Submitted:

06 February 2024

Posted:

06 February 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Biological Basics

2.1. The Biology of Brassica Napus

2.2. The Biology of Camelina Sativa

2.3. The Biology of Thlaspi Arvense

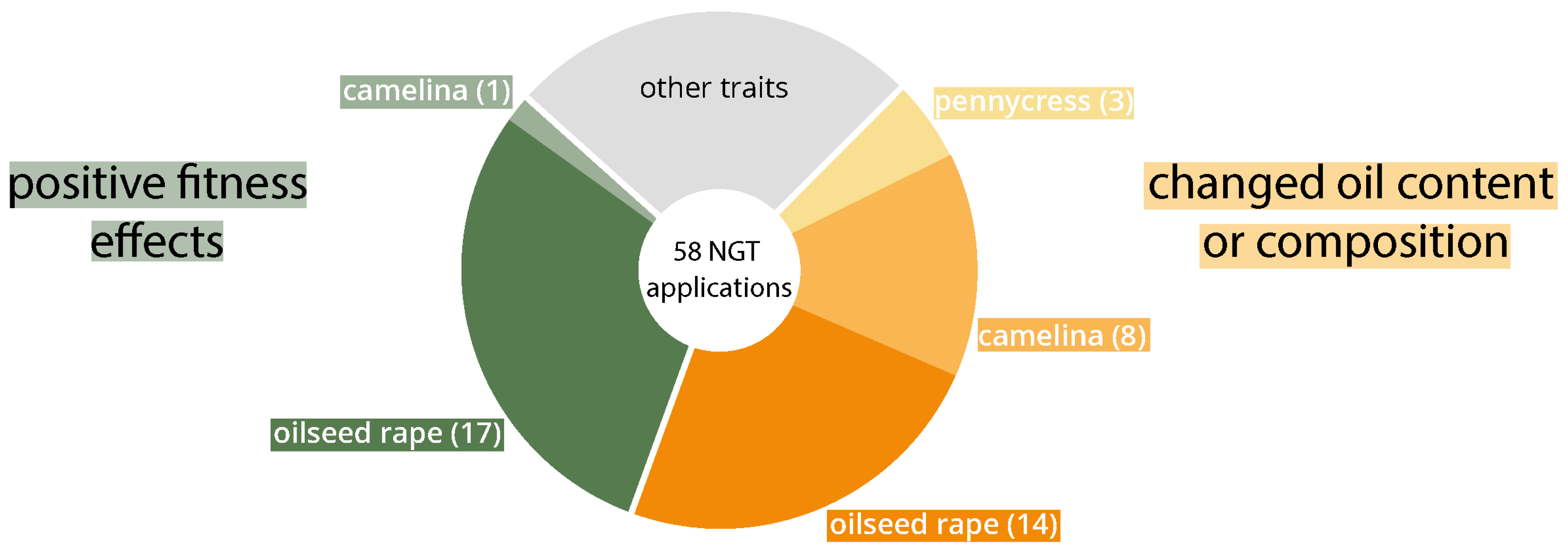

3. Overview of NGT Applications in Brassicaceae Oilseed Plants

3.1. Brassica napus (Oilseed Rape)

3.2. Camelina sativa (Camelina)

3.3. Thlaspi arvense (Pennycress)

3.4. Field Trials and Commercialisation Pipeline

4. Findings and Scenarios Relevant for Risk Assessment

4.1. Risks for Pollinators

4.1.1. Decreased Amounts of PUFA Can Negatively Affect the Health of Pollinators

4.1.2. Increasing Amounts of Oil and Unsaturated Fatty Acids Can Negatively Affect the Health of Pollinators

4.1.3. Further Observations Regarding Changes in Oil Composition

4.2. Persistence and Spread

- A broad range of Brassica species can hybridise with each other;

- Many Brassicaceae have weedy characteristics;

- Seeds can exhibit prolonged dormancy;

- Pollination by insects and wind, as well as dispersal, can occur over long distances.

4.3. Spontaneous Crossings and Stacking

5. Conclusions

Appendix A

| Field of Application | Edited Gene(s) | Trait Category | Trait | Reference |

| Abiotic stress tolerance | BnCUP1 (Cd uptake-related gene) | Cadmium tolerance | Reduced Cadmium (Cd) accumulation without a distinct compromise in yield, also for agricultural production in Cd-contaminated soils. | https://doi.org/10.3390/cells11233888 |

| Abiotic stress tolerance | CUP1 (Cd uptake-related) | Cadmium tolerance | Reducing Cd accumulation. Displayed superior growth and longer roots. | https://doi.org/10.3390/cells11233888 |

| Abiotic stress tolerance | BnPUB18 and BnPUB19 (Plant U-box) | Drought tolerance | Significant improvements to drought tolerance. | https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indcrop.2023.116875 |

| Abiotic stress tolerance. Harvesting processing | BraRGL1 (DELLA protein) | Changed flowering time. Changed plant architecture | Early maturing varieties. Promotes the flower bud differentiation without affecting the stalk quality. Improved breeding of early maturing varieties (bolting and flowering). | https://doi.org/10.1093/hr/uhad119 |

| Biotic stress tolerance | BnIDA (Inflorescence Deficient in Abscission) | Changed flowering time. Fungal resistance | Floral abscission-defective phenotype in which floral organs remained attached to developing siliques, and dry and colourless senesced floral parts remained attached to mature siliques. Enhanced resistance against Sclerotinia sclerotiorum (Sclerotinia stem rot (SSR)). Longer flowering period. | https://doi.org/10.1093/plphys/kiac364 |

| Biotic stress tolerance | WRKY70 (WRKY transcription factors) | Fungal resistance | Enhanced resistance to Sclerotinia sclerotiorum (Sclerotinia stem rot (SSR)). | https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms19092716 |

| Biotic stress tolerance | BnCRT1a (calreticulin) | Fungal resistance | Activation of the ethylene signalling pathway, which may contribute to reduced susceptibility towards Verticillium longisporum (Vl43). | https://doi.org/10.1111/pbi.13394 |

| Biotic stress tolerance. Harvest properties. Storage properties | BnF5H (Ferulate-5-hydroxylase gene) | Fungal resistance. Changed plant architecture. | Decreased S/G lignin compositional ratio (ratio of syringyl (S) and guaiacyl (G) units in lignin). Stem strength dependence on lignin composition / stem lodging. More tightly packed stem structure, probably leading to a lower stem lodging index. Improves Sclerotinia sclerotiorum resistance. | https://doi.org/10.1111/pce.14208 |

| Biotic stress tolerance. Yield | BnaIDA (inflorescence deficient in abscission) | Fungal resistance. Changed flowering time. | Reduced floral organ abscission, silique dehiscence (diverge), and disease severity caused by S. sclerotiorum. Improved yield by reducing seed loss due to premature silique dehiscence during mechanical harvesting and losses due to stem rot. Longer flowering period. | https://doi.org/10.1016/j.xplc.2022.100452 |

| Breeding processing | BnS6-Smi2 (S locus) | Avoiding self-fertilization | Self-incompatibility to prevent inbreeding in hermaphrodite angiosperms via the rejection of self-pollen. | https://doi.org/10.1111%2Fpbi.13577 |

| Breeding processing | BnaDMP (domain of unknown function 679 membrane protein) | Doubled haploid induction | Establishment of maternal haploid induction. | https://doi.org/10.1111/jipb.13244 |

| Breeding properties | BnaDMP (domain of unknown function 679 membrane protein) | Doubled haploid induction | Higher haploid induction rate. | https://doi.org/10.1111/jipb.13270 |

| Breeding properties | BnCYP704B1 (cytochrome P450) | Male sterility | Establishment of male sterility: pollenless, sterile phenotype in mature anthers. | https://doi.org/10.3390/plants12020365 |

| Breeding properties | BnARC1 (E3 ligaseARM-Repeat-Containing protein) | Enables self-fertilization | Complete breakdown of self-incompatibility response. Promoting outcrossing and genetic diversity. | https://doi.org/10.1016/j.xplc.2022.100504 |

| Food quality | BnaSAD2 | Changed fatty acid content | Higher stearic acid content. | https://doi.org/10.1007/s00122-023-04414-x |

| Food quality. Feed quality | BnITPK (inositol tetrakisphosphate kinase) | Changed protein value | Reduced phytic acid, increase of free phosphorus, increase in protein value and no adverse effects on oil contents. | https://doi.org/10.1111/pbi.13380 |

| Food quality. Feed quality. Industrial properties | BnFAD2 (fatty acid desaturase 2) | Changed fatty acid composition | Increased oleic acid content. | https://doi.org/10.1016/j.plaphy.2018.04.025 |

| Food quality. Feed quality. Industrial properties | BnTT8 (basic helix-loop-helix, bHLH) | Changed fatty acid composition | Modification of fatty acid composition, including increases in palmitic acid, linoleic acid and linolenic acid and decreases in stearic acid and oleic acid. | https://doi.org/10.1111/pbi.13281 |

| Food quality. Feed quality. Industrial properties | BnFAD2 (fatty acid dehydrogenase 2) | Changed fatty acid composition | Modification of fatty acid composition. The oleic acid content in the seed increased significantly, while linoleic and linolenic acid contents decreased accordingly. | https://doi.org/10.1007/s00122-020-03607-y |

| Food quality. Feed quality. Industrial properties | BnFAD2 (fatty acid desaturase 2) and BnFAE1 (fatty acid elongase1) | Changed fatty acid composition | Increased content of oleic acid, reduced erucic acid levels and slightly decreased polyunsaturated fatty acids content. | https://doi.org/10.3390/genes13101681 |

| Food quality. Feed quality. Industrial properties | KASII (canolaβ-ketoacyl-ACP synthase II) | Changed fatty acid composition. Changed oil content | Decreased palmitic acid content, increased total C18 and reduced total saturated fatty acid contents. | https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-7652.2012.00695.x |

| Food quality. Feed quality. Industrial properties | BnaTT7, BnaTT18, BnaTT10, BnaTT1, BnaTT2 or BnaTT12 (transparent testa) | Changed fatty acid composition. Changed oil content | Elevated seed oil content and decreased pigment and lignin accumulation. Decreased oleic acid and increased linoleic and linolenic acid contents. Down-regulation of key genes in flavonoid synthesis. | https://doi.org/10.1111/pbi.14197 |

| Food quality. Feed quality. Industrial properties | BnTT2 (transparent testa 2) | Changed fatty acid composition. Changed oil content | Reduced flavonoids and improved fatty acid composition with higher linoleic acid and linolenic acid. | https://dx.doi.org/10.1021/acs.jafc.0c01126 |

| Food quality. Feed quality. Industrial properties | BnaFAE1 (fatty acid elongase 1) | Changed fatty acid composition. Changed oil content | Deacreased erucic acid content. | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2022.848723 |

| Food quality. Feed quality. Industrial properties | BnCIPK9 (Calcineurin B-like (CBL)-interacting protein kinase 9) | Changed fatty acid composition. Changed oil content | Regulate seed oil metabolism. Increased levels of monounsaturated fatty acids and decreased levels of polyunsaturated fatty acids. | https://doi.org/10.1093/plphys/kiac569 |

| Food quality. Feed quality. Industrial properties | BnSFAR4 and BnSFAR5 (seed fatty acid reducer) | Changed oil content | Increased seed oil content without pleiotropic effects on seed germination, vigour and oil mobilization. Improving oil yield. | https://doi.org/10.1111/pbi.13381 |

| Food quality. Feed quality. Industrial properties | BnLPAT2 and BnLPAT5 (Lysophosphatidic acid acyltransferase) | Changed oil content | Increased seed oil content. | https://doi.org/10.1186/s13068-022-02182-2 |

| Food quality. Feed quality. Industrial properties | BnFAD2 (fatty acid desaturase 2) | Changed fatty acid composition. Changed oil content | Enhanced seed oleic acid content. | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2022.1034215 |

| Food quality. Feed quality. Industrial properties | BnKANT3, BnGIF1, BnAGP11 or BnEDA32 | Changed fatty acid composition. Changed oil content | Increased linoleic or linolenic acid content. | https://doi.org/content/33/5/798.full |

| Food quality. Feed quality. Industrial properties | BnaSBE (starch branching enzymes) | Changed plant architecture. Changed carbohydrate composition. | Higher starch-bound phosphate content and altered pattern of amylopectin length pattern. Thick main stem. | https://doi.org/10.1093/plphys/kiab535 |

| Harvest properties | BnaCOL9 (CONSTANS-like 9) | Changed flowering time | Early-maturing breeding. | https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms232314944 |

| Harvest properties | BnBRI1 (leucine-rich repeat receptor-like protein kinase) | Changed plant architecture | Semi-dwarf lines without decreased yield in order to increase harvest index. | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2022.865132 |

| Harvest properties. | BnJAG (jagged) | Changed plant architecture | Changes in pod dehiscence zone with potential to increase shatter resistance. | https://doi.org/10.3390/biom9110725 |

| Harvest properties. | BnIND (INDEHISCENT) | Changed plant architecture | Increased shatter resistance to avoid seed loss during mechanical harvest. | https://doi.org/10.1007/s00122-019-03341-0 |

| Harvest properties. Yield | BnALC (ALCATRAZ) | Changed plant architecture | Increased shatter resistance to avoid seed loss during mechanical harvest. | https://doi.org/10.1104/pp.17.00426 |

| Harvesting processing | BnaSVP (Short Vegetative Phase) | Changed flowering time | Early-flowering phenotypes. | https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cj.2021.03.023 |

| Seed quality | BnPAP2 (production of anthocyaninpigment 2) | Changed seed pigments | Yellow seed coat and reduced proanthocyanidins. Reduced expression of various flavonoid biosynthesis genes. | https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jia.2023.05.001 |

| Visual appearance | BnaCRTISO (carotenoid isomerase) | Changed ornamental plant properties | Altered colour of petals and leaves in order to improve the ornamental value of rapeseed and promote the development of agriculture and tourism. | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2022.801456 |

| Yield | BnaSDG8 (Methyltransferase SDG8) | Changed flowering time | Early-flowering varieties influenced by epigenetic modification. | https://doi.org/10.1111/tpj.13978 |

| Yield | BnCLV3 (CLAVATA3) | Changed plant architecture | Increased silique and seed number and higher seed weight. | https://doi.org/10.1111/pbi.12872 |

| Yield | BnaMAX1 (more axillary growth (max)) | Changed plant architecture | Increased branching phenotypes with more siliques in order to increased yield. | https://doi.org/10.1111/pbi.13228 |

| Yield | BnD14 (strigolactone receptor BnD14) | Changed plant architecture | Shoot architectural changes. Increase of total flowers. | https://doi.org/10.1111/pbi.13513 |

| Yield | BnaA03.BP (BREVIPEDICELLUS) | Changed plant architecture | Optimizing rapeseed plant architecture, semi-dwarf and compact architecture. | https://doi.org/10.1111/pbi.13703 |

| Yield | BnaEOD3 (ENHANCER OF DA1) | Changed plant architecture | Shorter siliques, smaler seeds, and an increased number of seeds per siliques. Increased seed weight per plant. | https://doi.org/10.1002/jcp.29986 |

| Yield | BnEOD1 (Enhancer of DA1) | Changed plant architecture | Increased seed size and weight. | https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-3204656/v1 |

| Field of Application | Edited Gene(s) | Trait Category | Trait | Reference |

| Food quality. Industrial properties | CsFAD2 (fatty acid desaturase 2) | Changed fatty acid composition. Changed oil content | Increased oleic acid content (proportional decrease in linoleic and linolenic acid content). | https://doi.org/10.1111/pbi.12671 |

| Food quality. Industrial properties | CsFAD2 (fatty acid desaturase 2) | Changed fatty acid composition | Increased oleic acid content (proportional decrease in linoleic and linolenic acid content). | https://doi.org/10.1111/pbi.12663 |

| Industrial properties | CsFAD2 (fatty acid desaturase 2) | Changed fatty acid composition | Enhanced monounsaturated fatty acid levels, partially bushy phenotype. | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2021.702930 |

| Food quality. Feed quality.Industrial properties | CsCRUC (cruciferin C) | Changed protein composition. Changed fatty acid composition | Changed seed amino acid content (increased proportion of alanine, cysteine and proline, and decrease of isoleucine, tyrosine and valine). Increased relative abundance of all saturated fatty acids. | https://doi.org/10.1186/s12870-019-1873-0 |

| Industrial properties | CsDGAT1 or CsPDAT1 (acyl-CoA:- or phospholipid:diacylglycerol acyltransferase) | Changed triacylglycerols content. Changed fatty acid composition. Changed oil content | Produce triacylglycerols (TAGs) that are valuable as industrial feedstocks. Reduced oil content, partially higher levels of linoleic acid. | https://doi.org/10.1093/pcp/pcx058 |

| Food quality | FAE1 (fatty acid elongase 1) | Changed fatty acid composition | Decreased erucic acid content, increased levels of omega-3 fatty acids such as linolenic acid as well as eicosapentaenoic and docosahexaenoic acid in transgenic camelina. | https://doi.org/10.1111/pbi.13876 |

| Food quality | FAE1 (fatty acid elongase 1) | Changed fatty acid composition | Increased oleic and linolenic acid content by blocking eicosenoic and erucic acid synthesis in transgenic camelina. | https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-34364-9 |

| Food quality | FAE1 (fatty acid elongase 1) | Changed fatty acid composition | Reduction of C20-C24 very long-chain fatty acids (VLCFAs). | https://doi.org/10.1016/j.plaphy.2017.11.021 |

| Yield | FLC (flowering locus C), SVP (short vegetative phase), LHP1 (like heterochromatin protein 1), TFL1 (terminal flower 1) and EFL3 (early flowering locus 3) | Changed flowering time | Early-flowering, shorter stature and/or basal branching. Different combinations of mutations had a positive or negative impact on yield. | https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy12081873 |

| Food quality. Feed quality | CsGTR1 and CsGTR2 (glucosinolate transporter) | Changed glucosinolate content | Decreased and eliminated glucosinolate content in order to improve quality of oil and press cake. | https://doi.org/10.1111/pbi.13936 |

| Field of Application | Edited Gene | Trait Category | Trait | Reference |

| Food quality. Feed quality. Industrial properties | FAD2 (fatty acid desaturase 2), ROD1 (reduced oleate desaturation 1) and FAE1 (fatty acid elongation 1) | Changed fatty acid composition. Changed oil content. | Increased oleic acid amount in seed oil. Reduction of PUFAs. | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2021.652319 |

| Food quality | FAE1 (fatty acid elongation 1) | Changed fatty acid composition. | Abolishing erucic acid production and creating an edible seed oil comparable to that of canola. | https://doi.org/10.1111/pbi.13014 |

| Industrial properties | FAE1-3 (fatty acid elongation) | Changed fatty acid composition. | Abolishing erucic acid production, further crossing with transgenic pennycress. | https://doi.org/10.3389/fenrg.2021.620118 |

References

- Ababouch, L., Chaibi, A., and Busta, F. F. (1992). Inhibition of Bacterial Spore Growth by Fatty Acids and Their Sodium Salts. J Food Prot 55, 980–984. [CrossRef]

- Abedi, E., and Sahari, M. A. (2014). Long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acid sources and evaluation of their nutritional and functional properties. Food Sci Nutr 2, 443–463. [CrossRef]

- Abramovic, H., and Abram, V. (2005). Physico-Chemical Properties, Composition and Oxidative Stability of Camelina sativa Oil.

- Aguirre, L., Hendelman, A., Hutton, S. F., McCandlish, D. M., and Lippman, Z. B. (2023). Idiosyncratic and dose-dependent epistasis drives variation in tomato fruit size. Science 382, 315–320. [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, N., Fatima, S., Mehmood, M. A., Zaman, Q. U., Atif, R. M., Zhou, W., et al. (2023). Targeted genome editing in polyploids: lessons from Brassica. Frontiers in Plant Science 14. Available at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpls.2023.1152468 (Accessed June 27, 2023).

- An, H., Qi, X., Gaynor, M. L., Hao, Y., Gebken, S. C., Mabry, M. E., et al. (2019). Transcriptome and organellar sequencing highlights the complex origin and diversification of allotetraploid Brassica napus. Nat Commun 10, 2878. [CrossRef]

- ANSES (2023). AVIS de l’Anses relatif à l’analyse scientifique de l’annexe I de la proposition de règlement de la Commission européenne du 5 juillet 2023 relative aux nouvelles techniques génomiques (NTG) – Examen des critères d’équivalence proposés pour définir les plantes NTG de catégorie 1. Anses - Agence nationale de sécurité sanitaire de l’alimentation, de l’environnement et du travail. Available at: https://www.anses.fr/fr/content/avis-2023-auto-0189 (Accessed February 2, 2024).

- Aono, M., Wakiyama, S., Nagatsu, M., Nakajima, N., Tamaoki, M., Kubo, A., et al. (2006). Detection of feral transgenic oilseed rape with multiple-herbicide resistance in Japan. Environ Biosafety Res 5, 77–87. https://doi.org/10.1051/ebr:2006017. [CrossRef]

- Arien, Y., Dag, A., Yona, S., Tietel, Z., Lapidot Cohen, T., and Shafir, S. (2020). Effect of diet lipids and omega-6:3 ratio on honey bee brood development, adult survival and body composition. Journal of Insect Physiology 124, 104074. [CrossRef]

- Arien, Y., Dag, A., Zarchin, S., Masci, T., and Shafir, S. (2015). Omega-3 deficiency impairs honey bee learning. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 112, 15761–15766. [CrossRef]

- Banks, G. (2014). Feral Oilseed Rape Populations within a Scottish Landscape: Implications for GM coexistence and environmental risk assessment.

- Bauer-Panskus, A., Miyazaki, J., Kawall, K., and Then, C. (2020). Risk assessment of genetically engineered plants that can persist and propagate in the environment. Environ Sci Eur 32, 32. [CrossRef]

- Becker, H. C., Damgaard, C., and Karlsson, B. (1992). Environmental variation for outcrossing rate in rapeseed (Brassica napus). Theoret. Appl. Genetics 84, 303–306. [CrossRef]

- Beckie, H. J., Warwick, S. I., Nair, H., and Séguin-Swartz, G. (2003). Gene Flow in Commercial Fields of Herbicide-Resistant Canola (brassica Napus). Ecological Applications 13, 1276–1294. [CrossRef]

- Bellec, Y., Guyon-Debast, A., François, T., Gissot, L., Biot, E., Nogué, F., et al. (2022). New Flowering and Architecture Traits Mediated by Multiplex CRISPR-Cas9 Gene Editing in Hexaploid Camelina sativa. Agronomy 12, 1873. [CrossRef]

- Belter, A. (2016). Long-Term Monitoring of Field Trial Sites with Genetically Modified Oilseed Rape (Brassica napus L.) in Saxony-Anhalt, Germany. Fifteen Years Persistence to Date but No Spatial Dispersion. Genes 7, 3. [CrossRef]

- Bohle, F., Schneider, R., Mundorf, J., Zühl, L., Simon, S., and Engelhard, M. (2023). Where Does the EU-Path on NGTs Lead Us? [CrossRef]

- Breckling, B., Middelhoff, U., Borgmann, P., Menzel, G., Brauner, R., Born, A., et al. (2003). “Biologische Risikoforschung zu gentechnisch veränderten Pflanzen in der Landwirtschaft: Das Beispiel Raps in Norddeutschland,” in, 19–45.

- Breed, M. D. (1998). Recognition Pheromones of the Honey Bee. BioScience 48, 463–470. [CrossRef]

- Brock, J. R., Ritchey, M. M., and Olsen, K. M. (2022). Molecular and archaeological evidence on the geographical origin of domestication for Camelina sativa. American Journal of Botany 109, 1177–1190. [CrossRef]

- CABI (2014). Thlaspi arvense (field pennycress) CABI Compendium. Available at: https://www.cabidigitallibrary.org/doi/full/10.1079/cabicompendium.27595 (Accessed January 25, 2024).

- CFIA, C. F. I. A. (2017). The Biology of Camelina sativa (L.) Crantz (Camelina). Available at: https://inspection.canada.ca/plant-varieties/plants-with-novel-traits/applicants/directive-94-08/biology-documents/camelina-sativa-l-/eng/1330971423348/1330971509470 (Accessed January 25, 2024).

- Chèvre, A. M., Ammitzbøll, H., Breckling, B., Dietz-Pfeilstetter, A., Eber, F., Fargue, A., et al. (2004). A review on interspecific gene flow from oilseed rape to wild relatives. Introgression from genetically modified plants into wild relatives, 235–251. [CrossRef]

- COGEM (2019). Genetically modified oilseed rape (Brassica napus). Available at: https://cogem.net/app/uploads/2019/07/130402-01-Advisory-report-Genetically-modified-oilseed-rape.pdf.

- Colombo, S. M., Campbell, L. G., Murphy, E. J., Martin, S. L., and Arts, M. T. (2018). Potential for novel production of omega-3 long-chain fatty acids by genetically engineered oilseed plants to alter terrestrial ecosystem dynamics. Agricultural Systems 164, 31–37. [CrossRef]

- Darmency, H. (1997). “Gene Flow between Crops and Weeds: Risk for New Herbicide Resistant Weeds ?,” in Weed and Crop Resistance to Herbicides, eds. R. De Prado, J. Jorrín, and L. García-Torres (Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands), 239–248. [CrossRef]

- Devos, Y., De Schrijver, A., and Reheul, D. (2009). Quantifying the introgressive hybridisation propensity between transgenic oilseed rape and its wild/weedy relatives. Environ Monit Assess 149, 303–322. [CrossRef]

- D’Hertefeldt, T., Jørgensen, R. B., and Pettersson, L. B. (2008). Long-term persistence of GM oilseed rape in the seedbank. Biology Letters 4, 314–317. [CrossRef]

- Eberle, C. A., Thom, M. D., Nemec, K. T., Forcella, F., Lundgren, J. G., Gesch, R. W., et al. (2015). Using pennycress, camelina, and canola cash cover crops to provision pollinators. Industrial Crops and Products 75, 20–25. [CrossRef]

- Eckerstorfer, M., and Heissenberger, A. (2023). Informationen zur Umweltpolitik: New Genetic Engineering - possible unintended effects. -, Eckerstorfer, Michael, Heissenberger, Andreas: New Genetic Engineering - possible unintended effects, -: Verlag Arbeiterkammer Wien -. 208. Available at: https://emedien.arbeiterkammer.at/viewer/toc/AC16982244/1/ (Accessed February 2, 2024).

- Ehrensing, D. T., and Guy, S. O. (2008). Camelina.

- Esfahanian, M., Nazarenus, T. J., Freund, M. M., McIntosh, G., Phippen, W. B., Phippen, M. E., et al. (2021). Generating Pennycress (Thlaspi arvense) Seed Triacylglycerols and Acetyl-Triacylglycerols Containing Medium-Chain Fatty Acids. Frontiers in Energy Research 9. Available at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fenrg.2021.620118 (Accessed February 2, 2024).

- Fan, S., Zhang, L., Tang, M., Cai, Y., Liu, J., Liu, H., et al. (2021). CRISPR/Cas9-targeted mutagenesis of the BnaA03.BP gene confers semi-dwarf and compact architecture to rapeseed (Brassica napus L.). Plant Biotechnology Journal 19, 2383–2385. [CrossRef]

- Feldlaufer, M. F., Knox, D. A., Lusby, W. R., and Shimanuki, H. (1993). Antimicrobial activity of fatty acids against Bacillus larvae, the causative agent of American foulbrood disease. Apidologie 24, 95–99. [CrossRef]

- FitzJohn, R. G., Armstrong, T. T., Newstrom-Lloyd, L. E., Wilton, A. D., and Cochrane, M. (2007). Hybridisation within Brassica and allied genera: evaluation of potential for transgene escape. Euphytica 158, 209–230. [CrossRef]

- Frieß, J. L., Breckling, B., Pascher, K., and Schröder, W. (2020). “Case Study 2: Oilseed Rape (Brassica napus L.),” in Gene Drives at Tipping Points: Precautionary Technology Assessment and Governance of New Approaches to Genetically Modify Animal and Plant Populations, eds. A. von Gleich and W. Schröder (Cham: Springer International Publishing), 103–145. [CrossRef]

- Galanty, A., Grudzińska, M., Paździora, W., and Paśko, P. (2023). Erucic Acid—Both Sides of the Story: A Concise Review on Its Beneficial and Toxic Properties. Molecules 28, 1924. [CrossRef]

- Gfeller, A., Dubugnon, L., Liechti, R., and Farmer, E. E. (2010). Jasmonate Biochemical Pathway. Science Signaling 3, cm3–cm3. [CrossRef]

- Glazebrook, J. (2005). Contrasting mechanisms of defense against biotrophic and necrotrophic pathogens. Annu Rev Phytopathol 43, 205–227. [CrossRef]

- Groeneveld, J. H., and Klein, A.-M. (2014). Pollination of two oil-producing plant species: Camelina (Camelina sativa L. Crantz) and pennycress (Thlaspi arvense L.) double-cropping in Germany. GCB Bioenergy 6, 242–251. [CrossRef]

- Gruber, S., Lutman, P., Squire, G., Roller, A., Albrecht, H., and Lecomte, J. (2007). Using the SIGMEA data base to provide an overview of the persistence of seeds of oilseed rape in the context of the coexistence of GM and conventional crops. Proc. 3rd Int. Conference on Co-Existence between GM and non-GM Based Agricultural Supply Chains (GMCC), 261–262.

- Gulden, R. H., Shirtliffe, S. J., and Thomas, A. G. (2003). Harvest losses of canola (Brassica napus) cause large seedbank inputs. Weed Science 51, 83–86. https://doi.org/10.1614/0043-1745(2003)051[0083:HLOCBN]2.0.CO;2.

- Havlickova, L., He, Z., Berger, M., Wang, L., Sandmann, G., Chew, Y. P., et al. (2023). Genomics of predictive radiation mutagenesis in oilseed rape: modifying seed oil composition. Plant Biotechnol J. [CrossRef]

- He, J., Zhang, K., Yan, S., Tang, M., Zhou, W., Yin, Y., et al. (2023). Genome-scale targeted mutagenesis in Brassica napus using a pooled CRISPR library. Genome Res. 33, 798–809. [CrossRef]

- Hixson, S. M., Shukla, K., Campbell, L. G., Hallett, R. H., Smith, S. M., Packer, L., et al. (2016). Long-Chain Omega-3 Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids Have Developmental Effects on the Crop Pest, the Cabbage White Butterfly Pieris rapae. PLOS ONE 11, e0152264. [CrossRef]

- Howe, G. A., and Jander, G. (2008). Plant Immunity to Insect Herbivores. Annu Rev Plant Biol 59, 41–66. [CrossRef]

- Hu, D., Jing, J., Snowdon, R. J., Mason, A. S., Shen, J., Meng, J., et al. (2021). Exploring the gene pool of Brassica napus by genomics-based approaches. Plant Biotechnology Journal 19, 1693–1712. [CrossRef]

- Huang, H., Ahmar, S., Samad, R. A., Qin, P., Yan, T., Zhao, Q., et al. (2023). A novel type of Brassica napus with higher stearic acid in seeds developed through genome editing of BnaSAD2 family. Theor Appl Genet 136, 187. [CrossRef]

- Huang, H., Cui, T., Zhang, L., Yang, Q., Yang, Y., Xie, K., et al. (2020). Modifications of fatty acid profile through targeted mutation at BnaFAD2 gene with CRISPR/Cas9-mediated gene editing in Brassica napus. Theor Appl Genet 133, 2401–2411. [CrossRef]

- Hulbert, A. J., Abbott, S. K., Hulbert, A. J., and Abbott, S. K. (2012). Nutritional ecology of essential fatty acids: an evolutionary perspective. Aust. J. Zool. 59, 369–379. [CrossRef]

- Iskandarov, U., Kim, H. J., and Cahoon, E. B. (2014). “Camelina: An Emerging Oilseed Platform for Advanced Biofuels and Bio-Based Materials,” in Plants and BioEnergy Advances in Plant Biology., eds. M. C. McCann, M. S. Buckeridge, and N. C. Carpita (New York, NY: Springer), 131–140. [CrossRef]

- Jarvis, B. A., Romsdahl, T. B., McGinn, M. G., Nazarenus, T. J., Cahoon, E. B., Chapman, K. D., et al. (2021). CRISPR/Cas9-Induced fad2 and rod1 Mutations Stacked With fae1 Confer High Oleic Acid Seed Oil in Pennycress (Thlaspi arvense L.). Frontiers in Plant Science 12. Available at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpls.2021.652319 (Accessed October 17, 2023).

- Jiang, W. Z., Henry, I. M., Lynagh, P. G., Comai, L., Cahoon, E. B., and Weeks, D. P. (2017). Significant enhancement of fatty acid composition in seeds of the allohexaploid, Camelina sativa, using CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing. Plant Biotechnol J 15, 648–657. [CrossRef]

- Jorgensen, R. B., and Andersen, B. (1994). Spontaneous Hybridization Between Oilseed Rape (Brassica napus) and Weedy B. campestris (Brassicaceae): A Risk of Growing Genetically Modified Oilseed Rape. American Journal of Botany 81, 1620–1626. [CrossRef]

- Julié-Galau, S., Bellec, Y., Faure, J.-D., and Tepfer, M. (2014). Evaluation of the potential for interspecific hybridization between Camelina sativa and related wild Brassicaceae in anticipation of field trials of GM camelina. Transgenic Res 23, 67–74. [CrossRef]

- Kamal-Eldin, A. (2006). Effect of fatty acids and tocopherols on the oxidative stability of vegetable oils. European Journal of Lipid Science and Technology 108, 1051–1061. [CrossRef]

- Karlson, D., Mojica, J. P., Poorten, T. J., Lawit, S. J., Jali, S., Chauhan, R. D., et al. (2022). Targeted Mutagenesis of the Multicopy Myrosinase Gene Family in Allotetraploid Brassica juncea Reduces Pungency in Fresh Leaves across Environments. Plants 11, 2494. [CrossRef]

- Kawall, K. (2019). New possibilities on the horizon: Genome editing makes the whole genome accessible for changes. Frontiers in Plant Science 10. [CrossRef]

- Kawall, K. (2021). Genome-edited Camelina sativa with a unique fatty acid content and its potential impact on ecosystems. Environ Sci Eur 33, 38. [CrossRef]

- Kawall, K., Cotter, J., and Then, C. (2020). Broadening the GMO risk assessment in the EU for genome editing technologies in agriculture. Environ Sci Eur 32, 106. [CrossRef]

- Keadle, S. B., Sykes, V. R., Sams, C. E., Yin, X., Larson, J. A., and Grant, J. F. (2023). National winter oilseeds review for potential in the US Mid-South: Pennycress, Canola, and Camelina. Agronomy Journal 115, 1415–1430. [CrossRef]

- Keeling, C. I., Slessor, K. N., Higo, H. A., and Winston, M. L. (2003). New components of the honey bee (Apis mellifera L.) queen retinue pheromone. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 100, 4486–4491. [CrossRef]

- Knothe, G. (2008). “Designer” Biodiesel: Optimizing Fatty Ester Composition to Improve Fuel Properties. Energy Fuels 22, 1358–1364. https://doi.org/10.1021/ef700639e. [CrossRef]

- Koller, F., and Cieslak, M. (2023). A perspective from the EU: unintended genetic changes in plants caused by NGT—their relevance for a comprehensive molecular characterisation and risk assessment. Frontiers in Bioengineering and Biotechnology 11. Available at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fbioe.2023.1276226 (Accessed November 8, 2023).

- Koller, F., Schulz, M., Juhas, M., Bauer-Panskus, A., and Then, C. (2023). The need for assessment of risks arising from interactions between NGT organisms from an EU perspective. Environmental Sciences Europe 35, 27. [CrossRef]

- Laforest, M., Martin, S., Soufiane, B., Bisaillon, K., Maheux, L., Fortin, S., et al. (2022). Distribution and genetic characterization of bird rape mustard (Brassica rapa) populations and analysis of glyphosate resistance introgression. Pest Management Science 78, 5471–5478. [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.-R., Jeon, I., Yu, H., Kim, S.-G., Kim, H.-S., Ahn, S.-J., et al. (2021). Increasing Monounsaturated Fatty Acid Contents in Hexaploid Camelina sativa Seed Oil by FAD2 Gene Knockout Using CRISPR-Cas9. Front Plant Sci 12, 702930. [CrossRef]

- Li, H., Yu, K., Zhang, Z., Yu, Y., Wan, J., He, H., et al. (2023). Targeted mutagenesis of flavonoid biosynthesis pathway genes reveals functional divergence in seed coat colour, oil content and fatty acid composition in Brassica napus L. Plant Biotechnol J. [CrossRef]

- Li, J., Yu, X., Zhang, C., Li, N., and Zhao, J. (2022). The application of CRISPR/Cas technologies to Brassica crops: current progress and future perspectives. aBIOTECH 3, 146–161. [CrossRef]

- Liu, H., Lin, B., Ren, Y., Hao, P., Huang, L., Xue, B., et al. (2022). CRISPR/Cas9-mediated editing of double loci of BnFAD2 increased the seed oleic acid content of rapeseed (Brassica napus L.). Frontiers in Plant Science 13. Available at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpls.2022.1034215 (Accessed November 23, 2022).

- López, M. V., de la Vega, M., Gracia, R., Claver, A., and Alfonso, M. (2021). Agronomic potential of two European pennycress accessions as a winter crop under European Mediterranean conditions. Industrial Crops and Products 159, 113107. [CrossRef]

- Lutman, P. J. W., Berry, K., Payne, R. W., Simpson, E., Sweet, J. B., Champion, G. T., et al. (2005). Persistence of seeds from crops of conventional and herbicide tolerant oilseed rape (Brassica napus). Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 272, 1909–1915. [CrossRef]

- Lutman, P. J. W., Freeman, S. E., and Pekrun, C. (2003). The long-term persistence of seeds of oilseed rape (Brassica napus) in arable fields. The Journal of Agricultural Science 141, 231–240. [CrossRef]

- Ma, J., Wang, H., and Zhang, Y. (2023). Research progress on the development of pennycress (Thlaspi arvense L.) as a new seed oil crop: a review. Frontiers in Plant Science 14. Available at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpls.2023.1268085 (Accessed January 23, 2024).

- Manning, R. (2001). Fatty acids in pollen: a review of their importance for honey bees. Bee World 82, 60–75. [CrossRef]

- Manning, R., Rutkay, A., Eaton, L., and Dell, B. (2007). Lipid-enhanced pollen and lipid-reduced flour diets and their effect on the longevity of honey bees (Apis mellifera L.). Australian Journal of Entomology 46, 251–257. [CrossRef]

- Marotti, I., Whittaker, A., Benedettelli, S., Dinelli, G., and Bosi, S. (2020). Evaluation of the propensity of interspecific hybridization between oilseed rape (Brassica napus L.) to wild-growing black mustard (Brassica nigra L.) displaying mixoploidy. Plant Sci 296, 110493. [CrossRef]

- McGinn, M., Phippen, W. B., Chopra, R., Bansal, S., Jarvis, B. A., Phippen, M. E., et al. (2019). Molecular tools enabling pennycress (Thlaspi arvense) as a model plant and oilseed cash cover crop. Plant Biotechnol J 17, 776–788. [CrossRef]

- Mitich, L. W. (1996). Field Pennycress (Thlaspi arvense L.)—The Stinkweed. Weed Technology 10, 675–678. [CrossRef]

- Morineau, C., Bellec, Y., Tellier, F., Gissot, L., Kelemen, Z., Nogué, F., et al. (2017). Selective gene dosage by CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing in hexaploid Camelina sativa. Plant Biotechnol J 15, 729–739. [CrossRef]

- Muth, F., Breslow, P. R., Masek, P., and Leonard, A. S. (2018). A pollen fatty acid enhances learning and survival in bumblebees. Behavioral Ecology 29, 1371–1379. [CrossRef]

- Nagaharu, U. (1935). Genome analysis in Brassica with special reference to the experimental formation of B. napus and peculiar mode of fertilization. Jpn J Bot 7, 389–452.

- Napier, J. A. (2021). A Field Day for Gene-Edited Brassicas and Crop Improvement. The CRISPR Journal 4, 307–312. [CrossRef]

- OECD (2012). Consensus document on the biology of the Brassica crops (Brassica spp.). Available at: https://www.oecd.org/science/biotrack/27531440.pdf.

- Okuzaki, A., Ogawa, T., Koizuka, C., Kaneko, K., Inaba, M., Imamura, J., et al. (2018). CRISPR/Cas9-mediated genome editing of the fatty acid desaturase 2 gene in Brassica napus. Plant Physiology and Biochemistry 131, 63–69. [CrossRef]

- Pascher, K., Hainz-Renetzeder, C., Gollmann, G., and Schneeweiss, G. M. (2017). Spillage of Viable Seeds of Oilseed Rape along Transportation Routes: Ecological Risk Assessment and Perspectives on Management Efforts. Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution 5. Available at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fevo.2017.00104 (Accessed February 4, 2024).

- Pascher, K., Macalka, S., Rau, D., Gollmann, G., Reiner, H., Glössl, J., et al. (2010). Molecular differentiation of commercial varieties and feral populations of oilseed rape (Brassica napusL.). BMC Evolutionary Biology 10, 63. [CrossRef]

- Pascher, K., Narendja, F., and Rau, D. (2006). Feral Oilseed Rape: Investigations on Its Potential for Hybridisation; Final Report in Commission of the Federal Ministry of Health and Women (BMGH), Section IV; GZ: 70420/0116-IV/B/12/2004. Bundesministerium für Gesundheit u. Frauen.

- Pasquet, R. S., Peltier, A., Hufford, M. B., Oudin, E., Saulnier, J., Paul, L., et al. (2008). Long-distance pollen flow assessment through evaluation of pollinator foraging range suggests transgene escape distances. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 105, 13456–13461. [CrossRef]

- Piffanelli, P., Ross, J. H. E., and Murphy, D. J. (1997). Intra- and extracellular lipid composition and associated gene expression patterns during pollen development in Brassica napus. Plant J 11, 549–562. [CrossRef]

- Raitskin, O., and Patron, N. J. (2016). Multi-gene engineering in plants with RNA-guided Cas9 nuclease. Current Opinion in Biotechnology 37, 69–75. [CrossRef]

- Ramsay, G., Thompson, C., and Squire, G. (2003). Quantifying Landscape-Scale Gene Flow in Oilseed Rape.

- Reuter, H., Menzel, G., Pehlke, H., and Breckling, B. (2008). Hazard mitigation or mitigation hazard? Environ Sci Pollut Res 15, 529–535. [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Rodríguez, M. F., Moreno-Pérez, A. J., Makni, S., Troncoso-Ponce, M. A., Acket, S., Thomasset, B., et al. (2021). Lipid profiling and oil properties of Camelina sativa seeds engineered to enhance the production of saturated and omega-7 fatty acids. Industrial Crops and Products 170, 113765. [CrossRef]

- Ruedenauer, F. A., Raubenheimer, D., Kessner-Beierlein, D., Grund-Mueller, N., Noack, L., Spaethe, J., et al. (2020). Best be(e) on low fat: linking nutrient perception, regulation and fitness. Ecol Lett 23, 545–554. [CrossRef]

- Saatkamp, A., Affre, L., Dutoit, T., and Poschlod, P. (2009). The seed bank longevity index revisited: limited reliability evident from a burial experiment and database analyses. Annals of Botany 104, 715–724. [CrossRef]

- Schafer, M. G., Ross, A. A., Londo, J. P., Burdick, C. A., Lee, E. H., Travers, S. E., et al. (2011). The establishment of genetically engineered canola populations in the U.S. PLoS One 6, e25736. [CrossRef]

- Schulze, J., Brodmann, P., Oehen, B., and Bagutti, C. (2015). Low level impurities in imported wheat are a likely source of feral transgenic oilseed rape (Brassica napus L.) in Switzerland. Environ Sci Pollut Res 22, 16936–16942. [CrossRef]

- SCRI (2004). SIGMEA Sustainable Introduction of GM Crops into European Agriculture. Available at: https://www6.inrae.fr/sigmea/content/download/3032/31149/version/2/file/SIGMEA+Project+no+501986+-+DELIVERABLE+D2-1.pdf.

- Séguin-Swartz, G., Nettleton, J. A., Sauder, C., Warwick, S., and Gugel, R. (2013). Hybridization between Camelina sativa (L.) Crantz (false flax) and North American Camelina species. Plant Breeding 132. [CrossRef]

- Sharafi, Y., Majidi, M. M., Goli, S. A. H., and Rashidi, F. (2015). Oil Content and Fatty Acids Composition in Brassica Species. International Journal of Food Properties 18, 2145–2154. [CrossRef]

- Shi, J., Ni, X., Huang, J., Fu, Y., Wang, T., Yu, H., et al. (2022). CRISPR/Cas9-Mediated Gene Editing of BnFAD2 and BnFAE1 Modifies Fatty Acid Profiles in Brassica napus. Genes 13, 1681. [CrossRef]

- Shonnard, D. R., Williams, L., and Kalnes, T. N. (2010). Camelina-derived jet fuel and diesel: Sustainable advanced biofuels. Environmental Progress & Sustainable Energy 29, 382–392. [CrossRef]

- Sohn, S.-I., Pandian, S., Oh, Y.-J., Kang, H.-J., Ryu, T.-H., Cho, W.-S., et al. (2021). A Review of the Unintentional Release of Feral Genetically Modified Rapeseed into the Environment. Biology (Basel) 10, 1264. [CrossRef]

- Song, M., Linghu, B., Huang, S., Li, F., An, R., Xie, C., et al. (2022). Genome-Wide Survey of Leucine-Rich Repeat Receptor-Like Protein Kinase Genes and CRISPR/Cas9-Targeted Mutagenesis BnBRI1 in Brassica napus. Frontiers in Plant Science 13. Available at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpls.2022.865132 (Accessed January 24, 2024).

- Squire, G. R., Breckling, B., Dietz Pfeilstetter, A., Jorgensen, R. B., Lecomte, J., Pivard, S., et al. (2011). Status of feral oilseed rape in Europe: its minor role as a GM impurity and its potential as a reservoir of transgene persistence. Environ Sci Pollut Res 18, 111–115. [CrossRef]

- Sun, Q., Lin, L., Liu, D., Wu, D., Fang, Y., Wu, J., et al. (2018). CRISPR/Cas9-Mediated Multiplex Genome Editing of the BnWRKY11 and BnWRKY70 Genes in Brassica napus L. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 19, 2716. [CrossRef]

- Testbiotech (2023). Field trials of plants derived from new genetic engineering - development in Europe. testbiotech. Available at: https://www.testbiotech.org/en/field-trials-new-ge-plants (Accessed January 26, 2024).

- Theenhaus, A., Zeitler, R., Von Brackel, W., Botsch, H.-J., Baumeister, W., and Peichl, L. (2002). Langzeitmonitoring möglicher Auswirkungen gentechnisch veränderter Pflanzen auf Pflanzengesellschaften Konzeptentwicklung am Beispiel von Raps (Brassica napus). UWSF - Z Umweltchem Ökotox 14, 229–236. [CrossRef]

- Tian, Q., Li, B., Feng, Y., Zhao, W., Huang, J., and Chao, H. (2022). Application of CRISPR/Cas9 in Rapeseed for Gene Function Research and Genetic Improvement. Agronomy 12, 824. [CrossRef]

- USDA APHIS (2022). Regulated Article Letters of Inquiry. Available at: https://web.archive.org/web/20220901100946/https://www.aphis.usda.gov/aphis/ourfocus/biotechnology/am-i-regulated/Regulated_Article_Letters_of_Inquiry (Accessed February 2, 2024).

- USDA APHIS (2024). Regulatory Status Review Table. Available at: https://www.aphis.usda.gov/aphis/ourfocus/biotechnology/regulatory-processes/rsr-table/rsr-table (Accessed February 2, 2024).

- Van Reeth, C., Michel, N., Bockstaller, C., and Caro, G. (2019). Influences of oilseed rape area and aggregation on pollinator abundance and reproductive success of a co-flowering wild plant. Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment 280, 35–42. [CrossRef]

- Vanbergen, A. J., and Initiative, the I. P. (2013). Threats to an ecosystem service: pressures on pollinators. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment 11, 251–259. [CrossRef]

- Vaudo, A. D., Stabler, D., Patch, H. M., Tooker, J. F., Grozinger, C. M., and Wright, G. A. (2016). Bumble bees regulate their intake of essential protein and lipid pollen macronutrients. J Exp Biol 219, 3962–3970. [CrossRef]

- Vaudo, A. D., Tooker, J. F., Patch, H. M., Biddinger, D. J., Coccia, M., Crone, M. K., et al. (2020). Pollen Protein: Lipid Macronutrient Ratios May Guide Broad Patterns of Bee Species Floral Preferences. Insects 11, 132. [CrossRef]

- Vollmann, J., and Eynck, C. (2015). Camelina as a sustainable oilseed crop: Contributions of plant breeding and genetic engineering. Biotechnology Journal 10, 525–535. [CrossRef]

- Walsh, K. D., Hills, M. J., Martin, S. L., and Hall, L. M. (2015). Pollen-mediated Gene Flow in Camelina sativa (L.) Crantz. Crop Science 55, 196–202. [CrossRef]

- Walsh, K. D., Raatz, L. L., Topinka, K. C., and Hall, L. M. (2013). Transient Seed Bank of Camelina Contributes to a Low Weedy Propensity in Western Canadian Cropping Systems. Crop Science 53, 2176–2185. [CrossRef]

- Wang, N., Tao, B., Mai, J., Guo, Y., Li, R., Chen, R., et al. (2023). Kinase CIPK9 integrates glucose and abscisic acid signaling to regulate seed oil metabolism in rapeseed. Plant Physiology 191, 1836–1856. [CrossRef]

- Wang, X., Wang, H., Wang, J., Sun, R., Wu, J., Liu, S., et al. (2011). The genome of the mesopolyploid crop species Brassica rapa. Nat Genet 43, 1035–1039. [CrossRef]

- Warwick, S. I., Francis, A., and Susko, D. J. (2002). The biology of Canadian weeds. 9. Thlaspi arvense L. (updated). Can. J. Plant Sci. 82, 803–823. [CrossRef]

- Warwick, S. I., Légère, A., Simard, M.-J., and James, T. (2008). Do escaped transgenes persist in nature? The case of an herbicide resistance transgene in a weedy Brassica rapa population. Molecular Ecology 17, 1387–1395. [CrossRef]

- Wells, R., Trick, M., Soumpourou, E., Clissold, L., Morgan, C., Werner, P., et al. (2014). The control of seed oil polyunsaturate content in the polyploid crop species Brassica napus. Mol Breeding 33, 349–362. [CrossRef]

- Xie, T., Chen, X., Guo, T., Rong, H., Chen, Z., Sun, Q., et al. (2020). Targeted Knockout of BnTT2 Homologues for Yellow-Seeded Brassica napus with Reduced Flavonoids and Improved Fatty Acid Composition. J. Agric. Food Chem. 68, 5676–5690. [CrossRef]

- Zanetti, F., Alberghini, B., Marjanović Jeromela, A., Grahovac, N., Rajković, D., Kiprovski, B., et al. (2021). Camelina, an ancient oilseed crop actively contributing to the rural renaissance in Europe. A review. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 41, 2. [CrossRef]

- Zetsche, B., Heidenreich, M., Mohanraju, P., Fedorova, I., Kneppers, J., DeGennaro, E. M., et al. (2017). Multiplex gene editing by CRISPR-Cpf1 using a single crRNA array. Nat Biotechnol 35, 31–34. [CrossRef]

- Zhai, Y., Yu, K., Cai, S., Hu, L., Amoo, O., Xu, L., et al. (2020). Targeted mutagenesis of BnTT8 homologs controls yellow seed coat development for effective oil production in Brassica napus L. Plant Biotechnology Journal 18, 1153–1168. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.-J., and Auer, C. (2020). Hybridization between Camelina sativa (L.) Crantz and common Brassica weeds. Industrial Crops and Products 147, 112240. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.-J., Wang, Y., Gao, Y., Chen, M., Kim, D.-S., Zhang, Y., et al. (2021). High population density of bee pollinators increasing Camelina sativa (L.) Crantz seed yield: Implications on the potential risk for insect-mediated gene flow. Industrial Crops and Products 172, 114001. [CrossRef]

| Year of Publication | Notification Number | Company/Institute | Title | Plant | Country | Period of Release |

| 2023 | 23/Q02 | Rothamsted Research | Field assessment of gene edited Oilseed Rape with pod shatter resistance | Brassica napus | UK | 2023-2028 |

| 2023 | 23/R08/01 | Rothamsted Research | Synthesis and accumulation of seed storage compounds in Camelina sativa | Camelina sativa | UK | 2023-2026 |

| 2023 | B/SE/23/4198 | Umeå University | Arabidopsis - photosynthesis and hormone biology | Arabidopsis thaliana | Sweden | 2023-2027 |

| 2019 | B/GB/19/R08/01 | Rothamsted Research | Synthesis and accumulation of seed storage compounds in Camelina sativa | Camelina sativa | United Kingdom | 2019-2023 |

| 2019 | B/GB/19/52/01 | John Innes Centre | Genetic regulation of Sulphur metabolism in Brassica oleracea | Brassica oleracea (broccoli) | United Kingdom | 2019-2021 |

| Year of Application | Plant | Applicant | Method | Trait* |

| 2022 | Brassica juncea | Pairwise Plant Services, Inc | CRISPR/Cas9 | Reduced pungency and reduced trichome production |

| 2022 | Pennycress | Hjelle Advisors (CoverCress) | CRISPR/Cas9 | Lowered erucic acid and lowered fiber in seeds |

| 2020 | Canola | Corteva Agriscience | CRISPR/Cas9 | Altered Meal Qualities |

| 2020 | Pennycress | CoverCress | CRISPR/Cas9 (?) | CBI |

| 2020 | Pennycress | Illinois State University | CRISPR/Cas9 (?) | Development of pennycress as an oilseed-producing cover crop |

| 2020 | Canola | Yield10 Bioscience | CRISPR/Cas9 | Altered Oil Content |

| 2020 | Pennycress | CoverCress Inc. | CRISPR/Cas9 | CBI |

| 2020 | Camelina | Yield10 Bioscience | CRISPR/Cas9 | CBI |

| 2020 | Pennycress | CoverCress Inc | CRISPR/Cas9 | CBI |

| 2019 | Pennycress | Illinois State University | CRISPR/Cas9 | CBI |

| 2018 | Camelina | Yield10 Bioscience | CRISPR/Cas9 | CBI |

| 2018 | Pennycress | Illionois State University | CRISPR/Cas9 | Altered Oil Content |

| 2018 | Camelina | Yield 10 | CRISPR/Cas9 | Altered Oil Content |

| 2017 | Camelina | Yield 10 | CRISPR/Cas9 | Altered Oil Content |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).