Submitted:

02 March 2025

Posted:

03 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

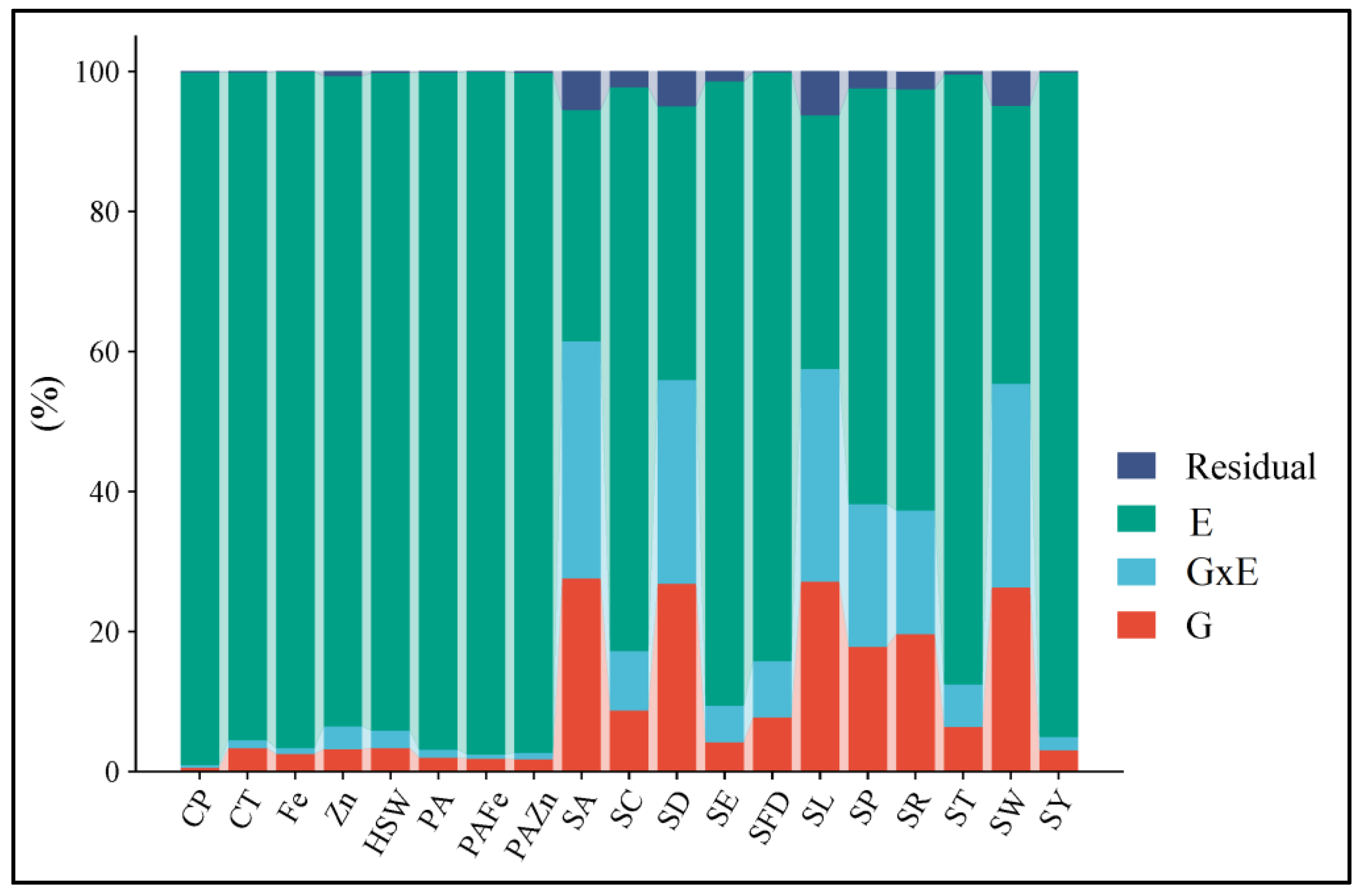

2.1. AMMI Analysis of Variance

2.2. Genotype Main Effects: AMMI Biplots

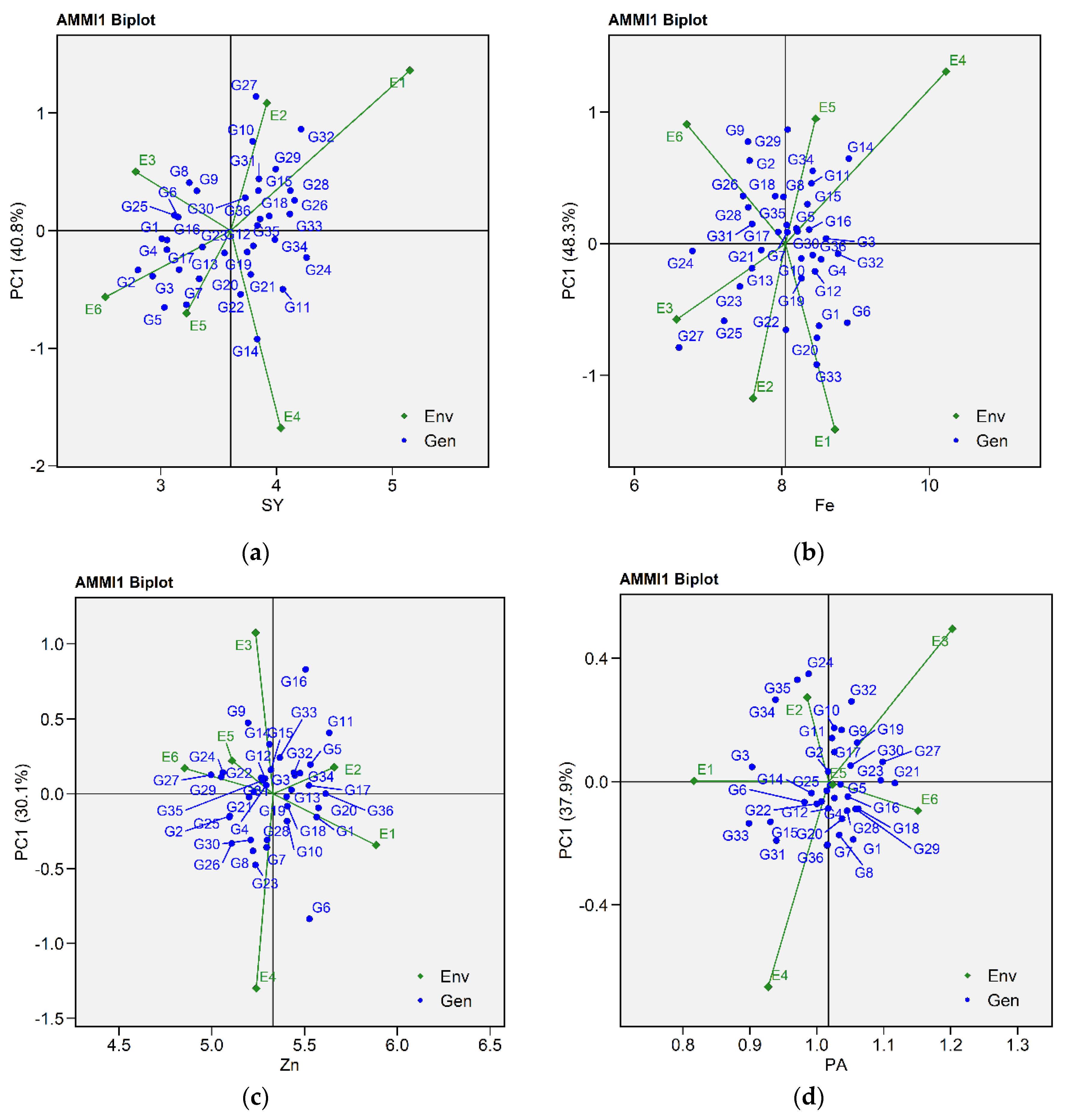

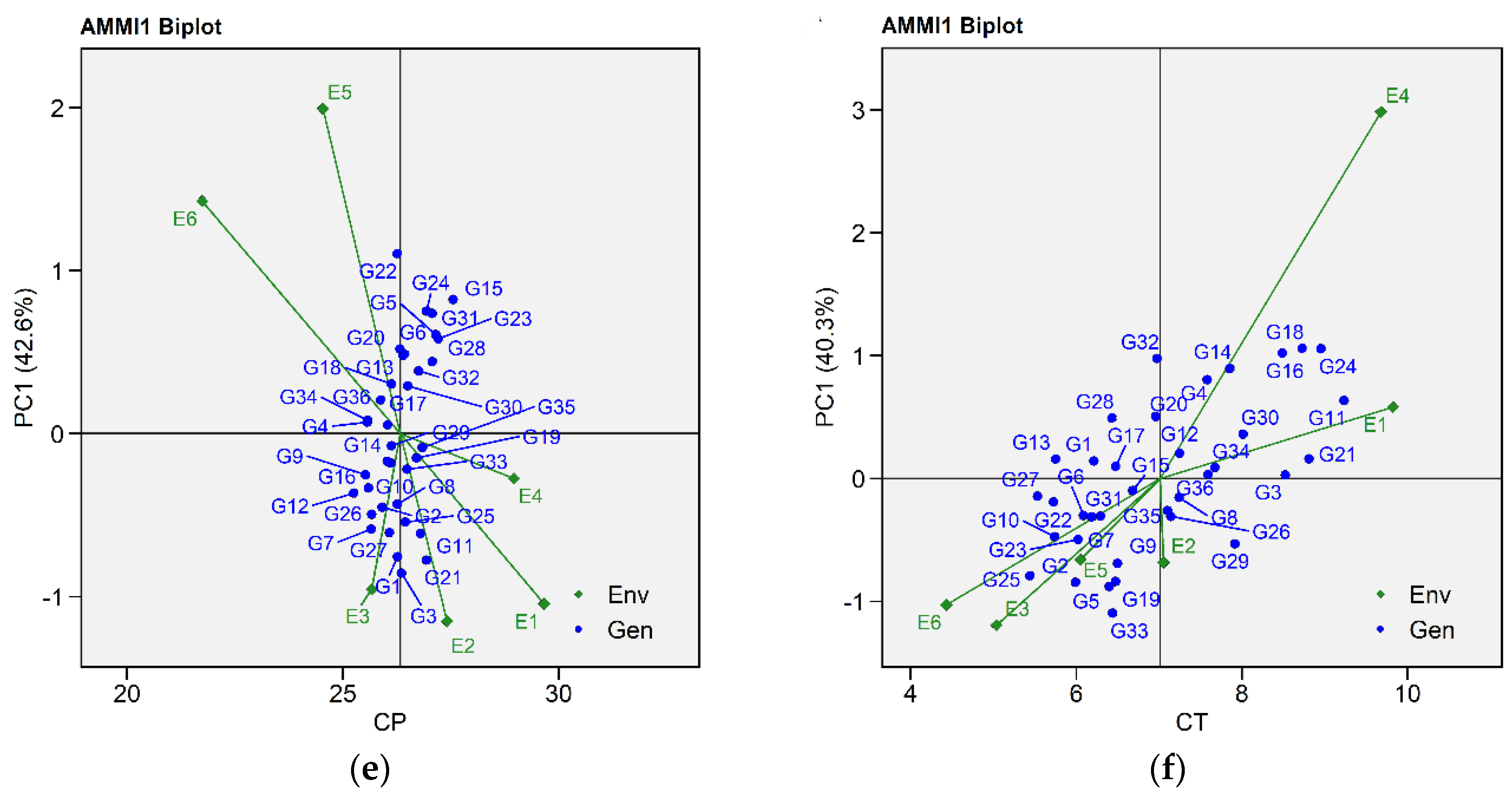

2.2.1. Additive Main Effects and Multiplicative Interaction 1 Biplot

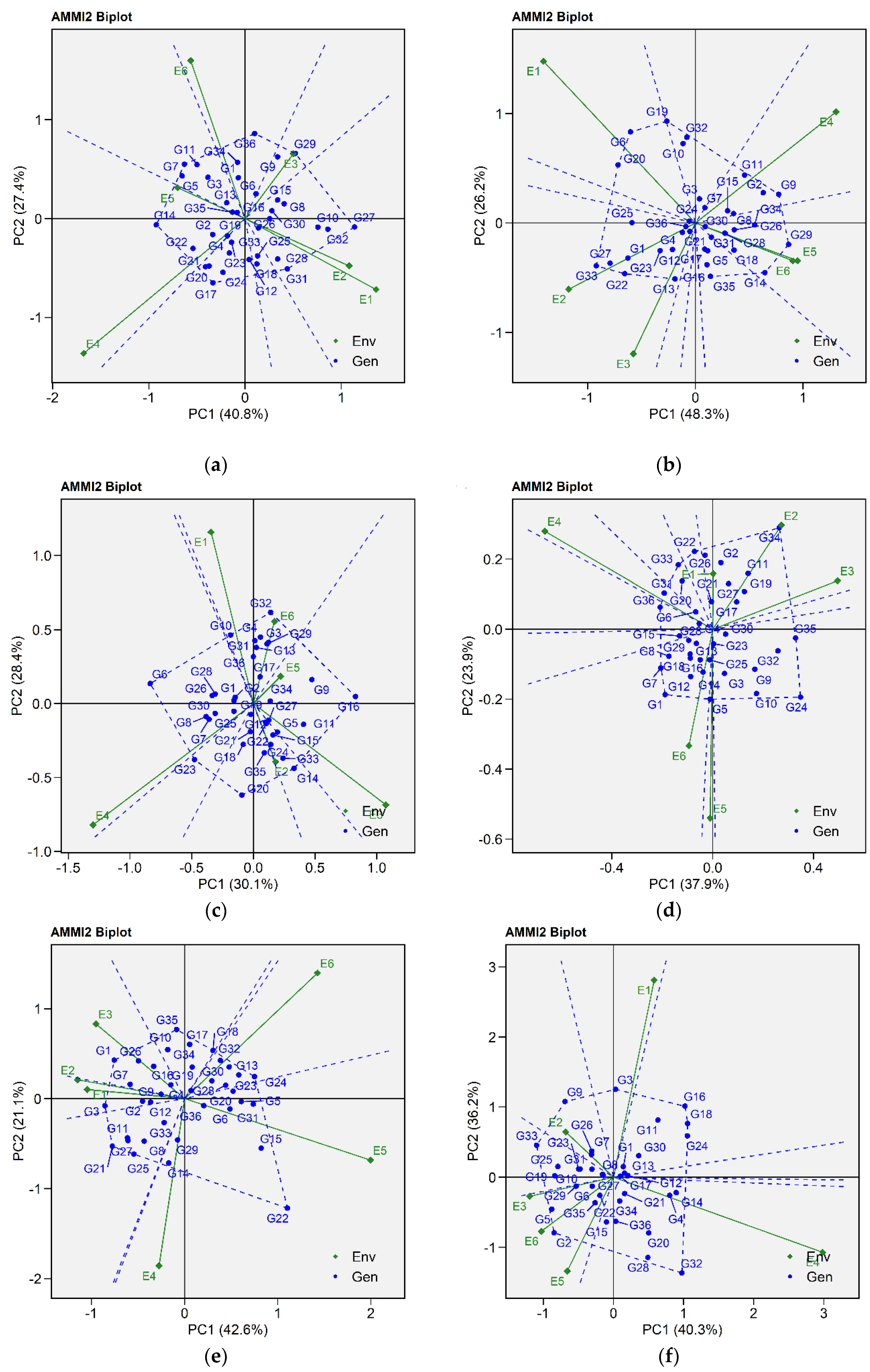

2.2.2. Additive Main Effects and Multiplicative Interaction 2 Biplot

2.2.3. Estimation of AMMI-Based Stability Indexes

2.3. GGE Biplots Based Analysis

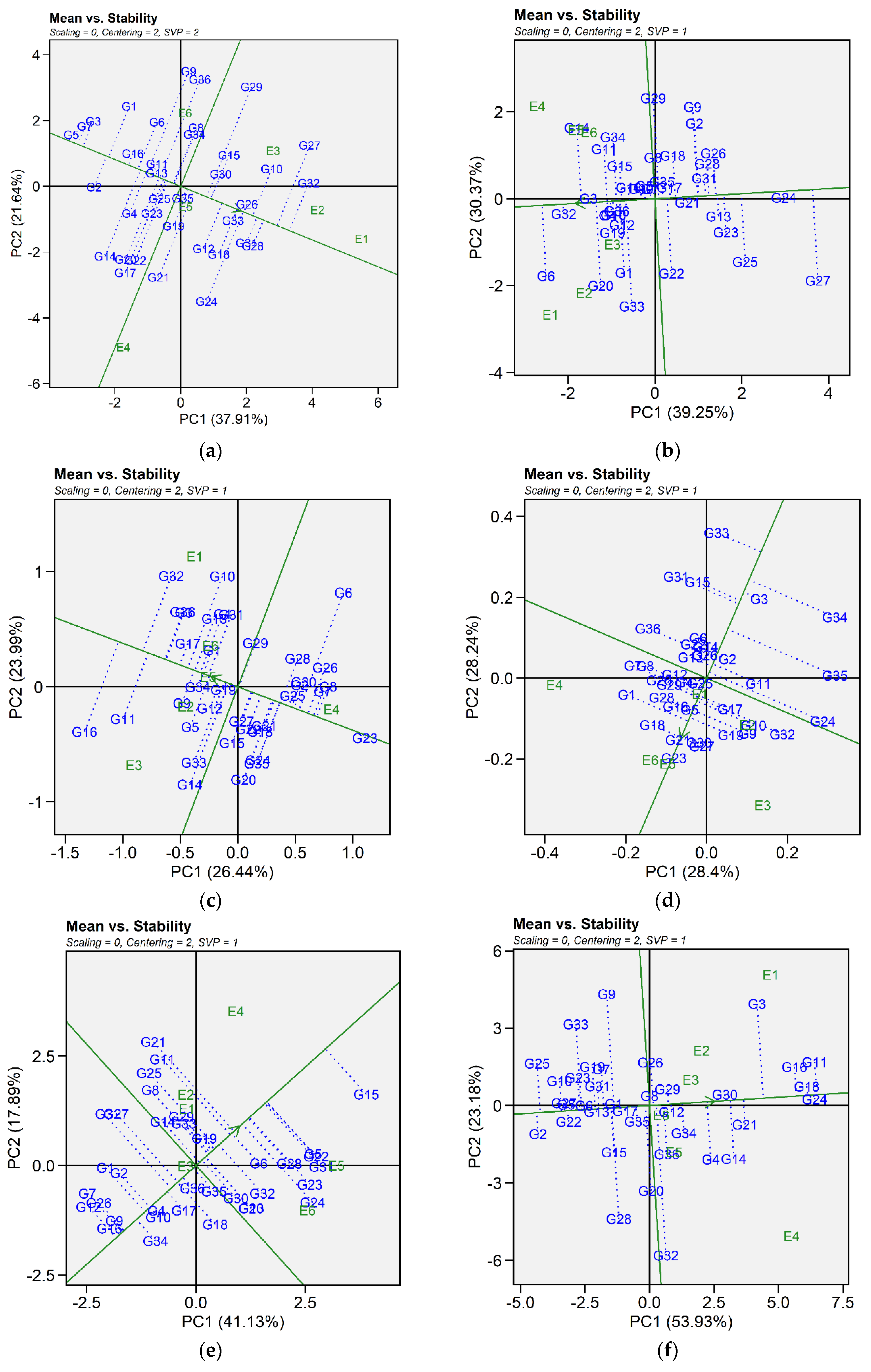

2.3.1. Mean vs. Stability

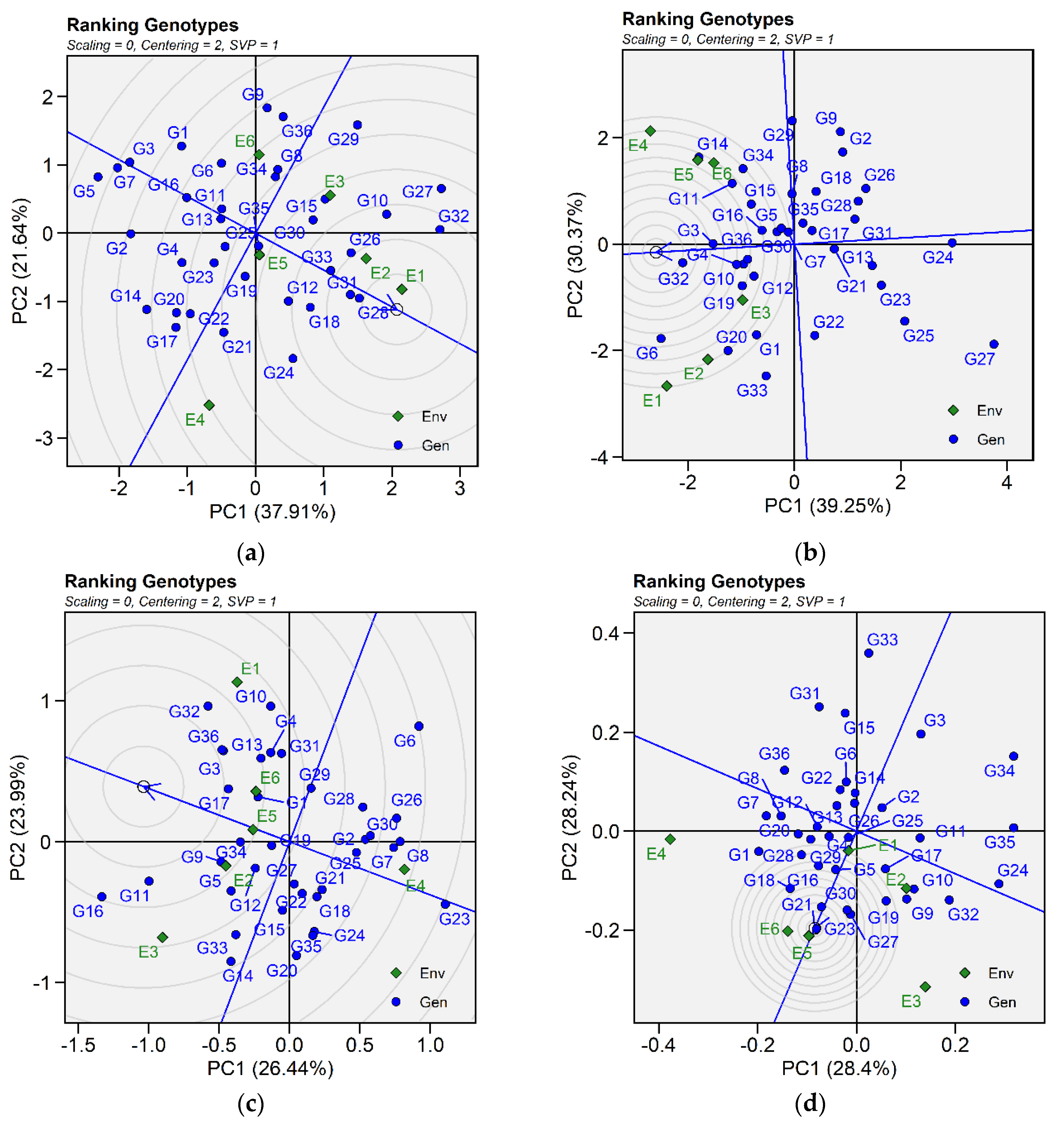

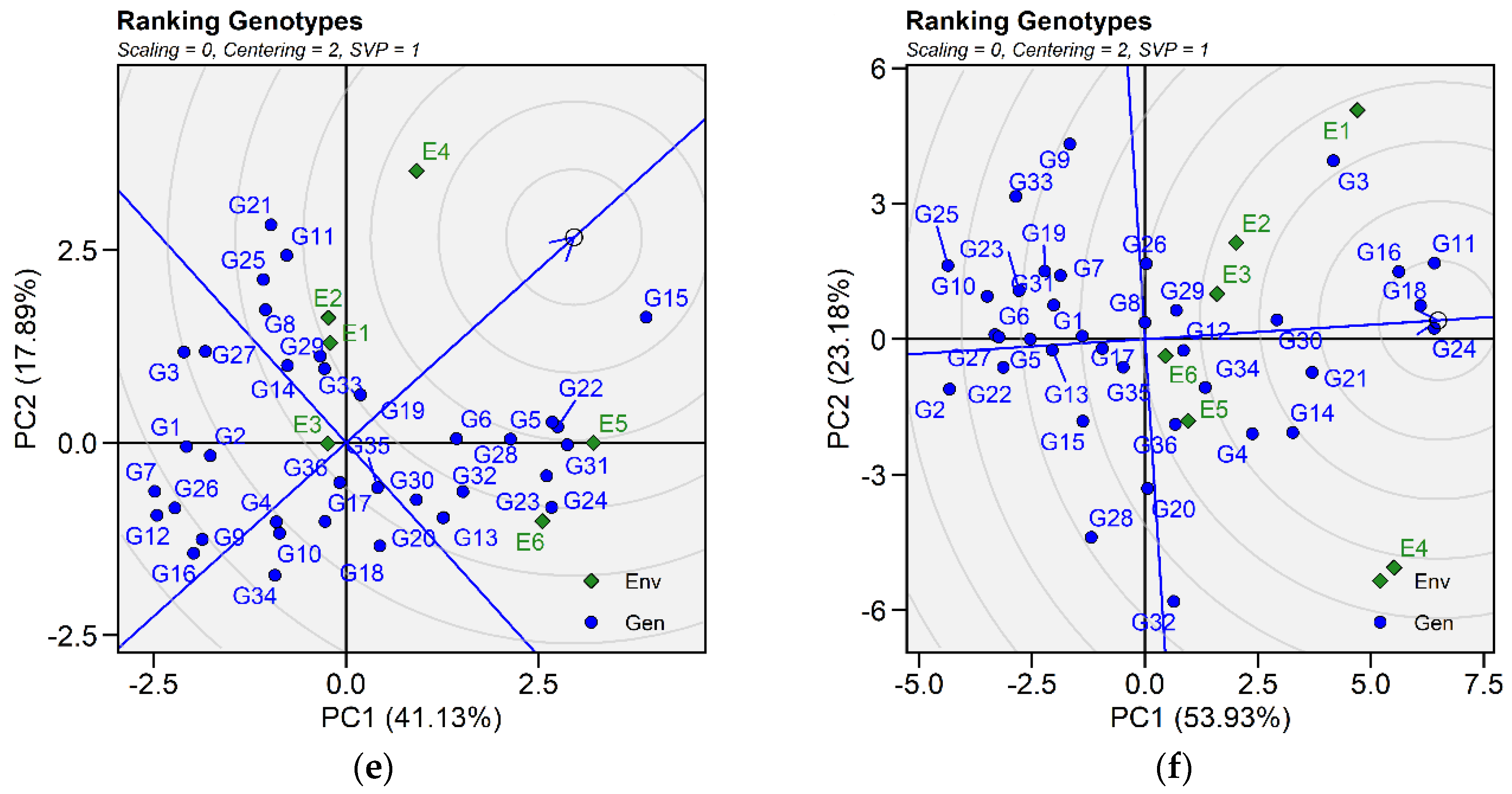

2.3.2. Ranking Genotypes

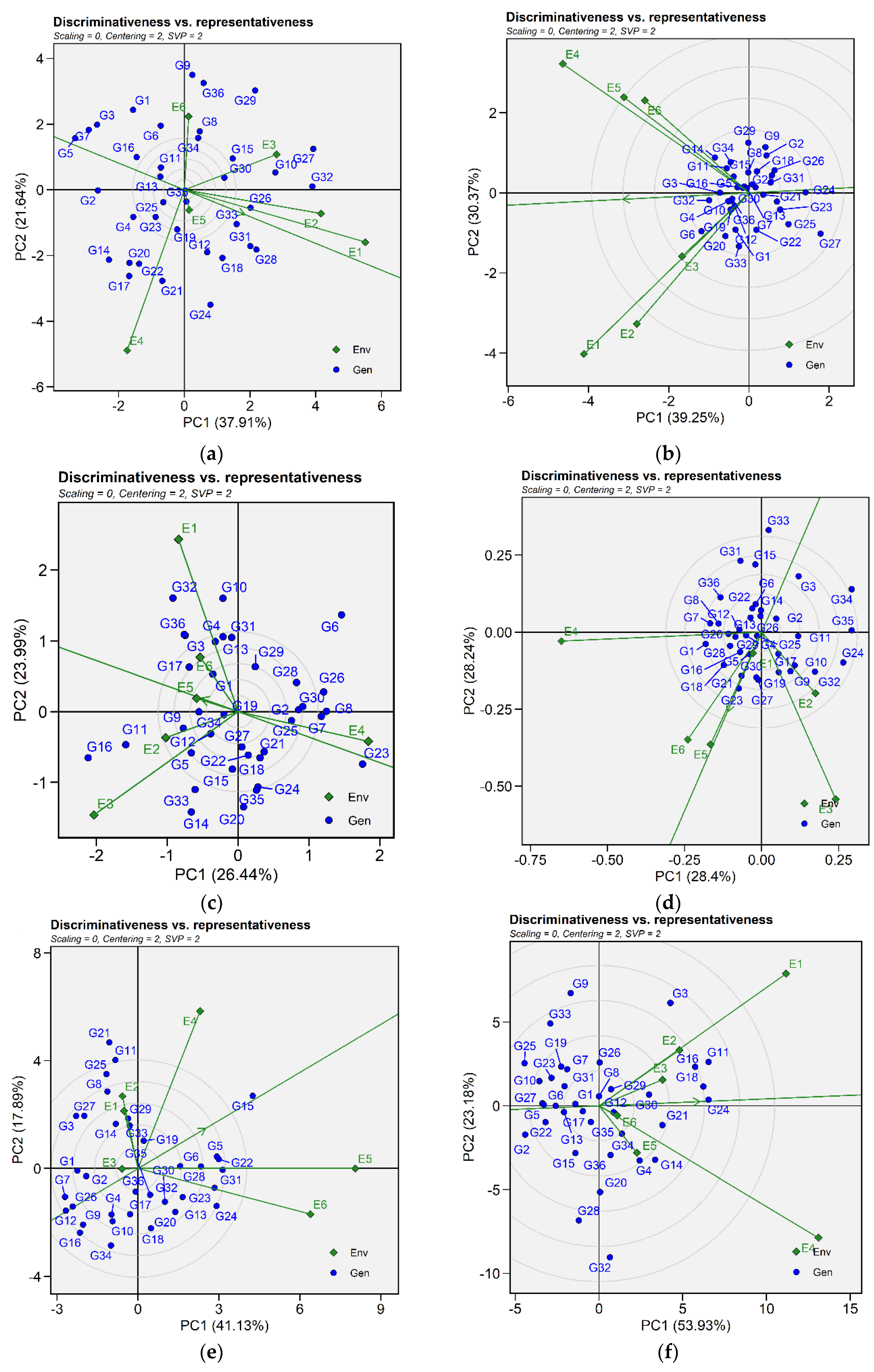

2.3.3. Discriminativeness vs. Representativeness and Ranking Environment

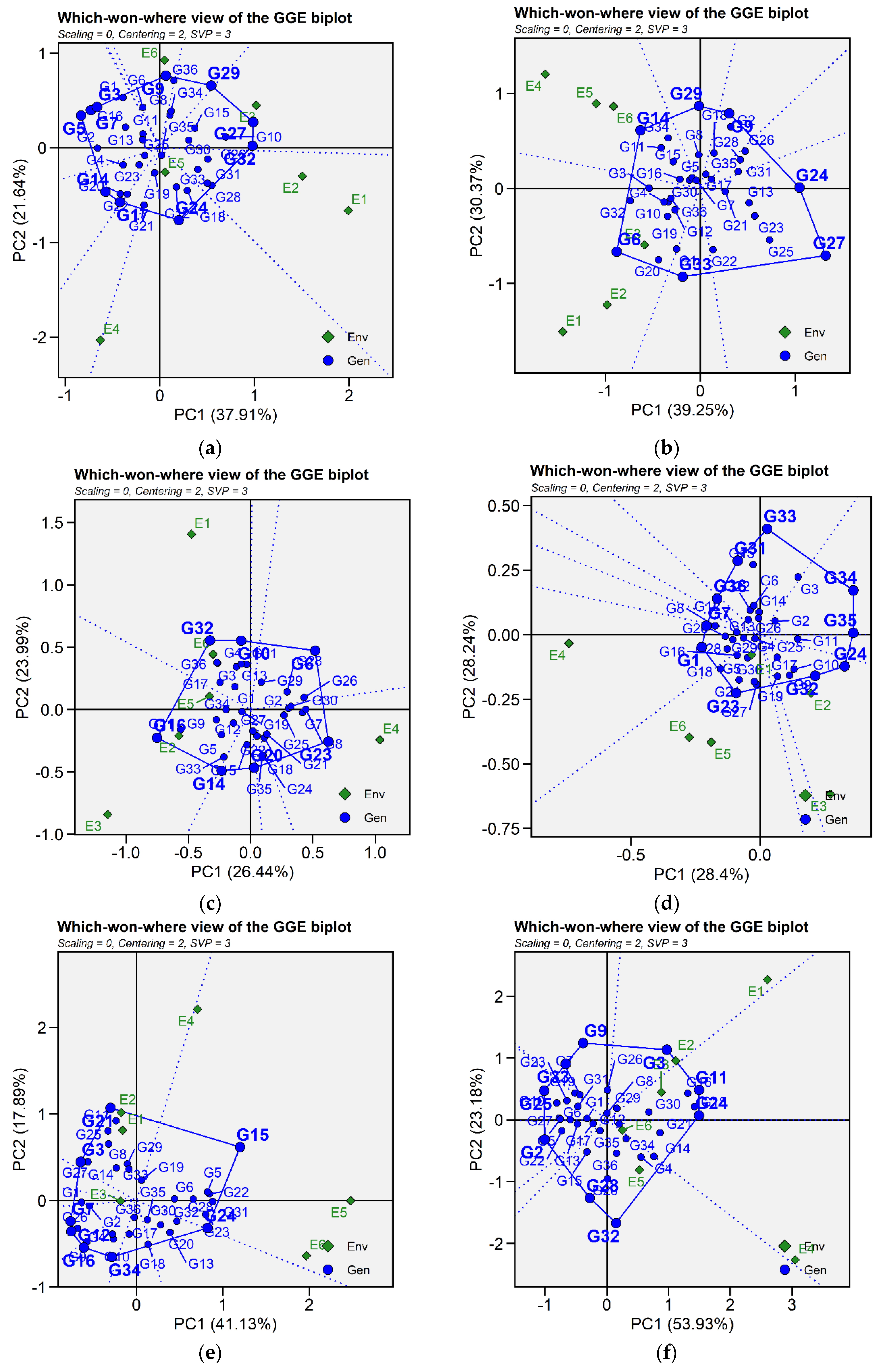

2.3.4. Which-Won-Where and Mega-Environment Identification

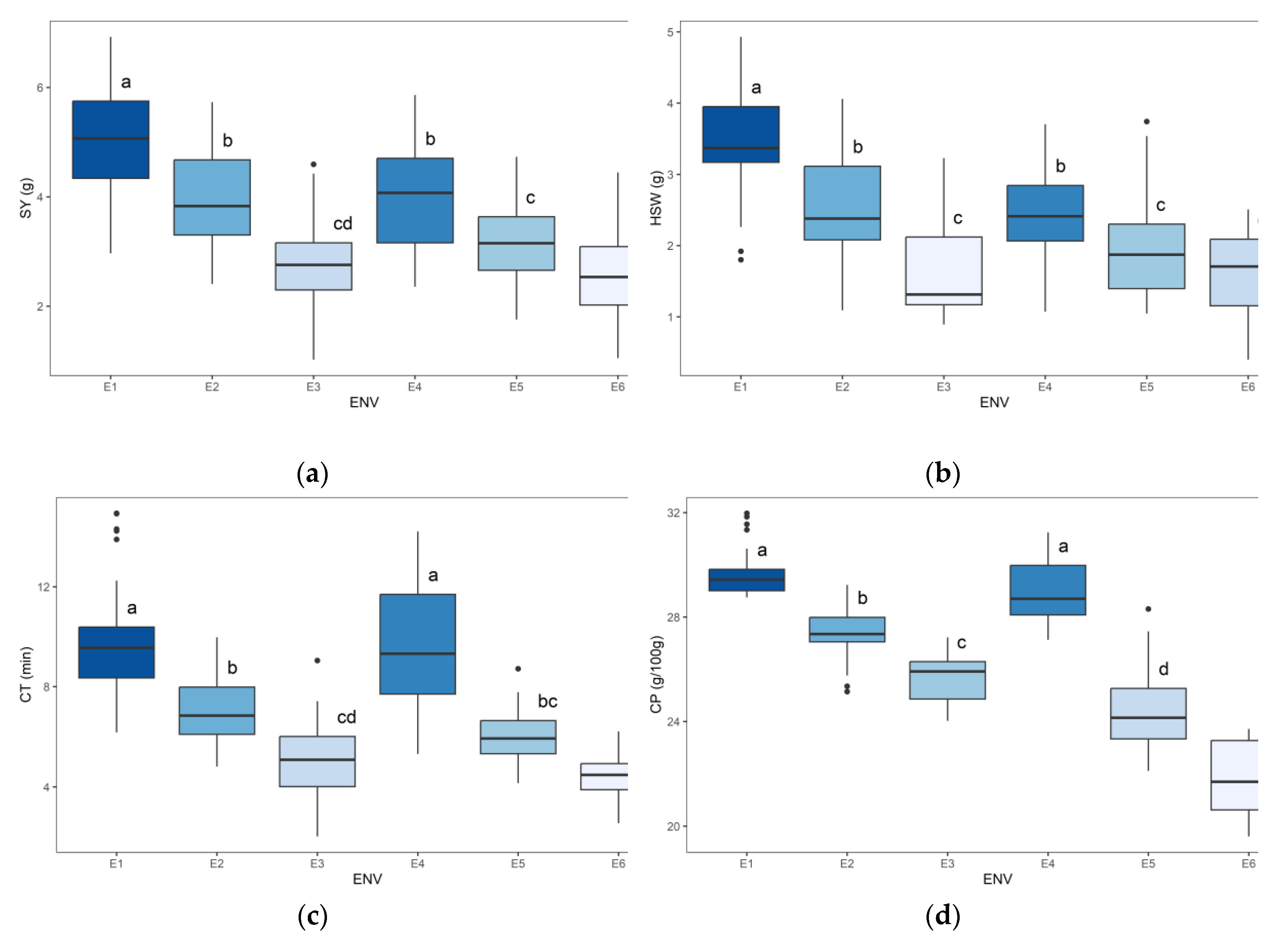

2.4. Mean Performance for Seed Yield, Seed Size and Shape Parameters

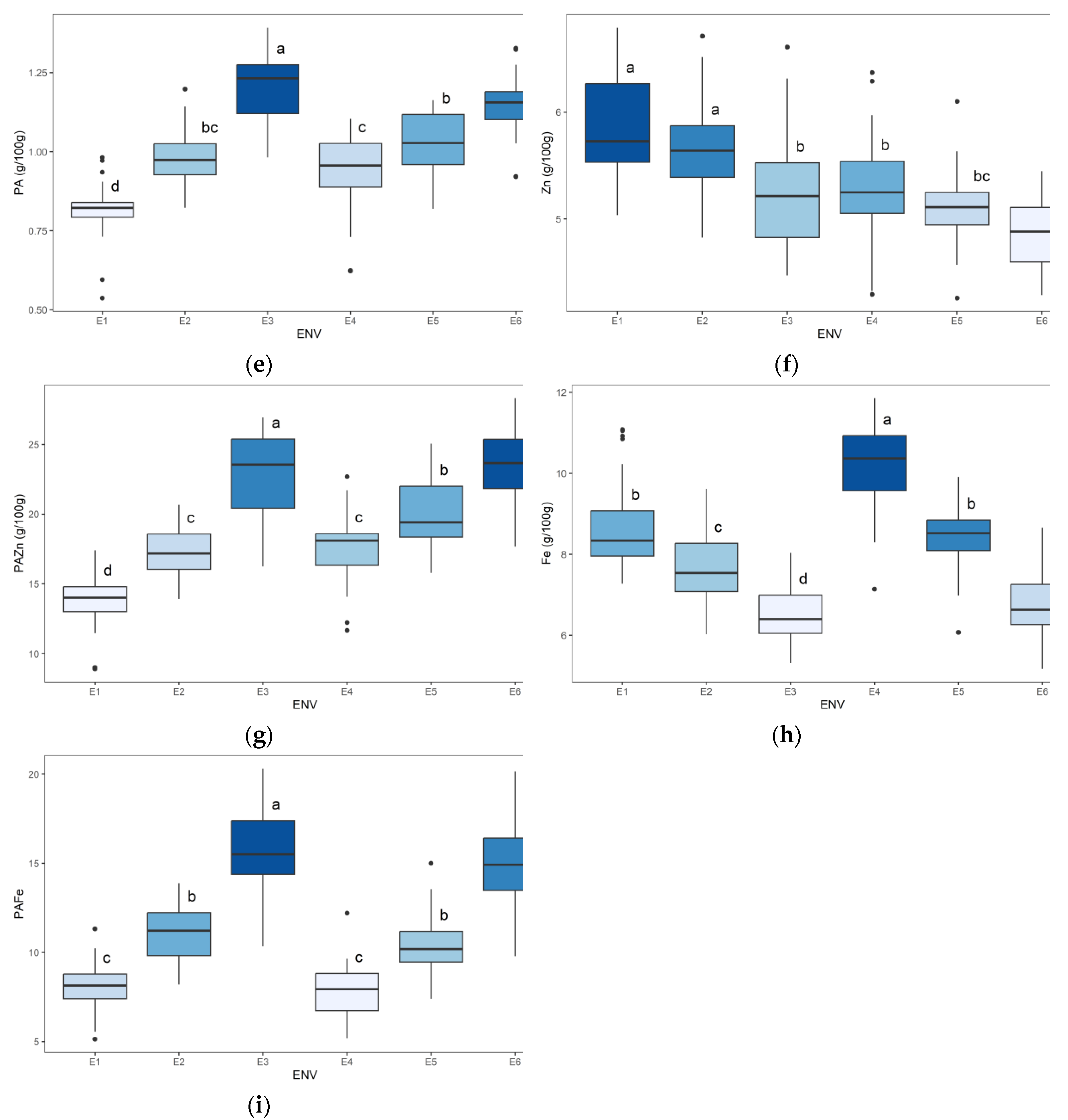

2.5. Mean Performance of Nutritional Quality and Micronutrient Bioavailability

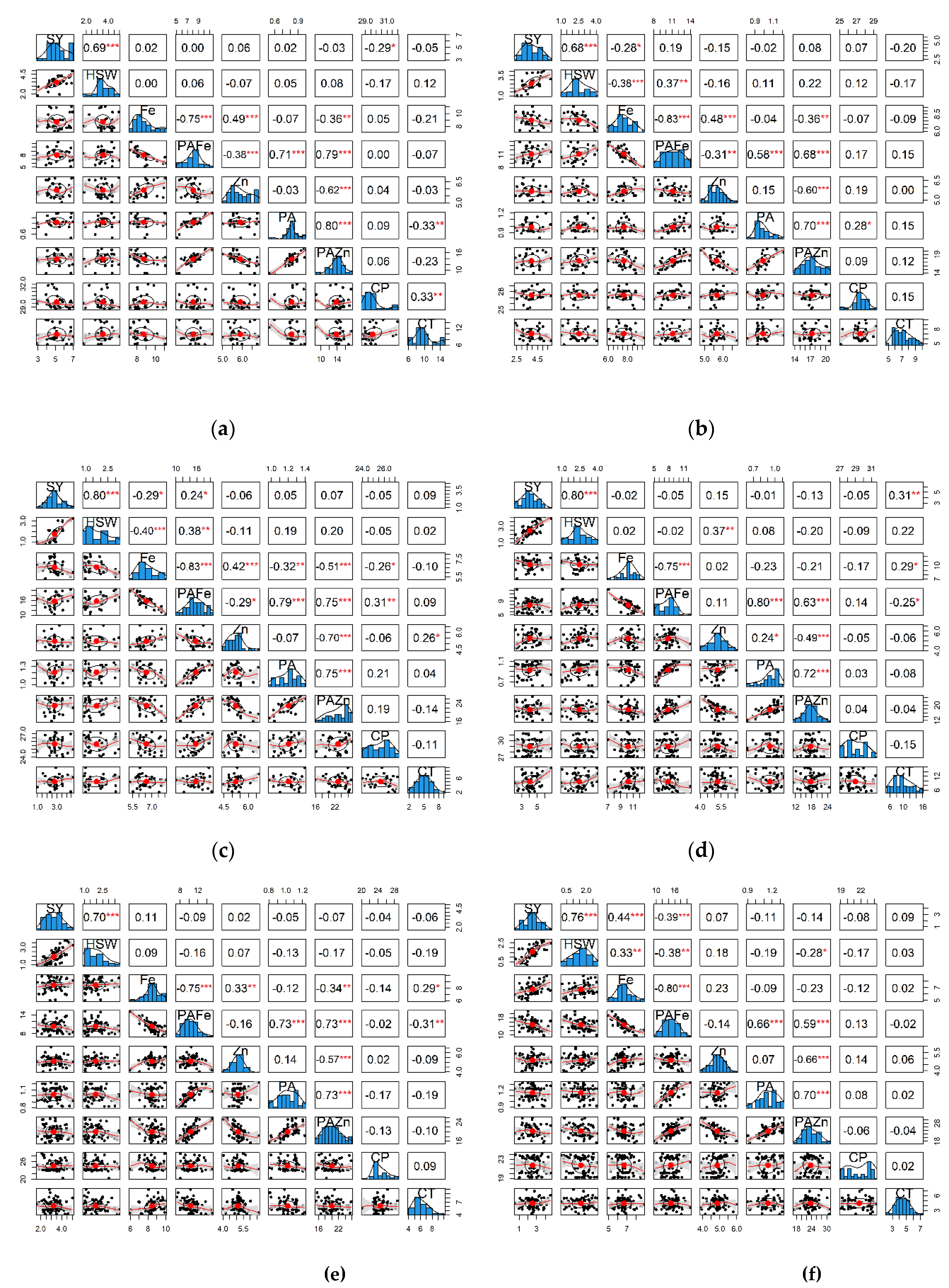

2.6. Correlation Between Seed Yield, Seed Size/Shape, and Nutritional Quality Traits

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Plant Material

4.2. Field Experiment

4.3. Mineral Concentration

4.4. Protein Concentration

4.4. Phytic Acid Concentration

4.5. Seed Siaze and Seed Shape Parameters

4.5. Cooking Time

4.6. Statistical Analyses

4.7. Estimation of AMMI-Based Stability Indexes

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- J. Tang, S. Sokhansanj, and F. W. Sosulski. Moisture-absorption characteristics of laird lentils and hardshell seeds. Cereal Chem. 1994, 71, 423–427. [Google Scholar]

- J. A. Wood. Evaluation of cooking time in pulses: A review. Cereal Chem. 2017, 94, 32–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAOSTAT. Food and Agriculture Organization Corporate Statistical Database.

- M. Habib-ur-Rahman et al. Impact of climate change on agricultural production; Issues, challenges, and opportunities in Asia. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 925548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- H. Choukri et al. Effect of high temperature stress during the reproductive stage on grain yield and nutritional quality of lentil (Lens culinaris Medikus). Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 857469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- N. El Haddad et al. High-temperature and drought stress effects on growth, yield and nutritional quality with transpiration response to vapor pressure deficit in lentil. Plants 2021, 11, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- H. Choukri et al. Heat and drought stress impact on phenology, grain yield, and nutritional quality of lentil (Lens culinaris Medikus). Front. Nutr. 2020, 7, 596307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- K. Sita et al. Impact of heat stress during seed filling on seed quality and seed yield in lentil (Lens culinaris Medikus) genotypes. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2018, 98, 5134–5141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D. Sen Gupta et al. Lentils (Lens culinaris Medik): Nutritional Profile and Biofortification Prospects BT - Compendium of Crop Genome Designing for Nutraceuticals. C. Kole, Ed., Singapore: Springer Nature Singapore, 2023, 1–27. [CrossRef]

- R. Shrestha et al. Genotypic variability and genotype× environment interaction for iron and zinc content in lentil under Nepalese environments. Crop Sci. 2018, 58, 2503–2510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- W. Erskine, P. C. Williams, and H. Nakkoul. Genetic and environmental variation in the seed size, protein, yield, and cooking quality of lentils. F. CroRes. 1985, 12, 153–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- W. Yan, M. S. Kang, B. Ma, S. Woods, and P. L. Cornelius. GGE biplot vs. AMMI analysis of genotype-by-environment data. Crop Sci. 2007, 47, 643–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- H. G. Gauch. Model Selection and Validation for Yield Trials with Interaction. Biometrics 1988, 44, 705–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- H. Kumar et al. Genetic dissection of grain iron and zinc concentrations in lentil (Lens culinaris Medik.). J. Genet. 2019, 98, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- J. Kumar, D. Thavarajah, S. Kumar, A. Sarker, and N. P. Singh. Analysis of genetic variability and genotype× environment interactions for iron and zinc content among diverse genotypes of lentil. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2018, 55, 3592–3605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R. S. Bhatty. Comparisons of good-and poor-cooking lentils. J. Sci. Food Agric. 1995, 68, 489–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- H. Dehghani, S. H. Sabaghpour, and N. Sabaghnia. Genotype× environment interaction for grain yield of some lentil genotypes and relationship among univariate stability statistics. Spanish J. Agric. Res. 2008, 6, 385–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- S. R. E. Abo-Hegazy, T. Selim, and A. A. M. Ashrie. Genotype× environment interaction and stability analysis for yield and its components in lentil. J. Plant Breed. Crop Sci 2013, 5, 85–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- N. K. Yadav, S. K. Ghimire, B. P. Sah, A. Sarker, S. M. Shrestha, and S. K. Sah. Genotype x environment interaction and stability analysis in lentil (Lens culinaris Medik.). Int. J. Environ. Agric. Biotechnol. 2016, 1, 238539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. Ghaffar, M. J. M. Ghaffar, M. J. Asghar, M. Shahid, and J. Hussain. Estimation of G× E Interaction of Lentil Genotypes for Yield using AMMI and GGE Biplot in Pakistan. J. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2023, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- G. Abbas, M. J. Asghar, M. Shahid, J. Hussain, M. Akram, and F. Ahmad. Yield performance of some lentil genotypes over different environments. Agrosystems, Geosci. Environ. 2019, 2, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. Tziouvalekas et al. Seed Yield, Crude Protein and Mineral Nutrients of Lentil Genotypes Evaluated across Diverse Environments under Organic and Conventional Farming. Plants 2022, 11, 3328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. H. Sellami, C. Pulvento, and A. Lavini. Selection of suitable genotypes of lentil (Lens culinaris Medik.) under rainfed conditions in south Italy using multi-trait stability index (MTSI). Agronomy 2021, 11, 1807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- C. Chen et al. Evaluation of environment and cultivar impact on lentil protein, starch, mineral nutrients, and yield. Crop Sci. 2022, 62, 893–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R. Darai, A. Sarker, M. P. Pandey, K. Dhakal, S. Kumar, and R. Sah. Genetic variability and genotype X environment interactions effect on grain iron (Fe) and zinc (Zn) concentration in lentils and their characterization under Terai environments of Nepal. Adv. Nutr. Food Sci. 2020, 5, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- S. Gupta et al. Genotype by environment interaction effect on grain iron and zinc concentration of indian and mediterranean lentil genotypes. Agronomy 2021, 11, 1761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- S. Bhattacharya, A. Das, J. Banerjee, S. N. Mandal, S. Kumar, and S. Gupta. Elucidating genetic variability and genotype× environment interactions for grain iron and zinc content among diverse genotypes of lentils (Lens culinaris). Plant Breed. 2022, 141, 786–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- N. Wang, J. K. Daun, and L. J. Malcolmson. Relationship between physicochemical and cooking properties, and effects of cooking on antinutrients, of yellow field peas (Pisum sativum). J. Sci. Food Agric. 2003, 83, 1228–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- K. E. Ndungu, M. N. Emmambux, and A. Minnaar. Micronisation and hot air roasting of cowpeas as pretreatments to control the development of hard-to-cook phenomenon. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2012, 92, 1194–1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- P. Thavarajah, C.-T. See, and A. Vandenberg. Phytic acid and Fe and Zn concentration in lentil (Lens culinaris L.) seeds is influenced by temperature during seed filling period. Food Chem. 2010, 122, 254–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R. Bansal et al. Seed nutritional quality in lentil (Lens culinaris) under different moisture regimes. Front. Nutr. 2023, 10, 1141040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- N. Anuradha et al. Comparative study of AMMI-and BLUP-based simultaneous selection for grain yield and stability of finger millet [Eleusine coracana (L.) Gaertn.] genotypes. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 12, 786839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. Jamshidmoghaddam and S. S. Pourdad. Genotype× environment interactions for seed yield in rainfed winter safflower (Carthamus tinctorius L.) multi-environment trials in Iran. Euphytica 2013, 190, 357–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- H. G. Gauch Jr. A simple protocol for AMMI analysis of yield trials. Crop Sci. 2013, 53, 1860–1869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- W. Yan and N. A. Tinker. Biplot analysis of multi-environment trial data: Principles and applications. Can. J. plant Sci. 2006, 86, 623–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R. KARIMIZADEH et al. GGE biplot analysis of yield stability in multi-environment trials of lentil genotypes under rainfed condition. Not. Sci. Biol. 2013, 5, 256–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. A. Alam et al. Yield stability of newly released wheat varieties in multi-environments of Bangladesh. Int. J. Plant Soil Sci. 2015, 6, 150–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- W. Yan. GGEbiplot—A Windows application for graphical analysis of multienvironment trial data and other types of two-way data. Agron. J. 2001, 93, 1111–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- W. Yan, D. Pageau, J. Frégeau-Reid, and J. Durand. Assessing the representativeness and repeatability of test locations for genotype evaluation. Crop Sci. 2011, 51, 1603–1610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- W. E. Baethgen and M. M. Alley. A manual colorimetric procedure for measuring ammonium nitrogen in soil and plant Kjeldahl digests. Commun. Soil Sci. Plant Anal. 1989, 10, 961–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Megazyme. Phytic acid assay kit.

- R. W. Zobel. Stress resistance and root systems. in Proceedings of the Workshop on Adaptation of Plants to Soil Stress. Institute of Agriculture and Natural Resources, University of Nebraska-Lincoln, NE, USA, 1994, 80–99.

- P. Annicchiarico. Joint regression vs AMMI analysis of genotype-environment interactions for cereals in Italy. Euphytica, vol. 1997, 94, 53–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- H. F. Smith. A discriminant function for plant selection. Ann. Eugen. 1936, 7, 240–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- J. L. Purchase. Parametric analysis to describe genotype x environment interaction and yield stability in winter wheat. University of the Free State, 1997.

- Z. Ze, L. Cheng, and X. Zhonghuai. Analysis of variety stability based on AMMI model. Zuo wu xue bao 1998, 24, 304–309. [Google Scholar]

- R. Rao and V. T. Prabhakaran. Use ofAMMI in Simultaneous selection of genotypes for yield and stability. J. Indian Soc. Agric. Stat. 2005, 76–82. [Google Scholar]

- H. Zali, E. Farshadfar, S. H. Sabaghpour, and R. Karimizadeh. Evaluation of genotype× environment interaction in chickpea using measures of stability from AMMI model. Ann. Biol. Res. 2012, 3, 3126–3136. [Google Scholar]

- N. N. Jambhulkar et al. Stability analysis for grain yield in rice in demonstrations conducted during rabi season in India. Oryza-An Int. J. Rice 2017, 54, 234–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- C. Ajay et al. Modified AMMI Stability Index (MASI) for stability analysis. ICAR-DGR Newsl 2018, 18, 4–5. [Google Scholar]

- T. Olivoto, A. D. C. Lúcio, J. A. G. da Silva, V. S. Marchioro, V. Q. de Souza, and E. Jost. Mean performance and stability in multi-environment trials I: combining features of AMMI and BLUP techniques. Agron. J. 2019, 111, 2949–2960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A. Chandrashekar et al. Rectification of modified AMMI stability value (MASV). Indian J. Genet. Plant Breed. 2019, 79, 726–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Source of variation | df | SY | HSW | Fe | Zn | PA | PA/Fe | PA/Zn | CP | CT |

| G | 35 | 2.14** | 1.27** | 3.54** | 0.35** | 0.03** | 15.15** | 17.85** | 3.71** | 13.49** |

| E | 5 | 67.31** | 35.62** | 137.08** | 10.22** | 1.46** | 791.19** | 995.32** | 631.79** | 381.57** |

| GEI | 175 | 1.34** | 0.95** | 1.20** | 0.36** | 0.02** | 4.83** | 9.25** | 2.37** | 4.51** |

| IPCA 1 | 39 | 2.45 | 1.74 | 2.60 | 0.48 | 0.03 | 10.36 | 13.70 | 4.54 | 8.16 |

| IPCA 2 | 37 | 1.74 | 1.05 | 1.49 | 0.48 | 0.02 | 6.37 | 13.08 | 2.37 | 7.71 |

| Residuals | 0.10 | 0.09 | 0.09 | 0.08 | 0.00 | 0.43 | 2.05 | 0.63 | 0.58 | |

| R (%) | 96.70 | 95.40 | 98.20 | 88.60 | 96.50 | 98.20 | 94.10 | 96.50 | 96.30 | |

| Source of variation | df | SL | SW | SA | SP | SD | SE | SC | ST | SR |

| G | 35 | 0.46** | 0.47** | 22.96** | 10.23** | 0.48** | 0.00** | 0.00** | 0.00** | 0.00** |

| E | 5 | 0.61** | 0.71** | 27.53** | 34.12** | 0.70** | 0.03** | 0.00** | 0.01** | 0.00** |

| GEI | 175 | 0.51** | 0.52** | 28.24** | 11.74** | 0.52** | 0.00** | 0.00** | 0.00** | 0.00** |

| IPCA 1 | 39 | 0.70 | 0.71 | 37.16 | 23.18 | 0.71 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| IPCA 2 | 37 | 0.58 | 0.60 | 36.52 | 11.82 | 0.59 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Residuals | 0.11 | 0.09 | 4.66 | 1.40 | 0.09 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | |

| R (%) | 82.70 | 85.60 | 85.70 | 89.70 | 85.40 | 83.20 | 82.00 | 94.80 | 88.30 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).