other solar geyser systems in South Africa, normally operating on less effective thermal syphoning systems [

24,

25,

26,

27]. More detail of the system is provided elsewhere in this issue [

28].

Figure 10.

A grid tie inverter system combined with a locally developed E-Manager in order to reduce costs and increase efficiency of local supply systems in South Africa (By the authors, ).

Figure 10.

A grid tie inverter system combined with a locally developed E-Manager in order to reduce costs and increase efficiency of local supply systems in South Africa (By the authors, ).

The estimated cost of the system, considering the capital outlay over an expected ten-year life cycle for the product, was estimated at 0.30 SAR per kWh (0.02 $ per kWh). This pricing competes extremely favorably with the general cost of grid electricity in South Africa for medium-sized households, which is of the order of R2.50 per kWh. save the country of supplying grid electricity of the order of 370 MW per month, or elimination of about three loadshedding periods per day for that city area. If 10% of all households use the system in SA, it can amount to about 20 GWatts of power annum, leading to saving/ conservation of 30 % of the total grid energy usage in South Africa (about 60 G Watts per annum)

The hot water from the heat energy absorber system and small geyser storage if it is enough will able to help save electricity as the system it will help to heat up water, whereby the system will able to supply hot water to the a dish-washer, shower, basin, washing machine , and in that way it will help to save money that was paying the electricity bills in this regard, monthly.

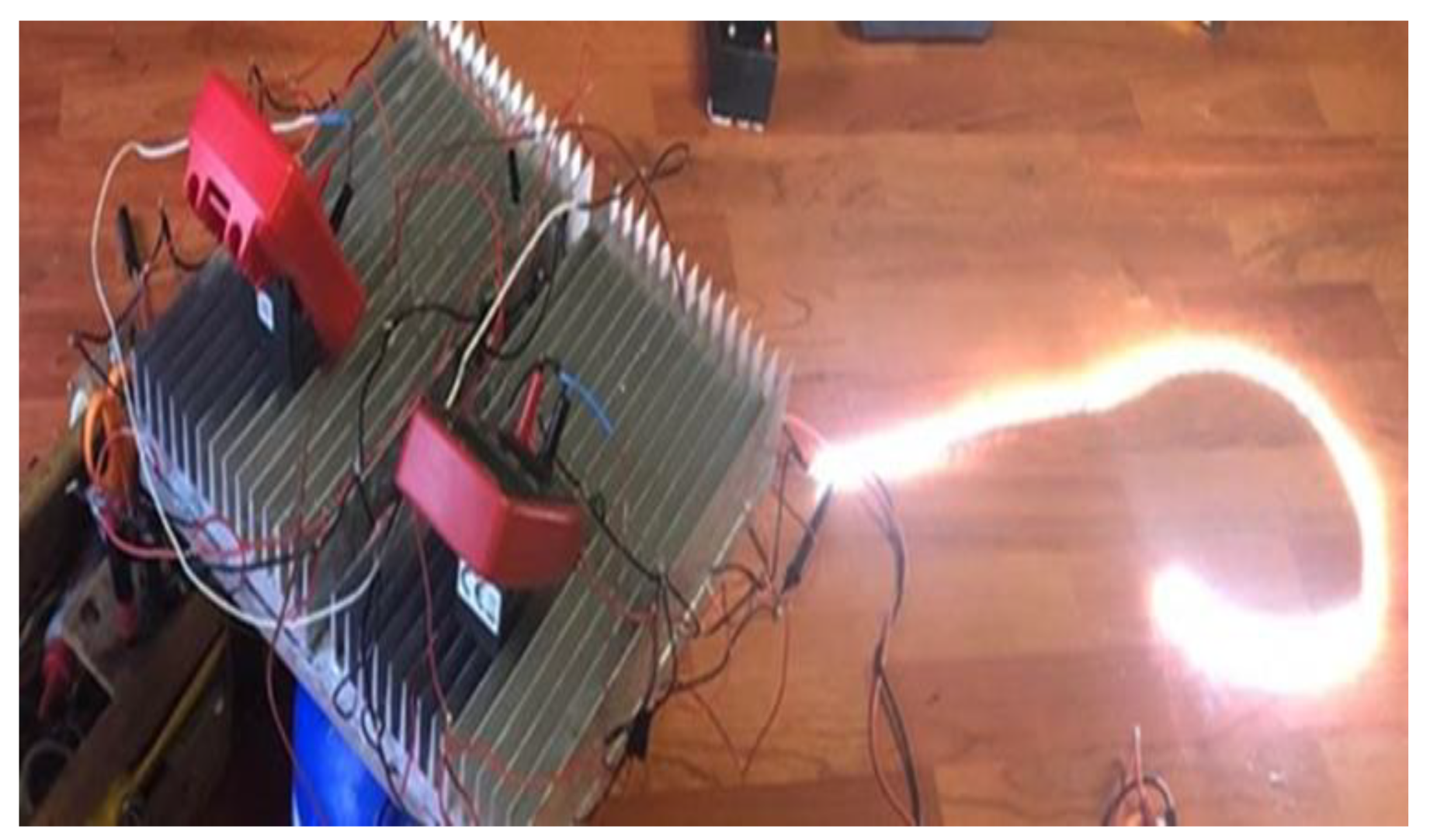

3.5.5. Conversion of Collected Thermal-Energy-to-Electricity

Low-cost Peltier conversion cells, that are normally used for cooling purposes, and that are freely available in supply stores in South Africa, were identified as suitable conversion cells for converting thermal energy into electricity [

32,

33]. Our group then designed thermal-to-electricity energy conversion systems. Particularly, advanced pulse mode DC- to- DC conversion technology, a special electronic control system, was developed, that could extract high amounts of electrical energy from the cells and could store the energy in standard storage batteries. A power conversion of up to 2 W capacity per individual cell was achieved (detail to be published elsewhere in this issue) [

34].

The systems used no movable parts, and the lifespan of the systems is projected to be at least twenty years. Viability analyses of the systems were performed, and the results were compared to existing solar photovoltaic energy conversion systems. The black body and reflector plate absorber system revealed a cost structure of only ZAR 0.80 per kWh (14.5 $ per kWh), as compared with a derived ZAR 3 per kWh (54 $ per kWh) for a combined photovoltaic and solar geyser combination, as calculated for a ten-year term. The technology as developed is suitable to be incorporated in South African households and rural Africa applications.

A Thermal-to-Electricity conversion efficiency of about 10% was achieved for one conversion cycle. This is however much more favorable than PV cells, since heat can be recycled many times, and using the following equation:

Where :

𝓃T is the total conversion efficiency

Qi is the initial thermal heat available,

Qc is the converted heat,

Qs is the subsequent cycled heat,

Ql is the total heat loss during recycling,

N is the number of cycles.

This leads to a total conversion efficiency of about 80 % if the total heat loss during recycling can be minimized.

Secondly, if heat was stored in a thermal reservoir, the heat to electricity conversion can occur on a 24-7 basis.

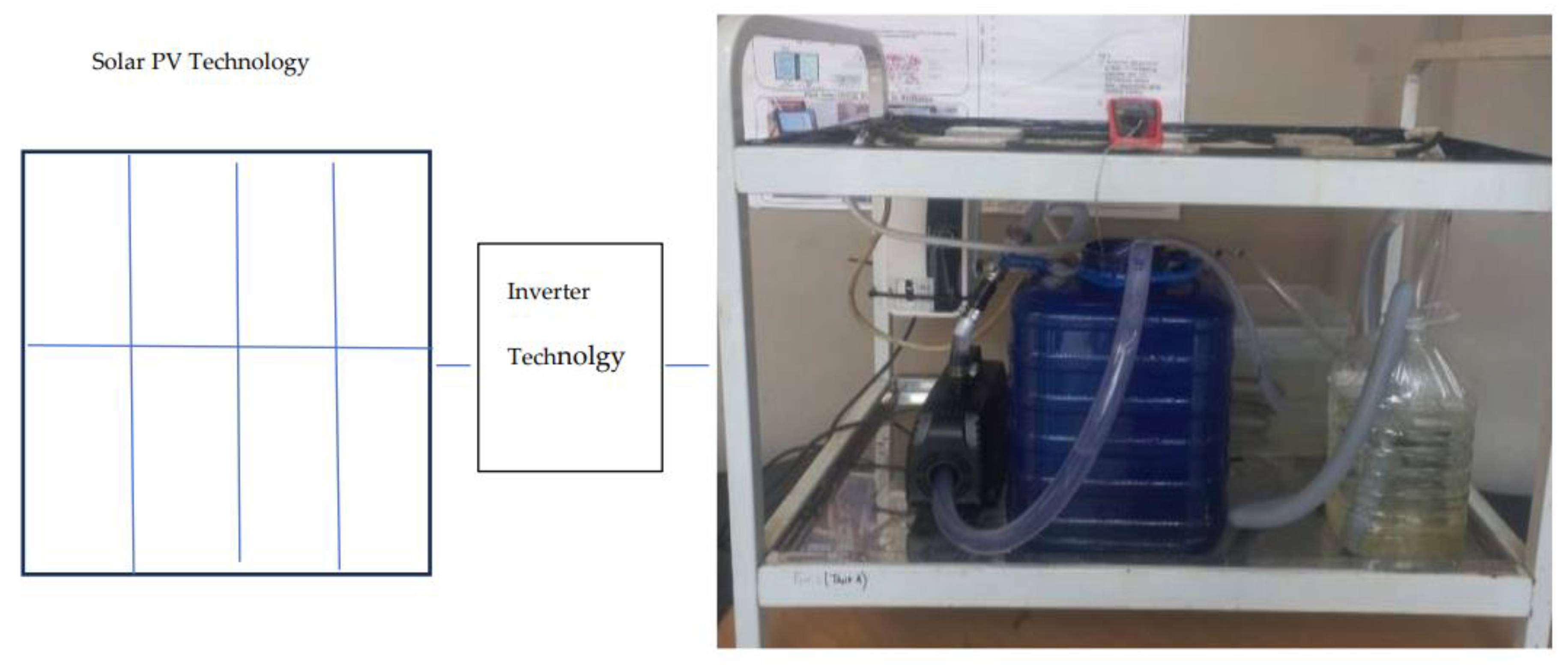

3.5.6. Utilization of Photo Voltaic (PV) Energy in Various Conversion Processes for Chemical Procedures

Nowadays, most conversion technologies and synthesizing technologies procedures involve complex chemical procedures, where some form of energy needs to be supplied [

35].

A typical example of this is in the water nexus technology where salty or mineral-containing water needs to be purified to pure drinkable water through a chemical membrane process and a selective distillation process (detail provided elsewhere in this issue [

36].

Solar energy PV systems remain currently and easy methodology to provide such energy. An example of such a system as recently implemented at CSET UNISA is shown in

Figure 12, where a simple system of PV panels and inverter technology is added to a system to supply the necessary electrical energy in order to facilitate the process.

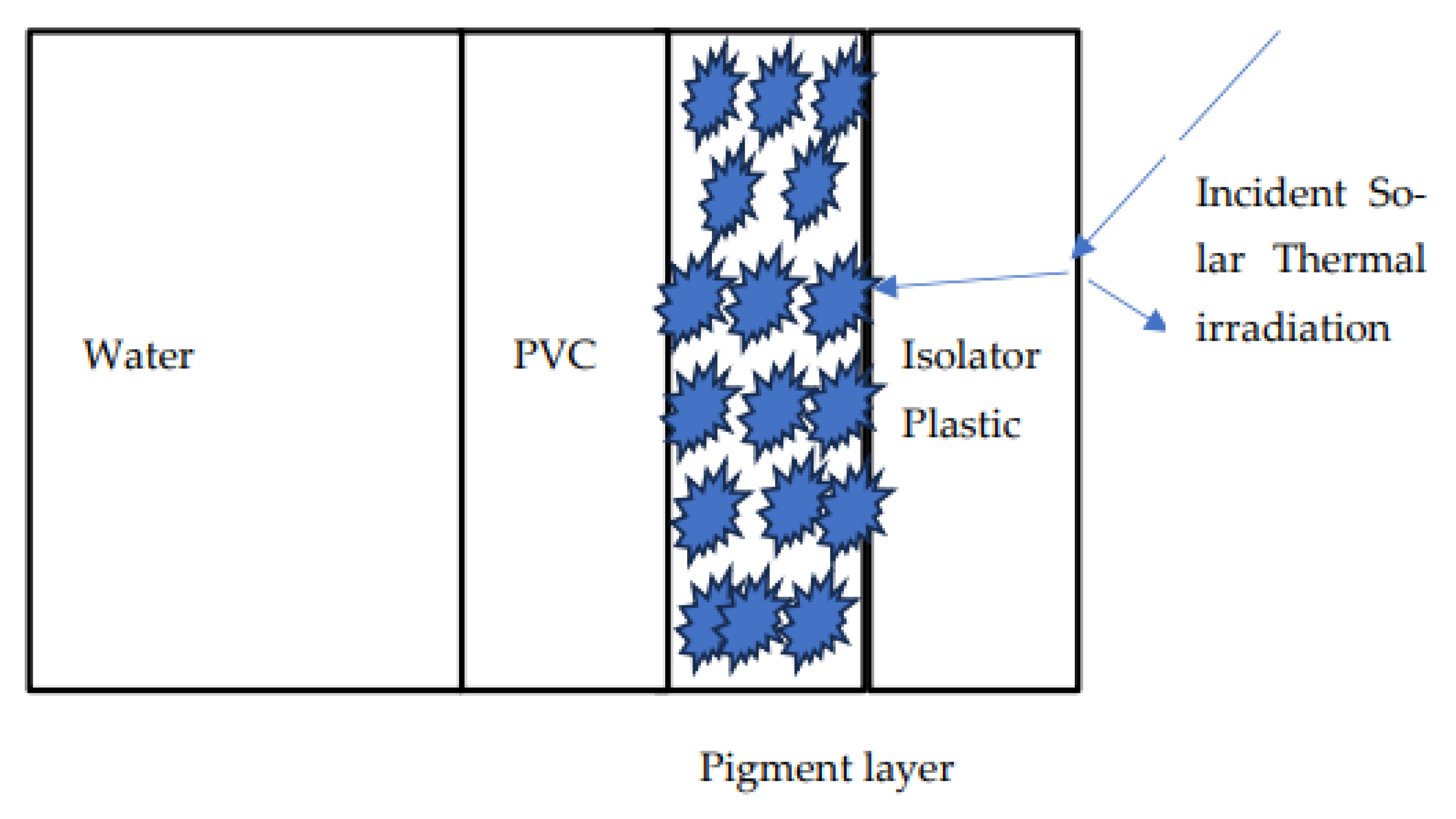

3.5.7. Effects of Nano-Technology (NT) on Macro-Material Characteristics

Nanotechnology can be used to effectively engineer and modify materials to change their optical characteristics. Such an example is given in

Figure 13, where middle layer contains black “pigments” and is used to change the optical characteristic of the material to “high absorption” while simultaneously choose the pigments material such that high thermal conduction also occurs. Simultaneously, the outer layer is chosen to consist of light material, and high transparency is obtained for the incident solar irradiation. This then also serves as efficient thermal insulation layer. Titanium dioxide particles that have a low cost and a high absorption for solar thermal energy is currently considered for this option.

Such a layer engineering is currently used in our low-cost solar thermal absorber construction as shown in

Figure 10. The detailed structure is shown in

Figure 13. It offers a very low-cost structure for the solar thermal absorber, while still offering adequate solar thermal absorption, as well as thermal isolation from the environment.

This example show how nanotechnology can effectively be used to engineer materials to have certain characteristics and sufficient efficiency at the macro level.

4. Conclusions

Several countries, including both developed countries such as the USA as well as developing countries such as South Africa, has amongst the best solar energy resources in the world. It enjoys some of the best sunshine in the world all year round, therefore the study focused on solar water heating systems.

A simple, efficient, and reliable solar water heating geyser has been developed from cheap and readily available materials in South Africa builders’ hardware shops.

The utilization of the prototype as developed can lead to extensive savings for South African households. It can result in substantial savings in monthly electricity bills for households at all income levels.

These systems can also make substantial contributions towards reducing the traditional use of coal energy, oil, and gas resources in South Africa. This could also assist to greatly reduce the emission of greenhouse gases in the country.

It is our derived opinion that the utilization of the prototype as developed in this study will lead to extensive savings in the use of traditional gas oil and coal energy resources in South Africa and result grossly the reduction of earth warming gases in South Africa and promote to the use of freely available energy from the sun.

Furthermore, it can result in savings of customer bills of thousands of rand in the whole spectrum from low income, medium income and even high-income households on energy bills each month.

5. Patents

The content of this article forms the subject of RSA Patents,

SA 2022/05297, SA 2009/0371, BR112017024456,

SA 2022/05297, 2018-521202, 16/330,696; SA 2017/07961; SA 2017/00444; SA 2018/03431; and International Patent Applications PCT/ZA2016/050021 , PCT/ZA2017/050052; PCT/ZA2017/050084. The intellectual property emanating from the study belongs to the University of South Africa and the Tshwane University of Technology [

36,

37].

Copyright protection is also valid on some of the logos used in the article.

Blueprints are available of all systems drawings and circuitry drawings from the authors of the article.

The intention is to make this technology available to the broader public and business sector of South Africa through appropriate licensing and local business creation actions, while a small portion of any profit generated will be channeled back to UNISA to promote further research and development actions.

Potential investors and collaborators are welcome to contact the Department of Technology Transfer and Commercialization office at UNISA.

Copyright protection is also valid on the logos used in the article.

Blueprints are available of all systems drawings and circuitry drawings from the authors of the article.

The intention is to make this technology available to the broader public and business sector of South Africa through appropriate licensing and local business creation actions, while a small portion of any profit generated will be channeled back to UNISA to promote further research and development actions.

Potential investors and collaborators are welcome to contact the Department of Technology Transfer and Commercialization office at UNISA.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, 1.; methodology, 1.; software, 2.; validation, 1,2..; formal analysis, 1.; investigation, 1,2.; resources, 1,2.; data curation,1,2.; writing—original draft preparation,1.; writing—review and editing, 1,2.; visualization, 1.; supervision, 1.; project administration, 1, 2.; funding acquisition, 1. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Rated Researcher Incentive Funding by the National Research Foundation Rated Researcher Incentive Grant IFR2011033100025,. They can be reached at

https://nrf.incentive /funding.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the Department of Electrical Engineering in the College of Science Engineering and Technology at the University of South Africa for their financial assistance and support in conducting the research, particularly through their Innovation Support Program of 2018 to 2022. Mr. Leloho Mohoje was a student of Electrical Engineering at the time of this study, and Professor Lukas Snyman from the UNISA College of Science and Engineering and technology was the main supervisor of the study. The study was quite challenging from a logistical and implementation point of view and required very labour intensive in implementation phases. Appreciation and acknowledgement are hence due to many friends and colleagues. Acknowledgement is given to the University of South Africa Technical staff, Mr Lehlo Mohoje, who provided research space, and technical support for conducting the study, as well as editing of the article. The assistance of fellow students and staff is also gratefully acknowledged.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- South Africa -Energy – International Trade Administration. As available at https://www.trade.gov. Assessed on 2 May 2024.

- Santander, D.; Whitley, S.; Kim, J.; Bae, D. Analysis of temperature distribution in PV-integrated electrochemical flow cells. 2023, 2, 045103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kou, X.; Wang, R.; Du, S.; Xu, Z.; Zhu, X. Heat pump assists in energy transition: Challenges and approaches. DeCarbon 2024, 3, 1000333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Wang, W.; Liu, Y.; Tian, H.; Shu, C. A numerical model for a thermally regenerative electrochemical cycled flow battery for low-temperature thermal energy harvesting. DeCarbon 2023, 1, 100007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mvili-Gampio, S.; Snyman, L.W. Developing a small photovoltaic power supply system with adaptive technol-ogies for rural Africa: Design, cost and efficiency analyses. Journal of Energy in Southern Africa 2018, 29, 60–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Twite, M.F., Snyman L.W., De Koker, J; Yusuff, D. “Development of a large-area, the low-cost solar water-heating system for South Africa with a high thermal energy collection capacity” Journal of Energy in Southern Africa 2019., 30 (1), 49-59, ISSN 1021-447X printed version, ISSN 2413-3051 online version. [CrossRef]

- Snyman, LW.,. “Low-pressure and high-pressure thermal collection system for South Africa households”, SA prior-ity patent application 2012/1508, 2012, filed at SA CIPRO. Tshwane University of technology.

- Sze , SM, Li,Y, Kwok, K, Ng , ,”Photodetectors and Solar Cells”, Physics of Semiconductor Devices , Second Edition, John Wiley, (19 81), 494.

- C. E Backus, ed. Solar Cells, IEEE Press , 1976.

- M. P Theksekara , on “Incident Solar Energy Suppl Proc 20th Ann Meeting , 1974 , Inst Environ. Science, Vol 3.

- Henry, C.H. Limiting efficiency of ideal single and multiple energy gap terrestrial. Solat Cells J. Appl. Physics 1988, 51, 4. [Google Scholar]

- D, L. Pulfrey “Photovoltaic Power Generation”, 1987, Van Nostrand Reinhold, New York.

- SOLARGIS. “Solar resource maps of South Africa”. As available at https://solargis.com/maps-and-gis-data/download/south-africa, (accessed on 10 July 2019).

- CJ Cleveland, CG Morris - 2013 - Handbook of energy: diagrams, charts, and tables, Elsevier, The Netherlands, 2013.

- “What are ElNino and La Nina”. Assessed on You Tube on 10 March 2024, You Tube. Also National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, https://oceanservice nosa.gov.

- Postdam Institute For Climate Impact Research, March 2024 , as assessed on www.pik-postdamde.

- Helderberg Solar Energy (2016) “How Does a Thermosiphon Solar Water Heater Work”. Available from: https://www.helderbergsolarenergy.com/blog/solargeysers/how-does-a-thermosiphon-solar-waterheater-work/ [accessed 31st July 2019].

- Four Seasons Heating, Air Conditioning and Plumbing , as assessed on March 2024 at www.fourseasonsheatingcooling.com.

- High Heat Capacity of Water. Including inorganic Material. Assessed at info@libretext.org , March 2024.

- Department of Energy (2018) 2018 SOUTH AFRICAN ENERGY SECTOR REPORT. Ratshomo, K (Comp.). [Online] Available from: http://www.energy.gov.za/files/media/explained/2018-South-AfricanEnergySector-Report.pdf [Accessed 23rd October 2019].

-

Eskom (2011) Annual Report 2011. [Online]. Available from: http://www.eskom.co.za/AboutElectricity/FactsFigures/Documents/OtherDocs/Th e_Solar_Water_Heating_SWH_Programme.pdf [Accessed 21st December 2017].

- Eskom (2023) Tarrif and Booklet , “Tariffs & Charges Booklet, 2022/2023”, p32,. Available at: 4756-ESKOM-Tariff-Booklet-2022-Final-Rev.pdf (accessed on 4 April 2023).

- Van Graan E and L.W Snyman. Submitted for publication. “An Electronic Manager for optimizing Electricity Flow into a SA household”: Energies Special Issue : Thermal Energy and Advanced Technologies, March 2024.

- Everything Solar (n.d.) Types of Solar Hot Water Systems. [Online]. Available from: https://poweredbydaylight.com/help/types-of-solar-hot-water-systems/ [Accessed 27th November 2017].

- Passion Technology (2017) High Absorption Flat Plate Solar Thermal Collector Aluminium Alloy Frame. Available from: https://www.thermalsolarwaterheater.com/sale-9831839-high-absorption-flatplatesolar-thermal-collector-aluminum-alloy-frame.html [Accessed 13th May 2019] [Accessed 4th August 2018].

- Everything Solar (n.d.) Types of Solar Hot Water Systems. [Online]. Available from: https://poweredbydaylight.com/help/types-of-solar-hot-water-systems/ [Accessed 27th November 2017].

- EMCO Industrial Plastics (2009) The Thermal Conductivity of Common Tubing Materials Applied in a Solar Water Heater Collector. Available from: http://ascpro0.ascweb.org/archives/cd/2010/paper/CPRT192002010.pdf [Accessed 10th October 2017].

- Qoliswe , Q and Snyman L.W,. Submitted for publication. “A low-cost solar Thermal Absorber for SA households“ Energies Special Issue : Thermal Energy and Advanced Technologies, March 2024.

- How a heat pump works.The future of Heat Pumps.. As assessed on 21 march 2024 at https //www..org/reports.

- Shop examples of Heat Pumps in South Africa”. As assessed on 21 March 2024 at google.com.

- Snyder, G. J. 2008. Thermoelectric Energy Harvesting. In Energy Harvesting Technologies, edited by S. Priya. Springer Nature Switzerland AG., pp 325-336 (Available at https://link.springer.com/book/10.1007/978-0-387-76464-1, accessed 5 December, 2021 ).

- Thermodynamic Electronics Jiangxi Corp. Ltd., Nanchang, China. 2017. Available at https://thermo-namic.en.alibaba.com/(accessed on 1 August 2017).

- Peu E and Snyman L.W. Submitted for publication. “A Thermal Energy to Electrical Energy Converter for SA households”: Energies Special Issue : Thermal Energy and Advanced Technologies, March 2024.

- Resource Recycling of Mn-Rich Sludge: Effective Separation of Impure Fe/Al and Recovery of High-Purity Hausmannite” Chenggui Liu, Qi Han, Yu Chen, Suiyi Zhu, Ting Su, Zhan Qu, Yidi Gao, Tong Li, Yang Huo,* and Mingxin Huo, ACS Omega 2021, 6, 7351−7359.

- Mohoje, L and Snyman, LW. Submitted for publication. “A Solar Powered System for the desalination of Ground water and Sea Water in South Africa”: Energies Special Issue : Thermal Energy and Advanced Technologies, March 2024.

- Snyman, LW. , “Integrated roof solar thermal energy collector”, RSA Patent Journal, Patent SA 2022/05297. 2022.The University of South Africa.

- Snyman, LW.,. “Smart controller for a household solar energy backup system”, RSA Patent 2022/567745, RSA Patent Journal, of May 2022.. Granted: SA (2009/3071), Tshwane University of technology. Snyman, LW., 2012. Low-pressure and high-pressure thermal collection system for South Africa.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).