Submitted:

04 February 2025

Posted:

05 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background

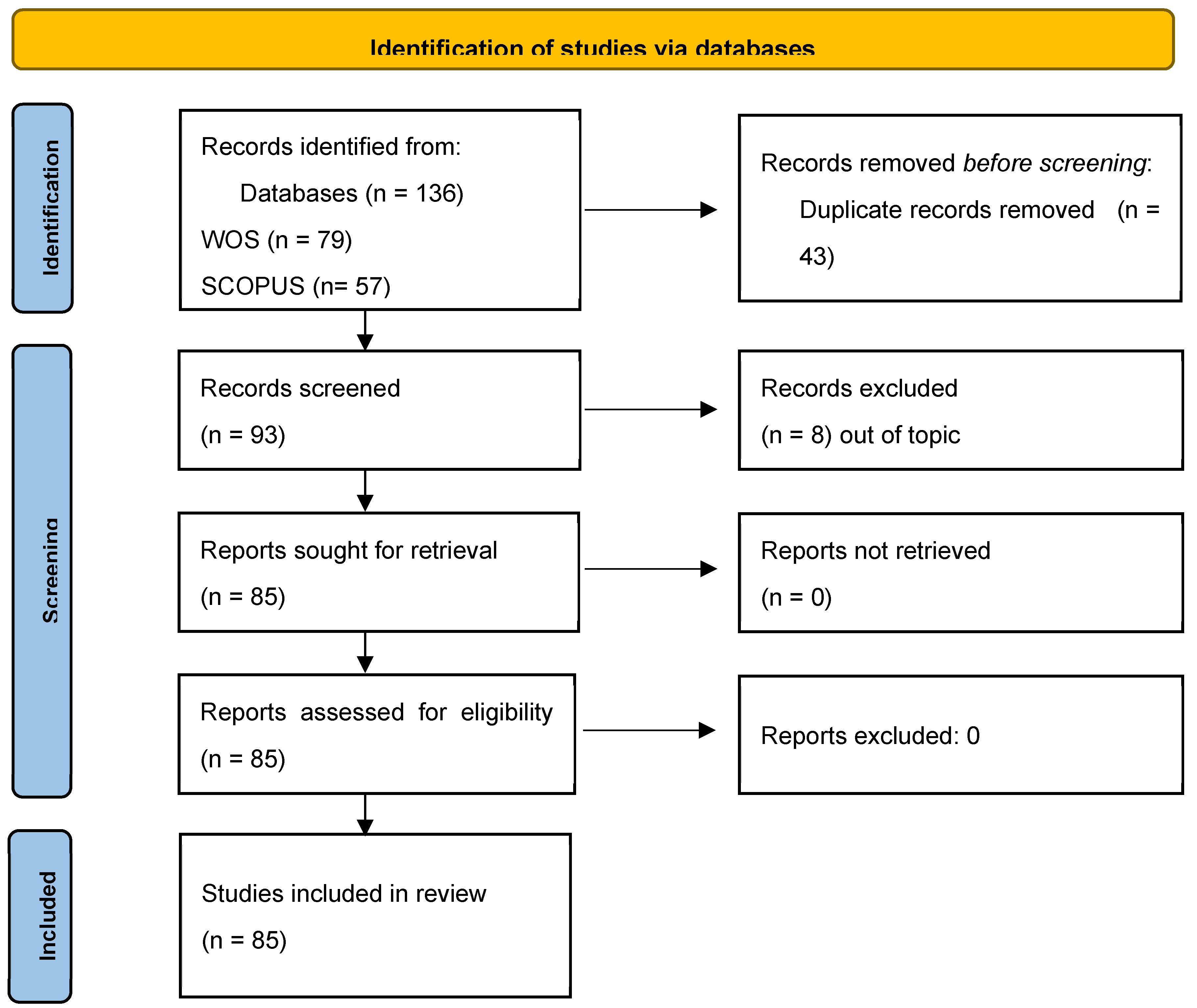

3. Methodology

- 1.

-

Literature Organization in the Zotero Collection

- Motivations (n=26): Consumer drivers and incentives.

- Barriers (n=36): Obstacles and limitations.

- Technology (n=15): Digital solutions and innovations.

- Corporate Initiatives (n=8): business strategies and programs.

- 2.

-

Adobe AI and Python-based Analysis Pipeline

- 1.

- Data extraction via Zotero API.

- 2.

- Automated text and pattern analysis.

- 3.

- Statistical trends and relationship analyses.

- 4.

- Generation of visual representations.

- 3.

-

Results, Visualization and Integration

- Thematic mapping.

- Temporal trend visualization.

- Comparative analysis across collections.

- Cross-theme pattern identification.

4. Results

4.1. Motivation in Sustainable Food Consumption

4.1.1. Recurring and Co-Occurring Categories of Motivation in Sustainable Food Consumption

4.1.2. Temporal Analysis of the Evolutions of Various Motivations

4.1.3. An in-Depth Examination of Drivers Behind Sustainable Food Consumption

4.2. Barriers in Sustainable Food Consumption

4.2.1. Recurring Categories of Barriers in Sustainable Food Consumption

4.2.2. Temporal Analysis of the Evolutions of Various Barriers

4.2.3. In-Depth Analysis of Barriers to Sustainable Food Consumption

4.3. Technologies in Sustainable Food Consumption

4.3.1. Recurring Themes and Categories of Technologies in Sustainable Food Consumption

4.3.2. Temporal Evolution of Technology Categories in Sustainable Consumption

4.3.3. In-Depth Analysis of Sustainable Food Consumption Technologies

4.4. Corporative Initiatives in Sustainable Food Consumption

4.4.1. Recurring Themes and Categories of Corporate Initiatives in Sustainable Food Consumption

4.4.2. Temporal Evolution of Corporate Initiatives Categories in Sustainable Consumption

4.4.3. In-Depth Analysis of Sustainable Food Corporate Initiatives

5. Discussion

- Subsidize sustainable food options to make them affordable.

- Expand accessibility by ensuring mainstream market availability.

- Enforce transparency in food labeling to prevent green washing.

- Leverage technology to empower informed consumer choices.

- Hold corporations accountable through global regulatory frameworks.

6. Contributions, Limits of the Study and Recommendations

6.1. Contributions of the Study

- Longitudinal impact of interventions to track behavioral shifts over time.

- The role of digital solutions and AI in overcoming awareness and accessibility barriers.

- Cultural adaptation of sustainability strategies to ensure their effectiveness across diverse populations.

- Role of AI and automation in driving corporate sustainability.

- How can digital solutions enhance consumer engagement in sustainability?

- Longitudinal Impact of Corporate Policies on Consumer Behavior.

6.2. Methodological Limitations of the Analysis

6.3. Future Research Direction and Recommandations

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Aguirre Sánchez, L.; Roa-Díaz, Z.M.; Gamba, M.; Grisotto, G.; Moreno Londoño, A.M.; Mantilla-Uribe, B.P.; Rincón Méndez, A.Y.; Ballesteros, M.; Kopp-Heim, D.; Minder, B.; Suggs, L.S.; Franco, O.H. What Influences the Sustainable Food Consumption Behaviours of University Students? A Systematic Review. Int. J. Public Health 2021, 66. https://doi.org/10.3389/ijph.2021.1604149. [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. https://doi.org/10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-T. [CrossRef]

- Amiri, B.; Jafarian, A.; Abdi, Z. Nudging towards sustainability: A comprehensive review of behavioral approaches to eco-friendly choice. Discov. Sustain. 2024, 5, 444. https://doi.org/10.1007/s43621-024-00618-3. [CrossRef]

- An, J. Structural topic modeling for corporate social responsibility of food supply chain management: Evidence from FDA recalls on plant-based food products. Soc. Responsib. J. 2024, 20, 1089–1100. https://doi.org/10.1108/SRJ-07-2023-0412. [CrossRef]

- Ashraf, M.W.; Alanezi, F. Sustainable Eating Futures: A Case Study in Saudi Arabia. Future Food J. Food Agric. Soc. 2022, 11, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.17170/kobra-202204136024. [CrossRef]

- Assimakopoulos, F.; Vassilakis, C.; Margaris, D.; Kotis, K.; Spiliotopoulos, D. Artificial Intelligence Tools for the Agriculture Value Chain: Status and Prospects. Electronics 2024, 13, 22. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics13224362. [CrossRef]

- Bååth, J. How alternative foods become affordable: The co-construction of economic value on a direct-to-customer market. J. Rural Stud. 2022, 94, 63–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2022.05.017. [CrossRef]

- Basa, R. AI in Agriculture: Revolutionizing Precision Farming and Sustainable Crop Management. Int. J. Sci. Res. Comput. Sci. Eng. Inf. Technol. 2024, 10, 5. https://doi.org/10.32628/CSEIT241051040. [CrossRef]

- Berghen, B.V.; Vanermen, I.; Vranken, L. Citizen scientists: Unveiling motivations and characteristics influencing initial and sustained participation in an agricultural project. PLoS ONE 2024, 19. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0303103. [CrossRef]

- Betzler, S.; Kempen, R.; Mueller, K. Predicting sustainable consumption behavior: Knowledge-based, value-based, emotional and rational influences on mobile phone, food and fashion consumption. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Ecol. 2022, 29, 125–138. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504509.2021.1930272. [CrossRef]

- Blanco-Murcia, L.; Ramos-Mejía, M. Sustainable diets and meat consumption reduction in emerging economies: Evidence from Colombia. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6595. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11236595. [CrossRef]

- Bocean, C.G. A Longitudinal Analysis of the Impact of Digital Technologies on Sustainable Food Production and Consumption in the European Union. Foods 2024, 13, 1281. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods13081281. [CrossRef]

- Bosone, L.; Chevrier, M.; Zenasni, F. Consistent or inconsistent? The effects of inducing cognitive dissonance vs. cognitive consonance on the intention to engage in pro-environmental behaviors. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 902703. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.902703. [CrossRef]

- Büyükayman, E.; Shaheen, R.; Ossom, P.-E.O. The Silver Lining of the Pandemic! The Impact of Risk Perception of COVID-19 on Green Foods Purchase Intention. J. Sustain. Mark. 2022, 3, 53–71. https://doi.org/10.51300/jsm-2022-53. [CrossRef]

- Cao, S.; Xu, H.; Bryceson, K.P. Blockchain Traceability for Sustainability Communication in Food Supply Chains: An Architectural Framework, Design Pathway and Considerations. Sustainability 2023, 15, 13486. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151813486. [CrossRef]

- Carfora, V.; Cavallo, C.; Caso, D.; Del Giudice, T.; De Devitiis, B.; Viscecchia, R.; Nardone, G.; Cicia, G. Explaining consumer purchase behavior for organic milk: Including trust and green self-identity within the theory of planned behavior. Food Qual. Prefer. 2019, 76, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodqual.2019.03.006. [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Qiu, H.; Xiao, H.; He, W.; Mou, J.; Siponen, M. Consumption behavior of eco-friendly products and applications of ICT innovation. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 287. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.125436. [CrossRef]

- Chu, M.; Anders, S.; Deng, Q.; Contador, C.; Cisternas, F.; Caine, C.; Zhu, Y.; Yang, S.; Hu, B.; Liu, Z.; Tse, L.; Lam, H. The future of sustainable food consumption in China. Food Energy Secur. 2023, 12. https://doi.org/10.1002/fes3.405. [CrossRef]

- Clark, M.; Tilman, D. Comparative analysis of environmental impacts of agricultural production systems, agricultural input efficiency, and food choice. Environ. Res. Lett. 2017, 12, 064016. https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/aa6cd5. [CrossRef]

- Cooper, K.; Dedehayir, O.; Riverola, C.; Harrington, S.; Alpert, E. Exploring Consumer Perceptions of the Value Proposition Embedded in Vegan Food Products Using Text Analytics. Sustainability 2022, 14, 42075. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14042075. [CrossRef]

- Dogan, S.; Pala, U.; Özcan, N. Mobile applications as a next generation solution to prevent food waste. EGE Acad. Rev. 2023, 23, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.21121/eab.1181830. [CrossRef]

- Duong, C.D.; Nguyen, T.H.; Nguyen, H.L. How green intrinsic and extrinsic motivations interact, balance and imbalance with each other to trigger green purchase intention and behavior: A polynomial regression with response surface analysis. Heliyon 2023, 9, e20886. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e20886. [CrossRef]

- Dupont, J.; Harms, T.; Fiebelkorn, F. Acceptance of Cultured Meat in Germany-Application of an Extended Theory of Planned Behaviour. Foods 2022, 11, 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods11030424. [CrossRef]

- Elgaar, N.; Basha, N.K.; Hashim, H. Mapping the Landscape of Natural Food Consumption Barriers: A Bibliometric Analysis of Academic Publications. Int. J. Environ. Impacts 2024, 7, 445–453. https://doi.org/10.18280/ijei.070307. [CrossRef]

- Falcao, D.; Roseira, C. Mapping the socially responsible consumption gap research: Review and future research agenda. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2022, 46, 1718–1760. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijcs.12803. [CrossRef]

- Feil, A.A.; Cyrne, C.C.D.S.; Sindelar, F.C.W.; Barden, J.E.; Dalmoro, M. Profiles of sustainable food consumption: Consumer behavior towards organic food in southern region of Brazil. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 258, 120690. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.120690. [CrossRef]

- Floress, K.; Shwom, R.; Caggiano, H.; Slattery, J.; Cuite, C.; Schelly, C.; Halvorsen, K.E.; Lytle, W. Habitual food, energy, and water consumption behaviors among adults in the United States: Comparing models of values, norms, and identity. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2022, 85, 102396. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2021.102396. [CrossRef]

- Foerster, A.; Spencer, M. Corporate net zero pledges: A triumph of private climate regulation or more greenwash? Griffith Law Rev. 2023, 32, 110–142. https://doi.org/10.1080/10383441.2023.2210450. [CrossRef]

- Ford, H.; Gould, J.; Danner, L.; Bastian, S.E.P.; Yang, Q. “I guess it’s quite trendy”: A qualitative insight into young meat-eaters’ sustainable food consumption habits and perceptions towards current and future protein alternatives. Appetite 2023, 190, 107025. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2023.107025. [CrossRef]

- Gao, Z.; Li, C.; Bai, J.; Fu, J. Chinese consumer quality perception and preference of sustainable milk. China Econ. Rev. 2020, 59, 100004. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chieco.2016.05.004. [CrossRef]

- Gassler, B.; Xiao, Q.; Kühl, S.; Spiller, A. Keep on grazing: Factors driving the pasture-raised milk market in Germany. Br. Food J. 2018, 120, 452–467. https://doi.org/10.1108/BFJ-03-2017-0128. [CrossRef]

- Gavahian, M.; Sheu, S.-C.; Magnani, M.; Mousavi Khaneghah, A. Emerging technologies for mycotoxins removal from foods: Recent advances, roles in sustainable food consumption, and strategies for industrial applications. J. Food Process. Preserv. 2022, 46, 10. https://doi.org/10.1111/jfpp.15922. [CrossRef]

- Haider, V.; Essl, F.; Zulka, K.P.; Schindler, S. Achieving Transformative Change in Food Consumption in Austria: A Survey on Opportunities and Obstacles. Sustainability 2022, 14, 8685. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14148685. [CrossRef]

- Hannay, J. Over half of consumers would boycott companies caught greenwashing. Sustainability News 2023, September 19. Available online: https://sustainability-news.net/greenwashing/over-half-of-consumers-would-boycott-companies-caught-greenwashing/ (accessed on 19 September 2023).

- Hansmann, R.; Baur, I.; Binder, C.R. Increasing organic food consumption: An integrating model of drivers and barriers. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 275, 123058. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.123058. [CrossRef]

- Hasan, M.M.; Al Amin, M.; Arefin, M.S.; Mostafa, T. Green consumers’ behavioral intention and loyalty to use mobile organic food delivery applications: The role of social supports, sustainability perceptions, and religious consciousness. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2024, 26, 15953–16003. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10668-023-03284-z. [CrossRef]

- Heidenstrøm, N.; Hebrok, M. Towards realizing the sustainability potential within digital food provisioning platforms: The case of meal box schemes and online grocery shopping in Norway. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2022, 29, 831–850. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.spc.2021.06.030. [CrossRef]

- Hielkema, M.H.; Lund, T.B. Reducing meat consumption in meat-loving Denmark: Exploring willingness, behavior, barriers and drivers. Food Qual. Prefer. 2021, 93, 104257. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodqual.2021.104257. [CrossRef]

- Hoang, V.; Saviolidis, N.M.; Olafsdottir, G.; Bogason, S.; Hubbard, C.; Samoggia, A.; Nguyen, V.; Nguyen, D. Investigating and stimulating sustainable dairy consumption behavior: An exploratory study in Vietnam. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2023, 42, 183–195. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.spc.2023.09.016. [CrossRef]

- Jia, L.; Qiao, G. Quantification, Environmental Impact, and Behavior Management: A Bibliometric Analysis and Review of Global Food Waste Research Based on CiteSpace. Sustainability 2022, 14, 18. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141811293. [CrossRef]

- Kantamaturapoj, K.; McGreevy, S.; Thongplew, N.; Akitsu, M.; Vervoort, J.; Mangnus, A.; Ota, K.; Rupprecht, C.; Tamura, N.; Spiegelberg, M.; Kobayashi, M.; Pongkijvorasin, S.; Wibulpolprasert, S. Constructing practice-oriented futures for sustainable urban food policy in Bangkok. Futures 2022, 139. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.futures.2022.102949. [CrossRef]

- Kesse-Guyot, E.; Baudry, J.; Allès, B.; Péneau, S.; Touvier, M.; Méjean, C.; Amiot, M.-J.; Galan, P.; Hercberg, S.; Lairon, D. Determinants and correlates of consumption of organically produced foods: Results from the BioNutriNet project. Cah. Nutr. Diet. 2018, 53, 43–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cnd.2017.04.001. [CrossRef]

- Khan, K.; Iqbal, S.; Riaz, K.; Hameed, I. Organic food adoption motivations for sustainable consumption: Moderating role of knowledge and perceived price. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2022, 9. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2022.2143015. [CrossRef]

- Kociszewski, K.; Sobocinska, M.; Krupowicz, J.; Graczyk, A.; Mazurek-Lopacinska, K. Changes in the Polish market for agricultural organic products. Ekonomia I Srodowisko-Econ. Environ. 2023, 84, 259–286. https://doi.org/10.34659/eis.2023.84.1.547. [CrossRef]

- Kovács, I.; Lendvai, M.B.; Beke, J. The Importance of Food Attributes and Motivational Factors for Purchasing Local Food Products: Segmentation of Young Local Food Consumers in Hungary. Sustainability 2022, 14, 63224. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14063224. [CrossRef]

- Lamarque, M.; Tomé-Martín, P.; Moro-Gutiérrez, L. Personal and community values behind sustainable food consumption: A meta-ethnography. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2023, 7. https://doi.org/10.3389/fsufs.2023.1292887. [CrossRef]

- Lassoued, R.; Music, J.; Charlebois, S.; Smyth, S. Canadian Consumers’ Perceptions of Sustainability of Food Innovations. Sustainability 2023, 15, 86431. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15086431. [CrossRef]

- Lema-Blanco, I.; García-Mira, R.; Muñoz-Cantero, J.-M. Understanding Motivations for Individual and Collective Sustainable Food Consumption: A Case Study of the Galician Conscious and Responsible Consumption Network. Sustainability 2023, 15, 54111. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15054111. [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Lin, I.-K.; Chen, H.-S. Low Carbon Sustainable Diet Choices—An Analysis of the Driving Factors behind Plant-Based Egg Purchasing Behavior. Nutrients 2024, 16, 2604. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16162604. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wood, L.C.; Venkatesh, V.G.; Zhang, A.; Farooque, M. Barriers to sustainable food consumption and production in China: A fuzzy DEMATEL analysis from a circular economy perspective. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2021, 28, 1114–1129. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.spc.2021.07.028. [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Sintas, J.; Lamberti, G.; Lopez-Belbeze, P. Heterogenous social mechanisms drive the intention to purchase organic food. Br. Food J. 2024, 126, 378–393. https://doi.org/10.1108/BFJ-12-2023-1085. [CrossRef]

- Madureira, T.; Nunes, F.; Veiga, J.; Saralegui-Diez, P. Choices in sustainable food consumption: How Spanish low intake organic consumers behave. Agriculture 2021, 11, 111125. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture11111125. [CrossRef]

- Markoni, E.; Ha, T.M.; Götze, F.; Häberli, I.; Ngo, M.H.; Huwiler, R.M.; Delley, M.; Nguyen, A.D.; Bui, T.L.; Le, N.T.; Pham, B.D.; Brunner, T.A. Healthy or environmentally friendly? Meat consumption practices of green consumers in Vietnam and Switzerland. Sustainability 2023, 15, 11488. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151511488. [CrossRef]

- Matin, A.; Khoshtaria, T.; Todua, N.; Bareja-Wawryszuk, O.; Pajewski, T.; Todua, N. Determinants of Green Smartphone Application Adoption for Sustainable Food Consumption Among University Students. Int. J. Mark. Commun. New Media 2023, 11, 179–212. https://doi.org/10.54663/2182-9306.2023.v11.n21.179-212. [CrossRef]

- Medina, C.; Martínez-Fiestas, M.; Aranda, L.; Sánchez-Fernández, J. Is it an error to communicate CSR Strategies? Neural differences among consumers when processing CSR messages. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 126, 99–112. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.12.044. [CrossRef]

- Meijers, M.H.C.; Smit, E.S.; De Wildt, K.; Karvonen, S.-G.; Van Der Plas, D.; Van Der Laan, L.N. Stimulating Sustainable Food Choices Using Virtual Reality: Taking an Environmental vs Health Communication Perspective on Enhancing Response Efficacy Beliefs. Environ. Commun. 2022, 16, 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/17524032.2021.1943700. [CrossRef]

- Monterrosa, E.C.; Frongillo, E.A.; Drewnowski, A.; de Pee, S.; Vandevijvere, S. Sociocultural Influences on Food Choices and Implications for Sustainable Healthy Diets. Food Nutr. Bull. 2020, 41, 59S–73S. https://doi.org/10.1177/0379572120975874. [CrossRef]

- Morkunas, M.; Wang, Y.; Wei, J.; Galati, A. Systematic literature review on the nexus of food waste, food loss and cultural background. Int. Mark. Rev. 2024, 41, 683–716. https://doi.org/10.1108/IMR-12-2023-0366. [CrossRef]

- Nascimento, J.; Maria Correia Loureiro, S. Understanding the desire for green consumption: Norms, emotions, and attitudes. J. Bus. Res. 2024, 178. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2024.114675. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, H.V.; Nguyen, N.; Nguyen, B.K.; Greenland, S. Sustainable food consumption: Investigating organic meat purchase intention by Vietnamese consumers. Sustainability 2021, 13, 20953. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13020953. [CrossRef]

- Nygaard, A. Is sustainable certification’s ability to combat greenwashing trustworthy? Front. Sustain. 2023, 4. https://doi.org/10.3389/frsus.2023.1188069. [CrossRef]

- Nygaard, A.; Silkoset, R. Sustainable development and greenwashing: How blockchain technology information can empower green consumers. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2023, 32, 3801–3813. https://doi.org/10.1002/bse.3338. [CrossRef]

- O’Neill, C.; Hashem, S.; Moran, C.; McCarthy, M. Thou shalt not waste: Unpacking consumption of local food. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2022, 29, 851–861. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.spc.2021.06.016. [CrossRef]

- Özkaya, F.T.; Durak, M.G.; Doğan, O.; Bulut, Z.A.; Haas, R. Sustainable consumption of food: Framing the concept through Turkish expert opinions. Sustainability 2021, 13, 73946. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13073946. [CrossRef]

- Pais, D.F.; Marques, A.C.; Fuinhas, J.A. How to promote healthier and more sustainable food choices: The case of Portugal. Sustainability 2023, 15, 43868. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15043868. [CrossRef]

- Panou, A.; Karabagias, I.K. Biodegradable Packaging Materials for Foods Preservation: Sources, Advantages, Limitations, and Future Perspectives. Coatings 2023, 13, 7. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings13071176. [CrossRef]

- Parekh, V.; Svenfelt, Å. Taking sustainable eating practices from niche to mainstream: The perspectives of Swedish food-provisioning actors on barriers and potentials. Sustain. Sci. Pract. Policy 2022, 18, 292–308. https://doi.org/10.1080/15487733.2022.2044197. [CrossRef]

- Petrariu, R.; Sacala, M.; Pistalu, M.; Dinu, M.; Deaconu, M.; Constantin, M. A comprehensive food consumption and waste analysis based on ecommerce behaviour in the case of the AFER community. Transform. Bus. Econ. 2022, 21, 168–187.

- Polyportis, A.; De Keyzer, F.; van Prooijen, A.-M.; Peiffer, L.C.; Wang, Y. Addressing grand challenges in sustainable food transitions: Opportunities through the triple change strategy. Circ. Econ. Sustain. 2024. https://doi.org/10.1007/s43615-024-00457-4. [CrossRef]

- Poore, J.; Nemecek, T. Reducing food’s environmental impacts through producers and consumers. Science 2018, 360, 987–992. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aaq0216. [CrossRef]

- Possidónio, C.; Prada, M.; Graça, J.; Piazza, J. Consumer perceptions of conventional and alternative protein sources: A mixed-methods approach with meal and product framing. Appetite 2021, 156. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2020.104860. [CrossRef]

- Potter, C.; Bastounis, A.; Hartmann-Boyce, J.; et al. The Effects of Environmental Sustainability Labels on Selection, Purchase, and Consumption of Food and Drink Products: A Systematic Review. Environ. Behav. 2021, 53, 891–925. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013916521995473. [CrossRef]

- Pozelli Sabio, R.; Spers, E.E. Consumers’ Expectations on Transparency of Sustainable Food Chains. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2022, 6. https://doi.org/10.3389/fsufs.2022.853692. [CrossRef]

- Rahman, S.U.; Luomala, H. A Comparison of Motivational Patterns in Sustainable Food Consumption between Pakistan and Finland: Duties or Self-Reliance? J. Int. Food Agribus. Mark. 2021, 33, 459–486. https://doi.org/10.1080/08974438.2020.1816243. [CrossRef]

- Reipurth, M.F.S.; Hørby, L.; Gregersen, C.G.; Bonke, A.; Perez Cueto, F.J.A. Barriers and facilitators towards adopting a more plant-based diet in a sample of Danish consumers. Food Qual. Prefer. 2019, 73, 288–292. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodqual.2018.10.012. [CrossRef]

- Scalvedi, M.L.; Saba, A. Exploring local and organic food consumption in a holistic sustainability view. Br. Food J. 2018, 120, 749–762. https://doi.org/10.1108/BFJ-03-2017-0141. [CrossRef]

- Schouteten, J.J.; Gellynck, X.; Slabbinck, H. Do Fair Trade Labels Bias Consumers’ Perceptions of Food Products? A Comparison between a Central Location Test and Home-Use Test. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13031384. [CrossRef]

- Shen, X.; Xu, Q.; Liu, Q. Predicting sustainable food consumption across borders based on the theory of planned behavior: A meta-analytic structural equation model. PLoS ONE 2022, 17. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0275312. [CrossRef]

- Shove, E.; Pantzar, M.; Watson, M. The Dynamics of Social Practice: Everyday Life and How It Changes; SAGE Publications: London, UK, 2012.

- Singh, A.; Glinska-Newes, A. Modeling the public attitude towards organic foods: A big data and text mining approach. J. Big Data 2022, 9. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40537-021-00551-6. [CrossRef]

- Sodano, V.; Riverso, R.; Scafuto, F. Investigating the intention to reduce palm oil consumption. Qual. Access Success 2018, 19, 500–505.

- Springmann, M.; Godfray, H. C. J.; Rayner, M.; Scarborough, P. Analysis and valuation of the health and climate change cobenefits of dietary change. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, 4146–4151. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1523119113. [CrossRef]

- Stern, P.; Dietz, T.; Abel, T.; Guagnano, G.; Kalof, L. A Value-Belief-Norm Theory of Support for Social Movements: The Case of Environmentalism. Hum. Ecol. Rev. 1999, 6, 81–97.

- Sudbury-Riley, L.; Kohlbacher, F. Ethically minded consumer behavior: Scale review, development, and validation. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 2697–2710. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2015.11.005. [CrossRef]

- Sujayasree, O.J.; Chaitanya, A.K.; Bhoite, R.; Pandiselvam, R.; Kothakota, A.; Gavahian, M.; Mousavi Khaneghah, A. Ozone: An Advanced Oxidation Technology to Enhance Sustainable Food Consumption through Mycotoxin Degradation. Ozone Sci. Eng. 2022, 44, 17–37. https://doi.org/10.1080/01919512.2021.1948388. [CrossRef]

- Targino de Souza Pedrosa, G.; Pimentel, T.C.; Gavahian, M.; Lucena de Medeiros, L.; Pagán, R.; Magnani, M. The combined effect of essential oils and emerging technologies on food safety and quality. LWT 2021, 147. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lwt.2021.111593. [CrossRef]

- Terlau, W.; Hirsch, D. Sustainable consumption and the attitude-behaviour-gap phenomenon—Causes and measurements towards a sustainable development. Int. J. Food Syst. Dyn. 2015, 6, 159–174. https://doi.org/10.18461/ijfsd.v6i3.634. [CrossRef]

- Thaler, R. H.; Sunstein, C. R. Nudge: Improving decisions about health, wealth, and happiness, Yale University Press: New Haven, CT, USA, 2008; pp. x, 293.

- Thanki, S.; Guru, S.; Shah, B. Analyzing barriers for organic food consumption in India: A DEMATEL-based approach. Br. Food J. 2024, 126, 4459–4484. https://doi.org/10.1108/BFJ-06-2024-0598. [CrossRef]

- Theodoridis, P.; Zacharatos, T.; Boukouvala, V. Consumer behaviour and household food waste in Greece. Br. Food J. 2024, 126, 965–994. https://doi.org/10.1108/BFJ-02-2023-0141. [CrossRef]

- Tjärnemo, H.; Södahl, L. Swedish food retailers promoting climate smarter food choices-Trapped between visions and reality? J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2015, 24, 130–139. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2014.12.007. [CrossRef]

- Ukraisa, S.; Phlainoi, S.; Phlainoi, N.; Kantamaturapoj, K. Towards a new paradigm on food literacy and learning development in the Thai context. Kasetsart J. Soc. Sci. 2020, 41, 513–520. https://doi.org/10.34044/j.kjss.2020.41.3.09. [CrossRef]

- Vargas, A.; Moura, A.D.; Deliza, R.; Cunha, L. The Role of Local Seasonal Foods in Enhancing Sustainable Food Consumption: A Systematic Literature Review. Foods 2021, 10. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods10092206. [CrossRef]

- Vassallo, M.; Scalvedi, M.L.; Saba, A. Investigating psychosocial determinants in influencing sustainable food consumption in Italy. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2016, 40, 422–434. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijcs.12268. [CrossRef]

- Venter de Villiers, M.; Cheng, J.; Truter, L. The Shift Towards Plant-Based Lifestyles: Factors Driving Young Consumers’ Decisions to Choose Plant-Based Food Products. Sustainability 2024, 16, Article 20. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16209022. [CrossRef]

- Verain, M. C. D.; Snoek, H. M.; Onwezen, M. C.; Reinders, M. J.; Bouwman, E. P. Sustainable food choice motives: The development and cross-country validation of the Sustainable Food Choice Questionnaire (SUS-FCQ). Food Qual. Prefer. 2021, 93, 104267. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodqual.2021.104267. [CrossRef]

- Verain, M.; Dagevos, H.; Antonides, G. Sustainable food consumption. Product choice or curtailment? Appetite 2015, 91, 375–384. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2015.04.055. [CrossRef]

- Verfuerth, C.; Gregory-Smith, D.; Oates, C.J.; Jones, C.R.; Alevizou, P. Reducing meat consumption at work and at home: Facilitators and barriers that influence contextual spillover. J. Mark. Manag. 2021, 37, 671–702. https://doi.org/10.1080/0267257X.2021.1888773. [CrossRef]

- Vittersø, G.; Tangeland, T. The role of consumers in transitions towards sustainable food consumption. The case of organic food in Norway. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 92, 91–99. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2014.12.055. [CrossRef]

- Waldman, K.B.; Giroux, S.; Blekking, J.P.; Nix, E.; Fobi, D.; Farmer, J.; Todd, P.M. Eating sustainably: Conviction or convenience? Appetite 2023, 180, 106335. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2022.106335. [CrossRef]

- Wallnoefer, L.M.; Riefler, P.; Meixner, O. What drives the choice of local seasonal food? Analysis of the importance of different key motives. Foods 2021, 10, 112715. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods10112715. [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Pham, T. L.; Dang, V. T. Environmental Consciousness and Organic Food Purchase Intention: A Moderated Mediation Model of Perceived Food Quality and Price Sensitivity. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 850. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17030850. [CrossRef]

- Weinrich, R.; Elshiewy, O. A cross-country analysis of how food-related lifestyles impact consumers’ attitudes towards microalgae consumption. Algal Res. 2023, 70, 102999. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.algal.2023.102999. [CrossRef]

- Wen, H.; Chen, Y.; Wang, W.; Ding, L. A q-Rung orthopair fuzzy generalized TODIM method for prioritizing barriers to sustainable food consumption and production. J. Intell. Fuzzy Syst. 2023, 45, 5063–5074. https://doi.org/10.3233/JIFS-230526. [CrossRef]

- Willett, W.; Rockström, J.; Loken, B.; Springmann, M.; Lang, T.; Vermeulen, S.; Garnett, T.; Tilman, D.; DeClerck, F.; Wood, A.; Jonell, M.; Clark, M.; Gordon, L. J.; Fanzo, J.; Hawkes, C.; Zurayk, R.; Rivera, J. A.; Vries, W. D.; Sibanda, L. M.; … Murray, C. J. L. Food in the Anthropocene: The EAT–Lancet Commission on healthy diets from sustainable food systems. Lancet 2019, 393, 447–492. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31788-4. [CrossRef]

- Wojciechowska-Solis, J.; Kowalska, A.; Bieniek, M.; Ratajczyk, M.; Manning, L. Comparison of the Purchasing Behaviour of Polish and United Kingdom Consumers in the Organic Food Market during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19031137. [CrossRef]

- Xiao, J.; Yang, Z.; Li, Z.; Chen, Z. A review of social roles in green consumer behaviour. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2023, 47, 2033–2070. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijcs.12865. [CrossRef]

- Yadav, R.; Singh, P.K.; Srivastava, A.; Ahmad, A. Motivators and barriers to sustainable food consumption: Qualitative inquiry about organic food consumers in a developing nation. Int. J. Nonprofit Volunt. Sect. Mark. 2019, 24, 1650. https://doi.org/10.1002/nvsm.1650. [CrossRef]

- Yamoah, F.A.; Acquaye, A. Unravelling the attitude-behaviour gap paradox for sustainable food consumption: Insight from the UK apple market. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 217, 172–184. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.01.094. [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Yu, M. Too Good to Go: Combating Food Waste with Surprise Clearance (SSRN Scholarly Paper 4573386). Soc. Sci. Res. Netw. 2023. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4573386. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Al Mamun, A.; Long, S.; Gao, J.; Ali, K. A. M. The effect of environmental values, beliefs, and norms on social entrepreneurial intentions among Chinese university students. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2024, 11, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-03501-8. [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Dai, X.; Zhang, Y. The Government Subsidy Policies for Organic Agriculture Based on Evolutionary Game Theory. Sustainability 2024, 16, Article 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16062246. [CrossRef]

- Yue, B.; Sheng, G.; She, S.; Xu, J. Impact of Consumer Environmental Responsibility on Green Consumption Behavior in China: The Role of Environmental Concern and Price Sensitivity. Sustainability 2020, 12, Article 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12052074. [CrossRef]

- Zarei, A.; Maleki, F. From Decision to Run: The Moderating Role of Green Skepticism. J. Food Prod. Mark. 2018, 24, 96–116. https://doi.org/10.1080/10454446.2017.1266548. [CrossRef]

| Theme | Description | Co-occurring Themes | Examples from Studies |

|---|---|---|---|

| Health Concerns | Perceived health benefits, safety, and nutrition | Quality, Safety, Nutritional Value | Verain et al. (2015), Kesse-Guyot et al. (2018), Rahman & Luomala (2021), Hasan et al. (2024) |

| Environmental Awareness | Desire to reduce environmental footprint | Ethical Beliefs, Support for Local Economies | Verain et al. (2015), Kesse-Guyot et al. (2018), Vargas et al. (2021), Shen et al. (2022) |

| Ethical and Moral Beliefs | Concerns about animal welfare, social justice | Social Norms, Altruistic Values | Verain et al. (2015), Aguirre Sánchez et al. (2021), Cooper et al. (2022), Lema-Blanco et al. (2023) |

| Social and Personal Norms | Influence of societal expectations and personal values | Social Influence, Community Connection |

Verain et al. (2015), Aguirre Sánchez et al. (2021), Shen et al. (2022), Lopez-Sintas et al. (2024) |

| Taste and Quality | Sensory appeal and perceived quality of sustainable food | Health Benefits, Naturalness | Verain et al. (2015), Kesse-Guyot et al. (2018), Vargas et al. (2021), Lassoued et al. (2023) |

| Support for Local Economies | Desire to support local farmers and economies | Environmental Concerns, Social Responsibility |

Vargas et al. (2021), Kovács et al. (2022), Lassoued et al. (2023) |

| Knowledge and Awareness | Understanding the impact of food choices on sustainability | Education, Personal Experiences | Verain et al. (2015), Lema-Blanco et al. (2023) |

| Religious and Cultural Factors | Influence of religious beliefs and cultural practices | Health, Ethical Considerations | Verain et al. (2015), Hasan et al. (2024) |

| Emotional and Psychological Fulfillment | Emotional satisfaction and sense of accomplishment | Personal Well-being, Social Connections | Rahman & Luomala (2021), Kovács et al. (2022) |

| Economic and Practical Considerations | Affordability and practical aspects of purchasing sustainable products | Perceived Behavioral Control, Economic Status |

Shen et al. (2022), Lema-Blanco et al. (2023) |

| Theme | Frequency | Example Studies |

|---|---|---|

| Health Concerns | 20 | Verain et al. (2015), Kesse-Guyot et al. (2018), Rahman & Luomala (2021), Hasan et al. (2024) |

| Environmental Awareness | 19 | Verain et al. (2015), Kesse-Guyot et al. (2018), Vargas et al. (2021), Shen et al. (2022) |

| Ethical and Moral Beliefs | 15 | Verain et al. (2015), Aguirre Sánchez et al. (2021), Cooper et al. (2022), Lema-Blanco et al. (2023) |

| Social and Personal Norms | 12 | Verain et al. (2015), Aguirre Sánchez et al. (2021), Shen et al. (2022), Lopez-Sintas et al. (2024) |

| Taste and Quality | 14 | Verain et al. (2015), Kesse-Guyot et al. (2018), Vargas et al. (2021), Lassoued et al. (2023) |

| Support for Local Economies | 10 | Vargas et al. (2021), Kovács et al. (2022), Lassoued et al. (2023) |

| Knowledge and Awareness | 8 | Verain et al. (2015), Lema-Blanco et al. (2023) |

| Religious and Cultural Factors | 5 | Verain et al. (2015), Hasan et al. (2024) |

|

Emotional and Psychological Fulfillment |

6 | Rahman & Luomala (2021), Kovács et al. (2022) |

|

Economic and Practical Considerations |

7 | Shen et al. (2022), Lema-Blanco et al. (2023) |

| Motivation | 2015 | 2018 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | 2024 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Health | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Environmental Concerns | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Ethical and Moral Beliefs | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Social and Personal Norms | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Taste and Quality | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Support for Local Economies | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Knowledge and Awareness | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Religious Beliefs | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Emotional and Psychological Fulfillment | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Economic and Practical Considerations | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Categories of Barriers | Specific Barriers | Co-occurrence of Categories | Example of Articles |

|---|---|---|---|

| Economic | High prices, Reduced willingness to pay, Financial constraints | Economic, Availability, Knowledge | Elgaar et al., 2024; Gao et al., 2020; Pais et al., 2023; Hoang et al., 2023; Waldman et al., 2023; Blanco-Murcia & Ramos-Mejía, 2019; Reipurth et al., 2019; Yamoah & Acquaye, 2019; Vittersø & Tangeland, 2015; Vassallo et al., 2016; Bååth, 2022; Özkaya et al., 2021; Parekh & Svenfelt, 2022; Markoni et al., 2023; Liu et al., 2021; Thanki et al., 2024; Haider et al., 2022; Weinrich & Elshiewy, 2023; Wallnoefer et al., 2021; Verfuerth et al., 2021; Hansmann et al., 2020; Hielkema & Lund, 2021; Terlau & Hirsch, 2015; Polyportis et al., 2024; Wen et al., 2023; Ford et al., 2023; Yadav et al., 2019; Nguyen et al., 2021; Bocean, 2024; Morkunas et al., 2024; Dogan et al., 2023; Kociszewski et al., 2023; Petrariu et al., 2022; Gassler et al., 2018; Falcao & Roseira, 2022; Theodoridis et al., 2024 |

| Availability | Lack of availability, Limited variety, Unavailability | Availability, Economic, Knowledge | Elgaar et al., 2024; Hoang et al., 2023; Yamoah & Acquaye, 2019; Vittersø & Tangeland, 2015; Vassallo et al., 2016; Bååth, 2022; Özkaya et al., 2021; Parekh & Svenfelt, 2022; Markoni et al., 2023; Liu et al., 2021; Thanki et al., 2024; Haider et al., 2022; Weinrich & Elshiewy, 2023; Wallnoefer et al., 2021; Verfuerth et al., 2021; Hansmann et al., 2020; Hielkema & Lund, 2021; Terlau & Hirsch, 2015; Polyportis et al., 2024; Wen et al., 2023; Ford et al., 2023; Yadav et al., 2019; Nguyen et al., 2021; Bocean, 2024; Morkunas et al., 2024; Dogan et al., 2023; Kociszewski et al., 2023; Petrariu et al., 2022; Gassler et al., 2018; Falcao & Roseira, 2022; Theodoridis et al., 2024 |

| Knowledge | Lack of awareness, Insufficient information, Misunderstanding | Knowledge, Economic, Availability | Elgaar et al., 2024; Gao et al., 2020; Pais et al., 2023; Hoang et al., 2023; Waldman et al., 2023; Blanco-Murcia & Ramos-Mejía, 2019; Reipurth et al., 2019; Yamoah & Acquaye, 2019; Vittersø & Tangeland, 2015; Vassallo et al., 2016; Bååth, 2022; Özkaya et al., 2021; Parekh & Svenfelt, 2022; Markoni et al., 2023; Liu et al., 2021; Thanki et al., 2024; Haider et al., 2022; Weinrich & Elshiewy, 2023; Wallnoefer et al., 2021; Verfuerth et al., 2021; Hansmann et al., 2020; Hielkema & Lund, 2021; Terlau & Hirsch, 2015; Polyportis et al., 2024; Wen et al., 2023; Ford et al., 2023; Yadav et al., 2019; Nguyen et al., 2021; Bocean, 2024; Morkunas et al., 2024; Dogan et al., 2023; Kociszewski et al., 2023; Petrariu et al., 2022; Gassler et al., 2018; Falcao & Roseira, 2022; Theodoridis et al., 2024 |

| Social and Cultural | Family influence, Cultural traditions, Social norms | Social and Cultural, Economic, Knowledge | Pais et al., 2023; Hoang et al., 2023; Waldman et al., 2023; Blanco-Murcia & Ramos-Mejía, 2019; Reipurth et al., 2019; Yamoah & Acquaye, 2019; Vittersø & Tangeland, 2015; Vassallo et al., 2016; Bååth, 2022; Özkaya et al., 2021; Parekh & Svenfelt, 2022; Markoni et al., 2023; Liu et al., 2021; Thanki et al., 2024; Haider et al., 2022; Weinrich & Elshiewy, 2023; Wallnoefer et al., 2021; Verfuerth et al., 2021; Hansmann et al., 2020; Hielkema & Lund, 2021; Terlau & Hirsch, 2015; Polyportis et al., 2024; Wen et al., 2023; Ford et al., 2023; Yadav et al., 2019; Nguyen et al., 2021; Bocean, 2024; Morkunas et al., 2024; Dogan et al., 2023; Kociszewski et al., 2023; Petrariu et al., 2022; Gassler et al., 2018; Falcao & Roseira, 2022; Theodoridis et al., 2024 |

| Psychological | Resistance to change, Skepticism, Emotional attachment | Psychological, Economic, Knowledge | Elgaar et al., 2024; Gao et al., 2020; Pais et al., 2023; Hoang et al., 2023; Waldman et al., 2023; Blanco-Murcia & Ramos-Mejía, 2019; Reipurth et al., 2019; Yamoah & Acquaye, 2019; Vittersø & Tangeland, 2015; Vassallo et al., 2016; Bååth, 2022; Özkaya et al., 2021; Parekh & Svenfelt, 2022; Markoni et al., 2023; Liu et al., 2021; Thanki et al., 2024; Haider et al., 2022; Weinrich & Elshiewy, 2023; Wallnoefer et al., 2021; Verfuerth et al., 2021; Hansmann et al., 2020; Hielkema & Lund, 2021; Terlau & Hirsch, 2015; Polyportis et al., 2024; Wen et al., 2023; Ford et al., 2023; Yadav et al., 2019; Nguyen et al., 2021; Bocean, 2024; Morkunas et al., 2024; Dogan et al., 2023; Kociszewski et al., 2023; Petrariu et al., 2022; Gassler et al., 2018; Falcao & Roseira, 2022; Theodoridis et al., 2024 |

| Policy and Regulation | Lack of support, Policy fragmentation, Bureaucratic difficulties | Policy and Regulation, Economic, Knowledge | Vittersø & Tangeland, 2015; Vassallo et al., 2016; Parekh & Svenfelt, 2022; Liu et al., 2021; Thanki et al., 2024; Haider et al., 2022; Polyportis et al., 2024; Wen et al., 2023; Kociszewski et al., 2023; Falcao & Roseira, 2022 |

| Specific Barrier | Frequency | Example Articles |

|---|---|---|

| High Price | 18 | Elgaar et al. (2024), Gao et al. (2020), Pais et al. (2023), Hoang et al. (2023) |

| Lack of Availability | 14 | Elgaar et al. (2024), Yamoah & Acquaye (2019), Parekh & Svenfelt (2022) |

| Lack of Knowledge/Awareness | 16 | Gao et al. (2020), Özkaya et al. (2021), Liu et al. (2021) |

| Consumer Resistance/Skepticism | 10 | Elgaar et al. (2024), Nguyen et al. (2021), Ford et al. (2023) |

| Habitual Behavior | 8 | Pais et al. (2023), Hielkema & Lund (2021), Verfuerth et al. (2021) |

| Cultural and Social Norms | 12 | Blanco-Murcia & Ramos-Mejía (2019), Markoni et al. (2023), Parekh & Svenfelt (2022) |

| Distrust in Labels/Certifications | 7 | Vittersø & Tangeland (2015), Nguyen et al. (2021), Ford et al. (2023) |

| Perceived Quality/Taste | 6 | Vittersø & Tangeland (2015), Haider et al. (2022), Weinrich & Elshiewy (2023) |

| Lack of Information | 9 | Pais et al. (2023), Liu et al. (2021), Hansmann et al. (2020) |

| Psychological Barriers | 5 | Elgaar et al. (2024), Ford et al. (2023), Verfuerth et al. (2021) |

| Economic and Marketing Factors | 6 | Hoang et al. (2023), Parekh & Svenfelt (2022), Bååth (2022) |

| Functional Barriers | 4 | Elgaar et al. (2024), Reipurth et al. (2019), Terlau & Hirsch (2015) |

| Family Influence | 5 | Pais et al. (2023), Markoni et al. (2023), Verfuerth et al. (2021) |

| Environmental and Physical Context | 4 | Hoang et al. (2023), Liu et al. (2021), Parekh & Svenfelt (2022) |

| Lack of Unified Policy/Regulation | 4 | Vassallo et al. (2016), Parekh & Svenfelt (2022), Liu et al. (2021) |

| Food Safety Concerns | 3 | Markoni et al. (2023), Ford et al. (2023), Liu et al. (2021) |

| Lack of Motivation | 3 | Haider et al. (2022), Verfuerth et al. (2021), Terlau & Hirsch (2015) |

| Miscommunication | 2 | Hoang et al. (2023), Parekh & Svenfelt (2022) |

| Lack of Transparent Information | 3 | Polyportis et al. (2024), Parekh & Svenfelt (2022), Liu et al. (2021) |

| Greenwashing | 2 | Polyportis et al. (2024), Ford et al. (2023) |

| Lack of Collaboration | 2 | Liu et al. (2021), Parekh & Svenfelt (2022) |

| Lack of Environmental Education | 2 | Liu et al. (2021), Morkunas et al. (2024) |

| Lack of Economies of Scale | 1 | Liu et al. (2021) |

| Lack of Standards and Benchmarking | 1 | Liu et al. (2021) |

| Distrust in Labels | 1 | Haider et al. (2022) |

| Lack of State Support | 1 | Kociszewski et al. (2023) |

| Low Yields and High Production Costs | 1 | Kociszewski et al. (2023) |

| Bureaucratic and Administrative Difficulties | 1 | Kociszewski et al. (2023) |

| Digital Exclusion | 1 | Bocean (2024) |

| Technical Complexity | 1 | Bocean (2024) |

| Data Security Concerns | 1 | Bocean (2024) |

| Training and Adoption Challenges | 1 | Bocean (2024) |

| Resistance to Change | 1 | Bocean (2024) |

| Economic Disparities | 1 | Bocean (2024) |

| Lack of Time | 1 | Hansmann et al. (2020) |

| Perceived Environmental Impact | 1 | Hansmann et al. (2020) |

| Lack of Sense of Responsibility | 1 | Falcao & Roseira (2022) |

| Contextual and Social Factors | 1 | Falcao & Roseira (2022) |

| Sourcing Aspects | 1 | Falcao & Roseira (2022) |

| Shopping Behaviors and Meal Planning Trends | 1 | Theodoridis et al. (2024) |

| Insufficient Information Campaigns | 1 | Theodoridis et al. (2024) |

| Year | High Price | Lack of Availability | Lack of Knowledge/Awareness | Consumer Resistance/Skepticism | Habitual Behavior | Cultural and Social Norms | Distrust in Labels/Certifications | Perceived Quality/Taste | Lack of Information |

Psychological Barriers |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2015 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2016 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2018 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2019 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| 2020 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2021 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 2022 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2023 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 2024 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Categories of Technologies | Specific Technology | Example of Article |

|---|---|---|

| Alternative Proteins | Plant-Based Alternative Protein (PBM/S), Lab-grown meat/seafood (CBM/S) | Ford et al. (2023) |

| Dairy Alternatives | Precision fermented dairy products (PFDs) | Ford et al. (2023) |

| Decontamination | Cold plasma and ultrasound, Mycotoxin decontamination, Ozone | Gavahian et al. (2022), Sujayshree et al. (2022) |

| Preservation | Essential oils (EOs), Emerging Technologies (ETs) | Targino de Souza Pedrosa et al. (2021) |

| Digital Platforms | Meal box schemes and online food shopping | Heidenstrøm & Hebrok (2022) |

| Food Literacy | Food production technologies, Storage, transport and processing technologies, Transparency and traceability in the supply chain | Ukraisa et al. (2020) |

| Smart Technologies | AI and GPS, 3D printing | Ashraf & Alanezi (2022 |

| Digital Transformation | Smart refrigerators and apps | Ashraf & Alanezi (2022) |

| Digital Technologies | AI, Big Data, IoT, cloud computing, Monitoring and managing supply chains | Bocean (2024) |

| Waste Management | Mobile applications, digital platforms, IoT systems, Lean management techniques, Food surplus management, Demand analysis and waste forecasting | Jia & Qiao (2022) |

| Smart Systems | AI, Smart shopping assistants | Kantamaturapoj et al. (2022) |

| Educational Tools | VR and mobile technologies | Kantamaturapoj et al. (2022) |

| Smart Gardening | Smart gardening systems and chemical test kits | Kantamaturapoj et al. (2022) |

| Traceability | Blockchain | Dupont et al. (2022) |

| ICT | Information and communication technologies (ICT), ICT innovations, ICT platforms | Betzler et al. (2022), Chen et al. (2021) |

| Digital Platforms | Online platforms and social media | Xiao et al. (2023) |

| Traceability | IoT and blockchain | Chen et al. (2021) |

| Mobile Apps | Mobile apps | Chen et al. (2021) |

| Categories of Technologies | Frequency of Appearance | Specific Technology |

|---|---|---|

| Alternative Proteins | 2 | Plant-Based Alternative Protein (PBM/S), Lab-grown meat/seafood (CBM/S) |

| Dairy Alternatives | 1 | Precision fermented dairy products (PFDs) |

| Decontamination | 3 | Cold plasma and ultrasound, Mycotoxin decontamination, Ozone |

| Preservation | 2 | Essential oils (EOs), Emerging Technologies (ETs) |

| Digital Platforms | 2 | Meal box schemes and online food shopping, Online platforms and social media |

| Food Literacy | 3 | Food production technologies, Storage, transport and processing technologies, Transparency and traceability in the supply chain |

| Smart Technologies | 2 | AI and GPS, 3D printing |

| Digital Transformation | 1 | Smart refrigerators and apps |

| Digital Technologies | 2 | AI, Big Data, IoT, cloud computing, Monitoring and managing supply chains |

| Waste Management | 4 | Mobile applications, digital platforms, IoT systems, Lean management techniques, Food surplus management, Demand analysis and waste forecasting |

| Smart Systems | 2 | AI, Smart shopping assistants |

| Educational Tools | 1 | VR and mobile technologies |

| Smart Gardening | 1 | Smart gardening systems and chemical test kits |

| Traceability | 2 | Blockchain, IoT and blockchain |

| ICT | 3 | Information and communication technologies (ICT), ICT innovations, ICT platforms |

| Year | Alternative Proteins | Preservation | Digital Platforms | Food Literacy | Smart Technologies | Digital Transformation | Waste Management | Smart Systems | Educational Tools | Traceability | ICT |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2020 | √ | ||||||||||

| 2021 | √ | ||||||||||

| 2022 | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||

| 2023 | √ | √ | |||||||||

| 2024 | √ |

| Category of Corporate Initiatives | Frequency | Specific Initiatives |

|---|---|---|

| Consumer Education and Awareness | 1 | Educating consumers about sustainable products |

| Product Availability and Diversity | 1 | Improving availability and variety of sustainable products |

| Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) | 3 | Adopting CSR measures, reducing carbon footprint, fair labor practices |

| Promotion and Marketing | 1 | Offering discounts, awareness campaigns for organic products |

| Labeling and Certification | 2 | Supporting certification programs |

| Fairtrade and Ethical Trade | 1 | Promoting Fairtrade, ensuring fair wages and decent working conditions |

| Environmental Policies and Practices | 1 | Addressing climate change, promoting organic/local/seasonal foods, minimizing food waste |

| Stakeholder Engagement and Policy Development | 1 | Engaging stakeholders, developing food safety strategies (An, 2024) |

| Category | CSR | Promotion & Marketing | Labeling & Certification | Consumer Education | Product Availability & Diversity | Fairtrade & Ethical Trade | Green Product Lines | Environmental Policies | Stakeholder Engagement |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CSR | 5 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| Promotion & Marketing | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Labeling & Certification | 2 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Consumer Education | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Product Availability & Diversity | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Fairtrade & Ethical Trade | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Green Product Lines | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| Environmental Policies | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| Stakeholder Engagement | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Year | Category of Corporate Initiatives | Specific Initiatives |

|---|---|---|

| 2015 | Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) | Adopting CSR measures, reducing carbon footprint, fair labor practices |

| 2015 | Promotion and Marketing | Offering discounts, awareness campaigns for organic products |

| 2015 | Labeling and Certification | Supporting certification programs |

| 2015 | Environmental Policies and Practices | Addressing climate change, promoting organic/local/seasonal foods, minimizing food waste |

| 2016 | Fairtrade and Ethical Trade | Promoting Fairtrade, ensuring fair wages and decent working conditions |

| 2018 | Consumer Education and Awareness | Educating consumers about sustainable products |

| 2018 | Product Availability and Diversity | Improving availability and variety of sustainable products |

| 2018 | Improving Corporate Skills | Building green procurement intentions and information seeking |

| 2019 | Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) | Engaging in CSR activities, reducing carbon footprint, using sustainable materials |

| 2019 | Green Product Lines | Development and promotion of organic products |

| 2019 | Sustainability Certifications | Obtaining certifications to assure sustainability |

| 2021 | Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) | Adopting ethical and sustainable practices, reducing carbon footprint, fair labor practices |

| 2024 | Stakeholder Engagement and Policy Development | Engaging stakeholders, developing food safety strategies |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).