1. Introduction

Plant pathogen inoculation plays a crucial role in plant disease research. Early inoculation experiments aim primarily at determining the pathogenicity of a given pathogen and establishing its role in causing disease. In later stages, such experiments have been widely employed in the research of pathology, such as the infection process, pathogenicity, genetic differentiation, differentiation and genetics of plant resistance to pathogens, and resistance breeding. There is a diverse range of plant pathogens, each requiring specific inoculation methods, with a greater extent of disease being the criterion for choosing the optimal inoculation method [

1]. The extent of disease in plant populations can be quantified by the incidence rate, degree of disease severity, and the disease severity index. Particularly, the disease severity index provides a comprehensive assessment of the incidence rate and the degree of disease severity index [

2]. Previous research has indicated that the choice of suitable inoculation method, timing, and site has a significant impact on the inoculation outcomes [

3,

4].

Diseases in branch and trunk have been a research hotspot in tree pathology, and a range of distinctive techniques have been developed for pathogen inoculation during the study process. For instance, Li et al. (2019) inoculated

Botryosphaeria dothidea isolate CZA and

V. sordida isolate CZC with the branches of

Populus beijingensis clones via punching to study the molecular mechanisms of plant responses to pathogen infection [

5]. The study results showed significant up-regulation of the majority of disease-resistant genes in poplar. In the study by Bessho et al. (2004),

V. ceratosperma was inoculated with isolated mature branches and twigs of apple trees using the burning technique, and branches exhibited higher resistance to the pathogen compared to twigs, suggesting a positive correlation between branch resistance and tree age [

6]. By inoculating

Dothiorella gregaria (the once used anamorph synonym of

B. dothidea) with two-year-old

P. simonii Carr × nigra var. italica using intact skin, needles, wounded skin, and burning techniques, Yang et al. (1985) discovered that burning inoculation was associated with a higher incidence of diseases in branch and trunk and faster lesion expansion [

7]. Ghimire et al. (2019), using the toothpick and trunk wounding techniques to inoculate

Diaporthe spp. with soybeans, noted that the length of lesions induced by toothpick inoculation and disease severity index significantly surpassed those in the trunk wounding inoculation group [

8]. Collectively, punching, burning, and toothpick inoculation are common techniques for the inoculation of diseases in branch and trunk. While the results of many studies using one-year-old seedlings or isolated trunks for inoculation may fail to represent the disease resistance of perennial plants.

Populus alba var. pyramidalis is an economically important tree and serves as a model plant in tree biology research [

9]. It is widely distributed in the deserts and arid regions of northwest China.

P. alba var.

pyramidalis have been extensively used for timber production and ecological conservation, exhibiting significant economic value, which are attributed to their characteristics of fast growth, high biomass yield, and remarkable tolerance to stressors such as drought and salt [

10,

11]. Therefore,

P. alba var.

pyramidalis was selected as an object of inoculation in our experiment.

V. sordida is a significant plant pathogen that can cause

Cytospora canker (also known as

Valsa canker) involving the branches and trunks of trees. This pathogen is widely distributed in the northern regions of China [

12,

13], posing a severe threat to poplars. In fast-growing poplar plantations, the incidence of

Valsa canker ranges from 20% to 40%, reaching over 90% in some cases [

14,

15,

16], causing substantial economic losses to commercial forestry. Against this background,

V. sordida was investigated in this experiment.

Punching and burning techniques are most frequently used in studies on the pathogenicity and inoculation of

V. sordida [

5,

17]. In contrast, the aforementioned toothpick inoculation has not been utilized in inoculation experiments with

V. sordida, and there is a lack of systematic comparison of these three inoculation methods for

P. alba var. pyramidalis. In this study, punching, burning, and toothpick inoculation were employed to wound six-year-old

P. alba var.

pyramidalis to compare the inoculation outcomes of these methods by analyzing the incidence of

Valsa canker and disease extent caused by

V. sordida infection. Additionally, this study also elaborated the effects of intra- and inter-row spacing (stand density), inoculation position, and plant age, factors closely associated with the occurrence and development of diseases, on the inoculation outcomes, aiming to identify the optimal inoculation method and determine the ideal inoculation position as well as intra- and inter-row spacing when using this optimal method. The present study is expected to provide technical support for artificial inoculation research on poplar pathogens and serve as a theoretical basis for the inoculation of other diseases in branch and trunk.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plants and Fungi

The objects of inoculation were nine six-year-old P. alba var. pyramidalis with a diameter at breast height of 18.18 ± 1.13 cm, exhibiting robust growth and free from plant diseases and insect pests, with the intra- and inter-row spacing of 0.8 m × 0.8 m in six plants and 1.6 m × 1.6 m in the remaining trees, respectively. Additionally, 45 two-year-old P. alba var. pyramidalis with a ground diameter of 13.59 ± 1.31 mm, robust growth and absence of diseases and pests, were included as supplementary experimental materials. The six-year-old P. alba var. pyramidalis were cultivated at the experimental site of the Plant Physiology Laboratory, Institute of Ecological Conservation and Restoration, Chinese Academy of Forestry. The two-year-old P. alba var. pyramidalis cuttings were cultivated in plastic pots containing a mixed substrate (peat soil: perlite = 6:1) and grown at the same experimental site. In this study, the V. sordida strain CZC and the B. dothidea strain CZA were used as the primary and the supplementary fungal materials, respectively. After activation, these strains were cultured on potato dextrose agar (PDA) at pH 6.0 and incubated in dark at 28 °C for 7 days.

The six- and two-year-old P. alba var. pyramidalis were cultivated in the same experimental environment, and the fungi were activated from the identical strains. Therefore, the disease resistance of poplars and the pathogenicity of the fungi remained consistent throughout the study.

2.2. Punching, Burning, and Toothpick Inoculation Experiments on Six-Year-Old P. alba var. Pyramidalis

2.2.1. Punching Inoculation

One day before inoculation, the poplar trunk was cleaned with water, and the bark surface was sterilized with 75% alcohol. The trunk was air-dried before the inoculation experiment. The trunk was divided into the top and the bottom, with the upper located 80 cm above the ground and the lower 10 cm above the ground, leaving a 10 cm blank in the middle. Using a sterilized 5-mm puncher, circle-shaped holes were made in the top and the bottom of the trunk with a spacing of approximately 5 cm between holes. Each area had 15 inoculation holes. Three poplars were inoculated in total, including two with intra- and inter-row spacing of 0.8 m × 0.8 m and one with intra- and inter-row spacing of 1.6 m × 1.6 m. After punching, the periderm and phloem were removed for the inoculation of equally sized fungal clumps. The inoculation sites were covered with plastic wrap for moisture retention and prevention of contamination. Simultaneously, holes were made 5 cm beside the inoculation sites of V. sordida to inoculate agar blocks as controls, with the top and the bottom containing 5 holes, respectively. The plastic wrap was removed at 1 week post-inoculation. The lesion development at the inoculation sites was observed at days 10, 20, 30, 40, and 50 post-inoculation. Disease markers were measured to analyze the impact of different inoculation sites as well as intra- and inter-row spacing on the development of V. sordida infection.

2.2.2. Burning Inoculation

Similarly, the inoculation experiment was started after cleaning of poplar trunk with water, sterilization of the bark surface with 75% alcohol, and air-drying of the trunk one day before inoculation. Using a heated 5 mm iron nail, the trunk was scorched until the bark turned brown. After cooling, the trunk was immediately inoculated with V. sordida clumps. Fifteen burnt sites were inoculated on the top and the bottom of the trunk, while additional five agar blocks were inoculated respectively in the top and the bottom as controls. The inoculation sites were covered with plastic wrap for moisture retention. Three poplars were inoculated in total, including two with intra- and inter-row spacing of 0.8 m × 0.8 m and one with intra- and inter-row spacing of 1.6 m × 1.6 m. At 1 week post-inoculation, the plastic wrap was removed. Lesion development at the inoculation sites was observed at days 10, 20, 30, 40, and 50 post-inoculation. Disease markers were measured to analyze the impact of different inoculation sites and intra- and inter-row spacing on the development of V. sordida infection.

2.2.3. Toothpick Inoculation

Similarly, the inoculation experiment was initiated after cleaning of poplar trunk with water, sterilization of the bark surface with 75% alcohol, and air-drying of the trunk one day before inoculation. A total of 15–20 sterilized toothpicks (length: 6.5 cm; diameter: 0.2 cm; Guanghui, Harbin, China) were arranged in parallel on a 9 cm PDA solid plate. CZC was inoculated onto the toothpicks, and the plate was incubated in dark at 25 °C for 7 days until the toothpicks were completely covered by fungal mycelia. Before inoculation, holes were drilled 0.8–1.0 cm vertically into the trunk surface using a 0.15 cm drill bit. Following that, the fungus-inoculated toothpicks were quickly inserted into the holes. Fifteen fungus-inoculated toothpicks were placed in the top and the bottom of the trunk, respectively, while additional five sterile toothpicks were inserted as controls in the top and the bottom, respectively. The inoculation sites were covered with plastic wrap for moisture retention. Three poplars were inoculated in total, including two with intra- and inter-row spacing of 0.8 m × 0.8 m and one with intra- and inter-row spacing of 1.6 m × 1.6 m. At 1 week post-inoculation, the plastic wrap was removed. The lesion development at the inoculation sites was observed at days 10, 20, 30, 40, and 50 post-inoculation. Disease markers were measured to analyze the impact of different inoculation sites and intra- and inter-row spacing on the development of V. sordida infection.

2.3. Burning Inoculation Experiment on Two-Year-Old P. alba var. Pyramidalis

The burning inoculation was employed to inoculate 15 two-year-old P. alba var. pyramidalis with the pathogenic fungi CZA and CZC, each containing 8 inoculation sites, with agar blocks serving as controls. The development of lesions was observed, and disease markers were measured at 50 days post-inoculation. The statistical analysis and data processing for these marker measurements were consistent with those applied in the inoculation experiment on the six-year-old P. alba var. pyramidalis.

2.4. Disease Markers and Statistical Methods

2.4.1. Statistical Analysis and Calculation of Disease Incidence, Disease Severity Index, and Lesion Area at Each Inoculation Site

In the experiment, each

P. alba var.

pyramidalis with spacings of 0.8 m × 0.8 m and 1.6 m × 1.6 m was inoculated at 30 sites, with 15 sites on both the top and the bottom of the tree. Each inoculation method was applied to three trees, totaling 90 inoculation sites. Disease incidence was calculated at 10, 20, 30, 40, and 50 days post-inoculation. The formula for calculating disease incidence at each inoculation site under each method is as follows (1) [

2]. Preliminary results from early inoculation experiments revealed that canker lesions formed by

V. sordida on the trunk of

P. alba var.

pyramidalis showed elliptical or nearly elliptical appearances. Therefore, the size of the lesion area was estimated using the formula for the area of an ellipse as follows (2) [

18]. Additionally, due to variations in the necrotic area at control inoculation sites in the punching, burning, and toothpick inoculation experiments (0.60 ± 0.074 cm

2, 0.85 ± 0.14 cm

2, and 0.31 ± 0.088 cm

2, respectively), the relative area of lesion was adopted as a quantity standard, which is calculated as follows (3). The symptoms of lesions were taken into consideration to determine the presence or absence of disease, and the disease severity index was calculated using the formula (4) [

2]:

Disease incidence was calculated using Formula (1):

The area of a lesion was calculated using Formula (2):

where “a” represents the length of the lesion; “b” stands for the width of the lesion.

The relative area of each lesion was calculated using Formula (3):

The criteria for disease severity index grading are presented as follows:

Table 1.

Disease Severity Index grading1.

Table 1.

Disease Severity Index grading1.

| Grade |

Lesion area in the treatment group/Area of inoculation sites in the control group (Srelative area) |

| 0 |

No infection in the treatment group (Srelative area ≤ 1.25) |

| 1 |

The lesion area in the treatment group is 1.25 to 1.75 times that of the control inoculation sites (1.25 < Srelative area ≤ 1.75) |

| 2 |

The lesion area in the treatment group is 1.75 to 2.25 times that of control inoculation sites (1.75 < Srelative area ≤ 2.25) |

| 3 |

The lesion area in the treatment group is 2.25 to 2.75 times that of the control inoculation sites (2.25 < Srelative area ≤ 2.75) |

| 4 |

The lesion area in the treatment group is over 2.75 times that of the control inoculation sites (Srelative area> 2.75) |

The disease severity index was calculated using Formula (4):

2.4.2. Observation and Measurement of Lesion Morphology and Spore Microstructure at Inoculation Sites

At 10, 20, 30, 40, and 50 days post-inoculation, photographs were taken using a Canon 200D camera to document the lesion status and the quantity of pycnidia at each inoculation site. As black pycnidia grew on the lesions during inoculation, part of the structure was carefully collected using an inoculation needle and placed in a rice-paper plant, which was vertically dissected with a scalpel. Subsequently, the pycnidial structure was observed and photographed under an optical microscope (OLYMPUS BX51TRF).

2.4.3. Observation and Statistical Analysis of Wounded Area of Xylem at Inoculation Sites

At 50 days post-inoculation, the rotten layer of the affected bark was removed using a scalpel to expose the xylem (white). Photographs were taken using a camera to observe the transversal section of the lesion. The length of both longitudinal and transversal extensions of each lesion was measured with a ruler. Subsequently, a vertical incision was made perpendicular to the lesion surface, and photographs were taken to observe the longitudinal section of the lesion. The depth of the lesion-induced wound to the xylem was measured using a ruler. As the shape of the wounded xylem resembled an ellipse, the calculation for the wounded area of xylem followed the ellipse area formula [see Formula (2) in Section 1.3.1].

2.5. Data Processing and Statistical Analysis

Chi-square tests were conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics 22. Mean of the relative area of lesions was calculated and subjected to analysis of variance (ANOVA) using, with corresponding graphs plotted. Differences between the treatment group and the control group were assessed using independent sample t-tests, with a significance level set at p < 0.05 and a high significance level at p < 0.01. All data were presented as “mean ± standard deviation (m ± sd)” or standard error of mean (SEM).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.Z.; methodology, J.Z., L.P., and W.S.; software, W.S. and L.P.; validation, W.S., L.P. and Y.F.; formal analysis, W.S., Y.S., and Y.Z.; investigation, W.S., and Y.S.; resources, H.L.; data curation, W.S.; writing-original draft preparation, W.S.; writing-review and editing, W.S., L.P. and J.Z.; visualization, W.S.; supervision, X.S.; project administration, J.Z.; funding acquisition, J.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Figure 1.

Cross-sectional diagrams of lesion formation after punching, burning, and toothpick inoculation. Note: A–E, punching inoculation of V. sordida; F–J, burning inoculation of V. sordida; K–O, toothpick inoculation of V. sordida. A, F, and K, controls inoculated with water-agar blocks; B–D, G–I, and L–N, development of lesions at 10, 20, and 40 days post-inoculation; E, J, O, cross-sectional diagrams of lesions at 50 days post-inoculation with punching, burning, and toothpick techniques, respectively.

Figure 1.

Cross-sectional diagrams of lesion formation after punching, burning, and toothpick inoculation. Note: A–E, punching inoculation of V. sordida; F–J, burning inoculation of V. sordida; K–O, toothpick inoculation of V. sordida. A, F, and K, controls inoculated with water-agar blocks; B–D, G–I, and L–N, development of lesions at 10, 20, and 40 days post-inoculation; E, J, O, cross-sectional diagrams of lesions at 50 days post-inoculation with punching, burning, and toothpick techniques, respectively.

Figure 2.

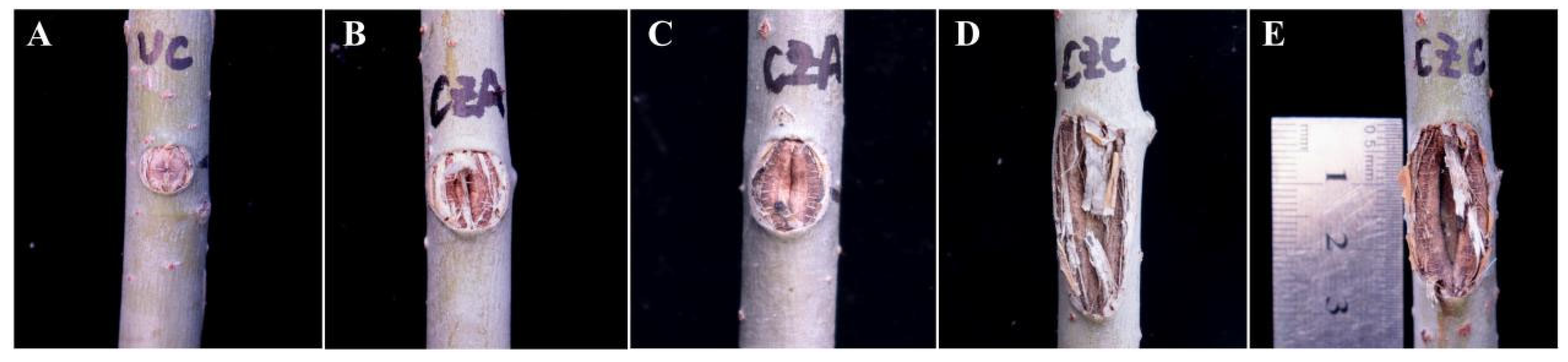

Cross-sectional diagrams of the inoculation sites after punching inoculation. Note: A, cross-sectional diagram of the inoculation sites in the control group; B and C, transversal cross-sectional diagrams of the lesions in the treatment group; D and E, longitudinal cross-sectional diagrams of the lesions in the treatment group.

Figure 2.

Cross-sectional diagrams of the inoculation sites after punching inoculation. Note: A, cross-sectional diagram of the inoculation sites in the control group; B and C, transversal cross-sectional diagrams of the lesions in the treatment group; D and E, longitudinal cross-sectional diagrams of the lesions in the treatment group.

Figure 3.

Cross-sectional diagrams of inoculation sites with toothpick inoculation. Note: A, cross-sectional diagram of the inoculation sites in the control group; B–D, transversal cross-sectional diagrams of the lesions in the treatment group.

Figure 3.

Cross-sectional diagrams of inoculation sites with toothpick inoculation. Note: A, cross-sectional diagram of the inoculation sites in the control group; B–D, transversal cross-sectional diagrams of the lesions in the treatment group.

Figure 4.

Cross-sectional diagrams of inoculation sites with burning inoculation. Note: A, cross-sectional diagram of the inoculation sites in the control group; B–D, transversal cross-sectional diagrams of the lesions in the treatment group.

Figure 4.

Cross-sectional diagrams of inoculation sites with burning inoculation. Note: A, cross-sectional diagram of the inoculation sites in the control group; B–D, transversal cross-sectional diagrams of the lesions in the treatment group.

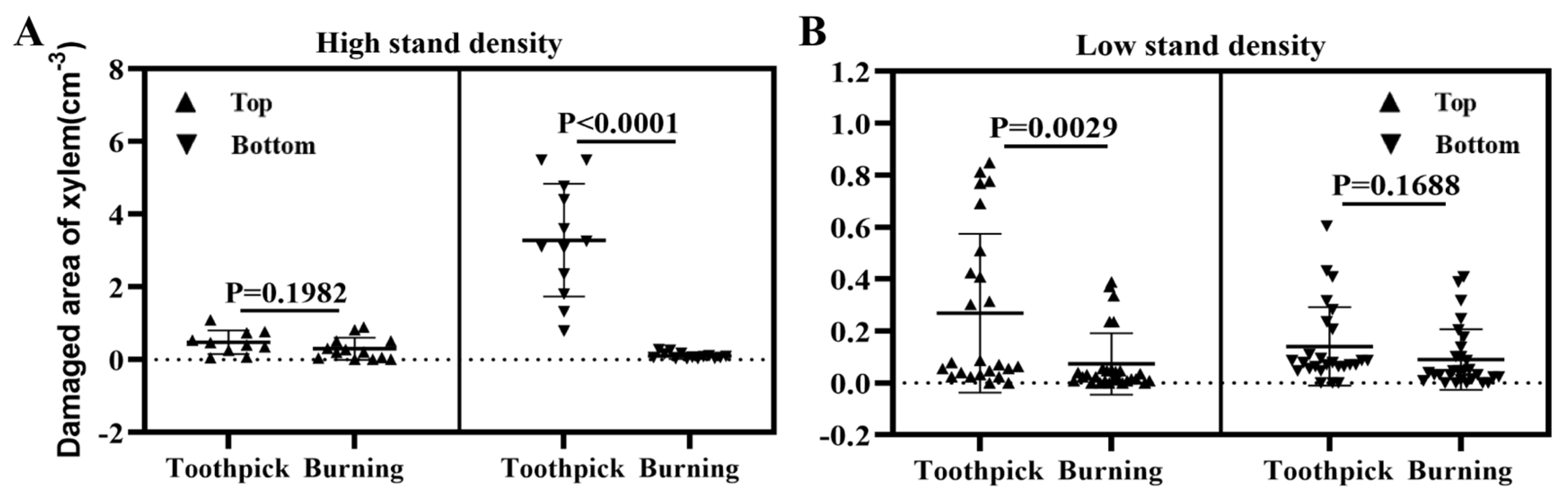

Figure 5.

Area of the wounded xylem at the inoculation sites after toothpick and burning inoculations. Note: A, inoculation on P. alba var. pyramidalis with low intra- and inter-row spacing; top (left), and bottom (right); B, inoculation on P. alba var. pyramidalis with high intra- and inter-row spacing; top (left), and bottom (right).

Figure 5.

Area of the wounded xylem at the inoculation sites after toothpick and burning inoculations. Note: A, inoculation on P. alba var. pyramidalis with low intra- and inter-row spacing; top (left), and bottom (right); B, inoculation on P. alba var. pyramidalis with high intra- and inter-row spacing; top (left), and bottom (right).

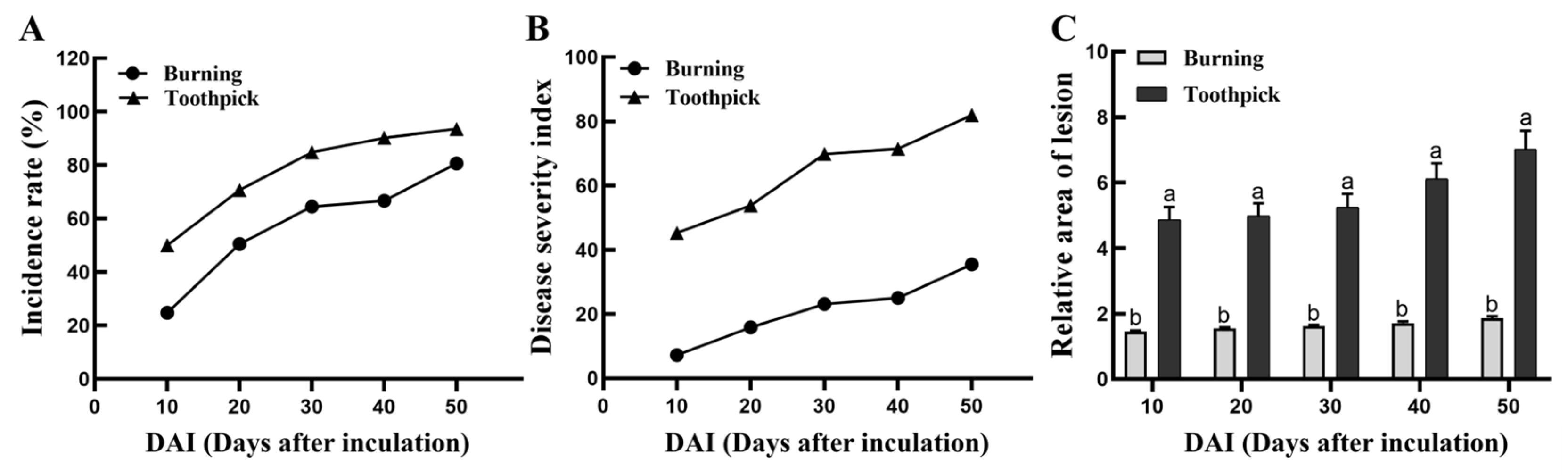

Figure 6.

Changes in disease incidence, disease severity index, and relative area of lesion at the inoculation sites in the burning and toothpick inoculation groups.

Figure 6.

Changes in disease incidence, disease severity index, and relative area of lesion at the inoculation sites in the burning and toothpick inoculation groups.

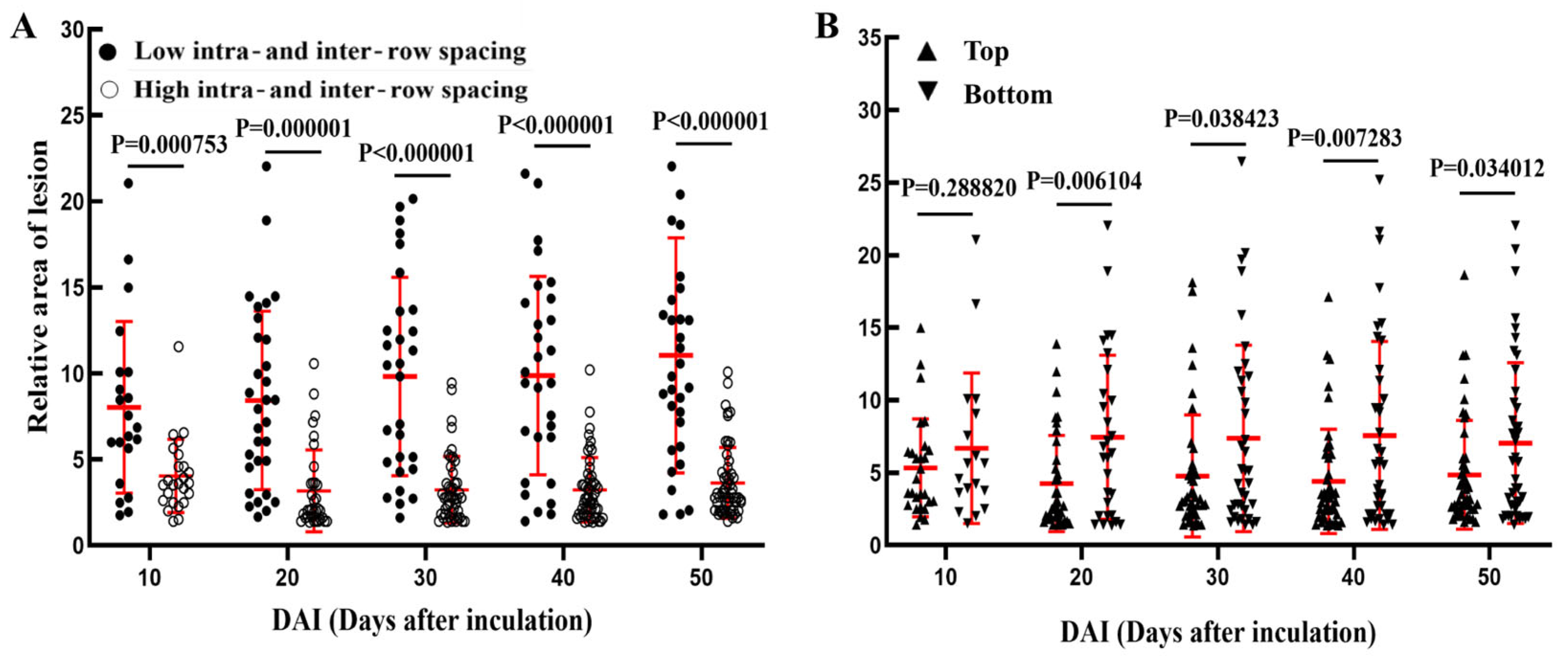

Figure 7.

Summary of relative areas of lesion at different stand densities and inoculation positions.

Figure 7.

Summary of relative areas of lesion at different stand densities and inoculation positions.

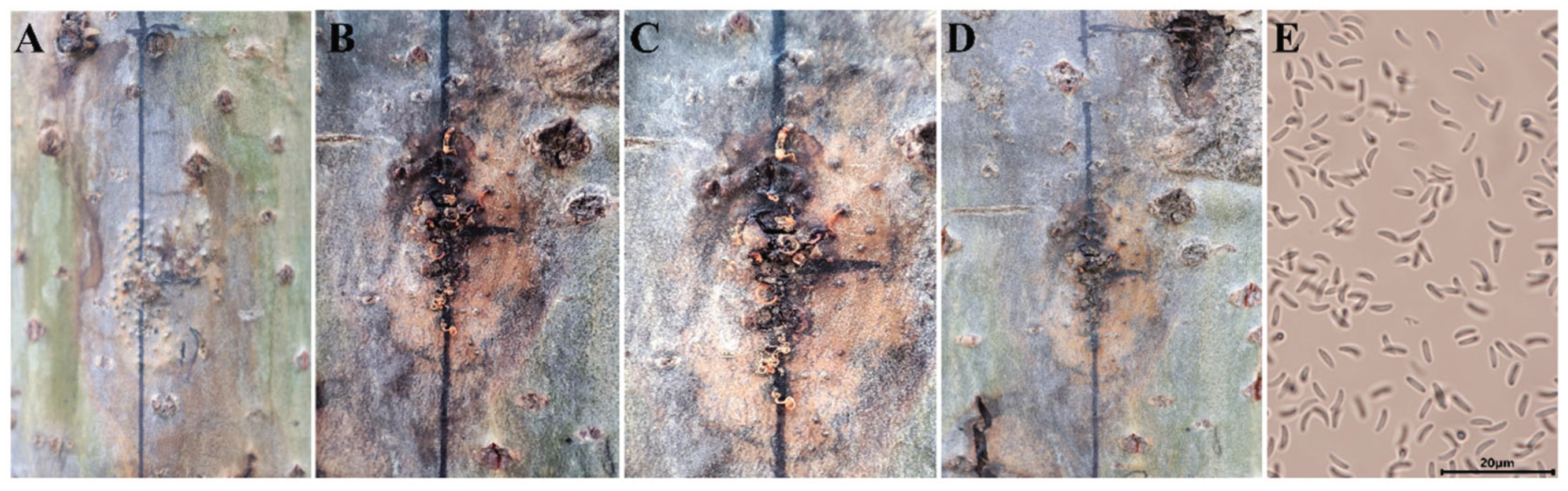

Figure 8.

Process of changes in the production of pycnidia induced by toothpick inoculation. Note: A–D, Production of pycnidia by the lesions; E, conidia under microscopy.

Figure 8.

Process of changes in the production of pycnidia induced by toothpick inoculation. Note: A–D, Production of pycnidia by the lesions; E, conidia under microscopy.

Figure 9.

Changes in the inoculation sites on the trunks of two-year-old P. alba var. pyramidalis after burning inoculation with CZA and CZC. Note: A, inoculation sites in the control group; B and C, inoculation sites in the CZA-treated group; D and E, inoculation sites in the CZC-treated group.

Figure 9.

Changes in the inoculation sites on the trunks of two-year-old P. alba var. pyramidalis after burning inoculation with CZA and CZC. Note: A, inoculation sites in the control group; B and C, inoculation sites in the CZA-treated group; D and E, inoculation sites in the CZC-treated group.

Table 2.

Summary of CZA- and CZC-induced lesions in two-year-old P. alba var. pyramidalis after burning inoculation.

Table 2.

Summary of CZA- and CZC-induced lesions in two-year-old P. alba var. pyramidalis after burning inoculation.

| |

Treatment |

Incidence rate, % |

Disease severity index |

Relative lesion area |

| 1 |

CZA |

18.75 |

30.08 |

1.65±0.40 |

| 2 |

CZC |

100 |

87.50 |

3.58±1.38 **** |