1. Introduction

Anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) injuries are among the most common competitive athletic injuries resulting in musculoskeletal and neurophysiologic dysfunctions [

1,

2]. ACL reconstruction (ACLR) is considered the best treatment of choice after an ACL injury in athletes, with the aim to restore the stability, strength, and functional ability of the ACL-deficient knee, thus making a safe return to the pre-injury level of sports participation possible [

3]. Rehabilitation is considered as an integral component of the treatment process after ACLR, because it can dramatically affect the final outcome of the surgery [

4]. Post-operative rehabilitation may be conducted either at a specialized rehabilitation clinic, referred to as supervised rehabilitation (SVR), or in the patient's home, known as home-based rehabilitation (HBR). There is a debate in the literature regarding the most effective rehabilitation method after ACLR in competitive athletes [

5,

6]. A recent systematic review and meta-analysis comparing SVR and HBR after ACLR found no evidence supporting superior outcomes with SVR [

5]. A study by Feller et al. demonstrated that HBR with minimal supervision led to satisfactory results, but not better than SVR [

7]. Grant et al. found that HBR was more effective in terms of knee joint mobility only in the first three months after ACLR in contrast to SVR [

8]. Ugutmen et al., in their study, found that SVR participants received vocational training to learn to develop confidence in their state, adding additional benefits [

9]. Rhim H.C. and colleagues concluded that SVR gave additional benefits in terms of improved muscular strength, neuro-muscular control, and self-reported knee function score compared with HBR after ACLR [

10]. The effectiveness of SVR or HBR in terms of improved psychological outcomes in competitive athletes has not been reported in literature. Assessing psychological readiness for the safe return to sports (RTS) requires a comprehensive evaluation, considering both objective and subjective measures [

11].

The literature has reported high success rates of ACLR in competitive athletes [

12], but only less than half of them can resume their competitive sports participation and regain their pre-injury level of functional capabilities after ACLR [

13,

14]. RTS constitutes a crucial milestone in the rehabilitation process following ACLR in competitive athletes. However, there is currently a lack of evidence specifying the criteria for progression or discharge in this context [

15,

16]. Quadriceps and hamstrings strength deficits, abnormal hamstrings–quadriceps ratio (H-Q ratio), and the lack of motivation are the main risk factors related to re-injury [

17,

18,

19]. These risk factors can be addressed using outcome measures [

20]. These measures include Tegner-Activity-Scale (TAS), International Knee Documentation Committee subjective knee form (IKDC-SKF), and Anterior Cruciate Ligament Return to Sport after Injury Scale (ACL-RSI), whereas the neuromuscular strength and control measures include dynamic muscle strength, asymmetry ratio, weight distribution in stance evaluation and squat analysis.

Certain mental factors greatly influence the RTS after ACLR. These include the lack of intrinsic motivation and self-confidence, as well as the fear of re-injury, which may be associated with the competence, autonomy, and kinship of an athlete [

21]. The assessment of psychological factors related to the RTS can be assessed using a variety of methods, including the ACL-RSI scale; improvements in the scores of this scale are significantly associated with a safe RTS after ACLR [

22]. The ACL-RSI scale aids in identifying athletes who may experience challenges when resuming sport, thereby enabling healthcare professionals to provide personalized support during rehabilitation [

23].

The current study was designed to determine the effectiveness of SVR versus HBR on the prevention of re-injury after ACLR using same surgical technique among competitive athletes with the support of psychological evaluations. The objective was to assess the potential of SVR over HBR in terms of biomechanical and psychological outcome measures in competitive athletes after ACLR. Our hypothesis was that the SVR may lead to better outcomes in competitive athletes after ACLR as compared to HBR.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design

This pilot study was conducted at Castle Park Surgical Hospital (Tata, Hungary) and TSO Biomechanics Lab (Budapest, Hungary), between January 2020 and February 2023. It was ethically approved by Regional and Institutional Science and Research Ethic Committee of Semmelweis University, Budapest, Hungary (SE RKEB number: 120/2021). Prior written informed consent was taken from all the patients.

2.2. Patient Enrollment

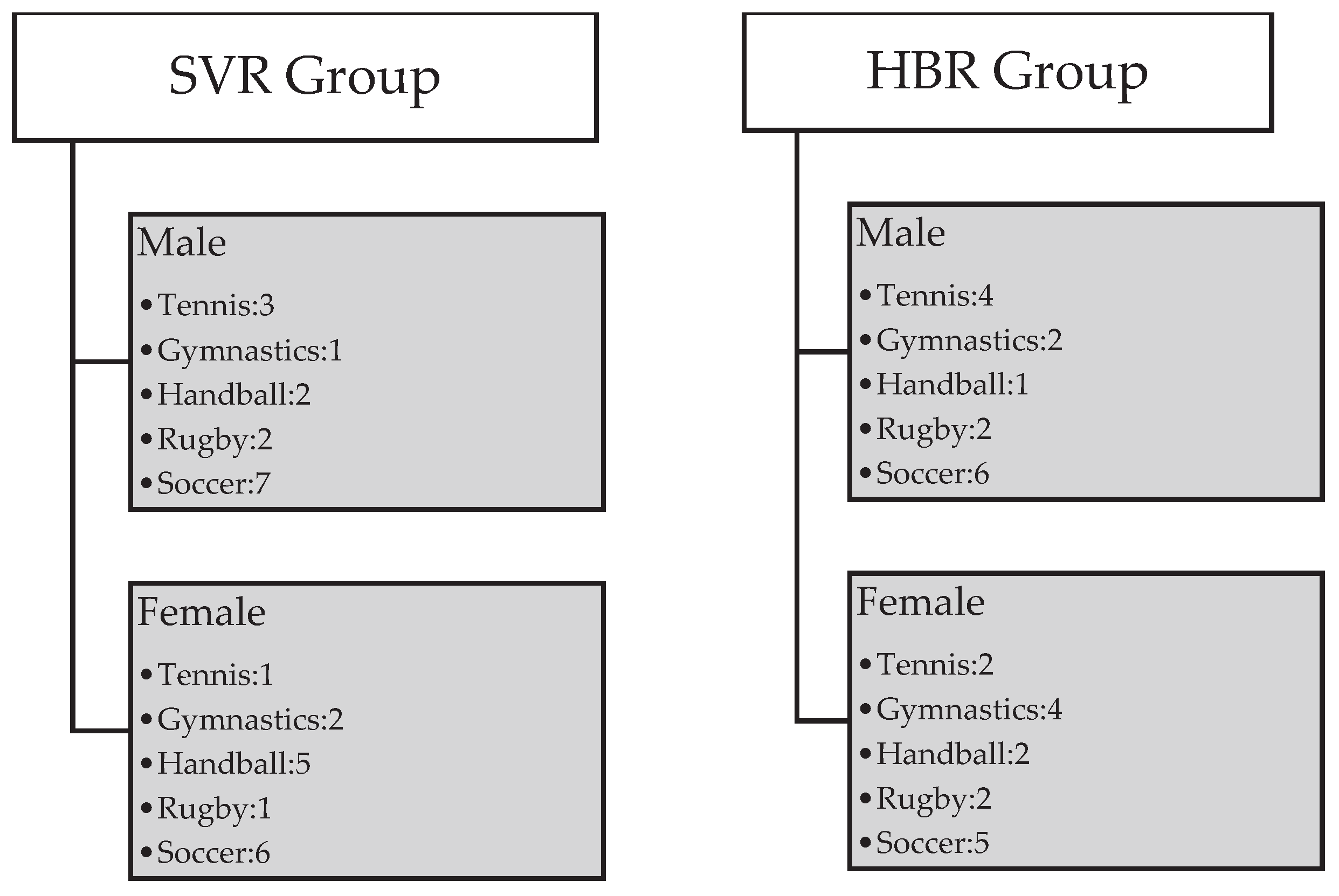

The patient enrollment process in our study was guided by a meticulous sample predetermination strategy, emphasizing transparency and precision in participant inclusion. Competitive athletes involved in high-risk pivoting sports, specifically soccer, rugby, handball, gymnastics, and tennis, and diagnosed with non-acute isolated ACL injuries, underwent surgical reconstruction. All surgeries were performed by a single operating surgeon at Castle Park Surgical Hospital in Tata, Hungary, between January 2020 and March 2021. Selection criteria, aligned with the American College of Cardiology [

24], included competitive athletes of both genders, aged 15 to 50 years, with diagnosed non-acute isolated ACL injuries and no secondary underlying pathology, having undergone ACLR. Exclusion criteria comprised non-competitive athletes, individuals below 15 or above 50 years of age, and those with multiple ligamentous or bony injuries and secondary underlying pathologies. To provide a comprehensive understanding of the athletic activities undertaken by participants, we presented a detailed gender-differentiated breakdown of type of sports as shown in

Figure 1. Following ACLR, 74 patients underwent screening based on inclusion criteria, with 14 excluded or dropping out. Ultimately, 60 participants were recruited and divided into two equal groups using non-probability convenience sampling: 30 SVR and 30 HBR (each group comprising 15 males and 15 females). SVR group was considered as case while HBR group was considered to be a control group.

2.3. Surgical Technique

ACLR was performed with the arthroscopic transtibial technique using quadruple-bundle hamstrings (semitendinosus and gracilis) autografts with endobutton fixation on the femoral side and Milagro® advance interference absorbable screw (DePuy Synthes, an orthopedics company of Johnson & Johnson, USA) fixation on the tibial side.

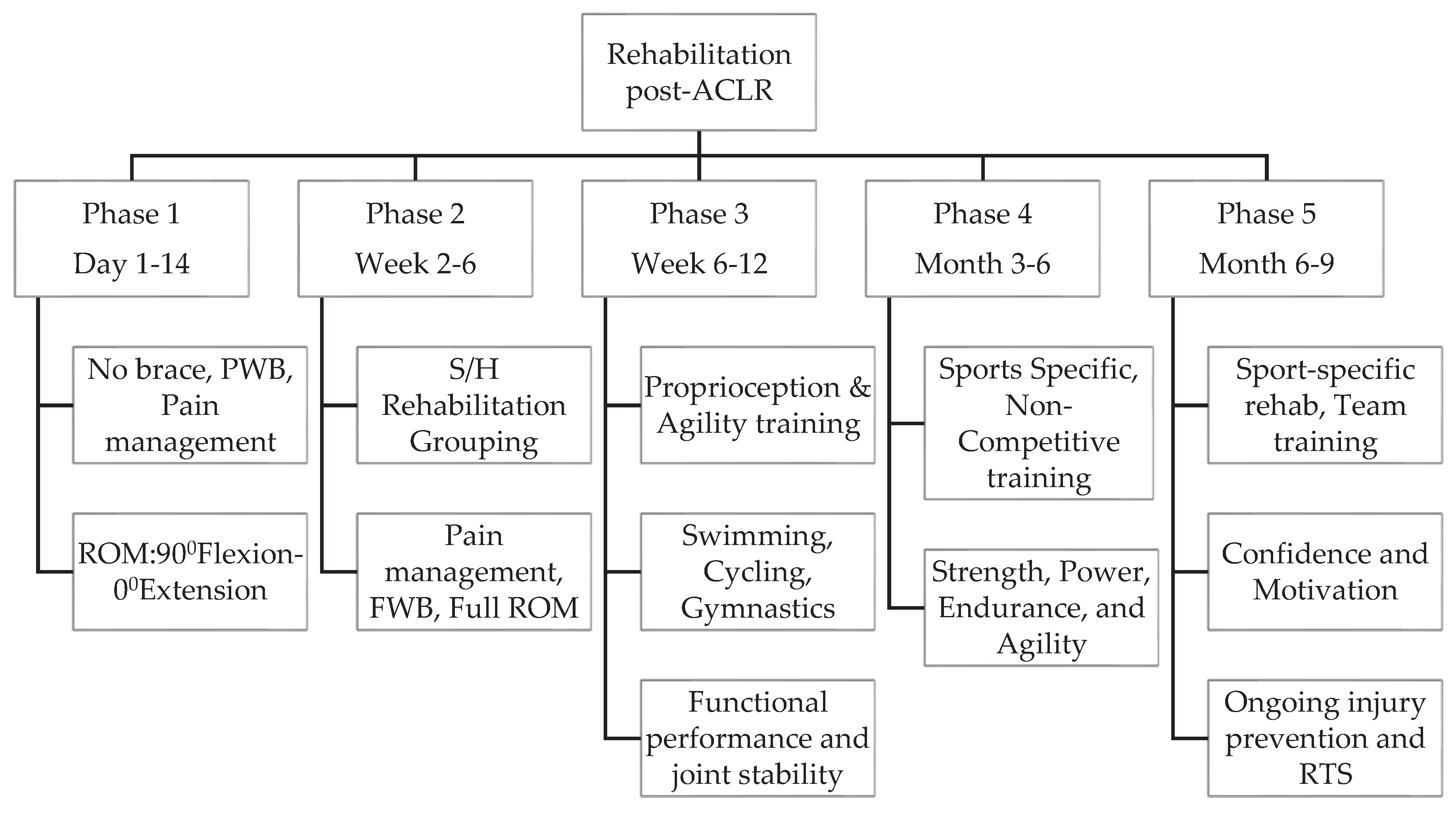

2.4. Rehabilitation Protocols

Following ACLR, a structured rehabilitation program was implemented to optimize the recovery process and facilitate the safe RTS. The rehabilitation protocol consisted of five distinct phases; with focus on pain management, mobility and range of motion (ROM) improvement in the initial phases, while improvements in the strength, power, endurance, stability, and extensibility of the associated knee structures were the focus of later phases [

23] as shown in

Figure 2.

The number of patient’s visits to the physiotherapist ranged from 40-64 for SVR group and 5-12 for HBR group. SVR participants were required to attend supervised physical therapy classes twice a week as an outpatient program in a rehabilitation clinic, with each session lasting 90-120 minutes. The exercises and the format of the class were based predominantly on proprioceptive and functional trainings, although some updated exercises were also included [

25].

Patients in the HBR group performed all remedial exercises unsupervised at home. The recommended training protocols were provided in written form with pictorial representations of the exercises to be performed at home. During the intervention period, participants in the HBR group engaged in a minimum of two exercise sessions per week. Adherence to the treatment plan was monitored through periodic assessments at the rehabilitation clinic, where adjustments, education, and modifications were made as necessary. Patient adherence was reinforced through regular communication channels, including follow-up appointments and remote consultations. The frequency of follow-up appointments and the progression of exercises were tailored to the individual's response and left to the discretion of the treating therapist.

Five mandatory follow-up examinations were performed in both rehabilitation groups; including the removal of stitches at postoperative day 14, followed by division into SVR and HBR groups. Phase 1 was identical for both groups. At the 6-week mark, a second examination assessed activity level progression. Phase 2-5 was carried out with same exercise programs either supervised or home-based. A third review at 3 months evaluated patients' ability to perform complex physical activities actively, while a fourth review at 6 months assessed progress towards achieving physical attributes necessary for RTS. The protocol related to intensity and frequency of training was kept the same for all the patients, with the only difference of supervision [

26].

At the 8-month mark, a fifth follow-up examination was conducted, subjecting all participants to subjective and objective evaluations at the Biomechanics Lab. Based on these evaluations, patients were permitted to gradually participate in their respective competitive sports only if they met certain criteria, which were mainly designed by their treating therapist, following scientific literature guidelines [

27,

28]. The mean time period to RTS since ACLR in both rehabilitation groups was approximately 9 months, and re-injury rates were measured and recorded at the 5-6-month mark following RTS. The rehabilitation protocol was based on "Campbell's Operative Orthopedics" textbook [

29].

2.5. Outcome measures

The TAS score was used to assess the participants according to their level of sports activity, using a numeric scale of 0 to 10, where 0 represented knee-related disability and 10 represented the highest level of competitive sport.

The IKDC-SKF was utilized to subjectively evaluate knee functional scores using a self-reported scale ranging from 0 (lowest knee function) to 100 (highest knee function). This patient-completed tool contains sections on knee symptoms (7 items), function (2 items), and sports activities (2 items), with scores ranging from 0 points (lowest level of function or highest level of symptoms) to 100 points (highest level of function and lowest level of symptoms).

The psychological readiness to RTS was evaluated using the ACL-RSI questionnaire, via which the athlete’s subjective responses were recorded using 12 structurally designed questions. ACL-RSI questionnaire, developed by Webster, Feller, and Lambros (2008) [

23], comprises a total of 12 questions regarding emotional wellbeing (5 questions), the level of confidence in performing the respective sport (5 questions), and risk appraisal (2 questions). The percentage of the total score indicates the psychological response of a patient.

2.6. Assessment of Muscle Strength and Neuromuscular Control

The isometric maximum strength of the quadriceps and hamstrings muscles was measured in kilograms using Kinvent Isometric Dynamometers (KINVENT, France; K-Pull and K-Push Handheld Dynamometers) at knee flexion angles of 30°, 45°, and 90°. The percentage of strength deficits in the muscles of the operated side was compared to the non-operated side at each specific angle. For all three measured joint angles quadriceps and hamstrings ratio was calculated (H/Q ratio).

Static and dynamic balance (standing and unilateral squatting) tests were performed on the KINVENT Force Plates and the average COP (Center of Pressure) position was measured. The differences of average foot pressures (%) were calculated between the sides during both measurements.

The maximum isometric strength of the hip adductors and abductors was measured on the Vald Performance’s Force frame at a knee joint angle of 60 degrees. Results were calculated in Newton and the force deficit between sides and the agonist-antagonist ratio were also calculated.

Re-injury was detected through clinical and MRI examinations performed by the operating doctor. RTS was recorded according to the athlete’s reported sports participation.

2.7. Statistical Analysis

Data is represented by averages and standard deviations. To define the adequate statistical procedure Shapiro Wilk’s W test was performed to identify normality. For the comparison of the datasets paired sample t-test or Wilcoxon test and independent sample t-test or Mann-Whitney U test was performed. For the discrete value comparisons Chi-Square test was calculated. JASP and Statistica (TIBCO Statsoft USA) statistical software were used for the calculations. The significance level was set at p<0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Baseline Characteristics

In this study, a total of 60 participants were included, with a deliberate and equal allocation of 15 male and 15 female individuals in each of the SVR and HBR groups. This gender-balanced distribution was methodologically chosen to enhance the robustness of our analysis, aiming to mitigate potential gender-related biases. This decision was not driven by the specific frequency of ACL injuries but rather by the strategic objective of ensuring a representative cohort for comprehensive assessment. The mean age in the SVR group was 22.43 ± 6.34 years, while in the HBR group, it was 24.96 ± 7.93 years. However, the difference in age between the two groups was not statistically significant (p = 0.1991). Likewise, there were no significant differences in height and weight between the groups, with mean values of 174.78 ± 9.59 cm and 172 ± 9.81 cm for height and 71.11 ± 12.90 kg and 77.23 ± 20.41 kg for weight in the SVR and HBR groups respectively (p = 0.3022 for height, p = 0.1960 for weight). Lastly, the mean follow-up time was 8.62 ± 7.32 months for the SVR group and 8.48 ± 7.68 months for the HBR group, with no significant difference between the two groups (p = 0.9501). These results indicate that, at baseline, both rehabilitation groups were comparable in terms of gender distribution, age, height, weight, and follow-up time.

Table 1 displays the demographic data for the participants in the study.

The t-test for BMI was calculated separately for men and women. No significant difference in BMI was found among male and female athletes in their respective rehabilitation groups, indicating that the groups were comparable (

Table 2).

3.2. Patient Reported Questionnaires

The TAS score for male participants in the SVR group changed from 8 (pre-op) to 7 (post-op), while in the HBR group, the score changed from 7 (pre-op) to 5 (post-op). Similarly, for female participants, the SVR group showed a change from 7 (pre-op) to 6 (post-op), whereas the HBR group displayed a change from 8 (pre-op) to 6 (post-op). The average TAS score in the SVR group was 8 pre-operatively and 7 post-operatively, while in the HBR group, it was 8 pre-operatively and 6 post-operatively. These results suggest that both rehabilitation approaches led to a reduction in the TAS scores post-operatively. However, the average post-operative score was slightly lower in the HBR group compared to the SVR group.

Prior to surgery, the mean pre-operative IKDC-SKF score in the SVR group was 49, compared to 45 in the HBR group. Results demonstrated a significant difference in postoperative IKDC-SKF scores between SVR and HBR groups. The mean post-operative IKDC-SKF score in the SVR group was 81.82, compared to 68.43 in the HBR group (p=0.0021). It is worth mentioning that the IKDC-SKF scores improved for both groups in the post-operative values.

Conversely, the mean post-operative ACL-RSI score in the HBR group was 55.25±9.72, while it was 49.46±8.14 in the SVR group (p=0.0194). These findings indicate that individuals in the SVR group achieved higher IKDC-SKF scores, suggesting better post-operative outcomes. However, individuals in the HBR group had higher ACL-RSI scores, indicating a greater psychological readiness to RTS compared to the SVR group. Unfortunately, the pre-operative data for ACL-RSI scores was not available.

3.3. Comparison of Muscle Strength and Neuromuscular Control Parameters

At 30 degrees the percentage of isometric strength deficit in the quadriceps between the operated and non-operated limb was 26.1% in the SVR group and 27.9% in the HBR group. Similarly, the percentage of isometric strength deficit in the hamstrings was 14.1% in the SVR group and 32.2% in the HBR group. The percentage of H/Q asymmetry at 30 degrees was 10.9% in the SVR group and 1.1% in the HBR group, and that was not significant for either comparison (

Table 3).

At 45 degrees the percentage of isometric strength deficit in the quadriceps between the operated and non-operated limb was 22.3% in the SVR group and 22.1% in the HBR group. Similarly, the percentage of isometric strength deficit in the hamstrings was 12.8% in the SVR group and 47.8% in the HBR group. The percentage of H/Q asymmetry at 45 degrees was not significant in the SVR group (0.8%) but was significant in the HBR group (16.6%, p<0.05).

At 90 degrees the percentage of isometric strength deficit in the quadriceps between the operated and non-operated limb was 23.1% in the SVR group and 23.9% in the HBR group. The percentage of isometric strength deficit in the hamstrings was 69.7% in the SVR group and 84.9% in the HBR group. The percentage of H/Q asymmetry at 90 degrees was significant in both the SVR group (37.9%) and the HBR group (30.5%, p<0.05).

No significant differences were observed in the percentages of weight distribution deficit in stance evaluation, squat analysis and hip abductor and adductor force and asymmetry measurements. These findings suggest that both rehabilitation approaches led to similar outcomes in terms of these variables, as shown in the following

Table 4.

3.4. Return to Sport

In the SVR group, 76.6% of individuals were able to return to the same level of sport participation following ACL rehabilitation. Additionally, 16.6% were able to return to a lower level of sport participation, while 6.6% did not return to any sport activities. In contrast, the HBR group had a lower percentage of individuals returning to the same level of sport participation, with only 53.3% achieving this outcome. Furthermore, 30% of individuals in this group were able to return to a lower level of sport participation, while 16.6% did not return to any sport activities. The observed disparities in sport participation levels between the two groups are substantiated by the data presented in

Table 5, where a Chi-Square test contingency table indicated a significant difference (p=0.036).

3.5. ACL Re-injury

The comprehensive evaluation of ACL re-injury rates necessitates a subtle understanding of the distinction between re-injury to the previously operated knee and new injuries, particularly those affecting the contralateral knee. In both the SVR and HBR groups, the overall re-injury rate was 3.3%. However, it is crucial to delineate the contralateral ACL injury rate, which was 6.6% in the SVR group and 3.3% in the HBR group.

4. Discussion

A recent systematic review concluded that the previous studies fail to demonstrate a significant difference between SVR and HBR [

5]. This lack of differentiation stems primarily from inadequate assessment of psychological and biomechanical outcomes, particularly among elite athletes. Our study compared the outcomes of SVR versus HBR in competitive athletes after ACLR, considering both biomechanical and psychological outcomes. The comparison of our findings with the literature elucidates key insights. Our deliberate gender-balanced allocation aimed to enhance the study's robustness and minimize gender-related biases. While not directly aligned with literature, this methodology aligns with the overarching goal of creating a representative cohort for comprehensive assessment [

12]. The comparable baseline characteristics, including age, height, weight, and follow-up time, corroborate with previous studies emphasizing the importance of homogeneous cohorts for accurate evaluation [

12,

13,

14]. Our study's observed reduction in TAS scores post-operatively for both rehabilitation groups concurs with literature, indicating a commonality in the impact of rehabilitation on activity levels [

12,

13]. The slightly lower average post-operative TAS score in the HBR group aligns with findings suggesting variations in activity scale outcomes based on rehabilitation methods [

6].

Our results align with literature indicating a significant improvement in IKDC-SKF scores post-operatively for both rehabilitation groups [

12]. Notably, SVR yielded superior post-operative outcomes. Conversely, HBR participants exhibited greater psychological readiness for RTS. This concurs with literature emphasizing psychological factors for RTS [

21,

22,

23]. Rehabilitation can be successfully complemented by consultation with a sports psychologist and the use of methods that influence mental factors, such as active goal setting and relaxation techniques [

30]. Psychic responses generally improve during rehabilitation, but in some cases, fear may increase and become a serious risk factor when returning to sport [

31]. RTS is not just significantly influenced by normal postoperative knee function [

32]. Prior physical activity history, enhanced psychological readiness, and interventions may benefit individuals with lower optimism levels [

33].

Muscle strength imbalances are of particular concern in individuals after ACLR. Significant differences in the dynamometric values favoring the SVR group in muscle strength and symmetry values highlight its greater efficiency in rehabilitation, consistent with literature indicating potential benefits of supervised programs [

6]. Further research is warranted to explore the underlying mechanisms contributing to the observed H/Q asymmetry at different degrees of knee flexion and to optimize rehabilitation strategies for improving muscle balance across a wider range of motion.

The significant divergence of RTS percentages between the rehabilitation groups echoes literature emphasizing the impact of rehabilitation methods on RTS [

13,

14]. Our study showed an overall re-injury rate of 3.3%, consistent with literature emphasizing the importance of considering different types of injuries [

16]. The observed contralateral ACL injury rates indicate that, while the overall re-injury rate is consistent between the two groups, the distribution of injuries differs. This insight provides a more refined perspective on the nature of injuries and enhances the interpretation of rehabilitation outcomes in the context of contralateral ACL lesions. Monitoring re-injury rates 5-6 months after resuming sports activities provided valuable insights into the effectiveness of rehabilitation protocols in preventing further injuries. These thoughtfully chosen time points aimed to capture critical recovery milestones and evaluate the associated risks and outcomes involved in resuming sporting activities. Successful ACL restoration involves unrestricted sports participation and a return to pre-injury levels. Considering the influence of fear of re-injury is crucial in assessing ACLR outcomes [

34]. SVR may provide athletes with more challenging training, especially in the later phases of rehabilitation, in such a way that they can develop their sport-specific skills and expertise more confidently and comfortably [

35].

The selected time periods in this study were strategically determined to assess key aspects of post-operative recovery. The evaluation at eight months’ post-operation provided a comprehensive assessment of muscle strength and knee function, reflecting a substantial recovery period. At nine months’ post-operation, the focus shifted to evaluating the capacity to return to sport. Optimizing recovery after ACL reconstruction requires comprehensive rehabilitation plans that prioritize the restoration of muscular strength and functional status in both the reconstructed knee and the unaffected limb, as emphasized in the literature [

36]. Literature indicated that criterion-based rehabilitation after ACLR is essential to enable effective recovery and allow athletes to achieve their RTS goals while extenuating impairments related to re-injury [

37,

38]. In addition to the fulfillment of these objective criteria, a rehabilitation program should also focus on improving the subjective knee functional and psychological readiness scores [

39]. A prerequisite for a safe and early RTS is to take into account the latest evidence concerning re-injury prevention and to establish ongoing professional communication among the injured athlete, the coach, the physician, and the physiotherapist [

40]. To achieve the best recovery outcomes for competitive athletes, it is imperative to prioritize the psychological readiness of athletes in the supervised group.

5. Limitations

Following data collection, the prospect of conducting a 2x2 ANOVA for male and female groups within SVR and HBR samples was considered to identify gender-based differences in the phenomenon. However, this approach was dismissed due to the resultant reduction in sample sizes, thereby significantly diminishing the statistical power of calculations. Consequently, the original samples were retained, maintaining an equal gender distribution (50-50%) in both SVR and HBR groups. Given the absence of significant differences in anthropometric values between the samples, we believe that the initial objectives of the manuscript can be adequately addressed with this sample size. Nonetheless, the lack of gender-specific analysis represents a limitation of this study. Thus, we acknowledge this research as a pilot study, laying the groundwork for future investigations, particularly focusing on competitive athletes, where larger sample sizes will be utilized with separate analyses for male and female groups.

Another aspect of the study that may be considered as a limitation is the absence of a universally acknowledged isokinetic dynamometer, such as the Biodex or HumacNorm, for biomechanical measurements. However, it is imperative to underscore that the primary objective of data collection was to compare various samples rather than to establish comparisons with universally recognized datasets. Consequently, considering the accuracy of the employed devices, we determined that the use of simpler equipment sufficed for achieving the study's objectives.

6. Conclusion

Both rehabilitation approaches demonstrated comparable outcomes among competitive athletes post-ACLR. However, SVR provided additional advantages by enhancing biomechanical outcomes, leading to a comparable rate of return to same level sport. Nevertheless, there was no disparity in the re-injury rate, potentially due to a lack of notable improvements in psychological outcomes compared to HBR group, especially after an average of 8 months following ACLR. Therefore, to achieve successful RTS and prevent re-injury in competitive athletes, it is crucial to implement criterion-based rehabilitation programs. These programs should include continuous psychological preparation supervised by a physiotherapist. Future research should consider utilizing large sample sizes and long-term follow-up to thoroughly assess the effectiveness of rehabilitation in terms of preventing re-injury after ACLR.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.I.B.S. and B.I.; methodology, B.I.; software, B.K.; validation, R.I.B.S.; formal analysis, R.I.B.S. and B.K.; investigation, R.I.B.S.; data curation, G.F. and P.K.; writing—original draft preparation, R.I.B.S.; writing—review and editing, B.I. and R.I.B.S.; visualization, L.R.H.; supervision, B.I. and L.R.H.; project administration, R.I.B.S. and B.I. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by Semmelweis University Regional and Institutional Committee of Science and Research Ethics, Hungary (SE RKEB number: 120/2021). Approval date was 23 June 2021.

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in the study are available upon request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors owe special thanks to TSO Medical Hungary for their assistance with the biomechanical evaluations.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Griffin, L.Y.; Agel, J.; Albohm, M.J.; Arendt, E.A.; Dick, R.W.; Garrett, W.E.; Garrick, J.G.; Hewett, T.E.; Huston, L.; Ireland, M.L.; et al. Noncontact anterior cruciate ligament injuries: Risk factors and prevention strategies. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 2000, 8, 141–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.H.; Lee, D.H.; Park, J.H.; Suh, D.W.; Kim, E.; Jang, K.M. Poorer dynamic postural stability in patients with anterior cruciate ligament rupture combined with lateral meniscus tear than in those with medial meniscus tear. Knee Surg Relat Res 2020, 32, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.H.; Han, S.B.; Park, J.H.; Choi, J.H.; Suh, D.K.; Jang, K.M. Impaired neuromuscular control up to postoperative 1 year in operated and nonoperated knees after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Medicine 2019, 98, e15124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wright, R.W.; Haas, A.K.; Anderson, J.; Calabrese, G.; Cavanaugh, J.; Hewett, T.E.; Lorring, D.; McKenzie, C.; Preston, E.; Williams, G.; et al. Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction Rehabilitation: MOON Guidelines. Sports Health 2015, 7, 239–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uchino, S.; Saito, H.; Okura, K.; Kitagawa, T.; Sato, S. Effectiveness of a supervised rehabilitation compared with a home-based rehabilitation following anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Phys Ther Sport. 2022, 55, 296–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hohmann, E.; Tetsworth, K.; Bryant, A. Physiotherapy-guided versus home-based, unsupervised rehabilitation in isolated anterior cruciate injuries following surgical reconstruction. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2011, 19, 1158–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feller, J.A.; Webster, K.E.; Taylor, N.F.; Payne, R.; Pizzari, T. Effect of physiotherapy attendance on outcome after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: A pilot study. Br J Sports Med 2004, 38, 74–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grant, J.A.; Mohtadi, N.G.; Maitland, M.E.; Zernicke, R.F. Comparison of home versus physical therapy- supervised rehabilitationprograms after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: A randomized clinical trial. Am J Sports Med 2005, 33, 1288–1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ugutmen, E.; Ozkan, K.; Kilincoglu, V.; Ozkan, F.U.; Toker, S.; Eceviz, E.; Altintas, F. Anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction by using otogenous [correction of otogeneous] hamstring tendons with home-based rehabilitation. J Int Med Res. 2008, 36, 253–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhim, H.C.; Lee, J.H.; Lee, S.J.; Jeon, J.S.; Kim, G.; Lee, K.Y.; Jang, K.M. Supervised Rehabilitation May Lead to Better Outcome than Home-Based Rehabilitation Up to 1 Year after Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction. Medicina 2020, 57, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glattke, K.E.; Tummala, S.V.; Chhabra, A. Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction Recovery and Rehabilitation: A Systematic Review. The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery 2022, 104, 739–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forster, M.C.; Forster, I.W. Patellar tendon or four-strand hamstring? A systematic review of autografts for anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Knee 2005, 12, 225–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ardern, C.L.; Webster, K.E.; Taylor, N.F.; Feller, J.A. Return to sport following anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction surgery: A systematic review and meta-analysis of the state of play. Br J Sports Med 2011, 45, 596–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ebert, J.R.; Edwards, P.; Yi, L.; Joss, B.; Ackland, T.; Carey-Smith, R.; Buelow, J.U.; Hewitt, B. Strength and functional symmetry is associated with post-operative rehabilitation in patients following anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2018, 26, 2353–2361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kotsifaki, R.; Korakakis, V.; King, E.; et al. Aspetar clinical practice guideline on rehabilitation after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Br J Sports Med. 2023, 57, 500–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grindem, H.; Snyder-Mackler, L.; Moksnes, H.; Engebretsen, L.; Risberg, M.A. Simple decision rules can reduce reinjury risk by 84% after ACL reconstruction: The Delaware-Oslo ACL cohort study. Br J Sports Med. 2016, 50, 804–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hewett, T.E.; Di Stasi, S.L.; Myer, G.D. Current concepts for injury prevention in athletes after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Am J Sports Med 2013, 41, 216–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wiggins, A.J.; Grandhi, R.K.; Schneider, D.K.; Stanfield, D.; Webster, K.E.; Myer, G.D. Risk of Secondary Injury in Younger Athletes After Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction: A Systematic Review and Meta- analysis. Am J Sports Med. 2016, 44, 1861–1876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papalia, R.; Vasta, S.; Tecame, A.; D'Adamio, S.; Maffulli, N.; Denaro, V. Home-based vs supervised rehabilitation programs following knee surgery: A systematic review. Br Med Bull 2013, 108, 55–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyritsis, P.; Bahr, R.; Landreau, P.; Miladi, R.; Witvrouw, E. Likelihood of ACL graft rupture: Not meeting six clinical discharge criteria before return to sport is associated with a four times greater risk of rupture. Br J Sports Med 2016, 50, 946–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardern, C.L.; Österberg, A.; Tagesson, S.; Gauffin, H.; Webster, K.E.; Kvist, J. The impact of psychological readiness to return to sport and recreational activities after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Br J Sports Med. 2014, 48, 1613–1619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadeqi, M.; Klouche, S.; Bohu, Y.; Herman, S.; Lefevre, N.; Gerometta, A. Progression of the Psychological ACL- RSI Score and Return to Sport After Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction: A Prospective 2-Year Follow-up Study From the French Prospective Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction Cohort Study (FAST). Orthopaedic Journal of Sports Medicine. 2018, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Webster, K.E.; Feller, J.A.; Lambros, C. Development and preliminary validation of a scale to measure the psychological impact of returning to sport following anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction surgery. Phys Ther Sport. 2008, 9, 9–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maron, B.J.; Zipes, D.P.; Kovacs, R.J. Eligibility and Disqualification Recommendations for Competitive Athletes with Cardiovascular Abnormalities: Preamble, Principles, and General Considerations: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association and American College of Cardiology. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015, 66, 2343–2349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Filbay, S.R.; Grindem, H. Evidence-based recommendations for the management of anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) rupture. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 2019, 33, 33–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costa, S.N.; Boiko Ferreira, L.H.; Barauce Bento, P.C. The effects of supervision on three different exercises modalities (supervised vs. home vs. supervised+home) in older adults: Randomized controlled trial protocol. PLoS ONE. 2021, 16, e0259827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Müller, U.; Krüger-Franke, M.; Schmidt, M.; Rosemeyer, B. Predictive parameters for return to pre-injury level of sport 6 months following anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction surgery. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2015, 23, 3623–3631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joreitz, R.; Lynch, A.; Popchak, A.; Irrgang, J. Criterion-based rehabilitation program with return to sport testing following acl reconstruction: A case series. Int J Sports Phys Ther. 2020, 15, 1151–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canale, S.T.; Beaty, J.H. Campbell’s Operative Orthopaedics E-Book; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Podlog, L.; Dimmock, J.; Miller, J. A review of return to sport concerns following injury rehabilitation: Practitioner strategies for enhancing recovery outcomes. Phys Ther Sport. 2011, 12, 36–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardern, C.L.; Taylor, N.F.; Feller, J.A.; Whitehead, T.S.; Webster, K.E. Psychological responses matter in returning to preinjury level of sport after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction surgery. Am J Sports Med. 2013, 41, 1549–1558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardern, C.L.; Webster, K.E.; Taylor, N.F.; Feller, J.A. Return to the preinjury level of competitive sport after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction surgery: Two-thirds of patients have not returned by 12 months after surgery. Am J Sports Med. 2011, 39, 538–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Webster, K.E.; Nagelli, C.V.; Hewett, T.E.; Feller, J.A. Factors Associated With Psychological Readiness to Return to Sport After Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction Surgery. Am J Sports Med. 2018, 46, 1545–1550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kvist, J.; Ek, A.; Sporrstedt, K.; Good, L. Fear of re-injury: A hindrance for returning to sports after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2005, 13, 393–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, F.; Banerjee, A.; Shen, L.; Krishna, L. Increased Compliance With Supervised Rehabilitation Improves Functional Outcome and Return to Sport After Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction in Recreational Athletes. Orthop J Sports Med. 2015, 3, 2325967115620770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chung, K.S.; Ha, J.K.; Yeom, C.H.; et al. Are Muscle Strength and Function of the Uninjured Lower Limb Weakened After Anterior Cruciate Ligament Injury? Two-Year Follow-up After Reconstruction. Am J Sports Med. 2015, 43, 3013–3021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sugimoto, D.; Myer, G.D.; McKeon, J.M.; Hewett, T.E. Evaluation of the effectiveness of neuromuscular training to reduce anterior cruciate ligament injury in female athletes: A critical review of relative risk reduction and numbers-needed-to-treat analyses. Br J Sports Med. 2012, 46, 979–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, D.; Logerstedt, D.S.; Hunter-Giordano, A.; Axe, M.J.; Snyder-Mackler, L. Current concepts for anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: A criterion-based rehabilitation progression. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2012, 42, 601–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faleide, A.G.H.; Magnussen, L.H.; Strand, T.; Bogen, B.E.; Moe-Nilssen, R.; Mo, I.F.; Vervaat, W.; Inderhaug, E. The Role of Psychological Readiness in Return to Sport Assessment After Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction. Am J Sports Med. 2021, 49, 1236–1243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Melick, N.; van Cingel, R.E.; Brooijmans, F.; Neeter, C.; van Tienen, T.; Hullegie, W.; Nijhuis-van der Sanden, M.W. Evidence-based clinical practice update: Practice guidelines for anterior cruciate ligament rehabilitation based on a systematic review and multidisciplinary consensus. Br J Sports Med. 2016, 50, 1506–1515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).