Submitted:

03 December 2024

Posted:

04 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

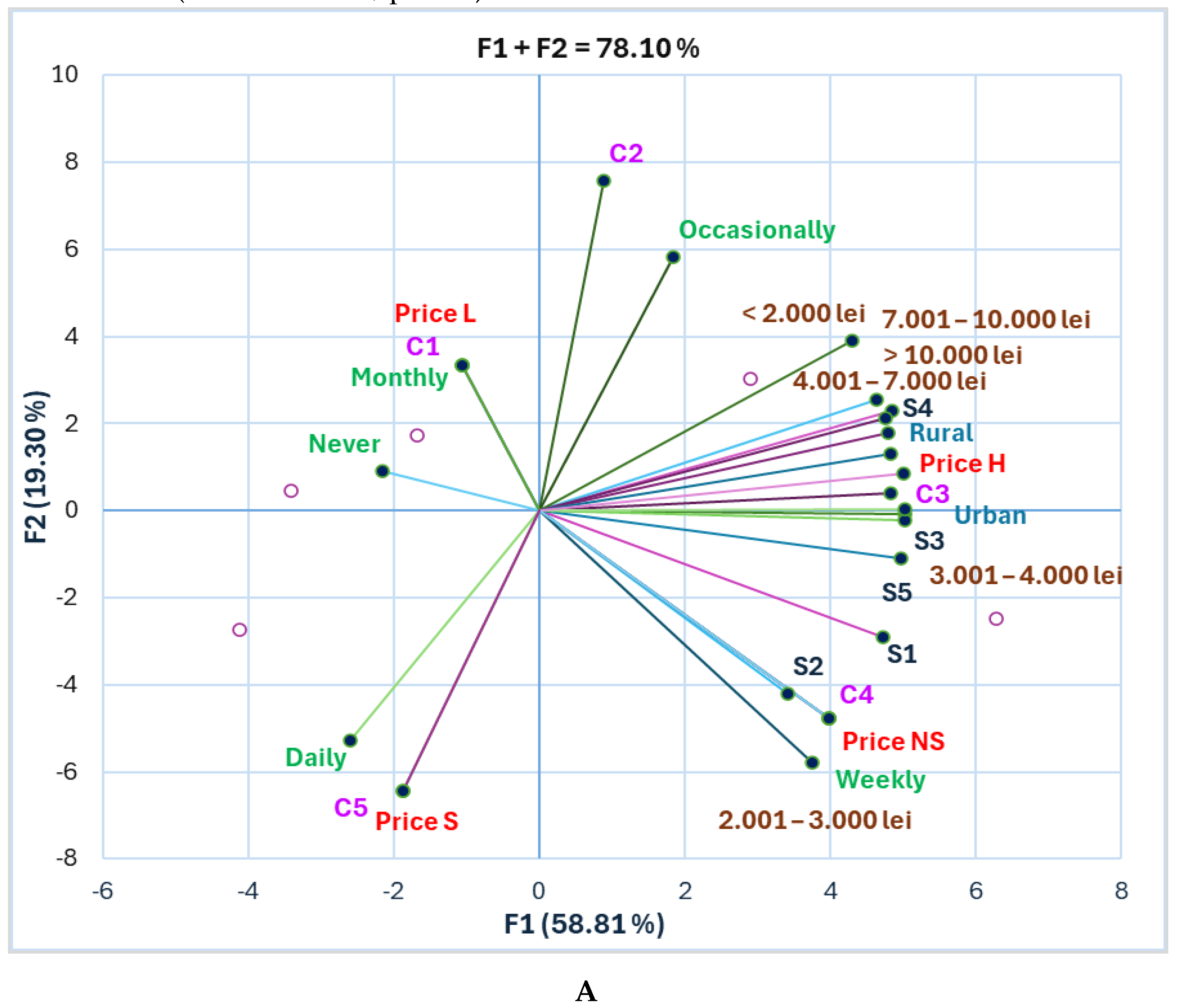

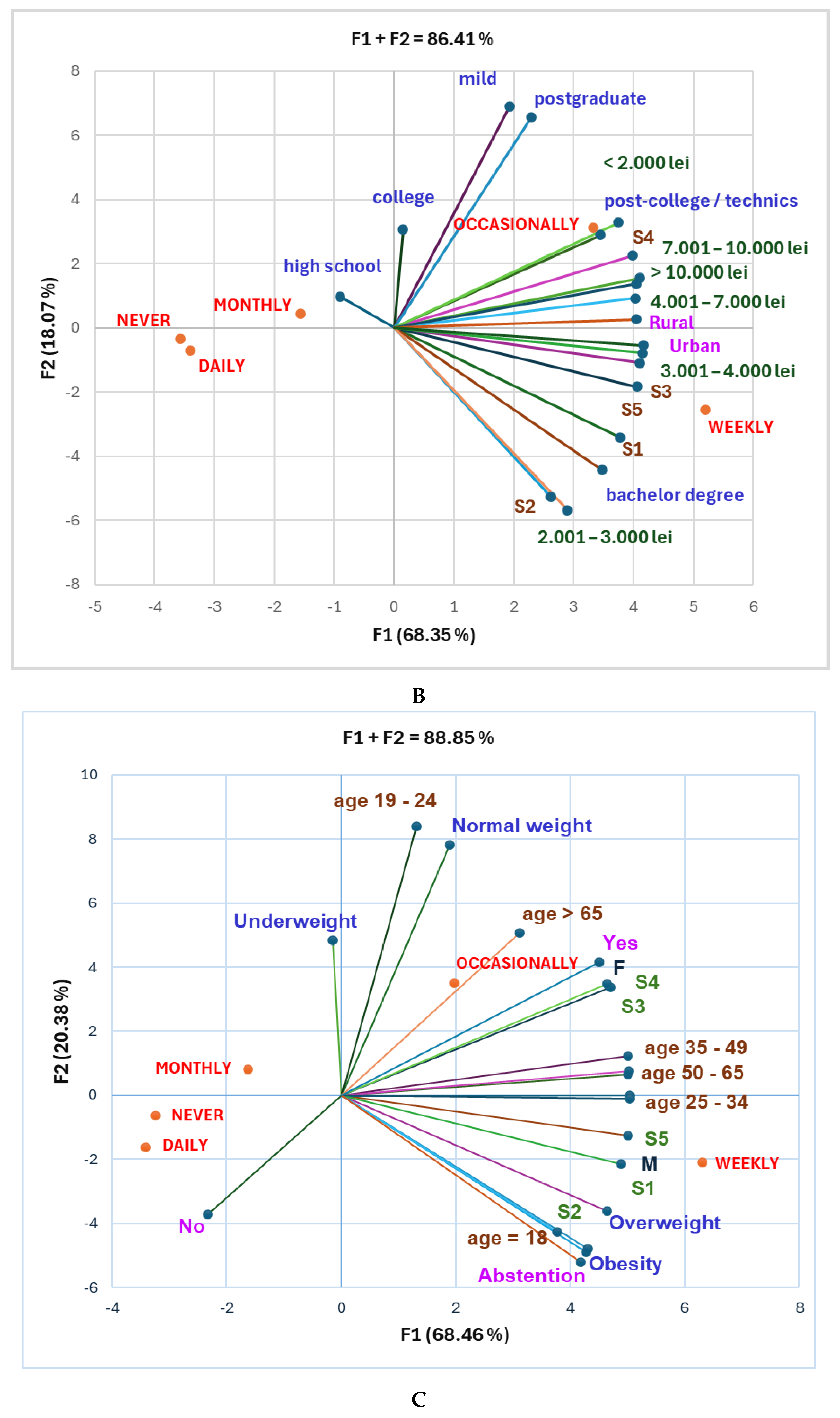

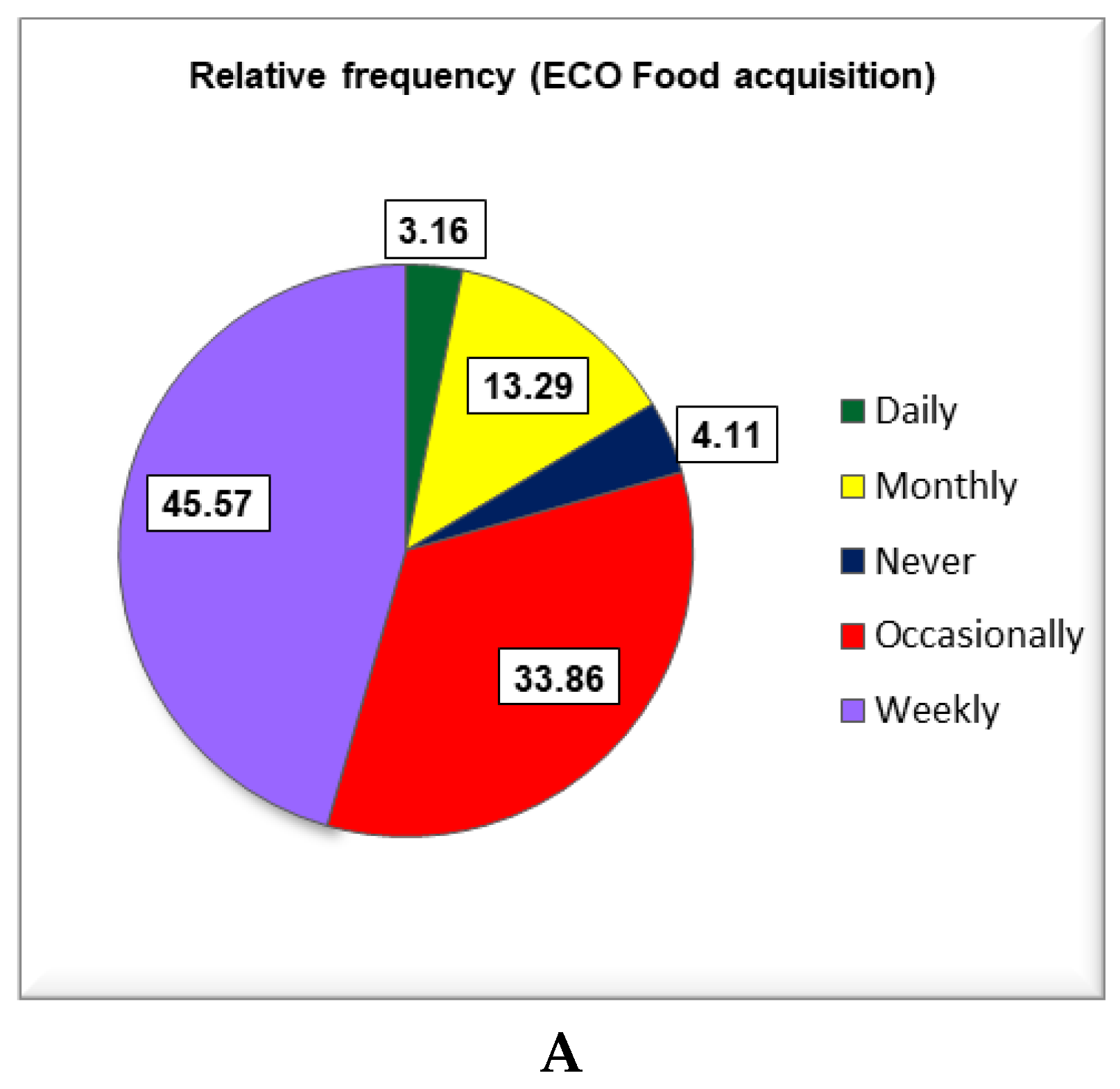

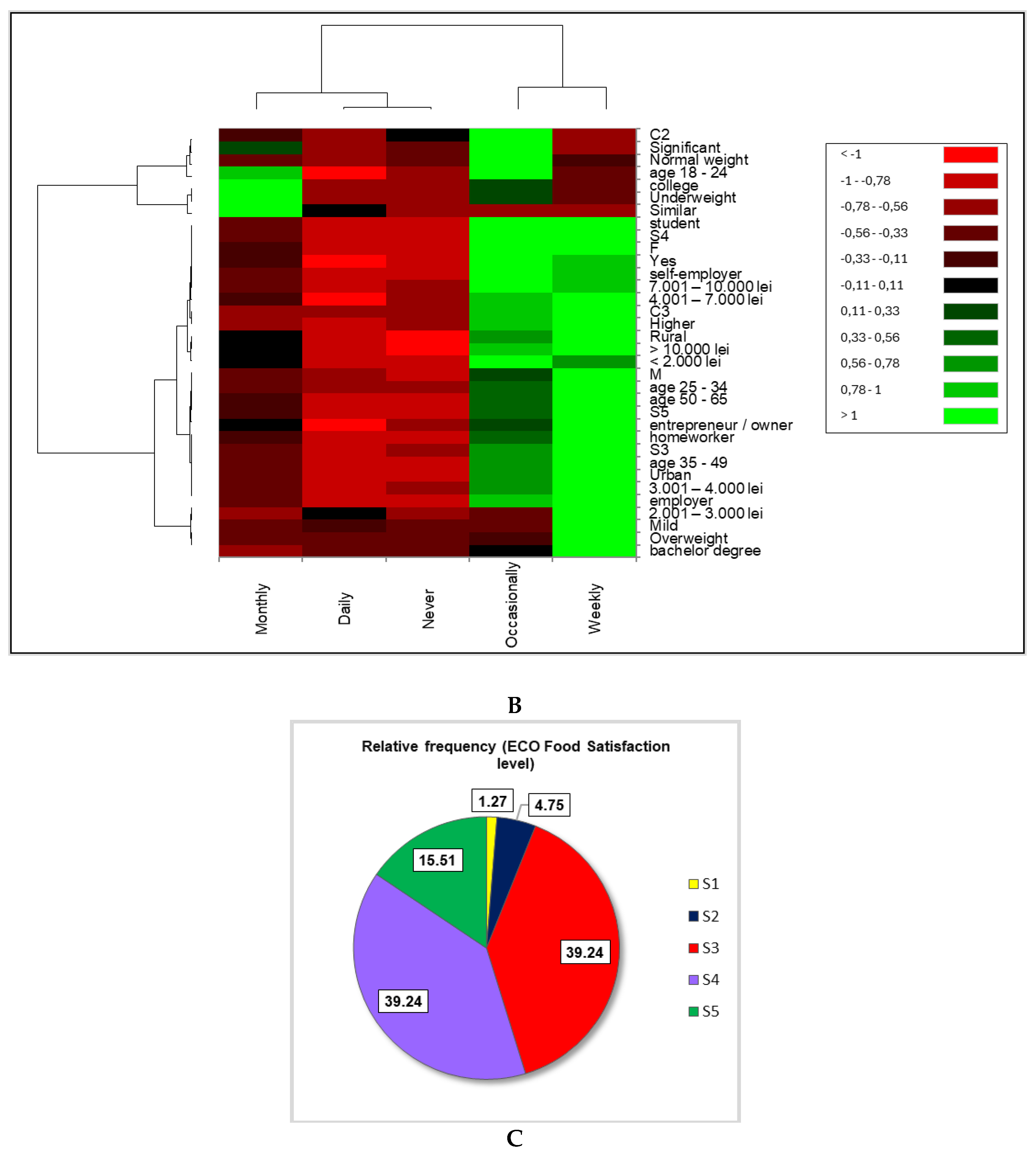

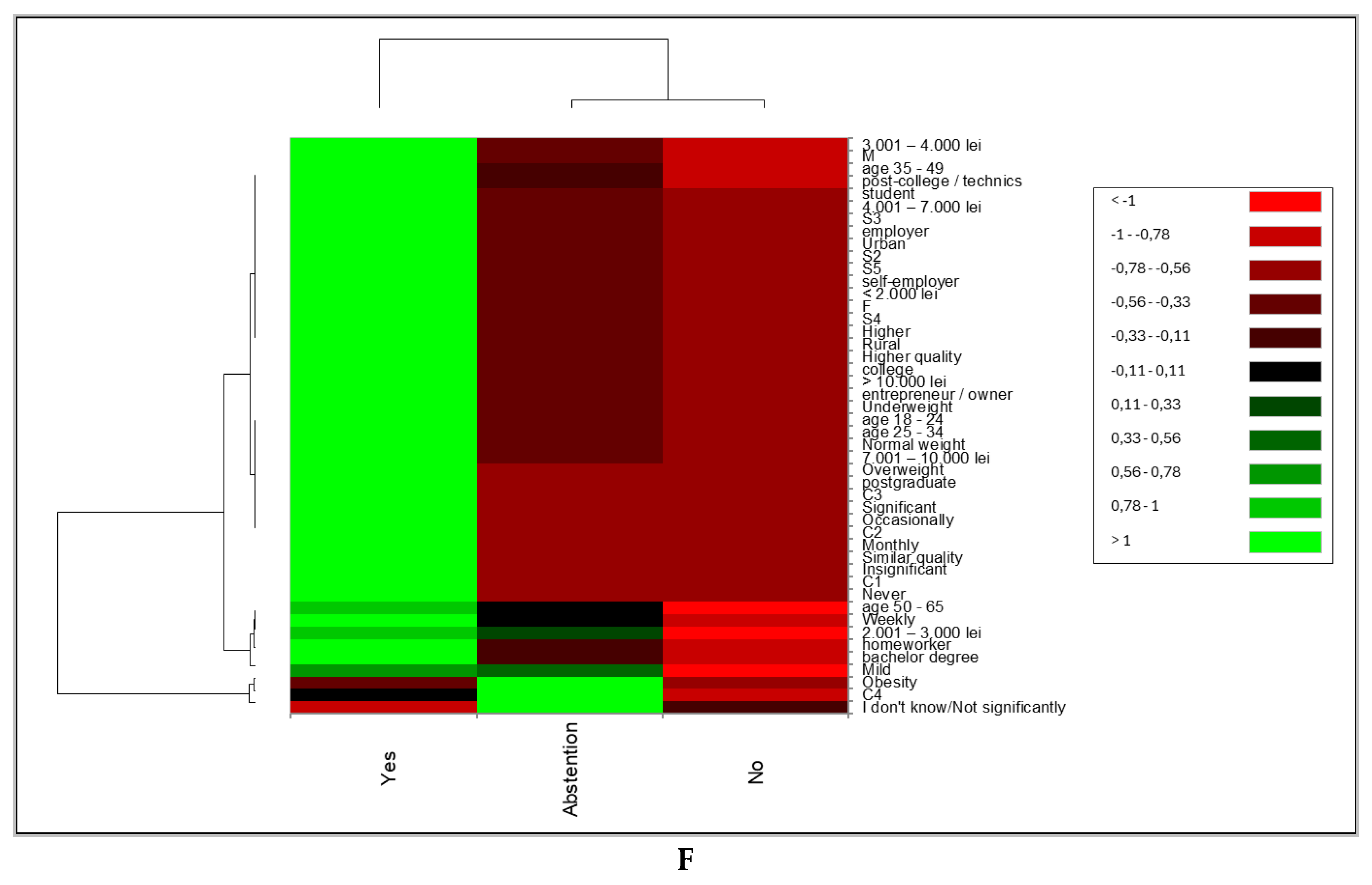

A sustainable healthy diet aims to assess human well-being in all life stages at the physical, mental, and social levels, protect environmental resources, and preserve bio-diversity. This work investi-gates the sociodemographic factors, knowledge, trust, and motivations involved in organic food acquisition behavior through a cross-sectional observational study using an online survey via the Google Forms platform, conducted from 01 March to 31 May 2024. The questionnaire was orga-nized into 3 main sections detailing the participants' sociodemographic profile, assessing their perception of organic food, and analyzing eco-food acquisition and consumption behavior. Our findings show that suitably informed people with high educational levels (academic and post-college) report significant satisfaction with organic food consumption (S4 and S5). There is also a considerable correlation between ages 25-65, moderate to high satisfaction (S3-S5), and "yes" for eco-food recommendations. Moderate to high satisfaction levels (S3-S5) are also associated with medium confidence in eco-food labels (C3) and moderate to high income. Our results show that monthly income and residence are not essential factors in higher price perception. Insignificant price variation perception correlated with C4 and weekly acquisition. Similar price perception substan-tially correlates with C5 and daily acquisition. Lower price perception strongly correlates with minimal confidence and monthly acquisition. Organic foods have evident benefits in obesity treatment and BMI diminution; however, obese respondents exhibited minimal satisfaction and opted for "abstention" from eco-food recommendations. The findings suggest that investing in public information, educational campaigns, and other strategies to support local organic food producers is essential for increasing interest in eco-food consumption. The present study could en-rich the current scientific database with data collected and a deep analysis of knowledge, percep-tion, attitude, trust, and motivation involved in Romanian consumer behavior for eco-food acqui-sition. Further exploratory studies will be conducted on older participants with different chronic diseases to investigate all aspects of organic food consumption.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

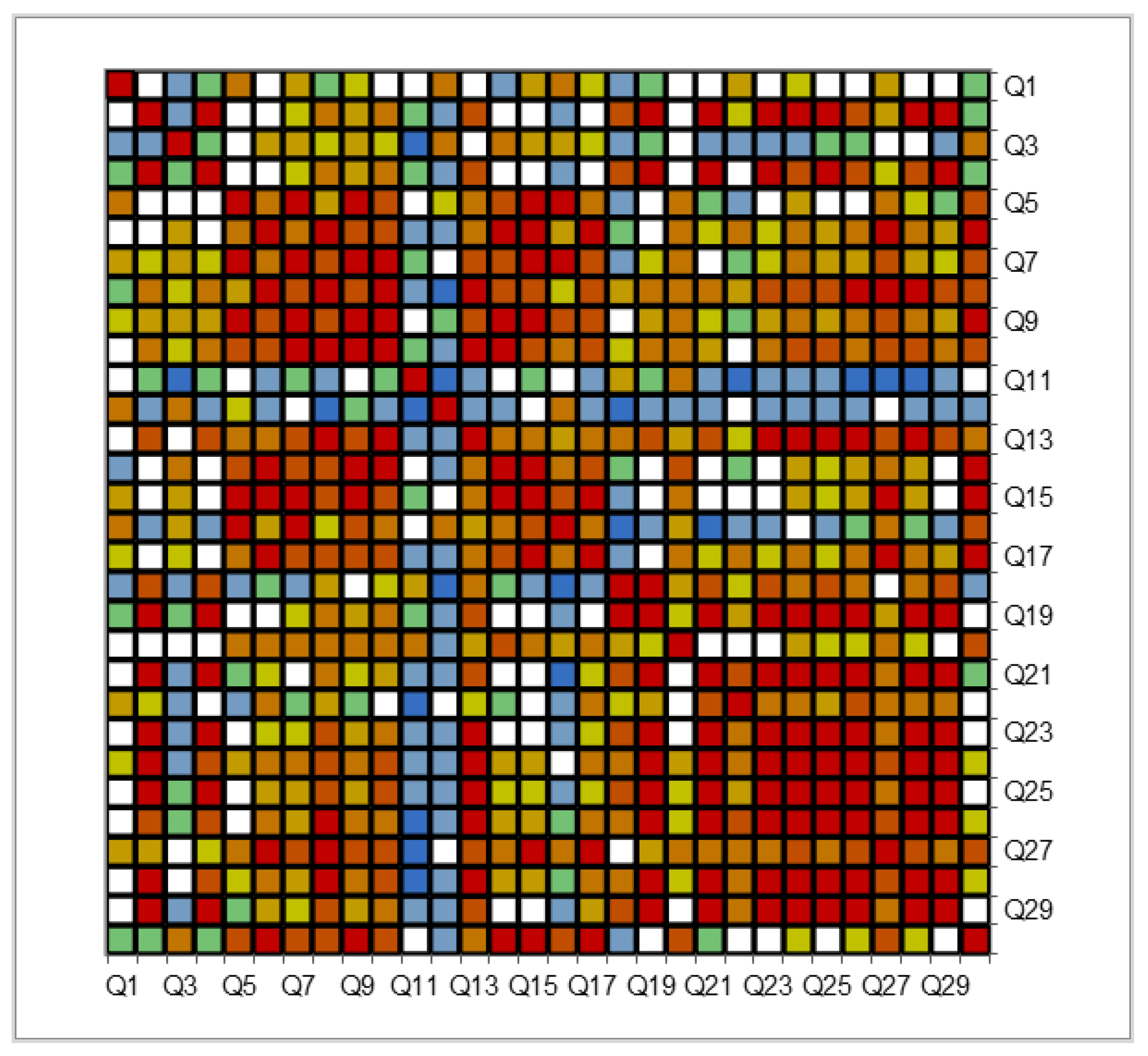

Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Sociodemographic Data of Participants

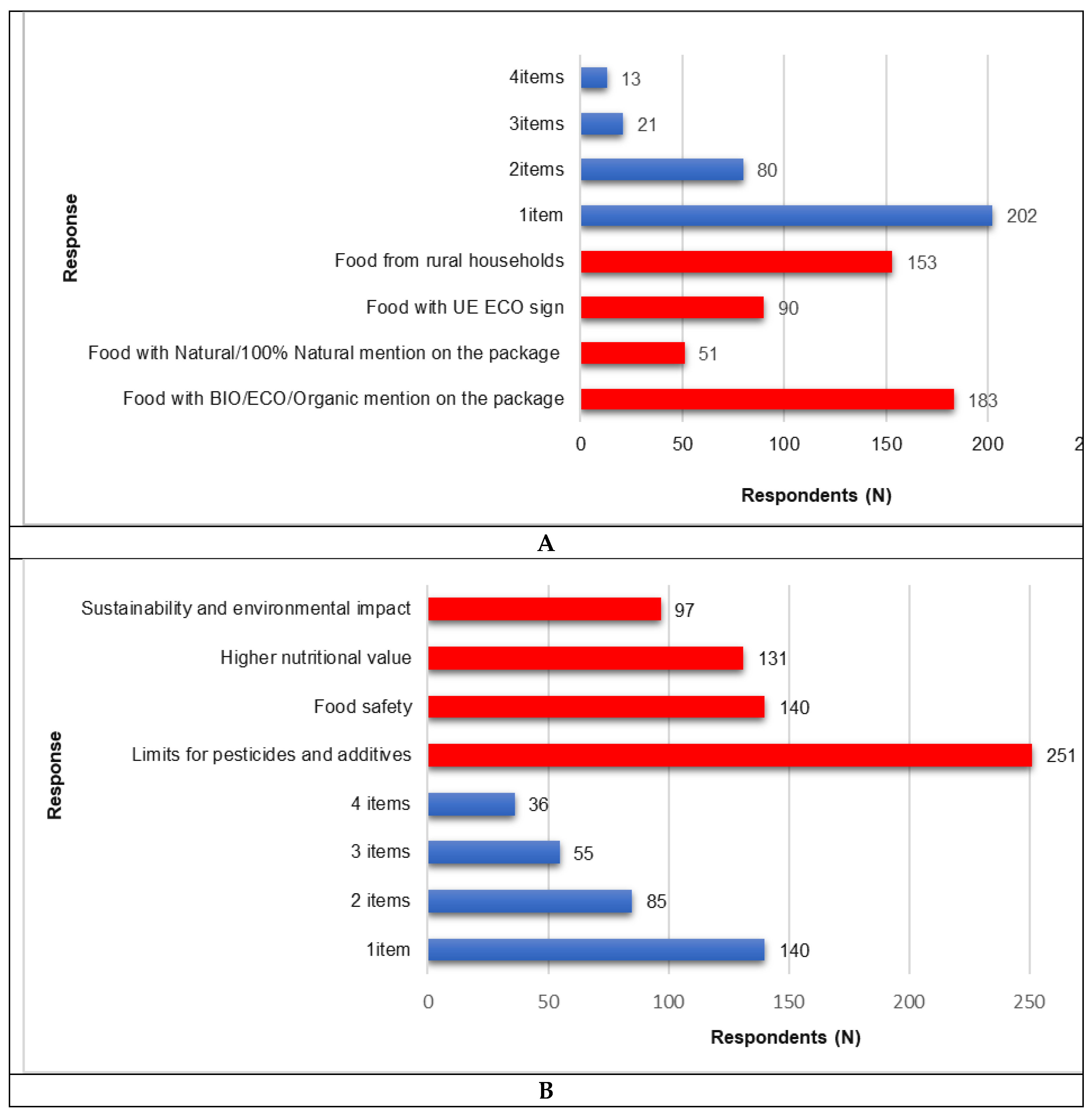

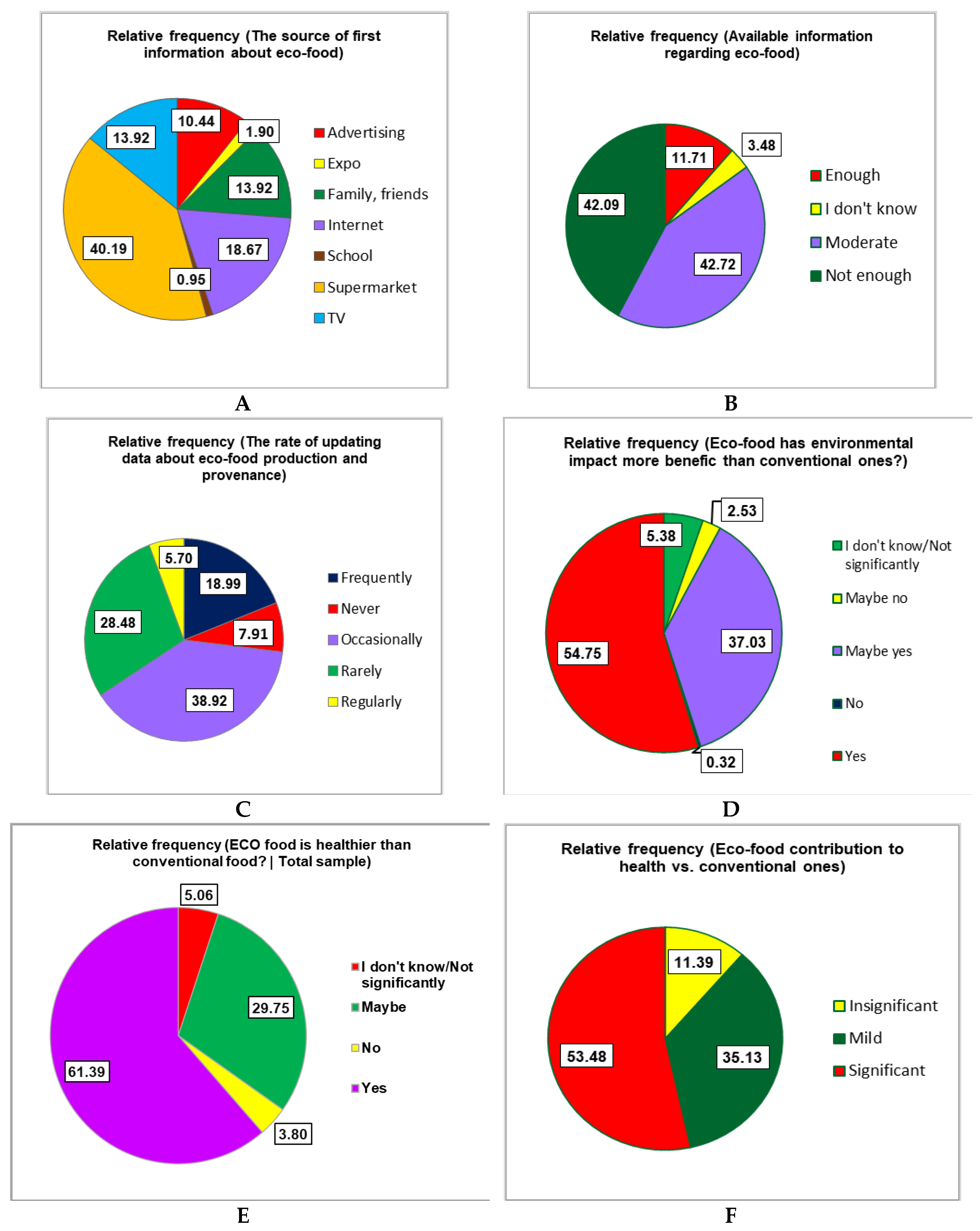

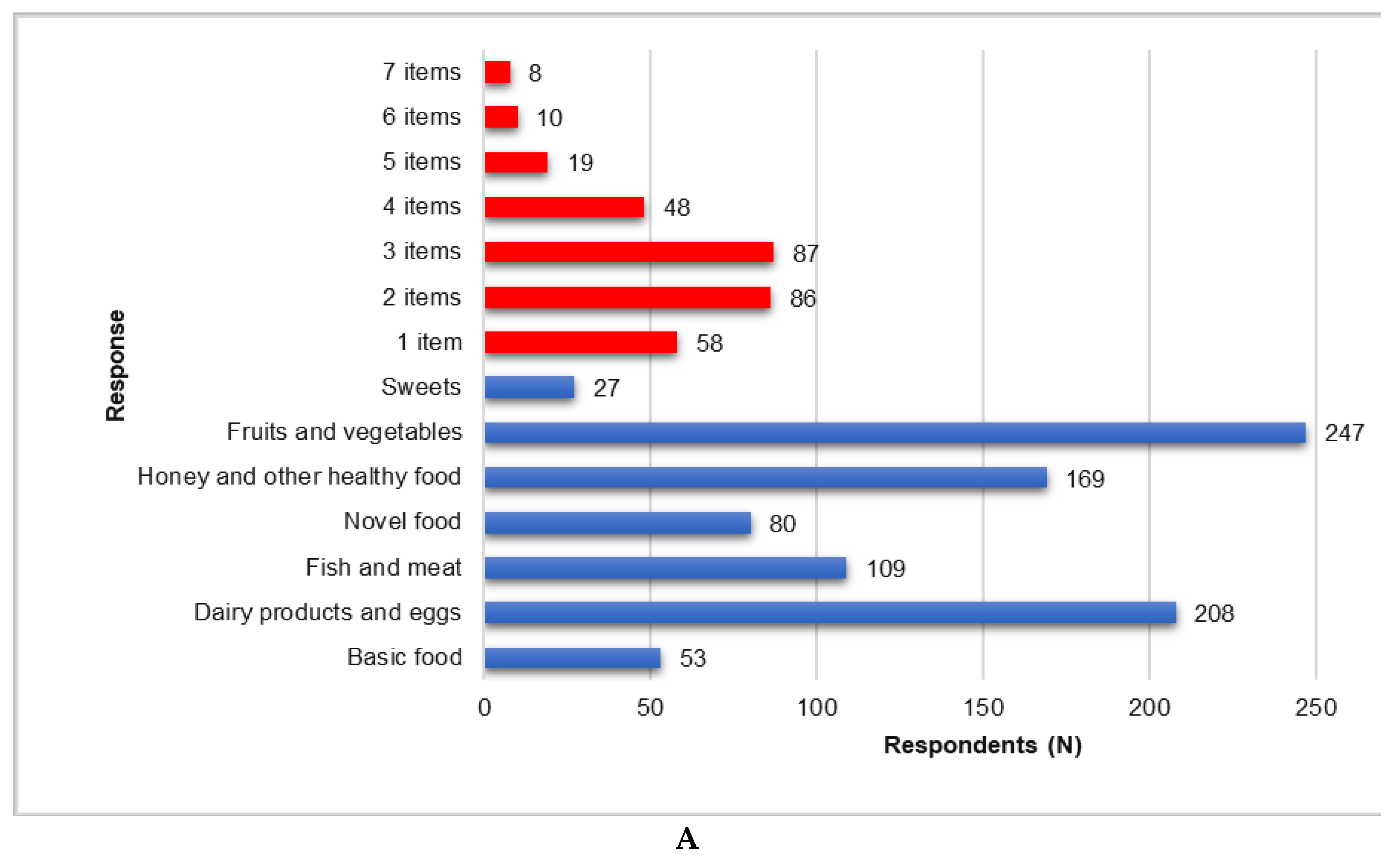

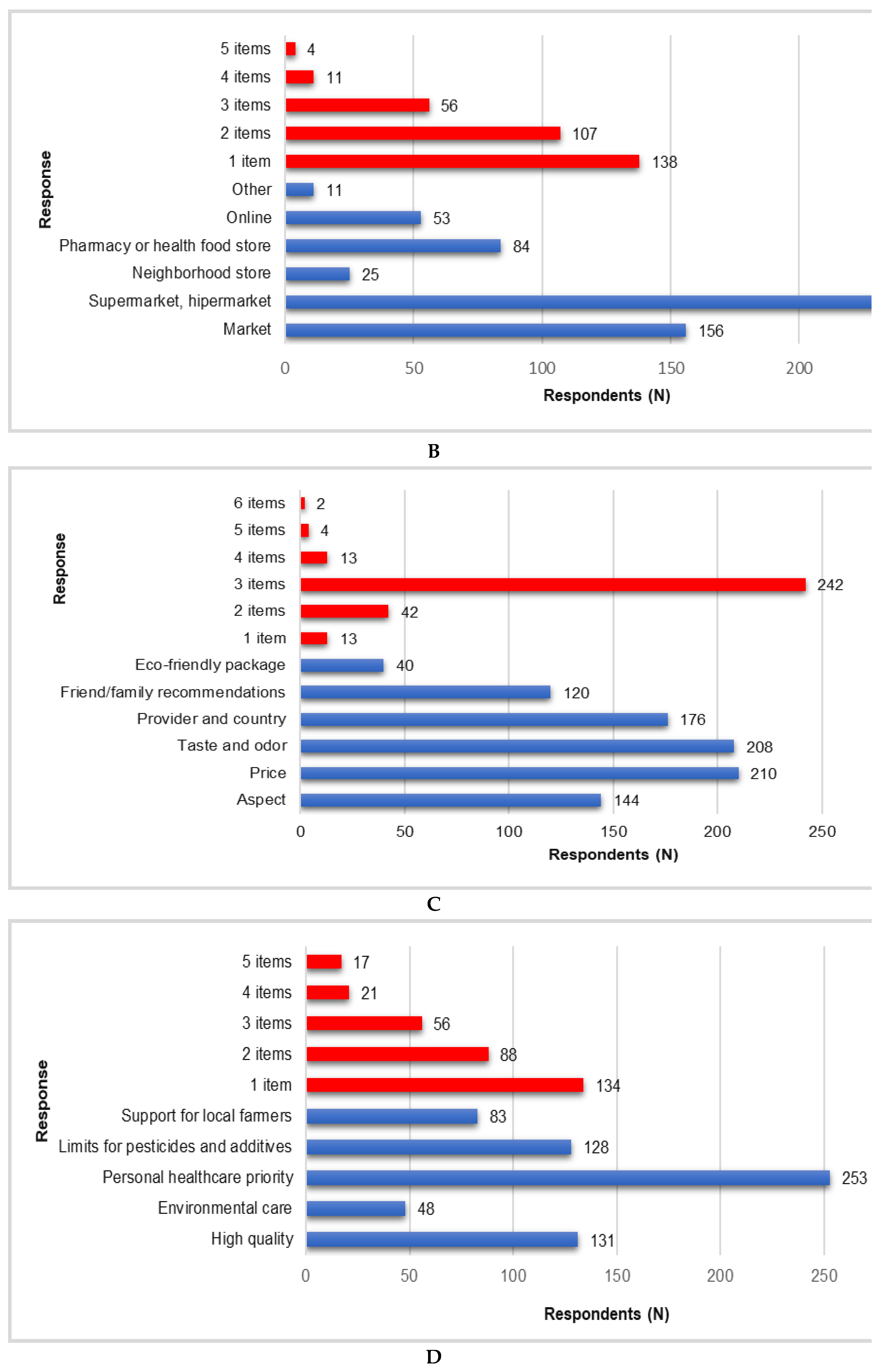

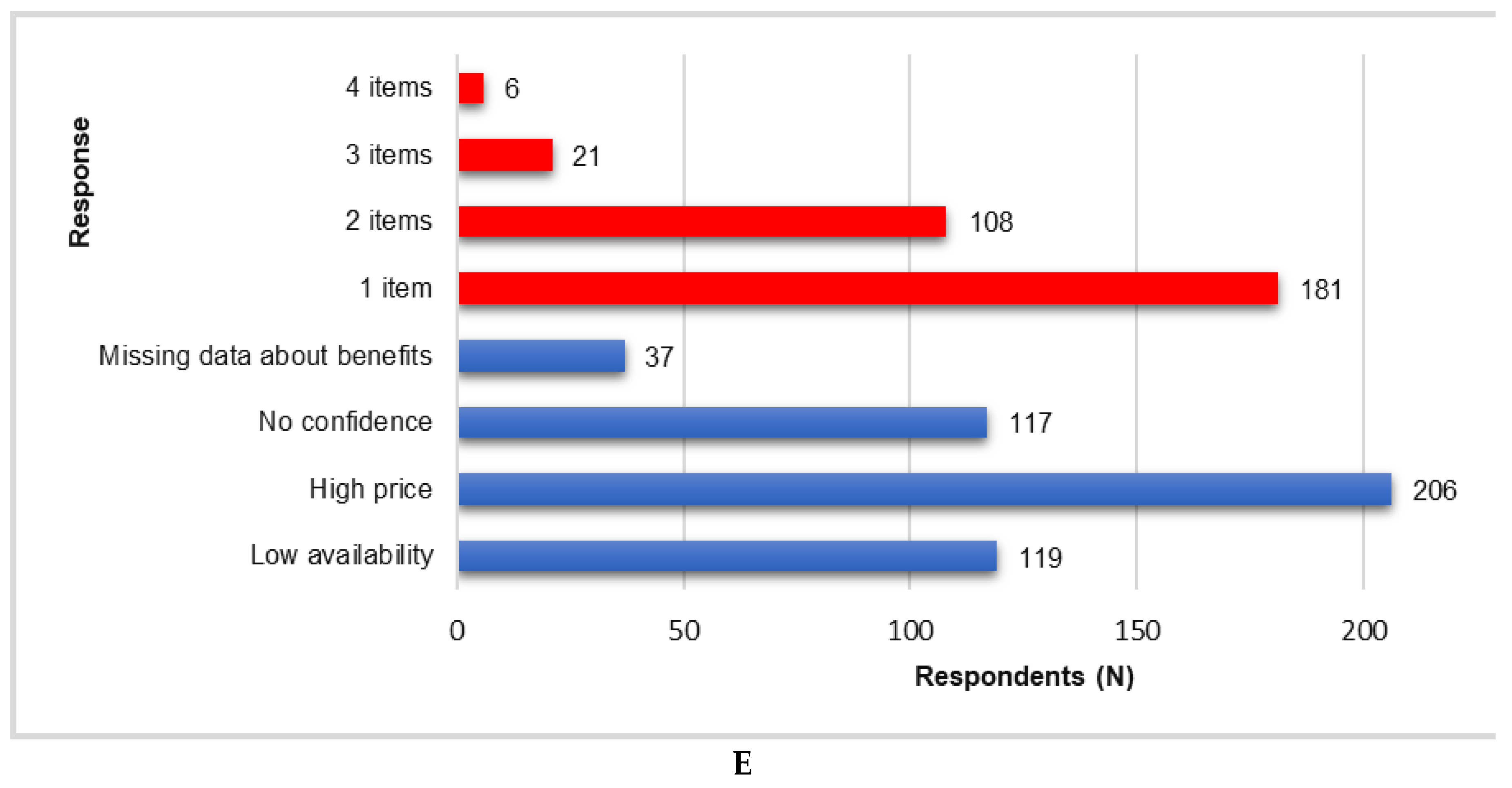

3.2. Eco-Food Concept Perception and Understanding

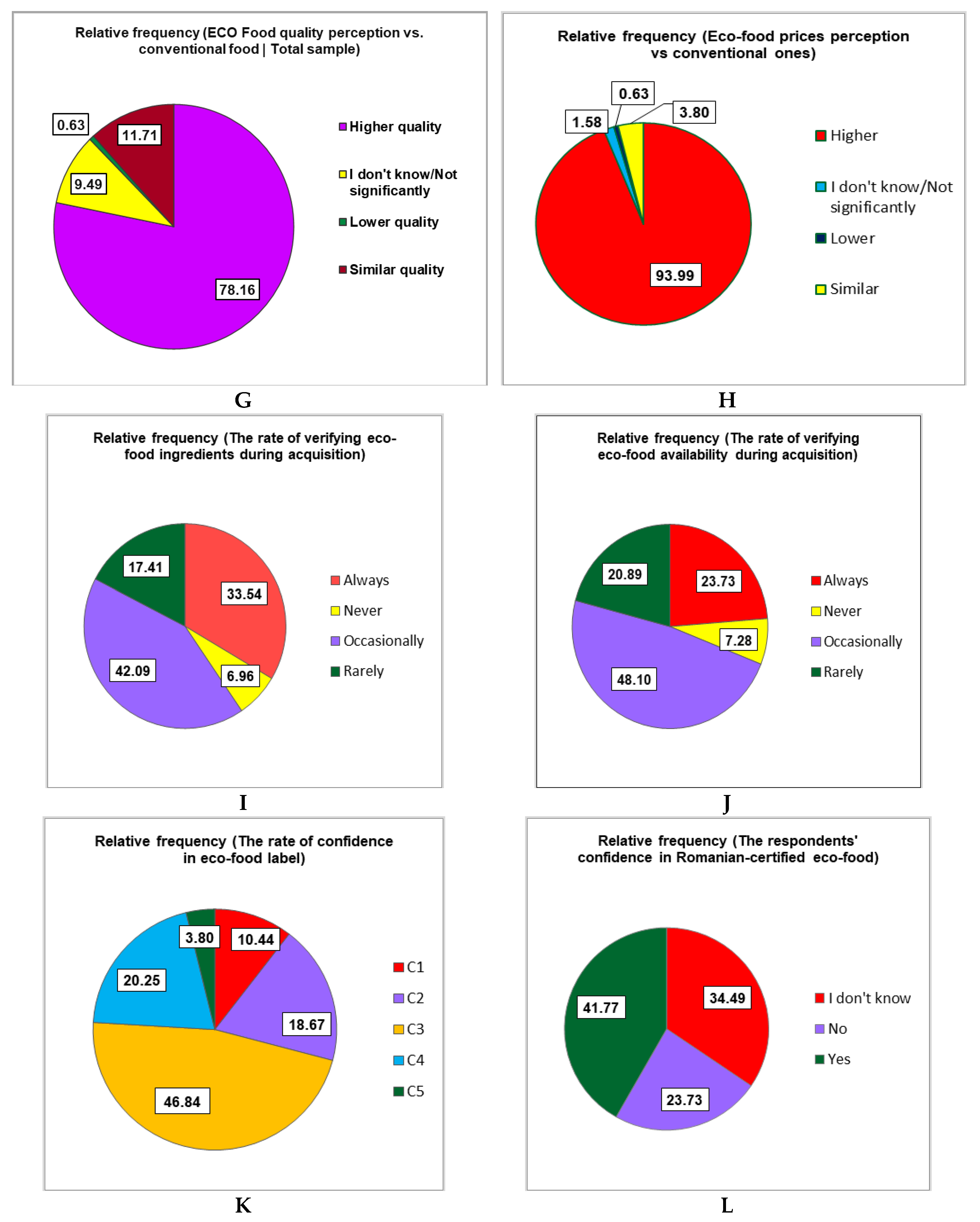

3.3. Eco-Food Purchasing Behavior

3.4. Sociodemographic Factors Differentiate the Consumers and Influence Perceptions and Motivations for Eco-Food Acquisition

4. Discussion

- ▪

- Investigating the level of knowledge and familiarity regarding eco-food;

- ▪

- Understanding the respondents’ general attitudes towards organic foods and the factors influencing these attitudes;

- ▪

- Exploring the motivations behind the decision to buy eco-food;

- ▪

- Analyzing the most important factors that determine whether consumers purchase organic food or not;

- ▪

- The level of satisfaction of the respondents towards the ecological products;

- ▪

- Correlation of these data with sociodemographics.

4.1. Eco-Food Concept Perception and Understanding

- ▪

- Organic foods have a lower risk of synthetic pesticide contamination;

- ▪

- Organic foods positively act on the environment and human health;

- ▪

- No differences were reported regarding heavy metals, mycotoxins, and susceptibility to microbial contamination;

- ▪

- Comparable safety and nutritional value.

4.2. Eco-Food Purchasing Behavior

4.3. Sociodemographic Factors Differentiate the Consumers and Influence Perceptions and Motivations for Eco-Food Acquisition

4.4. Limitations and Further Directions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Suresh Kashinath Ghatge Impact of Modern Lifestyle on Health. PriMera Scientific Surgical Research and Practice 2023, 16–19. [CrossRef]

- Negreş, S.; Chiriţǎ, C.; Moroşan, E.; Arsene, R.L. Experimental Pharmacological Model of Diabetes Induction with Aloxan in Rat. Farmacia 2013, 61, 313–322. [Google Scholar]

- Krokstad, S.; Ding, D.; Grunseit, A.C.; Sund, E.R.; Holmen, T.L.; Rangul, V.; Bauman, A. Multiple Lifestyle Behaviours and Mortality, Findings from a Large Population-Based Norwegian Cohort Study - The HUNT Study. BMC Public Health 2017, 17, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oster, H.; Chaves, I. Effects of Healthy Lifestyles on Chronic Diseases: Diet, Sleep and Exercise. Nutrients 2023, 15, 4627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moroșan, E.; Lupu, C.; Mititelu, M.; Musuc, A.; Rusu, A.; Răducan, I.; Karampelas, O.; Voinicu, I.; Neacșu, S.; Licu, M.; et al. Evaluation of the Nutritional Quality of Different Soybean and Pea Varieties: Their Use in Balanced Diets for Different Pathologies. Applied Sciences 2023, 13, 8724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jassim, R.A.; Mihele, D.; Dogaru, E. Study Regarding the Influence of Vitis Vinifera Fruit (Muscat of Hamburg Species) on Some Biochemical Parameters. Farmacia 2010, 58, 332–340. [Google Scholar]

- Moroșan, E.; Secăreanu, A.A.; Musuc, A.M.; Mititelu, M.; Ioniță, A.C.; Ozon, E.A.; Dărăban, A.M.; Karampelas, O. Advances on the Antioxidant Activity of a Phytocomplex Product Containing Berry Extracts from Romanian Spontaneous Flora. Processes 2022, 10, 646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moroșan, E.; Mititelu, M.; Drăgănescu, D.; Lupuliasa, D.; Ozon, E.A.; Karampelas, O.; Gîrd, C.E.; Aramă, C.; Hovaneț, M.V.; Musuc, A.M.; et al. Investigation into the Antioxidant Activity of Standardized Plant Extracts with Pharmaceutical Potential. Applied Sciences 2021, 11, 8685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hovaneţ, M.V.; Ancuceanu, R.V.; Dinu, M.; Oprea, E.; Budura, E.A.; Negreş, S.; Velescu, B.Ş.; Duţu, L.E.; Anghel, I.A.; Ancu, I.; et al. Toxicity and Anti-Inflammatory Activity of Ziziphus Jujuba Mill. Leaves. Farmacia 2016, 64, 802–808. [Google Scholar]

- Moroșan, E.; Secareanu, A.A.; Musuc, A.M.; Mititelu, M.; Ioniță, A.C.; Ozon, E.A.; Raducan, I.D.; Rusu, A.I.; Dărăban, A.M.; Karampelas, O. Comparative Quality Assessment of Five Bread Wheat and Five Barley Cultivars Grown in Romania. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2022, 19, 11114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Streba, L.; Popovici, V.; Mihai, A.; Mititelu, M.; Lupu, C.E.; Matei, M.; Vladu, I.M.; Iovănescu, M.L.; Cioboată, R.; Călărașu, C.; et al. Integrative Approach to Risk Factors in Simple Chronic Obstructive Airway Diseases of the Lung or Associated with Metabolic Syndrome—Analysis and Prediction. Nutrients 2024, 16, 1851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hovanet, M.V.; Dociu, N.; Dinu, M.; Ancuceanu, R.; Morosan, E.; Oprea, E. A Comparative Physico-Chemical Analysis of Acer Platanoides and Acer Pseudoplatanus Seed Oils. Revista de Chimie 2015, 66, 987–991. [Google Scholar]

- Alexandropoulou, I.; Goulis, D.G.; Merou, T.; Vassilakou, T.; Bogdanos, D.P.; Grammatikopoulou, M.G. Basics of Sustainable Diets and Tools for Assessing Dietary Sustainability: A Primer for Researchers and Policy Actors. Healthcare 2022, 10, 1668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, C.; Wang, D.; Liu, C.; Jiang, J.; Wang, X.; Chen, H.; Ju, X.; Zhang, X. What Is the Meaning of Health Literacy? A Systematic Review and Qualitative Synthesis. Fam Med Community Health 2020, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Platter, H.; Kaplow, K.; Baur, C. The Value of Community Health Literacy Assessments: Health Literacy in Maryland. Public Health Reports 2022, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, G.P.; Costa-Camilo, E.; Duarte, I. Advancing Health and Sustainability: A Holistic Approach to Food Production and Dietary Habits. Foods 2024, 13, 3829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, H.; Haccius, M. Analysis of Regulation (EU) 2018/848 on Organic Food: New Rules for Farming, Processing, and Organic Controls. European Food and Feed Law Review 2020, 15, available online at www.ec.europa.eu/agriculture/organic/home_ro accessed on 20 November 2024.

- Tittarelli, F. Organic Greenhouse Production: Towards an Agroecological Approach in the Framework of the New European Regulation—A Review. Agronomy 2020, 10, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bostan, I.; Onofrei, M.; Gavriluţă (Vatamanu), A.F.; Toderașcu, C.; Lazăr, C.M. An Integrated Approach to Current Trends in Organic Food in the EU. Foods 2019, 8, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green Report available online at https://green-report.ro/eurostat-doar-29-din-suprafata-agricola-a-romaniei-reprezinta-culturi-ecolo accessed on 20 November 2024.

- Agricultura ecologica available online at https://www.srac.ro/ro/agricultura-ecologica accessed on 10 November 2024.

- Agricultura ecologica available online at https://www.madr.ro/agricultura-ecologica.html accessed on 20 November 2024.

- Glogovețan, A.-I.; Pocol, C.B. The Role of Promoting Agricultural and Food Products Certified with European Union Quality Schemes. Foods 2024, 13, 970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rey, R. ’ Mountain Product’, of High- Biological Quality. Meadows’ Poliflora, Organic Fertilizer and a Sustainable Mountain Economy. Procedia Economics and Finance 2014, 8, 622–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statistica available online at https://www.statista.com/outlook/cmo/food/eu-27#volume accessed on 20 november 2024.

- Eurostat available online at https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/org_cropar/default/table?lang=en, accessed on 20 November 2024.

- Certified organic producers in Romania available at https://www.agriculturaecologica.ro/ accessed on 20 November 2024.

- Online Map of Romanian Organic Producers available online at https://www.google.com/maps/d/u/0/viewer?mid=1vjnzHRgaJTwOlmOLmb1fHV-YxqKIjZc&ll=45.86943922040263%2C24.65654153816237&z=7 accessed on 20 November 2024.

- Neagu, R.; Popovici, V.; Ionescu, L.-E.; Ordeanu, V.; Biță, A.; Popescu, D.M.; Ozon, E.A.; Gîrd, C.E. Phytochemical Screening and Antibacterial Activity of Commercially Available Essential Oils Combinations with Conventional Antibiotics against Gram-Positive and Gram-Negative Bacteria. Antibiotics 2024, 13, 478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mititelu, M.; Popovici, V.; Neacșu, S.M.; Musuc, A.M.; Busnatu, Ștefan, S.; Oprea, E.; Boroghină, S.C.; Mihai, A.; Streba, C.T.; Lupuliasa, D.; et al. Assessment of Dietary and Lifestyle Quality among the Romanian Population in the Post-Pandemic Period. Healthcare 2024, 12, 1006. [CrossRef]

- Moroșan, E.; Dărăban, A.; Popovici, V.; Rusu, A.; Ilie, E.I.; Licu, M.; Karampelas, O.; Lupuliasa, D.; Ozon, E.A.; Maravela, V.M.; et al. Sociodemographic Factors, Behaviors, Motivations, and Attitudes in Food Waste Management of Romanian Households. Nutrients 2024, 16, 2738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montgomery, D.R.; Biklé, A. Soil Health and Nutrient Density: Beyond Organic vs. Conventional Farming. Front Sustain Food Syst 2021, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostandie, N.; Giffard, B.; Bonnard, O.; Joubard, B.; Richart-Cervera, S.; Thiéry, D.; Rusch, A. Multi-Community Effects of Organic and Conventional Farming Practices in Vineyards. Sci Rep 2021, 11, 11979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, S.; Das, A.; Kasala, K.; Ridoutt, B.; Patan, E.K.; Bogard, J.; Ravula, P.; Pramanik, S.; Lim-Camacho, L.; Swamikannu, N. Assessing the Rural Food Environment for Advancing Sustainable Healthy Diets: Insights from India. J Agric Food Res 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jallow, M.; Awadh, D.; Albaho, M.; Devi, V.; Thomas, B. Pesticide Knowledge and Safety Practices among Farm Workers in Kuwait: Results of a Survey. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2017, 14, 340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmood Ali, I. The Harmful Effects of Pesticides on the Environment and Human Health: A Review. Diyala Agricultural Sciences Journal 2023, 15, 114–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehghani, M.H.; Ahmadi, S.; Ghosh, S.; Khan, M.S.; Othmani, A.; Khanday, W.A.; Gökkuş, Ö.; Osagie, C.; Ahmaruzzaman, Md.; Mishra, S.R.; et al. Sustainable Remediation Technologies for Removal of Pesticides as Organic Micro-Pollutants from Water Environments: A Review. Applied Surface Science Advances 2024, 19, 100558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IFOAM Organics Europe PESTICIDES IN CONVENTIONAL AND ORGANIC FARMING, available online at https://www.organicseurope.bio/events/online-press-conference-conventional-and-organic-pesticides-compared-23-february/ accessed on 20 November 2024.

- Muhammad, S.; Fathelrahman, E.; Tasbih Ullah, R. The Significance of Consumer’s Awareness about Organic Food Products in the United Arab Emirates. Sustainability 2016, 8, 833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudziak, A.; Kocira, A. Preference-Based Determinants of Consumer Choice on the Polish Organic Food Market. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2022, 19, 10895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; McCarthy, B.; Kapetanaki, A.B. To Be Ethical or to Be Good? The Impact of ’Good Provider’ and Moral Norms on Food Waste Decisions in Two Countries. Global Environmental Change 2021, 69, 102300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilverda, F.; Kuttschreuter, M.; Giebels, E. The Effect of Online Social Proof Regarding Organic Food: Comments and Likes on Facebook. Front Commun (Lausanne) 2018, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masih, J.; Deshpande, M.; Singh, H.; Deutsch, J. Study of Public Sentiment Using Social Media for Organic Foods in Pre-Covid and Post-Covid Times Worldwide. In Proceedings of the Lecture Notes in Networks and Systems; 2023; Vol. 557.

- Leifeld, J. How Sustainable Is Organic Farming? Agric Ecosyst Environ 2012, 150, 121–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith-Spangler, C.; Brandeau, M.L.; Hunter, G.E.; Bavinger, J.C.; Pearson, M.; Eschbach, P.J.; Sundaram, V.; Liu, H.; Schirmer, P.; Stave, C.; et al. Are Organic Foods Safer or Healthier Than Conventional Alternatives? Ann Intern Med 2012, 157, 348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dziuba, S.; Cierniak-Emerych, A.; Klímová, B.; Poulová, P.; Napora, P.; Szromba, S. Organic Foods in Diets of Patients with Alzheimer’s Disease. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gumber, G.; Rana, J. Who Buys Organic Food? Understanding Different Types of Consumers. Cogent Business & Management 2021, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goetzke, B.; Nitzko, S.; Spiller, A. Consumption of Organic and Functional Food. A Matter of Well-Being and Health? Appetite 2014, 77, 96–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahl, J.; Załęcka, A.; Ploeger, A.; Bügel, S.; Huber, M. Functional Food and Organic Food Are Competing Rather than Supporting Concepts in Europe. Agriculture (Switzerland) 2012, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Migliore, G.; Rizzo, G.; Bonanno, A.; Dudinskaya, E.C.; Tóth, J.; Schifani, G. Functional Food Characteristics in Organic Food Products—the Perspectives of Italian Consumers on Organic Eggs Enriched with Omega-3 Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids. Organic Agriculture 2022, 12, 149–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mie, A.; Andersen, H.R.; Gunnarsson, S.; Kahl, J.; Kesse-Guyot, E.; Rembiałkowska, E.; Quaglio, G.; Grandjean, P. Human Health Implications of Organic Food and Organic Agriculture: A Comprehensive Review. Environmental Health 2017, 16, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çakmakçı, S.; Çakmakçı, R. Quality and Nutritional Parameters of Food in Agri-Food Production Systems. Foods 2023, 12, 351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, R.-D. Predicting Intentions to Purchase Organic Food: The Moderating Effects of Organic Food Prices. British Food Journal 2016, 118, 183–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organic food is more expensive, available at https://navitasorganics.com/blogs/navitaslife/5-reasons-organic-food-is-more-expensive accessed on 20 November 2024.

- Aurelia MORNA.; Monica BRATA.; Paula TIRPE.; Florina FORA.; Ioana CHEREJI.; Anda MILIN.; Vasilica BACTER ANALYSIS OF THE FACTORS AND BARRIERS INFLUENCING THE CONSUMPTION OF ORGANIC PRODUCTS. CASE OF BIHOR COUNTY, ROMANIA. Scientific Papers Series Management, Economic Engineering in Agriculture and Rural Development 23, 2023.

- Giucă, A.D.; Gaidargi Chelaru, M.; Kuzman, B. The Market of Organic Agri-Food Products in Romania. In Geopolitical perspectives and technological challenges for sustainable growth in the 21st century; 2023.

- Popa, I.D.; Dabija, D.-C. Developing the Romanian Organic Market: A Producer’s Perspective. Sustainability 2019, 11, 467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NASPETTI, S.; ZANOLI, R. DO CONSUMERS CARE ABOUT WHERE THEY BUY ORGANIC PRODUCTS? A MEANS-END STUDY WITH EVIDENCE FROM ITALIAN DATA. In Marketing Trends For Organic Food In The 21st Century; 2004; pp. 239–255.

- Liang, S.; Yuan, X.; Han, X.; Han, C.; Liu, Z.; Liang, M. Is Seeing Always Good? The Influence of Organic Food Packaging Transparency on Consumers’ Purchase Intentions. Int J Food Sci Technol 2023, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barański, M.; Rempelos, L.; Iversen, P.O.; Leifert, C. Effects of Organic Food Consumption on Human Health; the Jury Is Still Out! Food Nutr Res 2017, 61, 1287333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Limbu, Y.B.; McKinley, C.; Ganesan, P.; Wang, T.; Zhang, J. Examining How and When Knowledge and Motivation Contribute to Organic Food Purchase Intention among Individuals with Chronic Diseases: Testing a Moderated Mediation Model. Sustainability 2023, 15, 14584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poulia, K.-A.; Bakaloudi, D.R.; Alevizou, M.; Papakonstantinou, E.; Zampelas, A.; Chourdakis, M. Impact of Organic Foods on Health and Chronic Diseases: A Systematic Review of the Evidence. Clin Nutr ESPEN 2023, 58, 506–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernabéu, R.; Brugarolas, M.; Martínez-Carrasco, L.; Nieto-Villegas, R.; Rabadán, A. The Price of Organic Foods as a Limiting Factor of the European Green Deal: The Case of Tomatoes in Spain. Sustainability 2023, 15, 3238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smoluk-Sikorska, J.; Śmiglak-Krajewska, M.; Rojík, S.; Fulnečková, P.R. Prices of Organic Food—The Gap between Willingness to Pay and Price Premiums in the Organic Food Market in Poland. Agriculture 2023, 14, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, S.M.E.; Mele, M.A.; Lee, Y.T.; Islam, M.Z. Consumer Preference, Quality, and Safety of Organic and Conventional Fresh Fruits, Vegetables, and Cereals. Foods 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuttavuthisit, K.; Thøgersen, J. The Importance of Consumer Trust for the Emergence of a Market for Green Products: The Case of Organic Food. Journal of Business Ethics 2017, 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kun, A.I.; Kiss, M. On the Mechanics of the Organic Label Effect: How Does Organic Labeling Change Consumer Evaluation of Food Products? Sustainability 2021, 13, 1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tapas, P.; Desai, K. Study of Consumer Perception about Organic Food Labels. International Review of Business and Economics 2020, 4, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuchler, F.; Bowman, M.; Sweitzer, M.; Greene, C. Evidence from Retail Food Markets That Consumers Are Confused by Natural and Organic Food Labels. J Consum Policy (Dordr) 2020, 43, 379–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M. The Effects of Organic Certification on Shoppers’ Purchase Intention Formation in Taiwan: A Multi-Group Analysis of Structural Invariance. Sustainability 2021, 14, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, S.A.H.; Priyono, A.; Ming, C.H. An Exploratory Study of Integrated Management System on Food Safety and Organic Certifications. International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences 2020, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, J. de S.C.; de Faria, C.P.; de São José, J.F.B. Organic Food Consumers and Producers: Understanding Their Profiles, Perceptions, and Practices. Heliyon 2024, 10, e31385. [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharjee, S.; Reddy, K.P.; Sharma, V. Covid Stimulating Organic Food Consumption: Exploring Factors of Consumer Buying Behaviour. Indian Journal of Ecology 2021, 48. [Google Scholar]

- Bhagavathula, A.S.; Vidyasagar, K.; Khubchandani, J. Organic Food Consumption and Risk of Obesity: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Healthcare 2022, 10, 231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gosling, C.J.; Goncalves, A.; Ehrminger, M.; Valliant, R. Association of Organic Food Consumption with Obesity in a Nationally Representative Sample. British Journal of Nutrition 2021, 125, 703–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter | Total | F | M | p | ||||

| N | % | N | % | N | % | |||

| Sex | 316.00 | 100.00 | 199.00 | 62.97 | 117.00 | 37.03 | < 0.05 | |

| Residence | Rural | 61.00 | 19.39 | 41.00 | 20.60 | 20.00 | 17.09 | |

| Urban | 255.00 | 80.70 | 158.00 | 79.40 | 97.00 | 82.91 | ||

| Age | age 19 - 24 | 32.00 | 10.13 | 24.00 | 12.06 | 8.00 | 6.84 | <0.05 |

| age 25 - 34 | 110.00 | 34.81 | 77.00 | 38.69 | 33.00 | 28.21 | ||

| age 35 - 49 | 134.00 | 42.41 | 79.00 | 39.70 | 55.00 | 47.01 | ||

| age 50 - 65 | 32.00 | 10.13 | 13.00 | 6.53 | 19.00 | 16.24 | ||

| age = 18 | 1.00 | 0.32 | 1.00 | 0.50 | 0.00 | 0.00 | ||

| age > 65 | 7.00 | 2.22 | 5.00 | 2.51 | 2.00 | 1.71 | ||

| Study level | bachelor degree | 152.00 | 48.10 | 90.00 | 45.23 | 62.00 | 52.99 | <0.05 |

| college | 40.00 | 12.66 | 26.00 | 13.07 | 14.00 | 11.97 | ||

| high school | 2.00 | 0.63 | 2.00 | 1.01 | 0.00 | 0.00 | ||

| mild | 1.00 | 0.32 | 1.00 | 0.50 | 0.00 | 0.00 | ||

| post-college / technics | 17.00 | 5.38 | 12.00 | 6.03 | 5.00 | 4.27 | ||

| postgraduate | 104.00 | 32.91 | 68.00 | 34.17 | 36.00 | 30.77 | ||

| Occupation | employer | 195.00 | 61.71 | 123.00 | 61.81 | 72.00 | 61.54 | <0.05 |

| entrepreneur / owner | 47.00 | 14.87 | 31.00 | 15.58 | 16.00 | 13.68 | ||

| homeworker | 26.00 | 8.23 | 14.00 | 7.04 | 12.00 | 10.26 | ||

| pensioner | 8.00 | 2.53 | 6.00 | 3.02 | 2.00 | 1.71 | ||

| self-employer | 16.00 | 5.06 | 10.00 | 5.03 | 6.00 | 5.13 | ||

| student | 20.00 | 6.33 | 13.00 | 6.53 | 7.00 | 5.98 | ||

| unemployed | 4.00 | 1.27 | 2.00 | 1.01 | 2.00 | 1.71 | ||

| Incomes | 2001 – 3000 lei | 47.00 | 14.87 | 27.00 | 13.57 | 20.00 | 17.09 | <0.05 |

| 3001 – 4000 lei | 41.00 | 12.97 | 21.00 | 10.55 | 20.00 | 17.09 | ||

| 4001 – 7000 lei | 86.00 | 27.22 | 61.00 | 30.65 | 25.00 | 21.37 | ||

| 7001 – 10000 lei | 41.00 | 12.97 | 27.00 | 13.57 | 14.00 | 11.97 | ||

| < 2.000 lei | 24.00 | 7.59 | 15.00 | 7.54 | 9.00 | 7.69 | ||

| > 10000 lei | 77.00 | 24.37 | 48.00 | 24.12 | 29.00 | 24.79 | ||

| BMI | Normal weight | 134.00 | 42.41 | 92.00 | 46.23 | 42.00 | 35.90 | <0.05 |

| Obesity | 45.00 | 14.24 | 16.00 | 8.04 | 29.00 | 24.79 | ||

| Overweight | 92.00 | 29.11 | 60.00 | 30.15 | 32.00 | 27.35 | ||

| Underweight | 45.00 | 14.24 | 31.00 | 15.58 | 14.00 | 11.97 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).