Submitted:

08 February 2024

Posted:

12 February 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

Site and soil characterization

Microbial inoculants

Dryland field experiment

Plant nutrient uptake, yield, and microbial dependency

Microbial community analysis

3. Results

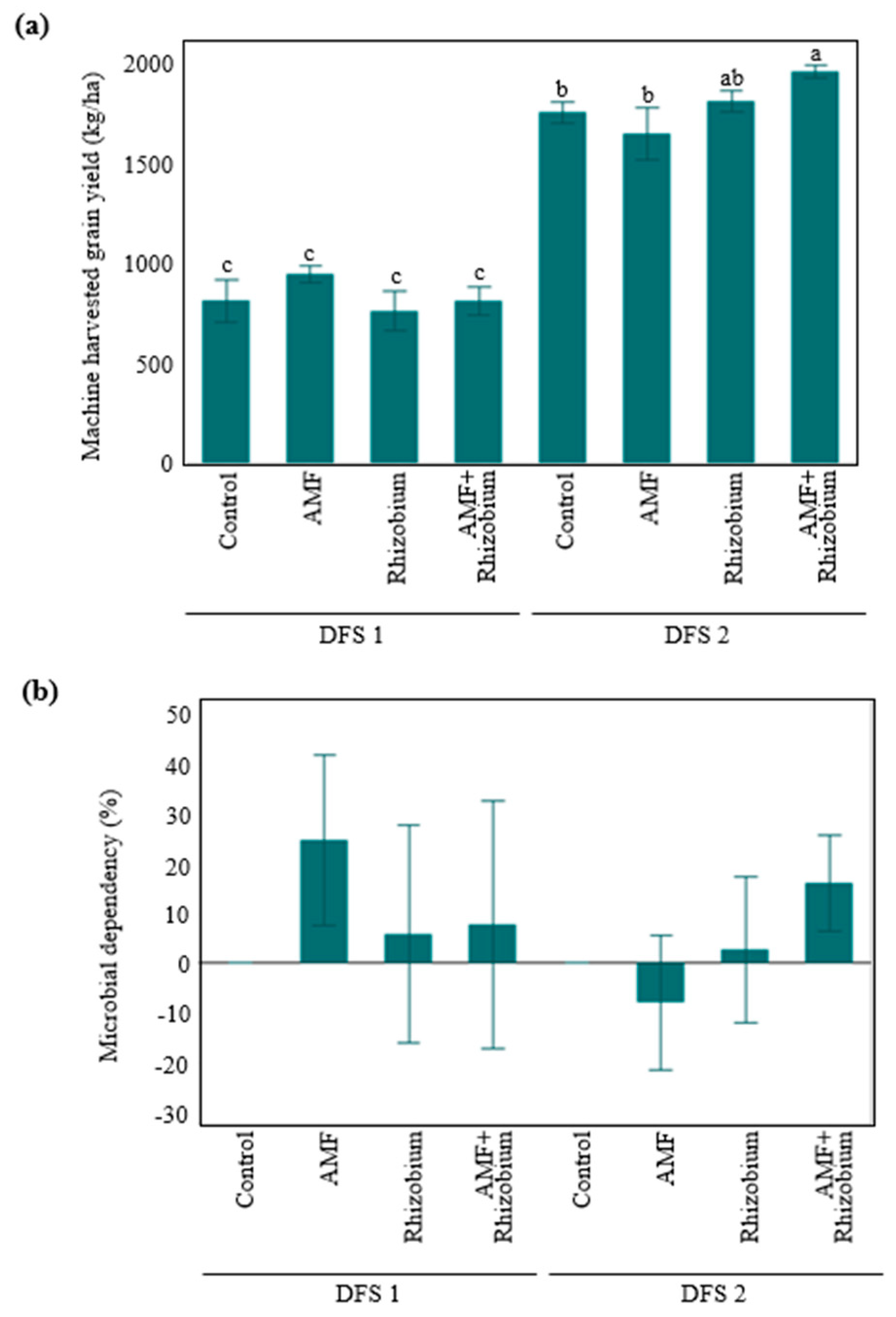

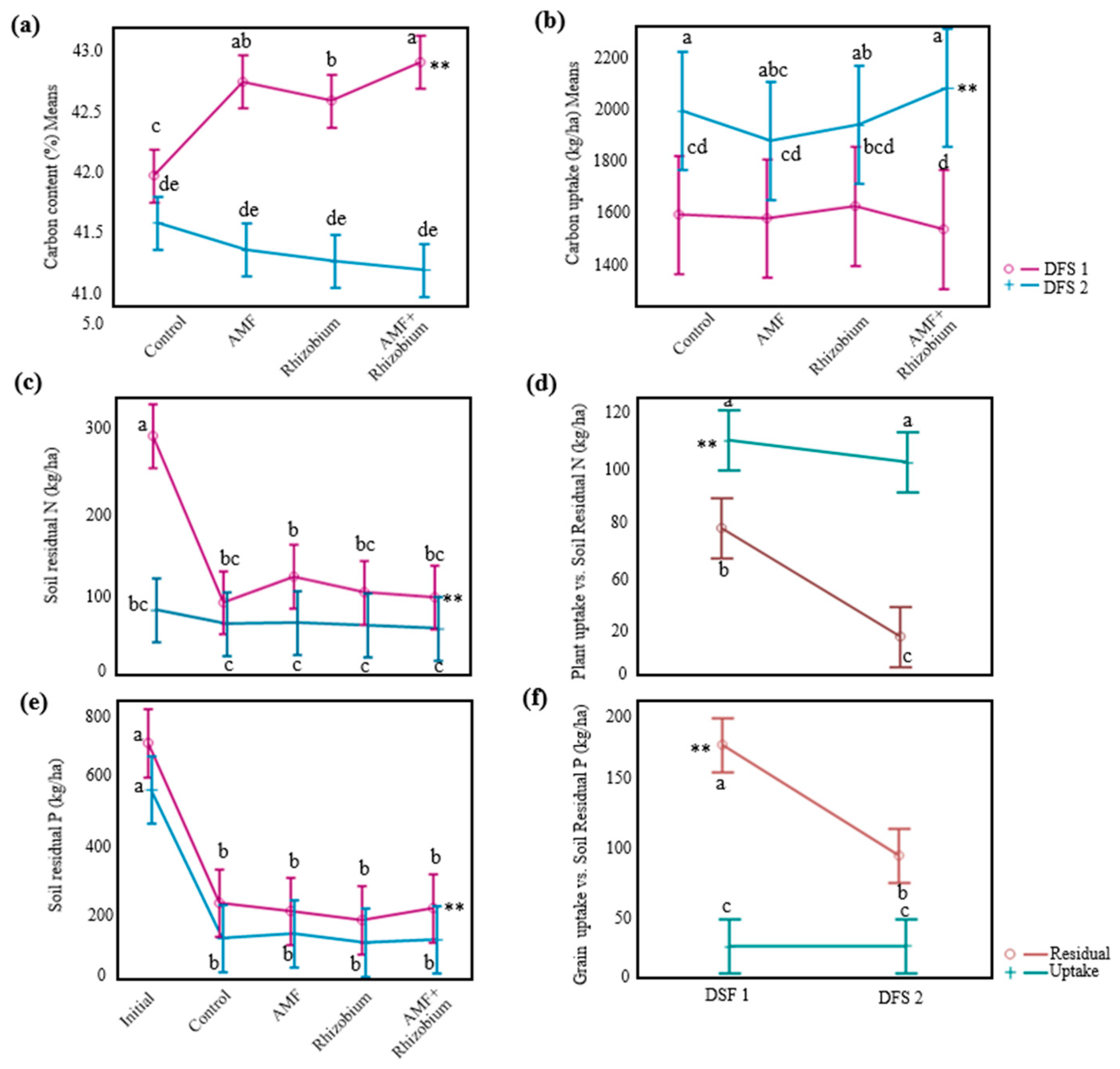

Influence of microbial inoculants on plant agronomic performance and nutrient dynamics

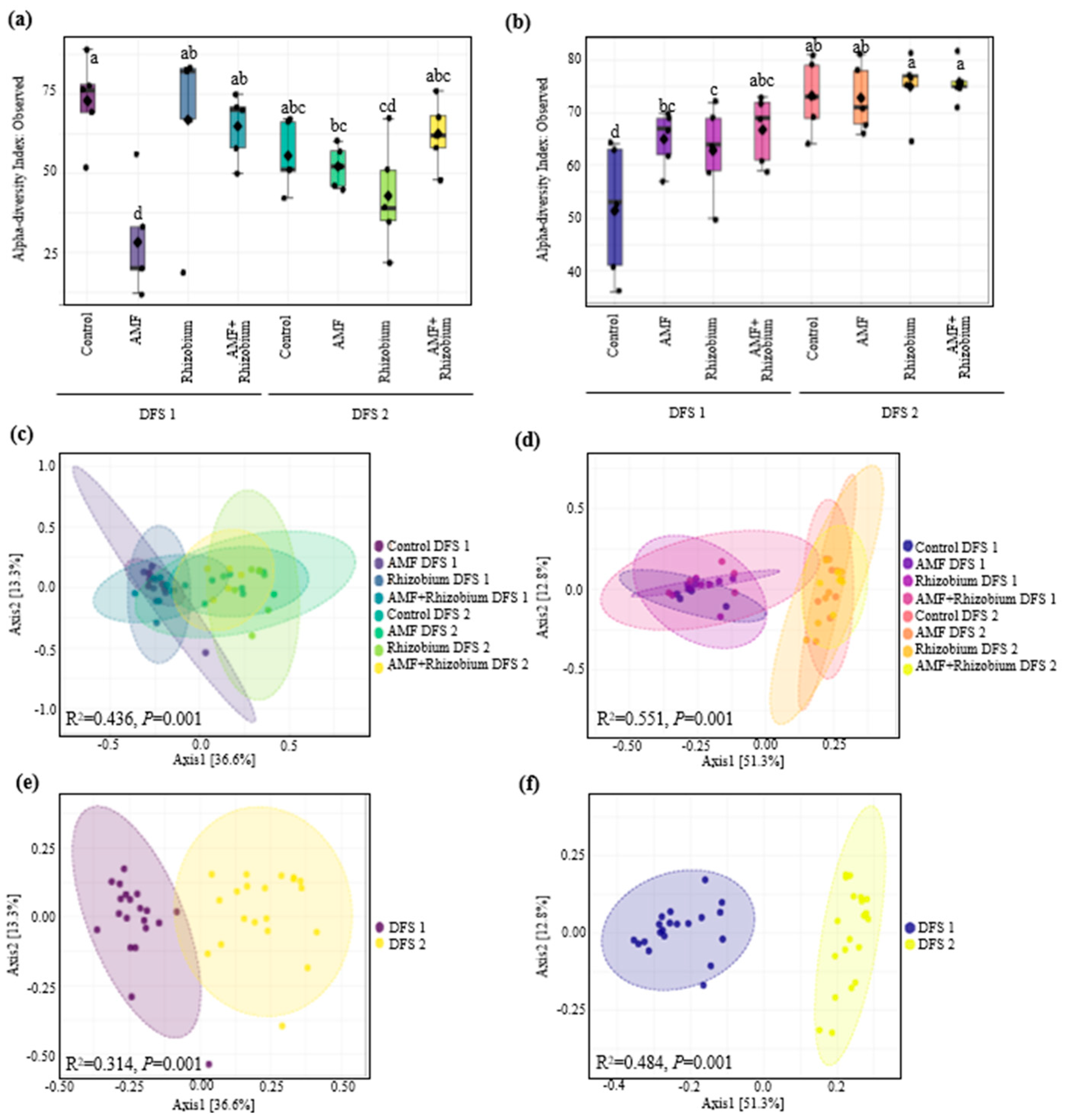

Variation in the soil microbial communities associated with increase plant yield in two contrasting dryland sites

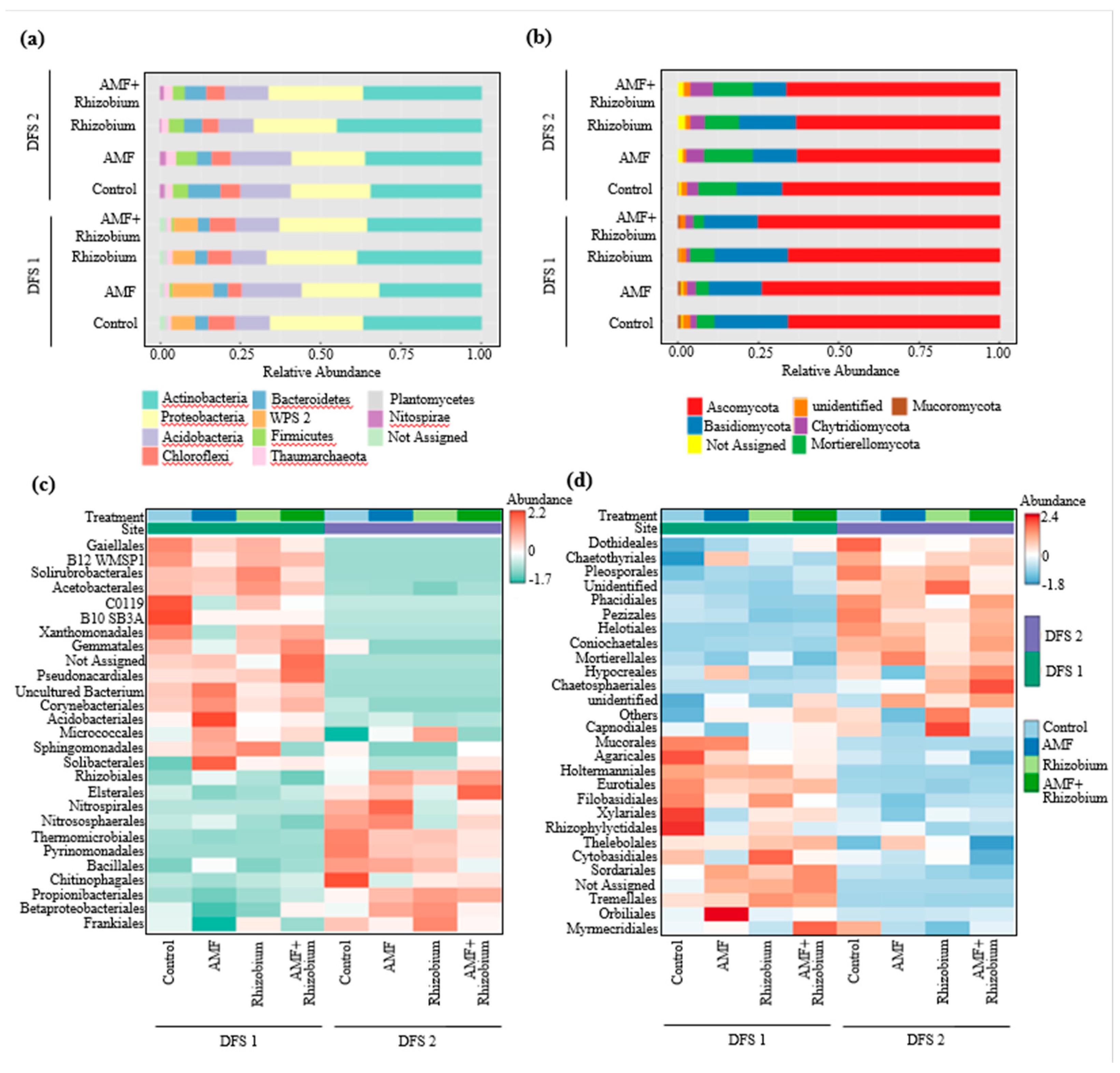

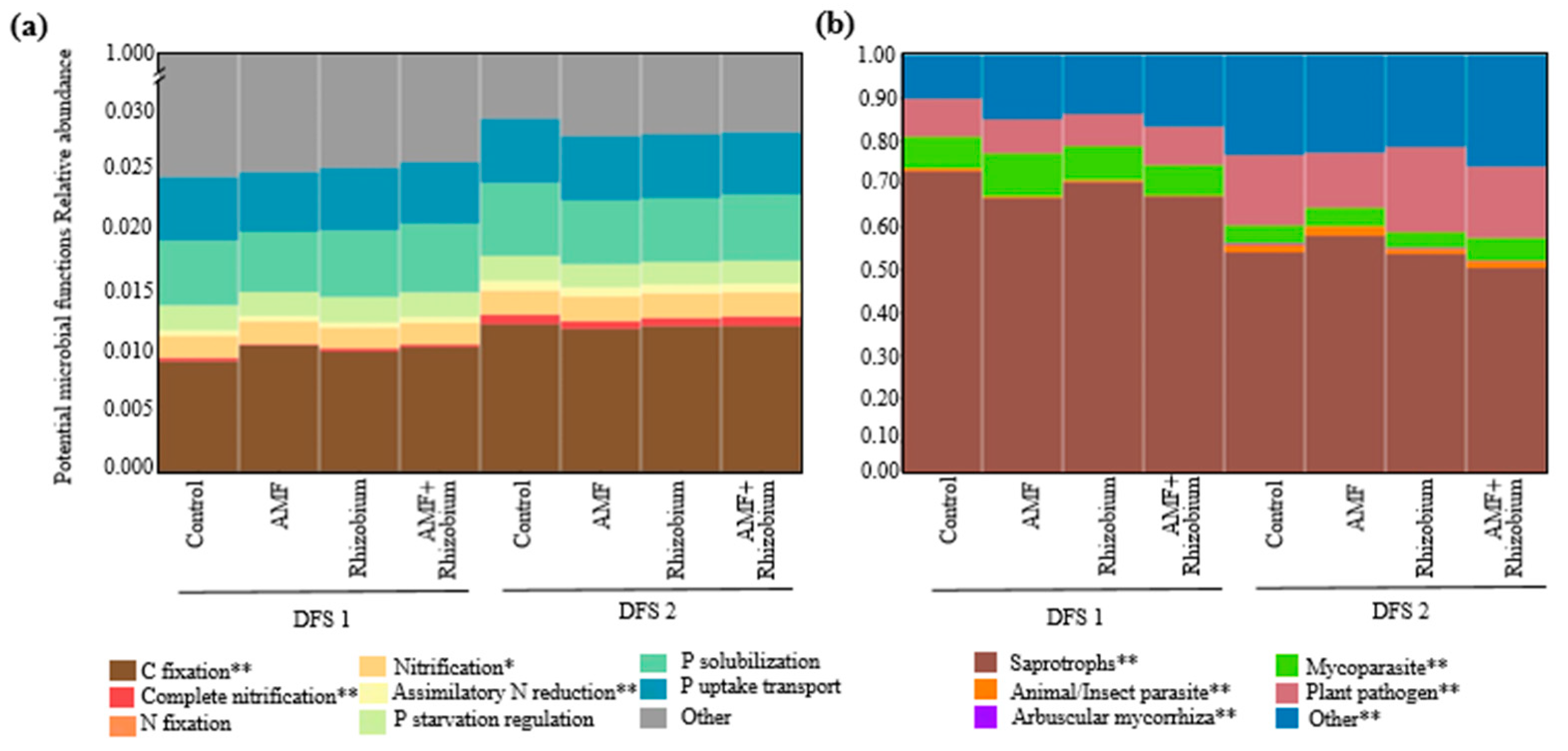

Effect of microbial inoculants on the potential functions of the microbial community relative to nutrient cycling and soil health

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- FAO of the, UN. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nation. 2018 [cited 2019 Jan 5]. CropWat | Land & Water | Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Available from: http://www.fao.org/land-water/databases-and-software/crop-information/soybean/en/.

- Liebig, M.A.; Acosta-Martinez, V.; Archer, D.W.; Halvorson, J.J.; Hendrickson, J.R.; Kronberg, S.L.; Samson-Liebig, S.E.; Vetter, J.M. Conservation practices induce tradeoffs in soil function: Observations from the northern Great Plains. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 2022, 86, 1413–1430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, GA. Dryland Farming. In: Reference Module in Earth Systems and Environmental Sciences. Elsevier; 2018.

- Püschel, D.; Janoušková, M.; Voříšková, A.; Gryndlerová, H.; Vosátka, M.; Jansa, J. Arbuscular Mycorrhiza Stimulates Biological Nitrogen Fixation in Two Medicago spp. through Improved Phosphorus Acquisition. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruisi, P.; Giambalvo, D.; Di Miceli, G.; Frenda, A.S.; Saia, S.; Amato, G. Tillage Effects on Yield and Nitrogen Fixation of Legumes in Mediterranean Conditions. Agron. J. 2012, 104, 1459–1466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones MD, Durall DM, Tinker PB. A comparison of arbuscular and ectomycorrhizal Eucalyptus coccifera : Growth response, phosphorus uptake efficiency and external hyphal production. New Phytol. 1998, 140, 125–134.

- Goltapeh EM, Danesh YR, Prasad R, Varma A. Mycorrhizal fungi: what we know and what should we know? In: Mycorrhiza. Springer; 2008. p. 3–27.

- ezáčová V, Konvalinková T, Jansa J. Carbon fluxes in mycorrhizal plants. Mycorrhiza-eco-physiology, Second Metab Nanomater. 2017, 1–21.

- Yang, L.; Luo, Y.; Lu, B.; Zhou, G.; Chang, D.; Gao, S.; Zhang, J.; Che, Z.; Cao, W. Long-term maize and pea intercropping improved subsoil carbon storage while reduced greenhouse gas emissions. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2023, 349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khangura, R.; Ferris, D.; Wagg, C.; Bowyer, J. Regenerative Agriculture—A Literature Review on the Practices and Mechanisms Used to Improve Soil Health. Sustainability 2023, 15, 2338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xavier, G.R.; Jesus, E.d.C.; Dias, A.; Coelho, M.R.R.; Molina, Y.C.; Rumjanek, N.G. Contribution of Biofertilizers to Pulse Crops: From Single-Strain Inoculants to New Technologies Based on Microbiomes Strategies. Plants 2023, 12, 954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chouhan, G.K.; Verma, J.P.; Jaiswal, D.K.; Mukherjee, A.; Singh, S.; Pereira, A.P.d.A.; Liu, H.; Abd_Allah, E.F.; Singh, B.K. Phytomicrobiome for promoting sustainable agriculture and food security: Opportunities, challenges, and solutions. Microbiol. Res. 2021, 248, 126763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trivedi, P.; Leach, J.E.; Tringe, S.G.; Sa, T.; Singh, B.K. Plant–microbiome interactions: From community assembly to plant health. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2020, 18, 607–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Laterrière, M.; Lay, C.-Y.; Klabi, R.; Masse, J.; St-Arnaud, M.; Yergeau, É.; Lupwayi, N.Z.; Gan, Y.; Hamel, C. Effects of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi inoculation and crop sequence on root-associated microbiome, crop productivity and nutrient uptake in wheat-based and flax-based cropping systems. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2021, 168, 104136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, M.H.; Graham, J.H. Little evidence that farmers should consider abundance or diversity of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi when managing crops. New Phytol. 2018, 220, 1092–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, Z.; Egidi, E.; Liu, H.; Kaur, S.; Singh, B.K. New frontiers in agriculture productivity: Optimised microbial inoculants and in situ microbiome engineering. Biotechnol. Adv. 2019, 37, 107371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pieterse, C.M.J.; Zamioudis, C.; Berendsen, R.L.; Weller, D.M.; Van Wees, S.C.M.; Bakker, P.A.H.M. Induced Systemic Resistance by Beneficial Microbes. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 2014, 52, 347–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lugtenberg B, Kamilova F. Plant-Growth-Promoting Rhizobacteria. 2009; Annual Reviews Microbiol. 2009:63:541.

- Masrahi, A.S.; Alasmari, A.; Shahin, M.G.; Qumsani, A.T.; Oraby, H.F.; Awad-Allah, M.M.A. Role of Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi and Phosphate Solubilizing Bacteria in Improving Yield, Yield Components, and Nutrients Uptake of Barley under Salinity Soil. Agriculture 2023, 13, 537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cozzolino V, Monda H, Savy D, Di Meo V, Vinci G, Smalla K. Cooperation among phosphate-solubilizing bacteria, humic acids and arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi induces soil microbiome shifts and enhances plant nutrient uptake. Chem Biol Technol Agric. 2021, 8, 1–18.

- Chaparro, J.M.; Badri, D.V.; Vivanco, J.M. Rhizosphere microbiome assemblage is affected by plant development. ISME J. 2013, 8, 790–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calderon, R.B.; Jeong, C.; Ku, H.-H.; Coghill, L.M.; Ju, Y.J.; Kim, N.; Ham, J.H. Changes in the Microbial Community in Soybean Plots Treated with Biochar and Poultry Litter. Agronomy 2021, 11, 1428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dastogeer, K.M.; Tumpa, F.H.; Sultana, A.; Akter, M.A.; Chakraborty, A. Plant microbiome–an account of the factors that shape community composition and diversity. Curr. Plant Biol. 2020, 23, 100161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzpatrick, C.R.; Schneider, A.C. Unique bacterial assembly, composition, and interactions in a parasitic plant and its host. J. Exp. Bot. 2020, 71, 2198–2209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Z.; Gu, Y.; Friman, V.-P.; Kowalchuk, G.A.; Xu, Y.; Shen, Q.; Jousset, A. Initial soil microbiome composition and functioning predetermine future plant health. Sci. Adv. 2019, 5, eaaw0759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sainju UM, Liptzin D, Stevens WB. How soil carbon fractions relate to soil properties and crop yields in dryland cropping systems? Soil Sci Soc Am J. 2022, 86, 795–809.

- Gelderman RH, Beegle D. Nitrate-nitrogen. Recomm Chem soil test Proced North Cent Reg North Cent Reg Res Publ. 1998, 221:17–20.

- Warncke D, Brown JR. Potassium and other basic cations. Recomm Chem soil test Proced North Cent Reg. 1998, 1001:31.

- Combs SM, Nathan M V. Soil organic matter. Recomm Chem soil test Proced North Cent Reg. 1998, 221:53–8.

- AGTIV. Active ingredients [Internet]. 2023 [cited 2023 Nov 8]. Available from: https://www.ptagtiv.com/en/active-ingredients/#mycorrhizae.

- Campbell CR and PCO. Reference plant analysis procedures for the southern region of the United States. South Co-op Ser Bull. 1992, 368:71–3.

- Paye WS, Szogi AA, Shumaker PD, Billman ED. Annual Ryegrass (Lolium multiflorum Lam.) Growth Response to Nitrogen in a Sandy Soil Amended with Acidified Manure and Municipal Sludge after “Quick Wash” Treatment. Agronomy. 2023, 13.

- Van Der Heijden MGA. Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi as a determinant of plant diversity: in search of underlying mechanisms and general principles. In: Mycorrhizal ecology. Springer; 2002. p. 243–65.

- Parada, A.E.; Needham, D.M.; Fuhrman, J.A. Every base matters: assessing small subunit rRNA primers for marine microbiomes with mock communities, time series and global field samples. Environ. Microbiol. 2016, 18, 1403–1414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quince, C.; Lanzen, A.; Davenport, R.J.; Turnbaugh, P.J. Removing Noise From Pyrosequenced Amplicons. BMC Bioinform. 2011, 12, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, T.J.; Bruns, T.; Lee, S.; Taylor, J. Amplification and direct sequencing of fungal ribosomal RNA genes for phylogenetics. PCR Protoc a Guid to methods Appl 1990, 18, 315–322. [Google Scholar]

- Gohl, D.M.; Vangay, P.; Garbe, J.; MacLean, A.; Hauge, A.; Becker, A.; Gould, T.J.; Clayton, J.B.; Johnson, T.J.; Hunter, R.; et al. Systematic improvement of amplicon marker gene methods for increased accuracy in microbiome studies. Nat. Biotechnol. 2016, 34, 942–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estaki, M.; Jiang, L.; Bokulich, N.A.; McDonald, D.; González, A.; Kosciolek, T.; Martino, C.; Zhu, Q.; Birmingham, A.; Vázquez-Baeza, Y.; et al. QIIME 2 Enables Comprehensive End-to-End Analysis of Diverse Microbiome Data and Comparative Studies with Publicly Available Data. Curr. Protoc. Bioinform. 2020, 70, e100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, M. Cutadapt removes adapter sequences from high-throughput sequencing reads. EMBnet. J. 2011, 17, 10–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callahan, B.J.; Mcmurdie, P.J.; Rosen, M.J.; Han, A.W.; Johnson, A.J.A.; Holmes, S.P. DADA2: High-resolution sample inference from Illumina amplicon data. Nat. Methods 2016, 13, 581–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katoh K, Misawa K, Kuma KI, Miyata T. MAFFT: A novel method for rapid multiple sequence alignment based on fast Fourier transform. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002, 30, 3059–3066.

- Price, M.N.; Dehal, P.S.; Arkin, A.P. FastTree 2—Approximately Maximum-Likelihood Trees for Large Alignments. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e9490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bokulich NA, Kaehler BD, Rideout JR, Dillon M, Bolyen E, Knight R, et al. Optimizing taxonomic classification of marker-gene amplicon sequences with QIIME 2’s q2-feature-classifier plugin. Microbiome. 2018, In Press.

- Quast C, Pruesse E, Yilmaz P, Gerken J, Schweer T, Yarza P, et al. The SILVA ribosomal RNA gene database project: improved data processing and web-based tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012, 41, D590–6.

- Camacho, C.; Coulouris, G.; Avagyan, V.; Ma, N.; Papadopoulos, J.; Bealer, K.; Madden, T.L. BLAST+: Architecture and applications. BMC Bioinform. 2009, 10, 421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilsson, R.H.; Larsson, K.-H.; Taylor, A.F.S.; Bengtsson-Palme, J.; Jeppesen, T.S.; Schigel, D.; Kennedy, P.; Picard, K.; Glöckner, F.O.; Tedersoo, L.; et al. The UNITE database for molecular identification of fungi: Handling dark taxa and parallel taxonomic classifications. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019, 47, D259–D264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gower, JC. Principal coordinates analysis. Wiley StatsRef Stat Ref online. 2014, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Chong, J.; Liu, P.; Zhou, G.; Xia, J. Using MicrobiomeAnalyst for comprehensive statistical, functional, and meta-analysis of microbiome data. Nat. Protoc. 2020, 15, 799–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mauri M, Elli T, Caviglia G, Uboldi G, Azzi M. RAWGraphs: a visualisation platform to create open outputs. In: Proceedings of the 12th biannual conference on Italian SIGCHI chapter. 2017. p. 1–5.

- Wemheuer, F.; Taylor, J.A.; Daniel, R.; Johnston, E.; Meinicke, P.; Thomas, T.; Wemheuer, B. Tax4Fun2: prediction of habitat-specific functional profiles and functional redundancy based on 16S rRNA gene sequences. Environ. Microbiome 2020, 15, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Põlme, S.; Abarenkov, K.; Nilsson, R.H.; Lindahl, B.D.; Clemmensen, K.E.; Kauserud, H.; Nguyen, N.; Kjøller, R.; Bates, S.T.; Baldrian, P.; et al. FungalTraits: a user-friendly traits database of fungi and fungus-like stramenopiles. Fungal Divers. 2020, 105, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, M.J. Permutational Multivariate Analysis of Variance (PERMANOVA); Wiley statsref Stat Ref online. 2014;1–15. [CrossRef]

- Foster ZSL, Weiland JE, Scagel CF, Grünwald NJ. The Composition of the Fungal and Oomycete Microbiome of Rhododendron Roots under Varying Growth Conditions, Nurseries, and Cultivars. Phytobiomes. 2020, 4, 156–164.

- Qin, Y.; Yan, Y.; Cheng, L.; Lu, Y.; Chen, J.; Liu, F.; Tan, J. Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi and Rhizobium Facilitate Nitrogen and Phosphate Availability in Soybean/Maize Intercropping Systems. J. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2023, 23, 2723–2731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, A.; Ku, Y.-S.; Contador, C.A.; Lam, H.-M. The Impacts of Domestication and Agricultural Practices on Legume Nutrient Acquisition Through Symbiosis With Rhizobia and Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi. Front. Genet. 2020, 11, 583954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith SE, Read DJ. Mycorrhizal symbiosis. Academic press; 2010.

- Zhao, B.; Jia, X.; Yu, N.; Murray, J.D.; Yi, K.; Wang, E. Microbe-dependent and independent nitrogen and phosphate acquisition and regulation in plants. New Phytol. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akiyama, K.; Matsuzaki, K.-I.; Hayashi, H. Plant sesquiterpenes induce hyphal branching in arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi. Nature 2005, 435, 824–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bender SF, Schlaeppi K, Held A, Heijden MGA Van Der. Agriculture, Ecosystems and Environment Establishment success and crop growth e ff ects of an arbuscular mycorrhizal fungus inoculated into Swiss corn fields. Agric Ecosyst Environ. 2019, 273, (2018):13–24.

- Zahran, H.H. Rhizobium -Legume Symbiosis and Nitrogen Fixation under Severe Conditions and in an Arid Climate. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 1999, 63, 968–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto AP, Faria JMS, Dordio A V, Carvalho AJP. Organic Farming–a Sustainable Option to Reduce Soil Degradation. Agroecol Approaches Sustain Soil Manag. 2023, 83–143.

- Jindo, K.; Audette, Y.; Olivares, F.L.; Canellas, L.P.; Smith, D.S.; Voroney, R.P. Biotic and abiotic effects of soil organic matter on the phytoavailable phosphorus in soils: a review. Chem. Biol. Technol. Agric. 2023, 10, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiers, E.T.; Duhamel, M.; Beesetty, Y.; Mensah, J.A.; Franken, O.; Verbruggen, E.; Fellbaum, C.R.; Kowalchuk, G.A.; Hart, M.M.; Bago, A.; et al. Reciprocal Rewards Stabilize Cooperation in the Mycorrhizal Symbiosis. Science 2011, 333, 880–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busby, P.E.; Soman, C.; Wagner, M.R.; Friesen, M.L.; Kremer, J.; Bennett, A.; Morsy, M.; Eisen, J.A.; Leach, J.E.; Dangl, J.L. Research priorities for harnessing plant microbiomes in sustainable agriculture. PLOS Biol. 2017, 15, e2001793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartmann, M.; Frey, B.; Mayer, J.; Mäder, P.; Widmer, F. Distinct soil microbial diversity under long-term organic and conventional farming. ISME J. 2014, 9, 1177–1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dangi SR, Allen BL, Jabro JD, Rand TA, Campbell JW, Calderon RB. The Effect of Alternative Dryland Crops on Soil Microbial Communities. Soil Systems 2023, 8, 4.

- Hu, J.; Cyle, K.T.; Miller, G.; Shi, W. Water deficits shape the microbiome of Bermudagrass roots to be Actinobacteria rich. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2023, 99, fiad036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, X.; Raaijmakers, J.M.; Carrión, V.J. Importance of Bacteroidetes in host–microbe interactions and ecosystem functioning. Trends Microbiol. 2023, 31, 959–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Wang, B.; Li, Y.; Jiang, D.; Zhou, Y.; Ding, A.; Zong, Y.; Ling, X.; Zhang, S.; Lu, H. Ubiquity, diversity, and activity of comammox Nitrospira in agricultural soils. Sci. Total. Environ. 2019, 706, 135684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliverio, A.M.; Bissett, A.; McGuire, K.; Saltonstall, K.; Turner, B.L.; Fierer, N. The Role of Phosphorus Limitation in Shaping Soil Bacterial Communities and Their Metabolic Capabilities. mBio 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashmi I, Bindschedler S, Junier P. Firmicutes. In: Beneficial microbes in agro-ecology. Elsevier; 2020. p. 363–96.

- Wang, S.; Meade, A.; Lam, H.-M.; Luo, H. Evolutionary Timeline and Genomic Plasticity Underlying the Lifestyle Diversity in Rhizobiales. mSystems 2020, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idbella, M.; Bonanomi, G. Uncovering the dark side of agriculture: How land use intensity shapes soil microbiome and increases potential plant pathogens. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2023, 192, 105090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hestrin, R.; Kan, M.; Lafler, M.; Wollard, J.; A Kimbrel, J.; Ray, P.; Blazewicz, S.J.; Stuart, R.; Craven, K.; Firestone, M.; et al. Plant-associated fungi support bacterial resilience following water limitation. ISME J. 2022, 16, 2752–2762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, J.; Liang, Z.; Kuzyakov, Y.; Li, W.; He, Y.; Wang, C.; Xiao, Y.; Chen, K.; Sun, G.; Lei, Y. Dissolved organic matter defines microbial communities during initial soil formation after deglaciation. Sci. Total. Environ. 2023, 878, 163171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conradie, T.; Jacobs, K. Seasonal and Agricultural Response of Acidobacteria Present in Two Fynbos Rhizosphere Soils. Diversity 2020, 12, 277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckley, D.H.; Huangyutitham, V.; Nelson, T.A.; Rumberger, A.; Thies, J.E. Diversity of Planctomycetes in Soil in Relation to Soil History and Environmental Heterogeneity. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2006, 72, 4522–4531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonfante, P.; Venice, F. Mucoromycota: going to the roots of plant-interacting fungi. Fungal Biol. Rev. 2020, 34, 100–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Guo, T.; Sheng, K.; Shi, W.; Han, Y.; Wang, Y.; Li, H. Continuous straw return for 8 years mitigates the negative effects of inorganic fertilisers on C-cycling soil bacteria. Eur. J. Soil Sci. 2022, 73, e13322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berendsen, R.L.; Pieterse, C.M.J.; Bakker, P.A.H.M. The rhizosphere microbiome and plant health. Trends Plant Sci. 2012, 17, 478–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, R.; Anand, G.; Gaur, R.; Yadav, D. Plant–microbiome interactions for sustainable agriculture: a review. Physiol. Mol. Biol. Plants 2021, 27, 165–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yates RJ, Abaidoo R, Howieson JG. Field experiments with rhizobia. In Australian Centre for International Agricultural Research; 2016.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).