1. Introduction

The syndrome “Basses Richesses” (SBR) is a bacterial disease in sugar beet (

Beta vulgaris ssp.

vulgaris) resulting in low sugar content of the beet root. In Germany, SBR was first reported in 2008 in the region of Heilbronn, Baden-Württemberg [

1]. Since its first detection, it further spread across Germany and remains of high economic importance [

1].

This disease is associated with the two vector-transmitted bacteria ‘

Candidatus Arsenophonus phytopathogenicus’

, hereafter called ‘CAp’, and ‘

Candidatus Phytoplasma solani’, hereafter called ‘CPs’ [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5]. CPs is a cell wall-lacking procaryotic microorganism of the provisional genus ‘

Candidatus Phytoplasma’ within the class Mollicutes. This vector-born pathogen colonizes the plant phloem and is associated with numerous plant diseases [

6]. CAp belongs to the γ subdivision of the class Proteobacteria [

7]. Like CPs, the bacterium inhabits the plant phloem and is vector-transmitted by planthoppers of the family Cixiidae (Hemiptera) [

8]. The only confirmed vector of SBR in sugar beet in Europe is the planthopper

Pentastiridius leporinus [

3,

4,

9].

In 2023, during the sugar beet harvest in Germany, a worsened situation was reported in SBR affected regions, where roundabout 60,000 ha of sugar beet fields have been infested by

P. leporinus and infected by SBR, and another 10,000 ha in Southwest Germany and 4,000 ha in Saxony-Anhalt with an increased incidence of rubbery taproots and the Stolbur phytoplasma in symptomatic beet roots [

10,

11,

12]. The symptoms of the latter resembled to those of rubbery taproot disease in sugar beet associated with CPs in Serbia, transmitted by the planthopper

Hyalesthes obsoletus [

13].

Recently, an increasing occurrence of potato plants (

Solanum tuberosum) and tubers showing Stolbur-like symptoms such as yellowing, air tubers and rubbery tubers, but also with symptoms of bacterial wilt, has been reported for about 8,000 ha of potato grown in southwest Germany [

12,

14,

15]. These symptoms are similar to such caused by CPs in potato in the Mediterranean and its northern range border in southwest Germany and north-east France (Alsace), where the Stolbur disease is also transmitted by the planthopper

H. obsoletus [

6,

16].

The epidemiologically important vector for SBR in sugar beet in Germany and other countries,

P. leporinus [

2,

3,

4], has been reported in potato fields in Germany firstly in 2023, associated with yellowing and wilting symptoms [

17]. A recent study by Behrmann et al. [

15] showed that nymphs of

P. leporinus fed and transmitted CAp to potato, but the role of adults in transmitting the two SBR-associated pathogens to potato has not been studied. In contrast to relatively immobile nymphs feeding below-ground, adults of this vector can fly and have a higher potential for migration, distributing the pathogens over longer distances.

To study whether potato may represent a potential feeding host for

P. leporinus, especially in the vicinity of sugar beet - and if so, whether the vector can complete its entire lifecycle on potato, like it does on sugar beet, choice and development experiments were performed in the presented study. Furthermore, transmission experiments were carried out to elucidate whether adults of

P. leporinus are capable to transmit one or both pathogens to potato. To quantify the CAp and CPs titer in plants and insects TaqMan qPCR assays were performed employing a

hsp20 gBlock [

18] and a 16S rDNA-derived gBlock (this study). We also determined the limit of detection for CPs in potato and sugar beet.

2. Materials and Methods

Field collection of P. leporinus

Planthoppers used in transmission trials and choice experiments were collected end of June 2023 with sweeping nets at two different locations in Southwestern Germany. The first site was a potato field near Bobenheim-Roxheim (49.5654220, 8.3914040), the second site was a sugar beet field near Kirschgartshausen (49.5846780, 8.4544680). The insects were stored separately in insect cages for transport and identified by morphological traits [

19]. Only

P. leporinus specimen were used for the experiments, which started the same day.

Transmission experiments

Adults of

P. leporinus caught in potato field were chosen for the transmission trial to five potato (

Solanum tuberosum) varieties, namely ‘Lilly’, ‘Merle’, ‘Belana’, ‘Juventa’ and ‘Gala’. Certified planting tubers were used for the transmission trials. Individual tubers were planted the 9

th of June 2023 in pots and grown in an insect proof greenhouse at 22°C. 14 days after germination, five plants per variety were chosen for the transmission trials, as well as one control plant. All shoots but one were removed and a foam plate was placed on top of the planting pot to cover the substrate. The shoots were 25-30 cm in height. An acrylic cylinder (height 35 cm, diameter 13 cm) covered with a mesh was placed two centimeters deep inside the substrate around the foam plate as a barrier. Ten planthoppers were transferred to each transmission cylinder according to Jarausch et al. [

20]. The planting pots with the cylinders were placed in a climate chamber with conditions slightly different to rearing protocols (22°C, 55% relative humidity, and light/dark cycle of 18/6 h) [

21,

22]. The transmission experiments lasted for five consecutive days. Individuals that died during this period were removed and stored at -20°C for further analysis, as well as the remaining individuals after the end of the transmission trial. Then, the cylinders were removed, and all plants were placed into an insect-proof greenhouse. They were monitored for symptoms on a regular basis. Fifteen weeks post inoculation, all tubers per pot were harvested and cleaned with water. Three tubers per plant were tested individually for the presence of CPs and CAp by separate TaqMan assays.

Choice /development trial

P. leporinus adults caught in a sugar beet field were subjected to a two-step choice trial to investigate host plant preferences and to determine the development speed on both host plants of potentially new emerging offspring of the planthoppers. In the first step, each 35 adults were transferred to four net cages containing one sugar beet plant (variety ‘Vasco’, average height of 10 cm) and one potato plant (variety ‘Gerona’, average height of the shoots 20-30 cm). The 3L-pots were filled with potting soil and sand (0-2mm diameter) in a ratio of 70:20 L. The substrate was covered with a 2 cm layer of expanded clay. The planthoppers were caged for two weeks. Insects that died during this time were removed and stored at -20°C. After two weeks, all planthoppers still alive were removed and stored at -20°C. In the second step, plants were rearranged. The four sugar beet plants were transferred to one cage while the potato plants were, due to their size, transferred to two cages. All plants were examined for the presence of eggs or nymphs. The cages were subsequently monitored for potentially emerging adults of the F1 generation three times per week for a period of six months, in order to measure the development speed of P. leporinus on the different plant species. The trial took place in a climate chamber which was programmed as in the transmission experiment for the first six weeks. After this time, the light period was set to 16/8 h light/dark mode, a temperature of 22°C and 55% relative humidity for the remaining duration of the experiment. In the period of day 50 to day 90 of the trial, the temperature and the relative humidity differed dependent on the light/dark mode (24°C / 22°C and 35% / 55% for 21 days, and 24°C / 22°C and 55% / 70% for 14 days) due to a malfunction of the operating system.

DNA isolation

DNA from plant material was extracted according to a modified Doyle protocol [

23]. For potato, about 50 mg of the navel (point of stolon attachment of the tuber), for sugar beet, 50 mg of the beet root, and for periwinkle (

Catharanthus roseus (L.) G. Don), 50 mg of mid-ribs of upper leaves were transferred into a microcentrifuge tube and homogenized with two stainless steel beads (hardened, non-rusting, 3.5 mm diameter, Kugel-Winnie, Bamberg, Germany) in a sample preparation system (Fast Prep®, MP Biomedicals, Irvine, California, USA) for 60 seconds at speed level 4.0. Then, 500 µl of Doyle-buffer was added, and DNA extraction proceeded as described [

23]. The final pellet was resuspended in 50 µl Tris-EDTA buffer (pH 8). Material from non-insect exposed potato plants (tubers or leaves) and sugar beets served as a negative control, whereas CPs-infected periwinkle served as a positive control for the Stolbur phytoplasma, and CAp-infected sugar beets as a positive control for the γ-proteobacterium.

DNA extraction from individual planthoppers was as following: each planthopper was homogenized in a microcentrifuge tube containing 500 µl Doyle buffer and 15 silica beads (SiLibeads®, type 2Y-S, 2.0 - 2.2 mm diameter, Sigmund Lindner GmbH, Germany) with the above-mentioned same sample preparation system. All subsequent steps were according to the Görg et al. protocol [

23].

The DNA yield for potato- and sugar beet extracts was determined for three samples by a NanoPhotometer®NP80 (Implen GmbH, München, Germany) and by agarose gel electrophoresis using a dilution series of lambda DNA (New England Biolabs GmbH, Germany). Prior measurement, the crude DNA extracts were treated with RNAse A (10mg/ml, Fisher Scientific GmbH, Germany) and purified by a DNA purification kit (New England Biolabs GmbH, Germany).

Real-time PCR assays and assessment of sensitivity

Duplex TaqMan assays were employed for the detection of CAp and CPs in plant material. Both assays included a plant specific primers and probe set to confirm a successful DNA extraction and absence of inhibition [

24]. Each reaction comprised 5 µl of qPCR PROBE Master Mix (primaQuant Probe Advanced, Steinbrenner Laborsysteme GmbH, Wiesenbach, Germany), 0.3 µl of each of the pathogen specific primers (10 µM) the labelled probe (6-FAM/BHQ-1, 10 µM), 0.1 µl of each of the plant primers (10 µM) and the labelled plant probe (Cy5/Tamra, 10 µM), and 2.8 µl of nuclease-free, HPLC-grade water and one µl of the DNA sample was added. Sequences of probes and primers are published [

18,

21,

24].

For the detection of the pathogens in insect material, the reaction components were the same, except that the plant primers and probe were substituted by water. PCR conditions for the detection of CAp were 95°C for 3 min, proceeded by 40 cycles of 95°C for 15 s and 60°C for 30 s. For CPs, the conditions differed slightly with 95°C for 3 min, followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 10 s and 60°C for 30 s. The threshold for positive detection was set at 35 cycles for both pathogens (cut-off value).

To determine the limit of detection for CPs in potato and sugar beet, CPs-positive potato- and sugar beet DNA extracts were serially diluted, and the decreasing DNA amount was replenished by DNA from healthy potato. A dilution series of the gBlock mixed with healthy DNA extracts was run in parallel. Real time-PCR assays were run in a Bio-Rad CFX96 Thermal Cycler (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc., Hercules, USA).

Sequencing and generation of a gBlock

A 16Sr DNA fragment of CPs from a phytoplasma-infected planthopper was amplified with primers SBRps_qRTforKL464/ SBRps_qRTrevKL465 [

21]. The amplimer was ligated in pGEM®-T (Promega Corporation, Madison, Wisconsin, USA) and transformed in

Escherichia coli strain XL1 blue. The insert was sequenced with M13 universal and M13 reverse primers (Eurofins Genomics Europe Shared Services GmbH, Germany). A 127 bp gBlock identical to the insert was synthesized by Integrated DNA Technologies (Leuven, Belgium).

3. Results

3.1. Transmission experiments

The transmission experiments revealed that adult P. leporinus were able to transmit CPs as well as CAp to potato. The results are shown in

Table 1.

3.1.1. Pathogens in planthoppers

Each of the five plants per variety had been exposed to ten, in one case to eleven, planthoppers. At the end of the transmission period, a total of 222 planthoppers could be tested for infection by CAp and CPs. All planthoppers tested were CAp-positive in real-time PCR assays. The mean quantification cycle (Cq) values differed, but 79.7% of the specimen were in the range of Cq 12 – 19 corresponding to a calculated number of 108 to 106 bacteria per insect. For CPs only 6.3% of the planthoppers tested positive, and consequently, only a fraction of the plants was actually exposed to CPs. The Cq values of eight individuals ranged between 16 to 19 corresponding to a calculated number of 5 x 106 to 4 x 105 organisms, six individuals showed a Cq in the range of 25 to 32, which corresponds to about 0.5 x 104 to 0.5 x 102 organisms of the Stolbur phytoplasma per insect detected, respectively.

3.1.2. Pathogens in plant material

Before real time-PCR assays were performed, the DNA yield for potato- and sugar beet extracts was determined. The DNA concentrations for both plants ranged between 20 to 35 ng/µl. All source material taken before trial start was tested negative for both pathogens. After the transmission trial, DNA of three tubers of each potato plant (n = 75) plus a negative control were analyzed individually. 19 tubers were tested CAp-positive (25.3%) and three tubers were tested positive for CPs (4%). Except the variety ‘Merle’, CAp was found in all varieties, whereas CPs infection was only identified in the variety ‘Merle’. However, one CPs positive tuber was identified in a cage where all seven planthoppers were tested negative for CPs, implying that at least one of the three missing insects was CPs-positive. Due to the low number of CPs infected planthoppers and their heterogeneous distribution, no statement can be made on the potential susceptibility of the other varieties.

3.2. Choice experiment

The inspection for deposited egg clutches took place two weeks after the start of the trial and revealed oviposition at the edge, bottom or top of the potted substrate. The number of eggs inside the clutches have not been counted to prevent them from damage. Seven egg clutches were found in pots with potato (1; 3; 0; 3) and nine in pots with sugar beet plants (2; 2; 3; 2). Thus, no oviposition preference for one of the host plants could be detected.

3.3. Development speed

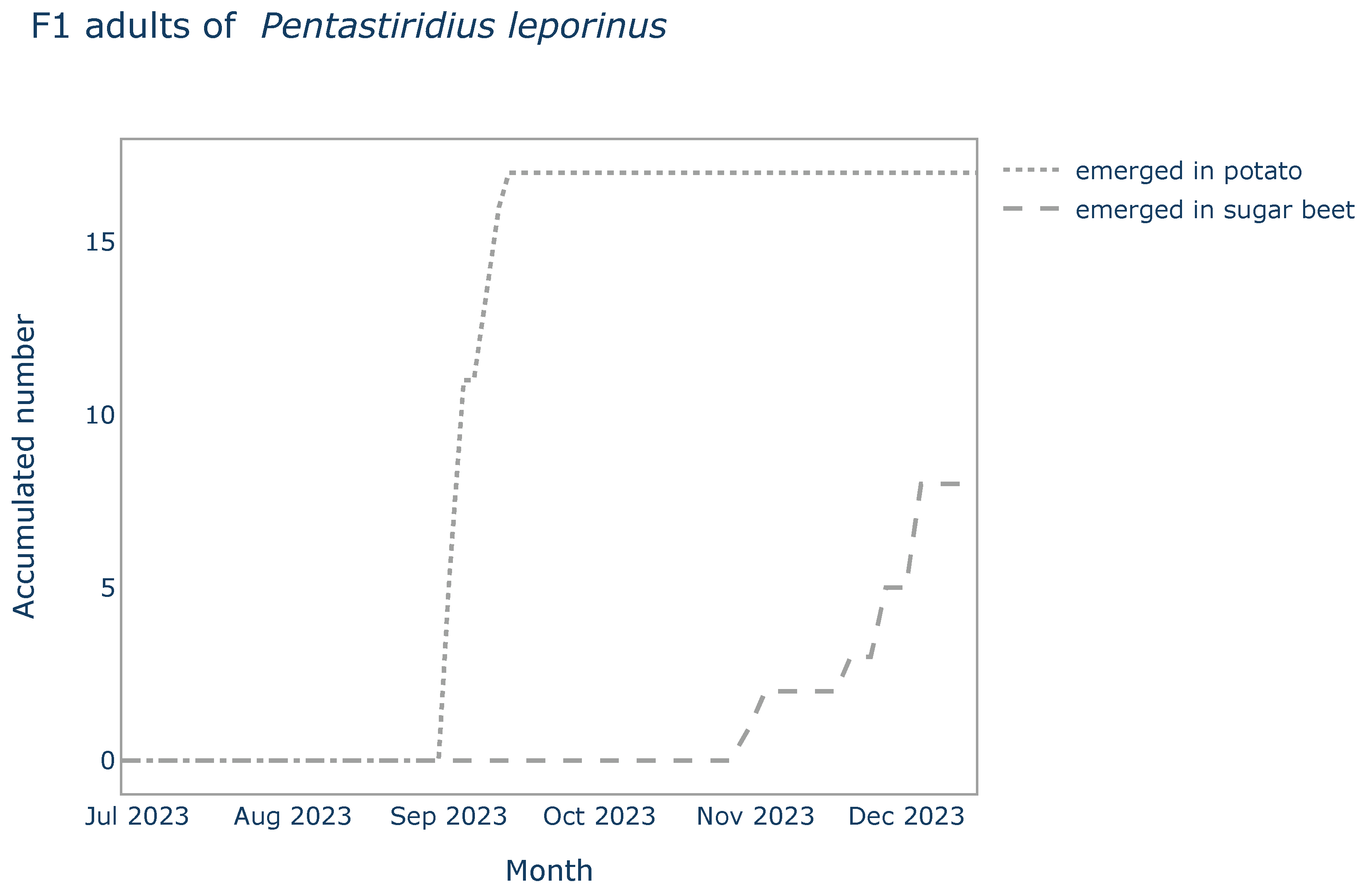

Adults of the

P. leporinus F1-generation emerged in the cages with potato earliest 65 days (T

min) and latest 77 days (T

max) after the start of the experiment. Half of the adults (n= 17) emerged after 68 days (T

median). In the cages with sugar beet plants, the first F1 adults emerged about two months later than in potato. In total, eight adults emerged over time with T

min, T

median and T

max being 125, 152 and 159 days respectively (

Figure 1).

3.4. Detection limit of CPs assay

For the quantification of CPs in plant and insect material, the sequence of the SBRps_qRTforKL464/SBRps_qRTrevKL465 amplimer was determined (

Table 2) and used to synthesize a double-stranded DNA fragment (gBlock) of 127 base pairs.

A ten-fold dilution series of the gBlock ranging from 1 x 10

8 to 1 x10

0 revealed a reliable detection of 10 copies after 35 PCR cycles with the CPs TaqMan assay (

Table 3). The C

q values between steps of 10 were 3.5 ± 0.57 apart. A copy number of one was not reliably identified with the setting used. Therefore, C

q readings after cycle 35 were considered as negative result.

The detection limit for CPs was determined for a symptomatic potato plant collected from an affected field (close to Heilbronn, Germany), and from a symptomatic sugar beet plant from rearing of

P. leporinus caught from a sugar beet field (near Heidelberg, Germany). They have been compared to the gBlock standard (

Table 4). For the potato DNA extract the C

q values (triplicates) ranged from 24.1 to 37.7, and for the sugar beet DNA extract from 22.1 to 36.8. The C

q values between the serial dilutions differed by an average of 3.4 (± 0.15) for potato, and 3.6 (± 0.37) for sugar beet. The C

q values of the serial dilutions of the gBlock mixed with potato- or sugar beet DNA differed by an average of 3.1 (± 1.6) and 3.6 (± 1.3), respectively.

4. Discussion

Recently, potato growers in southwest Germany reported losses in yield and tuber quality of plants showing Stolbur-like symptoms [

14,

15]. This and the incidence of

P. leporinus in potato fields in Germany in 2022 [

17], prompted us to study the development of

P. leporinus and its vectoring capacities for CPs and CAp in potato in more detail. Choice and transmission experiments were performed to elucidate its lifecycle on potato and to confirm its role as a potent vector.

Our study confirmed that potato plants represent a suitable host for

P. leporinus on which the insect can complete its entire lifecycle. We observed that the timespan from oviposition to the appearance of the first adults differed by almost two months between the development on potato or sugar beet. However, the numbers of egg clutches and emerging adults were low, and thus, the results should be considered as preliminary with regard to differences in host plant dependent development speed of the vector. The observation that the speed of the lifecycle depends on the host plant has been already observed for another cixiid planthopper,

H. obsoletus. Here, a difference of the start of the flight activity was reported from populations developed on bindweed (

Convolvulus arvensis), which approximately started three to four weeks prior to those that developed on nettle (

Urtica dioica) [

25]. However, the underlying factors such as the composition of the phloem sap have not been elucidated, yet. Further research should be conducted to elucidate the phloem metabolites, which may be responsible for the differences in development speed [

26]. In perspective of insect rearing, our results may be interesting as they show that lifecycle experiments could be conducted in shorter time. Pfitzer et al. reported a timespan from first instar to adult of 193.6 ±35.8 days for males and 193.5 ±59.2 days for females on sugar beet, whereas Behrmann et al. reported a timespan of 170 days after hatching, also on sugar beet [

21,

22]. The implications of our finding for the expectable epidemiology of the transmitted diseases due to possible increasing numbers of annual generations of the planthopper should be also studied in future.

In this study we could further demonstrate that adults of

P. leporinus are capable to transmit CPs and CAp to potato. That other cixiid species are able to vector CPs has been demonstrated before. In Southeastern Europe,

Reptalus quinquecostatus transmits CPs to sugar beet [

13] and

Reptalus panzeri and

H. obsoletus have been confirmed to transmit CPs to grapevine [

27,

28,

29].

H. obsoletus was further reported as a vector for the Stolbur disease in lavender [

30], but also in vegetables like tomato, eggplant, tobacco [

31] and annual crops like maize [

32], sugar beet [

33] and potato [

34,

35,

36,

37,

38,

39], where it can cause serious effects in yield and tuber quality [

40]. Whereas nymphs of

P. leporinus have been reported to transmit CAp to potato [

17], this is to our knowledge the first report that adults of this species transmit CPs as well as CAp to potato. Besides

P. leporinus, no other planthopper species is known to vector CAp to plants, including sugar beet and potato.

It may not be appropriate to directly transfer the transmission results from lab experiments to field conditions as effects of landscape, tillage, insecticide use, or crop rotation may play a role for transmission of these pathogens to specific crops. But given the evidence that

P. leporinus is well established in sugar beet cultivation, and its major role in the epidemiology of SBR of sugar beet in Germany [

2,

3], data of this study indicates a high vectoring potential of

P. leporinus for CPs and CAp to potato. This may apply in particular to regions where this vector is already highly abundant and where both crops form part of the regional crop rotation, and thus are simultaneously available as host plants.

The transmission experiments showed another remarkable finding: none of the examined tubers of the variety ‘Merle’ tested positive for CAp, although all 42 insects were CAp positive showing high bacteria titers. Conversely, only three CPs infected leafhoppers in three independent cages resulted in a successful transmission. Interestingly, variety ‘Gala’ was not infected by CPs, but by CAp - although insects were partly double-infected with comparable pathogen titers. These findings might indicate a differential susceptibility of potato varieties to CPs and CAp.

So far, a correlation between the pathogen titer in potato or sugar beet and the symptom severity is still missing. Therefore, a more comprehensive study should be conducted including an evaluation of infection on yield, quality and on the susceptibility of varieties. These investigations have to be accompanied by real-time PCR monitoring, but caution is required on the pooling of sample material, since information is lacking on the spatial distribution of the two pathogens inside the tubers, stem or other plant tissue.

With regards to real-time PCR diagnostics, different primers for CAp and CPs have been developed [

18,

41]. Behrmann et al. used real-time PCR assays for CAp and CPs based on 16S rDNA sequences with cloned quantification standard [

21]. Since the production of a recombinant plasmid requires S1 security standards, we synthesized a gBlock derived from a 16S rDNA sequence for quantification, which can be used by plant protection services and other authorities working under lower security standards. With our settings we were able to detect 10 copies of the DNA fragment, regardless of the gBlock being used as a template by itself or mixed with potato or sugar beet DNA. Lower copy numbers were not reliably identified. Both assays were suited to detect the pathogen with high sensitivity in picogram amounts of DNA. This quantification method, together with existing ones, may also facilitate further research on the response of potato but also other plants to both pathogens.

5. Conclusions

Our data present for the first time evidence that adults of P. leporinus transmit both CAp and CPs to potato. We further show that P. leporinus can complete its whole lifecycle on this crop under controlled conditions. Our study also provides a new standard for real-time PCR which allows for quantification of the Stolbur pathogen in the tested plant or insect material.

Further research is required on the varietal response of potatoes such as tolerance, resistance, tuber quality and yield to pathogen titres and/or vector infestation. Also, effective and sustainable management options for this new vector-pathogen-plant complex must be investigated, as the affected potato-growing area in Germany and neighboring countries is likely to increase in future, as we have already observed in sugar beet.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization and design of the experiments, E.T., J.G.; investigation, E.T.; validation, E.T., B.S.; formal analysis, E.T., B.S., K.Z; data curation, E.T., B.S..; writing—original draft preparation, E.T.; writing—review and editing, E.T., B.S., M.M., K.Z., J.G.; visualization, E.T.; funding acquisition, J.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors are grateful to the Union der Deutschen Kartoffelwirtschaft e. V. (UNIKA) and Germany's development agency for agribusiness and rural areas (Rentenbank) for funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank C. Gerbert, N. Giesen, K. Zegers, F. Hergenhahn, S. Kugler and P. Berberich for their kind support in sweeping planthoppers, and their excellent assistance in the laboratory and greenhouse. Further, we gratefully acknowledge M. Bücher, M. and B. Dreßler for kindly providing seed tubers, as well as D. Löffler and D. Kreimer for their assistance getting the tubers on short-term notice. We also thank P. Risser and S. Haas for allowing us the sweeping of planthoppers on their fields.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be constructed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Pfitzer, R.; Schrameyer, K.; Voegele, R. T.; Maier, J.; Lang, C.; Varrelmann, M. Causes and effects of the occurrence of “Syndrome des basses richesses” in German sugar beet growing areas. Sugar Ind. 2020, 145, 234–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behrmann, S.; Schwind, M.; Schieler, M.; Vilcinskas, A.; Martinez, O.; Lee, K.-Z.; Lang, C. Spread of Bacterial and Virus Yellowing Diseases of Sugar Beet in South and Central Germany from 2017–2020. Sugar Ind. 2021, 476–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bressan, A.; Moral García, F. J.; Boudon-Padieu, E. The Prevalence of ‘Candidatus Arsenophonus Phytopathogenicus’ Infecting the Planthopper Pentastiridius Leporinus (Hemiptera: Cixiidae) Increase Nonlinearly With the Population Abundance in Sugar Beet Fields. Environ. Entomol. 2011, 40, 1345–1352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahillon, M.; Groux, R.; Bussereau, F.; Brodard, J.; Debonneville, C.; Demal, S.; Kellenberger, I.; Peter, M.; Steinger, T.; Schumpp, O. Virus Yellows and Syndrome “Basses Richesses” in Western Switzerland: A Dramatic 2020 Season Calls for Urgent Control Measures. Pathogens 2022, 11, 885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sémétey, O.; Bressan, A.; Richard-Molard, M.; Boudon-Padieu, E. Monitoring of Proteobacteria and Phytoplasma in Sugar Beets Naturally or Experimentally Affected by the Disease Syndrome ‘Basses Richesses’. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 2007, 117, 187–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quaglino, F.; Zhao, Y.; Casati, P.; Bulgari, D.; Bianco, P. A.; Wei, W.; Davis, R. E. ‘Candidatus Phytoplasma Solani’, a Novel Taxon Associated with Stolbur- and Bois Noir-Related Diseases of Plants. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2013, 63, 2879–2894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bressan, A.; Terlizzi, F.; Credi, R. Independent Origins of Vectored Plant Pathogenic Bacteria from Arthropod-Associated Arsenophonus Endosymbionts. Microb. Ecol. 2012, 63, 628–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonella, E.; Tedeschi, R.; Crotti, E.; Alma, A. Multiple Guests in a Single Host: Interactions across Symbiotic and Phytopathogenic Bacteria in Phloem-Feeding Vectors – a Review. Entomol. Exp. Appl. 2019, 167, 171–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schröder, M.; Rissler, D.; Schrameyer, K. “Syndrome Des Basses Richesses” (SBR) - Erstmaliges Auftreten an Zuckerrübe in Deutschland. J. für Kult. 2012, 64, 396. [Google Scholar]

- Gummirüben: Diese neue Krankheit befällt gerade ganze Rübenfelder. Available online: https://www.agrarheute.com/pflanze/zuckerrueben/gummirueben-diese-neue-krankheit-befaellt-gerade-ganze-ruebenfelder-611667 (accessed on 13 February 2024).

- Gummirübe: Zuckerrüben bayerischer Bauern immer öfter betroffen. Available online: https://www.wochenblatt-dlv.de/feld-stall/pflanzenbau/gummiruebe-zuckerrueben-bayerischer-bauern-immer-oefter-betroffen-575715 (accessed on 19 February 2024).

- Hausmann, J. (Federal Research Centre for Cultivated Plants, Institute for Plant Protection in Field Crops and Grassland, Braunschweig, Germany). Personal Communication, 2024.

- Kosovac, A.; Ćurčić, Ž.; Stepanović, J.; Rekanović, E.; Duduk, B. Epidemiological Role of Novel and Already Known ‘Ca. P. Solani’ Cixiid Vectors in Rubbery Taproot Disease of Sugar Beet in Serbia | Scientific Reports. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 1433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Achtung Zikaden: Darum schädigen sie außer Rüben auch Kartoffeln. Available online: https://www.agrarheute.com/pflanze/kartoffeln/achtung-zikaden-schaedigen-ausser-rueben-kartoffeln-603858 (accessed on 22 January 2024).

- Schilf-Glasflügelzikade schädigt auch Kartoffeln. Available online: https://www.topagrar.com/acker/news/schilf-glasfluegelzikade-schaedigt-auch-kartoffeln-13287306.html (accessed on 22 January 2024).

- Çağlar, B. K.; Şimşek, E. Detection and Multigene Typing of ‘Candidatus Phytoplasma Solani’-Related Strains Infecting Tomato and Potato Plants in Different Regions of Turkey. Pathogens 2022, 11, 1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behrmann, S. C.; Rinklef, A.; Lang, C.; Vilcinskas, A.; Lee, K.-Z. Potato (Solanum Tuberosum) as a New Host for Pentastiridius Leporinus (Hemiptera: Cixiidae) and Candidatus Arsenophonus Phytopathogenicus. Insects 2023, 14, 281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zübert, C.; Kube, M. Application of TaqMan Real-Time PCR for Detecting ‘Candidatus Arsenophonus Phytopathogenicus’ Infection in Sugar Beet. Pathogens 2021, 10, 1466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biedermann, R.t; Niedringhaus, R. The Plant- and Leafhoppers of Germany - Identification Key to All Species; Scheeßel: WABV, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Jarausch, B.; Markheiser, A.; Jarausch, W.; Biancu, S.; Kugler, S.; Runne, M.; Maixner, M. Risk Assessment for the Spread of Flavescence Dorée-Related Phytoplasmas from Alder to Grapevine by Alternative Insect Vectors in Germany. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 2766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behrmann, S. C.; Witczak, N.; Lang, C.; Schieler, M.; Dettweiler, A.; Kleinhenz, B.; Schwind, M.; Vilcinskas, A.; Lee, K.-Z. Biology and Rearing of an Emerging Sugar Beet Pest: The Planthopper Pentastiridius Leporinus. Insects 2022, 13, 656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pfitzer, R.; Varrelmann, M.; Schrameyer, K.; Rostás, M. Life History Traits and a Method for Continuous Mass Rearing of the Planthopper Pentastiridius Leporinus, a Vector of the Causal Agent of Syndrome ‘Basses Richesses’ in Sugar Beet. Pest Manag. Sci. 2022, 78, 4700–4708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Görg, L. M.; Gallinger, J.; Gross, J. The Phytopathogen ‘Candidatus Phytoplasma Mali’ Alters Apple Tree Phloem Composition and Affects Oviposition Behavior of Its Vector Cacopsylla Picta. Chemoecology 2021, 31, 31–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, N. M.; Nicolaisen, M.; Hansen, M.; Schulz, A. Distribution of Phytoplasmas in Infected Plants as Revealed by Real-Time PCR and Bioimaging. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interactions® 2004, 17, 1175–1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maixner, M. Biology of Hyalesthes Obsoletus and Approaches to Control This Soilborne Vector of Bois Noir Disease. Integr. Control Soil Insect Pests 2007, IOBC/wprs Bulletin Vol. 30, 3–9. 30.

- Gross, J.; Gallinger, J.; Görg, L. Interactions between Phloem-Restricted Bacterial Plant Pathogens, Their Vector Insects, Host Plants, and Natural Enemies, Mediated by Primary and Secondary Plant Metabolites. Entomol. Gen. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quaglino, F.; Sanna, F.; Moussa, A.; Faccincani, M.; Passera, A.; Casati, P.; Bianco, P. A.; Mori, N. Identification and Ecology of Alternative Insect Vectors of ‘Candidatus Phytoplasma Solani’ to Grapevine. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 19522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maixner, M. Transmission of German Grapevine Yellows (Vergilbungskrankheit) by the Planthopper Hyalesthes Obsoletus (Auchenorrhyncha: Cixiidae). VITIS - J. Grapevine Res. 1994, 33, 103–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sforza, R.; Clair, D.; Daire, X.; Larrue, J.; Boudon-Padieu, E. The Role of Hyalesthes Obsoletus (Hemiptera: Cixiidae) in the Occurrence of Bois Noir of Grapevines in France. J. Phytopathol. 1998, 146, 549–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Séméty, O.; Gaudin, J.; Danet, J.-L.; Salar, P.; Theil, S.; Fontaine, M.; Krausz, M.; Chaisse, E.; Eveillard, S.; Verdin, E.; Foissac, X. Lavender Decline in France Is Associated with Chronic Infection by Lavender-Specific Strains of “Candidatus Phytoplasma Solani”. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2018, 84, e01507-18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fos, A.; Danet, J. L.; Zreik, L.; Garnier, M.; Bové, J. M. Use of a Monoclonal Antibody to Detect the Stolbur Mycoplasmalike Organism in Plants and Insects and to Identify a Vector in France. Plant Dis. 1992, 76, 1092–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jović, J.; Cvrković, T.; Mitrović, M.; Krnjajić, S.; Petrović, A.; Redinbaugh, M. G.; Pratt, R. C.; Hogenhout, S. A.; Toševski, I. Stolbur Phytoplasma Transmission to Maize by Reptalus Panzeri and the Disease Cycle of Maize Redness in Serbia. Phytopathology® 2009, 99, 1053–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ćurčić, Ž.; Kosovac, A.; Stepanović, J.; Rekanović, E.; Kube, M.; Duduk, B. Multilocus Genotyping of ‘Candidatus Phytoplasma Solani’ Associated with Rubbery Taproot Disease of Sugar Beet in the Pannonian Plain. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 1950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fialová, R.; Válová, P.; Balakishiyeva, G.; Danet, J.-L.; Šafárová, D.; Foissac, X.; Navrátil, M. Genetic Variability of Stolbur Phytoplasma in Annual Crop and Wild Plant Species in South Moravia. J. Plant Pathol. 2009, 91, 411–416. [Google Scholar]

- Ulrich, R.; Preiss, U.; Fabich, S. Potato Stolbur phytoplasma in Hesse and Rhineland-Palatinate. Julius-Kühn-Arch. 2010, No. No.428.

- Preiss, U.; Fabich, S.; Mather-Kaub, H.; Albert, G.; Keuck, A. Potato Stolbur of potatoes. Julius-Kühn-Arch. 2010, No. No.428.

- Holeva, M. C.; Glynos, P. E.; Karafla, C. D.; Koutsioumari, E. M.; Simoglou, K. B.; Eleftheriadis, E. First Report of Candidatus Phytoplasma Solani Associated with Potato Plants in Greece. Plant Dis. 2014, 98, 1739–1739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zimmerman-Gries, S. ‘Stolbur’ — A New Potato Disease in Israel. Potato Res. 1970, 13, 146–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitrovic, M.; Trivellone, V.; Jovic, J.; Cvrkovic, T.; Jakovljevic, M.; Kosovac, A.; Krstic, O.; Toševski, I. Potential Hemipteran Vectors of “Stolbur” Phytoplasma in Potato Fields in Serbia. Phytopathogenic Mollicutes 2015, 5, S49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindner, K.; Haase, N. U.; Roman, M.; Seemüller, E. Impact of Stolbur Phytoplasmas on Potato Tuber Texture and Sugar Content of Selected Potato Cultivars. Potato Res. 2011, 54, 267–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jovic, J.; Marinković, S.; Jakovljevic, M.; Krstić, O.; Cvrković, T.; Mitrović, M.; Toševski, I. Symptomatology, (Co)Occurrence and Differential Diagnostic PCR Identification of ‘Ca. Phytoplasma Solani’ and ‘Ca. Phytoplasma Convolvuli’ in Field Bindweed. Pathogens 2021, 10, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).