1. Introduction

Human beings have an innate need to compete with others, which is evident in all of our social interactions and has a lengthy history [

1]. Competition permeates all spheres of life and has emerged as a prevalent subject in the realms of education, psychology, economics, and management [

2,

3]. Especially in education, Competition is a reality that both students and teachers must recognize and give due consideration [

4].

Considerable researches have focused on the impact of competition on anxiety and learning. While competition is known to significantly heighten students’ anxiety levels [

5,

6], but how competition impacts the learning process and performance remains controversial [

7,

8,

9].One perspective suggests that competition impairs students’ learning process [

10,

11,

12]. According to several studies, competition increases individuals’ cognitive loads during the learning process [

13,

14]. In competitive learning environments, students often opt for easier tasks, leading to decreased levels of learning [

15]. Conversely, another viewpoint argues that competition enhances students’ learning outcomes [

16,

17,

18]. Some research has shown a significant positive relationship between competition and academic performance [

19]. Researchers have observed that competition motivates students and boost their performance [

20,

21]. In addition, some researches found that competition has no significant impact on students’ learning process [

22,

23] or their academic achievement [

24]. The relationship between competition and learning is intricate, sparking ongoing debates in academia about its effects on students’ learning. Further exploration of the specific mechanisms through which competition influences learning is needed to deepen our understanding of this relationship.

Currently, two primary theories elucidate the impact of competition on the learning process and outcomes. Initially, Gray posits the existence of two universal motivational systems governing behavior and emotion: the Behavioral Inhibition System (BIS) and the Behavioral Activation System (BAS) [

25,

26]. Gray argues that the BIS regulates aversive motivation and manages anxiety responses triggered by anxiety-related cues. Sensitized to signals of punishment, non-reward, and novelty, the BIS can activate, prompting behavioral inhibition to steer us away from unpleasant experiences. Gray further suggests that the BIS may contribute to the emergence of negative emotional states like anxiety, depression, and sadness. Conversely, the BAS governs appetitive motivation, stimulating behavior and directing us toward desired outcomes [

27]. The BAS exhibits high sensitivity to signals of reward, non-punishment, and avoidance of punishment. Gray also posits that the BAS plays a pivotal role in fostering positive emotions such as hope, joy, and pleasure. Although Gary’s theory has previously been widely used to explain maladaptive behaviours, such as procrastination and addiction [

66], relatively little attention has been paid to the direct effects of the learning process itself, which needs to be explored in terms of how these systems affect cognitive processes, motivation and overall learning. Secondly, the Attentional control theory (ACT), viewed through the lens of cognitive processing, elucidates how anxiety influences cognitive performance [

28]. ACT has two hypotheses. The first hypothesis holds that anxiety alters the balance between the two attention systems by amplifying the bottom-up stimulus-driven attention system while impeding the top-down goal-directed attention system. The second hypothesis states that anxiety primarily interferes with the inhibitory and transformational functions of the central executive system, reducing its processing efficiency. ACT provides a theoretical basis for researching the effect of anxiety on learning, which is supported by numerous empirical studies [

29,

30,

31]. These studies found that individuals in the high-anxiety group tend to exhibit poorer performance in terms of processing efficiency and task outcomes. Competitive environments often elevate anxiety levels among individuals [

5,

6], leading to decreased attentional control and subsequently influencing learning outcomes.

In essence, both theories have certain strengths, Gray’s theory delves into the mechanisms through which competition impacts learning at a motivational level, while ACT scrutinizes the influence of competition on the learning process from a cognitive perspective. Our study aimed to integrate these two theories to explore how competition impacts learning process and outcomes.

Moreover, on one hand, most of the competition studies were carried out with threatening stimulus in laboratory conditions [

32,

33,

34,

35], and the effect of competition on real learning situation is scarce. On the other hand, a few studies of competition in practical situations frequently use questionnaires to investigate the impact of daily perceived competition on learning [

36,

37], and many irrelevant variables are not controlled. Therefore, the present study try to explore how competition affects MOOC online learning, which has globally seen a surge in popularity [

38,

39,

40,

41].

Thus, the current studies aimed to investigate the effect of peer competition on learning process and outcome in the setting of MOOC learning. Based on BIS/BAS hypothesis, Study 1 investigated the effects of peer competition (high and low stress) on trait anxiety (TA) and state anxiety (SA), subjective cognitive load (SCL), and test scores, and the role of BIS/BAS in anxiety and learning. Furthermore, in order to repeat study 1, we further conducted study 2 with portable EEG headband to measure the attention level. The current studies specifically examined the learning performance of students from two universities (Beijing Normal University and Ningbo University) in peer competition.

2. Pilot study

Before the formal experiment, a pilot study was conducted to assess the levels of difficulty and discrimination of the quiz items for five micro-lectures. After surveying available resources for appropriate materials for non-science major Chinese students in their second semester, we selected two micro-economics modules and three physics micro-lectures from “Chinese University MOOC” (

https://www.icourse163.org). Each of the micro-lectures was about 5 minutes long. For the micro-economics, we choose an easy module which emphasizes on one concept and the hard module which introduces three concept and their dynamic relation from one lecturer. The three comparable difficulty physics micro-lectures are chosen from another lecturer and each one introduces one principle of physics relevant to Bernoulli principle, Doppler principle and Pascal’s principle. A quiz was created for each micro-lecture. Following Bloom’s Taxonomy of Learning Objectives [

44], the quizzes included questions about knowledge, comprehension, and application. Of the final 46 items, there were 27 knowledge items, 13 comprehension items, and 6 application items. The three types of items were weighted as follows: a weight of 1 for knowledge, 2 for comprehension, and 3 for application. The theoretical range of scores was 0 to 71.

27 students were recruited to watch the five micro-lectures and answered 50 corresponding questions. Four questions were found to be poor items (i.e., the criterion of item difficulty, P (proportion of students scored correctly) < 0.25 or > 0.75; and discrimination, R (biserial correlation between item and total score) < 0.20). In the formal experiment, students learned the micro-lectures and answered only the remaining 46 questions. In terms of the quizzes, the reliability (internal consistency) of the total test of the final 46 items was acceptable (α = 0.610).

3. Study 1

3.1. Method

3.1.1. Participants

Participants of the experiment were 101 undergraduate and postgraduate students who major in humanities and social sciences (excluded economics) only from Ningbo. 50 of them were assigned to 25 pairs for the competition condition (stressful condition). For each pair the students, they must participate the experiment together and learning the MOOC materials synchronously. The rest 50 students were assigned to the control condition (nonstressful condition) and they completed the experiment by themselves. Students were compensated for this experiment. While for the control group, all students got pained with 25 Ren Min Bi (RMB) after complete the experiment. For the competition group, in addition to the 25 RMB, they were told that the one who achieved higher test score will get extra 5 RMB as reward. Both the students signed informed consent forms after a full explanation of the study procedure. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Ningbo University.

3.1.2. Materials and Tasks

Self-reported scales

Behavioral inhibition/activation was assessed by a-18 item self-described “the Behavioral Inhibition/Activation System Scale (BIS-BAS)”, developed by carver & white [

27] and revised by Li [

45], which has been proved to be suitable for Chinese. The scale consists of the BIS and BAS, with the BIS consisting of 5 items (e.g., being criticized or blamed makes me feel bad) and the BAS divided into 3 sub_scales consisting of 5 pleasure seeking items (BASF)(e.g., I often act on impulse), 4 reward response items (BASR)(e.g., winning a race makes me excited), 4 drive items (BASD)(e.g., I will do everything I can to get what I want). Each participant’s response to the items was rated on a scale of 1 to 4 (1 = ‘‘I do not agree at all’’, 4 = ‘‘I totally agree’’). The Cronbach’α coefficient for each dimension of the scale in the study ranged from 0.68 to 0.90.

The State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) [

46]consists of two scales of 40 items, items 1-20 are the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (S-AI), which assesses the patient’s immediate or time-specific anxiety (e.g., I feel calm); items 21-40 are the Trait Anxiety Inventory (T-AI), which assesses personality traits (anxiety reactions) and frequent emotional experiences (e.g., I feel happy). Each item is rated on a scale of 1-4, and the total S-AI and T-AI scale scores are calculated separately, with higher scores indicating more severe anxiety. In general, the STAI can be considered reliable and valid, with Cronbach’α coefficients of 0.82 and 0.83 for the 2 sub_scales.

Subjective Cognitive load (SCL) was assessed by the PAAS scale [

47], which consists of two main items, mental effort and task difficulty, both on a 9-point Likert scale, with 1 = very easy or least effort and 9 = very difficult or most effort. SCL was the sum of the two items. Subjects were asked to choose an appropriate number from 1 to 9 according to their feelings after completing the learning task. The Cronbach’α coefficient of the scale was 0.74.

Before the participants were assigned to stressful or non-stressful group, they were asked to finish behavioral inhibition/activation system scale (BIS-BAS scale) and the state-trait anxiety inventory (STAI). At the end of experiment, participants were asked to assess their state anxiety with the sub_scale of STAI (STAI-S) and the SCL of the micro-lecture (V_SCL) and quiz (T_SCL) with the PAAS scale. A total of five times V_SCL and five times T_SCL to completed.

3.1.3. Experimental procedure

Students used an online learning system.

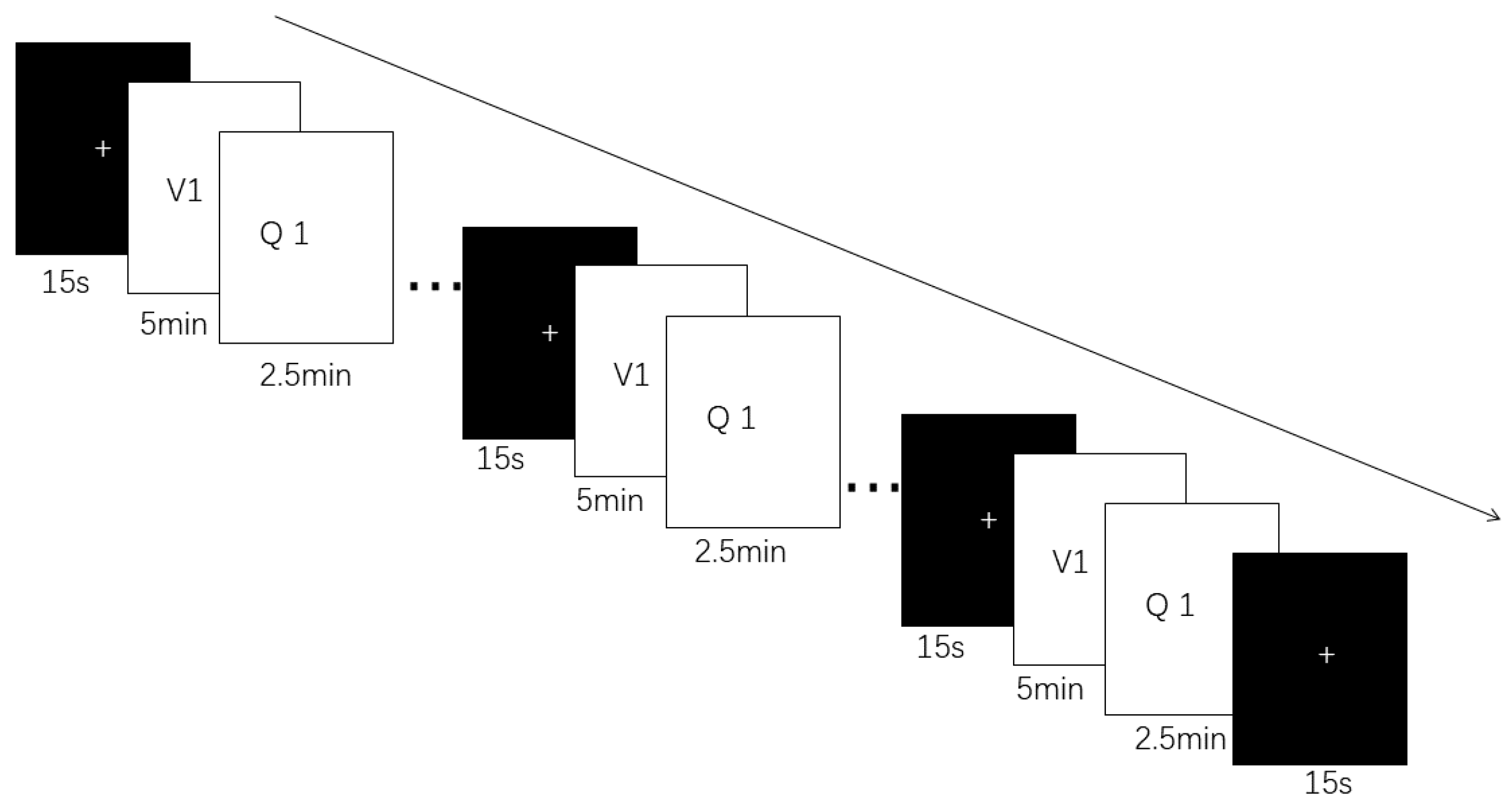

Figure 1 shows the learning process of micro-lectures and quizzes in alternating 15-seconds blocks of resting state.

Before the formal experiment, all participants were told that they would learn 2 economics and three physics micro-lectures, take a time-limited (2.5 min) quiz after each video. But for the participants who were assigned to stressful condition, they were told that the winner who got more score would be pained extra rewards at the end of the experiment. After the introduction, students were given a practice trial of a quiz to ensure that they understood the instructions. During the experiment, self-reported cognitive load were collected after each micro-lectures and quiz. The whole experiment took about 40 minutes.

3.1.4. Data analysis

The IBM SPSS 19.0 was used to analyze the behavioral data. t- test, repeated measures ANOVA, One-way ANOVA and ANCOVA were conducted to analyze the study outcomes.

3.2. Results

3.2.1. Demographic data

The competition and control group did not differ in term of gender (

χ2 = 0.001,

p = 0.971), age (

t =1.894,

df = 99,

p = 0.061) and years of education (

t = 1.057,

df = 99,

p = 0.293) (

Table 1).

3.2.2. Behavioral results

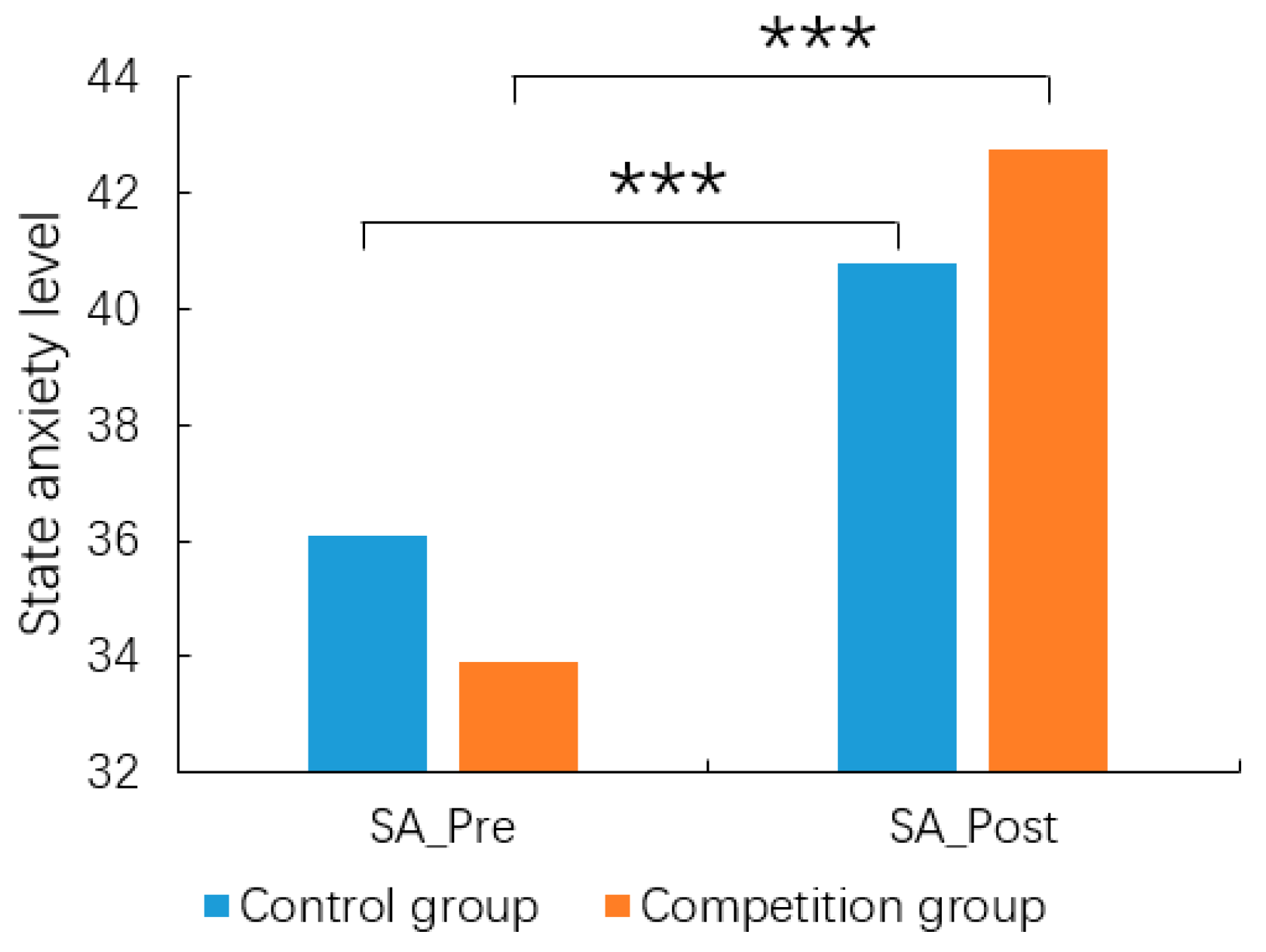

1. )TA and SA

For the STAI scale, there was no significant group difference for the TA (

t = -1.375,

df = 98,

p = 0.172). In terms of the SA, The results of repeated measures ANOVA showed significant differences in measurement time [

F(1, 98) = 61.42,

p < 0.001,

η2 = 0.385] and , with participant had a significantly higher SA at post-experiment (41.66 ± 9.75) than at pre-experiment (34.86 ± 8.07); the interaction between group and measurement time was significant [

F(1, 98) = 5.42,

p = 0.022,

η2 = 0.052]. Simple effects analysis revealed that the difference in SA between the pre- and post-experiment groups was not significant [

F(1,98) = 1.363,

p = 0.246;

F(1,198) = 1.229,

p = 0.270], but the SA of the post-experiment was significantly higher than the pre-experiment in both groups, in particular, this effect was larger in the competition group [Competition group:

F(1,98) = 51.665,

p < 0.001,

η2 = 0.345); control group:

F(1,98) = 15.175,

p < 0.001,

η2 = 0.134)](

Figure 2). This suggests that the competitive context setting did induce higher levels of SA.

2. )Test scores

The independent samples’t-test results showed that the total score of the competition group (43.52 ± 6.57) was significantly higher (t = -2.569, df = 99, p = 0.012) than the control group (39.80 ± 7.89).

3. )Subjective Cognitive Load

Although the competition group and the control group did not reach a statistically significant difference for SCL in the micro-lectures and quizzes, but in general, the control group (12.47 ± 2.45) had a higher SCL than the competition group (12.15 ± 2.48).

4). Correlations of BIS/BAS with anxiety, SCL, and test scores

Table 2 shows the correlations of BIS-BAS with anxiety, SCL and test score. Significant connections existed between BIS and Pre-experiment state anxiety, trait anxiety, and SCL during the quizzes (

r = 0.319,

p = 0.001;

r = 0.365,

p < 0.001;

r = 0.260,

p = 0.009), as well as between BASD and Pre-experiment state anxiety and TA (

r = -0.240,

p = 0.016;

r = -0.282,

p = 0.004).

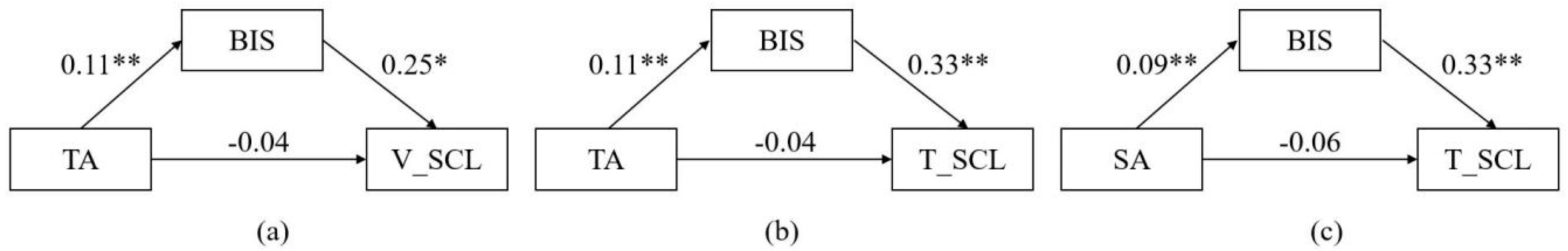

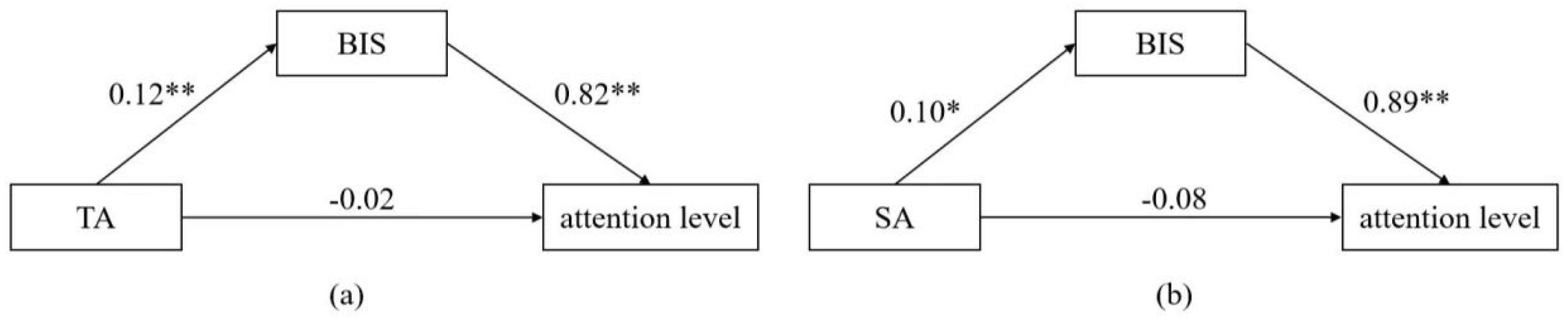

5. )The mediation effect of BIS on the relationship between anxiety and SCL

Based on the above correlation, our study found that BIS may play an important role in the influence of anxiety on SCL. Correlation analyses have shown significant correlations between BIS and TA, SA, and SCL in the quizzes. With BIS as the mediating variable, SA and TA as the independent variable, and SCL as the dependent variable, Bootstrap method was used to test the mediation effect of BIS. If the results of the mediation effect test did not contain 0, the mediation effect was significant. The results of mediation analysis are shown in

Figure 3. The indirect effect values of BIS in predicting SCL during watching micro-lectures and during doing quizzes by TA were 0.03, 95%CI = [0.00, 0.06] (

Figure 3a); 0.04, 95% CI = [0.01, 0.07] (

Figure 3b). The indirect effect of BIS on the SCL predicted by SA was 0.03, 95% CI = [0.01, 0.06] (

Figure 3c).

3.3. Discussion

Study 1 demonstrated the effects of peer competition on anxiety levels, SCL, and test scores of students at Ningbo University. We found a) for SA, the interaction between group and measurement time was significant. b) Compared to the control group, the competition group had better test scores. c) SCL was not significantly different between the two groups in the competition group and control group. d) BIS plays a mediation role in the effects of TA and anxiety SA on SCL.

4. Study 2

Since it is very important for students to focus their attention on the learning task, the level of attention is also one of the important objective indicators of learning effectiveness [

42]. Study 2 in a specific organization would enable us to collect objective data (attention level) on learning process, thereby allowing us to test the relationships among competition, anxiety test score and attention level in actual MOOC learning. Specifically, Study 2 recorded EEG data on subjects’ attention levels based on Study 1. In addition, Study 1 was conducted used a sample from Ningbo University, but the student population in one area is not representative of the entire student population. It was therefore necessary to determine in Study 2 whether the pattern of results differed in other groups (Beijing Normal University).

4.1. Method

4.1.1. Participants

Participants of the experiment were 42 undergraduate and postgraduate students who major in humanities and social sciences (excluded economics) from Beijing. 22 of them were assigned to 11 pairs for the competition condition (stressful condition). For each pair the students, they must participate the experiment together and learning the MOOC materials synchronously. The rest 20 students were assigned to the control condition (nonstressful condition) and they completed the experiment by themselves.

Students were compensated for this experiment. While for the control group, all students got pained with 60 Ren Min Bi (RMB) after complete the experiment. For the competition group, they were told that the one who achieved higher score will get extra 20 RMB as reward. In Study 2, both the control group and the competition group received higher reward amounts than in Study 1, which was due to two main considerations. On the one hand, this is because of the inherent differences in participants’ remuneration between Beijing and Ningbo; Beijing is the capital city of China and it tends to have higher reward levels than other cities. On the other hand, participants who participate in EEG data collection are also usually required to pay higher fees. Both the students signed informed consent forms after a full explanation of the study procedure.

4.1.2. Materials and Tasks

Self-reported scales

The same self-reported scales used in study 1 was used in study 2.

4.1.3. Experimental procedure

The same materials and procedure used in study 1 was used in study 2, but we collected EEG data of students on the basis of Study 1. Students used an online learning system.

Figure 1 shows the learning process of micro-lectures and quizzes in alternating 15-seconds blocks of resting state. A brainwave detecting headset was used during the experiment to collect EEG data.

4.1.4. EEG data acquisition

EEG was recorded by MindSet headsets during the learning process. The EEG included 8 bands of waves: delta (0.5-2.75 Hz), theta (3.5-6.75 Hz), low-alpha (7.5-9.25 Hz), high-alpha (10-11.75 Hz), low-beta (13-16.75 Hz), high-beta (18-29.75 Hz), low-gamma (31-39.75 Hz), and mid-gamma (41-49.75 Hz). Data were automatically corrected for eye blinks and ocular artifacts.

4.1.5. Data analysis

The IBM SPSS 19.0 was used to analyze the behavioral and EEG data. t-test, repeated measures ANOVA, One-way ANOVA and ANCOVA were conducted to analyze the study outcomes.

For the EEG data, the first 60 seconds were discarded and the rest of the data were averaged at every time point (about one second) and then smoothed with a 15-second sliding window (86.67% overlap between successive windows). ANOVA was used to analyze both the average attention level during learning. Finally, we calculated the rate of change (ROC) in attention as the difference in attention level of one time point (a) and the beginning period (the first 15 seconds) of the next time point (b) divided by b. That is, ROC= (a-b)/b.

4.2. Results

4.2.1. Demographic data

The competition and control group did not differ in term of gender (

χ2 = 2.636,

p = 0.104), age (

t = 1.891,

df = 40,

p = 0.066) and years of education (

t = 1.472,

df = 40,

p = 0.149) (

Table 3).

4.2.2. Behavioral results

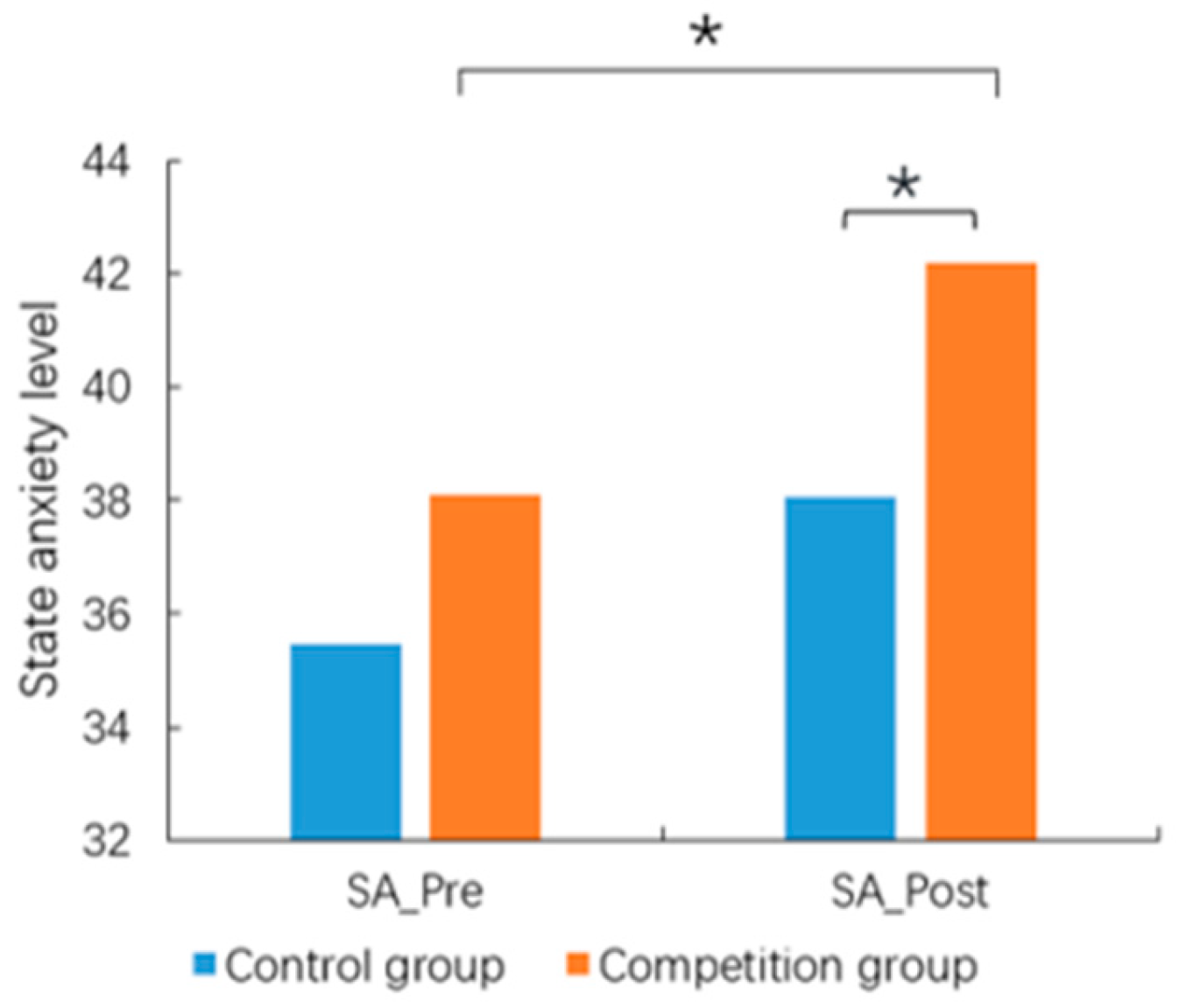

1. )TA and SA

For the STAI scale, there was no significant group difference for the TA (

t = -1.335,

df = 39,

p = 0.190). In terms of the SA, there was no significant group difference of the SA before the experiment. While the SA of the competition group (42.19 ± 9.95) was significantly higher (

t = -2.301,

p = 0.032) after the experiment than that before the experiment(38.10 ± 8.82), and the SA of the competition group was significantly higher (

t = -1.619,

p = 0.046) than that of the control group(38.05 ± 5.77) after the experiment, but for the control group, there was no difference of the SA before and after the experiment (

Figure 4). The results displayed that the competition conditions did induce higher SA.

2. )Test scores

The total score of the competition group (43.27 ± 5.45) was significantly lower (t = 2.117, df = 39, p = 0.041) than the control group (46.70 ± 5.01).

3. )Subjective Cognitive Load

Similar to Study 1, the independent samples t-tests of SCL showed that the difference in total SCL, the SCL of watching micro-lectures, and the SCL of doing quizzes between the two groups did not reach the level of significance. However in the overall, the control group (10.48 ± 2.21) had a lower SCL than the competition group (10.96 ± 2.18).

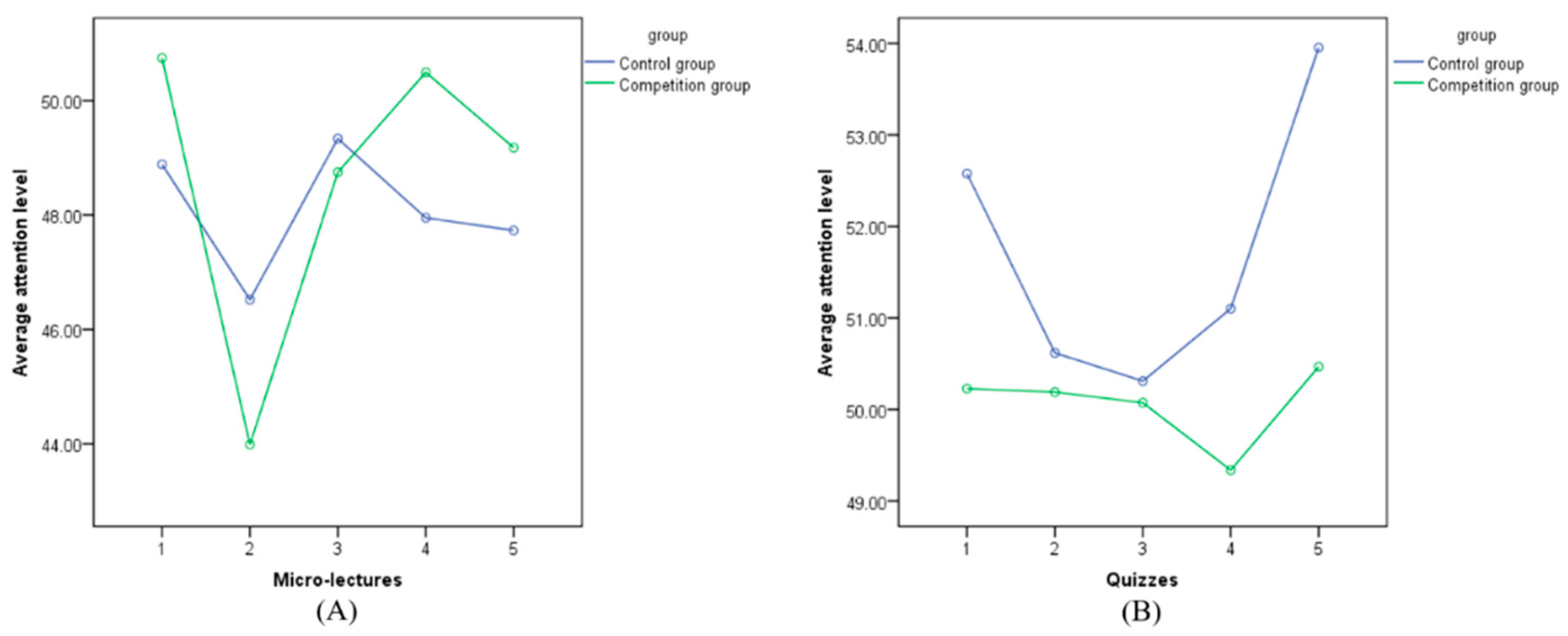

4. )Attention level

Attention level was assessed via by EEG index. One-way ANOVA

showed that the mean attention level of the competition group was significantly lower than that of the control group (

F(1, 4706) = 14.348,

p < 0.001,

η2 = 0.03). The results of repeated measures ANOVA showed that the main effect of group was significant for both micro-lectures and quizzes, and the interaction effect of time and group was also significant [Micro-lectures: main effect of group:

F(4,477) =312.148,

p < 0.001,

η2 = 0.724; Interaction effect between group and time:

F(4,477) = 97.431,

p < 0.001,

η2 = 0.450; Test: group main effect:

F(4,339) = 71.679,

p < 0.001,

η2 = 0.458; Interaction effect between group and time:

F(4,339) = 50.037,

p < 0.001,

η2 = 0.371](

Figure 5A,B). Pairwise comparisons showed that the attention level of the competition group was significantly lower than that of the control group in the second and third micro-lecture, but the competition group was significantly higher than that of the control group in the remaining three times. Furthermore, the competition group had lower attention levels compared to the control group, especially when doing the last quiz. And the change pattern of attention level during quizzes was quite similar for the two groups except for the forth quiz, while the competition group showed even lower attention level, but higher for the control group.

5). Correlations of BIS/BAS with anxiety, SCL, attention level and test score

Table 4 shows the correlations of BIS-BAS with anxiety, mean attention level, SCL and test score. Significant connections existed between BIS and Pre-experiment state anxiety, TA, and mean attention level (

r = 0.373,

p = 0.016;

r = 0.466,

p = 0.002;

r = 0.464,

p = 0.004), as well as between BASD and TA, SCL during the quizzes (

r = -0.331,

p = 0.035;

r = -0.359,

p = 0.025). The correlation of BIS with SA and TA was relatively stable in both studies.

6. )The mediation effect of BIS on the relationship between anxiety and attention level

Our study found that BIS may play an important role in the influence of anxiety on attention level. Correlation analyses have shown significant correlations between BIS and TA, SA, and attention level. With BIS as the mediating variable, SA and TA as the independent variable, and attention level as the dependent variable, we used the Bootstrap method to test the mediation effect of BIS. The results of the mediation analysis are shown in

Figure 6. The indirect effect values of the BIS in predicting mean attention level by TA was 0.10, 95% CI = [0.03, 0.21]. The indirect effect of the BIS on the mean attention level predicted by SA was 0.09, 95% CI = [0.01, 0.20].

4.3. Discussion

Study 2 found that the effects of peer competition on anxiety levels, SCL, attention level and test scores of students at Beijing Normal University. We found a) SA was significantly higher in the competition group than in the control group. b) the competition group showed lower test score than the control group. c) SCL was not significantly different between the two groups in the competition group and control group. d)The average attention level of the competition group was significantly lower than that of the control group. e) BIS plays a mediation role in the influence of TA and SA on attention level.

5. The comparison for two universities

It seemed like that the effects of competition on the learning process and learning outcomes in Study 1 and Study 2 was inconsistent, and in order to further compare the results of the two studies, we also treated university as the independent variable for the analysis, and the results are as follows:

1. )TA and SA

For the TA, ANOVA showed that there was no significant university differences, group differences, and interaction. Repeated measures ANOVA revealed a significant main effect of SA measurement time (F(1,137) = 40.871, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.230), with post-experiment SA (40.89 ± 0.87) significantly higher than pre-experiment (35.82 ± 0.75); the interaction of measurement time and university was significant (F(1,137) = 4.731, p = 0.031, η2 = 0.033), and simple effects analysis found that the difference in SA between two universities in pre- and post-experiment was not significant, SA_post was significantly higher than in the pre-experiment at two universities, especially in Ningbo University [Ningbo University: F(1,137) = 63.143, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.315); Beijing Normal University: F(1,137) = 6.271, p = 0.013, η2 = 0.044)]. It is illustrated that students at Ningbo University generally showed more anxiety compared to students at Beijing Normal University.

2. )Test scores

The results of the ANOVA indicated that the main effect of group was not significant (F(1,137) = 0.013, p = 0.908), the main effect of university was significant (F(1,137) = 6.657, p = 0.011, η2 = 0.046), and that the test scores of the students from Beijing Normal University (44.86 ± 5.53) were significantly higher than those of the students from Ningbo University (41.94 ± 6.88). The interaction between group and university was also significant (F(1,137) = 7.781, p = 0.006, η2 = 0.054). Simple effects analysis found that Ningbo University’s competitive group was significantly higher than the control group (F(1,137) = 6.171, p = 0.014, η2 = 0.043), Instead, the control group scored higher than the competition group in Beijing Normal University (F(1,137) = 2.970, p = 0.087, η2 = 0.021), and the control group at Beijing Normal University scored significantly higher than the control group at Ningbo University (F(1,137) = 13.704, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.091). This illustrates the fact that students at the two universities belong to two different groups in nature, and that competition affects students test scores differently, with competition boosting performance at Ningbo University, but lowering performance at Beijing Normal University.

3. )Subjective Cognitive Load

The results of the ANOVA on the total SCL scores showed a significant main effect of university (F(1,137) = 12.563, p = 0.001, η2 = 0.084), with students at Ningbo University having a significantly higher SCL (12.31 ± 0.24) than those at Beijing Normal University (10.72 ± 0.38). Separate analyses of ANOVA for V_SCL and T_SCL similarly revealed a significant main effect for the university only (V_SCL: F(1,137) = 13.792, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.091; T_SCL: F(1,137) = 10.228, p = 0.002, η2 = 0.069). Again, this illustrates the heterogeneity of the two populations.

6. General Discussion

The current studies explored the effects of peer competition on learning process and outcome based on MOOC learning contexts. We found that (a) competitive conditions significantly increased individuals’ SA; (b) there were differences in the effects of competition on test scores, with competition facilitating students’ performance in Study 1, but hindering students’ performance in Study 2; (c) although the effect of competition on the SCL of students did not reach a significant level, it showed different trends in the two studies, (d) lower levels of attention in the competition group compared to the control group; and (e) the BIS fully mediates between anxiety and SCL in Study 1 and fully mediates between anxiety and attention levels in Study 2.

The current results suggest that competition increases individuals’ state anxiety, and a direct comparison of the data from the two universities also showed that higher SA was induced at Ningbo University compared to Beijing Normal University. Both studies found that competition induces SA in individuals, which is consistent with previous studies [648], competitive situations trigger anxiety in individuals [

49].

Interestingly, we found that participants in Study 2 elicited lower SA compared to participants in Study 1. This may be due to the different levels of universities chosen for the two studies, where Beijing Normal University, as a “double first-class” university, would have a higher quality of students compared to Ningbo University [

43]

.The effect of competition seems to be dynamic for different individuals. The result was consistent with previous findings that students with high ability are better at coping with competition emotionally and show a lower degree of anxiety than their peers with low ability [

50,

51]

. This may be because students with high ability have more confidence to deal with the examination task, better coping strategies and stronger learning ability. Thus, the stress and anxiety they felt during the examination were reduced [

52]

.

The effect of competition on students’ test scores yielded different results in Study 1 and Study 2. Study 1 found that the competitive group had higher test scores than the control group, while Study 2 found that the control group was higher. Direct comparison revealed that students at study 2 scored higher. Why does competition appear to have a different effect on learning outcomes? This may be due to the fact that anxiety may have more severe consequences on the performance of high achieving students. For example, Researchers found that examined the relationship between anxiety and test scores in first and second graders in the US and found that the negative correlation between anxiety and test scores was only present in students with high working memory, or the kind of child who has the greatest potential for high achievement [

53]. OECD also reported that, compared to low ability students, high ability students’ anxiety is more strongly associated with lower test scores [

54]. Another possible explanation is that the competition situation induced different levels of anxiety in the two studies, with the competition group in Study 1 having moderate levels of anxiety. According to the Yerkes-Dodson law, appropriate anxiety or stress can promote and enhance productivity. Given the different effects that competition can have on different groups of students, teachers need to be careful about using this strategy in real classroom situations and use different instructional strategies for different students.

Although there were no significant differences in SCL between the competition and control groups in both Study 1 and Study 2, they exhibited different trends, direct comparisons also suggested that students at Ningbo University would report higher cognitive loads. The SCL of the control group in Study 1 was relatively higher, whereas the SCL reported by the competition group in Study 2 would be relatively higher. This paradox can be explained by ACT, which examines learning and problem-solving primarily from attention control. Competition-induced anxiety disrupts the balance between the two attention systems, weakening the goal-driven top-down attention system and enhancing the stimulus-driven bottom-up attention system [

28]. In Study 1, the balance of the attention system in the competitive group was broken, and on the contrary, the control group could invest more cognitive effort in the learning process [

55], whereas in Study 2, the competitive group had sufficient resources to invest in the learning process due to the relatively low level of anxiety induced by them. High cognitive load is detrimental to learning [

56], it causes rapid fatigue, reduced flexibility, and frustration, and is an important cause of decreased performance [

57]. Therefore, we should find ways to reduce students’ load in the learning process so that they can have sufficient cognitive resources to complete the learning task itself.

In order to perform optimally in competitive situations, students must learn to cope with competition-induced emotional responses, such as anxiety or worry, and must focus attention on current task-relevant information [

58]. Our EEG data in Study 2 found lower levels of student attention under competitive conditions, which is consistent with the consensus of previous studies [

59,

60]. Competition means increased stress and anxiety. According to ACT, anxiety impairs individuals’ attentional control, making them less able to focus on the task at hand and more easily distracted. Future research needs to further investigate how to maintain individual attention levels in competitive situations, which in turn can provide more strategies to improve students’ performance in real-world learning situations.

The current findings indicate that in Study 1, SA and TA influenced students’ SCL when watching micro-lectures and doing quizzes by activating individuals’ BIS, and TA could also influence SCL when doing quizzes by activating individuals’ BIS; while in Study 2, this mediating effect was not significant, However, SA and TA could affect students’ attention levels when watching micro-lectures and taking quizzes by activating BIS. The reason that the indirect effect of anxiety on cognitive load was not significant in Study 2 may be due to the differences between the two samples, with the excellent students being more adept at handling the task and reducing the cognitive load [

61], whereas the students of average ability may have been completing the task with a potentially greater cognitive load [

62]. This suggesting an important role for the BIS in the relationship between anxiety and cognitive load, attention levels. Researchers have found that the BIS/BAS can provide an explanatory framework for the relationship between motivation and behaviors [

63,

64]. According to Gray’s theory, BIS is closely related to negative emotions [

25,

27]. In addition, the BIS/BAS involves motivational tendencies [

65], which have been shown by researchers to have a relationship with students’learning [

66,

67]. For students who are in a competitive atmosphere every day, the risk of failure in comparison with others is always present, so they feel anxious about their academic performance, and when this emotion reaches a certain level it activates the BIS, which in turn affects the individual’s cognitive load and attention level. This result reminds our educators to pay attention to students’ emotions and motivation in practice and to minimize unnecessary comparisons so that students can focus more on the learning process itself.

7. Limitations and future research

Several limitations of this study need to be noted. First, in order to control the experimental variables strictly, we used micro-lectures rather than actual online classroom instruction. Future research could explore this in an actual online classroom, but it is important to control for the effects of other extraneous variables on the results. Second, due to some limited experimental conditions, the sample size was not large enough in our studies, especially in Study 2. To improve the accuracy of the conclusions drawn, future studies may consider increasing the sample size or using alternative research methods to validate the findings of the study. Third, some of the results of this study were measured using a self-statement scale, and more objective measurement methods could be used in the future. As a final point, our studies simply compared data from different groups, and subsequent research could systematically explore the effects of competition on learning in different groups, such as students of different abilities or students from different cultural backgrounds.

8. Conclusions

This micro-lecture-based study found that competitive situations tended to induce anxiety, which could further impair attention and increase SCL through BIS, and finally influence learning performance.

Funding

This research is funded by the project “the Research on Calligraphy” (Project No. 23YJCZH020) from the MOE (Ministry of Education in China) Project of Humanities and Social Sciences, the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (Project No. 2018M631365 and No. 2019T120060) and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Provincial Universities of Zhejiang (Project No. SJWY2022009).

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was approved by the Research Ethics Board of Ningbo University.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all individual adult participants included in the study; The authors promise that the data is available when required and will make our data available in an open repository as required.

Data Availability Statement

We promise that the data is available when required and permission to reproduce material from other sources.

Acknowledgments

We thank all graduate research assistants who helped with data collection.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare they have no conflict of interest.

References

- Chang, B., Chuang, M. T., & Ho, S. Understanding students’ competition preference in multiple-mice supported classroom. Journal of Educational Technology & Society 2013, 16, 171–182.

- Kc, R. P., Kunter, M., & Mak, V. The influence of a competition on noncompetitors. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2018, 115, 2716–2721.

- Sun, Z. , Bai, T., Yu, W., Zhou, J., Zhang, M., and Shen, M. Attentional bias in competitive situations: winner does not take all. Front. Psychol. 2015, 6, 1469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Posselt, J. R. , and Lipson, S. K. Competition, anxiety, and depression in the college classroom: variations by student identity and field of study. J. Coll. Stud. Dev. 2016, 57, 973–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epstein, J. A. , and Harackiewicz, J. M. Winning is not enough: the effects of competition and achievement orientation on intrinsic interest. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 1992, 18, 128–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quach, A. S. , Epstein, N. B., Riley, P. J., Falconier, M. K., and Fang, X. Effects of parental warmth and academic pressure on anxiety and depression symptoms in Chinese adolescents. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2015, 24, 106–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pekrun, R. Progress and open problems in educational emotion research. Learn. Instr. 2005, 15, 497–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, J. A. The campus as a frog pond: an application of the theory of relative deprivation to career decisions of college men. Am. J. Sociol. 1966, 72, 17–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pekrun, R. The control-value theory of achievement emotions: assumptions, corollaries, and implications for educational research and practice. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 2006, 18, 315–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ames, C. , and Archer, J. Achievement goals in the classroom: students’ learning strategies and motivation processes. J. Educ. Psychol. 1988, 80, 260–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X. H. , & Yang, B. Z. Why competition may discourage students from learning? A behavioural economic analysis. Education Economics 2003, 11, 117–128. [Google Scholar]

- Kai, J. The origin and consequences of excess competition in education: A mainland Chinese perspective. Chinese Education & Society 2012, 45, 8–20. [Google Scholar]

- Schiefele, U. , Schaffner, E., Moller, J., & Wigfield, A. Dimensions of reading motivation and their relation to reading behavior and competence. Reading Research Quarterly 2012, 47, 427–463. [Google Scholar]

- Nebel, S. , Schneider, S., & Rey, G. R. From duels to classroom competition: Social competition and learning in educational videogames within different group sizes. Computers in Human Behavior 2016, 55, 384–398. [Google Scholar]

- Lam, S. , Yim, P., Law, J. S. F., & Cheung, R. W. Y. The effects of competition on achievement motivation in Chinese classrooms. British Journal of Educational Psychology 2004, 74, 281–296. [Google Scholar]

- Tauer, J. M. , & Harackiewicz, J. M. The effects of cooperation and competition on intrinsic motivation and performance. Journal of personality and social psychology 2004, 86, 849. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Agasisti, T. , & Murtinu, S. ‘Perceived’ competition and performance in Italian secondary schools: New evidence from OECD—PISA 2006. British Educational Research Journal 2012, 38, 841–858. [Google Scholar]

- Akpinar, M. , Del Campo, C., & Eryarsoy, E. Learning effects of an international group competition project. Innovations in Education and Teaching International 2015, 52, 160–171. [Google Scholar]

- He, L. X. , Zhang, Q., and Wang, C. K. The relationship between competition-cooperation and academic achievement: a mediator role of academic self-concept. Psychol. Explor. 2011, 31, 172–175. [Google Scholar]

- Burguillo, J. C. Using game-theory and competition-based learning to stimulate student motivation and performance. Comput. Educ. 2010, 55, 566–575. [Google Scholar]

- Olitsky, S. The role of fictive kinship relationships in mediating classroom competition and supporting reciprocal mentoring. Cult. Stud. Sci. Educ. 2011, 6, 883–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craig, G. J. (1967). The effect of distribution of rewards, grade level and achievement level on small group applicational problem solving.

- Pesout, O. , and Nietfeld, J. The impact of cooperation and competition on metacognitive monitoring in classroom context. J. Exp. Educ. 2020, 89, 237–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, H. B. An investigation on the correlation between junior middle school students’ class environment and academic achievement. Psychol. Sci. 2009, 32, 742–744. [Google Scholar]

- Gray, J. A. (1987). The neuropsychology of emotion and personality.

- Gray, J. A. Brain Systems That Mediate Both Emotion and Cognition. Cognition & Emotion 1990, 4, 269–288. [Google Scholar]

- Carver, C. S. , & White, T. L. Behavioral inhibition, behavioral activation, and affective responses to impending reward and punishment: the BIS/BAS scales. Journal of personality and social psychology 1994, 67, 319. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Eysenck, M. W., Derakshan, N., Santos, R., & Calvo, M. G. Anxiety and cognitive performance: attentional control theory. Emotion . 2007, 7, 336. [PubMed]

- Berggren, N. , & Derakshan, N. Attentional control deficits in trait anxiety: Why you see them and why you don’t. Biological Psychology 2013, 92, 440–446. [Google Scholar]

- Derakshan, N. , Smyth, S., & Eysenck, M. W. Effects of state anxiety on performance using a task-switching paradigm: An investigation of attentional control theory. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review 2009, 16, 1112–1117. [Google Scholar]

- Rezaei, F. , Hosseini Ramaghani, N. A., & Fazio, R. L. The effect of a third party observer and trait anxiety on neuropsychological performance: The Attentional Control Theory (ACT) perspective. The Clinical Neuropsychologist 2017, 31, 632–643. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, C. H. The impacts of peer competition-based science gameplay on conceptual knowledge, intrinsic motivation, and learning behavioral patterns. Educational Technology Research and Development 2019, 67, 179–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gotardi, G. C. , Polastri, P. F., Schor, P., Oudejans, R. R., van der Kamp, J., Savelsbergh, G. J.,... & Rodrigues, S. T. Adverse effects of anxiety on attentional control differ as a function of experience: A simulated driving study. Applied ergonomics 2019, 74, 41–47. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lazaro, M. J. , Yun, M. H., & Kim, S. Stress-level and attentional functions of experienced and novice young adult drivers in intersection-related hazard situations. International Journal of Industrial Ergonomics 2022, 90, 103315. [Google Scholar]

- Ventura, R. B. , Richmond, S., Nadini, M., Nakayama, S., & Porfiri, M. Does winning or losing change players’ engagement in competitive games? Experiments in virtual reality. IEEE Transactions on Games 2021, 13, 23–34. [Google Scholar]

- Van Nuland, S. E. , Roach, V. A., Wilson, T. D., & Belliveau, D. J. Head to head: The role of academic competition in undergraduate anatomical education. Anatomical sciences education 2015, 8, 404–412. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Müller, F. , & Cañal-Bruland, R. Interindividual differences in incentive sensitivity moderate motivational effects of competition and cooperation on motor performance. PloS one 2020, 15, e0237607. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. (2016). Innovating education and educating for innovation: The power of digital technologies and skills. OECD Publishing.

- U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics. (2019). Digest of Education Statistics 2019.

- UNESCO Institute for Statistics. (2020b). UNESCO-UNICEF-World Bank Survey on National Remote learning during the global school lockdown: Multi-country lessons Education Responses to COVID-19 School Closures.

- Greenhow, C., Graham, C. R., & Koehler, M. J. Foundations of online learning: Challenges and opportunities. Educational Psychologist . 2022, 57, 131–147.

- Berman, M. G. , Jonides, J., & Kaplan, S. The cognitive benefits of interacting with nature. Psychological science 2008, 19, 1207–1212. [Google Scholar]

- 43. Ministry of Education of the People's Republic of China. (1999). Learning reference materials for the Action Plan for Education Revitalization in the 21st Century. Beijing Normal University Press.

- Bloom, B.S.; Krathwohl, D.R. The Classification of Educational Goals. In Taxonomy of Educational Objectives: Handbook I, Cognitive Domain; Longmans, Green: New York, NY, USA, 1956. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y. Z. , Zhang, Y., Jiang,Y., Li, H., Mi, S., Yi, G. J.,...& Jiang, Y. Reliability and validity of the Chinese version of the Behavioral Inhibition/Activation Scale. Chinese Mental Health Journal 2008, 22, 613–616. [Google Scholar]

- Spielberger, C. D. (1983). State-trait anxiety inventory for adults.

- Paas, F. G. Training strategies for attaining transfer of problem-solving skill in statistics: a cognitive-load approach. Journal of educational psychology 1992, 84, 429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatfield, B. D. , Costanzo, M. E., Goodman, R. N., Lo, L. C., Oh, H., Rietschel, J. C.,... & Haufler, A. The influence of social evaluation on cerebral cortical activity and motor performance: A study of “Real-Life” competition. International Journal of Psychophysiology 2013, 90, 240–249. [Google Scholar]

- Cerin, E. , & Barnett, A. Predictors of pre-and post-competition affective states in male martial artists: a multilevel interactional approach. Scandinavian journal of medicine & science in sports 2009, 21, 137–150. [Google Scholar]

- Ozturk, M. , & Debelak, C. Affective benefits from academic competitions for middle school gifted students. Gifted Child Quarterly 2008, 31, 48–54. [Google Scholar]

- Pollack, C., Wilmot, D., Centanni, T. M., Halverson, K., Frosch, I., D'Mello, A. M., Romeo, R. R., Imhof, A., Capella, J., Wade, K., Al Dahhan, N. Z., Gabrieli, J. D. E., & Christodoulou, J. A. (2021). Anxiety, Motivation, and Competence in Mathematics and Reading for Children With and Without Learning Difficulties. Frontiers in psychology 2021, 12, 704821.

- Putwain, D. W. , & Daly, A. L. Do Different Factors Predict Different Types of Test Anxiety? Journal of Psychoeducational Assessment 2014, 32, 167–177. [Google Scholar]

- Ramirez G, Gunderson EA, Levine SC and Beilock SL Math anxiety, working memory, and math achievement in early elementary school. Journal of Cognition and Development 2013, 14, 187–202. [CrossRef]

- OECD (2013a) PISA 2012 Results: Ready to Learn: Students' Engagement, Drive and Self-Beliefs (Volume III). Paris: OECD Publishing.

- er Vrugte, J., de Jong, T., Vandercruysse, S., Wouters, P., van Oostendorp, H., & Elen, J. How competition and heterogeneous collaboration interact in prevocational game-based mathematics education. Computers & Education. 2015; 89, 42–52.

- Sweller, J. (2011). Cognitive load theory. New York: Academic Press.

- Ming, D. , Ke, Y., He, F., Zhao, X., Wang, C., Qi, H.,... & Chen, S.-G. Research on mental workload detection and adaptive automation system based on physiological signals: a 40-year review and recent progress. Journal of Electronic Measurement and Instrumentation 2015, 29, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts, L. J. , Jackson, M. S., & Grundy, I. H. Choking under pressure: Illuminating the role of distraction and self-focus. International Review of Sport and Exercise Psychology 2019, 12, 49–69. [Google Scholar]

- Bar-Haim, Y. , Lamy, D., Pergamin, L., Bakermans-Kranenburg, M. J., & Van Ijzendoorn, M. H. Threat-related attentional bias in anxious and nonanxious individuals: a meta-analytic study. Psychological bulletin 2007, 133, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Schwabe, L. , & Wolf, O. T. Emotional modulation of the attentional blink: Is there an effect of stress? Emotion 2010, 10, 283–288. [Google Scholar]

- Hambrick, D. Z. , & Oswald, F. L. Does domain knowledge moderate involvement of working memory capacity in higher-level cognition? A test of three models. Journal of Memory and Language 2005, 52, 377–397. [Google Scholar]

- Koning, B. , & Schoot, M. Becoming Part of the Story! Refueling the Interest in Visualization Strategies for Reading Comprehension. Educational Psychology Review 2013, 25, 261–287. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan, R. M. A special issue on approach and avoidance motivation. Motivation and Emotion. Special issue: Approach/Avoidance 2006, 30, 103–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, H. W. , Worth, K. A., Baldwin, A. S. and Rothman, A. J. The effect of approach and avoidance referents on academic outcomes: A test of competing predictions. Motivation and Emotion. Special issue: Approach/Avoidance 2006, 30, 157–164. [Google Scholar]

- Heimpel, S. A. , Elliot, A. J., & Wood, J. V. Basic personality dispositions, selfesteem, and personal goals: An approach-avoidance analysis. Journal of Personality 2006, 74, 1293–1320. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- van Beek, I. , Kranenburg, I. C., Taris, T. W., & Schaufeli, W. B. BIS- and BAS-activation and study outcomes: A mediation study. Personality and Individual Differences 2013, 55, 474–479. [Google Scholar]

- Hou, T. The Influence of Behavioral Inhibition/Activation System on Procrastination—Mediating Roles of Self-Control. Advances in Psychology 2021, 11, 591–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).