Submitted:

05 February 2024

Posted:

06 February 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Numerical modelling and verification

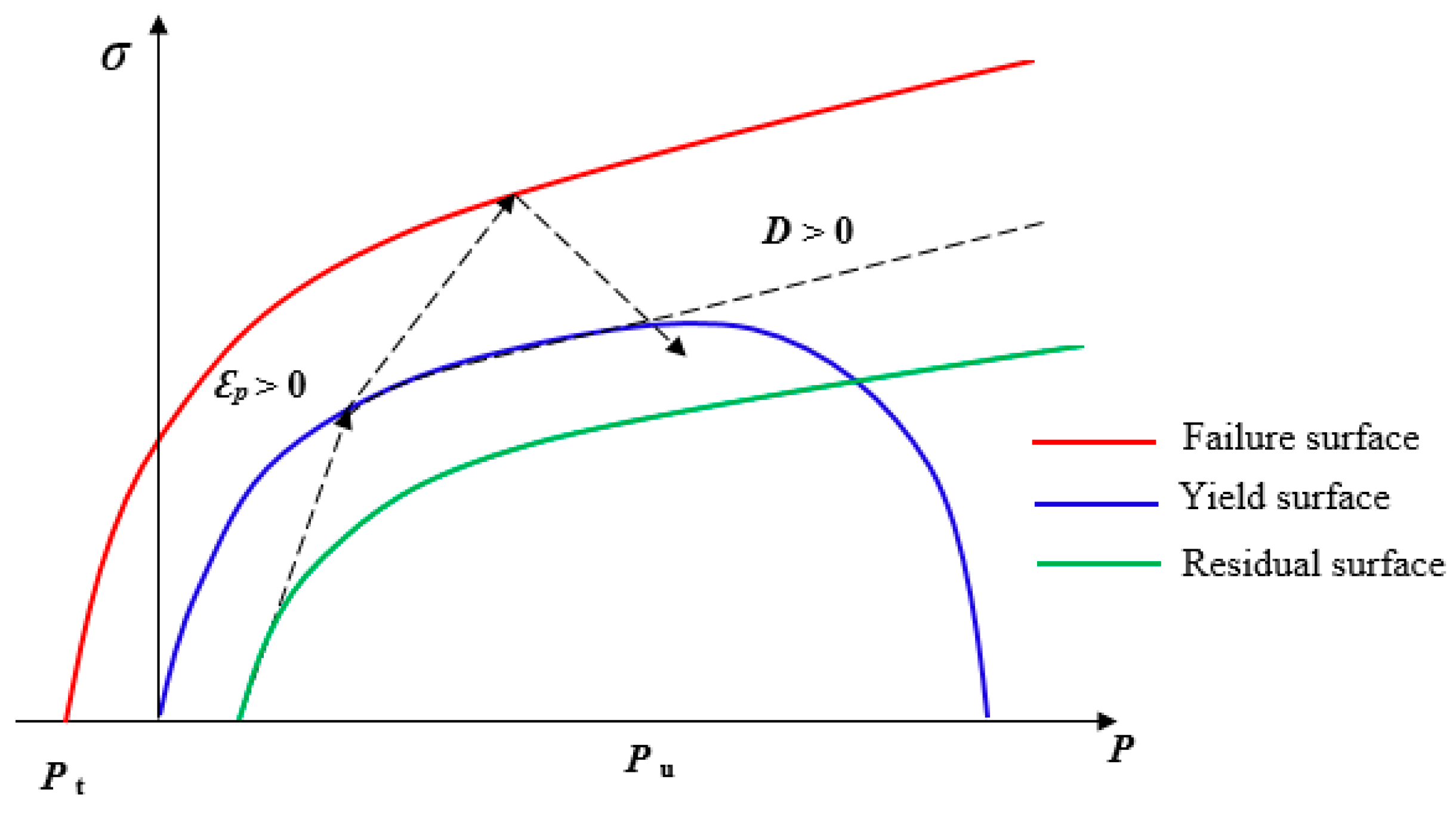

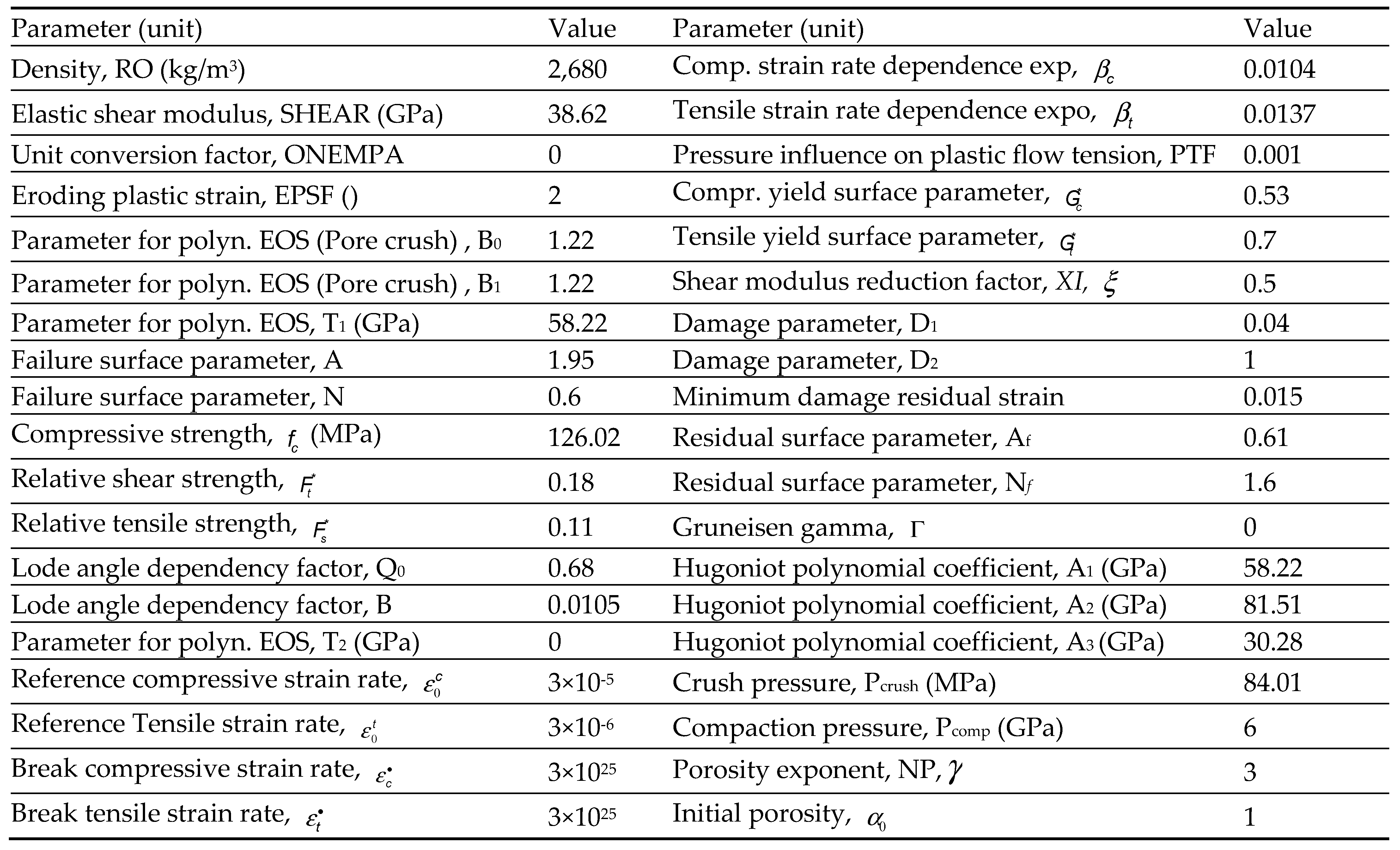

2.1. The RHT Material Model

is the accumulated plastic strain and

is the accumulated plastic strain and  the plastic strain failure. D varies from 0 to 1; 0 represents undisturbed material and 1 is a fully damaged material. More information about the RHT model can be found in Borrvall and Riedel (22)

the plastic strain failure. D varies from 0 to 1; 0 represents undisturbed material and 1 is a fully damaged material. More information about the RHT model can be found in Borrvall and Riedel (22)

are insensitive to simulation results and were taken from the reference values suggested by Borrvall and Riedel (22)

are insensitive to simulation results and were taken from the reference values suggested by Borrvall and Riedel (22)2.2. Explosive Properties and Parameters

| Explosive property (units) | Density (g/cm3) | Minimum diameter (mm) | VOD (km/s) | Relative Effective Energy (REE), (%) |

| Value | 1.10–1.25 | 64 | 4.1–6.7 | 151–189 |

| Explosive Type | Density (kg/m3) | VOD (m/s) | Pcj (GPa) |

A (GPa) |

B (GPa) |

R1 | R2 | ꞷ | Eo (kJ/cm3) | vo |

| E682/FortisE | 1,207 | 4,789 | 6.926 | 276.2 | 8.44 | 5.2 | 2.1 | 0.5 | 3.87 | 0 |

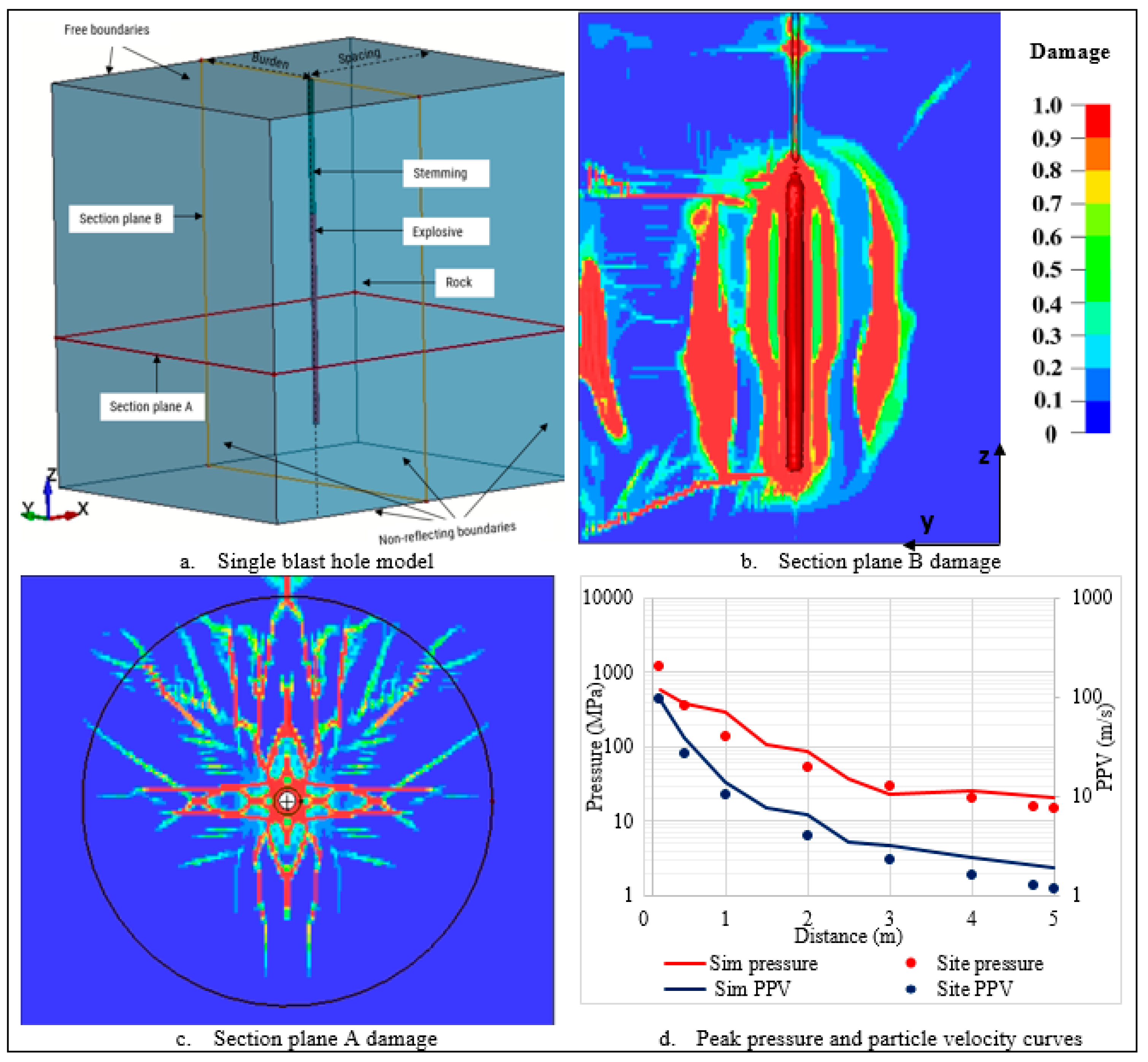

2.3. Simulation Model Preparation, Verification, and Validation

| Approach | rc (m) | Pe (MPa) | ue(m/s) | rf (m) | Pf (Mpa) | uf (m/s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study approach | 0.169 | 1,543.27 | 74.23 | 5.25 | 14.69 | 1.25 |

| SWT | 0.194 | 1,260.88 | 98.24 | 4.75 | 15.85 | 1.23 |

| HEL | 0.173 | 1,473.89 | 114.84 | - | - | - |

| Numerical modelling | 0.182 | 1,280.00 | 95.2 | 5.00 | 15.97 | 1.9 |

| Far-field monitoring | 0.169 | 592.82 | 50.63 | 5.25 | 13.82 | 1.25 |

| Standard error | 0.01 | 70.30 | 8.34 | 0.11 | 0.46 | 0.15 |

3. Factors Influencing Damage/Fragmentation in Single Blast Holes

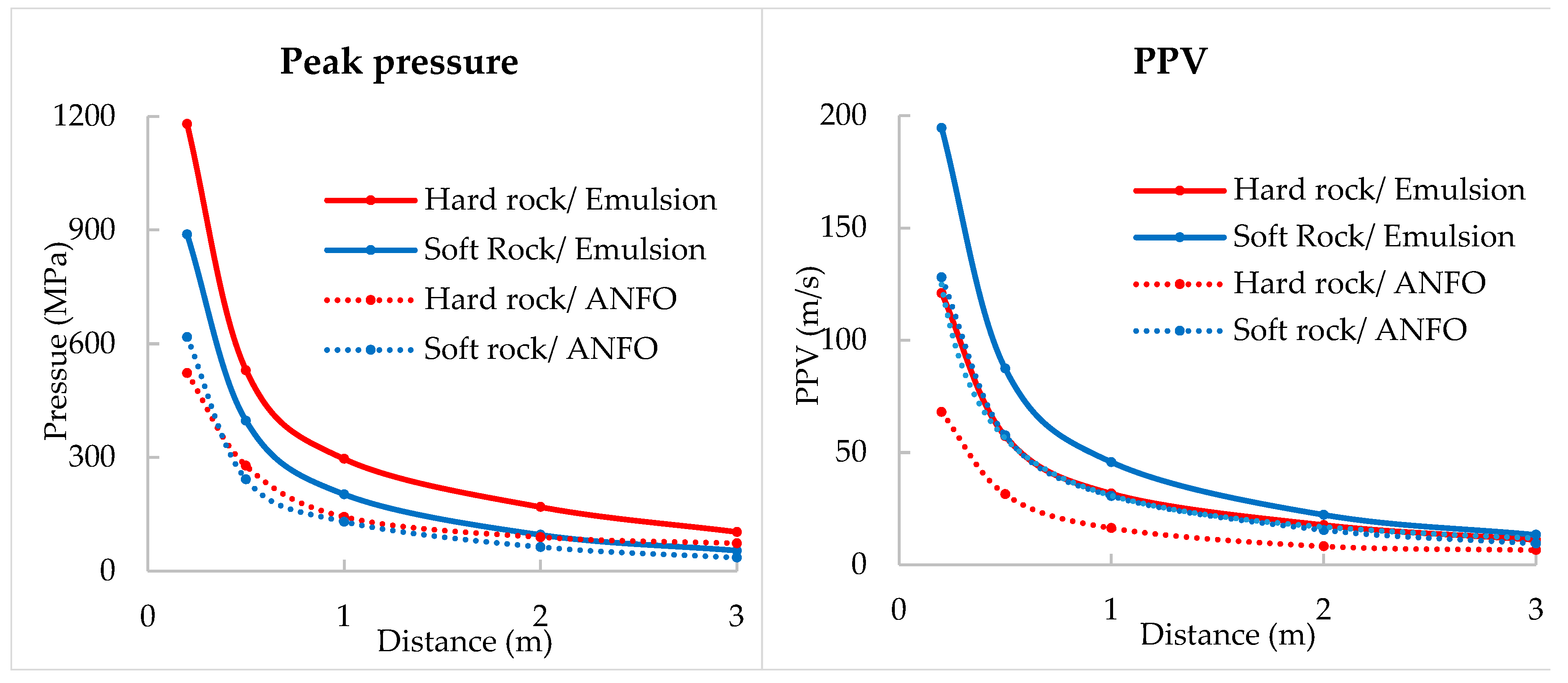

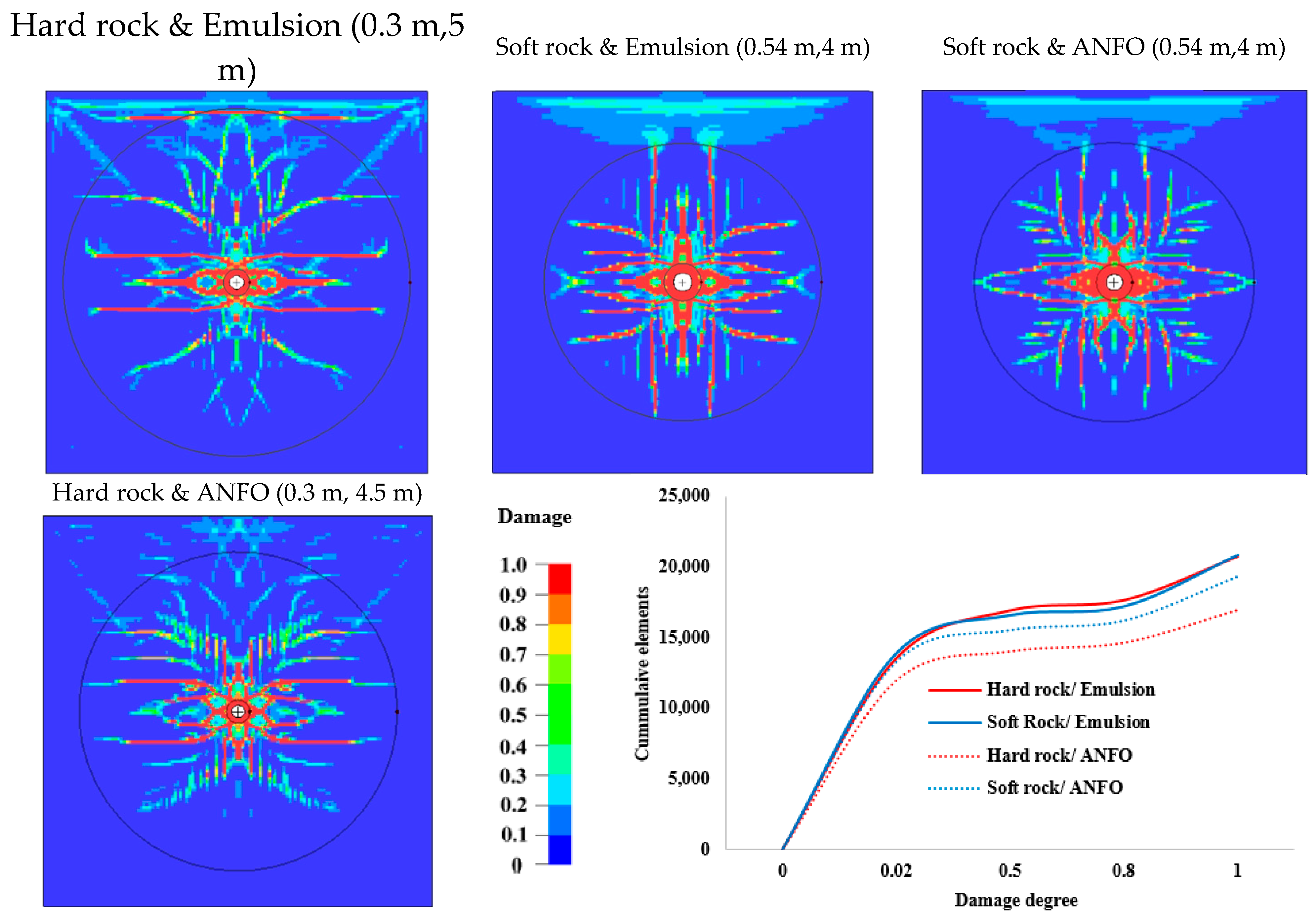

3.1. Variable Explosive and Rock Properties

| Explosive Type | Density (kg/m3) | VOD (m/s) | Pcj(GPa) | A (GPa) | B (GPa) | R1 | R2 | ꞷ | Eo (GPa) | vo |

| ANFO | 902 | 4426 | 4.503 | 207.79 | 2.91 | 5.91 | 1.08 | 0.4 | 2.29 | 0 |

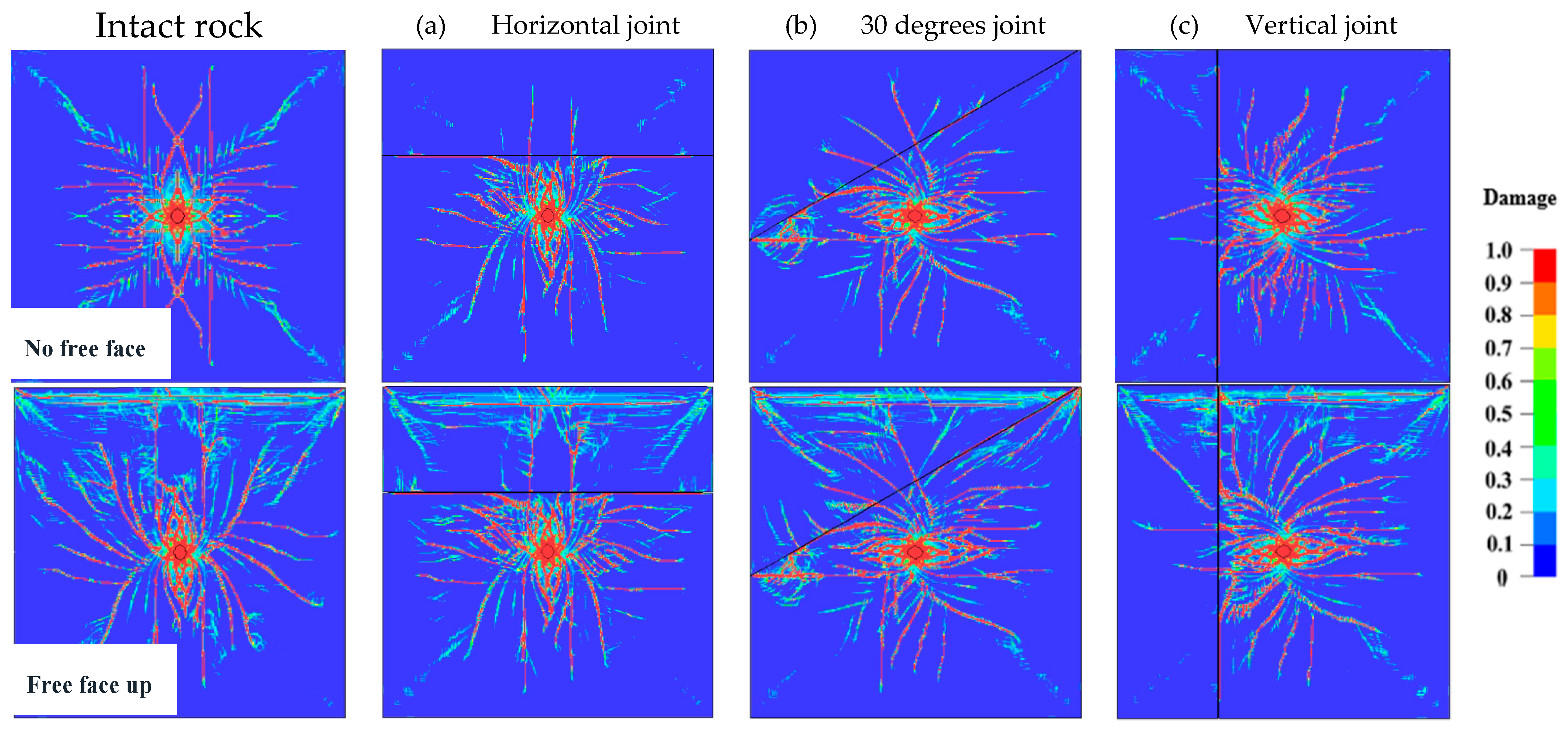

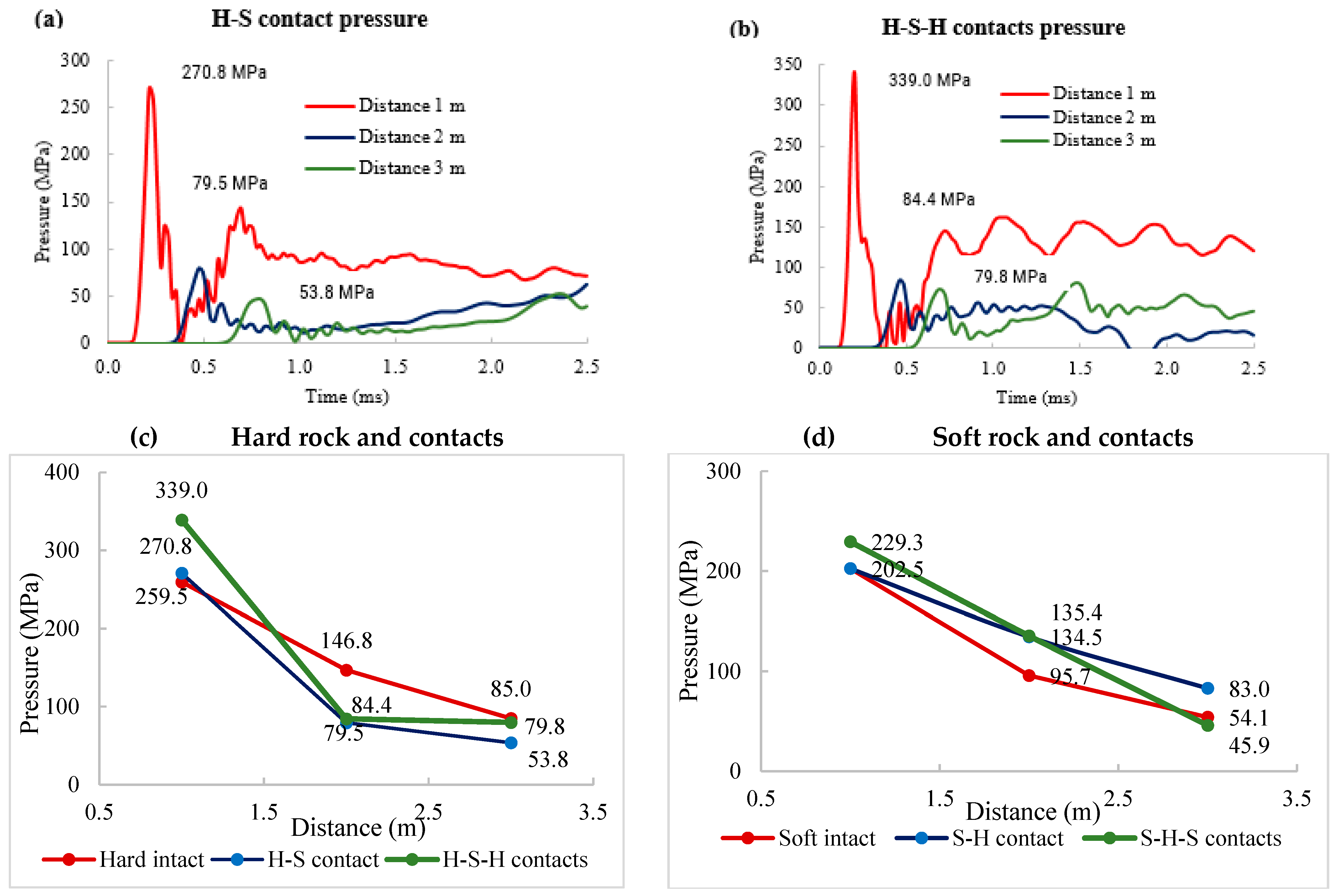

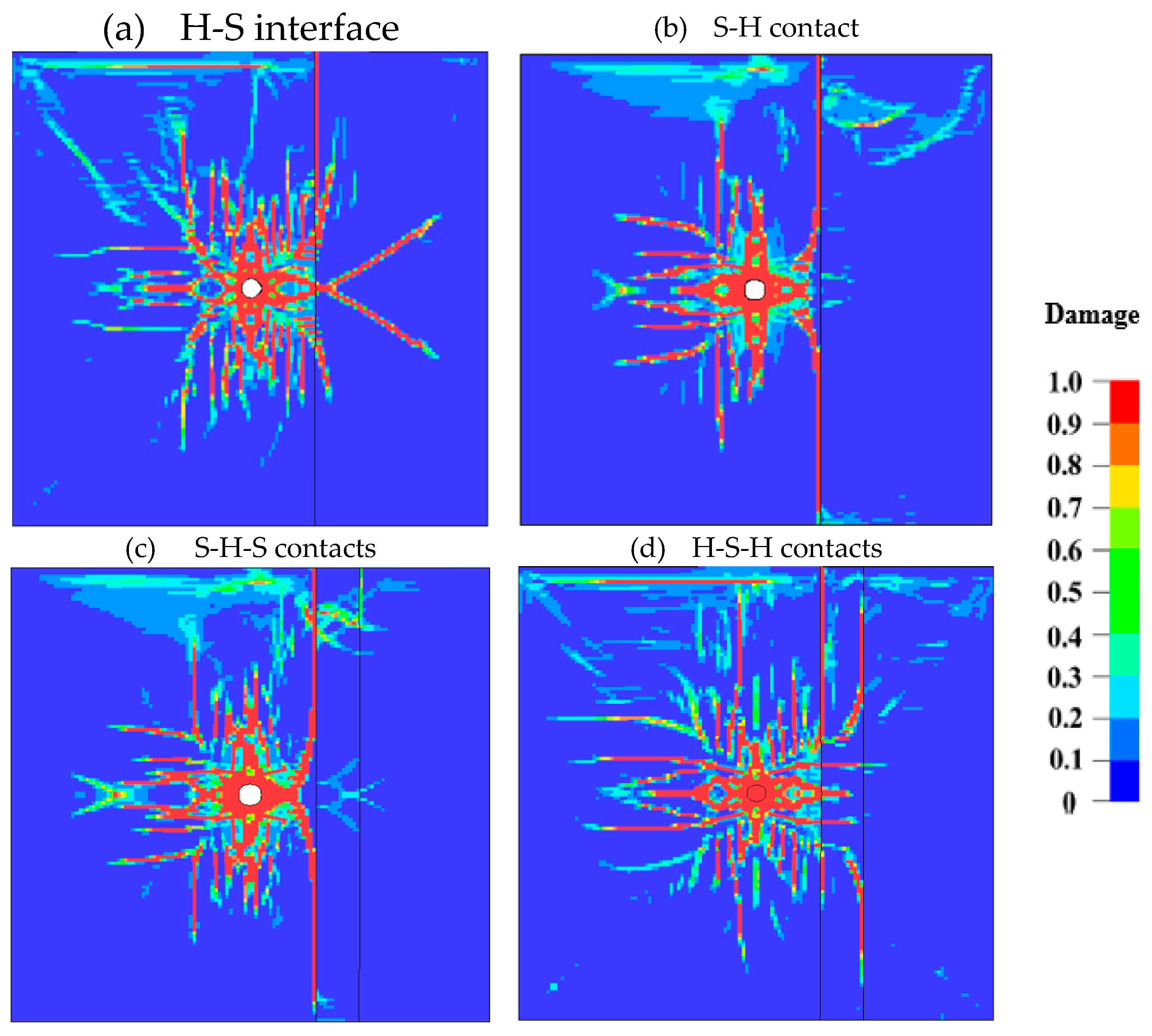

3.2. Influence of Rock Contacts on Fracture Distribution

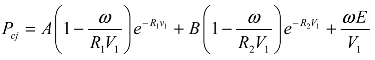

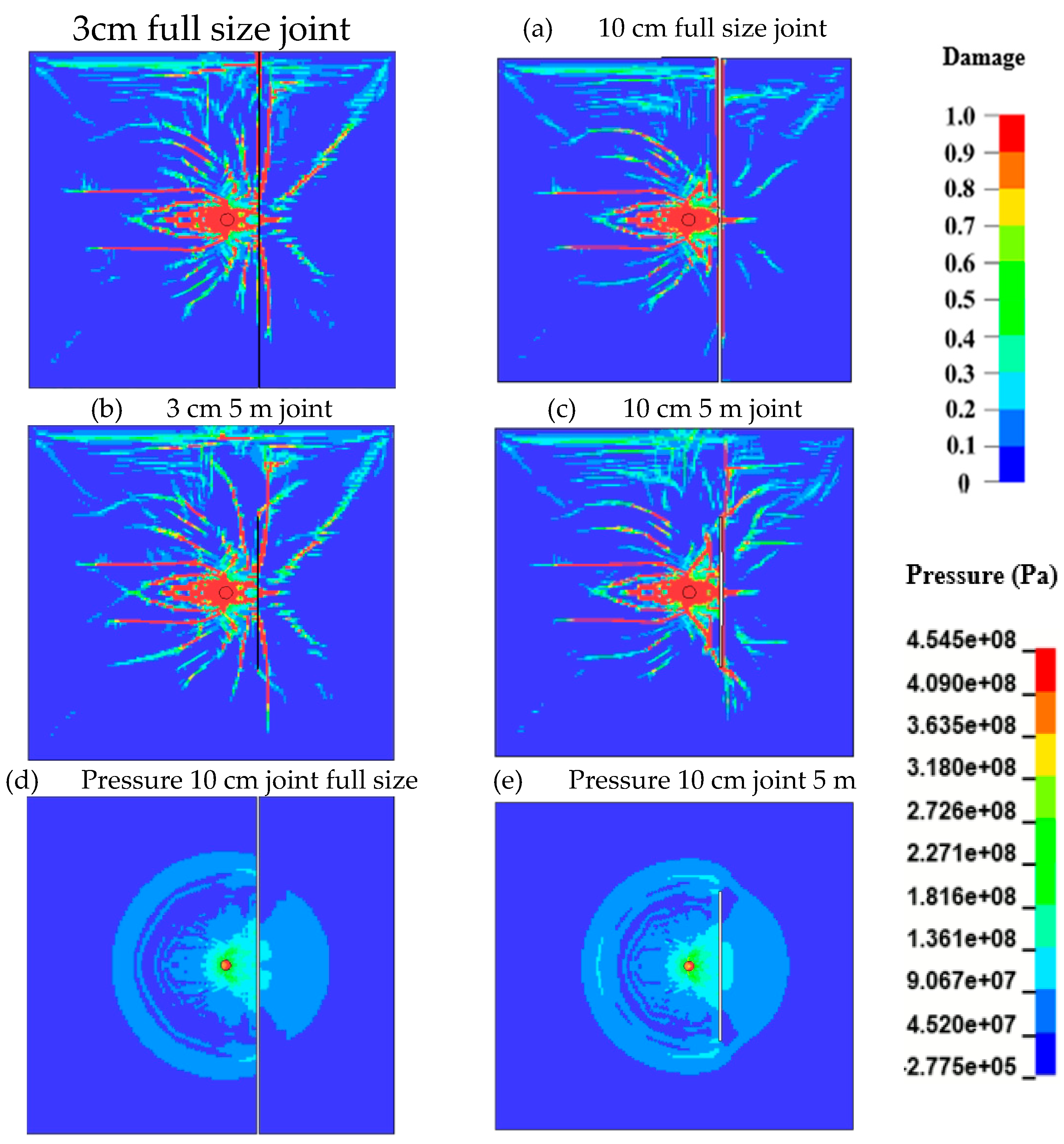

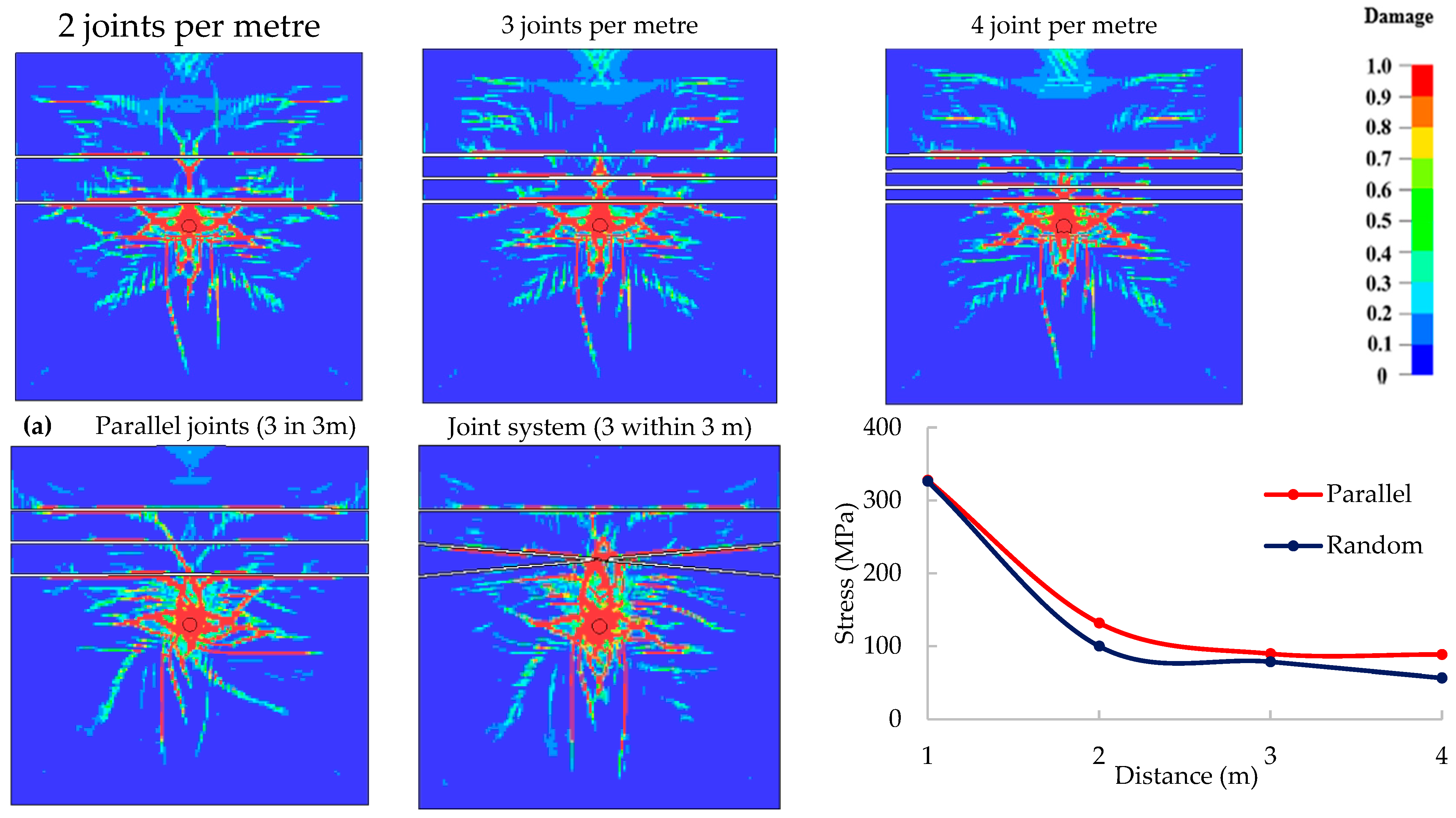

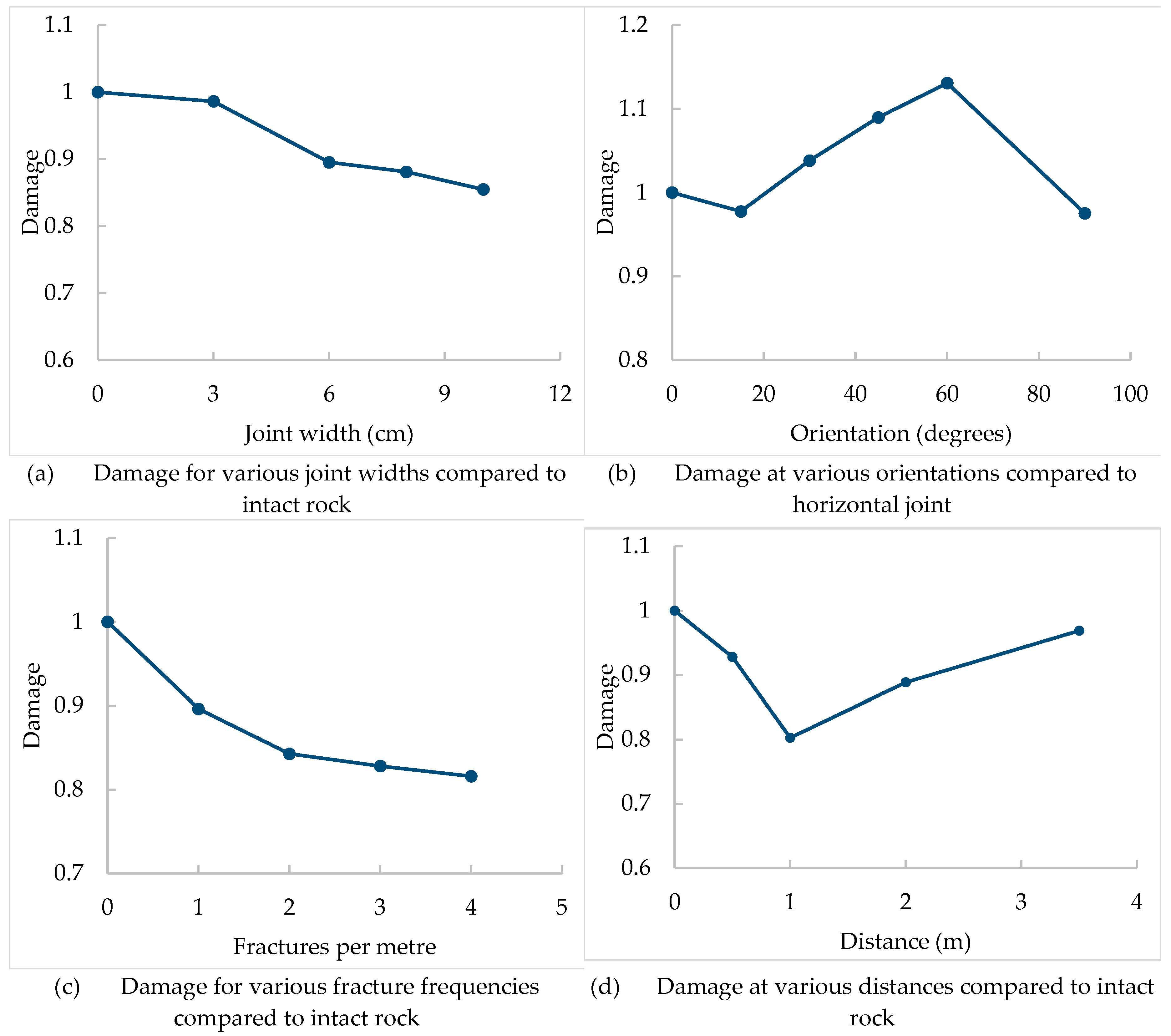

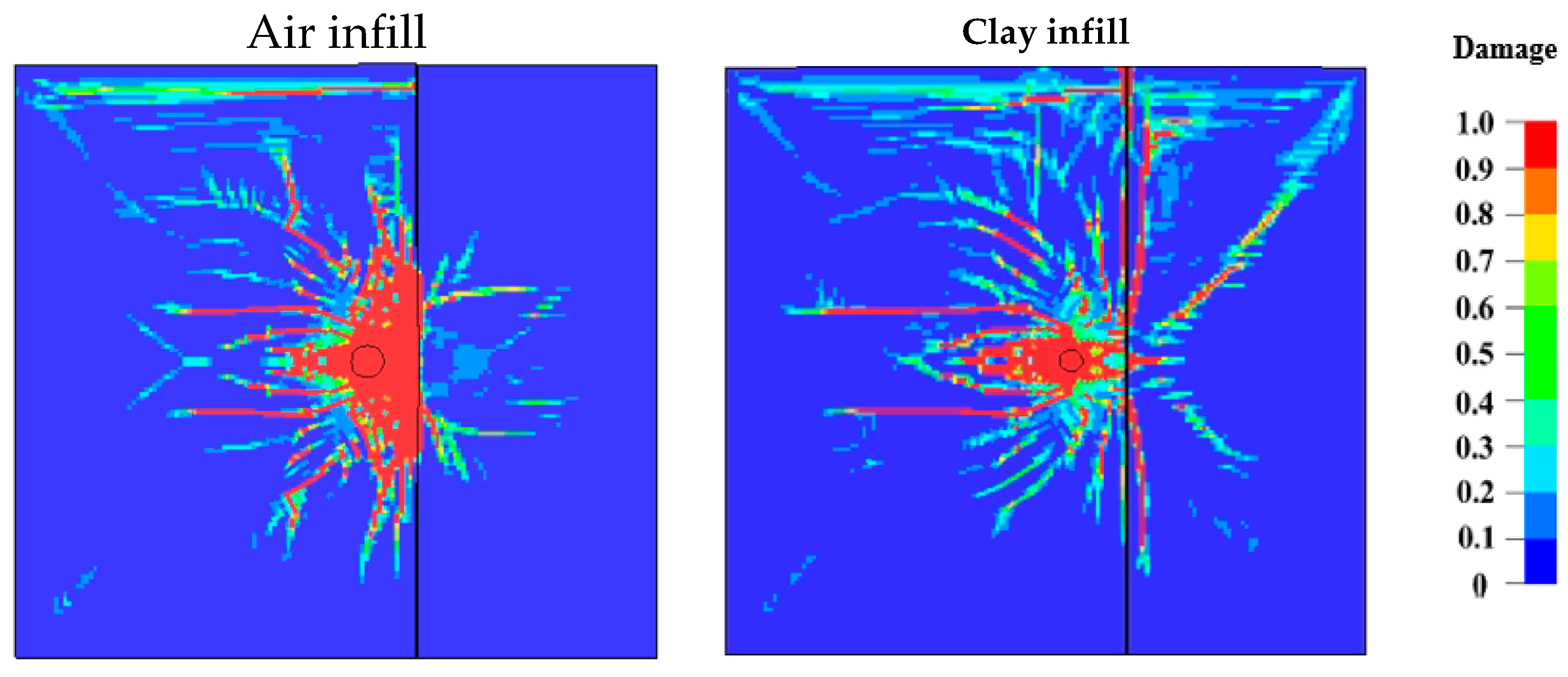

3.3. Joint Parameters and Their Influence on Blast Damage

4. Summary and Verification

4.1. Analysis Summary

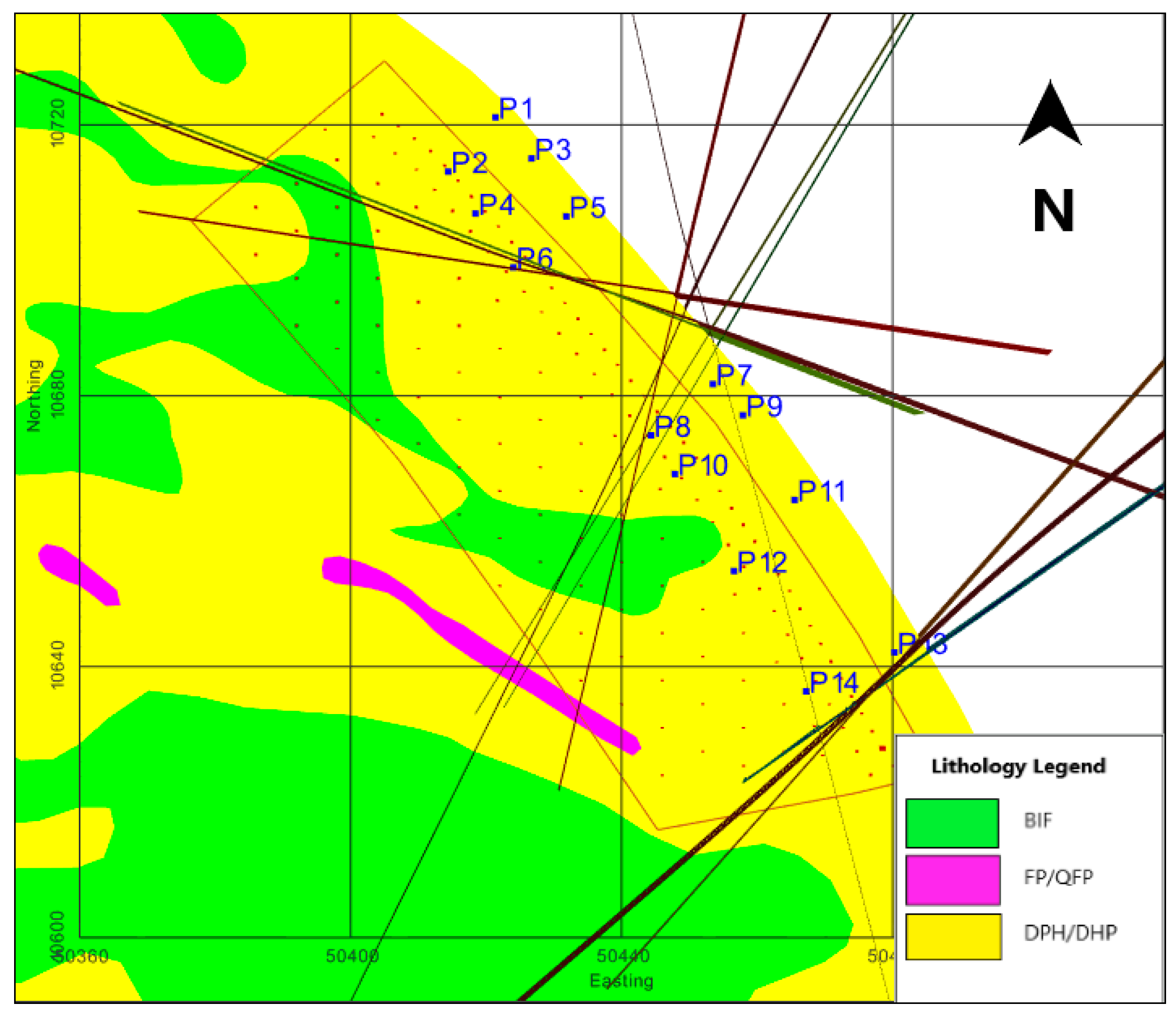

4.2. The Field Analysis and Model Validation

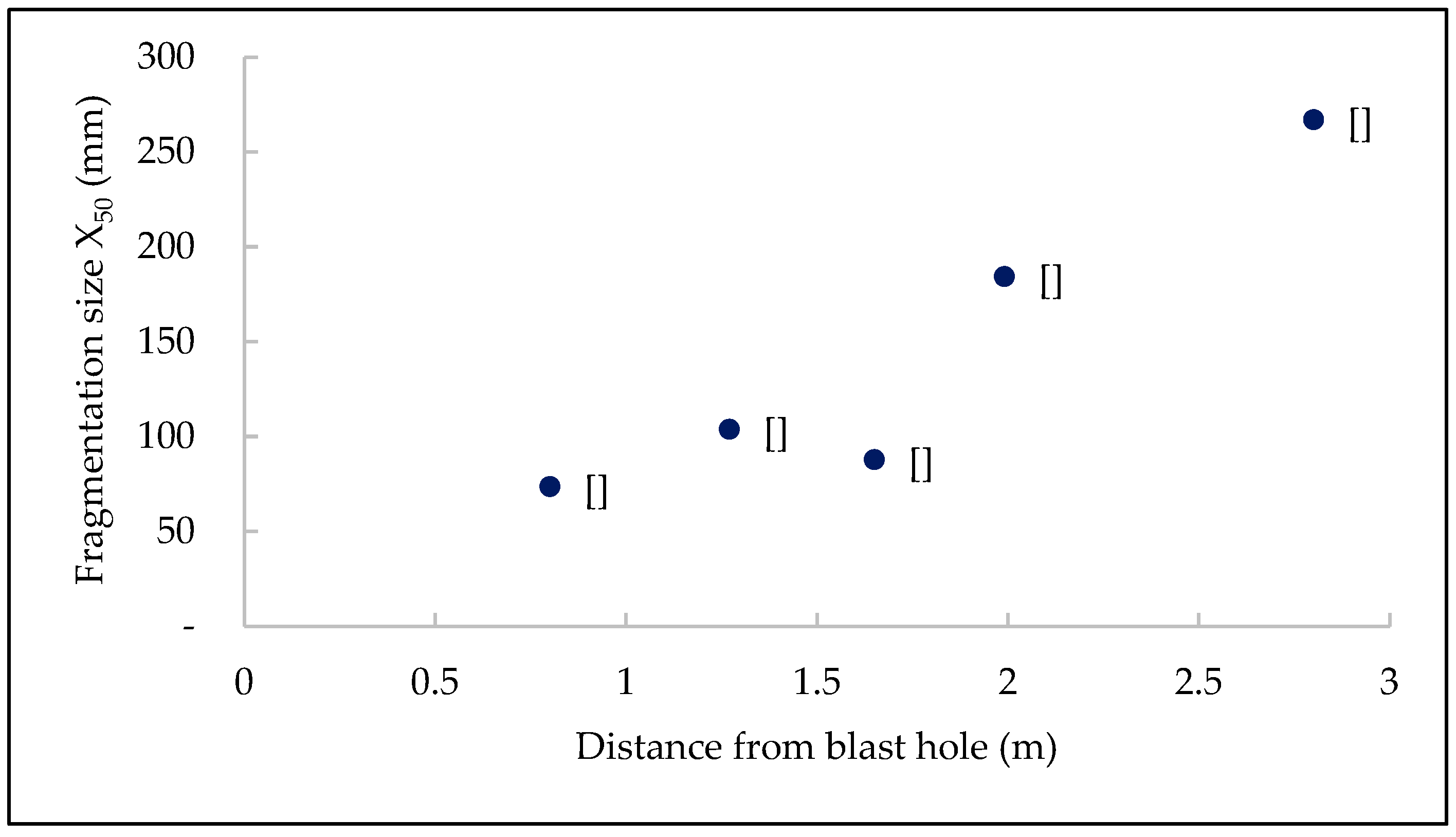

| Muckpile Point | Distance from BH, (m) | Intact rock size (B50), (m) | Charge (kg) | SD (m/kg0.5) |

PPV (m/s) |

Average frag. (X50) | BRF (B50/X50) |

| P2 | 2.48 | 1.04 | 73.24 | 0.29 | 1.37 | 129.14 | 8.09 |

| P4 | 2.17 | 1.68 | 73.24 | 0.25 | 1.58 | 237.42 | 7.07 |

| P8 | 0.8 | 0.67 | 210 | 0.06 | 8.25 | 73.67 | 9.12 |

| P6 | 2.8 | 2.38 | 210 | 0.19 | 2.12 | 267.09 | 8.89 |

| P10 | 1.27 | 2.26 | 210 | 0.09 | 5.00 | 103.97 | 21.72 |

| P12 | 1.65 | 1.42 | 210 | 0.11 | 3.76 | 87.98 | 16.16 |

| P14 | 1.99 | 1.30 | 210 | 0.14 | 3.07 | 184.40 | 7.07 |

5. Conclusions

- The RHT model can be used to describe the blast process and evaluate the impact of variable input parameters.

- The choice of explosive for the rock type greatly influences the blast outcomes. From the analysis, the strong explosives offer longer extended fractures while the less strong explosive (ANFO) has a better fracture distribution. With soft rock, the extent of fractures does not increase with stronger explosives; instead, it increases the damage intensity within the same boundaries. Using a weaker explosive on harder rock reduces the extent of fractures.

- The analysis of the structural properties shows the similarity in the behavior of the stress wave and crack propagation at the interface due to the impedance difference of materials, the intensity, and the direction of the wave. When the stress wave travels from the hard to soft rock, it is enhanced and attenuated when it travels in the opposite direction, similar to the cracks. The same is expected with multiple interfaces, although the outcomes may vary depending on the thickness of rock layers.

- The joints influence the stress wave and fracture propagation differently depending on the properties of the infill material, the width and continuity of the joints, the distance from the charge, the number of joints in a burden distance, and their orientations. Regardless of the case, the stress wave on the opposite side of the joint needs to be higher than the rock strength to guarantee fracturing; this includes the wave reflected at the free face.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhu Z, Mohanty B, Xie H. (2007). Numerical investigation of blasting-induced crack initiation and propagation in rocks. International Journal of Rock Mechanics and Mining Sciences, 44(3), 412-24. [CrossRef]

- Hustrulid WA. Blasting Principles for Open Pit Mining: CRC Press; 1999.

- Dehghan Banadaki MM, Mohanty B. (2012). Numerical simulation of stress wave induced fractures in rock. International Journal of Impact Engineering, 40-41, 16-25. [CrossRef]

- Esen S, Onederra I, Bilgin HA. (2003). Modelling the size of the crushed zone around a blasthole. International Journal of Rock Mechanics and Mining Sciences, 40(4), 485-95. 4. [CrossRef]

- Ding X, Yang Y, Zhou W, An W, Li J, Ebelia M. (2022). The law of blast stress wave propagation and fracture development in soft and hard composite rock. Scientific Reports, 12(1), 17120. [CrossRef]

- Shadabfar M, Gokdemir C, Zhou M, Kordestani H, Muho EV. (2021). Estimation of Damage Induced by Single-Hole Rock Blasting: A Review on Analytical, Numerical, and Experimental Solutions. Energies, 14(1), 29. [CrossRef]

- Zhang ZX. Rock Fracture and Blasting: Theory and Applications Amsterdam: Elsevier; 2016.

- Dotto MS, Pourrahimian Y, Joseph T, Apel D. (2022). Assessment of blast energy usage and induced rock damage in hard rock surface mines. CIM Journal, 13(4), 166-80. [CrossRef]

- Chen SG, Zhao J. (1998). A study of UDEC modelling for blast wave propagation in jointed rock masses. International Journal of Rock Mechanics and Mining Sciences, 35(1), 93-9. [CrossRef]

- Ismail MA, Gozon JS. (1987). Effects of discontinuities on fragmentation by blasting. International Journal of Surface Mining, Reclamation and Environment, 1(1), 21-5. [CrossRef]

- Wang Z, Huang Y, Xiong F. (2019). Three-Dimensional Numerical Analysis of Blast-Induced Damage Characteristics of the Intact and Jointed Rockmass. Computers, Materials \& Continua, 60(3), 1189 -206.

- Yang R, Ding C, Yang L, Chen C. (2018). Model experiment on dynamic behavior of jointed rock mass under blasting at high-stress conditions. Tunnelling and Underground Space Technology, 74, 145-52. [CrossRef]

- Jiang X, Xue Y, Kong F, Gong H, Fu Y, Zhang W. (2023). Dynamic responses and damage mechanism of rock with discontinuity subjected to confining stresses and blasting loads. International Journal of Impact Engineering, 172, 104404. [CrossRef]

- Chen C, Yang R, Xu P, Ding C. (2022). Experimental study on the interaction between oblique incident blast stress wave and static crack by dynamic photoelasticity. Optics and Lasers in Engineering, 148, 106764. [CrossRef]

- Xu P, Yang R-s, Guo Y, Chen C, Kang Y. (2021). Investigation of the effect of the blast waves on the opposite propagating crack. International Journal of Rock Mechanics and Mining Sciences, 144, 104818. [CrossRef]

- Zhu ZM. (2011). The Responses of Jointed Rock Mass under Dynamic Loads. Advanced Materials Research, 230-232, 251-5. [CrossRef]

- Amoako R, Jha A, Zhong S. (2022). Rock Fragmentation Prediction Using an Artificial Neural Network and Support Vector Regression Hybrid Approach. Mining, 2(2), 233-47. 2. [CrossRef]

- Torres VFN, Castro C, Valencia ME, Figueiredo JR, Silveira LGC. (2022). Numerical Modelling of Blasting Fragmentation Optimization in a Copper Mine. Mining, 2(4), 654-69. [CrossRef]

- Xie LX, Lu WB, Zhang QB, Jiang QH, Chen M, Zhao J. (2017). Analysis of damage mechanisms and optimization of cut blasting design under high in-situ stresses. Tunnelling and Underground Space Technology, 66, 19-33. [CrossRef]

- Wang J, Yin Y, Esmaieli K. (2018). Numerical simulations of rock blasting damage based on laboratory-scale experiments. Journal of Geophysics and Engineering, 15(6), 2399-417. [CrossRef]

- Riedel W, Thoma K, Hiermaier S, Schmolinske E, editors. Penetration of Reinforced Concrete by BETA-B-500 Numerical Analysis using a New Macroscopic Concrete Model for Hydrocodes. 9th international symposiumon interaction of the effects of munitions with structures; 1999; Berlin, Germany.

- Borrvall T, Riedel W, editors. The RHT concrete model in LS-DYNA. 8th European LS-DYNA users conference; 2011; Strasbourg, Austria.

- Livermore Software Technology Corporation L. LS-DYNA® Keyword User’s Manual R11 Volume II Material Models2018.

- Holmquist TJ, Johnson GR, Cook WH, editors. A Computational Constitutive Model for Concrete Subjected to Large Strains, High Strain Rates and High Pressures. 14th International symposium, Vol 2; Warhead mechanisms, terminal ballistics; 1993; Arlington, Quebec; Canada: ADPA;

- Wang Z, Wang H, Wang J, Tian N. (2021). Finite element analyses of constitutive models performance in the simulation of blast-induced rock cracks. Computers and Geotechnics, 135, 104172. [CrossRef]

- Lee EL, Hornig HC, Kury JW. Adiabatic Expansion Of High Explosive Detonation Products. United States; 1968. Contract No.: UCRL-50422.

- ORICA. (2018). Technical data sheet - Fortis Extra System - Africa.

- Hansson H. Determination of Properties for Emulsion Explosives Using Cylinder Expansion Tests and Numerical Simulation. Stockholm and Luleå, Sweden; 2009.

- Sanchidrián JA, Castedo R, López LM, Segarra P, Santos AP. (2015). Determination of the JWL Constants for ANFO and Emulsion Explosives from Cylinder Test Data. Central European Journal of Energetic Materials, 12, 177-94.

- Jeong H, Jeon S. (2018). Characteristic of size distribution rock chip produced by rock cutting with a pick cutter. Geomechanics and Engineering, 15. [CrossRef]

| Density (kg/m3) | UCS (MPa) | Tensile strength (MPa) | Young modulus (GPa) | Poisson ratio | P-wave velocity |

| 2400 | 88 | 0.1xUCS | 25 | 0.3 | 2589 |

| Density (kg/m3) | C4 | C5 | C6 | Eo (MPa) | Vo |

| 1.29 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0 | 0.5 | 1 |

| Density (kg/m3) | Young Modulus (GPa) | Poisson’s ratio | Yield stress, (MPa) | Tangent Modulus, (GPa) | Hardening parameter | Failure strain, FS |

| 1,160 | 5 | 0.35 | 0.4 | 4 | 0 | 0.5 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).