Submitted:

19 December 2023

Posted:

20 December 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Literature review

2.1. Green purchasing behaviour

2.2. Environmental attitude

2.3. Environmental awareness

2.4. Green Advertising

2.5. Ecolabel

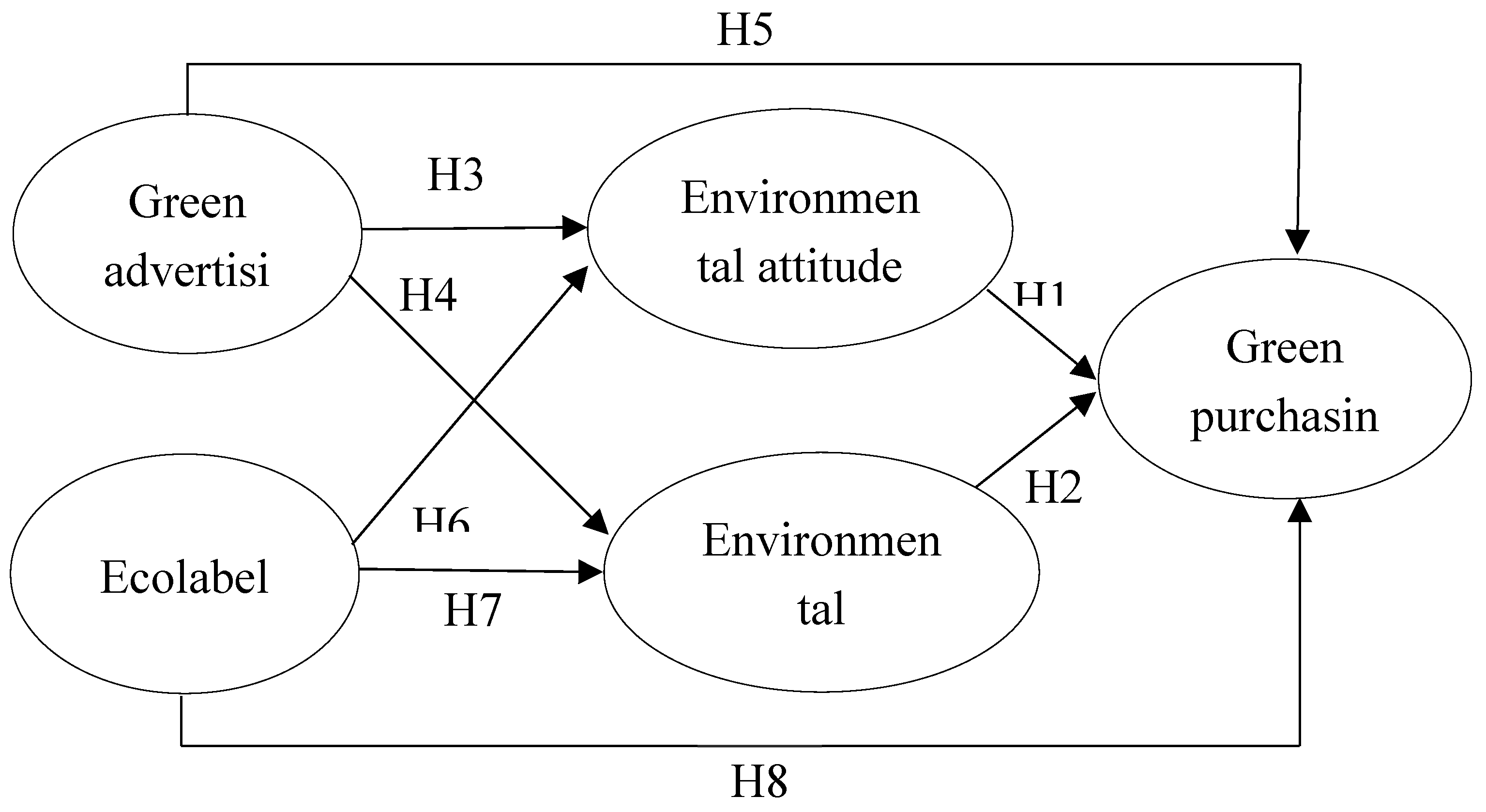

2.6. Conceptual model

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Instrument design and data collection

3.2. Internal consistency of the instrument

3.3. Data analysis

4. Results

4.1. Demographic characteristic of respondents

4.2. Estimation of the measurement model

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Variable | Item | Answer option |

| Environmental attitude [54] | EAT1 | I am very concerned about the environment |

| EAT2 | I am willing to reduce my consumption to help the environment. | |

| EAT3 | I would contribute financially to help protect the environment. | |

| EAT4 | I have asked my family to recycle some of the things we use. | |

| Environmental awareness [54] | EAW1 | I believe that humanity is seriously abusing the environment. |

| EAW2 | I think that humans produce disastrous consequences in nature. | |

| EZW3 | I consider that the balance of nature is very delicate and easily upset. | |

| EAW4 | I think that one must live in harmony with nature in order to survive. | |

| Green purchasing behaviour [20] | GPB1 | I buy organic products regularly. |

| GPB2 | I buy organic products for my daily needs. | |

| GPB3 | I have bought organic products for the last few months. | |

| GPB4 | I buy organic products, although there are conventional alternatives. | |

| Green advertising [13] | GAD1 | I tend to focus on advertising messages that relate to the environment. |

| GAD2 | I think brands that use advertising messages about the environment are good. | |

| GAD3 | I pay attention to products that develop advertisements that relate to the environment. | |

| GAD4 | I find green advertising valuable in my opinion. | |

| Ecolabels [17,41] | ECL1 | I consider the eco-labels displayed on the product to be a good way to inform consumers. |

| ECL2 | I believe that eco-labelled products meet reliable environmental quality standards. | |

| ECL3 | The presence of certified organic labels increases my credibility in a product. | |

| ECL4 | I believe that eco-labeled products are really committed to protecting the environment. |

References

- Jaiswal, D.; Kant, R. Green purchasing behaviour: A conceptual framework and empirical investigation of Indian consumers. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 2018, 41, 60–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrión Bósquez, N.G.; Arias-Bolzmann, L.G.; Martínez Quiroz, A.K. The influence of price and availability on university millennials’ organic food product purchase intention. British Food Journal 2023, 125, 536–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Liu, N.; Zhao, M. Factors and mechanisms affecting green consumption in China: A multilevel analysis. Journal of cleaner production 2019, 209, 481–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opoku, R.; Famiyeh, S.; Kwarteng, A. Environmental considerations in the purchase decisions of Ghanaian consumers. Social Responsibility Journal 2020, 16, 129–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kautish, P.; Paul, J.; Sharma, R. The moderating influence of environmental consciousness and recycling intentions on green purchase behavior. Journal of Cleaner Production 2019, 228, 1425–1436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nosi, C.; Zollo, L.; Rialti, R.; Ciappei, C. Sustainable consumption in organic food buying behavior: the case of quinoa. British Food Journal 2020, 122, 976–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, Y.; Rahman, Z. Factors affecting green purchase behaviour and future research directions. International Strategic management review 2015, 3, 128–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liobikiene, G.; Bernatonien˙e, J. Why determinants of green purchase cannot be treated equally? The case of green cosmetics:˙ Literature review. Journal of Cleaner Production 2017, 162, 109–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacy, P.; Hayward, R. A new era of sustainability in emerging markets? Insights from a global CEO study by the United Nations Global Compact and Accenture. Corporate Governance: The international journal of business in society 2011, 11, 348–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Fan, J.; Zhao, D.; Yang, S.; Fu, Y. Predicting consumers’ intention to adopt hybrid electric vehicles: using an extended version of the theory of planned behavior model. Transportation 2016, 43, 123–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashif, U.; Hong, C.; Naseem, S. Assessment of millennial organic food consumption and moderating role of food neophobia in Pakistan Assessment of millennial organic food consumption and moderating role of food neophobia in Pakistan. Current Psychology, Springer 2021.

- Wang, J.; Wang, S.; Xue, H.; Wang, Y.; Li, J. Green image and consumers’ word-of-mouth intention in the green hotel industry: The moderating effect of Millennials. Journal of cleaner production 2018, 181, 426–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Luo, B.; Wang, S.; Fang, W. What you see is meaningful: Does green advertising change the intentions of consumers to purchase eco-labeled products? Business Strategy and the Environment 2021, 30, 694–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farzin, M.; Shababi, H.; Shirchi Sasi, G.; Sadeghi, M.; Makvandi, R. The determinants of eco-fashion purchase intention and willingness to pay. Spanish Journal of Marketing-ESIC 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaeger, A.K.; Weber, A. Can you believe it? The effects of benefit type versus construal level on advertisement credibility and purchase intention for organic food. Journal of Cleaner Production 2020, 257, 120543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, N.K.; Kushwaha, G.S. Eco-labels: A tool for green marketing or just a blind mirror for consumers. Electronic Green Journal 2019, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riskos, K.; Dekoulou, P.; Mylonas, N.; Tsourvakas, G. Ecolabels and the attitude–behavior relationship towards green product purchase: A multiple mediation model. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qayyum, A.; Jamil, R.A.; Sehar, A. Impact of green marketing, greenwashing and green confusion on green brand equity. Spanish Journal of Marketing-ESIC 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murali, K.; Lim, M.K.; Petruzzi, N.C. The effects of ecolabels and environmental regulation on green product development. Manufacturing & Service Operations Management 2019, 21, 519–535. [Google Scholar]

- Carrión Bósquez, N.G.; Arias-Bolzmann, L.G. Factors influencing green purchasing inconsistency of Ecuadorian millennials. British Food Journal 2022, 124, 2461–2480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taufique, K.M.R.; Vaithianathan, S. A fresh look at understanding Green consumer behavior among young urban Indian consumers through the lens of Theory of Planned Behavior. Journal of cleaner production 2018, 183, 46–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woo, E.; Kim, Y.G. Consumer attitudes and buying behavior for green food products: From the aspect of green perceived value (GPV). British Food Journal 2019, 121, 320–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amalia, F.A.; Sosianika, A.; Suhartanto, D. Indonesian millennials’ halal food purchasing: merely a habit? British Food Journal 2020, 122, 1185–1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, M.I.; Nawaz Mir, F.; Hussain, S.; Hyder, S.; Anwar, A.; Khan, Z.U.; Nawab, N.; Shah, S.F.A.; Waseem, M. Contradictory results on environmental concern while re-visiting green purchase awareness and behavior. Asia Pacific Journal of Innovation and Entrepreneurship 2019, 13, 17–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Qin, Z.; Yuan, Q. The impact of eco-label on the young Chinese generation: The mediation role of environmental awareness and product attributes in green purchase. Sustainability 2019, 11, 973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, N.D.; Kumar, V.R. Three decades of green advertising–a review of literature and bibliometric analysis. Benchmarking: An International Journal 2021, 28, 1934–1958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazaea, S.A.; Al-Matari, E.M.; Zedan, K.; Khatib, S.F.; Zhu, J.; Al Amosh, H. Green purchasing: Past, present and future. Sustainability 2022, 14, 5008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Testa, F.; Sarti, S.; Frey, M. Are green consumers really green? Exploring the factors behind the actual consumption of organic food products. Business Strategy and the Environment 2019, 28, 327–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naderi, I.; Van Steenburg, E. Me first, then the environment: Young Millennials as green consumers. Young Consumers 2018, 19, 280–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, B.; Manrai, A.K.; Manrai, L.A. Purchasing behaviour for environmentally sustainable products: A conceptual framework and empirical study. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 2017, 34, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sh. Ahmad, F.; Rosli, N.T.; Quoquab, F. Environmental quality awareness, green trust, green self-efficacy and environmental attitude in influencing green purchase behaviour. International Journal of Ethics and Systems 2022, 38, 68–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prakash, G.; Singh, P.K.; Ahmad, A.; Kumar, G. Trust, convenience and environmental concern in consumer purchase intention for organic food. Spanish Journal of Marketing-ESIC 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Bülbül, H.; Büyükkeklik, A.; Topal, A.; Özog˘lu, B. The relationship between environmental awareness, environmental behaviors, and carbon footprint in Turkish households. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 2020, 27, 25009–25028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suárez-Varela, M.; Guardiola, J.; González-Gómez, F. Do pro-environmental behaviors and awareness contribute to improve subjective well-being? Applied Research in Quality of Life 2016, 11, 429–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shelest, K.D.; Ionov, V.V.; Tikhomirov, L.Y. Environmental awareness raising through universities–city authorities’ cooperation. International Journal of Sustainability in Higher Education 2017, 18, 39–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aliman, M.; Astina, I.K.; others. Improving Environmental Awareness of High School Students’ in Malang City through Earthcomm Learning in the Geography Class. International Journal of Instruction 2019, 12, 79–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansmann, R.; Laurenti, R.; Mehdi, T.; Binder, C.R. Determinants of pro-environmental behavior: A comparison of university students and staff from diverse faculties at a Swiss University. Journal of Cleaner Production 2020, 268, 121864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carducci, A.; Fiore, M.; Azara, A.; Bonaccorsi, G.; Bortoletto, M.; Caggiano, G.; Calamusa, A.; De Donno, A.; De Giglio, O.; Dettori, M.; others. Pro-environmental behaviors: Determinants and obstacles among Italian university students. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2021, 18, 3306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuriev, A.; Dahmen, M.; Paillé, P.; Boiral, O.; Guillaumie, L. Pro-environmental behaviors through the lens of the theory of planned behavior: A scoping review. Resources, Conservation and Recycling 2020, 155, 104660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyilasy, G.; Gangadharbatla, H.; Paladino, A. Perceived greenwashing: The interactive effects of green advertising and corporate environmental performance on consumer reactions. Journal of business ethics 2014, 125, 693–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen-Viet, B. Understanding the influence of eco-label, and green advertising on green purchase intention: The mediating role of green brand equity. Journal of Food Products Marketing 2022, 28, 87–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tucker, E.M.; Rifon, N.J.; Lee, E.M.; Reece, B.B. Consumer receptivity to green ads: A test of green claim types and the role of individual consumer characteristics for green ad response. Journal of advertising 2012, 41, 9–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, W.H.; Malek, K.; Roberts, K.R. The effectiveness of green advertising in the convention industry: An application of a dual coding approach and the norm activation model. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management 2019, 39, 185–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahbar, E.; Wahid, N.A. Investigation of green marketing tools’ effect on consumers’ purchase behavior. Business strategy series 2011, 12, 73–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, H.; Zhang, L.; Xie, G.X. Message framing in green advertising: The effect of construal level and consumer environmental concern. International Journal of Advertising 2015, 34, 158–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthes, J.; Wonneberger, A.; Schmuck, D. Consumers’ green involvement and the persuasive effects of emotional versus functional ads. Journal of Business Research 2014, 67, 1885–1893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pittman, M.; Oeldorf-Hirsch, A.; Brannan, A. Green advertising on social media: Brand authenticity mediates the effect of different appeals on purchase intent and digital engagement. Journal of Current Issues & Research in Advertising 2022, 43, 106–121. [Google Scholar]

- Schmuck, D.; Matthes, J.; Naderer, B. Misleading consumers with green advertising? An affect–reason–involvement account of greenwashing effects in environmental advertising. Journal of Advertising 2018, 47, 127–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panopoulos, A.; Poulis, A.; Theodoridis, P.; Kalampakas, A. Influencing Green Purchase Intention through Eco Labels and User-Generated Content. Sustainability 2022, 15, 764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hameed, I.; Waris, I. Eco labels and eco conscious consumer behavior: the mediating effect of green trust and environmental concern. Hameed, Irfan and Waris, Idrees (2018): Eco Labels and Eco Conscious Consumer Behavior: The Mediating Effect of Green Trust and Environmental Concern. Published in: Journal of Management Sciences 2018, 5, 86–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, H.; Le, H. The effect of agricultural product eco-labelling on green purchase intention. Management Science Letters 2020, 10, 2813–2820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alamsyah, D.P.; Mulyani, Y.U.; Othman, N.A.; Ibrahim, N.R.W. Green customer behavior: mediation model of green purchase. Int. J. Psychosoc. Rehabil. 2020, 24, 2568–2577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-khawaldah, R.; Al-zoubi, W.; Alshaer, S.; Almarshad, M.; ALShalabi, F.; Altahrawi, M.; Al-Hawary, S. Green supply chain management and competitive advantage: The mediating role of organizational ambidexterity. Uncertain Supply Chain Management 2022, 10, 961–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trivedi, R.H.; Patel, J.D.; Acharya, N. Causality analysis of media influence on environmental attitude, intention and behaviors leading to green purchasing. Journal of cleaner production 2018, 196, 11–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alamsyah, D.P.; Othman, N.A. Consumer awareness towards eco-friendly product through green advertising: Environmentally friendly strategy. Earth and Environmental Science 2021, 824, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alamsyah, D.; Aryanto, R.; Utama, I.; Marita, L.; Othman, N. (). The antecedent model of green awareness customer. Management Science Letters, 2020, 10, 2431–2436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alamsyah, D.; Othman, N.; Bakri, M.; Udjaja, Y.; Aryanto, R. Green awareness through consumer awareness of green products and ecological labels in the future environmental knowledge and perceived quality. Management Science Letters. 2021, 11, 271–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C. (2011). Feeling ambivalent about going green, implications for green advertising processing. Journal of Advertising. 2011, 40, 19–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C. Are guilt appeals a panacea in green advertising? The right formula of issue proximity and environmental consciousness. International Journal of Advertising. 2013, 31, 741–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kao, T.F.; Du, Y.Z. A study on the influence of green advertising design and environmental emotion on advertising effect. Journal of Cleaner Production. 2020, 242, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J. Consumer responses toward green advertising: The effects of gender, advertising skepticism, and green motive attribution. Journal of Marketing Communications, 2020, 26, 414–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthes, J.; Wonneberger, A. The skeptical green consumer revisited: Testing the relationship between green consumerism and skepticism toward advertising. Journal of Advertising. 2014, 43, 115–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmuck, D.; Matthes, J.; Naderer, B. Misleading consumers with green advertising? An affect–reason–involvement account of greenwashing effects in environmental advertising, Journal of Advertising. 2018, 47, 127–145. [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes, J.; Segev, S.; Leopold, J.K. When consumers learn to spot deception in advertising: testing a literacy intervention to combat greenwashing. International Journal of Advertising. 2020, 39, 1115–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoyos-Vallejo, C.A.; Carrión-Bósquez, N.G.; and Ortiz-Regalado, O. The influence of skepticism on the university Millennials’ organic food product purchase intention. British Food Journal. 2023, 125. No. 10, 3800–3816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herman, L.E.; Udayana, I.B.; Farida, N. Young generation and environmental friendly awareness: does it the impact of green advertising? Business: Theory and Practice. 2021, 22, 159–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolović, T.; Vlastelica, T.; Krstić, J. Consumers‘ Perception of Green Advertising and Eco-Labels: The Effect on Purchasing Intentions. Marketing. 2023, 54, 54–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drăgan, G.B.; Panait, A.A.; Schin, G.C. Tracking precursors of entrepreneurial intention: the case of researchers involved in eco-label industry. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 2021, 18, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ateş, H. Understanding students’ and science educators’ eco-labeled food purchase behaviors: Extension of theory of planned behavior with self-identity, personal norm, willingness to pay, and eco-label knowledge. Ecology of Food and Nutrition, 2021, 60, 454–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristics | Category | N | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| City | Quito | 218 | 51 |

| Guayaquil | 212 | 49 | |

| Education level | Postgraduate | 155 | 36 |

| Undergraduate | 275 | 64 | |

| Millennial cohort | Older Millennials (35 to 44 years old) | 185 | 43 |

| Mid Millennials (29 to 34 years old) | 130 | 30 | |

| Younger Millennials (23 to 28 years old) | 115 | 27 | |

| Gender | Male | 247 | 57 |

| Female | 183 | 43 | |

| n = 430 | |||

| Variable | Item | Loading factor | Cronbach alpha | CR | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Environmental attitude (EAT) | EAT1 | 0.955 | 0.943 | 0.948 | 0,86 |

| EAT2 | 0.916 | ||||

| EAT3 | 0.911 | ||||

| Environmental awareness (EAW) | EAW2 | 0.945 | 0.932 | 0.938 | 0.835 |

| EAW3 | 0.871 | ||||

| EAW4 | 0.924 | ||||

| Green purchasing behaviour (GPB) | GPB1 | 0.696 | 0.857 | 0.889 | 0.670 |

| GPB2 | 0.911 | ||||

| GPB3 | 0.730 | ||||

| GPB4 | 0.913 | ||||

| Green advertising (GAD) | GAD2 | 0.906 | 0.881 | 0.894 | 0.739 |

| GAD3 | 0.783 | ||||

| GAD4 | 0.884 | ||||

| Eco-labels (ECL) | ECL1 | 0.866 | 0.825 | 0.864 | 0.680 |

| ECL3 | 0.862 | ||||

| ECL4 | 0.739 | ||||

| Alfa total | 0.824 | ||||

| F1 | F2 | F3 | F4 | F5 | SR AVE | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F1 | 0.860 a | 0.927 | ||||

| F2 | 0.135** | 0.835 a | 0.913 | |||

| F3 | 0.238** | 0.173** | 0.670 a | 0.818 | ||

| F4 | 0.220** | 0.193** | 0.291** | 0.739 a | 0.859 | |

| F5 | 0.105* | 0.224** | 0.137** | 0.048* | 0.680 a | 0.824 |

| a AVE, ** Correlation is significant at 0.01 (bilateral), * Correlation is significant at 0.05 (bilateral). Note: F1: Environmental attitude, F2: Environmental awareness, F3: Green purchasing; F4: Green advertising; F5: Ecolabel. F1-F3; F2-F3; F4-F1; F4-F2; F4-F3; F5-F2, and F5-F3 had significant correlation at bilateral level 0.01. F5-F1 had a significant correlation at bilateral level 0.05 | ||||||

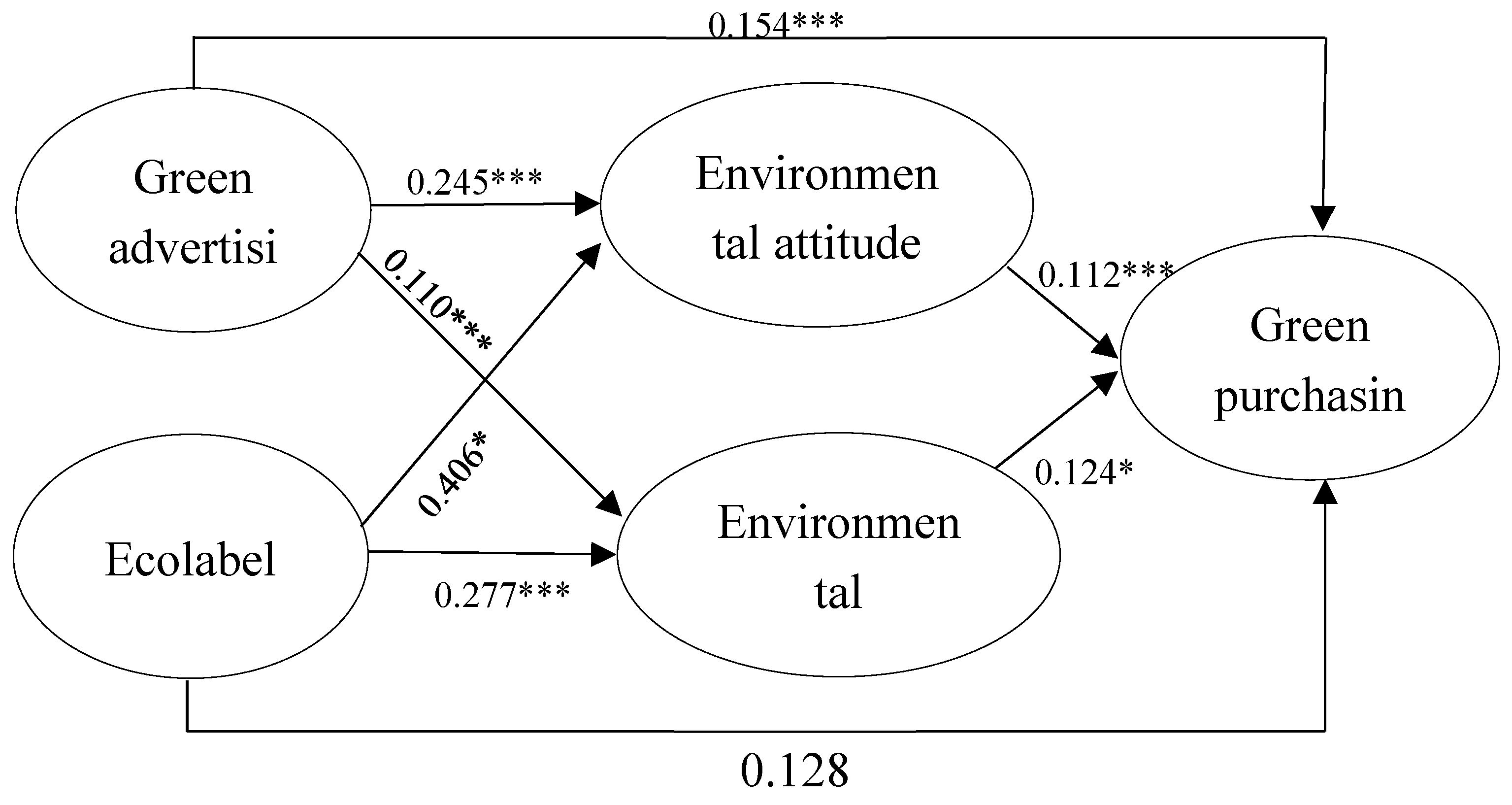

| Hypothesis | Relation | β | p- values | Hypothesis |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | EAT-GPB | 0.112 | *** | Accepted |

| H2 | EAW-GPB | 0.124 | 0.039* | Accepted |

| H3 | GAD-EAT | 0.245 | *** | Accepted |

| H4 | GAD-EAW | 0.110 | *** | Accepted |

| H5 | GAD-GPB | 0.154 | *** | Accepted |

| H6 | ECL-EAT | 0.406 | 0.010* | Accepted |

| H7 | ECL-EAW | 0.277 | *** | Accepted |

| H8 | ECL-GPB | 0.128 | 0.190 | Rejected |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).