Submitted:

31 October 2024

Posted:

01 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Region and Data Sources

2.2. ICP-Forests Monitoring Data

2.3. Assessing Biotic Factors of Ulmus sp. Damage, Tree Death or Recovery, in 2023–2024

2.4. Data Processing

3. Results

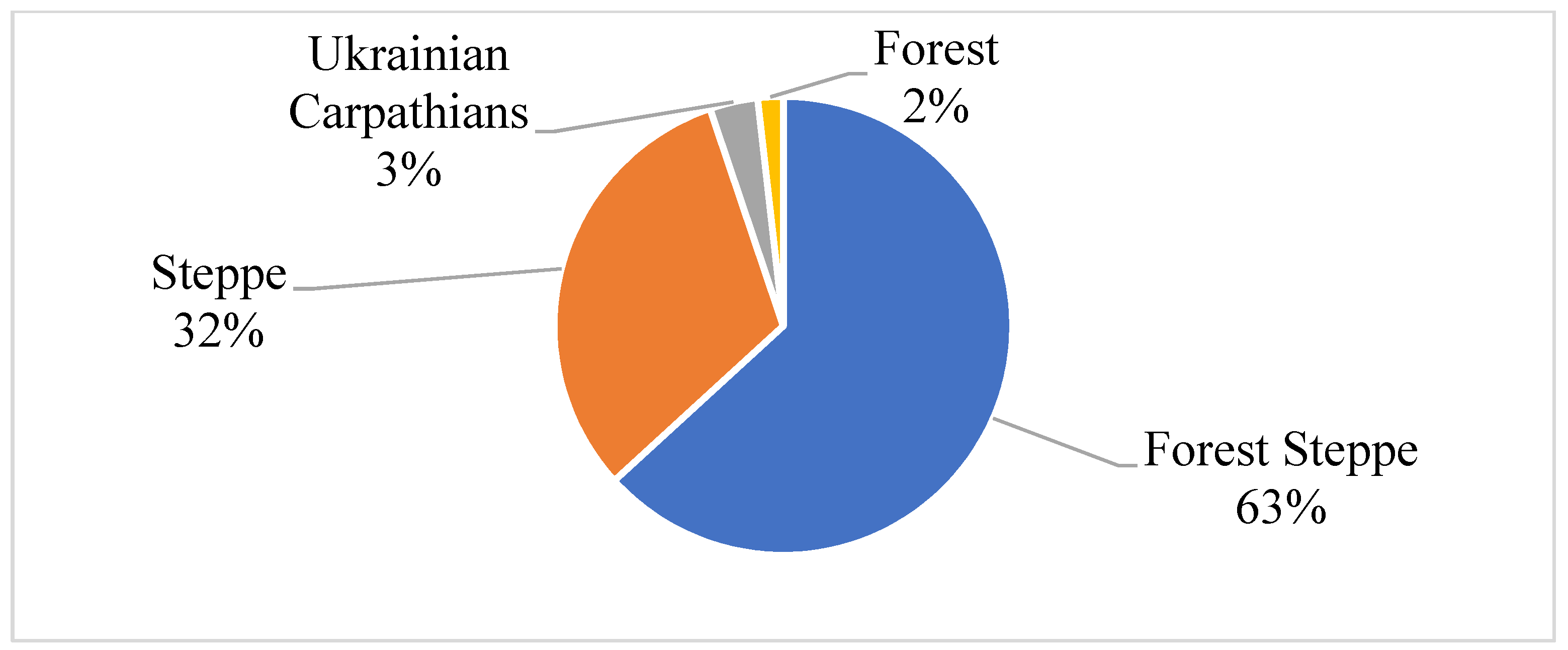

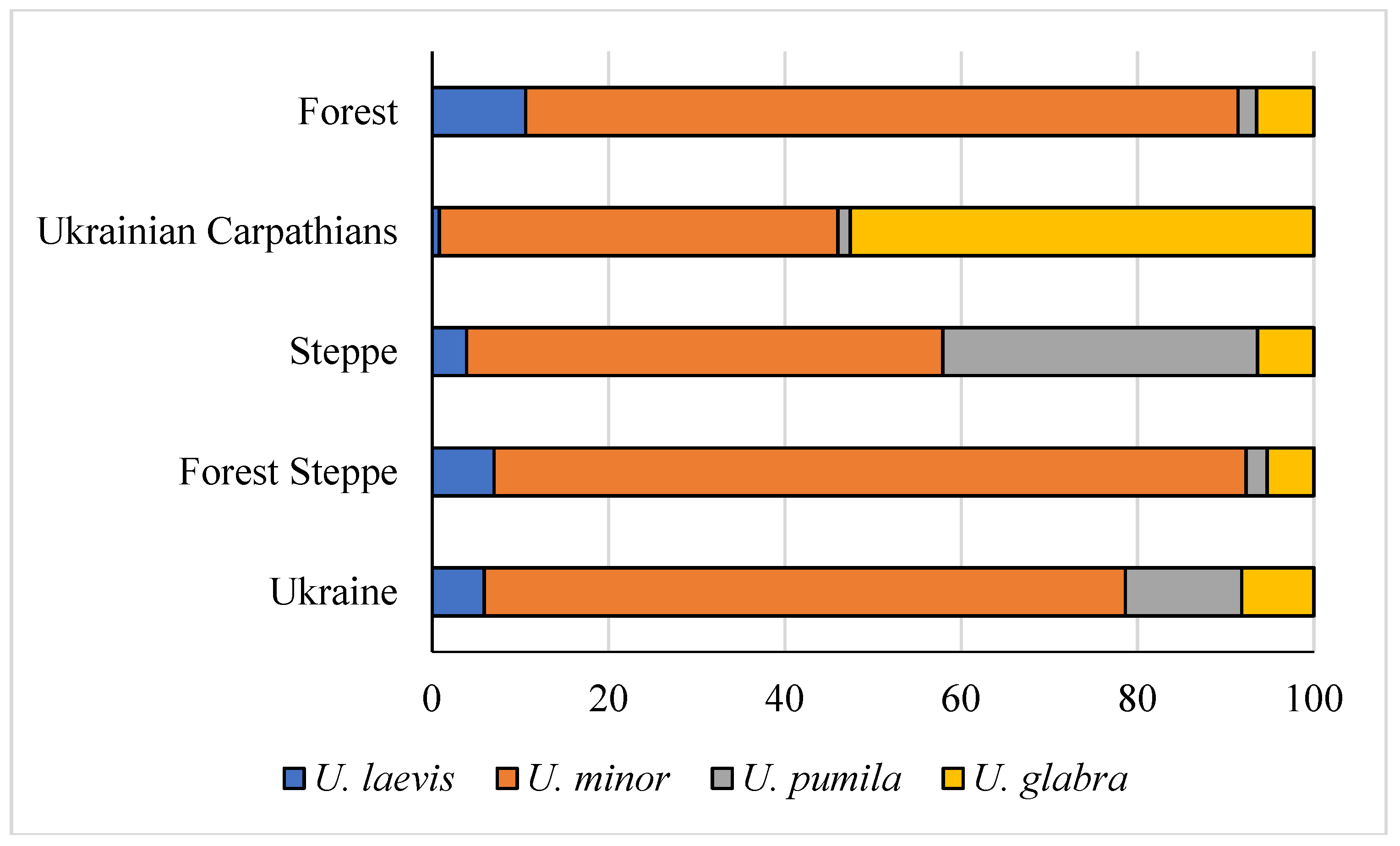

3.1. Ulmus sp. in the Forests Subordinated to the State Specialized Forest Enterprise «Forests of Ukraine»

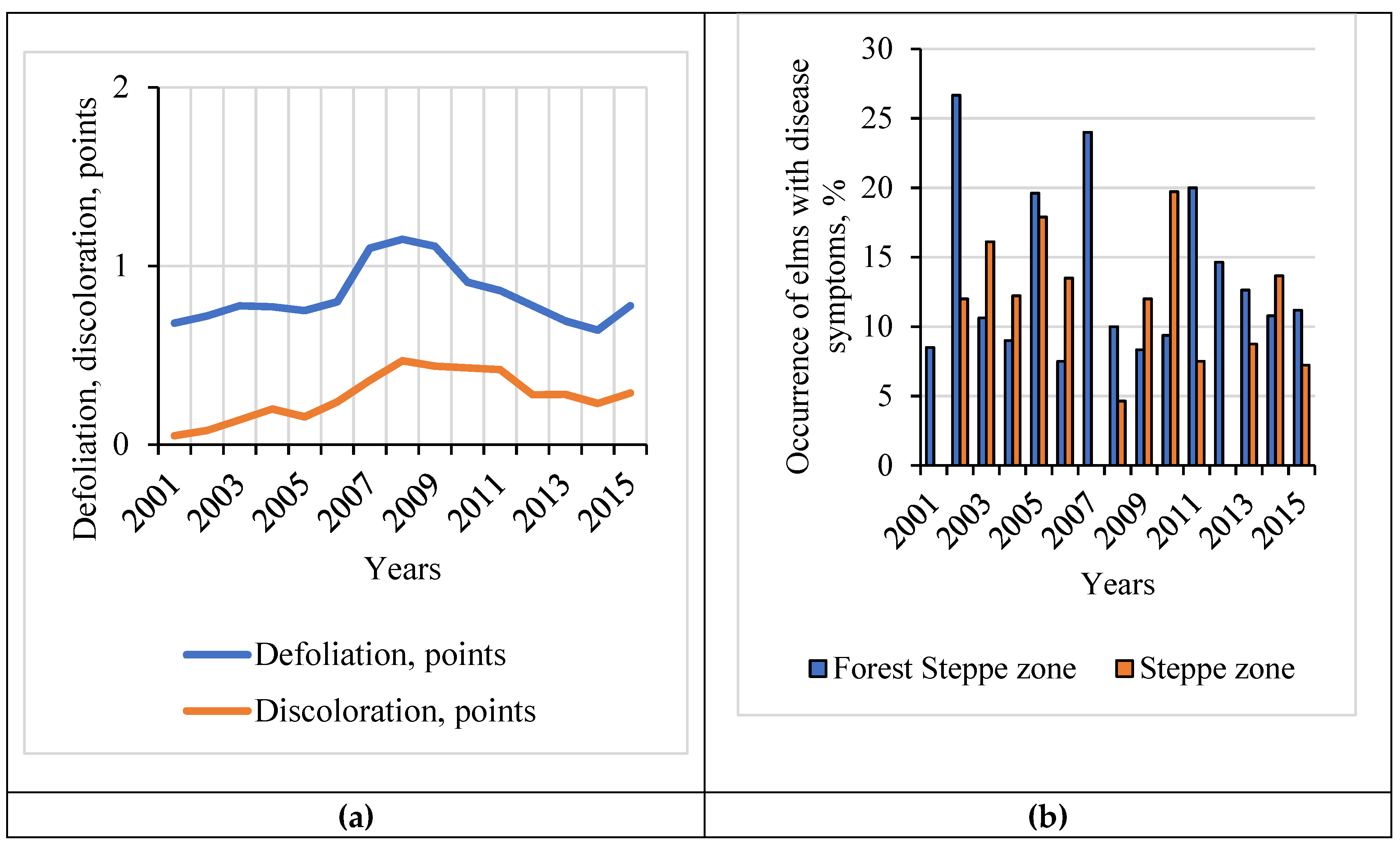

3.2. Ulmus sp. Health in the ICP Monitoring Plots for 2001–2015

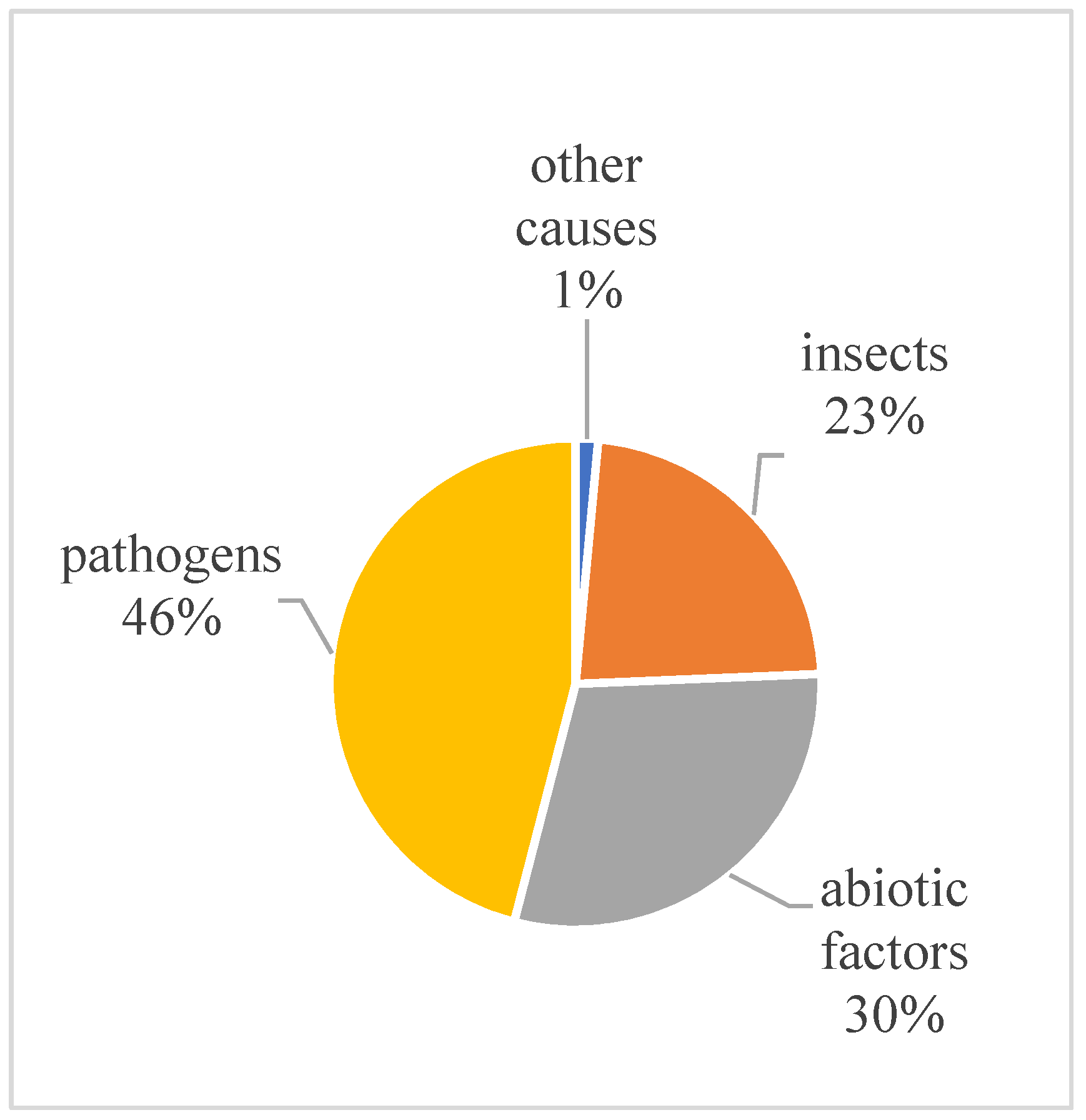

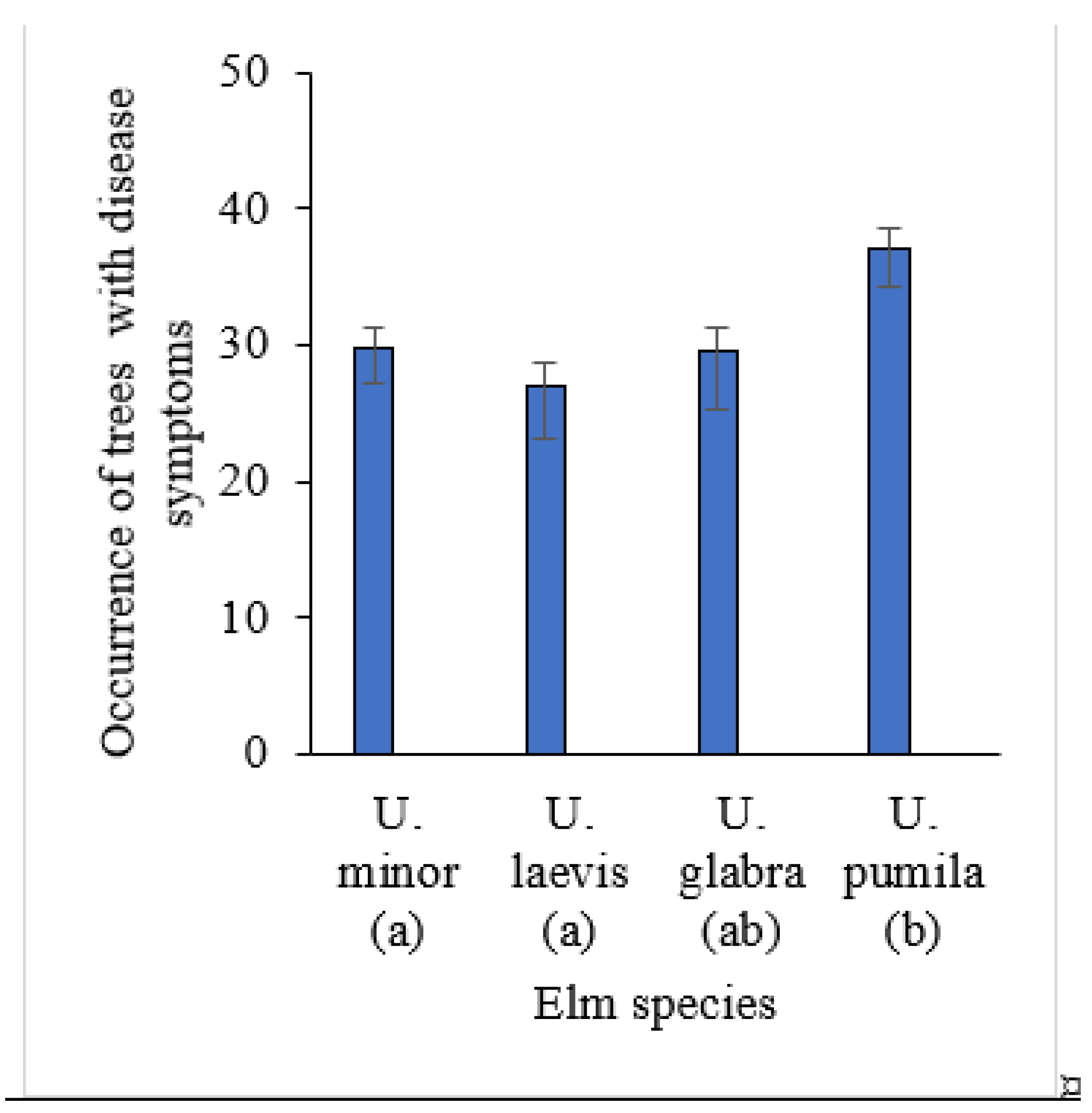

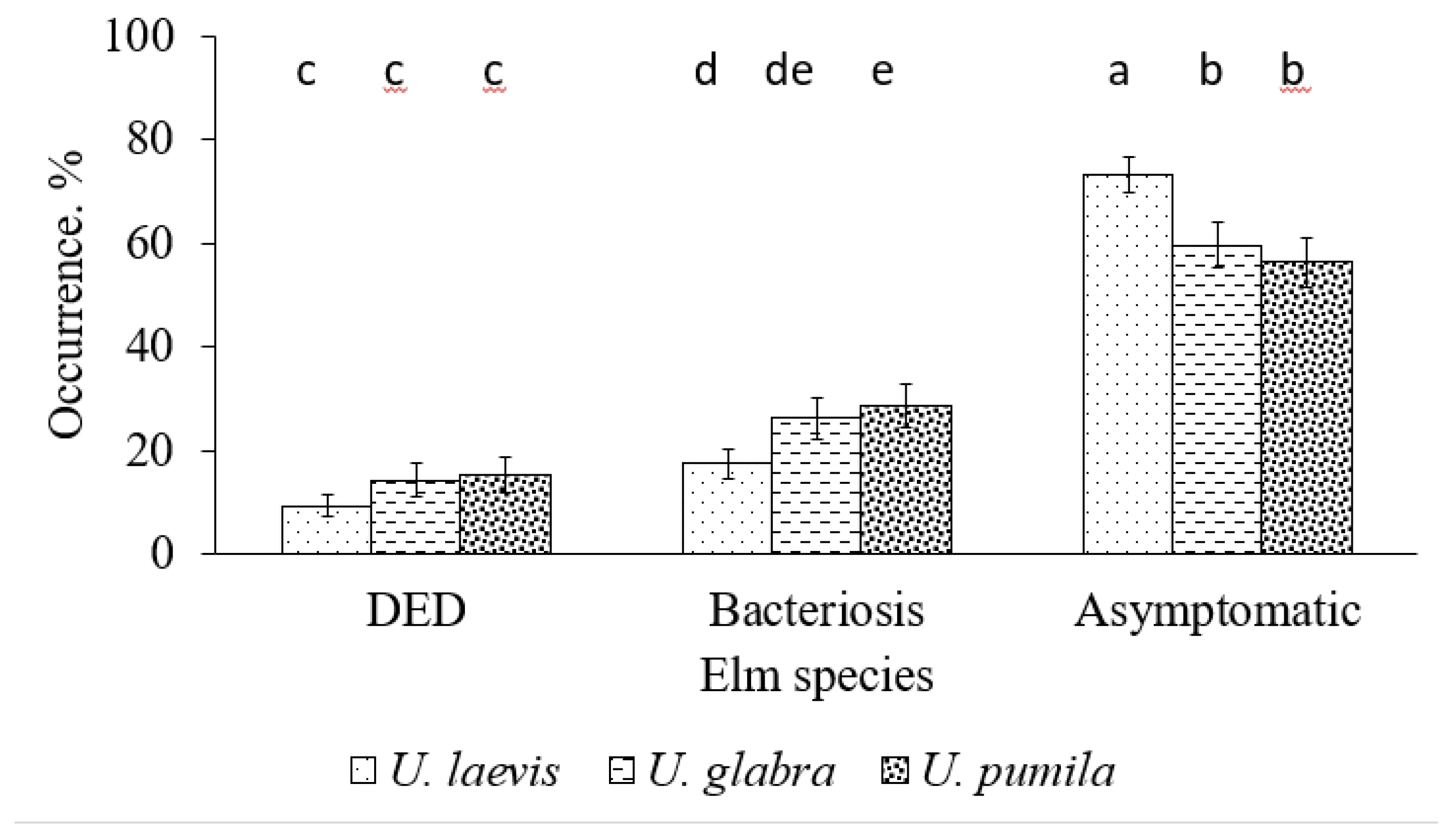

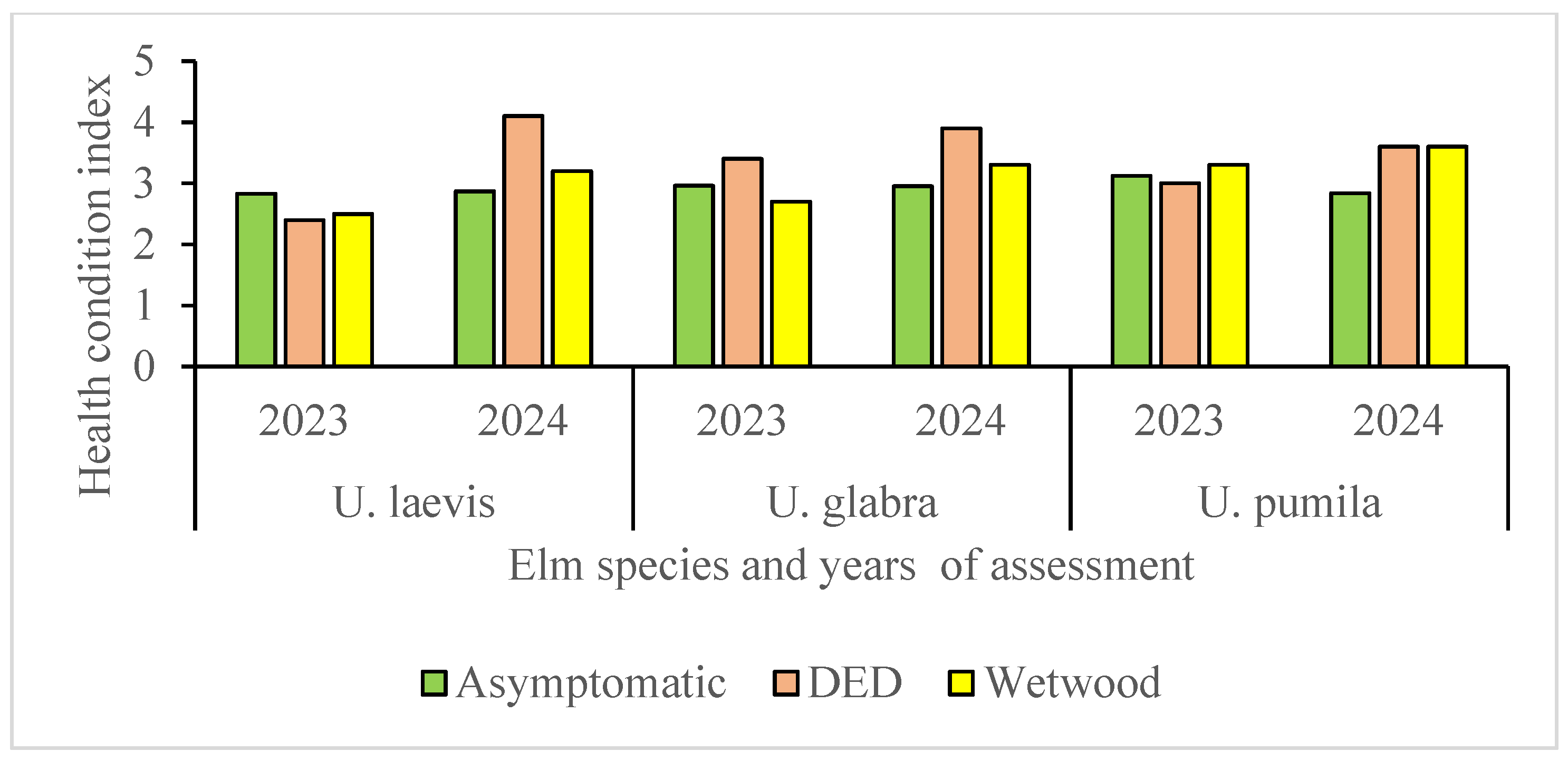

3.3. Biotic factors of Ulmus sp. damage and the probability of tree death or recovery for 2023–2024

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- 1Collin, E.; Bozzano, M. Implementing the dynamic conservation of elm genetic resources in Europe: case studies and perspectives. iForest-Biogeosciences and Forestry. 2015, 8(2), 143–148. [CrossRef]

- Zhigalova, S. L. Families Ulmaceae Mirb. and Celtidaceae Endl. in the flora of Ukraine. Introduction of plants. 2016, 4, 52–58. (in Ukrainian). [CrossRef]

- Christopher, A.; Copeland, R.W.; Harper, N. J.; Brazee Forrest; Bowlick, J. A review of Dutch elm disease and new prospects for Ulmus americana in the urban environmentю Arboricultural Journal. 2023, 45(1), 3–29. [CrossRef]

- Puzrina, N. V., Yavny, M. I. Elm stands of the Kyiv Polissia of Ukraine: silvicultural and health condition. Kyiv: National University of Life and Environmental Sciences of Ukraine, 2020.

- Diekmann, M. Relationship between flowering phenology of perennial herbs and meteorological data in deciduous forests of Sweden. Canadian Journal of Botany, 1996, 74(4), 528-537. [CrossRef]

- Napierala-Filipiak, A.; Filipiak, M.; Lakomy, P.; Kuzminski, R.; & Gubanski, J. Changes in elm (Ulmus) populations of mid-western Poland during the past 35 years. Dendrobiology, 2016, 76, 145–156. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, P.; Yang, C.; Zhang, X.; Tong, B.; Xie, X.; Li, X.; Fan, S. The Growth and Non-Structural Carbohydrate Response Patterns of Siberian Elm (Ulmus pumila) under Salt Stress with Different Intensities and Durations. Forests, 2024, 15(6), 1004. [CrossRef]

- Solla, A.; Martín, J. A.; Corral, P., Gil, L. Seasonal changes in wood formation of Ulmus pumila and U. minor and its relation with Dutch elm disease. New Phytologist, 2005, 166(3), 1025–1034. [CrossRef]

- Hirsch, H.; Brunet, J.; Zalapa, J.; Von Wehrden, H.; Hartmann, M.; Kleindienst, C.; … Hensen, I. Intra- and interspecific hybridization in invasive Siberian elm. Biol Invasions, 2017, 19(6), 1889–1904. hdl:10019.1/122672. S2CID 42755808. [CrossRef]

- Shlapak, V. P.; Maslovata, S. A. The use of plants of the genus Ulmus L. in landscaping and landscape arrangements. Scientific Bulletin of Ukrainian National Forestry University, 2017, 27(1), 11–14. [CrossRef]

- Brasier, C. M. The biosecurity threat to the UK and global environment from international trade in plants. Plant Pathology, 2008, 57, 792–808. [CrossRef]

- Brasier, C. M.; Kirk, S. A. Rapid emergence of hybrids between the two subspecies of Ophiostoma novo-ulmi with a high level of pathogenic fitness. Plant Pathology, 2010, 59, 186– 199. [CrossRef]

- Jürisoo, L.; Adamson, K.; Padari, A.; Drenkhan, R. Health of elms and Dutch elm disease in Estonia. European Journal of Plant Pathology, 2019, 154(7), 1–19. [CrossRef]

- Menkis, A.; Östbrant, I. L.; Wågström, K.; Vasaitis, R. Dutch elm disease on the island of Gotland: monitoring disease vector and combat measures. Scandinavian Journal of Forest Research, 2016, 31, 237–241. [CrossRef]

- Gonthier, P.; Nicolotti, G. (Eds.). Infectious forest diseases. 2013. Cabi. https://www.cabidigitallibrary.org/doi/abs/10.1079/9781780640402.0000.

- Gougherty, A. V. Emerging tree diseases are accumulating rapidly in the native and non-native ranges of Holarctic trees. NeoBiota, 2023, 87, 143–160. [CrossRef]

- Stipes, R. J. The Management of Dutch elm disease. The elms – Breeding, Conservation and Disease Management. Boston, USA: Kluwer Academic Publishers. 2000. Р. 157–172.

- Zalapa, J. E.; Brunet, J. G.; Raymond, P. Genetic diversity and relationships among Dutch elm disease tolerant Ulmus pumila L. Accessions from China. Genome,2008, 51(7), 492–500. [CrossRef]

- Santini, A.; Faccoli, M. Dutch elm disease and elm bark beetles: a century of association. iForest – Biogeosciences and Forestry, 2015, 8, 126–134. [CrossRef]

- Carter, J. C. Wetwood of elms. III. Nat. Hist. Survey, 1945. 23($): 407–448.

- Murdoch, C.W.; Campana, R.J. Bacterial species associated with wetwood of Elm. Phytopathology. 1983, 73. 1270–1273.

- Goychuk, A.; Kulbanska, I.; Shvets, M.; Pasichnyk, L.; Patyka, V.; Kalinichenko, A.; Degtyareva, L. Bacterial diseases of bioenergy woody plants in Ukraine. Sustainability, 2023, 15(5), article number 4189. [CrossRef]

- Goychuk, A.; Kulbanska, I.; Vyshnevskyi, A.; Shvets, M.; Andreieva, O. Spread and harmfulness of infectious diseases of the main forest-forming species in Zhytomyr Polissia of Ukraine. Scientific Horizons, 2022, 25(9), 64-74. [CrossRef]

- Goychuk, A.F.; Drozda, V.F.; Shvets, M.V.; Kulbanska, I. Bacterial wetwood of silver birch (Betula pendula Roth): Symptomology, etiology and pathogenesis. Folia For. Pol. 2020, 62, 145–159.

- La Porta, N.; Hietala, A.M.; Baldi, P. Bacterial diseases in forest trees. In Forest microbiology (Vol. 3, No. 2, pp. 139-166). Cambridge: Academic Press. 2022. Elsevier, ISBN 0443186952, 9780443186950. [CrossRef]

- General characteristics of Ukrainian forests. 2016. Available at: http://dklg.kmu.gov.ua/forest/control/uk/publish/article?art_id=62921&cat_id=32867 (in Ukrainian).

- Ukrainian State Forest Management Planning Association. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://lisproekt.gov.ua/.

- Kulbanska, I.; Shvets, M.; Markov, F. Etiology and Symptomatology of Bacterioses of Wood Plants in the Stands of the Green Zone of the City of Kiev. Sci. Horiz. 2019, 12, 84–95. Available online: https://sciencehorizon.com.ua/web/uploads/pdf/SH_20 19_12_84-95.pdf (accessed on 19 June 2022). [CrossRef].

- Kulbanska, I.M.; Shvets, M.V.; Goychuk, A.F.; Biliavska, L.H.; Patyka, V. Lelliottia nimipressuralis (Carter 1945) Brady et al. 2013—The Causative Agent of Bacterial Dropsy of Common Oak (Quercus robur L.) in Ukraine. Mikrobiolohichnyi Zhurnal, 2021, 83, 30–41. [CrossRef].

- Martín, J. A.; Sobrino-Plata, J.; Rodríguez-Calcerrada, J.; Collada, C.; Gil, L. Breeding and scientific advances in the fight against Dutch elm disease: Will they allow the use of elms in forest restoration? New Forests. 2018. [CrossRef]

- Griffiths, H.M. Forest Diseases Caused by Prokaryotes: Phytoplasmal and Bacterial Diseases. In Infectious Forest Diseases; CABI: Wallingfor, UK, 2013; pp. 76–96. Available online: https://books.google.com.ua/books?hl=uk&lr=&id=_YtcBAAAQBAJ&oi= fnd&pg=PA76&dq=Bacterial+diseases+of+forest+species+&ots=9IZCCHavOZ&sig=t_lpvU3ab45RBYBEC-dEZ-oJeOA&redir_ esc=y#v=onepage&q=Bacterial%20diseases%20of%20forest%20species&f=false (accessed on 19 June 2022).

- Sherif, S. M.; Erland, L. A.; Shukla, M. R.; Saxena, P. K. Bark and wood tissues of American elm exhibit distinct responses to Dutch elm disease. Scientific reports, 2017, 7(1), 7114. [CrossRef]

- Kuznetsova, O.A.; Turenko, V.P.; Tovstukha, O.V.; Davydenko, K.V. Pest and disease incidence of Ulmus sp. in forest shelter belts along the Kyiv-Kharkiv highway. Forestry & Forest Melioration, 2023. 143, 102-111. [CrossRef]

- Meshkova V.L.; Kuznetsova O.A.; Turenko V.P. Symptoms of dwarf elm (Ulmus pumila L.) health condition in the Left-bank Ukraine. Proceedings of the Forestry Academy of Sciences of Ukraine. 2024. Х. ХХ.

- Kardash, E. S. Features of trophic activity of phyllophages in green stands of Kharkiv. The Kharkiv Entomological Society Gazette. 2021. 29 (1),.77–84.

- Sokolova, I.N.; Shvydenko, I. N.; Kardash, E. S. The prevalence of gnawing phyllophagous insects in the deciduous stands of Kharkiv city. Ukrainian Entomological Journal, 2020, 18(1-2), 67-79. [CrossRef]

- Methodical Guidelines for a Survey, Assessment and Forecasting of the Spread of Forest Pests and Diseases for the Lowland Part of Ukraine. Kharkiv: Planeta-Print. ISBN 978-617-7897-00-1] (in Ukrainian).

- Vysotska, N.; Kalashnikov, A.; Sydorenko, S.; Sydorenko, S.; Yurchenko, V. Ecosystem services of shelterbelts as the basis of compensatory mechanisms of their creation and maintenance. Proceedings of the Forestry Academy of Sciences of Ukraine, 2021, 22, 199-208. [CrossRef]

- Gensiruk, S.A. Forests of Ukraine. Lviv: Shevchenko Scientific Society Publishing House, 2002.

- The climate of Ukraine. 2003. Kyiv. 343 p.

- Zepner, L.; Karrasch, P.; Wiemann, F.; Bernard, L. ClimateCharts. Net—An interactive climate analysis web platform. Int. J. Digit. Earth 2021, 14, 338–356.

- Zanaga, D.; Van De Kerchove, R.; Daems, D.; De Keersmaecker, W.; Brockmann, C.; Kirches, G.; Wevers, J.; Cartus, O.; Santoro, M.; Fritz, S.; Lesiv, M.; Herold, M.; Tsendbazar, N.E.; Xu, P.; Ramoino, F.; Arino, O. 2022. ESA WorldCover 10 m 2021 v200. (. [CrossRef]

- QGIS 3.28.1. Available online: https://qgis.org/en/site/ (accessed on 23 September 2024).

- Manual on methods and criteria for harmonized sampling, assessment, monitoring and analysis of the effects of air pollution on forests. UNECE, UNECE ICP Forests, Hamburg, 2010. ISBN: 978-3-926301-03-1. Available at: http://icp-forests.net/page/icp-forests-manual (22.10.2024).

- On approval of the State target program "Forests of Ukraine" for 2010-2015. RESOLUTION of the Cabinet of Ministers of Ukraine of September 16, 2009 No 977, Kyiv]. Retrieved from https://zakon.rada.gov.ua/laws/show/977-2009-%D0%BF#Text (Accessed 12.04.24) (in Ukrainian).

- Sanitary Forests Regulations in Ukraine (2016). [Electronic resource]. Resolution of the Cabinet of Ministers of Ukraine No 756 dated 26 October 2016. Available at: https://zakon.rada.gov.ua/laws/show/756-2016-%D0%BF#n11 (accessed 02.02.2024) (in Ukrainian).

- Meshkova, V. L.; Moroz, S. M.; Kuznetsova, O. A. Bacterial wetwood of Siberian elm (Ulmus рumila L.) in the south of Ukraine. Current state, problems and prospects of forest education, science, and management: Proc. of the IV International Scientific and Practical Internet Conference (Bila Tserkva, April 19, 2024). Bila Tserkva: 2024, BNAU].

- Hammer, O.; Harper, D. A. T.; Ryan, P. D. PAST: paleontological statistics software package for education and data analysis. Palaeontologia Electronica, 2001, 4, 1–9. http://doi.org/palaeo-electronica.org/2001_1/past/issue 1_01.htm.

- Peck, R.; Short, T.; Olsen, C. Introduction to Statistics and Data Analysis; Cengage Learning: Boston, MA, USA. 2020. Retrieved from http://www.statisticslectures.com/topics/ztestproportions/(accessed on 2 March 2024).

- StatisticsLectures.com. Z-Test for Proportions, Two Samples. 2017. Available online: http://www.statisticslectures.com/topics/ztestproportions/ (accessed on 2 March 2024).

- Kulbanska I. M.; Plikhtyak P. P.; Shvets M. V.; Soroka M. I.; Goychuk A. F. Lelliottia nimipressuralis (Carter 1945) Brady et al. 2013 as the causative agent of bacterial wetwood disease of common silver fir (Abies alba Mill.). Folia Forestalia Polonica. 2022. 64(3), 173–183. [CrossRef]

- Lakomy, P.; Kwasna, H.; Kuzminski, R.; Napierala-Filipiak, A.; Filipiak, M.; Behnke, K.; Behnke-Borowczyk, J. Investigation of Ophiostoma population infected elms in Poland. Dendrobiology, 2016, 76.137–144. [CrossRef]

- Pinon, J.; Husson, C.; Collin, E. Susceptibility of native French elm clones to Ophiostoma novo-ulmi. Annals of Forest Science, 2005, 62(7), 689-696. [CrossRef]

| Health classes | Distribution of elm trees by health classes (2–5), % | Total in 2024 |

||||

| in 2023* | in 2024** | |||||

| 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |||

| All trees | ||||||

| 2 | 34.3 | 74.6 | 20.3 | 5.1 | 0.0 | 100.0 |

| 3 | 43.0 | 0.0 | 89.2 | 10.8 | 0.0 | 100.0 |

| 4 | 22.7 | 0.0 | 5.1 | 82.1 | 12.8 | 100.0 |

| Total in 2023 | 100.0 | 25.6 | 46.5 | 25.0 | 2.9 | 100.0 |

| Trees with DED symptoms | ||||||

| 2 | 31.3 | 0.0 | 40.0 | 60.0 | 0.0 | 100.0 |

| 3 | 31.3 | 0.0 | 20.0 | 80.0 | 0.0 | 100.0 |

| 4 | 37.5 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 16.7 | 83.3 | 100.0 |

| Total in 2023 | 100.0 | 0.0 | 18.8 | 50.0 | 31.3 | 100.0 |

| Trees with bacteriosis symptoms | ||||||

| 2 | 23.3 | 28.6 | 71.4 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 100.0 |

| 3 | 53.3 | 0.0 | 75.0 | 25.0 | 0.0 | 100.0 |

| 4 | 23.3 | 0.0 | 28.6 | 71.4 | 0.0 | 100.0 |

| Total in 2023 | 100.0 | 6.7 | 63.3 | 30.0 | 0.0 | 100.0 |

| Health classes | Distribution of elm trees by health classes (2–5), % | Total in 2024 |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| in 2023* | in 2024** | |||||

| 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |||

| All trees | ||||||

| 2 | 15.1 | 31.6 | 68.4 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 100.0 |

| 3 | 61.1 | 14.3 | 58.4 | 27.3 | 0.0 | 100.0 |

| 4 | 23.8 | 0.0 | 53.3 | 36.7 | 10.0 | 100.0 |

| Total in 2023 | 100.0 | 13.5 | 58.7 | 25.4 | 2.4 | 100.0 |

| Trees with DED symptoms | ||||||

| 3 | 55.6 | 0.0 | 30.0 | 70.0 | 0.0 | 100.0 |

| 4 | 44.4 | 0.0 | 25.0 | 37.5 | 37.5 | 100.0 |

| Total in 2023 | 100.0 | 0.0 | 27.8 | 55.6 | 16.7 | 100.0 |

| Trees with bacteriosis symptoms | ||||||

| 2 | 18.2 | 0.0 | 100.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 100.0 |

| 3 | 60.6 | 0.0 | 70.0 | 30.0 | 0.0 | 100.0 |

| 4 | 21.2 | 0.0 | 57.1 | 42.9 | 0.0 | 100.0 |

| Total in 2023 | 100.0 | 0.0 | 72.7 | 27.3 | 0.0 | 100.0 |

| Health classes | Distribution of elm trees by health classes (2–5), % | Total in 2024 |

||||

| in 2023* | in 2024** | |||||

| 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |||

| All trees | ||||||

| 2 | 8.9 | 50.0 | 20.0 | 30.0 | 0.0 | 100.0 |

| 3 | 60.7 | 14.7 | 72.1 | 13.2 | 0.0 | 100.0 |

| 4 | 30.4 | 0.0 | 44.1 | 44.1 | 11.8 | 100.0 |

| Total in 2023 | 100.0 | 13.4 | 58.9 | 24.1 | 3.6 | 100.0 |

| Trees with DED symptoms | ||||||

| 2 | 11.8 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 100.0 | 0.0 | 100.0 |

| 3 | 52.9 | 11.1 | 55.6 | 33.3 | 0.0 | 100.0 |

| 4 | 35.3 | 0.0 | 16.7 | 50.0 | 33.3 | 100.0 |

| Total in 2023 | 100.0 | 5.9 | 35.3 | 47.1 | 11.8 | 100.0 |

| Trees with bacteriosis symptoms | ||||||

| 2 | 6.3 | 0.0 | 50.0 | 50.0 | 0.0 | 100.0 |

| 3 | 50.0 | 12.5 | 50.0 | 37.5 | 0.0 | 100.0 |

| 4 | 43.8 | 0.0 | 14.3 | 71.4 | 14.3 | 100.0 |

| Total in 2023 | 100.0 | 6.3 | 34.4 | 53.1 | 6.3 | 100.0 |

| Elm species | Mortality, %±SE | |

| DED | Bacteriosis | |

| U. laevis | 31.3±3.53 | 0.0 |

| U. glabra | 16.7±3.32 | 0.0 |

| U. pumila | 11.8±3.04 | 6.3±2.29 |

| Group of trees | Number of trees in the group | Intercept a±SE | Slope b±SE |

R2 | p |

| U. laevis | |||||

| Wetwood | 30 | 1.73±0.38 | 0.50±0.12 | 0.37 | <0.001 |

| DED | 16 | 2.20±0.47 | 0.63±0.15 | 0.56 | <0.001 |

| All inspected | 172 | 0.51±0.13 | 0.88±0.04 | 0.69 | <0.001 |

| U. glabra | |||||

| Wetwood | 33 | 2.63±0.37 | 0.21±0.12 | 0.09 | 0.09 |

| DED | 18 | 2.43±1.09 | 0.43±0.31 | 0.10 | 0.19 |

| All inspected | 126 | 1.81±0.28 | 0.44±0.09 | 0.16 | <0.001 |

| U. pumila | |||||

| Wetwood | 32 | 1.87±0.66 | 0.51±0.19 | 0.19 | 0.01 |

| DED | 17 | 2.54±0.96 | 0.34±0.29 | 0.08 | 0.26 |

| All inspected | 112 | 1.46±0.32 | 0.53±0.1 | 0.20 | <0.001 |

| all elm species | |||||

| Wetwood | 95 | 1.98±0.26 | 0.44±0.08 | 0.24 | <0.001 |

| DED | 51 | 2.44±0.46 | 0.44±0.14 | 0.17 | 0.002 |

| All inspected | 410 | 1.06±0.13 | 0.68±0.04 | 0.39 | <0.001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).