1. Introduction

Currently, humanity faces unprecedented environmental challenges, where climate change, biodiversity loss, and environmental pollution have become tangible threats to both human health and the planet [

1,

2]. In response to this situation, the United Nations (UN), through the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), emphasizes the need for society at large to contribute to environmental conservation by producing and consuming products that have the least possible impact on the ecosystem [

3,

4].

In this context, organic products have become a prominent choice, not only representing a healthier dietary option but also a crucial approach to reducing the ecological footprint associated with the production and consumption of conventional products [

5,

6]. According to Carrión et al. [

7], organic products refer to foods and agricultural goods that are cultivated, produced, and processed using methods and agricultural practices that exclude the use of synthetic pesticides, chemical fertilizers, and genetically modified organisms. Several authors concur that organic production directly contributes to biodiversity preservation, soil quality improvement, and environmental pollution reduction [

3,

8], as this type of production encourages agricultural practices that promote carbon sequestration in the soil, playing a crucial role in mitigating climate change [

9,

10].

Given the growing significance of environmentally friendly product consumption, the academic community has shown a keen interest in conducting studies aimed at identifying factors associated with the intention to purchase organic products [

6,

7,

11]. To achieve this, various theories have been employed to pinpoint the drivers influencing these consumption behaviors [

1,

2,

12,

13], among which the following stand out: (a) Theory of Reasoned Action, (b) Theory of Planned Behavior, and (c) Theory of Consumption Values [

5,

12,

14].

The Theory of Consumption Values (TCV) holds a significant perspective in the field of consumer behavior, as it focuses on understanding how individual consumer values influence their purchasing decisions. According to this theory, a person’s consumption choices are conditioned by the following values: (a) functional, (b) social, (c) emotional, (d) conditional, and (e) epistemic [

12,

15]. Therefore, TCV emerges as an indispensable tool for the analysis of the values driving purchase decisions, particularly in the realm of organic product consumption [

16].

While the TCV has been widely used in the field of green consumption, its influence on environmental attitudes and the purchase of organic products has not yet been fully addressed [

17]. In response to this, researchers like Hoyos et al. [

11] emphasize the need to employ the TCV and identify the factors influencing the attitudes of consumers with an intention to purchase organic products. Moreover, a review of the literature reveals that, despite the connection between attitudes and purchase intention, there is still a need to identify the factors preceding these attitudes, creating a significant gap in understanding the foundations of sustainable buying behavior [

2,

3,

8,

9,

18,

19]. In consideration of bridging the aforementioned knowledge gaps, the aim of this current research was to identify whether consumption values influence the attitudes of millennials with an intention to purchase organic products.

In order to address the previously stated research objective, this current study aims to answer the following research questions: (a) Do the attitudes of millennials influence their intentions to purchase organic products? (b) Do consumption values influence the attitudes of millennials with an intention to purchase organic products? and (c) Which dimensions of consumption values influence the attitudes of millennials with an intention to purchase organic products?

2. Literature review

2.1. Purchase Intention

Purchase intention (PI) of organic products refers to the desire or predisposition that consumers have to select and acquire products that have been cultivated or produced under environmentally protective standards [

2,

6,

7,

19]. In recent years, the field of organic product consumption has gained significance and academic interest to the extent that a variety of studies have examined the relationship between environmental consciousness and the PI for such products [

5,

13,

15,

20], concluding that consumers with a strong environmental concern are more likely to purchase products that have the least possible impact on the planet [

4,

21].

Studies in the field of consumer psychology have determined that individual values have become conditioning factors that influence the PI for environmentally friendly products [

22,

23,

24,

25], highlighting that when a consumer identifies with values associated with environmental protection, their PI is conditioned by the impact their consumption can have on the ecosystem [

26]. On the other hand, other authors have found that consumers’ environmental attitudes are the primary preceding factor influencing the PI for organic products [

6,

7,

8,

27,

28], revealing that a positive attitude towards environmental issues increases the intention to adopt purchasing behaviors that align with their beliefs [

27,

29].

From the perspective of TCV, the choice of organic products can be seen as an expression of personal values [

25], as consumers who opt for these products often value personal health and environmental sustainability, believing that their purchase choice has an impact beyond their personal satisfaction [

23,

30]. Therefore, consumption values not only relate to the utilitarian or hedonic value of the product but also encompass the expressive and ethical values they represent [

22,

24].

In consideration of the aforementioned, the literature presented below highlights the various theoretical contributions and findings that the scientific community has revealed regarding the influence of consumption value dimensions on the attitudes of consumers with a PI for organic products.

2.2. Environmental Attitude

Attitudes are defined as the positive or negative evaluation individuals have towards a specific behavior [

27]. In the context of sustainable consumption, Environmental Attitude (EA) represent consumers’ evaluation of environmental issues stemming from purchasing and consumption without human consciousness [

7]. Recent studies have tested the influence of EAs on the PI for organic products [

6,

28,

31], demonstrating that consumers with positive attitudes towards environmental sustainability tend to show greater willingness to purchase environmentally friendly products [

11]. Although recent studies have determined a strong association between EA and the PI for environmentally protective products, there are still research inquiries questioning the relationship of these variables [

32]. Given the previously described discrepancy in viewpoints, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H1: Environmental attitudes influence the purchase intentions of Millennials for organic products.

2.2. Consumption Values

The consumption of organic products is a complex and diverse process influenced by standards, consumption habits, and values held by a consumer [

6,

33]. Regarding values, the most prominent and widely used Theory in green consumption studies is the TCV. According to Shet et al. [

16], this theory establishes five types of values that shape an individual’s purchasing decision, which are: (a) functional, (b) social, (c) emotional, (d) conditional, and (e) epistemic.

Although an extensive array of articles has tested the relationship between the values mentioned above and the PI for environmentally protective products [

22,

23,

25], the literature review revealed a lack of studies that have measured all these values within a single construct and identified if these values, when grouped together, influence the attitudes of consumers with a PI for organic products. Furthermore, other researchers have determined that the influence of consumption values has not been fully explored within the context of organic foods [

17] and their relationship with environmental attitudes has not been tested either [

11,

34]. In consideration of the above, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H2: Consumption values directly influence the environmental attitudes of millennials.

2.2.1. Dimensions of Consumption Values

Functional Values (FV) refer to the perception of utilitarian or economic benefits during consumption [

16]. In the context of consumer decision-making, FV often dominate when it comes to purchasing items that meet consumer demands [

17]. This is because consumers seek products that fulfill their basic needs and provide tangible value [

35]. In the green context, consumers evaluate the price-quality relationship and other functional attributes that environmentally friendly products can offer [

18,

36]. While the literature links functional values to ecological purchase intention [

13], no studies have proven their effect on pro-environmental attitudes [

11].

Social Values (SV) represent a product’s utility in projecting a desired image within a social group [

16]. This type of value relates to the perceived social utility a consumer gains from alternatives associated with a particular social group [

37]. This value can be positive or negative and may be influenced by factors such as the group’s image, the consumer’s personal beliefs, and social norms [

35]. For some researchers, organic products can enhance the self-image of consumers identified with environmental protection [

19,

38], thus demonstrating the direct impact of these values on the PI for environmentally aligned products [

25]. However, according to Hoyos et al. [

11], there is no evidence of their effect on consumers’ ecological attitudes.

Emotional Values (EV) are associated with feelings and emotional states during the purchase [

16]. This value type refers to a product or service’s ability to evoke feelings or states in consumers, associated with the emotions that matter most to them [

37]. This is why consumer product companies seek to stimulate consumers’ emotions to drive their purchasing behaviors [

36]. For instance, the consumption of organic products can generate a moral satisfaction in the consumer for contributing to the environmental well-being of the planet [

17,

39,

40]. While the literature supports the influence of this value on green buying [

13], its impact on attitudes has not been demonstrated [

11].

Conditional Values (CV) represent a product’s utility under specific purchase situations [

16], such as promotions or government policies in the ecological context [

41]. Therefore, this value refers to the set of situations that consumers must face to make a decision [

35]. Although the effect of this value on green PI has been proven [

5], some studies contradict this finding [

19,

40], indicating the presence of discrepancies regarding the influence of CV on the PI for environmentally friendly products. Therefore, Hoyos et al. [

11] highlight the need for further research analyzing the relationship between CV and consumers’ environmental attitudes.

Epistemic Values (EpV) refer to the search for and appreciation of knowledge and understanding that consumers gain through their shopping and product usage experiences [

16]. In the context of green consumption, these values play a crucial role because consumers who value knowledge and understanding tend to educate themselves more about the benefits and processes behind organic products [

42,

43]. This leads consumers to see the need to understand how the consumption of organic products contributes to personal health, environmental well-being, and sustainability [

35]. Therefore, EpV can significantly influence the PI for organic products, as consumers seek products that not only satisfy their immediate needs but also provide a deeper understanding of their impact on health and the environment [

44].

Taking into account the previously mentioned factors and assuming that these values encourage more conscious consumption and motivate consumers to make decisions based on the values they identify with, the following hypotheses are proposed:

H2a: Functional values influence the environmental attitudes of Millennials.

H2b: Social values influence the environmental attitudes of Millennials.

H2c: Emotional values influence the environmental attitudes of Millennials.

H2d: Conditional values influence the environmental attitudes of Millennials.

H2e: Epistemic values influence the environmental attitudes of Millennials.

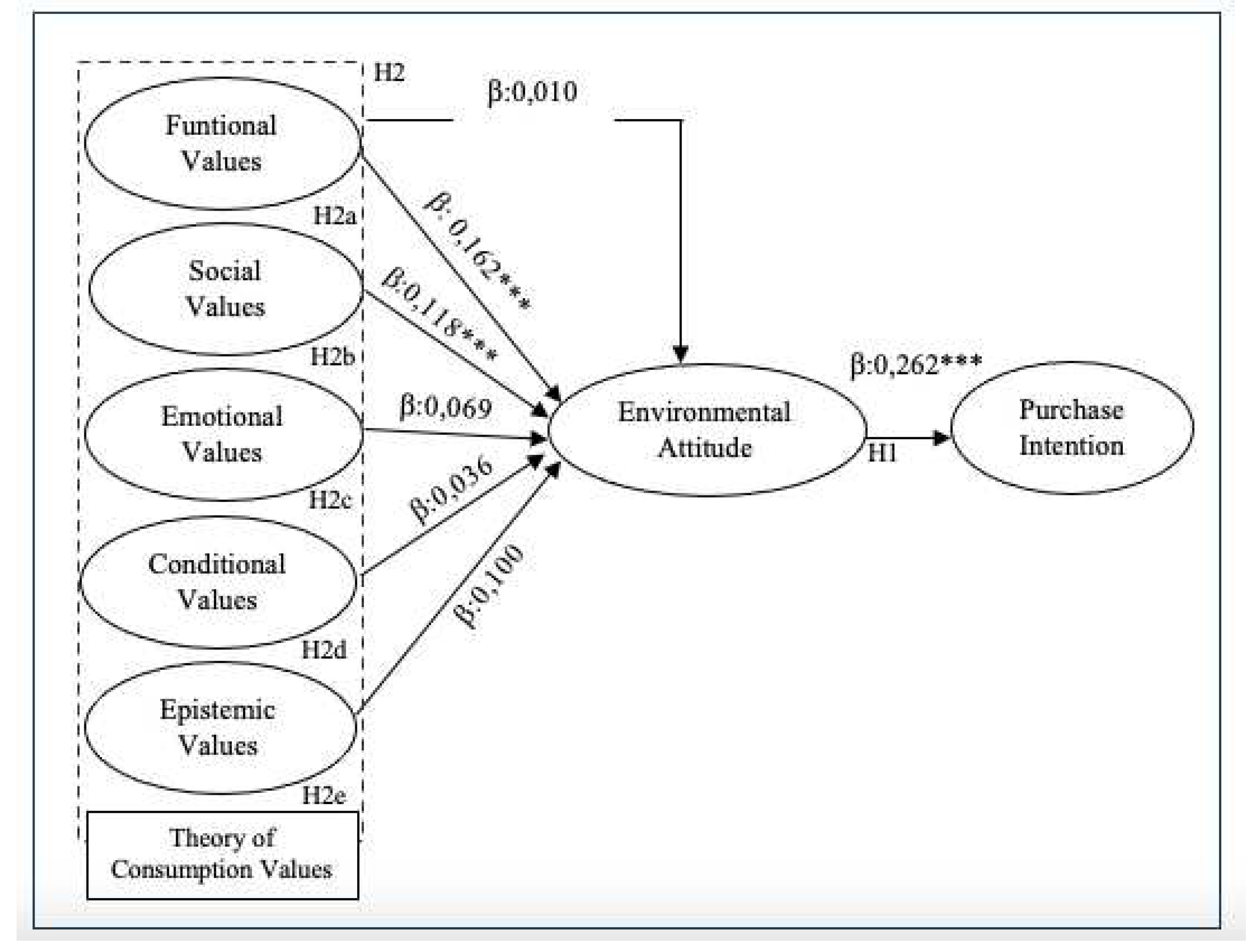

2.3. Conceptual Model

In order to address the research questions of the study, the hypothetical research model is presented below. (See

Figure 1).

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Instrument design and data collection

This study adopted a quantitative approach with a correlational scope and a cross-sectional design. Data were collected through a survey consisting of 27 questions, including 4 demographic questions and 23 questions related to the hypothetical variables in the model. These questions were assessed using a five-point Likert scale. The questions used to measure the study variables were based on previous research on organic consumption (See

Appendix A). To ensure the questionnaire’s validity, it underwent a validation process, which included review by a panel of experts comprising two research specialists and two marketing experts. Additionally, a pilot test was conducted with the participation of 25 millennial consumers. In this test, no observations were received regarding the questionnaire.

The study’s target population consisted of millennials residing in the city of Lima, Peru. The choice of this population cohort is grounded in existing literature on ecological consumption, which has pointed out that millennials are the generation most committed to environmental issues and that their buying behavior is aligned with organic products [

6,

7]. The survey was administered in person during the month of August 2023, using a probabilistic sampling method that selected 521 participants who expressed their willingness to participate in the research through informed consent. A total of 12 surveys were excluded due to inconsistencies in their responses; therefore, 509 (98%) surveys were considered valid for statistical analysis.

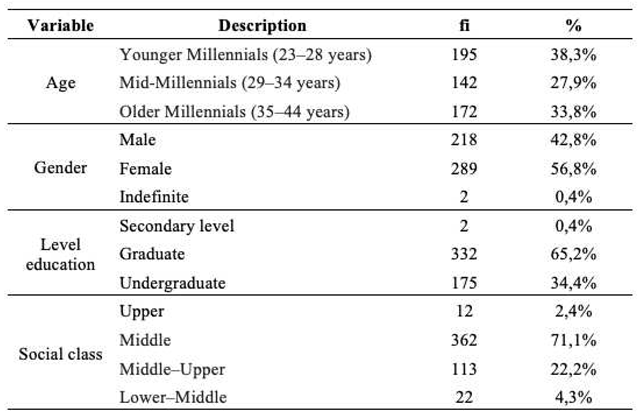

Regarding the demographic characteristics of the respondents, it is important to note that the study was conducted in Lima, Peru, with the effective participation of 509 respondents. In order to balance the study sample of millennials, the criteria from Carrión y Arias [

6] were adopted, which categorizes millennials into three sub-population cohorts (older, middle, and younger millennials). As inclusion criteria for the study sample, only millennials residing in Lima who are considered frequent consumers of organic products were considered, while consumers from other population cohorts and those who occasionally consume organic products were excluded. The details of this distribution can be seen in

Table 1.

3.2. Internal consistency of the instrument and Exploratory Factor Analysis

For the statistical analysis, recent articles on organic consumption published in high-impact academic journals were used as a basis [

6,

7,

11]. Additionally, a Cronbach’s Alpha test was conducted to assess the internal consistency of the questionnaire used. The evaluation of internal consistency revealed that all the questions had an appropriate factor loading, and their constructs exceeded the threshold of 0,70 as established in the literature [

45]. Furthermore, to confirm that the questions used in the questionnaire were grouped within their corresponding constructs, an Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) was conducted. The Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) test yielded a value of 0.707 with a significance level of 0.001 (p <0.05). Through the application of a rotated component matrix, it was evident that the questions clustered into seven dimensions with a percentage of 74.09%, exceeding the recommended 60% threshold by [

46]. This confirms that each of the questions in the survey provides significant information for each of its variables.

3.3. Data analysis

As part of the statistical analysis of the research, a Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) was conducted to test the validity of the hypothesized model. Initially, the convergent validity of the model was assessed, where the Composite Reliability (CR) and Average Variance Extracted (AVE) should be greater than 0.70, and the AVE values should be less than CR to confirm convergent validity. Furthermore, to evaluate the discriminant validity of the model, the Square Root of AVE (SRAVE) was calculated, where the obtained values should be greater than the correlations between each pair of constructs in the model [

45,

47,

48,

49].

To approve or reject the model hypotheses, a Structural Equation Model (SEM) was conducted in AMOS 24 using the maximum likelihood method. At this point, it was verified that the Goodness-of-fit indices of the hypothesized model met the following criteria. Firstly, the relative χ2 value with respect to degrees of freedom (χ2/df) should be less than 3.0. Secondly, the Comparative Fit Index (CFI), Tucker–Lewis Index (TLI), and Normed Fit Index (NFI) should be greater than 0.90. Thirdly, the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) should be less than 0.80 [

48,

50,

51].

4. Results

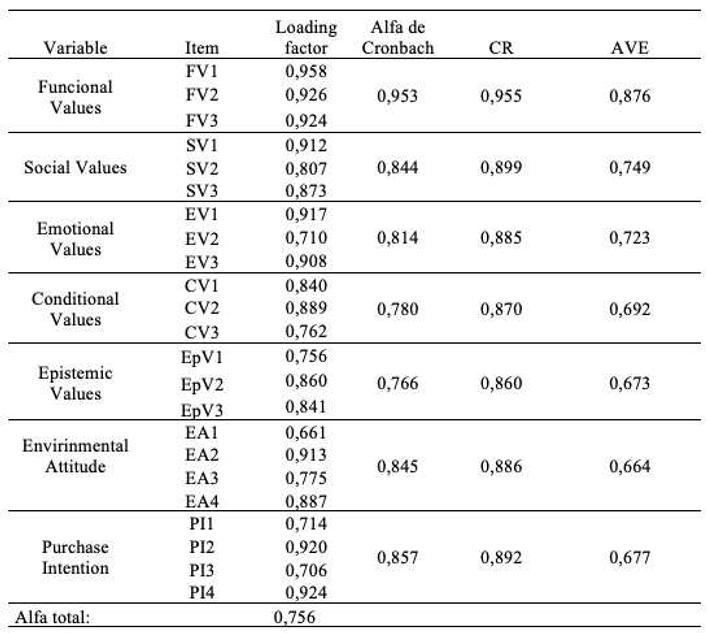

4.1. Estimation of the measurement model

The measurement model, consisting of seven constructs (FV, SV, EV, VC, EpV, EA, PI), was evaluated through a CFA. It was necessary to determine the instrument’s reliability and the convergent validity of the model using Cronbach’s Alpha values ≥ 0.7, CR ≥ 0.7, and AVE ≥ 0.5 [

45,

47,

48]. The Cronbach’s Alpha and CR values exceeded 0.70, while AVE was greater than 0.50 and less than CR, as recommended in the literature [

47,

48,

49,

50]. See

Table 2.

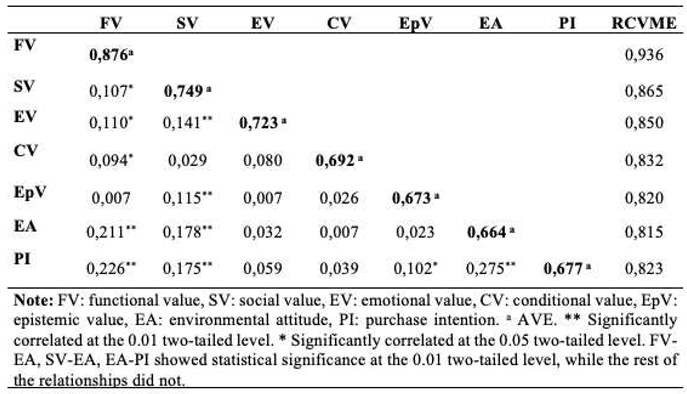

To test the discriminant validity of the model, the bivariate correlational values of the constructs in the hypothesized model were first calculated, and then the square root of each AVE value (SR AVE) was computed. When the SR AVE values are greater than the correlation values between each pair of constructs, the presence of discriminant validity in the model is confirmed [

6,

7,

11,

45,

47,

48]. See

Table 3.

4.2. Structural Equation Modeling.

After testing the convergent and discriminant validity of the research model, a SEM was developed to either confirm or reject the study’s hypotheses. Initially, it was tested whether the dimensions of TCV as a whole or as a second-order variable (integrating the five dimensions into a single construct) were related to the variable EA. The results obtained through the analysis in AMOS 24 showed that the model did not meet the goodness-of-fit indices, confirming the lack of a relationship between TCV as a whole and EA.

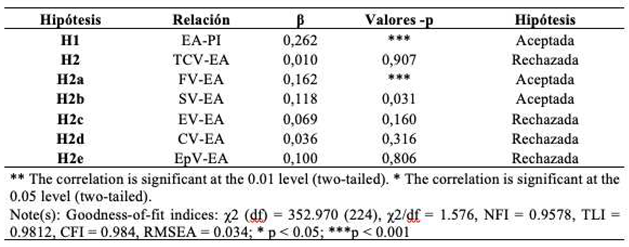

Considering the above, the statistical analysis continued, aiming to test the relationship of the five dimensions separately with EA and PI. The results derived from the maximum likelihood estimation in AMOS 24 showed that the data met the following goodness-of-fit indices: χ2 (df)=352.970 (224), χ2/d =1.576, NFI = 0.9578, TLI = 0.9812, CFI = 0.984, RMSEA = 0.034; * p < 0.05; ***p <0.001. After analyzing the relationships between the seven variables in the hypothesized model and considering the significance values (p <0.05), three hypotheses were accepted, and four were rejected.

The study found that EA (β =0.262; p<0.05) influences PI. Also, the study showed that TCV as a whole has no direct relationship with EA, and when analyzing the dimensions of TCV separately, it was found that FV (β =0.162; p< 0.05) and SV (β =0.118; p<0.05) influence EA, while EV (β =0.069; p>0.05), CV (β =0.036; p>0.05), and EpV (β =0.100; p>0.05) do not have an influence on EA. (See

Table 4 and

Figure 2)

5. Discussion

Understanding the values that drive the selection of ecological products not only benefits companies in strategic marketing decisions and product development but also contributes to promoting more sustainable practices in society, aligning individual values with responsible consumption and environmental care. In consideration of the above, the present study allowed us to confirm the following:

The study confirmed that EA are related to IC, thus supporting H1, meaning that environmental attitudes influence the intentions of millennials to purchase organic products. This finding adds to the variety of research that has demonstrated that pro-environmental attitudes are one of the key factors influencing the intention to purchase organic products [

11,

28,

31]. Therefore, it reaffirms that Millennials believe that consuming organic products helps to save nature, and environmental protection is important to them when selecting a product to consume [

6,

7,

52]. This contradicts research that still questions the role of EA in PI [

32].

On the other hand, the statistical analyses identified that the dimensions of the TCV cannot be measured as a single construct, thus rejecting H2, meaning that TCV do not directly influence millennials’ EA. Therefore, their relationship with EA must be measured independently, confirming that the five consumer values are independent, and it is not advisable to test them collectively regarding consumer attitude [

35]. This aligns with the observations made by Chinelato et al. [

44], who indicated that Consumer Values generally influence consumer decisions due to the individual impact that can occur among its dimensions.

Furthermore, the study tested the relationship between FV and EA, thus accepting H2a, which indicates that FV influence EA. This confirms that consumers take into consideration the functional attributes that products associated with environmental protection offer [

18,

21,

36], analyzing during the purchasing process that the product quality is good and it is not made with harmful substances [

34,

53]. This finding aligns with what several authors have determined, that the literature on green consumption has found a positive relationship between FV of organic foods and consumer attitudes [

9,

17].

Continuing with the analysis of the dimensions of TCV, the study’s results identified that SV are related to EA of consumers, thus accepting H2b. This means that SV influence the EA of Millennials. Therefore, it confirms that consumers find it important that a product allows them to project a desired image within a social group [

7,

19,

28,

37,

38]. Thus, it corroborates that, for Millennials, social approval and the positive impression they seek to create within their social circles have become factors that shape their pro-environmental attitudes [

19,

38,

53]. This finding supports the stance of Roh et al. [

17], who demonstrated that SV influence consumer attitudes.

On the other hand, the study revealed that EV are not related to EA, thus rejecting H2c. In other words, EV do not influence the EA of Millennials. This finding highlights that emotional feelings and affective states are not influential factors in environmental attitudes and moral satisfaction among Millennials. This contradicts several scholars who have determined that the consumption of organic products generates moral satisfaction in consumers and contributes to the environmental well-being of the planet [

17,

39,

40]. It also contradicts studies that have found that EV influence the attitudes of consumers who consume environmentally aligned food products [

9,

19].

Regarding CV, the study confirmed that these values are not related to EA, therefore rejecting H2d. In other words, CV do not influence the EA of Millennials. This finding emphasizes that, for Millennials, monetary factors, incentives, or government subsidies are not conditioning elements within their EA. Thus, it supports the determination that CV do not influence environmental behaviors [

19,

40], contradicting several authors who determined that promotional discounts [

54] and government policies [

41] condition consumers to purchase organic products.

In the case of EpV, it was found that these values are not related to EA. Hence, rejecting H2e, meaning that EpV do not influence the EA of Millennials. Therefore, it confirms that consumers do not distrust the labeling and certifications of organic products, and they do not require substantial product information to stimulate their attitudes toward environmental protection. This finding contrasts with research that has shown that consumers value knowledge and continuously seek information about the benefits of organic products [

42,

43].

6. Conclusion

The present study contributed to the field of knowledge about the consumption of organic products, and through the conducted statistical analyses, it provided answers to the research questions. Regarding the question: (a) Do the attitudes of Millennials influence the intentions to purchase organic products? It was found that EA significantly influence the PI of Peruvian Millennials. This confirms that for this group of consumers, the consumption of organic products is vital to contribute to environmental protection. On the other hand, the study answered the question: (b) Do consumption values influence the attitudes of Millennials with the intention to purchase organic products? The response was that the five dimensions of TCV (analyzed as a whole) do not directly influence the PI of Peruvian Millennials. Finally, the study also addressed the question: (c) Which dimensions of consumption values influence the attitudes of Millennials with the intention to purchase organic products? It concluded that FV and SV influence the EA of Millennials with PI, while EV, CV, and EpV do not.

This study has theoretical, practical, and social implications. From a theoretical perspective, the findings reinforce the academic literature on the consumption of organic products, which has highlighted that EA is one of the major factors influencing the PI of Millennials, and the values that stimulate these attitudes are FV and SV. Thus, it confirms that the dimensions of the TCV, due to their particular characteristics, should be measured directly. From a practical standpoint, the study provides valuable information for the business field by revealing which values stimulate the attitudes of Millennials who identify with the consumption of organic products. This can help in designing marketing strategies aligned with the functionality and social contributions that products can offer to consumers and, consequently, to the environment. In terms of social implications, the study offers important insights for social and governmental organizations, demonstrating that values can be motivating factors for Peruvian consumers to become aware of environmental issues related to traditional product consumption and opt for organic product consumption.

As part of the study’s limitations, it is acknowledged that surveying only Millennials does not allow for the generalization of behaviors across an entire population. Considering that this study excluded population cohorts such as the Generation Z (centennials), who have become the new consumers and the focus of new research on organic product consumption, future research is recommended to conduct studies that analyze the purchasing behaviors of various generational populations to identify which of these population cohorts has a greater environmentally aligned purchasing behavior. It would be important to investigate whether environmental awareness and green self-identity influence the environmental attitudes of millennials with green purchasing intentions. This would help expand the knowledge about the factors that shape consumer attitudes.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed equally to each of the steps: conceptualization, methodology, validation, formal analysis, investigation, data curation, writing - original draft, review, and editing -, visualization, supervision, and project administration. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the authors.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of COMITÉ DE ÉTICA CIENTÍFICA DEL COLEGIO DE ECONOMISTAS DE CAJAMARCA (Informe N◦ 005/2024- Protocol (005/2024) for studies involving humans.

Informed Consent Statement

The study was developed based on the Declaration of Helsinki, which promoted respect for the participants and their right to voluntary participation in the research. For which, your informed consent was requested before the application of the questionnaire.

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

We thank the College of Economists of Cajamarca—Peru, for having endorsed this research through its college’s ethics committee.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Survey qestions.

Table A1.

Survey qestions.

| Constructo: Valores de consumo |

| Ítem. |

Pregunta |

Autor |

| VF1 |

El producto alimenticio orgánico tiene una calidad estándar esperable. |

Adaptado de

Qasim et al.,

(2019). |

| VF2 |

El producto alimenticio orgánico está hecho de sustancias no peligrosas. |

| VF3 |

El sabor de la comida orgánica es bueno. |

| VS1 |

La compra de productos alimenticios orgánicos me ayudará a obtener la aprobación social. |

| VS2 |

La compra de productos alimenticios orgánicos causará una impresión positiva en otras personas. |

| VS3 |

La compra de productos alimenticios orgánicos mejorará la forma en que me perciben. |

| VE1 |

Comprar el producto alimenticio orgánico en lugar de productos convencionales sería como hacer una buena contribución personal a algo mejor. |

| VE2 |

Comprar el producto alimenticio orgánico en lugar de productos convencionales se sentiría como lo moralmente correcto. |

| VE3 |

Comprar el producto alimenticio orgánico en lugar de los productos convencionales me haría sentir mejor persona. |

| VC1 |

Compraría productos alimenticios orgánicos si fueran fáciles de adquirir. |

| VC2 |

Compraría el producto alimenticio orgánico en lugar de los productos convencionales en condiciones ambientales cada vez peores. |

| VC3 |

Compraré productos alimenticios orgánicos en lugar de sustitutos convencionales si se ofrecen a una tarifa subsidiada. |

| VE1 |

Prefiero comprobar las etiquetas ecológicas y las certificaciones de los productos alimenticios orgánicos antes de comprarlos. |

| VE2 |

Preferiría obtener información sustancial sobre productos alimenticios orgánicos antes de comprarlos. |

| VE3 |

Estoy dispuesto a buscar información novedosa. |

| Constructo: Actitud |

| Ítem. |

Pregunta |

Autor |

| AC1 |

Creo que los productos orgánicos ayudan a salvar la naturaleza y sus recursos. |

Adaptado de Carrión y Arias (2022). |

| AC2 |

La protección del medio ambiente es importante para mí cuando compro productos. |

| AC3 |

Tengo una actitud favorable hacia la compra de productos orgánicos. |

| AC4 |

Si puedo elegir, prefiero un producto orgánico a un producto convencional. |

| Constructo: Intención de compra |

| Ítem. |

Pregunta |

Autor |

| IC1 |

Considero comprar productos orgánicos porque son menos contaminantes. |

Adaptado de Carrión y Arias (2022). |

| IC2 |

Considero cambiar a otras marcas por razones ecológicas. |

| IC3 |

Tengo la intención de comprar productos orgánicos. |

| IC4 |

Tengo la intención de cambiar a una versión orgánica de un producto. |

References

- Groening, C.; Sarkis, J.; Zhu, Q. Green marketing consumer-level theory review: A compendium of applied theories and further research directions. J. Clean. Prod 2018, 172, 1848–1866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nosi, C.; Zollo, L.; Rialti, R.; Ciappei, C. Sustainable consumption in organic food buying behavior: The case of quinoa. Br. Food J. 2020, 122, 976–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhary, R. Green buying behavior in India: An empirical analysis. J. Glob. Responsib. 2018, 9, 179–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, H.; Dung, H. The formation of attitudes and intention towards green purchase: An analysis of internal and external mechanisms. Cogent Business & Management 2023, 10, 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Han, H.; Yu, J.; Kim, W.; Koo, C. Environmental corporate social responsibility and the strategy to boost the airline’s image and customer loyalty intentions. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing 2019, 36, 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Carrión Bósquez, N.G.; Arias-Bolzmann, L.G. Factors influencing green purchasing inconsistency of Ecuadorian millennials. Br. Food J. 2022, 124, 2461–2480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrión Bósquez, N.G.; Arias-Bolzmann, L.G.; Martínez Quiroz, A.K. The influence of price and availability on university millennials’ organic food product purchase intention. Br. Food J. 2023, 125, 536–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taufique, K.M.R.; Vaithianathan, S. A fresh look at understanding Green consumer behavior among young urban Indian consumers through the lens of Theory of Planned Behavior. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 183, 46–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashif, U.; Hong, C.; Naseem, S. Assessment of millennial organic food consumption and moderating role of food neophobia in Pakistan. Curr. Psychol. 2021, 42, 1504–1515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Días, C.; Brito, L.; Nuñez, L.; Rodrigues, C.; Brito, L; Nunes, L. Soil carbon sequestration in the context of climate change mitigation: A review. Soil Systems. 2023, 7, 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Hoyos-Vallejo, C.A.; Carrión-Bósquez, N.G.; Ortiz-Regalado, O. The influence of skepticism on the university Millennials’ organic food product purchase intention. Br. Food J. 2023, 125, 3800–3816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liobikiene, G.; Bernatonienė, J. Why determinants of green purchase cannot be treated equally? The case of green cosmetics: Literature review. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 162, 109–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, J.; Modi, A.; Patel, J. Predicting green product consumption using theory of planned behavior and reasoned action. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2016, 29, 123–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adhitiya, L.; Astuti, R. The Effect of Consumer Value on Attitude Toward Green Product and Green Consumer Behavior in Organic Food. IPTEK Journal of Proceedings Series 2019, 5, 193–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, Y.; Rahman, Z. Factors affecting green purchase behaviour and future research directions. Int. Strateg. Manag. Rev. 2015, 3, 128–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheth, J.; Newman, B.; Gross, B. Why we buy what we buy: A theory of consumption values. Journal of Business Research 1991, 22, 159–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roh, T.; Seok, J.; Kim, Y. Unveiling ways to reach organic purchase: Green perceived value, perceived knowledge, attitude, subjective norm, and trust. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2022, 67, 102988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, E.A.d.M.; Alfinito, S.; Curvelo, I.C.G.; Hamza, K.M. Perceived value, trust and purchase intention of organic food: A study with Brazilian consumers. Br. Food J. 2020, 122, 1070–1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woo, E.; Kim, Y.G. Consumer attitudes and buying behavior for green food products: From the aspect of green perceived value (GPV). Br. Food J. 2019, 121, 320–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Y.; Wu, W.; Pham, T. Examining the moderating effects of green marketing and green psychological benefits on customers’ green attitude, value and purchase intention. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, Y.; Uniyal, D.P.; Sangroya, D. Investigating consumers’ green purchase intention: Examining the role of economic value, emotional value and perceived marketplace influence. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 328, 129638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haws, K.; Winterich, K.; Naylor, R. Seeing the world through GREEN-tinted glasses: Green consumption values and responses to environmentally friendly products. Journal of consumer psychology 2014, 2, 336–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivapalan, A.; Von der Heidt, T.; Scherrer, P.; Sorwar, A. A consumer values-based approach to enhancing green consumption. Sustainable Production and Consumption 2021, 28, 699–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halder, P.; Hansen, E.; Kangas, J.; Laukkanen, T. How national culture and ethics matter in consumers’ green consumption values. J. Clean. Prod 2020, 265, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Chen, H.; Long, R.; Yang, J. How does government regulation shape residents’ green consumption behavior? A multi-agent simulation considering environmental values and social interaction. Journal of Environmental Management 2023, 331, 117231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, N.; Saha, R.; Sreedharan, V.R.; Paul, J. Relating the role of green self-concepts and identity on green purchasing behaviour: An empirical analysis. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2020, 29, 3203–3219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaiswal, D.; Kant, R. Green purchasing behaviour: A conceptual framework and empirical investigation of Indian consumers. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2018, 41, 60–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palomino, H.; Barcellos, L. Personal Variables in Attitude toward Green Purchase Intention of Organic Products. Foods 2024, 13, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carducci, A.; Fiore, M.; Azara, A.; Bonaccorsi, G.; Bortoletto, M.; Caggiano, G.; Calamusa, A.; De Donno, A.; De Giglio, O.; Dettori, M.; et al. Pro-environmental behaviors: Determinants and obstacles among Italian university students. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 3306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, W.; Kumar, S.; Pandey, N.; Verma, D.; Kumar, D. Evolution and trends in consumer behaviour: Insights from Journal of Consumer Behaviour. Journal of Consumer Behaviour 2022, 22, 217–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amalia, F.A.; Sosianika, A.; Suhartanto, D. Indonesian millennials’ halal food purchasing: Merely a habit? Br. Food J. 2020, 122, 1185–1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Testa, F.; Sarti, S.; Frey, M. Are green consumers really green? Exploring the factors behind the actual consumption of organic food products. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2019, 28, 327–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peattie, K. Green Consumption: Behavior and Norms. Annual Review of Environment and Resources 2010, 35, 195–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swetarupa, C.; Naman, S.; Pradip, S.; Bidyut, J. Impact of Green Consumption Value, and Context-Specific Reasons on Green Purchase Intentions: A Behavioral Reasoning Theory Perspective. Journal of Global Marketing 2022, 4, 285–305. [Google Scholar]

- Souki, G.; Chinelato, F.; Gonçalves, C. Sharing is entertaining: the impact of consumer values on video sharing and brand equity. Journal of Research in Interactive Marketing 2022, 1, 118–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sangroya, D.; Nayak, J.K. Factors influencing buying behaviour of green energy consumer. Journal of Cleaner Production 2017, 151, 393–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamid, A. A study on the relationship between consumer attitude, perceived value and green products. Iranian Journal of Management Studies 2014, 2, 329–342. [Google Scholar]

- Bennett, R.; Vijaygopal, R. Consumer attitudes towards electric vehicles. European Journal of Marketing 2018, 3, 499–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.N.; Mohsin, M. The power of emotional value: Exploring the effects of values on green product consumer choice behavior. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 150, 65–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbar, A.; Ali, S.; Ahmad, M.; Akbar, M.; Danish, M. Understanding the antecedents of organic food consumption in Pakistan: Moderating role of food neophobia. International journal of environmental research and public health 2019, 16, 4043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, Y.; Qin, Z.; Yuan, Q. The impact of eco-label on the young Chinese generation: The mediation role of environmental awareness and product attributes in green purchase. Sustainability 2019, 11, 973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Ge, J. Electric vehicle development in Beijing: an analysis of consumer purchase intention. J. Clean. Prod 2019, 216, 361–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deliana, Y.; Rum, I. How does perception on green environment across generations affect consumer behaviour? A neural network process. International Journal of consumer studies 2019, 43, 358–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chinelato, F.; Gonçalves, C.; Randt, D. Why is sharing not enough for brands in video ads? A study about commercial video ads’ value drivers. Spanish Journal of Marketing-ESIC 2023, 3, 407–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chión, S.; Charles, V. Analítica de Datos Para la Modelación Estructural; Pearson Education: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Streiner, D.L. Starting at the beginning: An introduction to coefficient alpha and internal consistency. J. Personal. Assess. 2003, 80, 99–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ping Jr, R.A. On assuring valid measures for theoretical models using survey data. J. Bus. Res. 2004, 57, 125–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murtagh, F.; Heck, A. Multivariate Data Analysis; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012; Volume 131. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, J.C.; Gerbing, D.W. Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychol. Bull. 1988, 103, 411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, B.M. Structural Equation Modeling with Mplus: Basic Concepts, Applications, and Programming; Routledge: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Carrión-Bósquez, N.; Veas-González, I.; Naranjo-Armijo, F.; Llamo-Burga, M.; Ortiz-Regalado, O.; Ruiz-García, W.; Guerra-Regalado, W.; Vidal-Silva, C. Advertising and Eco-Labels as Influencers of Eco-Consumer Attitudes and Awareness—Case Study of Ecuador. Foods 2024, 2, 228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qasim, H.; Yan, L.; Guo, R.; Saeed, A.; Ashraf, B. The defining role of environmental self-identity among consumption values and behavioral intention to consume organic food. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2019, 16, 1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, A.; Roy, M. Leveraging factors for sustained green consumption behavior based on consumption value perceptions: testing the structural model. J. Clean. Prod 2015, 95, 332–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).