Submitted:

25 July 2025

Posted:

29 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Current Evidence and Future Directions in ACL Surgery and Rehabilitation

From Past to Present

Therapy of ACL Injuries: Development of Arthroscopic Surgery

Rehabilitation of ACL Injuries: Development of Treatment Protocols

Early-Stage Rehabilitation

Duration of the Rehabilitation Process

Prehabilitation

Open vs. Closed Kinetic Chain Exercises

Innovative Training Tools

Conservative Management

Return-to-Play Process

Bracing

Summary of the Current State

Fom Present to Future

Prevention of ACL Injury

Therapy of ACL Injuries: Development in ACL Surgery

Technical Innovations

Development of ACL Repair

Rehabilitation of ACL Injuries

Markerless Motion Capture

Digital Health Application

The Use of AI in Rehabilitation

- Injury and Treatment Outcome Prediction

- Diagnostic

- Rehabilitation

- Limitations and ethical concerns

Injury and Treatment Outcome Prediction

Diagnostic

Rehabilitation

Limitations and Ethical Concerns

3. Materials and Methods

4. Results

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ACL | Anterior Cruciate Ligament |

| ACL-R | Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction |

| AGT | Anti-Gravity Training |

| BFR | Blood Flow Restriction |

| BPTB | Bone-patellar tendon-bone graft |

| DL | Deep Learning |

| HS | Hamstring graft |

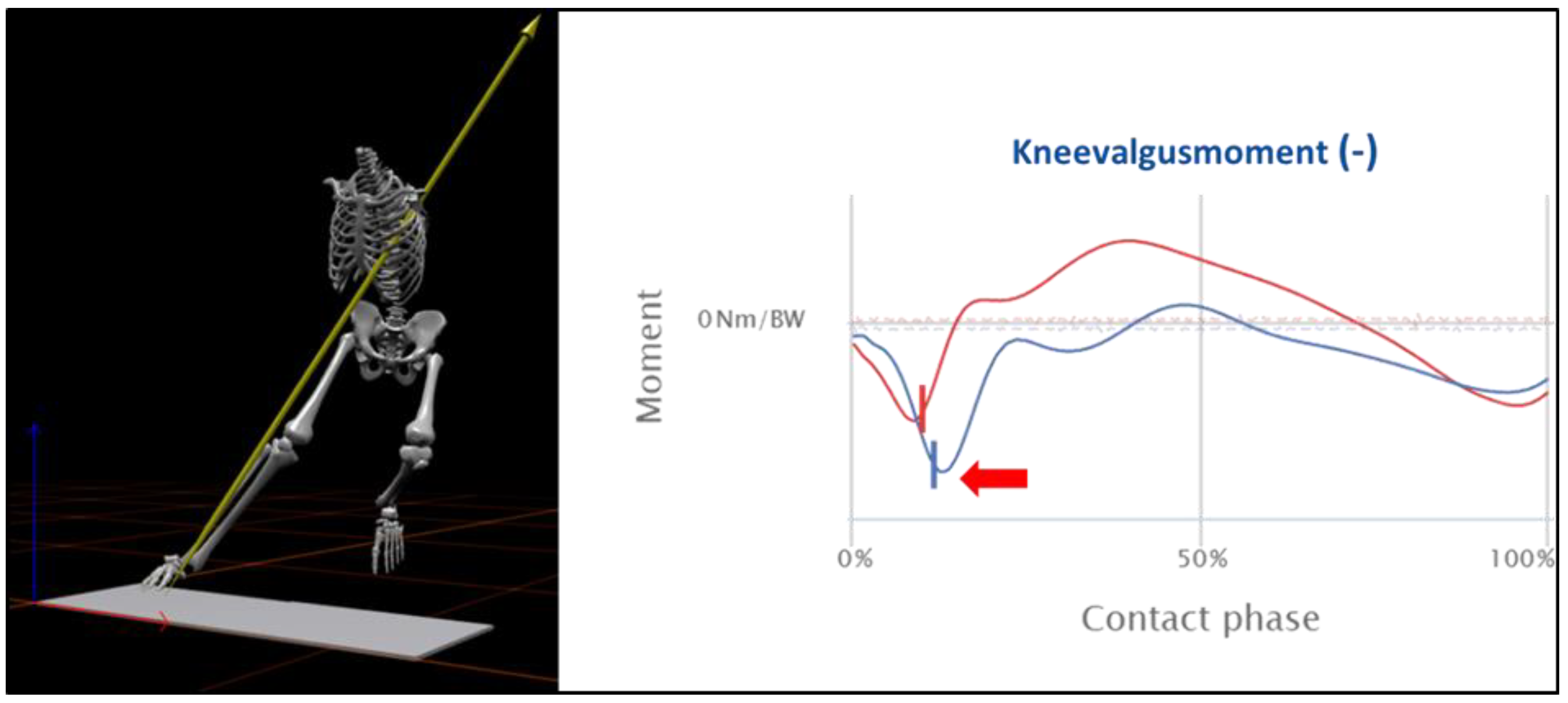

| KVM | Knee Valgus Moment |

| ML | Machine Learning |

| MMC | Marker-less Motion Capture |

| RFS | Recovery from Surgery |

| RTA | Return-to-Activity |

| RTR | Return-to-Running |

| RTS | Return-to-Sports |

| RTP | Return-to-Play |

| RTC | Return-to-Competition |

| ROM | Range of motion |

| RTS | Return-to-sports |

| STC | Supra-threshold cluster |

| SPM | Statistical Parametric Mapping |

| SVM | Support Vector Machine |

References

- van Melick, N.; van Cingel, R.E.; Brooijmans, F.; Neeter, C.; van Tienen, T.; Hullegie, W.; Nijhuis-van der Sanden, M.W. Evidence-based clinical practice update: practice guidelines for anterior cruciate ligament rehabilitation based on a systematic review and multidisciplinary consensus. Br J Sports Med 2016, 50, 1506–1515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, B.; Garrett, W.E. Mechanisms of non-contact ACL injuries. British journal of sports medicine 2007, 41, i47–i51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bram, J.T.; Magee, L.C.; Mehta, N.N.; Patel, N.M.; Ganley, T.J. Anterior cruciate ligament injury incidence in adolescent athletes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. The American journal of sports medicine 2021, 49, 1962–1972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamath, G.V.; Murphy, T.; Creighton, R.A.; Viradia, N.; Taft, T.N.; Spang, J.T. Anterior cruciate ligament injury, return to play, and reinjury in the elite collegiate athlete: analysis of an NCAA Division I cohort. The American journal of sports medicine 2014, 42, 1638–1643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardern, C. Fifty-five per cent return to competitive sport fo. 2014.

- Ardern, C.L.; Webster, K.E.; Taylor, N.F.; Feller, J.A. Return to sport following anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis of the state of play. British journal of sports medicine 2011, 45, 596–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, V.M.; Andrews, J.R.; Fleisig, G.S.; McMichael, C.S.; Lemak, L.J. Return to play after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction in National Football League athletes. The American journal of sports medicine 2010, 38, 2233–2239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boszotta, H. Arthroscopic anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction using a patellar tendon graft in press-fit technique: surgical technique and follow-up. Arthroscopy 1997, 13, 332–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brandsson, S.; Faxén, E.; Eriksson, B.I.; Swärd, L.; Lundin, O.; Karlsson, J. Reconstruction of the anterior cruciate ligament: comparison of outside-in and all-inside techniques. Br J Sports Med 1999, 33, 42–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cameron, S.E.; Wilson, W.; St Pierre, P. A prospective, randomized comparison of open vs arthroscopically assisted ACL reconstruction. Orthopedics 1995, 18, 249–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deehan, D.J.; Salmon, L.J.; Webb, V.J.; Davies, A.; Pinczewski, L.A. Endoscopic reconstruction of the anterior cruciate ligament with an ipsilateral patellar tendon autograft. A prospective longitudinal five-year study. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2000, 82, 984–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, F.H.; Bennett, C.H.; Ma, C.B.; Menetrey, J.; Lattermann, C. Current trends in anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Part II. Operative procedures and clinical correlations. Am J Sports Med 2000, 28, 124–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jomha, N.M.; Pinczewski, L.A.; Clingeleffer, A.; Otto, D.D. Arthroscopic reconstruction of the anterior cruciate ligament with patellar-tendon autograft and interference screw fixation. The results at seven years. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1999, 81, 775–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shelbourne, K.D.; Urch, S.E. Primary anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction using the contralateral autogenous patellar tendon. Am J Sports Med 2000, 28, 651–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, F.H.; Schulte, K.R. Anterior cruciate ligament surgery 1996. State of the art? Clin Orthop Relat Res 1996, 19–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muneta, T.; Sekiya, I.; Yagishita, K.; Ogiuchi, T.; Yamamoto, H.; Shinomiya, K. Two-bundle reconstruction of the anterior cruciate ligament using semitendinosus tendon with endobuttons: operative technique and preliminary results. Arthroscopy 1999, 15, 618–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Neill, D.B. Arthroscopically assisted reconstruction of the anterior cruciate ligament. A prospective randomized analysis of three techniques. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1996, 78, 803–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinczewski, L.A.; Clingeleffer, A.J.; Otto, D.D.; Bonar, S.F.; Corry, I.S. Integration of hamstring tendon graft with bone in reconstruction of the anterior cruciate ligament. Arthroscopy 1997, 13, 641–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenberg, T.D.; Deffner, K.T. ACL reconstruction: semitendinosus tendon is the graft of choice. Orthopedics 1997, 20, 396–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, K.; Maffulli, N. The ligament augmentation device: an historical perspective. Arthroscopy 1999, 15, 422–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abate, J.A.; Fadale, P.D.; Hulstyn, M.J.; Walsh, W.R. Initial fixation strength of polylactic acid interference screws in anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Arthroscopy 1998, 14, 278–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brand, J., Jr.; Weiler, A.; Caborn, D.N.; Brown, C.H., Jr.; Johnson, D.L. Graft fixation in cruciate ligament reconstruction. Am J Sports Med 2000, 28, 761–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, R.; Olsen, R.E.; Larson, B.J.; Goble, E.M.; Farrer, R.P. Cross-pin femoral fixation: a new technique for hamstring anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction of the knee. Arthroscopy 1998, 14, 258–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meredick, R.B.; Vance, K.J.; Appleby, D.; Lubowitz, J.H. Outcome of single-bundle versus double-bundle reconstruction of the anterior cruciate ligament: a meta-analysis. Am J Sports Med 2008, 36, 1414–1421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buoncristiani, A.M.; Tjoumakaris, F.P.; Starman, J.S.; Ferretti, M.; Fu, F.H. Anatomic double-bundle anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Arthroscopy 2006, 22, 1000–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, F.H.; Shen, W.; Starman, J.S.; Okeke, N.; Irrgang, J.J. Primary anatomic double-bundle anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a preliminary 2-year prospective study. Am J Sports Med 2008, 36, 1263–1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcacci, M.; Molgora, A.P.; Zaffagnini, S.; Vascellari, A.; Iacono, F.; Presti, M.L. Anatomic double-bundle anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction with hamstrings. Arthroscopy 2003, 19, 540–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aga, C.; Risberg, M.A.; Fagerland, M.W.; Johansen, S.; Trøan, I.; Heir, S.; Engebretsen, L. No Difference in the KOOS Quality of Life Subscore Between Anatomic Double-Bundle and Anatomic Single-Bundle Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction of the Knee: A Prospective Randomized Controlled Trial With 2 Years’ Follow-up. Am J Sports Med 2018, 46, 2341–2354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussein, M.; van Eck, C.F.; Cretnik, A.; Dinevski, D.; Fu, F.H. Prospective randomized clinical evaluation of conventional single-bundle, anatomic single-bundle, and anatomic double-bundle anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: 281 cases with 3- to 5-year follow-up. Am J Sports Med 2012, 40, 512–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Claes, S.; Vereecke, E.; Maes, M.; Victor, J.; Verdonk, P.; Bellemans, J. Anatomy of the anterolateral ligament of the knee. J Anat 2013, 223, 321–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claes, S.; Luyckx, T.; Vereecke, E.; Bellemans, J. The Segond fracture: a bony injury of the anterolateral ligament of the knee. Arthroscopy 2014, 30, 1475–1482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, M.I.; Claes, S.; Fuso, F.A.; Williams, B.T.; Goldsmith, M.T.; Turnbull, T.L.; Wijdicks, C.A.; LaPrade, R.F. The Anterolateral Ligament: An Anatomic, Radiographic, and Biomechanical Analysis. Am J Sports Med 2015, 43, 1606–1615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Getgood, A.; Brown, C.; Lording, T.; Amis, A.; Claes, S.; Geeslin, A.; Musahl, V. The anterolateral complex of the knee: results from the International ALC Consensus Group Meeting. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2019, 27, 166–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hollyer, I.; Sholtis, C.; Loughran, G.; Raji, Y.; Akhtar, M.; Smith, P.A.; Musahl, V.; Verdonk, P.C.M.; Sonnery-Cottet, B.; Getgood, A.; et al. Trends in lateral extra-articular augmentation use and surgical technique with anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction from 2016 to 2023, an ACL study group survey. J isakos 2024, 9, 100356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inderhaug, E.; Stephen, J.M.; Williams, A.; Amis, A.A. Biomechanical Comparison of Anterolateral Procedures Combined With Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction. Am J Sports Med 2017, 45, 347–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAleese, T.; Murgier, J.; Cavaignac, E.; Devitt, B.M. A review of Marcel Lemaire’s original work on lateral extra-articular tenodesis. J isakos 2024, 9, 431–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herbort, M.; Abermann, E.; Feller, J.A.; Fink, C. [Anterolateral stabilization using the modified ellison technique-Treatment of anterolateral instability and reduction of ACL re-rupture risk]. Oper Orthop Traumatol 2022, 34, 231–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neri, T.; Dabirrahmani, D.; Beach, A.; Grasso, S.; Putnis, S.; Oshima, T.; Cadman, J.; Devitt, B.; Coolican, M.; Fritsch, B.; et al. Different anterolateral procedures have variable impact on knee kinematics and stability when performed in combination with anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. J isakos 2021, 6, 74–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rezansoff, A.; Firth, A.D.; Bryant, D.M.; Litchfield, R.; McCormack, R.G.; Heard, M.; MacDonald, P.B.; Spalding, T.; Verdonk, P.C.M.; Peterson, D.; et al. Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction Plus Lateral Extra-articular Tenodesis Has a Similar Return-to-Sport Rate to Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction Alone but a Lower Failure Rate. Arthroscopy 2024, 40, 384–396.e381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sonnery-Cottet, B.; Thaunat, M.; Freychet, B.; Pupim, B.H.; Murphy, C.G.; Claes, S. Outcome of a Combined Anterior Cruciate Ligament and Anterolateral Ligament Reconstruction Technique With a Minimum 2-Year Follow-up. Am J Sports Med 2015, 43, 1598–1605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Wal, W.A.; Meijer, D.T.; Hoogeslag, R.A.G.; LaPrade, R.F. The Iliotibial Band is the Main Secondary Stabilizer for Anterolateral Rotatory Instability and both a Lemaire Tenodesis and Anterolateral Ligament Reconstruction Can Restore Native Knee Kinematics in the Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstructed Knee: A Systematic Review of Biomechanical Cadaveric Studies. Arthroscopy 2024, 40, 632–647.e631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imhoff, F.B.; Mehl, J.; Comer, B.J.; Obopilwe, E.; Cote, M.P.; Feucht, M.J.; Wylie, J.D.; Imhoff, A.B.; Arciero, R.A.; Beitzel, K. Slope-reducing tibial osteotomy decreases ACL-graft forces and anterior tibial translation under axial load. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2019, 27, 3381–3389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mabrouk, A.; Kley, K.; Jacquet, C.; Fayard, J.M.; An, J.S.; Ollivier, M. Outcomes of Slope-Reducing Proximal Tibial Osteotomy Combined With a Third Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction Procedure With a Focus on Return to Impact Sports. Am J Sports Med 2023, 51, 3454–3463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weiler, A.; Gwinner, C.; Wagner, M.; Ferner, F.; Strobel, M.J.; Dickschas, J. Significant slope reduction in ACL deficiency can be achieved both by anterior closing-wedge and medial open-wedge high tibial osteotomies: early experiences in 76 cases. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2022, 30, 1967–1975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shelbourne, K.D.; Nitz, P. Accelerated rehabilitation after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. The American journal of sports medicine 1990, 18, 292–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beynnon, B.D.; Uh, B.S.; Johnson, R.J.; Abate, J.A.; Nichols, C.E.; Fleming, B.C.; Poole, A.R.; Roos, H. Rehabilitation after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a prospective, randomized, double-blind comparison of programs administered over 2 different time intervals. The American journal of sports medicine 2005, 33, 347–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kruse, L.M.; Gray, B.; Wright, R.W. Rehabilitation after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a systematic review. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2012, 94, 1737–1748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glattke, K.E.; Tummala, S.V.; Chhabra, A. Anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction recovery and rehabilitation: a systematic review. JBJS 2022, 104, 739–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manal, T.J.; Snyder-Mackler, L. Practice guidelines for anterior cruciate ligament rehabilitation: a criterion-based rehabilitation progression. Operative techniques in orthopaedics 1996, 6, 190–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotsifaki, R.; Korakakis, V.; King, E.; Barbosa, O.; Maree, D.; Pantouveris, M.; Bjerregaard, A.; Luomajoki, J.; Wilhelmsen, J.; Whiteley, R. Aspetar clinical practice guideline on rehabilitation after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. British Journal of Sports Medicine 2023, 57, 500–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brinlee, A.W.; Dickenson, S.B.; Hunter-Giordano, A.; Snyder-Mackler, L. ACL Reconstruction Rehabilitation: Clinical Data, Biologic Healing, and Criterion-Based Milestones to Inform a Return-to-Sport Guideline. Sports Health 2022, 14, 770–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filbay, S.R.; Grindem, H. Evidence-based recommendations for the management of anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) rupture. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 2019, 33, 33–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Claes, S.; Verdonk, P.; Forsyth, R.; Bellemans, J. The “ligamentization” process in anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: what happens to the human graft? A systematic review of the literature. The American journal of sports medicine 2011, 39, 2476–2483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grindem, H.; Snyder-Mackler, L.; Moksnes, H.; Engebretsen, L.; Risberg, M.A. Simple decision rules can reduce reinjury risk by 84% after ACL reconstruction: the Delaware-Oslo ACL cohort study. British journal of sports medicine 2016, 50, 804–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, R.W.; Preston, E.; Fleming, B.C.; Amendola, A.; Andrish, J.T.; Bergfeld, J.A.; Dunn, W.R.; Kaeding, C.; Kuhn, J.E.; Marx, R.G. A systematic review of anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction rehabilitation–part II: open versus closed kinetic chain exercises, neuromuscular electrical stimulation, accelerated rehabilitation, and miscellaneous topics. The journal of knee surgery 2008, 21, 225–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heijne, A.; Werner, S. Early versus late start of open kinetic chain quadriceps exercises after ACL reconstruction with patellar tendon or hamstring grafts: a prospective randomized outcome study. Knee Surgery, Sports Traumatology, Arthroscopy 2007, 15, 402–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukuda, T.Y.; Fingerhut, D.; Moreira, V.C.; Camarini, P.M.F.; Scodeller, N.F.; Duarte Jr, A.; Martinelli, M.; Bryk, F.F. Open kinetic chain exercises in a restricted range of motion after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a randomized controlled clinical trial. The American journal of sports medicine 2013, 41, 788–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saxena, A.; Granot, A. Use of an anti-gravity treadmill in the rehabilitation of the operated achilles tendon: a pilot study. J Foot Ankle Surg 2011, 50, 558–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vincent, H.K.; Madsen, A.; Vincent, K.R. Role of Antigravity Training in Rehabilitation and Return to Sport After Running Injuries. Arthrosc Sports Med Rehabil 2022, 4, e141–e149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cutuk, A.; Groppo, E.R.; Quigley, E.J.; White, K.W.; Pedowitz, R.A.; Hargens, A.R. Ambulation in simulated fractional gravity using lower body positive pressure: cardiovascular safety and gait analyses. J Appl Physiol (1985) 2006, 101, 771–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minniti, M.C.; Statkevich, A.P.; Kelly, R.L.; Rigsby, V.P.; Exline, M.M.; Rhon, D.I.; Clewley, D. The Safety of Blood Flow Restriction Training as a Therapeutic Intervention for Patients With Musculoskeletal Disorders: A Systematic Review. Am J Sports Med 2020, 48, 1773–1785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franz, A.; Praetorius, A.; Raeder, C.; Hirschmüller, A.; Behringer, M. Blood flow restriction training in the pre-and postoperative phases of joint surgery. Arthroskopie 2023, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takarada, Y.; Takazawa, H.; Ishii, N. Applications of vascular occlusion diminish disuse atrophy of knee extensor muscles. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise 2000, 32, 2035–2039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colapietro, M.; Portnoff, B.; Miller, S.J.; Sebastianelli, W.; Vairo, G.L. Effects of Blood Flow Restriction Training on Clinical Outcomes for Patients with ACL Reconstruction: A Systematic Review. Sports health 2023, 15, 260–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García-Rodríguez, P.; Pecci, J.; Vázquez-González, S.; Pareja-Galeano, H. Acute and Chronic Effects of Blood Flow Restriction Training in Physically Active Patients With Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction: A Systematic Review. Sports Health 2024, 16, 820–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, S.; Rodríguez-Jaime, M.F.; León-Prieto, C. Blood Flow Restriction Training: Physiological Effects, Molecular Mechanisms, and Clinical Applications. Critical Reviews™ in Physical and Rehabilitation Medicine 2024, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoenfeld, B.J.; Grgic, J.; Van Every, D.W.; Plotkin, D.L. Loading recommendations for muscle strength, hypertrophy, and local endurance: a re-examination of the repetition continuum. Sports 2021, 9, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fraca-Fernandez, E.; Ceballos-Laita, L.; Hernandez-Lazaro, H.; Jimenez-Del-Barrio, S.; Mingo-Gomez, M.T.; Medrano-de-la-Fuente, R.; Hernando-Garijo, I. Effects of Blood Flow Restriction Training in Patients before and after Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Healthcare (Basel) 2024, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lixandrão, M.E.; Ugrinowitsch, C.; Berton, R.; Vechin, F.C.; Conceição, M.S.; Damas, F.; Libardi, C.A.; Roschel, H. Magnitude of muscle strength and mass adaptations between high-load resistance training versus low-load resistance training associated with blood-flow restriction: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sports medicine 2018, 48, 361–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kacin, A.; Drobnic, M.; Mars, T.; Mis, K.; Petric, M.; Weber, D.; Tomc Zargi, T.; Martincic, D.; Pirkmajer, S. Functional and molecular adaptations of quadriceps and hamstring muscles to blood flow restricted training in patients with ACL rupture. Scand J Med Sci Sports 2021, 31, 1636–1646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Žargi, T.; Drobnič, M.; Stražar, K.; Kacin, A. Short–term preconditioning with blood flow restricted exercise preserves quadriceps muscle endurance in patients after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Frontiers in physiology 2018, 9, 1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tramer, J.S.; Khalil, L.S.; Jildeh, T.R.; Abbas, M.J.; McGee, A.; Lau, M.J.; Moutzouros, V.; Okoroha, K.R. Blood Flow Restriction Therapy for 2 Weeks Prior to Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction Did Not Impact Quadriceps Strength Compared to Standard Therapy. Arthroscopy: The Journal of Arthroscopic & Related Surgery 2023, 39, 373–381. [Google Scholar]

- Zargi, T.G.; Drobnic, M.; Jkoder, J.; Strazar, K.; Kacin, A. The effects of preconditioning with ischemic exercise on quadriceps femoris muscle atrophy following anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a quasi-randomized controlled trial. 2016.

- Kubota, A.; Sakuraba, K.; Sawaki, K.; Sumide, T.; Tamura, Y. Prevention of disuse muscular weakness by restriction of blood flow. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise 2008, 40, 529–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hughes, L.; Paton, B.; Rosenblatt, B.; Gissane, C.; Patterson, S.D. Blood flow restriction training in clinical musculoskeletal rehabilitation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. British journal of sports medicine 2017, 51, 1003–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iversen, E.; Røstad, V.; Larmo, A. Intermittent blood flow restriction does not reduce atrophy following anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Journal of sport and health science 2016, 5, 115–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hughes, L.; Rosenblatt, B.; Haddad, F.; Gissane, C.; McCarthy, D.; Clarke, T.; Ferris, G.; Dawes, J.; Paton, B.; Patterson, S.D. Comparing the Effectiveness of Blood Flow Restriction and Traditional Heavy Load Resistance Training in the Post-Surgery Rehabilitation of Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction Patients: A UK National Health Service Randomised Controlled Trial. Sports Med 2019, 49, 1787–1805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohta, H.; Kurosawa, H.; Ikeda, H.; Iwase, Y.; Satou, N.; Nakamura, S. Low-load resistance muscular training with moderate restriction of blood flow after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Acta Orthopaedica Scandinavica 2003, 74, 62–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curran, M.T.; Bedi, A.; Mendias, C.L.; Wojtys, E.M.; Kujawa, M.V.; Palmieri-Smith, R.M. Blood flow restriction training applied with high-intensity exercise does not improve quadriceps muscle function after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a randomized controlled trial. The American Journal of Sports Medicine 2020, 48, 825–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papaleontiou, A.; Poupard, A.M.; Mahajan, U.D.; Tsantanis, P. Conservative vs Surgical Treatment of Anterior Cruciate Ligament Rupture: A Systematic Review. Cureus 2024, 16, e56532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grevnerts, H.T.; Sonesson, S.; Gauffin, H.; Ardern, C.L.; Stålman, A.; Kvist, J. Decision making for treatment after ACL injury from an orthopaedic surgeon and patient perspective: results from the NACOX study. Orthopaedic Journal of Sports Medicine 2021, 9, 23259671211005090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grevnerts, H.T.; Krevers, B.; Kvist, J. Treatment decision-making process after an anterior cruciate ligament injury: patients’, orthopaedic surgeons’ and physiotherapists’ perspectives. BMC musculoskeletal disorders 2022, 23, 782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webster, K.E.; Feller, J.A. Who Passes Return-to-Sport Tests, and Which Tests Are Most Strongly Associated With Return to Play After Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction? Orthop J Sports Med 2020, 8, 2325967120969425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyritsis, P.; Bahr, R.; Landreau, P.; Miladi, R.; Witvrouw, E. Likelihood of ACL graft rupture: not meeting six clinical discharge criteria before return to sport is associated with a four times greater risk of rupture. Br J Sports Med 2016, 50, 946–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capin, J.J.; Snyder-Mackler, L.; Risberg, M.A.; Grindem, H. Keep calm and carry on testing: a substantive reanalysis and critique of ’what is the evidence for and validity of return-to-sport testing after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction surgery? A systematic review and meta-analysis’. Br J Sports Med 2019, 53, 1444–1446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardern, C.L.; Glasgow, P.; Schneiders, A.; Witvrouw, E.; Clarsen, B.; Cools, A.; Gojanovic, B.; Griffin, S.; Khan, K.M.; Moksnes, H.; et al. 2016 Consensus statement on return to sport from the First World Congress in Sports Physical Therapy, Bern. Br J Sports Med 2016, 50, 853–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doege, J.; Ayres, J.M.; Mackay, M.J.; Tarakemeh, A.; Brown, S.M.; Vopat, B.G.; Mulcahey, M.K. Defining Return to Sport: A Systematic Review. Orthop J Sports Med 2021, 9, 23259671211009589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckthorpe, M. Optimising the Late-Stage Rehabilitation and Return-to-Sport Training and Testing Process After ACL Reconstruction. Sports Med 2019, 49, 1043–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckthorpe, M.; Della Villa, F. Optimising the ’Mid-Stage’ Training and Testing Process After ACL Reconstruction. Sports Med 2020, 50, 657–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buckthorpe, M.; Gokeler, A.; Herrington, L.; Hughes, M.; Grassi, A.; Wadey, R.; Patterson, S.; Compagnin, A.; La Rosa, G.; Della Villa, F. Optimising the Early-Stage Rehabilitation Process Post-ACL Reconstruction. Sports Med 2024, 54, 49–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adams, D.; Logerstedt, D.; Hunter-Giordano, A.; Axe, M.J.; Snyder-Mackler, L. Current concepts for anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a criterion-based rehabilitation progression. journal of orthopaedic & sports physical therapy 2012, 42, 601–614. [Google Scholar]

- Davies, G.J.; McCarty, E.; Provencher, M.; Manske, R.C. ACL Return to Sport Guidelines and Criteria. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med 2017, 10, 307–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, W.T.; Myer, G.D.; Read, P.J. Is It Time We Better Understood the Tests We are Using for Return to Sport Decision Making Following ACL Reconstruction? A Critical Review of the Hop Tests. Sports Med 2020, 50, 485–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dingenen, B.; Gokeler, A. Optimization of the Return-to-Sport Paradigm After Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction: A Critical Step Back to Move Forward. Sports Med 2017, 47, 1487–1500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gokeler, A.; Dingenen, B.; Hewett, T.E. Rehabilitation and Return to Sport Testing After Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction: Where Are We in 2022? Arthrosc Sports Med Rehabil 2022, 4, e77–e82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rambaud, A.J.M.; Ardern, C.L.; Thoreux, P.; Regnaux, J.P.; Edouard, P. Criteria for return to running after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a scoping review. Br J Sports Med 2018, 52, 1437–1444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paterno, M.V. Incidence and Predictors of Second Anterior Cruciate Ligament Injury After Primary Reconstruction and Return to Sport. J Athl Train 2015, 50, 1097–1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McBurnie, A.J.; Dos’ Santos, T. Multidirectional speed in youth soccer players: theoretical underpinnings. Strength & Conditioning Journal 2022, 44, 15–33. [Google Scholar]

- Wright, R.W.; Fetzer, G.B. Bracing after ACL reconstruction: a systematic review. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2007, 455, 162–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Miceli, R.; Marambio, C.B.; Zati, A.; Monesi, R.; Benedetti, M.G. Do Knee Bracing and Delayed Weight Bearing Affect Mid-Term Functional Outcome after Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction? Joints 2017, 5, 202–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowe, W.R.; Warth, R.J.; Davis, E.P.; Bailey, L. Functional Bracing After Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction: A Systematic Review. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 2017, 25, 239–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moller, E.; Forssblad, M.; Hansson, L.; Wange, P.; Weidenhielm, L. Bracing versus nonbracing in rehabilitation after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a randomized prospective study with 2-year follow-up. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2001, 9, 102–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grant, J.A. Updating recommendations for rehabilitation after ACL reconstruction: a review. Clinical Journal of Sport Medicine 2013, 23, 501–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodríguez-Merchán, E.C. Knee bracing after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Orthopedics 2016, 39, e602–e609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoepp, C.; Ohmann, T.; Martin, W.; Praetorius, A.; Seelmann, C.; Dudda, M.; Stengel, D.; Hax, J. Brace-free rehabilitation after isolated anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction with hamstring tendon autograft is not inferior to brace-based rehabilitation—A randomised controlled trial. Journal of Clinical Medicine 2023, 12, 2074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prill, R.; Janosky, J.; Bode, L.; van Melick, N.; Della Villa, F.; Becker, R.; Karlsson, J.; Gudas, R.; Gokeler, A.; Jones, H. Prevention of ACL injury is better than repair or reconstruction-Implementing the ESSKA-ESMA’Prevention for All’ACL programme. Knee Surgery and Arthroscopy 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webster, K.E.; Hewett, T.E. Meta-analysis of meta-analyses of anterior cruciate ligament injury reduction training programs. Journal of Orthopaedic Research® 2018, 36, 2696–2708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bizzini, M.; Dvorak, J. FIFA 11+: an effective programme to prevent football injuries in various player groups worldwide—a narrative review. British journal of sports medicine 2015, 49, 577–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, H.; Patt, T.; Thoureux, P.; Della Villa, F. ACL Prevention for All. The ESSKA-ESMA prevention programme in children and adolescents.

- Wang, K.C.; Keeley, T.; Lansdown, D.A. Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction: Common Intraoperative Mistakes and Techniques for Error Recovery. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizvanovic, D.; Waldén, M.; Forssblad, M.; Stålman, A. Influence of Surgeon Experience and Clinic Volume on Subjective Knee Function and Revision Rates in Primary ACL Reconstruction: A Study from the Swedish National Knee Ligament Registry. Orthop J Sports Med 2024, 12, 23259671241233695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bitschi, D.; Fürmetz, J.; Gilbert, F.; Jörgens, M.; Watrinet, J.; Pätzold, R.; Lang, C.; Neidlein, C.; Böcker, W.; Bormann, M. Preoperative Mixed-Reality Visualization of Complex Tibial Plateau Fractures and Its Benefit Compared to CT and 3D Printing. J Clin Med 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueroa, F.; Figueroa, D.; Guiloff, R.; Putnis, S.; Fritsch, B.; Itriago, M. Navigation in anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: State of the art. J isakos 2023, 8, 47–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rilk, S.; Goodhart, G.C.; van der List, J.P.; Von Rehlingen-Prinz, F.; Vermeijden, H.D.; O’Brien, R.; DiFelice, G.S. Anterior cruciate ligament primary repair revision rates are increased in skeletally mature patients under the age of 21 compared to reconstruction, while adults (>21 years) show no significant difference: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2025, 33, 29–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vermeijden, H.D.; van der List, J.P.; O’Brien, R.J.; DiFelice, G.S. Primary Repair of Anterior Cruciate Ligament Injuries: Current Level of Evidence of Available Techniques. JBJS Rev 2021, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amini, M.; Venkatesan, J.K.; Liu, W.; Leroux, A.; Nguyen, T.N.; Madry, H.; Migonney, V.; Cucchiarini, M. Advanced Gene Therapy Strategies for the Repair of ACL Injuries. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gögele, C.; Hahn, J.; Schulze-Tanzil, G. Anatomical Tissue Engineering of the Anterior Cruciate Ligament Entheses. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wade, L.; Needham, L.; McGuigan, P.; Bilzon, J. Applications and limitations of current markerless motion capture methods for clinical gait biomechanics. PeerJ 2022, 10, e12995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, N.; Sigurðsson, H.B.; Seymore, K.D.; Arhos, E.K.; Buchanan, T.S.; Snyder-Mackler, L.; Silbernagel, K.G. Markerless motion capture: What clinician-scientists need to know right now. JSAMS plus 2022, 1, 100001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, S.; Krahl, D.; Podszun, J.; Knecht, S.; Zimmerer, A.; Sobau, C.; Ellermann, A.; Ruhl, A. Combining a digital health application with standard care significantly enhances rehabilitation outcomes for ACL surgery patients. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2025, 33, 1241–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunphy, E.; Hamilton, F.L.; Spasic, I.; Button, K. Acceptability of a digital health intervention alongside physiotherapy to support patients following anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2017, 18, 471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verhagen, E.A.; Clarsen, B.; Bahr, R. A peek into the future of sports medicine: the digital revolution has entered our pitch. Br J Sports Med 2014, 48, 739–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andriollo, L.; Picchi, A.; Sangaletti, R.; Perticarini, L.; Rossi, S.M.P.; Logroscino, G.; Benazzo, F. The Role of Artificial Intelligence in Anterior Cruciate Ligament Injuries: Current Concepts and Future Perspectives. Healthcare (Basel) 2024, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corban, J.; Lorange, J.P.; Laverdiere, C.; Khoury, J.; Rachevsky, G.; Burman, M.; Martineau, P.A. Artificial Intelligence in the Management of Anterior Cruciate Ligament Injuries. Orthop J Sports Med 2021, 9, 23259671211014206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tamimi, I.; Ballesteros, J.; Lara, A.P.; Tat, J.; Alaqueel, M.; Schupbach, J.; Marwan, Y.; Urdiales, C.; Gomez-de-Gabriel, J.M.; Burman, M.; et al. A Prediction Model for Primary Anterior Cruciate Ligament Injury Using Artificial Intelligence. Orthop J Sports Med 2021, 9, 23259671211027543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taborri, J.; Molinaro, L.; Santospagnuolo, A.; Vetrano, M.; Vulpiani, M.C.; Rossi, S. A Machine-Learning Approach to Measure the Anterior Cruciate Ligament Injury Risk in Female Basketball Players. Sensors (Basel) 2021, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, W.R.; Mian, A.; Lloyd, D.G.; Alderson, J.A. On-field player workload exposure and knee injury risk monitoring via deep learning. J Biomech 2019, 93, 185–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richter, C.; King, E.; Strike, S.; Franklyn-Miller, A. Objective classification and scoring of movement deficiencies in patients with anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. PLoS One 2019, 14, e0206024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, R.K.; Ley, C.; Pareek, A.; Groll, A.; Tischer, T.; Seil, R. Artificial intelligence and machine learning: an introduction for orthopaedic surgeons. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2022, 30, 361–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kakavas, G.; Malliaropoulos, N.; Pruna, R.; Traster, D.; Bikos, G.; Maffulli, N. Neuroplasticity and Anterior Cruciate Ligament Injury. Indian J Orthop 2020, 54, 275–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kakavas, G.; Malliaropoulos, N.; Bikos, G.; Pruna, R.; Valle, X.; Tsaklis, P.; Maffulli, N. Periodization in Anterior Cruciate Ligament Rehabilitation: A Novel Framework. Med Princ Pract 2021, 30, 101–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, A.B.; Grazal, C.F.; Balazs, G.C.; Potter, B.K.; Dickens, J.F.; Forsberg, J.A. Can Predictive Modeling Tools Identify Patients at High Risk of Prolonged Opioid Use After ACL Reconstruction? Clin Orthop Relat Res 2020, 478, 0–1618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tighe, P.; Laduzenski, S.; Edwards, D.; Ellis, N.; Boezaart, A.P.; Aygtug, H. Use of machine learning theory to predict the need for femoral nerve block following ACL repair. Pain Med 2011, 12, 1566–1575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.H.; Asch, S.M. Machine Learning and Prediction in Medicine - Beyond the Peak of Inflated Expectations. N Engl J Med 2017, 376, 2507–2509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bien, N.; Rajpurkar, P.; Ball, R.L.; Irvin, J.; Park, A.; Jones, E.; Bereket, M.; Patel, B.N.; Yeom, K.W.; Shpanskaya, K.; et al. Deep-learning-assisted diagnosis for knee magnetic resonance imaging: Development and retrospective validation of MRNet. PLoS Med 2018, 15, e1002699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Štajduhar, I.; Mamula, M.; Miletić, D.; Ünal, G. Semi-automated detection of anterior cruciate ligament injury from MRI. Comput Methods Programs Biomed 2017, 140, 151–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Li, M.; Zhou, Y.; Lu, G.; Zhou, Q. Deep Learning Approach for Anterior Cruciate Ligament Lesion Detection: Evaluation of Diagnostic Performance Using Arthroscopy as the Reference Standard. J Magn Reson Imaging 2020, 52, 1745–1752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swain, M.S.; Henschke, N.; Kamper, S.J.; Downie, A.S.; Koes, B.W.; Maher, C.G. Accuracy of clinical tests in the diagnosis of anterior cruciate ligament injury: a systematic review. Chiropr Man Therap 2014, 22, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luites, J.W.; Wymenga, A.B.; Blankevoort, L.; Eygendaal, D.; Verdonschot, N. Accuracy of a computer-assisted planning and placement system for anatomical femoral tunnel positioning in anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Int J Med Robot 2014, 10, 438–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafizadeh, S.; Balke, M.; Wegener, S.; Tjardes, T.; Bouillon, B.; Hoeher, J.; Baethis, H. Precision of tunnel positioning in navigated anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Arthroscopy 2011, 27, 1268–1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sopilidis, A.; Stamatopoulos, V.; Giannatos, V.; Taraviras, G.; Panagopoulos, A.; Taraviras, S. Integrating Modern Technologies into Traditional Anterior Cruciate Ligament Tissue Engineering. Bioengineering (Basel) 2025, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dye, S.F. The future of anterior cruciate ligament restoration. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1996, 130–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gokeler, A.; Grassi, A.; Hoogeslag, R.; van Houten, A.; Bolling, C.; Buckthorpe, M.; Norte, G.; Benjaminse, A.; Heuvelmans, P.; Di Paolo, S.; et al. Return to sports after ACL injury 5 years from now: 10 things we must do. J Exp Orthop 2022, 9, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarlis, V.; Papageorgiou, G.; Tjortjis, C. Injury patterns and impact on performance in the NBA League Using Sports Analytics. Computation 2024, 12, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daggett, M.C.; Witte, K.A.; Cabarkapa, D.; Cabarkapa, D.V.; Fry, A.C. Evidence-Based Data Models for Return-to-Play Criteria after Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction. Healthcare (Basel) 2022, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, H.H.; Berlinberg, E.J.; Nwachukwu, B.; Williams, R.J., 3rd; Mandelbaum, B.; Sonkin, K.; Forsythe, B. Quadriceps Weakness is Associated with Neuroplastic Changes Within Specific Corticospinal Pathways and Brain Areas After Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction: Theoretical Utility of Motor Imagery-Based Brain-Computer Interface Technology for Rehabilitation. Arthrosc Sports Med Rehabil 2023, 5, e207–e216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pataky, T.C. One-dimensional statistical parametric mapping in Python. Computer methods in biomechanics and biomedical engineering 2012, 15, 295–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDevitt, E.R.; Taylor, D.C.; Miller, M.D.; Gerber, J.P.; Ziemke, G.; Hinkin, D.; Uhorchak, J.M.; Arciero, R.A.; Pierre, P.S. Functional bracing after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a prospective, randomized, multicenter study. Am J Sports Med 2004, 32, 1887–1892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harilainen, A.; Sandelin, J. Post-operative use of knee brace in bone-tendon-bone patellar tendon anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: 5-year follow-up results of a randomized prospective study. Scand J Med Sci Sports 2006, 16, 14–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harilainen, A.; Sandelin, J.; Vanhanen, I.; Kivinen, A. Knee brace after bone-tendon-bone anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Randomized, prospective study with 2-year follow-up. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 1997, 5, 10–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muellner, T.; Alacamlioglu, Y.; Nikolic, A.; Schabus, R. No benefit of bracing on the early outcome after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 1998, 6, 88–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, Y.; Deie, M.; Adachi, N.; Kobayashi, K.; Kanaya, A.; Miyamoto, A.; Nakasa, T.; Ochi, M. A prospective study of 3-day versus 2-week immobilization period after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Knee 2007, 14, 34–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birmingham, T.B.; Bryant, D.M.; Giffin, J.R.; Litchfield, R.B.; Kramer, J.F.; Donner, A.; Fowler, P.J. A randomized controlled trial comparing the effectiveness of functional knee brace and neoprene sleeve use after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Am J Sports Med 2008, 36, 648–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birmingham, T.B.; Kramer, J.F.; Kirkley, A. Effect of a functional knee brace on knee flexion and extension strength after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2002, 83, 1472–1475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Birmingham, T.B.; Kramer, J.F.; Kirkley, A.; Inglis, J.T.; Spaulding, S.J.; Vandervoort, A.A. Knee bracing after ACL reconstruction: effects on postural control and proprioception. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2001, 33, 1253–1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Phase | Training Goals |

| Prehabilitation: | “Quiet Knee”, Development of Muscle Strength |

| Recovery from Surgery (RFS) | Clinical Care and Inflammatory Management |

| Return-to-Activity (RTA): | Neuromuscular Control and Resistance Training |

| Return-to-Running (RTR): | Strength, Power, and Energy Systems Training |

| Return-to-Sports (RTS): | Speed, Agility, and High-Intensity Interval Training (On-Field and Restricted Team Training) |

| Return-to-Play (RTP): | Readiness to Play and Compete (Full Team Training) |

| Return-to-Competition (RTC) | Competitive Performance & Injury Prevention |

| Phase | Goals | Intervention | Progression Criteria |

|---|---|---|---|

|

RFS – Recovery of Surgery Week 1 to 2 |

Reduction of pain and swelling Optimization of knee mobility and activation Pain-adapted increase of daily activities |

Passive & active knee mobilization, patella mobilization Gait training (initially partial weight-bearing if necessary) Decongestive exercises, electrical stimulation and quadriceps isometrics, mobilization of adjacent joints Core and hip stabilizer training Balance & perturbation training, 30° mini squats Strength training of the contralateral limb and upper extremity |

Passive ROM (P-ROM): 0-0–90° Modified stroke effusion test: moderate 1+ Quadriceps activation with proximal patella glide (visibly observable) Straight leg raise test without extension lag Active knee extension during walking possible KOS-ADL ≥ 85% |

|

RTA – Return-to-Activity Week 3 to 12 |

Normalization of knee mobility Optimization of strength and movement coordination Normalization of gait pattern, stair climbing, cycling |

Passive & active knee mobilization, scar mobilization Intensive gait training BFR-Training, NMES, intensified perturbation training Closed-kinetic chain resistance training: Week 5: 0–60° ROM, Week 7: 0–90° ROM, Week 9: full ROM (focus on fundamental movement patterns) Open kinetic chain resistance training = from week 9: 90–40° ROM (10° weekly increase; no restrictions from week 13) Week 11: running drills, bi- and unilateral jumps (landing) Gait-running progression, upper extremity strength training |

P-ROM: 0-0-120° (6 weeks), 0-0-LSI [°] ≤ 10 (12 weeks) Modified stroke effusion test: none to minimal Y-Balance LSI [cm] ≥ 95%, Composite Score > 94% Knee extension/flexion strength LSI [Nm] ≥ 70% 10-minute jog at 10–12 km/h possible Jump and hop tests LSI [N, cm] ≥ 70% Single-leg 60° squat and jump-landing pattern with stable trunk-pelvis-leg axis |

|

RTR – Return-to-Running Week 14 to 24 |

Performance optimization in short and long SSC (stretch-shortening cycle) Development of running resilience and performance | Intensified running drills, bi- and unilateral plyometric & jump training Technique training for lateral & multidirectional locomotion Machine-based strength training in open & closed kinetic chain (15–8 RM) Strength training with free weights (12–6 RM; focus on fundamental patterns), eccentric strength training Core strength training (focus on force transfer, e.g., medicine ball throws) Linear running progression, HIIT sequences, on-field technique sessions |

Knee extension/flexion strength LSI [Nm] ≥ 80% Flexion-extension ratio ≥ 60% Jump and hop tests LSI [N, cm] ≥ 80% Stable trunk-pelvis-leg axis in planned jumping and cutting maneuvers |

|

RTS – Return-to-Sports Week 25 to 34 |

Performance optimization of speed actions Sport-specific movement patterns Restricted team training |

Progressive sprint development, short intense HIIT sessions (45–15 sec) Intensification of multidirectional locomotion (to fatigue) Development of technical-tactical performance prerequisites Technique stabilization in bi- and unilateral plyometrics (to fatigue) Technique stabilization of intense COD actions (to fatigue) Optimization of maximal and explosive strength (6–4 RM) Eccentric strength training (in end-range joint positions) |

Knee extension/flexion strength LSI [Nm] ≥ 90% Knee extension > 2.5 Nm/kg body weight Jump and hop tests LSI [N, cm] ≥ 90–95% Stable trunk-pelvis-leg axis in unplanned jumping and cutting actions ♂: VIFT ≥ 20 km/h, ♀: VIFT ≥ 18 km/h ACL-RSI Score > 65% |

|

RTP – Return-to-Play From week 35 |

Sport-specific training and competitive exposure (full team training) | Pressing & tackling, gradual increase of competitive match minutes Development of individual prevention routines, e.g., FIFA 11+, PEP, KIPP Maintenance of maximal & explosive strength, endurance performance |

|

| ROM = Range of Motion, KOS-ADL = Knee Outcome Survey – Activities of Daily Living, LSI = Limb Symmetry Index, Nm = Newton meter, Comp. Score = Composite Score, SAS = Sports Activity Scale, COD = change of direction, VIFT = Final velocity in the 30-15 Intermittent Fitness Test (IFT), ACL-RSI = ACL – Return to sport after injury scale. | |||

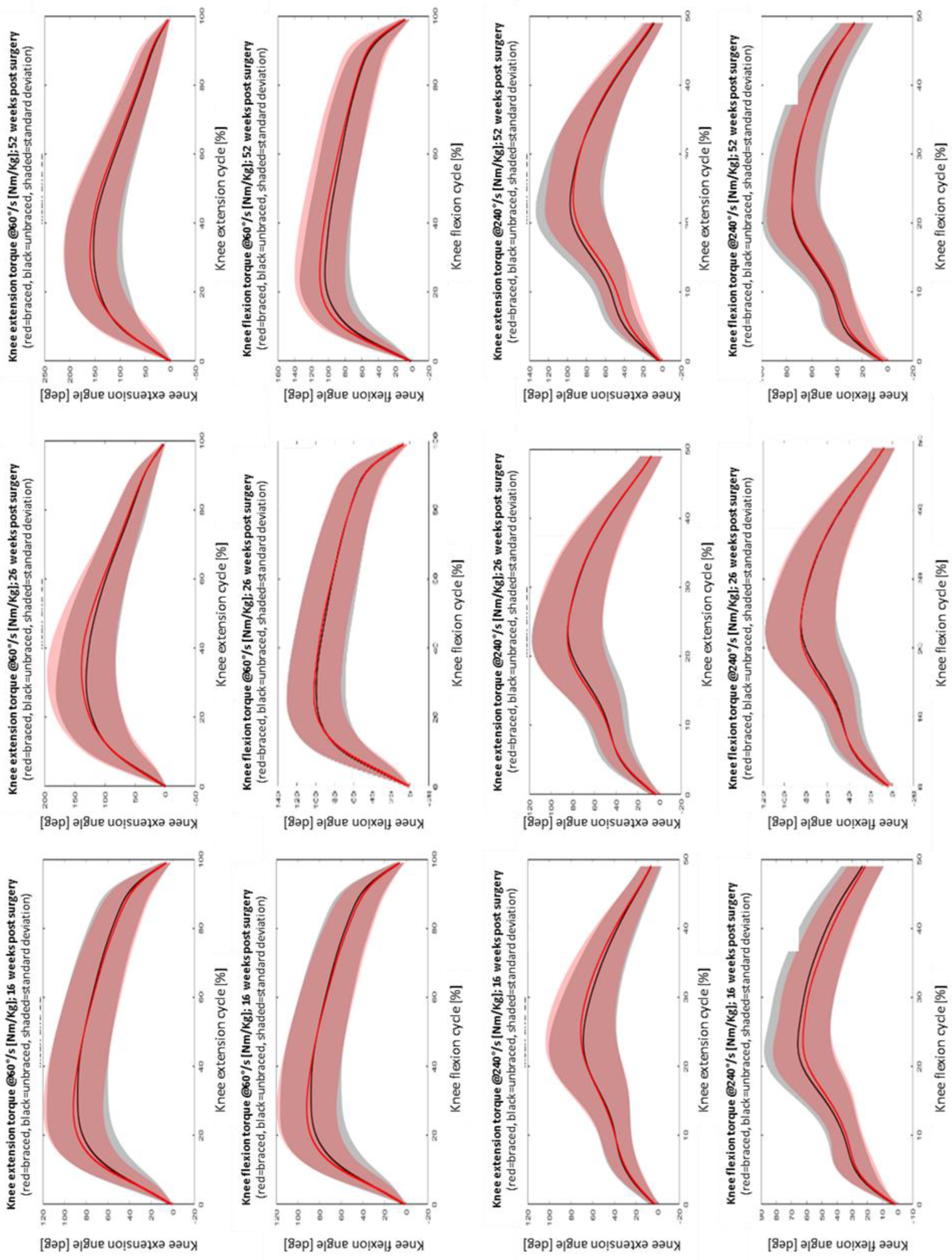

| Extension | Flexion | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brace-free | braced | Brace-free | Braced | ||

| 16 weeks | 240°/sec | 0.89±0.38 | 0.89±0.35 | 0.87±0.22 | 0.86±0.17 |

| 60°/sec | 1.55±0.59 | 1.50±0.50 | 1.14±0.29 | 1.14±0.25 | |

| 26 weeks | 240°/sec | 1.10±0.37 | 1.05±0.29 | 0.99±0.22 | 0.96±0.18 |

| 60°/sec | 1.74±0.65 | 1.75±0.51 | 1.27±0.33 | 1.28±0.26 | |

| 52 weeks | 240°/sec | 1.27±0.44 | 1.20±0.33 | 1.03±0.29 | 0.98±0.25 |

| 60°/sec | 2.09±0.74 | 2.05±0.59 | 1.38±0.36 | 1.37±0.34 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).