1. Introduction

The anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) is crucial for knee stability, especially in sports that require dynamic movements such as pivoting, cutting, and jumping. [

1] ACL injuries are particularly common among athletes, both recreational and professional, and can significantly impair performance and quality of life. [

2,

3]

Surgical treatment of ACL injuries is supported by most authors to restore joint kinematics, preserve the cartilage and meniscus structures and increase the chances of returning to sport activities. [

2] Anatomic ACL reconstruction is universally recognized as “the gold-standard” [

2], and independent drilling techniques (such as anteromedial portal and outside-in approaches) are proven to be more reliable in achieving this goal. [

4,

5] However, recent modifications of the traditional transtibial technique made this approach more accurate, providing precise graft placement and minimizing surgical complications. [

1] Theoretical advantages of this technique include a suboptimal graft orientation with lower bending angle [

6] which may reduce stress on the graft, thus facilitating graft incorporation and longevity. [

7]

Several studies have highlighted outcomes of the modified transtibial technique in terms of knee stability and function [

1], though outcomes can vary based on athlete demographics and injury severity. [

8,

9] Questions remain regarding the results of the modified transtibial technique in achieving both favorable clinical outcomes and successful return to sport, particularly comparing recreational and professional athletes. The return to sport and the level of activity resumed are not secondary issues, since a stable knee may not be good enough for the athletic demands of elite-level sports in cases of lower game performance. [

3,

8]

The purpose of this study is to evaluate clinical outcomes and return to sport after ACL reconstruction using a modified transtibial technique. The hypothesis is that good clinical outcomes and high rates of return to sports activity can be achieved with this technique, both in professional and recreational athletes.

2. Materials and Methods

A retrospective analysis of all athletic patients undergoing primary ACL reconstruction between January 2020 and December 2023 was conducted according to the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) guidelines. [

10] The study received the local ethics committee approval (no. 215/CEL in 10/21/2024) prior to data extraction and was performed in accordance with the World Medical Association’s 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments. [

11] All patients included in this study signed specific informed consent for data collection and elaboration in anonymous and/or aggregate form.

2.1. Patient Inclusion and Selection Criteria

Inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) primary ACL reconstruction during the time lapse reported above, (2) athletic athletes participating in team or individual sports and requiring regular competition and constant training, (3) athletes consenting personal data collection for the purpose of the study and (4) minimum follow-up of 12 months. A patient was defined as a professional athlete if he obtained more than 50% of his income through his sport; otherwise, he was considered as a recreational athlete.

After identification of all eligible cases, a stepwise exclusion process was carried out if any one of the following exclusion criteria was met: (1) concomitant procedures requiring longer period of rehabilitation and longer absence from sport activity (posterior cruciate ligament reconstruction, chondral or osteochondral transfer surgery, osteotomies), (2) medical past history of ACL injuries in the contralateral knee before the index surgery and (3) locked knees for articular loose bodies or displaced bucket-handle meniscus tears, which prevent a proper evaluation of knee stability.

2.2. Surgical Technique and Rehabilitation Protocol

In all patients, the ACL reconstruction was performed using the same modified transtibial technique [

12]. The tibial tunnel was created by locating the starting point on the tibial surface near the anterior fibers of the medial collateral ligament, with the guide set at 45°. An offset femoral guide was introduced through the tibial tunnel to create the femoral tunnel. The femoral guide was then gently rotated until the femoral ACL footprint was reached. After creation of the femoral tunnel, the graft was pulled into the joint through the tibial tunnel. Femoral fixation was performed using a suspension cortical button (Endobutton, Smith & Nephew, Andover, MA, USA). On the tibial side, fixation was completed at 20° of knee flexion using a bioabsorbable interference screw (BIOSURE-HA, Smith and Nephew, Andover, MA, USA) for soft-tissue grafts, while a 7-mm metallic interference screw (SOFT SILK, Smith and Nephew, Andover, MA, USA) was used for graft with bone blocks. Hamstrings, bone-patellar tendon-bone (BPTB) and quadriceps tendon (QT) with bone block were the chosen autograft according to the surgeons’ preference and patients’ desired sport activity to resume. Lateral extra-articular tenodesis (LET) was performed in selected cases using the Cocker-Arnold technique [

13]. This concomitant procedure was added at the surgeons’ discretion, usually in cases of graft size less than 8 mm, high-grade pivot-shift without concomitant lateral meniscus tears and/or signs of constitutional hyperlaxity.

After ACL reconstruction, the knee was placed in a hinged knee brace in full extension during ambulation and sleeping for the first 3 - 6 weeks, according to the presence or absence of concomitant meniscus repairs. Similarly, the complete range of motion and full weight-bearing was allowed after 3 to 6 weeks. Forward running and sports-specific agility movements were granted after 10-12 weeks, while complete return to sports (including cutting sports) was allowed usually after 5–6 months, after full recovery of the quadriceps muscle tone and athletes’ psychological readiness.

2.3. Data Collection

From each selected case, medical records and surgical reports were reviewed by two authors (MM, MG), extracting the following data: patient’s sex, age at the time of surgery, body mass index (BMI), time elapsed from the injury to the surgery, data obtained from the standard preoperative clinical evaluation (including the Lachman test, the Pivot Shift test and arthrometric examination), patient’s level of sports activity (rated according to the Tegner Score [

14]), preoperative clinical scores (Lysholm score [

15] and IKDC subjective score [

16]), details of the surgical procedure (including presence of associated meniscal lesions with related treatment, type of chosen graft with size, concomitant LET procedures).

The standard preoperative clinical evaluation was performed by two of the three most experienced surgeons in knee arthroscopy among the authors (AR, GGC), using the objective IKDC form. [

17] This evaluation was performed for each case in the operating room, with the patient under epidural or general anesthesia. The standard evaluation of knee stability included the Lachman and Pivot-shift test. The Lachman test was rated as 0 (no increased laxity), +1 (slightly increased laxity with a firm end point), +2 (increased translation with a delayed end point), or +3 (translation with soft end point). Lachman test graded as 0 or +1 was defined as low grade, while a test rated +2 or + 3 was considered as a high grade. Similarly, the pivot-shift test was evaluated as 0 (with no shift), 1+ (gliding), 2+ (clunk) and 3+ (gross rotary laxity). A 0 or +1 pivot shift test was categorized as low grade, otherwise it was counted among high-grade tests. Any disagreement was discussed between the authors, until a joint agreement was reached and transcribed in the medical record.

In addition to this, the KT-1000 knee ligament arthrometer (MEDmetric Corp, San Diego, CA, USA) was used to objectively quantify the anteroposterior laxity of the knee. [

18] The test was performed by one of the same three experienced authors while the patient was awake in his room. The anteriorly directed push was applied on both knees using the manual-maximum force. The side-to-side difference was considered normal if < 3 mm, higher than usual if between 3 mm and 5 mm, and frankly abnormal if > 5 mm.

2.4. Final Follow-Up Examination

All selected athletes were recalled and invited for clinical examination after at least 12 months of follow-up. The clinical examination consisted in evaluation of the outcomes using the same clinical and functional scores mentioned above (Lysholm score and IKDC subjective score), as well as objective assessment of the knee stability using the Lachman, Pivot shift and arthrometric tests. These tests were executed by one of the same experienced knee surgeons which evaluated the joint stability before the surgery. In addition to this, athletes were asked if they returned to sports, the type of resumed sport (categorized according to the Tegner Score), and time needed for full return to sport activity. In case the athletes did not return to sports, the reasons were investigated.

If the athletes were not available for the clinical examination, clinical outcomes were investigated by phone interview to collect functional scores and data related to sports activity. Complications, reoperations with related reasons (including ACL graft revision) and ACL graft reruptures were also indagated and recorded. Contralateral ACL ruptures were also asked and reported. Overall composite failure rate was calculated at final follow-up as the sum of graft reruptures (with or without ACL revision surgery) and clinical failures (graft insufficiencies demonstrated with at least two of the three following criteria: high-grade Lachman test ≥ 2, high-grade pivot-shift test ≥ 2 and frankly abnormal KT-1000 side-to side difference greater of 5 mm.)

2.5. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS® Version 25 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL, USA). Categorical variables were reported as percentages or frequencies, and the continuous variables were expressed as arithmetic mean ± standard deviation (SD). Comparison of the categorical variables was performed using the Pearson Chi-squared test or the Fisher’s exact test, where appropriate. Comparison of the continuous variables was performed with the paired-samples T-test or the Mann Whitney non-parametric test, after examining the normality of data distribution using the Shapiro-Wilk test. Kaplan-Meier survival curves were generated to analyze survivorship using the following endpoints: (1) cumulative ACL failure, (2) contralateral ACL rupture, (3) reoperation for any reason except for ACL graft revision and contralateral ACL rupture.

Comparison of survival curves between professional and recreational athletes was performed using the Mantel-Cox log-rank test. The level of significance was set at α = 0.05, and p values < 0.05 indicate a statistically significant difference.

3. Results

From an initial count of 62 eligible athletes, 44 athletes were available and included in the present study. Of the latter, 29 (65.9%) were available for in-person clinical and instrumental evaluation, while the remaining 15 (34.1%) were investigated by phone interview to collect functional scores, return to sports and to document any complications, reruptures, and revision surgeries. The final sample consisted of 7 (15.9%) female and 37 (84.1%) male athletes, with a mean age at surgery of 21.2 ± 5.0 years (

Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline demographics and surgical details of the sample evaluated in this study. Values are expressed as absolute numbers and related percentages between brackets.

Table 1.

Baseline demographics and surgical details of the sample evaluated in this study. Values are expressed as absolute numbers and related percentages between brackets.

| Gender |

|

| Male |

7 (15.9%) |

| Female |

37 (84.1%) |

| Age (years) |

21.2 ± 5.0 |

| BMI |

22.6 ± 2.8 |

| Follow-up (months) |

27.0 ± 12.2 |

| Sport participation |

|

| Professional |

29 (65.9%) |

| Recreational |

15 (34.1%) |

| Graft choice |

|

| Hamstrings |

40 (90.9%) |

| BPTB |

3 (6.8%) |

| Quadriceps tendon |

1 (2.3%) |

| Type of surgical procedure |

| Isolated ACL reconstruction |

14 (31.8%) |

| ACL reconstruction + partial meniscectomy |

3 (6.8%) |

| ACL reconstruction + meniscus repair |

27 (61.4%) |

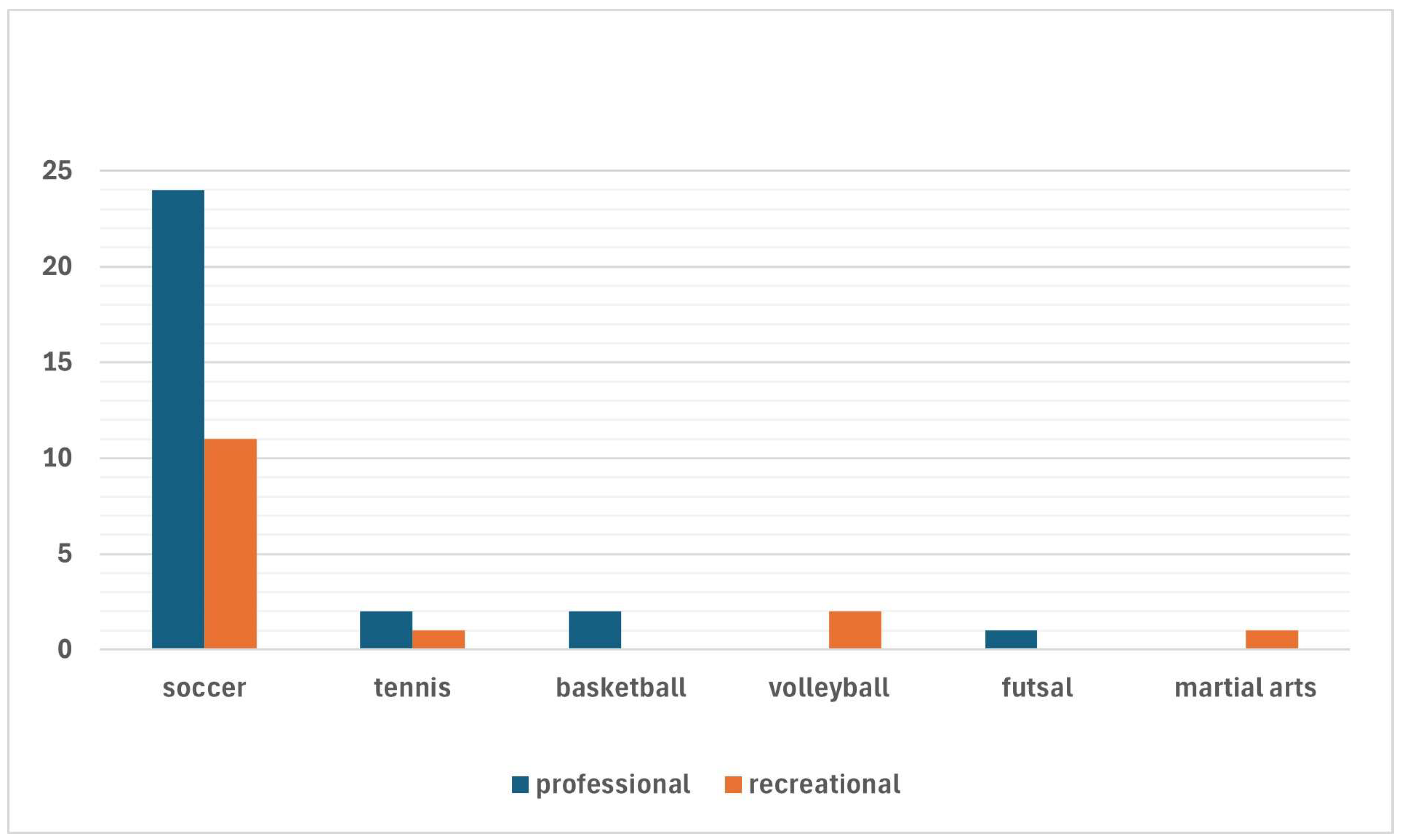

There were 29 (65.9%) professional athletes (including 24 soccer players, 2 tennis players, 2 basketball players and 1 futsal player) and 15 (34.1%) recreational athletes (11 soccer players, 2 volleyball players, 1 tennis player and 1 martial artist) (

Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Sports activities performed by the athletes included in the present study, differentiating professional athletes from recreational athletes.

Figure 1.

Sports activities performed by the athletes included in the present study, differentiating professional athletes from recreational athletes.

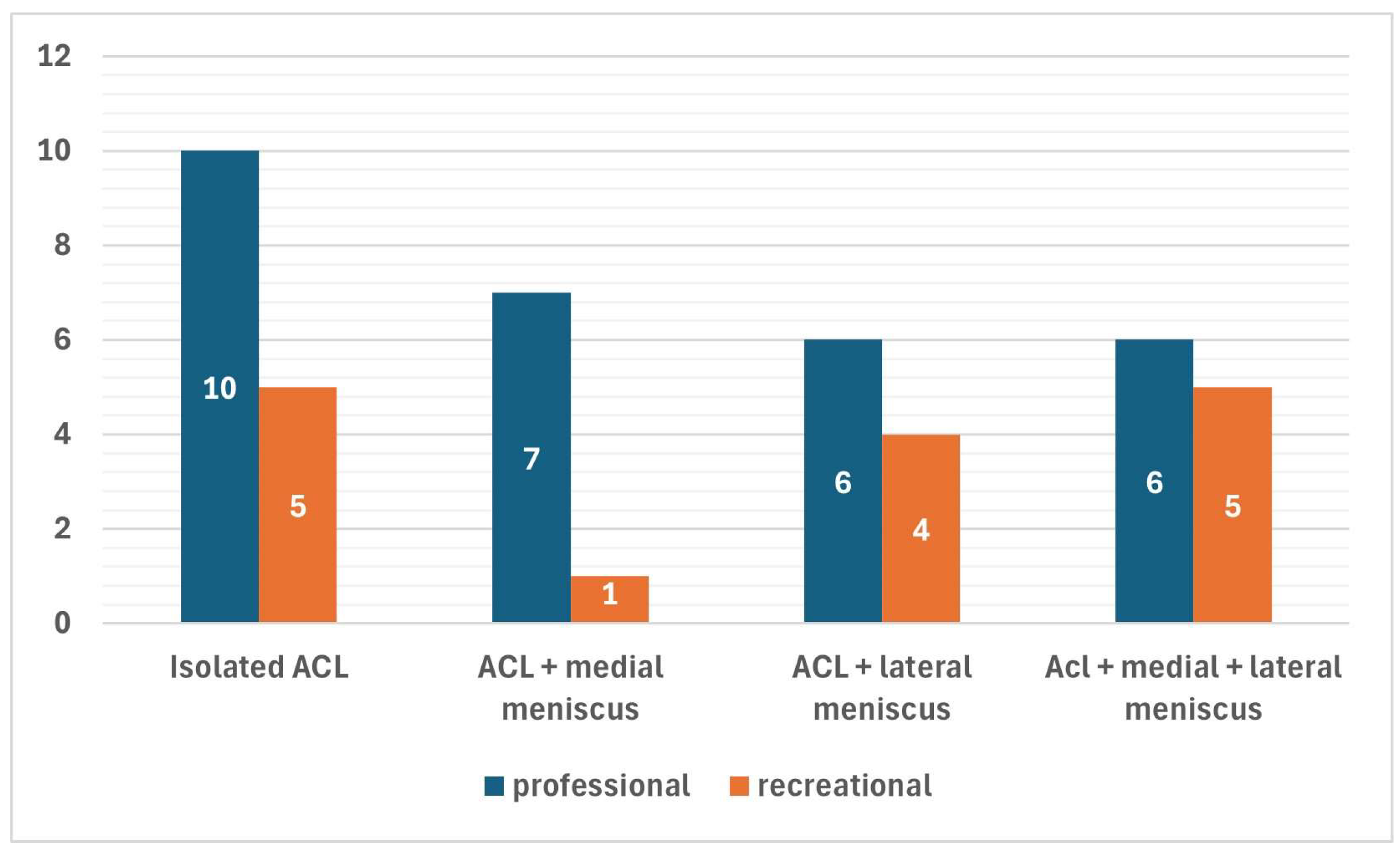

In most cases (40 patients, 90.9%), quadrupled hamstrings grafts were chosen for the ACL reconstruction, while BPTB and QT grafts were chosen in 3 (6.8%) patients and 1 (2.3%) case, respectively. A total of 42 concomitant menisci tears were found in 30 (68.2%) patients. Among the latter, 8 patients had concomitant medial meniscus tears (7 ramp lesions, 1 bucket-handle tear of the medial meniscus), 10 patients had concomitant lateral meniscus tears (4 posterior root tears, 4 longitudinal tears and 2 horizontal tears) and 12 patients had simultaneous medial and lateral meniscus tears (8 ramp lesions of the medial meniscus, 2 medial bucket-handle tears, 1 longitudinal medial meniscus tears and 1 radial medial meniscus tears associated with 8 posterior root tears of the lateral meniscus, 2 longitudinal tear of the lateral meniscus and 2 tears of the popliteomeniscal fasciculi). Although concomitant meniscus tears were less common among professional athletes (69.0%) than recreational athletes (73.3%), this difference was not statistically relevant (

Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Prevalence of concomitant meniscus tears within the two groups of professional and recreational athletes.

Figure 2.

Prevalence of concomitant meniscus tears within the two groups of professional and recreational athletes.

In only 3 out of 42 cases, partial meniscectomy was the treatment of choice, while all the remaining tears were treated using an all-inside technique or a transtibial pull-out technique (specifically for the posterior root tears of the lateral meniscus). A concomitant LET procedure was performed in 3 cases (6.8%).

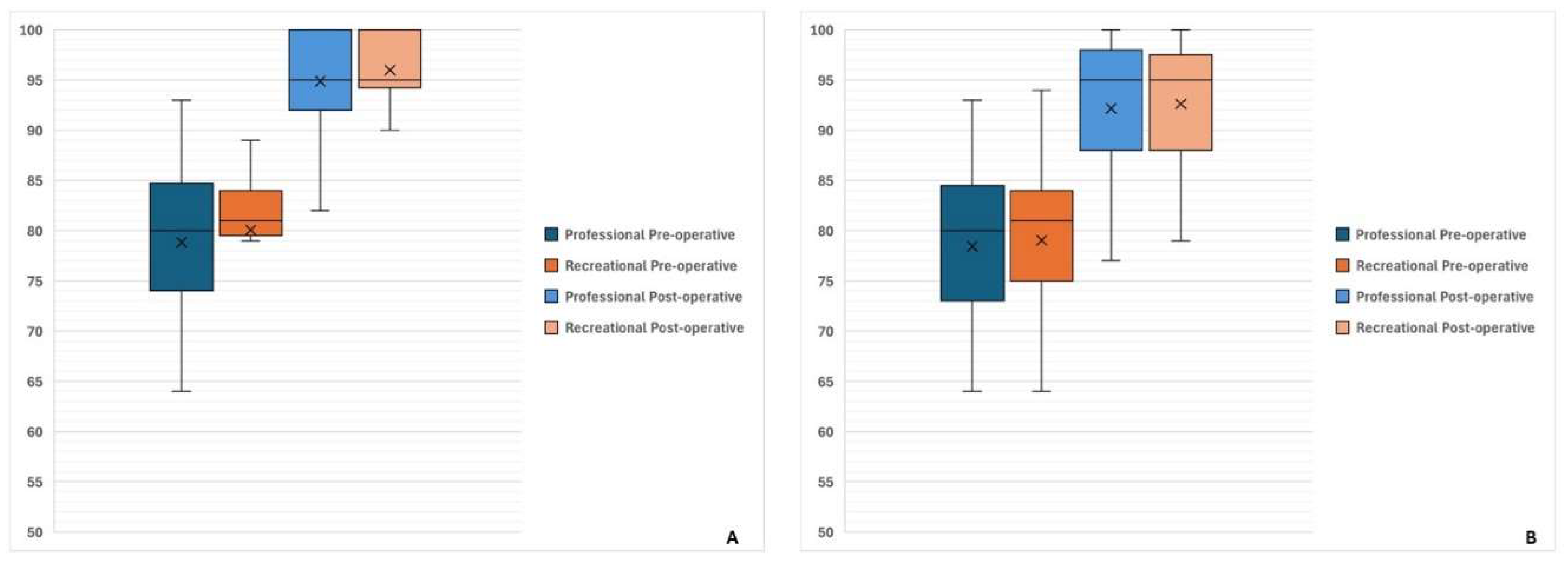

At evaluation at the last follow-up after a mean of 27.0 ± 12.2 months, a significant improvement was reported from baseline in terms of both Lysholm score (from 79.3 ± 8.6 at baseline to 95.4 ± 5.8 at last follow-up, p<0.0001) and IKDC subjective score (from 78.5 ± 8.6 at baseline to 91.2 ± 7.9 at last follow-up, p<0.0001) (

Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Functional scores at baseline and at last follow-up, with subgroup analysis between professional and recreational athletes. No significant intergroup difference was detected when comparing baseline outcomes as well as final results. Conversely, a statistically significant improvement was found at last follow-up in both groups. (a). Lysholm Score. (b). IKDC subjective score.

Figure 3.

Functional scores at baseline and at last follow-up, with subgroup analysis between professional and recreational athletes. No significant intergroup difference was detected when comparing baseline outcomes as well as final results. Conversely, a statistically significant improvement was found at last follow-up in both groups. (a). Lysholm Score. (b). IKDC subjective score.

After the rehabilitation protocol, 39 athletes (88.6%) returned to sports after a mean of 8.1 ± 1.4 months (range 5 – 12 months). At last follow-up, 33 athletes (75.0%) were still involved in sports activities, of whom 29 athletes (65.9%) returned to the same preinjury level. The return to sports rate was higher among professional athletes (82.8%) than among recreational athletes (60.0%), although this difference did not reach statistical significance (p=0.0984). Similarly, return to the same preinjury sport level was higher in professional athletes (79.3%) than in recreational athletes (40.0%), but in this case with a statistically significant intergroup difference (p=0.0091). In ten out of eleven cases of failed return to sport, athletes had undergone concomitant meniscus treatment during the index ACL reconstruction. Indeed, athletes with isolated ACL lesions had higher chances of returning to sport (92.9%) compared to athletes with concomitant menisci tears (66.7%) (p=0.0397). Reasons for failed return to sport included fear of graft rerupture in five cases, subsequent reoperation in two cases, subjective joint instability in two cases, knee swelling in one case and job reasons in last remaining case.

The objective assessment at last follow-up of the 29 athletes available showed good knee stability in most cases, with high-grade Lachman test in only two cases (6.9%) and high-grade pivot shift in only one case (3.4%). The same athlete had high-grade Lachman test and pivot-shift test and was counted among clinical failures. Similarly, KT-1000 side-to-side improved from 5.4 ± 1.4 mm at baseline to 1.6 ± 1.4 mm (p<0.0001). In 27 cases, the KT-1000 side-to-side difference was normal, in one case (3.4%) was higher than normal and in the one remaining (3.4%) was frankly abnormal. This last patient was the same with abnormal Lachman and Pivot-shift tests. Return to sports rates and clinical examination data at last follow-up are resumed in

Table 2.

Table 2.

Return to sports rates, clinical examination data, complications and reoperations rates.

Table 2.

Return to sports rates, clinical examination data, complications and reoperations rates.

| |

Professional |

Recreational |

P values |

| Return to play |

24 (82.8%) |

9 (60.0%) |

n.s. |

| Return to preinjury sport level |

23 (79.3%) |

6 (40.0%) |

0.0091† |

| Lachman test * |

| Low grade (grade 0-1) |

14 (87.4%) |

13 (100%) |

n.s. |

| High grade (grade 2-3) |

2 (12.6%) |

0 |

n.s. |

| Pivot shift test * |

| Low grade (grade 0-1) |

15 (93.8%) |

13 (100%) |

n.s. |

| High grade (grade 2-3) |

1 (6.2%) |

0 |

n.s. |

| KT-1000 side-to-side difference * |

| Normal (< 3 mm) |

14 (87.4%) |

13 (100%) |

n.s. |

| Higher than normal (≥ 3 mm and < 5 mm) |

1 (6.2%) |

0 |

n.s. |

| Frankly abnormal (≥ 5 mm) |

1 (6.2%) |

0 |

n.s. |

| Complications |

3 (10.3%) |

0 |

n.s. |

| ACL Failures |

2 (6.9%) |

0 |

n.s. |

| Contralateral ACL ruptures |

2 (6.9%) |

1 (6.7%) |

n.s. |

| Reoperations |

4 (13.8%) |

2 (13.3%) |

n.s. |

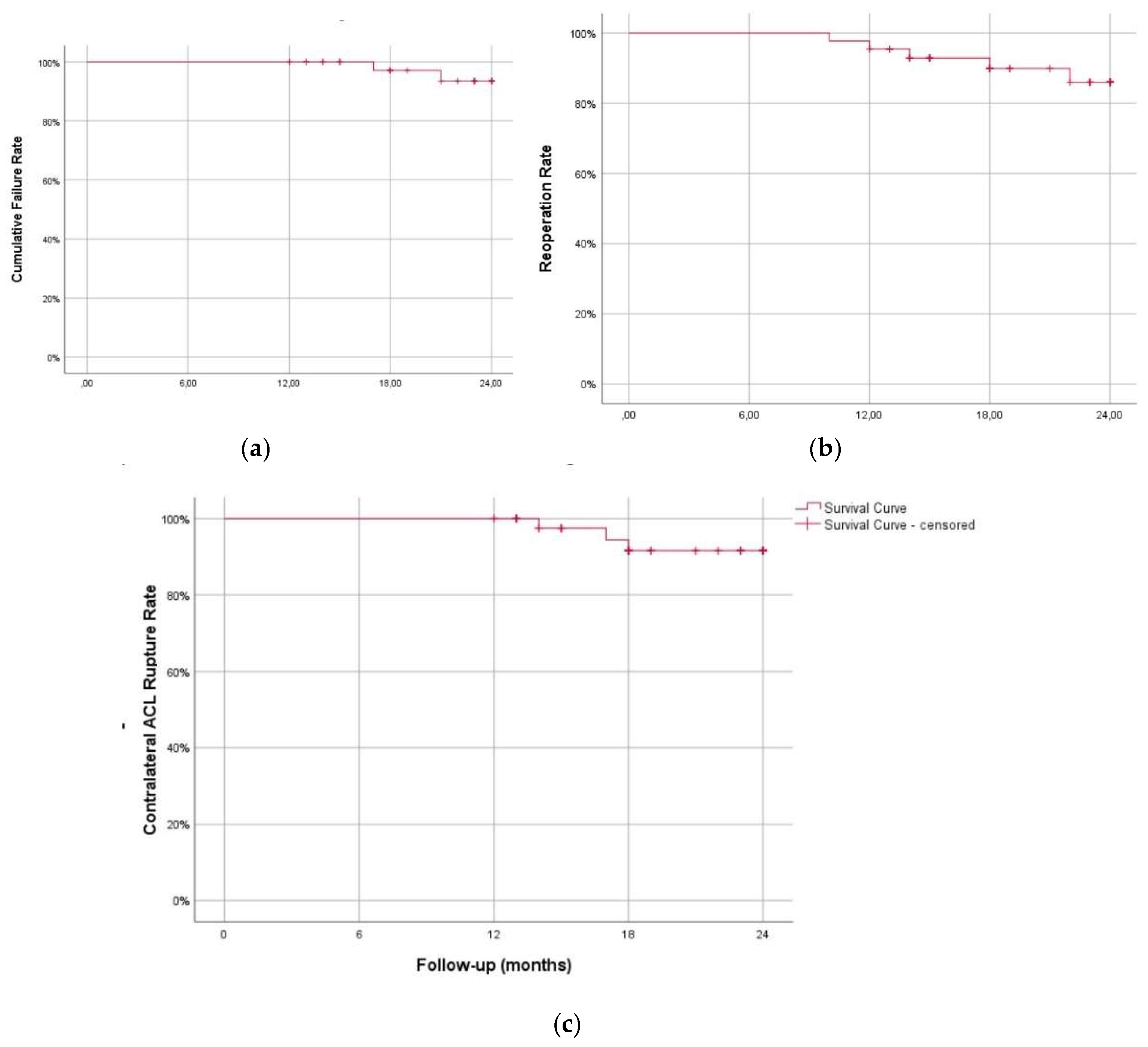

Failure rates and reoperation rates (with subgroup analysis of reoperation for contralateral ACL ruptures and reoperation for any other reason) are shown in (

Figure 4) and resumed in

Table 2.

Figure 4.

Kaplan-Meier survival curves with three different endpoints. (a). Cumulative ACL failure. (b). Contralateral ACL rupture. (c). Reoperation for any reason except for ACL graft revision and contralateral ACL rupture.

Figure 4.

Kaplan-Meier survival curves with three different endpoints. (a). Cumulative ACL failure. (b). Contralateral ACL rupture. (c). Reoperation for any reason except for ACL graft revision and contralateral ACL rupture.

Complications included one case of injury of infrapatellar branch of the saphenous nerve, one case of deep infection and one case of cyclops syndrome (these last two patients were reoperated for these reasons). The overall reoperations rate (except for ACL revision) was 20.5%. Four patients (two professional and two recreational athletes, 9.1%) were reoperated for failure of meniscal repairs (three patients for failure of ramp lesion repair, one patient for failure of both ramp lesion repair and posterior lateral meniscus root repair), three patients (two professional and one recreational athlete, 6.8%) because of contralateral ACL rupture, the last two professional athletes (4.6%) for deep infection and cyclops syndrome, respectively.

The composite failure rate was 4.6%. Failures included one professional soccer player with graft insufficiency at last follow-up (evidenced by high-grade Lachman and pivot-shift tests and abnormal arthrometric values) and one professional athlete with graft rerupture following a knee sprain during soccer match after 17 months from surgery.

4. Discussion

The primary findings of this study are that ACL reconstruction using the modified transtibial technique in a cohort of both professional and recreational athletes leads to satisfactory clinical outcomes and low rates of failure. Both functional scores adopted in this research showed significant improvements, exceeding in all cases the minimal clinically important difference described in the literature. [

19] Furthermore, only two cases of failure were found, corresponding to a rate of 4.6%. This failure rate is in line with data extracted from the literature, which estimated the pooled failure rate in athletes at little more than 5% (range 2.8% - 19.3%) [

20]. This finding needs to be read also in light of the young age of the sample (21.2 ± 5.0 years), which is widely recognized as an independent factor for the risk of failure of ACL reconstruction. [

2,

21] Furthermore, this failure rate is extracted from a case series of ACL reconstructions with a low incidence of LET procedures (6.8%). Several studies recommend additional LET in high risk-athletes similar to those evaluated in the present article to reduce the risk of graft failure or residual rotational instability. [

22,

23] On the other hand, the high incidence of concomitant meniscus tears and the high prevalence of meniscal repairs in this series should be considered when discussing the low rate of graft failures and abnormal joint laxity. It is well known that the medial and lateral menisci significantly contribute to knee stability, acting as secondary restraints for translational and rotatory tibial displacement [

2,

24]. Meniscus repair would seem to restore knee stability comparable to ACL-reconstructed knees with intact menisci [

25]. However, attempts to preserve meniscus function may result in higher risk of reoperation. Indeed, failed meniscus repairs represented the most common reason for reoperation in this series, accounting for two out of three cases of subsequent surgeries. Interestingly, the contralateral ACL injury rate was found to be higher than the ipsilateral graft rupture rate. Nonetheless, this data should not be unexpected, as it confirms a well-known finding in the literature. [

21,

26] Plausible explanations for this finding are young age [

21,

26], theoretical anatomical factors predisposing to ACL rupture [

2,

26], and the great stresses to which the ACL is subjected during high-demand sports activities. [

2,

21]

Another important topic for discussion is the return-to-sport rate in this series and the level of resumed sport. A trend was found in favor of professional athletes regarding return to sport, although this difference was not found statistically significant. Analyzing data more thoroughly, professional athletes were more likely to return to preinjury performances (79.3% vs. 40.0%, p=0.0091). Similar findings have already been reported in previous systematic reviews [

27,

28] and emphasize the prognostic role of the level of sports practiced. This discrepancy may be ascribed to differences in rehabilitation adherence, access to specialized care, and psychological readiness, factors that have been extensively documented in the literature. [

29] Additionally, fear of reinjury emerged as a major barrier to the return to sport, with five athletes explicitly citing it as the reason for not returning, supporting previous studies that indicate psychological factors play have a significant impact on to the return-to-sport rates. [

30,

31]

Interestingly, concomitant meniscus tears were a negative prognostic factor for returning to sport, reducing the chance to return to sport by approximately -25%. These data confirm the non-secondary role of the menisci in knee kinematics [

24] and should inspire surgeons specializing in the care of sports trauma during clinical practice. Meniscus tears and partial meniscus resection have been clearly documented as a risk factor for delayed return to sport and career shortening in athletes. [

2] Meniscus repair is supported by the authors of the present article, although a high risk of reoperation should be taken into consideration as the price to be paid.

The findings of this article must be balanced with the presence of certain limitations. The retrospective design introduces potential selection bias, even though data collection followed standardized protocols. Additionally, the mean follow-up period (27 months) can be adequate for evaluating short- to mid-term outcomes but does not provide insights into long-term graft survivorship. Furthermore, while anterior tibial translation was objectified using arthrometric devices, rotatory knee stability was assessed manually without the aid of advanced tools such as accelerometers. However, manual evaluation remains the gold standard in the literature and is included into the objective IKDC form [

17].

A further limitation is the lack of a control group using a different ACL reconstruction technique (e.g., independent drilling), which prevents direct comparisons in clinical outcomes. Future studies should incorporate prospective randomized designs comparing modified transtibial and independent drilling techniques to draw more robust conclusion. Lastly, while psychological readiness was identified as a significant predictor of return to sport, additional investigation is needed to determine the role of sport-specific rehabilitation protocols and psychological support in optimizing recovery.

5. Conclusions

This study confirms that ACL reconstruction using the modified transtibial technique is an effective procedure to restore knee stability and allow athletes to return to play. The technique provides significant functional improvements and a low failure rate, regardless of the level of sports activity practiced. The presence of concomitant meniscus injuries was found to be a determinant factor for returning to play. While these findings support the use of this technique, further research with longer follow-up periods and comparative analyses with other surgical approaches is necessary to refine patient selection criteria and optimize clinical outcomes.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.R., G.C.,F.P., G.T., M. S. and V.P.; methodology, G.C., C.D.N, M.S. and G.T.; software, G.C., M.A.M., M.G. and C.D.N; validation, A.R., G.C., M.S., G.T and V.P.; formal analysis, G.C., M.G. and C.D.N.; investigation, G.C. ,M.A.M, M.G. and C.D.N.; resources, A.R., G.C, M.G. C.D.N. and F.P.; data curation, A.R, G.C.,M.A.M, M.G. and C.D.N.; writing—original draft preparation, M.G., M.A.M., M.S., writing—review and editing, G.C., C.D.N., G.T.; visualization, A.R, G.C. and G.T.; supervision, A.R, G.C., G.T. and V.P.; project administration, M.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and accepted by the local ethics committee approval (no. 215/CEL in 10/21/2024) for studies involving humans.

Informed Consent Statement

All patients included in this study signed specific informed consent for data collection and elaboration in anonymous and/or aggregate form.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ACL |

Anterior cruciate ligament |

| BPTB |

bone-patellar tendon-bone |

| BMI |

Body mass index |

References

- Zhang L, Xu J, Luo Y, Guo L, Wang S. Anatomic femoral tunnel and satisfactory clinical outcomes achieved with the modified transtibial technique in anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Heliyon. 2024, 10, e35824. [CrossRef]

- Costa GG, Perelli S, Grassi A, Russo A, Zaffagnini S, Monllau JC. Minimizing the risk of graft failure after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction in athletes. A narrative review of the current evidence. J Exp Orthop. 2022, 9, 26. [CrossRef]

- Buerba RA, Zaffagnini S, Kuroda R, Musahl V. ACL reconstruction in the professional or elite athlete: state of the art. J ISAKOS. 2021, 6, 226–236. [CrossRef]

- Loucas M, Loucas R, D’Ambrosi R, Hantes ME. Clinical and Radiological Outcomes of Anteromedial Portal Versus Transtibial Technique in ACL Reconstruction: A Systematic Review. Orthop J Sports Med. 2021, 9, 23259671211024591. [CrossRef]

- Cuzzolin M, Previtali D, Delcogliano M, Filardo G, Candrian C, Grassi A. Independent Versus Transtibial Drilling in Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction: A Meta-analysis With Meta-regression. Orthop J Sports Med. 2021, 9, 23259671211015616. [CrossRef]

- Tashiro Y, Irarrázaval S, Osaki K, Iwamoto Y, Fu FH. Comparison of graft bending angle during knee motion after outside-in, trans-portal and trans-tibial anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2017, 25, 129–137. [CrossRef]

- Tashiro Y, Sundaram V, Thorhauer E, Gale T, Anderst W, Irrgang JJ, Fu FH, Tashman S. In Vivo Analysis of Dynamic Graft Bending Angle in Anterior Cruciate Ligament-Reconstructed Knees During Downward Running and Level Walking: Comparison of Flexible and Rigid Drills for Transportal Technique. Arthroscopy. 2017, 33, 1393–1402. [CrossRef]

- Glattke KE, Tummala SV, Chhabra A. Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction Recovery and Rehabilitation: A Systematic Review. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2022, 104, 739–754. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ardern CL, Webster KE, Taylor NF, Feller JA. Return to sport following anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis of the state of play. Br J Sports Med. 2011, 45, 596–606. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP; STROBE Initiative. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) Statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Int J Surg. 2014, 12, 1495–1499. [CrossRef]

- General Assembly of the World Medical Association. World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. J Am Coll Dent. 2014, 81, 14–18.

- Russo A, Costa GG, Zocco G, Blatti C, Cutaia R, Amico M, Fanzone G, Di Naro C. Anatomic Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction With Eccentric Femoral Footprint Positioning Using a Modified Transtibial Technique. Arthroscopy Techniques. 2025. [CrossRef]

- Ferretti A, Monaco E, Ponzo A, Basiglini L, Iorio R, Caperna L, Conteduca F. Combined Intra-articular and Extra-articular Reconstruction in Anterior Cruciate Ligament-Deficient Knee: 25 Years Later. Arthroscopy. 2016, 32, 2039–2047. [CrossRef]

- Tegner Y, Lysholm J. Rating systems in the evaluation of knee ligament injuries. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1985, 198, 43–49.

- Lysholm J, Gillquist J. Evaluation of knee ligament surgery results with special emphasis on use of a scoring scale. Am J Sports Med. 1982, 10, 150–154.

- Ebrahimzadeh MH, Makhmalbaf H, Golhasani-Keshtan F, Rabani S, Birjandinejad A. The International Knee Documentation Committee (IKDC) Subjective Short Form: a validity and reliability study. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2015, 23, 3163–3167. [CrossRef]

- Hefti F, Muller W, Jakob RP, Staubli HU. Evaluation of knee ligament injuries with the IKDC form. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 1993, 1, 226–234. [CrossRef]

- Pugh L, Mascarenhas R, Arneja S, Chin PY, Leith JM. Current concepts in instrumented knee-laxity testing. Am J Sports Med. 2009, 37, 199–210. [CrossRef]

- Migliorini F, Maffulli N, Jeyaraman M, Schäfer L, Rath B, Huber T. Minimal clinically important difference (MCID), patient-acceptable symptom state (PASS), and substantial clinical benefit (SCB) following surgical knee ligament reconstruction: a systematic review. Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg. 2025, 51, 32. [CrossRef]

- Lai CCH, Ardern CL, Feller JA, Webster KE. Eighty-three per cent of elite athletes return to preinjury sport after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a systematic review with meta-analysis of return to sport rates, graft rupture rates and performance outcomes. Br J Sports Med. 2018, 52, 128–138. [CrossRef]

- Wiggins AJ, Grandhi RK, Schneider DK, Stanfield D, Webster KE, Myer GD. Risk of Secondary Injury in Younger Athletes After Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Am J Sports Med. 2016, 44, 1861–76. [CrossRef]

- Kunze KN, Manzi J, Richardson M, White AE, Coladonato C, DePhillipo NN, LaPrade RF, Chahla J. Combined Anterolateral and Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction Improves Pivot Shift Compared With Isolated Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Arthroscopy. 2021, 37, 2677–2703. [CrossRef]

- Na BR, Kwak WK, Seo HY, Seon JK. Clinical Outcomes of Anterolateral Ligament Reconstruction or Lateral Extra-articular Tenodesis Combined With Primary ACL Reconstruction: A Systematic Review With Meta-analysis. Orthop J Sports Med. 2021, 9, 23259671211023099. [CrossRef]

- Simonetta R, Russo A, Palco M, Costa GG, Mariani PP. Meniscus tears treatment: The good, the bad and the ugly-patterns classification and practical guide. World J Orthop. 2023, 14, 171–185. [CrossRef]

- Hoshino Y, Hiroshima Y, Miyaji N, Nagai K, Araki D, Kanzaki N, Kakutani K, Matsushita T, Kuroda R. Unrepaired lateral meniscus tears lead to remaining pivot-shift in ACL-reconstructed knees. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2020, 28, 3504–3510. [CrossRef]

- Grassi A, Pizza N, Zambon Bertoja J, Macchiarola L, Lucidi GA, Dal Fabbro G, Zaffagnini S. Higher risk of contralateral anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) injury within 2 years after ACL reconstruction in under-18-year-old patients with steep tibial plateau slope. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2021, 29, 1690–1700. [CrossRef]

- Lai CCH, Ardern CL, Feller JA, Webster KE. Eighty-three per cent of elite athletes return to preinjury sport after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a systematic review with meta-analysis of return to sport rates, graft rupture rates and performance outcomes. Br J Sports Med. 2018, 52, 128–138. [CrossRef]

- Ardern CL, Taylor NF, Feller JA, Webster KE. Fifty-five per cent return to competitive sport following anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction surgery: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis including aspects of physical functioning and contextual factors. Br J Sports Med. 2014, 48, 1543–52. [CrossRef]

- Hamdan M, Haddad BI, Amireh S, Abdel Rahman AMA, Almajali H, Mesmar H, Naum C, Alqawasmi MS, Albandi AM, Alshrouf MA. Reasons Why Patients Do Not Return to Sport Post ACL Reconstruction: A Cross-Sectional Study. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2025, 18, 329–338. [CrossRef]

- Brinkman JC, Hassebrock JD, Tummala SV, Richman EH, Haglin JM, Makovicka JL, Poon SK, Economopoulos KJ. Association Between Autograft Choice and Psychological Readiness to Return to Sport After ACL Reconstruction. Orthop J Sports Med. 2025, 13, 23259671241291926. [CrossRef]

- Sonesson S, Kvist J, Ardern C, Österberg A, Silbernagel KG. Psychological factors are important to return to pre-injury sport activity after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: expect and motivate to satisfy. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2017, 25, 1375–1384. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).