Submitted:

04 March 2024

Posted:

05 March 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Fly Lines

2.2. Bioinformatics Analysis

2.3. RNA Isolation and Quantitative RT-PCR

2.4. Male Fertility Test

2.5. Immunofluorescence Staining

2.6. TUNEL Assay

2.7. RNA Sequencing

2.8. Bioinformatics Analysis of RNA-seq Data

2.9. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Expression Profile of Fd59a in Drosophila

3.2. Sequence and Phylogenetic Analyses of Fd59a

3.3. Loss of Function in Fd59a Affects Testis Development and Male Fertility

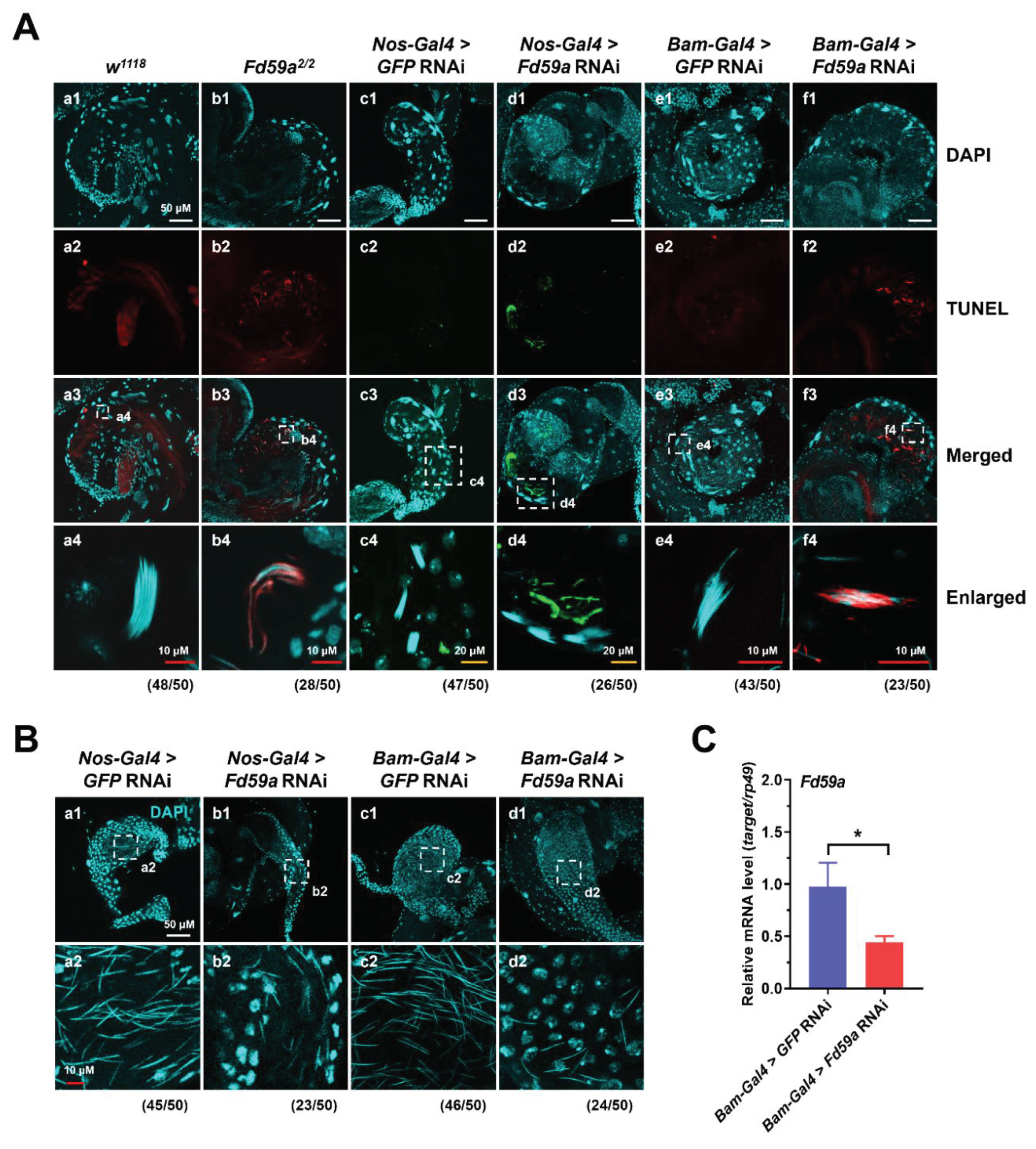

3.4. Loss of Function in Fd59a Affects Spermatogenesis

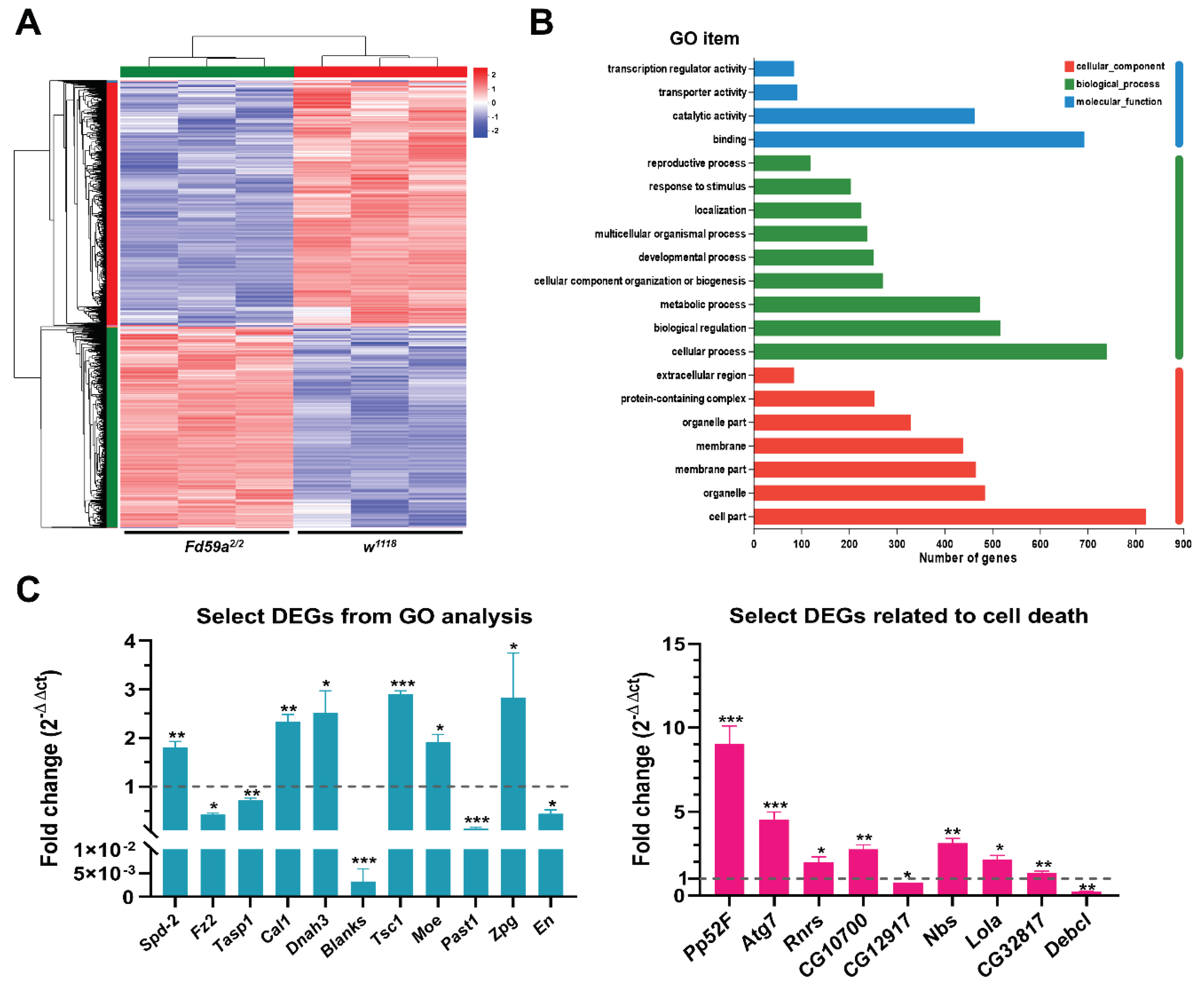

3.5. Fd59a Regulates Gene Expression in the Testis

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Akhlaghipour, I.; Fanoodi, A.; Zangouei, A. S.; Taghehchian, N.; Khalili-Tanha, G.; Moghbeli, M. MicroRNAs as the Critical Regulators of Forkhead Box Protein Family in Pancreatic, Thyroid, and Liver Cancers. Biochemical genetics 2023, 61, 1645–1674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaestner, K.H.; Knochel, W.; Martinez, D.E. Unified nomenclature for the winged helix/forkhead transcription factors. Genes & development 2000, 14, 142–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quintero-Ronderos, P.; Laissue, P. The multisystemic functions of FOXD1 in development and disease. Journal of molecular medicine (Berlin, Germany) 2018, 96, 725–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, K.; Chen, S.; Zhu, C.; Li, L.; Yu, C.; He, Z.; Sun, C. FOXD1 facilitates pancreatic cancer cell proliferation, invasion, and metastasis by regulating GLUT1-mediated aerobic glycolysis. Cell Death & Disease 2022, 13, 765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, W.; Li, Y.; Li, R.; Chen, W.; Song, M.; Zhang, Q.; Chen, S. The Prognostic Significance of FOXD1 Expression in Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Journal of Personalized Medicine 2023, 13, 530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, S.J.; Li, D.; Shen, Z.S.; Li, Q.; Shen, Y.; Deng, H.X.; Wu, Y.D.; Zhou, C.C. Diagnostic and prognostic value of FOXD1 expression in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Journal of Cancer 2021, 12, 693–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scimone, M.L.; Lapan, S.W.; Reddien, P.W. A forkhead transcription factor is wound-induced at the planarian midline and required for anterior pole regeneration. PLoS genetics 2014, 10, e1003999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lacin, H.; Rusch, J.; Yeh, R. T.; Fujioka, M.; Wilson, B. A.; Zhu, Y.; Robie, A. A.; Mistry, H.; Wang, T.; Jaynes, J. B.; Skeath, J. B. Genome-wide identification of Drosophila Hb9 targets reveals a pivotal role in directing the transcriptome within eight neuronal lineages, including activation of nitric oxide synthase and Fd59a/Fox-D. Developmental biology 2014, 388, 117–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siddall, N. A.; Hime, G. R. A Drosophila toolkit for defining gene function in spermatogenesis. Reproduction (Cambridge, England) 2017, 153, R121–R132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fabian, L.; Brill, J. A. Drosophila spermiogenesis: Big things come from little packages. Spermatogenesis 2012, 2, 197–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greenspan, L.J.; de Cuevas, M.; Matunis, E. Genetics of gonadal stem cell renewal. Annual review of cell and developmental biology 2015, 31, 291–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drummond-Barbosa, D. Local and Physiological Control of Germline Stem Cell Lineages in Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics 2019, 213, 9–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nyberg, K.G.; Carthew, R.W. Out of the testis: biological impacts of new genes. Genes & development 2017, 31, 1825–1826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Y.; Zhang, F.; Zhan, Y.; Lu, M.; Xu, D.; Wang, J.; Li, Q.; Zhao, L.; Su, Y. RpS3 Is Required for Spermatogenesis of Drosophila melanogaster. Cells 2023, 12, 573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M. Y.; Duan, X.; Wang, Q.; Ran, M. J.; Ai, H.; Zheng, Y.; Wang, Y. F. Cytochrome c1-like is required for mitochondrial morphogenesis and individualization during spermatogenesis in Drosophila melanogaster. The Journal of experimental biology 2023, 226, jeb245277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, X.; Chen, D.; Zheng, S.; Yi, M.; Liu, Z.; Liu, Y.; Yang, D.; Liu, Y.; Tang, L.; Zhu, C.; Huang, Y. BmHen1 is essential for eupyrene sperm development in Bombyx mori but PIWI proteins are not. Insect biochemistry and molecular biology 2022, 151, 103874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Q.; Zhu, Z.; Zhao, D.; Zeng, B.; Zheng, S.; Song, Q.; Deng, H.; Feng, Q. Bombyx mori transcription factors FoxA and SAGE divergently regulate the expression of wing cuticle protein gene 4 during metamorphosis. The Journal of biological chemistry 2019, 294, 632–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.; Li, Z.; Tong, X.; Chen, C.; Chen, M.; Meng, G.; Chen, P.; Li, C.; Xin, Y.; Gai, T.; Dai, F.; Lu, C. Genome-wide identification and characterization of Fox genes in the silkworm, Bombyx mori. Functional & integrative genomics 2015, 15, 511–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chintapalli, V.R.; Wang, J.; Dow, J.A. Using FlyAtlas to identify better Drosophila melanogaster models of human disease. Nature genetics 2007, 39, 715–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Q.; Xiao, Y.; Wei, R.; Tang, T.; Wen, L.; Lu, Y.; Yu, X. Q. Identification and functional analysis of CG3526 in spermatogenesis of Drosophila melanogaster. Insect science 2024, 31, 79–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biwot, J.C.; Zhang, H.B.; Chen, M.Y.; Wang, Y.F. A new function of immunity-related gene Zn72D in male fertility of Drosophila melanogaster. Archives of Insect Biochemistry and Physiology 2019, 102, e21612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stamatakis, A. RAxML version 8: A tool for phylogenetic analysis and post-analysis of large phylogenies. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 1312–1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Livak, K.J.; Schmittgen, T.D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2-ΔΔCt Method. Methods 2001, 25, 402–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, T.; Xiao, Y.; Huang, B.; Ran, M. J.; Duan, X.; Wang, Y. F.; Lu, Y.; Yu, X. Q. A dual role of lola in Drosophila ovary development: regulating stem cell niche establishment and repressing apoptosis. Cell death & disease 2022, 13, 756. [Google Scholar]

- Loza-Coll, M.A.; Petrossian, C.C.; Boyle, M.L.; Jones, D.L. Heterochromatin Protein 1 (HP1) inhibits stem cell proliferation induced by ectopic activation of the Jak/STAT pathway in the Drosophila testis. Experimental cell research 2019, 377, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Yan, T.; Wu, X.; Ke, X.; Li, X.; Zhu, Y.; Yang, J.; Li, Z. Aberrant overexpression of transcription factor Forkhead box D1 predicts poor prognosis and promotes cancer progression in HNSCC. BMC cancer 2021, 21, 1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smendziuk, C.M.; Messenberg, A.; Vogl, A.W.; Tanentzapf, G. Bi-directional gap junction-mediated soma-germline communication is essential for spermatogenesis. Development (Cambridge, England) 2015, 142, 2598–2609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.; Gao, Y.; Song, X.; Ma, X.; Zhu, X.; Mao, Y.; Yang, Z.; Ni, J.; Li, H.; Malanowski, K. E.; Anoja, P.; Park, J.; Haug, J.; Xie, T. Wnt signaling-mediated redox regulation maintains the germ line stem cell differentiation niche. eLife 2015, 4, e08174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akdemir, F.; Christich, A.; Sogame, N.; Chapo, J.; Abrams, J.M. p53 directs focused genomic responses in Drosophila. Oncogene 2007, 26, 5184–5193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santhanam, A.; Peng, W.H.; Yu, Y.T.; Sang, T.K.; Chen, G.C.; Meng, T.C. Ecdysone-induced receptor tyrosine phosphatase PTP52F regulates Drosophila midgut histolysis by enhancement of autophagy and apoptosis. Molecular and cellular biology 2014, 34, 1594–1606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Liu, Y.; Lan, X.; Wu, H.; Wen, Y.; Zhou, Z.; Hu, Z.; Sha, J.; Guo, X.; Tong, C. CHES-1-like, the ortholog of a non-obstructive azoospermia-associated gene, blocks germline stem cell differentiation by upregulating Dpp expression in Drosophila testis. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 42303–42313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kiger, A.A.; Jones, D.L.; Schulz, C.; Rogers, M.B.; Fuller, M.T. Stem cell self-renewal specified by JAK-STAT activation in response to a support cell cue. Science (New York, N.Y.) 2001, 294, 2542–2545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herrera, S.C.; Bach, E.A. The Emerging Roles of JNK Signaling in Drosophila Stem Cell Homeostasis. International journal of molecular sciences 2021, 22, 5519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ng, C.L.; Qian, Y.; Schulz, C. Notch and Delta are required for survival of the germline stem cell lineage in testes of Drosophila melanogaster. PloS one 2019, 14, e0222471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ajay, A. K.; Zhao, L.; Vig, S.; Fujiwara, M.; Thakurela, S.; Jadhav, S.; Cho, A.; Chiu, I. J.; Ding, Y.; Ramachandran, K.; Mithal, A.; Bhatt, A.; Chaluvadi, P.; Gupta, M. K.; Shah, S. I.; Sabbisetti, V. S.; Waaga-Gasser, A. M.; Frank, D. A.; Murugaiyan, G.; Bonventre, J. V.; Hsiao, L. L. Deletion of STAT3 from Foxd1 cell population protects mice from kidney fibrosis by inhibiting pericytes trans-differentiation and migration. Cell reports 2022, 38, 110473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosendahl, A. H.; Monnius, M.; Laitala, A.; Railo, A.; Miinalainen, I.; Heljasvaara, R.; Mäki, J. M.; Myllyharju, J. Deletion of hypoxia-inducible factor prolyl 4-hydroxylase 2 in FoxD1-lineage mesenchymal cells leads to congenital truncal alopecia. The Journal of biological chemistry 2022, 298, 101787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanders, C.; Smith, D.P. LUMP is a putative double-stranded RNA binding protein required for male fertility in Drosophila melanogaster. PloS one 2011, 6, e24151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshinari, Y.; Ameku, T.; Kondo, S.; Tanimoto, H.; Kuraishi, T.; Shimada-Niwa, Y.; Niwa, R. Neuronal octopamine signaling regulates mating-induced germline stem cell increase in female Drosophila melanogaster. eLife 2020, 9, e57101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohhara, Y.; Kayashima, Y.; Hayashi, Y.; Kobayashi, S.; Yamakawa-Kobayashi, K. Expression of β-adrenergic-like octopamine receptors during Drosophila development. Zoological science 2012, 29, 83–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Name | Forward Primer (5′–3′) | Reverse Primer (5′–3′) |

|---|---|---|

| Fd59a-qRT | CAGGGAAGTCAGTCGGGGGA | GTCGCCACATCGAAGGCGTA |

| Rp49-qRT | GCCCAAGGGTATCGACAACA | ACCTCCAGCTCGCGCACGTT |

| Spd-2-qRT | GTGACCCACACGACCCTCTG | GCCGAATGACCAGCCGTTTG |

| Fz2-qRT | TCGCGAGTCACAATTGCACC | GGACGCCACTCTACGGTGTT |

| Tasp1-qRT | CGGCATGCGAGTCTGTTCGG | ACACAAGGCAGCGCAAGTCTA |

| Debcl-qRT | ATCGACAACGGCGGATGGTT | ACGCGATCCCAAGCGAATCT |

| Ptp52F-qRT | TGTCCGACGATCTTTGCGCT | GGCGTAGGGGGAAAGTGGAC |

| Atg7-qRT | TACAACTGCTGGCCGATGAGG | GCACGGAAAGGCGAACCAAT |

| RnrS-qRT | GGACCGTTTGCTCGTGGAGT | GAAATCCGCGTCCAGGGTGA |

| CG10700-qRT | TGTGGAGGCTACGGCCAATC | TCACCACGGCTGTTTCCCAA |

| CG12917-qRT | CAGGGGCTTCCTTCAGTCGG | AAATAGCCAGACACGGGGGC |

| Nbs-qRT | ATTCCCAAAAGCCGCGCAAG | TGGGTCACCTGCCAAATGCT |

| Lola-qRT | CTGCTGAGATATGCGAGCCAGA | GTTCACAATGGCCTCCGCCT |

| Cal1-qRT | GGTGGTGGACGAGGAAACACT | TCCACAGCCTCCTTTGCCAC |

| Dnah3-qRT | AGAGCTGGCAAGAGCGGAAA | ACATTGCGAGACGTGGCACC |

| Blanks-qRT | ACGGGCCAGGAAAGAGCTTG | ACGGCTTCTTTGGCTCGACA |

| En-qRT | CCAACGACGAGAAGCGTCCA | CTCCGCTCGGTCAGATAGCG |

| Tsc1-qRT | GGTTGGCATGACTGGCTCCT | CACGTCCCGGCTGCTTGATA |

| CG32817-qRT | AATCAAGTGTCTAACCCTGAACTGG | GTTGCGCCATCGAAAAGCAT |

| Moe-qRT | GCCTGCGAGAGGTTTGGTTCTT | TCACGTCCTGGTTCATCACCTT |

| Past1-qRT | ACACCCGATCACACAGCCTC | CGCCTGCACTGTGTGGCTAA |

| Zpg-qRT | GGGGCCTATGTGAGCGACAA | CCGCCCTCCCAAATCTTCCA |

| Proteins | Species | Accession Number |

|---|---|---|

| Forkhead box protein D5 | Bombyx mori | XP_004922516.1 |

| uncharacterized protein LOC5564025 | Aedes aegypti | XP_001648348.3 |

| Forkhead box protein D3 | Manduca sexta | XP_030032680.1 |

| Forkhead box protein D3-B | Plutella xylostella | XP_037961710.1 |

| Forkhead box protein D3-like | Spodoptera frugiperda | XP_035435321.1 |

| Forkhead box protein D5-like | Spodoptera litura | XP_022815528.1 |

| Forkhead box protein D3-like | Nilaparvata lugens | XP_039277739.1 |

| Forkhead box protein D3-like | Ceratosolen solmsi marchali | XP_011504225.1 |

| Fork head domain-containing protein FD3 | Papilio xuthus | KPJ03207.1 |

| Forkhead box protein D3-like | Bemisia tabac | XP_018914635.1 |

| Forkhead box protein D3-A | Blattella germanica | PSN41724.1 |

| Forkhead box protein D5 | Helicoverpa armigera | XP_021187147.2 |

| Forkhead box protein D3 | Danio rerio | NP_571365.2 |

| Forkhead box protein unc-130 | Caenorhabditis elegans | NP_496411.1 |

| Forkhead box protein D4 | Homo sapiens | NP_997188.2 |

| Forkhead box protein D3 | Mus musculus | NP_034555.3 |

| Forkhead box protein D5-A | Xenopus laevis | NP_001081998.1 |

| Forkhead box protein D3 isoform X1 | Manis javanica | XP_036880296.1 |

| Forkhead box protein D3 | Caretta caretta | XP_048718258.1 |

| Forkhead box protein B1-like | Octopus sinensis | XP_029653697.1 |

| Forkhead box protein D3-like | Branchiostoma floridae | XP_035698942.1 |

| Forkhead box protein D3 | Rattus norvegicus | NP_542952.1 |

| Gene Symbol | Log2 Fold Difference | Relative Expression | Biological Functions | Forkhead Binding Sites |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GO analysis related genes | ||||

| Spd-2 | 1.08 | Up-regulated | Involved in sperm aster formation | 13 |

| Fz2 | -1.66 | Down-regulated | Germ-line stem cell niche homeostasis | 6 |

| Tasp1 | -1.35 | Down-regulated | Involved in spermatogenesis | 7 |

| Cal1 | 0.61 | Up-regulated | Female meiosis chromosome segregation | 10 |

| Dnah3 | 0.70 | Up-regulated | Involved in sperm competition | 6 |

| Blanks | -0.72 | Down-regulated | Involved in sperm individualization | 11 |

| Tsc1 | 0.76 | Up-regulated | Negative regulation of developmental growth | 4 |

| Moe | 0.67 | Up-regulated | Oocyte anterior/posterior axis specification | 10 |

| Past1 | -2.62 | Down-regulated | Involved in sperm individualization | 3 |

| Zpg | 1.33 | Up-regulated | Male germ-line stem cell population maintenance | 5 |

| En | -1.40 | Down-regulated | Involved in gonad development | 8 |

| Cell death related genes | ||||

| Ptp52F | 3.44 | Up-regulated | Involved in larval midgut cell programmed cell death | 15 |

| Atg7 | 1.60 | Up-regulated | Involved in autophagy | 2 |

| RnrS | 0.68 | Up-regulated | Involved in activation of cysteine-type Endopeptidase activity involved in apoptotic process | 9 |

| CG10700 | 0.822 | Up-regulated | Involved in execution phase of apoptosis | 9 |

| CG12917 | -0.62 | Down-regulated | Involved in apoptotic DNA fragmentation | 4 |

| Nbs | 0.78 | Up-regulated | Involved in intrinsic apoptotic signaling pathway in response to DNA damage | 2 |

| Lola | 0.74 | Up-regulated | Involved in nurse cell apoptotic process | 14 |

| CG32817 | 0.78 | Up-regulated | Involved in extrinsic apoptotic signaling pathway | 0 |

| Debcl | -1.92 | Down-regulated | Programmed cell death involved in cell development | 11 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).